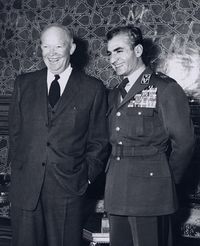

دوايت أيزنهاور

دوايت ديڤد "آيك" آيزنهاور Dwight David Eisenhower (تُنطق /ˈaɪzənhaʊər/, EYE-zən-how-ər؛ و. 14 أكتوبر 1890 - ت. 28 مارس 1969)، هو رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 34 من 1953 حتى 1961. وكان جنرال في الجيش الأمريكي أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية وكان القائد الأعلى للحلفاء في اوروپا؛ وكان مسئول عن التخطيط والإشراف على غزو شمال أفريقيا في عملية الشعلة عام 1942-43 والغزو الناجح لفرنسا وألمانيا عام 1944–45 من الجبهة الغربية. عام 1951، أصبح أول قائد أعلى للناتو.[2]

كان أيزنهاور من أصول هولندية وقد تربى في عائلة كبيرة في كانزس وكان والديه ذوي خلفية عملية ودينية متشددة. في ظل أسرة بها ستة صبية، نشأ في بيئة تنافسية تغرس مبادئ الاعتماد على اذات. تخرج من وست پوينت وبعدها تزوج وأنجب ولدين. بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية، كان أيزنهاور القائد الأعلى للقوات المسلحة في عهد الرئيس هاري ترومان، ثم تقلد منصب رئيس جامعة كلومبيا.[3]

خاض أيزنهاور الانتخابات الرئاسية 1952، كمرشح للحزب الجمهورية أمام السناتور روبرت أ. تافت ولشن حملة قوية ضد "الشيوعية، كوريا والفساد". فاز بأغلبية ساحقة، بعد هزيمته للديمقراطي أدلاي ستڤنسون وكان ذلك نهاية تحالف الصفقة الجديدة. في السنة الأولى من رئاسته، خلع أيزنهاور الرئيس الإيراني في الانقلاب الإيراني 1953 واستخدم التهديدات النووية لإنهاء الحرب الكورية مع الصين. في ظل سياسة نيو لوك التي اتبعها في مسألة الردع النووي أعطى أولوية للأسلحة النووية بينما قلل من تمويل القوات العسكرية التقليدية؛ وكان الهدف هو الضغط على الاتحاد السوڤيتي الذي كما وصفه أيزنهاور، التهديد الذي يمثله انتشار الشيوعية. عام 1955 وافق الكونگرس على طلبه الخاص بقرار فورموسا، الذي مكنه من منع العدوان الشيوعي الصيني على القوميين الصينيين وأسس السياسة الأمريكية في الدفاع عن تايوان. أجبر أيزنهاور إسرائيل، المملكة المتحدة وفرنسا بإنهاء عدوانهم على مصر أثناء أزمة السويس 1956. عام 1958، أرسل 15.000 جندي أمريكي إلى لبنان لمنع الحكومة المالية للغرب من السقوط بعد قيام ثورة 23 يوليو في مصر. قرب انتهاء فترته الرئاسية، عمل على عقد لقاء قمة مع السوڤييت إلا أنها لم تعقد بسبب حادث يو-2.[4]

على الجبهة الداخلية، عارض أيزنهاور سراً جوسف مكارثي وأسهم في إنتهاء المكارثية من خلال الاستدعاء العلني للنسخة الموسعة الحديثة من الامتياز التنفيذي. ترك معظم الأنشطة السياسية لنائبه، ريتشارد نيكسون. كان أيزنهاور محافظ معتدل ساهم في وكالات الصفقة الجديدة والضمان الاجتماعي الموسعة.

من ضمن المشروعات التي تمت في عهده، أطلق نظام الطرق السريعة بين الولايات؛ وكالة مشورعات الأبحاث الدفاعية المتقدمة (DARPA)، التي أدت إلى ابتكار الإنترنت، من بين الكثير من الابتكارات التي لا تقدر بثمن، بدء الاستشكاف السلفي للفضاء؛ تأسيس التعليم العلمي عن طريق قانون تعليم الدفاع الوطني؛ وتشجيع الاستخدامات السلمية للطاقة النووية عن طريق تعديلات قانون الطاقة الذرية.[5]

فيما يخص السياسية الاجتماعية، أرسل أيزنهاور قوات فدرالية إلى ليتل روك، أركنساس، لأول مرة منذ إعادة الإعمار تنفيذ أوامر المحكمة الاتحادية بإلغاء الفصل التمييزي المدارس الحكومية. وقع أيضاً على تشريع الحقوق المدنية عام 1957 و1960 لحماية حق الانتخاب. خلال عامين طبق إلغاء الفصل العنصري في القوات المسلحة وقام بخمسة تعيينات في المحكمة العليا. وكان أول رئيس يقضي فترة رئاسية أولى محدودة تماشياً مع التعديل رقم 22. كانت فترتيه الرئاسيتين في معظمهما سلمية وشهدت ازدهاراً اقتصادياً كبيراً عدا فترة الكساد عام 1958-59.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

حياته المبكرة والتعليم

هاجرت عائلة أيزوهاور من كارلسبرون، ألمانيا إلى سويسرا في القرن السابع عشر بسبب الاضطهاد الديني، وفي القرن التالي هاجرت للولايات المتحدة. استقرت العائلة في يورك، پنسلڤانيا، عام 1730، وفي ثمانينيات القرن التاسع عشر انتقلت إلى كنساس.[6] كان اسم العائلة بالألمانية أيرون هاور "iron hewer" وتختلف التفسيرات حول تكيفية تغيير الإسم إلى النطق الأمريكي أيزنهاور.[7] كان غالبية جدود العائلة من پنسلڤانيا الهولندية من المزارعين، ومنهم هانز نيكولاس إيزنهاور من كارلزسبورن، الذي هاجر إلى لانكستر، پنسلڤانيا عام 1741.[8] كان هانز الجد الأكبر لديڤد ياكوب أيزنهاور (1863–1942)، والد داويت، وكان مهندس، بالرغم من أن والد ياكوب كان يفضل أن تظل العائلة على مهنة الزراعة. كانت والدة أيزونهاور، إيدا إليزابث ستوڤر، قد ولدت في ڤرجينيا لعائلة من أصول لوثرية ألمانية، انتقلت إلى كنساس من ڤرجينيا. تزوجت ديڤد في 23 سبتمبر 1885، في لكومپتون، كنساس، في حرم جامعة لان. كان ديڤد يمتلك متجر عام في هوپ، كنساس، لكنه تعثر في عمله لظروف اقتصادية وأصبحت العائلة فقيرة. بعدها انتقلت عائلة أيزنهاور إلى تكساس حيث عاشت من 1889 إلى 1892، ثم عادت مرة أخرى إلى كنساس، حيث كان عائد العائلة 24 دولار شهرياً؛ عمل ديڤد ميكانيكي في السكك الحديدية، ثم في معمل قشدة.[9] في عام 1898، أصبح دخل العائلة كافياً ونجحت في تدبير مكان لائق لمعيشة العائلة الكبيرة.[10]

وُلد أيزنهاور في 14 أكتوبر 1890، في دنيسون، تكساس، وكان ثالث أولاد العائلة السبعة.[11] في الأصل أسمته والدته ديڤد دوايت لكنها عكست اسمه بعد ميلاده لتجنب الخلط بينه وبين أشخاص آخرين يحملون اسم ديڤد في العائلة.[12] كان جميع الصبية يطلق عليهم اسم "إيك"، مثل "إيك الكبير" (إدجار) و"إيك الصغير" (دوايت)؛ وكان اسم التدليل اختصار للاسم الأخير.[13] عند قيام الحرب العالمية الثانية، كان دوايت فقد هو من يحمل اسم "إيك".[6] عام 1892، انتقلت العائلة إلى أبيلن، كنساس، التي يعتبرها أيزنهاور بلدته الأم.[6] أثناء طفولته، وقع حادث أسفر عن فقدان شقيقه الأصغر عينه؛ فيما بعد أشار أيزنهاور للحادث على أنها خبرة علمته وجوب حماية من هم أصغر منه. انصب اهتمام دوايت على الخروج للاستكشاف في الأماكن المفتوحة، الصيد/صيد الأسماك، الطبخ ولعب الورق مع أحد الصبية الأميين الذي يدعى بوب ديڤيز وكانوا يخيمون على ضفاف نهر سموكي هيل.[14][15][16] وبالرغم من أن والدته كانت ضد الحرب، لكن كانت مجموعة الكتب التاريخية الخاصة بها أول ما لفت انتباه أيزنهاور ونمنى اهتمامه بالتاريخ العسكري. واستمر في قراءة كتبها وأصبح قارئ شره للتاريخ العسكري. المواد التعليمية الأخرى المفضلة لديه كانت الحساب والتهجي.[17]

خصص والديه مواعيداً محددة للإفطار والعشاء وقراءة العائلة للكتاب المقدس. وكان الأطفال ينتاوبون العمل بينهم بانتظام، وكان السلوك الغير منضبط دائماً ما يصدر عن ديڤد[18] والدته، كانت عضوة (مع ديڤد) في طائفة بريڤر برثرن المارونية، والتحقت لاتحاد الطلاب الدوليين للكتاب المقدس، الذي أصبح فيما بعد Jehovah's Witnesses. كان منزل أيزنهاور يستخدم كقاعة لعقد اللقاء المحلي من 1896 حتى 1915، على الرغم من أن أيزنهاور لم يكن أبداً من أعضاء الطلاب الدوليين للكتاب المقدس.[19] تسبب قراره بالالتحاق بوست پوينت بشعور والدته بالحزن، التي كانت تشعر بأن "أكثر شراً" لكنها لم تعارضه.[20] وهو يتحدث مع نفسه عام 1948، كان أيزنهاور يقول "كان من أكثر الرجال الذين عرفتهم تدينياً" على الرغم من أنه لم ينتمي لأي "طائفة أو تنظيم". كان قد عُمد في كنيسة المشيخية عام 1953.[21]

