شيونج نو

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

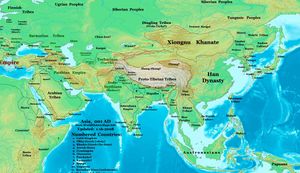

شيونج نو أو شيونگنو (Chinese: 匈奴; Wade–Giles: Hsiung-nu؛ إنگليزية: Xiongnu) كانوا اتحاداً[6] من الشعوب البدوية، التي، تبعأً للمراجع الصينية القديمة، كانت تسكن السهوب الآسيوية من القرن الثالث ق.م. حتى أواخر القرن الأول الميلادي. أفادت المراجع الصينية أن مودو تشانيو، القائد الأعلى بعد عام 209 ق.م. أسس امبراطورية شيونگنو.[7]

بعد سادتهم السابقين، هاجر اليوىژي إلى آسيا الوسطى في القرن الثاني ق.م، وأصبح شيونگنو القوة المسيطرة على سهوب شمال-شرق آسيا الوسطى، حيث كانوا متمركزين في المنطقة التي عرفت لاحقاً بمنغوليا. كما كان شيونگنو نشطين في المناطق التي تشكل حالياً جزء من سيبريا، منغوليا الداخلية، گانسو، وشينجيانگ. علاقاتهم مع الأسر الصينية المجاورة إلى الجنوب الشرقي كانت معقدة، مع فترات متكررة من النزاع والمؤامرات، بالتناوب مع تغيرات الجزية، التجارة، ومعاهدات الزواج.

محاولات التعرف على الشيونگنو مع الجماعات اللاحقة في غرب السهوب الآسيوية لا تزال محل جدل. في نفس الوقت، كان السكوذيون، السرمتيون موجودين غرباً. هوية البؤرة العرقية للشيونگنو كانت موضوع فرضيات مختلفة، حيث لا تحتفظ المراجع الصينية إلا ببضعة كلمات، وخاصة الألقاب والأسماء الشخصية. اسم شيونگنو قد يكون لفظ قريب لتسمية الهان و/أو الهون،[8] بالرغم من أن هذا محل نزاع.[9][10] روابط لسانية أخرى – جميعها أيضاً مثيرة للجدل- ومقترحة من قبل علماء من بينهم إيرانيين[11][12][13] منغوليين،[14] تورك،[15][16] أوراليين،[17] ينيسـِيْ،[9][18] أو متعددو العرقية.[19]

التاريخ

السلف البدوي

| جزء من سلسلة عن | ||||||||||||||

| تاريخ منغوليا | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| الفترة القديمة | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| العصور الوسطى | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| الفترة المعاصرة | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| موضوعات | ||||||||||||||

الأراضي المقترنة بالشيونگنو في وسط/شرق منغوليا كانت مسكونة في السابق بـ ثقافة البلاطة-المقبرة، التي استمرت حتى القرن الثالث ق.م..[21] تشير الأبحاث الجينية إلى أن شعب ثقافة البلاطة-المقبرة كانوا الأسلاف الأساسيين للشيونگنو، وأن الشيونگنو تشكلوا من خلال اختلاط كبير ومعقد مع غرب أوراسيا.[22]

وإلى الغرب، ثقافة پازيريك (القرون السادس للثالث ق.م.) سبقت مباشرة تشكل الشيونگنو.[23] وكانت ثقافة سكوذية،[24] تم التعرف عليها من خلال القطع الأثرية المكتشَفة والبشر المحنطين ، مثل أميرة الجليد السيبيري، التي عـُثر عليها في أرض دائمة التجلد في سيبيريا، في جبال ألطاي وقزاقستان ومنغوليا القريبة.[25] وإلى الجنوب، ثقافة أردس تطورت في هضبة أوردوس (منغوليا الداخلية الحالية، الصين) أثناء العصر البرونزي ومطلع العصر الحديدي من القرن السادس إلى الثاني ق.م.، وهي من أصل عرقي لغوي غير معروف، ويُعتقد أنها تمثل الامتداد الشرقي للناطقين بالهندو-أوروبية.[26][27][28] اليوىژي حل محلهم توسع الشيونگنو في القرن الثاني ق.م.، واضطروا إلى الهجرة إلى وسط وجنوب آسيا.[29][30]

- قبائل شيونگنو

التاريخ المبكر

|

فارس بدوي يقتل خنزيراًٍ برمح، اِكتـُشِف في ساكسانوخور، جنوب طاجيكستان، القرن الأول أو الثاني الميلادي.[32][33] وحسب فرانكفورت، فإن مشبك الحزام المزخرف هذا ربما صـُنِع لزبون على صلة بالشيونگنو، وربما يعود إلى القرن الثاني أو الأول ق.م. الفارس يرتدي زي السهوب، وشعره ملفوف على شكل كعكة وهي إحدى سمات السهوب الشرقية، وحصانه مزين على النمط المميز للشيونگنو.[34] |

من أولى الإشارات للشيونگنو ما كتبه سيما تشيان مؤرخ أسرة هان عن الشيونگنو في سجلات المؤرخ العظيم (م. 100 ق.م.)، الذي رسم خطاً مميزاً بين شعب الهواشيا (الصيني) و(الشيونگنو) البدو الرعاة، حيث وصفهمها بأنهما مجموعتين قطبيتين بالمعنى الحضاري مقابل المجتمع الغير متحضر: تميز هوا-يي.[35] مراجع ما قبل الهان عادة ما تصنف الشيونگنو ضمن شعب الهو، الذي كان يعتبر مصطلحاً شاملاً للشعوب البدوية بصفة عامة؛ ولم يصبح اسماً عرقياً للشيونگنو سوى في فترة الهان.[36] Sima Qian also mentioned Xiongnu's early appearance north of Wild Goose Gate and Dai commanderies before 265 BCE, just before the Zhao-Xiongnu War;[37][38] however, sinologist Edwin Pulleyblank (1994) contends that pre-241-BCE references to the Xiongnu are anachronistic substitutions for the Hu people instead.[39][40] Sometimes the Xiongnu were distinguished from other nomadic peoples; namely, the Hu people;[41] yet on other occasions, Chinese sources often just classified the Xiongnu as a Hu people, which was a blanket term for nomadic people.[39][42] Even Sima Qian is inconsistent in his Historical Records: occasionally, he considered the Donghu to be the Hu proper,[43][44] yet elsewhere he considered Xiongnu to be also Hu.[45][39]

Ancient China often came in contact with the Xianyun and the Xirong nomadic peoples. In later Chinese historiography, some groups of these peoples were believed to be the possible progenitors of the Xiongnu people.[46] These nomadic people often had repeated military confrontations with the Shang and especially the Zhou, who often conquered and enslaved the nomads in an expansion drift.[46] During the Warring States period, the armies from the Qin, Zhao and Yan states were encroaching and conquering various nomadic territories that were inhabited by the Xiongnu and other Hu peoples.[47] The Zhao–Xiongnu War is a notable example of these campaigns.

