جيمس پولك

جيمس نوكس پولك | |

|---|---|

James Knox Polk | |

Daguerreotype of President Polk, taken by Matthew Brady or John Plumbe | |

| رئيس الولايات المتحدة الحادي عشر | |

| في المنصب 4 مارس, 1845 – 4 مارس, 1849 | |

| نائب الرئيس | جورج م. دالاس (1845-1849) |

| سبقه | جون تايلر |

| خلـَفه | زكاري تايلور |

| حاكم تنسي الحادي عشر | |

| في المنصب 14 اكتوبر, 1839 – 15 اكتوبر, 1841 | |

| سبقه | Newton Cannon |

| خلـَفه | James Chamberlain Jones |

| الناطق باسم مجلس نواب الولايات المتحدة السابع عشر | |

| في المنصب 7 ديسمبر, 1835 – 4 مارس, 1839 | |

| الرئيس | أندرو جاكسون مارتن ڤان بيورن |

| سبقه | John Bell |

| خلـَفه | Robert M. T. Hunter |

| عضو U.S. House of Representatives from تنسي's 6th district | |

| في المنصب 4 مارس, 1825 – 3 مارس, 1833 | |

| سبقه | John A. Cocke |

| خلـَفه | بالي پيتون |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives من تنسي's 9th district | |

| في المنصب 4 مارس, 1833 – 3 مارس, 1839 | |

| سبقه | وليام فيتزجرالد |

| خلـَفه | Harvey M. Watterson |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | نوفمبر 2, 1795 پاينڤيل، نورث كارولينا |

| توفي | يونيو 15, 1849 (aged 53) ناشڤيل، تنسي |

| القومية | American (US) |

| الحزب | الديمقراطي |

| المدرسة الأم | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

| الوظيفة | محامي, مزارع (Planter) |

| التوقيع | |

جيمس نوكس پولك (James Knox Polk ؛ /poʊk/;[1] November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) كان الرئيس الأمريكي الحادي عشر في الفترة من 1845 إلى 1849. كان من أتباع أندرو جاكسون وعضو في الحزب الديمقراطي، وداعية إلى الديمقراطية الجاكسونية ولتوسيع رقعة الولايات المتحدة. قاد بولك الولايات المتحدة في الحرب الأمريكية المكسيكية، وبعد الانتصار في تلك الحرب، قام بضم جمهورية تكساس وإقليم أوريجون وفصم المكسيك. ويُعَد واحدًا من أنجح الرؤساء الأمريكان؛ فقد قام بتنفيذ جميع بنود برنامجه السياسي.

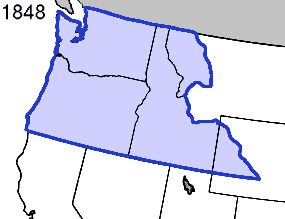

تولى بولك قيادة الولايات المتحدة في الفترة التي شهدت أعظم عملية توسع لحدود البلاد. ففي أثناء رئاسته، استولت الولايات المتحدة على معظم المساحة التي تكون الآن تسع ولايات في الغرب، وأصبحت تكساس ولاية أمريكية. كذلك أدار بولك الحرب المكسيكية بنجاح (1846 – 1848). وحاز عن طريقها القدر الأكبر من هذه الأراضي، بما فيها كاليفورنيا. قام بولك أيضًا بتسوية نزاع حدودي مع المملكة المتحدة حول أراضي أوريجون. خفف بولك التعريفة الجمركية وأنشأ خزانة فيدرالية مستقلة. ولد بولك بالقرب من باينفيل شمالي كارولينا بالولايات المتحدة. وكان محاميًا وزعيمًا سياسيًا في ولاية تنيسي.

After building a successful law practice in Tennessee, Polk was elected to its state legislature in 1823 and then to the United States House of Representatives in 1825, becoming a strong supporter of Jackson. After serving as chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, he became Speaker of the House in 1835, the only person to serve both as Speaker and U.S. president. Polk left Congress to run for governor of Tennessee, winning in 1839 but losing in 1841 and 1843. He was a dark-horse candidate in the 1844 presidential election as the Democratic Party nominee; he entered his party's convention as a potential nominee for vice president but emerged as a compromise to head the ticket when no presidential candidate could gain the necessary two-thirds majority. In the general election, Polk narrowly defeated Henry Clay of the Whig Party and pledged to serve only one term.

After a negotiation fraught with the risk of war, Polk reached a settlement with Great Britain over the disputed Oregon Country, with the territory for the most part divided along the 49th parallel. He oversaw victory in the Mexican–American War, resulting in Mexico's cession of the entire American Southwest. He secured a substantial reduction of tariff rates with the Walker tariff of 1846. The same year, he achieved his other major goal, reestablishment of the Independent Treasury system. True to his campaign pledge to serve one term (one of the few U.S. presidents to make and keep such a pledge), Polk left office in 1849 and returned to Tennessee, where he died of cholera soon afterward.

Though he has become relatively obscure, scholars have ranked Polk in the upper tier of U.S. presidents, mostly for his ability to promote and achieve the major items on his presidential agenda. At the same time, he has been criticized for leading the country into a war with Mexico that exacerbated sectional divides. A property owner who used slave labor, he kept a plantation in Mississippi and increased his slave ownership during his presidency. Polk's policy of territorial expansion saw the nation reach the Pacific coast and almost all its contiguous borders. He helped make the U.S. a nation poised to become a world power, but with divisions between free and slave states gravely exacerbated, setting the stage for the Civil War.

Early life

James Knox Polk was born on November 2, 1795, in a log cabin in Pineville, North Carolina.[2] He was the first of 10 children born into a family of farmers.[3] His mother Jane named him after her father, James Knox.[2] His father Samuel Polk was a farmer, slaveholder, and surveyor of Scots-Irish descent. The Polks had immigrated to America in the late 17th century, settling initially on the Eastern Shore of Maryland but later moving to south-central Pennsylvania and then to the Carolina hill country.[2]

The Knox and Polk families were Presbyterian. While Polk's mother remained a devout Presbyterian, his father, whose own father Ezekiel Polk was a deist, rejected dogmatic Presbyterianism. He refused to declare his belief in Christianity at his son's baptism, and the minister refused to baptize young James.[2][4] Nevertheless, James' mother "stamped her rigid orthodoxy on James, instilling lifelong Calvinistic traits of self-discipline, hard work, piety, individualism, and a belief in the imperfection of human nature", according to James A. Rawley's American National Biography article.[3]

In 1803, Ezekiel Polk led four of his adult children and their families to the Duck River area in what is now Maury County, Tennessee; Samuel Polk and his family followed in 1806. The Polk clan dominated politics in Maury County and in the new town of Columbia. Samuel became a county judge, and the guests at his home included Andrew Jackson, who had already served as a judge and in Congress.[5][أ] James learned from the political talk around the dinner table; both Samuel and Ezekiel were strong supporters of President Thomas Jefferson and opponents of the Federalist Party.[6]

Polk suffered from frail health as a child, a particular disadvantage in a frontier society. His father took him to see prominent Philadelphia physician Dr. Philip Syng Physick for urinary stones. The journey was broken off by James's severe pain, and Dr. Ephraim McDowell of Danville, Kentucky, operated to remove them. No anesthetic was available except brandy. The operation was successful, but it may have left James impotent or sterile, as he had no children. He recovered quickly and became more robust. His father offered to bring him into one of his businesses, but he wanted an education and enrolled at a Presbyterian academy in 1813.[7] He became a member of the Zion Church near his home in 1813 and enrolled in the Zion Church Academy. He then entered Bradley Academy in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where he proved a promising student.[8][9][10]