التحق أيزنهاور بثانوية أبيلن وتخرج منها عام 1909.[22] وهو شاب، أصيبت ركبته وتطور المرض إلى عدوى من الساق إلى الفخذ وشخصها طبيبه على أنها خطر على حياته؛ أصر الطبيب على بتر ساقه لكن دوايت رفض السماح له بذلك، وتعافى بمعجزة.[23] أراد هو وشقيقه إدجار الالتحاق بالكلية، على الرغم من عدم امتلاكهم الأموال الكافية. اتفقا على أن يدرس أحدهما سنة في الكلية بينما يعمل الآخر، لتغطية نفقات التعليم.[24] درس إدجار السنة الأولى بالكلية بينما عمل دوايت كمشرف مسائي في معمل بل سپرينج للقشدة.[25] طلب إدجار االدراسة في العام التالي، فوافق دوايت وعمل للسنة الثانية. في ذلك الوقت، كان صديقه هازلت يقدم طلب الالتحاق بالأكاديمية البحرية وشجع دوايت على التقدم أيضاً، وكان دوايت لا يملك النفقات المطلوبة. طلب أيزنهاور الالتحااق بفرع الأكاديمية في أناپوليس أو وست پوينت، مع السناتور الأمريكي جوسف ل. بريستاو. وكان أيزنهاور من ضمن الناجين في اختبار القبول.[26] ثم تم تعيينه في وست پوينت عام 1911.[26]

في وست پوينت، اسمتع أيزنهاور بالتركيز على التقاليد والرياضات، لكنه كان كان أقل اهتماماً بالمقالب، وكان يقبلها على أنها مداعبة؛ وكان أيضاً يخالف اللوائح العادية، وأنهى دراسته وتصنيفه أقل من ممتاز فيما يخص الانضباط. أكاديمياً، كان أفضل المواد لدى أيزنهاور هي اللغة الإنگليزية؛ غير أن آداؤه كان متوسط، ومع ذلك فقد كان يتمتع بتركيز عالي في الهندسة والعلوم والرياضيات.[27] في ألعاب القوى، قال أيزنهاور فيما بعد "كان عدم تشكيل فريق بيسبول في وست پوينت من أعظم الأمور المخيبة للآمال في حياتي، وقد تكون أعظمها."[28] اشترك أيزنهاور في فريق كرة القدم عام 1912.[29]

تخرج من الصف المتوسط عام 1915،[30] الذي سمي فيما بعد "فصل النجوم المستاقطة"، لأنها طلابه ال59 أصبحوا جنرالات.

حياته الشخصية

إلتقى أيزنهاور وارتبط عاطفياً مع مامي جنـِڤا دود من بون، أيوا، وكانت تصغره بست سنوات، عندما ارتبط بها في تكساس.[6] وسرعان ما تقبلته عائلتها. وتقدم لطلب يدها في عيد الحب 1916.[31] كان يوم الزفاف مقرر عقده في نوفمبر في دنڤر ونُقل إلى 1 يوليو بدخول الولايات المتحدة الحرب العالمية الأولى. في الخمسة وثلاثين الأولى من زواجهم، تنقلت العائلة عدة مرات.[32]

لأيزنهاور ابنان. دود دوايت "إكي" أيزنهاور وُلد في 24 سبتمبر 1917، وتوفى بالحمى القرمزية في 2 يناير 1921، وهو في عامه الثالث؛[33] وكان أيزنهاور غالباً ما يتحغظ في مناقشة موضوع وفاته.[34] ابنهم الثاني جون شلدون دود أيزنهاور، وُلد في 3 أغسطس 1922، أثناء وجودهم في پنما، وعمل جون في الجيش الأمريكي، وتقاعد برتبة جرنال، وأصبح مؤلف وعمل السفير الأمريكي في بلجيكا من 1968 حتى 1971. جون، من قبيل المصادفة، تخرج من وست پوينت في 6 يونيو 1944. تزوج بربرا جين ثومپسون، في 10 يونيو 1947. جون وبربرا أنجبا أربع أبناء: دوايت ديڤد الثاني "ديڤد"، بربرا أن، سوزان إليان، وماري جين. ديڤد، الذي سمي على اسمه كامپ ديڤد، تزوج من جولي ابنة ريتشارد نيكسو عام 1968.

العمل العسكري المبكر

الحرب العالمية الأولى

في خدمة الجنرالات

الحرب العالمية الثانية (1939–1945)

بعد الهجوم الياباني على پيرل هاربر، تم تعيين أيزنهاور في هيئة الأركان العامة في واشنطن، حيث خدم حتى يونيو 1942 بمسؤولية وضع الخطط الحربية الرئيسية لهزيمة اليابان و ألمانيا. تم تعيينه نائب للرئيس المسؤول عن دفاعات المحيط الهادئ تحت قيادة رئيس قسم خطط الحرب (WPD)، الجنرال ليونارد جيرو ، ثم خلف جيرو كرئيس لقسم خطط الحرب. بعد ذلك، تم تعيينه مساعد لرئيس الأركان المسؤول عن قسم العمليات الجديد (الذي حل محل WPD) تحت قيادة رئيس الأركان الجنرال جورج مارشال، الذي اكتشف المواهب وتم ترقيته وفقًا لذلك.[35]

في نهاية مايو 1942، رافق أيزنهاور اللفتنانت جنرال هنري أرنولد، القائد العام للقوات الجوية للجيش، إلى لندن لتقييم فعالية قائد المسرح في إنجلترا، اللواء جيمس تشاني.[36] عاد إلى واشنطن في 3 يونيو بتقييم متشائم، قائلاً إن لديه "شعور بعدم الارتياح" تجاه تشاني وموظفيه. في 23 يونيو 1942، عاد إلى لندن كقائد عام المسرح الأوروبي للعمليات (ETOUSA)، ومقره في لندن ولديه منزل في كومب، كينجستون أبون تيمز،[37] وتولى قيادة ETOUSA من تشاني.[38] تمت ترقيته إلى رتبة فريق في 7 يوليو.

عملية الشعلة وأڤلانش

في نوفمبر 1942، عُين أيزنهاور أيضًا القائد الأعلى لقوات الحلفاء في مسرح عمليات شمال أفريقيا (NATOUSA) من خلال مقر العمليات الجديد مقرات قوات الحلفاءالجديد. أُسقطت كلمة "التجريدة" بعد فترة وجيزة من تعيينه لأسباب أمنية.[المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك] عُينت الحملة في شمال أفريقيا باسم عملية الشعلة وتم التخطيط لها في المقرات تحت الأرض داخل صخرة جبل طارق. كان أيزنهاور أول شخص غير بريطاني يتولى قيادة جبل طارق منذ 200 عاماً.[39]

أُعتبر التعاون الفرنسي ضروريًا للحملة وواجه أيزنهاور "موقفاً غير معقولاً"[حسب من؟] مع الفصائل المتنافسة المتعددة في فرنسا. كان هدفه الأساسي هو نقل القوات بنجاح إلى تونس وقصد تسهيل هذا الهدف، فقد قدم دعمه فرانسوا دارلانلفرانسوا دارلان بصفته المفوض السامي في شمال أفريقيا، على الرغم من المناصب العليا السابقة التي شغلها دارلان في فرنسا ڤيشي ودوره المستمر كقائد أعلى للقوات المسلحة الفرنسية. أصيب قادة الحلفاء بالذهول[حسب من؟] من وجهة النظر السياسية هذه، على الرغم من أن أياً منهم لم يقدم أي إرشادات لأيزنهاور بشأن المشكلة أثناء التخطيط للعملية. وتعرض أيزنهاور لانتقادات شديدة[ممن؟] من أجل هذا التحرك. وفي 24 ديسمبر أُغتيل دارلان على يد الملكي الفرنسي المناهض للفاشية فرناند بونييه دي لا شاپل.[40] قام أيزنهاور لاحقاً بتعيين المفوض السامي، الجنرال هنري جيرو، الذي عينه الحلفاء كقائد أعلى لدارلان.[41]

كانت عملية الشعلة أيضًا بمثابة ساحة تدريب قيمة لمهارات القيادة القتالية لأيزنهاور. أثناء المرحلة الأولى من تحرك الجنرال فيلدمارشال إرڤن رومل إلى ممر القصرين، خلق أيزنهاور بعض الارتباك في الرتب من خلال التدخل في تنفيذ بعض خطط المعركة من قبل مرؤوسيه. كما أنه كان غير حاسم في البداية في إقالة لويد فردندال، قائد الفيلق الثاني الأمريكي. أصبح أيزنهاور أكثر براعة في مثل هذه الأمور في الحملات اللاحقة.[42] في فبراير 1943، تم توسيع سلطته كقائد للقيادة المركزية عبر حوض المتوسط لتشمل الجيش الثامن البريطاني، بقيادة الجنرال برنارد مونتگومري. كان الجيش الثامن قد تقدم عبر الصحراء الغربية من الشرق وكان جاهزًا لبدء حملة تونس. حصل أيزنهاور على النجمة الرابعة وتخلى عن قيادة مسرح العمليات الأوروپي (ETOUSA) ليصبح قائد مسرح عمليات شمال أفريقيا (NATOUSA).

بعد استسلام قوى المحور في شمال أفريقيا، أشرف أيزنهاور على غزو صقلية. بمجرد سقوط الزعيم الإيطالي موسوليني، في إيطاليا، حول الحلفاء انتباههم إلى البر الرئيسي مع عملية الانهيار الجليدي. لكن بينما كان أيزنهاور يتجادل مع الرئيس روزڤلت ورئيس الوزراء البريطاني تشرشل، اللذين أصر كلاهما على استسلام غير مشروط مقابل مساعدة الإيطاليين، واصل الألمان حشدًا عدوانيًا لقواتهم في البلاد. جعل الألمان المعركة الصعبة أكثر صعوبة بالفعل بإضافة 19 فرقة وتفوق عددهم في البداية على قوات الحلفاء بنسبة 2 إلى 1.[43]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

القائد الأعلى لقوات الحلفاء والعملية أوڤرلود

In December 1943, President Roosevelt decided that Eisenhower – not Marshall – would be Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. The following month, he resumed command of ETOUSA and the following month was officially designated as the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), serving in a dual role until the end of hostilities in Europe in May 1945.[44] He was charged in these positions with planning and carrying out the Allied assault on the coast of Normandy in June 1944 under the code name Operation Overlord, the liberation of Western Europe and the invasion of Germany.

