يوىژي

| إجمالي التعداد | |

|---|---|

| Some 100,000 to 200,000 horse archers, according to the Shiji, Chapter 123.[8] The Hanshu Chapter 96A records: 100,000 households, 400,000 people with 100,000 able to bear arms.[9] | |

| المناطق ذات التجمعات المعتبرة | |

| Western China | (pre-2nd century BC)[8] |

| Central Asia | (2nd century BC-1st century AD) |

| Northern India | (1st century AD-4th century AD) |

| اللغات | |

| Bactrian[10] (in Bactria in the 1st century AD) | |

| الدين | |

| Buddhism Hinduism[11] Jainism[12] Shamanism Zoroastrianism Manichaeism Kushan deities | |

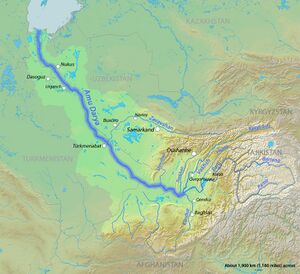

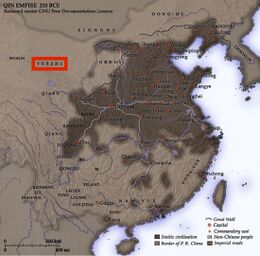

The Yuezhi (Chinese: 月氏; pinyin: Yuèzhī, Ròuzhī or Rùzhī; Wade–Giles: Yüeh4-chih1, Jou4-chih1 or Ju4-chih1;) were an ancient people first described in Chinese histories as nomadic pastoralists living in an arid grassland area in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC. After a major defeat at the hands of the Xiongnu in 176 BC, the Yuezhi split into two groups migrating in different directions: the Greater Yuezhi (Dà Yuèzhī 大月氏) and Lesser Yuezhi (Xiǎo Yuèzhī 小月氏). This started a complex domino effect that radiated in all directions and, in the process, set the course of history for much of Asia for centuries to come.[13] The Greater Yuezhi initially migrated northwest into the Ili Valley (on the modern borders of China and Kazakhstan), where they reportedly displaced elements of the Sakas. They were driven from the Ili Valley by the Wusun and migrated southward to Sogdia and later settled in Bactria. The Greater Yuezhi have consequently often been identified with peoples mentioned in classical European sources as having overrun the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, like the Tókharioi (Greek Τοχάριοι; Sanskrit Tukhāra) and Asii (or Asioi). During the 1st century BC, one of the five major Greater Yuezhi tribes in Bactria, the Kushanas (Chinese: 貴霜; pinyin: Guìshuāng), began to subsume the other tribes and neighbouring peoples. The subsequent Kushan Empire, at its peak in the 3rd century AD, stretched from Turfan in the Tarim Basin in the north to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain of India in the south. The Kushanas played an important role in the development of trade on the Silk Road and the introduction of Buddhism to China.

The Lesser Yuezhi migrated southward to the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Some are reported to have settled among the Qiang people in Qinghai, and to have been involved in the Liang Province Rebellion (184–221 AD) against the Eastern Han dynasty. Another group of Yuezhi is said to have founded the city state of Cumuḍa (now known as Kumul and Hami) in the eastern Tarim. A fourth group of Lesser Yuezhi may have become part of the Jie people of Shanxi, who established the Later Zhao state of the 4th century AD (although this remains controversial).

Many scholars believe that the Yuezhi were an Indo-European people.[14][15] Although some scholars have associated them with artifacts of extinct cultures in the Tarim Basin, such as the Tarim mummies and texts recording the Tocharian languages, the evidence for any such link is purely circumstantial.[16]

Earliest references in Chinese texts

Three pre-Han texts mention peoples who appear to be the Yuezhi, albeit under slightly different names.[17]

- The philosophical tract Guanzi (73, 78, 80 and 81) mentions nomadic pastoralists known as the Yúzhī 禺氏 (Old Chinese: *ŋʷjo-kje) or Niúzhī 牛氏 (OC: *ŋʷjə-kje), who supplied jade to the Chinese.[18][17] (The Guanzi is now generally believed to have been compiled around 26 BC, based on older texts, including some from the Qi state era of the 11th to 3rd centuries BC. Most scholars no longer attribute its primary authorship to Guan Zhong, a Qi official in the 7th century BC.[19]) The export of jade from the Tarim Basin, since at least the late 2nd millennium BC, is well-documented archaeologically. For example, hundreds of jade pieces found in the Tomb of Fu Hao (ح. 1200 BC) originated from the Khotan area, on the southern rim of the Tarim Basin.[20] According to the Guanzi, the Yúzhī/Niúzhī, unlike the neighbouring Xiongnu, did not engage in conflict with nearby Chinese states.

- The epic novel Tale of King Mu, Son of Heaven (early 4th century BC) also mentions a plain of Yúzhī 禺知 (OC: *ŋʷjo-kje) to the northwest of the Zhou lands.[17]

- Chapter 59 of the Yi Zhou Shu (probably dating from the 4th to 1st century BC) refers to a Yúzhī 禺氏 (OC: *ŋʷjo-kje) people living to the northwest of the Zhou domain and offering horses as tribute. A late supplement contains the name Yuèdī 月氐 (OC: *ŋʷjat-tij), which may be a misspelling of the name Yuèzhī 月氏 (OC: *ŋʷjat-kje) found in later texts.[17]

In the 1st century BC, Sima Qian – widely regarded as the founder of Chinese historiography – describes how the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) bought jade and highly valued military horses from a people that Sima Qian called the Wūzhī 烏氏 (OC: *ʔa-kje), led by a man named Luo. The Wūzhī traded these goods for Chinese silk, which they then sold on to other neighbours.[21][22] This is probably the first reference to the Yuezhi as a lynchpin in trade on the Silk Road,[23] which in the 3rd century BC began to link Chinese states to Central Asia and, eventually, the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Europe.

