مالطا

| جمهورية مالطا Repubblika ta' Malta (مالطية) | |

|---|---|

Motto: Virtute et constantia "بقوة وثبات" | |

![موقع مالطا (الدائرة الخضراء) – on the European continent (الأخضر الخفيف & الرمادي الداكن) – in الاتحاد الأوروپي (الأخضر الخفيف) — [Legend]](/w/images/thumb/6/63/EU-Malta.svg/350px-EU-Malta.svg.png) موقع مالطا (الدائرة الخضراء) – on the European continent (الأخضر الخفيف & الرمادي الداكن) | |

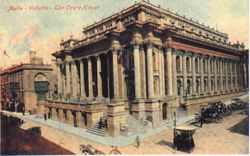

| العاصمة | ڤاليتا 35°54′N 14°31′E / 35.900°N 14.517°E |

| أكبر بلدة | بير كركرة |

| اللغات الرسمية | المالطية،[d] الإنگليزية |

| اللغات الأخرى | الإيطالية (66% يتكلمونها)[1] |

| جماعات عرقية (2019[2]) | |

| الدين | الكاثوليكية الرومانية |

| صفة المواطن | مالطى |

| الحكم | جمهورية دستورية برلمانية أحادية |

• الرئيس | جورج ڤـِلا |

| روبرت أبـِلا | |

| Legislature | مجلس النواب |

| الاستقلال | |

• عن المملكة المتحدة | 21 سبتمبر 1964 |

• جمهورى | 13 ديسمبر 1974 |

| المساحة | |

• إجمالي | 316[3] km2 (122 sq mi) (185) |

• Water (%) | 0.001 |

| التعداد | |

• تقدير 2019 | 514,564[4] (173) |

• تعداد 2011 | 417,432[5] |

• Density | 1،633/km2 (4،229.5/sq mi) (4) |

| ن.م.إ. (PPP) | تقدير 2019 |

• الإجمالي | 22.802 مليار دولار[6] |

• للفرد | 48,246 دولار[6] |

| ن.م.إ. (اسمي) | تقدير 2019 |

• إجمالي | 15.134 مليار دولار[6] |

• للفرد | 32,021 دولار[6] |

| Gini (2019) | ▼ 28.0[7] low · 15th |

| HDI (2019) | ▲ 0.895[8] very high · 28 |

| العملة | يورو (€) (EUR) |

| منطقة التوقيت | توفيت وسط أوروپا (UTC+1) |

• الصيفي (DST) | توفيت وسط أوروپا الصيفي (UTC+2) |

| صيغة التاريخ | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| القيادة في الجانب | left |

| Calling code | +356 |

| القديس الحاميs | پولس الرسول، القديس پوبليوس وأگاثا من صقلية[9] |

| Internet TLD | .mt[c] |

الموقع الإلكتروني gov | |

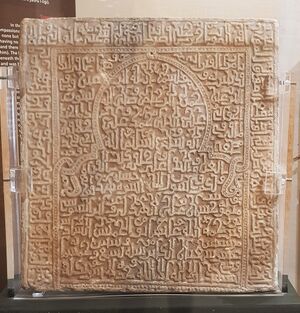

مالطا (/ˈmɒltə/,[11] /ˈmɔːltə/ (![]() استمع)؛ بالمالطية: [ˈmɐltɐ]؛ بالإيطالية: النطق بالإيطالية: [ˈmalta])، وتُعرف رسمياً بإسم جمهورية مالطا (مالطية: Repubblika ta' Malta) وسابقاً Melita، هي دولة في جنوب أوروپا، وهي بلد جزيري يتكون من أرخبيل في البحر المتوسط.[12] وتقع على بعد 80 كم جنوب إيطاليا، و 284 كم شرق تونس،[13] و 333 كم شمال ليبيا.[14] وبتعداد يناهز 515,000 نسمة[4] على مساحة 316 كم²،[3] فإن مالطا هي عاشر أصغر بلد في العالم من حيث المساحة[15][16] و رابع أكثر بلد اكتظاظاً بالسكان. وعاصمتها هي ڤالـِتـّا، التي هي أصغر عاصمة وطنية في الاتحاد الأوروپي بمساحة 0.8 كم². اللغة الرسمية والوطنية هي المالطية، التي تنحدر من العربية الصقلية التي نشأت في عهد إمارة صقلية، بينما تعمل الإنگليزية كاللغة الرسمية الثانية. كما عملت كلٌ من الإيطالية والصقلية كلغات رسمية وثقافية في الجزيرة لقرون، مع اعتبار الإيطالية لغة رسمية في مالطا حتى 1934 وغالبية التعداد الحالي من المالطيين هم على الأقل قادرين على التكلم باللغة الإيطالية.

استمع)؛ بالمالطية: [ˈmɐltɐ]؛ بالإيطالية: النطق بالإيطالية: [ˈmalta])، وتُعرف رسمياً بإسم جمهورية مالطا (مالطية: Repubblika ta' Malta) وسابقاً Melita، هي دولة في جنوب أوروپا، وهي بلد جزيري يتكون من أرخبيل في البحر المتوسط.[12] وتقع على بعد 80 كم جنوب إيطاليا، و 284 كم شرق تونس،[13] و 333 كم شمال ليبيا.[14] وبتعداد يناهز 515,000 نسمة[4] على مساحة 316 كم²،[3] فإن مالطا هي عاشر أصغر بلد في العالم من حيث المساحة[15][16] و رابع أكثر بلد اكتظاظاً بالسكان. وعاصمتها هي ڤالـِتـّا، التي هي أصغر عاصمة وطنية في الاتحاد الأوروپي بمساحة 0.8 كم². اللغة الرسمية والوطنية هي المالطية، التي تنحدر من العربية الصقلية التي نشأت في عهد إمارة صقلية، بينما تعمل الإنگليزية كاللغة الرسمية الثانية. كما عملت كلٌ من الإيطالية والصقلية كلغات رسمية وثقافية في الجزيرة لقرون، مع اعتبار الإيطالية لغة رسمية في مالطا حتى 1934 وغالبية التعداد الحالي من المالطيين هم على الأقل قادرين على التكلم باللغة الإيطالية.

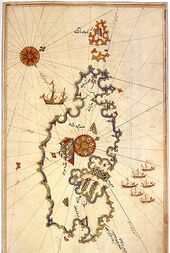

مالطا مأهولة منذ حوالي سنة 5900 ق.م.[17] موقعها في وسط البحر المتوسط[18] أعطاها تاريخياً أهمية استراتيجية كقاعدة بحرية، بتعاقب للقوى التي تنازعت على الجزر وحكـَمتها، بما في ذلك الفينيقيون والرومان واليونانيون والعرب والنورمان والأراگون وفرسان القديس يوحنا والفرنسيون والبريطانيون.[19] معظم تلك التأثيرات الأجنبية تركت أثراً على الثقافة القديمة للبلد.

أصبحت مالطا مستعمرة بريطانية في 1813، تعمل كمحطة طريق للسفن ومقر لأسطول البحر الأبيض المتوسط البريطاني. كانت محاصرة من قبل قوى المحور خلال الحرب العالمية الثانية وكانت قاعدة مهمة للحلفاء للعمليات في شمال أفريقيا والبحر المتوسط.[20][21] مرر البرلمان البريطاني قانون استقلال مالطا في 1964، مانحاً مالطا استقلالها عن المملكة المتحدة كـ"دولة مالطا"، بحيث كانت الملكة إليزابث الثانية رأس الدولة وملكتها.[22] أصبح البلد جمهورية في 1974. وأصبحت دولة عضو في كومنولث الأمم والأمم المتحدة منذ استقلالها، وانضمت إلى الاتحاد الأوروپي في 2004؛ وأصبحت جزءاً من الاتحاد النقدي يوروزون في 2008.