Eisenhower, as well as the officers and troops under him, had learned valuable lessons in their previous operations, and their skills had all strengthened in preparation for the next most difficult campaign against the Germans—a beach landing assault. His first struggles, however, were with Allied leaders and officers on matters vital to the success of the Normandy invasion; he argued with Roosevelt over an essential agreement with De Gaulle to use French resistance forces in covert and sabotage operations against the Germans in advance of Operation Overlord.[45] Admiral Ernest J. King fought with Eisenhower over King's refusal to provide additional landing craft from the Pacific.[46] Eisenhower also insisted that the British give him exclusive command over all strategic air forces to facilitate Overlord, to the point of threatening to resign unless Churchill relented, which he did.[47] Eisenhower then designed a bombing plan in France in advance of Overlord and argued with Churchill over the latter's concern with civilian casualties; de Gaulle interjected that the casualties were justified in shedding the yoke of the Germans, and Eisenhower prevailed.[48] He also had to skillfully manage to retain the services of the often unruly George S. Patton, by severely reprimanding him when Patton earlier had slapped a subordinate, and then when Patton gave a speech in which he made improper comments about postwar policy.[49]

The D-Day Normandy landings on June 6, 1944, were costly but successful. Two months later (August 15), the invasion of Southern France took place, and control of forces in the southern invasion passed from the AFHQ to the SHAEF. Many thought that victory in Europe would come by summer's end, but the Germans did not capitulate for almost a year. From then until the end of the war in Europe on May 8, 1945, Eisenhower, through SHAEF, commanded all Allied forces, and through his command of ETOUSA had administrative command of all U.S. forces on the Western Front north of the Alps. He was ever mindful of the inevitable loss of life and suffering that would be experienced on an individual level by the troops under his command and their families. This prompted him to make a point of visiting every division involved in the invasion.[50] Eisenhower's sense of responsibility was underscored by his draft of a statement to be issued if the invasion failed. It has been called one of the great speeches of history:

Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.[51]

تحرير فرنسا والانتصار في اوروپا

Once the coastal assault had succeeded, Eisenhower insisted on retaining personal control over the land battle strategy, and was immersed in the command and supply of multiple assaults through France on Germany. Field Marshal Montgomery insisted priority be given to his 21st Army Group's attack being made in the north, while Generals Bradley (12th U.S. Army Group) and Devers (Sixth U.S. Army Group) insisted they be given priority in the center and south of the front (respectively). Eisenhower worked tirelessly to address the demands of the rival commanders to optimize Allied forces, often by giving them tactical latitude; many historians conclude this delayed the Allied victory in Europe. However, due to Eisenhower's persistence, the pivotal supply port at Antwerp was successfully, albeit belatedly, opened in late 1944.[52]

In recognition of his senior position in the Allied command, on December 20, 1944, he was promoted to General of the Army, equivalent to the rank of Field Marshal in most European armies. In this and the previous high commands he held, Eisenhower showed his great talents for leadership and diplomacy. Although he had never seen action himself, he won the respect of front-line commanders. He interacted adeptly with allies such as Winston Churchill, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery and General Charles de Gaulle. He had serious disagreements with Churchill and Montgomery over questions of strategy, but these rarely upset his relationships with them. He dealt with Soviet Marshal Zhukov, his Russian counterpart, and they became good friends.[53]

In December 1944, the Germans launched a surprise counteroffensive, the Battle of the Bulge, which the Allies turned back in early 1945 after Eisenhower repositioned his armies and improved weather allowed the Army Air Force to engage.[54] German defenses continued to deteriorate on both the Eastern Front with the Red Army and the Western Front with the Western Allies. The British wanted to capture Berlin, but Eisenhower decided it would be a military mistake for him to attack Berlin, and said orders to that effect would have to be explicit. The British backed down but then wanted Eisenhower to move into Czechoslovakia for political reasons. Washington refused to support Churchill's plan to use Eisenhower's army for political maneuvers against Moscow. The actual division of Germany followed the lines that Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin had previously agreed upon. The Soviet Red Army captured Berlin in a very large-scale bloody battle, and the Germans finally surrendered on May 7, 1945.[55]

In 1945, Eisenhower anticipated that someday an attempt would be made to recharacterize Nazi crimes as propaganda (Holocaust denial) and took steps against it by demanding extensive still and movie photographic documentation of Nazi death camps.[56]

بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية (1945–1953)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الحاكم العسكري في ألمانيا والقائد الأعلى للجيش

Following the German unconditional surrender, Eisenhower was appointed military governor of the American occupation zone, located primarily in Southern Germany, and headquartered at the IG Farben Building in Frankfurt am Main. Upon discovery of the Nazi concentration camps, he ordered camera crews to document evidence of the atrocities in them for use in the Nuremberg Trials. He reclassified German prisoners of war (POWs) in U.S. custody as Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs), who were no longer subject to the Geneva Convention. Eisenhower followed the orders laid down by the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in directive JCS 1067 but softened them by bringing in 400,000 tons of food for civilians and allowing more fraternization.[57][58][59] In response to the devastation in Germany, including food shortages and an influx of refugees, he arranged distribution of American food and medical equipment.[60] His actions reflected the new American attitudes of the German people as Nazi victims not villains, while aggressively purging the ex-Nazis.[61][62]

In November 1945, Eisenhower returned to Washington to replace Marshall as Chief of Staff of the Army. His main role was the rapid demobilization of millions of soldiers, a job that was delayed by lack of shipping. Eisenhower was convinced in 1946 that the Soviet Union did not want war and that friendly relations could be maintained; he strongly supported the new United Nations and favored its involvement in the control of atomic bombs. However, in formulating policies regarding the atomic bomb and relations with the Soviets, Truman was guided by the U.S. State Department and ignored Eisenhower and the Pentagon. Indeed, Eisenhower had opposed the use of the atomic bomb against the Japanese, writing, "First, the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn't necessary to hit them with that awful thing. Second, I hated to see our country be the first to use such a weapon."[63] Initially, Eisenhower hoped for cooperation with the Soviets.[64] He even visited Warsaw in 1945. Invited by Bolesław Bierut and decorated with the highest military decoration, he was shocked by the scale of destruction in the city.[65] However, by mid-1947, as east–west tensions over economic recovery in Germany and the Greek Civil War escalated, Eisenhower agreed with a containment policy to stop Soviet expansion.[64]

الانتخابات الرئاسية 1948

In June 1943, a visiting politician had suggested to Eisenhower that he might become President of the United States after the war. Believing that a general should not participate in politics, Merlo J. Pusey wrote that "figuratively speaking, [Eisenhower] kicked his political-minded visitor out of his office". As others asked him about his political future, Eisenhower told one that he could not imagine wanting to be considered for any political job "from dogcatcher to Grand High Supreme King of the Universe", and another that he could not serve as Army Chief of Staff if others believed he had political ambitions. In 1945, Truman told Eisenhower during the Potsdam Conference that if desired, the president would help the general win the 1948 election,[66] and in 1947 he offered to run as Eisenhower's running mate on the Democratic ticket if MacArthur won the Republican nomination.[67]

As the election approached, other prominent citizens and politicians from both parties urged Eisenhower to run for president. In January 1948, after learning of plans in New Hampshire to elect delegates supporting him for the forthcoming Republican National Convention, Eisenhower stated through the Army that he was "not available for and could not accept nomination to high political office"; "life-long professional soldiers", he wrote, "in the absence of some obvious and overriding reason, [should] abstain from seeking high political office".[66] Eisenhower maintained no political party affiliation during this time. Many believed he was forgoing his only opportunity to be president as Republican Thomas E. Dewey was considered the probable winner and would presumably serve two terms, meaning that Eisenhower, at age 66 in 1956, would be too old to have another chance to run.[68]

رئيس جامعة كلومبيا والقائد الأعلى للناتو

عام 1948، أصبح أيزنهاور رئيسًا لجامعة كلومبيا، إحدى جامعات رابطة اللبلاب في مدينة نيويورك، حيث أُلحق عضواً في جمعية فاي بيتا كاپا.[69] وُصف الاختيار لاحقًا بأنه لم يكن مناسبًا لأي من الطرفين.[70] خلال تلك السنة، نُشرت مذكرات أيزنهاور، الحملة الصليبية في أوروپا.[71] واعتبرها النقاد واحدة من أفضل المذكرات العسكرية الأمريكية،[بحاجة لمصدر] وحققت نجاحًا ماليًا كبيرًا أيضًا.[72] طلب أيزنهاور مشورة روبرتس من أوگوستا ناشيونال حول التداعيات الضريبية المترتبة على ذلك،[72] وفي الوقت المناسب، كان ربح أيزنهاور من الكتاب مدعومًا بشكل كبير بما يسميه المؤلف ديڤد پيتروسزا "حكمًا لم يسبق له مثيل" من قبل وزارة الخزانة الأمريكية. التي اعتبرت أن أيزنهاور لم يكن كاتبًا محترفًا، بل كان يقوم بتسويق أصول تجاربه مدى الحياة، وبالتالي كان عليه أن يدفع فقط ضريبة أرباح رأس المال البالغة 635.000 دولار بدلاً من معدل الضريبة الشخصية الأعلى بكثير. وقد وفر هذا الحكم لأيزنهاور حوالي 400.000 دولار.[73]

تخللت فترة ولاية أيزنهاور كرئيس لجامعة كلومبيا نشاطه داخل مجلس العلاقات الخارجية، وهي مجموعة دراسة قادها كرئيس فيما يتعلق بالآثار السياسية والعسكرية بخطة مارشال، والجمعية الأمريكية، كانت رؤية أيزنهاور هي "مركز ثقافي عظيم حيث يمكن لقادة الأعمال والمهنيين والحكوميين أن يجتمعوا من وقت لآخر لمناقشة المشاكل ذات الطبيعة الاجتماعية والسياسية والتوصل إلى استنتاجات بشأنها".[74] اقترح كاتب سيرته الذاتية بلانش ويسن كوك أن هذه الفترة كانت بمثابة "التعليم السياسي للجنرال أيزنهاور"، حيث كان عليه إعطاء الأولوية لمجموعة واسعة من المتطلبات التعليمية والإدارية والمالية للجامعة.[75] ومن خلال مشاركته في مجلس العلاقات الخارجية، اكتسب أيضًا تعرضًا للتحليل الاقتصادي، والذي سيصبح حجر الأساس لفهمه في السياسة الاقتصادية. وقال أحد أعضاء منظمة المعونة لأوروپا: "كل ما يعرفه الجنرال أيزنهاور عن الاقتصاد، قد تعلمه في اجتماعات مجموعة الدراسة".[76]