Pulleyblank argued that the Xiongnu were part of a Xirong group called Yiqu, who had lived in Shaanbei and had been influenced by China for centuries, before they were driven out by the Qin dynasty.[48][49] Qin's campaign against the Xiongnu expanded Qin's territory at the expense of the Xiongnu.[50] After the unification of Qin dynasty, Xiongnu was a threat to the northern board of Qin. They were likely to attack the Qin dynasty when they suffered natural disasters.[51]

تشكل الدولة

دبلوماسية الزواج مع صين الهان

في شتاء عام 200 ق.م، في أعقاب حصار تاييوان، قاد امبراطور گوازو من الهان بنفسه حملة عسكرية ضد مودون. في معركة بايدنگ، وقع الامبراطور في كمين نصبه 300.000 من خيرة فرسان شيونگنو. وقُطع عنه الإمدادات والتعزيزات لسبعة أيام، ليفلت بالكاد من الأسر.

أرسل الهان الأميرات للزواج من قادة الشيونگنو ضمن جهودهم لإيقاف الغارات الحدودية. بالإضافة إلى الزيجات المرتبة، أرسل الهان الهدايا لرشوة الشيونگنو من أجل إيقاف الهجوم.[54] بعد الهزيمة في بايدنگ تخلى امبراطور الهان عن الحل العسكري لتهديد الشيونگنو. بدلاً من ذلك، عام 198 ق.م.، أسند لأحد رجال حاشيته ليو جينگ مهمة التفاوض. وفي النهاية تم التوصل لمعاهدة سلام بين الطرفين تضمنت زواج احدى أميرات الهان لـتشانيو (يطلق عليها هىتشين Chinese: 和親; lit. 'القرابة المتناغمة')؛ الهدايا الدورية من الحرير، المشروبات المقطرة، والأرز تُمنح للشيونگنو ضمنت الوضع المتساوي بين الدولتين؛ وحافظت على السور العظيم كحد بينهما.

وضعت المعاهدة الأولى تلك نمطاً للعلاقات بين الهان والشيونگنو لستة سنوات. حتى عام 135 ق.م.، تم تجديد المعاهدة تسعة مرات، وفي كل مرة كان هناك زيادة في "الهدايا". عام 192 ق.م، طلب مودون يد أرملة امبراطور گاو، الامبراطورة لو ژي. ابنه وخليفته، جييو النشيط، الذي كان يعرف بلاوشانگ تشانيو، واصل سياسات والده التوسعية. نجح لاوشانگ في التفاوض مع الامبرطور ون من أجل الحفاظ على نظام سوق واسع النطاق برعاية الحكومة.

While the Xiongnu benefited handsomely, from the Chinese perspective marriage treaties were costly, very humiliating and ineffective. Laoshang Chanyu showed that he did not take the peace treaty seriously. On one occasion his scouts penetrated to a point near Chang'an. In 166 BC he personally led 140,000 cavalry to invade Anding, reaching as far as the imperial retreat at Yong. In 158 BC, his successor sent 30,000 cavalry to attack Shangdang and another 30,000 to Yunzhong.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The Xiongnu also practiced marriage alliances with Han dynasty officers and officials who defected to their side by marrying off sisters and daughters of the Chanyu (the Xiongnu ruler) to Han Chinese who joined the Xiongnu and Xiongnu in Han service. The daughter of the Laoshang Chanyu (and older sister of Junchen Chanyu and Yizhixie Chanyu) was married to the Xiongnu General Zhao Xin, the Marquis of Xi who was serving the Han dynasty. The daughter of Qiedihou Chanyu was married to the Han Chinese General Li Ling after he surrendered and defected.[60][61][62][63][64] Another Han Chinese General who defected to the Xiongnu was Li Guangli, general in the War of the Heavenly Horses, who also married a daughter of the Hulugu Chanyu.[65] The Han Chinese diplomat Su Wu married a Xiongnu woman given by Li Ling when he was arrested and taken captive.[66] Han Chinese explorer Zhang Qian married a Xiongnu woman and had a child with her when he was taken captive by the Xiongnu.[67][68][69][70][71][72][73]

When the Eastern Jin dynasty ended, the Xianbei Northern Wei received the Han Chinese Jin prince Sima Chuzhi 司馬楚之 as a refugee. A Northern Wei Xianbei Princess married Sima Chuzhi, giving birth to Sima Jinlong 司馬金龍. Northern Liang Xiongnu King Juqu Mujian's daughter married Sima Jinlong.[74]

The Yenisei Kyrgyz khagans of the Yenisei Kyrgyz Khaganate claimed descent from the Chinese general Li Ling, grandson of the famous Han dynasty general Li Guang.[75][76][77][78] Li Ling was captured by the Xiongnu and defected in the first century BCE.[79][80] And since the Tang royal Li family also claimed descent from Li Guang, the Kirghiz Khagan was therefore recognized as a member of the Tang Imperial family. This relationship soothed the relationship when Kyrgyz khagan Are (阿熱) invaded Uyghur Khaganate and put Qasar Qaghan to the sword. The news brought to Chang'an by Kyrgyz ambassador Zhuwu Hesu (註吾合素).

الحرب مع أسرة هان

Han dynasty made preparations for war when the Han Emperor Wu dispatched the Han Chinese explorer Zhang Qian to explore the mysterious kingdoms to the west and to form an alliance with the Yuezhi people in order to combat the Xiongnu. During this time Zhang married a Xiongnu wife, who bore him a son, and gained the trust of the Xiongnu leader.[67][81][82][70][71][83][73] While Zhang Qian did not succeed in this mission,[84] his reports of the west provided even greater incentive to counter the Xiongnu hold on westward routes out of the Han Empire, and the Han prepared to mount a large scale attack using the Northern Silk Road to move men and material.

علاقة الجزية مع الهان

في 53 ق.م. قرر هوهانيى (呼韓邪) أن يدخل في علاقة جزية مع صين الهان.[86] البنود الأصلية التي أصر عليها بلاط الهان كانت، أولاً، التشانيو أو ممثلوه لابد أن يأتوا إلى العاصمة لتقديم التبجيل والولاي؛ ثانياً، على التشانيو أن يرسل أميراً رهينة؛ ثالثاً، على التشانيو دفع الجزية لإمبراطور الهان. الوضع السياسي للشيونجنو في النظام العالمي الصيني انخفض من "دولة شقيقة" إلى "تابع خارجي" (外臣). إلا أنه في تلك الفترة، حافظ الشيونجنو على سيادتهم ووحدة ترابهم. واصل سور الصين العظيم كونه خط الحدود بين الهان والشيونگنو.[بحاجة لمصدر]

أرسل هوهانيى ابنه، "ملك الميمنة الحكيم" شولوجوتانگ، إلى بلاط الهان كرهينة. في 51 ق.م. قام شخصياً بزيارة تشانج آن لتقديم فروض الطاعة والولاء للإمبراطور بمناسبة رأس السنة القمرية. في نفس العام، تم استقبال مبعوث آخر چيجوشان (稽居狦) في قصر گانچوان في شمال غرب شانشي الحالية.[87] وعلى الجانب المالي، كوفئ هوهانيى بكميات كبيرة من الذهب والنقود والملابس والحرير والخيول والحبوب لمشاركته. وقد قام هوهانيى برحلتين أخريين لتقديم الطاعة، في 49 ق.م. و 33 ق.م.؛ مع كل واحدة زادت العطايا الإمبراطورية. وفي الرحلة الأخيرة، انتهز هوهانيى الفرصة ليطلب السماح له ليصبح صهراً إمبراطورياً. كعلامة على انحدار الوضع السياسي للشيونگنو، رفض الإمبراطور يوان، معطياً إياه بدلاً من ذلك خمس وصيفات. إحداهن كانت وانگ ژاوجون، الشهيرة في الفلكلور الصيني بأنها واحدة من الجميلات الأربع.