Nomadic artifacts in Gansu and Ningxia (5th-4th century BC)

Numerous nomadic artifacts are attributed to the areas of southern Ningxia and southeastern Gansu during the period of the 5th-4th century BC. They are quite similar to the works of the nomadic Ordos culture further east, and reflect strong Scythian influences.[24] Some of these artifacts were sinicized by the neighbouring Qin state in China, probably also for nomadic consumption.[24] Nomadic figures with long noses riding on a camel also appear regularly in southern Ningxia from the 4th century BC.[24]

Etymology

Hakan Aydemir, assistant professor at Istanbul Medeniyet University, reconstructs the ethnonym *Arki ~ *Yarki which underlay Chinese transcriptions 月氏 (Old Chinese *ŋwat-tēɦ ~[ŋ]ʷat-tēɦ) and 月支 (Later Han Chinese *ŋyat-tśe) as well as various other foreign transcriptions and Tocharian A ethnonym Ārśi.[28] Aydemir suggests that *Arki ~ *Yarki is etymologically Indo-European.[29]

Account of Zhang Qian

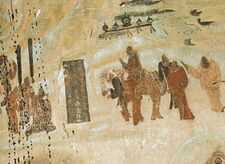

The earliest detailed account of the Yuezhi is found in chapter 123 of the Records of the Great Historian by Sima Qian, describing a mission of Zhang Qian in the late 2nd century BC. Essentially the same text appears in chapter 61 of the Book of Han, though Sima Qian has added occasional words and phrases to clarify the meaning.[30]

Both texts use the name Yuèzhī 月氏 (OC: *ŋʷjat-kje), composed of characters meaning "moon" and "clan" respectively.[17] Several different romanizations of this Chinese-language name have appeared in print. The Iranologist H. W. Bailey preferred Üe-ṭşi.[31] Another modern Chinese pronunciation of the name is Ròuzhī, based on the thesis that the character 月 in the name is a scribal error for 肉; however Thierry considers this thesis "thoroughly wrong".[17]

Yuezhi and Xiongnu

The account begins with the Yuezhi occupying the grasslands to the northwest of China at the beginning of the 2nd century BC:

The Great Yuezhi was a nomadic horde. They moved about following their cattle, and had the same customs as those of the Xiongnu. As their soldiers numbered more than hundred thousand, they were strong and despised the Xiongnu. In the past, they lived in the region between Dunhuang and Qilian.

— Book of Han، 61

The area between the Qilian Mountains and Dunhuang lies in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, but no archaeological remains of the Yuezhi have yet been found in this area.[16] Some scholars have argued that "Dunhuang" should be Dunhong, a mountain in the Tian Shan, and that Qilian should be interpreted as a name for the Tian Shan. They have thus placed the original homeland of the Yuezhi 1,000 km further northwest in the grasslands to the north of the Tian Shan (in the northern part of modern Xinjiang).[16][32] Other authors suggest that the area identified by Sima Qian was merely the core area of an empire encompassing the western part of the Mongolian plain, the upper reaches of the Yellow River, the Tarim Basin and possibly much of central Asia, including the Altai Mountains, the site of the Pazyryk burials of the Ukok Plateau.[33]

By the late 3rd century the Xiongnu monarch Touman even sent his eldest son Modu as a hostage to the Yuezhi. The Yuezhi often attacked their neighbour the Wusun to acquire slaves and pasture lands. Wusun originally lived together with the Yuezhi in the region between Dunhuang and Qilian Mountain. The Yuezhi attacked the Wusuns, killed their monarch Nandoumi and took his territory. The son of Nandoumi, Kunmo fled to the Xiongnu and was brought up by the Xiongnu monarch.

Gradually the Xiongnu grew stronger, and war broke out with the Yuezhi. There were at least four wars according to the Chinese accounts. The first war broke out during the reign of the Xiongnu monarch Touman (who died in 209 BC) who suddenly attacked the Yuezhi. The Yuezhi wanted to kill Modu, the son of the Xiongnu king Touman kept as a hostage to them, but Modu stole a good horse from them and managed to escape to his country. He subsequently killed his father and became ruler of the Xiongnu.[36] It appears that the Xiongnu did not defeat the Yuezhi in this first war. The second war took place in the 7th year of the Modu era (203 BC). In this war, a large area of the territory originally belonging to the Yuezhi was seized by the Xiongnu and the hegemony of the Yuezhi started to shake. The third war probably was in 176 BC (or shortly before), and the Yuezhi were badly defeated.

Shortly before 176 BC, led by one of Modu's tribal chiefs, the Xiongnu invaded Yuezhi territory in the Gansu region and achieved a crushing victory.[37][38] Modu boasted in a letter (174 BC) to the Han emperor[39] that due to "the excellence of his fighting men, and the strength of his horses, he has succeeded in wiping out the Yuezhi, slaughtering or forcing to submission every number of the tribe." The son of Modu, Laoshang Chanyu (ruled 174–166 BC), subsequently killed the king of the Yuezhi and, in accordance with nomadic traditions, "made a drinking cup out of his skull." (Shiji 123.[8])

Nevertheless, in about 173 BC, the Wusun were apparently defeated by the Yuezhi, who killed a Wusun king (kunmi Chinese: 昆彌 or kunmo Chinese: 昆莫) known as Nandoumi (Chinese: 難兜靡).[37][40]

Exodus of the Great Yuezhi

After their defeat by the Xiongnu, the Yuezhi split into two groups. The Lesser or Little Yuezhi (Xiao Yuezhi) moved to the "southern mountains", believed to be the Qilian Mountains on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau, to live with the Qiang.[41]

The so-called Greater or Great Yuezhi (Dà Yuèzhī, 大月氏) began migrating north-west in about 165 BC,[42] first settling in the Ili valley, immediately north of the Tian Shan mountains, where they defeated the Sai (Sakas): "The Yuezhi attacked the king of the Sai who moved a considerable distance to the south and the Yuezhi then occupied his lands" (Book of Han 61 4B). This was "the first historically recorded movement of peoples originating in the high plateaus of Asia."[43]

In 132 BC the Wusun, in alliance with the Xiongnu and out of revenge from an earlier conflict, again managed to dislodge the Yuezhi from the Ili Valley, forcing them to move south-west.[37] The Yuezhi passed through the neighbouring urban civilization of Dayuan (in Ferghana) and settled on the northern bank of the Oxus, in the region of northern Bactria, or Transoxiana (modern Tajikistan and Uzbekistan).

Visit of Zhang Qian

The Yuezhi were visited in Transoxiana by a Chinese mission, led by Zhang Qian in 126 BC,[44] which sought an offensive alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu. Zhang Qian, who spent a year in Transoxiana and Bactria, wrote a detailed account in the Shiji, which gives considerable insight into the situation in Central Asia at the time.[45] The request for an alliance was denied by the son of the slain Yuezhi king, who preferred to maintain peace in Transoxiana rather than seek revenge.

Zhang Qian also reported:

the Great Yuezhi live 2,000 or 3,000 li [832–1,247 kilometers] west of Dayuan, north of the Gui [Oxus ] river. They are bordered on the south by Daxia [Bactria], on the west by Anxi [Parthia], and on the north by Kangju [beyond the middle Jaxartes/Syr Darya]. They are a nation of nomads, moving from place to place with their herds, and their customs are like those of the Xiongnu. They have some 100,000 or 200,000 archer warriors.

— Shiji، 123[8]

In a sweeping analysis of the physical types and cultures of Central Asia, Zhang Qian reports:

Although the states from Dayuan west to Anxi (Parthia), speak rather different languages, their customs are generally similar and their languages mutually intelligible. The men have deep-set eyes and profuse beards and whiskers. They are skilful at commerce and will haggle over a fraction of a cent. Women are held in great respect, and the men make decisions on the advice of their women.

