أسرة تشينگ

- لا تخلط بينها وبين أسرة چين.

تشينگ العظمى Great Qing | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1644[1][2]–1912 | |||||||||||||||||

النشيد: گونگ جيناُو (1911) | |||||||||||||||||

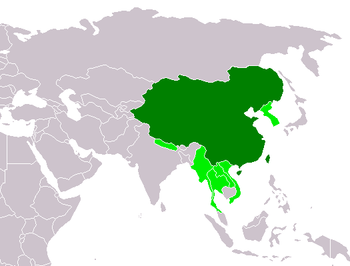

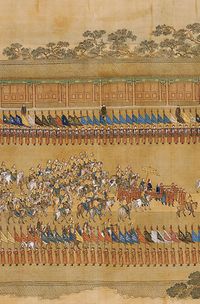

الصين في عصر تشينگ في أقصى اتساع لها. المناطق بالأخضر الفاتح تمثل دولاً تابعة لتشينگ. | |||||||||||||||||

| العاصمة | شـِنگجينگ (1636-1644) بـِيْجينگ (1644-1912) | ||||||||||||||||

| اللغات الشائعة | الصينية، منچو، المنغولية، التبتية، چقطاي، [3] والعديد من اللغات المحلية وتنويعات الصينية | ||||||||||||||||

| الجماعات العرقية | |||||||||||||||||

| الدين | عبادة السماء، الشامانية، الكونفوشية، البوذية، الطاوية، الديانة الشعبية الصينية، الإسلام، المسيحية، أخرى | ||||||||||||||||

| صفة المواطن | صيني | ||||||||||||||||

| الحكومة | ملكية مطلقة | ||||||||||||||||

| امبراطور | |||||||||||||||||

• 1644-1661 | شونجي الامبراطور | ||||||||||||||||

• 1908-1912 | شوانتونگ الامبراطور | ||||||||||||||||

| الوصيات على العرش | |||||||||||||||||

• 1908–1912 | الامبراطورة الأرملة لونگيو | ||||||||||||||||

| رئيس الوزراء | |||||||||||||||||

• 1911 | ييكوانگ، أمير چنگ | ||||||||||||||||

• 1911-1912 | يوان شيكاي | ||||||||||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | أواخر العصر الحديث | ||||||||||||||||

• حكم جين اللاحقة | 1616–1636 | ||||||||||||||||

| 25 أبريل | |||||||||||||||||

| 27 مايو 1644 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1840–1842 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1856–1860 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 أغسطس 1894–17 أبريل 1895 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 أكتوبر 1911 | |||||||||||||||||

| 12 فبراير 1912 | |||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| تقدير 1760 | 13,150,000 km2 (5,080,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| تق. 1790 (بما فيها الدول التابعة)[4] | 14,700,000 km2 (5,700,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| التعداد | |||||||||||||||||

• 1740 | 140.000.000 | ||||||||||||||||

• 1776 | 268.238.000 | ||||||||||||||||

• 1790 | 301.000.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | التائل (Tls.) | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

أظهر

القديم | |||

أظهر

الامبراطوري | |||

أظهر

المعاصر | |||

أظهر

مقالات ذات صلة | |||

أسرة تشينگ (صينية تقليدية: 清朝; پنين: Qīng cháo; ويد-جايلز: Ch'ing ch'ao؛ بالمنچو: ![]() دايتسِنگ گورون؛ بالمنغولية: Манж Чин Улс؛ إنگليزية: Qing Dynasty)، وتـُعرف أيضاً باسم أسرة منشو/منچو Manchu Dynasty، كانت آخر أسرة حاكمة للصين من 1644 إلى 1911. تأسست الأسرة الحاكمة من قبل عائلة آيسن گيورو من شعب الجورچن المانچو في شمال شرق الصين، وهي المنطقة المعروفة تاريخياً بإسم منشوريا. ففي أواخر القرن السادس عشر، بدأ نورحاجي، الذي كان والياً تابعاً لأسرة منگ، في تنظيم عشائر شعب الجورچن في "ألوية"، وهي وحدات عسكرية-اجتماعية ومشكـِّلاً بذلك شعب المانشو. وبحلول 1636، بدأ ابنه هونگ تايجي في إجبار قوات منگ على مغادرة جنوب منشوريا وأعلن أسرة جديدة، چـِنگ، وتعني "صافي" أو "شفاف". وفي 1644، سيطر الفلاحون المتمردون بقيادة لي زيچنگ على عاصمة منگ، بـِيْجنگ. وبدلاً من أن يخضع لهم، آثر جنرال المنگ وو سانگوي أن ينقل ولاءه إلى المانشو وفتح ممر شانهاي لجيوش الألوية بقيادة الأمير دورگون، الذي هزم المتمردين واستولى على بـِيْجنگ. فتح الصين نفسها لم يكتمل حتى 1683 في عهد كانگشي الامبراطور (حكم 1661-1722). الحملات العشر الكبرى للامبراطور چيانلونگ من ع1750 وحتى ع1790 ليمد سيطرة چنگ إلى آسيا الوسطى. وبينما حافظ الحكام المبكرون على ثقافة المانشو، فقد حكموا مستخدمين أساليب ومؤسسات كونفوشية للحكم البيروقراطي. فقد احتفظوا بالامتحانات الإمبراطورية لتعيين صينيي الهان للعمل جنباً بجنب مع المانشو. كما اعتنقوا مُثـُل نظام الجزية في العلاقات الدولية.

دايتسِنگ گورون؛ بالمنغولية: Манж Чин Улс؛ إنگليزية: Qing Dynasty)، وتـُعرف أيضاً باسم أسرة منشو/منچو Manchu Dynasty، كانت آخر أسرة حاكمة للصين من 1644 إلى 1911. تأسست الأسرة الحاكمة من قبل عائلة آيسن گيورو من شعب الجورچن المانچو في شمال شرق الصين، وهي المنطقة المعروفة تاريخياً بإسم منشوريا. ففي أواخر القرن السادس عشر، بدأ نورحاجي، الذي كان والياً تابعاً لأسرة منگ، في تنظيم عشائر شعب الجورچن في "ألوية"، وهي وحدات عسكرية-اجتماعية ومشكـِّلاً بذلك شعب المانشو. وبحلول 1636، بدأ ابنه هونگ تايجي في إجبار قوات منگ على مغادرة جنوب منشوريا وأعلن أسرة جديدة، چـِنگ، وتعني "صافي" أو "شفاف". وفي 1644، سيطر الفلاحون المتمردون بقيادة لي زيچنگ على عاصمة منگ، بـِيْجنگ. وبدلاً من أن يخضع لهم، آثر جنرال المنگ وو سانگوي أن ينقل ولاءه إلى المانشو وفتح ممر شانهاي لجيوش الألوية بقيادة الأمير دورگون، الذي هزم المتمردين واستولى على بـِيْجنگ. فتح الصين نفسها لم يكتمل حتى 1683 في عهد كانگشي الامبراطور (حكم 1661-1722). الحملات العشر الكبرى للامبراطور چيانلونگ من ع1750 وحتى ع1790 ليمد سيطرة چنگ إلى آسيا الوسطى. وبينما حافظ الحكام المبكرون على ثقافة المانشو، فقد حكموا مستخدمين أساليب ومؤسسات كونفوشية للحكم البيروقراطي. فقد احتفظوا بالامتحانات الإمبراطورية لتعيين صينيي الهان للعمل جنباً بجنب مع المانشو. كما اعتنقوا مُثـُل نظام الجزية في العلاقات الدولية.

شهد عهد چيانلونگ الامبراطور (1735-1796) قمة الرخاء والسيطرة الامبراطورية ثم بداية الانحدار. ارتفع اعداد السكان إلى نحو 400 مليون، إلا أن الضرائب والموارد الحكومية ثـُبـِّتت عند مستوى منخفض، مما حتم وقوع أزمة مالية. وحل الفساد، واختبر المتمردون شرعية الحكومة، ولم تغير النخبة الحاكمة عقليتها في مواجهة التغيرات في النظام العالمي. أعقب حرب الأفيون، فرض القوى الاوروپية معاهدات تجارة حرة "غير متكافئة"، الإعفاء من القانون المحلي وموانئ المعاهدات تحت سيطرة الأجانب. أدى تمرد تايپنگ (1849-1860) وانتفاضات المسلمين في آسيا الوسطى إلى مقتل نحو 20 مليون نسمة. وبالرغم من تلك الكوارث، في تجديد تونگژي في ع1860، وتنادت نخبة صينيي الهان للدفاع عن النظام الكونفوشي وعن حكام چنگ. الانجازات الأولية لحركة تقوية الذات سرعان ما دمرتها الحرب الصينية اليابانية الأولى في 1895، التي خسر فيها الچنگ نفوذهم في كوريا وخسروا كذلك امتلاكهم لتايوان. تم تنظيم الجيوش الجديدة، إلا أن إصلاح المائة يوم الطموح في 1898 فضـّته الامبراطورة الأرملة تسيشي، الحاكمة القاسية القديرة. ورداً على ييهىتوان ("الملاكمون") المناهضون بعنف للأجانب، غزت القوى الأجنبية الصين، وحينئذ أعلنت الامبراطورية الأرملة الحرب عليهم، مما أدى إلى هزيمة كارثية.

بعدئذ، بدأت الحكومة اصلاحات مالية وادارية غير مسبوقة، بما فيها الانتخابات، وتشريع قانوني جديد، وإلغاء نظام الامتحانات. وتنافس صن يات-سن وثوريون آخرون مع المصلحين أمثال ليانگ چيچاو والملكيين أمثال كانگ يووِيْ لتحويل إمبراطورية چنگ إلى أمرة عصرية. بعد وفاة الامبراطورة الأرملة والامبراطور في 1908، نفـَّر بلاط المانشو المتصلب كلاً من المصلحين والنخبة المحلية على السواء. وبدأت الانتفاضات في 11 أكتوبر 1911 وهي التي أدت إلى ثورة 1911. وتنازل الامبراطور الأخير عن العرش في 12 فبراير 1912.

الأسماء

عام 1636 أعلن هونگ تايجي أسرة تشينگ العظمى.[5] هناك تفسيرات مختلفة حول معنى الحرف الصيني Qīng (清; 'clear', 'pure') في هذا السياق. تفترض إحدى النظريات وجود تباين مقصود مع أسرة مينگ: الحرف Míng (明; 'bright') يرتبط بالنار في نظام الأبراج الصينية، بينما الحرف Qīng (清) يرتبط بالماء، مما يوضح انتصار أسرة تشينگ في غزو النار بالماء. ومن المحتمل أيضاً أن يكون لهذا الاسم دلالات بوذية تتعلق بالفطنة والتنوير، فضلاً عن ارتباطه بالمانجوسري بوديساتڤا.[6] استخدم الكتاب الأوروپيون الأوائل مصطلح "طارطار" دون تمييز لجميع شعوب شمال أوراسيا، لكن في كتابات التبشير الكاثوليكية في القرن السابع عشر، تأسست كلمة "طارطار" للإشارة فقط إلى المانشو و"طارطاريا" للأراضي التي حكموها - أي منشوريا والأجزاء المجاورة من آسيا الداخلية،[7][8] التي كانت تحكمها أسرة تشينگ قبل انتقال مينگ-تشينگ.

