الشعوب الأناضولية

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| المواضيع الهندو-أوروپية |

|---|

|

The Anatolians were Indo-European-speaking peoples of the Anatolian Peninsula in present-day Turkey, identified by their use of the Anatolian languages.[1] These peoples were among the oldest Indo-European ethnolinguistic groups and one of the most archaic, because Anatolians were among the first Indo-European peoples to separate from the Proto-Indo-European community that gave origin to the individual Indo-European peoples.[2][1]

التاريخ

Origins

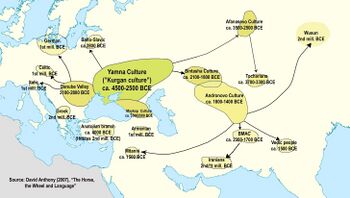

Together with the Proto-Tocharians, who migrated eastward, the Anatolian peoples constituted the first known waves of Indo-European emigrants out of the Eurasian steppe.[3] They likely reached Anatolia from the north, via the Balkans or the Caucasus, in the 3rd millennium BC.[1][4][5] This movement has yet to be documented archaeologically.[5][6] Although they had wagons, they probably emigrated before Indo-Europeans had learned to use chariots for war.[3][7] Comparison of Hittite agricultural terms with those of other Indo-European subgroups indicates that the Anatolian peoples seceded from the other Indo-Europeans before the establishment of a common agricultural nomenclature, which suggests that they entered the Near East as a cohesive people through a common route.[5]

The Anatolian peoples were intruders in an area in which the local population had already founded cities, established literate bureaucracies and established kingdoms and palace cults.[2] Once they entered the region, the cultures of the local populations, in particular the Hattians, significantly influenced them linguistically, politically and religiously.[5] Christopher I. Beckwith suggests that the Anatolian peoples initially gained a foothold in Anatolia after being hired by the Hattians to fight other invading Indo-European groups.[6]

Bronze Age

The earliest linguistic and historical attestation of the Anatolian peoples are names mentioned in Assyrian mercantile texts from the 19th Century BC at Kanesh.[6][8] Kanesh was at the time the center of a network of Assyrian merchants overseeing trade between Assyria and the warring states of Anatolia. This certainly increased the power of the Anatolian peoples who inhabited the city.[2]

The Hittites are by far the best known of the Anatolian peoples. Originally referring to themselves as the Neshites after their capital at Kanesh, which they had at one point captured from the Hatti, the Hittites then seized the Hattic capital of Hattusa. The Hittite language thereafter gradually supplanted Hattic as the predominant language in Anatolia.[1] Uniting several independent Hattic kingdoms in Anatolia the Hittites began establishing a Middle Eastern empire in the 17th-century BC.[2] They sacked Babylon, seized Assyrian cities and fought the Egyptian Empire to a standstill at the Battle of Kadesh, the greatest chariot battle of the ancient world.[2] Their empire disappeared with the Late Bronze Age collapse in the 12th-century BC. As Hittite was a language of the elite, the language disappeared with the empire.[2]

Another Anatolian group was the Luwians, who migrated to south-west Anatolia in the early Bronze Age.[9] Unlike Hittite, the Luwian language does not contain loanwords from Hattic, indicating that it was initially spoken in western Anatolia.[2] The Luwians inhabited a large area and their language was spoken after the collapse of the Hittite Empire.[2]

The least known Anatolian group were the Palaic peoples, who inhabited the region of Pala in northern Anatolia.[9] This area had probably also previously been inhabited by the Hatti. It is likely that Palaic peoples disappeared with the invasion of the Kaskians in the 15th-century BC.[10]

Iron Age

Following the Bronze Age collapse, a number of Neo-Hittite petty kingdoms survived until about the 8th century BC. Later in the Iron Age, Anatolian languages were spoken by the Lycians, Lydians, Carians, Pisidians and others. These languages were mostly extinct in the Hellenistic period, by the 3rd century BC, although late survival of some remnants is possible, the Isaurian language may have survived into the Late Antiquity, with funerary inscriptions recorded for as late as the 5th century AD.

Culture

Law

The better known laws of the Anatolian peoples were the Hittite laws that were formulated as case laws. These laws were organized in groups according to their subject (in eight main groups). Hittite laws show an aversion to the death penalty, the usual penalty for serious offenses being enslavement to forced labour, however in some cases of serious offenses death penalty was applied.

See also

- List of ancient Anatolian peoples

- List of ancient peoples of Anatolia

- Ancient Regions of Anatolia

- Mitanni

- Purushanda

- Hyksos

- Sea peoples

- Maryannu

- Kikkuli

References

Citations

- ^ أ ب ت ث Mallory 1997, pp. 12–16

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Anthony 2007, pp. 43–48

- ^ أ ب Beckwith 2009, p. 32

- ^ Hock & Joseph 1996, pp. 520–521

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Anatolian languages". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت Beckwith 2009, pp. 37–39

- ^ Anthony 2007, pp. 64–65

- ^ Fortson, IV 2011, p. 48

- ^ أ ب "Anatolia: The rise and fall of the Hittites". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Ramat, Anna Giacalone; Ramat, Paolo (2015). The Indo-European Languages. Routledge. p. 172. ISBN 978-1134921874.

The Palaic peoples were very quickly overwhelmed by the invasions of the Kaskas, a non-IE people from the East, who swept them away and for centuries kept attacking the Hittite kingdom

Sources

- Anthony, David (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2994-1. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Fortson, IV, Benjamin W. (2011). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5968-8. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Hock, Hans Heinrich; Joseph, Brian Daniel (1996). Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship: An Introduction to Historical and Comparative Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-1101-4784-X. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Mallory, J. P. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Douglas Q. Adams. ISBN 1884964982. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- Melchert, H. Craig (2012). "The Position of Anatolian" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-09.

- Sharon R. Steadman; Gregory McMahon (15 September 2011). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000–323 BCE). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

Further reading

- Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (August 2022). "The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe". Science. 377 (6609). doi:10.1126/science.abm4247.