إپيقور

| مجد مقصوص ساهم بشكل رئيسي في تحرير هذا المقال

|

Epicurus | |

|---|---|

Roman marble bust of Epicurus | |

| وُلِدَ | February 341 BC Samos, Greece |

| توفي | 270 BC (aged about 72) Athens, Greece |

| العصر | Hellenistic philosophy |

| المنطقة | Western philosophy |

| المدرسة | Epicureanism |

الاهتمامات الرئيسية | |

الأفكار البارزة | Attributed: |

التأثر

| |

إپيقور ( Epicurus ؛ [2] باليونانية: Ἐπίκουρος Epikouros؛ 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influenced by Democritus, Aristippus, Pyrrho,[3] and possibly the Cynics, he turned against the Platonism of his day and established his own school, known as "the Garden", in Athens. Epicurus and his followers were known for eating simple meals and discussing a wide range of philosophical subjects. He openly allowed women and slaves[4] to join the school as a matter of policy. Of the over 300 works said to have been written by Epicurus about various subjects, the vast majority have been destroyed. Only three letters written by him—the letters to Menoeceus, Pythocles, and Herodotus—and two collections of quotes—the Principal Doctrines and the Vatican Sayings—have survived intact, along with a few fragments of his other writings. As a result of his work's destruction, most knowledge about his philosophy is due to later authors, particularly the biographer Diogenes Laërtius, the Epicurean Roman poet Lucretius and the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus, and with hostile but largely accurate accounts by the Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus, and the Academic Skeptic and statesman Cicero.

Epicurus asserted that philosophy's purpose is to attain as well as to help others attain happy (eudaimonic), tranquil lives characterized by ataraxia (peace and freedom from fear) and aponia (the absence of pain). He advocated that people were best able to pursue philosophy by living a self-sufficient life surrounded by friends. He taught that the root of all human neurosis is death denial and the tendency for human beings to assume that death will be horrific and painful, which he claimed causes unnecessary anxiety, selfish self-protective behaviors, and hypocrisy. According to Epicurus, death is the end of both the body and the soul and therefore should not be feared. Epicurus taught that although the gods exist, they have no involvement in human affairs. He taught that people should act ethically not because the gods punish or reward them for their actions but because, due to the power of guilt, amoral behavior would inevitably lead to remorse weighing on their consciences and as a result, they would be prevented from attaining ataraxia.

Epicurus was an empiricist, meaning he believed that only the senses are a reliable source of knowledge about the world. He derived much of his physics and cosmology from the earlier philosopher Democritus (ح. 460–ح. 370 BC). Like Democritus, Epicurus taught that the universe is infinite and eternal and that all matter is made up of extremely tiny, invisible particles known as atoms. All occurrences in the natural world are ultimately the result of atoms moving and interacting in empty space. Epicurus deviated from Democritus by proposing the idea of atomic "swerve", which holds that atoms may deviate from their expected course, thus permitting humans to possess free will in an otherwise deterministic universe.

Though popular, Epicurean teachings were controversial from the beginning. Epicureanism reached the height of its popularity during the late years of the Roman Republic. It died out in late antiquity, subject to hostility from early Christianity. Throughout the Middle Ages Epicurus was popularly, though inaccurately, remembered as a patron of drunkards, whoremongers, and gluttons. His teachings gradually became more widely known in the fifteenth century with the rediscovery of important texts, but his ideas did not become acceptable until the seventeenth century, when the French Catholic priest Pierre Gassendi revived a modified version of them, which was promoted by other writers, including Walter Charleton and Robert Boyle. His influence grew considerably during and after the Enlightenment, profoundly impacting the ideas of major thinkers, including John Locke, Thomas Jefferson, Jeremy Bentham, and Karl Marx.

سيرته

وُلِدَ في جزيرة ساموس، قام بإدارة مدرسة للفلسفة في أثينا منذ عام 306 قبل الميلاد وحتى وفاته. كان أبيقور وافر الكتابة، منها ثلاث رسائل تلخص تعاليمه، ومن أهم المراجع المؤرخة لفلسفته قصيدة طويلة للشاعر الروماني لوكريشيس عنوانها: في طبيعة الأشياء. ومما يميزه جعله اللذة في مرتبة الحكمة.