حين علم ژيژي بخضوع شقيقه، أرسل هو أيضاً ابناً إلى بلاط الهان كرهينة في 53 ق.م.. ثم أرسل مرتين، في 51 ق.م. و 50 ق.م.، مبعوثين إلى بلاط الهان مع الجزية. ولكنه لم يقم شخصياً بتقديم فروض الطاعة والولاء، لذلك لم يتم ضمه إلى نظام الجزية. في 36 ق.م. قام ضابط صغير يُدعى تشن تانگ، بمساعدة من گان يانشو، الحامي العام للمناطق الغربية، بجمع قوة التجريدة التي هزمته في معركة ژيژي وأرسل رأسه هدية إلى چانگآن.

توقفت علاقات الجزية أثناء حكم هودوإرشي (18 م–48)، المتزامنة مع قلاقل سياسية في أسرة شين. انتهز الشيونگنو الفرصة لاستعادة السيطرة على المناطق الغربية، وكذلك الشعوب المجاورة مثل ووهوان. وفي 24 م، بلغ الأمو أن تكلم هودوإرشي عن عكس نظام الجزية.

شيونگنو الشمالية والجنوبية

- امبراطورية شيونگنو تنفصم إلى شيونگنو الشمالية (في ما هو اليوم منغوليا الخارجية) و"شيونگنو الجنوبية" (في ما هو اليوم منغوليا الداخلية).

- اتحاد من ثمان قبائل من الشيونگنو في معقل بي في الجنوب، بقوة عسكرية تبلغ 40,000 إلى 50,000 مقاتل، تنفصل عن مملكة پونو وتنادي بـ "بي" خانيو. المملكة أصبحت تُعرف بإسم شيونگنو الجنوبية.

- امبراطور الصين، الامبراطور گوانگوو من هان، يستعيد السيطرة الصينية على منغوليا الداخلية. شيونگنو الجنوبية يُجعلوا اتحادات لحماية الحدود الشمالية للامبراطورية.

شيونگنو الجنوبية

النظريات حول الهوية العرقو-لغوية

| نُطق 匈 المصدر: http://starling.rinet.ru | |

|---|---|

| الصينية القديمة قبل الكلاسيكية: | sŋoŋ |

| الصينية القديمة الكلاسيكية: | [ŋ̊oŋ] |

| الصينية القديمة بعد الكلاسيكية: | hoŋ |

| الصينية المتوسطة: | xöuŋ |

| المندرينية الحديثة: | [ɕjʊ́ŋ] |

هناك العديد من النظريات حول الهوية العرقية اللغوية للشيونجنو.

صوت الحرف الصيني الأول (匈) أُعيد بناؤه بالحرف /qʰoŋ/ في الصينية القديمة.[88] الاسم الصيني شيونگنو كان مصطلح ازدرائي في حد ذاته، حيث كانت الحروف تعني "العبد الشرس".[89] تُنطق الحروف الصينية Xiōngnú [ɕjʊ́ŋnǔ] بالمندرينية الحديثة.

صلة مقترحة بالهون

الصوت الصيني القديم المفترض للحرف الأول (匈) يحتمل تشابهه مع اسم "الهون" في اللغات الأوروپية. ويبدو أن الحرف الثاني (奴) ليسه له حرفاً موازياً في التسمية الغربية. من الصعب معرفة ما إذا كان التشابه هو دليل على القرابة أو مجرد مصادفة. قد يمنح المصداقية للنظرية أن الهون كانوا في الواقع أحفاد للشيونگنو الشماليين الذين هاجروا غرباً، أو أن الهون كانوا يستخدمون اسماً مقترضاً من الشيونگنو الشماليين، أو أن هؤلاء الشيونگنو كانوا يشكلون جزءاً من كونفدرالية الهون.

النظريات الإيرانية

النظريات المنغولية

النظريات التوركية

نظريات الينيسـِيْ

العرقيات المتعددة

نظريات العزلة اللغوية

رفض عالم التوركيات گرهارد دورفر أي احتمال لوجود علاقة بين لغة الشيونگنو وأي لغة أخرى معروفة ورفض بشدة أي علاقة بين اللغات التوركية والمنغولية.[99]

الآثار والجينات

الجينات

خلصت دراسة اعتمدت على تحليل دنا المتقدرة للرفات البشرية المدفونة في وادي نهر إگ بمنغوليا إلى أن الشعوب التوركية يرجع أصلها إلى نفس المنطقة ومن ثم فهناك رابطة محتملة.[101]

معظم تسلسلات دنا المتقدرة للشيونگنو (89%) يمكن تصنيفه على أنه ينتمي للمجموعات الفردانية الآسيوية، وما يقارب من 11% ينتمي للمجموعات الفردانية الأوروپية. كان لبداية ثقافة الشيونگنو السبق بين السكان الأوروپيين والآسيويين، مما يؤكد النتائج الواردة عن عينتين من السكان السيكوتيين-السيبيريين واللتان ترجعان إلى أوائل القرن الثالث ق.م. (كليسون وزملائه، 2000).

الثقافة

حروف لنقش شيانبـِيْ-هان من القرن الثاني-الثالث ق.م. (منغوليا الخارجية والداخلية)، ن. إشجامتس، "البدو في شرق آسيا الوسطى"، في تاريخ حضارات آسيا الوسطى، الجزء 2، شكل 5، ص. 166؛ منشورات اليونسكو، 1996، ISBN 92-3-102846-4

حروف لنقش شيانبـِيْ-هان من القرن الثاني ق.م - القرن الثاني الميلادي (منغوليا الخارجية والداخلية)، ن. إشجامتس، "البدو في شرق آسيا الوسطى"، في تاريخ حضارات آسيا الوسطى، الجزء 2، شكل 5، ص. 166؛ منشورات اليونسكو، 1996، ISBN 92-3-102846-4

الدين والغذاء

حسب كتاب الهان، "دعا الشيونگنو السماء (天) 'تشنگلي'، (撐犁) [102] وهي نسخ لفظي صيني للتنگري. كان الشيونگنو شعباً بدوياً. من خلال أسلوب حياتهم المتمثل في رعي قطعان الغنم وتجارة الخيول مع الصين، يمكن أن نستنتج أن نظامهم الغذائي يتكون أساسًا من لحم الضأن ولحوم الخيول والأوز البري الذي كانوا يصطادونه بالسهام.