In January 1816, Polk was admitted into the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as a second-semester sophomore. The Polk family had connections with the university, then a small school of about 80 students; Samuel was its land agent in Tennessee and his cousin William Polk was a trustee.[11] Polk's roommate was William Dunn Moseley, who became the first Governor of Florida. Polk joined the Dialectic Society where he took part in debates, became its president, and learned the art of oratory.[12] In one address, he warned that some American leaders were flirting with monarchical ideals, singling out Alexander Hamilton, a foe of Jefferson.[13] Polk graduated with honors in May 1818.[12]

After graduation, Polk returned to Nashville, Tennessee to study law under renowned trial attorney Felix Grundy,[14] who became his first mentor. On September 20, 1819, he was elected clerk of the Tennessee State Senate, which then sat in Murfreesboro and to which Grundy had been elected.[15] He was re-elected clerk in 1821 without opposition, and continued to serve until 1822. In June 1820, he was admitted to the Tennessee bar, and his first case was to defend his father against a public fighting charge; he secured his release for a one-dollar fine.[15] He opened an office in Maury County[3] and was successful as a lawyer, due largely to the many cases arising from the Panic of 1819, a severe depression.[16] His law practice subsidized his political career.[17]

السيرة السياسية المبكرة

المشرّع بولاية تنسي

By the time the legislature adjourned its session in September 1822, Polk was determined to be a candidate for the Tennessee House of Representatives. The election was in August 1823, almost a year away, allowing him ample time for campaigning.[18] Already involved locally as a member of the Masons, he was commissioned in the Tennessee militia as a captain in the cavalry regiment of the 5th Brigade. He was later appointed a colonel on the staff of Governor William Carroll, and was afterwards often referred to as "Colonel".[19][20] Although many of the voters were members of the Polk clan, the young politician campaigned energetically. People liked Polk's oratory, which earned him the nickname "Napoleon of the Stump". At the polls, where Polk provided alcoholic refreshments for his voters, he defeated incumbent William Yancey.[18][19]

Beginning in early 1822, Polk courted Sarah Childress—they were engaged the following year[22] and married on January 1, 1824, in Murfreesboro.[18] Educated far better than most women of her time, especially in frontier Tennessee, Sarah Polk was from one of the state's most prominent families.[18] During James's political career Sarah assisted her husband with his speeches, gave him advice on policy matters, and played an active role in his campaigns.[23] Rawley noted that Sarah Polk's grace, intelligence and charming conversation helped compensate for her husband's often austere manner.[3]

Polk's first mentor was Grundy, but in the legislature, Polk came increasingly to oppose him on such matters as land reform, and came to support the policies of Andrew Jackson, by then a military hero for his victory at the Battle of New Orleans (1815).[24] Jackson was a family friend to both the Polks and the Childresses—there is evidence Sarah Polk and her siblings called him "Uncle Andrew"—and James Polk quickly came to support his presidential ambitions for 1824. When the Tennessee Legislature deadlocked on whom to elect as U.S. senator in 1823 (until 1913, legislators, not the people, elected senators), Jackson's name was placed in nomination. Polk broke from his usual allies, casting his vote for Jackson, who won. The Senate seat boosted Jackson's presidential chances by giving him current political experience[ب] to match his military accomplishments. This began an alliance[25] that would continue until Jackson's death early in Polk's presidency.[3] Polk, through much of his political career, was known as "Young Hickory", based on the nickname for Jackson, "Old Hickory". Polk's political career was as dependent on Jackson as his nickname implied.[26]

In the 1824 United States presidential election, Jackson got the most electoral votes (he also led in the popular vote) but as he did not receive a majority in the Electoral College, the election was thrown into the U.S. House of Representatives, which chose Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, who had received the second-most of each. Polk, like other Jackson supporters, believed that Speaker of the House Henry Clay had traded his support as fourth-place finisher (the House may only choose from among the top three) to Adams in a Corrupt Bargain in exchange for being the new Secretary of State. Polk had in August 1824 declared his candidacy for the following year's election to the House of Representatives from Tennessee's 6th congressional district.[27] The district stretched from Maury County south to the Alabama line, and extensive electioneering was expected of the five candidates. Polk campaigned so vigorously that Sarah began to worry about his health. During the campaign, Polk's opponents said that at the age of 29 Polk was too young for the responsibility of a seat in the House, but he won the election with 3,669 votes out of 10,440 and took his seat in Congress later that year.[28]

تلميذ جاكسون

When Polk arrived in Washington, D.C. for Congress's regular session in December 1825, he roomed in Benjamin Burch's boarding house with other Tennessee representatives, including Sam Houston. Polk made his first major speech on March 13, 1826, in which he said that the Electoral College should be abolished and that the president should be elected by popular vote.[29] Remaining bitter at the alleged Corrupt Bargain between Adams and Clay, Polk became a vocal critic of the Adams administration, frequently voting against its policies.[30] Sarah Polk remained at home in Columbia during her husband's first year in Congress, but accompanied him to Washington beginning in December 1826; she assisted him with his correspondence and came to hear James's speeches.[31]

Polk won re-election in 1827 and continued to oppose the Adams administration.[31] He remained in close touch with Jackson, and when Jackson ran for president in 1828, Polk was an advisor on his campaign. Following Jackson's victory over Adams, Polk became one of the new President's most prominent and loyal supporters.[32] Working on Jackson's behalf, Polk successfully opposed federally-funded "internal improvements" such as a proposed Buffalo-to-New Orleans road, and he was pleased by Jackson's Maysville Road veto in May 1830, when Jackson blocked a bill to finance a road extension entirely within one state, Kentucky, deeming it unconstitutional.[33] Jackson opponents alleged that the veto message, which strongly complained about Congress' penchant for passing pork barrel projects, was written by Polk, but he denied this, stating that the message was entirely the President's.[34]

Polk served as Jackson's most prominent House ally in the "Bank War" that developed over Jackson's opposition to the re-authorization of the Second Bank of the United States.[35] The Second Bank, headed by Nicholas Biddle of Philadelphia, not only held federal dollars but controlled much of the credit in the United States, as it could present currency issued by local banks for redemption in gold or silver. Some Westerners, including Jackson, opposed the Second Bank, deeming it a monopoly acting in the interest of Easterners.[36] Polk, as a member of the House Ways and Means Committee, conducted investigations of the Second Bank, and though the committee voted for a bill to renew the bank's charter (scheduled to expire in 1836), Polk issued a strong minority report condemning the bank. The bill passed Congress in 1832; however, Jackson vetoed it and Congress failed to override the veto. Jackson's action was highly controversial in Washington but had considerable public support, and he won easy re-election in 1832.[37]

Like most Southerners, Polk favored low tariffs on imported goods, and initially sympathized with John C. Calhoun's opposition to the Tariff of Abominations during the Nullification Crisis of 1832–1833, but came over to Jackson's side as Calhoun moved towards advocating secession. Thereafter, Polk remained loyal to Jackson as the President sought to assert federal authority. Polk condemned secession and supported the Force Bill against South Carolina, which had claimed the authority to nullify federal tariffs. The matter was settled by Congress passing a compromise tariff.[38]

