تالين

Tallinn | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Tallinn Old Town; the Town Hall's; skyline of downtown Tallinn; Song Festival Grounds; St. Nicholas Church; the medieval defensive walls; Kumu Art Museum; and Residence of the President in Kadriorg | |

|

| |

| الإحداثيات: 59°26′14″N 24°44′43″E / 59.43722°N 24.74528°E | |

| Country | |

| County | Harju |

| First confirmed written record | 1219 |

| First possible appearance on map | 1154 |

| City rights | 1248 |

| الحكومة | |

| • Mayor | Mihhail Kõlvart |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 159٫2 كم² (61٫5 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 9 m (30 ft) |

| التعداد (2023)[1] | |

| • الإجمالي | 453٬864 |

| • الترتيب | 1st in Estonia |

| • الكثافة | 2٬900/km2 (7٬400/sq mi) |

| صفة المواطن | Tallinner (English) tallinlane (Estonian) |

| Resident registration (January 2023) | |

| • Total | 458,398 |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | EE-784 |

| Gross regional product[3] | 2021 |

| - Total | €16.166 billion |

| - Per capita | €37,034 |

| City budget | €1.140 billion[4] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | tallinn |

تالين (Tallinn ؛ /ˈtælɪn,_ˈtɑːlɪn/)[أ][5][6] هي عاصمة إستونيا وأكبر مدنها. وتطل على خليج في شمال إستونيا، على شاطئ خليج فنلندا في بحر البلطيق. ويبلغ عدد سكان تالين 454,000 نسمة (في 2023)[1] وتقع إدارياً في مقاطعة هاريو. تالين هي المركز المالي والصناعي والثقافي لإستونيا. وتقع على بعد 187 كم شمال غرب ثاني أكبر مدن البلد، تارتو، إلى أنها تقع على بعد 80 كم فقط جنوب هلسنكي، فنلندا، وأيضاً على بعد 320 كم غرب سانت پطرسبورگ، روسيا، وعلى بعد 300 كم شمال ريگا، لاتڤيا، وعلى بعد 380 كم شرق ستوكهولم، السويد. ومنذ القرن 13 حتى النصف الأول من القرن العشرين، كانت تالين تـُعرف في معظم دول العالم بتنويعات من اسمها التاريخ الآخر ريڤال Reval.[7]

Tallinn received Lübeck city rights in 1248,[8] however the earliest evidence of human population in the area dates back nearly 5,000 years.[9] The medieval indigenous population of what is now Tallinn and northern Estonia was one of the last "pagan" civilisations in Europe to adopt Christianity following the Papal-sanctioned Livonian Crusade in the 13th century.[10][7] The first recorded claim over the place was laid by Denmark after a successful raid in 1219 led by King Valdemar II, followed by a period of alternating Scandinavian and Teutonic rulers. Due to the strategic location by the sea, its medieval port became a significant trade hub, especially in the 14–16th centuries, when Tallinn grew in importance as the northernmost member city of the Hanseatic League.[7] Tallinn Old Town is one of the best-preserved medieval cities in Europe and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[11]

Tallinn has the highest number of startup companies per person among all capitals and larger cities in Europe[12] and is the birthplace of many international high-technology companies, including Skype, Wise and Bolt.[13][7] The city is home to the headquarters of the European Union's IT agency,[14] and to the NATO Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence. In 2007, Tallinn was listed among the top-10 digital cities in the world,[15] and in 2022, Tallinn was listed among the top-10 "medium-sized European cities of the future".[16]

Etymology

In 1154, a town called قلون (Qlwn[17] or Quwri[18][19]) was recorded in the description of the world upon the world map (Tabula Rogeriana) commissioned by the Norman King Roger II of Sicily and compiled by Arab cartographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, who described it as "a small town like a large castle" among the towns of 'Astlanda'. It has been suggested that one possible transcription, 'Qlwn', may have denoted a predecessor of the modern city[20][21] and may somehow be related to a toponym Kolyvan, which has been discovered from later East Slavic chronicles.[22][23] However, a number of modern historians have considered connecting any of al-Idrisi's placenames with modern Tallinn erroneous, unfounded, or speculative.[24][8][25][26]

Henry of Livonia, in his chronicle (ح. 1229), called the town with the name that is also known to have been used up to the 13th century by Scandinavians: Lindanisa (or Lyndanisse in Danish,[27][28][29] Lindanäs in Swedish and Ledenets in Old East Slavic).

The Icelandic Njal's saga—composed after 1270, but describing events between 960 and 1020—mentions an event that occurred somewhere in the area of Tallinn and calls the place Rafala (probably a derivation of Rävala, Revala, or some other variant of the Estonian name of the adjacent medieval Estonian county). Soon after the Danish conquest in 1219, the town became known in the Scandinavian and German languages as Reval (لاتينية: Revalia). Reval was in official use in Estonia until 1918.

The name Tallinn(a) is Estonian. It has been widely considered a historical derivation of Taani-linna, meaning "Danish-castle" (لاتينية: Castrum Danorum), conceivably because the Danish invaders built the castle in place of the Estonian stronghold after the 1219 battle of Lyndanisse.[ب] The Finnic element -linna, like Germanic -burg and Slavic -grad /-gorod, originally meant "fortress", but has been used as a suffix in the formation of town names.

In international use, the English and German-language Reval as well as the Russian analog Revel (Ревель) were all gradually replaced by the Estonian name after the country became independent in 1918. At first, both Estonian forms, Tallinna and Tallinn, were used.[30] Tallinna in Estonian denotes also the genitive case of the name, as in Tallinna Sadam ('the Port of Tallinn').

التاريخ

The first archaeological traces of a small hunter-fisherman community's presence[9] in what is now Tallinn's city centre are about 5,000 years old. The comb ceramic pottery found on the site dates to about 3000 BCE and corded ware pottery around 2500 BCE.[31]

Around 1050 AD, a fortress was built in what is now central Tallinn, on the hill of Toompea.[18]

As an important port on a major trade route between Novgorod and western Europe, it became a target for the expansion of the Teutonic Knights and the Kingdom of Denmark during the period of Northern Crusades in the beginning of the 13th century when Christianity was forcibly imposed on the local population. Danish rule of Tallinn and northern Estonia started in 1219.

In 1285, Tallinn, then known more widely as Reval, became the northernmost member of the Hanseatic League – a mercantile and military alliance of German-dominated cities in Northern Europe. The king of Denmark sold Reval along with other land possessions in northern Estonia to the Teutonic Knights in 1346. Reval was arguably the most significant medieval port in the Gulf of Finland, the second-most important port being Turku.[32] Reval enjoyed a strategic position at the crossroads of trade between the rest of western Europe and Novgorod and Muscovy in the east. The city, with a population of about 8,000, was very well fortified with city walls and 66 defence towers.

A weather vane, the figure of an old warrior called Old Thomas, was put on top of the spire of the Tallinn Town Hall in 1530. Old Thomas later became a popular symbol of the city.

In the early years of the Protestant Reformation, the city converted to Lutheranism. In 1561, Reval (Tallinn) became a dominion of Sweden.

During the 1700–1721 Great Northern War, plague-stricken Tallinn along with Swedish Estonia and Livonia capitulated to Tsardom of Russia (Muscovy) in 1710, but the local self-government institutions (Magistracy of Reval and Estonian Knighthood) retained their cultural and economical autonomy within Imperial Russia as the Governorate of Estonia. The Magistracy of Reval was abolished in 1889. The 19th century brought industrialisation of the city and the port kept its importance.

