نورحاجي

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

نورحاجي (بالمانچو: ![]() ؛ simplified Chinese: 努尔哈赤; traditional Chinese: 努爾哈赤; pinyin: Nǔ'ěrhāchì؛ بدلاً من نورحاچي Nurhachi؛ 21 فبراير 1559 – 30 سبتمبر 1626)، هو زعيم جورچن بارز، إزدادت شهرته في منشوريا في القرن السادس عشر. كان نورحاجي ينتمي لعشيرة آيشن-جيورو، حكم من 1616 حتى وفاته في سبتمبر 1626.

؛ simplified Chinese: 努尔哈赤; traditional Chinese: 努爾哈赤; pinyin: Nǔ'ěrhāchì؛ بدلاً من نورحاچي Nurhachi؛ 21 فبراير 1559 – 30 سبتمبر 1626)، هو زعيم جورچن بارز، إزدادت شهرته في منشوريا في القرن السادس عشر. كان نورحاجي ينتمي لعشيرة آيشن-جيورو، حكم من 1616 حتى وفاته في سبتمبر 1626.

قام نورحاجي بإعادة تنظيم وتوحيد قبائل الجورچن المختلفة (فيما بعد شعب منچو")، ووحد نظام الموانع الثمانية العسكري، وفي النهاية قام بالهجوم على أسرة مينگ وأسرة جوسون الكورية. ضمه لمحافظة لياونينگ في شمال شرق الصين مهد لغزو بقية الصين على يد أحفاده، الذين قاموا بتأسيس أسرة تشينگ عام 1644. ويرجع له الفضل أيضاً في تأسيس نظام كتابة لغة المنچو.

الاسم والألقاب

حياته المبكرة

توحيد قبائل الجرچن

In 1593, the Yehe called upon a coalition of nine tribes: the Hada, Ula, Hoifa, Khorchin Mongols, Sibe, Guwalca, Jušeri, Neyen, and the Yehe themselves to attack the Jianzhou Jurchens. The coalition was defeated at the Battle of Gure and Nurhaci emerged victorious.[1]

From 1599 to 1618, Nurhaci set out on a campaign against the four Hulun tribes. He began by attacking the Hada in 1599 and conquering them in 1603. Then in 1607, Hoifa was also conquered with the death of its beile Baindari, followed by an expedition against Ula and its beile Bujantai in 1613, and finally the Yehe and its beile Gintaisi at the Battle of Sarhu in 1619.

In 1599, Nurhaci gave two of his translators, Erdeni Baksi ('Jewel Teacher' in Mongolian) and Dahai Jargūci,[2] the task of creating a Manchu alphabet by adapting the Mongolian script.

In 1606, he was granted the title of Kundulun Khan by the Mongols.

In 1616, Nurhaci declared himself Khan and founded the Jin dynasty (aisin gurun), often called the Later Jin in reference to the legacy of the earlier Jurchen Jin dynasty of the 12th century. He constructed a palace at Mukden (present-day Shenyang, Liaoning). The "Later Jin" was renamed to "Qing" by his son Hong Taiji after his death in 1626, however Nurhaci is usually referred to as the founder of the Qing dynasty.

In order to help with the newly organized administration, five of his trusted companions were appointed as his chief councilors, Anfiyanggū, Eidu, Hūrhan, Fiongdon, and Hohori.

Only after he became Khan did he finally unify the Ula (clan of his consort Lady Abahai, mentioned below) and the Yehe, the clan of his consort Monggo Jerjer.

Nurhaci chose to variously emphasize either differences or similarities in lifestyles with other peoples like the Mongols for political reasons.[3] Nurhaci said to the Mongols that "The languages of the Chinese and Koreans are different, but their clothing and way of life is the same. It is the same with us Manchus (Jurchen) and Mongols. Our languages are different, but our clothing and way of life is the same." Later Nurhaci indicated that the bond with the Mongols was not based in any real shared culture, rather it was for pragmatic reasons of "mutual opportunism", when he said to the Mongols: "You Mongols raise livestock, eat meat and wear pelts. My people till the fields and live on grain. We two are not one country and we have different languages."[4]

When the Jurchens were reorganized by Nurhaci into the Eight Banners, many Manchu clans were artificially created as a group of unrelated people founded a new Manchu clan (mukun) using a geographic origin name such as a toponym for their hala (clan name).[5] The irregularities over Jurchen and Manchu clan origin led to the Qing trying to document and systematize the creation of histories for Manchu clans, including manufacturing an entire legend around the origin of the Aisin Gioro clan by taking mythology from the northeast.[6]

تحدي المينگ

In 1618, Nurhaci commissioned a document entitled the Seven Grievances in which he enumerated seven problems with Ming rule and began to rebel against the domination of the Ming dynasty. A majority of the grievances dealt with conflicts against Yehe, and Ming favouritism of Yehe.