بعد غزو الصين الداخلية، حدد المانشو دولتهم باسم "الصين"، أو ما يكافئها بالصينية Zhōngguó (中國; 'middle kingdom') واسم Dulimbai Gurun بالمنچو.[أ] لقد ساوى الأباطرة بين أراضي دولة تشينگ (بما في ذلك، من بين مناطق أخرى، شمال شرق الصين الحالية، شينجيانگ، منغوليا، والتبت) باعتبارها "الصين" في كل من اللغتين الصينية والمنچو، وعرفوا الصين بأنها دولة متعددة الأعراق، ورفضوا فكرة أن مناطق هان فقط كانت جزءًا من "الصين" بشكل صحيح. استخدمت الحكومة اسمي "الصين" و"تشينگ" بالتبادل للإشارة إلى دولتهم في الوثائق الرسمية،[9] بما في ذلك النسخ باللغة الصينية من المعاهدات وخرائط العالم.[10] أما مصطلح 'الشعب الصيني' (中國人; Zhōngguórén؛ بالمنچو: ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ

ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ ᡳ

ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠ Dulimbai gurun-i niyalma) فيشير إلى جميع رعايا إمبراطورية تشينگ من الهان والمانشو والمنغول.[11] عندما غزة أسرة تشينگ ژونگاريا عام 1759، أعلنت في نصب تذكاري مكتوب بلغة المنچو أن الأرض الجديدة تم استيعابها في "الصين".[12] وروجت حكومة تشينگ لأيديولوجية مفادها أنها تعمل على جمع الشعوب غير الهان "الخارجية" ـ مثل مختلف شعوب المنغول، فضلاً عن التبتيين ـ مع الصينيين الهان "الداخليين" في "عائلة واحدة"، متحدة داخل دولة تشينگ. تستخدم عبارات مثل Zhōngwài yījiā (中外一家) و nèiwài yījiā (內外一家)—كل من "الوطن والخارج كعائلة واحدة" - والتي يمكن ترجمتها على أنها "الوطن والخارج كعائلة واحدة" - لنقل فكرة الوحدة الثقافية التي توسطها تشينگ.[12]

التاريخ

التشكيل

عهد الأسرة "المتألقة" انتهى مع ذلك بفترة من الفوضى والاضطراب والغزو الخارجي: وبينما كانت البلاد منقسمة إلى أحزاب متنافرة متعادية اجتاحتها جحافل جديدة من الغزاة الفاتحين واقتحمت السور العظيم وحاصرت بكين. تلك هي جحافل المنشو.

وكان المنشو شعبا تنگوسياً ظل قروناً كثيرة يعيش في البلاد التي تعرف الآن باسم منشو كو (أي مملكة المنشو)، ومدوا فتوحهم في أول الأمر نحو الشمال حتى وصلوا إلى نهر آمور، ثم اتجهوا نحو الجنوب وهجموا على عاصمة الصينيين. وجمع آخر أباطرة المنج أسرته حوله وشرب نخبهم، وأمر زوجته أن تنتحر، ثم شنق نفسه بمنطقته بعد أن كتب آخر أوامره على طية ثوبه:

"نحن الفقراء في الفضيلة، ذوي الشخصية الحقيرة، قد استحققنا غضب الله العلي القدير. لقد غرر بي وزرائي، وإني لأستحي أن ألقى في الآخرة آبائي وأجدادي، ولهذا فإني أخلع بيدي تاجي عن رأسي، وأنتظر وشعري يغطي وجهي أن يقطع الثوار أشلائي، لا تؤذوا أحداً من أبناء شعبي".

ودفنه المنشو باحتفال يليق بكرامته وأسسوا أسرة تشنج ( الطاهرة) التي حكمت الصين حتى عهدنا الثوري الحاضر.

وسرعان ما أصبحوا هم أيضا صينيين واستمتعت البلاد تحت حكم كانج شي بعهد من الرخاء والسلم والاستنارة لم تعرف له مثيلاً في تاريخها كله. جلس هذا الإمبراطور على العرش وهو في السابعة من عمره، فلما بلغ الثالثة عشرة أمسك بيده زمام الأمور في إمبراطورية لم تكن تشمل وقتئذ بلاد الصين وحدها بل كانت تشمل معها بلاد المغول ومنشوريا وكوريا والهند الصينية وأنام والتبت والتركستان. وما من شك في أنها كانت أكبر إمبراطوريات ذلك العهد وأكثرها ثروة وسكاناً. وحكمها كانگ شي بحكمة وعدل حسدها عليهما معاصراه أورنجزيب ولويس الرابع عشر. وكان الإمبراطور نفسه رجلاً نشيطاً قوي الجسم والعقل، ينشد الصحة في الحياة العنيفة خارج القصور ويعمل في الوقت نفسه على أن يلم بعلوم تلك الأيام وفنونها. وكان يطوف في أنحاء مملكته ويصلح ما فيها من العلوم حيثما وجدها، ومن أعماله أنه عدل قانونها الجنائي. وكان يعيش عيشة بسيطة ليس فيها شيء من الإسراف أو الترف، ويقتصد في نفقات الدولة الإدارية ويفخر بالعمل على رفاهية شعبه. وازدهرت الآداب والعلوم في أيامه بفضل تشجيعه إياها ومناصرتها؛ وعاد فن الخزف إلى أعلى ما وصل إليه في أيام مجده السابقة. وكان متسامحاً في الأمور الدينية فأجاز كل العبادات ودرس اللغة اللاتينية على القساوسة اليسوعيين، وصبر على الأساليب الغربية التي كان يتبعها التجار الأوربيون في ثغور بلاده. ولما مات بعد حكمه الطويل الموفق (1661- 1722) كان آخر ما نطق به هو هذه الألفاظ: "إني لأخشى أن تتعرض الصين في مئات أو آلاف السنين المقبلة إلى خطر الاصطدام مع مختلف الأمم الغربية التي تفد إلى هذه البلاد من وراء البحار".[13]

وبرزت هذه المشاكل الناشئة من ازدياد التبادل التجاري والاتصال بين الصين وأوربا مرة أخرى في عهد إمبراطور آخر قدير من أسرة المنشو هو شين لونگ. وكان هذا الإمبراطور شاعراً أنشأ 34.000 قصيدة إحداها في "الشاي" وصلت إلى مسامع ڤولتير فأرسل "تحياته إلى ملك الصين الفاتن"، وصوره المصورون الفرنسيون وكتبوا تحت صورته باللغة الفرنسية أبياتاً من الشعر لا توفيه حقه من الثناء يقولون فيها:

"إنه يعمل جاهداً دون أن يخلد إلى الراحة للقيام بأعمال حكومته المختلفة التي يعجب الناس بها. وهذا الملك أعظم ملوك العالم وهو أيضاً أعلم الناس في إمبراطوريته بفنون الأدب".

وحكم الصين جيلين كاملين (1737- 1796)، ونزل عن الملك لما بلغ الثامنة والخمسين، ولكنه ظل يشرف على حكومة البلاد حتى توفي (1799). وحدثت في آخر سني حكمه حادثة كان من شأنها أن تذكر المفكرين من الصينيين بما أنذرهم به كانج- شي، فقد أرسلت إنجلترا بعد أن أثارت غضب الإمبراطور باستيراد الأفيون إلى بلاد الصين بعثة برياسة لورد مكارتني لتفاوض شين لونگ في عقد معاهدة تجارية بين البلدين. وأخذ المبعوثون الإنجليز يشرحون للإمبراطور المزايا التي تعود عليه من تبادل التجارة مع إنكلترا وأضافوا إلى أقوالهم أن المعاهدة التي يريدون عقدها سيفترض فيها مساواة ملك بريطانيا بإمبراطور الصين. فما كان من شين لونگ إلا أن أملى هذا الجواب ليرسل إلى جورج الثالث:

"إن الأشياء العجيبة البديعة لا قيمة لها في نظري؛ وليس لمصنوعات بلادكم فائدة لدي. هذا إذن هو ردي على ما تطلبون إليَّ من تعيين ممثل لكم في بلاطي وهو طلب يتعارض مع عادات أسرتي ولا يعود عليكم إلا بالمتاعب. لقد شرحت لك آرائي مفصلة وأمرت مبعوثيك أن يغادروا البلاد في سلام عائدين إلى بلادهم، وخليق بك أيها الملك أن تحترم شعوري هذا، وأن تكون في المستقبل أكثر إخلاصاً وولاء مما كنت في الماضي، حتى يكون خضوعك الدائم لعرشي من أسباب استمتاع بلادك بالسلم والرخاء في مستقبل الأيام".

بهذه العبارات القوية الفخورة حاولت الصين أن تدرأ عنها شر الانقلاب الصناعي. ولكننا سنعرف في الفصول التالية كيف غزت الثورة الصناعية البلاد رغم هذا الاحتياط. ولندرس الآن قبل الكلام عن هذه الثورة العناصر الاقتصادية والسياسية والخلقية التي تتألف منها تلك الحضارة الفذة المستنيرة الجديرة بالدرس، والتي يبدو أن الثورة الصناعية ستقضي عليها القضاء الأخير.

نور حاجي

The early form of the Manchu state was founded by Nurhaci, the chieftain of a minor Jurchen tribe – the Aisin-Gioro – in Jianzhou in the early 17th century. Nurhaci may have spent time in a Han household in his youth, and became fluent in Chinese and Mongolian languages and read the Chinese novels Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin.[14][15] As a vassal of the Ming emperors, he officially considered himself a guardian of the Ming border and a local representative of the Ming dynasty.[16] Nurhaci embarked on an intertribal feud in 1582 that escalated into a campaign to unify the nearby tribes. By 1616, however, he had sufficiently consolidated Jianzhou so as to be able to proclaim himself Khan of the Later Jin dynasty in reference to the previous Jurchen-ruled Jin dynasty.[17]

Two years later, Nurhaci announced the "Seven Grievances" and openly renounced the sovereignty of Ming overlordship in order to complete the unification of those Jurchen tribes still allied with the Ming emperor. After a series of successful battles, he relocated his capital from Hetu Ala to successively bigger captured Ming cities in Liaodong: first Liaoyang in 1621, then Mukden (Shenyang) in 1625.[17] Furthermore, the Khorchin proved a useful ally in the war, lending the Jurchens their expertise as cavalry archers. To guarantee this new alliance, Nurhaci initiated a policy of inter-marriages between the Jurchen and Khorchin nobilities, while those who resisted were met with military action. This is a typical example of Nurhaci's initiatives that eventually became official Qing government policy. During most of the Qing period, the Mongols gave military assistance to the Manchus.[18]

Hong Taiji

Nurhaci died in 1626, and was succeeded by his eighth son, Hong Taiji. Although Hong Taiji was an experienced leader and the commander of two Banners, the Jurchens suffered defeat in 1627, in part due to the Ming's newly acquired Portuguese cannons. To redress the technological and numerical disparity, Hong Taiji in 1634 created his own artillery corps, who cast their own cannons in the European design with the help of defector Chinese metallurgists. One of the defining events of Hong Taiji's reign was the official adoption of the name "Manchu" for the united Jurchen people in November 1635. In 1635, the Manchus' Mongol allies were fully incorporated into a separate Banner hierarchy under direct Manchu command. In April 1636, Mongol nobility of Inner Mongolia, Manchu nobility and the Han mandarin recommended that Hong as the khan of Later Jin should be the emperor of the Great Qing.[19][20] When he was presented with the imperial seal of the Yuan dynasty after the defeat of the last Khagan of the Mongols, Hong Taiji renamed his state from "Great Jin" to "Great Qing" and elevated his position from Khan to Emperor, suggesting imperial ambitions beyond unifying the Manchu territories. Hong Taiji then proceeded to invade Korea again in 1636.

