يوليسيس گرانت Ulysses S. Grant

يوليسيس گرانت | |

|---|---|

Ulysses S. Grant | |

جرانت ح. 1870–1880 | |

| رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 18 | |

| في المنصب 4 مارس 1869 – 4 مارس 1877 | |

| نائب الرئيس |

|

| سبقه | أندرو جونسون |

| خلـَفه | رذرفورد هايز |

| القائد العام لجيش الولايات المتحدة | |

| في المنصب March 9, 1864 – March 4, 1869 | |

| الرئيس |

|

| سبقه | هنري هالك |

| خلـَفه | وليام تكومسه شرمان |

| القائم بأعمال وزير الحربية الأمريكي | |

| في المنصب August 12, 1867 – January 14, 1868 | |

| الرئيس | أندرو جونسون |

| سبقه | Edwin Stanton |

| خلـَفه | Edwin Stanton |

| President of the National Rifle Association | |

| في المنصب 1883–1884[1] | |

| سبقه | E. L. Molineux |

| خلـَفه | Philip Sheridan |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | Hiram Ulysses Grant 27 أبريل 1822 پوينت پليزنت، اوهايو |

| توفي | 23 يوليو 1885 ويلتون، نيويورك |

| القومية | أمريكي |

| الحزب | الجمهوري |

| الزوج | جوليا دنت گرانت |

| الأنجال | جسيه گرانت، يوليسيس گرانت الإبن، نيلي گرانت، فردريك گرانت |

| المدرسة الأم | United States Military Academy at West Point |

| الوظيفة | القائد الأعلى للقوات المسلحة |

| التوقيع | |

| الخدمة العسكرية | |

| الكنية | "استسلام غير مشروط" گرانت |

| الولاء | الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية الاتحاد |

| الفرع/الخدمة | الجيش المتحدة |

| سنوات الخدمة | 1839–1854، 1861–1869 |

| الرتبة | |

| قاد | |

| المعارك/الحروب | |

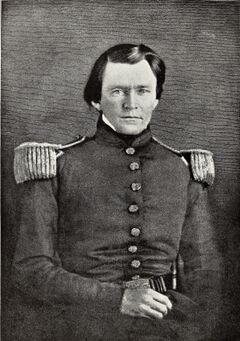

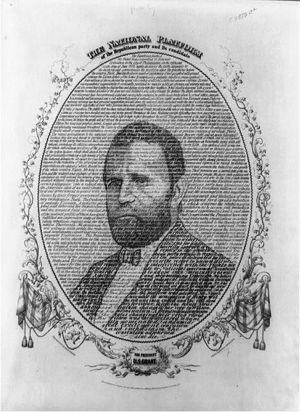

يوليسيس گرانت (ولد Hiram Ulysses Grant[3]) (27 أبريل 1822 - 23 يوليو 1885)، الرئيس الثامن عشر للولايات المتحدة في الفترة من 1869 إلى 1877. في 1865، كالجنرال القائد، قاد گرانت جيش الاتحاد للنصر في الحرب الأهلية الأمريكية.

Grant was born in Ohio and graduated from the United States Military Academy (West Point) in 1843. He served with distinction in the Mexican–American War, but resigned from the army in 1854 and returned to civilian life impoverished. In 1861, shortly after the Civil War began, Grant joined the Union Army and rose to prominence after securing victories in the western theater. In 1863, he led the Vicksburg campaign that gave Union forces control of the Mississippi River and dealt a major strategic blow to the Confederacy. President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general and command of all Union armies after his victory at Chattanooga. For thirteen months, Grant fought Robert E. Lee during the high-casualty Overland Campaign which ended with the capture of Lee's army at Appomattox, where he formally surrendered to Grant. In 1866, President Andrew Johnson promoted Grant to General of the Army. Later, Grant broke with Johnson over Reconstruction policies. A war hero, drawn in by his sense of duty, Grant was unanimously nominated by the Republican Party and then elected president in 1868.

As president, Grant stabilized the post-war national economy, supported congressional Reconstruction and the Fifteenth Amendment, and prosecuted the Ku Klux Klan. Under Grant, the Union was completely restored. An effective civil rights executive, Grant signed a bill to create the United States Department of Justice and worked with Radical Republicans to protect African Americans during Reconstruction. In 1871, he created the first Civil Service Commission, advancing the civil service more than any prior president. Grant was re-elected in the 1872 presidential election, but was inundated by executive scandals during his second term. His response to the Panic of 1873 was ineffective in halting the Long Depression, which contributed to the Democrats winning the House majority in 1874. Grant's Native American policy was to assimilate Indians into Anglo-American culture. In Grant's foreign policy, the Alabama Claims against Britain were peacefully resolved, but the Senate rejected Grant's annexation of Santo Domingo. In the disputed 1876 presidential election, Grant facilitated the approval by Congress of a peaceful compromise.

Leaving office in 1877, Grant undertook a world tour, becoming the first president to circumnavigate the world. In 1880, he was unsuccessful in obtaining the Republican nomination for a third term. In 1885, impoverished and dying of throat cancer, Grant wrote his memoirs, covering his life through the Civil War, which were posthumously published and became a major critical and financial success. At his death, Grant was the most popular American and was memorialized as a symbol of national unity. Due to the pseudohistorical and negationist mythology of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy spread by Confederate sympathizers around the turn of the 20th century, historical assessments and rankings of Grant's presidency suffered considerably before they began recovering in the 21st century. Grant's critics take a negative view of his economic mismanagement and the corruption within his administration, while his admirers emphasize his policy towards Native Americans, vigorous enforcement of civil and voting rights for African Americans, and securing North and South as a single nation within the Union.[4] Modern scholarship has better appreciated Grant's appointments of Cabinet reformers.

الجو الأخلاقي الذي ساد فترة حكم جرانت ، يعتبر أكثر مسئولية عن الفضائح التي ظهرت في هذا العهد من مسئولية الرئيس نفسه . معظم هذه الفضائح كان يمكن أن تظهر بغض النظر عن شخصية الرئيس . السياسة المحافظة التي اتبعتها هذه الإدارة ؛ كانت ناتجة من سيطرة أصحاب العمل على الحكومة الإتحادية ، في الوقت الذي كانت فيه السياسة الخارجية بناءة ، وتسير سيرا حسنا .

النشأة

تطور جرانت من ابن لعائلة مزارعة في الغرب ليصبح بطلا للحرب الأهلية – كان منطقيا يجعل منه مرشحا لرئاسة الجمهورية . لقد بدأ عمله بعد تخرجه من (ويست بوينت) (الكلية الحربية الأمريكية) عام 1843 م . خدم بجدارة في الحرب المكسيكية ، ثم بعد ذلك في مراكز عسكرية في كاليفورنيا ، واوريجون ، وبعد أن تعب من حياة الجيش ، استقال في عام 1854 ، ليعمل في الزراعة بدون نجاح ، ثم في شراء العقارات وبيعها ، ثم كاتبا في محل والده . ومع بداية الحرب الأهلية ، تطوع في قوات ولاية ألينوي ورقي بعد ذلك إلى رتبه كولونيل . كانت انتصاراته الملحوظة في معارك فورت هنري ودونلسون ، شيلوه ، فكسبرج ، وشاتانوفا ، قد شجعت على ترقيته السريعة حتى أصبح قائدا للقوات الإتحادية في الحرب . وكانت نظرته المتسامحة إلى القوات الكونفدرالية وتواضعه ، مع حبه في التعاون مع المتطرفين الجمهوريين ، قد جعله محط أنظار مختلف الفئات السياسية . لقد كان هادئا في شخصيته وغير متظاهر ، ولكنه كان حازما .

Early military career and personal life

West Point and first assignment

At Jesse Grant's request, Representative Thomas L. Hamer nominated Ulysses to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, in spring 1839. Grant was accepted on July 1.[5] Unfamiliar with Grant, Hamer altered his name, so Grant was enlisted under the name "U. S. Grant".[أ][9] Since the initials "U.S." also stood for "Uncle Sam", he became known among army colleagues as "Sam."[10]

Initially, Grant was indifferent to military life, but within a year he reexamined his desire to leave the academy and later wrote that "on the whole I like this place very much".[11] He earned a reputation as the "most proficient" horseman.[12] Seeking relief from military routine, he studied under Romantic artist Robert Walter Weir, producing nine surviving artworks.[13] He spent more time reading books from the library than his academic texts.[14] On Sundays, cadets were required to march to services at the academy's church, which Grant disliked.[15] Quiet by nature, he established a few intimate friends among fellow cadets, including Frederick Tracy Dent and James Longstreet. He was inspired both by the Commandant, Captain Charles Ferguson Smith, and by General Winfield Scott, who visited the academy to review the cadets. Grant later wrote of the military life, "there is much to dislike, but more to like."[16]

Grant graduated on June 30, 1843, ranked 21st out of 39 in his class and was promoted the next day to brevet second lieutenant.[17] He planned to resign his commission after his four-year term. He would later write that among the happiest days of his life were the day he left the presidency and the day he left the academy.[18] Despite his excellent horsemanship, he was not assigned to the cavalry, but to the 4th Infantry Regiment.[ب] Grant's first assignment was the Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri.[20] Commanded by Colonel Stephen W. Kearny, this was the nation's largest military base in the West.[21] Grant was happy with his commander but looked forward to the end of his military service and a possible teaching career.[22]

الزواج والعائلة

In 1844, Grant accompanied Frederick Dent to Missouri and met his family, including Dent's sister Julia. The two soon became engaged.[22] On August 22, 1848, they were married at Julia's home in St. Louis. Grant's abolitionist father disapproved of the Dents' owning slaves, and neither of Grant's parents attended the wedding.[23] Grant was flanked by three fellow West Point graduates in their blue uniforms, including Longstreet, Julia's cousin.[ت][26]

The couple had four children: Frederick, Ulysses Jr. ("Buck"), Ellen ("Nellie"), and Jesse II.[27] After the wedding, Grant obtained a two-month extension to his leave and returned to St. Louis, where he decided that, with a wife to support, he would remain in the army.[28]

الحرب المكسيكية الأمريكية

Grant's unit was stationed in Louisiana as part of the Army of Occupation under Major General Zachary Taylor.[29] In September 1846, President James K. Polk ordered Taylor to march 150 ميل (240 km) south to the Rio Grande. Marching to Fort Texas, to prevent a Mexican siege, Grant experienced combat for the first time on May 8, 1846, at the Battle of Palo Alto.[30] Grant served as regimental quartermaster, but yearned for a combat role; when finally allowed, he led a charge at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma.[31] He demonstrated his equestrian ability at the Battle of Monterrey by volunteering to carry a dispatch past snipers; he hung off the side of his horse, keeping the animal between him and the enemy.[32] Polk, wary of Taylor's growing popularity, divided his forces, sending some troops (including Grant's unit) to form a new army under Major General Winfield Scott.[33]

