حتوشا

Hattuşaş (Turkish) | |

The Lion Gate in the south-west | |

| المكان | Near Boğazkale, Çorum Province, Turkey |

|---|---|

| المنطقة | Anatolia |

| الإحداثيات | 40°01′11″N 34°36′55″E / 40.01972°N 34.61528°E |

| النوع | Settlement |

| التاريخ | |

| تأسس | 6th millennium BC |

| هـُـجـِر | ح. 1200 BC |

| الفترات | Bronze Age |

| الثقافات | Hittite |

| ملاحظات حول الموقع | |

| الحالة | In ruins |

حاتـّوشا Hattusha أو حاتـّوسا Hattusa أو حاتوساس Hattusas؛[1] بالحيثية: أورو URUḪa-at-tu-ša) هي عاصمة الامبراطورية الحثية، في أواخر العصر البرونزي التي تم الكشف عنها، تحت أنقاض موقع بوغازكوي بالقرب من بوغاز قلعه في شمالي وسط الأناضول، تركيا، ضمن الثنية الكبرى لنهر قزلإرماق (بالحيثية: مرشنتية؛ وباليونانية: نهر هالوس). اِكتُشفت المدينة منذ منتصف القرن التاسع عشر، وعثر فيها بنهاية القرن المذكور على أول الرُقُم المسمارية للغة الحثية. بدأ التنقيب الأثري في الموقع، في مطلع القرن العشرين، من قبل جمعية الاستشراق الألمانية، واستمر بفترات متقطعة على امتداد القرن المشار إليه.

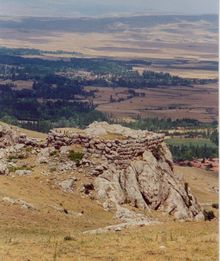

تقع المدينة في منطقة جبلية تتخللها مرتفعات مختلفة، أهمها مرتفع بويوك قلعه وبويوك كايا. تعود آثار الاستيطان الأول في الموقع إلى العصر الحجري النحاسي، وقد استمر هذا الاستيطان في عصر البرونز القديم، في الألف الثالث ق.م، وفي عصر البرونز الوسيط أصبح الموقع مستوطنة تجارية آشورية (چروم). إلا أن نشوء حاتوشا، عاصمة الدولة الحثية، يعود إلى القرن السادس عشر ق.م، في نهاية عصر البرونز الوسيط، وذلك على يد الحاكم الحثي حاتوشيلي الأول، ثم دُعمت على يد شوبيلوليوما في أوج قوة الامبراطورية الحثية في القرن الرابع عشر ق.م، إذ شُيدت مدينة ذات مخطط بيضاوي، بطول 2 كم تقريباً، أُحكم بناؤها لتتوافق مع المنطقة الجبلية الوعرة والأنهار المحيطة، وغدت نموذجاً لفن العمارة الحثي، المتميز بالفخامة والمتانة والاستخدام الكثيف للأعمدة والنوافذ والأبواب وللألواح الحجرية المختلفة.

التاريخ المبكر للمدينة

Before 2000 BC, the apparently indigenous Hattian people established a settlement on sites that had been occupied even earlier and referred to the site as Hattush. The Hattians built their initial settlement on the high ridge of Büyükkale.[2] The earliest traces of settlement on the site are from the sixth millennium BC. In the 19th and 18th centuries BC, merchants from Assur in Assyria established a trading post there, setting up in their own separate quarter of the city. The center of their trade network was located in Kanesh (Neša) (modern Kültepe). Business dealings required record-keeping: the trade network from Assur introduced writing to Hattusa, in the form of cuneiform.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الطبقة المتفحمة الواضحة في الحفريات تشهد بحرق وتدمير مدينة حاتوشا حوالي سنة 1700 ق.م. الطرف المسئول عن ذلك يبد أنه كان الملك أنيتـّا من Kussara (مدينة ربما كانت اليشار)، الذي أعلن مسئوليته عن الفعلة وأقام نصباً ونقش عليه لعنة باقية ليومنا هذا:

في الليل، استوليت على المدينة بالقوة؛ وبذرت الحشائش مكانها. فإذا حاول أي ملك بعدي أن يعيد إنشاء حاتوشا، فليدمّره إله العواصف السماوية.[3]

المدينة الإمبراطورية الحيثية

بلغت حاتوشا أوج ازدهارها بين عامي 1350 و1200 ق.م.