Nurhaci led many successful engagements against the Ming Chinese, the Koreans, the Mongols, and other Jurchen clans, greatly enlarging the territory under his control.

The first capitals of the state established by Nurhaci were Fe Ala and Hetu Ala.[7][8][9][10][11] Han Chinese participated in the construction of Hetu Ala, the capital of Nurhaci's state.[12]

Defectors from the Ming side played a massive role in the Qing conquest of the Ming. Ming generals who defected to the Manchus were often married to women from the Aisin Gioro clan while lower-ranked defectors were given non-imperial Manchu women as wives. Nurhaci arranged for a marriage between one of his granddaughters and the Ming general Li Yongfang (李永芳) after Li surrendered Fushun in Liaoning to the Manchus in 1618 as the result of the Battle of Fushun.[13][14][15][16][17] His son Abatai's daughter was married to Li Yongfang.[18][19][20][21] The offspring of Li received the "Third Class Viscount" (三等子爵; sān děng zǐjué) title.[22] Li Yongfang was the great great great grandfather of Li Shiyao 李侍堯.[23][24]

The Han prisoner of war Gong Zhenglu (Onoi) was appointed to instruct Nurhaci's sons and received gifts of slaves, wives, and a domicile from Nurhaci after Nurhaci rejected offers of payment to release him back to his relatives.[25]

Nurhaci had treated Han in Liaodong differently according to how much grain they had, those with less than 5 to 7 sin were treated like chattel while those with more than that amount were rewarded with property. Due to a revolt by Han in Liaodong in 1623, Nurhachi, who previously gave concessions to conquered Han subjects in Liaodong, turned against them and ordered that they no longer be trusted and enacted discriminatory policies and killings against them, while ordering that Han who assimilated to the Jurchen (in Jilin) before 1619 be treated equally as Jurchens were and not like the conquered Han in Liaodong.

بحلول مايو 1621، كان نورحاجي قد فتح مدينتي لياويانگ وشنيانگ. In April 1625, he designated Shenyang the new capital city, which would hold that status until the Qing conquest of the Ming in 1644.[26]

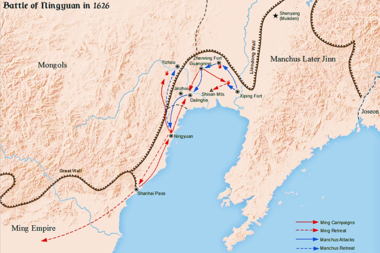

Finally in 1626, Nurhaci suffered the first serious military defeat of his life at the hands of the Ming general Yuan Chonghuan. Nurhaci was wounded by the Portuguese-made cannons in Yuan's army at the معركة نينگيوان. Unable to recover either physically or mentally, he died two days later in Aiji Fort (靉雞堡; in present-day Da'aijinbao Village, Dijia Township, Yuhong District, Shenyang) on 30 September at the age of 67. His tomb, Fu Mausoleum (Chinese: 福陵; pinyin: Fúlíng)، تقع شرق شنيانگ.

The first Manchu translations of Chinese works were the Six Secret Teachings (六韜), Sushu 素書, and Three Strategies of Huang Shigong (三略), all Chinese military texts dedicated to the arts of war due to the Manchu interests in the topic, like Sun-Tzu's work The Art of War.[27][28] The military related texts which were translated into Manchu from Chinese were translated by Dahai.[29]

Manchu translations of Chinese texts included the Ming penal code and military texts were performed by Dahai.[30] These translations were requested of Dahai by Nurhaci.[31] The military text Wuzi was translated into Manchu along with The Art of War.[32]