النشأة والمؤثرات

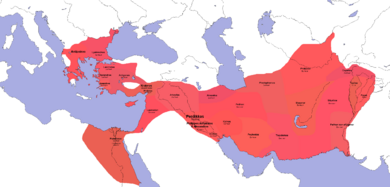

Epicurus was born in the Athenian settlement on the Aegean island of Samos in February 341 BC.[5][6][7] His parents, Neocles and Chaerestrate, were both Athenian-born, and his father was an Athenian citizen.[5] Epicurus grew up during the final years of the Greek Classical Period.[8] Plato had died seven years before Epicurus was born and Epicurus was seven years old when Alexander the Great crossed the Hellespont into Persia.[8] As a child, Epicurus would have received a typical ancient Greek education.[8] As such, according to Norman Wentworth DeWitt, "it is inconceivable that he would have escaped the Platonic training in geometry, dialectic, and rhetoric."[8] Epicurus is known to have studied under the instruction of a Samian Platonist named Pamphilus, probably for about four years.[8] His Letter of Menoeceus and surviving fragments of his other writings strongly suggest that he had extensive training in rhetoric.[8][9] After the death of Alexander the Great, Perdiccas expelled the Athenian settlers on Samos to Colophon, on the coast of what is now Turkey.[10][9] After the completion of his military service, Epicurus joined his family there. He studied under Nausiphanes, who followed the teachings of Democritus,[9][10] and later those of Pyrrho,[11][12] whose way of life Epicurus greatly admired.[13]

Epicurus's teachings were heavily influenced by those of earlier philosophers, particularly Democritus. Nonetheless, Epicurus differed from his predecessors on several key points of determinism and vehemently denied having been influenced by any previous philosophers, whom he denounced as "confused". Instead, he insisted that he had been "self-taught".[14][15][16] According to DeWitt, Epicurus's teachings also show influences from the contemporary philosophical school of Cynicism.[8] The Cynic philosopher Diogenes of Sinope was still alive when Epicurus would have been in Athens for his required military training and it is possible they may have met.[8] Diogenes's pupil Crates of Thebes (ح. 365 – ح. 285 BC) was a close contemporary of Epicurus.[8] Epicurus agreed with the Cynics' quest for honesty, but rejected their "insolence and vulgarity", instead teaching that honesty must be coupled with courtesy and kindness.[8] Epicurus shared this view with his contemporary, the comic playwright Menander.[8]

Epicurus's Letter to Menoeceus, possibly an early work of his, is written in an eloquent style similar to that of the Athenian rhetorician Isocrates (436–338 BC),[8] but, for his later works, he seems to have adopted the bald, intellectual style of the mathematician Euclid.[8] Epicurus's epistemology also bears an unacknowledged debt to the later writings of Aristotle (384–322 BC), who rejected the Platonic idea of hypostatic Reason and instead relied on nature and empirical evidence for knowledge about the universe.[8] During Epicurus's formative years, Greek knowledge about the rest of the world was rapidly expanding due to the Hellenization of the Near East and the rise of Hellenistic kingdoms.[8] Epicurus's philosophy was consequently more universal in its outlook than those of his predecessors, since it took cognizance of non-Greek peoples as well as Greeks.[8] He may have had access to the now-lost writings of the historian and ethnographer Megasthenes, who wrote during the reign of Seleucus I Nicator (ruled 305–281 BC).[8]

سيرته كمعلم

During Epicurus's lifetime, Platonism was the dominant philosophy in higher education.[8] Epicurus's opposition to Platonism formed a large part of his thought.[8][18] Over half of the forty Principal Doctrines of Epicureanism are flat contradictions of Platonism.[8] In around 311 BC, Epicurus, when he was around thirty years old, began teaching in Mytilene.[8][9] Around this time, Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, arrived in Athens, at the age of about twenty-one, but Zeno did not begin teaching what would become Stoicism for another twenty years.[8] Although later texts, such as the writings of the first-century BC Roman orator Cicero, portray Epicureanism and Stoicism as rivals,[8] this rivalry seems to have only emerged after Epicurus's death.[8][8]