Traveling by sea, Scott's army landed at Veracruz and advanced toward Mexico City.[34] They met the Mexican forces at the battles of Molino del Rey and Chapultepec.[35] For his bravery at Molino del Rey, Grant was brevetted first lieutenant on September 30.[36] At San Cosmé, Grant directed his men to drag a disassembled howitzer into a church steeple, then reassembled it and bombarded nearby Mexican troops.[35] His bravery and initiative earned him his brevet promotion to captain.[37] On September 14, 1847, Scott's army marched into the city; Mexico ceded the vast territory, including California, to the U.S. on February 2, 1848.[38] During the war, Grant established a commendable record as a daring and competent soldier and began to consider a career in the army.[39][40] He studied the tactics and strategies of Scott and Taylor and emerged as a seasoned officer, writing in his memoirs that this is how he learned much about military leadership.[41] In retrospect, although he respected Scott, he identified his own leadership style with Taylor's. Grant later believed the Mexican war was morally unjust and that the territorial gains were designed to expand slavery. He opined that the Civil War was divine punishment for U.S. aggression against Mexico.[42]

Historians have pointed to the importance of Grant's experience as an assistant quartermaster during the war. Although he was initially averse to the position, it prepared Grant in understanding military supply routes, transportation systems, and logistics, particularly with regard to "provisioning a large, mobile army operating in hostile territory", according to biographer Ronald White.[31] Grant came to recognize how wars could be won or lost by factors beyond the battlefield.[43]

Post-war assignments and resignation

Grant's first post-war assignments took him and Julia to Detroit on November 17, 1848, but he was soon transferred to Madison Barracks, a desolate outpost in upstate New York, in bad need of supplies and repair. After four months, Grant was sent back to his quartermaster job in Detroit.[44] When the discovery of gold in California brought prospectors and settlers to the territory, Grant and the 4th infantry were ordered to reinforce the small garrison there. Grant was charged with bringing the soldiers and a few hundred civilians from New York City to Panama, overland to the Pacific and then north to California. Julia, eight months pregnant with Ulysses Jr., did not accompany him.[45]

While Grant was in Panama, a cholera epidemic killed many soldiers and civilians. Grant organized a field hospital in Panama City, and moved the worst cases to a hospital barge offshore.[46] When orderlies protested having to attend to the sick, Grant did much of the nursing himself, earning high praise from observers.[45] In August, Grant arrived in San Francisco. His next assignment sent him north to Vancouver Barracks in the Oregon Territory.[47]

Grant tried several business ventures but failed, and in one instance his business partner absconded with $800 of Grant's investment, equivalent to $22٬000 in 2022.[48] After he witnessed white agents cheating local Indians of their supplies, and their devastation by smallpox and measles transferred to them by white settlers, he developed empathy for their plight.[49]

Promoted to captain on August 5, 1853, Grant was assigned to command Company F, 4th Infantry, at the newly constructed Fort Humboldt in California.[50] Grant arrived at Fort Humboldt on January 5, 1854, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Robert C. Buchanan.[51] Separated from his family, Grant began to drink.[52] Colonel Buchanan reprimanded Grant for one drinking episode and told Grant to "resign or reform." Grant told Buchanan he would "resign if I don't reform."[53] On Sunday, Grant was found influenced by alcohol, but not incapacitated, at his company's paytable.[54] Keeping his pledge to Buchanan, Grant resigned, effective July 31, 1854.[55] Buchanan endorsed Grant's resignation but did not submit any report that verified the incident.[ث][61] Grant did not face court-martial, and the War Department said: "Nothing stands against his good name."[62] Grant said years later, "the vice of intemperance (drunkenness) had not a little to do with my decision to resign."[63] With no means of support, Grant returned to St. Louis and reunited with his family.[64]

Civilian struggles, slavery, and politics

In 1854, at age 32, Grant entered civilian life, without any money-making vocation to support his growing family. It was the beginning of seven years of financial struggles and instability.[65] Grant's father offered him a place in the Galena, Illinois, branch of the family's leather business, but demanded Julia and the children stay in Missouri, with the Dents, or with the Grants in Kentucky. Grant and Julia declined. For the next four years, Grant farmed with the help of Julia's slave, Dan, on his brother-in-law's property, Wish-ton-wish, near St. Louis.[66] The farm was not successful and to earn a living he sold firewood on St. Louis street corners.[67]

In 1856, the Grants moved to land on Julia's father's farm, and built a home called "Hardscrabble" on Grant's Farm; Julia described it as an "unattractive cabin".[68] Grant's family had little money, clothes, and furniture, but always had enough food.[69] During the Panic of 1857, which devastated Grant as it did many farmers, Grant pawned his gold watch to buy Christmas gifts.[70] In 1858, Grant rented out Hardscrabble and moved his family to Julia's father's 850-acre plantation.[71] That fall, after having malaria, Grant gave up farming.[72] Fearing that electing a Republican president would lead to a civil war, he voted for Democrat James Buchanan in 1856. He had the same fear in 1860 and preferred Douglas, the Democrat. However he did not vote in 1860 because he lacked the resident requirement in Galena.[73]

In 1858, Grant acquired a slave from his father-in-law, a thirty-five-year-old man named William Jones.[74] Although Grant was not an abolitionist at the time, he disliked slavery and could not bring himself to force an enslaved man to work.[75] In March 1859, Grant freed Jones by a manumission deed, potentially worth at least $1,000 (equivalent to $26٬000 in 2022).[76]

Grant moved to St. Louis, taking on a partnership with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs working in the real estate business as a bill collector, again without success and at Julia's prompting ended the partnership.[77] In August, Grant applied for a position as county engineer. He had thirty-five notable recommendations, but Grant was passed over by the Free Soil and Republican county commissioners because he was believed to share his father-in-law's Democratic sentiments.[78]

In April 1860, Grant and his family moved north to Galena, accepting a position in his father's leather goods business, "Grant & Perkins", run by his younger brothers Simpson and Orvil. In a few months, Grant paid off his debts.[79] The family attended the local Methodist church and he soon established himself as a reputable citizen.[80]

الحرب الأهلية

On April 12, 1861, the American Civil War began when Confederate troops attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina.[81] The news came as a shock in Galena, and Grant shared his neighbors' concern about the war.[82] On April 15, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers.[83] The next day, Grant attended a mass meeting to assess the crisis and encourage recruitment, and a speech by his father's attorney, John Aaron Rawlins, stirred Grant's patriotism.[84] In an April 21 letter to his father, Grant wrote out his views on the upcoming conflict: "We have a government and laws and a flag, and they must all be sustained. There are but two parties now, Traitors and Patriots."[85]

مناصب قيادية مبكرة

On April 18, Grant chaired a second recruitment meeting, but turned down a captain's position as commander of the newly formed militia company, hoping his experience would aid him to obtain a more senior rank.[86] His early efforts to be recommissioned were rejected by Major General George B. McClellan and Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon. On April 29, supported by Congressman Elihu B. Washburne of Illinois, Grant was appointed military aide to Governor Richard Yates and mustered ten regiments into the Illinois militia. On June 14, again aided by Washburne, Grant was appointed colonel and put in charge of the 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment;[87] he appointed John A. Rawlins as his aide-de-camp and brought order and discipline to the regiment. Soon after, Grant and the 21st Regiment were transferred to Missouri to dislodge Confederate forces.[88]

On August 5, with Washburne's aid, Grant was appointed brigadier general of volunteers.[89] Major General John C. Frémont, Union commander of the West, passed over senior generals and appointed Grant commander of the District of Southeastern Missouri.[90] On September 2, Grant arrived at Cairo, Illinois, assumed command by replacing Colonel Richard J. Oglesby, and set up his headquarters to plan a campaign down the Mississippi, and up the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.[91]

After the Confederates moved into western Kentucky, taking Columbus, with designs on southern Illinois, Grant notified Frémont and, without waiting for his reply, advanced on Paducah, Kentucky, taking it without a fight on September 6.[92] Having understood the importance to Lincoln of Kentucky's neutrality, Grant assured its citizens, "I have come among you not as your enemy, but as your friend."[93] On November 1, Frémont ordered Grant to "make demonstrations" against the Confederates on both sides of the Mississippi, but prohibited him from attacking.[94]

بلمونت (1861) وحصنا هنري ودنلسون (1862)

On November 2, 1861, Lincoln removed Frémont from command, freeing Grant to attack Confederate soldiers encamped in Cape Girardeau, Missouri.[94] On November 5, Grant, along with Brigadier General John A. McClernand, landed 2,500 men at Hunter's Point, and on November 7 engaged the Confederates at the Battle of Belmont.[95] The Union army took the camp, but the reinforced Confederates under Brigadier Generals Frank Cheatham and Gideon J. Pillow forced a chaotic Union retreat.[96] Grant had wanted to destroy Confederate strongholds at Belmont, Missouri, and Columbus, Kentucky, but was not given enough troops and was only able to disrupt their positions. Grant's troops escaped back to Cairo under fire from the fortified stronghold at Columbus.[97] Although Grant and his army retreated, the battle gave his volunteers much-needed confidence and experience.[98]

Columbus blocked Union access to the lower Mississippi. Grant and lieutenant colonel James B. McPherson planned to bypass Columbus and move against Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. They would then march east to Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River, with the aid of gunboats, opening both rivers and allowing the Union access further south. Grant presented his plan to Henry Halleck, his new commander in the newly created Department of Missouri.[99] Halleck rebuffed Grant, believing he needed twice the number of troops. However, after consulting McClellan, he finally agreed on the condition that the attack would be in close cooperation with the navy Flag Officer, Andrew H. Foote.[100] Foote's gunboats bombarded Fort Henry, leading to its surrender on February 6, 1862, before Grant's infantry even arrived.[101]

Grant ordered an immediate assault on Fort Donelson, which dominated the Cumberland River. Unaware of the garrison's strength, Grant, McClernand, and Smith positioned their divisions around the fort. The next day McClernand and Smith independently launched probing attacks on apparent weak spots but were forced to retreat. On February 14, Foote's gunboats began bombarding the fort, only to be repulsed by its heavy guns. The next day, Pillow attacked and routed McClernand's division. Union reinforcements arrived, giving Grant a total force of over 40,000 men. Grant was with Foote four miles away when the Confederates attacked. Hearing the battle, Grant rode back and rallied his troop commanders, riding over seven miles of freezing roads and trenches, exchanging reports. When Grant blocked the Nashville Road, the Confederates retreated back into Fort Donelson.[102] On February 16, Foote resumed his bombardment, signaling a general attack. Confederate generals John B. Floyd and Pillow fled, leaving the fort in command of Simon Bolivar Buckner, who submitted to Grant's demand for "unconditional and immediate surrender".[103]