On 24 February 1918, the Estonian Declaration of Independence was proclaimed in Tallinn. It was followed by Imperial German occupation until the end of World War I in November 1918, after which Tallinn became the capital of independent Estonia. During World War II, Estonia was first occupied by the Soviet army and annexed into the USSR in the summer of 1940, then occupied by Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1944. During the German occupation Tallinn suffered from many instances of aerial bombing by the Soviet air force. During the most destructive Soviet bombing raid on 9–10 March 1944, over a thousand incendiary bombs were dropped on the town, causing widespread fires, killing 757 people, and leaving over 20,000 residents of Tallinn without shelter. After the German retreat in September 1944, the city was occupied again by the Soviet Union.

During the 1980 Summer Olympics, the sailing (then known as yachting) events were held at Pirita, north-east of central Tallinn. Many buildings, such as the Tallinn TV Tower, "Olümpia" hotel, the new Main Post Office building, and the Regatta Centre, were built for the Olympics.

In 1991, the independent democratic Estonian nation was restored and a period of quick development as a modern European capital ensued. Tallinn became the capital of a de facto independent country once again on 20 August 1991. The Old Town became a World Heritage Site in 1997,[33] and the city hosted the 2002 Eurovision Song Contest.[34] Tallinn was the 2011 European Capital of Culture, and is the recipient of the 2023 European Green Capital Award.[35] The city has pledged to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030 and takes pride in its biodiversity and high air quality.[36][37] But critics say that the award was received on false promises since it won the title with its "15-minute city" concept, according to which key facilities and services should be accessible within a 15-minute walk or bike ride but the concept was left out of the green capital program and other parts of the 12 million euro program amount to a collection of temporary and one-off projects without any structural and lasting changes.[38]

الجغرافيا

Tallinn is situated on the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland, in north-western Estonia.

The largest lake in Tallinn is Lake Ülemiste (9.44 km2 (3.6 sq mi)), which serves as the main source of the city's drinking water. Lake Harku is the second-largest lake within the borders of Tallinn and its area is 1.6 km2 (0.6 sq mi). The only significant river in Tallinn nowadays is the Pirita River, in the eponymous Pirita city district. Historically, a smaller river, called Härjapea, flowed from Lake Ülemiste through the town into the sea, but the river was diverted into underground sewerage system in the 1930s and has since completely disappeared from the cityscape. References to it still remain in the street names Jõe (from jõgi, river) and Kivisilla (from kivi sild, stone bridge).

A limestone cliff runs through the city. It can be seen at Toompea, Lasnamäe, and Astangu. However, Toompea is not a part of the cliff, but a separate hill.

The highest point in Tallinn, at 64 m (about 200 ft) above sea level, is situated in Hiiu, Nõmme District, in the south-west of the city.

The length of the coast is 46 km (29 mi). It comprises three bigger peninsulas: Kopli, Paljassaare, and Kakumäe Peninsulas. The city has a number of public beaches, including those at Pirita, Stroomi, Kakumäe, Harku, and Pikakari.[39]

The geology under the city of Tallinn is made up of rocks and sediments of different composition and age. Youngest are the Quaternary deposits. The materials of these deposits are till, varved clay, sand, gravel, and pebbles that are of glacial, marine and lacustrine origin. Some of the Quaternary deposits are valuable as they constitute aquifers, or as in the case of gravels and sands, are used as construction materials. The Quaternary deposits are the fill of valleys that are now buried. The buried valleys of Tallinn are carved into older rock likely by ancient rivers to be later modified by glaciers. While the valley fill is made up of Quaternary sediments the valleys themselves originated from erosion that took place before the Quaternary.[40] The substrate into which the buried valleys were carved is made up of hard sedimentary rock of Ediacaran, Cambrian and Ordovician age. Only the upper layer of Ordovician rocks protrudes from the cover of younger deposits, cropping out in the Baltic Klint at the coast and at a few places inland. The Ordovician rocks are made up from top to bottom of a thick layer of limestone and marlstone, then a first layer of argillite followed by first layer of sandstone and siltstone and then another layer of argillite also followed by sandstone and siltstone. In other places of the city, hard sedimentary rock is only to be found beneath Quaternary sediments at depths reaching as much as 120 m below sea level. Underlying the sedimentary rock are the rocks of the Fennoscandian Craton including gneisses and other metamorphic rocks with volcanic rock protoliths and rapakivi granites. These rocks are much older than the rest (Paleoproterozoic age) and do not crop out anywhere in Estonia.[40]

المناخ

Tallinn has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb) with mild, rainy summers and cold, snowy winters.[41] Winters are cold, but mild for its latitude, owing to its coastal location. The average temperature in February, the coldest month, is −3.6 °C (25.5 °F). During the winters, temperatures tend to hover close to freezing, but mild spells of weather can push temperatures above 0 °C (32 °F), occasionally reaching above 5 °C (41 °F) while cold air masses can push temperatures below −18 °C (0 °F) an average of 6 days a year. Snowfall is common during the winters, which are cloudy[42][مطلوب مصدر أفضل] and characterised by low amounts of sunshine, ranging from only 20.7 hours of sunshine per month in December to 58.8 hours in February.[43]

Spring starts out cool, with freezing temperatures common in March and April, but gradually becomes warmer in May, when daytime temperatures average 15.4 °C (59.7 °F), although nighttime temperatures still remain cool, averaging −3.7 to 5.2 °C (25.3 to 41.4 °F) from March to May.[44] Snowfall is common in March and can occur in April.[42]

تتمتع تالين بمناخ بحري تتراوح درجات حرارته ابتداء من مايو وحتى سبتمبر بين 50 و80 درجة على مقياس فهرنهايت وفي الصيف تبقى درجات الحرارة حول 65 درجة على المقياس نفسه ويستمر فصل الصيف في يونيو وحتى أغسطس.

| متوسطات الطقس لتالين | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| شهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | اكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | السنة |

| العظمى القياسية °C (°F) | 9.2 (49) | 10.2 (50) | 15.9 (61) | 27.2 (81) | 29.7 (85) | 31.2 (88) | 32.3 (90) | 31.2 (88) | 28.5 (83) | 21.8 (71) | 13.4 (56) | 10.7 (51) | 32٫3 (90) |

| متوسط العظمى °م (°ف) | -2.9 (27) | -3.0 (27) | 0.8 (33) | 7.3 (45) | 14.0 (57) | 18.8 (66) | 20.8 (69) | 19.9 (68) | 14.9 (59) | 9.0 (48) | 3.3 (38) | -0.2 (32) | 8٫6 (47) |

| متوسط الصغرى °م (°ف) | -8.2 (17) | -8.7 (16) | -5.6 (22) | -0.2 (32) | 4.9 (41) | 9.9 (50) | 12.5 (55) | 12.0 (54) | 8.0 (46) | 3.7 (39) | -0.9 (30) | -4.9 (23) | 1٫9 (35) |

| الصغرى القياسية °م (°F) | -31.4 (-25) | -31.0 (-24) | -26.2 (-15) | -17.2 (1) | -4.3 (24) | 0.0 (32) | 4.4 (40) | 1.7 (35) | -4.7 (24) | -10.5 (13) | -21.3 (-6) | -32.2 (-26) | −32٫2 (−26) |

