شامانية

الشامانية Shamanism ظاهرة دينية قديمة، انتشرت في دول عديدة من العالم، خاصة في دول آسيا الوسطى والشمالية. وتأثرت بمذاهب آسيوية كبرى أمثال الميزوباتية والبوذية واللامية، دون أن تفقد بنيتها الخاصة. وقد أجمع خبراء عالميون أن مروج هولون بوير (شمال شرقي الصين) هي المنبع الرئيسي للثقافة الشامانية القديمة في العالم.

وتهتم العقيدة الشامانية بمسألة التوازن بين قوى الإنسان الذاتية الداخلية والقوى الخارجية الروحية المحيطة به. وتعدّ أن ضعف النفس البشرية الناتج من عدم الاهتمام الكافي بتربيتها وتنميتها، يساعد الأرواح والشياطين على الدخول إلى شخصية الفرد والتحكم بمشاعره وأحاسيسه، وقد يبلغ الأمر مرحلة خطيرة هي مرحلة اللبوس، فينطق الإنسان بلسان حال الشياطين ويعبر عنها. ولذاك فإن وجود الشامان ضروري لعلاج جميع مظاهر الشرور، العلاج الذي يعتمد على تنشيط القوى الذاتية لتحقيق التوازن مع القوى الكونية الشاملة، وعندئذ تُرفع عن المرء اللعنة الأبدية. فالمشكلة الرئيسة لا تكمن في الموت بحد ذاته، بل في الموت دون تحقيق هذا التوازن.[2]

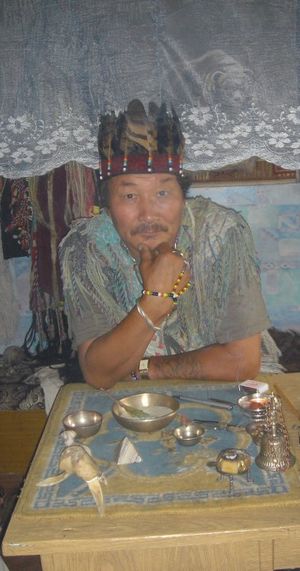

الغرض الرئيسي للشامان في أي مكان هو المعالجة. يسيطر الشامان الناجح على الأرواح التي يعمل معها، ويستطيع (كما يدعي) التواصل مع الموتى. يدرب الشامان أحياناً بواسطة "سيد الشامانات" والذي يكون أكثر خبرة منه في الشامانية. يجب على الشامان معرفة كيفية السيطرة واستخدام بعض الأمور الشخصية الطقوسية، مثل قرع الطبال أو العربة التي يقودها للسفر، كما يجب عليه حفظ تلك الأشكال والأغاني الطقوسية المهمة بالنسبة إليه.

النشأة

تُبرز الأساطير حول أصل الشامانية فكرتين بالغتي الدلالة:

- أن الآلهة هي التي خلقت الشامان الأول.

- ولكنه بسبب تعاسته حددت الآلهة قدراته.

وقد أعطيت البشرية، حسب معتقدات البوريات والياقوط (وهما قبيلتان من قبائل المغول)، شاماناً واحداً لمكافحة الأرواح الشريرة التي تسبب المرض والموت. وقد نتج هذا الشامان الأول من تزاوج بين امرأة بشرية ونسر ذي رأسين يحمل اسم الكائن الأعلى «آجي الخالق» الذي يتربّع فوق قمة شجرة العالم.