رئاسة لجنة لجنة السبل والموارد والناطق بإسم مجلس النواب

In December 1833, after being elected to a fifth consecutive term, Polk, with Jackson's backing, became the chairman of Ways and Means, a powerful position in the House.[39] In that position, Polk supported Jackson's withdrawal of federal funds from the Second Bank. Polk's committee issued a report questioning the Second Bank's finances and another supporting Jackson's actions against it. In April 1834, the Ways and Means Committee reported a bill to regulate state deposit banks, which, when passed, enabled Jackson to deposit funds in pet banks, and Polk got legislation passed to allow the sale of the government's stock in the Second Bank.[3][40]

In June 1834, Speaker of the House Andrew Stevenson resigned from Congress to become Minister to the United Kingdom.[41] With Jackson's support, Polk ran for speaker against fellow Tennessean John Bell, Calhoun disciple Richard Henry Wilde, and Joel Barlow Sutherland of Pennsylvania. After ten ballots, Bell, who had the support of many opponents of the administration, defeated Polk.[42] Jackson called in political debts to try to get Polk elected Speaker of the House at the start of the next Congress in December 1835, assuring Polk in a letter he meant him to burn that New England would support him for speaker. They were successful; Polk defeated Bell to take the speakership.[43]

According to Thomas M. Leonard, "by 1836, while serving as Speaker of the House of Representatives, Polk approached the zenith of his congressional career. He was at the center of Jacksonian Democracy on the House floor, and, with the help of his wife, he ingratiated himself into Washington's social circles."[44] The prestige of the speakership caused them to move from a boarding house to their own residence on Pennsylvania Avenue.[44] In the 1836 presidential election, Vice President Martin Van Buren, Jackson's chosen successor, defeated multiple Whig candidates, including Tennessee Senator Hugh Lawson White. Greater Whig strength in Tennessee helped White carry his state, though Polk's home district went for Van Buren.[45] Ninety percent of Tennessee voters had supported Jackson in 1832, but many in the state disliked the destruction of the Second Bank, or were unwilling to support Van Buren.[46]

As Speaker of the House, Polk worked for the policies of Jackson and later Van Buren. Polk appointed committees with Democratic chairs and majorities, including the New York radical C. C. Cambreleng as the new Ways and Means chair, although he tried to maintain the speaker's traditional nonpartisan appearance. The two major issues during Polk's speakership were slavery and, after the Panic of 1837, the economy. Polk firmly enforced the "gag rule", by which the House of Representatives would not accept or debate citizen petitions regarding slavery.[47] This ignited fierce protests from John Quincy Adams, who was by then a congressman from Massachusetts and an abolitionist. Instead of finding a way to silence Adams, Polk frequently engaged in useless shouting matches, leading Jackson to conclude that Polk should have shown better leadership.[48] Van Buren and Polk faced pressure to rescind the Specie Circular, Jackson's 1836 order that payment for government lands be in gold and silver. Some believed this had led to the crash by causing a lack of confidence in paper currency issued by banks. Despite such arguments, with support from Polk and his cabinet, Van Buren chose to back the Specie Circular. Polk and Van Buren attempted to establish an Independent Treasury system that would allow the government to oversee its own deposits (rather than using pet banks), but the bill was defeated in the House.[47] It eventually passed in 1840.[49]

Using his thorough grasp of the House's rules,[50] Polk attempted to bring greater order to its proceedings. Unlike many of his peers, he never challenged anyone to a duel no matter how much they insulted his honor.[51] The economic downturn cost the Democrats seats, so that when he faced re-election as Speaker of the House in December 1837, he won by only 13 votes, and he foresaw defeat in 1839. Polk by then had presidential ambitions but was well aware that no Speaker of the House had ever become president (Polk is still the only one to have held both offices).[52] After seven terms in the House, two as speaker, he announced that he would not seek re-election, choosing instead to run for Governor of Tennessee in the 1839 election.[53]

حاكم تنسي

In 1835, the Democrats had lost the governorship of Tennessee for the first time in their history, and Polk decided to return home to help the party.[54] Tennessee was afire for White and Whiggism; the state had reversed its political loyalties since the days of Jacksonian domination. As head of the state Democratic Party, Polk undertook his first statewide campaign, He opposed Whig incumbent Newton Cannon, who sought a third two-year term as governor.[55] The fact that Polk was the one called upon to "redeem" Tennessee from the Whigs tacitly acknowledged him as head of the state Democratic Party.[3]

Polk campaigned on national issues, whereas Cannon stressed state issues. After being bested by Polk in the early debates, the governor retreated to Nashville, the state capital, alleging important official business. Polk made speeches across the state, seeking to become known more widely than just in his native Middle Tennessee. When Cannon came back on the campaign trail in the final days, Polk pursued him, hastening the length of the state to be able to debate the governor again. On Election Day, August 1, 1839, Polk defeated Cannon, 54,102 to 51,396, as the Democrats recaptured the state legislature and won back three congressional seats.[56]

Tennessee's governor had limited power—there was no gubernatorial veto, and the small size of the state government limited any political patronage. But Polk saw the office as a springboard for his national ambitions, seeking to be nominated as Van Buren's vice presidential running mate at the 1840 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore in May.[57] Polk hoped to be the replacement if Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson was dumped from the ticket; Johnson was disliked by many Southern whites for fathering two daughters by a biracial mistress and attempting to introduce them into white society. Johnson was from Kentucky, so Polk's Tennessee residence would keep the New Yorker Van Buren's ticket balanced. The convention chose to endorse no one for vice president, stating that a choice would be made once the popular vote was cast. Three weeks after the convention, recognizing that Johnson was too popular in the party to be ousted, Polk withdrew his name. The Whig presidential candidate, General William Henry Harrison, conducted a rollicking campaign with the motto "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too", easily winning both the national vote and that in Tennessee. Polk campaigned in vain for Van Buren[58] and was embarrassed by the outcome; Jackson, who had returned to his home, the Hermitage, near Nashville, was horrified at the prospect of a Whig administration.[59] In the 1840 election, Polk received one vote from a faithless elector in the Electoral College's vote for vice president.[60][61][62] Harrison's death after a month in office in 1841 left the presidency to Vice President John Tyler, who soon broke with the Whigs.[59]

Polk's three major programs during his governorship; regulating state banks, implementing state internal improvements, and improving education all failed to win the approval of the legislature.[63] His only major success as governor was his politicking to secure the replacement of Tennessee's two Whig U.S. senators with Democrats.[63] Polk's tenure was hindered by the continuing nationwide economic crisis that had followed the Panic of 1837 and which had caused Van Buren to lose the 1840 election.[64]

Encouraged by the success of Harrison's campaign, the Whigs ran a freshman legislator from frontier Wilson County, James C. Jones against Polk in 1841. "Lean Jimmy" had proven one of their most effective gadflies against Polk, and his lighthearted tone at campaign debates was very effective against the serious Polk. The two debated the length of Tennessee,[65] and Jones's support of distribution to the states of surplus federal revenues, and of a national bank, struck a chord with Tennessee voters. On election day in August 1841, Polk was defeated by 3,000 votes, the first time he had been beaten at the polls.[58] Polk returned to Columbia and the practice of law and prepared for a rematch against Jones in 1843, but though the new governor took less of a joking tone, it made little difference to the outcome, as Polk was beaten again,[66] this time by 3,833 votes.[67][68] In the wake of his second statewide defeat in three years, Polk faced an uncertain political future.[69]