ذكراه

Among the most lasting contributions Nurhaci left his descendants was the establishment of the Eight Banners, which would eventually form the backbone of the military that dominated the Qing Empire. The status of Banners did not change much over the course of Nurhaci's lifetime, nor in subsequent reigns, remaining mostly under the control of the royal family. The two elite Yellow Banners were consistently under Nurhaci's control. The two Blue Banners were controlled by Nurhaci's brother Šurhaci until he died, at which point the Blue Banners were given to Šurhaci's two sons, Chiurhala and Amin. Nurhaci's eldest son, Cuyen, controlled the White Banner for most of his father's reign until he rebelled. Then the Bordered White Banner was given to Nurhaci's grandson and the Plain White was given to his eighth son and heir, Hong Taiji. However, by the end of Nurhaci's reign, Hong Taiji controlled both White Banners. Finally, the Red Banner was run by Nurhaci's second son Daišan. Later in Nurhaci's reign, the Bordered Red Banner was handed down to his son. Daišan and his son would continue holding the two Red Banners well into the end of Hong Taiji's reign.

The details of Hong Taiji's succession as the Khan of the Later Jin dynasty are unclear.[33] When he died in late 1626, Nurhaci did not designate an heir; instead he encouraged his sons to rule collegially.[34] Three of his sons and a nephew were the "four senior beiles": Daišan (43 years old), Amin (son of Nurhaci's brother Šurhaci; 40 or 41), Manggūltai (38 or 39), and Hong Taiji himself (33).[35] On the day after Nurhaci's death, they coerced his primary consort Lady Abahai (1590–1626) – who had borne him three sons: Ajige, Dorgon, and Dodo – to commit suicide to accompany him in death.[36] This gesture has made some historians suspect that Nurhaci had in fact named the fifteen-year-old Dorgon as a successor, with Daišan as regent.[37] By forcing Dorgon's mother to kill herself, the princes removed a strong base of support for Dorgon. The reason such intrigue was necessary is that Nurhaci had left the two elite Yellow Banners to Dorgon and Dodo, who were the sons of Lady Abahai. Hong Taiji exchanged control of his two White Banners for that of the two Yellow Banners, shifting their influence and power from his young brothers onto himself.[بحاجة لمصدر]

According to Hong Taiji's later recollections, Amin and the other beile were willing to accept Hong Taiji as Khan, but Amin then would have wanted to leave with his Bordered Blue Banner, threatening to dissolve Nurhaci's unification of the Jurchens.[38] Eventually the older Daišan worked out a compromise that allowed Hong Taiji as the Khan, but almost equal to the other three senior beiles.[39] Hong Taiji would eventually find ways to become the undisputed leader.

The change of the name from Jurchen to Manchu by Hong Taiji was made to hide the fact that the ancestors of the Manchus, the Jianzhou Jurchens, were ruled by the Chinese.[40][41][42] The Qing dynasty carefully hid the two original editions of the books of "Qing Taizu Wu Huangdi Shilu" and the "Manzhou Shilu Tu" (Taizu Shihlu Tu) in the Qing palace, forbidden from public view because they showed that the Manchu Aisin Gioro family had been ruled by the Ming dynasty.[43][44] In the Ming period, the Koreans of Joseon referred to the Jurchen-inhabited lands north of the Korean peninsula, above the rivers Yalu and Tumen, as part of Ming China, which they called the "superior country" (sangguk).[45]

مراجع أولية

Information concerning Nurhaci can be found in later, propagandistic works such as the Manchu Veritable Records (Chinese: 滿洲實錄; pinyin: Mǎnzhōu Shílù; Manchu:ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᡳ

ᠶᠠᡵᡤᡳᠶᠠᠨ

ᡴᠣᠣᠯᡳ, Mölendroff: manju-i yargiyan kooli). Good contemporary sources are also available. For instance, much material concerning Nurhaci's rise is preserved within Korean sources such as the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty (Chinese: 朝鮮王朝實錄), especially the Seonjo Sillok and the Gwanghaegun Ilgi. Indeed, the record of Sin Chung-il's trip to Jianzhou is preserved in the Seonjo Sillok.

The Jiu Manzhou Dang from Nurhaci's reign also survives. A revised transcription of these records (with the dots and circles added to the script) was commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor. This has been translated into Japanese under the title Manbun roto, and Chinese, under the title Manwen Laodang (Chinese: 满文老檔). A project is currently under way at Harvard University to translate them into English, as The Old Manchu Chronicles.[46]

هيئته

According to the account of Korean ambassadors, Nurhaci was a physically strong man with a long and stern-looking face and that his nose was straight and big, and just like most of the other Manchu men, he shaved most of his facial hair and kept only his moustache.

