أرخميدس

أرخميدس من سرقوسة | |

|---|---|

Ἀρχιμήδης | |

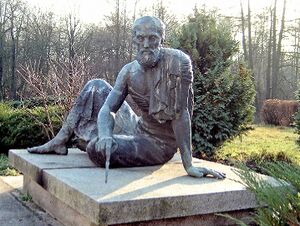

أرخميدس المفكر بريشة فتي (1620) | |

| وُلِدَ | ح. 287 ق.م. |

| توفي | ح. 212 ق.م. (عمره حوالي 75) سرقوسة |

| عـُرِف بـ | |

| السيرة العلمية | |

| المجالات | الرياضيات الفيزياء الهندسة علم الفلك الاختراع |

أرخميدس من سرقوسة ( /ˌɑːkɪˈmiːdiːz/;[2] باليونانية: Ἀρχιμήδης أو أرشميدس؛ ح. 287 ق.م. – ح. 212 ق.م.)، هو رياضيات، فيزيائي، مهندس، مخترع، وفلكي يوناني قديم.[3] بالرغم من معرفة القليل من تفاصيل حياته، إلا أنه يعتبر واحداً من أبرز العلماء في العصر العتيق الكلاسيكي.

يعتبر بصفة عامة من أعظم الرياضياتيين في العصر العتيق وواحداً من أعظم الرياضياتيين في جميع العصور،[4][5] كان أرخميدس من رواد حساب التفاضل والتكامل والتحليل الحديث بتطبيق مفاهيم متناهيات الصغر وطريقة الاستنفاد لاشتقاق والاثبات القاطع لنطاق النظريات الهندسية، وتشمل مساحة الدائرة، مساحة السطح وحجم الكرة، المساحة أسفل القطع المكافئ.[6]

يعود له الفضل في تصميم الآلات المبتكرة، بما في ذلك محركات الحصار ومضخة المسمار التي تحمل اسمه.

خلافا لإختراعاته، كانت كتابات أرخميدس الرياضية معروفة قليلا في العصور القديمة، وقد نقلها عنه علماء الرياضيات من الإسكندرية، ولكن أول تجميع شامل لنظريات أرخميدس تم تقديمه سنة 530 م. لإيزيدور ميليتس، بينما التعليقات على أعمال أرخميدس كتبها يوتوسيوس في القرن السادس الميلادي فتحت المجال الأوسع للقراء و التعرف عليها لأول مرة.

وقد كانت النسخ القليلة نسبيا من أعمال أرخميدس المكتوبة التي نجت خلال العصور الوسطى مصدرا مؤثرا في أفكار العلماء في عصر النهضة[7]، بينما في عام 1906 قدمت إكتشافات جديدة من أعمال أرخميدس لم تكن معروفة سابقا ، وقد قدم فيها أرخميدس رؤى جديدة في طرق و كيفية حصوله على النتائج الرياضية[8].

توفي أرخميدس حوالي سنة 212 ق.م. أثناء الحرب البونيقية الثانية، عندما استولت القوات الرومانية تحت قيادة الجنرال ماركوس كلاوديوس مرسلوس بالإستيلاء على مدينة سيراقوسة بعد حصار دام سنتين. وحسب قصة شهيرة يرويها پلوتارخ، فإن أرخميدس كان يقوم بحل مشكلة رياضية هندسية عندما تم الاستيلاء على المدينة. أتاه جندي روماني يأمره بلقاء جنرال مرسلوس إلا أن أرخميدس رفض، قائلاً أن عليه أن ينتهي من المسألة الرياضية أولاً. الجندي غضب من ذلك وقتله بالسيف. پلوتارخ يعطي كذلك رواية أخرى أقل شهرة عن مقتل أرخميدس، وتقول تلك الرواية أن أرخميدس قد يكون قد قـُتل بينما كان يحاول الاستسلام للجندي الروماني. وحسب تلك الرواية، فأرخميدس كان يحمل أدواتاً هندسية, وقتله الجندي ظناً منه أنه يحاول الفرار بأشياء ثمينة. ويروى أن الجنرال مرسلوس غضب لمصرع أرخميدس، إذ أنه قد أمر مسبقاً ألا يؤذى.[9]

آخر كلمات تُنسب لأرخميدس "لا تفسدوا دوائري" (باليونانية: μή μου τούς κύκλους τάραττε)، في إشارة إلى الدوائر التي كان يرسمها أثناء حله لمشكلة رياضية حين دخل عليه جنود غزاة رومان. هذا القول صار مأثوراً باللاتينية: "Noli turbare circulos meos"، إلا أنه ليس هنالك من دليل على أن أرخميدس قال تلك الكلمات ولا هي تظهر في الرواية التي نقلها پلوتارخ.[9]

سيرته

وُلد أرخميدس سنة 287 قبل الميلاد في سرقوسة الواقعة بجزيرة صقلية، في ذلك الوقت كانت مستعمرة متمتعة بالحكم ذاتي في اليونان العظمى، وكان والده فلكياً شهيراً، وقد كتب پلوتارخ في كتابه حياة موازية أن أرخميدس كان مرتبطاً إلى الملك هيرون الثاني، حاكم سرقوسة [10]، وصنع له سفينة سيراكوزيا الضخمة، سيرة أرخميدس كتبها صديق له يدعى هيراكليديس ولكن هذا العمل قد فقد، وترك تفاصيل حياته غامضة وغير معروفة [11]، فعلى سبيل المثال، لم تذكر المراجع التاريخية،إن كان أرخميدس قد تزوج في فترة شبابه أو رزق بأطفال.