Grant had won the first major victory for the Union, capturing Floyd's entire army of more than 12,000. Halleck was angry that Grant had acted without his authorization and complained to McClellan, accusing Grant of "neglect and inefficiency". On March 3, Halleck sent a telegram to Washington complaining that he had no communication with Grant for a week. Three days later, Halleck claimed "word has just reached me that ... Grant has resumed his bad habits (of drinking)."[104] Lincoln, regardless, promoted Grant to major general of volunteers and the Northern press treated Grant as a hero. Playing off his initials, they took to calling him "Unconditional Surrender Grant".[105]

شايلو (1862) وأعقابها

Reinstated by Halleck at the urging of Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Grant rejoined his army with orders to advance with the Army of the Tennessee into Tennessee. His main army was located at Pittsburg Landing, while 40,000 Confederate troops converged at Corinth, Mississippi.[106] Grant wanted to attack the Confederates at Corinth, but Halleck ordered him not to attack until Major General Don Carlos Buell arrived with his division of 25,000.[107] Grant prepared for an attack on the Confederate army of roughly equal strength. Instead of preparing defensive fortifications, they spent most of their time drilling the largely inexperienced troops while Sherman dismissed reports of nearby Confederates.[108]

On the morning of April 6, 1862, Grant's troops were taken by surprise when the Confederates, led by Generals Albert Sidney Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard, struck first "like an Alpine avalanche" near Shiloh church, attacking five divisions of Grant's army and forcing a confused retreat toward the Tennessee River.[109] Johnston was killed and command fell upon Beauregard.[110] One Union line held the Confederate attack off for several hours, giving Grant time to assemble artillery and 20,000 troops near Pittsburg Landing.[111] The Confederates finally broke and captured a Union division, but Grant's newly assembled line held the landing, while the exhausted Confederates, lacking reinforcements, halted their advance.[112][ج]

Bolstered by 18,000 troops from the divisions of Major Generals Buell and Lew Wallace, Grant counterattacked at dawn the next day and regained the field, forcing the disorganized and demoralized rebels to retreat to Corinth.[114] Halleck ordered Grant not to advance more than one day's march from Pittsburg Landing, stopping the pursuit.[115] Although Grant had won the battle, the situation was little changed.[116] Grant, now realizing that the South was determined to fight, would later write, "Then, indeed, I gave up all idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest."[117]

Shiloh was the costliest battle in American history to that point and the staggering 23,746 casualties stunned the nation.[118] Briefly hailed a hero for routing the Confederates, Grant was soon mired in controversy.[119] The Northern press castigated Grant for shockingly high casualties, and accused him of drunkenness during the battle, contrary to the accounts of those with him at the time.[120] Discouraged, Grant considered resigning but Sherman convinced him to stay.[121] Lincoln dismissed Grant's critics, saying "I can't spare this man; he fights."[122] Grant's costly victory at Shiloh ended any chance for the Confederates to prevail in the Mississippi valley or regain its strategic advantage in the West.[123]

Halleck arrived from St. Louis on April 11, took command, and assembled a combined army of about 120,000 men. On April 29, he relieved Grant of field command and replaced him with Major General George Henry Thomas. Halleck slowly marched his army to take Corinth, entrenching each night.[124] Meanwhile, Beauregard pretended to be reinforcing, sent "deserters" to the Union Army with that story, and moved his army out during the night, to Halleck's surprise when he finally arrived at Corinth on May 30.[125]

Halleck divided his combined army and reinstated Grant as field commander on July 11.[126] Later that year, on September 19, Grant's army defeated Confederates at the Battle of Iuka, then successfully defended Corinth, inflicting heavy casualties.[127] On October 25, Grant assumed command of the District of the Tennessee.[128] In November, after Lincoln's preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, Grant ordered units under his command to incorporate former slaves into the Union Army, giving them clothes, shelter, and wages for their services.[129]

حملة ڤيكسبرگ

The Union capture of Vicksburg, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River, was considered vital as it would split the Confederacy in two.[130] Lincoln appointed McClernand for the job, rather than Grant or Sherman.[131] Halleck, who retained power over troop displacement, ordered McClernand to Memphis, and placed him and his troops under Grant's authority.[132]

On November 13, 1862, Grant captured Holly Springs and advanced to Corinth.[133] His plan was to attack Vicksburg overland, while Sherman would attack Vicksburg from Chickasaw Bayou.[134] However, Confederate cavalry raids on December 11 and 20 broke Union communications and recaptured Holly Springs, preventing Grant and Sherman from converging on Vicksburg.[135] McClernand reached Sherman's army, assumed command, and independently of Grant led a campaign that captured Confederate Fort Hindman.[136] After the sack of Holly Springs, Grant considered and sometimes adopted the strategy of foraging the land,[137] rather than exposing long Union supply lines to enemy attack.[138]

Fugitive African-American slaves poured into Grant's district, whom he sent north to Cairo to be domestic servants in Chicago. However, Lincoln ended this when Illinois political leaders complained.[139] On his own initiative, Grant set up a pragmatic program and hired Presbyterian chaplain John Eaton to administer contraband camps.[140] Freed slaves picked cotton that was shipped north to aid the Union war effort. Lincoln approved and Grant's program was successful.[141] Grant also worked freed black labor on a canal to bypass Vicksburg, incorporating the laborers into the Union Army and Navy.[142]

Grant's war responsibilities included combating illegal Northern cotton trade and civilian obstruction.[143][ح] He had received numerous complaints about Jewish speculators in his district.[146] The majority, however, of those involved in illegal trading were not Jewish.[147] To help combat this, Grant required two permits, one from the Treasury and one from the Union Army, to purchase cotton.[144] On December 17, 1862, Grant issued a controversial General Order No. 11, expelling "Jews, as a class", from his military district.[148] After complaints, Lincoln rescinded the order on January 3, 1863. Grant finally ended the order on January 17. He later described issuing the order as one of his biggest regrets.[خ][152]

On January 29, 1863, Grant assumed overall command. To bypass Vicksburg's guns, Grant slowly advanced his Union army south through water-logged terrain.[153] The plan of attacking Vicksburg from downriver was risky because, east of the river, his army would be distanced from most of its supply lines,[154] and would have to rely on foraging. On April 16, Grant ordered Admiral David Dixon Porter's gunboats south under fire from the Vicksburg batteries to meet up with troops who had marched south down the west side of the river.[155] Grant ordered diversionary battles, confusing Pemberton and allowing Grant's army to move east across the Mississippi.[156] Grant's army captured Jackson. Advancing west, he defeated Pemberton's army at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16, forcing their retreat into Vicksburg.[157]

After Grant's men assaulted the entrenchments twice, suffering severe losses, they settled in for a siege which lasted seven weeks. During quiet periods of the campaign, Grant would drink on occasion.[158] The personal rivalry between McClernand and Grant continued until Grant removed him from command when he contravened Grant by publishing an order without permission.[159] Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to Grant on July 4, 1863.[160]

Vicksburg's fall gave Union forces control of the Mississippi River and split the Confederacy. By that time, Grant's political sympathies fully coincided with the Radical Republicans' aggressive prosecution of the war and emancipation of the slaves.[161] The success at Vicksburg was a morale boost for the Union war effort.[159] When Stanton suggested Grant be brought east to run the Army of the Potomac, Grant demurred, writing that he knew the geography and resources of the West better and he did not want to upset the chain of command in the East.[162]

Chattanooga (1863) and promotion

On October 16, 1863, Lincoln promoted Grant to major general in the regular army and assigned him command of the newly formed Division of the Mississippi, which comprised the Armies of the Ohio, the Tennessee, and the Cumberland.[163] After the Battle of Chickamauga, the Army of the Cumberland retreated into Chattanooga, where they were partially besieged.[164] Grant arrived in Chattanooga, where plans to resupply and break the partial siege had already been set. Forces commanded by Major General Joseph Hooker, which had been sent from the Army of the Potomac, approached from the west and linked up with other units moving east from inside the city, capturing Brown's Ferry and opening a supply line to the railroad at Bridgeport.[165]

Grant planned to have Sherman's Army of the Tennessee, assisted by the Army of the Cumberland, assault the northern end of Missionary Ridge and roll down it on the enemy's right flank. On November 23, Major General George Henry Thomas surprised the enemy in open daylight, advancing the Union lines and taking Orchard Knob, between Chattanooga and the ridge. The next day, Sherman failed to get atop Missionary Ridge, which was key to Grant's plan of battle. Hooker's forces took Lookout Mountain in unexpected success.[166] On the 25th, Grant ordered Thomas to advance to the rifle-pits at the base of Missionary Ridge after Sherman's army failed to take Missionary Ridge from the northeast.[167] Four divisions of the Army of the Cumberland, with the center two led by Major General Philip Sheridan and Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood, chased the Confederates out of the rifle-pits at the base and, against orders, continued the charge up the 45-degree slope and captured the Confederate entrenchments along the crest, forcing a hurried retreat.[168] The decisive battle gave the Union control of Tennessee and opened Georgia, the Confederate heartland, to Union invasion.[169]

On March 2, 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general, giving him command of all Union Armies.[170] Grant's new rank had previously been held only by George Washington.[171] Grant arrived in Washington on March 8 and was formally commissioned by Lincoln the next day at a Cabinet meeting.[172] Grant developed a good working relationship with Lincoln, who allowed Grant to devise his own strategy.[173]

Grant established his headquarters with General George Meade's Army of the Potomac in Culpeper, Virginia, and met weekly with Lincoln and Stanton in Washington.[174] After protest from Halleck, Grant scrapped a risky invasion of North Carolina and planned five coordinated Union offensives to prevent Confederate armies from shifting troops along interior lines.[175] Grant and Meade would make a direct frontal attack on Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, while Sherman—now in command of all western armies—would destroy Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee and take Atlanta.[176] Major General Benjamin Butler would advance on Lee from the southeast, up the James River, while Major General Nathaniel Banks would capture Mobile.[177] Major General Franz Sigel was to capture granaries and rail lines in the fertile Shenandoah Valley.[178] Grant now commanded 533,000 battle-ready troops spread out over an eighteen-mile front.[179]

Overland Campaign (1864)

The Overland Campaign was a series of brutal battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864.[180] Sigel's and Butler's efforts failed, and Grant was left alone to fight Lee.[181] On May 4, Grant led the army from his headquarters towards Germanna Ford.[182] They crossed the Rapidan unopposed.[183] On May 5, the Union army attacked Lee in the battle of the Wilderness, a three-day battle with estimated casualties of 17,666 Union and 11,125 Confederate.[184]