| هطول الأمطار mm (بوصة) | 45 (1.8) | 29 (1.1) | 29 (1.1) | 36 (1.4) | 37 (1.5) | 53 (2.1) | 79 (3.1) | 84 (3.3) | 82 (3.2) | 70 (2.8) | 68 (2.7) | 55 (2.2) | 667 (26٫3) |

| المصدر: Pogoda.ru.net[42] 7.09.2007 | |||||||||||||

Administrative districts

| District | Flag | Arms | Population (2022)[45] |

Area | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haabersti | 47٬980 | 22.26 km2 (8.6 sq mi) | 2,157.2/km² (5,587.1/sq mi) | ||

| Kesklinn (centre) | 65٬041 | 30.56 km2 (11.8 sq mi) | 2,128.3/km² (5,512.4/sq mi) | ||

| Kristiine | 32٬725 | 7.84 km2 (3.0 sq mi) | 4,175.4/km² (10,814.4/sq mi) | ||

| Lasnamäe | 117٬230 | 27.47 km2 (10.6 sq mi) | 4,269.0/km² (11,056.6/sq mi) | ||

| Mustamäe | 65٬978 | 8.09 km2 (3.1 sq mi) | 8,156.1/km² (21,124.3/sq mi) | ||

| Nõmme | 37٬402 | 29.17 km2 (11.3 sq mi) | 1,282.1/km² (3,320.6/sq mi) | ||

| Pirita | 19٬034 | 18.73 km2 (7.2 sq mi) | 1,016.1/km² (2,631.7/sq mi) | ||

| Põhja-Tallinn | 59٬612 | 15.9 km2 (6.1 sq mi) | 3,751.6/km² (9,717.6/sq mi) |

Tallinn is subdivided into eight administrative linnaosa (districts). Each district has a linnaosa valitsus (district government) which is managed by a linnaosavanem (district elder) who is appointed by the city government. The function of the "district governments" however is not directly governing, but just limited to providing advice to the city government and the city council on issues related to the administration of respective districts.

The districts are administratively further divided into 84 asum (subdistricts or "neighbourhoods" with officially defined borders).[46]

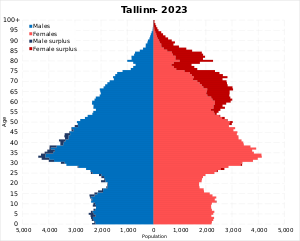

السكان

Tallinn is the most populous, primate, and capital city of Estonia.

| Largest ethnic groups[47] | ||

| Ethnic group | Population (2022) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Estonians | 233,518 | 53.34 |

| Russians | 149,878 | 34.23 |

| Ukrainians | 15,449 | 3.53 |

| Belarusians | 6,153 | 1.40 |

| Finns | 3,431 | 0.78 |

| Jews | 1,405 | 0.32 |

| Latvians | 1,343 | 0.34 |

| Germans | 1,219 | 0.28 |

| Lithuanians | 1,092 | 0.25 |

| Armenians | 1,043 | 0.24 |

| Tatars | 1,033 | 0.24 |

| Azerbaijanis | 1,029 | 0.23 |

| Poles | 940 | 0.21 |

| Other | 15,960 | 3.64 |

| Unknown | 4,318 | 0.99 |

The population of Tallinn on 1 January 2021 was 438,341.[1] It is the most populous and primate city of Estonia, and the 59th most populated city in the EU.

According to Eurostat, in 2004, Tallinn had one of the largest number of non-EU nationals of all EU member states' capital cities. Ethnic Russians are a significant minority in Tallinn, as around a third of the city's residents are first and second generation immigrants from Russia and other parts of the former Soviet Union; a majority of the Soviet-era immigrants now hold Estonian citizenship.[48]

Ethnic Estonians made up over 80% of Tallinn's population before World War II. As of 2022, ethnic Estonians made up over 53% of the population. Tallinn was one of the urban areas with industrial and military significance in northern Estonia that during the period of Soviet occupation underwent extensive russification of its ethnic composition due to large influx of immigrants from Russia and other parts of the former USSR. Whole new city districts were built where the main intent of the then Soviet authorities was to accommodate Russian-speaking immigrants: Mustamäe, Väike-Õismäe, Pelguranna, and most notably, Lasnamäe, which in 1980s became, and is to this day, the most populous district of Tallinn.

The official language of Tallinn is Estonian. As of 2011, 50.1% of the city's residents were native speakers of Estonian, whereas 46.7% had Russian as their first language. While English is the most frequently used foreign language by the residents of Tallinn, there are also a significant number of native speakers of Ukrainian and Finnish.[49]

| Ethnicity | 1922[50] | 1934[51] | 1941[52] | 1959[53] | 1970[53] | 1979[53] | 1989[53] | 2000[54] | 2011[55] | 2021[56] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Estonians | 102,568 | 83.9 | 117,918 | 85.6 | 132,396 | 94.0 | 169,697 | 60.2 | 201,908 | 55.7 | 222,218 | 51.9 | 227,245 | 47.4 | 215,114 | 53.7 | 217,601 | 55.3 | 233,520 | 53.3 |

| Russians | 7,513 | 6.14 | 7,888 | 5.72 | 5,689 | 4.04 | 90,594 | 32.2 | 127,103 | 35.0 | 162,714 | 38.0 | 197,187 | 41.2 | 146,208 | 36.5 | 144,721 | 36.8 | 149,883 | 34.2 |

| Ukrainians | – | – | 35 | 0.03 | – | – | 7,277 | 2.58 | 13,309 | 3.67 | 17,507 | 4.09 | 22,856 | 4.77 | 14,699 | 3.67 | 11,565 | 2.94 | 15,450 | 3.53 |

| Belarusians | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3,683 | 1.31 | 7,158 | 1.97 | 10,261 | 2.39 | 12,515 | 2.61 | 7,938 | 1.98 | 6,229 | 1.58 | 6,154 | 1.41 |

| Finns | – | – | 304 | 0.22 | 214 | 0.15 | 1,650 | 0.59 | 2,852 | 0.79 | 2,996 | 0.70 | 3,271 | 0.68 | 2,436 | 0.61 | 2,062 | 0.52 | 3431 | 0.78 |

| Jews | 1,929 | 1.58 | 2,203 | 1.60 | 0 | 0.00 | 3,714 | 1.32 | 3,750 | 1.03 | 3,737 | 0.87 | 3,620 | 0.76 | 1,598 | 0.40 | 1,460 | 0.37 | 1,405 | 0.32 |

| Latvians | – | – | 572 | 0.42 | 340 | 0.24 | 702 | 0.25 | 1,007 | 0.28 | 1,259 | 0.29 | 1,032 | 0.22 | 827 | 0.21 | 628 | 0.16 | 1,500 | 0.34 |

| Germans | 6,904 | 5.65 | 6,575 | 4.77 | – | – | 125 | 0.04 | 217 | 0.06 | 332 | 0.08 | 516 | 0.11 | 516 | 0.13 | 492 | 0.13 | 1,219 | 0.28 |

| Tatars | – | – | 75 | 0.05 | – | – | 745 | 0.26 | 1,055 | 0.29 | 1,500 | 0.35 | 1,975 | 0.41 | 1,265 | 0.32 | 1,012 | 0.26 | 1,033 | 0.24 |

