اسطنبول

اسطنبول

İstanbul | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise from top: the Bosphorus Bridge connecting Europe and Asia; Maiden's Tower; a nostalgic tram on İstiklal Avenue; Levent business district; Galata Tower; Ortaköy Mosque in front of the Bosphorus Bridge; and Hagia Sophia. | |||||||||||||||||||

| الدولة | |||||||||||||||||||

| المنطقة | مرمرة | ||||||||||||||||||

| المحافظة | اسطنبول | ||||||||||||||||||

| تأسست | 667 ق.م. بإسم بيزنطيوم Byzantium | ||||||||||||||||||

| الحكم الروماني | 330 م أصبحت القسطنطينية Constantinople | ||||||||||||||||||

| الحكم العثماني | 1453 أصبح اسمها اسطنبول | ||||||||||||||||||

| Provincial seat[أ] | Cağaloğlu, Fatih | ||||||||||||||||||

| Districts | 39 | ||||||||||||||||||

| الحكومة | |||||||||||||||||||

| • النوع | Mayor–council government | ||||||||||||||||||

| • الكيان | Municipal Council of Istanbul | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Mayor | Ekrem İmamoğlu (CHP) | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Governor | Ali Yerlikaya | ||||||||||||||||||

| المساحة | |||||||||||||||||||

| • الحضر | 2٬576٫85 كم² (994٫93 ميل²) | ||||||||||||||||||

| • العمران | 5٬343٫22 كم² (2٬063٫03 ميل²) | ||||||||||||||||||

| أعلى منسوب | 537 m (1٬762 ft) | ||||||||||||||||||

| التعداد (31 December 2021)[4] | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Megacity Metropolitan municipality | 15٬840٬900 | ||||||||||||||||||

| • الترتيب | 1st in Turkey | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Urban | 15٬514٬128 | ||||||||||||||||||

| • الكثافة الحضرية | 6٬021/km2 (15٬590/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| • الكثافة العمرانية | 2٬965/km2 (7٬680/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| صفة المواطن | Istanbulite (تركية: İstanbullu) | ||||||||||||||||||

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+3 (TRT) | ||||||||||||||||||

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (EEST) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Postal code | 34000 to 34990 | ||||||||||||||||||

| مفتاح الهاتف | +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side) | ||||||||||||||||||

| لوحة السيارة | 34 | ||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (Nominal) | 2019[5] | ||||||||||||||||||

| - Total | US$ 237 billion | ||||||||||||||||||

| - Per capita | US$ 15,285 | ||||||||||||||||||

| HDI (2019) | 0.846[6] (very high) · 1st | ||||||||||||||||||

| GeoTLD | .ist, .istanbul | ||||||||||||||||||

| الموقع الإلكتروني | ibb www | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

إسطنبول ( İstanbul ؛ تركية: İstanbul [isˈtanbuɫ] (![]() استمع))، وكان اسمها في السابق القسطنطينية، هي أكبر مدن تركيا، وهي المركز الاقتصادي والثقافي والتاريخي. تمتد المدينة على جانبي مضيق البسفور، فتتواجد في قارتي أوروپا وآسيا، ويبلغ عدد سكانها 15 مليون نسمة، مشكلين 19% من تعداد تركيا.[4] اسطنبول هي أكبر المدن الأوروپية تعداداً،[ب] وهي الخامسة عشر بين أكبر مدن العالم.

استمع))، وكان اسمها في السابق القسطنطينية، هي أكبر مدن تركيا، وهي المركز الاقتصادي والثقافي والتاريخي. تمتد المدينة على جانبي مضيق البسفور، فتتواجد في قارتي أوروپا وآسيا، ويبلغ عدد سكانها 15 مليون نسمة، مشكلين 19% من تعداد تركيا.[4] اسطنبول هي أكبر المدن الأوروپية تعداداً،[ب] وهي الخامسة عشر بين أكبر مدن العالم.

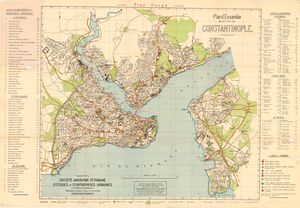

تأسست المدينة بإسم بيزنطيوم (Byzantion) في القرن السابع ق.م. على يد المستوطنين اليونانيين من مگارا.[7] وفي 330 م، جعلها الامبراطور الروماني قسطنطين الأكبر عاصمته الامبراطورية، مغيّراً اسمها، أولاً، إلى روما الجديدة (Nova Roma)[8] ثم إلى القسطنطينية (Constantinopolis) على اسمه.[8][9] نمت المدينة في الحجم والنفوذ، لتصبح مع مرور الموقت نبراساً على طريق الحرير وواحد من أهم المدن في التاريخ.

ظلت المدينة عاصمة امبراطورية لنحو 1600 سنة: أثناء الامبراطوريات الرومانية/البيزنطية (330–1204)، اللاتينية (1204–1261)، البيزنطية المتأخرة (1261–1453)، والعثمانية (1453–1922).[10] لعبت المدينة دوراً محورياً في نشر المسيحية في العصور الرومانية/البيزنطية، فاستضافت أربع (بما فيهم خلقيدونية (قاضيكوي) على الجانب الآسيوي) من المجامع المسكونية السبع الأولى (وكلهم كانوا في ما هو اليوم تركيا) قبل تحولها إلى معقل إسلامي إثر سقوط القسطنطينية في 1453 م—خصوصاً بعد أن أصبحت مقر الخلافة العثمانية في 1517.[11]

في 1923، بعد حرب الاستقلال التركية، حلت أنقرة محل المدينة كعاصمة للجمهورية التركية حديثة الإنشاء. وفي 1930، تغير اسم المدينة رسمياً إلى اسطنبول، وهي نطق المتكلمين باليونانية للاسم العثماني الرسمي "إسلامبول".[8]

جاء أكثر من 13.4 مليون زائر أجنبي إلى اسطنبول في عام 2018، بعد ثماني سنوات من تسميتها عاصمة الثقافة الأوروپية، مما يجعلها ثامن أكثر مدن العالم زيارةً.[12] تضم اسطنبول عدداً من مواقع التراث العالمي لليونسكو، وفيها المقار الرئيسية للعديد من الشركات التركية الكبرى، مما يجعل اقتصاد المدينة متجاوزاً ثلاثين بالمائة من اقتصاد تركيا.[13][14]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أصل الاسم

أول اسم معروف للمدينة هو بيزنطة (باليونانية: Βυζάντιον, Byzántion) الذي أطلقه عليها المستعمرون المـِگاران منذ تأسيسها حوالي 657 قبل الميلاد. [8][16] واعتبر المستعمرون المـِگارا أنفسهم أنهم ينتسبون إلى مؤسسي المدينة، بيزاس، ابن الإله بوسيدون والحورية سيرويسا.[16] ووجدت الحفريات الحديثة احتمال أن يعكس اسم بيزنطة مواقع المستوطنات التراقية الأصلية التي سبقت المدينة الكاملة.[17]واسم القسطنطينية مشتق من الاسم اللاتيني قسطنطينوس، نسبة إلى قسطنطين الأكبر، الإمبراطور الروماني الذي أعاد تأسيس المدينة عام 324 م.[16] فقد ظلت القسطنطينية الاسم الأكثر شيوعًا للمدينة في الغرب حتى الثلاثينيات، عندما بدأت السلطات التركية في الضغط من أجل استخدام "اسطنبول" باللغات الأجنبية. قسطنطينيه (تركية عثمانية: قسطنطينيه) وفي الفترة العثمانية استخدمت اسماء مقام قسطنطينيه المحمية واسطنبول بالتنواب [18]