Rather than retreat, Grant flanked Lee's army to the southeast and attempted to wedge his forces between Lee and Richmond at Spotsylvania Court House.[185] Lee's army got to Spotsylvania first and a costly battle ensued, lasting thirteen days, with heavy casualties.[186] On May 12, Grant attempted to break through Lee's Muleshoe salient guarded by Confederate artillery, resulting in one of the bloodiest assaults of the Civil War, known as the Bloody Angle.[187] Unable to break Lee's lines, Grant again flanked the rebels to the southeast, meeting at North Anna, where a battle lasted three days.[188]

Cold Harbor

The recent bloody Wilderness campaign had severely diminished Confederate morale;[189] Grant believed breaking through Lee's lines at its weakest point, Cold Harbor, a vital road hub that linked to Richmond, would mean a quick end to the war.[190] Grant already had two corps in position at Cold Harbor with Hancock's corps on the way.[191]

Lee's lines were extended north and east of Richmond and Petersburg for approximately ten miles, but at several points there were no fortifications built yet, including Cold Harbor. On June 1 and 2 both Grant and Lee were waiting for reinforcements to arrive. Hancock's men had marched all night and arrived too exhausted for an immediate attack that morning. Grant postponed the attack until 5 p.m., and then again until 4:30 a.m. on June 3. However, Grant and Meade did not give specific orders for the attack, leaving it up to the corps commanders to coordinate. Grant had not yet learned that overnight Lee had hastily constructed entrenchments to thwart any breach attempt at Cold Harbor.[192] Grant was anxious to make his move before the rest of Lee's army arrived. On the morning of June 3, with a force of more than 100,000 men, against Lee's 59,000, Grant attacked, not realizing that Lee's army was now well entrenched, much of it obscured by trees and bushes.[193] Grant's army suffered 12,000–14,000 casualties, while Lee's army suffered 3,000–5,000 casualties, but Lee was less able to replace them.[194]

The unprecedented number of casualties heightened anti-war sentiment in the North. After the battle, Grant wanted to appeal to Lee under the white flag for each side to gather up their wounded, most of them Union soldiers, but Lee insisted that a total truce be enacted and while they were deliberating all but a few of the wounded died in the field.[195] Without giving an apology for the disastrous defeat in his official military report, Grant confided in his staff after the battle and years later wrote in his memoirs that he "regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made."[196]

Siege of Petersburg (1864–1865)

Undetected by Lee, Grant moved his army south of the James River, freed Butler from the Bermuda Hundred, and advanced toward Petersburg, Virginia's central railroad hub,[197] resulting in a nine-month siege. Northern resentment grew. Sheridan was assigned command of the Union Army of the Shenandoah and Grant directed him to "follow the enemy to their death" in the Shenandoah Valley.[198] After Grant's abortive attempt to capture Petersburg, Lincoln supported Grant in his decision to continue.[199]

Grant had to commit troops to check Confederate General Jubal Early's raids in the Shenandoah Valley, which were getting dangerously close to Washington.[200] By late July, at Petersburg, Grant reluctantly approved a plan to blow up part of the enemy trenches from a tunnel filled with gunpowder. The massive explosion instantly killed an entire Confederate regiment.[201] The poorly led Union troops under Major General Ambrose Burnside and Brigadier General James H. Ledlie, rather than encircling the crater, rushed into it. Recovering from the surprise, Confederates, led by Major General William Mahone,[202] surrounded the crater and easily picked off Union troops. The Union's 3,500 casualties outnumbered the Confederates' three-to-one. The battle marked the first time that Union black troops, who endured a large proportion of the casualties, engaged in any major battle in the east.[203] Grant admitted that the tactic had been a "stupendous failure".[204]

Grant would later meet with Lincoln and testify at a court of inquiry against Generals Burnside and Ledlie for their incompetence.[205] In his memoirs, he blamed them for that disastrous Union defeat.[206] Rather than fight Lee in a full-frontal attack as he had done at Cold Harbor, Grant continued to force Lee to extend his defenses south and west of Petersburg, better allowing him to capture essential railroad links.[200]

Union forces soon captured Mobile Bay and Atlanta and now controlled the Shenandoah Valley, ensuring Lincoln's reelection in November.[207] Sherman convinced Grant and Lincoln to allow his army to march on Savannah.[208] Sherman cut a 60-ميل (97 km) path of destruction unopposed, reached the Atlantic Ocean, and captured Savannah on December 22.[209] On December 16, after much prodding by Grant, the Union Army under Thomas smashed John Bell Hood's Confederates at Nashville.[210] These campaigns left Lee's forces at Petersburg as the only significant obstacle remaining to Union victory.[211]

By March 1865, Lee was trapped and his strength severely weakened.[212] He was running out of reserves to replace the high battlefield casualties and remaining Confederate troops, no longer having confidence in their commander and under the duress of trench warfare, deserted by the thousands.[213] On March 25, in a desperate effort, Lee sacrificed his remaining troops (4,000 Confederate casualties) at Fort Stedman, a Union victory and the last Petersburg line battle.

Surrender of Lee and Union victory (1865)

On April 2, Grant ordered a general assault on Lee's forces; Lee abandoned Petersburg and Richmond, which Grant captured.[214] A desperate Lee and part of his army attempted to link up with the remnants of Joseph E. Johnston's army. Sheridan's cavalry stopped the two armies from converging, cutting them off from their supply trains.[215] Grant sent his aide Orville Babcock to carry his last dispatch to Lee demanding his surrender.[216] Grant immediately rode west, bypassing Lee's army, to join Sheridan who had captured Appomattox Station, blocking Lee's escape route. On his way, Grant received a letter from Lee stating Lee would surrender his army.[217]

On April 9, Grant and Lee met at Appomattox Court House.[218] Although Grant felt depressed at the fall of "a foe who had fought so long and valiantly," he believed the Southern cause was "one of the worst for which a people ever fought."[219] Grant wrote out the terms of surrender: "each officer and man will be allowed to return to his home, not to be disturbed by U.S. authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside." Lee immediately accepted Grant's terms and signed the surrender document, without any diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy. Lee asked that his former Confederate troops keep their horses, which Grant generously allowed.[220][221] Grant ordered his troops to stop all celebration, saying the "war is over; the rebels are our countrymen again."[222] Johnston's Tennessee army surrendered on April 26, 1865, Richard Taylor's Alabama army on May 4, and Kirby Smith's Texas army on May 26, ending the war.[223]

اغتيال لنكون

في 14 أبريل 1865 فـُجعت الأمة الأمريكية عندما اغتيل لنكولن في مسرح فورد. وقد كان لنكولن أكبر مدافع عن جرانت وأكبر صديق ومستشار عسكري. وقد قال لنكولن بعد الخسائر الفادحة في شايلوه: "لا أستطيع الاستغناء عن هذا الرجل. إنه يقاتل." تلك الجملتان لخصتا جوهر يوليسيس جرانت.[224]

الترقية النهائية

بعد الحرب، في 25 يوليو 1866، صرح الكونجرس بإنشاء رتبة عسكرية جديدة جنرال جيش الولايات المتحدة، وهي المناظرة لجنرال (أربعة نجوم) في العصر الحالي.[225] ومنحها الرئيس أندرو جونسون لجرانت في نفس اليوم.

انتقادات عسكرية وجدل

الحرب بالاستنزاف

الأمر العام رقم 11 ومعاداة السامية

مقالة مفصلة: الأمر العام رقم 11 (1862)

مقالة مفصلة: الأمر العام رقم 11 (1862)

الحملة الرئاسية 1868

الرئاسة 1869-1877

مع أن الرئيس جرانت كان محبوبا وناجحا كرجل عسكري ، إلا أن بعض خصائصه – في نظر كثير من المؤرخين – وكذلك عدم خبرته السياسية لم تجعله مؤهلا لمنصب الرئيس في الولايات المتحدة.

السياسات الداخلية

اعادة البناء

الحقوق المدنية وحقوق الإنسان

هلع 1873

عيوب جرانت

واتضح بأن خبرة جرانت العسكرية ، كانت في بعض الأحيان عاملا معيقا لنجاحه في الخدمة العامة . فلقد تعود جرانت كرجل عسكري أن يطبعه أعوانه العسكريين إطاعة عمياء ، ولذلك فإنه توقع من السياسيين المعينيين أن يكونوا بالمثل ، ولكن اتضح له بأن هذه الثقة في غير محلها ، كما أن نقص خبرته في الخدمة المدنية ، جعله يقوم بتعيين أناس ضعيفو الكفاءة : فمن بين الكثيرين الذين عينهم ، كانوا من أصدقائه وأقاربه والعديد من أقارب زوجته ، وفي كثير من الأحيان كان متسرعا في قراراته حيث حابى جماعة كانت قد تسرعت ببناء ثلاث بيوت له ، وجماعات أخرى قدمت له الهدايا الكثيرة ، وبما أنه لم ينجح في حياته كرجل أعمال ، فإنه كان معجبا بأولئك الذين نجحوا في عملهم ، وأصبحوا من كبار الأثرياء . ولقد أعجب ، واستمع لكثير من رجال الأعمال الطامعين ، أصحاب المصالح الذاتية ، والمخاذلين وجعل منهم أصدقاء ملازمين له ، لم تنتخب أمريكا رجلا عسكريا للرئاسة إلا في عام 1952 هو دوايت أيزنهاور.

الجو الأخلاقي بعد الحرب

إن الفضائح التي ظهرت في عهد جرانت إنما هي انعكاس لانحطاط الجو الأخلاقي الذي تردت فيه البلاد ، في تلك الفترة . تعود المسئولون الحكوميون على صرف أموال طائلة أثناء الحرب مما ثبت فيهم هذه العادة ، بحيث أصبحوا قليلي الاهتمام بأموال الدولة عندما انتقلوا إلى الخدمة العامة . انتشارا لفساد في هذه الفترة إنما يمكن تفسيره برغبة السياسيين في السلطة ، وطمع أغنياء الحرب في الزيادة من جمع الأموال ، وانخفاض الروح المعنوية بسبب الحرب . إن كلا من الشمال والجنوب عانى من هذا الفساد ، فقد شاعت فكرة ، (كلب يأكل كلب) في مجال العمل ، وكأن هؤلاء تقودهم فكرة النظرية الداروينية ؛ حيث أن البقاء يكون للأقوى ، ونما أصحاب العمل وأصبحوا أكثر غنى لأنهم كانوا مخاذلين ، قاسين ، وفاسدين ، وبذلك حصلوا على ميزات خاصة من الدولة . وفي هذه البيئة ، فقد بدا جرانت وكأنه قاس عديم التأثر ، بخلاف كثير من المصلحين في عهده . لقد بدا وكأنه لايشعر ولا يهتم بما يدور حوله . ومع أنه قد حصل على ثروة كبيرة في شكل تبرعات إما نقدا أو في شكل ممتلكات ، إلا أنه لم يقبل هدايا كبديل لخدمات خاصة .