| Poles | – | – | 599 | 0.43 | 502 | 0.36 | 759 | 0.27 | 967 | 0.27 | 1,084 | 0.25 | 1,240 | 0.26 | 936 | 0.23 | 768 | 0.20 | 940 | 0.21 |

| Lithuanians | – | – | 92 | 0.07 | 97 | 0.07 | 594 | 0.21 | 852 | 0.23 | 905 | 0.21 | 1,052 | 0.22 | 949 | 0.24 | 795 | 0.20 | 1,092 | 0.25 |

| Unknown/Not stated | 0 | 0.00 | 368 | 0.27 | 150 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 7 | 0.00 | 3,694 | 0.92 | 709 | 0.18 | 4,317 | 0.99 |

| Other | 3,354 | 2.74 | 1163 | 0.84 | 1,523 | 1.08 | 2,174 | 0.77 | 2,528 | 0.70 | 4,023 | 0.94 | 6,458 | 1.35 | 4,198 | 1.05 | 5,180 | 1.32 | 17,873 | 4.08 |

| Total | 122,268 | 100 | 137,792 | 100 | 140,911 | 100 | 281,714 | 100 | 362,706 | 100 | 428,537 | 100 | 478,974 | 100 | 400,378 | 100 | 393,222 | 100 | 437,817 | 100 |

| Year | 1372 | 1772 | 1816 | 1834 | 1851 | 1881 | 1897 | 1925 | 1959 | 1989 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 3,250 | 6,954 | 12,000 | 15,300 | 24,000 | 45,900 | 58,800 | 119,800 | 283,071 | 478,974 | 400,378 | 401,694 | 406,703 | 426,538 | 430,805 | 434,562 | 437,619 | 438,341 | 437,811 |

Religion

Religion in Talinn (2021) [1]

الاقتصاد

Tallinn has a highly diversified economy with particular strengths in information technology, tourism and logistics. More than half of Estonia's GDP is created in Tallinn.[57] In 2008, the GDP per capita of Tallinn stood at 172% of the Estonian average.[58] In addition to longtime functions as seaport and capital city, Tallinn has seen development of an information technology sector; in its 13 December 2005, edition, The New York Times characterised Estonia as "a sort of Silicon Valley on the Baltic Sea".[59] One of Tallinn's sister cities is the Silicon Valley town of Los Gatos, California. Skype is one of the best-known of several Estonian start-ups originating from Tallinn. Many start-ups have originated from the Institute of Cybernetics. In recent years,[when?] Tallinn has gradually been becoming one of the main IT centres of Europe, with the Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCD COE) of NATO, eu-LISA, the EU Digital Agency and the IT development centres of large corporations, such as TeliaSonera and Kuehne + Nagel being based in the city. Smaller start-up incubators like Garage48 and Game Founders have helped to provide support to teams from Estonia and around the world looking for support, development and networking opportunities.[60]

Tallinn receives 4.3 million visitors annually,[61] a figure that has grown steadily over the past decade. The Finns are especially a common sight in Tallinn;[62] on average, about 20,000–40,000 Finnish tourists visit the city between June and October.[63] Most of the visitors come from Europe, though Tallinn has also become increasingly visited by tourists from the Asia-Pacific region.[64] Tallinn Passenger Port is one of the busiest cruise destinations on the Baltic Sea, it served more than 520,000 cruise passengers in 2013.[65]

Eesti Energia, the national energy company,[66]; Elering, the national electric power transmission system operator; Eesti Gaas, the national natural gas distribution company; Alexela Group, the country's largest private energy company, all have their headquarters in Tallinn.

Tallinn is the financial centre of Estonia and also a strong economic centre in the Scandinavian-Baltic region. Many major banks, such as SEB, Swedbank, and Nordea, have their local offices in Tallinn. LHV Pank, an Estonian investment bank, has its corporate headquarters in Tallinn. Tallinn Stock Exchange, part of NASDAQ OMX Group, is the only regulated exchange in Estonia.

Port of Tallinn is one of the biggest ports in the Baltic sea region, whereas the largest cargo port of Estonia, the Port of Muuga, which is operated by the same business entity, is located in the neighboring town of Maardu.[67] Old City Harbour has been known as a convenient harbour since the medieval times, but nowadays the cargo operations are shifted to Muuga Cargo Port and Paldiski South Harbour. As of 2010, there was still a small fleet of oceangoing trawlers that operated out of Tallinn.[68] Tallinn's industries include shipbuilding, machine building, metal processing, electronics, textile manufacturing. BLRT Grupp has its headquarters and some subsidiaries in Tallinn. Air Maintenance Estonia and AS Panaviatic Maintenance, both based in Tallinn Airport, provide MRO services for aircraft, largely expanding their operations in recent years. Liviko, the maker of the internationally-known Vana Tallinn liqueur, is similarly based in Tallinn. The headquarters of Kalev, a confectionery company and part of the industrial conglomerate Orkla Group, is located in Lehmja, near the city's southeastern boundary. Estonia is ranked third in Europe in terms of shopping centre space per inhabitant, ahead of Sweden and being surpassed only by Norway and Luxembourg.[69]

Notable headquarters

Among others:

- NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE)

- eu-LISA, the European Agency for the operational management of large-scale IT systems in the area of freedom, security and justice[70][71][14]

- Skype software development centre[72]

- Telia Company IT development centre[73]

- Kuehne + Nagel IT centre[74]

- Arvato Financial Solutions global IT development and innovation centre[75]

- Ericsson has one of its biggest production facilities in Europe located in Tallinn, focusing on the production of 4G communication devices.[76]

- Equinor has announced that the group's financial centre will be relocated to Tallinn.[77]

- Bolt

- Alexela

- LHV

التعليم

تتأثر الثقافة الاستونية بشكل كبير بالثقافة الفنلندية خاصة والاسكندنافية بشكل عام، وجامعة تارتو هي أكبر جامعة باستونيا، كما تُعد جامعة تالين التقنية من أهم الجامعات.

Institutions of higher education and science include:

- Baltic Film and Media School

- Estonian Academy of Arts

- Estonian Academy of Security Sciences

- Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre

- Estonian Business School

- Estonian Maritime Academy

- Institute of Theology of the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church

- National Institute of Chemical Physics and Biophysics

- Tallinn University

- Tallinn University of Technology

- Tallinn University of Applied Sciences

Culture

Tallinn was a European Capital of Culture for 2011, along with Turku, Finland.

Museums

Tallinn is home to more than 60 museums and galleries.[78] Most of them are located in Kesklinn, the central district of the city, and cover Tallinn's rich history.