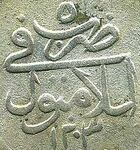

الاسم اسطنبول ( İstanbul ؛ النطق التركي: [isˈtanbuɫ] (![]() استمع), colloquially النطق التركي: [ɯsˈtambuɫ]) يُعتقد أنه مشتق من عبارة يونانية من العصور الوسطى "εἰς τὴν Πόλιν"، والتي تعني "إلى المدينة"[19] وهي هي الطريقة التي أشار بها اليونانيون المحليون إلى القسطنطينية. يعكس هذا وضعها باعتبارها المدينة الرئيسية الوحيدة في المنطقة المحيطة بهم. كما انعكست أهمية القسطنطينية في العالم العثماني من خلال لقبها العثماني "دير سعدت" بمعنى "بوابة الازدهار" باللغة التركية العثمانية.[20] رأي مخالف يعتبر أن الاسم نشأ مباشرة من اسم "القسطنطينية"، مع حذف المقطعين الأول والثالث.[16] وصفته بعض المصادر العثمانية في القرن السابع عشر، بأنه الاسم التركي الشائع في ذلك الوقت. وبين أواخر القرن السابع عشر وأواخر القرن الثامن عشر، كانت أيضًا قيد الاستخدام الرسمي. وكان أول استخدام لكلمة "إسلامبول" على العملات المعدنية كان عام 1730 في عهد السلطان محمود الأول.[21] في التركية المعاصرة، تتم كتابة الاسم كـ "İstanbul"، مع حرف İ منقط، حيث تميز الأبجدية التركية بين İ منقطة و I الغير منقطة. في حين باللغة الإنجليزية، يكون التركيز على المقطع الأول أو الأخير، ولكن في اللغة التركية يكون التركيز على المقطع الثاني.[22]وللنسب للمدينة يقال "اسطنبولي ؛ يتم استخدام "Istanbulite" في الإنگليزية.[23]

استمع), colloquially النطق التركي: [ɯsˈtambuɫ]) يُعتقد أنه مشتق من عبارة يونانية من العصور الوسطى "εἰς τὴν Πόλιν"، والتي تعني "إلى المدينة"[19] وهي هي الطريقة التي أشار بها اليونانيون المحليون إلى القسطنطينية. يعكس هذا وضعها باعتبارها المدينة الرئيسية الوحيدة في المنطقة المحيطة بهم. كما انعكست أهمية القسطنطينية في العالم العثماني من خلال لقبها العثماني "دير سعدت" بمعنى "بوابة الازدهار" باللغة التركية العثمانية.[20] رأي مخالف يعتبر أن الاسم نشأ مباشرة من اسم "القسطنطينية"، مع حذف المقطعين الأول والثالث.[16] وصفته بعض المصادر العثمانية في القرن السابع عشر، بأنه الاسم التركي الشائع في ذلك الوقت. وبين أواخر القرن السابع عشر وأواخر القرن الثامن عشر، كانت أيضًا قيد الاستخدام الرسمي. وكان أول استخدام لكلمة "إسلامبول" على العملات المعدنية كان عام 1730 في عهد السلطان محمود الأول.[21] في التركية المعاصرة، تتم كتابة الاسم كـ "İstanbul"، مع حرف İ منقط، حيث تميز الأبجدية التركية بين İ منقطة و I الغير منقطة. في حين باللغة الإنجليزية، يكون التركيز على المقطع الأول أو الأخير، ولكن في اللغة التركية يكون التركيز على المقطع الثاني.[22]وللنسب للمدينة يقال "اسطنبولي ؛ يتم استخدام "Istanbulite" في الإنگليزية.[23]

التاريخ

مقالة مفصلة: تاريخ اسطنبول

مقالة مفصلة: تاريخ اسطنبول

لقى العصر الحجري الحديث التي اكتشفها علماء الآثار في مطلع القرن 21، تبين أن شبه الجزيرة التاريخية لاسطنبول كانت مستوطنة لأزمنة تعود إلى الألفية السادسة ق.م..[24] هذا الاستيطان المبكر، الذي كان مهماً في انتشار ثورة العصر الحجري الحديث من الشرق الأدنى إلى أوروپا، استمر لنحو ألفية من الزمان قبل أن تغمره المياه المرتفعة.[25][24][26][27]

أول استيطان لمنطقة اسطنبول كان في تبة فقير تپه على الجانب الأناضولي، في العصر النحاسي، وقد عثر على مخلفات من تلك الحقبة تعود إلى 5500 - 3500 ق.م.،[28] وعلى الجانب الأوروپي، بالقرب من نقطة شبه الجزيرة (سرايبرنو)، كانت توجد مستوطنة تراقية في مطلع الألفية الأولى ق.م. وقد ربطها الكتاب الحاليون بالجذر التراقي ليگوس Lygos،[29] الذي ذكره پلني الأكبر كإسم أقدم لموقع بيزنطيوم.[30]

وهناك بقايا ميناء تعود إلى الفينيقيين في ضاحية قاضيكوي (خلقدون). رأس مودا في خلقدون كان أول موقع اختاره المستوطنون اليونانيون من مـِگارا Megara ليستعمروه عام 685 ق.م.، قبل أن يستعمروا بيزنطيون Byzantion على الجانب الاوروبي من البوسفور تحت إمرة الملك بيزاس Byzas في 667 ق.م.. تأسست بيزنطيون على موقع ميناء قديم اسمه ليگوس Lygos, الذي أسسته القبائل التراقية بين القرنين الثالث عشر والحادي عشر قبل الميلاد, أثناء تعميرهم سـِميسترا Semistra المجاورة,[31] التي ذكرها پليني الأكبر Pliny the Elder في سجلاته التاريخية. لم يبق من ليگوس، في يومنا هذا، إلا بعض الحوائط والمباني, بالقرب من نقطة سراليو (تركية: Sarayburnu), حيث يرتفع قصر طوپ قپو الآن. وأثناء عصر بيزنطيون, فقد كان هناك أكروپوليس محل قصر طوپ قپو الحالي.

بعد تحالفها ضد الامبراطور سپتيموس سڤروس تمت محاصرة المدينة وتدميرها بشكل كبير عام 196 م. ولكن سرعان ما تم إعادة بناء المدينة واستعادت حيوتها السابقة .