محاباة جرانت لأصحاب العمل

يمكن القول بأن مصالح أصحابا لعمل بأنواعهم المختلفة قد تمتعت بحرية العمل ، وبعدم أي تدخل من الحكومة في شئونها ، وبجو سياسي يرعى مصالحها أكثر من أي عه9د مضى في تاريخ الجمهورية .

إن الحرب الأهلية إنما مثلت انتصار مصالح أصحاب العمل المتركزة في الشمال الشرقي ، وقد رأى الجمهوريون المتطرفون بأن ما كسبوه وقت الحرب لن يسمحوا بخسارته على مسرح السياسة . لقد حابت إدارة جرانت أصحاب العمل بإبقائها على التعريفة الجمركية العالية ، وتسلمت السكك الحديدية مساعدات من الحكومة الفدرالية في شكل منح من الأراضي ، والقروض ،والإعقاء من الجمارك على الجماعات المستوردة لها ، واستفادت الطبقة الدائنة من الرجوع إلى احتياطي الذهب ، وتحديد العرض من العملة ، كما أن أصحاب رؤوس الأموال والمضاربين استفادوا عن طريق الحصول على معلومات خاصة داخلية – تتعلق بسياسة الحكومة المالية .

فضائح إدارة جرانت

إن ظهور بعض الفضائح المشهورة في عهد رئاسة جرانت إنما يمثل مدى التردي الأخلاقي لعصره .

المؤامرة على الذهب (الجمعة السوداء)

حاول إثنان من المضاربين في الأسواق المالية : جيم فسك ، وجي جورلد ، في سبتمبر عام 1869 ، أن يقوموا بعمل الملايين في وقت قصير عن طريق احتكارهم للمعروض من الذهب في البلاد . كان الرئيس جرانت اقتنع بمناقشة بسيطة مبدئية من قبل زوج أخته ؛ وهي أن المزارعين الأمريكيين – وخصوصا في الغرب – سيستفيدون كثيرا من ارتفاع أسعار القمح إذا ما أوقفت خزانة الولايات المتحدة بين الذهب في البلاد . وببراءة أوقف الرئيس الخزانة الأمريكية من بيع الذهب ، وهنا قام هؤلاء بشراء كثير من المعروض من الذهب في السوق لم تحكموا في أسعاره – فيما بعد – ورفعوها أضعافا . وهكذا فإن أصحاب العمل الذين كانوا يحتاجون إلى الذهب في مشاريعهم لم يستطيعوا الحصول عليه بالأسعار المعقولة ، مما أدى إلى إفلاس الكثير . وعندما شعر الرئيس بخطته ؛ أمر الخزانة مرة أخرى ببيع الذهب ، وهكذا قضى على حمى المضاربة ، ولكن بعد أن ذهب ضحيتها آلاف من الناس .

عصابة تويد (Tweed Ring)

لبضع سنوات قبيل عام 1871 – كان الزعيم تويد قد ترأس جمعية من النصابين السياسيين في مدينة نيويورك التي نهت خزانة المدينة بما يقارب مائتي مليون من الدولارات عن طريق التزييف والدفعات المزورة . وقامت جريدة نيويورك تايمز بنشر البيانات التي فضحت هذه العصابة في عام 1871 ، بحيث استطاع النائب العام صامويل جي تلدين أن يحصل بالحكم على تويد . وكان لجهود الرسام الكاريكاتيري توماس ناست أثره في فضح رسائل المزيفين بالدعاية ضدهم عن طريق رسوماته .

فضيحة الكريديه – موبلييه (Credit Mobilier

هذه الفضيحة كان لها تأثير كبير على سمعة الجمهوريين الذين سيطروا على الكونجرس في فترة حكم جرانت الأولى . لقد كانت هذه عبارة عن شركة لبناء السكك الحديدية نظمتها فئة المسيطرين على سكة حديد الباسفيكي الإتحادية ؛ لكي تحصل على ملايين الدولارات كربح عائد عليهم . وكان أوكس إيمز ممثل هذه الشركة ، قد رشى كثيرا من رجال الكونجرس بإغرائهم بتأييد عدم وقف المعونات التي كانت تقدمها الحكومة الإتحادية إلى السكة الحديد في شكل منح من الأراضي والقروض . معظهم هذه الأعمال كانت قبل أن يصبح جرانت رئيسا . وقد كانت هذه الفضيحة التي ظهرت أبعادها من خلال تحقيقات قام بها الكونجرس في عام 1872 ، قد حطمت سمعة الكثير من رجال الكونجرس المعروفين .

قانون زيادة المرتبات

في عام 1873 ، قام الكونجرس بمضاعفة مرتب رئيس الجمهورية . وزاد مرتب أعضائه بمقدار 50% ولكن سيئة القانون أن جعل الزيادة سنتين بأثر رجعي . رد الفعل السيء من الرأي العام على هذا القانون ، كان قد أدى إلى سيطرة الحزب الديمقراطي على الكونجرس القادم ، وعندها ألغى هذا القانون .

عقد سان بورن وفضائح أخرى

اتضح في عام 1874 أن وزارة الخزانة الأمريكية تعاقدت مع شخص اسمه سان بورن ، للقيام بجمع ضرائب غير مدفوعة تبلغ قيمتها 427.000 دولار ، وأنه أعطى عمولة مقدارها 50% ، وأن هذه العمولة استعملت لتمويل نشاطات سياسية للحزب الجمهوري .

ثم هناك ما سمي بفضيحة (جماعة الويسكي) ، وهي عبارة عن مؤامرة بين صانعي الويسكي وبعض موظفي الخزانة الأمريكية الذين يجمعون الضريبة على المشروب لهيئة الخزانة الأمريكية بأموال طائلة عن طريق تخفيف الضريبة المطلوبة واقتسام الفرق ، وكان سكرتير الرئيس جرانت قبل الرئوة من هذه الجماعة عند علمه بهذا العمل ، وأن الرئيس نفسه قبل بعض الهدايا التي كان عليه أن يشك في سبب إعطائها له .

وفي فضيحة أخرى ، فإن وزير الحربية : و.و. بلكناب ، قبل رشوة من تاجر في منطقة الهنود ، وكان يمكن لهذا أن يقدم للمحاكم ؛ لولا أنه استقال .

العلاقات الدولية في عهد جرانت

كان جرانت محظوظا في اختياره لهاملتون فش كوزير للخارجية الأمريكية . ولقد أثبت فش قدرته الدبلوماسية ، بحيث استطاع أن يحل كثيرا من المشاكل المعلقة مع بريطانيا حلا سلميا . وهكذا فإن حصيلة إدارة جرانت في السياسة الخارجية تعتبره بناءة إلى حد كبير .

محاولة ضم سانتو دومنجو

استمع جرانت عام 1869 إلى نصيحة بعض المضاربين ، من أصحاب الأموال والأراضي ، بضرورة الاستيلاء على سانتو دومنجو ، فقام بتقديم معاهدة إلى مجلس اشيوخ بشأن الموافقة على مثل هذا العمل . ولكن السناتور تشارلس سمنر لاحظ ما في الأمر من تلاعب ، وكان له أثره في منع مجلس الشيوخ من الموافقة على تلك المعاهدة . واستمر الرئيس في محاولته جاهدا – دون جدوى – أن يحصل على موافقة المجلس في هذا الأمر . وانتقاما من سمنر ، فقد استطاع جرانت التأثير على مجلس الشيوخ بإزاحة سمنر عن رئاسة لجنة الشيوخ للعلاقات الخارجية .

الفينيانز (the Finians) كانت هذه عبارة عن جمعية سرية من أيرلنديين أمريكيين تكونت في عام 1850 بغرض معاونة أيرلندا الحصول على استقلالها من بريطانيا . وبعد الحرب الأهلية خططت هذه الجمعية على كسب كثير من المحاربين القدماء للقيام بالاستيلاء على كندا واستبدالها مع بريطانيا مقابل تحريرا أيرلندا وقام هؤلاء بالفعل بغزو كندا عام 1866 من الولايات المتحدة عن طريق نهر نياجرا ، وقد اشتبكوا مع الميليشيا الكندية ، وحاولوا ذلك مرة أخرى في عام 1876 ، ولكن الحكومة الأمريكية قامت باعتقال قادة هذه الحركة ، وأخذت على نفسها تعهدات مع بريطانيا يمنع مثل هذه الحوادث في المستقبل .

معاهدة واشنطن عام (1871)

بالنيابة عن حكومة الولايات المتحدة ، قام تشارلس سمنر ، المتكلم باسم (لجنة الشيوخ للعلاقات الخارجية) ، بادعاءات ضد الحكومة البريطانية ، مطالبا إياها بدفع تعويضات نتيجة الخسائر التي ألحقتها الطرادات البريطانية المعطاة لقوات البحرية الكونفدرالية أثناء الحرب الأهلية ، وخصوصا الطراد (ألباما) وغيره ، مما سبب خسائر كبيرة في التجارة البحرية ، ولم يمكن التوصل إلى حل بين الدولتين بهذا الخصوص لإصرار بريطانيا بأن سمنر كان كثير المبالغة ، وأن التعويضات التي كان يطالب بها إنما كانت في غير المعقول . وعندما جاء فش سكرتيرا للخارجية الأمريكية ؛ بدأ – بهدوء – اتصالاته ومفاوضاته مع الحكومةالبريطانية . وقد استطاع التوصل إلى حسم للخلاف بعمل اتفاقية واشنطن مع بريطانيا عام 1871 م . تضمنت هذه الإتفاقية استعمال طريقة التحكيم (Arbitration) لحل كثير من المشكلات المعلقة ، وبالفعل كانت طريقة التحكيم هذه قد قدمت حلولا للمشاكل الآتية : بخصوص الخسائر الناجمة عن الطراد ألباما ، حيث اجتمعت لجنة تحكيم في جنيف ، وحكمت لأمريكا بتعويضات مقدارها 15.5 مليون دولار ؛ عوضت الولايات المتحدة بريطانيا مقدار 5.5 مليون دولار لخرق الأولى حقوق الصيد البريطانية على ساحل الأطلسي الشمالي الشرقي ؛ كما استطاعت الدولتان عن طريق التحكيم وضع الحدود بين الولايات المتحدة وبين كولومبيا البريطانية (في كندا) في سلسلة الجزر الواقعة على الحدود – بوجيه ساوند . هذه الإتفاقيات كانت حجر الأساس – في البداية – لحل كل المشكلات بين البلدين بطريقة سلمية ، كما انها رسخت مبدأ التحكيم كوسيلة لحل النزاعات الدولية.