انتخابات 1844

الترشيح الديمقراطي

Despite his loss, Polk was determined to become the next vice president of the United States, seeing it as a path to the presidency.[70] Van Buren was the frontrunner for the 1844 Democratic nomination, and Polk engaged in a careful campaign to become his running mate.[71] The former president faced opposition from Southerners who feared his views on slavery, while his handling of the Panic of 1837—he had refused to rescind the Specie Circular—aroused opposition from some in the West (modern Midwestern United States) who believed his hard money policies had hurt their section of the country.[71] Many Southerners backed Calhoun's candidacy, Westerners rallied around Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan, and former Vice President Johnson also maintained a strong following among Democrats.[71] Jackson assured Van Buren by letter that Polk in his campaigns for governor had "fought the battle well and fought it alone".[72] Polk hoped to gain Van Buren's support, hinting in a letter that a Van Buren/Polk ticket could carry Tennessee, but found him unconvinced.[73]

The biggest political issue in the United States at that time was territorial expansion.[3] The Republic of Texas had successfully revolted against Mexico in 1836. With the republic largely populated by American emigres, those on both sides of the Sabine River border between the U.S. and Texas deemed it inevitable that Texas would join the United States, but this would anger Mexico, which considered Texas a breakaway province, and threatened war if the United States annexed it. Jackson, as president, had recognized Texas independence, but the initial momentum toward annexation had stalled.[74] Britain was seeking to expand her influence in Texas: Britain had abolished slavery, and if Texas did the same, it would provide a western haven for runaways to match one in the North.[75] A Texas not in the United States would also stand in the way of what was deemed America's Manifest Destiny to overspread the continent.[76]

Clay was nominated for president by acclamation at the April 1844 Whig National Convention, with New Jersey's Theodore Frelinghuysen his running mate.[77] A Kentucky slaveholder at a time when opponents of Texas annexation argued that it would give slavery more room to spread, Clay sought a nuanced position on the issue. Jackson, who strongly supported a Van Buren/Polk ticket, was delighted when Clay issued a letter for publication in the newspapers opposing Texas annexation, only to be devastated when he learned Van Buren had done the same thing.[78] Van Buren did this because he feared losing his base of support in the Northeast,[79] but his supporters in the old Southwest were stunned at his action. Polk, on the other hand, had written a pro-annexation letter that had been published four days before Van Buren's.[3] Jackson wrote sadly to Van Buren that no candidate who opposed annexation could be elected, and decided Polk was the best person to head the ticket.[80] Jackson met with Polk at the Hermitage on May 13, 1844, and explained to his visitor that only an expansionist from the South or Southwest could be elected—and, in his view, Polk had the best chance.[81] Polk was at first startled, calling the plan "utterly abortive", but he agreed to accept it.[82] Polk immediately wrote to instruct his lieutenants at the convention to work for his nomination as president.[81]

Despite Jackson's quiet efforts on his behalf, Polk was skeptical that he could win.[83] Nevertheless, because of the opposition to Van Buren by expansionists in the West and South, Polk's key lieutenant at the 1844 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore, Gideon Johnson Pillow, believed Polk could emerge as a compromise candidate.[84] Publicly, Polk, who remained in Columbia during the convention, professed full support for Van Buren's candidacy and was believed to be seeking the vice presidency. Polk was one of the few major Democrats to have declared for the annexation of Texas.[85]

The convention opened on May 27, 1844. A crucial question was whether the nominee needed two-thirds of the delegate vote, as had been the case at previous Democratic conventions, or merely a majority. A vote for two-thirds would doom Van Buren's candidacy due to opposition from southern delegates.[86] With the support of the Southern states, the two-thirds rule was passed.[87] Van Buren won a majority on the first presidential ballot but failed to win the necessary two-thirds, and his support slowly faded.[87] Cass, Johnson, Calhoun and James Buchanan also received votes on the first ballot, and Cass took the lead on the fifth.[88] After seven ballots, the convention remained deadlocked: Cass could not reach two-thirds, and Van Buren's supporters became discouraged about his chances. Delegates were ready to consider a new candidate who might break the stalemate.[89]

When the convention adjourned after the seventh ballot, Pillow, who had been waiting for an opportunity to press Polk's name, conferred with George Bancroft of Massachusetts, a politician and historian and longtime Polk correspondent, who had planned to nominate Polk for vice president. Bancroft had supported Van Buren's candidacy and was willing to see New York Senator Silas Wright head the ticket, but as a Van Buren loyalist, Wright would not consent. Pillow and Bancroft decided if Polk were nominated for president, Wright might accept the second spot. Before the eighth ballot, former Attorney General Benjamin F. Butler, head of the New York delegation, read a pre-written letter from Van Buren to be used if he could not be nominated, withdrawing in Wright's favor. But Wright (who was in Washington) had also entrusted a pre-written letter to a supporter, in which he refused to be considered as a presidential candidate, and stated in the letter that he agreed with Van Buren's position on Texas. Had Wright's letter not been read he most likely would have been nominated, but without him, Butler began to rally Van Buren supporters for Polk as the best possible candidate, and Bancroft placed Polk's name before the convention. On the eighth ballot, Polk received only 44 votes to Cass's 114 and Van Buren's 104, but the deadlock showed signs of breaking. Butler formally withdrew Van Buren's name, many delegations declared for the Tennessean, and on the ninth ballot, Polk received 233 ballots to Cass's 29, making him the Democratic nominee for president. The nomination was then made unanimous.[3][90]

The convention then considered the vice-presidential nomination. Butler advocated for Wright, and the convention agreed, with only four Georgia delegates dissenting. Word of Wright's nomination was sent to him in Washington via telegraph. Having declined by proxy an almost certain presidential nomination, Wright also refused the vice-presidential nomination. Senator Robert J. Walker of Mississippi, a close Polk ally, then suggested former senator George M. Dallas of Pennsylvania. Dallas was acceptable enough to all factions and gained the nomination on the third ballot. The delegates passed a platform and adjourned on May 30.[91][92]

Many contemporary politicians, including Pillow and Bancroft, later claimed credit for getting Polk the nomination, but Walter R. Borneman felt that most of the credit was due to Jackson and Polk, "the two who had done the most were back in Tennessee, one an aging icon ensconced at the Hermitage and the other a shrewd lifelong politician waiting expectantly in Columbia".[93] Whigs mocked Polk with the chant "Who is James K. Polk?", affecting never to have heard of him.[94] Though he had experience as Speaker of the House and Governor of Tennessee, all previous presidents had served as vice president, Secretary of State, or as a high-ranking general. Polk has been described as the first "dark horse" presidential nominee, although his nomination was less of a surprise than that of future nominees such as Franklin Pierce or Warren G. Harding.[95] Despite his party's gibes, Clay recognized that Polk could unite the Democrats.[94]

الانتخابات العامة

Rumors of Polk's nomination reached Nashville on June 4, much to Jackson's delight; they were substantiated later that day. The dispatches were sent on to Columbia, arriving the same day, and letters and newspapers describing what had happened at Baltimore were in Polk's hands by June 6. He accepted his nomination by letter dated June 12, alleging that he had never sought the office, and stating his intent to serve only one term.[96] Wright was embittered by what he called the "foul plot" against Van Buren, and demanded assurances that Polk had played no part; it was only after Polk professed that he had remained loyal to Van Buren that Wright supported his campaign.[97] Following the custom of the time that presidential candidates avoid electioneering or appearing to seek the office, Polk remained in Columbia and made no speeches. He engaged in extensive correspondence with Democratic Party officials as he managed his campaign. Polk made his views known in his acceptance letter and through responses to questions sent by citizens that were printed in newspapers, often by arrangement.[98][99]