— Shiji، 123[46]

Zhang Qian also described the remnants of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom on the other side of the Oxus River (Chinese Gui) as a number of autonomous city-states under Yuezhi suzerainty:[47]

Daxia is located over 2,000 li southwest of Dayuan, south of the Gui river. Its people cultivate the land and have cities and houses. Their customs are like those of Ta-Yuan. It has no great ruler but only a number of petty chiefs ruling the various cities. The people are poor in the use of arms and afraid of battle, but they are clever at commerce. After the Great Yuezhi moved west and attacked the lands, the entire country came under their sway. The population of the country is large, numbering some 1,000,000 or more persons. The capital is called the city of Lanshi and has a market where all sorts of goods are bought and sold.

— Shiji، 123[48]

Later Chinese accounts

The next mention of the Yuezhi in Chinese sources is found in chapter 96A of the Book of Han (completed in AD 111), relating to the early 1st century BC. At this time, the Yuezhi are described as occupying the whole of Bactria, organized into five major tribes or xīhóu (Ch:翖侯, "Allied Prince").[49] These tribes were known to the Chinese as:

- Xiūmì (休密) in Western Wakhān and Zibak;

- Guìshuāng (貴霜) in Badakhshan and adjoining territories north of the Oxus;

- Shuāngmí (雙靡) in the region of Shughnan or Chitral.[50]

- Xīdùn (肸頓) in the region of Balkh, and;

- Dūmì (都密) in the region of Termez.[51]

The Book of the Later Han (5th century CE) also records the visit of Yuezhi envoys to the Chinese capital in 2 BC, who gave oral teachings on Buddhist sutras to a student, suggesting that some Yuezhi already followed the Buddhist faith during the 1st century BC (Baldev Kumar 1973).

Chapter 88 of the Book of the Later Han relies on a report of Ban Yong, based on the campaigns of his father Ban Chao in the late 1st century AD. It reports that one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi, the Guishuang, had managed to take control of the tribal confederation:[55]

More than a hundred years later, the xihou of Guishuang, named Qiujiu Que (Ch: 丘就卻, Kujula Kadphises) attacked and exterminated the four other xihou. He set himself up as king of a kingdom called Guishuang (Kushan). He invaded Anxi (Parthia) and took the Gaofu (Ch:高附, Kabul) region. He also defeated the whole of the kingdoms of Puda (Ch: 濮達) and Jibin (Ch: 罽賓, Kapiśa-Gandhāra). Qiujiu Que (Kujula Kadphises) was more than eighty years old when he died. His son, Yan Gaozhen (Ch:閻高珍) (Vima Takto), became king in his place. He returned and defeated Tianzhu (Northwestern India) and installed a General to supervise and lead it. The Yuezhi then became extremely rich. All the kingdoms call [their king] the Guishuang (Kushan) king, but the Han call them by their original name, Da Yuezhi.

A later Chinese annotation in Zhang Shoujie's Shiji (quoting Wan Zhen 萬震 in Nánzhōuzhì 南州志 ["Strange Things from the Southern Region"], a now-lost 3rd-century text from the Wu kingdom), describes the Kushans as living in the same general area north of India, in cities of Greco-Roman style, and with sophisticated handicraft. The quotes are dubious, as Wan Zhen probably never visited the Yuezhi kingdom through the Silk Road, though he might have gathered his information from the trading ports in the coastal south.[58] Chinese sources continued to use the name Yuezhi and seldom used the Kushan (or Guishuang) as a generic term:

The Great Yuezhi are located about seven thousand li [2,910 km] north of India. Their land is at a high altitude; the climate is dry; the region is remote. The king of the state calls himself "son of heaven". There are so many riding horses in that country that the number often reaches several hundred thousand. City layouts and palaces are quite similar to those of Daqin [the Roman Empire]. The skin of the people there is reddish white. People are skilful at horse archery. Local products, rarities, treasures, clothing, and upholstery are very good, and even India cannot compare with it.

— Wan Zhen (3rd century AD)[59]

Kushana

The Central Asian people who called themselves Kushana, w were among the conquerors of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom during the 2nd century BC,[64] and are widely believed to have originated as a dynastic clan or tribe of the Yuezhi.[65][66] The area of Bactria they settled came to be known as Tokharistan. Because some inhabitants of Bactria became known as Tukhāra (Sanskrit) or Tókharoi (Τοχάριοι; Greek), these names later became associated with the Yuezhi.

The Kushana spoke Bactrian, an Eastern Iranian language.[67]

Bactria

In the 3rd century BC, Bactria had been conquered by the Greeks under Alexander the Great and since settled by the Hellenistic civilization of the Seleucids.

The resulting Greco-Bactrian Kingdom lasted until the 2nd century BC. The area came under pressure from various nomadic peoples and the Greek city of Alexandria on the Oxus was apparently burnt to the ground in about 145 BC.[68] The last Greco-Bactrian king, Heliocles I, retreated and moved his capital to the Kabul Valley. In about 140–130 BC, the Greco-Bactrian state was conquered by the nomads and dissolved. The Greek geographer Strabo mentions this event in his account of the central Asian tribes he called "Scythians":[69]

All, or the greatest part of them, are nomads. The best known tribes are those who deprived the Greeks of Bactriana: the Asii, Pasiani, Tochari, and Sacarauli, who came from the country on the other side of the Jaxartes [Syr Darya], opposite the Sacae and Sogdiani.

Writing in the 1st century BC, the Roman historian Pompeius Trogus attributed the destruction of the Greco-Bactrian state to the Sacaraucae and the Asiani "kings of the Tochari".[69] Both Pompeius and the Roman historian Justin (2nd century AD) record that the Parthian king Artabanus II was mortally wounded in a war against the Tochari in 124 BC.[71] Several relationships between these tribes and those named in Chinese sources have been proposed, but remain contentious.[69]

After they settled in Bactria, the Yuezhi became Hellenized to some degree – as shown by their adoption of the Greek alphabet and by some remaining coins, minted in the style of the Greco-Bactrian kings, with the text in Greek.[72]