التجارة الخارجية

في 2022، وجد مجموعة من علماء الآثار العاملين في مقاطعة خوڤد، بمنغوليا، أن "مقابر النخبة الأرستقراطية كانت مخصصة للنساء"، حسب وارينر، التي عددت الأغراض الرمزية المدفونة معهن. — مشبك حزام حديدي مذهب، لجام حصان، عربة، شمس وقمر للزينة. ثم تقول “أعتقد أن ما نراه هو أنه بينما كانت جيوش محاربي الشيونگنو تخرج وتوسع الإمبراطورية ، كانت نساء النخبة يحكمن الحدود.”

أضافت وارينر أن هؤلاء النساء الأرستقراطيات أظهرن كمجموعة أدنى تنوع جيني ، مما يشير إلى أن القوة كانت مركزة في سلالات معينة. أما بالنسبة للخدم المدفونين حولهم ، فقد تبين أنهم مجموعة متنوعة للغاية من الذكور ، تضم مجموعات من أبعد مناطق الإمبراطورية وما بعدها.

ولوحظ نمط مختلف في مدافن النخب ذات المستوى الأدنى. هناك ، يبدو أن الزيجات الاستراتيجية قد استخدمت لتوطيد الروابط مع المجموعات المدمجة حديثًا. مجتمعة ، تشير أنماط الأصل الوراثي والقرابة على طول المجتمعات الحدودية إلى الوسائل المختلفة التي نما بها Xiongnu إمبراطوريتهم متعددة الأعراق. قال وارينر: "اقترح البعض أن إمبراطورية شيونغنو كانت مكونة من عدد كبير من العشائر التي كانت هي نفسها متجانسة إلى حد ما". "وجدنا أن هذا ليس صحيحًا. إنهم متنوعون وراثيًا حتى داخل مجتمع واحد ".

أكملت أدلة الحمض النووي أيضًا الاكتشاف الأثري بطرق مؤثرة. تم دفن الأولاد في سن المراهقة بأقواس تشبه الألعاب والسهام. تم دفن امرأة مع رضيعها في الفترة المحيطة بالولادة، وكلاهما من ضحايا الولادة على ما يبدو. وحول عنق الأم، كانت هناك خرزة من الخزف تصور الإله المصري بس، حامي الأطفال.[103]

انظر أيضاً

- قائمة حكام شيونگنو (التشانيو)

- شجرة عائلة الحكام

- الامبراطورية البدوية

- الجماعات العرقية في التاريخ الصيني

- تاريخ أسرة هان

- بان يونگ

- زوبو

ملاحظات

الهامش

الحواشي

- ^ Coatsworth, John; Cole, Juan; Hanagan, Michael P.; Perdue, Peter C.; Tilly, Charles; Tilly, Louise (16 March 2015). Global Connections: Volume 1, To 1500: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-316-29777-3.

- ^ Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0.

- ^ Fauve, Jeroen (2021). The European Handbook of Central Asian Studies. p. 403. ISBN 978-3-8382-1518-1.

- ^ Zheng Zhang (Chinese: 鄭張), Shang-fang (Chinese: 尚芳). "匈 - 字 - 上古音系 - 韻典網". 韻典網. Rearranged by BYVoid.

- ^ Zheng Zhang (Chinese: 鄭張), Shang-fang (Chinese: 尚芳). "奴 - 字 - 上古音系 - 韻典網". 韻典網. Rearranged by BYVoid.

- ^ "Xiongnu People". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ di Cosmo 2004: 186

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 19, 26–27. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ أ ب Beckwith 2009, pp. 51–52, 404–405

- ^ Vaissière 2006

- ^ Harmatta 1994, p. 488: "Their royal tribes and kings (shan-yii) bore Iranian names and all the Hsiung-nu words noted by the Chinese can be explained from an Iranian language of Saka type. It is therefore clear that the majority of Hsiung-nu tribes spoke an Eastern Iranian language."

- ^ Bailey 1985, pp. 21–45

- ^ Jankowski 2006, pp. 26–27

- ^ Tumen D., "Anthropology of Archaeological Populations from Northeast Asia [1] page 25, 27

- ^ Hucker 1975: 136

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^ Di Cosmo, 2004, pg 166

- ^ Adas 2001: 88

- ^ Geng 2005

- ^ Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Rohland, Nadin; Bernardos, Rebecca (6 September 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457). doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- ^ Khenzykhenova, Fedora I.; Kradin, Nikolai N.; Danukalova, Guzel A.; Shchetnikov, Alexander A.; Osipova, Eugenia M.; Matveev, Arkady N.; Yuriev, Anatoly L.; Namzalova, Oyuna D. -Ts; Prokopets, Stanislav D.; Lyashchevskaya, Marina A.; Schepina, Natalia A.; Namsaraeva, Solonga B.; Martynovich, Nikolai V. (30 April 2020). "The human environment of the Xiongnu Ivolga Fortress (West Trans-Baikal area, Russia): Initial data". Quaternary International (in الإنجليزية). 546: 216–228. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2019.09.041. ISSN 1040-6182. S2CID 210787385. "The slab graves culture existed in this territory prior to the Xiongnu empire. Sites of this culture dating back to approximately 1100-400/300 BC are common in Mongolia and the Trans-Baikal area. The earliest calibrated dates are prior to 1500 BC (Miyamoto et al., 2016). Later dates are usually 100–200 years earlier than the Xiongnu culture. Therefore, it is customarily considered that the slab grave culture preceded the Xiongnu culture. There is only one case, reported by Miyamoto et al. (2016), in which the date of the slab grave corresponds to the time of the making of the Xiongnu Empire."

- ^ Rogers & Kaestle 2022

- ^ Linduff, Katheryn M.; Rubinson, Karen S. (2021). Pazyryk Culture Up in the Altai. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-429-85153-7.

The rise of the confederation of the Xiongnu, in addition, clearly affected this region as it did most regions of the Altai

- ^ "Pazyryk | archaeological site, Kazakhstan". Britannica.com. 2001-09-11. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- ^ State Hermitage Museum 2007

- ^ Whitehouse 2016, p. 369: "From that time until the HAN dynasty the Ordos steppe was the home of semi-nomadic Indo-European peoples whose culture can be regarded as an eastern province of a vast Eurasian continuum of Scytho-Siberian cultures."

- ^ Harmatta 1992, p. 348: "From the first millennium b.c., we have abundant historical, archaeological and linguistic sources for the location of the territory inhabited by the Iranian peoples. In this period the territory of the northern Iranians, they being equestrian nomads, extended over the whole zone of the steppes and the wooded steppes and even the semi-deserts from the Great Hungarian Plain to the Ordos in northern China."