صعود وسقوط القسطنطينية والامبراطورية البيزنطية

Constantine the Great effectively became the emperor of the whole of the Roman Empire in September 324.[32] Two months later, he laid out the plans for a new, Christian city to replace Byzantium. As the eastern capital of the empire, the city was named Nova Roma; most called it Constantinople, a name that persisted into the 20th century.[33] On 11 May 330, Constantinople was proclaimed the capital of the Roman Empire, which was later permanently divided between the two sons of Theodosius I upon his death on 17 January 395, when the city became the capital of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.[34]

The establishment of Constantinople was one of Constantine's most lasting accomplishments, shifting Roman power eastward as the city became a center of Greek culture and Christianity.[34][35] Numerous churches were built across the city, including Hagia Sophia which was built during the reign of Justinian the Great and remained the world's largest cathedral for a thousand years.[36] Constantine also undertook a major renovation and expansion of the Hippodrome of Constantinople; accommodating tens of thousands of spectators, the hippodrome became central to civic life and, in the 5th and 6th centuries, the center of episodes of unrest, including the Nika riots.[37][38] Constantinople's location also ensured its existence would stand the test of time; for many centuries, its walls and seafront protected Europe against invaders from the east and the advance of Islam.[35] During most of the Middle Ages, the latter part of the Byzantine era, Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city on the European continent and at times the largest in the world.[39][40] Constantinople is generally considered to be the center and the "cradle of Orthodox Christian civilization".[41][42]

Constantinople began to decline continuously after the end of the reign of Basil II in 1025. The Fourth Crusade was diverted from its purpose in 1204, and the city was sacked and pillaged by the crusaders.[43] They established the Latin Empire in place of the Orthodox Byzantine Empire.[44] Hagia Sophia was converted to a Catholic church in 1204. The Byzantine Empire was restored, albeit weakened, in 1261.[45] Constantinople's churches, defenses, and basic services were in disrepair,[46] and its population had dwindled to a hundred thousand from half a million during the 8th century.[ت] After the reconquest of 1261, however, some of the city's monuments were restored, and some, like the two Deesis mosaics in Hagia Sofia and Kariye, were created.[47]

Various economic and military policies instituted by Andronikos II, such as the reduction of military forces, weakened the empire and left it vulnerable to attack.[48] In the mid-14th-century, the Ottoman Turks began a strategy of gradually taking smaller towns and cities, cutting off Constantinople's supply routes and strangling it slowly.[49] On 29 May 1453, after an eight-week siege (during which the last Roman emperor, Constantine XI, was killed), Sultan Mehmed II "the Conqueror" captured Constantinople and declared it the new capital of the Ottoman Empire. Hours later, the sultan rode to the Hagia Sophia and summoned an imam to proclaim the Islamic creed, converting the grand cathedral into an imperial mosque due to the city's refusal to surrender peacefully.[50] Mehmed declared himself as the new Kayser-i Rûm (the Ottoman Turkish equivalent of the Caesar of Rome) and the Ottoman state was reorganized into an empire.[51][52]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

عهدا الدولة العثمانية والجمهورية التركية

Following the conquest of Constantinople,[ث] Mehmed II immediately set out to revitalize the city. Cognizant that revitalization would fail without the repopulation of the city, Mehmed II welcomed everyone–foreigners, criminals, and runaways– showing extraordinary openness and willingness to incorporate outsiders that came to define Ottoman political culture.[54] He also invited people from all over Europe to his capital, creating a cosmopolitan society that persisted through much of the Ottoman period.[55] Revitalizing Istanbul also required a massive program of restorations, of everything from roads to aqueducts.[56] Like many monarchs before and since, Mehmed II transformed Istanbul's urban landscape with wholesale redevelopment of the city center.[57] There was a huge new palace to rival, if not overshadow, the old one, a new covered market (still standing as the Grand Bazaar), porticoes, pavilions, walkways, as well as more than a dozen new mosques.[56] Mehmed II turned the ramshackle old town into something that looked like an imperial capital.[57]

Social hierarchy was ignored by the rampant plague, which killed the rich and the poor alike in the 16th century.[58] Money could not protect the rich from all the discomforts and harsher sides of Istanbul.[58] Although the Sultan lived at a safe remove from the masses, and the wealthy and poor tended to live side by side, for the most part Istanbul was not zoned as modern cities are.[58] Opulent houses shared the same streets and districts with tiny hovels.[58] Those rich enough to have secluded country properties had a chance of escaping the periodic epidemics of sickness that blighted Istanbul.[58]

The Ottoman Dynasty claimed the status of caliphate in 1517, with Constantinople remaining the capital of this last caliphate for four centuries.[11] Suleiman the Magnificent's reign from 1520 to 1566 was a period of especially great artistic and architectural achievement; chief architect Mimar Sinan designed several iconic buildings in the city, while Ottoman arts of ceramics, stained glass, calligraphy, and miniature flourished.[59] The population of Constantinople was 570,000 by the end of the 18th century.[60]

A period of rebellion at the start of the 19th century led to the rise of the progressive Sultan Mahmud II and eventually to the Tanzimat period, which produced political reforms and allowed new technology to be introduced to the city.[61] Bridges across the Golden Horn were constructed during this period,[62] and Constantinople was connected to the rest of the European railway network in the 1880s.[63] Modern facilities, such as a water supply network, electricity, telephones, and trams, were gradually introduced to Constantinople over the following decades, although later than to other European cities.[64] The modernization efforts were not enough to forestall the decline of the Ottoman Empire.[65]

Sultan Abdul Hamid II was deposed with the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and the Ottoman Parliament, closed since 14 February 1878, was reopened 30 years later on 23 July 1908, which marked the beginning of the Second Constitutional Era.[66] A series of wars in the early 20th century, such as the Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912) and the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), plagued the ailing empire's capital and resulted in the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état, which brought the regime of the Three Pashas.[67]

The Ottoman Empire joined World War I (1914–1918) on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated. The deportation of Armenian intellectuals on 24 April 1915 was among the major events which marked the start of the Armenian genocide during WWI.[69] Due to Ottoman and Turkish policies of Turkification and ethnic cleansing, the city's Christian population declined from 450,000 to 240,000 between 1914 and 1927.[70] The Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October 1918 and the Allies occupied Constantinople on 13 November 1918. The Ottoman Parliament was dissolved by the Allies on 11 April 1920 and the Ottoman delegation led by Damat Ferid Pasha was forced to sign the Treaty of Sèvres on 10 August 1920.[بحاجة لمصدر]

وبعد حرب الاستقلال التركية (1919–1922), the Grand National Assembly of Turkey in Ankara abolished the Sultanate on 1 November 1922, and the last Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed VI, was declared persona non grata. Leaving aboard the British warship HMS Malaya on 17 November 1922, he went into exile and died in Sanremo, Italy, on 16 May 1926. The Treaty of Lausanne was signed on 24 July 1923, and the occupation of Constantinople ended with the departure of the last forces of the Allies from the city on 4 October 1923.[71] Turkish forces of the Ankara government, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha (3rd Corps), entered the city with a ceremony on 6 October 1923, which has been marked as the Liberation Day of Istanbul (Turkish: İstanbul'un Kurtuluşu) and is commemorated every year on its anniversary.[71] On 29 October 1923 the Grand National Assembly of Turkey declared the establishment of the Turkish Republic, with Ankara as its capital. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk became the Republic's first President.[72][73] According to historian Philip Mansel:

- after the departure of the dynasty in 1925, from being the most international city in Europe, Constantinople became one of the most nationalistic....Unlike Vienna, Constantinople turned its back on the past. Even its name was changed. Constantinople was dropped because of its Ottoman and international associations. From 1926 the post office only accepted Istanbul; it appeared more Turkish and was used by most Turks.[74][صفحة مطلوبة]

A 1942 wealth tax assessed mainly on non-Muslims led to the transfer or liquidation of many businesses owned by religious minorities.[75] From the late 1940s and early 1950s, Istanbul underwent great structural change, as new public squares, boulevards, and avenues were constructed throughout the city, sometimes at the expense of historical buildings.[76] The population of Istanbul began to rapidly increase in the 1970s, as people from Anatolia migrated to the city to find employment in the many new factories that were built on the outskirts of the sprawling metropolis. This sudden, sharp rise in the city's population caused a large demand for housing, and many previously outlying villages and forests became engulfed into the metropolitan area of Istanbul.[77]

إن موقعها الاستراتيجي كنقطة عبور بين قارتين جعلها تلعب دورا هاما في العديد من المجالات السياسية والثقافية والتجارية بين أسيا وأوروبا وشمال افريقية وخاصة بين المتوسط والبحر الأسود. ولطالما بقيت المركز الرئيسي للإمبراطورية الأرثوذوكسية البيزنطية وأكبر مدينة أوروبية حتى تم الاستيلاء عليها من خلال الحملة الصليبية الرابعة 1204 ولكنها فشلت في الابقاء تحت قبضتها فأعاد احتلالها مايكل الثامن بقوات نيكايين في 1261 م.

حاصر المسلمون العثمانيون مدينة القسطنطينية حوالي 7 أسابيع في نيسان/أبريل 1453 بقيادة السلطان الشاب محمد الثاني ذو 21 ربيعا، الذي عرف لاحقا تحت اسم محمد الفاتح، إلى أن تمكنوا من فتحها في 27 مايو 1453 وتغيير اسمها إلى "إسطنبول" وجعلها عاصمة للإمبراطورية العثمانية. ينحدر اسم المدينة الحالي من بلدة "ستامبول"، التي كانت تشكل مركز إسطنبول يوما ما. ستامبول هو مصطلح منحدر من اليونانية ومعناه "إلى المدينة" (is tin polin). قام العثمانيون بتحويل معظم كنائس المدينة إلى مساجد، أهمها كانت كاتدرائية آيا صوفيا.

كان ذلك أحد ردود الفعل على سقوط الأندلس وطرد المسلمين واليهود منها وهدم وتحويل مساجدها. استلهم العثمانييون من الكنائس البيزنطية طريقة بناء خاصة ومميزة لجوامعهم وأضافوا عليها المنارات وزينوها من الداخل بالزخارف الاسلامية. تم بناء العديد من الجوامع المذهلة حول المدينة و كان كل سلطان يحاول التفنن بهذه الجوامع كإحياء لعهده ومن بين أهم المساجد في المدينة المسجد الكبير في اسطنبول جامع بايزيد وجامع السلطان أحمد وجامع الفاتح وجامع سليم. أمهات وزوجات السلاطين كان لهم دور كبير في بناء العديد من الجوامع في المدينة.

بعد قيام الجمهورية التركية في عام 1923 نقل مكان العاصمة إلى أنقرة وضعف الاهتمام باسطنبول وخلال الخمسينيات هاجر العديد من الجاليات الرومانية إلى اليونان وانخفضت أيضا وبشكل كبير الجاليات الأرمنية واليهودية نتيجة الهجرة الكثيفة. في عام 1960 أرادت حكومة عدنان مندريس تطوير البلاد وقامت بشق الشوارع العريضة وسط المدينة والتي تسببت في خراب العديد من الأبنية التاريخية وشوهت منظر المدينة القديمة كما قامت ببناء العديد من المصانع على أطراف المدينة والتي حفزت بالسبعينات أهل الأناضول على الهجرة للعمل في هذه المصانع والعيش بالمدينة وأدى ذلك إلى ارتفاع هائل وتضخم حاد مما دفع إلى بناء العديد من الأبنية وغالبها من النوعية الرديئة أدى إلى انهيارها بسبب الزلالزل التي ضربت المدينة.

ميدان تقسيم، أحد ميادين إسطنبول المكتظة |

جامع السلطان أحمد، الذي يعرف أيضا تحت اسم الجامع الأزرق |

صورة تمثل فتح القسطنطينية بيد العثمانيين |

آيا صوفيا، الكاتدرائية السابقة والجامع السابق، اليوم هي عبارة عن متحف |

| “ | لو العالم أصبح دولة واحدة، فإسطنبول ستصبح عاصمته. | ” |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الجغرافيا

صورة ساتلية لاسطنبول والبوسفور |

الموقع

تبلغ مساحة المدينة الرسمية حوالي 1,538.77 كم2، بينما تبلغ مساحة مديرية إسطنبول حوالي 5,220 كم2.

الجيولوجيا

اسطنبول مبنية قرب صدع الأناضول الشمالي وهو مسؤول عن العديد من الزلالزل المدمرة خلال التاريخ والعديد من الدراسات تشير إلى احتمال حدوث زلازل مدمرة خلال العقدين القادمين وقربها من بحر مرمرة يزيد الاحتمال من خطر نشوء تسونامي والذي قد يتسبب بخسائر بشرية فادحة خصوصا في الأبنية السيئة البناء المنتشرة في اسطنبول.

إلا أن بعض الخبراء لا يرجحون نظرية التسونامي و ذلك لأن بحر مرمرة يعتبر صغير مقارنة بالبحار الأخرى.

المناخ

مناخ اسطنبول يحتوي على صيف طويل وحار وشتاء بارد وأمطار غزيرة. نسبة الرطوبة ثابتة وعالية تجعل من الجو أقسى مما هو عليه. درجات الحرارة في الشتاء تتراوح بين 3 إلى 8 درجات ودرجات الحرارة الصباحية في الصيف تكون حوالي 28° م. على الرغم من أن الصيف شهر جفاف إلا أنه من الممكن نشوء رياح موسمية وأمطار تسبب فيضانات.

| متوسطات الطقس لاسطنبول | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| شهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | اكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | السنة |

| متوسط العظمى °م | 8 | 8 | 11 | 16 | 21 | 26 | 28 | 28 | 24 | 19 | 14 | 10 | 18 |

| متوسط الصغرى °م | 3 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 17 | 19 | 19 | 16 | 13 | 8 | 6 | 11 |

| هطول الأمطار mm | 94 | 71.1 | 58.4 | 43.2 | 30.5 | 22.9 | 17.8 | 15.2 | 27.9 | 53.3 | 88.9 | 101.6 | 640٫1 |

| متوسط العظمى °ف | 46 | 47 | 51 | 60 | 69 | 78 | 82 | 82 | 76 | 67 | 57 | 50 | 64 |

| متوسط الصغرى °ف | 37 | 37 | 40 | 47 | 54 | 62 | 66 | 67 | 61 | 55 | 47 | 42 | 51 |

| Precipitation inch | 3.7 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 25٫2 |

| المصدر: Weatherbase[80] في 4 يناير 2008 | |||||||||||||

منظر المدينة

الآثار اليونانية والرومانية القديمة

الآثار البيزنطية

الخندق المائي[81][82] الذي كان يحيط بالأسوار الأرضية الثلاثية للقسطنطينية ولاحقاً مـُلِئ بالتراب واستخدم في الزراعة |