قبل أيزنهاور رئاسة الجامعة لتوسيع قدرته على تعزيز "النموذج الأمريكي للديمقراطية" من خلال التعليم.[77] لقد كان أيزنهاور واضحًا بشأن هذه النقطة للأمناء المشاركين في لجنة البحث، وأخبرهم أن هدفه الرئيسي هو "تعزيز المفاهيم الأساسية للتعليم في ظل الديمقراطية".[77] نتيجة لذلك، كان مكرسًا وقته "بشكل متواصل تقريبًا" لفكرة الجمعية الأمريكية، وهو المفهوم الذي طوره ليصبح مؤسسة بحلول نهاية عام 1950.[74]

في غضون أشهر من بداية فترة عمله كرئيس للجامعة، طُلب من أيزنهاور تقديم المشورة لوزير الدفاع الأمريكي جيمس فورستال بشأن توحيد الخدمات المسلحة.[78] وبعد حوالي ستة أشهر من تعيينه، أصبح رئيس هيئة الأركان المشتركة غير الرسمي في واشنطن.[79] وبعد شهرين أصيب بمرض تم تشخيصه على أنه نزلة معوية حادة، وأمضى أكثر من شهر للتعافي في نادي أوگستا الوطني للگولف.[80] عاد إلى منصبه في نيويورك في منتصف مايو، وفي يوليو 1949 أخذ إجازة لمدة شهرين خارج الولاية.[81] نظرًا لأن الجمعية الأمريكية قد بدأت في التبلور، فقد سافر في جميع أنحاء البلاد خلال صيف وخريف عام 1950، وقام بجمع الدعم المالي لها من مصادر مختلفة، بما في ذلك من كلومبيا أسوشيتس، وهي منظمة للخريجين والمتبرعين تأسست مؤخرًا والتي ساعد في جمع أعضائها.[82]

كان أيزنهاور يبني دون قصد الاستياء والسمعة بين أعضاء هيئة التدريس والموظفين في جامعة كوومبيا كرئيس غير متواجد يستخدم الجامعة لمصالحه الخاصة. كرجل عسكري محترف، لم يكن لديه بطبيعة الحال سوى القليل من القواسم المشتركة مع الأكاديميين.[83]

حقق أيزنهاور بعض النجاحات في كولومبيا. بينما كان أيزنهاور يتساءل لماذا لم تقم أي جامعة أمريكية "بالدراسة المستمرة لأسباب الحرب وسلوكها وعواقبها"،[84] تولى تأسيس معهد دراسات الحرب والسلام، وهو منشأة بحثية كان هدفها "دراسة الحرب كظاهرة اجتماعية مأساوية".[85] كان أيزنهاور قادرًا على استخدام شبكته من الأصدقاء والمعارف الأثرياء لتأمين التمويل الأولي للمعهد.[86] بدأ المعهد في عهد مديره المؤسس، الباحث في العلاقات الدولية وليام فوكس، عام 1951 وأصبح رائدًا في دراسات الأمن الدولي، وهي الدراسة التي ستقتدي بها معاهد أخرى في الولايات المتحدة وبريطانيا لاحقاً.[84] وهكذا أصبح معهد دراسات الحرب والسلام أحد المشاريع التي اعتبرها أيزنهاور أنها تشكل "مساهمته الفريدة" في كلومبيا.[85]

أصبحت الاتصالات المكتسبة من خلال الجامعات وأنشطة جمع الأموال للجمعية الأمريكية لاحقاً دعامة هامة في محاولة أيزنهاور للحصول على ترشيح الحزب الجمهوري والرئاسة. في هذه الأثناء، أصبح أعضاء هيئة التدريس الليبراليون في جامعة كلومبيا محبطين من علاقات رئيس الجامعة برجال النفط ورجال الأعمال، بما في ذلك ليونارد مكولوم، رئيس كونتيننتال أويل؛ فرانك أبرامز، رئيس مجلس إدارة ستاندرد أويل نيوجرزي؛ بوب كلبرگ، رئيس كنگ رانش؛ هـ. ج. پورتر، مسؤول تنفيذي في قطاع النفط بتكساس؛ بوب وودروف، رئيس كوكا كولا؛ وكلارنس فرانسس، رئيس مجلس إدارة جنرال فودز.

بصفته رئيسًا لجامعة كلومبيا، أعطى أيزنهاور صوتًا وشكلًا لآرائه حول سيادة الديمقراطية الأمريكية والصعوبات التي تواجهها. تميزت فترة ولايته بتحوله من القيادة العسكرية إلى القيادة المدنية. كما أشار كاتب سيرته الذاتية، تراڤيس بيل جاكوبس، إلى أن اغتراب أعضاء هيئة التدريس بجامعة كلومبيا ساهم في توجيه انتقادات فكرية حادة له لسنوات عديدة.[87]

رفض أمناء جامعة كلومبيا قبول عرض أيزنهاور بالاستقالة في ديسمبر 1950، عندما أخذ إجازة طويلة من الجامعة ليصبح القائد الأعلى لحلف شمال الأطلسي (الناتو)، ومُنح قيادة عمليات لقوات الناتو في أوروپا.[88]

تقاعد أيزنهاور من الخدمة الفعلية كجنرال بالجيش في 3 يونيو 1952،[89] واستأنف رئاسته لجامعة كلومبيا. وفي الوقت نفسه، أصبح أيزنهاور مرشح الحزب الجمهوري لمنصب رئيس الولايات المتحدة، وهي المنافسة التي فاز بها في 4 نوفمبر. قدم أيزنهاور استقالته من منصب رئيس الجامعة في 15 نوفمبر 1952، ودخلت حيز التنفيذ اعتبارًا من 19 يناير 1953، في اليوم السابق لتنصيبه رئيساً.[90]

في الوقت الذي تولى فيه أيزنهاور قيادته العسكرية لم يكن الناتو يحظى بدعم قوي من الحزبين في الكونگرس. نصح أيزنهاور الدول الأوروپية المشاركة بأنه سيكون لزامًا عليهم إظهار التزامهم بالقوات والمعدات لقوة الناتو قبل أن يأتي ذلك من الولايات المتحدة التي أنهكتها الحرب.

في الداخل، كان أيزنهاور أكثر فعالية في الدفاع عن الناتو أمام الكونگرس مما كانت عليه إدارة ترومان. وبحلول منتصف عام 1951، وبدعم من الولايات المتحدة وأوروپا، أصبح الناتو قوة عسكرية حقيقية. ومع ذلك، رأى أيزنهاور أن الناتو سيصبح تحالفًا أوروپيًا حقيقيًا، مع انتهاء الالتزامات الأمريكية والكندية بعد حوالي عشر سنوات.[91]

حملة الانتخابات الرئاسية 1952

President Truman sensed a broad-based desire for an Eisenhower candidacy for president, and he again pressed him to run for the office as a Democrat in 1951. But Eisenhower voiced his disagreements with the Democrats and declared himself to be a Republican.[92] A "Draft Eisenhower" movement in the Republican Party persuaded him to declare his candidacy in the 1952 presidential election to counter the candidacy of non-interventionist Senator Robert A. Taft. The effort was a long struggle; Eisenhower had to be convinced that political circumstances had created a genuine duty for him to offer himself as a candidate and that there was a mandate from the public for him to be their president. Henry Cabot Lodge and others succeeded in convincing him, and he resigned his command at NATO in June 1952 to campaign full-time.[93]

Eisenhower defeated Taft for the nomination, having won critical delegate votes from Texas. His campaign was noted for the simple slogan "I Like Ike". It was essential to his success that Eisenhower express opposition to Roosevelt's policy at the Yalta Conference and to Truman's policies in Korea and China—matters in which he had once participated.[94][95] In defeating Taft for the nomination, it became necessary for Eisenhower to appease the right-wing Old Guard of the Republican Party; his selection of Richard Nixon as the vice-president on the ticket was designed in part for that purpose. Nixon also provided a strong anti-communist reputation, as well as youth to counter Eisenhower's more advanced age.[96]

Eisenhower insisted on campaigning in the South in the general election, against the advice of his campaign team, refusing to surrender the region to the Democratic Party. The campaign strategy was dubbed "K1C2" and was intended to focus on attacking the Truman administration on three failures: the Korean War, Communism, and corruption.[97]

Two controversies tested him and his staff during the campaign, but they did not damage the campaign. One involved a report that Nixon had improperly received funds from a secret trust. Nixon spoke out adroitly to avoid potential damage, but the matter permanently alienated the two candidates. The second issue centered on Eisenhower's relented decision to confront the controversial methods of Joseph McCarthy on his home turf in a Wisconsin appearance.[98] Just two weeks before the election, Eisenhower vowed to go to Korea and end the war there. He promised to maintain a strong commitment against Communism while avoiding the topic of NATO; finally, he stressed a corruption-free, frugal administration at home.

Eisenhower defeated Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson II in a landslide, with an electoral margin of 442 to 89, marking the first Republican return to the White House in 20 years.[95] He also brought a Republican majority in the House, by eight votes, and in the Senate, evenly divided with Vice President Nixon providing Republicans the majority.[99]

Eisenhower was the last president born in the 19th century, and he was the oldest president-elect at age 62 since James Buchanan in 1856.[100] He was the third commanding general of the Army to serve as president, after George Washington and Ulysses S. Grant, and the last not to have held political office prior to becoming president until Donald Trump entered office in January 2017.[101]

Election of 1956

The United States presidential election of 1956 was held on November 6, 1956. Eisenhower, the popular incumbent, successfully ran for re-election. The election was a re-match of 1952, as his opponent in 1956 was Stevenson, a former Illinois governor, whom Eisenhower had defeated four years earlier. Compared to the 1952 election, Eisenhower gained Kentucky, Louisiana, and West Virginia from Stevenson, while losing Missouri. His voters were less likely to bring up his leadership record. Instead what stood out this time, "was the response to personal qualities— to his sincerity, his integrity and sense of duty, his virtue as a family man, his religious devotion, and his sheer likeableness."[102]

الرئاسة (1953–1961)

Truman and Eisenhower had minimal discussions about the transition of administrations due to a complete estrangement between them as a result of campaigning.[103] Eisenhower selected Joseph M. Dodge as his budget director, then asked Herbert Brownell Jr. and Lucius D. Clay to make recommendations for his cabinet appointments. He accepted their recommendations without exception; they included John Foster Dulles and George M. Humphrey with whom he developed his closest relationships, as well as Oveta Culp Hobby. His cabinet consisted of several corporate executives and one labor leader, and one journalist dubbed it "eight millionaires and a plumber".[104] The cabinet was known for its lack of personal friends, office seekers, or experienced government administrators. He also upgraded the role of the National Security Council in planning all phases of the Cold War.[105]