التسمية

سميت على اسم الشامان، وهو إله سماوي حاكم، أصبح إلهاً مفارقاً. وهو إله خالق، ويتكاثر إلى ما لا نهاية، وتُفسر أعماله (العالم والإنسان) بالتدخل الماكر من ضد شيطاني (الجان والأرواح الشريرة). فالشامان لاهوتي وشيطاني في آن واحد، وهو متخصص بالانتشاء (الوجد)، ورجل طيب ومساعد على الصيد، كما أنه معلم، وساحر، ومدافع عن الجماعة، وهو في بعض المجتمعات مثقف وشاعر وقاض. وللشامان قوى وقدرات متعددة، ناتجة من تجاربه التلقينية، ومعارفه للنظام الروحي، فهو متآلف مع أرواح الأحياء والأموات، ومع الآلهة والشياطين، ومع ما لا يحصى من الوجوه الغيبية التي لا يراها البشر. وبفضل هذه التجارب يتعلم الشامان جميع وسائل منع الشرور والأمراض والدفاع عن أفراد جماعته أو قبيلته، وهو لذلك يتحمل موتاً طقوسياً، ينزل إلى الجحيم، وأحياناً يصعد إلى السماء.

علم الاجتماع

الاعتقاد

ويصبح المرء شاماناً إما بإلهام عفوي (الدعوة أو الاختيار)، أو بانتقال إرثي للصفة الشامانية، أو بقرار شخصي، أو بإرادة القبيلة في بعض الحالات النادرة. ومهما كانت طريقة الاختيار فلا يعترف بالشامان إلا بعد تلقيه تعليماً مزدوجاً من نظام وجدي (أحلام، رؤى، ارتعاشات)، ومن نظام تقليدي (صياغات شامانية، أسماء ووظائف الأرواح، أشكال وأسماء الآلهة، وعلم أنساب القبيلة، واللغة السرية، أسرار الصنعة، وغير ذلك).

وقد يكون هذا التعليم المزدوج «التلقي» علنياً، أو قد يجري في الحلم أو في التجربة الوجدية الصوفية. وتتسم هذه الفترة من الحضانة أو الإعداد بأمارات حادة، إذ يصبح الشاب غريب السلوك، عصبي المزاج، يلجأ إلى الغابات، ويتغذى بقشور الأشجار، ويلقي بنفسه في الماء والنار، ويجرح نفسه بالسكاكين، ويكون له تبصرات رؤوية (رؤى تنبؤية). وإذا أخفق المرشح لمنصب الشامان في تجاوز هذه المراحل التلقينية، فإن الشياطين والأرواح الشريرة تتمكن منه، ويصبح عرضة للمشكلات الحياتية الروحية منها والجسدية.

ويوجد لدى البوريات والجولد والآلطيين والثونغور والمانشو وغيرهم حفلات عامة للتلقين. وتتطلب هذه الحفلات عند البوريات، مثلاً، تثبيت شجرة سندر صلبة في خيمة، حيث تكون جذورها في الموقد ورأسها يخرج من ثقب الدخان، وتسمى هذه الشجرة «حارس الباب» لأنها تفتح للشامان مدخل السماء، ويتسلق المتدرب الشجرة، وعند خروجه من ثقب الدخان يصرخ بقوة مستدعياً الآلهة، ثم يتجه إلى مكان بعيد عن القرية، مغروس بأشجار السندر، ويضحي بتيس، فيدهن جسمه ورأسه وعينيه وأذنيه بالدم، بينما يدق الشامانيون الآخرون بالطبول، ومن ثم يتسلق المعلم ـ الشامان شجرةًً ويجري في قمتها تسعة جروح، وعليه أن يتسلق تسع شجرات ترمز إلى السماوات التسع وبحسب اعتقادهم، هذا الطقس التلقيني هو أساس اجتماعات الشامانات الألطية. ويظهر اهتمام الشامان بالصعود إلى السماء للتكريس، ولذلك تتمتع الشجرة الشامانية باحترام كبير كالشجرة الكونية.

يؤدي الشامان دوراً رئيساً في الحياة الدينية والاجتماعية للجماعة، لما له من قدرات على شفاء الأمراض، وطرد الشياطين والأرواح الشريرة، ومحاربة السحر الأسود، والتنبّؤ والتبصّر، والدفاع عن التكامل النفسي للجماعة. وبصورة عامة فالشامان يدافع عن الحياة والصحة والخصب وعالم النور ضد الموت والمرض والعقم وسوء الحظ.