الآثار العثمانية

العمران

جادة بغداد، الذي يبلغ طوله 6 كم في الجانب الأناضولي، فيه صفوف من المحال والمقاهي والحانات والمطاعم تصطف على جانبي الطريق الواسع المرصوف بالگرانيت |

السكان

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المصادر: Jan Lahmeyer 2004,Chandler 1987, Morris 2010,Turan 2010[83] Pre-Republic figures estimated[ت] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Throughout most of its history, Istanbul has ranked among the largest cities in the world. By 500 CE, Constantinople had somewhere between 400,000 and 500,000 people, edging out its predecessor, Rome, for the world's largest city.[85] Constantinople jostled with other major historical cities, such as Baghdad, Chang'an, Kaifeng and Merv for the position of the world's largest city until the 12th century. It never returned to being the world's largest, but remained the largest city in Europe from 1500 to 1750, when it was surpassed by London.[86]

The Turkish Statistical Institute estimates that the population of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality was 15,519,267 at the end of 2019, hosting 19 percent of the country's population.[87] 64.4% of the residents live on the European side and 35.6% on the Asian side.[87]

Istanbul ranks as the seventh-largest city proper in the world, and the second-largest urban agglomeration in Europe, after Moscow.[88][89] The city's annual population growth of 1.5 percent ranks as one of the highest among the seventy-eight largest metropolises in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The high population growth mirrors an urbanization trend across the country, as the second and third fastest-growing OECD metropolises are the Turkish cities of Izmir and Ankara.[14]

Istanbul experienced especially rapid growth during the second half of the 20th century, with its population increasing tenfold between 1950 and 2000.[90] This growth was fueled by internal and international migration. Istanbul's foreign population with a residence permit increased dramatically, from 43,000 in 2007[91] to 856,377 in 2019.[92][93]

According to 2020 TÜİK data around 2.1 million people in a population of over 15.4 million have been registered[ج] in Istanbul, meanwhile the vast majority of the residents ultimately originate from Anatolian provinces, especially those in the Black Sea, Central and Eastern Anatolia regions due to internal migration since the 1950s.[94] People registered in Kastamonu, Ordu, Giresun, Erzurum, Samsun, Malatya, Trabzon, Sinop and Rize provinces represent the biggest population groups in Istanbul, meanwhile people registered in Sivas has the highest percentage with more than 760 thousand residents in the city.[95] A 2019 survey found that only 36% of the Istanbul's population was born in the province.[96]

Ethnic and religious groups

Istanbul has been a cosmopolitan city throughout much of its history, but it has become more homogenized since the end of the Ottoman era. The dominant ethnic group in the city is Turkish people, which also forms the majority group in Turkey. According to survey data 78% of the voting-age Turkish citizens in Istanbul state "Turkish" as their ethnic identity.[96]

With estimates ranging from 2 to 4 million, Kurds form one of the largest ethnic minorities in Istanbul and are the biggest group after Turks among Turkish citizens.[97][98] According to a 2019 KONDA study, Kurds constituted around 17% of Istanbul's adult total population who were Turkish citizens.[96] Although the Kurdish presence in the city dates back to the early Ottoman period,[99] the majority of Kurds in the city originate from villages in eastern and southeastern Turkey.[100] Zazas are also present in the city and constitute around 1% of the total voting-age population.[96]

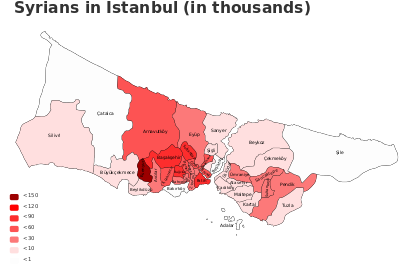

Arabs form the city's other largest ethnic minority, with an estimated population of more than 2 million.[101] Following Turkey's support for the Arab Spring, Istanbul emerged as a hub for dissidents from across the Arab world, including former presidential candidates from Egypt, Kuwaiti MPs, and former ministers from Jordan, Saudi Arabia (including Jamal Khashoggi), Syria, and Yemen.[102][103][104] The number of refugees of the Syrian Civil War in Turkey residing in Istanbul is estimated to be around 1 million.[105] Native Arab population in Turkey who are Turkish citizens are found to be making up less than 1% of city's total adult population.[96]

2019 survey study by KONDA that examined the religiosity of the voting-age adults in Istanbul showed that 57% of the surveyed had a religion and were trying to practise its requirements. This was followed by nonobservant people with 26% who identified with a religion but generally did not practise its requirements. 11% stated they were fully devoted to their religion, meanwhile 6% were non-believers who did not believe the rules and requirements of a religion. 24% of the surveyed also identified themselves as "religious conservatives". Around 90% of Istanbul's population are Sunni Muslims and Alevism forms the second biggest religious group.[96][106]

Into the 19th century, the Christians of Istanbul tended to be either Greek Orthodox, members of the Armenian Apostolic Church or Catholic Levantines.[108] Greeks and Armenians form the largest Christian population in the city. While Istanbul's Greek population was exempted from the 1923 population exchange with Greece, changes in tax status and the 1955 anti-Greek pogrom prompted thousands to leave.[109] Following Greek migration to the city for work in the 2010s, the Greek population rose to nearly 3,000 in 2019, still greatly diminished since 1919, when it stood at 350,000.[109] There are today 123,363 Armenians in Istanbul, down from a peak of 164,000 in 1913.[110] As of 2019, an estimated 18,000 of the country's 25,000 Christian Assyrians live in Istanbul.[111]

The majority of the Catholic Levantines (Turkish: Levanten) in Istanbul and Izmir are the descendants of traders/colonists from the Italian maritime republics of the Mediterranean (especially Genoa and Venice) and France, who obtained special rights and privileges called the Capitulations from the Ottoman sultans in the 16th century.[113] The community had more than 15,000 members during Atatürk's presidency in the 1920s and 1930s, but today is reduced to only a few hundreds, according to Italo-Levantine writer Giovanni Scognamillo.[114] They continue to live in Istanbul (mostly in Karaköy, Beyoğlu and Nişantaşı), and Izmir (mostly in Karşıyaka, Bornova and Buca).

Istanbul became one of the world's most important Jewish centers in the 16th and 17th century.[115] Romaniote and Ashkenazi communities existed in Istanbul before the conquest of Istanbul, but it was the arrival of Sephardic Jews that ushered a period of cultural flourishing. Sephardic Jews settled in the city after their expulsion from Spain and Portugal in 1492 and 1497.[115] Sympathetic to the plight of Sephardic Jews, Bayezid II sent out the Ottoman Navy under the command of admiral Kemal Reis to Spain in 1492 in order to evacuate them safely to Ottoman lands.[115] In marked contrast to Jews in Europe, Ottoman Jews were allowed to work in any profession.[116] Ottoman Jews in Istanbul excelled in commerce, and came to particularly dominate the medical profession.[116] By 1711, using the printing press, books came to be published in Spanish and Ladino, Yiddish, and Hebrew.[117] In large part due to emigration to Israel, the Jewish population in the city dropped from 100,000 in 1950[118] to 25,000 in 2020.