كمعظم الشباب آنذاك سافر أرخميدس إلى الإسكندرية والتقى بقونون ساموس وإراتوستينس القيرواني وهما من علماء الرياضيات في عصره، وتشير اثنين من أعمال أرخميدس (الأسلوب النظريات الميكانيكية إنگليزية: The Method of Mechanical Theorems ومشكلة ماشية إنگليزية: Cattle Problem) لديهم مقدمات موجهة إلى إراتوستينس[a]، بعدها سافر إلى اليونان طلباً للدراسة، ويعد الكثير من مؤرخي الرياضيات والعلوم أن أرخميدس من أعظم علماء الرياضيات في العصور القديمة، وهو أبو الهندسة.

وفاته

في عام 212 ق.م. وكان أرخميدس عاكفاً على حل مسألة رياضية بمنزله لا يدري شيئا عن احتلال المدينة من قبل الرومان! وبينما كان يرسم مسألته على الرمال، دخل عليه جندي روماني وأمره أن يتبعه لمقابلة "مارسيلوس"، فرد عليه "أرخميدس": من فضلك، لا تفسد دوائري! (Noli,turbare circulos meos) وطلب منه أن يمهله حتى ينتهي من عمله، فاستشاط الجندي غضبا وسل سيفه ليطعن أرخميدس دون تردد. وسقط "أرخميدس" على الفور غارقا في دمائه، ولفظ أنفاسه الأخيرة.

الاكتشافات والاختراعات

قضى أرخميدس حياته في الدراسات الفلسفية والرياضية، واكتسب شعبية واسعة في عصره بسبب اختراعاته واكتشافاته، فقد ابتكر طريقة لرفع الماء بآلة تدعى «لولب أرخميدس» وهي لا تزال قيد الاستعمال لري الحقول. وتتكون هذه الآلة الرافعة من لولب حلزوني واسع مركَّب بإحكام في داخل صندوق أسطواني تغمر نهايته السفلى في الماء وتجعل نهايته العليا حيث يُراد تجميع الماء كحوض أو مجرى. فحين يدور اللولبُ يدفع الماء معه إلى الحوض، وقد وضع أرخميدس كذلك القوانين الرياضية للرافعة، وبرهن على صحتها، وأصبح بوسع الإنسان مضاعفة القوة المتاحة له لتحريك الأثقال الكبيرة.[12]

ومن أشهر اكتشافاته، طرق حساب المساحات والأحجام والمساحات الجانبية للأجسام، وأثبت القدرة على حساب تقريبي دقيق للجذور التربيعية واخترع طريقة لكتابة الأرقام الكبيرة. وهو نفسه الذي حدد قيمة π (باي) (Pi ) وهي العلاقة بين محيط الدائرة وقطرها بدقة عالية. أما في مجال الميكانيكا فأرخميدس هو مكتشف النظريات الأساسية لمركز الثقل للأسطح المستوية والأجسام الصلبة واستخدام الروافع ومخترع قلاووظ أرخميدس.

ومن أبرز القوانين التي اكتشفها قانون طفو الأجسام داخل المياه والذي صار يعرف بقانون أرشميدس. وقال عنه العالم الرياضياتي جاوس أنه واحد من أعظم ثلاثة في العلوم الرياضية مع كل من اسحاق نيوتن وفردناند إيسنستن.

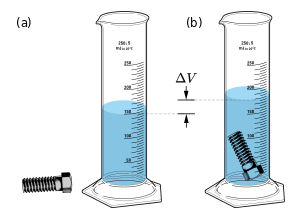

اكتشف قانون الوزن النوعي، حين طلب منه هيرون ملك سيراقوسة أن يتاكد من نوعية ذهب تاجه بدون أن ينزع من التاج شيئا. اكتشف أثناء جلوسه في حوض الحمام أن كل جسم يغمس في الماء يفقد من وزنه بقدر ثقل الماء الذي يزيحه حجمه. خرج من الحمام عريان وهو يصيح "اوريكا، اوريكا" أي "وجدتها، وجدتها".

قاعدة أرخميدس

شك ملك سرقوسة في أن الصائغ الذي صنع له التاج قد غشه، حيث أدخل في التاج نحاس بدلاً من الذهب الخالص، وطلب من أرخميدس أن يبحث له في هذا الموضوع بدون إتلاف التاج. وعندما كان يغتسل في حمام عام، لاحظ أن منسوب الماء ارتفع عندما انغمس في الماء وأن للماء دفع على جسمه من أسفل إلى أعلى، فخرج في الشارع يجري ويصيح (أوريكا، أوريكا)؛ أي وجدتها وجدتها، لأنه تحقق من أن هذا الاكتشاف سيحل معضلة التاج. وقد تحقق أرشميدس من أن جسده أصبح أخف وزناً عندما نزل في الماء، وأن الانخفاض في وزنه يساوي وزن الماء المزاح الذي أزاحه، وتحقق أيضا من أن حجم الماء المزاح يساوي حجم الجسم المغمور. وعندئذ تيقن من إمكانية أن يعرف مكونات التاج دون أن يتلفه؛ وذلك بغمره في الماء، فحجم الماء المزاح بغمر التاج فيه لا بد أن يساوي نفس حجم الماء المزاح بغمر وزن ذهب خالص مساو ٍ لوزن التاج. وكانت النتيجة: أن الصائغ فقد رأسه بهذه النظرية. ووضع ارشميدس قاعدته الشهيرة المسماة قاعدة أرخميدس والتي بني عليها قاعدة الطفو فيما بعد.