عائلته

سلفه

- جده الأكبر

- Möngke Temür (1370–1433), personal name Mengtemu (孟特穆), posthumously honored as Emperor Yuan (原皇帝, Da Hūwangdi) with the temple name of Zhaozu (肇祖, Deribuhe Mafa)

- Great-Great-Grandmother or step-great-great-grandmother

- Mengtemu's wife, posthumously honored as Empress Yuan (原皇后 Da Hūwanghu)

- Great-Grandfather

- Fuman, posthumously honored as Emperor Zhi (直皇帝, Tondo Hūwangdi) with the temple name of Xingzu (興祖, Yendibuhe Mafa)

- Great-grandmother or step-great-grandmother

- Lady Hitara (喜塔拉氏), Fuman's wife, daughter of Captain Doulijin (都督 都理金), posthumously honored as Empress Zhi (直皇后)

- Grandfather

- Giocangga (died 1583), posthumously honored as Emperor Yi (翼皇帝, Gosingga Hūwangdi) with the temple name of Jingzu (景祖, Mukdembuhe Mafa)

- Grandmother or step-grandmother

- Giocangga's wife, posthumously honored as Empress Yi (翼皇后, Gosingga Hūwanghu)

- Father

- Taksi (died 1583), posthumously honored as Emperor Xuan (宣皇帝, Hafumbuha Hūwangdi) with the temple name of Xianzu (顯祖, Iletuleha Mafa)

- Mother

- Lady Hitara (喜塔拉氏) (died 1569), Taksi's wife, daughter of Captain Agu (都督 阿古), granddaughter of Captain Cancha (都督 參察), great-granddaughter of Captain Doulijin (都督 都里吉), posthumously honored as Empress Xuan (宣皇后, Hafumbuha Hūwanghu)

| سلف نورحاجي | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

أخوانه

- أشقاؤه (من نفس الأم)

- Šurhaci (舒爾哈齊) (1564–1611)

- Yarhaci (雅爾哈齊)

- شقيقته (من نفس الأم)

- Lady Aisin Gioro (愛新覺羅氏), married Gehashan Hasihu (噶哈善哈斯虎)

- غير أشقاء

- Bayara (巴雅齊)

- Murhaci (穆爾哈齊) (1582–1624)

زوجاته

تزوج نورحاجي 16 زوجة:

- Lady Tunggiya (佟佳氏), given name Hahana Jacing (哈哈納扎青), daughter of Tabonbayan (塔木巴晏). She married Nurhaci in 1577 as his first wife and initial consort. After the founding of the Qing Dynasty, she was posthumously honored as First Consort (元妃; Yuan Fei). Lady Tunggiya bore Nurhaci three children:

- Princess Dongguo

- Cuyen, Crown Prince

- Daišan, Prince Li

- Lady Fuca (富察氏), given name Gundai (袞代). She was Nurhaci's second consort. After the founding of the Qing Dynasty, she was posthumously honored as Successor Consort (繼妃; Ji Fei). Lady Fuca bore Nurhaci three children:

- Manggūltai

- Mangguji, Princess Hada

- Degelei, Beile

- Lady Yehenara (葉赫那拉氏) (given name Monggo Jer-Jer (孟古哲哲)) (1575–1603), daughter of Prince Yangginu of the Yehenara (葉赫部貝勒楊吉砮). She married Nurhaci in October 1588 at the age of 13. On 16 May 1636, she was posthumously honored as Empress Xiaocigao (孝慈高皇后). Lady Yehenara bore Nurhaci one child:

- Lady Ulanara (烏喇那拉氏) (given name Abahai (阿巴亥)) (1590–1626), daughter of Prince Mantai of the Ulanara (烏拉貝勒滿泰) (died 1596). She married Nurhaci in 1602 at the age of 12. In 1603 she was created Grand Consort (大妃). She was posthumously honored as Empress Xiaoliewu (孝烈武皇后). Lady Ulanara bore Nurhaci three children:

- Lady Borjigit (博爾濟吉特氏), posthumously honored as Dowager Consort Shou Kang (壽康太妃).