كنيسة خورا, التي هي الآن متحف, تشتهر بفسيفسائها ورسومها الجصية fresco البيزنطية المتواجدة في حالة جيدة جداً من الفترة الپالايولوگية | ||

مسجد عرپ, بـُنـِيَ في الأصل ككنيسة دومينيكانية للقديس پولس في 1233, هو واحد من أهم المباني المتبقة من الامبراطورية اللاتينية |

||

الاقتصاد

مقالة مفصلة: اقتصاد إسطنبول

مقالة مفصلة: اقتصاد إسطنبول

Istanbul had the eleventh-largest economy among the world's urban areas in 2018, and is responsible for 30 percent of Turkey's industrial output,[121] 31 percent of GDP,[121] and 47 percent of tax revenues.[121] The city's gross domestic product adjusted by PPP stood at US$537.507 billion in 2018,[122] with manufacturing and services accounting for 36 percent and 60 percent of the economic output respectively.[121] Istanbul's productivity is 110 percent higher than the national average.[121] Trade is economically important, accounting for 30 percent of the economic output in the city.[13] In 2019, companies based in Istanbul produced exports worth $83.66 billion and received imports totaling $128.34 billion; these figures were equivalent to 47 percent and 61 percent, respectively, of the national totals.[123]

Istanbul, which straddles the Bosporus strait, houses international ports that link Europe and Asia. The Bosporus, providing the only passage from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, is the world's busiest and narrowest strait used for international navigation, with more than 200 million tons of oil passing through it each year.[124] International conventions guarantee passage between the Black and the Mediterranean seas,[125] even when tankers carry oil, LNG/LPG, chemicals, and other flammable or explosive materials as cargo. In 2011, as a workaround solution, the then Prime Minister Erdoğan presented Canal Istanbul, a project to open a new strait between the Black and Marmara seas.[125] While the project was still on Turkey's agenda in 2020, there has not been a clear date set for it.[13]

Shipping is a significant part of the city's economy, with 73.9 percent of exports and 92.7 percent of imports in 2018 executed by sea.[13] Istanbul has three major shipping ports – the Port of Haydarpaşa, the Port of Ambarlı, and the Port of Zeytinburnu – as well as several smaller ports and oil terminals along the Bosporus and the Sea of Marmara.[13]

Haydarpaşa, at the southeastern end of the Bosporus, was Istanbul's largest port until the early 2000s.[126] Since then operations were shifted to Ambarlı, with plans to convert Haydarpaşa into a tourism complex.[13] In 2019, Ambarlı, on the western edge of the urban center, had an annual capacity of 3,104,882 TEUs, making it the third-largest cargo terminal in the Mediterranean basin.[126]

Istanbul has been an international banking hub since the 1980s,[13] and is home to the only active stock exchange in Turkey, Borsa Istanbul, which was originally established as the Ottoman Stock Exchange in 1866.[127]

In 1995, keeping up with the financial trends, Borsa Istanbul moved its headquarters (which was originally located on Bankalar Caddesi, the financial center of the Ottoman Empire,[127] and later at the 4th Vakıf Han building in Sirkeci) to İstinye, in the vicinity of Maslak, which hosts the headquarters of numerous Turkish banks.[128]

By 2023, the Ataşehir district on the Asian side of the city will host the new headquarters of a number of state-owned Turkish banks, including the Central Bank of Turkey, currently headquartered in Ankara.[129][130]

13.4 million foreign tourists visited the city in 2018, making Istanbul the world's fifth most-visited city in that year.[12] Istanbul and Antalya are Turkey's two largest international gateways, receiving a quarter of the nation's foreign tourists.

Istanbul has more than fifty museums, with the Topkapı Palace, the most visited museum in the city, bringing in more than $30 million in revenue each year.[13]

السياحة

تعتبر مدينةاسطنبول قبلة السياحة في تركيا ومحط رحال كل من يزور البلاد وذلك لاحتوائها على معالم تاريخية ومناطق سياحية كثيرة ومن اشهرها منطقة السلطان احمد، تقسيم، اورتاكوي، امينونو وغيرها

المرافق

النقل

السكك الحديدية

الطرق

بالبحر

النقل العام

نظام تونـِل Tünel (بـُني 1875) هو ثاني أقدم خط مترو تحت الأرض في العالم بعد مترو لندن

محطة سيركجي افتـُتـِحت في 1890 بصفتها المحطة النهائية لقطار الشرق السريع

محطة حيدر پاشا افتـُتحت في 1908 بصفتها المحطة النهائية لخطوط اسطنبول-بغداد واسطنبول-المدينة المنورة

وصلة المترو بين كعبة طاش و ميدان تقسيم

الحياة في المدينة

الثقافة والفنون

الإعلام

الترفيه

التسوق

| “ | إذا كان على المرء أن يـُلقي نظرة واحدة على العالم, فعليه أن يحملق في اسطنبول. | ” |

الحانات والمقاهي والمطاعم

مقاهي إتيلر |

التعليم

بوابة المدخل الرئيسي لجامعة اسطنبول في ميدان بايزيد, الذي كان يـُعرف باسم "Forum Tauri" في عهد الرومان. برج بايزيد, الواقع داخل الحرم الجامعي, يظهر في الخلفية. |

الجامعات

مدارس ثانوية

الرياضة

| النادي | الرياضة | تأسس | الدوري | الملكعب |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| بشيكتاش JK | كرة قدم | 1903 | Turkcell Super League | استاد إينونو |

| غلطة سراي SK | Football | 1905 | Turkcell Super League | Ali Sami Yen Stadium |

| فنار بهچه SK | Football | 1907 | Turkcell Super League | Şükrü Saracoğlu Stadium |

| Istanbulspor AS | Football | 1926 | Turkish 2nd Division | Güngören Stadium |

| بشيكتاش كولا توركا | كرة سلة | 1903 | Turkish Basketball League | BJK Akatlar Arena |

| Galatasaray Cafe Crown | كرة سلة | 1905 | Turkish Basketball League | Ahmet Cömert Sports Hall |

| Fenerbahçe Ülkerspor | كرة سلة | 1907 | Turkish Basketball League | Abdi İpekçi Arena |

| Beykoz 1908 | كرة سلة | 1908 | Turkish Basketball League | R. Şahin Köktürk Sports Hall |

| Darüşşafaka S.K. | كرة سلة | 1914 | Turkish Basketball League | Ayhan Şahenk Sports Hall |

| Tekelspor | كرة سلة | 1941 | Turkish Basketball League | صالة رياضات خلدون الاگاش |

| Efes Pilsen S.K. | كرة سلة | 1976 | Turkish Basketball League | Abdi İpekçi Arena |

| Alpella | كرة سلة | 2006 | Turkish Basketball League | Caferağa Sports Hall |

| Eczacıbaşı | كرة الڤولي | 1977 | Turkish Women's Volleyball League | Eczacıbaşı Sports Hall |

| Vakıfbank Güneş Sigorta | كرة الڤولي | 1986 | Turkish Women's Volleyball League | صالة رياضات خلدون الاگاش |

مدن شقيقة

وصلات خارجية

- بلدية إسطنبول

- خريطة تفاعلية لاسطنبول

- صور من المدينة

- موقع عن إسطنبول بالتركية

- السياحة في اسطنبول

- إسطنبول

المصادر

- ^ "YETKİ ALANI". Istanbul Buyuksehir Belediyesi. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ İstanbul Province = 5,460.85 km²

Land area = 5,343.22 km²

Lake/Dam = 117.63 km²

Europe (25 districts) = 3,474.35 km²

Asia (14 districts) = 1,868.87 km²

Urban (36 districts) = 2,576.85 km² [Metro (39 districts) – (Çatalca+Silivri+Şile)]

* According to the size of the population and the status of megacity, the limits of the Istanbul city correspond to the limits of the province, and the province is treated like as the metropolitan-city of Istanbul. - ^ "İstanbul'un En Yüksek Tepeleri". Hava Forumu. Hava Durumu Forumu. 15 April 2020.