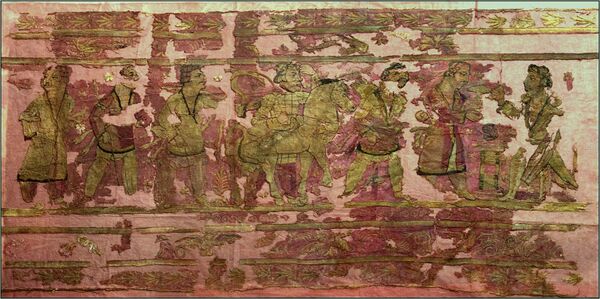

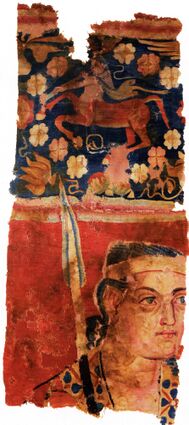

Noin-Ula carpets

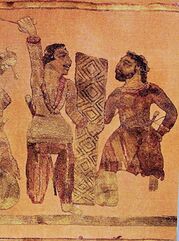

According to Sergey Yatsenko, the carpets with vivid embroidered scenes discovered in Noin-Ula were made by the Yuezhi in Bactria, and were obtained by the Xiongnu through commercial exchange or tributary payment, as the Yuezhi may have remained tributaries of the Xiongnu for a long time following their defeat. Embroidered carpets were among the highest-prized luxury items for the Xiongnu. The figures depicted in the carpets are believed to reflect the clothing and customs of the Yuezhi while they were in Bactria in the 1st century BCE-1st century CE.[73]

Tillya Tepe

The graves of Tillya Tepe, complete with numerous artifacts, dated to the period between the 1st century BCE and the 1st century CE, probably belonged to the Yuezhis/ early Kushans after the fall of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and before the rise of the Kushan Empire.[74] They correspond to a time when the Yuezhis had not yet encountered Buddhism.[74]

In the Hindu Kush

The area of the Hindu Kush (Paropamisadae) was ruled by the western Indo-Greek king until the reign of Hermaeus (reigned ح. 90 BC–70 BC). After that date, no Indo-Greek kings are known in the area. According to Bopearachchi, no trace of Indo-Scythian occupation (nor coins of major Indo-Scythian rulers such as Maues or Azes I) have been found in the Paropamisade and western Gandhara. The Hindu Kush may have been subsumed by the Yuezhi,[البحث الأصلي؟] who by then had been dominated by Greco-Bactria for almost two centuries.

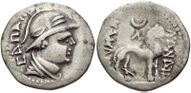

As they had done in Bactria with their copying of Greco-Bactrian coinage, the Yuezhi copied the coinage of Hermeaus on a vast scale, up to around 40 AD, when the design blends into the coinage of the Kushan king Kujula Kadphises. Such coins may provide the earliest known names of Yuezhi yabgu (a minor royal title, similar to prince), namely Sapadbizes[البحث الأصلي؟] and/or Agesiles, who both lived in or about 20 BC.

Kushan Empire

Obv: Bust of Heraios, with Greek royal headband.

Rev: Horse-mounted King, crowned with a wreath by the Greek goddess of victory Nike. Greek legend: TVPANNOVOTOΣ HΛOV – ΣΛNΛB – KOÞÞANOY "The Tyrant Heraios, Sanav (meaning unknown), of the Kushans"

After that point, they extended their control over the northwestern area of the Indian subcontinent, founding the Kushan Empire, which was to rule the region for several centuries.[75][66][76] Despite their change of name, most Chinese authors continued to refer to the Kushanas as the Yuezhi.

The Kushanas expanded to the east during the 1st century AD. The first Kushan emperor, Kujula Kadphises, ostensibly associated himself with King Hermaeus on his coins.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The Kushanas integrated Buddhism into a pantheon of many deities and became great promoters of Mahayana Buddhism, and their interactions with Greek civilization helped the Gandharan culture and Greco-Buddhism flourish.

During the 1st and 2nd centuries, the Kushan Empire expanded militarily to the north and occupied parts of the Tarim Basin, putting them at the center of the lucrative Central Asian commerce with the Roman Empire. The Kushanas collaborated militarily with the Chinese against their mutual enemies. This included a campaign with the Chinese general Ban Chao against the Sogdians in 84 CE, when the latter were trying to support a revolt by the king of Kashgar. In around AD 85,[بحاجة لمصدر] the Kushanas also assisted the Chinese in an attack on Turpan, east of the Tarim Basin.

Following the military support provided to the Han, the Kushan emperor requested a marriage alliance with a Han princess and sent gifts to the Chinese court in expectation that this would occur. After the Han court refused, a Kushan army 70,000 strong marched on Ban Chao in 86 AD. The army was apparently exhausted by the time it reached its objective and was defeated by the Chinese force. The Kushanas retreated and later paid tribute to the Chinese emperor Han He (89–106).

In about 120 AD, Kushan troops installed Chenpan—a prince who had been sent as a hostage to them and had become a favorite of the Kushan Emperor—on the throne of Kashgar, thus expanding their power and influence in the Tarim Basin.[77] There they introduced the Brahmi script, the Indian Prakrit language for administration, and Greco-Buddhist art, which developed into Serindian art.

Following this territorial expansion, the Kushanas introduced Buddhism to northern and northeastern Asia, by both direct missionary efforts and the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese.[78] Major Kushan missionaries and translators included Lokaksema (born ح. 147 CE) and Dharmaraksa (ح. 233), both of whom were influential translators of the Mahayana sutras into Chinese. They went to China and established translation bureaus, thereby being at the center of the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In the Records of the Three Kingdoms (chap. 3), it was recorded that in 229 AD, "The king of the Da Yuezhi [Kushanas], Bodiao 波調 (Vasudeva I), sent his envoy to present tribute, and His Majesty (Emperor Cao Rui) granted him the title of King of the Da Yuezhi Intimate with the Wei (Ch: 親魏大月氏王, Qīn Wèi Dà Yuèzhī Wáng)."

Soon afterwards, the military power of the Kushanas began to decline. The rival Sasanian Empire of Persia extended its dominion into Bactria during the reign of Ardashir I around 230 CE. The Sasanians also occupied neighboring Sogdia by 260 AD and made it into a satrapy.[79]

During the course of the 3rd and 4th centuries, the Kushan Empire was divided and conquered by the Sasanians, the Hephthalite tribes from the north,[80] and the Gupta and Yaudheya empires from India.

Later references to the Lesser Yuezhi

Xiao Yuezhi refers to the less militarized Yuezhi who settled in northern China (following the migration of the Greater Yuezhi).[81] The term is used of peoples in locations as diverse as Tibet, Qinghai, Shanxi and the Tarim Basin.

Some of the Lesser Yuezhi settled among the Qiang people of Huangzhong, Qinghai, according to archaeologist Sophia-Katrin Psarras.[82] Yuezhi and Qiang were said to be among members of the Auxiliary of Loyal Barbarians From Huangzhong that mutinied against the Han dynasty, in the Liangzhou Rebellion (184–221 CE).[83]

Elements of the Lesser Yuezhi are said to have been part of the Jie people, who originated from Yushe County in Shanxi.[84] Other theories link the Jie more strongly to the Xiongnu, Kangju, or the Tocharian-speaking peoples of the Tarim. Led by Shi Le (Emperor Ming of Later Zhao), the Jie people established the Later Zhao dynasty (319–351). The Jie populations were later massacred by Ran Min of the short-lived Ran Wei dynasty during the Wei–Jie war.