Meanwhile, Hong Taiji set up a rudimentary bureaucratic system based on the Ming model. He established six boards or executive level ministries in 1631 to oversee finance, personnel, rites, military, punishments, and public works. However, these administrative organs had very little role initially, and it was not until the eve of completing the conquest ten years later that they fulfilled their government roles.[21]

Hong Taiji staffed his bureaucracy with many Han Chinese, including newly surrendered Ming officials, but ensured Manchu dominance by an ethnic quota for top appointments. Hong Taiji's reign also saw a fundamental change of policy towards his Han Chinese subjects. Nurhaci had treated Han in Liaodong according to how much grain they had: those with less than 5 to 7 sin were treated badly, while those with more were rewarded with property. Due to a Han revolt in 1623, Nurhaci turned against them and enacted discriminatory policies and killings against them. He ordered that Han who assimilated to the Jurchen (in Jilin) before 1619 be treated equally with Jurchens, not like the conquered Han in Liaodong. Hong Taiji recognized the need to attract Han Chinese, explaining to reluctant Manchus why he needed to treat the Ming defector General Hong Chengchou leniently.[22] Hong Taiji incorporated Han into the Jurchen "nation" as full (if not first-class) citizens, obligated to provide military service. By 1648, less than one-sixth of the bannermen were of Manchu ancestry.[23]

إدعاء التفويض الإلهي

Hong Taiji died suddenly in September 1643. As the Jurchens had traditionally "elected" their leader through a council of nobles, the Qing state did not have a clear succession system. The leading contenders for power were Hong Taiji's oldest son Hooge and Hong Taiji's half brother Dorgon. A compromise installed Hong Taiji's five-year-old son, Fulin, as the Shunzhi Emperor, with Dorgon as regent and de facto leader of the Manchu nation.

Meanwhile, Ming government officials fought against each other, against fiscal collapse, and against a series of peasant rebellions. They were unable to capitalise on the Manchu succession dispute and the presence of a minor as emperor. In April 1644, the capital, Beijing, was sacked by a coalition of rebel forces led by Li Zicheng, a former minor Ming official, who established a short-lived Shun dynasty. The last Ming ruler, the Chongzhen Emperor, committed suicide when the city fell to the rebels, marking the official end of the dynasty.

Li Zicheng then led rebel forces numbering some 200,000[24] to confront Wu Sangui, at Shanhai Pass, a key pass of the Great Wall, which defended the capital. Wu Sangui, caught between a Chinese rebel army twice his size and a foreign enemy he had fought for years, cast his lot with the familiar Manchus. Wu Sangui may have been influenced by Li Zicheng's mistreatment of wealthy and cultured officials, including Li's own family; it was said that Li took Wu's concubine Chen Yuanyuan for himself. Wu and Dorgon allied in the name of avenging the death of the Chongzhen Emperor. Together, the two former enemies met and defeated Li Zicheng's rebel forces in battle on May 27, 1644.[25]

The newly allied armies captured Beijing on 6 June. The Shunzhi Emperor was invested as the "Son of Heaven" on 30 October. The Manchus, who had positioned themselves as political heirs to the Ming emperor by defeating Li Zicheng, completed the symbolic transition by holding a formal funeral for the Chongzhen Emperor. However, conquering the rest of China Proper took another seventeen years of battling Ming loyalists, pretenders and rebels. The last Ming pretender, Prince Gui, sought refuge with the King of Burma, Pindale Min, but was turned over to a Qing expeditionary army commanded by Wu Sangui, who had him brought back to Yunnan province and executed in early 1662.

The Qing had taken shrewd advantage of Ming civilian government discrimination against the military and encouraged the Ming military to defect by spreading the message that the Manchus valued their skills.[26] Banners made up of Han Chinese who defected before 1644 were classed among the Eight Banners, giving them social and legal privileges. Han defectors swelled the ranks of the Eight Banners so greatly that ethnic Manchus became a minority – only 16% in 1648, with Han Bannermen dominating at 75% and Mongol Bannermen making up the rest.[27] Gunpowder weapons like muskets and artillery were wielded by the Chinese Banners.[28] Normally, Han Chinese defector troops were deployed as the vanguard, while Manchu Bannermen were used predominantly for quick strikes with maximum impact, so as to minimize ethnic Manchu losses.[29]

This multi-ethnic force conquered Ming China for the Qing.[30] The three Liaodong Han Bannermen officers who played key roles in the conquest of southern China were Shang Kexi, Geng Zhongming, and Kong Youde, who governed southern China autonomously as viceroys for the Qing after the conquest.[31] Han Chinese Bannermen made up the majority of governors in the early Qing, stabilizing Qing rule.[32] To promote ethnic harmony, a 1648 decree allowed Han Chinese civilian men to marry Manchu women from the Banners with the permission of the Board of Revenue if they were registered daughters of officials or commoners, or with the permission of their banner company captain if they were unregistered commoners. Later in the dynasty the policies allowing intermarriage were done away with.[33]

The first seven years of the young Shunzhi Emperor's reign were dominated by Dorgon's regency. Because of his own political insecurity, Dorgon followed Hong Taiji's example by ruling in the name of the emperor at the expense of rival Manchu princes, many of whom he demoted or imprisoned. Dorgon's precedents and example cast a long shadow. First, the Manchus had entered "South of the Wall" because Dorgon had responded decisively to Wu Sangui's appeal, then, instead of sacking Beijing as the rebels had done, Dorgon insisted, over the protests of other Manchu princes, on making it the dynastic capital and reappointing most Ming officials. No major Chinese dynasty had directly taken over its immediate predecessor's capital, but keeping the Ming capital and bureaucracy intact helped quickly stabilize the regime and sped up the conquest of the rest of the country. Dorgon then drastically reduced the influence of the eunuchs and directed Manchu women not to bind their feet in the Chinese style.[34]

However, not all of Dorgon's policies were equally popular or as easy to implement. The controversial July 1645 edict (the "haircutting order") forced adult Han Chinese men to shave the front of their heads and comb the remaining hair into the queue hairstyle which was worn by Manchu men, on pain of death.[35] The popular description of the order was: "To keep the hair, you lose the head; To keep your head, you cut the hair."[34] To the Manchus, this policy was a test of loyalty and an aid in distinguishing friend from foe. For the Han Chinese, however, it was a humiliating reminder of Qing authority that challenged traditional Confucian values.[36] The order triggered strong resistance in Jiangnan.[37] In the ensuing unrest, some 100,000 Han were slaughtered.[38][[#cite_note-FOOTNOTEEbrey1993[[تصنيف:مقالات_بالمعرفة_بحاجة_لذكر_رقم_الصفحة_بالمصدر_from_October_2010]][[Category:Articles_with_invalid_date_parameter_in_template]]<sup_class="noprint_Inline-Template_"_style="white-space:nowrap;">[<i>[[المعرفة:Citing_sources|<span_title="هذه_المقولة_تحتاج_مرجع_إلى_صفحة_محددة_أو_نطاق_من_الصفحات_تظهر_فيه_المقولة'"`UNIQ--nowiki-0000004C-QINU`"'_(October_2010)">صفحة مطلوبة</span>]]</i>]</sup>-40|[39]]][40]

On 31 December 1650, Dorgon died suddenly, marking the start of the Shunzhi Emperor's personal rule. Because the emperor was only 12 years old at that time, most decisions were made on his behalf by his mother, Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, who turned out to be a skilled political operator. Although his support had been essential to Shunzhi's ascent, Dorgon had centralised so much power in his hands as to become a direct threat to the throne. So much so that upon his death he was bestowed the extraordinary posthumous title of Emperor Yi (義皇帝), the only instance in Qing history in which a Manchu "prince of the blood" (親王) was so honored. Two months into Shunzhi's personal rule, however, Dorgon was not only stripped of his titles, but his corpse was disinterred and mutilated.[41] Dorgon's fall from grace also led to the purge of his family and associates at court. Shunzhi's promising start was cut short by his early death in 1661 at the age of 24 from smallpox. He was succeeded by his third son Xuanye, who reigned as the Kangxi Emperor.

The Manchus sent Han Bannermen to fight against Koxinga's Ming loyalists in Fujian.[42] They removed the population from coastal areas in order to deprive Koxinga's Ming loyalists of resources. This led to a misunderstanding that Manchus were "afraid of water". Han Bannermen carried out the fighting and killing, casting doubt on the claim that fear of the water led to the coastal evacuation and ban on maritime activities.[43] Even though a poem refers to the soldiers carrying out massacres in Fujian as "barbarians", both Han Green Standard Army and Han Bannermen were involved and carried out the worst slaughter.[44] 400,000 Green Standard Army soldiers were used against the Three Feudatories in addition to the 200,000 Bannermen.[45]

كانگشي وتوحيد الصين

The sixty-one year reign of the Kangxi Emperor was the longest of any emperor of China and marked the beginning of the "High Qing" era, the zenith of the dynasty's social, economic and military power. The early Manchu rulers established two foundations of legitimacy that help to explain the stability of their dynasty. The first was the bureaucratic institutions and the neo-Confucian culture that they adopted from earlier dynasties.[46] Manchu rulers and Han Chinese scholar-official elites gradually came to terms with each other. The examination system offered a path for ethnic Han to become officials. Imperial patronage of Kangxi Dictionary demonstrated respect for Confucian learning, while the Sacred Edict of 1670 effectively extolled Confucian family values. His attempts to discourage Chinese women from foot binding, however, were unsuccessful.

The second major source of stability was the Inner Asian aspect of their Manchu identity, which allowed them to appeal to the Mongol, Tibetan and Muslim subjects.[47] The Qing used the title of Emperor (Huangdi or hūwangdi) in Chinese and Manchu (along with titles like the Son of Heaven and Ejen), and among Tibetans the Qing emperor was referred to as the "Emperor of China" (or "Chinese Emperor") and "the Great Emperor" (or "Great Emperor Manjushri"), such as in the 1856 Treaty of Thapathali,[48][49][50] while among Mongols the Qing monarch was referred to as Bogda Khan[51] or "(Manchu) Emperor", and among Muslim subjects in Inner Asia the Qing ruler was referred to as the "Khagan of China" (or "Chinese khagan").[52] The Qianlong Emperor portrayed the image of himself as a Buddhist sage ruler, a patron of Tibetan Buddhism[53] in the hope to appease the Mongols and Tibetans.[54] The Kangxi Emperor also welcomed to his court Jesuit missionaries, who had first come to China under the Ming.