- ^ Unterländer, Martina; Palstra, Friso; Lazaridis, Iosif; Pilipenko, Aleksandr; Hofmanová, Zuzana; Groß, Melanie; Sell, Christian; Blöcher, Jens; Kirsanow, Karola; Rohland, Nadin; Rieger, Benjamin (2017-03-03). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. 8: 14615. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814615U. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537.

- ^ Benjamin, Craig (29 March 2017). "The Yuezhi". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.49. ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7.

- ^ Bang, Peter Fibiger; Bayly, C. A.; Scheidel, Walter (2 December 2020). The Oxford World History of Empire: Volume Two: The History of Empires. Oxford University Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-19-753278-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ Toh 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Marshak, Boris Ilʹich (1 January 2002). Peerless Images: Persian Painting and Its Sources (in الإنجليزية). Yale University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-300-09038-3.

- ^ Ilyasov, Jangar. "A Study on the Bone Plates from Orlat // Silk Road Art and Archaeology. Vol. 5. Kamakura, 1997/98, 107-159": 127.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Francfort, Henri-Paul (2020). "Sur quelques vestiges et indices nouveaux de l'hellénisme dans les arts entre la Bactriane et le Gandhāra (130 av. J.-C.-100 apr. J.-C. environ)" [On some vestiges and new indications of Hellenism in the arts between Bactria and Gandhāra (130 BC-100 AD approximately)]. Journal des Savants: 35–39.

Page 36: "A renowned openwork gold plate found on the surface of the site depicts a wild boar hunt at the spear by a rider in steppe dress, in a frame of ovals arranged in cells intended to receive inlays (fig. 14). We can today attribute it to a local craft whose intention was to satisfy a horserider patron originating from the distant steppes and related to the Xiongnu" (French: "On peut aujourd'hui l'attribuer à un art local dont l'intention était de satisfaire un patron cavalier originaire des steppes lointaines et apparenté aux Xiongnu.")

Page 36: "We can also clearly distinguish the crupper adorned with three rings forming a chain, as well as, on the shoulder of the mount, a very recognizable clip-shaped pendant, suspended from a chain passing in front of the chest and going up to the pommel of the saddle, whose known parallels are not to be found among the Scythians but in the realm of the Xiongnu, on bronze plaques from Mongolia and China" (French: "les parallèles connus ne se trouvent pas chez les Scythes mais dans le domaine des Xiongnu").

Page 38: "The hairstyle of the hunter, with long hair pulled back and gathered in a bun, is also found at Takht-i Sangin; it is that of the eastern steppes, which can be seen on the wild boar hunting plaque "des Iyrques" (fig. 15)" (French: La coiffure du chasseur, aux longs cheveux tirés en arrière et rassemblés en chignon, se retrouve à Takht-i Sangin; C'est celle des steppes orientales, que l'on remarque sur les plaques de la chasse au sanglier «des Iyrques» (fig. 15)) - ^ Di Cosmo 2002, 2.

- ^ Di Cosmo 2002, 129.

- ^ Shiji Vol. 81 "Stories about Lian Po and Lin Xiangru - Addendum: Li Mu" text: "李牧者,趙之北邊良將也。常居代鴈門,備匈奴。" translation: "About Li Mu, he was a good general at Zhao's northern borders. He often stationed at Dai and Wild Goose Gate, prepared [against] the Xiongnu."

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich (2019) "Li Mu 李牧" in ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

- ^ أ ب ت Pulleyblank 1994, p. 518-520.

- ^ Schuessler 2014, p. 264.

- ^ Bunker 2002, pp. 27-28.

- ^ Di Cosmo 2002, p. 129.

- ^ Shiji, "Hereditary House of Zhao" quote: "今中山在我腹心,北有燕,東有胡,西有林胡、樓煩、秦、韓之邊,而無彊兵之救,是亡社稷,柰何?" translation: "(King Wuling of Zhao to Lou Huan:) Now Zhongshan is at our heart and belly [note: Zhao surrounded Zhongshan, except on Zhongshan's north-eastern side], Yan to the north, Hu to the east, Forest Hu, Loufan, Qin, Han at our borders to the west. Yet we have no strong army to help us, surely we will lose our country. What is to be done?"

- ^ Compare a parallel passage in Stratagems of the Warring States, "King Wuling spends his day in idleness", quote: "自常山以至代、上黨,東有燕、東胡之境,西有樓煩、秦、韓之邊,而無騎射之備。" Jennifer Dodgson's translation: "From Mount Chang to Dai and Shangdang, our lands border Yan and the Donghu in the east, and to the west we have the Loufan and shared borders with Qin and Han. Nevertheless, we have no mounted archers ready for action."

- ^ Shiji, Vol. 110 "Account of the Xiongnu". quote: "後秦滅六國,而始皇帝使蒙恬將十萬之眾北擊胡,悉收河南地。…… 匈奴單于曰頭曼,頭曼不勝秦,北徙。" translation: "Later on, Qin conquered the six other states, and the First Emperor dispatched general Meng Tian to lead a multitude of 100,000 north to attack the Hu; and he took all lands south the Yellow River. [...] The Xiongnu chanyu was Touman; Touman could not win against Qin, so [they] fled north."

- ^ أ ب Di Cosmo 2002, p. 107.

- ^ Di Cosmo 1999, pp. 892–893.

- ^ Pulleyblank 1994, p. 514-523.

- ^ Pulleyblank 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Di Cosmo 1999, pp. 892–893 & 964.

- ^ Rawson, Jessica (2017). "China and the steppe: reception and resistance". Antiquity. 91 (356): 375–388. doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.276. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 165092308.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ Bunker 2002, p. 137 item 109.

- ^ Bently, Jerry H., Old World Encounters, 1993, pg. 36

- ^ Moorey, P. R. S. (Peter Roger Stuart); Markoe, Glenn (1981). Ancient bronzes, ceramics, and seals: The Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection of ancient Near Eastern, central Asiatic, and European art, gift of the Ahmanson Foundation. Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. p. 168, item 887. ISBN 978-0-87587-100-4.

- ^ "Belt Buckle LACMA Collections". collections.lacma.org.

- ^ أ ب Prior, Daniel (2016). "FASTENING THE BUCKLE: A STRAND OF XIONGNU-ERA NARRATIVE IN A RECENT KIRGHIZ EPIC POEM" (PDF). The Silk Road. 14: 191.

- ^ So, Jenny F.; Bunker, Emma C. (1995). Traders and raiders on China's northern frontier. Seattle : Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, in association with University of Washington Press. pp. 22 & 90. ISBN 978-0-295-97473-6.

- ^ Francfort, Henri-Paul (2020). "Sur quelques vestiges et indices nouveaux de l'hellénisme dans les arts entre la Bactriane et le Gandhāra (130 av. J.-C.-100 apr. J.-C. environ)". Journal des Savants: 37, Fig.16.