انتفاضة كوبا

حادثة Virginius

كانت هناك انتفاضة كوبا ضد حكم إسبانيا ، دامت من 1868-1878 م . ومع أن الولايات المتحدة كانت متعاطفة مع الثوار هناك ؛ إلا أنها حاولت التزام سياسة الحياد . في عام 1873 ، قام الإسبانيون بالسطو على سفينة اسمها فرجينوس ، حيث كانت ترفع بطريقة غير شرعية العلم الأمريكي ، ثم أعدموا ما عليها بما فيهم بعض الأمريكيين . ونتيجة جهود فش ؛ تجنبت أ/ريكا الحرب مع إسبانيا بعد أن تعهدت الأخيرة بدفع تعويضات للعائلات الثكلى .

Liberian-Grebo war

معاهدة بيرلنگيم (Burlingame)

قام الوزير المفوض الأمريكي في الصين ، أنسون بيرلنجيم، بعمل اتفاقية مع الحكومة الصينية عام 1868، والتي سمحت أ/ريكا فيها بهجرة الصينيين غير المقيدة إلى الولايات المتحدة . ونتيجة هذه المعاهدة ، دخلت أعداد كبيرة من الصينيين إلى ولاية كاليفورنيا . وقد عارضت حكومة الولاية هذه المعاهدة ، محاولة عدة مرات منع دخول هؤلاء المهاجرين إلى كاليفورنيا، دون جدوى.

انتخابات عام 1872

أهم مظاهر انتخابات الرئاسة في هذاا لعام ؛ إنما كان ظهور فئة الجمهوريين الأحرار داخل الحزب الجمهوري ؛ وقد ثار هؤلاء على سياسة الثأر التي استخدمها أعوانهم في تطبيقهم لخطة التعمير في الجنوب ، وطالبوا بعدالة وأمانة أكثر في أعمال الحكومة إلى جانب عديد من الإصلاحات . وهكذا انقسم الجمهوريون إلى فئتين : المترطفون وقد رشحوا بطبيعة الحال الرئيس جرانت ، ثم الأحرار الذين انقضوا الآن في حزب مستقل سموه (الحزب الجمهوري الحر) ؛ حيث رشحوا هوارس گريلي. جريلي كان رئيسا لتحرير جريدةنيويورك تبيون ، حيث كان أيضا مرشحا عن الحزب الديمقراطي . في هذه الحملة ؛ لجأ المتطرفون إلى مخاطبة عواطف الناخبين بتذكيرهم ببطل الحرب الأهلية ، ولجأ الطرفان إلى استعمال الدعايات الكاذبة .

واستطاع المتطرفون إنجاح جرانت ، بسبب سيطرتهم على أصوات الناخبين السود في الولايات الجنوبية الثلاثة التي لم تكن قد قبلت بعد في الإتحاد. ولكن ثورة الأحرار الجمهوريين هذه كانت قد أرغمت أعوانهم على اتخاذ خطوات حاسمة لتدعيم الأمانة في شئون الحكومة الإتحادية.

المشاكل الإقتصادية في أعقاب الحرب

رجوع الإقتصاد لحالة السلم سبب أزمة اقتصادية مفاجئة ، كما أن الرجوع بعد الحرب إلى نظم دعم العملة بالذهب قد جلب نقصا في العملة المتداولة أثر على المزارعين والدائنين .

ذعر 1873

بدأت هذه الأزمة نتيجة إفلاس شركة جي كوك . إفلاس هذه الشركة – التي كانت من أكبر المساهمين الماليين في الحرب الأهلية – سبب انتفاضة بين أصحابا لأعمال الأمريكيين . من أسباب هذه الأزمة – أيضا – التوسع الزائد في بناء السكة الحديد وفي الصناعة ، والنمو الإقتصادي الذي خلف الحرب الأهلية .

Vetoes inflationary bill

الخلاف حول سياسة العملة : في خلال الحرب الأهلية، طبعت الخزانة الفدرالية كميات كبيرة من العملة الورقية تعرف بجرينباكس (Greenbax) ، وكان ذلك ضروريا لعدم وجود ذهب يغطي المدينين أن يدفعوا ما عليهم من هذه العملة . بعد الحرب ، أوقفت الخزانة هذا العمل بتقليل العرض من ثمن المحصولات الزراعية انخفض بشكل كبير ، كما أن الفئات الدائنة وجدت صعوبة في سداد التزاماتها لعدم عرض العملة الورقية . في عام 1868 ، اقترح الحزب الديمقراطي في برنامجه السياسي ما سمي بـ(فكرة أوهايو) ، والتي بموجبها ، طالبوا الحكومة بدفع ثمن السندات للمواطنين بواسطة العملة الورقية . وهنا ظهر خلاف حول هذه الاقتراح : لقد وافقت عليه الفئات الدائنة والمزارعين ، ولكن الحزب الجمهوري ، وعلى الأخص أصحاب العمل فيه ، كانوا يريدون الرجوع إلى نظام الذهب ، ولذلك عارضوا فكرة أوهايو ، ومن هنا استطاع أتباع الحزب الجمهوري عرقة العمل بالقرار .

وفي عام 1870 ، قامت المحكمة الإتحادية ، فيما يسمى بـ (قضايا العملة الشرعية) بالحكم بأن الدولار الأخضر لا يعتبر شرعيا في دفع الديون قبل طبعه – أي قبل عام 1862 م ، ولكن جرانت كان قد عين اثنين من قضاة المحكمة الموالين لرأيه ، ولذلك قامت المحكمة في عام 1871 بتغيير رأيها بخصوص قرار عام 1870 بحكمها بأن الدولار الأخضر يعتبر شرعيا (دستوريا) – ولكن هذا يعني الإعتراف بما هو متداول فس السوق من الدولار الأخضر ، وعلى ذلك لم ينته هذا القرار أزمة قلة المعروض من العملة الورقية .

جريمة عام 1873 الإقتصادية : في عام 1873 ، اتخذت خطوة أخرى منعت من زيادة العرض من العملة الورقية ؛ حيث وافق الكونجرس على اقتراح لوزارة الخزانة بمنع شرا وطبع العملة الفضية ، التي أصبحت نادرة في ذلك الوقت . وبمحض الصدفة ، زاد العرض على الفضة ، وبذلك نقص سعرها ، في الوقت الذي منع طبعها ، بالنسبة للفئات المدنية الدائنة .

ظهر هذاا لعمل بأنه متعمد من قبل أصحاب المصالح (الدائنين الأصليين) ليمنعوا عرض الفضة الذي سيؤثر على عرض ثمن العملة الورقية . الدائنون الأصليون قصدوا تقليل العرض لخدمة مصالحهم . وهكذا فقد اعترضت الطبقات المدينة على هذه السياسة ، وأطلقواعلى قانون الكونجرس هذا (جريمة 1873 الإقتصادية) ، ثم بدأوا يطالبون بإعطاء الفضة قيمتها – أي طبعها وبيعها – كوسيلة لزيادة المعروض من العملة في الأسواق .

قانون التكملة عام 1875 : تحت ضغط أصحاب المصالح المالية ، قام الكونجرس بالموافقة على إعادة الرجوع إلى نظام الذهب – دعم العملة الورقية بقيمتها من الذهب . ولقد أصبح هذا القانون ساري المفعول في عام 1879 . وقد أدى إلى ثقة أصحاب الأموال في العملة الأمريكية ، ولكنها أثرت على المدينين .

حزب الدولار الأخضر

بدأ هذا الحزب عام 1875 للتعبير عن رغبات المستدينين الذين طالبوا بزيادة العرض من العملة الورقية . ففي عام 1878 ، اتخذت فئات العمال فيما بينها، لتكون (حزب الدولار الأخضر للعمال) . وقد كان برنامج هذا الحزب يطالب بزيادة استعمال الدولار الأخضر ، وحرية طبع الفضة واستعمالها لتصبح هذه ذات مفعولية كالذهب ، وفي عام 1878 – في أعلى درجات نجاحه ، استطاع هذا الحزب أن ينتخب خمسة عشر ممثلا لهم في الكونجرس ، وكذلك كثيرا من الرسميين في الولايات .

أزمة الزراعة بعد الحرب : الرخاء الذي تمتع به المزارعون أثناء الحرب الأهلية سرعان ما انتهى بنهاية الحرب . وكانت الأزمة الإقتصادية العالمية عام 1873 قد زادت من انخفاض الأسعار . في الواقع هذه الأسعار ظلت في انخفاض مستمر حتى عام 1896 . كما أن قلة المعروض من العملة الورقية ؛ زادا لطين بلة بالنسبة للمزارعين ، خصوصا مع زيادة الإنتاج الزراعي . في ذلك الوقت كانت تستصلح أراض زراعية جديدة في كندا ، أستراليا ، الأرجنتين ، وروسيا . ولقد اعتقد المزارعون بأن الأزمة إنما هي قلة الإستهلاك التي تسببت عن زيادة الطلب .

الجرينجرز (Grangers) : قام موظف في وزارة الزراعة الأمريكية يدعى أوفيفر كلي بنظيم جماعة سميت (أصحاب الزراعة) (Patrons of Husbandry) وكان اسمها الشعبي (الجرينجرز) . وقد بدأت هذه كهيئة سرية تعمل على محاولة تثقيف المزارعين وعائلاتهم . وبعد أزمة عام 1873 الإقتصادية وما صاحبها من انخفاض في أسعار المنتجات الزراعية ، أصبحت هذه حركة سياسية . لقد حمل هؤلاء مسئولية الضعف في حالة الفلاح الإقتصادية على أصحاب المصالح وأصحاب العمل ؛ كما أنها عارضت ما سمته باحتكارات البائعين للأدوات الزراعية وزيادة أسعارها على المزارعين ، وكذلك حملوا الوسطاء التجاريين المسئولية لزيادتهم أسعار الحاجيات في الوقت الذي تصل فيه إلى المستهلك – نظرا لزيادة ما يتقاضوه من عمولة ؛ كما ألقوا المسئولية على شركات السكة الحديدية في التسبب في كثير من مشاكل البلاد الإقتصادية .

وأصبحت لهذا الحزب قوة سياسية عامة . وأصبح لأعضائه تأثير كاف في معظم الولايات ، بحيث تمكنوامن الضغط على حكومات الولايات والكونجرس في الموافقة على سن قوانين خاصة بتنظيم السكة الحديدية ومخازن الحنطة . ونتيجة لهذه الجهود ، فقد أمكن خلق لجان في الكونجرس لتعمل على تنظيم هذه الأمور – السكة الحديدية ومخازن الحنطة – في الولايات أيضا . بالإضافة إلى نشاطات هذا الحزب السياسية والإجتماعية ، قام بتكوين جمعيات تعاونية للمستهلكين والمنتجين ، وعلى الرغم من فشل هذه الجمعيات سبب عدم خبرة المسئولين عنها ؛ إلا أن ذلك كان تجربة لهم للنجاح في المستقبل في مثل هذه المشاريع . لقد وصل حزب الجرينجرز أعلى مراحل نجحه في عام 1879 ، إلا أنه لايزال – إلى الآن – يعتبر من أشهر جمعيات المزارعين في أمريكا .