Kangxi's reign started when he was seven years old. To prevent a repeat of Dorgon's monopolizing of power, on his deathbed his father hastily appointed four regents who were not closely related to the imperial family and had no claim to the throne. However, through chance and machination, Oboi, the most junior of the four, gradually achieved such dominance as to be a potential threat. In 1669 Kangxi, through trickery, disarmed and imprisoned Oboi – a significant victory for a fifteen-year-old emperor.

The young emperor faced challenges in maintaining control of his kingdom, as well. Three Ming generals singled out for their contributions to the establishment of the dynasty had been granted governorships in Southern China. They became increasingly autonomous, leading to the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, which lasted for eight years. Kangxi was able to unify his forces for a counterattack led by a new generation of Manchu generals. By 1681, the Qing government had established control over a ravaged southern China, which took several decades to recover.[55]

To extend and consolidate the dynasty's control in Central Asia, the Kangxi Emperor personally led a series of military campaigns against the Dzungars in Outer Mongolia. The Kangxi Emperor expelled Galdan's invading forces from these regions, which were then incorporated into the empire. Galdan was eventually killed in the Dzungar–Qing War.[56] In 1683, Qing forces received the surrender of Formosa (Taiwan) from Zheng Keshuang, grandson of Koxinga, who had conquered Taiwan from the Dutch colonists as a base against the Qing. Winning Taiwan freed Kangxi's forces for a series of battles over Albazin, the far eastern outpost of the Tsardom of Russia. The 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk was China's first formal treaty with a European power and kept the border peaceful for the better part of two centuries. After Galdan's death, his followers, as adherents to Tibetan Buddhism, attempted to control the choice of the next Dalai Lama. Kangxi dispatched two armies to Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, and installed a Dalai Lama sympathetic to the Qing.[57]

الإمبراطوران يـُنگجـِنگ وچيانلونگ

The reigns of the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1723–1735) and his son, the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796), marked the height of Qing power. Yet, as the historian Jonathan Spence puts it, the empire by the end of the Qianlong reign was "like the sun at midday". In the midst of "many glories", he writes, "signs of decay and even collapse were becoming apparent".[58]

After the death of the Kangxi Emperor in the winter of 1722, his fourth son, Prince Yong (雍親王), became the Yongzheng Emperor. He felt a sense of urgency about the problems that had accumulated in his father's later years.[59] In the words of one recent historian, he was "severe, suspicious, and jealous, but extremely capable and resourceful",[60] and in the words of another, he turned out to be an "early modern state-maker of the first order".[61] First, he promoted Confucian orthodoxy and cracked down on unorthodox sects. In 1723 he outlawed Christianity and expelled most Christian missionaries.[62] He expanded his father's system of Palace Memorials, which brought frank and detailed reports on local conditions directly to the throne without being intercepted by the bureaucracy, and he created a small Grand Council of personal advisors, which eventually grew into the emperor's de facto cabinet for the rest of the dynasty. He shrewdly filled key positions with Manchu and Han Chinese officials who depended on his patronage. When he began to realize the extent of the financial crisis, Yongzheng rejected his father's lenient approach to local elites and enforced collection of the land tax. The increased revenues were to be used for "money to nourish honesty" among local officials and for local irrigation, schools, roads, and charity. Although these reforms were effective in the north, in the south and lower Yangzi valley there were long-established networks of officials and landowners. Yongzheng dispatched experienced Manchu commissioners to penetrate the thickets of falsified land registers and coded account books, but they were met with tricks, passivity, and even violence. The fiscal crisis persisted.[63]

Yongzheng also inherited diplomatic and strategic problems. A team made up entirely of Manchus drew up the Treaty of Kyakhta (1727) to solidify the diplomatic understanding with Russia. In exchange for territory and trading rights, the Qing would have a free hand in dealing with the situation in Mongolia. Yongzheng then turned to that situation, where the Zunghars threatened to re-emerge, and to the southwest, where local Miao chieftains resisted Qing expansion. These campaigns drained the treasury but established the emperor's control of the military and military finance.[64]

When Yongzheng Emperor died in 1735 his son Prince Bao (寶親王) became the Qianlong Emperor. Qianlong personally led the Ten Great Campaigns to expand military control into present-day Xinjiang and Mongolia, putting down revolts and uprisings in Sichuan and southern China while expanding control over Tibet. The Qianlong Emperor launched several ambitious cultural projects, including the compilation of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries (or Siku Quanshu), the largest collection of books in Chinese history. Nevertheless, Qianlong used the literary inquisition to silence opposition.[65] Beneath outward prosperity and imperial confidence, the later years of Qianlong's reign were marked by rampant corruption and neglect. Heshen, the emperor's handsome young favorite, took advantage of the emperor's indulgence to become one of the most corrupt officials in the history of the dynasty.[66] Qianlong's son, the Jiaqing Emperor (r. 1796–1820), eventually forced Heshen to commit suicide.

Population was stagnant for the first half of the 17th century due to civil wars and epidemics, but prosperity and internal stability gradually reversed this trend. The Qianlong Emperor bemoaned the situation by remarking, "The population continues to grow, but the land does not." The introduction of new crops from the Americas such as the potato and peanut allowed an improved food supply as well, so that the total population of China during the 18th century ballooned from 100 million to 300 million people. Soon farmers were forced to work ever-smaller holdings more intensely. The only remaining part of the empire that had arable farmland was Manchuria, where the provinces of Jilin and Heilongjiang had been walled off as a Manchu homeland. Despite prohibitions, by the 18th century Han Chinese streamed into Manchuria, both illegally and legally, over the Great Wall and Willow Palisade.

In 1796, open rebellion broke out among followers of the White Lotus Society, who blamed Qing officials, saying "the officials have forced the people to rebel." Officials in other parts of the country were also blamed for corruption, failing to keep the famine relief granaries full, poor maintenance of roads and waterworks, and bureaucratic factionalism. There soon followed uprisings of "new sect" Muslims against local Muslim officials, and Miao tribesmen in southwest China. The White Lotus Rebellion continued for eight years, until 1804, when badly run, corrupt, and brutal campaigns finally ended it.[67]

التمرد والاضطرابات والضغط الخارجي

At the start of the dynasty, the Chinese empire continued to be the hegemonic power in East Asia. Although there was no formal ministry of foreign relations, the Lifan Yuan was responsible for relations with the Mongols and Tibetans in Inner Asia, while the tributary system, a loose set of institutions and customs taken over from the Ming, in theory governed relations with East and Southeast Asian countries. The Treaty of Nerchinsk, signed in 1689, stabilized relations with Tsarist Russia.

However, during the 18th century European empires gradually expanded across the world, as European states developed economies built on maritime trade, colonial extraction, and advances in technology. The dynasty was confronted with newly developing concepts of the international system and state-to-state relations. European trading posts expanded into territorial control in nearby India and on the islands that are now Indonesia. The Qing response, successful for a time, was to establish the Canton System in 1756, which restricted maritime trade to that city (present-day Guangzhou) and gave monopoly trading rights to private Chinese merchants. The British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company had long before been granted similar monopoly rights by their governments.

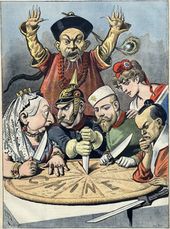

In 1793, the British East India Company, with the support of the British government, sent a diplomatic mission to China led by Lord George Macartney in order to open trade and put relations on a basis of equality. The imperial court viewed trade as of secondary interest, whereas the British saw maritime trade as the key to their economy. The Qianlong Emperor told Macartney "the kings of the myriad nations come by land and sea with all sorts of precious things", and "consequently there is nothing we lack..."[68]

Since China had little demand for European goods, Europe paid in silver for Chinese goods, an imbalance that worried the mercantilist governments of Britain and France. The growing Chinese demand for opium provided the remedy. The British East India Company greatly expanded its production in Bengal. The Daoguang Emperor, concerned both over the outflow of silver and the damage that opium smoking was causing to his subjects, ordered Lin Zexu to end the opium trade. Lin confiscated the stocks of opium without compensation in 1839, leading Britain to send a military expedition the following year. The First Opium War revealed the outdated state of the Chinese military. The Qing navy, composed entirely of wooden sailing junks, was severely outclassed by the modern tactics and firepower of the British Royal Navy. British soldiers, using advanced muskets and artillery, easily outmaneuvered and outgunned Qing forces in ground battles. The Qing surrender in 1842 marked a decisive, humiliating blow. The Treaty of Nanjing, the first of the "unequal treaties", demanded war reparations, forced China to open up the Treaty Ports of Canton, Amoy, Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai to Western trade and missionaries, and to cede Hong Kong Island to Britain. It revealed weaknesses in the Qing government and provoked rebellions against the regime.

The Taiping Rebellion in the mid-19th century was the first major instance of anti-Manchu sentiment. The rebellion began under the leadership of Hong Xiuquan (1814–64), a disappointed civil service examination candidate who, influenced by Christian teachings, had a series of visions and believed himself to be the son of God, the younger brother of Jesus Christ, sent to reform China. A friend of Hong's, Feng Yunshan, utilized Hong's ideas to organize a new religious group, the God Worshippers' Society (Bai Shangdi Hui), which he formed among the impoverished peasants of Guangxi province.[69] Amid widespread social unrest and worsening famine, the rebellion not only posed the most serious threat towards Qing rulers, it has also been called the "bloodiest civil war of all time"; during its fourteen-year course from 1850 to 1864 between 20 and 30 million people died.[70] Hong Xiuquan, a failed civil service candidate, in 1851 launched an uprising in Guizhou province, and established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom with Hong himself as king. Hong announced that he had visions of God and that he was the brother of Jesus Christ. Slavery, concubinage, arranged marriage, opium smoking, footbinding, judicial torture, and the worship of idols were all banned. However, success led to internal feuds, defections and corruption. In addition, British and French troops, equipped with modern weapons, had come to the assistance of the Qing imperial army. Nonetheless, it was not until 1864 that Qing armies under Zeng Guofan succeeded in crushing the revolt. After the outbreak of this rebellion, there were also revolts by the Muslims and Miao people of China against the Qing dynasty, most notably in the Miao Rebellion (1854–1873) in Guizhou, the Panthay Rebellion (1856–1873) in Yunnan and the Dungan Revolt (1862–1877) in the northwest.

The Western powers, largely unsatisfied with the Treaty of Nanjing, gave grudging support to the Qing government during the Taiping and Nian Rebellions. China's income fell sharply during the wars as vast areas of farmland were destroyed, millions of lives were lost, and countless armies were raised and equipped to fight the rebels. In 1854, Britain tried to re-negotiate the Treaty of Nanjing, inserting clauses allowing British commercial access to Chinese rivers and the creation of a permanent British embassy at Beijing.

