ديادوخي

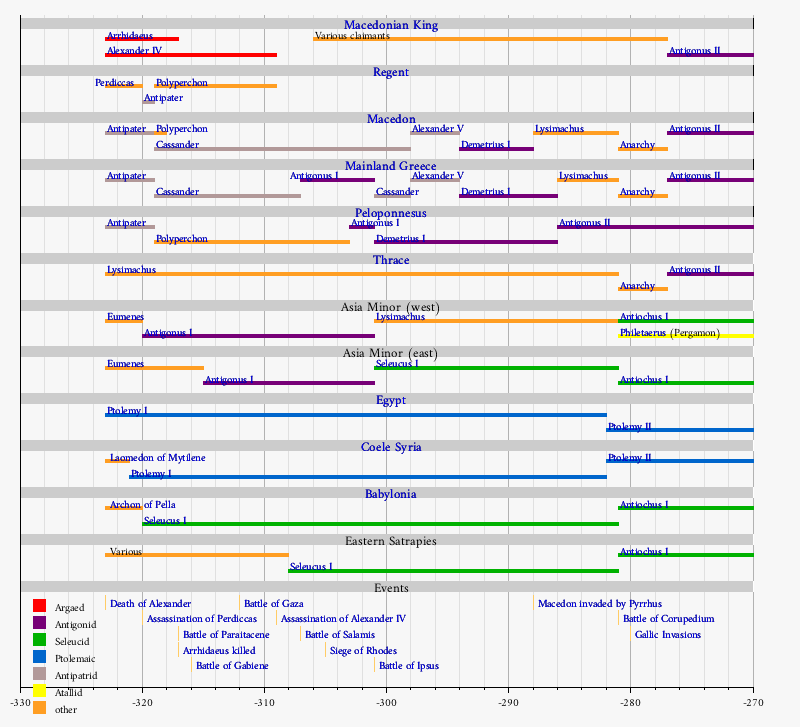

الديادوخي (/daɪˈædəkaɪ/؛ من باليونانية: Διάδοχοι، أو ملوك الطوائف أو خلفاء الطوائف[1] (الجمع اللاتيني: Diadochus من اللفظة اليونانية:Διάδοχοι أي دايودوخوي والتي تعني "الخلفاء") هم الخصوم المتصارعين، من قادة عسكريين وأقارب وأصدقاء الإسكندر الأكبر، الذين سعوا لأن يحكموا امبراطوريته بعد موته في عام 323 ق.م. في الحروب المعروفة بحروب ملوك الطوائف وقد كانت بداية ملؤها الاضطرابات للحقبة الهلنستية. The Wars of the Diadochi mark the beginning of the Hellenistic period from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indus River Valley.

The most notable Diadochi include Ptolemy, Antigonus, Cassander, and Seleucus as the last remaining at the end of the Wars of the Successors, ruling in Egypt, Asia-Minor, Macedon and Persia respectively, all forging dynasties lasting several centuries.[2]

خلفية

الدور القديم

عندما مات الإسكندر الأكبر (10 يونيو، 323 ق م)، ترك خلفه امبراطورية كبرى تألفت بشكل أساسي من أقاليم شبه مستقلة. وقد امتدت امبراطورية الإسكندر من منشأه في مقدونيا، والدول المدن الإغريقية التي أخضعها والده ووصولاً إلى باخترة وأجزاء من الهند في الشرق. وقد ضمت أجزاء من منطقة البلقان المعاصر، وهضبة الأناضول وبلاد الشام ومصر وبلاد الرافدين (بابل)، ومعظم أجزاء فارس المنهارة، ما عدا بعض الأراضي التي تبعت الأخمينيين في آسيا الوسطى.

In ancient Greek, diadochos[3] is a noun (substantive or adjective) formed from the verb, diadechesthai, "succeed to,"[4] a compound of dia- and dechesthai, "receive."[5] The word-set descends straightforwardly from Indo-European *dek-, "receive", the substantive forms being from the o-grade, *dok-.[6] Some important English reflexes are dogma, "a received teaching," decent, "fit to be received," paradox, "against that which is received." The prefix dia- changes the meaning slightly to add a social expectation to the received. The diadochos, being a successor in command or any other office, expects to receive that office.