وبفضل أهلية الشامان للسفر في عوالم ما بعد الطبيعة، ورؤية الكائنات ما فوق البشرية، فإنه يتمكن من معرفة الموت. وقد نتج من ذلك عدد من أفكار وقصص ميثولوجيا الموت التي اكتسبت أشكالاً وصوراً محترمة. وتذكّر مغامرات الشامان في العالم الآخر والتجارب التي يتعرض لها في هبوطاته الوجدية إلى الجحيم وصعوداته إلى السماء، بمغامرات الشخصيات الرئيسة في الحكايات الشعبية وأبطال الأدب الملحمي. ومن الراجح أن عدداً كبيراً من موضوعات وبواعث وصور ونماذج الأدب الملحمي (عند التتار مثلاً)، هي، في التحليل الأخير، من مصدر انتشائي، وهي، في هذا المعنى، مستعارة من قصص الشامانيين الذين رووا أسفارهم ومغامراتهم في العوالم الماورائية.

ومن الراجح أيضاً أن الغبطة قبل الانتشائية قد كوّنت واحداً من مصادر الشعر الغنائي، لما يحصل أثناء رعدة الشامان من ضرب الطبول، ودعوة الأرواح، ومخاطبتها بلغة غامضة أو بلغة الحيوان، والصراخ، والاهتزاز والإيقاعات.

ولا شك في أن المعجزات الشامانية لعروض المآثر السحرية، كالدوران مع النار ومعجزات أخرى، تكشف عن عالم خرافي للآلهة والسحرة، يبدو فيه كل شيء ممكناً، ويدعم الأديان البدائية التقليدية، ويثير ويغذي الخيال، ويزيل الحواجز بين الحلم والحقيقة، ويفتح الباب نحو العوالم المسكونة بالآلهة والموتى والأرواح.

الممارسات

التاريخ

ما تزال الشامانية قيد الممارسة حتى الآن في العديد من أرجاء العالم، تحت مسميات مختلفة كثيرة. على سبيل المثال، سانگوما هو المصطلح المستخدم من قبل بعض سكان جنوب أفريقيا. حتى في يومنا هذا، تعتمد الكثير من المناطق على المداوي التقليدي لمعالجة المرض. وقد يلجأ شعب إكسهوزا للسانغوما (يسار) من أجل المساعدة.[8]

نشأ العديد من تقاليد الشامان في سيبيريا. وهذه تتضمن التيبتية، المنغولية، الكورية، اليابانية، وتلك الخاصة بالأمريكيين الأصليين، من الإسكيمو في أقصى الشمال إلى المجتمعات الأصلية في جنوب أمريكا. ويحتفظ الفلكلور الأوروبي ببقايا التقاليد الشامانية المبكرة التي جاءت من سيبيريا أيضا. وربما تجسدت تلك في عرافة القرون الوسطى لكننا لانعلم شيئا عن ممارستها. وتأتي الروايات الباقية من السلطات الكنيسة التي اعتبرت العرافة عمل الشيطان وعملت بفاعلية لتدميرها. وتقول رواياتها الرهيبة التي تفصل أن الطقوس الشيطانية وعبادة الشيطان كانت في معظمها من نسج الخيال. لكنها توحي، رغم ذلك، بأن العرافة تبنت بعض الطقوس المسيحية.

تعرف هذه النزعة في تبني ممارسات من تقاليد أخرى بالتوفيق بين المعتقدات. وقد شاعت حول العالم. على سبيل المثال، نشأ عدد من الأديان في الأمريكيتين بين العبيد الأفارقة وكانت مبنية على التقاليد الأفريقية الروحانية (والشامانية) لكنها دمجت عناصر مسيحية وعناصر أخرى. الفودو الهاييتي، السانتيريا الكوبية، والكاندومبلي البرازيلية هي أمثلة على تلك الأديان، التي تجمع بين الكهانة وممارسات المعالجة. ورغم أن الكنيسة المسيحية تشجب هذه التقاليد، فهي تبقى جزءا حيويا من الدين في الأمريكيتين.

