ماگدبورگ

ماگدبورگ

Meideborg (Low German) | |

|---|---|

|

From top, left to right: Aerial view to a part of the city centre – Town Hall – "Green Citadel" – "Millennium Tower" – Magdeburg Cathedral at night – and panorama: city wall | |

| الإحداثيات: 52°07′54″N 11°38′21″E / 52.13167°N 11.63917°E | |

| البلد | ألمانيا |

| ولاية | ساكسونيا-أنهالت |

| المقاطعة | المقاطعة الحضرية |

| التقسيمات | 40 boroughs |

| الحكومة | |

| • العمدة (2022–29) | Simone Borris[de][1] (Ind.) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 201٫03 كم² (77٫62 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 43 m (141 ft) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| الرموز البريدية | 39104–39130 |

| مفاتيح الهاتف | 0391 |

| لوحة السيارة | MD |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | magdeburg.de |

ماگدبورگ (بالألمانية: Magdeburg) هي عاصمة الولاية الألمانية ساكسونيا أنهالت وأكبر مدنها. وتقع على نهر إلبه. وكانت واحدة من أهم المدن في العصور الوسطى في اوروبا. اوتو الأول أول إمبراطور روماني مقدس قضى معظم فترة حكمه في المدينة ودفن في كاتدرائيتها. قانون المدينة ويسمى حقوق ماگدبورگ انتشر كنموذج في وسط وشرق اوروبا. اشتهرت المدينة كذلك بحادثة اجتياح ماگدبورگ Sack of Magdeburg، الذي قوى المقاومة البروتستانتية أثناء حرب الثلاثين سنة.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdeburg, was buried in the city's cathedral after his death.[2] Magdeburg's version of German town law, known as Magdeburg rights, spread throughout Central and Eastern Europe. In the Late Middle Ages, Magdeburg was one of the largest and most prosperous German cities and a notable member of the Hanseatic League. One of the most notable people from the city was Otto von Guericke, famous for his experiments with the Magdeburg hemispheres.

Magdeburg has experienced three major devastations in its history. In 1207 the first catastrophe struck the city, with a fire burning down large parts of the city, including the Ottonian cathedral.[3] The Catholic League sacked Magdeburg in 1631,[2] resulting in the death of 25,000 non-combatants, the largest loss of the Thirty Years' War. During World War II the Allies bombed the city in 1945 and destroyed much of the city centre. Today, around 46% of the city consists of buildings from before 1950.[4]

After World War II, the city belonged to the German Democratic Republic from 1949 to 1990. Since then, many new construction projects have been implemented and old buildings have been restored.[5] Magdeburg celebrated its 1,200th anniversary in 2005.

Magdeburg is situated on Autobahn 2 and Autobahn 14, and hence is at the connection point of Eastern Europe (Berlin and beyond) with Western Europe, as well as the north and south of Germany. For the modern city, the most significant industries are: machine industry, healthcare industry, mechanical engineering, environmental technology, circular economy, logistics, culture industry, wood industry and information and communications technology.[6][7]

There are numerous cultural institutions in the city, including the Theater Magdeburg and the Museum of Cultural History. The city is also the location of two universities, the Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg and the Magdeburg-Stendal University of Applied Sciences.[8]

التاريخ

التاريخ المبكر

Founded by Charlemagne in 805 as Magadoburg (probably from Old High German magado for big, mighty and burg for fortress[9]), the town was fortified in 919 by King Henry the Fowler against the Magyars and Slavs. In 929 King Otto I granted the city to his English-born wife Edith as dower. Queen Edith loved the town and often resided there;[10] at her death she was buried in the crypt of the Benedictine abbey of Saint Maurice, later rebuilt as the cathedral. In 937, Magdeburg was the seat of a royal assembly. Otto I repeatedly visited Magdeburg, establishing a convent here about 937[2] and was later buried in the cathedral. He granted the abbey the right to income from various tithes and to corvée labour from the surrounding countryside.

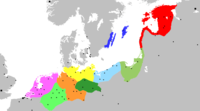

The Archbishopric of Magdeburg was founded in 968[2] at the synod of Ravenna; Adalbert of Magdeburg was consecrated as its first archbishop. The archbishopric under Adalbert included the bishoprics of Havelberg, Brandenburg, Merseburg, Meissen and Naumburg-Zeitz. The archbishops played a prominent role in the German colonisation of the Slavic lands east of the Elbe river.