One of the most visited historical museums in Tallinn is the Estonian History Museum, located in Great Guild Hall at Vanalinn, the old part of the city.[79] It covers Estonia's history from prehistoric times up until the end of the 20th century.[80] It features film and hands-on displays that show how Estonian dwellers lived and survived.[80]

The Estonian Maritime Museum provides an overview of nation's seafaring past. The museum is located in the Old Town, inside one of Tallinn's former defensive structures – Fat Margaret's Tower.[81] Another historical museum that can be found at city's Old Town, just behind the Town Hall, is Tallinn City Museum. It covers Tallinn's history from pre-history until 1991, when Estonia regained its independence.[82] Tallinn City Museum owns nine more departments and museums around the city,[82] one of which is Tallinn's Museum of Photography, also located just behind the Town Hall. It features permanent exhibition that covers 100 years of photography in Estonia.[83]

Estonia's Vabamu Museum of Occupations and Freedom is located in Kesklinn (the Central district). It covers the 51 years (1940–1991) when Estonia was occupied by the former Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.[84] Not far away is another museum related to the Soviet occupation of Estonia, the KGB Museum, which occupies the 23rd floor of Sokos Hotel Viru. It features equipment, uniforms, and documents of Russian Secret Service agents.[85]

The city is also home to Estonian Museum of Natural History and the Museum of Health Care, both located in Old Town. The Museum of Natural History features several themed exhibitions that provide an overview of the wildlife of Estonia and the world.[86] The Museum of Health Care has exhibitions covering human anatomy, health care, and the history of medicine in Estonia on display.[87]

Tallinn is home to several art and design museums. The Estonian Art Museum, the largest art museum in Estonia, consists of four branches – Kumu Art Museum, Kadriorg Art Museum, Mikkel Museum, and Niguliste Museum. Kumu Art Museum features the country's largest collection of contemporary and modern art. It also displays Estonian art starting from the early 18th century.[88] Those who are interested in Western European and Russian art may enjoy Kadriorg Art Museum collections, located in Kadriorg Palace, a beautiful Baroque building erected by Peter the Great. It stores and displays about 9,000 works of art from the 16th to 20th centuries.[89] The Mikkel Museum, in Kadriorg Park, displays a collection of mainly Western art – ceramics and Chinese porcelain donated by Johannes Mikkel in 1994. The Niguliste Museum occupies former St. Nicholas' Church; it displays collections of historical ecclesiastical art spanning nearly seven centuries from the Middle Ages to post-Reformation art.

Those that are interested in design and applied art may enjoy the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design collection of Estonian contemporary designs. It displays up to 15.000 pieces of work made of textile art, ceramics, porcelain, leather, glass, jewellery, metalwork, furniture, and product design.[90] To experience more relaxed, culture-oriented exhibits, one may turn to Museum of Estonian Drinking Culture. This museum showcases the historic Luscher & Matiesen Distillery as well as the history of Estonian alcohol production.[91]

Lauluväljak

The Estonian Song Festival (in Estonian: Laulupidu) is one of the largest choral events in the world[التحقق مطلوب], listed by the UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. It is held every five years in July on the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds (Lauluväljak) simultaneously with the Estonian Dance Festival.[92] The joint choir has comprised more than 30,000 singers performing to an audience of 80,000.[92][93]

Estonians have one of the biggest collections of folk songs in the world[التحقق مطلوب], with written records of about 133,000 folk songs.[94] From 1987, a cycle of mass demonstrations featuring spontaneous singing of national songs and hymns that were strictly forbidden during the years of the Soviet occupation to peacefully resist the oppression. In September 1988, a record 300,000 people, more than a quarter of all Estonians, gathered in Tallinn for a song festival.[95]

Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival

Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival (Estonian: Pimedate Ööde Filmifestival, or PÖFF), is an annual film festival held since 1997 in Tallinn, the capital city of Estonia. PÖFF is the only festival in the Nordic and Baltic region with a FIAPF (International Federation of Film Producers Association) accreditation for holding an international competition programme in the Nordic and Baltic region with 14 other non-specialised festivals, such as Cannes, Berlin, Venice. With over 250 feature films screened each year and over 77500 attendances (2014), PÖFF is one of the largest film events of Northern Europe and cultural events in Estonia in the winter season. During its 19th edition in 2015 the festival screened more than 600 films (including 250+ feature-length films from 80 countries), bringing over 900 screenings to an audience of over 80, 000 people as well as over 700 accredited guests and journalists from 50 countries. In 2010 the festival held the European Film Awards ceremony in Tallinn.

Cuisine

The traditional cuisine of Tallinn reflects culinary traditions of north Estonia, the role of the city as a fishing port, and historical German influences. Numerous cafés have played a major role in a social life of the city since the 19th century, as have bars, especially in the Kesklinn district.

The martsipan industry in Tallinn has a very long history. The production of martsipan started in the Middle Ages, almost simultaneously in Tallinn (Reval) and Lübeck, both member cities of the Hanseatic League. In 1695, marzipan was mentioned as a medicine, under the designation of Panis Martius, in the price lists of the Tallinn Town Hall Pharmacy.[97] The modern era of martsipan in Tallinn began in 1806, when the Swiss confectioner Lorenz Caviezel set up his confectionery on Pikk Street. In 1864, it was bought and expanded by Georg Stude and now is known as the Maiasmokk café. In the late 19th century martsipan figurines made by Tallinn's confectioners were supplied to the Russian imperial family.[98]

Arguably, the most symbolic seafood dish of Tallinn is vürtsikilu ("spicy sprat") – salted sprats pickled with a distinctive set of spices including black pepper, allspice and cloves. The making of traditional vürtsikilu is thought to have originated from the city's outskirts. In 1826, the merchants of Tallinn exported 40,000 cans of vürtsikilu to Saint Petersburg.[99] A closely associated dish is kiluvõileib ("sprat-butter-bread") – a traditional rye bread open sandwich covered with a layer of butter and vürtsikilu as the topping. Boiled egg slices and culinary herbs are optional extra toppings. Alcoholic beverages produced in the city include beer, vodka, and liqueurs (such as the eponymous Vana Tallinn). The number of craft beer breweries has expanded sharply in Tallinn over the last decade, entering local and regional markets.

السياحة

What can arguably be considered to be Tallinn's main attractions are located in the Tallinn Old Town (divided into a "lower town" and Toompea hill) which is easily explored on foot. The eastern parts of the city, notably Pirita (with Pirita Convent) and Kadriorg (with Kadriorg Palace) districts, are also popular destinations, and the Estonian Open Air Museum in Rocca al Mare, west of the city, preserves aspects of Estonian rural culture and architecture. The historical wooden suburbs like Kalamaja, Pelgulinn, Kassisaba and Kelmiküla and revitalized industrial areas like Rotermanni Quarter, Noblessner and Dvigatel are also unique places to visit.

Toompea – Upper Town

This area was once an almost separate town, heavily fortified, and has always been the seat of whatever power that has ruled Estonia. The hill occupies an easily defensible site overlooking the surrounding districts. The major attractions are the medieval Toompea Castle (today housing the Estonian Parliament, the Riigikogu), the Lutheran St Mary's Cathedral, also known as the Dome Church (الإستونية: [Toomkirik] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), and the Russian Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Cathedral.

All-linn – Lower Town

This area is one of the best preserved medieval towns in Europe and the authorities are continuing its rehabilitation. Major sights include the Town Hall square (الإستونية: [Raekoja plats ] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), the city wall and towers (notably "Fat Margaret" and "Kiek in de Kök") as well as a number of medieval churches, including St Olaf's, St. Nicholas' and the Church of the Holy Ghost. The Catholic Cathedral of St Peter and St Paul is also in the Lower Town.

Kadriorg

Kadriorg is 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) east of the city centre and is served by buses and trams. Kadriorg Palace, the former palace of Peter the Great, built just after the Great Northern War, now houses the foreign art department of the Art Museum of Estonia, the presidential residence and the surrounding grounds include formal gardens and woodland.