Prior to his inauguration, Eisenhower led a meeting of advisors at Pearl Harbor addressing foremost issues; agreed objectives were to balance the budget during his term, to bring the Korean War to an end, to defend vital interests at lower cost through nuclear deterrent, and to end price and wage controls.[106] He also conducted the first pre-inaugural cabinet meeting in history in late 1952; he used this meeting to articulate his anti-communist Russia policy. His inaugural address was also exclusively devoted to foreign policy and included this same philosophy as well as a commitment to foreign trade and the United Nations.[107]

Eisenhower made greater use of press conferences than any previous president, holding almost 200 over his two terms. He saw the benefit of maintaining a good relationship with the press, and he saw value in them as a means of direct communication with the American people.[108]

Throughout his presidency, Eisenhower adhered to a political philosophy of dynamic conservatism.[109] He described himself as a "progressive conservative"[110] and used terms such as "progressive moderate" and "dynamic conservatism" to describe his approach.[111] He continued all the major New Deal programs still in operation, especially Social Security. He expanded its programs and rolled them into the new Cabinet-level agency of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, while extending benefits to an additional ten million workers. He implemented racial integration in the Armed Services in two years, which had not been completed under Truman.[112]

In a private letter, Eisenhower wrote:

Should any party attempt to abolish social security and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group of course, that believes you can do these things [...] Their number is negligible and they are stupid.[113]

When the 1954 Congressional elections approached, it became evident that the Republicans were in danger of losing their thin majority in both houses. Eisenhower was among those who blamed the Old Guard for the losses, and he took up the charge to stop suspected efforts by the right wing to take control of the GOP. He then articulated his position as a moderate, progressive Republican: "I have just one purpose ... and that is to build up a strong progressive Republican Party in this country. If the right wing wants a fight, they are going to get it ... before I end up, either this Republican Party will reflect progressivism or I won't be with them anymore."[114]

Eisenhower initially planned on serving only one term, but he remained flexible in case leading Republicans wanted him to run again. He was recovering from a heart attack late in September 1955 when he met with his closest advisors to evaluate the GOP's potential candidates; the group concluded that a second term was well advised, and he announced that he would run again in February 1956.[115][116] Eisenhower was publicly noncommittal about having Nixon as the Vice President on his ticket; the question was an especially important one in light of his heart condition. He personally favored Robert B. Anderson, a Democrat who rejected his offer, so Eisenhower resolved to leave the matter in the hands of the party.[117] In 1956, Eisenhower faced Adlai Stevenson again and won by an even larger landslide, with 457 of 531 electoral votes and 57.6-percent of the popular vote. The level of campaigning was curtailed out of health considerations.[118]

Eisenhower made full use of his valet, chauffeur, and secretarial support; he rarely drove or even dialed a phone number. He was an avid fisherman, golfer, painter, and bridge player, and preferred active rather than passive forms of entertainment.[119] On August 26, 1959, he was aboard the maiden flight of Air Force One, which replaced the Columbine as the presidential aircraft.[120]

نظام الطرق السريعة بين الولايات

Text of speech excerpt

هل لديك مشكلة في تشغيل هذا الملف؟ انظر مساعدة الوسائط.

Eisenhower championed and signed the bill that authorized the Interstate Highway System in 1956.[121] He justified the project through the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 as essential to American security during the Cold War. It was believed that large cities would be targets in a possible war, so the highways were designed to facilitate their evacuation and ease military maneuvers.

Eisenhower's goal to create improved highways was influenced by difficulties that he encountered during his involvement in the Army's 1919 Transcontinental Motor Convoy. He was assigned as an observer for the mission, which involved sending a convoy of Army vehicles coast to coast.[122][123] His subsequent experience with the German autobahn limited-access road systems during the concluding stages of World War II convinced him of the benefits of an Interstate Highway System. The system could also be used as a runway for airplanes, which would be beneficial to war efforts. Franklin D. Roosevelt put this system into place with the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944. He thought that an interstate highway system would be beneficial for military operations and would also provide a measure of continued economic growth for the nation.[124] The legislation initially stalled in Congress over the issuance of bonds to finance the project, but the legislative effort was renewed and Eisenhower signed the law in June 1956.[125]

السياسة الخارجية

In 1953, the Republican Party's Old Guard presented Eisenhower with a dilemma by insisting he disavow the Yalta Agreements as beyond the constitutional authority of the Executive Branch; however, the death of Joseph Stalin in March 1953 made the matter a moot point.[126] At this time, Eisenhower gave his Chance for Peace speech in which he attempted, unsuccessfully, to forestall the nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union by suggesting multiple opportunities presented by peaceful uses of nuclear materials. Biographer Stephen Ambrose opined that this was the best speech of Eisenhower's presidency.[127][128] Eisenhower sought to make foreign markets available to American business, saying that it is a "serious and explicit purpose of our foreign policy, the encouragement of a hospitable climate for investment in foreign nations."[129]

Nevertheless, the Cold War escalated during his presidency. When the Soviet Union successfully tested a hydrogen bomb in late November 1955, Eisenhower, against the advice of Dulles, decided to initiate a disarmament proposal to the Soviets. In an attempt to make their refusal more difficult, he proposed that both sides agree to dedicate fissionable material away from weapons toward peaceful uses, such as power generation. This approach was labeled "Atoms for Peace".[130]

The U.N. speech was well received but the Soviets never acted upon it, due to an overarching concern for the greater stockpiles of nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal. Indeed, Eisenhower embarked upon a greater reliance on the use of nuclear weapons, while reducing conventional forces, and with them, the overall defense budget, a policy formulated as a result of Project Solarium and expressed in NSC 162/2. This approach became known as the "New Look", and was initiated with defense cuts in late 1953.[131]

In 1955, American nuclear arms policy became one aimed primarily at arms control as opposed to disarmament. The failure of negotiations over arms until 1955 was due mainly to the refusal of the Russians to permit any sort of inspections. In talks located in London that year, they expressed a willingness to discuss inspections; the tables were then turned on Eisenhower when he responded with an unwillingness on the part of the U.S. to permit inspections. In May of that year, the Russians agreed to sign a treaty giving independence to Austria and paved the way for a Geneva summit with the US, UK and France.[132] At the Geneva Conference, Eisenhower presented a proposal called "Open Skies" to facilitate disarmament, which included plans for Russia and the U.S. to provide mutual access to each other's skies for open surveillance of military infrastructure. Russian leader Nikita Khrushchev dismissed the proposal out of hand.[133]

In 1954, Eisenhower articulated the domino theory in his outlook towards communism in Southeast Asia and also in Central America. He believed that if the communists were allowed to prevail in Vietnam, this would cause a succession of countries to fall to communism, from Laos through Malaysia and Indonesia ultimately to India. Likewise, the fall of Guatemala would end with the fall of neighboring Mexico.[134] That year, the loss of North Vietnam to the communists and the rejection of his proposed European Defence Community (EDC) were serious defeats, but he remained optimistic in his opposition to the spread of communism, saying "Long faces don't win wars".[135] As he had threatened the French in their rejection of EDC, he afterwards moved to restore West Germany as a full NATO partner.[136] In 1954, he also induced Congress to create an Emergency Fund for International Affairs in order to support America's use of cultural diplomacy to strengthen international relations throughout Europe during the cold war.[137][138][139][140][141][142][143]

With Eisenhower's leadership and Dulles' direction, CIA activities increased under the pretense of resisting the spread of communism in poorer countries;[144] the CIA in part deposed the leaders of Iran in Operation Ajax, of Guatemala through Operation Pbsuccess, and possibly the newly independent Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville).[145] Eisenhower authorized the assassination of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba in 1960.[146][147][148] However, the plot to poison him was abandoned.[149][150][151] In 1954, Eisenhower wanted to increase surveillance inside the Soviet Union. With Dulles' recommendation, he authorized the deployment of thirty Lockheed U-2's at a cost of $35 million (equivalent to $302.9 million in 2022).[152] The Eisenhower administration also planned the Bay of Pigs Invasion to overthrow Fidel Castro in Cuba, which John F. Kennedy was left to carry out.[153]

سباق الفضاء

Eisenhower and the CIA had known since at least January 1957, nine months before Sputnik, that Russia had the capability to launch a small payload into orbit and was likely to do so within a year.[154] He may also privately have welcomed the Soviet satellite for its legal implications: By launching a satellite, the Soviet Union had in effect acknowledged that space was open to anyone who could access it, without needing permission from other nations.

On the whole, Eisenhower's support of the nation's fledgling space program was officially modest until the Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957, gaining the Cold War enemy enormous prestige around the world. He then launched a national campaign that funded not just space exploration but a major strengthening of science and higher education. The Eisenhower administration determined to adopt a non-aggressive policy that would allow "space-crafts of any state to overfly all states, a region free of military posturing and launch Earth satellites to explore space".[155] His Open Skies Policy attempted to legitimize illegal Lockheed U-2 flyovers and Project Genetrix while paving the way for spy satellite technology to orbit over sovereign territory,[156] however Nikolai Bulganin and Nikita Khrushchev declined Eisenhower's proposal at the Geneva conference in July 1955.[157] In response to Sputnik being launched in October 1957, Eisenhower created NASA as a civilian space agency in October 1958, signed a landmark science education law, and improved relations with American scientists.[158]

Fear spread through the United States that the Soviet Union would invade and spread communism, so Eisenhower wanted to not only create a surveillance satellite to detect any threats but ballistic missiles that would protect the United States. In strategic terms, it was Eisenhower who devised the American basic strategy of nuclear deterrence based upon the triad of B-52 strategic bombers, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and Polaris submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs).[159]

NASA planners projected that human spaceflight would pull the United States ahead in the Space Race as well as accomplishing their long time goal; however, in 1960, an Ad Hoc Panel on Man-in-Space concluded that "man-in-space can not be justified" and was too costly.[160] Eisenhower later resented the space program and its gargantuan price tag—he was quoted as saying, "Anyone who would spend $40 billion in a race to the moon for national prestige is nuts."[161]

الحرب الكورية، الصين، وتايوان

In late 1952, Eisenhower went to Korea and discovered a military and political stalemate. Once in office, when the Chinese People's Volunteer Army began a buildup in the Kaesong sanctuary, he considered using nuclear weapons if an armistice was not reached. Whether China was informed of the potential for nuclear force is unknown.[162] His earlier military reputation in Europe was effective with the Chinese communists.[163] The National Security Council, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Strategic Air Command (SAC) devised detailed plans for nuclear war against Red China.[164] With the death of Stalin in early March 1953, Russian support for a Chinese communists hard-line weakened and Red China decided to compromise on the prisoner issue.[165]