In 1035 Magdeburg received a patent giving the city the right to hold trade exhibitions and conventions. This formed the basis of German town law to become known as the Magdeburg rights. These laws were adopted and modified throughout Central and Eastern Europe. Visitors from many countries began to trade with Magdeburg. The town was burnt down in 1188.[2]

In the 13th century, Magdeburg became a member of the Hanseatic League. With more than 20,000 inhabitants Magdeburg was one of the largest cities in the Holy Roman Empire. The town had active maritime commerce on the west (towards Flanders), with the countries of the North Sea, and maintained traffic and communication with the interior (for example Braunschweig).[10]

Reformation

The citizens constantly struggled against the archbishop, becoming nearly independent from him by the end of the 15th century. Around Easter 1497, the then twelve-year-old Martin Luther attended school in Magdeburg, where he was exposed to the teachings of the Brethren of the Common Life. In 1524, he was called to Magdeburg, where he preached and caused the city's defection from Roman Catholicism. The Protestant Reformation had quickly found adherents in the city, where Luther had been a schoolboy. Emperor Charles V repeatedly outlawed the unruly town, which had joined the League of Torgau and the Schmalkaldic League.[10]

As it had not accepted the Augsburg Interim decree (1548), the city, by the emperor's commands, was besieged (1550–1551) by Maurice, Elector of Saxony, but it retained its independence. The rule of the archbishop was replaced by that of various administrators belonging to Protestant dynasties. In the following years, Magdeburg gained a reputation as a stronghold of Protestantism and became the first major city to publish the writings of Martin Luther. In Magdeburg, Matthias Flacius and his companions wrote their anti-Catholic pamphlets and the Magdeburg Centuries, in which they argued that the Roman Catholic Church had become the kingdom of the Antichrist.[10]

In 1629 the city withstood its first siege during the Thirty Years' War, by Albrecht von Wallenstein, a Protestant convert to Catholicism. However, in 1631, imperial troops under Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, stormed the city and massacred the inhabitants, killing about 20,000 and burning the city.[11]

After the war, a population of only 4,000 remained. Under the Peace of Westphalia (1648), Magdeburg was to be assigned to Brandenburg-Prussia after the death of the administrator August of Saxe-Weissenfels, as the semi-autonomous Duchy of Magdeburg. This occurred in 1680.[12][13][14]

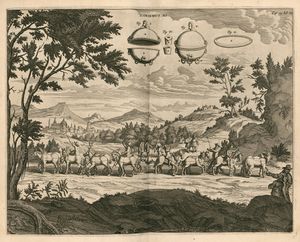

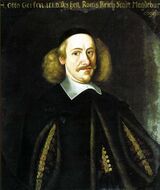

The city made an astonishingly quick recovery, due especially to the energy and dedication of its mayor Otto von Guericke, who was also a noted scientist. Just six years after the end of the terribly destructive war, Magdeburg was the scene of the famous scientific experiment known as The Magdeburg hemispheres by which the existence of vacuum - hitherto hotly debated - was empirically proven, with enormous implications for the later developments of physics.[15]

19th century

In the course of the Napoleonic Wars, the fortress surrendered to French troops in 1806. The city was annexed to the French-controlled Kingdom of Westphalia in the 1807 Treaty of Tilsit. King Jérôme appointed Count Heinrich von Blumenthal as mayor. In 1815, after the Napoleonic Wars, Magdeburg was made the capital of the new Prussian Province of Saxony.

20th century

In 1912, the old fortress was dismantled, and in 1908, the municipality Rothensee became part of Magdeburg.[16]

During World War I, Polish leader Józef Piłsudski and his close associate Kazimierz Sosnkowski were imprisoned in the city by Germany in 1917–1918.[17]

During the Weimar Republic the Magdeburger Tageszeitung was published as a local newspaper in Magdeburg.

During World War II, Magdeburg was the location of 30 forced labour detachments of the Stalag XI-A prisoner-of-war camp for some 4,500 Allied POWs,[18] a camp for Sinti and Romani people (see also Romani Holocaust),[19] and three subcamps of the Buchenwald concentration camp, in which mostly Jewish men and boys and Soviet, Polish and Jewish women were imprisoned.[20][21][22][23] In April 1945, dozens of prisoners were massacred by the Volkssturm and Hitler Youth, and surviving prisoners were sent on death marches towards the Ravensbrück and Sachsenhausen concentration camps.[20]

Magdeburg was heavily bombed by British and American air forces during the Second World War. The RAF bombing raid on the night of 16 January 1945 destroyed much of the city centre. The death toll is estimated at 2,000–2,500. Near the end of World War II, the city of about 340,000 became capital of the Province of Magdeburg. Brabag's Magdeburg/Rothensee plant that produced synthetic oil from lignite coal was a target of the Oil Campaign of World War II. The Gründerzeit suburbs north of the city, called the Nordfront, were destroyed as well as some of the city's main streets with its Baroque buildings.