The main building of the Art Museum of Estonia, Kumu (الإستونية: [Kunstimuuseum] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Art Museum), was built in 2006 and lies in Kadriorg park. It houses an encyclopaedic collection of Estonian art, including paintings by Carl Timoleon von Neff, Johann Köler, Eduard Ole, Jaan Koort, Konrad Mägi, Eduard Wiiralt, Henn Roode and Adamson-Eric, among others.

Pirita

This coastal district is a further 2 kilometres north-east of Kadriorg. The marina was built for the Moscow Olympics of 1980, and boats can be hired on the Pirita River. Two kilometres inland are the Botanic Gardens and the Tallinn TV Tower.

Transport

City transport

The city operates a system of bus (73 lines), tram (4 lines) and trolley-bus (4 lines) routes to all districts; the 33 kilometres (21 mi) long tram system[100] is the only tram network in Estonia.[101][102] A flat-fare system is used. The ticket-system is based on prepaid RFID cards available in kiosks and post offices. In January 2013, Tallinn became the first European capital to offer a fare-free service on buses, trams and trolleybuses within the city limits. This service is available to residents who register with the municipality.[103]

Air

The Lennart Meri Tallinn Airport is about 4 kilometres (2 miles) from Town Hall square (Raekoja plats). There is a tram (Line Number: 4) and local bus connection between the airport and the edge of the city centre (bus no. 2). The nearest railway station Ülemiste is only 1.5 km (0.9 mi) from the airport. The construction of the new section of the airport began in 2007 and was finished in summer 2008.

Ferry

Several ferry operators, Viking Line, Tallink and Eckerö Line, connect Tallinn to Helsinki, Mariehamn, Stockholm, and St. Petersburg. Passenger lines connect Tallinn to Helsinki (83 km (52 mi) north of Tallinn) in approximately 2–3.5 hours by cruiseferries, with up to eight daily crossings all year round.

Railroad

The Elron railway company operates train services from Tallinn to Tartu, Valga, Türi, Viljandi, Tapa, Narva, Koidula. Buses are also available to all these and various other destinations in Estonia, as well as to Saint Petersburg in Russia and Riga, Latvia. The Russian railways company operates a daily international sleeper train service between Tallinn – Moscow.

Tallinn also has a commuter rail service running from Tallinn's main rail station in two main directions: east (Aegviidu) and to several western destinations (Pääsküla, Keila, Riisipere, Turba, Paldiski, and Kloogaranna). These are electrified lines and are used by the Elron railroad company. Stadler FLIRT EMU and DMU units are in service since July 2013. The first electrified train service in Tallinn was opened in 1924 from Tallinn to Pääsküla, a distance of 11.2 km (7.0 mi).

The Rail Baltica project, which will link Tallinn with Warsaw via Latvia and Lithuania, will connect Tallinn with the rest of the European rail network. An undersea tunnel has been proposed between Tallinn and Helsinki,[104] though it remains at a planning phase.

Roads

The Via Baltica motorway (part of European route E67 from Helsinki to Prague) connects Tallinn to the Lithuanian-Polish border through Latvia. Frequent and affordable long-distance bus routes connect Tallinn with other parts of Estonia.

انخفاض المدينة

النقل

مدن شقيقة

دارتفورت, المملكة المتحدة

دارتفورت, المملكة المتحدة لوس جاتوس, الولايات المتحدة

لوس جاتوس, الولايات المتحدة Schwerin, ألمانيا

Schwerin, ألمانيا Kiel, ألمانيا

Kiel, ألمانيا Ghent, بلجيكا

Ghent, بلجيكا جوتنبرج, السويد

جوتنبرج, السويد Malmö, السويد

Malmö, السويد Riga, لاتيفيا

Riga, لاتيفيا أنابوليس, الولايات المتحدة

أنابوليس, الولايات المتحدة Groningen, هولندا

Groningen, هولندا Łomża, بولندا

Łomża, بولندا Gdańsk, بولندا

Gdańsk, بولندا Gdynia, بولندا

Gdynia, بولندا Białystok, بولندا

Białystok, بولندا سان بطرسبرج, روسيا

سان بطرسبرج, روسيا

Tallinn also has a mutual friendship with the city of Portland, Oregon, الولايات المتحدة and Kotka, Finland[بحاجة لمصدر]

انظر ايضا

معرض الصور

- Battle of Lyndanisse

- Castrum Danorum

- Evacuation of Tallinn (1941)

- Eurovision Song Contest 2002

- Legends of Tallinn

- Tallinn TV Tower

- Tallinn Marathon

- Tõnismägi

- Raeapteek

- Toompea

Gallery

- Ertg123.JPG

The city center (winter 2007)

وصلات خارجية

عامة

سفر

- Tallinn on Wikitravel

- Tallinna Lennujaam - Tallinn Airport

- Port of Tallinn

- Tallinn weather

- Tallinn Hotels and Travel

- article in Helsinki Times

صور وفيديو

- Digital Tallinn - Virtual tour (panoramas and photos)

- Real-time Web Camera

- QTVR fullscreen panoramas of the Tallinn city

خرائط

أخرى

- Tallinn at the Open Directory Project

- Soviet, Estonian and German Memorials and cemeteries in Tallinn at sites-of-memory.de

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت "Population by sex, age and place of residence after the 2017 administrative reform, 1 January". Statistics Estonia. Retrieved 22 مايو 2022.

- ^ "Tallinna elanike arv". Archived from the original on 9 مايو 2019. Retrieved 12 فبراير 2023.

- ^ "Gross domestic product by county (ESA 2010)". Px-Web. Statistics Estonia.

- ^ "Tallinn City Government 2023 budget totals €1.14 billion".

- ^ "Tal•linn". Dictionary.infoplease.com. Retrieved 20 مايو 2012.

- ^ "Definition of Tallinn". Encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 20 مايو 2012.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Spray, Aaron (30 يناير 2023). "Why Estonia's Historic Capital City Of Tallinn Is Worth Visiting". Thetravel.com. Retrieved 5 مارس 2023.

- ^ أ ب ,"Tallinn on noorem, kui õpikus kirjas!". Delfi. 28 أكتوبر 2003. Retrieved 6 يوليو 2017.

- ^ أ ب "Villu Kadakas: pringlikütid Vabaduse väljakul". 25 أبريل 2009.

- ^ "Country Profile – LegaCarta". Retrieved 26 نوفمبر 2019.

- ^ "Historic Centre (Old Town) of Tallinn". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 7 ديسمبر 1997. Retrieved 29 سبتمبر 2013.

- ^ Rooney, Ben (14 يونيو 2012). "The Many Reasons Estonia Is a Tech Start-Up Nation". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Germany, SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg (14 مارس 2015). "Start-ups in Tallinn: Estland, das Silicon Valley Europas? – SPIEGEL ONLINE – Netzwelt". Der Spiegel.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب Ingrid Teesalu (9 يونيو 2011). "It's Official: Tallinn To Become EU's IT Headquarters". ERR. Retrieved 27 أبريل 2012.

- ^ "Tech capitals of the world". The Age. 15 مايو 2012. Retrieved 20 مايو 2012.

- ^ Hankewitz, Sten (17 مارس 2022). "Tallinn in the top ten of the "Europe's cities of the future" ranking". Estonian World. Retrieved 7 أكتوبر 2022.