A potential pitfall for Polk's campaign was the issue of whether the tariff should be for revenue only, or with the intent to protect American industry. Polk finessed the tariff issue in a published letter. Recalling that he had long stated that tariffs should only be sufficient to finance government operations, he maintained that stance but wrote that within that limitation, government could and should offer "fair and just protection" to American interests, including manufacturers.[100] He refused to expand on this stance, acceptable to most Democrats, despite the Whigs pointing out that he had committed himself to nothing. In September, a delegation of Whigs from nearby Giles County came to Columbia, armed with specific questions on Polk's views regarding the current tariff, the Whig-passed Tariff of 1842, and with the stated intent of remaining in Columbia until they got answers. Polk took several days to respond and chose to stand by his earlier statement, provoking an outcry in the Whig papers.[101]

Another concern was the third-party candidacy of President Tyler, which might split the Democratic vote. Tyler had been nominated by a group of loyal officeholders. Under no illusions he could win, he believed he could rally states' rights supporters and populists to hold the balance of power in the election. Only Jackson had the stature to resolve the situation, which he did with two letters to friends in the Cabinet, that he knew would be shown to Tyler, stating that the President's supporters would be welcomed back into the Democratic fold. Jackson wrote that once Tyler withdrew, many Democrats would embrace him for his pro-annexation stance. The former president also used his influence to stop Francis Preston Blair and his Globe newspaper, the semi-official organ of the Democratic Party, from attacking Tyler. These proved enough; Tyler withdrew from the race in August.[102][103]

Party troubles were a third concern. Polk and Calhoun made peace when a former South Carolina congressman, Francis Pickens visited Tennessee and came to Columbia for two days and to the Hermitage for sessions with the increasingly ill Jackson. Calhoun wanted the Globe dissolved, and that Polk would act against the 1842 tariff and promote Texas annexation. Reassured on these points, Calhoun became a strong supporter.[104]

Polk was aided regarding Texas when Clay, realizing his anti-annexation letter had cost him support, attempted in two subsequent letters to clarify his position. These angered both sides, which attacked Clay as insincere.[105] Texas also threatened to divide the Democrats sectionally, but Polk managed to appease most Southern party leaders without antagonizing Northern ones.[106] As the election drew closer, it became clear that most of the country favored the annexation of Texas, and some Southern Whig leaders supported Polk's campaign due to Clay's anti-annexation stance.[106]

The campaign was vitriolic; both major party candidates were accused of various acts of malfeasance; Polk was accused of being both a duelist and a coward. The most damaging smear was the Roorback forgery; in late August an item appeared in an abolitionist newspaper, part of a book detailing fictional travels through the South of a Baron von Roorback, an imaginary German nobleman. The Ithaca Chronicle printed it without labeling it as fiction, and inserted a sentence alleging that the traveler had seen forty slaves who had been sold by Polk after being branded with his initials. The item was withdrawn by the Chronicle when challenged by the Democrats, but it was widely reprinted. Borneman suggested that the forgery backfired on Polk's opponents as it served to remind voters that Clay too was a slaveholder.[107] John Eisenhower, in his journal article on the election, stated that the smear came too late to be effectively rebutted, and likely cost Polk Ohio. Southern newspapers, on the other hand, went far in defending Polk, one Nashville newspaper alleging that his slaves preferred their bondage to freedom.[108] Polk himself implied to newspaper correspondents that the only slaves he owned had either been inherited or had been purchased from relatives in financial distress; this paternalistic image was also painted by surrogates like Gideon Pillow. This was not true, though not known at the time; by then he had bought over thirty slaves, both from relatives and others, mainly for the purpose of procuring labor for his Mississippi cotton plantation.[109]

There was no uniform election day in 1844; states voted between November 1 and 12.[110] Polk won the election with 49.5% of the popular vote and 170 of the 275 electoral votes.[111] Becoming the first president elected despite losing his state of residence (Tennessee),[110] Polk also lost his birth state, North Carolina. However, he won Pennsylvania and New York, where Clay lost votes to the antislavery Liberty Party candidate James G. Birney, who got more votes in New York than Polk's margin of victory. Had Clay won New York, he would have been elected president.[111]

الرئاسة (1845–1849)

With a slender victory in the popular vote, but with a greater victory in the Electoral College (170–105), Polk proceeded to implement his campaign promises. He presided over a country whose population had doubled every twenty years since the American Revolution and which had reached demographic parity with Great Britain.[112] During Polk's tenure, technological advancements persisted, including the continued expansion of railroads and increased use of the telegraph.[112] These improvements in communication encouraged a zest for expansionism.[113] However, sectional divisions became worse during his tenure.

Polk set four clearly defined goals for his administration:[113]

- Reestablish the Independent Treasury System – the Whigs had abolished the one created under Van Buren.

- Reduce tariffs.

- Acquire some or all of the Oregon Country.

- Acquire California and its harbors from Mexico.

While his domestic aims represented continuity with past Democratic policies, successful completion of Polk's foreign policy goals would represent the first major American territorial gains since the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.[113]

الانتقال والتنصيب والتعيينات

Polk formed a geographically balanced Cabinet.[114] He consulted Jackson and one or two other close allies, and decided that the large states of New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia should have representation in the six-member Cabinet, as should his home state of Tennessee. At a time when an incoming president might retain some or all of his predecessor's department heads, Polk wanted an entirely fresh Cabinet, but this proved delicate. Tyler's final Secretary of State was Calhoun, leader of a considerable faction of the Democratic Party, but, when approached by emissaries, he did not take offense and was willing to step down.[115]

Polk did not want his Cabinet to contain presidential hopefuls, though he chose to nominate James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, whose ambition for the presidency was well-known, as Secretary of State.[116] Tennessee's Cave Johnson, a close friend and ally of Polk, was nominated for the position of Postmaster General, with George Bancroft, the historian who had played a crucial role in Polk's nomination, as Navy Secretary. Polk's choices met with the approval of Andrew Jackson, with whom Polk met for the last time in January 1845, as Jackson died that June.[117]

Tyler's last Navy Secretary, John Y. Mason of Virginia, Polk's friend since college days and a longtime political ally, was not on the original list. As Cabinet choices were affected by factional politics and President Tyler's drive to resolve the Texas issue before leaving office, Polk at the last minute chose Mason as Attorney General.[115] Polk also chose Mississippi Senator Walker as Secretary of the Treasury and New York's William Marcy as Secretary of War. The members worked well together, and few replacements were necessary. One reshuffle was required in 1846 when Bancroft, who wanted a diplomatic posting, became U.S. minister to Britain.[118]

In his last days in office, President Tyler sought to complete the annexation of Texas. After the Senate had defeated an earlier treaty that required a two-thirds majority, Tyler urged Congress to pass a joint resolution, relying on its constitutional power to admit states.[119] There were disagreements about the terms under which Texas would be admitted and Polk became involved in negotiations to break the impasse. With Polk's help, the annexation resolution narrowly cleared the Senate.[119] Tyler was unsure whether to sign the resolution or leave it for Polk and sent Calhoun to consult with Polk, who declined to give any advice. On his final evening in office, March 3, 1845, Tyler offered annexation to Texas according to the terms of the resolution.[120]