It was occupied by 9th US Army troops on 18 April 1945 and was left to the Red Army on 1 July 1945. Post-war the area was part of the Soviet Zone of Occupation and many of the remaining pre-World War II city buildings were destroyed, with only a few buildings near the cathedral and in the southern part of the old city being restored to their pre-war state. Before the reunification of Germany, many surviving Gründerzeit buildings were left uninhabited and, after years of degradation, waiting for demolition. From 1949 until German reunification on 3 October 1990, Magdeburg belonged to the German Democratic Republic.

Magdeburg's centre has a number of Stalinist buildings from the 1950s.

Since German reunification

In 1990 Magdeburg became the capital of the new state of Saxony-Anhalt within reunified Germany. Huge parts of the city and its centre were also rebuilt in a modern style. Its economy is one of the fastest-growing in the former East German states.[24]

In 2005 Magdeburg celebrated its 1200th anniversary.

The city was hit by 2013 European floods. Authorities declared a state of emergency and said they expected the Elbe river to rise higher than in 2002. In Magdeburg, with water levels of خمسة متر (16 ft) above normal, about 23,000 residents had to leave their homes on 9 June.[25]

Intel will build its largest plant in Europe in the south of the city by 2027.[26]

Magdeburg is the capital and seat of the Landtag of Saxony-Anhalt.

Library of the Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg

The MDCC-Arena - a Soccer stadium, built in 2006

Restored building - Baroque architecture

الجغرافيا

Magdeburg is one of the major towns along the Elbe Cycle Route (Elberadweg). Its area is 201.03 km2 (77.62 sq mi).[27]

Districts

The city of Magdeburg is divided into 40 Stadtteile (districts).[28] Three of these, the former municipalities Beyendorf-Sohlen, Pechau and Randau-Calenberge, have a special status as Ortschaften.[29] The Stadtteile of Magdeburg are:[28]

|

|

|

Climate

Magdeburg has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb; Trewartha: Dobk) according to Köppen climate classification. The weather is damp and chilly in winters, with 71.7 days per year in which the minimum temperature is below the freezing point, and 15.6 days with maximum temperature below the 0 °C (32 °F) mark.[30] Magdeburg is warm and relatively wet in summer and can sometimes become hot. Annually, 48.9 days have maximum temperature above 25 °C (77 °F), of which 12 days have daily maximum above 30 °C (86 °F).[30]

On average, there are 20.9 days with thunder and 0.8 days with hail, annually. Thunder is more common in spring and summer than other times of the year, while hail exclusively occurs in spring and summer months.[30]

The Magdeburg weather station has recorded the following extreme values:[31]

- Its highest temperature was 38.2 °C (100.8 °F) on 20 July 2022.

- Its lowest temperature was −29.6 °C (−21.3 °F) on 27 January 1942.

- Its greatest annual precipitation was 831.5 mm (32.74 in) in 1926.

- Its least annual precipitation was 299.8 mm (11.80 in) in 1911.

- The longest annual sunshine was 2,168.1 hours in 2018.

- The shortest annual sunshine was 1,393.0 hours in 1984.

| بيانات المناخ لـ Magdeburg (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1881–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °س (°ف) | 16.5 (61.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

25.1 (77.2) |

31.9 (89.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

38.2 (100.8) |

37.9 (100.2) |

35.0 (95.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

18.1 (64.6) |

38.2 (100.8) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 4.0 (39.2) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | 1.4 (34.5) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.0 (66.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | −1.4 (29.5) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

| متوسط الدنيا °س (°ف) | −10.8 (12.6) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

2.2 (36.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

9.0 (48.2) |

8.1 (46.6) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | −29.6 (−21.3) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

−17.6 (0.3) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

0.5 (32.9) |

5.2 (41.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−21.9 (−7.4) |

−22.6 (−8.7) |

−25.4 (−13.7) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 38.3 (1.51) |

26.1 (1.03) |

34.9 (1.37) |

27.8 (1.09) |

56.1 (2.21) |

51.8 (2.04) |

60.9 (2.40) |

59.4 (2.34) |

43.3 (1.70) |

40.0 (1.57) |

36.8 (1.45) |

39.5 (1.56) |

515.8 (20.31) |

| متوسط عمق الثلج الكثيف cm (inches) | 6.2 (2.4) |

4.4 (1.7) |

2.6 (1.0) |

0.3 (0.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.9 (0.4) |

5.1 (2.0) |

9.7 (3.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 15.9 | 13.9 | 14.7 | 11.4 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 13.8 | 13.0 | 11.9 | 14.2 | 15.3 | 16.7 | 165.4 |

| متوسط الرطوبة النسبية (%) | 84.7 | 80.6 | 75.9 | 68.1 | 68.3 | 69.1 | 68.3 | 68.5 | 75.1 | 81.8 | 86.4 | 85.9 | 76.1 |

| Mean monthly ساعات سطوع الشمس | 59.7 | 80.8 | 126.9 | 189.5 | 228.8 | 235.4 | 230.6 | 215.7 | 162.7 | 116.0 | 59.7 | 49.1 | 1٬754٫8 |

| Source 1: NCEI[30] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst / SKlima.de[31] | |||||||||||||