الاختلافات الاقليمية

النوع والجنسانية

اوروپا

قبرص

آسيا

الصين

كوريا

أما بالنسبة للشامانية في كوريا فهي متعلقة أساساً بعالم الأرواح. الشامان هم سحرة دينيون يقولون بأن لديهم قوة تتغلب على النيران، ويستطيعون إنجاز الأمور عن طريق الجلسات تحضير الأرواح التي فيها تغادر أرواحهم أجسامهم إلى عوالم الروح أو تحت الأرض حتى تستمر بمعالجة المهمات.[9]

اليابان

للشامانية أيضاً وجود في ديانة الشنتو في اليابان، وممارساتهم متعلقة بشكل رئيسي بالطقوس القروية. وفي الهند الصينية، تهتم ممارسات الشامان بشكل رئيسي بمعالجة المرضى.

صربيا

آسيا الوسطى

الأزياء والحلي

الشامانية في روسيا القيصرية والسوڤيتية

التقاليد الآسيوية الأخرى

Inuit and Yupik cultures

التنوع مع بعض الديانات المشابهة

أفريقيا

الأمريكتان

أمريكا الشمالية

شعوب الإسكيمو و الأمريكان الأصليون

استئصال الشامانية في أمريكا الشمالية

أمريكا الجنوبية

الشامانية في أمريكا الوسطى

The Maya people of Guatemala, Belize, and Southern Mexico practice a highly sophisticated form of shamanism based upon astrology and a form of divination known as "the blood speaking", in which the shaman is guided in divination and healing by pulses in the veins of his arms and legs.

الشامانية في القطب الشمالي

أمازونيا

ماپوتشه

فويگو

أوقيانوسيا

الشامانية الغربية المعاصرة

نقد مصطلح “شامان” أو “الشامانية”

انظر أيضا

هوامش

- ^ Hoppál, Mihály (2005). Sámánok Eurázsiában (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-8295-3 2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) pp. 77, 287; Znamensky, Andrei A. (2005). "Az ősiség szépsége: altáji török sámánok a szibériai regionális gondolkodásban (1860–1920)". In Molnár, Ádám (ed.). Csodaszarvas. Őstörténet, vallás és néphagyomány. Vol. I (in Hungarian). Budapest: Molnár Kiadó. pp. 117–134. ISBN 9632182006.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link), p. 128 - ^ "الشامانية". الموسوعة العربية. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ H.B. Paksoy, PhD. "In the Beginning was Tengri, Part 1".

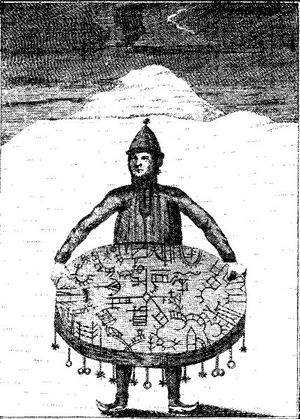

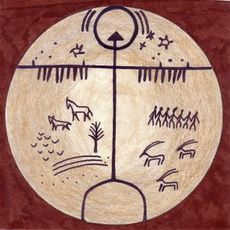

A diagram of Tengriist metaphysics on a shaman's drum. At the center is a world-tree connecting the three dimensions of the underworld, middleworld and upperworld.

- ^ Alexander Eliot (1976). Myths. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 77.

The world tree appears again in this drawing from a Shaman drum... with its roots in the underworld it rises through the inhabited earth to penetrate the realm of the gods.

- ^ Circle of Tengerism. "Mongolian Cosmology".