In July 1953, an armistice took effect with Korea divided along approximately the same boundary as in 1950. The armistice and boundary remain in effect today. The armistice, which concluded despite opposition from Secretary Dulles, South Korean President Syngman Rhee, and also within Eisenhower's party, has been described by biographer Ambrose as the greatest achievement of the administration. Eisenhower had the insight to realize that unlimited war in the nuclear age was unthinkable, and limited war unwinnable.[165]

A point of emphasis in Eisenhower's campaign had been his endorsement of a policy of liberation from communism as opposed to a policy of containment. This remained his preference despite the armistice with Korea.[166] Throughout his terms Eisenhower took a hard-line attitude toward Red China, as demanded by conservative Republicans, with the goal of driving a wedge between Red China and the Soviet Union.[167]

Eisenhower continued Truman's policy of recognizing the Republic of China (Taiwan) as the legitimate government of China, not the Peking (Beijing) regime. There were localized flare-ups when the People's Liberation Army began shelling the islands of Quemoy and Matsu in September 1954. Eisenhower received recommendations embracing every variation of response to the aggression of the Chinese communists. He thought it essential to have every possible option available to him as the crisis unfolded.[168]

The Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty with the Republic of China was signed in December 1954. He requested and secured from Congress their "Free China Resolution" in January 1955, which gave Eisenhower unprecedented power in advance to use military force at any level of his choosing in defense of Free China and the Pescadores. The Resolution bolstered the morale of the Chinese nationalists, and signaled to Beijing that the U.S. was committed to holding the line.[168]

Eisenhower openly threatened the Chinese communists with the use of nuclear weapons, authorizing a series of bomb tests labeled Operation Teapot. Nevertheless, he left the Chinese communists guessing as to the exact nature of his nuclear response. This allowed Eisenhower to accomplish all of his objectives—the end of this communist encroachment, the retention of the Islands by the Chinese nationalists and continued peace.[169] Defense of the Republic of China from an invasion remains a core American policy.[170]

By the end of 1954, Eisenhower's military and foreign policy experts—the NSC, JCS and State Dept.—had unanimously urged him, on no less than five occasions, to launch an atomic attack against Red China; yet he consistently refused to do so and felt a distinct sense of accomplishment in having sufficiently confronted communism while keeping world peace.[171]

Southeast Asia

Early in 1953, the French asked Eisenhower for help in French Indochina against the Communists, supplied from China, who were fighting the First Indochina War. Eisenhower sent Lt. General John W. "Iron Mike" O'Daniel to Vietnam to study and assess the French forces there.[172] Chief of Staff Matthew Ridgway dissuaded the President from intervening by presenting a comprehensive estimate of the massive military deployment that would be necessary. Eisenhower stated prophetically that "this war would absorb our troops by divisions."[173]

Eisenhower did provide France with bombers and non-combat personnel. After a few months with no success by the French, he added other aircraft to drop napalm for clearing purposes. Further requests for assistance from the French were agreed to but only on conditions Eisenhower knew were impossible to meet – allied participation and congressional approval.[174] When the French fortress of Dien Bien Phu fell to the Vietnamese Communists in May 1954, Eisenhower refused to intervene despite urgings from the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, the Vice President and the head of NCS.[175]

Eisenhower responded to the French defeat with the formation of the SEATO (Southeast Asia Treaty Organization) Alliance with the UK, France, New Zealand and Australia in defense of Vietnam against communism. At that time the French and Chinese reconvened the Geneva peace talks; Eisenhower agreed the US would participate only as an observer. After France and the Communists agreed to a partition of Vietnam, Eisenhower rejected the agreement, offering military and economic aid to southern Vietnam.[176] Ambrose argues that Eisenhower, by not participating in the Geneva agreement, had kept the U.S. out of Vietnam; nevertheless, with the formation of SEATO, he had, in the end, put the U.S. back into the conflict.[177]

In late 1954, Gen. J. Lawton Collins was made ambassador to "Free Vietnam" (the term South Vietnam came into use in 1955), effectively elevating the country to sovereign status. Collins' instructions were to support the leader Ngo Dinh Diem in subverting communism, by helping him to build an army and wage a military campaign.[178] In February 1955, Eisenhower dispatched the first American soldiers to Vietnam as military advisors to Diem's army. After Diem announced the formation of the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, commonly known as South Vietnam) in October, Eisenhower immediately recognized the new state and offered military, economic, and technical assistance.[179]

In the years that followed, Eisenhower increased the number of U.S. military advisors in South Vietnam to 900 men.[180] This was due to North Vietnam's support of "uprisings" in the south and concern the nation would fall.[176] In May 1957 Diem, then President of South Vietnam, made a state visit to the United States for ten days. President Eisenhower pledged his continued support, and a parade was held in Diem's honor in New York City. Although Diem was publicly praised, in private Secretary of State John Foster Dulles conceded that Diem had been selected because there were no better alternatives.[181]

After the election of November 1960, Eisenhower, in a briefing with John F. Kennedy, pointed out the communist threat in Southeast Asia as requiring prioritization in the next administration. Eisenhower told Kennedy he considered Laos "the cork in the bottle" with regard to the regional threat.[182]

Legitimation of Francoist Spain

The Pact of Madrid, signed on September 23, 1953, by Francoist Spain and the United States, was a significant effort to break international isolation of Spain after World War II, together with the Concordat of 1953. This development came at a time when other victorious Allies of World War II and much of the rest of the world remained hostile (for the 1946 United Nations condemnation[183] of the Francoist regime, see "Spanish Question") to a fascist regime sympathetic to the cause of the former Axis powers and established with Nazi assistance. This accord took the form of three separate executive agreements that pledged the United States to furnish economic and military aid to Spain. The United States, in turn, was to be permitted to construct and to utilize air and naval bases on Spanish territory (Naval Station Rota, Morón Air Base, Torrejón Air Base and Zaragoza Air Base).

Eisenhower personally visited Spain in December 1959 to meet dictator Francisco Franco and consolidate his international legitimation.

الشرق الأوسط ومبدأ أيزنهاور

.

حتى قبل تنصيبه رئيساً كان أيزنهاور قد وافق على طلب الحكومة البريطانية بعودة الشاه للسلطة. ومن ثم فقد صرح للمخابرات المركزية بمساعدة الجيش الإيراني على الإطاحة برئيس الوزراء محمد مصدق.[184] أدى هذا إلى زيادة التحكم الاستراتيجي للولايات المتحدة والشركات البريطانية بالنفط الإيراني.[185]

العدوان الثلاثي

في نوفمبر 1956، أجبر أيزنهاور القوات البريطانية، الفرنسية والإسرائيلية بإنهاء عدوانها على مصر أثناء أزمة السويس. ولذلك تنصل علناً من تحالفه مع الأمم المتحدة، واستخدم الضغط المالي والدبلوماسي للضغط عليهم للانسحاب من مصر.[186] الجدل الذي أحاط باللقاء السري لأيزنهاور مع هارولد ماكميلان في 25 سبتمبر 1956، قل بعدها لرئيس الوزراء أنطوني إيدن أن أيزنهاور وعد بدعمه للغزو.[187][188] عام 1965 دافع أيزنهاور صراحة في مذكراته عن موقفه المتشدد ضد إسرائيل، بريطانيا وفرنسا.[189]

- الرؤية الأمريكية لأزمة السويس … وكيف غيرت ميزان القوى في الشرق الأوسط

صدرت عن وزارة الخارجية الأمريكية مجموعة مقالات سياسية- تحليلية وتأريخية تتعرض لما أسمته الخارجية بأحداث هامة في علاقات أمريكا الخارجية خلال القرن العشرين، وتحديدا في الفترة الممتدة مابين 1900 و2001. وقد شملت قائمة هذه الأحداث أحداث تاريخية هامة ذات أبعاد دولية إستراتيجية مثل أزمة قناة بنما والحرب الباردة وزيارة نكسون للصين و... أزمة السويس. والأخيرة هي الوحيدة التي تخص منطقة الشرق الأوسط، واختيارها نابع- حسب مؤلف المقالة التي تتناولها- من كونها نقطة تحول هامة في علاقة أمريكا بالمنطقة ومن ثم ما حدث من تغيير في ميزان أو موازين القوي فيها.

عنوان المقالة: أزمة السويس أزمة غيرت ميزان القوي في الشرق الأوسط. وصاحب المقالة هو بيتر هان Peter Hahn أستاذ التاريخ الدبلوماسي في جامعة ولاية أوهايو Ohio State University ويعمل حاليا كمدير تنفيذي لجمعية مؤرخي علاقات أمريكا الخارجية. وهو متخصص في تاريخ أمريكا الدبلوماسي في الشرق الأوسط منذ عام 1948. وقد تناول الكاتب في مقاله ما جرى من أحداث وتطورات في أزمة السويس وكيف تفاقمت الأمور ومن ثم كيف تشكل الرد الأمريكي عليها.

- الرد الأمريكي

لقد عالج الرئيس الأمريكي دوايت أيزنهاور أزمة قناة السويس من خلال مواقف ثلاث أساسية تبناها وعمل بها:

أولا: رغم تعاطف الرئيس الأمريكي دوايت أيزنهاور مع رغبة بريطانيا وفرنسا في استعادة شركة قناة السويس، إلا أنه لم يجادل حول حق مصر في الشركة علي أساس أن مصر ستدفع المقابل المادي لها كما هو مطلوب في القانون الدولي. وأيزنهاور بالتالي سعي للتفادي صدام عسكري وأن يجد للنزاع حول القناة حلا دبلوماسيا قبل أن يستغل الاتحاد السوفيتي الوضع من أجل مكاسب سياسية. من ثم كلف أيزنهاور وزير الخارجية جون فوستر دالاس لفض الأزمة بحلول مقبولة لبريطانيا ولفرنسا من خلال بيانات عامة ومفاوضات ومؤتمرين دوليين في لندن وتأسيس جمعية مستخدمي قناة السويس Suez Canal Users Association (SCUA) بالاضافة الي تشاورات عديدة في الأمم المتحدة. ولكن مع نهاية أكتوبر 1965 تبين أن هذه الأمور لم تكن مجدية واستمرت الاستعدادات الانجلو ـ فرنسية لخوض الحرب.