Population

| السنة | تعداد | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1400 | 30٬000 | — |

| 1620 | 25٬000 | −16.7% |

| 1825 | 36٬647 | +46.6% |

| 1855 | 61٬500 | +67.8% |

| 1871 | 84٬401 | +37.2% |

| 1885 | 114٬291 | +35.4% |

| 1890 | 202٬234 | +76.9% |

| 1900 | 229٬667 | +13.6% |

| 1910 | 279٬629 | +21.8% |

| 1919 | 285٬856 | +2.2% |

| 1925 | 293٬959 | +2.8% |

| 1933 | 306٬894 | +4.4% |

| 1939 | 336٬838 | +9.8% |

| 1940 | 346٬600 | +2.9% |

| 1945 | 225٬030 | −35.1% |

| 1950 | 260٬305 | +15.7% |

| 1956 | 259٬320 | −0.4% |

| 1961 | 262٬437 | +1.2% |

| 1966 | 267٬817 | +2.1% |

| 1971 | 271٬906 | +1.5% |

| 1976 | 279٬430 | +2.8% |

| 1981 | 287٬362 | +2.8% |

| 1986 | 288٬975 | +0.6% |

| 1990 | 280٬536 | −2.9% |

| 2001 | 229٬755 | −18.1% |

| 2011 | 228٬144 | −0.7% |

| 2022 | 241٬517 | +5.9% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. Source:[32][مرجع دائرة مفرغة][33] | ||

As of 2021, Magdeburg has a population of about 237,000. Its population grew rapidly after the end of 19th century due to industrialization. In 1885, the population was 100,000, and doubled after only five years. Magdeburg reached its greatest population in 1940, at approximately 346,000. At that time the city was poised to become a giant metropolis, but the events of WWII changed its future. After the war, in the East Germany era, Magdeburg recovered its industrial base to a degree, particularly the Machine industry, and became one of the important cities of East Germany. In 1991, when Magdeburg became the capital of the state of Saxony-Anhalt, its population was about 275,000. After the German Reunification, the population of Magdeburg declined due to some loss of industries, when many residents moved to former West Germany. Since 2011, the population has stabilized at around 240,000.

| Rank | Nationality | Population (2022) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5,341 | |

| 2 | 4,893 | |

| 3 | 2,379 | |

| 4 | 1,431 | |

| 5 | 1,348 | |

| 6 | 1,253 | |

| 7 | 1,013 | |

| 8 | 947 | |

| 9 | 833 | |

| 10 | 674 |

Politics

Mayor and city council

The current mayor of Magdeburg is independent politician Simone Borris since 2022. The most recent mayoral election was held on 24 April 2022, with a runoff held on 8 May, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Simone Borris | Independent (FDP, future!, MUT) | 33,065 | 44.3 | 39,201 | 64.8 | |

| Jens Rösler | SPD/Greens | 20,080 | 26.3 | 21,298 | 35.2 | |

| Tobias Krull | Christian Democratic Union | 9,327 | 12.2 | |||

| Nicole Anger | The Left | 5,230 | 6.8 | |||

| Frank Pasemann | Alternative for Germany | 3,802 | 5.0 | |||

| Till Isenhuth | Independent | 1,676 | 2.2 | |||

| Sarah Biedermann | Free Voters | 1,289 | 1.7 | |||

| Bettina Fassl | Animal Protection Alliance | 1,103 | 1.4 | |||

| André Jordan | Die PARTEI | 860 | 1.1 | |||

| Valid votes | 76,432 | 99.6 | 60,508 | 99.4 | ||

| Invalid votes | 302 | 0.4 | 340 | 0.6 | ||

| Total | 76,734 | 100.0 | 60,848 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 189,916 | 40.4 | 189,471 | 32.1 | ||

| Source: City of Magdeburg | ||||||

The most recent city council election was held on 9 June 2024, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 75,972 | 23.8 | ▲ 5.2 | 13 | ▲ 3 | |

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 72,626 | 22.8 | ▲ 8.4 | 13 | ▲ 5 | |

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 47,852 | 15.0 | 8 | |||

| The Left (Die Linke) | 32,549 | 10.2 | 6 | |||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 30,119 | 9.4 | 5 | |||

| Magdeburg Garden Party (Gartenpartei) | 14,711 | 4.6 | ▲ 0.4 | 3 | ▲ 1 | |

| Animal Protection Party (Tierschutzpartei) | 14,328 | 4.5 | ▲ 1.2 | 3 | ▲ 1 | |