In 1856, Qing authorities, in searching for a pirate, boarded a ship, the Arrow, which the British claimed had been flying the British flag, an incident which led to the Second Opium War. In 1858, facing no other options, the Xianfeng Emperor agreed to the Treaty of Tientsin, which contained clauses deeply insulting to the Chinese, such as a demand that all official Chinese documents be written in English and a proviso granting British warships unlimited access to all navigable Chinese rivers.

Ratification of the treaty in the following year led to a resumption of hostilities. In 1860, with Anglo-French forces marching on Beijing, the emperor and his court fled the capital for the imperial hunting lodge at Rehe. Once in Beijing, the Anglo-French forces looted and burned the Old Summer Palace and, in an act of revenge for the arrest, torture, and execution of the English diplomatic mission.[71] Prince Gong, a younger half-brother of the emperor, who had been left as his brother's proxy in the capital, was forced to sign the Convention of Beijing. The humiliated emperor died the following year at Rehe.

التقوية الذاتية وفشل الإصلاحات

Following the death of the Xianfeng Emperor in 1861, and the accession of the 5-year-old Tongzhi Emperor, the Qing rallied. In the Tongzhi Restoration, Han Chinese officials such as Zuo Zongtang stood behind the Manchus and organised provincial troops. Zeng Guofan, in alliance with Prince Gong, sponsored the rise of younger officials such as Li Hongzhang, who put the dynasty back on its feet financially and instituted the Self-Strengthening Movement, which adopted Western military technology in order to preserve Confucian values.Their institutional reforms included China's first unified ministry of foreign affairs in the Zongli Yamen, allowing foreign diplomats to reside in the capital, the establishment of the Imperial Maritime Customs Service, the institution of modern navy and army forces including the Beiyang Army, and the purchase of armament factories from the Europeans.[72]

The dynasty gradually lost control of its peripheral territories. In return for promises of support against the British and the French, the Russian Empire took large chunks of territory in the Northeast in 1860. The period of cooperation between the reformers and the European powers ended with the 1870 Tianjin Massacre, which was incited by the murder of French nuns set off by the belligerence of local French diplomats. Starting with the Cochinchina Campaign in 1858, France expanded control of Indochina. By 1883, France was in full control of the region and had reached the Chinese border. The Sino-French War began with a surprise attack by the French on the Chinese southern fleet at Fuzhou. After that the Chinese declared war on the French. A French invasion of Taiwan was halted and the French were defeated on land in Tonkin at the Battle of Bang Bo. However Japan threatened to enter the war against China due to the Gapsin Coup and China chose to end the war with negotiations. The war ended in 1885 with the Treaty of Tientsin and the Chinese recognition of the French protectorate in Vietnam.[73] Some Russian and Chinese gold miners also established a short-lived proto-state known as the Zheltuga Republic (1883–1886) in the Amur River basin, which was however soon crushed by the Qing forces.[74]

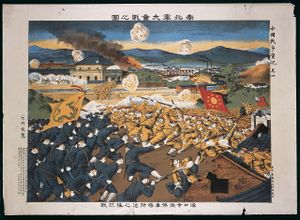

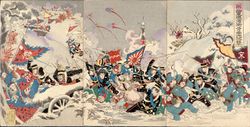

In 1884, Qing China obtained concessions in Korea, such as the Chinese concession of Incheon,[75] but the pro-Japanese Koreans in Seoul led the Gapsin Coup. Tensions between China and Japan rose after China intervened to suppress the uprising. The Japanese prime minister Itō Hirobumi and Li Hongzhang signed the Convention of Tientsin, an agreement to withdraw troops simultaneously, but the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895 was a military humiliation. The Treaty of Shimonoseki recognised Korean independence and ceded Taiwan and the Pescadores to Japan. The terms might have been harsher, but when a Japanese citizen attacked and wounded Li Hongzhang, an international outcry shamed the Japanese into revising them. The original agreement stipulated the cession of Liaodong Peninsula to Japan, but Russia, with its own designs on the territory, along with Germany and France, in the Triple Intervention, successfully put pressure on the Japanese to abandon the peninsula.

These years saw the participation of Empress Dowager Cixi in state affairs. Cixi initially entered the imperial palace in the 1850s as a concubine of the Xianfeng Emperor, and became the mother of the future Tongzhi Emperor. Following the his accession at the age of five, Cixi, Xianfeng's widow Empress Dowager Ci'an, and Prince Gong (a son of the Daoguang Emperor), staged a coup that ousted several of the Tongzhi Emperor's regents. Between 1861 and 1873, Cixi and Ci'an served as regents together; following the emperor's death in 1875, Cixi's nephew, the Guangxu Emperor, took the throne in violation of the custom that the new emperor be of the next generation, and another regency began. Ci'an suddenly died in the spring of 1881, leaving Cixi as sole regent.[76]

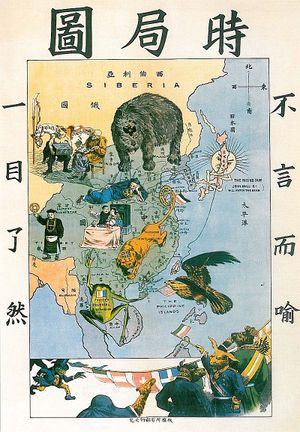

From 1889, when Guangxu began to rule in his own right, until 1898, the Empress Dowager lived in semi-retirement, spending the majority of the year at the Summer Palace. In 1897, two German Roman Catholic missionaries were murdered in southern Shandong province (the Juye Incident). Germany used the murders as a pretext for a naval occupation of Jiaozhou Bay. The occupation prompted a Scramble for China in 1898, which included the German lease of Jiaozhou Bay, the Russian lease of Liaodong, the British lease of the New Territories of Hong Kong, and the French lease of Guangzhouwan.

In the wake of these external defeats, the Guangxu Emperor initiated the Hundred Days' Reform in 1898. Newer, more radical advisers such as Kang Youwei were given positions of influence. The emperor issued a series of edicts and plans were made to reorganise the bureaucracy, restructure the school system, and appoint new officials. Opposition from the bureaucracy was immediate and intense. Although she had been involved in the initial reforms, the Empress Dowager stepped in to call them off, arrested and executed several reformers, and took over day-to-day control of policy. Yet many of the plans stayed in place, and the goals of reform were implanted.[77]

Drought in North China, combined with the imperialist designs of European powers and the instability of the Qing government, created background conditions for the Boxers. In 1900, local groups of Boxers proclaiming support for the Qing dynasty murdered foreign missionaries and large numbers of Chinese Christians, then converged on Beijing to besiege the Foreign Legation Quarter. A coalition of European, Japanese, and Russian armies (the Eight-Nation Alliance) then entered China without diplomatic notice, much less permission. Cixi declared war on all of these nations, only to lose control of Beijing after a short, but hard-fought campaign. She fled to Xi'an. The victorious allies then enforced their demands on the Qing government, including compensation for their expenses in invading China and execution of complicit officials, via the Boxer Protocol.[78]

الإصلاح والثورة والانهيار

The defeat by Japan in 1895 created a sense of crisis which the failure of the 1898 reforms and the disasters of 1900 only exacerbated. Cixi in 1901 moved to mollify the foreign community, called for reform proposals, and initiated the Late Qing reforms. Over the next few years the reforms included the restructuring of the national education, judicial, and fiscal systems, the most dramatic of which was the abolition of the imperial examination system in 1905.[79] The court directed a constitution to be drafted, and provincial elections were held, the first in China's history.[80] Sun Yat-sen and revolutionaries debated reform officials and constitutional monarchists such as Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao over how to transform the Manchu-ruled empire into a modernised Han Chinese state.[81]

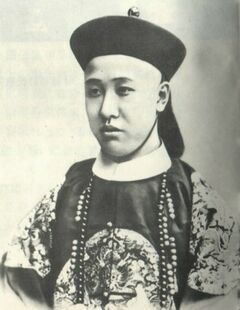

The Guangxu Emperor died on 14 November 1908, and Cixi died the following day. Puyi, the oldest son of Zaifeng, Prince Chun, and nephew to the childless Guangxu Emperor, was appointed successor at the age of two, leaving Zaifeng with the regency. Zaifeng forced Yuan Shikai to resign. The Qing dynasty became a constitutional monarchy on 8 May 1911, when Zaifeng created a "responsible cabinet" led by Yikuang, Prince Qing. However, it became known as the "royal cabinet", as five of its thirteen members, were part of or related to the royal family.[82]

The Wuchang Uprising on 10 October 1911 set off a series of uprisings. By November, 14 of the 22 provinces had rejected Qing rule. This led to the creation of the Republic of China, in Nanjing on 1 January 1912, with Sun Yat-sen as its provisional head. Seeing a desperate situation, the Qing court brought Yuan Shikai back to power. His Beiyang Army crushed the revolutionaries in Wuhan at the Battle of Yangxia. After taking the position of Prime Minister he created his own cabinet, with the support of Empress Dowager Longyu. However, Yuan Shikai decided to cooperate with Sun Yat-sen's revolutionaries to overthrow the Qing dynasty.

On 12 February 1912, Longyu issued the abdication of the child emperor Puyi leading to the fall of the Qing dynasty under the pressure of Yuan Shikai's Beiyang army despite objections from conservatives and royalist reformers.[83] This brought an end to over 2,000 years imperial governance in China, and began a period of instability. In July 1917, there was an abortive attempt to restore the Qing led by Zhang Xun. Puyi was allowed to live in the Forbidden City after his abdication until 1924, when he moved to the Japanese concession in Tianjin. The Empire of Japan invaded Northeast China and founded Manchukuo there in 1932, with Puyi as its emperor. After the invasion of Northeast China to fight Japan by the Soviet Union, Manchukuo fell in 1945.

حكومة ومجتمع تشينگ

الفرد المغمور

إن أكثر ما يروعنا في هذه الحضارة هو نظام حكومتها. وإذا كانت الدولة المثالية هي التي تجمع بين الديمقراطية والأرستقراطية فإن الصينيين قد أنشأوا هذه الدولة منذ ألف عام أو تزيد؛ وإذا كانت خير الحكومات هي أقلها حكما، فقد كانت حكومة الصين خير حكومات العالم على الإطلاق. ولم يشهد التاريخ قط حكومة كان لها رعايا أكثر من رعايا الحكومة الصينية أو كانت في حكمها أطول عهدا وأقل سيطرة من تلك الحكومة.

ولسنا نقصد بهذا أن الفردية أو الحرية الفردية كان لها شأن عظيم في بلاد الصين؛ ذلك أن فكرة الفردية كانت ضعيفة في تلك البلاد وأن الفرد كان مغمورا في الجماعات التي ينتمي إليها. فقد كان أولا عضوا من أعضاء أسرة، ووحدة عابرة في موكب الحياة بين أسلافه وأخلافه؛ وكانت القوانين والعادات تحمله تبعة أعمال غيره من أفراد أسرته كما يحملون هم تبعة أعماله؛ وكان فضلا عن هذا ينتمي عادة على جمعية سرية، وإذا كان من سكان الحواضر فانه ينتمي إلى نقابة من نقابات الحرف.