ثانيا: سعى أيزنهاور إلى تفادي نفور القوميين العرب وإلى استقطاب الزعماء العرب للمشاركة في محاولته الدبلوماسية لانهاء الأزمة. ورفض أيزنهاور مساندة استخدام القوة من جانب بريطانيا وفرنسا ضد مصر كان بسبب ادراكه أن قرار تأميم ناصر لهيئة قناة السويس (والكاتب لا يستخدم تعبير تأميم بل تعبير استيلاء) كان له شعبية واسعة لدى شعبه والشعوب العربية الأخرى. وبلا شك فان زيادة شعبية ناصر قطعت الطريق على جهود كان يبذلها أيزنهاور لإيجاد حل للأزمة بالمشاركة مع زعماء عرب، فالزعماء السعوديون والعراقيون رفضوا اقتراحات أمريكية فيما يخص انتقاد ما فعله ناصر أو تحدي سمعته.

ثالثا: سعى أيزنهاور لعزل اسرائيل من المعضلة التي نشأت ـ أزمة السويس ـ تخوفا من أن مزج النزاعات الإسرائيلية- المصرية والانجلوفرنسية- المصرية سوف تشعل الشرق الأوسط. لذا لم يعط دالاس لإسرائيل الفرصة في المشاركة في التشاورات الدبلوماسية التي تمت لحل الأزمة، ومنع مناقشة شكاوي اسرائيل تجاه سياسة مصر أثناء ما تم طرحه للنقاش في الأمم المتحدة. كما أنه عندما شعر بتزايد رغبة اسرائيل في القتال ضد مصر في شهرى أغسطس وسبتمبر رتب أيزنهاور امداد اسرائيل بكميات محدودة من السلاح من الولايات المتحدة وفرنسا وكندا على أمل تخفيف حدة شعور اسرائيل بعدم الأمان وبالتالي تجنب حرب مصرية ـ اسرائيلية.

مبدأ أيزنهاور

مقالة مفصلة: مبدأ أيزنهاور

مقالة مفصلة: مبدأ أيزنهاور

بعد أزمة السويس أصبحت الولايات المتحدة حامية للحكومة الصديقة الغير مستقرة في الشرق الأوسط بفضل "مبدأ أيزنهاور". والذي وضعه وزير الخارجية دولس. ووضع أيزنهاور من خلاله السياسة العامة للولايات المتحدة في منطقة الشرق الأوسط ووافق عليها الكونجرس في 5 يناير 1957، والتي أطلق عليها مشروع أيزنهاور وتهدف إلي حلول أمريكا لمليء الفراغ الاستعماري بدلاً من إنجلترا وفرنسا وتضمن هذا المشروع:

- تفويض الرئيس الأمريكي سلطة استخدام القوة العسكرية في الحالات التي يراها ضرورية لضمان السلامة الإقليمية، وحماية الاستقلال السياسي لأي دولة، أو مجموعة من الدول في منطقة الشرق الأوسط، إذا ما طلبت هذه الدول مثل هذه المساعدة لمقاومة أي اعتداء عسكري سافر تتعرض له من قبل أي مصدر تسيطر عليه الشيوعية الدولية.

- تفويض الحكومة في تفويض برامج المساعدة العسكرية لأي دولة أو مجموعة من دول المنطقة إذا ما أبدت استعدادها لذلك، وكذلك تفويضها في تقديم العون الاقتصادي اللازم لهذه الدول دعماً لقوتها الاقتصادية وحفاظاً على استقلالها الوطني.

كانت معظم الدول العربية تشكك في "مبدأ أيزنهاور" لأنهم يعتبرون أن "الصهيونية الاستعمارية" هي الخطر الحقيقي. ومع ذلك، فقد استغلوا الفرصة للحصول على المساعدات الاقتصادية والعسكرية. كان الاتحاد السوڤيتي يدعم مصر وسوريا، التي عارضتا مشروع أيزنهاور بقوة في البداية. ومع ذلك، فقد كانت مصر تحصل على مساعدات أمريكية حتى قيام حرب 1967.[190]

بزيادة حدة الحرب الباردة، سعى دولس إلى عزل الاتحاد السوڤيتي عن طريق بناء تحالفات ضده. يطلق بعض النقاد على تلك التحالفات مصطلح "پاكتو-مانيا".[191]

المشرق العربي

وكرد فعل لتداعيات حرب السويس أعلن الرئيس الأمريكي دوايت أيزنهاور ما عرف ب "عقيدة أيزنهاور" “Eisenhower Doctrine” وكانت سياسة أمنية اقليمية جديدة وكبرى أعلنت في بداية عام 1957، وتم اقتراحها وطرحها في يناير 1957 وتم إقرارها من جانب الكونگرس في مارس من العام نفسه. وهذه الوثيقة تتعهد بأن الولايات المتحدة سوف تقوم بتوزيع المساعدة الاقتصادية والعسكرية وإذا اقتضى الأمر تستخدم القوة العسكرية من أجل احتواء الشيوعية في الشرق الأوسط. ولتطبيق تلك الخطة قام المبعوث الرئاسي جيمس ريتشاردز بجولة في المنطقة وزع خلالها عشرات الملايين من الدولارات- كمساعدة اقتصادية وعسكرية لكل من تركيا وإيران وباكستان والعراق والسعودية ولبنان وليبيا.

ويري المؤرخ الأمريكي پيتر هان أن اعلان أيزنهاور حكم سياسة الولايات المتحدة في ثلاث مواقف مثيرة للجدل. في ربيع عام 1957 بعث الرئيس الأمريكي بمساعدة اقتصادية للأردن كما أنه أرسل السفن التابعة للبحرية الأمريكية الى شرق البحر المتوسط لمساعدة العاهل الأردني الملك حسين في مواجهة حركة التمرد بين ضباط الجيش الموالين لمصر. والموقف الثاني كان في أواخر العام نفسه-1957 عندما حث الرئيس أيزنهاور تركيا ودول أخرى صديقة علي الاخد في الاعتبار امكانية غزو سوريا لوقف النظام الراديكالي من استمرار سيطرته علي السلطة.

ثم عندما حدث تمرد عنيف في بغداد في يوليو 1958- كما قال المؤلف- وهدد ذلك بحدوث حركات تمرد مشابهة في لبنان والأردن- فأمر أيزنهاور القوات الأمريكية باحتلال بيروت وبنقل العتاد للقوات البريطانية المحتلة للأردن. هذه الخطوات-غير المسبوقة- في تاريخ السياسة الأمريكية في الدول العربية كشفت اصرار أيزنهاور علي تقبل مسئولية حماية المصالح الغربية في الشرق الأوسط بأي ثمن.

ويرى المؤرخ في نهاية مقاله عن أزمة السويس بأنها تعد حدثا هاما وفاصلا في تاريخ سياسة أمريكا الخارجية. وذلك بقلب وإسقاط الافتراضات التقليدية في الغرب حول الهيمنة الانجلو الفرنسية في الشرق الأوسط، وباستفحال مشاكل القومية الثورية التي تجسدت في ناصر، وبإذكاء نار النزاع العربي-الإسرائيلي وبتهديد السماح للاتحاد السوفيتي بالتسلل داخل المنطقة، فان أزمة قناة السويس سحبت الولايات المتحدة نحو انخراط حقيقي وهام وممتد في منطقة الشرق الأوسط. هذا هو تحديدا ما استنتجه الأكاديمي الأمريكي وهو يلقي نظرة علي حدث هام في علاقة الولايات المتحدة بالعالم الخارجي والعالم العربي بشكل خاص- بعد مرور 50 عاما علي أزمة السويس. ولكن ماذا حدث لهذا الانخراط الأمريكي خاصة في العقد الماضي؟ بالتأكيد توجد أكثر من نظرة عربية لهذا التدخل والتورط الأمريكي، كما أن الموقف العربي أو التفسير والتحليل العربي لما فعلته الولايات المتحدة خلال أزمة السويس لم يظل كم كان- فما حدث من تغيير ملحوظ في علاقة واشنطن بالعالم العربي وبمصر تحديدا وأيضا بإسرائيل، وطبعا بالدول الأوربية- وبريطانيا على وجه التحديد خاصة بعد أن صار الاتحاد السوفيتي في خبر كان. ترى كيف يرى كل طرف من الأطراف المشاركة في أزمة السويس ما حدث- وذلك بعد مرور نصف قرن من الزمان؟!.[192]

افتتاح المركز الإسلامي في واشنطن

مقالة مفصلة: المركز الإسلامي بواشنطن

مقالة مفصلة: المركز الإسلامي بواشنطن

في 28 يونيو 1957، افتتح الرئيس الأمريكي دوايت أيزنهاور المركز الإسلامي في واشنطن. ويعتبر المركز الإسلامي مكانا مثيرا للإعجاب، ويحتل موقعا مرموقاً ضمن المنطقة التي تعرف باسم صف السفارات في قلب العاصمة الأمريكية، ليكون الموقع الرئيس والمتحدث الرسمي باسم الجالية الإسلامية في أمريكا. ومنذ افتتاح المركز أصبح من أكثر المباني المعروفة التي تميز ملامح العاصمة الأمريكية. بني المركز بتبرعات من الجالية المسلمة في أمريكا وبمساهمة من مصر والسعودية وسوريا والعراق وإيران وتركيا وباكستان ودول أخرى. فيما ألقى أيزنهاور كلمة في مراسم افتتاح المركز عبر فيها قائلاً: «إن أمريكا ستناضل بكل ما لديها من قوة دفاعا عن حقكم في أن تكون لكم دار خاصة للعبادة وإقامة الصلاة حسب تعاليم عقيدتكم».[193]

جنوب شرق آسيا

حادث يو-2 1960

On May 1, 1960, a U.S. one-man U-2 spy plane was shot down at high altitude over Soviet airspace. The flight was made to gain photo intelligence before the scheduled opening of an east–west summit conference, which had been scheduled in Paris, 15 days later.[194] Captain Francis Gary Powers had bailed out of his aircraft and was captured after parachuting down onto Russian soil. Four days after Powers disappeared, the Eisenhower Administration had NASA issue a very detailed press release noting that an aircraft had "gone missing" north of Turkey. It speculated that the pilot might have fallen unconscious while the autopilot was still engaged, and falsely claimed that "the pilot reported over the emergency frequency that he was experiencing oxygen difficulties."[195]