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 13,141 | 4.1 | 2 | |||

| future! | 6,984 | 2.2 | 1 | |||

| Animal Protection Alliance (Tierschutzallianz) | 5,495 | 1.7 | ▲ 0.4 | 1 | ||

| Volt Germany (Volt) | 3,343 | 1.0 | New | 1 | New | |

| Pößel (Independent) | 809 | 0.3 | New | 0 | New | |

| Valid votes | 319,022 | 100.0 | ||||

| Invalid balots | 1,620 | 1.5 | ||||

| Total ballots | 109,729 | 100.0 | 56 | ±0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 187,588 | 58.5 | ▲ 5.1 | |||

| Source: City of Magdeburg | ||||||

Education

The Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg (German: Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg) was founded in 1993 and is one of the newest universities in Germany. The university in Magdeburg has about 13,000 students in nine faculties. There are 11,700 papers published in international journals from this institute.

The Magdeburg-Stendal University of Applied Sciences was founded in 1991. There are 30 direct study programs in five departments in Magdeburg and two departments in Stendal. The university has more than 130 professors and approximately 4,500 students at Magdeburg and 1,900 at Stendal.

Conservatory – "Georg-Philipp-Telemann"

Culture and architecture

Entertainment

Magdeburg has a municipal theatre, Theater Magdeburg.

Magdeburg is well known for its Christmas market, which is an attraction for 1.5 million visitors every year. Other events are the Stadtfest, Christopher Street Day, Elbe in Flames, and the Europafest Magdeburg.[34][35] The autumn fair (formerly men's fair) of Magdeburg goes back to Germany's oldest folk festival. The tradition dates back to September 1010, when the holy feast of the Theban Legion was celebrated in Magdeburg (then called Magathaburg).[36]

Event venues

- Altes Theater am Jerichower Platz – Former theater, used for parties and large conferences

- AMO – Culture and congress building

- Buttergasse - Night club near the city centre at "Alter Markt" – house-, electro, pop and black music

- Concert hall Georg Philipp Telemann at "Kloster unser lieben Frauen"

- Factory – Former factory building, German and international pop, rock, metal, and indie music artists are featured

- Festung Mark – Part of the former city fortification, now reconstructed for parties and conventions

- Feuerwache – Former fire station, repurposed for events

- GETEC Arena – Biggest multi-purpose hall in Saxony-Anhalt, home of handball team SC Magdeburg

- halber85 - Conventions, partys, conferences

- Kunstkantine – Factory cafeteria, monthly electro-music parties

- MDCC-Arena – Home of 1. FC Magdeburg

- Messe Magdeburg - Official trade fair site

- Prinzzclub – Night club at Halberstädter Straße – house-, electro, and black music

- Seebühne at Elbauenpark

- Stadthalle – Concert hall

- Studentenclub Baracke - Night club especially for students - house-, electro, rock, pop, indie and black music

- Tessenow Loft - Conventions, partys, conferences

Museums

- Magdeburg Museum of Cultural History

- Otto-von-Guericke-Museum Lukasklause

- Jahrtausendturm

- Magdeburg Museum of Nature

- Magdeburg Museum of Technology

- Art Museum in the Monastery of Our Lady

- Magdeburg Circus Museum

- Magdeburg Hairdressing Museum

- Steamboat Württemberg - a museum ship

Architecture

Cathedral

One of Magdeburg's most impressive buildings is the Lutheran Cathedral of Saints Catherine and Maurice with a height of 104 m (341.21 ft), making it the tallest church building of eastern Germany. It is notable for its beautiful and unique sculptures, especially the "Twelve Virgins" at the Northern Gate, the depictions of Otto I the Great and his wife Editha as well as the statues of St Maurice and St Catherine. The predecessor of the cathedral was a church built in 937 within an abbey, called St. Maurice. Emperor Otto I the Great was buried here beside his wife in 973. St. Maurice burnt to ashes in 1207. The exact location of that church remained unknown for a long time. The foundations were rediscovered in May 2003, revealing a building 80 m (262.47 ft) long and 41 m (134.51 ft) wide.

The construction of the new church lasted 300 years. The cathedral of Saints Catherine and Maurice was the first Gothic church building in Germany. The building of the steeples was completed as late as 1520.

While the cathedral was virtually the only building to survive the massacres of the Thirty Years' War, it suffered damage in World War II. It was soon rebuilt and completed in 1955.

The square in front of the cathedral (also called the Neuer Markt, or "new marketplace") was occupied by an imperial palace (Kaiserpfalz), which was destroyed in the fire of 1207. The stones from the ruin were used for the building of the cathedral. The presumed remains of the palace were excavated in the 1960s.