- ^ Fasman, The Geographer's Library, pp.17

- ^ أ ب Ertl, Alan (2008). Toward an Understanding of Europe. Universal-Publishers. p. 381. ISBN 978-1-59942-983-0.

- ^ Birnbaum, Stephen; Mayes Birnbaum, Alexandra (1992). Birnbaum's Eastern Europe. Harper Perennial. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-06-278019-5.

- ^ Fasman, Jon (2006). The Geographer's Library. Penguin. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-14-303662-3.

- ^ "A glance at the history and geology of Tallinn" by Jaak Nõlvak. In Wogogob 2004: Conference Materials Archived 20 يوليو 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Terras, Victor (1990). Handbook of Russian Literature. Yale University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-300-04868-1.

- ^ The Esthonian Review. University of California. 1919.

- ^ Tarvel, Enn (2016). "Chapter 14: Genesis of the Livonian town in the 13th century". In Murray, Alan (ed.). The North-Eastern Frontiers of Medieval Europe. Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-409-43680-5.

- ^ Ammas, Anneli (18 يناير 2003). "Pealinna esmamainimise aeg kahtluse all". Eesti Päevaleht. Retrieved 6 يوليو 2017.

- ^ "Miks ei usu ajaloolased Tallinna esmamainimisse 1154. aastal?". Horisont. 2003. Retrieved 6 يوليو 2017.

- ^ (in دنماركية)In 1219 Valdemar II of Denmark, leading the Danish fleet in connection with the Livonian Crusade, landed in an Estonian town of Lindanisse

- ^ "Salmonsens Konversations Leksikon". Runeberg.org. 19 يناير 2012. Retrieved 20 مايو 2012.

- ^ (in ألمانية) Reval's ältester Estnischer Name Lindanisse, Verhandlungen der gelehrten estnischen Gesellschaft zu Dorpat. Band 3, Heft 1. Dorpat 1854, p. 46–47

- ^ Singer, Nat A.; Steve Roman (2008). Tallinn in Your Pocket. In Your Pocket. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-01-406269-0.

- ^ Alas, Askur. "The mystery of Tallinn's Central Square" (in الإستونية). EE. Archived from the original on 5 نوفمبر 2008. Retrieved 29 أكتوبر 2008.

- ^ Turku ja Tallinna – Euroopan kulttuuripääkaupungit 2011

- ^ "Historic Centre (Old Town) of Tallinn". UNESCO. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 11 مارس 2022.

- ^ "Tallinn 2002". Eurovision Song Contest. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 11 مارس 2022.

- ^ Nikel, David (11 سبتمبر 2021). "Introducing Estonia's Tallinn, European Green Capital 2023". Integrated Whale Media Investments. Forbes. Retrieved 11 مارس 2022.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (6 يوليو 2022). EIB Group Sustainability Report 2021 (in الإنجليزية). European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5237-5.

- ^ Saarniit, Helen. "How can Estonia's transport and housing sectors contribute to cleaner air and a safer climate?". SEI (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Retrieved 26 يوليو 2022.

- ^ Pärli, Merilin (24 يناير 2023). "Critics: Tallinn's green capital program doesn't offer permanent changes". ERR. Retrieved 13 فبراير 2023.

- ^ Tallinn Annual Report 2011. Tallinn City Office. p. 41.

- ^ أ ب Vaher, Rein; Miindel, Avo; Raukas, Anto; Tavast, Elvi (2010). "Ancient buried valleys in the city of Tallinn and adjacent area" (PDF). Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences. 59 (1): 37–48. doi:10.3176/earth.2010.1.03.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- ^ أ ب ت "Погода и Климат – Климат Таллина". Pogoda.ru.net. Archived from the original on 7 يناير 2019. Retrieved 30 يناير 2021. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "pogoda" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةsun - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةtemp - ^ "Statistical Yearbook of Tallinn 2022" (in الإنجليزية). Tallinn city government. 19 مايو 2023. Retrieved 19 مايو 2023.

- ^ "01.01.2015". Archived from the original on 19 نوفمبر 2015. Retrieved 31 يناير 2016.

- ^ "POPULATION, 1 JANUARY by Sex, County, Ethnic nationality and Year". pub.stat.ee.

- ^ Eurostat (2004). Regions: Statistical yearbook 2004 (PDF). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. p. 115/135. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 مايو 2010.

- ^ "Tallinn arvudes / Statistical Yearbook of Tallinn" (in الإستونية and الإنجليزية). Tallinn City Council. 3 أغسطس 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 مايو 2012. Retrieved 1 أبريل 2012.

- ^ 1922 a. üldrahvalugemise andmed. Vihk I ja II, Rahva demograafiline koosseis ja korteriolud Eestis (in الإستونية and الفرنسية). Tallinn: Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo. 1924. p. 33. ISBN 9789916103067.

- ^ Rahvastiku koostis ja korteriolud. 1.III 1934 rahvaloenduse andmed. Vihk II (in الإستونية and الفرنسية). Tallinn: Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo. 1935. pp. 47–53. hdl:10062/4439.

- ^ Eesti Statistika : kuukiri 1942-03/04 (in الألمانية and الإستونية). Tallinn: Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo. 1942. pp. 66–67.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Statistikaamet (1995). Eesti rahvastik rahvaloenduste andmetel. I. (PDF) (in الإستونية and الإنجليزية). Tallinn: Grafinet. p. 66. ISBN 9985-826-17-5.

- ^ "RL222: RAHVASTIK ELUKOHA JA RAHVUSE JÄRGI". Estonian Statistical Database (in الإستونية).

- ^ "RL0429: RAHVASTIK RAHVUSE, SOO, VANUSERÜHMA JA ELUKOHA JÄRGI, 31. DETSEMBER 2011". Estonian Statistical Database.

- ^ "RL21429: Rahvastik Rahvuse, Soo, Vanuserühma Ja ELukoha (Haldusüksus) Järgi, 31. DETSEMBER 2021". Estonian Statistical Database (in الإستونية).

- ^ Kaja Koovit. "Half of Estonian GDP is created in Tallinn". Balticbusinessnews.com. Retrieved 20 مايو 2012.

- ^ "Half of the gross domestic product of Estonia is created in Tallinn". Estonian Statistics Office. Retrieved 20 مايو 2012.

- ^ Mark Ländler, "The Baltic Life: Hot Technology for Chilly Streets" Archived 5 يناير 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 13 December 2005.

- ^ Anthony Ha, "GameFounders: An Accelerator For European Game Startups", Techcrunch, 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Tallinn investing to enhance customer experience and business and operational opportunities". Airport Business. ACI EUROPE. 17 أكتوبر 2016. Retrieved 19 نوفمبر 2016.

- ^ "ERR: Tallinn hoping for return of Finnish tourists this summer". 23 مارس 2021.

- ^ ERR: Finnish tourist numbers on the rise – new generations traveling to Estonia

- ^ Arumäe, Liisu (9 أغسطس 2013). "Tallinnas suureneb Vene ja Aasia turistide arv". E24 Majandus (in الإستونية). Archived from the original on 19 سبتمبر 2016. Retrieved 5 نوفمبر 2013.

- ^ "Tänavune kruiisihooaeg tõi Tallinna esmakordselt üle poole miljoni reisija" (in الإستونية). Port of Tallinn. 11 أكتوبر 2013. Archived from the original on 21 سبتمبر 2017. Retrieved 5 نوفمبر 2013.