مالطا يقطنها مسيحيون منذ عهد المسيحية المبكرة، بالرغم من أن غالبية سكانها كانوا مسلمين حين كانت في العهد العربي، وآنئذ ساد التسامح تجاه المسيحيين. طرد الحكام النورمان جميع المسلمين الذين لم يتحولوا إلى المسيحية، وطرد حكام أراگون اليهود غير المتحولين. واليوم، فإن الكاثوليكية هي دين الدولة، لكن دستور مالطا يضمن حرية العقيدة والعبادة الدينية.[23][24]

تعد مالطا وجهة سياحية بمناخها الدافئ والعديد من المناطق الترفيهية والمعالم المعمارية والتاريخية، بما في ذلك مواقع التراث العالمي لليونسكو: مقبرة حل سفليني،[25] ڤالـِتـّا،[26] وسبع معابد جلمودية التي هي بعض أقدم المنشآت القائمة بذاتها في العالم.[27][28][29]

أصل الاسم

The origin of the name Malta is uncertain, and the modern-day variation is derived from the Maltese language. The most common etymology is that the word Malta is derived from the Greek word μέλι, meli, "honey".[30] The ancient Greeks called the island Μελίτη (Melitē) meaning "honey-sweet", possibly for Malta's unique production of honey; an endemic subspecies of bees live on the island.[31] The Romans called the island Melita,[32] which can be considered either a Latinisation of the Greek Μελίτη or the adaptation of the Doric Greek pronunciation of the same word Μελίτα.[33] In 1525 William Tyndale used the transliteration "Melite" in Acts 28:1 for Καὶ διασωθέντες τότε ἐπέγνωμεν ὅτι Μελίτη ἡ νῆσος καλεῖται as found in his translation of The New Testament that relied on Greek texts instead of Latin. "Melita" is the spelling used in the Authorized (King James) Version of 1611 and in the American Standard Version of 1901. "Malta" is widely used in more recent versions, such as The Revised Standard Version of 1946 and The New International Version of 1973.

Another conjecture suggests that the word Malta comes from the Phoenician word Maleth, "a haven",[34] or 'port'[35] in reference to Malta's many bays and coves. Few other etymological mentions appear in classical literature, with the term Malta appearing in its present form in the Antonine Itinerary (Itin. Marit. p. 518; Sil. Ital. xiv. 251).[36]

التاريخ

Malta has been inhabited from around 5900 BC,[37] since the arrival of settlers from the island of Sicily.[38] A significant prehistoric Neolithic culture marked by Megalithic structures, which date back to c. 3600 BC, existed on the islands, as evidenced by the temples of Bugibba, Mnajdra, Ggantija and others. The Phoenicians colonised Malta between 800–700 BC, bringing their Semitic language and culture.[39] They used the islands as an outpost from which they expanded sea explorations and trade in the Mediterranean until their successors, the Carthaginians, were ousted by the Romans in 216 BC with the help of the Maltese inhabitants, under whom Malta became a municipium.[40]

After a probable sack by the Vandals,[41] Malta fell under Byzantine rule (4th to 9th century) and the islands were then invaded by the Aghlabids in AD 870. The fate of the population after the Arab invasion is unclear but it seems the islands may have been repopulated at the beginning of the second millennium by settlers from Arab-ruled Sicily who spoke Siculo-Arabic.[42]

The Muslim rule was ended by the Normans who conquered the island in 1091. The islands were completely re-Christianised by 1249.[43] The islands were part of the Kingdom of Sicily until 1530 and were briefly controlled by the Capetian House of Anjou. In 1530 Charles V of Spain gave the Maltese islands to the Order of Knights of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem in perpetual lease.

The French under Napoleon took hold of the Maltese islands in 1798, although with the aid of the British the Maltese were able to oust French control two years later. The inhabitants subsequently asked Britain to assume sovereignty over the islands under the conditions laid out in a Declaration of Rights,[44] stating that "his Majesty has no right to cede these Islands to any power...if he chooses to withdraw his protection, and abandon his sovereignty, the right of electing another sovereign, or of the governing of these Islands, belongs to us, the inhabitants and aborigines alone, and without control." As part of the Treaty of Paris in 1814, Malta became a British colony, ultimately rejecting an attempted integration with the United Kingdom in 1956.

Malta became independent on 21 September 1964 (Independence Day). Under its 1964 constitution, Malta initially retained Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Malta, with a Governor-General exercising authority on her behalf. On 13 December 1974 (Republic Day) it became a republic within the Commonwealth, with the President as head of state. On 31 March 1979, Malta saw the withdrawal of the last British troops and the Royal Navy from Malta. This day is known as Freedom Day and Malta declared itself as a neutral and non-aligned state. Malta joined the European Union on 1 May 2004 and joined the Eurozone on 1 January 2008.[45]

قبل التاريخ

Pottery found by archaeologists at the Skorba Temples resembles that found in Italy, and suggests that the Maltese islands were first settled in 5200 BC mainly by Stone Age hunters or farmers who had arrived from the Italian island of Sicily, possibly the Sicani. The extinction of the dwarf hippos and dwarf elephants has been linked to the earliest arrival of humans on Malta.[46] Prehistoric farming settlements dating to the Early Neolithic period were discovered in open areas and also in caves, such as Għar Dalam.[47]

The Sicani were the only tribe known to have inhabited the island at this time[38][48] and are generally regarded as being closely related to the Iberians.[49] The population on Malta grew cereals, raised livestock and, in common with other ancient Mediterranean cultures, worshiped a fertility figure represented in Maltese prehistoric artifacts exhibiting the proportions seen in similar statuettes, including the Venus of Willendorf.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Pottery from the Għar Dalam phase is similar to pottery found in Agrigento, Sicily. A culture of megalithic temple builders then either supplanted or arose from this early period. Around the time of 3500 BC, these people built some of the oldest existing free-standing structures in the world in the form of the megalithic Ġgantija temples on Gozo;[50] other early temples include those at Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra.[29][51][52]

The temples have distinctive architecture, typically a complex trefoil design, and were used from 4000 to 2500 BC. Animal bones and a knife found behind a removable altar stone suggest that temple rituals included animal sacrifice. Tentative information suggests that the sacrifices were made to the goddess of fertility, whose statue is now in the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta.[53] The culture apparently disappeared from the Maltese Islands around 2500 BC. Archaeologists speculate that the temple builders fell victim to famine or disease, but this is not certain.

Another archaeological feature of the Maltese Islands often attributed to these ancient builders is equidistant uniform grooves dubbed "cart tracks" or "cart ruts" which can be found in several locations throughout the islands, with the most prominent being those found in Misraħ Għar il-Kbir, which is informally known as "Clapham Junction". These may have been caused by wooden-wheeled carts eroding soft limestone.[54][55]

After 2500 BC, the Maltese Islands were depopulated for several decades until the arrival of a new influx of Bronze Age immigrants, a culture that cremated its dead and introduced smaller megalithic structures called dolmens to Malta.[56] In most cases, there are small chambers here, with the cover made of a large slab placed on upright stones. They are claimed to belong to a population certainly different from that which built the previous megalithic temples. It is presumed the population arrived from Sicily because of the similarity of Maltese dolmens to some small constructions found on the largest island of the Mediterranean sea.[57]

اليونانيون والفينيقيون والقرطاجيون والرومان

Phoenician traders[58] colonised the islands sometime after 1000 BC[13] as a stop on their trade routes from the eastern Mediterranean to Cornwall, joining the natives on the island.[59] The Phoenicians inhabited the area now known as Mdina, and its surrounding town of Rabat, which they called Maleth.[60][61] The Romans, who also much later inhabited Mdina, referred to it (and the island) as Melita.[31]