انتخابات عام 1876

فشلت محاولة الجمهوريين في إعادة انتخاب جرانت لمرة ثالثة ، وهكذا أصبحت الطريق مفتوحة أمام مرشح الجمهوريين جيمس بي . بلين . وكان من الممكن لهذا أن يحوز على الترشيح عن الحزب الجمهوري لولا اتهامه بقبول رشوة من أصحاب مصالح السكك الحديدية ، ومحاولة تأثيره على الكونجرس في الموافقة على منح أراضي حكومية للسكك الحديدية عام 1866 م . وهكذا فقد استقر رأي الجمهوريين على ترشيح رذر فوردهيز ، حاكم أوهايو ، وقد كان معروفا بأنه من الأحرار الجمهوريين ومن أبطال الحرب الأهلية . في حين أراد الحزب الديمقراطي أن يعبر عن مشاعر العصر ، وضرورة العمل على إصلاحات جديدة لازمة ، ولذلك فقدا ختار صامويل جي . تلدن ، حاكم ولاية نيويورك ، الذي اشتهر بعد فضحه لعصابة تويد في مدينة نيويورك . نتيجة الإنتخاب في هذا العام سببت أكبر نزاع ظهر بخصوص نتائج الإنتخابات في تاريخ الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية . لقد حصل تلدن على 184 صوتا ناخبا ، وتقدم ب 246 ألف صوت شعبي على هيز الذي حصل على 165 صوتا ناخبا ، ولكن ظهر نزاع حول عشرين صوتا ناخبا – إلى أي منهما تؤول هذه الأصوات ؟ منها 19 صوتا في الولايات الجنوبية الثلاثة : لويزيانا ، ساوث كارولاينا ، فلوريدا ، فحتى ينجح هيز لابد له من أن يحصل على كل الأصوات الناخبة في هذه الولايات . أما الولايات الثلاثة نفسها فقد قدمت لائحتين من نتائج الإنتخابات فيها : واحد لصالح الجمهوريين والأخرى لصالح الديمقراطيين . إذن من الوضاح أن نتيجة الإنتخاب – دون حساب الأصوات المتنازع عليها – تؤيد تلدن ، وما لم يحصل هيز على كل الأصوات المتنازع عليها ، فإنه سيخسر الإنتخابات .

لم يكن هناك سابقة للكونجرس بأن تعالج مثل هذا النزاع ، ولذلك فقد استقر الراي على تأليف لجنة تسمى (لجنة الإنتخاب) ، وتتكون من خمسة عشر عضوا مقسمة بالتساوي بني مجلس النواب ، والشيوخ ، ثم المحكمة العليا . من حيث الموالاة الجنوبية لهؤلاء الأعضاء ؛ كان سبعةمنهم من الجمهوريين وسبعة من الديمقراطيين وواحد مستقل . وعندما استقال العوض المستقل الذي كان ممثلا من المحكمة الإتحادية ، اختير مكانه عضو ينتمي إلى الحزب الجمهوري ؛ حيث إن باقي قضاة المحكمة كانوا من الجمهوريين . هذا الصوت الجمهوري أعطى كل نقطة في النزاع لصالح الجمهوريين . وقد حسم النزاع بأيام معدودة قبل تسلم الرئيس الجديد لمهامه .

كان حسم هذا النزاع مبنيا على مساومة سياسية بين الحزبين . موافقة الحزب الديمقراطي على إعطاء نتيجة الإنتخاب لهيز – الجمهوري – في مقابل تعهد الرئيس بسحب القوات الفدرالية المتبقية في كل من ولايات : لويزيانا ، ساوث كارولاينا ، وفلوريدا . وهكذا انتهت فترة عهد التعمير في أمريكا – بانسحاب بقية القوات الفدرالية من الجنوب .

تسلسل تاريخي للأحداث الهامة

- 1896: فشل المحاولة لضم سانتو دومنجو .

- 1870: فشلت المحاولة الثانية لضم كندا .

- 1871: معاهدة واشنطن (بين أمريكا وبريطانيا حلت المشاكل المعلقة ، خصوصا طلب التعويضات بسبب ألباما) (المدمرة الكونفدرالية) .

- 1876: النزاع على نتيجة الإنتخاب .

- 1876: انسحاب القوات الفدرالية من الجنوب .

بعد الرئاسة

جولته حول العالم

بعد نهاية فترته الرئاسية الثانية في البيت الأبيض، أمضى جرانت أكثر من عامين في رحلة حول العالم مع زوجته. في بريطانيا حيته حشود هائلة. ودُعي جرانت وأسرته للعشاء مع الملكة ڤيكتوريا في قلعة ونزر ومع الأمير بسمارك في ألمانيا. ثم اتجه شرقاً إلى روسيا ثم مصر. وفي مصر قابل ضباط الجيش الكونفدرالي الفارين إلى مصر والذين كانوا يعملون في جيش الخديوي إسماعيل، ودعاهم للعودة إلى الولايات المتحدة. ثم اتجه إلى الأراضي المقدسة ثم سيام (تايلند) وبورما.[226]

في اليابان، استقبلهم الإمبراطور مـِيجي والامبراطورة شوكن في القصر الامبراطوري. Today in the Shibakoen section of Tokyo, a tree still stands that Grant planted during his stay. وفي 1879، أعلنت حكومة الميجي باليابان ضم جزر ريوكيو. وقد احتجت الصين، وقد طـُلِب من جرانت التوسط في القضية. وقد قرر أن حق اليابان في الجزر أقوى وحكم لصالح اليابان.

محاولته الترشح لفترة ثالثة

افلاسه

الرحلة حول العالم كانت مكلفة، بالرغم من أنها كانت ناجحة. الأمر الذي تسبب في افلاسه.

انظر أيضاً

- Grantism

- Grant's Farm

- تاريخ الولايات المتحدة (1865–1918)

- List of American Civil War generals

- U.S. Grant Home, Galena, Illinois

- Ulysses S. Grant Memorial

- Western Theater of the American Civil War

هوامش

- ^ Utter 2015, p. 141.

- ^ "Religious Affiliation of U.S. Presidents". adherents.com.

- ^ Simpson, Brooks D. (2000). Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph over Adversity, 1822-1865. New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 3. ISBN 0-395-65994-9.

- ^ Brands 2012a, p. 636.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Simon 1967, p. 4.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 12; Smith 2001, pp. 24, 83; Simon 1967, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Garland 1898.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 12; Smith 2001, pp. 24, 83; Simon 1967, pp. 3–4; Kahan 2018, p. 2.

- ^ White 2016, p. 30.

- ^ Simpson 2014, p. 13–14; Smith 2001, pp. 26–28.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 10.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 27; McFeely 1981, pp. 16–17.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 16–17; Smith 2001, pp. 26–27.

- ^ White 2016, p. 41.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 27; Longacre 2006, p. 21; Cullum 1850, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 28; McFeely 1981, pp. 16, 19.

- ^ Jones 2011, p. 1580.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 28–29; Brands 2012a, p. 15; Chernow 2017, p. 81.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 28–29.

- ^ أ ب Smith 2001, pp. 30–33.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 61–62; White 2016, p. 102; Waugh 2009, p. 33.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 62; Smith 2001, p. 73; Flood 2005, p. 2007.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 62.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 73–74; Waugh 2009, p. 33; Chernow 2017, p. 62; White 2016, p. 102.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 73.

- ^ Simpson 2014, p. 49.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 35–37; Brands 2012a, pp. 15–17.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 30–31; Brands 2012a, p. 23.

- ^ أ ب White 2016, p. 80.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 33–34; Brands 2012a, p. 37.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 41–42.

- ^ أ ب McFeely 1981, p. 36.

- ^ White 2016, p. 66; Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War 2013, p. 271.

- ^ Simpson 2014, p. 44; Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War 2013, p. 271.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 67–68, 70, 73; Brands 2012a, pp. 49–52.

- ^ White 2016, p. 75.

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War 2013, p. 271.

- ^ Simpson 2014, p. 458; Chernow 2017, p. 58.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 30—31, 37–38.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 85, 96; Chernow 2017, p. 46.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 65.

- ^ أ ب Smith 2001, p. 76–78; Chernow 2017, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 74.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 78; Chernow 2017, p. 75.

- ^ McFeely 1981; Chernow 2017.

- ^ White 2016, p. 487; Chernow 2017, p. 78.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 52; Cullum 1891, p. 171; Chernow 2017, p. 81.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 81–83.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 55; Chernow 2017, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 85.

- ^ Cullum 1891, p. 171; Chernow 2017, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Cullum 1891, p. 171; Chernow 2017, pp. 85–86.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 55.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 87.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 88.

- ^ Farina 2007, p. 202.

- ^ Farina 2007, pp. 13, 202; Dorsett 1983.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 86–87; White 2016, pp. 118–120; McFeely 1981, p. 55.

- ^ Longacre 2006, pp. 55–58.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 87–88; Lewis 1950, pp. 328–332.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 95, 106; Simon 2002, p. 242; McFeely 1981, p. 60–61; Brands 2012a, pp. 94–96.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 58–60; White 2016, p. 125.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 61.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 58–60; Chernow 2017, p. 94.

- ^ Brands 2012a, p. 96.

- ^ White 2016, p. 128.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 62; Brands 2012a, p. 86; White 2016, p. 128.

- ^ Brands 2012a; White 2016.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 95, 109-110.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 94–95; White 2016, p. 130.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 94–95; McFeely 1981, p. 69; White 2016, p. 130.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 64; Brands 2012a, pp. 89–90; White 2016, pp. 129–131.

- ^ White 2016, p. 131; Simon 1969, pp. 4–5.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 65–66; White 2016, pp. 133, 136.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 135–37.

- ^ White 2016, p. 140.

- ^ Brands 2012a, p. 121.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 99.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 140–43; Brands 2012a, pp. 121–22; McFeely 1981, p. 73; Bonekemper 2012, p. 17; Smith 2001, p. 99; Chernow 2017, p. 125.

- ^ Brands 2012a, p. 123.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 122–123; McFeely 1981, p. 80; Bonekemper 2012.

- ^ "Battle Unit Details - the Civil War". U.S. National Park Service.

- ^ Flood 2005, pp. 45–46; Smith 2001, p. 113; Bonekemper 2012, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Bonekemper 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 117–18; Bonekemper 2012, p. 21.

- ^ White 2016, p. 159; Bonekemper 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Flood 2005, p. 63; White 2016, p. 159; Bonekemper 2012, p. 21.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 91; Chernow 2017, pp. 153–155.

- ^ أ ب White 2016, p. 168.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 169–171.