The other important symbol of the world center is the turge tree, which creates an axis as well as a pole for ascent and decent. Siberian and Mongolian traditions locate the tree at the center of the world, but also in the south, where the upper and middle worlds touch.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ Hoppál 2005: 117

- ^ Hoppál 2005: 259

- ^ الشامانية في العصر الحالي، planetseed

- ^ الشامانية

- ^ Fienup-Riordan, Ann. 1994:206

المصادر

- Barüske, Heinz (1969). Eskimo Märchen. Die Märchen der Weltliteratur (in German). Düsseldorf • Köln: Eugen Diederichs Verlag.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The title means: “Eskimo tales”, the series means: “The tales of world literature”. - Boglár, Lajos (2001). A kultúra arcai. Mozaikok a kulturális antropológia köreiből. TÁRStudomány (in Hungarian). Budapest: Napvilág Kiadó. ISBN 9639082945.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The title means “The faces of culture. Mosaics fom the area of cultural anthropology”. - Bolin, Hans (2000). "Animal Magic: The mythological significance of elks, boats and humansin north Swedish rock art". Journal of Material Culture. 5(2): 153-176.

- Czaplicka, M. A. (1914). "Types of shaman". Shamanism in Siberia. Aboriginal Siberia. A study in social anthropology. preface by Marett, R. R. Sommerville College, University of Oxford, Clarendon Press. ISBN 1605060607.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Dana, Kathleen Osgood (2004 summer). "Áillohaš and his image drum: the native poet as shaman" (PDF). Nordlit. Faculty of Humanities, University of Tromsø. 15.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Deschênes, Bruno (2002). "Inuit Throat-Singing". Musical Traditions. The Magazine for Traditional Music Throughout the World.

- Diószegi, Vilmos (1960). Sámánok nyomában Szibéria földjén. Egy néprajzi kutatóút története (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The book has been translated to English: Diószegi, Vilmos (1968). Tracing shamans in Siberia. The story of an ethnographical research expedition. Translated from Hungarian by Anita Rajkay Babó. Oosterhout: Anthropological Publications. - Diószegi, Vilmos (1962). Samanizmus. Élet és Tudomány Kiskönyvtár (in Hungarian). Budapest: Gondolat.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The title means: “Shamanism”. - Diószegi, Vilmos (1998) [1958]. A sámánhit emlékei a magyar népi műveltségben (in Hungarian) (first reprint ed.). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963 05 7542 6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The title means: “Remnants of shamanistic beliefs in Hungarian folklore”. - Eliade, Mircea (1983). Le chamanisme et les techniques archaïques de'l extase. Paris: Éditions Payot.

- Eliade, Mircea (2001). A samanizmus. Az extázis ősi technikái. Osiris könyvtár (in Hungarian). Budapest: Osiris. ISBN 963 379 755 1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) Translated from Eliade 1983. - Fienup-Riordan, Ann (1994). Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup'ik Eskimo Oral Tradition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0585121907.

- Fock, Niels (1963). Waiwai. Religion and society of an Amazonian tribe. Nationalmuseets skrifter, Etnografisk Række (Ethnographical series), VIII. Copenhagen: The National Museum of Denmark.

- Freuchen, Peter (1961). Book of the Eskimos. Cleveland • New York: The World Publishing Company. ISBN 0449308022.

- Gusinde, Martin (1966). Nordwind—Südwind. Mythen und Märchen der Feuerlandindianer (in German). Kassel: E. Röth.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The title means: “Northern wind, southern wind. Myths and tales of Fuegians”. - Hajdú, Péter (1975). "A rokonság nyelvi háttere". In Hajdú, Péter (ed.). Uráli népek. Nyelvrokonaink kultúrája és hagyományai (in Hungarian). Budapest: Corvina Kiadó. ISBN 963 13 0900 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The title means: “Uralic peoples. Culture and traditions of our linguistic relatives”; the chapter means “Linguistical background of the relationship”. - {{{author}}}, Shamanism: An Archaic and/or Recent System of Beliefs., Nicholson, Shirley, "Shamanism", Quest Books; 1st edition (May 25, 1987), [[{{{date}}}]].