باسيليوس

It was exactly this expectation that contributed to strife in the Alexandrine and Hellenistic Ages, beginning with Alexander. Philip had married a woman who changed her name to Olympias to honor the coincidence of Philip's victory in the Olympic Games and Alexander's birth, an act that suggests love may have been a motive as well. Macedon's chief office was the basileia, or monarchy, the chief officer being the basileus, now the signatory title of Philip. Their son and heir, Alexander, was raised with care, being educated by select prominent philosophers. Philip is said to have wept for joy when Alexander performed a feat of which no one else was capable, taming the wild horse, Bucephalus, at his first attempt in front of a skeptical audience including the king. Amidst the cheering onlookers Philip swore that Macedonia was not large enough for Alexander.[7]

Philip built Macedonia into the leading military state of the Balkans. He had acquired his expertise fighting for Thebes and Greek freedom under his patron, Epaminondas. When Alexander was a teenager, Philip was planning a military solution to the contention with the Persian Empire. In the opening campaign against Byzantium he made Alexander "regent" (kurios) in his absence. Alexander used every opportunity to further his father's victories, expecting that he would be a part of them. At the report of each of Philip's victories, Alexander was said to lament that his father would leave him nothing of note to do.[بحاجة لمصدر]

There was a source of disaffection, however. Plutarch reports that Alexander and his mother bitterly reproached him for his numerous affairs among the women of his court.[8] Philip then fell in love and married a young woman, Cleopatra, when he was too old for marriage. (Macedonian kings traditionally had multiple wives.) Alexander was at the wedding banquet when Attalus, Cleopatra's uncle, made a remark that seemed inappropriate to him. He asked the Macedonians to pray for an "heir to the kingship" (diadochon tes basileias). Rising to his feet Alexander shouted, using the royal "we," "Do we seem like bastards (nothoi) to you, evil-minded man?" and threw a cup at him.[بحاجة لمصدر] The inebriated Philip, rising to his feet and drawing his sword to defend Attalus, promptly fell. Making a comment that the man who was preparing to cross from Europe to Asia could not cross from one couch to another, Alexander departed, to escort his mother to her native Epirus and to wait himself in Illyria. Not long after, prompted by Demaratus the Corinthian to mend the dissension in his house, Philip sent Demaratus to bring Alexander home. The expectation by virtue of which Alexander was diadochos was that as the son of Philip, he would inherit Philip's throne.

In 336 BC Philip was assassinated, and the 20-year-old Alexander "received the kingship" (parelabe ten basileian).[9] In the same year Darius succeeded to the throne of Persia as Šâhe Šâhân, "King of Kings," which the Greeks understood as "Great King." The role of the Macedonian basileus was changing fast. Alexander's army was already multinational. Alexander was acquiring dominion over state after state. His presence on the battlefield seemed to ensure immediate victory.

هـِجمون

When Alexander the Great died on June 10, 323 BC, he left behind a huge empire which comprised many essentially independent territories. Alexander's empire stretched from his homeland of Macedon itself, along with the Greek city-states that his father had subdued, to Bactria and parts of India in the east. It included parts of the present day Balkans, Anatolia, the Levant, Egypt, Babylonia, and most of the former Achaemenid Empire, except for some lands the Achaemenids formerly held in Central Asia.

الخلفاء

The hetairoi (Ancient Greek: ἑταῖροι), or companion cavalry, added flexibility to the ancient Macedonian army. The hetairoi were a special cavalry unit composed of general officers without fixed rank, whom Alexander could assign where needed. They were typically from the nobility; many were related to Alexander. A parallel flexible structure in the Achaemenid army facilitated combined units.

Staff meetings to adjust command structure were nearly a daily event in Alexander's army. They created an ongoing expectation among the hetairoi of receiving an important and powerful command, if only for a short term. At the moment of Alexander's death, all possibilities were suddenly suspended. The hetairoi vanished with Alexander, to be replaced instantaneously by the Diadochi, men who knew where they had stood, but not where they would stand now. As there had been no definite ranks or positions of hetairoi, there were no ranks of Diadochi. They expected appointments, but without Alexander they would have to make their own.

For purposes of this presentation, the Diadochi are grouped by their rank and social standing at the time of Alexander's death. These were their initial positions as Diadochi.