"Bronze plaque from northwestern China or south central Interior Mongolia, wrestling Xiongnus, the horses have Xiongnu-type trappings" (French: "Plaque en bronze ajouré du nord-ouest de la Chine ou Mongolie intérieure méridionale centrale, Xiongnu luttant, les chevaux portent des harnachements de «type Xiongnu».")

- ^ di Cosmo, Nicola, Aristocratic elites in the Xiongnu empire, p. 31, https://www.academia.edu/5147439/Aristocratic_elites_in_the_Xiongnu_empire

- ^ Sima, Qian; Watson, Burton (January 1993). Records of the Grand Historian: Han dynasty. Renditions-Columbia University Press. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-0-231-08166-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Monumenta Serica. H. Vetch. 2004. p. 81 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wakeman, Frederic E. (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sima, Qian (1993). Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty II. p. 128. ISBN 0231081677.

- ^ Lin Jianming (林剑鸣) (1992). 秦漢史 [History of Qin and Han]. Wunan Publishing. pp. 557–8. ISBN 978-957-11-0574-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hong, Yuan (2018). The Sinitic Civilization Book II: A Factual History Through the Lens of Archaeology, Bronzeware, Astronomy, Divination, Calendar and the Annals (abridged ed.). iUniversе. p. 419. ISBN 978-1532058301.

- ^ أ ب Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3. Retrieved 2011-04-17 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lovell, Julia (2007). The Great Wall: China Against the World, 1000 BC – AD 2000. Grove Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8021-4297-9. Retrieved 2011-04-17 – via Google Books.

- ^ Andrea, Alfred J.; Overfield, James H. (1998). The Human Record: To 1700. Houghton Mifflin. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-395-87087-7. Retrieved 2011-04-17 – via Google Books.

- ^ أ ب Zhang, Yiping (2005). Story of the Silk Road. China Intercontinental Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-7-5085-0832-0. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ^ أ ب Higham, Charles (2004). Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations. Infobase Publishing. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-8160-4640-9. Retrieved 2011-04-17 – via Google Books.

- ^ Indian Society for Prehistoric & Quaternary Studies (1998). Man and environment, Volume 23, Issue 1. Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies. p. 6. Retrieved 2011-04-17 – via Google Books.

- ^ أ ب Mayor, Adrienne (22 September 2014). The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press. pp. 422–. ISBN 978-1-4008-6513-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

sima.

- ^ Veronika Veit, ed. (2007). The role of women in the Altaic world: Permanent International Altaistic Conference, 44th meeting, Walberberg, 26-31 August 2001. Asiatische Forschungen. Vol. 152 (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 61. ISBN 978-3447055376. Retrieved 8 February 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ Drompp, Michael Robert (2005). Tang China and the collapse of the Uighur Empire: a documentary history. Brill's Inner Asian library. Vol. 13 (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 126. ISBN 9004141294. Retrieved 8 February 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kyzlasov, Leonid R. (2010). The Urban Civilization of Northern and Innermost Asia Historical and Archaeological Research (PDF). Curatores seriei Victor Spinei et Ionel Candeâ VII. Romanian Academy Institute of Archaeology of Iaşi Editura Academiei Romane - Editura Istros. p. 245. ISBN 978-973-27-1962-6. Florilegium magistrorum historiae archaeologiaeque Antiqutatis et Medii Aevi.

- ^ Drompp, Michael (2021). Tang China and the Collapse of the Uighur Empire: A Documentary History. Brill's Inner Asian Library. BRILL. p. 126. ISBN 978-9047414780 – via Google Books.

- ^ Veit, Veronika (2007). The role of women in the Altaic world : Permanent International Altaistic Conference, 44th meeting, Walberberg, 26-31 August 2001. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 61. ISBN 978-3-447-05537-6. OCLC 182731462.

- ^ Drompp, Michael R. (1999). "Breaking the Orkhon Tradition: Kirghiz Adherence to the Yenisei Region after A. D. 840". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (3): 394–395. doi:10.2307/605932. JSTOR 605932.

- ^ Lovell, Julia (2007). The Great Wall: China Against the World, 1000 BC – AD 2000. Grove Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8021-4297-9. Retrieved 2011-04-17 – via Google Books.

- ^ Andrea, Alfred J.; Overfield, James H. (1998). The Human Record: To 1700. Houghton Mifflin. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-395-87087-7. Retrieved 2011-04-17 – via Google Books.

- ^ Indian Society for Prehistoric & Quaternary Studies (1998). Man and environment, Volume 23, Issue 1. Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies. p. 6. Retrieved 2011-04-17 – via Google Books.

- ^ Grousset 1970, p. 34.

- ^ Psarras, Sophia-Karin (2 February 2015). Han Material Culture: An Archaeological Analysis and Vessel Typology. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-316-27267-1.

- ^ Grousset 1970, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Fairbank & Têng 1941.

- ^ Baxter-Sagart (2014).

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةyuuu86-384 - ^ Betts, Alison; Vicziany, Marika; Jia, Peter Weiming; Castro, Angelo Andrea Di (19 December 2019). The Cultures of Ancient Xinjiang, Western China: Crossroads of the Silk Roads. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-78969-407-9.

In Noin-Ula (Noyon Uul), Mongolia, the remarkable elite Xiongnu tombs have revealed textiles that are linked to the pictorial tradition of the Yuezhi: the decorative faces closely resemble the Khalchayan portraits, while the local ornaments have integrated elements of Graeco-Roman design. These artifacts were most probably manufactured in Bactria

- ^ Francfort, Henri-Paul (1 January 2020). "Sur quelques vestiges et indices nouveaux de l'hellénisme dans les arts entre la Bactriane et le Gandhāra (130 av. J.-C.-100 apr. J.-C. environ)" [On some vestiges and new indications of Hellenism in the arts between Bactria and Gandhāra (130 BC-100 AD approximately)]. Journal des Savants (in الفرنسية): 26–27, Fig.8 "Portrait royal diadémé Yuezhi" ("Diademed royal portrait of a Yuezhi").

- ^ Polos'mak, Natalia V.; Francfort, Henri-Paul; Tsepova, Olga (2015). "Nouvelles découvertes de tentures polychromes brodées du début de notre ère dans les "tumuli" n o 20 et n o 31 de Noin-Ula (République de Mongolie)". Arts Asiatiques. 70: 3–32. doi:10.3406/arasi.2015.1881. ISSN 0004-3958. JSTOR 26358181.

Considered as Yuezhi-Saka or simply Yuezhi, and p.3: "These tapestries were apparently manufactured in Bactria or in Gandhara at the time of the Saka-Yuezhi rule, when these countries were connected with the Parthian empire and the "Hellenized East." They represent groups of men, warriors of high status, and kings and/ or princes, performing rituals of drinking, fighting or taking part in a religious ceremony, a procession leading to an altar with a fire burning on it, and two men engaged in a ritual."

- ^ Nehru, Lolita (14 December 2020). "KHALCHAYAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. Brill.