Other sights

- Unser Lieben Frauen Monastery (Our Lady), 11th century, containing the church of St. Mary. Today a museum for Modern Art. Home of the National Collection of Small Art Statues of the GDR (Nationale Sammlung Kleinkunstplastiken der DDR).

- The Magdeburger Reiter ("Magdeburg Rider", 1240), the first free-standing equestrian sculpture north of the Alps. It probably depicts the Emperor Otto I.

- City hall (1698). This building had stood on the market place since the 13th century, but it was destroyed in the Thirty Years' War; the new city hall was built in a Renaissance style influenced by Dutch architecture. It was renovated and re-opened in Oct 2005.

- Landtag; the seat of the government of Saxony-Anhalt with its Baroque façade built-in 1724.

- Monuments depicting Otto von Guericke (1907), Eike von Repkow and Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben.

- Ruins of the greatest fortress of the former Kingdom of Prussia.

- Rotehorn-Park

- Elbauenpark containing the highest wooden structure in Germany.

- St. Sebastian's Cathedral, the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Magdeburg.

- St. John Church (Johanniskirche)

- The Gruson-Gewächshäuser, a botanical garden within a greenhouse complex

- The Magdeburg Water Bridge, Europe's longest water bridge

- "Die Grüne Zitadelle" or The Green Citadel of Magdeburg, a large, pink building of a modern architectural style designed by Friedensreich Hundertwasser and completed in 2005.

- Jerusalem Bridge

- Zoo Magdeburg

- St. Johannis Church

- St. Petri Church, with stained glass by Charles Crodel

المعالم الرئيسية

المدن التوأم والمدن الشقيقة

ماجدبورج متوأمة مع:

|

انظر أيضاً

- ذئب ماگدبورگ

- Urstromtaler - community currency for the area

Sports

Magdeburg has a proud history of sports teams. 1. FC Magdeburg currently plays in the 2. Bundesliga, the second division of German football. They are the only East German football club to have won the UEFA Cup Winners' Cup. The now-defunct clubs SV Victoria 96 Magdeburg and Cricket Viktoria Magdeburg were among the first football clubs in Germany.

There is also the very successful handball team, SC Magdeburg. They won multiple times the Handball-Bundesliga (HBL), DHB-Pokal, DHB-Supercup, EHF European League, EHF Champions League, EHF Men's Champions Trophy and the IHF Men's Super Globe.

The discus was re-discovered in Magdeburg in the 1870s by Christian Georg Kohlrausch, a gymnastics teacher.

Twin towns – sister cities

Magdeburg is twinned with:[39]

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina (1977)

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina (1977) Braunschweig, Germany (1987)

Braunschweig, Germany (1987) Nashville, United States (2003)

Nashville, United States (2003) Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine (2008)

Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine (2008) Radom, Poland (2008)

Radom, Poland (2008) Harbin, China (2008)

Harbin, China (2008) Le Havre, France (2011)

Le Havre, France (2011) Kiryat Motzkin, Israel (2024)

Kiryat Motzkin, Israel (2024)

People

A–K

- Ernst Anders (1845–1911), portrait and genre painter

- Richard Assmann (1845–1918), meteorologist

- Theodor Avé-Lallemant (1806–1890), music critic and writer on music

- Alfons Bach, (1904–1999), industrial designer[40]

- Kurt Behrens (1884–1928), springboard diver

- Arno Bieberstein (1884–1918), swimmer

- Jessica Böhrs (born 1980), actress and singer

- Henry Busse (1894–1955), trumpeter and bandleader, emigrated to the US at 18

- Adelbert Delbrück (1822–1890), banker and lawyer

- Margarethe Düren (1904-1988), German operatic soprano

- Friedrich Ernst Fesca (1789–1826), violinist and composer

- Hans Gericke (1912–2014), architect

- Frank Giering (1971–2010), actor

- Harry Giese (1903–1991), actor and spokesman in Nazi newsreels

- Georg Gradnauer (1866–1946), newspaper editor and politician

- Alfred Grünberg (1901–1942), worker, KPD member and resistance fighter against Nazism

- Otto von Guericke (1602–1686), mayor and inventor of the Magdeburg hemispheres. The Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg is named after him

- Carl Gustav Friedrich Hasselbach (1809–1882), mayor and member of the Prussian House of Lords; a square in the centre of Magdeburg is named after him

- Ulrike Helzel, soprano

- Gottlieb von Haeseler (1701–1752), entrepreneur in the Duchy of Magdeburg

- Ingolf Huhn (born 1955), theatre and opera manager

- Hartmann Wilhem Otto (1876–1960), immigrated to the US, where he changed his name to William Hartman and served as a Rough Rider in the Spanish–American War together with Theodore Roosevelt