After the fall of Phoenicia in 332 BC, the area came under the control of Carthage, a former Phoenician colony.[13][62] During this time the people on Malta mainly cultivated olives and carob and produced textiles.[62]

During the First Punic War, the island was conquered after harsh fighting by Marcus Atilius Regulus.[63] After the failure of his expedition, the island fell back in the hands of Carthage, only to be conquered again in 218 BC, during the Second Punic War, by Roman Consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus.[63] After that, Malta became Foederata Civitas, a designation that meant it was exempt from paying tribute or the rule of Roman law, and fell within the jurisdiction of the province of Sicily.[31] Punic influence, however, remained vibrant on the islands with the famous Cippi of Melqart, pivotal in deciphering the Punic language, dedicated in the 2nd century BC.[64][65] Also the local Roman coinage, which ceased in the 1st century BC,[66] indicates the slow pace of the island's Romanization, since the last locally minted coins still bear inscriptions in Ancient Greek on the obverse (like "ΜΕΛΙΤΑΙΩ", meaning "of the Maltese") and Punic motifs, showing the resistance of the Greek and Punic cultures.[67]

The Greeks settled in the Maltese islands beginning circa 700 BC, as testified by several architectural remains, and remained throughout the Roman dominium.[68] They called the island Melite (باليونانية قديمة: Μελίτη).[69][70] At around 160 BC coins struck in Malta bore the Greek ‘ΜΕΛΙΤΑΙΩΝ’ (Melitaion) meaning ‘of the Maltese’. By 50 BC Maltese coins had a Greek legend on one side and a Latin one on the other. Later coins were issued with just the Latin legend ‘MELITAS’. The depiction of aspects of the Punic religion, together with the use of the Greek alphabet, testifies to the resilience of Punic and Greek culture in Malta long after the arrival of the Romans.[71]

In the 1st century BC, Roman Senator and orator Cicero commented on the importance of the Temple of Juno, and on the extravagant behaviour of the Roman governor of Sicily, Verres.[72] During the 1st century BC the island was mentioned by Pliny the Elder and Diodorus Siculus: the latter praised its harbours, the wealth of its inhabitants, its lavishly decorated houses and the quality of its textile products. In the 2nd century, Emperor Hadrian (r. 117–38) upgraded the status of Malta to municipium or free town: the island local affairs were administered by four quattuorviri iuri dicundo and a municipal senate, while a Roman procurator, living in Mdina, represented the proconsul of Sicily.[63] In 58 AD, Paul the Apostle was washed up on the islands together with Luke the Evangelist after their ship was wrecked on the islands.[63] Paul the Apostle remained on the islands three months, preaching the Christian faith.[63] The island is mentioned at the Acts of the Apostles as Melitene (باليونانية: Μελιτήνη).[73]

In 395, when the Roman Empire was divided for the last time at the death of Theodosius I, Malta, following Sicily, fell under the control of the Western Roman Empire.[74] During the Migration Period as the Western Roman Empire declined, Malta came under attack and was conquered or occupied a number of times.[66] From 454 to 464 the islands were subdued by the Vandals, and after 464 by the Ostrogoths.[63] In 533 Belisarius, on his way to conquer the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa, reunited the islands under Imperial (Eastern) rule.[63] Little is known about the Byzantine rule in Malta: the island depended on the theme of Sicily and had Greek Governors and a small Greek garrison.[63] While the bulk of population continued to be constituted by the old, Latinized dwellers, during this period its religious allegiance oscillated between the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople.[63] The Byzantine rule introduced Greek families to the Maltese collective.[75] Malta remained under the Byzantine Empire until 870, when it fell to the Arabs.[63][76]

الفترة العربية والعصور الوسطى

Malta became involved in the Arab–Byzantine wars, and the conquest of Malta is closely linked with that of Sicily that began in 827 after Admiral Euphemius' betrayal of his fellow Byzantines, requesting that the Aghlabids invade the island.[77] The Muslim chronicler and geographer al-Himyari recounts that in 870, following a violent struggle against the defending Byzantines, the Arab invaders, first led by Halaf al-Hadim, and later by Sawada ibn Muhammad,[78] looted and pillaged the island, destroying the most important buildings, and leaving it practically uninhabited until it was recolonised by the Arabs from Sicily in 1048–1049.[78] It is uncertain whether this new settlement took place as a consequence of demographic expansion in Sicily, as a result of a higher standard of living in Sicily (in which case the recolonisation may have taken place a few decades earlier), or as a result of civil war which broke out among the Arab rulers of Sicily in 1038.[79] The Arab Agricultural Revolution introduced new irrigation, some fruits and cotton, and the Siculo-Arabic language was adopted on the island from Sicily; it would eventually evolve into the Maltese language.[80]

The Christians on the island were allowed to practice their religion if they paid jizya, a tax for non-Muslims for exemption from military service, but non-Muslims were exempt from the tax that Muslims had to pay (zakat).[81]

الفتح النورماني

The Normans attacked Malta in 1091, as part of their conquest of Sicily.[82] The Norman leader, Roger I of Sicily, was welcomed by Christian captives.[31] The notion that Count Roger I reportedly tore off a portion of his checkered red-and-white banner and presented it to the Maltese in gratitude for having fought on his behalf, forming the basis of the modern flag of Malta, is founded in myth.[31][83]

Malta became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Sicily, which also covered the island of Sicily and the southern half of the Italian Peninsula.[31] The Catholic Church was reinstated as the state religion, with Malta under the See of Palermo, and some Norman architecture sprang up around Malta, especially in its ancient capital Mdina.[31] Tancred, King of Sicily, the second to last Norman monarch, made Malta a fief of the kingdom and installed a Count of Malta in 1192. As the islands were much desired due to their strategic importance, it was during this time that the men of Malta were militarised to fend off attempted conquest; early Counts were skilled Genoese privateers.[31]

The kingdom passed on to the dynasty of Hohenstaufen from 1194 until 1266. During this period, when Frederick II of Hohenstaufen began to reorganise his Sicilian kingdom, Western culture and religion began to exert their influence more intensely.[84] Malta was declared a county and a marquisate, but its trade was totally ruined. For a long time it remained solely a fortified garrison.[85]

A mass expulsion of Arabs occurred in 1224, and the entire Christian male population of Celano in Abruzzo was deported to Malta in the same year.[31] In 1249 Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, decreed that all remaining Muslims be expelled from Malta[86] or compelled to convert.[87][88]

For a brief period, the kingdom passed to the Capetian House of Anjou,[89] but high taxes made the dynasty unpopular in Malta, due in part to Charles of Anjou's war against the Republic of Genoa, and the island of Gozo was sacked in 1275.[31]

حكم تاج أراگون وفرسان مالطا

Malta was ruled by the House of Barcelona, the ruling dynasty of the Crown of Aragon, from 1282 to 1409,[90] with the Aragonese aiding the Maltese insurgents in the Sicilian Vespers in a naval battle in Grand Harbour in 1283.[91]

Relatives of the Kings of Aragon ruled the island until 1409 when it formally passed to the Crown of Aragon. Early on in the Aragonese ascendancy, the sons of the monarchs received the title Count of Malta. During this time much of the local nobility was created. By 1397, however, the bearing of the comital title reverted to a feudal basis, with two families fighting over the distinction, which caused some conflict. This led King Martin I of Sicily to abolish the title. The dispute over the title returned when the title was reinstated a few years later and the Maltese, led by the local nobility, rose up against Count Gonsalvo Monroy.[31] Although they opposed the Count, the Maltese voiced their loyalty to the Sicilian Crown, which so impressed King Alfonso that he did not punish the people for their rebellion. Instead, he promised never to grant the title to a third party and incorporated it back into the crown. The city of Mdina was given the title of Città Notabile as a result of this sequence of events.[31]