About "Khalchayan", "site of a settlement and palace of the nomad Yuezhi": "Representations of figures with faces closely akin to those of the ruling clan at Khalchayan (PLATE I) have been found in recent times on woollen fragments recovered from a nomad burial site near Lake Baikal in Siberia, Noin Ula, supplementing an earlier discovery at the same site), the pieces dating from the time of Yuezhi/Kushan control of Bactria. Similar faces appeared on woollen fragments found recently in a nomad burial in south-eastern Xinjiang (Sampula), of about the same date, manufactured probably in Bactria, as were probably also the examples from Noin Ula."

- ^ Bunker 2002, p. 29.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ "Belt Buckle LACMA Collections". collections.lacma.org.

- ^ Bunker 2002, p. 30, item 81.

- ^ Bunker 2002, p. 111, item 81.

- ^ Di Cosmo 2004: 164

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, pp. 369–375

- ^ Genome News Network 2003

- ^ Book of Han, Vol. 94-I, 匈奴謂天為「撐犁」,謂子為「孤塗」,單于者,廣大之貌也.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Christy DeSmith (2023-04-28). "DNA shows poorly understood empire was multiethnic with strong female leadership". ذا هارڤرد گازِت.

المصادر

- مصادر رئيسية

- Ban Gu et al., Book of Han, esp. vol. 94, part 1, part 2.

- Fan Ye et al., Book of the Later Han, esp. vol. 89.

- Sima Qian et al., Records of the Grand Historian, esp. vol. 110.

- أعمال مرجعية

- Adas, Michael. 2001. Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History, American Historical Association/Temple University Press.

- Bailey, Harold W. (1985). Indo-Scythian Studies: being Khotanese Texts, VII. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (Reviewed here) - Barfield, Thomas. 1989. The Perilous Frontier. Basil Blackwell.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691135894. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Brosseder, Ursula, and Bryan Miller. Xiongnu Archaeology: Multidisciplinary Perspectives of the First Steppe Empire in Inner Asia. Bonn: Freiburger Graphische Betriebe- Freiburg, 2011.

- Csányi, B. et al. 2008. Y-Chromosome Analysis of Ancient Hungarian and Two Modern Hungarian-Speaking Populations from the Carpathian Basin. Annals of Human Genetics, 2008 March 27, 72(4): 519-534.

- Demattè, Paola. 2006. Writing the Landscape: Petroglyphs of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia Province (China). In: Beyond the steppe and the sown: proceedings of the 2002 University of Chicago Conference on Eurasian Archaeology, edited by David L. Peterson et al. Brill. Colloquia Pontica: series on the archaeology and ancient history of the Black Sea area; 13. 300-313. (Proceedings of the First International Conference of Eurasian Archaeology, University of Chicago, May 3–4, 2002.)

- Davydova, Anthonina. The Ivolga archaeological complex. Part 1. The Ivolga fortress. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 1. St Petersburg, 1995.

- Davydova, Anthonina. The Ivolga archaeological complex. Part 2. The Ivolga cemetery. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 2. St Petersburg, 1996.

- (بالروسية) Davydova, Anthonina & Minyaev Sergey. The complex of archaeological sites near Dureny village. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 5. St Petersburg, 2003.

- Davydova, Anthonina & Minyaev Sergey. The Xiongnu Decorative bronzes. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 6. St Petersburg, 2003.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola. 1999. The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China. In: The Cambridge History of Ancient China, edited by Michael Loewe and Edward Shaughnessy. Cambridge University Press.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola. 2004. Ancient China and its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge University Press. (First paperback edition; original edition 2002)

- J.K., Fairbank; Têng, S.Y. (1941). On the Ch'ing Tributary System. Vol. 6. pp. 135–246. doi:10.2307/2718006.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - (صينية) Geng, Shi-min [耿世民]. 2005. 阿尔泰共同语、匈奴语探讨 ("On Altaic Common Language and Xiongnu Language"). 《语言与翻译(汉文版)》(Language and Translation), 2005年 第02期. Ürümqi. ISSN 1001-0823. WorldCat id=123501525. Database citation page for this article

- Genome News Network. 2003 July 25. "Ancient DNA Tells Tales from the Grave"

- Grousset, René. 1970. The empire of the steppes: a history of central Asia. Rutgers University Press.

- (بالروسية) Gumilev L. N. 1961. История народа Хунну (History of the Hunnu people).

- Hall, Mark & Minyaev, Sergey. Chemical Analyses of Xiong-nu Pottery: A Preliminary Study of Exchange and Trade on the Inner Asian Steppes. In: Journal of Archaeological Science (2002) 29, pp. 135–144

- Harmatta, János (1 January 1994). "Conclusion". In Harmatta, János (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. D. 250. UNESCO. pp. 485–492. ISBN 9231028464. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - (مجرية) Helimski, Eugen. "A szamojéd népek vázlatos története" (Short History of the Samoyedic peoples). In: The History of the Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic Peoples. 2000, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary.

- Henning W. B. 1948. The date of the Sogdian ancient letters. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (BSOAS), 12(3-4): 601–615.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1. (Especially pp. 69–74)

- Hucker, Charles O. 1975. China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2353-2

- N. Ishjamts. 1999. Nomads In Eastern Central Asia. In: History of civilizations of Central Asia. Volume 2: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 bc to ad 250; Edited by Janos Harmatta et al. UNESCO. ISBN 92-3-102846-4. 151-170.

- Jankowski, Henryk (2006). Historical-Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Russian Habitation Names of the Crimea. Handbuch der Orientalistik [HdO], 8: Central Asia; 15. Brill. ISBN 90-04-15433-7.

{{cite book}}: Check|author-link=value (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - (بالروسية) Kradin N.N., "Hun Empire". Acad. 2nd ed., updated and added., Moscow: Logos, 2002, ISBN 5-94010-124-0

- Kradin, Nikolay. 2005. Social and Economic Structure of the Xiongnu of the Trans-Baikal Region. Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia, No 1 (21), p. 79–86.

- Kradin, Nikolay. 2012. New Approaches and Challenges for the Xiongnu Studies. In: Xiongnu and its eastward Neighbours. Seoul, p. 35–51.

- (بالروسية) Kiuner (Kjuner, Küner) [Кюнер], N.V. 1961. Китайские известия о народах Южной Сибири, Центральной Азии и Дальнего Востока (Chinese reports about peoples of Southern Siberia, Central Asia, and Far East). Moscow.

- (بالروسية) Klyashtorny S.G. [Кляшторный С.Г.]. 1964. Древнетюркские рунические памятники как источник по истории Средней Азии. (Ancient Türkic runiform monuments as a source for the history of Central Asia). Moscow: Nauka.

- (بالألمانية) Liu Mau-tsai. 1958. Die chinesischen Nachrichten zur Geschichte der Ost-Türken (T'u-küe). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Loewe, Michael. 1974. The campaigns of Han Wu-ti. In: Chinese ways in warfare, ed. Frank A. Kierman, Jr., and John K. Fairbank. Harvard Univ. Press.