قانون الروافع

While Archimedes did not invent the lever, he gave a mathematical proof of the principle involved in his work On the Equilibrium of Planes.[13] Earlier descriptions of the principle of the lever are found in a work by Euclid and in the Mechanical Problems, belonging to the Peripatetic school of the followers of Aristotle, the authorship of which has been attributed by some to Archytas.[14][15]

There are several, often conflicting, reports regarding Archimedes' feats using the lever to lift very heavy objects. Plutarch describes how Archimedes designed block-and-tackle pulley systems, allowing sailors to use the principle of leverage to lift objects that would otherwise have been too heavy to move.[16] According to Pappus of Alexandria, Archimedes' work on levers and his understanding of mechanical advantage caused him to remark: "Give me a place to stand on, and I will move the Earth" (Greek: δῶς μοι πᾶ στῶ καὶ τὰν γᾶν κινάσω).[17] Olympiodorus later attributed the same boast to Archimedes' invention of the baroulkos, a kind of windlass, rather than the lever.[18]

لولب أرخميدس

ويعرف أيضاً بشادوف أرخميدس وهو عبارة عن أسطوانة داخلها حلزون يدور حول محوره، استخدمه القدماء لرفع المياه من الخزانات. وهو مكون من قضيب خشبي طوله حوالي متر محاط بحلزون من مواد مرنة مثبتة في ألواح خارجية، وقد علق فيتروفيوس في القرن الأول الميلادي على ذلك قائلا: إنه محاكاة طبيعية لقوقعة حلزونية. وفي عصر الرومان كانت حلزونة أرخميدس تعمل بالسير فوقه مثل آلة الغزل اليدوية اليوم، ولكن في القرن الخامس عشر، كان يعمل بمحور تدوير. في مايو 1839 حلت سفينة أرشميدس بدلاً عن البدال التقليدي الذي يدور بالبخار مستخدماً دافعاً يعمل بفكرة الحلزون. في البداية عارض الناس التصميم، وأحتاج إلى أربع سنوات ليثبت أنه أفضل من سابقه.

واستخدمه المصريون منذ 2000 عام وما زالوا إلى الآن يستخدمونه في الري ورفع المياه ويسمى الطنبور، ويبلغ قطره نحو 35 سنتيمتر وطوله نحو 5و2 متر. وقد صنعت حلزونة أرشميدس بمقاييس مختلفة تتراوح قطرها من ربع بوصة إلى 12 قدماً للاستخدامات المختلفة.

وكان أرخميدس شديد الولع بصناعة الآلات ودراستها، وكان هدفه الأول من هذه الدراسة هو معرفة القوانين الميكانيكية التي تتحكم في عمل الآلات. وبدأ اهتمامه الأول بدراسة الرافعة الأولية، وكانت نتيجة الدراسة هي : معرفة قوانين الروافع وتسجيلها، وتعتبر نظرياته عن الروافع من أهم نظريات الفيزياء النظرية. وقد اهتم أيضا ببعض الآلات الأخرى المعروفة في عصره مثل البكرة ومناول ترسي. واخترع العجلات المسننة، والكرة المتحركة، واكتشف نظرية العتلة، حيث قيل أنه كان يعتقد بأنه يمكن أن يرفع الأرض لو وجد مايركزها عليه. كما اخترع أحد الأجهزة التي تحاكي الحركات السماوية للشمس والقمر والكواكب.

كان ذو عقلية متعددة الاهتمامات. وكان ولعه بالرياضيات لايشغله عن الاهتمام بالميكانيكا والفيزياء النظرية والفلك. وبفضل هذه الاهتمامات المتعددة أصبح من أوائل الذين انتقلوا بالرياضيات من المجال النظري إلى المجال التطبيقي. وقد اخترع الكثير من الآلات المعروفة باسمه، ومنها بعض الأسلحة التي استخدمت في سيراقوسة عند هجوم الرومان عليها عام 212 ق.م. وأرخميدس هو أول من استخدم الأشعة الشمسية عند هجوم الرومان على مدينته.

مخلب أرخميدس

Archimedes is said to have designed a claw as a weapon to defend the city of Syracuse. Also known as "the ship shaker", the claw consisted of a crane-like arm from which a large metal grappling hook was suspended. When the claw was dropped onto an attacking ship the arm would swing upwards, lifting the ship out of the water and possibly sinking it.[19] There have been modern experiments to test the feasibility of the claw, and in 2005 a television documentary entitled Superweapons of the Ancient World built a version of the claw and concluded that it was a workable device.[20]

Archimedes has also been credited with improving the power and accuracy of the catapult, and with inventing the odometer during the First Punic War. The odometer was described as a cart with a gear mechanism that dropped a ball into a container after each mile traveled.[21]