Four of Nurhaci's consorts held the rank of Side Chamber Consort (側妃; Ze Fei):

- Lady Irgen Gioro (伊爾根覺羅氏), bore Nurhaci two children:

- Princess Nunje

- Abatai

- Lady Yehenara (葉赫那拉氏), younger sister of Empress Xiaocigao. She bore Nurhaci one child:

- Nurhaci's eighth daughter

- two unnamed consorts

Five of Nurhaci's consorts held the rank of Ordinary Consort (庶妃; Shu Fei):

- Lady Joogiya (兆佳氏), bore Nurhaci one child:

- Abai, Duke of Zhen

- Lady Niuhuru (鈕祜祿氏), bore Nurhaci two children:

- Tangguldai, Duke of Fu

- Tabai, Duke of Fu

- Lady Giyamuhut Gioro (嘉穆瑚覺羅氏) (given name Zhen'ge (真哥)), bore Nurhaci five children:

- Babutai, Duke of Zhen

- Mukushen

- Babuhai

- Nurhaci's fifth daughter

- Nurhaci's sixth daughter

- Lady Silin Gioro (西林覺羅), bore Nurhaci one child:

- Lady Irgen Gioro (伊爾根覺羅氏), bore Nurhaci one child:

- Nurhaci's seventh daughter

أبناؤه

- ابنه الأكبر: كويين (褚英) (1580–1618)، كان في البداية ولي عهد نورحاجي، بعد وفاته كُرم كولي عهد گوانگ (廣略太子)

- الثاني: دايسان (代善) (19 أغسطس 1583 – 25 نوفمبر 1648)، كان أمير لي من الرتبة الأولى (禮親王)، مُنح لقب لي بعد وفاته (烈)

- الثالث: أباي (8 سبتمبر 1585 – 14 مارس 1648)، كان لقبه "الجنرال الذي يعمل على استقرار الدولة" (鎮國將軍)، بعد وفاته كُرم بقلب "الدوق الذي يعمل على استقرار الدولة" (鎮國公) ومُنح اسم بعد الوفاة تشينمين (勤敏)، كان لديه 7 أبناء

- الرابع: تانگولداي (湯古代) (24 ديسمبر 1585 – 3 نوفمبر 1640)، كان لقبه "الجنرال الذي يعمل على استقرار الدولة" (鎮國將軍)، كُرم بعد وفاته بلقب امبرطور شنزي "الدوق الذي يساعد الدولة" (輔國公) ومُنح اسم بعد الوفاة كجيه (克潔)، وأنجب ولدين

- الخامس: مانگولتاي (莽古爾泰) (1587 – 11 يناير 1633)

- السادس: تاباي (塔拜) (2 أبريل 1589 – 6 سبتمبر 1639)، حمل لقب "الجنرال الذي يساعد الدولة" (輔國將軍)، كُرم بعد وفاته بقلب "الدوق الذي يساعد الدولة" (輔國公)، ومُنح اسم بعد الوفاة تشيوهو (慤厚)، أنجب ثمانية أبناء

- السابع: أباتاي (阿巴泰) (27 يوليو 1589 – 10 مايو 1646)

- الثامن: هونگ تاتيجي (皇太極) (28 نوفمبر 1592 – 21 سبتمبر 1643), خلف نورحاجي كامبراطور لأسرة تشينگ

- التاسع: بابوتاي (巴布泰) (13 ديسمبر 1592 – 27 فبراير 1655)، كان لقبه "الدوق الذي يساعد الدولة" (鎮國公)، مُنح بعد وفاته اسم كتشي (恪僖)، أنجب ثلاثة أبناء

- العاشر: دگلي (德格類) (16 ديسمبر 1592 – 11 نوفمبر 1635)، كان ترتيبه في Beile، أنجب 3 أولاد

- الحادي عشر: بابوهاي (巴布海) (15 يناير 1597 – 1643)

- الثاني عشر: أجيگه (阿濟格) (28 أغسطس 1605 – 28 نوفمبر 1651)

- الثالث عشر: لايمبو (賴慕布) (26 يناير 1612 – 23 يونيو 1646)، كُرم بعد وفاته بقلب "الدوق الذي يساعد الدولة" (輔國公) ومُنح بعد وفاته اسم جيهژي (介直)

- الرابع عشر: دورگون (多爾袞) (17 نوفمبر 1612 – 31 ديسمبر 1650)، كان أمير روي من الرتبة الأولى (睿親王)، مُنح بعد وفاته اسم ژونگ (忠)، كُرم بعد وفاته كامبراطور لأسرة تشينگ وأطلق اسمه على معبد چنگژزونگ (成宗) بأمر من الامبراطور شونژي