- ^ A study on the EU oil shale industry viewed in the light of the Estonian experience. A report by EASAC to the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy of the European Parliament. European Academies Science Advisory Council. May 2007. pp. 12–13, 18–19, 23–24, 28. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://www.easac.org/fileadmin/PDF_s/reports_statements/Study.pdf. Retrieved on 2 August 2015. - ^ "Muuga Harbour". Port of Tallinn. Retrieved 25 سبتمبر 2022.

- ^ "Reyktal AS fleet". Archived from the original on 18 يونيو 2010.

- ^ "MARKTBEAT shopping centre development report" (PDF). Cushman & Wakefield. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 مارس 2016. Retrieved 10 ديسمبر 2014.

- ^ "Regulation 1077/2011 establishing a European Agency for the operational management of large-scale IT systems in the area of freedom, security and justice". Retrieved 29 سبتمبر 2013.

- ^ "DGs – Home Affairs – What we do – Agencies". European Commission. Archived from the original on 27 يونيو 2012. Retrieved 29 سبتمبر 2013.

- ^ "Skype Jobs: Life at Skype". Jobs.skype.com. Archived from the original on 24 فبراير 2012. Retrieved 3 يونيو 2011.

- ^ Steve Roman (30 مايو 2012). "TeliaSonera Opens IT Development Center in Tallinn". ERR. Retrieved 7 يونيو 2012.

- ^ Vahemäe, Heleri (13 سبتمبر 2013). "Kuehne + Nagel joined ITL". E24 Majandus. Archived from the original on 5 نوفمبر 2013. Retrieved 5 نوفمبر 2013.

- ^ Schieler, Nicole (11 فبراير 2016). "arvato Financial Solutions opens global IT Development and Innovation centre in Tallinn". arvato. Archived from the original on 21 أغسطس 2016. Retrieved 21 أغسطس 2016.

- ^ "Ericsson Eesti planning to invest EUR 6.4 mln > Tallinn". Tallinn.ee. Archived from the original on 17 يونيو 2011. Retrieved 3 يونيو 2011.

- ^ Raivo Sormunen. "aripaev.ee – Skandinaavia uue börsifirma finantskeskus tuleb Tall". Ap3.ee. Archived from the original on 29 سبتمبر 2011. Retrieved 3 يونيو 2011.

- ^ "Tallinn Sightseeing, Museums & Attractions". Tallinn. n.d. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2016.

- ^ "ESTONIAN HISTORY MUSEUM". Eesti Asaloomuuseum. Archived from the original on 5 مايو 2016. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Estonian History Museum – Great Guild Hall". Tallinn. n.d. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2016.

- ^ "Estonian Maritime Museum – Fat Margaret's Tower". Tallinn. n.d. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Tallinna Lunnamuuseum". Lunnamuuseum.ee. n.d. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2016.

- ^ "ABOUT THE MUSEUM". linnamuuseum.ee. n.d. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2016.

- ^ "Museum of Occupations". Visitestonia.com. n.d. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2016.

- ^ "Hotel Viru & KGB Museum". Visittallinn.ee. n.d. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2016.

- ^ "Estonian Museum of Natural History". Visittallinn.ee. n.d. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2016.

- ^ "Estonian Health Care Museum". Visitestonia.com. n.d. Retrieved 13 سبتمبر 2016.

- ^ "Kumu – Art lives here!". Kumu.ekm.ee. n.d. Archived from the original on 25 أبريل 2017. Retrieved 13 سبتمبر 2016.

- ^ "About the museum". Kadriorumuuseum.ekm.ee. n.d. Archived from the original on 14 سبتمبر 2016. Retrieved 13 سبتمبر 2016.

- ^ "Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design". Etdm.ee. n.d. Retrieved 13 سبتمبر 2016.

- ^ "Museum of Estonian Drinking Culture". Visittallinn.ee. n.d. Retrieved 13 سبتمبر 2016.

- ^ أ ب Estonian Song and Dance Celebrations Estonian Song and Dance Celebration Foundation

- ^ "Lauluväljakul oli teisel kontserdil 110 000 inimest". Delfi.

- ^ "Estonia – Estonia is a place for independent minds". estonia.ee. Archived from the original on 19 سبتمبر 2016. Retrieved 18 سبتمبر 2016.

- ^ Zunes, Stephen (أبريل 2009). "Estonia's Singing Revolution (1986–1991)". International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. Retrieved 9 يناير 2017.

- ^ "Raekoja platsil valmib maailma pikim kiluvõileib". Tallinn. Postimees (in الإستونية). 14 مايو 2014. Archived from the original on 13 أكتوبر 2016. Retrieved 13 أكتوبر 2016.

- ^ "Martsipani ajalugu". kohvikmaiasmokk.ee (in الإستونية). AS Kalev. Retrieved 13 أكتوبر 2016.

- ^ Gendlin, Vladimir; Shaposhnikov, Vasily (19 مايو 2003). "Estonia // SPRATS IN LIQUEUR". Kommersant. Moscow. Archived from the original on 13 أكتوبر 2016. Retrieved 13 أكتوبر 2016.

- ^ "Kuidas vaeste lesknaiste toidust sai Tallinna sümbol". Tarbija24. Postimees (in الإستونية). 25 فبراير 2013. Archived from the original on 14 أكتوبر 2016. Retrieved 13 أكتوبر 2016.

- ^ "Statistical Yearbook of Tallinn 2015". tallinn.ee. Archived from the original on 19 نوفمبر 2015. Retrieved 24 أبريل 2021.

- ^ Varema, Remeo (1998). "TALLINN TRAM - 110 YEARS". Tallinna tramm 110 aastat. Vello Talves. Archived from the original on 4 مارس 2016. Retrieved 6 يوليو 2015.

- ^ "History of tram transport". Aktsiaselts Tallinna Linnatransport (TLT). Retrieved 22 سبتمبر 2021.

- ^ Willsher, Kim (15 أكتوبر 2018). "'I leave the car at home': how free buses are revolutionising one French city". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 أكتوبر 2018.

- ^ Mike Collier. "Helsinki mayor still believes in Tallinn tunnel", The Baltic Times, 3 April 2008. Retrieved on 2021-09-13.

- Mark Landler, "The Baltic Life: Hot Technology for Chilly Streets", The New York Times, December 13, 2005

- Scooch 'Flying the Flag (For You)', Warner Music UK, 2007 Eurovision Song Contest Entrant [UK]

قالب:World Heritage Sites in Estonia

قالب:Tallinn landmarks

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with دنماركية-language sources (da)

- Articles with ألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 الإستونية-language sources (et)

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Use dmy dates from March 2020

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing إستونية-language text

- صفحات تستخدم جدول مستوطنة بقائمة محتملة لصفات المواطن

- Articles containing explicitly cited عربية-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- مقالات ينقصها مصادر موثوقة

- مقالات ينقصها مصادر موثوقة from May 2023

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة from May 2023

- Vague or ambiguous time from December 2016

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج تمحيص الحقائق from July 2017

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تمحيص حقائق

- Lang and lang-xx template errors

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- تالين

- مدن ساحلية

- موانئ إستونيا

- موانئ بحر البلطيق

- أعضاء الرابطة الهانزية

- بلديات إستونيا

- عواصم اوروپا

- مدن إستونيا

- مواقع التراث العالمي في إستونيا