In Tibet, the Gar or mGar – a clan name associated with blacksmiths - may have been descended from tbe Lesser Yuezhi who resettled in Qiang in 162 BC.[85]

A Chinese monk named Gao Juhui, who traveled to the Tarim Basin in the 10th century, described the Zhongyun (仲雲; Wade–Giles Tchong-yun) as descendants of the Lesser Yuezhi.[86] This was the city state of Cumuḍa (also Cimuda or Cunuda), south of Lop Nur in the eastern Tarim.[31] (Following the subsequent settlement of Uyghur-speaking people in the area, Cumuḍa became known as Čungul, Xungul and Kumul. Under subsequent Han Chinese influence, it became known as Hami.)

Whatever their fate may have been, the Xiao Yuezhi ceased to be identifiable by that name and appear to have been subsumed by other ethnicities, including Tibetans, Uyghurs and Han.

Proposed links to other groups

The relationship between the Yuezhi and other Central Asian peoples is unclear. Based on claimed similarities of names, different scholars have linked them to several groups, but none of these identifications is widely accepted.[89]

Mallory and Mair suggest that the Yuezhi and Wusun were among the nomadic peoples, at least some of whom spoke Iranian languages, who moved into northern Xinjiang from the Central Asian steppe in the 2nd millennium BC.[90]

Scholars such as Edwin Pulleyblank, Josef Markwart, and László Torday, suggest that the name Iatioi—a Central Asian people mentioned by Ptolemy in Geography (AD 150)—may also be an attempt to render Yuezhi.[91]

There has been only limited scholarly support for a theory developed by W. B. Henning, who proposed that the Yuezhi were descended from the Guti (or Gutians) and an associated, but little known tribe known as the Tukri, who were native to the Zagros Mountains (modern Iran and Iraq), during the mid-3rd millennium BC. In addition to phonological similarities between these names and *ŋʷjat-kje and Tukhāra, Henning pointed out that the Guti could have migrated from the Zagros to Gansu,[92] by the time that the Yuezhi entered the historical record in China, during the 1st millennium BC. However, the only material evidence presented by Henning, namely similar ceramic ware, is generally considered to be far from conclusive.[59]

Proposed links with the Abhira,[93] Aorsi, Asii, Getae, Goths, Gushi, Jat, Massagetae,[94][95][96] and other groups have also gathered little support.[89]

Yuezhi-Tocharian hypothesis

When manuscripts dating from the 6th to 8th centuries AD written in two hitherto-unknown Indo-European languages were discovered in the northern Tarim Basin, the early 20th-century linguist Friedrich W. K. Müller identified them with the enigmatic "twγry ("Toγari") language" used to translate Indian Buddhist Sanskrit texts and mentioned as the source of an Old Turkic (Uyghur) manuscript.[97][98] Müller then proposed to connect the name "Toγari" (Togar/Tokar) to the Tókharoi people of Tokharistan (themselves associated with the Yuezhi) described in early Greek histories.[97][98] He thus referred to the newly discovered languages as "Tocharian", which became the common name for both the languages of the Tarim manuscripts and the people who produced them.[67][99] Most historians have been rejecting the identification of the Tocharians of the Tarim with the Tókharoi of Bactria, mainly because they are not known to have spoken any languages other than Bactrian, a quite dissimilar Eastern Iranian language.[10][100] Other scholars suggest that the Yuezhi/Kushanas may previously have spoken Tocharian before shifting to Bactrian on their arrival in Bactria, an example of an invading or colonising elite adopting a local language (as also seen for the Greeks, the Turks or the Arabs upon their successive settlements in Bactria).[101][102] However, while Tocharian contains some loanwords from Bactrian, there are no traces of Tocharian in Bactrian.[67]

Another possible endonym of the Yuezhi was put forward by H. W. Bailey, who claimed that they were referred to, in 9th and 10th century Khotan Saka Iranian texts, as the Gara. According to Bailey, the Tu Gara ("Great Gara") were the Great Yuezhi.[31] This is consistent with the Ancient Greek Τόχαροι Tokharoi (Latinised Tochari) in reference to the faction of the Kushans that conquered Bactria, as well as the Tibetan language name Gar (or mGar), for the members of the Lesser Yuezhi who settled in the Tibetan Empire.

See also

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| المواضيع الهندو-أوروپية |

|---|

|

- Iranians in China

- Pre-Islamic period of Afghanistan

- Indo-Parthian Kingdom

- Indo-Sassanid

- Hephthalite

- History of the central steppe

- History of China

- History of Afghanistan

- History of India

References

- ^ أ ب Betts, Alison; Vicziany, Marika; Jia, Peter Weiming; Castro, Angelo Andrea Di (19 December 2019). The Cultures of Ancient Xinjiang, Western China: Crossroads of the Silk Roads (in الإنجليزية). Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-78969-407-9.

In Noin-Ula (Noyon Uul), Mongolia, the remarkable elite Xiongnu tombs have revealed textiles that are linked to the pictorial tradition of the Yuezhi: the decorative faces closely resemble the Khalchayan portraits, while the local ornaments have integrated elements of Graeco-Roman design. These artifacts were most probably manufactured in Bactria

- ^ Francfort, Henri-Paul (1 January 2020). "Sur quelques vestiges et indices nouveaux de l'hellénisme dans les arts entre la Bactriane et le Gandhāra (130 av. J.-C.-100 apr. J.-C. environ)". Journal des Savants (in الإنجليزية): 26–27, Fig.8 "Portrait royal diadémé Yuezhi" ("Diademed royal portrait of a Yuezhi").

- ^ أ ب Considered as Yuezhi-Saka or simply Yuezhi in Polos'mak, Natalia V.; Francfort, Henri-Paul; Tsepova, Olga (2015). "Nouvelles découvertes de tentures polychromes brodées du début de notre ère dans les "tumuli" n o 20 et n o 31 de Noin-Ula (République de Mongolie)". Arts Asiatiques. 70: 3–32. doi:10.3406/arasi.2015.1881. ISSN 0004-3958. JSTOR 26358181.

p.3: "These tapestries were apparently manufactured in Bactria or in Gandhara at the time of the Saka-Yuezhi rule, when these countries were connected with the Parthian empire and the "Hellenized East." They represent groups of men, warriors of high status, and kings and/ or princes, performing rituals of drinking, fighting or taking part in a religious ceremony, a procession leading to an altar with a fire burning on it, and two men engaged in a ritual."

- ^ أ ب Nehru, Lolita (14 December 2020). "KHALCHAYAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica Online (in الإنجليزية). Brill.