- ^ White 2016, p. 172.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 172–173; Groom 2012, pp. 94, 101–103.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 92–94.

- ^ White 2016, p. 168; McFeely 1981, p. 94.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 138–142; Groom 2012, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 146.

- ^ Axelrod 2011, p. 210.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 141–164; Brands 2012a, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Groom 2012, pp. 138, 143–144.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 164–165; Smith 2001, pp. 125–134.

- ^ White 2016, p. 210; Barney 2011, p. 287.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 111–112; Groom 2012, p. 63; White 2016, p. 211.

- ^ Groom 2012, pp. 62–65; McFeely 1981, p. 112.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 111; Bonekemper 2012, pp. 51, 94; Barney 2011, p. 287.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Bonekemper 2012, pp. 51, 58–59, 63–64.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 114; Flood 2005, pp. 109, 112; Bonekemper 2012, pp. 51, 58–59, 63–64.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 205.

- ^ Bonekemper 2012, pp. 59, 63–64; Smith 2001, p. 206.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 115–16.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 115.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 187–88.

- ^ Bonekemper 2012, p. 94; White 2016, p. 221.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Kaplan 2015, pp. 1109–1119; White 2016, pp. 223–225.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 188–191; White 2016, pp. 230–231.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 204; Barney 2011, p. 289.

- ^ White 2016, p. 229.

- ^ White 2016, p. 230; Groom 2012, pp. 363–364.

- ^ Longacre 2006, p. 137; White 2016, p. 231.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Badeau 1887, p. 126.

- ^ Flood 2005, p. 133.

- ^ White 2016, p. 243; Miller 2019, p. xii; Chernow 2017, p. 236.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 221–223; Catton 2005, p. 112; Chernow 2017, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Flood 2005, pp. 147–148; White 2016, p. 246; Chernow 2017, pp. 238–239.

- ^ White 2016, p. 248; Chernow 2017, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 239.

- ^ Catton 2005, pp. 119, 291; White 2016, pp. 248–249; Chernow 2017, pp. 239–241.

- ^ Bonekemper 2012, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 248.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 244.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 206–209.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 209–210.

- ^ White 2016; Miller 2019, p. 154–155.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 225; White 2016, pp. 235–36.

- ^ أ ب Chernow 2017, p. 232.

- ^ Flood 2005, pp. 143–144, 151; Sarna 2012a, p. 37; White 2016, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 259.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 232–33; Howland 1868, pp. 123–24.

- ^ Brands 2012a, p. 218; Shevitz 2005, p. 256.

- ^ Sarna 2012b.

- ^ Sarna 2012a, pp. 89, 147; White 2016, p. 494; Chernow 2017, p. 236.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 236.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Bonekemper 2012, pp. 148–149.

- ^ White 2016, p. 269.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 226–228.

- ^ Flood 2005, p. 160.

- ^ Flood 2005, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 231.

- ^ أ ب McFeely 1981, p. 136.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 122–138; Smith 2001, pp. 206–257.

- ^ Catton 1968, p. 8.

- ^ Catton 1968, p. 7.

- ^ Brands 2012a, p. 265; Cullum 1891, p. 172; White 2016, p. 295.

- ^ Flood 2005, p. 196.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 145–147; Smith 2001, pp. 267–268; Brands 2012a, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Flood 2005, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Flood 2005, p. 216.

- ^ Flood 2005, pp. 217–218.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 148–150.

- ^ Flood 2005, p. 232; McFeely 1981, p. 148; Cullum 1891, p. 172.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 313, 319.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 339, 342.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 343–44, 352.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 156; Chernow 2017, p. 352.

- ^ Wheelan 2014, p. 20; Simon 2002, p. 243; Chernow 2017, pp. 356–357.

- ^ Catton 2005, pp. 190, 193; Wheelan 2014, p. 20; Chernow 2017, pp. 348, 356–357.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 157; Wheelan 2014, p. 20; Chernow 2017, p. 356–357.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 157–175; Smith 2001, pp. 313–339, 343–368; Wheelan 2014, p. 20; Chernow 2017, pp. 356–57.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 355.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 378.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 396–97.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 303, 314; Chernow 2017, pp. 376–77.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 314; Chernow 2017, pp. 376–77.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 378–79, 384; Bonekemper 2012, p. 463.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 165.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 385–87, 394–95; Bonekemper 2012, p. 463.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 389, 392–95.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 169.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 403–04; Bonekemper 2011.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 170–171; Furgurson 2007, p. 235; Chernow 2017, p. 403.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 403.

- ^ Furgurson 2007, pp. 120–21.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 403–04.

- ^ Bonekemper 2011, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 406–07.

- ^ Bonekemper 2010, p. 182; Chernow 2017, p. 407.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 157–175; Smith 2001, pp. 313–339, 343–368.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 178–186.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 414; White 2016, pp. 369–370.

- ^ أ ب Catton 1968, p. 309.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 429.

- ^ Catton 1968, p. 324.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 398.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 179; Smith 2001, pp. 369–395; Catton 1968, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Catton 1968, p. 325.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 430.

- ^ Catton 2005, pp. 223, 228; Smith 2001, p. 387.

- ^ Catton 2005, p. 235; Smith 2001, pp. 388–389.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 388–389.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 389–390.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 390.

- ^ Bonekemper 2012, p. 359.

- ^ Bonekemper 2012, p. 353.

- ^ Bonekemper 2012, pp. 365–366.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 403–404.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 401–403.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 504; Smith 2001, pp. 401–03.

- ^ White 2016, p. 405.

- ^ Smith 2001.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 405–406.

- ^ Goethals 2015, p. 92; Smith 2001, p. 405.

- ^ White 2016, p. 407.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 212, 219–220; Catton 2005, p. 304; Chernow 2017, p. 510.

- ^ Catton, Bruce (1969). Grant Takes Command. pp. 475–480.

- ^ Eicher, Civil War High Commands, p. 264.

- ^ McFeely, Grant 459–460

المصادر

Chapter 20 1. Allan Nevins. Hamilton Fish: the Inner History of the Grant Administration (1965) 2. W.B. Hesseltine. Ulysses S. Grant (1935) 3. James Bryce. The American Commonwealth (1888) 4. Mathew Josphson. The Politicos (1938)

- Catton, Bruce, Grant Takes Command, Little, Brown and Company, 1968, Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 69-12632.

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Fuller, Maj. Gen. J. F. C., Grant and Lee, A Study in Personality and Generalship, Indiana University Press, 1957, ISBN 0-253-13400-5.

- Garland, Hamlin, Ulysses S. Grant: His Life and Character, Macmillan Company, 1898.

- Gott, Kendall D., Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry—Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862, Stackpole books, 2003, ISBN 0-8117-0049-6.

- Grant, Ulysses S., Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885-86, ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- Hesseltine, William B., Ulysses S. Grant: Politician 1935.

- Lewis, Lloyd, Captain Sam Grant, Little, Brown, and Co., 1950, ISBN 0-316-52348-8.

- McFeely, William S., Grant: A Biography, W. W. Norton & Co, 1981, ISBN 0-393-01372-3.

- McPherson, James M., Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States), Oxford University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Nevin, David, and the Editors of Time-Life Books, The Road to Shiloh: Early Battles in the West, Time-Life Books, 1983, ISBN 0-8094-4716-9.

- Simpson, Brooks D., Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822-1865, Houghton Mifflin, 2000, ISBN 0-395-65994-9.

- Smith, Jean Edward, Grant, Simon and Shuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- Woodworth, Steven E., Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861 - 1865, Alfred A. Knopf, 2005, ISBN 0-375-41218-2.

- Official Ulysses Simpson Grant biography from the US Army Center for Military History

المراجع

سياسية

- Bunting III, Josiah. Ulysses S. Grant (2004) ISBN 0-8050-6949-6

- William Dunning, Reconstruction Political and Economic 1865-1877 (1905), vol 22

- Hesseltine, William B. Ulysses S. Grant, Politician (2001) ISBN 1-931313-85-7 online edition

- Mantell, Martin E., Johnson, Grant, and the Politics of Reconstruction (1973) online edition

- Nevins, Allan, Hamilton Fish: The Inner History of the Grant Administration (1936) online edition

- Rhodes, James Ford., History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896. Volume: 6 and 7 (1920) vol 6

- Scaturro, Frank J., President Grant Reconsidered (1998).

- Schouler, James., History of the United States of America: Under the Constitution vol. 7. 1865-1877. The Reconstruction Period (1917) online edition

- Simpson, Brooks D., Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and Reconstruction, 1861-1868 (1991).

- Simpson, Brooks D., The Reconstruction Presidents (1998)

- Simpson, Brooks D., Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph over Adversity, 1822-1865 (2000)

- Skidmore, Max J. "The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant: a Reconsideration." White House Studies (2005) online

دراسات عسكرية

- Badeau, Adam. Military History of Ulysses S. Grant, from April, 1861, to April, 1865. 3 vols. 1882.

- Ballard, Michael B., Vicksburg, The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi, University of North Carolina Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8078-2893-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C., The Vicksburg Campaign, 3 volumes, Morningside Press, 1991, ISBN 0-89029-308-2.

- Carter, Samuel III, The Final Fortress: The Campaign for Vicksburg, 1862-1863 (1980)

- Catton, Bruce, Grant Moves South, 1960, ISBN 0-316-13207-1; Grant Takes Command, 1968, ISBN 0-316-13210-1; U. S. Grant and the American Military Tradition (1954)

- Cavanaugh, Michael A., and William Marvel, The Petersburg Campaign: The Battle of the Crater: "The Horrid Pit," June 25-August 6, 1864 (1989)

- Conger, A. L. The Rise of U.S. Grant (1931)

- Davis, William C. Death in the Trenches: Grant at Petersburg (1986).

- Fuller, Maj. Gen. J. F. C., Grant and Lee, A Study in Personality and Generalship, Indiana University Press, 1957, ISBN 0-253-13400-5.

- Gott, Kendall D., Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry-Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862, Stackpole Books, 2003, ISBN 0-8117-0049-6.

- Korda, Michael. Ulysses S. Grant: The Unlikely Hero (2004) 161 pp

- McWhiney, Grady, Battle in the Wilderness: Grant Meets Lee (1995)

- McDonough, James Lee, Shiloh: In Hell before Night (1977).

- McDonough, James Lee, Chattanooga: A Death Grip on the Confederacy (1984).

- Maney, R. Wayne, Marching to Cold Harbor. Victory and Failure, 1864 (1994).

- Matter, William D., If It Takes All Summer: The Battle of Spotsylvania (1988)

- Miers, Earl Schenck., The Web of Victory: Grant at Vicksburg. 1955.

- Mosier, John., "Grant", Palgrave MacMillan, 2006 ISBN 1-4039-7136-6.