On 23 March 1530,[92] Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, gave the islands to the Knights Hospitaller under the leadership of Frenchman Philippe Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, Grand Master of the Order,[93][94] in perpetual lease for which they had to pay an annual tribute of one single Maltese Falcon.[95][96][97][98][99][100][101] These knights, a military religious order now known as the Knights of Malta, had been driven out of Rhodes by the Ottoman Empire in 1522.[102]

The Order of Saint John (also known as the Knights Hospitaller, or the Knights of Malta) were the rulers of Malta and Gozo between 1530 and 1798.[103] During this period, the strategic and military importance of the island grew greatly as the small yet efficient fleet of the Order of Saint John launched their attacks from this new base targeting the shipping lanes of the Ottoman territories around the Mediterranean Sea.[103][104]

In 1551, the population of the island of Gozo (around 5,000 people) were enslaved by Barbary pirates and taken to the Barbary Coast في شمال أفريقيا.[105]

The knights, led by Frenchman Jean Parisot de Valette, Grand Master of the Order, withstood the حصار مالطا الكبير by the Ottomans in 1565.[94] The knights, with the help of Spanish and Maltese forces, were victorious and repelled the attack. Speaking of the battle Voltaire said, "Nothing is better known than the siege of Malta."[106][107] After the siege they decided to increase Malta's fortifications, particularly in the inner-harbour area, where the new city of Valletta, named in honour of Valette, was built. They also established watchtowers along the coasts – the Wignacourt, Lascaris and De Redin towers – named after the Grand Masters who ordered the work. The Knights' presence on the island saw the completion of many architectural and cultural projects, including the embellishment of Città Vittoriosa (modern Birgu), the construction of new cities including Città Rohan (modern Ħaż-Żebbuġ) . Ħaż-Żebbuġ is one of the oldest cities of Malta, it also has one of the largest squares of Malta.

الفترة الفرنسية والفتح البريطاني

The Knights' reign ended when Napoleon captured Malta on his way to Egypt during the French Revolutionary Wars in 1798. Over the years preceding Napoleon's capture of the islands, the power of the Knights had declined and the Order had become unpopular. Napoleon's fleet arrived in 1798, en route to his expedition of Egypt. As a ruse towards the Knights, Napoleon asked for a safe harbour to resupply his ships, and then turned his guns against his hosts once safely inside Valletta. Grand Master Hompesch capitulated, and Napoleon entered Malta.[108]

During 12–18 June 1798, Napoleon resided at the Palazzo Parisio in Valletta.[109][110][111] He reformed national administration with the creation of a Government Commission, twelve municipalities, a public finance administration, the abolition of all feudal rights and privileges, the abolition of slavery and the granting of freedom to all Turkish and Jewish slaves.[112][113] On the judicial level, a family code was framed and twelve judges were nominated. Public education was organised along principles laid down by Bonaparte himself, providing for primary and secondary education.[113][114] He then sailed for Egypt leaving a substantial garrison in Malta.[115]

The French forces left behind became unpopular with the Maltese, due particularly to the French forces' hostility towards Catholicism and pillaging of local churches to fund Napoleon's war efforts. French financial and religious policies so angered the Maltese that they rebelled, forcing the French to depart. Great Britain, along with the Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily, sent ammunition and aid to the Maltese and Britain also sent her navy, which blockaded the islands.[113]

On 28 October 1798, Captain Sir Alexander Ball successfully completed negotiations with the French garrison on Gozo, the 217 French soldiers there agreeing to surrender without a fight and transferring the island to the British. The British transferred the island to the locals that day, and it was administered by Archpriest Saverio Cassar on behalf of Ferdinand III of Sicily. Gozo remained independent until Cassar was removed from power by the British in 1801.[116]

General Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois surrendered his French forces in 1800.[113] Maltese leaders presented the main island to Sir Alexander Ball, asking that the island become a British Dominion. The Maltese people created a Declaration of Rights in which they agreed to come "under the protection and sovereignty of the King of the free people, His Majesty the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland". The Declaration also stated that "his Majesty has no right to cede these Islands to any power...if he chooses to withdraw his protection, and abandon his sovereignty, the right of electing another sovereign, or of the governing of these Islands, belongs to us, the inhabitants and aborigines alone, and without control."[113][44]

الامبراطورية البريطانية والحرب العالمية الثانية

In 1814, as part of the Treaty of Paris,[113][117] Malta officially became a part of the British Empire and was used as a shipping way-station and fleet headquarters. After the Suez Canal opened in 1869, Malta's position halfway between the Strait of Gibraltar and Egypt proved to be its main asset, and it was considered an important stop on the way to India, a central trade route for the British.

A Turkish Military Cemetery was commissioned by Sultan Abdul Aziz and built between 1873-1874 for the fallen Ottoman soldiers of the Great Siege of Malta.

Between 1915 and 1918, during the First World War, Malta became known as the Nurse of the Mediterranean due to the large number of wounded soldiers who were accommodated in Malta.[118] In 1919 British troops fired on a rally protesting against new taxes, killing four Maltese men. The event, known as Sette Giugno (Italian for 7 June), is commemorated every year and is one of five National Days.[119][120]

Before the Second World War, Valletta was the location of the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet's headquarters; however, despite Winston Churchill's objections,[121] the command was moved to Alexandria, Egypt, in April 1937 out of fear that it was too susceptible to air attacks from Europe.[121][122][123]

During the Second World War, Malta played an important role for the Allies; being a British colony, situated close to Sicily and the Axis shipping lanes, Malta was bombarded by the Italian and German air forces. Malta was used by the British to launch attacks on the Italian navy and had a submarine base. It was also used as a listening post, intercepting German radio messages including Enigma traffic.[124] The bravery of the Maltese people during the second Siege of Malta moved King George VI to award the George Cross to Malta on a collective basis on 15 April 1942 "to bear witness to a heroism and devotion that will long be famous in history". Some historians argue that the award caused Britain to incur disproportionate losses in defending Malta, as British credibility would have suffered if Malta had surrendered, as British forces in Singapore had done.[125] A depiction of the George Cross now appears in the upper hoist corner of the Flag of Malta and on the country's arms. The collective award remained unique until April 1999, when the Royal Ulster Constabulary became the second – and, to date, the only other – recipient of a collective George Cross.[126]

الاستقلال والجمهورية

Malta achieved its independence as the State of Malta on 21 September 1964 (Independence Day) after intense negotiations with the United Kingdom, led by Maltese Prime Minister George Borġ Olivier. Under its 1964 constitution, Malta initially retained Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Malta and thus head of state, with a governor-general exercising executive authority on her behalf. In 1971, the Malta Labour Party led by Dom Mintoff won the general elections, resulting in Malta declaring itself a republic on 13 December 1974 (Republic Day) within the Commonwealth, with the President as head of state. A defence agreement was signed soon after independence, and after being re-negotiated in 1972, expired on 31 March 1979.[127] Upon its expiry, the British base closed down and all lands formerly controlled by the British on the island were given up to the Maltese government.[128]

Malta adopted a policy of neutrality in 1980.[129] In 1989, Malta was the venue of a summit between US President George H.W. Bush and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, their first face-to-face encounter, which signalled the end of the Cold War.[130]

On 16 July 1990, Malta, through its foreign minister, Guido de Marco, applied to join the European Union.[131] After tough negotiations, a referendum was held on 8 March 2003, which resulted in a favourable vote.[132] General Elections held on 12 April 2003, gave a clear mandate to the Prime Minister, Eddie Fenech Adami, to sign the treaty of accession to the European Union on 16 April 2003 in Athens, Greece.[133]

Malta joined the European Union on 1 May 2004.[134] Following the European Council of 21–22 June 2007, Malta joined the eurozone on 1 January 2008.[135]