About "Khalchayan", "site of a settlement and palace of the nomad Yuezhi": "Representations of figures with faces closely akin to those of the ruling clan at Khalchayan (PLATE I) have been found in recent times on woollen fragments recovered from a nomad burial site near Lake Baikal in Siberia, Noin Ula, supplementing an earlier discovery at the same site), the pieces dating from the time of Yuezhi/Kushan control of Bactria. Similar faces appeared on woollen fragments found recently in a nomad burial in south-eastern Xinjiang (Sampula), of about the same date, manufactured probably in Bactria, as were probably also the examples from Noin Ula."

- ^ Yatsenko, Sergey A. (2012). "Yuezhi on Bactrian Embroidery from Textiles Found at Noyon uul, Mongolia" (PDF). The Silk Road. 10.

- ^ أ ب Polosmak, Natalia V. (2012). "History Embroidered in Wool". SCIENCE First Hand (in الإنجليزية). 31 (N1).

- ^ أ ب Polosmak, Natalia V. (2010). "We Drank Soma, We Became Immortal…". SCIENCE First Hand (in الإنجليزية). 26 (N2).

- ^ أ ب ت ث Watson 1993, p. 234.

- ^ Hulsewé, A.F.P. and Loewe, M.A.N. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage: 125 B.C.-A.D. 23: An Annotated Translation of Chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. Leiden. E. J. Birll. 1979. ISBN 90-04-05884-2, pp. 119–120.

- ^ أ ب Hansen 2012, p. 72.

- ^ Bopearachchi 2007, p. 45.

- ^ Wink, André (1997). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The Slavic Kings and the Islamic conquest, 11th–13th centuries. Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 90-04-10236-1.

- ^ Dean, Riaz (2022). The Stone Tower: Ptolemy, the Silk Road, and a 2,000-Year-Old Riddle (in English). Delhi: Penguin Viking. pp. 73-81 (Ch.7, Migration of the Yuezhi). ISBN 978-0670093625.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Narain 1990, pp. 152–155 "[W]e must identify them [Tocharians] with the Yueh-chih of the Chinese sources... [C]onsensus of scholarly opinion identifies the Yueh-chih with the Tokharians... [T]he Indo-European ethnic origin of the Yuehchih = Tokharians is generally accepted... Yueh-chih = Tokharian people... Yueh-chih = Tokharians..."

- ^ Roux 1997, p. 90 "They are, by almost unanimous opinion, Indo-Europeans, probably the most oriental of those who occupied the steppes."

- ^ أ ب ت ث Mallory & Mair 2000, pp. 283–284.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Thierry 2005.

- ^ "Les Saces", Iaroslav Lebedynsky, ISBN 2-87772-337-2, p. 59

- ^ Liu Jianguo (2004). Distinguishing and Correcting the pre-Qin Forged Classics. Xi'an: Shaanxi People's Press. ISBN 7-224-05725-8. pp. 115–127

- ^ Liu 2001a, p. 265.

- ^ Benjamin 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Liu 2010, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Liu 2001a, p. 273.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Bunker, Emma C. (2002). Nomadic Art of the Eastern Eurasian Steppes: The Eugene V. Thaw and Other Notable New York Collections (in English). Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 24–25.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Bunker, Emma C. (2002). Nomadic Art of the Eastern Eurasian Steppes: The Eugene V. Thaw and Other Notable New York Collections (in English). Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 120–121, item 92.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Bunker, Emma C. (2002). Nomadic Art of the Eastern Eurasian Steppes: The Eugene V. Thaw and Other Notable New York Collections (in English). Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 45, item 7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Bunker, Emma C. (2002). Nomadic Art of the Eastern Eurasian Steppes: The Eugene V. Thaw and Other Notable New York Collections (in English). Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 122, item 94.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Aydemir 2019.

- ^ Aydemir 2019 "based on various toponymic evidence, *Arki and *Yarki seem to be the oldest reconstructable forms. However, it is for the time being not quite clear which one is the primary form. In order to know this, we first need to know the etymology of the name. Without doing so, it would be difficult to determine the primary form. This, however, must be left to the specialists in Indo-European linguistics."

- ^ Loewe, Michael A.N. (1979). "Introduction". In Hulsewé, Anthony François Paulus (ed.). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage: 125 BC – AD 23; an Annotated Translation of Chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. Brill. pp. 1–70. ISBN 978-90-04-05884-2. pp. 23–24.

- ^ أ ب ت H. W. Bailey, Indo-Scythian Studies: Being Khotanese Texts (vol. 7). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 6–7, 16, 101, 116, 121, 133.

- ^ أ ب Liu 2001a, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Enoki, Koshelenko & Haidary 1994, pp. 169–172.

- ^ Yatsenko, Sergey A. (2012). "Yuezhi on Bactrian Embroidery from Textiles Found at Noyon uul, Mongolia" (PDF). The Silk Road. 10.

- ^ أ ب Francfort, Henri-Paul (1 January 2020). "Sur quelques vestiges et indices nouveaux de l'hellénisme dans les arts entre la Bactriane et le Gandhāra (130 av. J.-C.-100 apr. J.-C. environ)". Journal des Savants (in الإنجليزية): 26–27, Fig.8.

- ^ Mallory & Mair 2000, p. 94.

- ^ أ ب ت Benjamin, Craig (October 2003). "The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia". Transoxiana Webfestschrift. Transoxiana. 1 (Ēran ud Anērān). Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Beckwith 2009, pp. 380–383.

- ^ Zuev, Yu. A. (2002). Early Türks: Essays on History and Ideology. Almaty. p. 15.

...Maodun proudly informed emperor Han: . . . Due to the favor of the Sky, the commanders and soldiers were in sound condition, and the horses were strong, which allowed me to destroy Uechji, who were exterminated or surrendered.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Beckwith 2009, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Enoki, Koshelenko & Haidary 1994, p. 170.

- ^ Chavannes (1907) "Les pays d'occident d'après le Heou Han chou". T'oung pao, ser.2:8, p. 189, n. 1

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Silk Road, North China, C. Michael Hogan, The Megalithic Portal, A. Burnham, ed.

- ^ Watson 1993, pp. 233–236.

- ^ Watson 1993, p. 245.

- ^ Enoki, Koshelenko & Haidary 1994, p. 175.

- ^ Watson 1993, p. 235.

- ^ Narain 1990, p. 158.

- ^ Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India (in الإنجليزية). Northern Book Centre. ISBN 978-81-7211-028-4.

- ^ Hill (2004), pp. 29, 318–350

- ^ KHALCHAYAN – Encyclopaedia Iranica. p. Figure 1.

- ^ Rowland, Benjamin (1971). "Graeco-Bactrian Art and Gandhāra: Khalchayan and the Gandhāra Bodhisattvas". Archives of Asian Art. 25: 29–35. ISSN 0066-6637. JSTOR 20111029.