- Hoppál, Mihály (1994). Sámánok, lelkek és jelképek (in Hungarian). Budapest: Helikon Kiadó. ISBN 963 208 298 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The title means “Shamans, souls and symbols”. - Hoppál, Mihály (1998). "A honfoglalók hitvilága és a magyar samanizmus". Folklór és közösség (in Hungarian). Budapest: Széphalom Könyvműhely. pp. 40–45. ISBN 963 9028 142.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The title means “The belief system of Hungarians when they entered the Pannonian Basin, and their shamanism”. - Hoppál, Mihály (2005). Sámánok Eurázsiában (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-8295-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The title means “Shamans in Eurasia”, the book is published also in German, Estonian and Finnish. Site of publisher with short description on the book (in Hungarian). - Hoppál, Mihály (2006a). "Sámánok, kultúrák és kutatók az ezredfordulón". In Hoppál, Mihály & Szathmári, Botond & Takács, András (ed.). Sámánok és kultúrák. Budapest: Gondolat. pp. 9–25. ISBN 963 9450 286.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) The chapter title means “Shamans, cultures and researchers in the millenary”, the book title means “Shamans and cultures”. - Hoppál, Mihály (2006b). "Sámánság a nyenyecek között". In Hoppál, Mihály & Szathmári, Botond & Takács, András (ed.). Sámánok és kultúrák. Budapest: Gondolat. pp. 170–182. ISBN 963 9450 286.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) The chapter title means “Shamanhood among the Nenets”, the book title means “Shamans and cultures”. - Hoppál, Mihály (2006c). "Music of Shamanic Healing". In Gerhard Kilger (ed.). Macht Musik. Musik als Glück und Nutzen für das Leben. Köln: Wienand Verlag. ISBN 3879098654.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Hoppál, Mihály (2007b). "Is Shamanism a Folk Religion?". Shamans and Traditions (Vol 13). Bibliotheca Shamanistica. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 11–16. ISBN 978 963 05 8521 7.

- Hoppál, Mihály (2007c). "Eco-Animism of Siberian Shamanhood". Shamans and Traditions (Vol 13). Bibliotheca Shamanistica. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 17–26. ISBN 978 963 05 8521 7.

- Hugh-Jones, Christine (1980). From the Milk River: Spatial and Temporal Processes in Northwest Amazonia. Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521225442.

- Hugh-Jones, Stephen (1980). The Palm and the Pleiades. Initiation and Cosmology in Northwest Amazonia. Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521219523.

- Kleivan, Inge (1985). Eskimos: Greenland and Canada. Iconography of religions, section VIII, "Arctic Peoples", fascicle 2. Leiden, The Netherlands: Institute of Religious Iconography • State University Groningen. E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-07160-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lawlor, Robert (1991). Voices Of The First Day: Awakening in the Aboriginal dreamtime. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International, Ltd. ISBN 0-89281-355-5

- Menovščikov, G. A. (= Г. А. Меновщиков) (1968). "Popular Conceptions, Religious Beliefs and Rites of the Asiatic Eskimoes". In Diószegi, Vilmos (ed.). Popular beliefs and folklore tradition in Siberia. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Merkur, Daniel (1985). Becoming Half Hidden: Shamanism and Initiation among the Inuit. : Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis • Stockholm Studies in Comparative Religion. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. ISBN 91-22-00752-0.

- Nagy, Beáta Boglárka (1998). "Az északi szamojédok". In Csepregi, Márta (ed.). Finnugor kalauz. Panoráma (in Hungarian). Budapest: Medicina Könyvkiadó. pp. 221–234. ISBN 963 243 813 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The chapter means “Northern Samoyedic peoples”, the title means Finno-Ugric guide. - Nattiez, Jean Jacques. Inuit Games and Songs • Chants et Jeux des Inuit. Musiques & musiciens du monde • Musics & musicians of the world. Montreal: Research Group in Musical Semiotics, Faculty of Music, University of Montreal.. The songs are online available from the ethnopoetics website curated by Jerome Rothenberg.