- ^ أ ب "The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2021". Turkish Statistical Institute. 31 December 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Kişi başına GSYH ($) (2019)". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org.

- ^ Judith Herrin (28 September 2009). Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire. Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-691-14369-9. OCLC 1091569907.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Istanbul". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ قالب:ODB

- ^ Çelik 1993, p. xv.

- ^ أ ب Masters & Ágoston 2009, pp. 114–15

- ^ أ ب "Top city destinations by overnight visitors". Statista. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Heper, Metin (2018). "Istanbul". Historical dictionary of Turkey (4th ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-0224-4.

- ^ أ ب OECD Territorial Reviews: Istanbul, Turkey. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. March 2008. ISBN 978-92-64-04383-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ أ ب "Forum of Constantine". www.byzantium1200.com. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Room 2006, p. 177

- ^ Georgacas 1947, p. 352ff.

- ^ Necipoğlu 2010, p. 262.

- ^ Necdet Sakaoğlu (1993/94a): "İstanbul'un adları" ["The names of Istanbul"]. In: Dünden bugüne İstanbul ansiklopedisi, ed. Türkiye Kültür Bakanlığı, Istanbul.

- ^ Grosvenor, Edwin Augustus (1895). Constantinople. Vol. 1. Roberts Brothers. p. 69. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Finkel 2005, pp. 57, 383.

- ^ Göksel & Kerslake 2005, p. 27.

- ^ Keyder 1999, p. 95.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBBC-Rainsford-2009 - ^ Algan, O.; Yalçın, M.N.K.; Özdoğan, M.; Yılmaz, Y.C.; Sarı, E.; Kırcı-Elmas, E.; Yılmaz, İ.; Bulkan, Ö.; Ongan, D.; Gazioğlu, C.; Nazik, A.; Polat, M.A.; Meriç, E. (2011). "Holocene coastal change in the ancient harbor of Yenikapı–İstanbul and its impact on cultural history". Quaternary Research. 76 (1): 30. Bibcode:2011QuRes..76...30A. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2011.04.002. S2CID 129280217.

- ^ "Bu keşif tarihi değiştirir". hurriyet.com.tr.

- ^ "Marmaray kazılarında tarih gün ışığına çıktı". fotogaleri.hurriyet.com.tr.

- ^ "Cultural Details of Istanbul". Republic of Turkey, Minister of Culture and Tourism. Archived from the original on 12 September 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ^ Janin, Raymond (1964). Constantinople byzantine. Paris: Institut Français d'Études Byzantines. pp. 10ff.

- ^

"Pliny the Elder, book IV, chapter XI:

"On leaving the Dardanelles we come to the Bay of Casthenes, ... and the promontory of the Golden Horn, on which is the town of Byzantium, a free state, formerly called Lygos; it is 711 miles from Durazzo, ..."". Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2015. - ^ Vailhé, S. (1908). "Constantinople". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 77

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 212

- ^ أ ب Barnes 1981, p. 222

- ^ أ ب Gregory 2010, p. 63

- ^ Klimczuk & Warner 2009, p. 171

- ^ Dash, Mike (2 March 2012). "Blue Versus Green: Rocking the Byzantine Empire". Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Dahmus 1995, p. 117

- ^ Cantor 1994, p. 226

- ^ Morris 2010, pp. 109–18

- ^ Parry, Ken (2009). Christianity: Religions of the Wold. Infobase Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 9781438106397.

- ^ Parry, Ken (2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 368. ISBN 9781444333619.

- ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 324–29.

- ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 330–333.

- ^ Gregory 2010, p. 340.

- ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 341–342.

- ^ "Deesis Mosaic". Hagia Sophia. 5 November 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Reinert 2002, pp. 258–260.

- ^ Baynes 1949, p. 47.

- ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 394–399.

- ^ Béhar 1999, p. 38.

- ^ Bideleux & Jeffries 1998, p. 71.

- ^ Edhem, Eldem. "Istanbul." In: Ágoston, Gábor and Bruce Alan Masters. Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing, 21 May 2010. ISBN 1-4381-1025-1, ISBN 9781438110257. Start and CITED: p. 286. "Originally, the name Istanbul referred only to[...]in the 18th century." and "For the duration of Ottoman rule, western sources continued to refer to the city as Constantinople, reserving the name Stamboul for the walled city." and "Today the use of the name[...]is often deemed politically incorrect[...]by most Turks." // (entry ends, with author named, on p. 290)

- ^ Inalcik, Halil. "The Policy of Mehmed II toward the Greek Population of Istanbul and the Byzantine Buildings of the City." Dumbarton Oaks Papers 23, (1969): 229–49. p. 236

- ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, pp. 306–07

- ^ أ ب Hughes, Bettany (2018). Istanbul: A Tale of Three Cities. London. ISBN 978-1-78022-473-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ أ ب Madden, Thomas F. (7 November 2017). Istanbul: City of Majesty at the Crossroads of the World. New York. ISBN 978-0-14-312969-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2012). Encyclopedia of the Black Death. Santa Barbara, CA. ISBN 978-1-59884-253-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, pp. 735–36

- ^ أ ب Chandler, Tertius; Fox, Gerald (1974). 3000 Years of Urban Growth. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-785109-9.

- ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977, pp. 4–6, 55

- ^ Çelik 1993, pp. 87–89

- ^ Harter 2005, p. 251

- ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977, pp. 230, 287, 306

- ^ Çelik, Zeynep (1986). The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley. Los Angeles. London: University of California Press. p. 37.

- ^ "Meclis-i Mebusan (Mebuslar Meclisi)". Tarihi Olaylar.

- ^ Çelik 1993, p. 31

- ^ "Milestones in Borsa Istanbul History". www.borsaistanbul.com. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Freedman, Jeri (2009). The Armenian genocide (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Pub. Group. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-4042-1825-3.

- ^ Globalization, Cosmopolitanism, and the Dönme in Ottoman Salonica and Turkish Istanbul. Marc Baer, University of California, Irvine.

- ^ أ ب "6 Ekim İstanbul'un Kurtuluşu". Sözcü. 6 October 2017.