Even before his inauguration, Polk wrote to Cave Johnson, "I intend to be myself President of the U.S."[121] He would gain a reputation as a hard worker, spending ten to twelve hours at his desk, and rarely leaving Washington. Polk wrote, "No President who performs his duty faithfully and conscientiously can have any leisure. I prefer to supervise the whole operations of the government myself rather than intrust the public business to subordinates, and this makes my duties very great."[3] When he took office on March 4, 1845, Polk, at 49, became the youngest president to that point. Polk's inauguration was the first inaugural ceremony to be reported by telegraph, and first to be shown in a newspaper illustration (in The Illustrated London News).[122]

In his inaugural address, delivered in a steady rain, Polk made clear his support for Texas annexation by referring to the 28 states of the U.S., thus including Texas. He proclaimed his fidelity to Jackson's principles by quoting his famous toast, "Every lover of his country must shudder at the thought of the possibility of its dissolution and will be ready to adopt the patriotic sentiment, 'Our Federal Union—it must be preserved.'"[123] He stated his opposition to a national bank, and repeated that the tariff could include incidental protection. Although he did not mention slavery specifically, he alluded to it, decrying those who would tear down an institution protected by the Constitution.[124]

Polk devoted the second half of his speech to foreign affairs, and specifically to expansion. He applauded the annexation of Texas, warning that Texas was no affair of any other nation, and certainly none of Mexico's. He spoke of the Oregon Country, and of the many who were migrating, pledging to safeguard America's rights there and to protect the settlers.[125]

As well as appointing Cabinet officers to advise him, Polk made his sister's son, J. Knox Walker, his personal secretary, an especially important position because, other than his slaves, Polk had no staff at the White House. Walker, who lived at the White House with his growing family (two children were born to him while living there), performed his duties competently through his uncle's presidency. Other Polk relatives visited at the White House, some for extended periods.[126]

السياسة الخارجية

Polk was committed to expansion: Democrats believed that opening up more land for yeoman farmers was critical for the success of republican virtue. (See Manifest Destiny.) Like most Southerners, he supported the annexation of Texas. To balance the interests of North and South, he wanted to acquire the Oregon Country (present-day Oregon, Washington, آيداهو, and British Columbia) as well. He sought to purchase California, which Mexico had neglected.

تكساس

President Tyler interpreted Polk's victory as a mandate for the annexation of Texas. Acting quickly because he feared British designs on Texas, Tyler urged Congress to pass a joint resolution admitting Texas to the Union; Congress complied on February 28, 1845. Texas promptly accepted the offer and officially became a state on December 29, 1845. The annexation angered Mexico, which had lost Texas in 1836. Mexican politicians had repeatedly warned that annexation would lead to war.

منطقة اوريگون

مقالة مفصلة: خلاف حدود اوريگون

مقالة مفصلة: خلاف حدود اوريگون

الحرب مع المكسيك

مقالة مفصلة: الحرب المكسيكية-الأمريكية

مقالة مفصلة: الحرب المكسيكية-الأمريكية

توترت العلاقات بين الولايات المتحدة والمكسيك بعد استقلال تكساس ، أما نيومكسكو وكاليفورنيا فقد ضمنتها الولايات المتحدة ، بعد الحرب مع المكسيك .

أسباب الحرب

ضعف الحكومة المكسيكية ، وعدم قدرتها على القيام بمسئولياتها بسبب الثورات المختلفة التي حصلت فيها ؛ كما اعتبرت المكسيك أن ضم تكساس يعتبر عملا عدوانيا . وقد حذرت أمريكا بذلك . وبعد الانضمام كانت مشكلة الحدود بين المكسيك وتكساس هي السبب المباشر للحرب ، فبينما اعتبرت أمريكا أن الحدود تقع عند نهر ريوجراند رأت المكسيك أن هذه الحدود تقع عند نهر نورس إلى الشمال وهي منطقة حدود تكساس قبل الإستقلال عن المكسيك ؛ كما أن تدخل أمريكا في شئون كاليفورنيا أزعج المكسيك . ففي عام 1842 ، كان الكومودور جونز في البحرية الأمريكية قد سمع إشاعة وجود حرب مع المكسيك ، ولذلك قام باحتلال مونتري ، وبعد أن أقنعه لاركن بالخطأ ، اعتذر وانسحب ، ولكن هذا الأمر أعطى المكسيك فكرة عن نوايا امريكا ، ولذلك قامت المسكيك في عام 1843 بإبعاد الأمريكيين من كاليفورنيا ، ومنعت الهجرة الأمريكية إلى هناك ، قام الأمريكيون بطلب الحماية من الحكومة الأمريكية .

بعثة سلايدل

قام بولك بابتعاث جون سلايدل إلى عاصمة المكسيك في نوفمبر عام 1845 ، وطلب منه اقتراح التسوية الآتية : أن أمريكا ستدفع ادعاءات مواطنيها ضد المكسيك مقابل اعتبار ريوجراند هي الحد الجنوبي مع المكسيك ، الاقتراح يدفع مبلغ خمسة ملايين دولار ثمنا لنيومكسيكو وعشرين مليونا ثمنا لكاليفورنيا ، ولم يجرؤ رؤساء المكسيك على استقبال سلايدل خوفامن الرأي العام المكسيكي ، وهكذا فشلت المحاولة في المفاوضات .

السبب المباشر

رفض المكسيك للمفاوضات ؛ جعل بولك يأمر القوات الأمريكية بالعبور إلى المنطقة الجنوبية – ريو جراندي – وتوقع أن يهاجمها المكسيكيون ؛ وبالفعل قامت المكسيك بالهجوم على القوات الأمريكية في إبريل عام 1846. وهنا وافق الكونجرس على طلب بولك بإعلان الحرب في 12 مايو عام 1846، وكان الشمال الشرقي معارضا للحرب، لأنه اعتبرها إضافة لمناطق يوجد فيها نظام الرق، وقد اعتمدت هذه الحرب على متطوعين من المناطق الجنوبية الغربية.

حملات الحرب المكسيكية

كانت هناك ثلاث حملات ، أمريكية في هذه الحرب : هجوم الجنرال تيلر على شمال المكسيك ، احتلال الجنرال كيرني لنيومكسيكو وكاليفورنيا ، ثم حملة الجنرال سكوت على عاصمة المكسيك .

أولا : حملة زكري تيلر : قطع الحدود عند ماتا موراس في مايو عام 1846 ، واتجه نحو الجنوب الغربي حيث احتل مونتري في سبتمبر ، وفي فبراير عام 1847 انتصر علىسانتا آنا في معركة يونا فيستا ؛ كان يريد التقدم إلى مدينة المكسيك ، ولكن بولك لم يرد أن يعطي فرصة لواحد من أتباع الوجز بكسب الشعبية ، ولذلك أمره باحتلال شمال المكسيك فقط .

ثانيا : كيرني في نيومكسيكو وكاليفورنيا : كان على رأس ههذ الحملة ؛ حيث بدأ زحفه في يونيو عام 1846 ، وكانت قد بدأت قبل ذلك ثورة من المستوطنين ضد المكسيك بقيادة وليام آيد يساعده أيضا الكثير جون سي فريمونت ، وعندما سمع هؤلاء بالحرب زحفوا إلى جنوب كاليفورنيا ، وبمساعدة الأسطول البحري احتلوا سان فرانسسكو ومونتري ، ولوس أنجلوس ،وعند وصول كيرني ، استلم قيادةالقوات جميعها عند سان ديجو ، وكمل احتلاله عند لوس أنجلوس .