- Noll, Richard; Shi, Kun (2004). "Chuonnasuan (Meng Jin Fu), The Last Shaman of the Oroqen of Northeast China" (PDF). 韓國宗敎硏究 (Journal of Korean Religions). Vol. 6. Seoul KR: 西江大學校. 宗教硏究所 (Sŏgang Taehakkyo. Chonggyo Yŏnʾguso.). pp. 135–162. Retrieved 2008-07-30.. It describes the life of Chuonnasuan, the last shaman of the Oroqen of Northeast China.

- Pentikäinen, Juha (1995). "The Revival of Shamanism in the Contemporary North". In Tae-gon Kim & Mihály Hoppál (ed.). Shamanism in Performing Arts. Bibiotheca Shamanistica (Vol. 1). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 263–272. ISBN 963 05 6848 9.

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo (1997). Rainforest Shamans: Essays on the Tukano Indians of the Northwest Amazon. Dartington: Themis Books. ISBN 0-9527302-4-3.

- Reinhard,, Johan (1976) "Shamanism and Spirit Possession: The Definition Problem." In Spirit Possession in the Nepal Himalayas, J. Hitchcock & R. Jones (eds.), New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, pp. 12–20.

- Turner, Robert P.; Lukoff, David; Barnhouse, Ruth Tiffany & Lu, Francis G. (1995) Religious or Spiritual Problem. A Culturally Sensitive Diagnostic Category in the DSM-IV. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, Vol.183, No. 7, pp. 435–444

- Vitebsky, Piers (1995). The Shaman (Living Wisdom). Duncan Baird. ISBN 0705430618.

- Vitebsky, Piers (1996). A sámán. Bölcsesség • hit • mítosz (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magyar Könyvklub • Helikon Kiadó. ISBN 963208361X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) Translation of Vitebsky 1995 - Vitebsky, Piers (2001). The Shaman: Voyages of the Soul - Trance, Ecstasy and Healing from Siberia to the Amazon. Duncan Baird. ISBN 1-903296-18-8.

- Voigt, Vilmos (1966). A varázsdob és a látó asszonyok. Lapp népmesék. Népek meséi (in Hungarian). Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The title means: “The magic drum and the clairvoyant women. Sami folktales”, the series means: “Tales of folks”. - Voigt, Miklós (2000). "Sámán — a szó és értelme". Világnak kezdetétől fogva. Történeti folklorisztikai tanulmányok (in Hungarian). Budapest: Universitas Könyvkiadó. pp. 41–45. ISBN 9639104396.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) The chapter discusses the etymology and meaning of word “shaman”.

قراءات إضافية

- الفرد ميترو، الشامانية عند هنود الشاكو الأكبر، في مجموعة باحثين، السحر من منظور إثنولوجي، ترجمة محمد أسليم، مكناس (مطبعة سندي، المغرب 1998).

- فراس السواح، موسوعة تاريخ الأديان (دار علاء الدين، 2003).

- Jeanne Archterberg, Imagery in Healing Shamanism and Modern Medicine (Shambala 2002).

- Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology. 1959; reprint, New York and London: Penguin Books, 1976. ISBN 0-14-019443-6

- Richard de Mille, ed. The Don Juan Papers: Further Castaneda Controversies. Santa Barbara, CA: Ross-Erikson, 1980.

- George Devereux, "Shamans as Neurotics", American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 63, No. 5, Part 1. (Oct., 1961), pp. 1088–1090.

- Jay Courtney Fikes, Carlos Castaneda: Academic Opportunism and the Psychedelic Sixties, Millennia Press, Canada, 1993ISBN 0-9696960-0-0

- Graham Harvey, ed. Shamanism: A Reader. New York and London: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0-415-25330-6.