Epicurus's teachings caused strife in Mytilene and he was forced to leave. He then founded a school in Lampsacus before returning to Athens in ح. 306 BC, where he remained until his death.[6] There he founded The Garden (κῆπος), a school named for the garden he owned that served as the school's meeting place, about halfway between the locations of two other schools of philosophy, the Stoa and the Academy.[19][9] The Garden was more than just a school;[7] it was "a community of like-minded and aspiring practitioners of a particular way of life."[7] The primary members were Hermarchus, the financier Idomeneus, Leonteus and his wife Themista, the satirist Colotes, the mathematician Polyaenus of Lampsacus, and Metrodorus of Lampsacus, the most famous popularizer of Epicureanism. His school was the first of the ancient Greek philosophical schools to admit women as a rule rather than an exception,[بحاجة لمصدر] and the biography of Epicurus by Diogenes Laërtius lists female students such as Leontion and Nikidion.[20] An inscription on the gate to The Garden is recorded by Seneca the Younger in epistle XXI of Epistulae morales ad Lucilium: "Stranger, here you will do well to tarry; here our highest good is pleasure."[21]

According to Diskin Clay, Epicurus himself established a custom of celebrating his birthday annually with common meals, befitting his stature as heros ktistes ("founding hero") of the Garden. He ordained in his will annual memorial feasts for himself on the same date (10th of Gamelion month).[22] Epicurean communities continued this tradition,[23] referring to Epicurus as their "saviour" (soter) and celebrating him as hero. The hero cult of Epicurus may have operated as a Garden variety civic religion.[24] However, clear evidence of an Epicurean hero cult, as well as the cult itself, seems buried by the weight of posthumous philosophical interpretation.[25] Epicurus never married and had no known children. He was most likely a vegetarian.[26][27]

الوفاة

Diogenes Laërtius records that, according to Epicurus's successor Hermarchus, Epicurus died a slow and painful death in 270 BC at the age of seventy-two from a stone blockage of his urinary tract.[28][29] Despite being in immense pain, Epicurus is said to have remained cheerful and to have continued to teach until the very end.[28] Possible insights into Epicurus's death may be offered by the extremely brief Epistle to Idomeneus, included by Diogenes Laërtius in Book X of his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers.[7] The authenticity of this letter is uncertain and it may be a later pro-Epicurean forgery intended to paint an admirable portrait of the philosopher to counter the large number of forged epistles in Epicurus's name portraying him unfavorably.[7]

I have written this letter to you on a happy day to me, which is also the last day of my life. For I have been attacked by a painful inability to urinate, and also dysentery, so violent that nothing can be added to the violence of my sufferings. But the cheerfulness of my mind, which comes from the recollection of all my philosophical contemplation, counterbalances all these afflictions. And I beg you to take care of the children of Metrodorus, in a manner worthy of the devotion shown by the young man to me, and to philosophy.[30]

If authentic, this letter would support the tradition that Epicurus was able to remain joyful to the end, even in the midst of his suffering.[7] It would also indicate that he maintained a special concern for the wellbeing of children.[7]

مدرسته

مقالة مفصلة: إپيقورية

مقالة مفصلة: إپيقورية

تعاليمه

التبأ بالعلم والأخلاق

المتعة بعدم وجود المعاناة

عهده

أعماله

Hero cult

في الأدب والثقافة العامة

الهوامش

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbuyu - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةjones - ^ Diogenes Laertius, Book IX, Chapter 11, Section 64.

- ^ "Diogenes Laertius, Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers Book X Section 3".

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlaerti2 - ^ أ ب Barnes 1986.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Gordon 2012.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق ك ل م ن هـ DeWitt 1954.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Wasson 2016.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةstanf - ^ Diogenes Laertius, ix.

- ^ Sextus Empiricus, adv. Math. i. 1.

- ^ Hicks, Robert Drew. Diogenes Laërtius "Lives of the Eminent Philosophers" Book IX, Chapter 11, Section 61.