ثالثا : سكوت إلى عاصمة المكسيك في أواخر 1846 : أمر سكوت بإنزال قواته في فيراكروز بغرض الزحف إلى عاصمةالمكسيك ، وقد استطاع هذاالتغلب على المكسيكيين في عدة معارك ، وأخيرا دخل العاصمة بعد انتصاره على سانتا آنا في سبتمبر عام 1847 . وكان يصاحبه سكوت نكول لاس ترست رئيس الكتبة في وزارة الخارجية بتعلميات بخصوص عقد معاهدة ، حيث كان يعرف الإسبانية . ولكن الحكومة دعته إلى واشنطن بغرض التعديل في الاتاقية الأصلية – وربما الطمع بضم كل المكسيك – غير أن ترست بعد رجوعه إلى المكسيك كتب بنود المعاهدة كما هي في اتفاقه الأصلي مع بولك – حسب التعليمات الأولى – وهكذا وقعها بولك مرغما كأمر واقع . وقد عارض أصحاب مناهضة نظام الرق هذه المعاهدة لأنها تزيد منالولايات الجنوبية .

معاهدة گوادالوپه هدالگو 1848

من شروطها أن تتخلى المكسيك عن نيومكسيكو وكاليفورنيا ، واعتبار نهر ريوجراند الحد الجنوبي لأمريكا ، وأن تدفع الولايات المتحدة مبلغ خمسة عشر مليون دولار ثمنا لنيومكسيكو وكاليفورنيا ، وتتحمل دعاوي المواطنين الأمريكيين ضد حكومة المكسيك .

كوبا

تشريعات إدارة بولك

التوسع الإقليمي كان من أهم إنجازات هذه الإدارة ، من بعض التشريعات في عهد بولك ما يلي : سن قانون تعريفة ووكر عام 1846 ، وبموجبه فقد خفضت التعريفة الجمركية عما كانت عليه في قانون عام 1842 . وكان ممثلو الغرب والجنوب هم الذين عملوا على إصدار هذا القانون في الكونجرس . من حيث إيداعات الحكومة الفدرالية ، فقد أعيد تكوين نظام الخزانة المساعدة عام 1846 – بمعنى إيداع مدخرات الحكومة الفدرالية في بعض البنوك التي تختاره هذه الحكومة في الولايات – وظل هذا النظام متبعا حتى عام 1920 .

انتخابات الرئاسة لعام 1848

مع أن نشوب الحرب مع المكسيك قد أدى إلى النقاش في الكونجرس حول مسألة الرق ؛ إلا ان كلا الحزبين لم يجعل من هذ المسألة نقطة نقاش في الحملة الانتخابية . لقد رشح الحزب الديمقراطي لويس كاس من ولاية ميتشجان ، اما حزب الوجز فقد رشح بطل الحرب المكسيكية الجنرال زاكري تيلر ، مالك الرقيق من ولاية لويزيانا ، وقد رشح ميلارد فيلمور من ولاية نيويورك نائبا للرئيس . كما ظهر حزب ثالث من الفئات التي تجمعت من أحزاب أخرى ، واتفقت على فكرة معارضة نظام الرق . وقد شمل هذا الحزب بعض اتباع حزب الحرية وبعض أتباع حزب الوجز منالمعارضين لنظام الرق ، ثم بعض الديمقراطيين المعارض للرق أيضا ، ولقد تسمى هذا الحزب بحزب (الأرض الحرة) . مرشحا مارتن فان بيورن ، الرئيس الأسبق . وبسبب انقسام الديمقراطيين على أنفسهم في ولاية نيويورك ، فقد أدى هذا إلى نجاح تيلر في هذه الولاية ؛ وبذلك كسب في الإنتخابات .

وهكذا ، فمع نهاية إدارة الرئيس بولك ، وكنتيجة مباشرة للحرب مع المكسيك ، أصبح مساحة أراضي الولايات المتحدة تقدر بحوالي ثمانية ملايين من الكيلومترات المربعة ، مع شواطئ واسعة على المحيط الهادي . وقد فتح – هذا – آفاقا واسعة أمام الولايات المتحدة ؛ خاصة أنه بعد أسابيع قليلة ، اكتشف الذهب في ولاية كاليفورنيا ، وبدأ سيل من الهجرة المحمومة نحو الساحل الغربي للولايات المتحدة .

بعد الرئاسة

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ "Polk". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Borneman, pp. 4–6

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز Rawley, James A. (February 2000). "Polk, James K.". American National Biography Online. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0400795.

- ^ Haynes, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Borneman, pp. 6–7

- ^ Seigenthaler, p. 11

- ^ Borneman, p. 8

- ^ Borneman, p. 13

- ^ Leonard, p. 6

- ^ The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 1875.

- ^ Haynes, p. 11

- ^ أ ب Borneman, pp. 8–9

- ^ Seigenthaler, p. 22

- ^ Borneman, p. 10

- ^ أ ب Borneman, p. 11

- ^ Seigenthaler, p. 24

- ^ Leonard, p. 5

- ^ أ ب ت ث Borneman, p. 14

- ^ أ ب Seigenthaler, p. 25

- ^ United States Department of the Army (1980). Soldiers. p. 4.

- ^ "Daguerreotype of President and Mrs. Polk". WHHA (en-US) (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Seigenthaler, p. 26

- ^ "Sarah Childress Polk". White House Historical Association. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ Borneman, p. 16

- ^ Borneman, pp. 16–18

- ^ Greenberg, p. 25

- ^ Borneman, p. 23

- ^ Borneman, pp. 23–24

- ^ Borneman, p. 24

- ^ Seigenthaler, pp. 38–39

- ^ أ ب Borneman, p. 26

- ^ Merry, pp. 30, 39–40

- ^ Seigenthaler, pp. 45–47

- ^ Seigenthaler, p. 46

- ^ Merry, pp. 42–43

- ^ Borneman, pp. 28–29

- ^ Seigenthaler, pp. 48–52

- ^ Seigenthaler, pp. 47–48

- ^ Borneman, p. 33

- ^ Merry, p. 42

- ^ Borneman, p. 34

- ^ Seigenthaler, pp. 53–54

- ^ Borneman, p. 35

- ^ أ ب Leonard, p. 23

- ^ Seigenthaler, pp. 55–56

- ^ "Democrats vs. Whigs". Tennessee State Museum. Archived from the original on April 12, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ^ أ ب Seigenthaler, pp. 57–61

- ^ Remini, p. 406

- ^ Bergeron, p. 1

- ^ Bergeron, p. 12

- ^ Seigenthaler, p. 62

- ^ Borneman, p. 38

- ^ Merry, pp. 45–46

- ^ Seigenthaler, p. 64

- ^ Bergeron, p. 13

- ^ Borneman, pp. 41–42

- ^ Borneman, p. 43

- ^ أ ب Leonard, p. 32

- ^ أ ب Borneman, pp. 46–47

- ^ "1840 Presidential Election". 270toWin. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ "Richard Mentor Johnson, 9th Vice President (1837–1841)". U.S. Senate. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

One of the 23 Virginia electors, and all of South Carolina's 11 electors, voted for Van Buren but defected to James K. Polk and Littleton W. Tazewell of Virginia, respectively, in the vice-presidential contest.