الجغرافيا

البلاد تتكون من ثلاث جزر مأهولة بالسكان هي: مالطا، گوزو و كومينو، والجزر الغير مسكونة كومينوتو، فلفلة و جزيرة القديس بولص. هذه الجزر نشأت كبقايا للوصل الجغرافي اللذي كان يوما ما يربط قارتي أوروبا و أفريقيا سوية. Only the three largest islands – Malta (Malta), Gozo (Għawdex) and Comino (Kemmuna) – are inhabited. The islands of the archipelago lie on the Malta plateau, a shallow shelf formed from the high points of a land bridge between Sicily and North Africa that became isolated as sea levels rose after the last Ice Age.[136] The archipelago is located on the African tectonic plate.[137][138] Malta was considered an island of North Africa for centuries.[139]

Numerous bays along the indented coastline of the islands provide good harbours. The landscape consists of low hills with terraced fields. The highest point in Malta is Ta' Dmejrek, at 253 m (830 ft), near Dingli. Although there are some small rivers at times of high rainfall, there are no permanent rivers or lakes on Malta. However, some watercourses have fresh water running all year round at Baħrija near Ras ir-Raħeb, at l-Imtaħleb and San Martin, and at Lunzjata Valley in Gozo.

Phytogeographically, Malta belongs to the Liguro-Tyrrhenian province of the Mediterranean Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Malta belongs to the ecoregion of "Mediterranean Forests, Woodlands and Scrub".[140]

The minor islands that form part of the archipelago are uninhabited and include:

- Barbaġanni Rock (گوزو)

- Cominotto, (Kemmunett)

- Dellimara Island (Marsaxlokk)

- فلفلة (Żurrieq)/(Siġġiewi)

- Fessej Rock

- Fungus Rock, (Il-Ġebla tal-Ġeneral) (گوزو)

- Għallis Rock (Naxxar)

- Ħalfa Rock (گوزو)

- Large Blue Lagoon Rocks (كومينو)

- Islands of St. Paul/Selmunett Island (مليحة)

- Manoel Island, which connects to the town of Gżira, on the mainland, via a bridge

- Mistra Rocks (سان پاول البحار)

- Taċ-Ċawl Rock (گوزو)

- Qawra Point/Ta' Fraben Island (سان پاول البحار)

- Small Blue Lagoon Rocks (كومينو)

- Sala Rock (Żabbar)

- Xrobb l-Għaġin Rock (Marsaxlokk)

- Ta' taħt il-Mazz Rock

المناخ

Malta has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa),[24][141] with mild winters and hot summers, hotter in the inland areas. Rain occurs mainly in autumn and winter, with summer being generally dry.

The average yearly temperature is around 23 °C (73 °F) during the day and 15.5 °C (59.9 °F) at night. In the coldest month – January – the typical maximum temperature ranges from 12 إلى 18 °C (54 إلى 64 °F) during the day and minimum 6 إلى 12 °C (43 إلى 54 °F) at night. In the warmest month – August – the typical maximum temperature ranges from 28 إلى 34 °C (82 إلى 93 °F) during the day and minimum 20 إلى 24 °C (68 إلى 75 °F) at night. Amongst all capitals in the continent of Europe, Valletta – the capital of Malta has the warmest winters, with average temperatures of around 15 إلى 16 °C (59 إلى 61 °F) during the day and 9 إلى 10 °C (48 إلى 50 °F) at night in the period January–February. In March and December average temperatures are around 17 °C (63 °F) during the day and 11 °C (52 °F) at night.[142] Large fluctuations in temperature are rare. Snow is very rare on the island, although various snowfalls have been recorded in the last century, the last one reported in various locations across Malta in 2014.[143]

مناخ البلاد هو مناخ البحر المتوسط. معدل درجات الحرارة الشهرية تتراوح بين 12 و 26 درجة مئوية، بينما هو 19 درجة مئوية كمعدل للعام كله. نسبة هطول الأمطار تبلغ زهاء 500 مم، معظمها تسقط في أشهر الشتاء.

| بيانات المناخ لـ Malta (Luqa in the south-east part of main island, 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 15.6 (60.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.8 (89.2) |

28.5 (83.3) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | 12.8 (55.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.8 (67.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.2 (81.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

21.5 (70.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

14.4 (57.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | 9.9 (49.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

20.8 (69.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 98.5 (3.88) |

60.1 (2.37) |

44.2 (1.74) |

20.7 (0.81) |

16.0 (0.63) |

4.6 (0.18) |

0.3 (0.01) |

12.8 (0.50) |

58.6 (2.31) |

82.9 (3.26) |

92.3 (3.63) |

109.2 (4.30) |

595.8 (23.46) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 58 |

| Mean monthly ساعات سطوع الشمس | 169.3 | 178.1 | 227.2 | 253.8 | 309.7 | 336.9 | 376.7 | 352.2 | 270.0 | 223.8 | 195.0 | 161.2 | 3٬054 |

| Source: Meteo Climate (1981–2010 Data),[144] MaltaWeather.com (Sun data)[145] | |||||||||||||

النبيت

The Maltese islands are home to a wide diversity of indigenous, sub-endemic and endemic plants.[146] They feature many traits typical of a Mediterranean climate, such as drought resistance. The most common indigenous trees on the islands are olive (Olea europaea), carob (Ceratonia siliqua), fig (ficus carica), holm oak (Quericus ilex) and Aleppo pine (Pinus halpensis), while the most common non-native trees are eucalyptus, acacia and opuntia. Endemic plants include the national flower widnet il-baħar (Cheirolophus crassifolius), sempreviva ta' Malta (Helichrysum melitense), żigland t' Għawdex (Hyoseris frutescens) and ġiżi ta' Malta (Matthiola incana subsp. melitensis) while sub-endemics include kromb il-baħar (Jacobaea maritima subsp. sicula) and xkattapietra (Micromeria microphylla).[147] The flora and biodiversity of Malta is severely endangered by habitat loss, invasive species and human intervention.[148]

السكان

عدد سكان مالطا يراوح الأربعمائة ألف نسمة. بسبب صغر مساحة البلاد، فإن نسبة الكثافة السكانية تعد عالية جدا، تبلغ حوالي 1200 نسمة للكم المربع. هذه النسبة تجعل منها ثالث أعلى بلد بالعالم من حيث الكثافة السكانية. 94% من سكان البلاد يسكنون في المدن. كما يبلغ نسبة الأجانب حوالي 5% من مجموع السكان. يبلغ عدد سكان جزيرة گوزو حوالي ثلاثين ألف نسمة، بينما هو عدد ضئيل لا يذكر على جزيرة كومينو.

غالبية سكان مالطا هم مسيحيون كاثوليك. هناك عدد ضئيل من الأديان الأخرى في البلاد. تأثير الكنيسة كبير على سياسة الدولة الداخلية، على سبيل المثال، فإن الإجهاض والطلاق ليس هو محرم دينيا فحسب، و إنما مرتكبيهم يعرضوا أنفسهم للمساءلة القانونية والغرامات. المذهب الكاثوليكي مذكور في الدستور كدين رسمي للبلاد.

اللغة المالطية هي إحدى اللغات السامية، نتجت عن لهجة عربية. لذا تجد أن حوالي 40% من اللغة المالطية أصلها عربي، الباقي من الإيطالية و الإنجليزية و الفرنسية و الإسبانية وخاصة الكلمات. اللغة المالطية تستعمل الأحرف اللاتينية لتكون بذلك أول لغة سامية تكتب باللاتيني. بسبب الإستعمار البريطاني الطويل للبلاد، فإن اللغة الانگليزية منتشرة بكثرة في البلاد و خاصة في الدوائر الحكومية، و تأتي في الأهمية قبل الإيطالية.