- ^ Huby, Pamela M. (1978). "Epicurus' Attitude to Democritus". Phronesis. 23 (1): 80–86. doi:10.1163/156852878X00235. JSTOR 4182030.

- ^ Erler 2011.

- ^ Fish & Sanders 2011.

- ^ Zanker, Paul. The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity. III. The Rigors of Thinking. The "Throne" of Epicurus. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 1995.

- ^ Long 1999.

- ^ David Konstan (2018). "Epicurus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Book X, Section 7

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةintra - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةsmitwood - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةglad - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةnussb - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةclay - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbrita - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةdombr - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbitsori - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlaerti3 - ^ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, 10.22 (trans. C.D. Yonge).

انظر أيضا

قرااءت إضافية

- Bailey C. (1928) The Greek Atomists and Epicurus, Oxford.

- Bakalis Nikolaos (2005) Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments, Trafford Publishing, ISBN 1-4120-4843-5

- Digireads.com The Works of Epicurus, January 2004.

- Eugene O’ Connor The Essential Epicurus, Prometheus Books, New York 1993.

- Edelstein Epicureanism, Two Collections of Fragments and Studies Garland Publ. March 1987

- Farrington, Benjamin. Science and Politics in the Ancient World, 2nd ed. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1965. A Marxist interpretation of Epicurus, the Epicurean movement, and its opponents.

- John Martin Fischer (1993) "The Metaphysics of Death", Stanford University Press, ISBN 0804721041

- Gordon, Pamela. "Epicurus in Lycia: The Second-Century World of Diogenes of Oenoanda." 1997

- Gottlieb, Anthony. The Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance. London: Penguin, 2001. ISBN 0-14-025274-6

- Inwood, Brad, tr. The Epicurus Reader, Hackett Publishing Co, March 1994.

- Oates Whitney Jenning, The Stoic and Epicurean philosophers, The Complete Extant Writings of Epicurus, Epictetus, Lucretius and Marcus Aurelius, Random House, 9th printing 1940.

- Panicha, George A. Epicurus, Twayne Publishers, 1967

- Prometheus Books, Epicurus Fragments, August 1992.

- Russel M. Geer Letters, Principal Doctrines, Vatican Sayings, Bobbs-Merrill Co, January 1964.

- Diogenes of Oinoanda. The Epicurean Inscription, edited with Introduction, Translation and Notes by Martin Ferguson Smith, Bibliopolis, Naples 1993.

وصلات خارجية

- Epicurus.info - Epicurean Philosophy Online: features classical e-texts & photos of Epicurean artifacts.

- Epicurus.net - Epicurus and Epicurean Philosophy

- Epicurus entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy by David Konstan

- Epicurus entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy by Tim O’Keefe

Diogenes Laërtius, Life of Epicurus, translated by Robert Drew Hicks (1925).

- Epicurus & Lucretius - Small article by "P. Dionysius Mus"

- The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature - Karl Marx’s doctoral thesis.

- "Epicurus on Happiness" - A documentary on the philosophy of Epicurus, first 11:25 of below, Greek subtitles.

- Epicurus's Guide to Happiness - 24 minute documentary, Alain de Botton, UK Channel 4, no subtitles.

- Epicurus on Free Will

- Principal Doctrines

- Vatican Sayings

- The Garden of Epicurus - useful summary of the teachings of Epicurus

- Letters

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- مقالات جيدة

- Use dmy dates from March 2020

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2019

- مواليد 341 ق.م.

- وفيات 270 ق.م.

- يونانيو القرن الرابع ق.م.

- يونانيو القرن الثالث ق.م.

- فلاسفة القرن الثالث ق.م.

- كتاب القرن الثالث ق.م.

- فلاسفة يونانيون قدماء

- يونانيون قدماء اتهموا أو وصفوا بالالحاد

- ساموسيون قدماء

- فلاسفة إبيقوريون

- Greek historical hero cult

- فلاسفة العصر الهليني

- فلاسفة الأخلاق

- فلاسفة العلوم