الأشعة الحرارية

As legend has it, Archimedes arranged mirrors as a parabolic reflector to burn ships attacking Syracuse using focused sunlight. While there is no extant contemporary evidence of this feat and modern scholars believe it did not happen, Archimedes may have written a work on mirrors entitled Catoptrica,[أ] and Lucian and Galen, writing in the second century AD, mentioned that during the siege of Syracuse Archimedes had burned enemy ships. Nearly four hundred years later, Anthemius, despite skepticism, tried to reconstruct Archimedes' hypothetical reflector geometry.[22]

The purported device, sometimes called "Archimedes' heat ray", has been the subject of an ongoing debate about its credibility since the Renaissance.[23] René Descartes rejected it as false, while modern researchers have attempted to recreate the effect using only the means that would have been available to Archimedes, mostly with negative results.[24][25] It has been suggested that a large array of highly polished bronze or copper shields acting as mirrors could have been employed to focus sunlight onto a ship, but the overall effect would have been blinding, dazzling, or distracting the crew of the ship rather than fire.[26] Using modern materials and larger scale, sunlight-concentrating solar furnaces can reach very high temperatures, and are sometimes used for generating electricity.[27]

أجهزة فلكية

Archimedes discusses astronomical measurements of the Earth, Sun, and Moon, as well as Aristarchus' heliocentric model of the universe, in the Sand-Reckoner. Without the use of either trigonometry or a table of chords, Archimedes determines the Sun's apparent diameter by first describing the procedure and instrument used to make observations (a straight rod with pegs or grooves),[28][29] applying correction factors to these measurements, and finally giving the result in the form of upper and lower bounds to account for observational error.[30] Ptolemy, quoting Hipparchus, also references Archimedes' solstice observations in the Almagest. This would make Archimedes the first known Greek to have recorded multiple solstice dates and times in successive years.[31]

Cicero's De re publica portrays a fictional conversation taking place in 129 BC. After the capture of Syracuse in the Second Punic War, Marcellus is said to have taken back to Rome two mechanisms which were constructed by Archimedes and which showed the motion of the Sun, Moon and five planets. Cicero also mentions similar mechanisms designed by Thales of Miletus and Eudoxus of Cnidus. The dialogue says that Marcellus kept one of the devices as his only personal loot from Syracuse, and donated the other to the Temple of Virtue in Rome. Marcellus's mechanism was demonstrated, according to Cicero, by Gaius Sulpicius Gallus to Lucius Furius Philus, who described it thus:[32][33]

Hanc sphaeram Gallus cum moveret, fiebat ut soli luna totidem conversionibus in aere illo quot diebus in ipso caelo succederet, ex quo et in caelo sphaera solis fieret eadem illa defectio, et incideret luna tum in eam metam quae esset umbra terrae, cum sol e regione.

When Gallus moved the globe, it happened that the Moon followed the Sun by as many turns on that bronze contrivance as in the sky itself, from which also in the sky the Sun's globe became to have that same eclipse, and the Moon came then to that position which was its shadow on the Earth when the Sun was in line.

This is a description of a small planetarium. Pappus of Alexandria reports on a now lost treatise by Archimedes dealing with the construction of these mechanisms entitled On Sphere-Making.[34][35] Modern research in this area has been focused on the Antikythera mechanism, another device built ح. 100 BC probably designed with a similar purpose.[36] Constructing mechanisms of this kind would have required a sophisticated knowledge of differential gearing.[37] This was once thought to have been beyond the range of the technology available in ancient times, but the discovery of the Antikythera mechanism in 1902 has confirmed that devices of this kind were known to the ancient Greeks.[38][39]

الرياضيات

في كتابه قياس دائرة، يعطي أرخميدس قيمة الجذر التربيعي للرقم 3 بأنه أكبر من 265/153 (تقريباً 1.732) وأقل من 1351/780 (تقريباً 1.7320512). القيمة الفعلية هي حوالي 1.7320508076، مما يجعل تقديره دقيقاً جداً. وقد قدم هذه النتيجة بدون إعطاء أي شرح للطريقة المستعملة للوصول إليها. هذا الجانب من عمل أرخميدس جعل جون واليس يعلق بأنه: "كما لو كان غرضه هو إخفاء أي آثار لتحقيقاته كما لو كان يبغض أن يصل سر طريقه تقصيه لمن يأتي بعده بينما يريد في الوقت نفسه إنتزاع موافقة اللاحقين على نتائجه."[40]

وفي The Quadrature of the Parabola، أثبت أرخميدس أن المساحة المحصورة بين قطع مكافئ وخط مستقيم هي 4/3 مضروبة في مساحة مثلث تتساوى قاعدته وارتفاعه. وقد عبر عن الحل للمسألة كمتسلسلة هندسية تجمع إلى ما لانهاية نسبتها 1/4:

أرخميدس وط (π)

حدد أرخميدس قيمة ط (الپاي) وهي نسبة محيط الدائرة إلى قطرها، أو بكلام آخر محيط الدائرة أطول كم مرة من قطرها، وهذه القيمة تستخدم في حساب مساحات الدوائر وما شابهها وأحجام الكرات والاسطوانات. وطريقته في حساب ذلك اعتمدت على رسم أشكال هندسية متساوية الأضلاع داخل وخارج الدائرة حتى حدد حدوداً لقيمة π (باي).