كراتروس

Craterus was an infantry and naval commander under Alexander during his conquest of the Achaemenid Empire. After the revolt of his army at Opis on the Tigris in 324, Alexander ordered Craterus to command the veterans as they returned home to Macedonia. Antipater, commander of Alexander's forces in Greece and regent of the Macedonian throne in Alexander's absence, would lead a force of fresh troops back to Persia to join Alexander while Craterus would become regent in his place. When Craterus arrived at Cilicia in 323 BC, news reached him of Alexander's death. Though his distance from Babylon prevented him from participating in the distribution of power, Craterus hastened to Macedonia to assume the protection of Alexander's family. The news of Alexander's death caused the Greeks to rebel in the Lamian War. Craterus and Antipater defeated the rebellion in 322 BC. Despite his absence, the generals gathered at Babylon confirmed Craterus as Guardian of the Royal Family. However, with the royal family in Babylon, the Regent Perdiccas assumed this responsibility until the royal household could return to Macedonia.

أنتيپاتور

Antipater was an adviser to King Philip II, Alexander's father, a role he continued under Alexander. When Alexander left Macedon to conquer Persia in 334 BC, Antipater was named Regent of Macedon and General of Greece in Alexander's absence. In 323 BC, Craterus was ordered by Alexander to march his veterans back to Macedon and assume Antipater's position while Antipater was to march to Persia with fresh troops. Alexander's death that year, however, prevented the order from being carried out. When Alexander's generals gathered at the Partition of Babylon to divide the empire between themselves, Antipater was confirmed as General of Greece while the roles of Regent of the Empire and Guardian of the Royal Family were given to Perdiccas and Craterus, respectively. Together, the three men formed the top ruling group of the empire.

سوماتوفيلاكس

The Somatophylakes were the seven bodyguards of Alexander.

السطارفة المقدونيون

Satraps (Old Persian: xšaθrapāwn) were the governors of the provinces in the Hellenistic empires.

العائلة الملكية

السطارفة والقادة غير المقدونيين

طبقة الإپيگوني

فترة الديادوخي

النضال من أجل الوحدة (323–319 ق.م.)

تقسيم بابل

حدث خلاف داخلي مباشر بعد موت الإسكندر، ذلك أنه لم يسمِّ وريثاً له. فقام مليغروس و المشاة بدعم ترشيح الأخ غير الشقيق للإسكندر، فيليبوس الثالث أرياديوس، بينما قرر بيرديكاس، القائد الأعلى لسلاح الفرسان، انتظار ولادة جنين الإسكندر في رحم زوجته روكسانا. فتم الإتفاق على تسوية، بأن يصبح أرياديوس ملكاً (فصار فيليب الثالث لقبه)، وأن يحكم بصحبة ابن روكسانا، على فرض أن المولود هو ذكر (وقد كان كذلك، وصار اسمه الإسكندر الرابع). وتقرر أن يصبح بيرديكاس الوصي على الإمبراطورية كافة، على أن يكون مليغروس ملازمه. إلا أن بيرديكاس أمر بقتل مليغر وقادة المشاة الآخرين، وتفرد بالإمرة الكاملة.

وقد كوفئ قادة الفرسان الآخرين الذين أيدوا بيرديكاس في إتفاقية قسمة بابلen بمنحهم السطرفيات من أنحاء الامبراطورية المختلفة. فحصل بطليموس على مصر، وحاز لاوميدونen على سوريا و فينيقيا، وأخذ فيلوتاسen إقليم قيليقيا، وأخذ بيثون، وحصل أنتيغونوس على فريجيا و ليكيا و بامفيليا، وحاز أساندرen على كاريا، و ميناندرen على ليديا، وحصل ليسيماخوس على ثراقيا، و نال ليوناتوسen فريجيا الهلسبونتيةen، و نيوبطليموس حصل على أرمينيا. وتقرر أن تبقى مقدونيا وبقية اليونان تحت الحكم المشترك لـ أنتيباتر، الذي كان قد حكمها وصاية عن الإسكندر خلال حملته، ثم عن كراتيروس، ملازم الإسكندر الأكثر قدرة وقوة، كما تقرّر أن يحصل أمير سر الإسكندر الكبير، يومينيس الكارديen على كبادوكيا و بافلاغونيا.