- ^ Landau 1984, p. 50

- ^ Dumper & Stanley 2007, p. 39

- ^ Philip Mansel. Constantinople: City of the World's Desire, 1453–1924 (2011)

- ^ Ağır, Seven; Artunç, Cihan (2019). "The Wealth Tax of 1942 and the Disappearance of Non-Muslim Enterprises in Turkey". The Journal of Economic History. 79 (1): 201–243. doi:10.1017/S0022050718000724. S2CID 159425371.

- ^ Keyder 1999, pp. 11–12, 34–36

- ^ Efe & Cürebal 2011, pp. 718–719

- ^ Byzantium 1200: دير القديس جورج من مانگانا

- ^ "5th World Congress Of The International Economic Association" (pdf). Retrieved 2007-09-12.]

- ^ "Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information from".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Byzantium 1200: Land Walls

- ^ Byzantium 1200: Porta Aurea

- ^ "Population of Istanbul in Turkey from 2007 to 2019". Statista.

- ^ "Address Based Population Registration System Results of 2010" (doc). Turkish Statistical Institute. 28 January 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 113

- ^ Chandler 1987, pp. 463–505

- ^ أ ب "The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2019". data.tuik.gov.tr. Istanbul, Turkey: Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. 4 February 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". World Urbanization Prospects, the 2011 Revision. The United Nations. 5 April 2012. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ "File 11a: The 30 Largest Urban Agglomerations Ranked by Population Size at Each Point in Time, 1950–2035" (xls). World Urbanization Prospects, the 2018 Revision. The United Nations. 5 April 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ Turan 2010, p. 224

- ^ Kamp, Kristina (17 February 2010). "Starting Up in Turkey: Expats Getting Organized". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "International Migration Statistics, 2019". data.tuik.gov.tr. Istanbul, Turkey: Türk İstatistik Kurumu. 17 July 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ Peace, Fergus (29 November 2020). "City stats: Istanbul versus Athens". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ Murat, Sedat. "Doğum yerlerine göre İstanbul nüfusu ve iç göçler".

- ^ Şafak, Yeni (2021-02-11). "İstanbul'da en çok nereli var: İstanbul'da en çok hangi ilden vatandaş yaşıyor?". Yeni Şafak (in التركية). Retrieved 2021-09-22.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "23 Haziran 2019 Sandık Analizi ve Seçmen Kümeleri" (PDF). KONDA.

- ^ Mustafa Mohamed Karadaghi (1995). Handbook of Kurdish Human Rights Watch, Inc: A Non-profit Humanitarian Organization. UN.

- ^ Tirman, John (1997). Spoils of War: The Human Cost of America's Arms Trade. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-684-82726-1.

- ^ Masters & Ágoston 2009, pp. 520–21

- ^ Baser, Bahar; Toivanen, Mari; Zorlu, Begum; Duman, Yasin (6 November 2018). Methodological Approaches in Kurdish Studies: Theoretical and Practical Insights from the Field. Lexington Books. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4985-7522-5.

- ^ McKernan, Bethan (18 April 2020). "How Istanbul won back its crown as heart of the Muslim world". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ Lepeska, David (27 December 2013). "Istanbul: An Unlikely Refuge for Exiled Journalists". The Atlantic. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ Hubbard, Ben (14 April 2019). "Arab Exiles Sound Off Freely in Istanbul Even as Turkey Muffles Its Own Critics". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ "Why dissidents are gathering in Istanbul". The Economist. 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ "Syrian migrants in Turkey face deadline to leave Istanbul". BBC News. 2019-08-20. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- ^ "Sözlük". Konda İnteraktif. Retrieved 2021-09-22.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةsinan-britannica - ^ Çelik 1993, p. 38

- ^ أ ب Magra, Iliana (5 November 2020). "Greeks in Istanbul keeping close eye on developments". www.ekathimerini.com. Ekathimerini. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Grigoryan, Iliana. "Armenian Labor Migrants in Istanbul" (PDF). Koç University. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ DHA, Daily Sabah with (2019-01-10). "Assyrian community thrives again in southeastern Turkey". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- ^ Heper, Metin (2018). Historical dictionary of Turkey (Fourth ed.). Lanham, ND: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-5381-0224-4.

- ^ Levantine historical heritage

- ^ Interview with Giovanni Scognamillo

- ^ أ ب ت Epstein, Mark Alan (1980). The Ottoman Jewish communities and their role in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Freiburg: K. Schwarz. ISBN 978-3-87997-077-3.

- ^ أ ب Makovetsky, Leah (1989). The Mediterranean and the Jews. Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press. pp. 75–104. ISBN 978-965-226-099-4.

- ^ Nassi, Gad (2010). Jewish journalism and printing houses in the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-61719-909-7.

- ^ Solomon, Norman (2015). Historical dictionary of Judaism (Third ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-4141-1.

- ^ أ ب "Panoramic view of the modern skyline of Istanbul's European side, with the skyscrapers of Levent at the center and the Bosphorus Bridge (1973) at right". Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ أ ب "A view of the skyscrapers in Levent from Sporcular Park". Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020. OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance. OECD Publishing. 2020. doi:10.1787/959d5ba0-en. ISBN 978-92-64-58785-4. S2CID 240715488. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Regions and Cities in Turkey at a Glance in 2018" (PDF). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Publishing. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Turkey trade statistics". World Bank. World Bank. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Oxford Business Group 2009, p. 112.

- ^ أ ب Jones, Sam (27 April 2011). "Istanbul's new Bosphorus canal 'to surpass Suez or Panama". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ أ ب "Maritime intelligence on Ambarlı port". Lloyd's List Maritime Intelligence. Lloyd's Insurance Services. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ أ ب "The Imperial Ottoman Bank Patrimoines Partagés تراث مشترك". heritage.bnf.fr. Bibliothèques d'Orient. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "nBorsa Istanbul: A Story of Transformation" (PDF). borsaistanbul.com. Borsa Istanbul. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Bentley, Mark; Harvey, Benjamin (17 September 2012). "Istanbul Aims to Outshine Dubai With $2.6 Billion Bank Center". Bloomberg Markets Magazine. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ "Istanbul Finance Center to open in 2022, gains traction from Middle East". Daily Sabah. 28 May 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

]]

ru-sib:Станбул

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 التركية-language sources (tr)

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- صفحات تستخدم جدول مستوطنة بقائمة محتملة لصفات المواطن

- صفحات تستخدم جدول مستوطنة بقائمة محتملة لمفاتيح الهاتف

- Pages using infobox settlement with no map

- Pages using infobox settlement with no coordinates

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles containing التركية العثماثية (1500-1928)-language text

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2020

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from April 2020

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- محافظة اسطنبول

- مدن تركيا

- منطقة مرمرة

- مواقع التراث العالمي في تركيا

- اسطنبول

- مدن ذات أهمية دينية مسيحية

- مواقع يونانية قديمة في تركيا

- مواقع أثرية في تركيا

- الامبراطورية البيزنطية

- أماكن مأهولة على طريق الحرير

- موانئ تركيا

- مدن مقدسة

- مدن الدولة العثمانية

- مواقع رومانية في تركيا

- عواصم وطنية سابقة

- عواصم أمم سابقة