- Åke Hultkrantz (Honorary Editor in Chief): Shaman. Journal of the International Society for Shamanistic Research

- Philip Jenkins, Dream Catchers: How Mainstream America Discovered Native Spirituality. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-19-516115-7

- Alice Kehoe, Shamans and Religion: An Anthropological Exploration in Critical Thinking. 2000. London: Waveland Press. ISBN 1-57766-162-1

- Åke Ohlmarks 1939: Studien zum Problem des Schamanismus. Gleerup, Lund.

- Jordan D. Paper, The Spirits are Drunk: Comparative Approaches to Chinese Religion, Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1995. ISBN 0-7914-2315-8

- Malidoma Patrice Some. Of Water and the Spirit: Ritual, Magi, and Initiaion in the Life of an African Shaman. New York: Penguin Group. 1994. ISBN 0-87477-762-3

- Barbara Tedlock, Time and the Highland Maya,U. of New Mexico Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8263-1358-2

- Piers Vitebsky, The Shaman: Voyages of the Soul - Trance, Ecstasy and Healing from Siberia to the Amazon, Duncan Baird, 2001. ISBN 1-903296-18-8

- Michael Winkelman, (2000) Shamanism: The Neural Ecology of Consciousness and Healing. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

- Andrei Znamenski, ed. Shamanism: Critical Concepts, 3 vols. London: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0-415-31192-6

- Andrei Znamenski, Shamanism in Siberia: Russian Records of Siberian Spirituality. Dordrech and Boston: Kluwer/Springer, 2003. ISBN 1-4020-1740-5

- Andrei Znamenski, The Beauty of the Primitive: Shamanism and the Western Imagination.Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-19-517231-0

- 色音, 东北亚的萨满教:韩中日俄蒙萨满教比较研究(Northeast Asia Shamanism: Compare studies of Shamanism in Korea, China, Japan, Russia and Mongolia).中国社会科学出版社, Mar. 1998. ISBN 7-5004-2193-1

وصلات خارجية

- Chinese Shamanka - Short documentary about mop-nyit ceremony in Sichuan.

- A. Asbjorn Jon. "Shamanism and the Image of the Teutonic Deity, Óðinn" (PDF). It considers cross cultural similarities in shamanic belief.

- Lintrop, Aado. "Studies in Siberian Shamanism and Religions of the Finno-Ugrian Peoples". Folk Belief and Media Group of the Estonian Literary Museum.

- NAFPS - New Age Frauds and Plastic Shamans is a First Nations (American Indian) group devoted to alerting seekers about fraudulent teachers, and helping them avoid being exploited or participating in exploitation.

- Richard, Noll (2004). "Chuonnasuan (Meng Jin Fu). The Last Shaman of the Oroqen of Northeast China" (PDF). Journal of Korean Religions (6): 135–162.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) It describes the life of Chuonnasuan, the last shaman of the Oroqen of Northeast China. - Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff (1999). "A View from the Headwaters". The Ecologist. 29 (4).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) It discusses the symbolics of shamanism of Amazonian indigenous groups, and also its "ecological" functions: avoiding the depletion of scare resources. - Sem, Tatyana. "Shamanic Healing Rituals". Russian Museum of Ethnography.

- Shamanism in Siberia

- The Spirit Foundation An NGO protecting cultural aspects of shamanism including the international shamananic network

- AFECT A charitable cultural organization protecting deep shamanism in northern Thailand

- The shaman — trailer. Nganasan tribe (streamed). Youtube.

- Videos of Tatiana Urkachan Tungus Shaman Woman (streamed). Youtube.

- "An Ethnographic and Historical Study of Shamanism in Afghanistan" by Muhammad Humayun Sidky

- Video "Shaman trip" -

- Sacred Hoop Magazine - a leading international magazine on shamanism and neoshamanic practice