- Maenschen-Helfen, Otto (1973). The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture. University of California Press. ISBN 0520015967. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Minyaev, Sergey. On the origin of the Xiongnu // Bulletin of International association for the study of the culture of Central Asia, UNESCO. Moscow, 1985, No. 9.

- Minyaev, Sergey. News of Xiongnu Archaeology // Das Altertum, vol. 35. Berlin, 1989.

- Miniaev, Sergey. "Niche Grave Burials of the Xiong-nu Period in Central Asia", Information Bulletin, Inter-national Association for the Cultures of Central Asia 17(1990): 91-99.

- Minyaev, Sergey. The excavation of Xiongnu Sites in the Buryatia Republic// Orientations, vol. 26, n. 10, Hong Kong, November 1995.

- Minyaev, Sergey. Les Xiongnu// Dossiers d' archaeologie, # 212. Paris 1996.

- Minyaev, Sergey. Archaeologie des Xiongnu en Russie: nouvelles decouvertes et quelques Problemes. In: Arts Asiatiques, tome 51, Paris, 1996.

- Minyaev, Sergey. The origins of the "Geometric Style" in Hsiungnu art // BAR International series 890. London, 2000.

- Minyaev, Sergey. Art and archeology of the Xiongnu: new discoveries in Russia. In: Circle of Iner Asia Art, Newsletter, Issue 14, December 2001, pp. 3–9

- Minyaev, Sergey & Smolarsky Phillipe. Art of the Steppes. Brussels, Foundation Richard Liu, 2002.

- (بالروسية) Minyaev, Sergey. Derestuj cemetery. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 3. St-Petersburg, 1998.

- Miniaev, Sergey & Sakharovskaja, Lidya. Investigation of a Xiongnu Royal Tomb in the Tsaraam valley, part 1. In: Newsletters of the Silk Road Foundation, vol. 4, no.1, 2006.

- Miniaev, Sergey & Sakharovskaja, Lidya. Investigation of a Xiongnu Royal Tomb in the Tsaraam valley, part 2. In: Newsletters of the Silk Road Foundation, vol. 5, no.1, 2007.

- (بالروسية) Minyaev, Sergey. The Xiongnu cultural complex: location and chronology. In: Ancient and Middle Age History of Eastern Asia. Vladivostok, 2001, pp. 295–305.

- Miniaev, Sergey & Elikhina, Julia. On the chronology of the Noyon Uul barrows. The Silk Road 7 (2009: 21-30).

- (مجرية) Obrusánszky, Borbála. 2006 October 10. Huns in China (Hunok Kínában) 3.

- (مجرية) Obrusánszky, Borbála. 2009. Tongwancheng, city of the southern Huns. Transoxiana, August 2009, 14. ISSN 1666-7050.

- (بالفرنسية) Petkovski, Elizabet. 2006. Polymorphismes ponctuels de séquence et identification génétique: étude par spectrométrie de masse MALDI-TOF. Strasbourg: Université Louis Pasteur. Dissertation

- (بالروسية) Potapov L.P. [Потапов, Л. П.] 1969. Этнический состав и происхождение алтайцев (Etnicheskii sostav i proiskhozhdenie altaitsev, Ethnic composition and origins of the Altaians). Leningrad: Nauka. Facsimile in Microsoft Word format.

- (بالألمانية) Pritsak O. 1959. XUN Der Volksname der Hsiung-nu. Central Asiatic Journal, 5: 27-34.

- Psarras, Sophia-Karin. "HAN AND XIONGNU: A REEXAMINATION OF CULTURAL AND POLITICAL RELATIONS (I)." Monumenta Serica. 51. (2003): 55-236. Web. 12 Dec. 2012. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/40727370>.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity" (PDF). Early China (25).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sims-Williams, Nicholas. 2004. The Sogdian ancient letters. Letters 1, 2, 3, and 5 translated into English.

- (بالروسية) Talko-Gryntsevich, Julian. Paleo-Ethnology of Trans-Baikal area. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 4. St Petersburg, 1999.

- Taskin V.S. [Таскин В.С.]. 1984. Материалы по истории древних кочевых народов группы Дунху (Materials on the history of the ancient nomadic peoples of the Dunhu group). Moscow.

- Toh, Hoong Teik (2005). "The -yu Ending in Xiongnu, Xianbei, and Gaoju Onomastica" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 146.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - (بالفرنسية) Vaissière (2005). "Huns et Xiongnu". Central Asiatic Journal. 49 (1): 3–26.

- Vaissière, Étienne de la. 2006. Xiongnu. Encyclopædia Iranica online.

- Vovin, Alexander (2000). "Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language?". Central Asiatic Journal. 44 (1): 87–104.

- Wink, A. 2002. Al-Hind: making of the Indo-Islamic World. Brill. ISBN 0-391-04174-6

- Yap, Joseph P. (2009). "Wars with the Xiongnu: A translation from Zizhi tongjian". AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4

- (صينية) Zhang, Bibo, and Dong, Guoyao [张碧波, 董国尧], eds. 2001. 中国古代北方民族文化史 (Zhongguo Gudai Beifang Minzu Wenhuashi = Cultural History of Ancient Northern Ethnic Groups in China). Harbin: Heilongjiang People's Press. ISBN 7-207-03325-7

قراءات إضافية

- (بالروسية) Потапов, Л. П. 1966. Этнионим Теле и Алтайцы. Тюркологический сборник, 1966: 233-240. Moscow: Nauka. (Potapov L.P., The ethnonym "Tele" and the Altaians. Turcologica 1966: 233-240).

- Houle, J. and L.G. Broderick 2011 "Settlement Patterns and Domestic Economy of the Xiongnu in Khanui Valley, Mongolia[dead link]", 137-152. In Xiongnu Archaeology: Multidisciplinary Perspectives of the First Steppe Empire in Inner Asia.

وصلات خارجية

- "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age" (PDF). BMC Biology. 8: 15. 2010. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-27.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Material Culture presented by University of Washington

- Encyclopedic Archive on Xiongnu

- The Xiongnu Empire

- The Silk Road Volume 4 Number 1

- The Silk Road Volume 9

- Gold Headdress from Aluchaideng

- Belt buckle, Xiongnu type, 3rd–2nd century B.C.

- Videodocumentation: Xiongnu – the burial site of the Hun prince (Mongolia)

- The National Museum of Mongolian History :: Xiongnu

- CS1 uses الصينية-language script (zh)

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles containing منغولية-language text

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2014

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2019

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- Articles with Hungarian-language external links

- Articles with dead external links from July 2016

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI

- شيونگنو

- تاريخ منغوليا

- تاريخ الصين

- جماعات بدوية في أوراسيا

- شعوب قديمة في الصين

- بدو السهوب الأوراسية

- دول وأراضي تأسست في القرن الثالث ق.م.

- دول وأراضي انحلت في القرن الأول

- تأسيسات القرن الثالث ق.م.

- انحلالات 460