- الخامس عشر: دودو (多鐸) (2 أبريل 1614 – 29 أبريل 1649)، كان أمير يو من الرتبة الأولى (豫親王) واسمه بعد وفاته تونگ (通)

- السادس عشر: فيانگو (費揚果) (نوفمبر 1620 – ؟)، لديه 4 أبناء

بناته

- ابنته الكبرى: الأميرة دونگو (東果格格) (1578 – أغسطس/أوائل سبتمبر 1652)، تزوج في 1588 من هوهوري (何和禮) (1561–1624)، كان ترتيبه أميرة الدولة (固倫公主)

- الثانية: الأميرة نونجه (嫩哲格格) (1587 – آخر أغسطس/أوائل سبتمبر 1646)، تزوجت من دارخان (達爾漢)، كان ترتيبها أميرة الرتبة الثانية (和碩公主)

- الثالثة: مانگوجي (莽古濟) (1590–1635)، تزوج أول مرة في 1601 من هادانارا ورگوداي (哈達部納喇.吳爾古代) (ابن منگبولو (孟格布祿)) وأنجبا بنتين، تزوجت ثانية في 1627 من بورجيگيت سونو مودولينگ (博爾濟吉特.瑣諾木杜凌)، حملت لقب أميرة هادا (哈達公主)

- الرابعة: موكوشن (穆庫什) (1595 – ?)؛ تزوجت في 1608 من الأمير بوجانتاي من اولانارا (烏拉國主布佔泰)، آخر أمراء اولا

- الخامسة: الأميرة؟ (1597–1613)؛ تزوجت في 1608 من نيوهورو داكي (鈕祜祿.達啟), son of Niohuru Eidu (鈕祜祿.額亦都)

- السادسة: الأميرة؟ (1600 – أكتوبر/أوائل نوفمبر 1646)، تزوجت في 1613 من يهنارا سونا (葉赫那拉.蘇納) (fof والدسوكساها)

- السابعة: الأميرة؟ (أبريل 1604 – أغسطس 1685)، تزوجت في نوفمبر أو أوائل ديسمبر 1619 من نارا إزهاي (納喇.鄂札伊) (توفت مايو/أوائل يونيو 1641)

- الخامسة: الأميرة؟ (1612 – مارس /أبريل 1646)، تزوجت في فبراير أو أوائل مارس 1625 من بورجيگيت گوربوشي (博爾濟吉特.固爾布什)، كان ترتيبها أميرة الرتبة الثانية (和碩公主)

في الثقافة العامة

في بداية فيلم عام 1984، إنديانا جونز ومعبد الموت، باع إنديانا جونز بقايا نوراجاي (الموجودة في جرة صغيرة منقوشة) في مقابل الماسة المملوكة للشقي الصيني لاو چه.

العلوم

جنس نوهاتيوس، جنس منقرض من الديناصور المجنح، سمي على سم نورحاجي.

انظر أيضاً

- ضريح فولينگ

- لي چنگليانگ - جنرال عسكري من أسرة مينگ مسؤول عن قباائل الجورچن

الهوامش

- ^ Narangoa 2014, p. 24.

- ^ Matsumura Jun, p.131 A Re-examinations of the Story of the Founding of the Ch'ing Dynasty 『清朝開国説話再考』(in Japanese)

- ^ Perdue, Peter C (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-674-04202-5.

- ^ The Cambridge History of China: Pt. 1 ; The Ch'ing Empire to 1800. Cambridge University Press. 2002. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6.

- ^ Sneath, David (2007). The Headless State: Aristocratic Orders, Kinship Society, and Misrepresentations of Nomadic Inner Asia (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0231511671.

- ^ Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1991). Orphan Warriors: Three Manchu Generations and the End of the Qing World (illustrated, reprint ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0691008779.

- ^ Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^ Gertraude Roth Li (2010). Manchu: A Textbook for Reading Documents. Natl Foreign Lg Resource Ctr. pp. 285–. ISBN 978-0-9800459-5-6.

- ^ Jonathan D. Spence; John E. Wills, Jr. (1 January 1979). From Ming to Ch'ing: Conquest, Region, and Continuity in Seventeenth-century China. Yale University Press. pp. 35–. ISBN 978-0-300-02672-6.

- ^ Mark C. Elliott (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Stanford University Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-0-8047-4684-7.

- ^ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~qing/WEB/NURHACI.html

- ^ Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^ Anne Walthall (2008). Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History. University of California Press. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-0-520-25444-2.