- ^ "1840 Presidential General Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ أ ب Seigenthaler, p. 66

- ^ Merry, p. 47

- ^ Bergeron, p. 14

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 18–19

- ^ Borneman, p. 64

- ^ Seigenthaler, p. 68

- ^ Merry, pp. 47–49

- ^ Merry, pp. 43–44

- ^ أ ب ت Merry, pp. 50–53

- ^ Borneman, p. 51

- ^ Borneman, pp. 65–66

- ^ Borneman, pp. 67–74

- ^ Leonard, pp. 67–68

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 51–53

- ^ Leonard, p. 36

- ^ Borneman, pp. 81–82, 122

- ^ Bergeron, p. 15

- ^ Borneman, p. 83

- ^ أ ب Leonard, pp. 36–37

- ^ Remini, p. 501

- ^ Merry, p. 80

- ^ Merry, pp. 83–84

- ^ Borneman, pp. 86–87

- ^ Merry, pp. 84–85

- ^ أ ب Merry, pp. 87–88

- ^ Merry, p. 89

- ^ Bergeron, p. 16

- ^ Borneman, pp. 102–106

- ^ Borneman, pp. 104–108

- ^ Merry, pp. 94–95

- ^ Borneman, p. 108

- ^ أ ب Merry, pp. 96–97

- ^ Borneman, pp. 355–356

- ^ Borneman, pp. 111–114

- ^ Eisenhower, p. 81

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 17–19

- ^ Seigenthaler, pp. 90–91

- ^ Merry, pp. 97–99

- ^ Merry, p. 99

- ^ Borneman, pp. 117–120

- ^ Merry, pp. 100–103

- ^ Merry, pp. 104–107

- ^ Borneman, pp. 122–123

- ^ أ ب Merry, pp. 107–108

- ^ Borneman, pp. 121–122

- ^ Eisenhower, p. 84

- ^ Dusinberre, pp. 12–13

- ^ أ ب Borneman, p. 125

- ^ أ ب Merry, pp. 109–111

- ^ أ ب Merry, pp. 132–133

- ^ أ ب ت Merry, pp. 131–132

- ^ Merry, pp. 112–113

- ^ أ ب Bergeron, pp. 23–25

- ^ Merry, pp. 114–117

- ^ Merry, pp. 117–119

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 29–30

- ^ أ ب Merry, pp. 120–124

- ^ Woodworth, p. 140

- ^ Greenberg, p. 69

- ^ "President James Knox Polk, 1845". Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- ^ Borneman, p. 141

- ^ Borneman, pp. 141–142

- ^ Borneman, pp. 142–143

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 230–232

- ^ Greenberg, p. 70

- ^ "James Polk's cabinet". WHHA (en-US) (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved February 4, 2022.

نصوص مستخدمة

- Borneman, Walter R. (2008). Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America. New York: Random House, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4000-6560-8.

- Bergeron, Paul H. The Presidency of James K. Polk. 1986. ISBN 0-7006-0319-0.

- De Voto, Bernard The Year of Decision: 1846 Houghton Mifflin, 1943.

- Dusinberre, William. Slavemaster President: The Double Career of James Polk. 2003. ISBN 0-19-515735-4. Questia edition (subscription)

- Dusinberre, William. "President Polk and the Politics of Slavery." American Nineteenth Century History 3.1 (2002): 1-16. ISSN 1466-4658. Argues Polk misrepresented the strength of abolitionism, grossly exaggerated the likelihood of slaves' massacring white families, and seemed to condone secession.

- Eisenhower, John S. D. "The Election of James K. Polk, 1844." Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 53.2 (1994): 74-87. ISSN 0040-3261.

- Haynes, Sam W. James K. Polk and the Expansionist Impulse. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-673-99001-3.

{{cite book}}: Text "year-1997" ignored (help) - Kornblith, Gary J. "Rethinking the Coming of the Civil War: a Counterfactual Exercise." Journal of American History 90.1 (2003): 76-105. ISSN 0021-8723. Asks what if Polk had not gone to war?

- Leonard, Thomas M. James K. Polk: A Clear and Unquestionable Destiny. 2000. ISBN 0-8420-2647-9.

- McCormac, Eugene Irving. James K. Polk: A Political Biography to the End of a Career, 1845-1849. Univ. of California Press, 1922. (1995 reprint has ISBN 0-945707-10-X.) Extreme anti-Jacksonian views.

- McCoy, Charles A. Polk and the Presidency. 1960.

- Morrison, Michael A. "Martin Van Buren, the Democracy, and the Partisan Politics of Texas Annexation." Journal of Southern History 61.4 (1995): 695-724. ISSN 0022-4642. Discusses the election of 1844. online edition

- Paul; James C. N. Rift in the Democracy. 1951. on 1844 election

- Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr. Age of Jackson Little Brown, 1945. Pp. 439ff on Polk

- Schouler, James. Democrats and Whigs, 1831-1847. Vol. 4 of History of the United States of America: Under the Constitution. 1917.

- Sellers, Charles. James K. Polk, Jacksonian, 1795-1843. 1957.

- Sellers, Charles. James K. Polk, Continentalist, 1843-1846. 1966.

- Seigenthaler, John. James K. Polk: 1845–1849. 2003. ISBN 0-8050-6942-9.

- Smith, Justin H. The War with Mexico, Macmillan, 1919. Still the standard source, used, for example, Dusinberre.

المصادر الرئيسية

- Cutler, Wayne, et al. Correspondence of James K. Polk. 1972-2004. ISBN 1-57233-304-9. 10 vol. scholarly edition of the complete correspondence to and from Polk.

- Polk, James K. The Diary of James K. Polk During His Presidency, 1845-1849 edited by Milo Milton Quaife, 4 vols. 1910. Abridged version by Allan Nevins. 1929, online

وصلات خارجية

- Extensive essay on James K. Polk and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Inaugural Address of James K. Polk.

- Biography of James K. Polk. The White House (Official Site).

- First State of the Union Address (1845).

- Second State of the Union Address (1846).

- Third State of the Union Address (1847).

- Fourth State of the Union Address (1848).

- POTUS - James Knox Polk

- أعمال من James K. Polk في مشروع گوتنبرگ

- Obituary of President Polk in The Liberator (June 22, 1849)

- Smithsonian's "Establishing Borders: The Expansion of the United States, 1846-48" with essay and lesson plans

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Pages using infobox officeholder with unknown parameters

- CS1 errors: unrecognized parameter

- جيمس پولك

- مواليد 1795

- وفيات 1849

- رؤساء الولايات المتحدة

- مرشحون رئاسيون للحزب الديمقراطي الأمريكي

- مرشحو الرئاسة الأمريكية 1844

- رؤساء مجلس النواب الأمريكي

- تاريخ الولايات المتحدة (1789–1849)

- مشيخيون أمريكان

- 19th-century American people

- 19th-century American politicians

- 19th-century Methodists

- 19th-century Presbyterians

- 19th-century presidents of the United States

- American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law

- Methodists from Tennessee

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American Presbyterians

- American slave owners

- Burials in Tennessee

- Converts to Methodism

- Deaths from cholera

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Tennessee

- Democratic Party presidents of the United States

- Democratic Party state governors of the United States

- Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees

- American Freemasons

- Governors of Tennessee

- 1840s in the United States

- Infectious disease deaths in Tennessee

- Jacksonian members of the United States House of Representatives from Tennessee

- People from Mecklenburg County, North Carolina

- Polk family

- Presidency of James K. Polk

- Presidents of the United States

- Second Party System

- Speakers of the United States House of Representatives

- Tennessee lawyers

- Candidates in the 1844 United States presidential election

- 1840 United States vice-presidential candidates

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill alumni

- 19th-century diarists

- American nationalists