وهذه كلها أمور تحد من حقه في أن يفعل ما يشاء. وكان يحيط به فضلا عن هذا طائفة من العادات القديمة ويهدده رأي عام قوي بالطرد من البلاد إذا خرج على أخلاق الجماعة أو تقاليدها خروجا خطيرا. وكانت قوة هذه النظم الشعبية التي نشأت بطبيعتها من حاجات الناس وتعاونهم الاختياري هي التي مكنت الصين من أن تحتفظ بنظامها واستقرارها رغم ما يشوب القانون والدولة من لين وضعف.

الحكم الذاتي

ولكن الصينيين ظلوا أحرارا من الناحيتين السياسية والاقتصادية في داخل هذا الإطار من نظم الحكم الذاتي التي أقاموها بأنفسهم لأنفسهم.

لقد كانت المسافات الشاسعة التي تفصل كل مدينة عن الأخرى وتفصل المدن كلها عن عاصمة الإمبراطورية، والجبال الشامخة والصحاري الواسعة والمجاري التي تتعذر فيها الملاحة أو لا تقوم عليها القناطر، وانعدام وسائل النقل والاتصال السريع وصعوبة تموين جيش كبير يكفي لفرض سلطان الحكومات المركزية على شعب تبلغ عدته أربعمائة مليون من الأنفس - كانت هذه كلها عوامل تضطر الدولة لأن تترك لكل إقليم من أقاليمها استقلالا ذاتيا يكاد أن يكون كاملا من كل الوجوه.

القرية والإقليم

وكانت وحدة الإدارة المحلية هي القرية يحكمها حكما متراخيا رؤساء العشائر بإشراق "زعيم" منهم ترشحه الحكومة. وكانت كل طائفة من القرى مجتمعة حول بلدة كبيرة تؤلف "بينا" أي مقاطعة بلغت عدتها في الصين نحو ألف وثلاثمائة. ويتألف من كل بينين أو أكثر تحكمهما معا مدينة "فو"، ومن كل فوين أو ثلاثة "داو" أي دائرة، ومن كل داوين أو أكثر "شنج" أي إقليم. وكانت الإمبراطورية في عهد المنشو تتألف من ثمانية عشر من هذه الأقاليم. وكانت الدولة تعين من قبلها موظفا في كل بين يدير شئونه، ويجبى ضرائبه، ويفصل في قضاياه، وتعين موظفا آخر في كل فو وآخر في كل داو؛ كما تعين قاضيا، وخازنا لبيت المال، وحاكما، ونائبا للإمبراطور أحيانا في كل إقليم(127). ولكن هؤلاء الموظفين كانوا يقنعون أحيانا بجباية الضرائب والفروض الأخرى والفصل في المنازعات التي يعجز المحكمون عن تسويتها بالحسنى، ويتركون حفظ النظام لسلطان العادة وللأسرة والعشيرة والنقابة الطائفية. وكان كل إقليم ولاية شبه مستقلة لا تتدخل الحكومة الإمبراطورية في أعمالها، ولا تفرض عليها شرائعها طالما كانت تدفع حصتها من الضرائب وتحافظ على الأمن والنظام في داخل حدودها. وكان انعدام وسائل الاتصال السهلة مما جعل الحكومة المركزية فكرة معنوية أكثر منها حقيقة واقعية. ومما جعل عواطف الأهلين الوطنية تنصرف في دوائرهم وأقاليمهم، ولا تتسع إلا في القليل النادر حتى تشمل الإمبراطورية بوجه عام.

تراخي القانون وصرامة العقاب

وفي هذا البناء غير المحكم كان القانون ضعيفا، بغيضا، متباينا. وكان الناس يفضلون أن تحكمهم عاداتهم وتقاليدهم، وأن يسووا نزاعهم بالتراضي خارج دور القضاء. وكانوا يعبرون عن آرائهم في التقاضي بمثل هذه الحكم والأمثال القصيرة القوية: "قاض برغوثا يعضك" و "اكسب قضيتك تخسر مالك". وكانت تمر سنين على كثير من المدن التي تبلغ عدة أهلها آلافاً مؤلفة لا ترفع فيها قضية واحدة إلى المحاكم(128) وكانت قوانين البلاد قد جمعت في عهد أباطرة تانج ولكنها كلها اقتصرت تقريبا على الجرائم ولم تبذل محاولات جدية لوضع قانون مدني. وكانت المحاكمات بسيطة سهلة لأن المحامي لم يكن يسمح له بمناقشة الخصم داخل المحكمة، وإن كان في استطاعة كتاب مرخصين من الدولة أن يعدوا في بعض الأحيان تقارير بالنيابة عن المتقاضين ويتلوها على القاضي(129). ولم يكن هناك نظام للمحلفين، ولم يكن في نصوص القوانين ما يحمي الفرد من أن يقبض عليه موظفو الدولة على حين غفلة ويعتقلوه. وكانت تؤخذ بصمات أصابع المتهمين(130)، ويلجأ أحيانا إلى تعذيبهم لكي يقروا بجرائمهم، ولم يكن هذا التعذيب الجسمي ليزيد إلا قليلا على ما يتبع الآن لهذا الغرض عينه في أكثر المدن رقيا. وكان العقاب صارما، وإن لم يكن أشّد وحشية مما كان في معظم بلاد القارة الآسيوية؛ وكان أوله قص الشعر ويليه الضرب ثم النفي من البلاد ثم الإعدام. وإذا كان المتهم ذا فضائل غير معهودة أو كان من طبقة راقية سمح له أن ينتحر(131). وكانت العقوبات تخفف أحيانا تخفيفا كريما، وكان حكم الإعدام لا يصدر في الأوقات العادية إلا من الإمبراطور نفسه. وكان الناس جميعا من الناحية النظرية سواسية أمام القانون، شأنهم في هذا كشأننا نحن في هذه الأيام. ولكن هذه القوانين لم تمنع السطو في الطرق العامة أو الارتشاء في وظائف الدولة ودور القضاء، غير أنها كان لها قسط متواضع في معاونة الأسرة والعادات الموروثة في أن تهب الصين درجة من النظام الاجتماعي والأمن والاطمئنان الشخصي لم تضارعها فيها أمة أخرى قبل القرن العشرين(132).

الإمبراطور

وكان الإمبراطور يشرف على هذه الملايين الكثيرة من فوق عرشه المزعزع. وكان يحكم من الوجهة النظرية بحقه المقدس؛ فقد كان هو "ابن السماء" وممثل الكائن الأعلى في هذه الأرض. وبفضل سلطانه الإلهي هذا كانت له السيطرة على الفصول وكان يأمر الناس أن يوفقوا بين أعمالهم وبين النظام السماوي المسيطر على العالم، وكانت كلمته هي القانون وأحكامه هي القضاء الذي لا مرد له. وكان المدبر لشؤون الدولة ورئيس ديانتها، يعين جميع موظفيها ويمتحن المتسابقين لأعلى مناصبها ويختار من يخلفه على العرش. لكن سلطانه كان يحده من الوجهة العملية القانون والعادات المرعية، فكان ينتظر منه أن يحكم من غير أن يخرج على النظم التي انحدرت من الماضي المقدس. وكان معرضا في أي وقت لأن يعزَّر على يد رجل ذي مقام كبير يسمى بالرقيب؛ وكان في واقع الأمر محوطاً بحلقة قوية من المستشارين والمبعوثين من مصلحته أن يعمل بمشورتهم، وإذا ظلم أو فسد حكمه خسر بحكم العادات المرعية وباتفاق أهل الدولة "تفويض السماء"، وأمكن خلعه بالقوة من غير أن يعد ذلك خروجا على الدين أو الأخلاق.

الرقيب

وكان الرقيب رئيس مجلس مهمته التفتيش على جميع الموظفين في أثناء قيامهم بواجباتهم، ولم يكن الإمبراطور نفسه بمنجاة من إشرافه. وقد حدث مرارا في تاريخ الصين أن عزر الرقيب الإمبراطور نفسه. من ذلك أن الرقيب سونج أشار على الإمبراطور جياه تشنج (1196-1821)، بالاحترام اللائق بمقامه العظيم طبعا، أن يراعى جانب الاعتدال في صلاته بالممثلين وبتعاطي المسكرات. فما كان من جياه تشنج إلا أن استدعى سونج للمثول أمامه، وسأله وهو غاضب أي عقاب يليق أن يوقع على من كان موظفا وقحا مثله، فأجابه سونج: "الموت بتقطيع جسمه إرباً". ولما أمره الإمبراطور باختيار عقاب أخف من هذا أجابه بقوله "إذن فليقطع رأسي" فطلب إليه مرة أخرى أن يختار عقابا أخف فاختار أن يقتل خنقا. وأعجب الإمبراطور بشجاعته وخشي وجوده بالقرب منه فعينه حاكما على إقليم إيلي(134).

المجالس الإدارية

وأضحت الحكومة المركزية على مر الزمن أداة إدارية شديدة التعقيد. وكان أقرب الهيئات إلى العرش المجلس الأعلى، ويتكون من أربعة "وزراء كبار" يرأسهم في العادة أمير من أمراء الأسرة المالكة. وكان يجتمع بحكم العادة في كل يوم في ساعات الصباح المبكرة لينظر في شؤون الدولة السياسية. وكان يعلو عنه في المنزلة، ولكن يقل عنه في السلطان، هيئة أخرى من المستشارين يسمون "بالديوان الداخلي". وكان يشرف على الأعمال الإدارية "ستة مجالس" للشؤون المدنية، والدخل، والاحتفالات، والحرب، والعقوبات، والأشغال العامة؛ وكان ثمة إدارة للمستعمرات تصرف شؤون الأقاليم النائية مثل منغوليا، وسنكيانج والتبت. ولكنها لم تكن لها إدارة للشؤون الخارجية لأن الصين لم تكن تعترف بأن في العالم دولة مساوية لها، ومن أجل ذلك لم تنشئ في بلادها للاتصال بها غير ما وضعته من النظم لاستقبال البعوث التي تحمل لها الخراج.

وكان أكبر أسباب ضعف الحكومة قلة مواردها وضعف وسائل الدفاع عن أراضيها ورفضها كل اتصال بالعالم الخارجي يعود عليها بالنفع. لقد فرضت الضرائب على أراضيها، واحتكرت بيع الملح، وعطلت نماء التجارة بما فرضته بعد عام 1821 من عوائد على انتقال البضائع على طرق البلاد الرئيسية، ولكن فقر السكان، وما كانت تعانيه من الصعاب في جباية الضرائب والمكوس، وما يتصف به الجباة من الخيانة، كل هذا قد ترك خزانة الدولة عاجزة عن الوفاء بحاجات القوى البحرية والبرية التي كان في وسعها لولا هذا العجز أن تنقذ البلاد من مذلة الغزو والهزيمة . ولعل أهم أسباب هزائمها هو فساد موظفي حكومتها؛ وذلك أن ما كان يتصف به موظفوها من جدارة وأمانة قد ضعف في خلال القرن التاسع عشر فأضحت البلاد تعوزها الزعامة الرشيدة في الوقت الذي كانت فيه نصف ثروة العالم ونصف قواه يتجمعان لسل استقلالها وانتهاب مواردها والقضاء على أنظمتها.