وقال أرشميدس: إن القيمة الدقيقة π (باي) هي 7/22 وعندما وصل إلى قيمة π (باي) اكتشف صعوبة الأرقام اليونانية، وأنها لا تصلح للعمليات الرياضية المعقدة، ومن ثم اقترح نظاماً رقمياً آخر يمكنه تخزين أرقام كبيرة بسهولة. وقيمة π (باي) هي :3.14159,26535,89793,23846,26433,83279,50288,41971,69399,37510 وهي قيمة تقترب من الحقيقة ولا يمكن قياسها تحديداً.

كتاباته

نص كتاب في الكرة والإسطوانة لأرشميدس. انقر على الصورة للمطالعة. |

Archimedes discusses astronomical measurements of the Earth, Sun, and Moon, as well as Aristarchus' heliocentric model of the universe, in the Sand-Reckoner. Without the use of either trigonometry or a table of chords, Archimedes determines the Sun's apparent diameter by first describing the procedure and instrument used to make observations (a straight rod with pegs or grooves),[41][42] applying correction factors to these measurements, and finally giving the result in the form of upper and lower bounds to account for observational error.[30] Ptolemy, quoting Hipparchus, also references Archimedes' solstice observations in the Almagest. This would make Archimedes the first known Greek to have recorded multiple solstice dates and times in successive years.[31]

Cicero's De re publica portrays a fictional conversation taking place in 129 BC. After the capture of Syracuse in the Second Punic War, Marcellus is said to have taken back to Rome two mechanisms which were constructed by Archimedes and which showed the motion of the Sun, Moon and five planets. Cicero also mentions similar mechanisms designed by Thales of Miletus and Eudoxus of Cnidus. The dialogue says that Marcellus kept one of the devices as his only personal loot from Syracuse, and donated the other to the Temple of Virtue in Rome. Marcellus's mechanism was demonstrated, according to Cicero, by Gaius Sulpicius Gallus to Lucius Furius Philus, who described it thus:[43][44]

Hanc sphaeram Gallus cum moveret, fiebat ut soli luna totidem conversionibus in aere illo quot diebus in ipso caelo succederet, ex quo et in caelo sphaera solis fieret eadem illa defectio, et incideret luna tum in eam metam quae esset umbra terrae, cum sol e regione.

When Gallus moved the globe, it happened that the Moon followed the Sun by as many turns on that bronze contrivance as in the sky itself, from which also in the sky the Sun's globe became to have that same eclipse, and the Moon came then to that position which was its shadow on the Earth when the Sun was in line.

This is a description of a small planetarium. Pappus of Alexandria reports on a now lost treatise by Archimedes dealing with the construction of these mechanisms entitled On Sphere-Making.[34][45] Modern research in this area has been focused on the Antikythera mechanism, another device built ح. 100 BC probably designed with a similar purpose.[46] Constructing mechanisms of this kind would have required a sophisticated knowledge of differential gearing.[47] This was once thought to have been beyond the range of the technology available in ancient times, but the discovery of the Antikythera mechanism in 1902 has confirmed that devices of this kind were known to the ancient Greeks.[48][49]

- في اتزان المستويات On the Equilibrium of Planes (مجلدان).[50]

- في قياس الدائرة

- في اللوالب On Spirals

- في الكرة والإسطوانة (مجلدان)

- في القمعيات والكرويات On Conoids and Spheroids

- الأجسام الطافية (مجلدان)

- The Quadrature of the Parabola

- (O)stomachion

- منهج النظريات الميكانيكية

رق أرخميدس الممسوح

ذكراه

Sometimes called the father of mathematics and mathematical physics, Archimedes had a wide influence on mathematics and science.[51]

الرياضيات والفيزياء

Historians of science and mathematics almost universally agree that Archimedes was the finest mathematician from antiquity. Eric Temple Bell, for instance, wrote:

Any list of the three "greatest" mathematicians of all history would include the name of Archimedes. The other two usually associated with him are Newton and Gauss. Some, considering the relative wealth—or poverty—of mathematics and physical science in the respective ages in which these giants lived, and estimating their achievements against the background of their times, would put Archimedes first.[52]

Likewise, Alfred North Whitehead and George F. Simmons said of Archimedes:

... in the year 1500 Europe knew less than Archimedes who died in the year 212 BC ...[53]

If we consider what all other men accomplished in mathematics and physics, on every continent and in every civilization, from the beginning of time down to the seventeenth century in Western Europe, the achievements of Archimedes outweighs it all. He was a great civilization all by himself.[54]

Reviel Netz, Suppes Professor in Greek Mathematics and Astronomy at Stanford University and an expert in Archimedes notes:

And so, since Archimedes led more than anyone else to the formation of the calculus and since he was the pioneer of the application of mathematics to the physical world, it turns out that Western science is but a series of footnotes to Archimedes. Thus, it turns out that Archimedes is the most important scientist who ever lived.[55]

Leonardo da Vinci repeatedly expressed admiration for Archimedes, and attributed his invention Architonnerre to Archimedes.[56][57][58] Galileo called him "superhuman" and "my master",[59][60] while Huygens said, "I think Archimedes is comparable to no one", consciously emulating him in his early work.[61] Leibniz said, "He who understands Archimedes and Apollonius will admire less the achievements of the foremost men of later times".[62] Gauss's heroes were Archimedes and Newton,[63] and Moritz Cantor, who studied under Gauss in the University of Göttingen, reported that he once remarked in conversation that "there had been only three epoch-making mathematicians: Archimedes, Newton, and Eisenstein".[64]