- ^ Frantz, Grenet (2022). Splendeurs des oasis d'Ouzbékistan. Paris: Louvre Editions. p. 56. ISBN 978-8412527858.

- ^ Narain 1990, p. 159.

- ^ Hill 2009, pp. 28–29.

- ^ 後百餘歲,貴霜翕候丘就卻攻滅四翕候,自立為王,國號貴霜王。侵安息,取高附地。又滅濮達、罽賓,悉有其國。丘就卻年八十餘死,子閻膏珍代為王。復滅天竺,置將一人監領之。月氏自此之後,最為富盛,諸國稱之皆曰貴霜王。漢本其故號,言大月氏云。Hanshu, 96

- ^ Yu Taishan (2nd Edition 2003). A Comprehensive History of Western Regions. Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Guji Press. ISBN 7-5348-1266-6

- ^ أ ب Notes to Section 13, The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu, trans. John Hill.

- ^ Yatsenko, Sergey A. (2012). "Yuezhi on Bactrian Embroidery from Textiles Found at Noyon uul, Mongolia" (PDF). The Silk Road. 10.

- ^ Betts, Alison; Vicziany, Marika; Jia, Peter Weiming; Castro, Angelo Andrea Di (19 December 2019). The Cultures of Ancient Xinjiang, Western China: Crossroads of the Silk Roads (in الإنجليزية). Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-78969-407-9.

- ^ Yatsenko, Sergey A. (2012). "Yuezhi on Bactrian Embroidery from Textiles Found at Noyon uul, Mongolia" (PDF). The Silk Road. 10.

- ^ Yatsenko, Sergey A. (2012). "Yuezhi on Bactrian Embroidery from Textiles Found at Noyon uul, Mongolia" (PDF). The Silk Road. 10.

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press, New York. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ^ Runion, Meredith L. (2007). The history of Afghanistan. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-313-33798-7.

The Yuezhi people conquered Bactria in the second century BC, and divided the country into five chiefdoms, one of which would become the Kushan Empire. Recognizing the importance of unification, these five tribes combined under the one dominate Kushan tribe, and the primary rulers descended from the Yuezhi.

- ^ أ ب Liu 2001b, p. 156.

- ^ أ ب ت Krause, Todd B.; Slocum, Jonathan. "Tocharian Online: Series Introduction". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ Bernard 1994, p. 100.

- ^ أ ب ت Enoki, Koshelenko & Haidary 1994, p. 174.

- ^ Strabo, 11-8-1.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

This would seem to prove that the Yueh-chih of Chinese history – if they correspond, as supposed, to the Tokharoi of Greek history – were from that time established in Bactria, a country of which they later made a 'Tokharistan'.

- ^ Narain 1990, p. 161.

- ^ Yatsenko, Sergey A. (2012). "Yuezhi on Bactrian Embroidery from Textiles Found at Noyon uul, Mongolia" (PDF). The Silk Road. 10.

- ^ أ ب Srinivasan, Doris (30 April 2007). On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World (in الإنجليزية). BRILL. p. 16. ISBN 978-90-474-2049-1.

- ^ Runion, Meredith L. (2007). The history of Afghanistan. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-313-33798-7.

The Yuezhi people conquered Bactria in the second century BC and divided the country into five chiefdoms, one of which would become the Kushan Empire. Recognizing the importance of unification, these five tribes combined under the one dominate Kushan tribe, and the primary rulers descended from the Yuezhi.

- ^ Beckwith 2009, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Hill 2009, pp. 14, 43.

- ^ Rong, Xinjiang (2004). Translated by Zhou, Xiuqin. "Land route or sea route? Commentary on the study of the paths of transmission and areas in which Buddhism was disseminated during the Han period" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 144: 26–27.

- ^ Mark J. Dresden (1981), "Introductory Note," in Guitty Azarpay, Sogdian Painting: the Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, p. 5, ISBN 0-520-03765-0.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Central Asian and Sassanian Rule, ca. 150 B.C.-700 A.D." United States: Library of Congress Country Studies. 1997. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- ^ Romane, Julian (2018). Rise of the Tang Dynasty: The Reunification of China and the Military Response to the Steppe Nomads (AD 581-626) (in الإنجليزية). Pen and Sword. p. 237-238. ISBN 978-1-4738-8779-4.

- ^ Sophia-Karin Psarras, Han Material Culture, New York, Cambridge University Press, pp. 31, 297.

- ^ Haloun, Gustav (1949). "The Liang-chou rebellion 184–221 A.D." (PDF). Asia Major. New Series. 1 (1): 119–132.

- ^ Haw, Stephen G. (2006). Beijing – A Concise History (in الإنجليزية). Routledge. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-134-15033-5.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set (in الإنجليزية). Bloomsbury Publishing. p. RA1-352. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ Ouyang Xiu & Xin Wudai Shi, 1974,New Annals of the Five Dynasties, Beijing, Zhonghua Publishing House, p. 918 – cited by: Eurasian History, 2008–09, The Yuezhi and Dunhuang (月氏与敦煌) (18 March 2017).

- ^ Yatsenko, Sergey A. (2012). "Yuezhi on Bactrian Embroidery from Textiles Found at Noyon uul, Mongolia" (PDF). The Silk Road. 10: 45–46.

- ^ Francfort, Henri-Paul (1 January 2020). "Sur quelques vestiges et indices nouveaux de l'hellénisme dans les arts entre la Bactriane et le Gandhāra (130 av. J.-C.-100 apr. J.-C. environ)". Journal des Savants (in الإنجليزية): 26–27, Fig.9.

- ^ أ ب Mallory & Mair 2000, pp. 98–99, 281–283.

- ^ Mallory & Mair 2000, p. 318.

- ^ Jhutti, Sundeep S. (2003). "The Getes" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 127: 15–17.

- ^ Henning, W.B. (1978) "The first Indo-Europeans in history"

- ^ Balfour, Edward (1885). The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial Industrial, and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures (in الإنجليزية). Bernard Quaritch.

- ^ Jhutti 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Kim, Hyun Jin (2013-04-18). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-107-06722-6.

- ^ Enoki, Koshelenko & Haidary 1994, p. 171.

- ^ أ ب Manko Namba Walter (October 1998). "Tokharian Buddhism in Kucha: Buddhism of Indo-European Centum Speakers in Chinese Turkestan before the 10th Century C.E" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers (85).

- ^ أ ب "Introduction to Tocharian". lrc.la.utexas.edu.

- ^ Adams, Douglas Q. (1988). Tocharian Historical Phonology and Morphology. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-0-940490-71-0.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 590.

- ^ Narain 1990, p. 153.

- ^ Beckwith 2009, p. 5, footnote 16, as well as pp. 380–383 in appendix B, but also see Hitch 2010, p. 655: "He equates the Tokharians with the Yuezhi, and the Wusun with the Asvins, as if these are established facts, and refers to his arguments in appendix B. But these identifications remain controversial, rather than established, for most scholars."