- ^ Frederic Wakeman (1 January 1977). Fall of Imperial China. Simon and Schuster. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-0-02-933680-9.

- ^ Kenneth M. Swope (23 January 2014). The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, 1618-44. Routledge. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-1-134-46209-4.

- ^ Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^ Mark C. Elliott (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Stanford University Press. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-0-8047-4684-7.

- ^ http://www.lishiquwen.com/news/7356.html

- ^ 曹德全 (2014-03-22). "首个投降后金的明将李永芳" [The first surrender of gold after the Ming Dynasty Li Yongfang] (in الصينية). Archived from the original on 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2016-06-30.

- ^ http://www.75800.com.cn/lx2/pAjRqK/9N6KahmKbgWLa1mRb1iyc_.html

- ^ https://read01.com/aP055D.html

- ^ Evelyn S. Rawski (15 November 1998). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions. University of California Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-520-92679-0.

- ^ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~qing/WEB/LI_SHIH-YAO.html

- ^ http://12103081.wenhua.danyy.com/library1210shtml30810106630060.html

- ^ Pamela Kyle Crossley (15 February 2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-0-520-92884-8.

- ^ Arthur W. Hummel, Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1943), p. 597

- ^ Early China. Society for the Study of Early China. 1975. p. 53.

- ^ Durrant, Stephen (1977). "Manchu Translations of Chou Dynasty Texts". Early China. 3: 53. doi:10.2307/23351361. JSTOR 23351361.

- ^ Chan, Sin-wai (2009). A Chronology of Translation in China and the West: From the Legendary Period to 2004. Chinese University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-962-996-355-2.

- ^ Perdue, Peter C (30 June 2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-674-04202-5.

- ^ Wakeman, Frederic (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^ Early China. Society for the Study of Early China. 1977. p. 53.

- ^ Roth Li 2002, p. 52.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 157.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 158.

- ^ Roth Li 2002, p. 51.

- ^ Roth Li 2002, p. 52, note 127, citing Fuchs 1935.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 158–60.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 160.

- ^ Hummel, Arthur W., ed. (2010). "Abahai". Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period, 1644-1912 (2 vols) (reprint ed.). Global Oriental. p. 2. ISBN 9004218017. Via Dartmouth.edu

- ^ Grossnick, Roy A. (1972). Early Manchu Recruitment of Chinese Scholar-officials. University of Wisconsin--Madison. p. 10.

- ^ Till, Barry (2004). The Manchu era (1644-1912): arts of China's last imperial dynasty. Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. p. 5.

- ^ Hummel, Arthur W., ed. (2010). "Nurhaci". Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period, 1644-1912 (2 vols) (reprint ed.). Global Oriental. p. 598. ISBN 9004218017. Via Dartmouth.edu

- ^ The Augustan, Volumes 17-20. Augustan Society. 1975. p. 34.

- ^ Kim, Sun Joo (2011). The Northern Region of Korea: History, Identity, and Culture. University of Washington Press. p. 19. ISBN 0295802170.

- ^ "Manchu Studies at Harvard". sites.fas.harvard.edu.

المراجع

- Fuchs, Walter (1935), "Der Tod der Kaiserin Abahai i. J. 1626. Ein Beitrag zur Frage des Opfertodes (殉死) bei den Mandju [The death of empress Abahai in 1626: a contribution to the question of sacrificial death among the Manchus]", Monumenta Serica 1 (1): 71–81.

- Roth Li, Gertraude (2002), "State Building before 1644", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 9–72, ISBN 0-521-24334-3.

- Wakeman, Frederic (1985), The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-04804-0, http://books.google.com/books?id=Hcv6AAAACAAJ. In two volumes.

نورحاجي وُلِد: 1558 توفي: 30 سبتمبر 1626

| ||

| ألقاب ملكية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه تاكسي |

زعيم جورچن جيانژو 1583–1616 |

تبعه هونگ تايجي |

| سبقه لا أحد (تأسيس الأسرة) |

خان جين 1616–1626 | |

- CS1 الصينية-language sources (zh)

- Articles containing simplified Chinese-language text

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2012

- Persondata templates without short description parameter

- مواليد 1559

- وفيات 1626

- مخترعو نظم كتابة

- أباطرة أسرة چينگ

- ملوك صينيون من القرن 17

- أشخاص من مودانجيانگ