The inventor Nikola Tesla praised him, saying:

Archimedes was my ideal. I admired the works of artists, but to my mind, they were only shadows and semblances. The inventor, I thought, gives to the world creations which are palpable, which live and work.[65]

التكريم والتخليد

هناك فوهة على سطح القمر اسمها أرخميدس (29.7° N, 4.0° W) تكريماً له، كما أن هناك سلسلة جبال قمرية، Montes Archimedes (25.3° N, 4.6° W).[66] الكويكب 3600 أرخميدس مسمى أيضاً على اسمه.[67]

مدالية فيلدز للإنجاز البارز في الرياضيات تحمل پورتريه لأرخميدس، مع إثباته المتعلق بالكرة والأسطوانة. The inscription around the head of Archimedes is a quote attributed to him which reads in Latin: "Transire suum pectus mundoque potiri" (Rise above oneself and grasp the world).[68]

ظهر أرخميدس على طوابع بريدية أصدرتها ألمانيا الشرقية (1973)، اليونان (1983)، إيطاليا (1983)، نيكاراگوا (1971)، سان مارينو (1982) واسبانيا (1963).[69]

صيحة التعجب Eureka! المنسوبة إلى أرخميدس أصبحت شعار ولاية كاليفورنيا. وفي هذه الحالة فالتعجب يعود إلى اكتشاف الذهب بالقرب من طاحونة سوتر عام 1848 الذي أشعل الهروع لذهب كاليفورنيا.[70]

انظر أيضاً

|

|

الهوامش

a. ^ In the preface to On Spirals addressed to Dositheus of Pelusium, Archimedes says that "many years have elapsed since Conon's death." Conon of Samos lived c. 280–220 BC, suggesting that Archimedes may have been an older man when writing some of his works.

b. ^ The treatises by Archimedes known to exist only through references in the works of other authors are: On Sphere-Making and a work on polyhedra mentioned by Pappus of Alexandria; Catoptrica, a work on optics mentioned by Theon of Alexandria; Principles, addressed to Zeuxippus and explaining the number system used in The Sand Reckoner; On Balances and Levers; On Centers of Gravity; On the Calendar. Of the surviving works by Archimedes, T. L. Heath offers the following suggestion as to the order in which they were written: On the Equilibrium of Planes I, The Quadrature of the Parabola, On the Equilibrium of Planes II, On the Sphere and the Cylinder I, II, On Spirals, On Conoids and Spheroids, On Floating Bodies I, II, On the Measurement of a Circle, The Sand Reckoner.

c. ^ Boyer, Carl Benjamin A History of Mathematics (1991) ISBN 0-471-54397-7 "Arabic scholars inform us that the familiar area formula for a triangle in terms of its three sides, usually known as Heron's formula — k = √(s(s − a)(s − b)(s − c)), where s is the semiperimeter — was known to Archimedes several centuries before Heron lived. Arabic scholars also attribute to Archimedes the 'theorem on the broken chord' ... Archimedes is reported by the Arabs to have given several proofs of the theorem."

d. ^ "It was usual to smear the seams or even the whole hull with pitch or with pitch and wax". In Νεκρικοὶ Διάλογοι (Dialogues of the Dead), Lucian refers to coating the seams of a skiff with wax, a reference to pitch (tar) or wax.[71]

المصادر

- ^ Knorr, Wilbur R. (1978). "Archimedes and the spirals: The heuristic background". Historia Mathematica. 5 (1): 43–75. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(78)90134-9.

"To be sure, Pappus does twice mention the theorem on the tangent to the spiral [IV, 36, 54]. But in both instances the issue is Archimedes' inappropriate use of a 'solid neusis,' that is, of a construction involving the sections of solids, in the solution of a plane problem. Yet Pappus' own resolution of the difficulty [IV, 54] is by his own classification a 'solid' method, as it makes use of conic sections." (p. 48)

- ^ "Archimedes". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "Archimedes (c.287 - c.212 BC)". BBC History. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- ^ Calinger, Ronald (1999). A Contextual History of Mathematics. Prentice-Hall. p. 150. ISBN 0-02-318285-7.

Shortly after Euclid, compiler of the definitive textbook, came Archimedes of Syracuse (ca. 287 212 BC), the most original and profound mathematician of antiquity.

- ^ "Archimedes of Syracuse". The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. January 1999. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ O'Connor, J.J. and Robertson, E.F. (February 1996). "A history of calculus". University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bursill-Hall, Piers. "Galileo, Archimedes, and Renaissance engineers". sciencelive with the University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ "Archimedes – The Palimpsest". Walters Art Museum. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ أ ب Rorres, Chris. "Death of Archimedes: Sources". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 2007-01-02. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "death" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Plutarch. "Parallel Lives Complete e-text from Gutenberg.org". Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ O'Connor, J.J. and Robertson, E.F. "Archimedes of Syracuse". University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ج.ت. "أرخميدس". الموسوعة العربية. Retrieved 2015-09-01.

- ^ Finlay, M. (2013). Constructing ancient mechanics Archived 14 أبريل 2021 at the Wayback Machine [Master's thesis]. University of Glassgow.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "The Law of the Lever According to Archimedes". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ^ Clagett, Marshall (2001). Greek Science in Antiquity. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-41973-2.