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev announced that a "spy-plane" had been shot down but intentionally made no reference to the pilot. As a result, the Eisenhower Administration, thinking the pilot had died in the crash, authorized the release of a cover story claiming that the plane was a "weather research aircraft" which had unintentionally strayed into Soviet airspace after the pilot had radioed "difficulties with his oxygen equipment" while flying over Turkey.[196] The Soviets put Captain Powers on trial and displayed parts of the U-2, which had been recovered almost fully intact.[197]

The Four Power Paris Summit in May 1960 with Eisenhower, Nikita Khrushchev, Harold Macmillan and Charles de Gaulle collapsed because of the incident. Eisenhower refused to accede to Khrushchev's demands that he apologize. Therefore, Khrushchev would not take part in the summit. Up until this event, Eisenhower felt he had been making progress towards better relations with the Soviet Union. Nuclear arms reduction and Berlin were to have been discussed at the summit. Eisenhower stated it had all been ruined because of that "stupid U-2 business".[197]

The affair was an embarrassment for United States prestige. Further, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee held a lengthy inquiry into the U-2 incident.[197] In Russia, Captain Powers made a forced confession and apology. On August 19, 1960, Powers was convicted of espionage and sentenced to imprisonment. On February 10, 1962, Powers was exchanged for Rudolf Abel in Berlin and returned to the U.S.[195]

الحقوق المدنية

While President Truman's 1948 Executive Order 9981 had begun the process of desegregating the Armed Forces, actual implementation had been slow. Eisenhower made clear his stance in his first State of the Union address in February 1953, saying "I propose to use whatever authority exists in the office of the President to end segregation in the District of Columbia, including the Federal Government, and any segregation in the Armed Forces".[198] When he encountered opposition from the services, he used government control of military spending to force the change through, stating "Wherever Federal Funds are expended ..., I do not see how any American can justify ... a discrimination in the expenditure of those funds".[199]

When Robert B. Anderson, Eisenhower's first Secretary of the Navy, argued that the U.S. Navy must recognize the "customs and usages prevailing in certain geographic areas of our country which the Navy had no part in creating," Eisenhower overruled him: "We have not taken and we shall not take a single backward step. There must be no second class citizens in this country."[200]

The administration declared racial discrimination a national security issue, as Communists around the world used the racial discrimination and history of violence in the U.S. as a point of propaganda attack.[201]

Eisenhower told District of Columbia officials to make Washington a model for the rest of the country in integrating black and white public school children.[202][203] He proposed to Congress the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and of 1960 and signed those acts into law. The 1957 act for the first time established a permanent civil rights office inside the Justice Department and a Civil Rights Commission to hear testimony about abuses of voting rights. Although both acts were much weaker than subsequent civil rights legislation, they constituted the first significant civil rights acts since 1875.[204]

In 1957 the state of Arkansas refused to honor a federal court order to integrate their public school system stemming from the Brown decision. Eisenhower demanded that Arkansas governor Orval Faubus obey the court order. When Faubus balked, the president placed the Arkansas National Guard under federal control and sent in the 101st Airborne Division. They escorted and protected nine black students' entry to Little Rock Central High School, an all-white public school, marking the first time since the Reconstruction Era the federal government had used federal troops in the South to enforce the U. S. Constitution.[205] Martin Luther King Jr. wrote to Eisenhower to thank him for his actions, writing "The overwhelming majority of southerners, Negro and white, stand firmly behind your resolute action to restore law and order in Little Rock".[206]

Eisenhower's administration contributed to the McCarthyist Lavender Scare[207] with President Eisenhower issuing Executive Order 10450 in 1953.[208] During Eisenhower's presidency thousands of lesbian and gay applicants were barred from federal employment and over 5,000 federal employees were fired under suspicions of being homosexual.[209][210] From 1947 to 1961 the number of firings based on sexual orientation were far greater than those for membership in the Communist Party,[209] and government officials intentionally campaigned to make "homosexual" synonymous with "Communist traitor" such that LGBT people were treated as a national security threat stemming from the belief they were susceptible to blackmail and exploitation.[211]

علاقته بالكونگرس

Eisenhower had a Republican Congress for only his first two years in office; in the Senate, the Republican majority was by a one-vote margin. Senator Robert A. Taft assisted the President greatly in working with the Old Guard, and was sorely missed when his death (in July 1953) left Eisenhower with his successor William Knowland, whom Eisenhower disliked.[212]

This prevented Eisenhower from openly condemning Joseph McCarthy's highly criticized methods against communism. To facilitate relations with Congress, Eisenhower decided to ignore McCarthy's controversies and thereby deprive them of more energy from the involvement of the White House. This position drew criticism from a number of corners.[213] In late 1953, McCarthy declared on national television that the employment of communists within the government was a menace and would be a pivotal issue in the 1954 Senate elections. Eisenhower was urged to respond directly and specify the various measures he had taken to purge the government of communists.[214]

Among Eisenhower's objectives in not directly confronting McCarthy was to prevent McCarthy from dragging the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) into McCarthy's witch hunt for communists, which might interfere with the AEC's work on hydrogen bombs and other weapons programs.[215][216] In December 1953, Eisenhower learned that one of America's nuclear scientists, J. Robert Oppenheimer, had been accused of being a spy for the Soviet Union.[217] Although Eisenhower never really believed that these allegations were true,[218] in January 1954 he ordered that "a blank wall" be placed between Oppenheimer and all defense-related activities.[219] The Oppenheimer security hearing was conducted later that year, resulting in the physicist losing his security clearance.[220] The matter was controversial at the time and remained so in later years, with Oppenheimer achieving a certain martyrdom.[216] The case would reflect poorly on Eisenhower as well, but the president had never examined it in any detail and had instead relied excessively upon the advice of his subordinates, especially that of AEC chairman Lewis Strauss.[221] Eisenhower later suffered a major political defeat when his nomination of Strauss to be Secretary of Commerce was defeated in the Senate in 1959, in part due to Strauss's role in the Oppenheimer matter.[222]

In May 1955, McCarthy threatened to issue subpoenas to White House personnel. Eisenhower was furious, and issued an order as follows: "It is essential to efficient and effective administration that employees of the Executive Branch be in a position to be completely candid in advising with each other on official matters ... it is not in the public interest that any of their conversations or communications, or any documents or reproductions, concerning such advice be disclosed." This was an unprecedented step by Eisenhower to protect communication beyond the confines of a cabinet meeting, and soon became a tradition known as executive privilege. Eisenhower's denial of McCarthy's access to his staff reduced McCarthy's hearings to rants about trivial matters and contributed to his ultimate downfall.[223]

In early 1954, the Old Guard put forward a constitutional amendment, called the Bricker Amendment, which would curtail international agreements by the Chief Executive, such as the Yalta Agreements. Eisenhower opposed the measure.[224] The Old Guard agreed with Eisenhower on the development and ownership of nuclear reactors by private enterprises, which the Democrats opposed. The President succeeded in getting legislation creating a system of licensure for nuclear plants by the AEC.[225]

The Democrats gained a majority in both houses in the 1954 election.[226] Eisenhower had to work with the Democratic Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson (later U.S. president) in the Senate and Speaker Sam Rayburn in the House, both from Texas. Joe Martin, the Republican Speaker from 1947 to 1949 and again from 1953 to 1955, wrote that Eisenhower "never surrounded himself with assistants who could solve political problems with professional skill. There were exceptions, Leonard W. Hall, for example, who as chairman of the Republican National Committee tried to open the administration's eyes to the political facts of life, with occasional success. However, these exceptions were not enough to right the balance."[227]

Speaker Martin concluded that Eisenhower worked too much through subordinates in dealing with Congress, with results, "often the reverse of what he has desired" because Members of Congress, "resent having some young fellow who was picked up by the White House without ever having been elected to office himself coming around and telling them 'The Chief wants this'. The administration never made use of many Republicans of consequence whose services in one form or another would have been available for the asking."[227]

التعيينات القضائية

المحكمة العليا

قام أيزونهاور بتعيين القضاة التاليون للمحكمة العليا الأمريكية:

- إيرل وارن، 1953 (رئيس القضاة)

- جون مارشال هارلان الثاني، 1954

- وليم ج. برنان، 1956

- تشارلز إڤنز وايتاكر، 1957

- پوتور ستوارت، 1958

Whittaker was unsuited for the role and soon retired (in 1962, after Eisenhower's presidency had ended). Stewart and Harlan were conservative Republicans, while Brennan was a Democrat who became a leading voice for liberalism.[228] In selecting a Chief Justice, Eisenhower looked for an experienced jurist who could appeal to liberals in the party as well as law-and-order conservatives, noting privately that Warren "represents the kind of political, economic, and social thinking that I believe we need on the Supreme Court ... He has a national name for integrity, uprightness, and courage that, again, I believe we need on the Court".[229] In the next few years Warren led the Court in a series of liberal decisions that revolutionized the role of the Court.

محاكم أخرى

بالإضافة إلى التعيينات الخمسة بالمحكمة العليا، قام أيزنهاور بتعيين 45 قاضي في محاكم الاستنئاف بالولايات الأمريكية، و129 قاضي في محاكم المقاطعات الأمريكية.

States admitted to the Union

Two states were admitted to the Union during Eisenhower's presidency.

Health issues

Eisenhower began chain smoking cigarettes at West Point, often three or four packs a day. He joked that he "gave [himself] an order" to stop cold turkey in 1949. But Evan Thomas says the true story was more complex. At first, he removed cigarettes and ashtrays, but that did not work. He told a friend:

- I decided to make a game of the whole business and try to achieve a feeling of some superiority ... So I stuffed cigarettes in every pocket, put them around my office on the desk ... [and] made it a practice to offer a cigarette to anyone who came in ... while mentally reminding myself as I sat down, "I do not have to do what that poor fellow is doing."[230]

He was the first president to release information about his health and medical records while in office, but people around him deliberately misled the public about his health. On September 24, 1955, while vacationing in Colorado, he had a serious heart attack.[231] Dr. Howard Snyder, his personal physician, misdiagnosed the symptoms as indigestion, and failed to call in the help that was urgently needed. Snyder later falsified his own records to cover his blunder and to protect Eisenhower's need to portray he was healthy enough to do his job.[232][233][234]

The heart attack required six weeks' hospitalization, during which time Nixon, Dulles, and Sherman Adams assumed administrative duties and provided communication with the President.[235] He was treated by Dr. Paul Dudley White, a cardiologist with a national reputation, who regularly informed the press of the President's progress. Instead of eliminating him as a candidate for a second term as president, his physician recommended a second term as essential to his recovery.[236]