الديانة

السياسة

النظام السياسي

يتم انتخاب رئيس الجمهورية من خلال البرلمان المالطي. الرئيس له مهام فخرية. يقوم بتسمية رئيس الوزراء اعتمادا على نتائج الانتخابات، عادة يكون هو رئيس الحزب الفائز بالانتخابات النيابية. مجلس الوزراء يجب أن تتم الموافقة عليه من قبل البرلمان المالطي ذو المجلس الأحادي، يدعى بالمالطية Kamra tar-Rappreżentanti أي مجلس النواب. يتكون المجلس من 65 - 69 عضو، يتم انتخابهم كل خمس سنوات.

تمت تعدلة الدستور بعد الأزمة السياسية اللتي حدثت عام 1981 على خلفية عدم حصول أي من الأحزاب السياسية على عدد المقاعد المطلوب لتشكيل حكومة. حيث ينقسم الناخبون المالطيون نسبة لتوجهاتهم الحزبية، لدرجة يكاد لا يوجد لها شبيه بالعالم. على سبيل المثال فإن 60% من الشعب أيد انضمام مالطا إلى الاتحاد الأوروبي، كانت تلك النتيجة تعد أغلبية عظمى بالنسبة لاستفتاءات و انتخابات الجزيرة. أهم الأحزاب السياسية بالبلاد هم الوطنيون المحافظون و حزب العمل.

التقسيم الاداري و أهم المدن

مالطا مقسمة منذ عام 1993 إلى 68 دائرة إدارية. أهم مدن البلاد إلى جانب العاصمة فاليتا (حوالي 7,000 نسمة/2000) هي بير كاركارة (حوالي 25,000 نسمة)، سلامة، سانت جوليانز، رباط أو فكتوريا (حوالي 6,000 نسمة)، بير زبوج و حمرون. مدن سلامة و سانت جوليانز تقعان على أطراف فاليتا،لذا هما امتداد لها.

الاقتصاد و البنية التحتية

أهم ركائن الإقتصاد المالطي هي قطاعات الزراعة، صيد الأسماك و السياحة. شركة مالطا دراي دوكس (Malta Drydocks) هي أكبر مشغل للعمالة في البلاد و ثاني أكبر حوض بناء سفن في أوروبا. معظم السياح يأتون من المملكة المتحدة، ألمانيا، إيطاليا و ليبيا. يبلغ عددهم سنويا حوالي نصف مليون نسمة. تم عام 1992 إنشاء بورصة للأوراق المالية في مالطا. هناك علاقات تجارية قوية مع كل من إيطاليا و ليبيا.

لا توجد شبكة سكك حديدية على الجزيرة، في المقابل هناك شبكة حافلات كثيفة تربط معظم مناطق مالطا ببعضها و خاصة حول العاصمة فاليتا. يعود تاريخ هذه الشبكة إلى حقبة الإستعمار البريطاني. المطار الدولي يوجد في لوقا، من هناك يوجد خط مروحيات يربط مالطا بجزيرة غوزو. توجد أيضا حركة عبارات تسير عدة مرات يوميا الى غوزو، بينما هي حركتها أندر الى جزيرة كومينو.

الثقافة و التعليم

الثقافة المالطية متأثرة بجيرانها و محتليها عبر التاريخ، وخاصة إيطاليا شمالاً و بريطانيا (المستعمر السابق)، لغويا هي متأثرة أيضا بالدول العربية جنوبا. كما ذكر أعلاه فإن تأثير الكنيسة قوي في البلاد. حاولت مالطا محاربة التأثير الثقافي الإيطالي في البلاد من خلال تبني الإنگليزية كلغة رسمية وخاصة في التعليم. الآن تشكل القنوات التلفزيونية الإيطالية العديدة السفير الأول لإيطاليا في البيوت المالطية، يليهم السياح الطليان اللذين يزورون البلاد بالآلاف سنويا. النظام المروري في مالطا يتبع النظام الانغليزي، أي السواقة على يسار الشارع. الرقص الفلكلوري المالطي هو شبيه بالرقص الإيطالي والعربي، من خلال مجموعات رجالية ونسائية تتشابك الأيدي (الدبكة). المطبخ الإيطالي دارج في مالطا.

هناك ثلاث مناطق في مالطا ، اعتبرتها منظمة اليونسكو من التراث العالمي: العاصمة فاليتا، حيث تشتهر بأزقتها التاريخية، المعابد الجلمودية، التي يعود تاريخها الى العصر الحجري، ومعبد حال صافليني، الذي يعود تاريخه ثلاثة آلاف سنة الى الوراء.

انظر أيضا

ملاحظات

- ^ أ ب "Europeans and their Languages" (PDF). المفوضية الأوروپية. Special Eurobarometer. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ Diacono, Tim (April 18, 2019). "Over 100,000 Foreigners Now Living In Malta As Island's Population Just Keeps Ballooning". lovinmalta.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ أ ب Zammit, Andre (1986). "Valletta and the system of human settlements in the Maltese Islands". Ekistics. 53 (316/317): 89–95. JSTOR 43620704.

- ^ أ ب "News release" (PDF). National Statistics Office. 10 July 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ أ ب "Census of Population and Housing 2011: Report" (PDF). National Statistics Office. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Malta". International Monetary Fund.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Lesley, Anne Rose (15 April 2009). Frommer's Malta and Gozo Day by Day. John Wiley & Sons. p. 139. ISBN 978-0470746103. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Maltese sign language to be recognised as an official language of Malta". The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ انظر مدخل 'Malta' في Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Chapman, David; Cassar, Godwin (October 2004). "Valletta". Cities. 21 (5): 451–463. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2004.07.001.

- ^ أ ب ت Ashby, Thomas (1915). "Roman Malta". Journal of Roman Studies. 5: 23–80. doi:10.2307/296290. JSTOR 296290.

- ^ Bonanno, Anthony (ed.). Malta and Sicily: Miscellaneous research projects (PDF). Palermo: Officina di Studi Medievali. ISBN 978-8888615837. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Sultana, Ronald G. (1998). "Career guidance in Malta: A Mediterranean microstate in transition" (PDF). International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling. 20: 3. doi:10.1023/A:1005386004103. S2CID 49470186. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ "The Microstate Environmental World Cup: Malta vs. San Marino". Environmentalgraffiti.com. 15 December 2007. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ "First inhabitants arrived 700 years earlier than thought". Times of Malta. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- ^ Boissevain, Jeremy (1984). "Ritual Escalation in Malta". In Eric R. Wolf (ed.). Religion, Power and Protest in Local Communities: The Northern Shore of the Mediterranean. Walter de Gruyter. p. 165. ISBN 9783110097771. ISSN 1437-5370.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Rudolf, Uwe Jens; Berg, Warren G. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Malta. Scarecrow Press. pp. 1–11. ISBN 9780810873902.

- ^ "GEORGE CROSS AWARD COMMEMORATION". VisitMalta.com. 14 April 2015. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Should the George Cross still be on Malta's flag?". The Times. 29 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Christmas Broadcast 1967". Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Constitution of Malta". Ministry for Justice, Culture and Local Government. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2018. - Article 40: "all persons in Malta shall have full freedom of conscience and enjoy the free exercise of their respective mode of religious worship."

- ^ أ ب Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). "Malta". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ^ "Hal Saflieni Hypogeum". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "City of Valletta". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Megalithic Temples of Malta". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Malta Temples and The OTS Foundation". Otsf.org. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ أ ب Daniel Cilia, Malta Before History (2004: Miranda Publishers) ISBN 9990985081

- ^ μέλι. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س Castillo, Dennis Angelo (2006). The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313323294. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ قالب:L&S

- ^ Pickles, Tim (1998). Malta 1565: Last Battle of the Crusades. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-603-3. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Renaming Malta the Republic of Phoenicia". The Times. Malta: Allied Newspapers Ltd. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Smith, William (1872). John Murray (ed.). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Vol. II. John Murray, 1872. p. 320. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ "700 years added to Malta's history". Times of Malta. 16 March 2018. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018.