الإعداد للمناصب العامة

بيد أن أولئك الموظفين كانوا يختارون بوسيلة لا مثيل لها في دقتها وتعد في جملتها أجدر وسائل الاختيار بالإعجاب والتقدير، وخير ما وصل إليه العالم من الوسائل لاختيار الخدام العموميين. لقد كانت وسيلة جديرة بإعجاب أفلاطون، ولا تزال رغم عجزها وتخلي الصين عنها تقرب الصين إلى قلوب الفلاسفة. وكانت هذه الطريقة من الناحية النظرية توفق أحسن التوفيق بين المبادئ الأرستقراطية والديمقراطية: فهي تمنح الناس جميعا فرصة متكافئة لإعداد أنفسهم للمناصب العامة، ولكنها لا تفتح أبواب المناصب إلا لمن أعدوا أنفسهم لها. ولقد أنتجت خير النتائج من الوجهة العملية مدى ألف عام.

وكانت بداية هذه الطريقة في مدارس القرى - وهي معاهد خاصة ساذجة لا تزيد قليلا على حجرة واحدة في كوخ صغير - كان يقوم فيها معلم واحد بتعليم أبناء أسر القرية تعليما أوليا ينفق عليه بما يؤديه هؤلاء الأبناء من أجر ضئيل. أما النصف الفقير من السكان فقد ظل أبناؤه أميين(137). ولم تكن الدولة هي التي تنفق على تلك المدارس، ولم يكن الكهنة هم الذين يديرونها، ذلك أن التعليم قد بقى في الصين كما بقى الزواج فيه مستقلا عن الدين لا صلة بينهما سوى أن الكنفوشية كانت عقيدة المعلمين. وكانت أوقات الدراسة طويلة كما كان النظام صارما في هذه المدارس المتواضعة. فكان الأطفال يأتون إلى المعلم في مطلع الشمس ويدرسون معه حتى الساعة العاشرة، ثم يفطرون ويواصلون الدرس حتى الساعة الخامسة، ثم ينصرفون بقية النهار. وكانت العطلات قليلة العدد قصيرة الأجل، وكانت الدراسة تعطل بعد الظهر في فصل الصيف، ولكن هذا الفراغ الذي كان يصرف في العمل في الحقول كان يعوض بفصول مسائية في ليالي الشتاء. وكان أهم ما يتعلمه الأطفال كتابات كنفوشيوس وشعر تانج؛ وكانت أداة المعلم عصا من الخيزران. وكانت طريقة التعليم الحفظ عن ظهر قلب؛ فكان الأطفال الصغار يواصلون حفظ فلسفة المعلم كونج ويناقشون فيها مدرسهم حتى ترسخ كل كلمة من كلماته في ذاكرتهم وحتى يستقر بعضها في قلوبهم. وكانت الصين تأمل أن يتمكن جميع أبنائها، ومنهم الزراع أنفسهم، بهذه الطريقة القاسية الخالية من اللذة أن يصبحوا فلاسفة وسادة مهذبين، وكان الصبي يخرج من المدرسة ذا علم قليل وإدراك كبير، جاهلا بالحقائق ناضج العقل .

الترشيح بالتعليم

وكان هذا التعليم هو الأساس الذي أقامت عليه الصين - في عهد أسرة هان على سبيل التجربة وفي عهد أسرة تانج بصفة نهائية - نظام تولي المناصب العامة بالامتحان. ومن أقوال الصينيين في هذا: إن من أضر الأمور بالشعب أن يتعلم حكامه طرق الحكم بالحكم نفسه، وإن من واجبهم كلما استطاعوا أن يتعلموا طرق الحكم قبل أن يحكموا، ومن أضر الأمور بالشعب أن يحال بينه وبين تولي المناصب العامة وأن يصبح الحكم امتيازا تتوارثه فئة قليلة من أبناء الأمة؛ ولكن من الخير للشعب أن تقصر المناصب على من أعدوا لها بفضل مواهبهم وتدريبهم. وكان الحل الذي عرضته الصين لمشكلة الحكمة القديمة المستعصية هي أن تتيح لكل الرجال ديمقراطيا فرصة متكافئة لأن يدربوا هذا التدريب، وأن تقصر الوظائف أرستقراطيا على من يثبتون أنهم أليق الناس لأن يتولوها. ومن أجل هذا كانت تعقد في أوقات معينة امتحانات عامة في كل مركز من المراكز يتقدم إليها كل من شاء من الذكور متى كانوا في سن معينة.

نظام الامتحانات

وكان المتقدم إلى الامتحان يمتحن في قوة تذكره وفهمه لكتابات كنفوشيوس وفي مقدار ما يعرف من الشعر الصيني ومن تاريخ الصين، وفي قدرته على أن يكتب أبحاثا في السياسة والأخلاق كتابة تدل على الفهم والذكاء. وكان في وسع من يخفق في الامتحان أن يعيد الدرس ويتقدم إليه مرة أخرى، ومن نجح منح درجة شيو دزاي التي تؤهله لأن يكون عضوا في طبقة الأدباء ولأن يعين في المناصب الصغرى في الحكومة الإقليمية؛ وأهم من هذا أن يكون من حقه أن يتقدم إما مباشرة أو بعد استعداد جديد لامتحان آخر يعقد في الأقاليم كل ثلاث سنوات شبيه بالأول ولكنه أصعب منه. ومن خفق فيه أجاز أن يتقدم إليه مرة أخرى؛ وكان يفعل ذلك كثيرون من المتقدمين فكان يجتازه في بعض الأحيان رجال جاوزا الثمانين وظلوا طوال حياتهم يدرسون، وكثيرا ما مات الناس وهم يتأهبون لدخول هذه الامتحانات. وكان الذين ينجحون يختارون للوظائف الحكومية الصغرى، كما كان من حقهم أن يتقدموا للامتحان النهائي الشديد الذي يعقد في بكين. وكان في تلك المدينة ردهة للامتحان العام تحتوي على عشرة آلاف حجرة انفرادية يقضى فيها المتسابقون ثلاثة أيام متفرقة في عزلة تامة، ومعهم طعامهم وفراشهم، يكتبون مقالات أو رسائل في موضوعات تعلم لهم بعد دخولهم. وكانت هذه الغرف خالية من وسائل التدفئة والراحة رديئة - الإضاءة غير صحية لأن الروح لا الجسم - في رأيهم - هي التي يجب أن تكون موضع الاهتمام! وكان من الموضوعات المألوفة في هذه الامتحانات أن ينشئ المتقدم قصيدة في: "صوت المجاديف والتلال الخضراء والماء"، وأن يكتب مقالا عن الفقرة الآتية من كتابات كنفوشيوس. قال دزانج دزي: "من يك ذا كفاية ويسأل من لا كفاية له؛ ومن يك ذا علم كثير ويسأل من لا يعلم إلا القليل؛ ومن يملك ثم يتظاهر بأنه لا يملك؛ ومن يمتلئ ثم يبدي أنه فارغ" ولم يكن في أي امتحان من هذه الامتحانات كلمة واحدة عن العلوم أو الأعمال التجارية أو الصناعية؛ لأنها لم تكن تهدف إلى تبين علم الرجل بل ترمي إلى معرفة ما له من حكم صادق وخلق قويم. وكان كبار موظفي الدولة يختارون من الناجحين في هذا الامتحان النهائي.

عيوبه

وتبين على مر الزمن ما تنطوي عليه هذه الطريقة من عيوب. فقد وجد الغش سبيله إلى الحكم في الامتحان، وإن كان الغش في الامتحان أو في تقديره يعاقب عليه أحيانا بالإعدام. وأصبح شراء الوظائف بالمال كثيرا متفشيا في القرن التاسع عشر(138)، من ذلك أن موظفا صغيرا باع عشرين ألف شهادة مزورة قبل أن يكشف أمره(139). ومنها أن صورة المقالة التي تكتب في الامتحان أصبحت صورة عادية معروفة يعد المتسابقون أنفسهم لها إعدادا آلياً. كذلك كان منهج الدراسة ينزع إلى الهبوط بالثقافة إلى الصور الشكلية دون اللباب، ويحول دون الرقي الفكري لأن الأفكار التي كانت تتداول في هذه المقالات قد تحددت وتعينت خلال مئات السنين. وكان من آثارها أن أصبح الخريجون طبقة بيروقراطية ذات عقلية رسمية متعجرفة بطبيعتها، أنانية، مستبدة في بعض الأحيان وفاسدة في كثير من الأحوال؛ لا يستطيع الشعب مع ذلك أن يعزلها أو يشرف على أعمالها إلا إذا لجأ بعد يأسه إلى الطريقة الخطرة طريقة الإضراب عن طاعتها أو مقاطعتها وعدم التعامل معها. وقصارى القول أن هذا النظام كان ينطوي على كل العيوب الني يمكن أن ينطوي عليها أي نظام حكومي يبتدعه ويسيره بنو الإنسان؛ فعيوبه هي عيوب القائمين عليه لا عيوب النظام نفسه، وليس ثمة نظام آخر لم يكن فيه من العيوب من في هذا النظام .

مزاياه

أما مزاياه فهي كثيرة: فهو برئ من طريقة الترشيح وما يؤثر فيها من تيارات خفية؛ وليس فيه مجال للمساعي الدنيئة وللنفاق والخداع في تصوير النتائج، ولا تدور فيه المعارك الصورية بين الأحزاب، ولا يتأثر بالانتخابات الفاسدة ذات الجلبة والضجيج، ولا يتيح الفرصة لتسلم المركز الرفيع عن طريق الشهرة الزائفة. لقد كانت الحكومة القائمة على هذا النظام حكومة ديمقراطية على الزعامة وعلى المناصب الرفيعة. وكانت أرستقراطية في أحسن صورها، لأنها حكومة يتولاها أقدر الرجال الذين اختيروا اختيارا ديمقراطيا من بين جميع طبقات الشعب ومن كل جيل. وبفضل هذه الطريقة وجهت عقول الأمة ومطامعها وجهة الدرس والتحصيل، وكان أبطالها الذين تقتدي بهم هم رجال العلم والثقافة لا سادة المال .

ولقد كان جديرا بالإعجاب أن يجرب مجتمع من المجتمعات أن يحكمه من الناحيتين الاجتماعية والسياسية رجال أعدوا للحكم بتعلم الفلسفة والعلوم الإنسانية، ولذلك كان من شر المآسي أن تنقض قوى التطور والتاريخ القاسية التي لا ترحم ولا تلين على ذلك النظام الفذ وعلى جميع معالم الحضارة التي كان هو أهم عناصرها فتدمرها تدميرا.

السياسة

البيروقراطية

الجيش

البدايات والارهاصات

The Qing dynasty was established by conquest and maintained by armed force. The founding emperors personally organised and led the armies, and the continued cultural and political legitimacy of the dynasty depended on the ability to defend the country from invasion and expand its territory. Therefore, military institutions, leadership, and finance were fundamental to the dynasty's initial success and ultimate decay. The early military system centred on the Eight Banners, a hybrid institution that also played social, economic, and political roles.[84] The Banner system was developed on an informal basis as early as 1601, and formally established in 1615 by Jurchen leader Nurhaci (1559–1626), the retrospectively recognised founder of the Qing. His son Hong Taiji (1592–1643), who renamed the Jurchens "Manchus," created eight Mongol banners to mirror the Manchu ones and eight "Han-martial" (??; Hànjun) banners manned by Chinese who surrendered to the Qing before the full-fledged conquest of China proper began in 1644. After 1644, the Ming Chinese troops that surrendered to the Qing were integrated into the Green Standard Army, a corps that eventually outnumbered the Banners by three to one.