- Christian Georg Kohlrausch (1851–1934), gymnastics teacher and re-discoverer of discus throwing

- Anna-Maria Henckel von Donnersmarck (born 1940), political activist

- Carl Hindenburg (1820–1899), cycling official and first president of the German Cyclist Federation (DRB)

- Heinrich Jost (1889–1948), typeface designer

- Eberhard Jüngel (1934–2021), German Lutheran theologian

- Georg Kaiser (1878–1945), writer

- Nadine Kleinert (born 1975), retired shot putter, Olympic and World Championship silver medallist

- Wilhelm Kobelt (1865–1927), member of the Reichstag and local politician in Magdeburg

- Rolf Kohnert (born 1938), engineer, 3 times Australian masters cycling champion

- Stefan Kretzschmar (born 1973), handball player and Olympic medallist

- Hans Kühne (1880–1969), chemist on the board of I.G. Farben and defendant during the Nuremberg trials

L–Z

- Ernst Lehmann (1908–1945), SPD politician, active in the resistance against Nazism

- Otto Lehmann (1900–1936), resistance fighter against Nazism

- Werner Marcks (1896–1967), lieutenant general in World War II

- Olaf Malolepski (born 1946), singer-songwriter

- Johann Carl Simon Morgenstern (1770–1852), philologist who coined the term Bildungsroman

- Felix von Niemeyer (1820–1871), physician, royal Württemberg personal physician

- Leo Nowak (born 1929), Roman Catholic bishop of Magdeburg (1990–2004)

- Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard (born 1942), biologist, the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research in 1991 and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1995

- Oleh Kuznetsov (born 1963), Ukrainian football coach and former professional player

- Richard Ölze (1900–1980), painter

- Erich Ollenhauer (1901–1963), leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany 1952–1963

- Menahem Pressler (1923–2023), pianist

- Ernst Reuter (1889–1953), Mayor of Magdeburg 1931–1933, then Mayor of West Berlin in 1948–1953

- Willy Rosen (1894–1944) composer and songwriter

- Arthur Ruppin (1876–1943), Zionist thinker and leader

- Gustav Schäfer (1988-), drummer and musician for Tokio Hotel

- Ekkehard Schall (1930–2005), actor and theatre director

- Marcel Schmelzer (born 1988), footballer

- Karl Schmidt (1902–1945), resistance fighter against Nazism

- Petra Schmidt-Schaller (born 1980), actress

- Manfred Schoof (born 1936), jazz trumpeter

- Wolfgang Schreyer (1927–2017), writer

- Margarete Schön (1895–1985), stage and film actress

- Ivan Shyshkin (born 1983), Ukrainian footballer

- Kurt Singer (1886–1962), philosopher

- Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben (1730–1794), American patriot

- Christoph Christian Sturm (1740–1786), preacher and author, wrote the majority of his devotional works here

- Bruno Taut (1880–1938), city architect 1921–1923, completed two housing projects in Magdeburg

- Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), composer

- Klaus Thunemann (born 1937), bassoon professor

- Henning von Tresckow (1901–1944), major general in the Wehrmacht, active in the military resistance

- Lothar von Trotha (1848–1920), military commander notorious for presiding over the near-extermination of the Herero in German South-West Africa

- Karl Wallenda (1905–1978), highwire acrobat

- Camillo Walzel (1829–1895), librettist and theatre director

- Wilhelm Weitling (1808–1871), utopian Communist

- Dieter Zahn (born 1940), double-bassist

- Dejan Zavec (born 1976), Slovenian welterweight boxer, IBF Welterweight Champion

- Heinrich Zschokke (1771–1848), author and reformer

- George William Ziemann (1809–1881), Christian missionary who served in Magdeburg in the infantry

معرض صور

Magdeburg Hauptbahnhof (Central Station)

View over Elbauenpark with Jahrtausendturm

Elbe river in Magdeburg

انظر أيضاً

- The Magdeburg hemispheres, an experimental apparatus used to demonstrate the force of atmospheric pressure in 1656 by scientist Otto von Guericke

- Timeline of Magdeburg

المراجع

- ^ Mayoral election results, 2022, accessed 4 October 2022. (in ألمانية)

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEB1911 - ^ "Brandkatastrophen und deren Bedeutung für die Verbreitung gotischer Sakralarchitektur" (PDF). archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de (in الألمانية). Jens Kremb. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ https://zensus2011.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Publikationen/Aufsaetze_Archiv/2015_12_NI_GWZ_endgueltig.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4[وصلة عارية]

- ^ "Bilanz zum Stadtumbau". magdeburg.de (in الألمانية). Magdeburg. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ "Key industries". www.magdeburg.de. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ^ "The paper industry in Saxony-Anhalt". www.saxony-anhalt.com. Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ^ "Hochschule Magdeburg-Stendal". hs-magdeburg.de.