وإلى الشرق، أبقى بيرديكاس في الغالب، ترتيبات الإسكندر على حالها - إذ اتفق أن يحكم الملك تكسيليسen و پوروسen على ممالكهما، وحكم أبو زوجة الإسكندر وخشاردen قندهارا fa en، وحكم سيبيرتيوس en رخج (أراخوسيا) fa en و غدروزي fa en، وحكم ستاسانور en هريوا fa en ودرنغيانا fa en، وحكم فراتافرن en فرثيا و هيركانيا و پوكستاس حكم برسيس و طليبوليموس en تولى مسؤولية کرمانیة en، وحكم أتروبات en ميديا الشمالية، ونال أرخون en حكم بابل وحكم أركسيلاوس شمال بلاد الرافدين.

الثورة في اليونان

وفي الوقت نفسه، شجع خبر وفاة الإسكندر قيام ثورة في اليونان، وقد عرفت باسم الحرب اللمومية. فتوحدت أثينا مع مدن أخرى، وقاموا بمحاصرة أنتيباتر في قلعة مدينة لمياء. فأنجد أنتيباتر بقوة بعث بها ليوناتوس الذي فقتل في خضم إحدى المعارك، ولكن الحرب لم تنته حتى وصول كراتيروس على رأس أسطول بحري هزم به الأثينيين في معركة كرانون en في 5 أيلول، من عام 322 ق م. ولبعض من الوقت، أتى ذلك بحد للمقاومة اليونانية لهيمنة مقدونيا. وفي الوقت نفسه، قمع بيثون ثورة بين المستوطنين اليونانيين في الأجزاء الشرقية من الإمبراطورية، وقام كلاً من بيرديكاس و يومينيس بإخضاع تمرد كبادوكيا.

حرب الديادوخي الأولى (322–320 ق.م.)

ولكن سرعان ما اندلعت الصراعات بين القادة. فقد أدى زواج بيرديكاس من كليوباترا شقيقة الإسكندر إلى قيام أنتيباتر و كراتيروس، أنتيغونوس، وبطليموس للتوحد في تمرد مشترك. فاندلعت الحرب الفعلية بسرقة بطليموس لجثمان الإسكندر، وتهريبه خفية إلى مصر. وعلى الرغم من هزيمة يومينيس للمتمردين في آسيا الصغرى، في معركة قُتل فيها كراتيروس، فإنها كانت خسارة كلية، إذ قتل برديكاس ذاته على يد قادته الخاصين بيثون و سلوقس و أنتيجينيسen خلال اجتياحهم مصر.

توافق بطليموس مع قتلة بيرديكاس، مما جعل بيثون و أرياديوس أوصياء على المنطقة، ولكن سرعان ما توصل هؤلاء إلى تفاهمات جديدة مع أنتيباتر في معاهدة تريپاراديسيوس. فجُعل فيها أنتيباتر وصياً على الإمبراطورية، ونُقل بموجبها الملكين إلى مقدونيا. وبقي أنتيغونوس مسؤولا عن فريجيا و ليكيا و بامفيليا، وأضيفت عليها ليكاونيا. واحتفظ بطليموس بمصر، و ليسيماخوس بتراقيا، بينما تم منح قتلة بيرديكاس الثلاثة: سلوقس و بيثون و أنتيجينيس أقاليم بابل و ميديا و سوسيانا على التوالي. وحصل أرياديوس، الوصي السابق، على فريجيا الهلسبونتية. وألقيت مهمة اجتثاث يومينيس، مؤيّد بيرديكاس على عاتق أنتيغوناس. وبهذ، احتفظ أنتيباتر لنفسه بالسيطرة على أوروبا، في حين احتل أنتيغوناس منصباً مماثلاً في آسيا، كونه زعيم أكبر جيش إلى شرق الدردنيل.