- ^ أ ب "Gozo". IslandofGozo.org. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009.

- ^ Bonanno 2005, p.22

- ^ Dennis Angelo Castillo (2006). The Maltese Cross A Strategic History of Malta. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-313-32329-4.

- ^ Victor Paul Borg (2001). Malta and Gozo. Rough Guides. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-85828-680-8.

- ^ So who are the 'real' Maltese. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

There's a gap between 800 and 1200 where there is no record of civilisation. It doesn't mean the place was completely uninhabited. There may have been a few people living here and there, but not much……..The Arab influence on the Maltese language is not a result of Arab rule in Malta, Prof. Felice said. The influence is probably indirect, since the Arabs raided the island and left no-one behind, except for a few people. There are no records of civilisation of any kind at the time. The kind of Arabic used in the Maltese language is most likely derived from the language spoken by those that repopulated the island from Sicily in the early second millennium; it is known as Siculo-Arab. The Maltese are mostly descendants of these people.

- ^ The origin of the Maltese surnames.

Ibn Khaldun puts the expulsion of Islam from the Maltese Islands to the year 1249. It is not clear what actually happened then, except that the Maltese language, derived from Arabic, certainly survived. Either the number of Christians was far larger than Giliberto had indicated, and they themselves already spoke Maltese, or a large proportion of the Muslims themselves accepted baptism and stayed behind. Henri Bresc has written that there are indications of further Muslim political activity in Malta during the last Suabian years. Anyhow there is no doubt that by the beginning of Angevin times no professed Muslim Maltese remained either as free persons or even as serfs on the island.

- ^ أ ب Holland, James (2003). Fortress Malta An Island Under Siege 1940–43. Miramax. ISBN 978-1-4013-5186-1.

- ^ Busuttil, Salvino; Briguglio, Lino. "Malta". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Palaeolithic Man in the Maltese Islands, A. Mifsud, C. Savona-Ventura, S. Mifsud

- ^ Skeates, Robin (2010). An Archaeology of the Senses: Prehistoric Malta. Oxford University Press. pp. 124–132. ISBN 978-0-19-921660-4. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Brief History of Malta". LocalHistories.org. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- ^ Anthon, Charles (1848). A Classical Dictionary: Containing an Account of the Principal Proper Names. New York Public Library. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Old Temples Study Foundation". OTSF. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ Sheehan, Sean (2000). Malta. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-0993-9. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Archaeology and prehistory". Aberystwyth, The University of Wales. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ "National Museum of Archaeology". Visitmalta.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010.

- ^ "Ancient mystery solved by geographers". Port.ac.uk. 20 April 2009. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Mottershead, Derek; Pearson, Alastair; Schaefer, Martin (2008). "The cart ruts of Malta: an applied geomorphology approach". Antiquity. 82 (318): 1065–1079. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00097787.

- ^ Daniel Cilia, "Malta Before Common Era", in The Megalithic Temples of Malta. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^ Piccolo, Salvatore; Darvill, Timothy (2013). Ancient Stones, The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily. Abingdon/GB: Brazen Head Publishing. ISBN 9780956510624.

- ^ "Notable dates in Malta's history". Department of Information – Maltese Government. 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ Owen, Charles (1969). The Maltese Islands. Praeger. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Mdina & The Knights". Edrichton.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Cassar 2000, pp. 53–55

- ^ أ ب Terterov, Marat (2005). Doing Business with Malta. GMB Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-905050-63-5. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر "Malta". treccani.it (in الإيطالية). Enciclopedia Italiana. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ The Art Journal: The Illustrated Catalogue of the Industry of All Nations, Volume 2. Virtue. 1853. p. vii. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ "Volume 16, Issue 1". Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ أ ب Cassar 2000, pp. 56–57

- ^ "218 BC – 395 AD Roman Coinage". centralbankmalta.org. Bank of Malta. Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ Caruana, A. A. (1888). "Remains of an Ancient Greek Building Discovered in Malta". The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts. 4 (4): 450–454. doi:10.2307/496131. JSTOR 496131.

- ^ Lycophron, Alexandra

- ^ Procopius, History of the Wars, 7.40

- ^ "Timeline Coins - Central Bank of Malta". www.centralbankmalta.org. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Roman Times – History of Malta – Visit Malta". Roman Times. visitmalta.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ St. Luke, Acts of the Apostles, 28.1

- ^ Brown, Thomas S. (1991). "Malta". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1277. ISBN 978-0195046526.

- ^ Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L. (1975). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08691-2. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Troll, Christian W.; Hewer, C.T.R. (12 September 2012). "Journeying toward God". Christian Lives Given to the Study of Islam. Fordham Univ Press. p. 258. ISBN 9780823243198.

- ^ "Brief history of Sicily" (PDF). Archaeology.Stanford.edu. 7 October 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ أ ب Travel Malta. The Arab period and the Middle Ages: MobileReference. ISBN 9781611982794.

- ^ Brincat, M.J. (1995) Malta 870–1054 Al-Himyari's Account and its Linguistic Implications. Valletta, Malta: Said International.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (2006). Corpus Linguistics Around the World. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-1836-5. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Bain, Carolyn (2004). Malta & Gozo. Lonely Planet. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-74059-178-2. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Previté-Orton (1971), pg. 507–11

- ^ Blouet, B. (1987) The Story of Malta. Third Edition. Malta: Progress Press, p.37.

- ^ Blouet, B. (1987) The Story of Malta. Third Edition. Malta: Progress Press, p.37-38.

- ^ Martin, Robert Montgomery (1843). History of the colonies of the British Empire Archived 6 سبتمبر 2015 at the Wayback Machine, W. H. Allen, p. 569: "Malta remained for 72 years subject of the emperors of Germany. The island was after the period of Count Roger of the Normans afterward given up to the Germans, on account of the marriage between Constance, heiress of Sicily, and Henry VI, son of the Emperor Friedrick Barbarossa. Malta was elevated to a county and a marquisate, but its trade was now totally ruined, and for a considerable period of it remained solely a fortified garrison."

- ^ "Time-Line". AboutMalta.com. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ Goodwin, Stefan (2002). Malta, Mediterranean bridge Archived 6 سبتمبر 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 31 ISBN 0897898206.

- ^ Peregin, Christian (4 August 2008). "Maltese makeover". The Times. Malta. Archived from the original on 9 October 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Malta under the Angevins Archived 17 أكتوبر 2017 at the Wayback Machine. melitensiawth.com

- ^ "Superintendance of Cultural Heritage". Government of Malta. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Luttrell, Anthony (1970). "The House of Aragon and Malta: 1282–1412" (PDF). Journal of the Faculty of Arts. 4 (2): 156–168. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Denaro, Victor F. (1963). Yet More Houses in Valletta Archived 2 مارس 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Melita Historica. p. 22.

- ^ de Vertot, Abbe (1728) The History of the Knights of Malta vol. II (facsimile reprint Midsea Books, Malta, 1989).

- ^ أ ب "Malta History". Jimdiamondmd.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "Malta History 1000 AD–present". Carnaval.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "La cesión de Malta a los Caballeros de San Juan a través de la cédula del 4 de marzo de 1530" (PDF). orderofmalta.int. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ "LA SOBERANA ORDEN DE MALTA A TRAVÉS DE DIEZ SIGLOS DE HISTORIA Y SU RELACIÓN CON LA ACCIÓN HUMANITARIA" (PDF). uma.es. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ El halcón maltés regresará a España dos siglos después Archived 3 مارس 2016 at the Wayback Machine. El Pais (14 August 2005). Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ "La verdadera historia del halcón maltés". Archived from the original on 30 May 2016.