- ^ "Magdeburg: Jungfrau oder Groß? Der Ortsname erklärt" (in الألمانية). Onomastik.com. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت ث

One or more of the preceding sentences تضم نصاً من مطبوعة هي الآن مشاع: Löffler, Klemens (1910). . In هربرمان, تشارلز (ed.). الموسوعة الكاثوليكية. Vol. 9. Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences تضم نصاً من مطبوعة هي الآن مشاع: Löffler, Klemens (1910). . In هربرمان, تشارلز (ed.). الموسوعة الكاثوليكية. Vol. 9. Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=,|coauthors=, and|month=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Religijski rat – "Ubili smo Boga u Magdeburgu!"" (in صربية-كرواتية). Večernji list. 28 January 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Heinrich Rathmann (1806). Geschichte der Stadt Magdeburg von ihrer ersten Entstehung an bis auf gegenwärtige Zeiten. Bey dem Buchhändler Johann Adam Creutz.

- ^ Nathan Rein (5 December 2016). The Chancery of God: Protestant Print, Polemic and Propaganda against the Empire, Magdeburg 1546–1551. Taylor & Francis. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-1-351-89314-5.

- ^ Daniel Gehrt; Johannes Hund; Stefan Michel (28 January 2019). Bekennen und Bekenntnis im Kontext der Wittenberger Reformation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-3-647-57095-2.

- ^

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 12 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 670.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 12 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 670. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "City & History - Navigation md.de". www.magdeburg.de. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- ^ Waldemar Kowalski. "Józef Piłsudski w Magdeburgu, czyli więzień stanu nr 1". Dzieje.pl (in البولندية). Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ^ "Lager für Sinti und Roma Magdeburg". Bundesarchiv.de (in الألمانية). Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ أ ب "Magdeburg (Polte, Frauen)". aussenlager-buchenwald.de (in الألمانية). Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ "Magdeburg (Polte, Männer)". aussenlager-buchenwald.de (in الألمانية). Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ "Magdeburg-Rothensee". aussenlager-buchenwald.de (in الألمانية). Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2009). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume I. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 388–390. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- ^ "Zur Situation der Städte". Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Thousands evacuated as Elbe bursts dam in German floods 10 June 2013

- ^ "Intel Germany Mega Site Gets €6.8bn in European Chips Act Funding". 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Tabellen Bodenfläche". Statistisches Landesamt Sachsen-Anhalt. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ أ ب Bevölkerung & Demografie 2021, Magdeburger Statistik.

- ^ Lesefassung der Hauptsatzung der Landeshauptstadt Magdeburg Archived 4 أكتوبر 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 9 November 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 12 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ أ ب "Monatsauswertung". sklima.de (in الألمانية). SKlima. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Link

- ^ "Germany: States and Major Cities".

- ^ "Magdeburg-Tourist - PFD" (PDF). www.magdeburg-tourist.de. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- ^ "Christopher Street Day - Magdeburg". csdmagdeburg.de. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- ^ Ottopix (2 October 2018). "The oldest folk festival in Germany". Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Fraternity cities on Sarajevo Official Web Site". © City of Sarajevo 2001-2008. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ "Radom Official Website - Partner Cities". ملف:Uk flag.gif

(في الإنگليزية والپولندية) © 2007 Urząd Miasta Radom. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

(في الإنگليزية والپولندية) © 2007 Urząd Miasta Radom. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ^ "Partnerstädte". magdeburg.de (in الألمانية). Magdeburg. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Pace, Eric (23 August 1999). "Alfons Bach, 95, Designer of Tubular Furniture". Arts. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

وصلات خارجية

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with ألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- All articles with bare URLs for citations

- Articles with bare URLs for citations from August 2024

- Articles incorporating text from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia with Wikisource reference

- CS1 صربية-كرواتية-language sources (sh)

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- CS1 البولندية-language sources (pl)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing Low German-language text

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Germany articles requiring maintenance

- المدن in Saxony-Anhalt

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- All articles lacking reliable references

- Articles lacking reliable references from August 2019

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with empty portal template

- German state capitals

- مارتن لوثر

- Members of the Hanseatic League

- Populated riverside places in Germany

- Populated places on the Elbe

- Urban districts of Saxony-Anhalt

- ماگدبورگ

- عواصم الولايات الألمانية

- أعضاء الرابطة الهانزية

- مدن في ساكسونيا-أنهالت

- مدن ألمانيا

- مقاطعة ساكسونيا

- بلدات جامعية في ألمانيا

- صفحات مع الخرائط