السلام والجمود

The use of gunpowder during the High Qing can compete with the three gunpowder empires in western Asia.[85] Manchu imperial princes led the Banners in defeating the Ming armies, but after lasting peace was established starting in 1683, both the Banners and the Green Standard Armies started to lose their efficiency. Garrisoned in cities, soldiers had few occasions to drill. The Qing nonetheless used superior armament and logistics to expand deeply into Central Asia, defeat the Dzungar Mongols in 1759, and complete their conquest of Xinjiang. Despite the dynasty's pride in the Ten Great Campaigns of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796), the Qing armies became largely ineffective by the end of the 18th century. It took almost ten years and huge financial waste to defeat the badly equipped White Lotus Rebellion (1795–1804), partly by legitimizing militias led by local Han Chinese elites. The Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), a large-scale uprising that started in southern China, marched within miles of Beijing in 1853. The Qing court was forced to let its Han Chinese governors-general, first led by Zeng Guofan, raise regional armies. This new type of army and leadership defeated the rebels but signaled the end of Manchu dominance of the military establishment.

The military technology of the European Industrial Revolution made China's armament and military rapidly obsolete. In 1860 British and French forces in the Second Opium War captured Beijing and sacked the Summer Palace. The shaken court attempted to modernise its military and industrial institutions by buying European technology. This Self-Strengthening Movement established shipyards (notably the Jiangnan Arsenal and the Foochow Arsenal) and bought modern guns and battleships in Europe. The Qing navy became the largest in East Asia. But organisation and logistics were inadequate, officer training was deficient, and corruption widespread. The Beiyang Fleet was virtually destroyed and the modernised ground forces defeated in the 1895 First Sino-Japanese War. The Qing created a New Army, but could not prevent the Eight Nation Alliance from invading China to put down the Boxer Uprising in 1900. The revolt of a New Army corps in 1911 led to the fall of the dynasty.

التمرد والعصرنة

Early during the Taiping Rebellion, Qing forces suffered a series of disastrous defeats culminating in the loss of the regional capital city of Nanjing in 1853. Shortly thereafter, a Taiping expeditionary force penetrated as far north as the suburbs of Tianjin, the imperial heartlands. In desperation the Qing court ordered a Chinese official, Zeng Guofan, to organize regional and village militias into an emergency army called tuanlian. Zeng Guofan's strategy was to rely on local gentry to raise a new type of military organization from those provinces that the Taiping rebels directly threatened. This new force became known as the Xiang Army, named after the Hunan region where it was raised. The Xiang Army was a hybrid of local militia and a standing army. It was given professional training, but was paid for out of regional coffers and funds its commanders – mostly members of the Chinese gentry – could muster. The Xiang Army and its successor, the Huai Army, created by Zeng Guofan's colleague and protégée Li Hongzhang, were collectively called the "Yong Ying" (Brave Camp).[86]

Zeng Guofan had no prior military experience. Being a classically educated official, he took his blueprint for the Xiang Army from the Ming general Qi Jiguang, who, because of the weakness of regular Ming troops, had decided to form his own "private" army to repel raiding Japanese pirates in the mid-16th century. Qi Jiguang's doctrine was based on Neo-Confucian ideas of binding troops' loyalty to their immediate superiors and also to the regions in which they were raised. Zeng Guofan's original intention for the Xiang Army was simply to eradicate the Taiping rebels. However, the success of the Yongying system led to its becoming a permanent regional force within the Qing military, which in the long run created problems for the beleaguered central government.

First, the Yongying system signaled the end of Manchu dominance in Qing military establishment. Although the Banners and Green Standard armies lingered on as a drain on resources, henceforth the Yongying corps became the Qing government's de facto first-line troops. Second, the Yongying corps were financed through provincial coffers and were led by regional commanders, weakening central government's grip on the whole country. Finally, the nature of Yongying command structure fostered nepotism and cronyism amongst its commanders, who laid the seeds of regional warlordism in the first half of the 20th century.[87]

By the late 19th century, the most conservative elements within the Qing court could no longer ignore China's military weakness. In 1860, during the Second Opium War, the capital Beijing was captured and the Summer Palace sacked by a relatively small Anglo-French coalition force numbering 25,000. The advent of modern weaponry resulting from the European Industrial Revolution had rendered China's traditionally trained and equipped army and navy obsolete. The government attempts to modernize during the Self-Strengthening Movement were initially successful, but yielded few lasting results because of the central government's lack of funds, lack of political will, and unwillingness to depart from tradition.[88]

Losing the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895 was a watershed. Japan, a country long regarded by the Chinese as little more than an upstart nation of pirates, annihilated the Qing government's modernized Beiyang Fleet, then deemed to be the strongest naval force in Asia. The Japanese victory occurred a mere three decades after the Meiji Restoration set a feudal Japan on course to emulate the Western nations in their economic and technological achievements. Finally, in December 1894, the Qing government took concrete steps to reform military institutions and to re-train selected units in westernized drills, tactics and weaponry. These units were collectively called the New Army. The most successful of these was the Beiyang Army under the overall supervision and control of a former Huai Army commander, General Yuan Shikai, who used his position to build networks of loyal officers and eventually become President of the Republic of China.[89]

المجتمع

Population growth and mobility

The population grew in numbers, density, and mobility. The population in 1700 was roughly 150 million, about what it had been a century before, then doubled over the next century, and reached a height of 450 million on the eve of the Taiping Rebellion in 1850.[90] The spread of New World crops, such as maize, peanuts, sweet potatoes, and potatoes decreased the number of deaths from malnutrition. Diseases such as smallpox were brought under control by an increase in inoculations. In addition, infant deaths were decreased due to campaigns against infanticide and improvements in birthing techniques performed by doctors and midwives and an increase in medical books available to the public.[91] European population growth in this period was greatest in the cities, but in China there was only slow growth in cities and the lower Yangzi. The greatest growth was in the borderlands and the highlands, where farmers moved to take advantage of large tracts of marshlands and forests.[92]

The population was remarkably mobile, perhaps more so than at any time in Chinese history. Millions of Han Chinese migrated to Yunnan and Guizhou in the 18th century, and also to Taiwan. After the conquests of the 1750s and 1760s, the court organised agricultural colonies in Xinjiang. This mobility also included the privately organised movement of Qing subjects overseas, largely to Southeast Asia, to pursue trade and other economic opportunities.[92]

Manchuria, however, was formally closed to Han settlement by the Willow Palisade, with the exception of some bannermen.[93] Nonetheless, by 1780, Han Chinese had become 80% of the population.[94] The relatively sparse populatikon made the territory vulnerable to Russian annexation. In response, the Qing officials proposed in 1860 to open parts of Guandong to Chinese civilian farmer settlers.[95] Late 19th century Manchuria was opened up to Han settlers, resulting in more extensive migration.[96] By the dawn of the 20th century, largely in an attempt to counteract increasing Russian influence, the Qing had abolished the existing administrative system in Manchuria, reclassified all immigrants to the region as "Han" instead of "civilians", and replaced provincial generals with provincial governors. From 1902 to 1911, 70 civil administrations were created in Manchuria, owing to the region's growing population.[97]

Social status

According to statute, Qing society was divided into relatively closed estates, of which in most general terms there were five. Apart from the estates of the officials, the comparatively minuscule aristocracy, and the degree-holding scholar-officials, there also existed a major division among ordinary Chinese between commoners and people with inferior status.[98] They were divided into two categories: one of them, the good "commoner" people, the other "mean" people who were seen as debased and servile. The majority of the population belonged to the first category and were described as liangmin, a legal term meaning good people, as opposed to jianmin meaning the mean (or ignoble) people. Qing law explicitly stated that the traditional four occupations (scholars, farmers, artisans and merchants) were "good", or having a status of commoners. On the other hand, slaves or bondservants, entertainers (including prostitutes and actors), tattooed criminals, and those low-level employees of government officials were the "mean people". Mean people were legally inferior to commoners and suffered unequal treatments, such as being forbidden to take the imperial examination.[99] Furthermore, such people were usually not allowed to marry with free commoners and were even often required to acknowledge their abasement in society through actions such as bowing. However, throughout the Qing dynasty, the emperor and his court, as well as the bureaucracy, worked towards reducing the distinctions between the debased and free but did not completely succeed even at the end of its era in merging the two classifications together.[[#cite_note-FOOTNOTERowe2009[[تصنيف:مقالات_بالمعرفة_بحاجة_لذكر_رقم_الصفحة_بالمصدر_from_May_2020]][[Category:Articles_with_invalid_date_parameter_in_template]]<sup_class="noprint_Inline-Template_"_style="white-space:nowrap;">[<i>[[المعرفة:Citing_sources|<span_title="هذه_المقولة_تحتاج_مرجع_إلى_صفحة_محددة_أو_نطاق_من_الصفحات_تظهر_فيه_المقولة'"`UNIQ--nowiki-0000008E-QINU`"'_(May_2020)">صفحة مطلوبة</span>]]</i>]</sup>-101|[100]]]

Qing gentry

Although there had been no powerful hereditary aristocracy since the Song dynasty, the gentry, like their British counterparts, enjoyed imperial privileges and managed local affairs. The status of scholar-officials was defined by passing at least the first level of civil service examinations and holding a degree, which qualified him to hold imperial office, although he might not actually do so. The gentry member could legally wear gentry robes and could talk to officials as equals. Informally, the gentry then presided over local society and could use their connections to influence the magistrate, acquire land, and maintain large households. The gentry thus included not only males holding degrees but also their wives and some of their relatives.[101]

The gentry class was divided into groups. Not all who held office were literati, as merchant families could purchase degrees, and not all who passed the exams found employment as officials, since the number of degree-holders was greater than the number of openings. The gentry class also differed in the source and amount of their income. Literati families drew income from landholding, as well as from lending money. Officials drew a salary, which, as the years went by, were less and less adequate, leading to widespread reliance on "squeeze", irregular payments. Those who prepared for but failed the exams, like those who passed but were not appointed to office, could become tutors or teachers, private secretaries to sitting officials, administrators of guilds or temples, or other positions that required literacy. Others turned to fields such as engineering, medicine, or law, which by the nineteenth century demanded specialised learning. By the nineteenth century, it was no longer shameful to become an author or publisher of fiction.[102]

The Qing gentry were marked as much by their aspiration to a cultured lifestyle as by their legal status. They lived more refined and comfortable lives than the commoners and used sedan-chairs to travel any significant distance. They often showed off their learning by collecting objects such as scholars' stones, porcelain or pieces of art for their beauty, which set them off from less cultivated commoners.[103]

Qing nobility

Family and kinship