- ^ Dougherty, F.C.; Macari, J.; Okamoto, C. "Pulleys". Society of Women Engineers. Archived from the original on 18 July 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Quoted by Pappus of Alexandria in Synagoge, Book VIII

- ^ Berryman, S. (2020). "How Archimedes Proposed to Move the Earth". Isis. 111 (3): 562–567. doi:10.1086/710317.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Archimedes's Claw – Illustrations and Animations – a range of possible designs for the claw". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Carroll, Bradley W. "Archimedes' Claw: watch an animation". Weber State University. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ^ "Ancient Greek Scientists: Hero of Alexandria". Technology Museum of Thessaloniki. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ Archimedes's contemporary Diocles made no mention of Archimedes or burning ships in his treatise about focusing reflectors. Diocles, On Burning Mirors, ed. G. J. Toomer, Berlin: Springer, 1976. Lucian, Hippias, ¶ 2, in Lucian, vol. 1, ed. A. M. Harmon, Harvard, 1913, قالب:Pgs, says Archimedes burned ships with his techne, "skill". Galen, On temperaments 3.2, mentions pyreia, "torches". Anthemius of Tralles, On miraculous engines 153 [Westerman]. Knorr, Wilbur (1983). "The Geometry of Burning-Mirrors in Antiquity". Isis. 74 (1): 53–73. doi:10.1086/353176. ISSN 0021-1753.

- ^ Simms, D. L. (1977). "Archimedes and the Burning Mirrors of Syracuse". Technology and Culture. 18 (1): 1–24. doi:10.2307/3103202. JSTOR 3103202.

- ^ "Archimedes Death Ray: Testing with MythBusters". MIT. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ John Wesley. "A Compendium of Natural Philosophy (1810) Chapter XII, Burning Glasses". Online text at Wesley Center for Applied Theology. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ "TV Review: MythBusters 8.27 – President's Challenge". 13 December 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "World's Largest Solar Furnace". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Evans, James (1 August 1999). "The Material Culture of Greek Astronomy". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 30 (3): 238–307. Bibcode:1999JHA....30..237E. doi:10.1177/002182869903000305.

But even before Hipparchus, Archimedes had described a similar instrument in his Sand-Reckoner. A fuller description of the same sort of instrument is given by Pappus of Alexandria ... Figure 30 is based on Archimedes and Pappus. Rod R has a groove that runs its whole length ... A cylinder or prism C is fixed to a small block that slides freely in the groove (p. 281).

- ^ Toomer, G. J.; Jones, Alexander (7 March 2016). "Astronomical Instruments". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.886. ISBN 9780199381135.

Perhaps the earliest instrument, apart from sundials, of which we have a detailed description is the device constructed by Archimedes (Sand-Reckoner 11-15) for measuring the sun's apparent diameter; this was a rod along which different coloured pegs could be moved.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:3 - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:4 - ^ Cicero. "De re publica 1.xiv §21". thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Cicero (9 February 2005). De re publica Complete e-text in English from Gutenberg.org. Retrieved 18 September 2007 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:5 - ^ Wright, Michael T. (2017). "Archimedes, Astronomy, and the Planetarium". In Rorres, Chris (ed.). Archimedes in the 21st Century: Proceedings of a World Conference at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Trends in the History of Science. Cham: Springer. pp. 125–141. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-58059-3_7. ISBN 978-3-319-58059-3.

- ^ Noble Wilford, John (31 July 2008). "Discovering How Greeks Computed in 100 B.C." The New York Times. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ "The Antikythera Mechanism II". Stony Brook University. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ "Ancient Moon 'computer' revisited". BBC News. 29 November 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Spheres and Planetaria". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Quoted in T. L. Heath, Works of Archimedes, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-42084-1.

- ^ Evans, James (1 August 1999). "The Material Culture of Greek Astronomy". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 30 (3): 238–307. Bibcode:1999JHA....30..237E. doi:10.1177/002182869903000305.

But even before Hipparchus, Archimedes had described a similar instrument in his Sand-Reckoner. A fuller description of the same sort of instrument is given by Pappus of Alexandria ... Figure 30 is based on Archimedes and Pappus. Rod R has a groove that runs its whole length ... A cylinder or prism C is fixed to a small block that slides freely in the groove (p. 281).

- ^ Toomer, G. J.; Jones, Alexander (7 March 2016). "Astronomical Instruments". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.886. ISBN 9780199381135.

Perhaps the earliest instrument, apart from sundials, of which we have a detailed description is the device constructed by Archimedes (Sand-Reckoner 11-15) for measuring the sun's apparent diameter; this was a rod along which different coloured pegs could be moved.

- ^ Cicero. "De re publica 1.xiv §21". thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Cicero (9 February 2005). De re publica Complete e-text in English from Gutenberg.org. Retrieved 18 September 2007 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Wright, Michael T. (2017). "Archimedes, Astronomy, and the Planetarium". In Rorres, Chris (ed.). Archimedes in the 21st Century: Proceedings of a World Conference at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Trends in the History of Science. Cham: Springer. pp. 125–141. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-58059-3_7. ISBN 978-3-319-58059-3.

- ^ Noble Wilford, John (31 July 2008). "Discovering How Greeks Computed in 100 B.C." The New York Times. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ "The Antikythera Mechanism II". Stony Brook University. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ "Ancient Moon 'computer' revisited". BBC News. 29 November 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Spheres and Planetaria". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Heath, T.L. "The Works of Archimedes (1897). The unabridged work in PDF form (19 MB)". Archive.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Father of mathematics: Jane Muir, Of Men and Numbers: The Story of the Great Mathematicians, p 19.