- ^ "El halcón y el mar". trofeocaza.com. 22 October 2014. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016.

- ^ "El Rey volverá a tener otro halcón maltés en primavera". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ "Hospitallers – religious order". Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ أ ب Devrim., Atauz, Ayse (2008). Eight thousand years of Maltese maritime history : trade, piracy, and naval warfare in the central Mediterranean. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813031798. OCLC 163594113.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McManamon, John (June 2003). "Maltese seafaring in mediaeval and post-mediaeval times". Mediterranean Historical Review. 18 (1): 32–58. doi:10.1080/09518960412331302203. ISSN 0951-8967. S2CID 153559318.

- ^ Niaz, Ilhan (2014). Old World Empires: Cultures of Power and Governance in Eurasia. Routledge. p. 399. ISBN 978-1317913795.

- ^ Angelo Castillo, Dennis (2006). The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-313-32329-4. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Braudel, Fernand (1995) The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, vol. II. University of California Press: Berkeley.قالب:Page

- ^ Frendo, Henry (December 1998). "The French in Malta 1798 – 1800 : reflections on an insurrection". Cahiers de la Méditerranée. 57 (1): 143–151. doi:10.3406/camed.1998.1231. ISSN 1773-0201. Archived from the original on 5 June 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ "Palazzo Parisio". gov.mt. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ "Napoleon's bedroom at Palazzo Parisio in Valletta!". maltaweathersite.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ Stagno-Navarra, Karl (24 January 2010). "Leaving it in neutral". MaltaToday. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ "This day, May 15, in Jewish history". Cleveland Jewish News. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Sciberras, Sandro. "Maltese History – F. The French Occupation" (PDF). St Benedict College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Weider, Ben. "Chapter 12 – The Egyptian Campaign of 1798". International Napoleonic Society. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016.

- ^ Shosenberg, J.W. (April 2017). "NAPOLÉON'S EGYPTIAN RIDDLE". Military History. 34 (1): 25 – via Ebsco.

- ^ Schiavone, Michael J. (2009). Dictionary of Maltese Biographies A-F. Malta: Publikazzjonijiet Indipendenza. pp. 533–534. ISBN 9789993291329.

- ^ Rudolf & Berg 2010, p. 11

- ^ Galea, Michael (16 November 2014). "Malta earns the title 'nurse of the Mediterranean'". The Times. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016.

- ^ "Malta definition of Malta in the Free Online Encyclopedia.". Free Online Encyclopedia – List of Legal Holidays. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "SETTE GIUGNO". Visitmalta – The official tourism website for Malta, Gozo and Comino. Archived from the original on 30 يناير 2014. Retrieved 8 يوليو 2013.

- ^ أ ب Bierman, John; Smith, Colin (2002). The Battle of Alamein: Turning Point, World War II. Viking. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-670-03040-8.

- ^ Titterton, G. A. (2002). The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean, Volume 2. Psychology Press. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-7146-5179-8.

- ^ Elliott, Peter (1980). The Cross and the Ensign: A Naval History of Malta, 1798–1979. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-926-9.

- ^ Calvocoressi, Peter (1981). Top Secret Ultra – Volume 10 of Ballantine Espionage Intelligence Library (reprint ed.). Ballantine Books. pp. 42, 44. ISBN 978-0-345-30069-0.

- ^ "The Siege of Malta in World War Two". Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ^ "RUC awarded George Cross". BBC News. 23 November 1999. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ Wolf, Eric R. (1984). Religion, Power and Protest in Local Communities: The Northern Shore of the Mediterranean. p. 206. ISBN 978-3-11-086116-7.

- ^ Fenech, Dominic (February 1997). "Malta's external security". GeoJournal. 41 (2): 153–163. doi:10.1023/A:1006888926016. S2CID 151123282.

- ^ Breacher, Michael (1997). A Study of Crisis. University of Michigan Press. p. 611. ISBN 9780472108060.

- ^ "1989: Malta summit ends Cold War". BBC: On This Day. 3 December 1989. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Grima, Noel (2 October 2011). "Retaining Guido De Marco's Euro-Mediterranean vision". The Malta Independent. Standard Publications Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Malta votes 'yes' to EU membership". CNN. 9 March 2003. Archived from the original on 13 March 2003. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Bonello, Jesmond (17 April 2013). "Malta takes its place in EU". The Times. Malta. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "The History of the European Union – 2000–today". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ "Cyprus and Malta set to join eurozone in 2008". 16 May 2007. Archived from the original on 30 January 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ "Island Landscape Dynamics: Examples from the Mediterranean". Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ Commission for the Geological Map of the World. "Geodynamic Map of the Mediterranean". Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ^ "Geothermal Engineering Research Office Malta". Archived from the original on 4 April 2016.

- ^ Falconer, William; Falconer, Thomas (1872). Dissertation on St. Paul's Voyage. BiblioLife. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-113-68809-5. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Mediterranean Forests, Woodlands and Scrub – A Global Ecoregion". Panda.org. Archived from the original on 13 March 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ^ The Maltese Islands Archived 3 يوليو 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Information – Malta.

- ^ Weather of Malta Archived 25 يونيو 2017 at the Wayback Machine – MET Office in Malta International Airport

- ^ Ltd, Allied Newspapers. "Updated – 'Snowflakes' reported in several parts of Malta – Met Office 'monitoring' situation". Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ "Luqa Weather Averages 1981–2010". Meteo-climat-bzh.dyndns.org. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ "Malta's Climate". Maltaweather.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT REPORT 2005" (PDF). 2005: 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Mifsud, Stephen (23 September 2002). "Wild Plants of Malta and Gozo – Main Page". www.maltawildplants.com (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ "Maltese Biodiversity under threat – The Malta Independent". www.independent.com.mt. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

وصلات خارجية

- Malta travel guide from Wikitravel

- Gov.mt - Maltese Government official site.

- Diving Malta - All the dive sites in Malta

- Laws of Malta - A summary of principal laws and glossary of terms.

- Malta

- The Maltese Armed Forces official website

- The Nobility of Malta and Maltagenealogy.com

- Malta Environment and Planing Authority's GIS Map Server which includes place names and street's layout and names

- Official Maltese Tourism website

- 101 Things to do in malta an offbeat guide to what to do in Malta and Gozo

المصادر

- "Photos of Gozo sister island of Malta". Photos of Gozo.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Photos of Malta". Photos of Malta.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Malta". CIA World Factbook.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Gov.mt". Government of Malta.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Malta". MSN Encarta.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "1942: Malta gets George Cross for bravery". BBC "On this day".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessdaymonth=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Jones, H. Bowen (1962). Malta Background for Development. Dhurham College. OCLC 204863.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Carolyn Bain (2004). Malta. Lonely Planet Publication. ISBN 1-74059-178-X.

- United Nations Development Programme (2006). Human Development Report 2005 - International cooperation at a crossroads: Aid, trade and security in an unequal world. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-522146-X.

- Omertaa, Journal for Applied Anthropology - Volume 2007/1, Thematic Issue on Malta

- Malta-The George Cross Island

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- CS1 الإيطالية-language sources (it)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing مالطية-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Pages using infobox country with syntax problems

- Pages including recorded pronunciations

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2017

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Pages with empty portal template

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- مالطا

- Collective George Cross recipients

- بلدان تتحدث الايطالية

- بلدان ومناطق تتحدث الاسبانية

- بلدان جزر

- جزر البحر المتوسط

- أعضاء في كومنولث الأمم

- مستعمرات بريطانية سابقة

- ديموقراطيات لبيرالية

- جزر

- بلدان أوروپا