Works cited

- Aydemir, Hakan (2019). "The Reconstruction of The Name Yuezhi 月氏 / 月支". International Journal of Old Uyghur Studies (1/2): 249–282.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2994-1.

- Benjamin, Craig (2007). The Yuezhi: Origin, Migration and the Conquest of Northern Bactria. Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-52429-0.

- Bernard, P. (1994). "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia". In Harmatta, János (ed.). History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 96–126. ISBN 978-92-3-102846-5.

- Dorn'eich, Chris M. (2008). Chinese sources on the History of the Niusi-Wusi-Asi(oi)-Rishi(ka)-Arsi-Arshi-Ruzhi and their Kueishuang-Kushan Dynasty. Shiji 110/Hanshu 94A: The Xiongnu: Synopsis of Chinese original Text and several Western Translations with Extant Annotations. Berlin. To read or download go to: [1]

- Enoki, K.; Koshelenko, G.A.; Haidary, Z. (1 January 1994). "The Yu'eh-chih and their migrations". In Harmatta, János (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. D. 250 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 171–191. ISBN 978-92-3-102846-5.

{{cite book}}: Check|author-link2=value (help) - Hanks, Brian K.; Linduff, Katheryn M. (2009). Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals and Mobility. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51712-6.

- Hansen, Valerie (2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2006). Beijing – A Concise History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-15032-8.

- Hill, John E. (2003). The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation

- ——— (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries AD. Charleston SC: BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hitch, Doug (2010). "Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present" (PDF). Journal of the American Oriental Society. 130 (4): 654–658. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-26. Retrieved 2015-01-02.

- Liu, Xinru (2001a). "Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan. Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies". Journal of World History. 12 (2): 261–292. doi:10.1353/jwh.2001.0034. JSTOR 20078910. S2CID 162211306.

- ——— (2001b). "The Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Interactions in Eurasia". In Adas, Michael (ed.). Agricultural and pastoral societies in ancient and classical history. Philadelphia PA: Temple University Press. pp. 151–179. ISBN 978-1-56639-832-9.

- ——— (2010). The Silk Road in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516174-8.

- Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1999). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- ———; ——— (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929668-2.

- Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05101-6.

- Narain, A. K. (1990). "Indo-Europeans in Central Asia". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–177. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521243049.007. ISBN 978-1-139-05489-8.

- Ricket, W.A. (1998). Guanzi: Political, Economic, and Philosophic Essays from Early China, vol. 2. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Roux, Jean-Paul (1997). L'Asie Centrale, Histoire et Civilization [Central Asia: History and Civilization] (in الفرنسية). Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-59894-9.

- Thierry, François (2005). "Yuezhi et Kouchans, Pièges et dangers des sources chinoises". In Bopearachchi, Osmund; Boussac, Marie-Françoise (eds.). Afghanistan, Ancien carrefour entre l'est et l'ouest. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 421–539. ISBN 978-2-503-51681-3.

- Watson, Burton (1993). Records of the Grand Historian of China: Han Dynasty II (revised ed.). ISBN 978-0-231-08166-5. ISBN 978-0-231-08167-2 (pbk.) Translated from the Shiji of Sima Qian

- West, Barbara A. (January 1, 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- Yap, Joseph P. (2009). Wars With The Xiongnu, A Translation From Zizhi tongjian Chapters 2 & 4, AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4

- Zürcher, E. (1969). "The Yüeh-chih and Kanișka in the Chinese sources". In Basham, Arthur Llewellyn (ed.). Papers on the Date of Kaniṣka. Brill. pp. 346–390. ISBN 978-90-04-00151-0.

External links

- "Section 13 – The Kingdom of the Da Yuezhi", The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu, trans. John Hill

- Notes to Section 13 – Linguistic analysis of the connection between Yuezhi and Kushan

Eliot, Charles Norton Edgcumbe (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 28 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 944–945.

Eliot, Charles Norton Edgcumbe (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 28 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 944–945. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)- Mongolia: Xiongnu and Yuezhi – Overview of Xiongnu history and their wars with the Yuezhi

- "The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia", by Craig Benjamin.

- "After Alexander: Central Asia Before Islam" – nomad migration in Central Asia, by Kasim Abdullaev

- "India and China: beyond and the within", Lokesh Chandra

- Guanzi – online text from National Sun Yat-sen University

- "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age", Li et al. BMC Biology 2010, 8:15.

قالب:Rulers of Ancient Central Asia قالب:Historical Non-Chinese peoples in China

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Articles using infobox ethnic group with image parameters

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Pages using template Zh with sup tags

- All articles that may contain original research

- Articles that may contain original research from August 2008

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2019

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2007

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Yuezhi

- Ancient history of Afghanistan

- Ancient peoples of China

- Ancient peoples of Pakistan

- بلدان سابقة في التاريخ الصيني

- Historical Iranian peoples

- History of India

- History of Kyrgyzstan

- History of Tajikistan

- History of Uzbekistan

- Indo-European peoples

- Iranian nomads

- Kushan Empire

- جماعات بدوية في أوراسيا

![Nomadic figure, typically with a long nose, on a Bactrian camel. Southern Ningxia, 4th century BC.[25][24]](/w/images/thumb/d/dc/MET_2002_201_83_O1.jpg/150px-MET_2002_201_83_O1.jpg)

![Harness ornament in the shape of a coiled wolf, characteristic of nomadic artifacts of southern Ningxia and southeastern Gansu, 5th-4th century BC.[26][24]](/w/images/thumb/f/fa/%E7%8B%BC%E7%B4%8B%E9%9D%92%E9%8A%85%E8%BB%8A%E9%A6%AC%E9%A3%BE-Harness_Ornament_in_the_Shape_of_a_Coiled_Wolf_MET_2002_201_61.jpg/125px-%E7%8B%BC%E7%B4%8B%E9%9D%92%E9%8A%85%E8%BB%8A%E9%A6%AC%E9%A3%BE-Harness_Ornament_in_the_Shape_of_a_Coiled_Wolf_MET_2002_201_61.jpg)

![Belt plaque in the shape of a standing wolf, characteristic of nomadic artifacts of southern Ningxia and southeastern Gansu, and related to the Scythian styles of Pazyryk. 4th century BC.[27][24]](/w/images/thumb/d/d4/%E7%8B%BC%E7%B4%8B%E9%9D%92%E9%8A%85%E5%B8%B6%E9%A3%BE-Belt_Plaque_in_the_Shape_of_a_Standing_Wolf_MET_DT5398.jpg/150px-%E7%8B%BC%E7%B4%8B%E9%9D%92%E9%8A%85%E5%B8%B6%E9%A3%BE-Belt_Plaque_in_the_Shape_of_a_Standing_Wolf_MET_DT5398.jpg)