Father of mathematical physics: James H. Williams Jr., Fundamentals of Applied Dynamics, p 30., Carl B. Boyer, Uta C. Merzbach, A History of Mathematics, p 111., Stuart Hollingdale, Makers of Mathematics, p 67., Igor Ushakov, In the Beginning, Was the Number (2), p 114.

- ^ E.T. Bell, Men of Mathematics, p 20.

- ^ Alfred North Whitehead. "The Influence of Western Medieval Culture Upon the Development of Modern Science". Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ George F. Simmons, Calculus Gems: Brief Lives and Memorable Mathematics, p 43.

- ^ Reviel Netz, William Noel, The Archimedes Codex: Revealing The Secrets of the World's Greatest Palimpsest

- ^ "The Steam-Engine". Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle. Vol. I, no. 11. Nelson: National Library of New Zealand. 21 May 1842. p. 43. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ The Steam Engine. The Penny Magazine. 1838. p. 104.

- ^ Robert Henry Thurston (1996). A History of the Growth of the Steam-Engine. Elibron. p. 12. ISBN 1-4021-6205-7.

- ^ Matthews, Michael. Time for Science Education: How Teaching the History and Philosophy of Pendulum Motion Can Contribute to Science Literacy. p. 96.

- ^ "Archimedes – Galileo Galilei and Archimedes". exhibits.museogalileo.it. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ Yoder, J. (1996). "Following in the footsteps of geometry: the mathematical world of Christiaan Huygens". De Zeventiende Eeuw. Jaargang 12.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B., and Uta C. Merzbach. 1968. A History of Mathematics. ch. 7.

- ^ Jay Goldman, The Queen of Mathematics: A Historically Motivated Guide to Number Theory, p 88.

- ^ E.T. Bell, Men of Mathematics, p 237

- ^ W. Bernard Carlson, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, p 57

- ^ Friedlander, Jay and Williams, Dave. "Oblique view of Archimedes crater on the Moon". NASA. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Planetary Data System". NASA. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ "Fields Medal". International Mathematical Union. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Stamps of Archimedes". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ^ "California Symbols". California State Capitol Museum. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- ^ Casson, Lionel (1995). Ships and seamanship in the ancient world. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-0-8018-5130-8.

قراءات إضافية

- Boyer, Carl Benjamin (1991). A History of Mathematics. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

- Clagett, Marshall (1964–1984). Archimedes in the Middle Ages. Vol. 5 vols. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Dijksterhuis, E.J. (1987). Archimedes. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 0-691-08421-1. Republished translation of the 1938 study of Archimedes and his works by an historian of science.

- Gow, Mary (2005). Archimedes: Mathematical Genius of the Ancient World. Enslow Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-7660-2502-0.

- Hasan, Heather (2005). Archimedes: The Father of Mathematics. Rosen Central. ISBN 978-1-4042-0774-5.

- Heath, T.L. (1897). Works of Archimedes. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-42084-1. Complete works of Archimedes in English.

- Netz, Reviel and Noel, William (2007). The Archimedes Codex. Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 0-297-64547-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pickover, Clifford A. (2008). Archimedes to Hawking: Laws of Science and the Great Minds Behind Them. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533611-5.

- Simms, Dennis L. (1995). Archimedes the Engineer. Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd. ISBN 0-7201-2284-8.

- Stein, Sherman (1999). Archimedes: What Did He Do Besides Cry Eureka?. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 0-88385-718-9.

أعمال أرخميدس أونلاين

- Text in Classical Greek: PDF scans of Heiberg's edition of the Works of Archimedes, now in the public domain

- In English translation: The Works of Archimedes, trans. T.L. Heath; supplemented by The Method of Mechanical Theorems, trans. L.G. Robinson

وصلات خارجية

| Find more about أرخميدس at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| News stories from Wikinews | |

| Quotations from Wikiquote | |

| Source texts from Wikisource | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

| Learning resources from Wikiversity | |

- Archimedes on In Our Time at the BBC. (listen now)

- أعمال من Archimedes في مشروع گوتنبرگ

- Works by or about أرخميدس at Internet Archive

- أرخميدس at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- أرخميدس at PhilPapers

- The Archimedes Palimpsest project at The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland

- The Mathematical Achievements and Methodologies of Archimedes

- قالب:MathPages

- قالب:MathPages

- Photograph of the Sakkas experiment in 1973

- Testing the Archimedes steam cannon

- Stamps of Archimedes

- Eureka! 1,000-year-old text by Greek maths genius Archimedes goes on display Daily Mail, October 18, 2011.

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- الصفحات بخصائص غير محلولة

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using infobox scientist with unknown parameters

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- مقالات ناطقة

- أرخميدس

- مواليد 287 ق.م.

- وفيات 212 ق.م.

- أشخاص من صقلية

- مهندسون يونانيون قدماء

- مخترعون يونانيون قدماء

- علماء رياضيات يونانيون قدماء

- فيزيائيون يونانيون قدماء

- فلاسفة هلينيون

- يونانيون صقليون

- رياضياتيون صقليون

- علماء صقليون

- علماء مقتولون

- علماء الهندسة الرياضية

- ضحايا قتل يونانيون

- رياضياتيون