تقسيم تريپاراديسيوس

وفاة أنتيپاتور

بعد وقت قصير من القسمة الثانية، وفي عام 319 ق م، مات أنتيباتر بعد أن كان واحدا من القلة المتبقية الذي امتلكوا الهيبة والدراية الكافية لشد أوصال الامبراطورية معاً. وبعد وفاته، بدأت نذر تفتت الإمبراطورية تتضح بصورة أكثر جدية. فاندلعت الحرب مرة أخرى، بعد وفاته في عام 319 ق م. وكان أنتيباتر قد أعلن عن بوليبيرخون خلفاً له، مهملاً ابنه كاسندر. فاندلعت حرباً أهلية بعدها بقليل في مقدونيا واليونان بين بوليبيرخون و كاسندر، فأيّد الثاني كل من أنتيغوناس و بطليموس. وتحالف بوليبيرخون مع يومينيس في آسيا، ولكنه طُرد من مقدونيا على يد كاسندر، وهرب إلى إبايروس مع الملك الرضيع الإسكندر الرابع وأمه روكسانا . وفي إبايروس ضم قواته إلى قوات أوليمبياس والدة الإسكندر، فاحتلوا معا مقدونيا مرة أخرى. وفي انتظارهم كان هناك جيش بقيادة الملك فيليب أرياديوس وزوجته يوريديك اen، فانشق الجيش على الفور، تاركاً الملك و يوريديس تحت رحمة أوليمبياس التي لم تكن تعرف الرحمة، فقتلتهم (في عام 317 ق م). إلا أن الأمر انقلب عليها بعد فترة، وكان كاسندر هو من ظفر بالرئاسة، فاسر ثم قتل أوليمبياس، وأحكم سيطرته على مقدونيا، والملك الصبي وأمه.

حروب الديادوخي (319–275 ق.م.)

فترة الإپيگوني

ممالك الديادوخي (275–30 ق.م.)

التراجع والسقوط

كُتب لهذا التقسيم أن يستمر لقرن من الزمان، قبل أن تنهار الأسرة الأنتيغونية أخيرا خاضعة لروما، وإنهاك السلوقيين من قبل الفرثيين القادمين من جهة بلاد فارس، وقد أجبرهم الرومان على التخلي عن السيطرة في آسيا الصغرى. إلا أن جيب سلوقي متمثل في مملكة حكمت في سوريا حتى قضى عليها بومبي بشكل نهائي في عام 64 ق م. أما البطالمة فقد استمروا لفترة أطول في الإسكندرية كمملكة عميلة تابعة لروما. ثم أخيراً ألحقت مصر إلى روما في 30 ق م.

الاستخدامات التاريخية كلقب

أوليك

انظر أيضاً

الهوامش

- ^ http://www.islamweb.net/newlibrary/display_book.php?idfrom=82&idto=84&bk_no=126&ID=60 الإسم مأخوذ من ما أورده الكامل في التاريخ لابن الأثير عن خلفاء الإسكند، دار الكتاب العربي - سنة النشر: 1417هـ / 1997م ص60]

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 600.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "διάδοχος". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "διαδέχομαι". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "δέχομαι". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Frisk, Hjalmar (1960). "δέχομαι". Griechisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch (in الألمانية). Vol. I. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

- ^ Plutarch, Alexander, Section VI.

- ^ Plutarch, Alexander, Section IX.

- ^ Plutarch, Alexander, Section XI.

المصادر

- Austin, M. M. (1994). The Hellenistic world from Alexander to the Roman conquest: a selection of ancient sources in translation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boiy, Tom (2000). "Dating Methods During the Early Hellenistic Period" (PDF format). Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 52.

- Droysen, Johann Gustav (1836). Geschichte der Nachfolger Alexanders (in German). Hamburg: Friedrich Perthes.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Grote, George (1869). A History of Greece: from the Earliest Period to the Close of the Generation Contemporary with Alexander the Great. Vol. XI (New ed.). London: John Murray.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holm, Adolf (1898) [1894]. Clarke, Frederick (Translator) (ed.). The History of Greece from Its Commencement to the Close of the Independence of the Greek Nation (in English and translated from the German). Vol. IV: The Graeco-Macedonian age, the period of the kings and the leagues, from the death of Alexander down to the incorporation of the last Macedonian monarchy in the Roman Empire. London; New York: Macmillan.

{{cite book}}:|editor-first=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Shipley, Graham (2000). The Greek World After Alexander. Routledge History of the Ancient World. New York: Routledge.

- Walbank, F.W. (1984). "The Hellenistic World". The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. Volume VII. part I. Cambridge.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

وصلات خارجية

- Lendering, Jona. "Alexander's successors: the Diadochi". Livius.org.

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- صفحات تستخدم خطا زمنيا

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 errors: generic name

- CS1 errors: extra text: volume

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- ديادوخي

- نزاعات القرن الرابع ق.م.

- نزاعات القرن الثالث ق.م.

- حروب اليونان القديمة

- ألقاب يونانية قديمة

- الإسكندر الأكبر

- ملكية