Only a generation later, a Hittite-speaking king chose the site as his residence and capital. The Hittite language had been gaining speakers at the expense of Hattic for some time. The Hattic Hattush now became the Hittite Hattusa, and the king took the name of Hattusili, the "one from Hattusa". Hattusili marked the beginning of a non-Hattic-speaking "Hittite" state and of a royal line of Hittite Great Kings, 27 of whom are now known by name.

After the Kaskians arrived to the kingdom's north, they twice attacked the city to the point where the kings had to move the royal seat to another city. Under Tudhaliya I, the Hittites moved north to Sapinuwa, returning later. Under Muwatalli II, they moved south to Tarhuntassa but assigned Hattusili III as governor over Hattusa. Mursili III returned the seat to Hattusa, where the kings remained until the end of the Hittite kingdom in the 12th century BC.

في أقصى اتساع لها غطت مساحة 1.8 كم²، وأحاطها سور دفاعي أول، يليه سور ثان سماكته 8م، تعلوه الأبراج. الأسوار شيدها Suppiluliuma I (circa 1344–1322 BC (short chronology)). The inner city covered an area of some 0.8 km² and was occupied by a citadel with large administrative buildings and temples. The royal residence, or acropolis, was built on a high ridge now known as Büyükkale (Great Fortress).[4] The city displayed over 6 km of walls, with inner and outer skins around 3 m of thick and 2 m of space between them, adding 8 m of the total thickness.[5]

ويخترق السور ثلاث بوابات كبرى، تحرسها تماثيلُ «أبي الهول» عند البوابة الجنوبية و«الأُسود» عند البوابة الغربية و«المحاربين» عند البوابة الشرقية، ويقود إلى داخل المدينة نفق حجري سرّي بطول 71م، تغطيه البلاطات الحجرية.

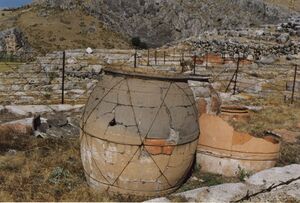

تقوم في داخل السور أبنية المدينة الرئيسة، وأهمها القلعة «بويوك قلعه» وهي ذات شكل بيضوي (140×250م)، يحيط بها سور دفاعي تخترقه بوابة رئيسة. وقد بُنيت القلعة على ثلاثة مستويات متتالية، تتوسط المستوى الأول باحة مركزية (70×35م)، تقود بدورها إلى باحة أخرى، وتلتف حول الباحات أبنية تحيط بها الأروقة من كل جهاتها. في داخل القلعة يقع القصر، وهو بناء مربع ضلعه 33م، وهناك المكتبة، حيث عُثر على آلاف الرُقُم الكتابية، وبينها نص المعاهدة التي تمت بين الحثيين والمصريين، إثر معركة قادش الشهيرة في سورية في بداية القرن الثالث عشر ق.م، بينما تقوم الأبنية السكنية في الجزء الشمالي الغربي من القلعة. كُشف في المدينة عن خمسة معابد، شُيدت بشكل معزول في العراء، لكل منها مخططها الخاص، أربعة معابد تقوم في القسم الجنوبي من المدينة، والمعبد الخامس، وهو الأهم، معبد رب العاصفة، الذي شيد على مصطبة عالية في شمالي المدينة، ويتألف من قسمين رئيسين، كما هي حال المعابد الرافدية، تحيط الأروقة بباحته الرئيسة، وتلحق به المخازن والمستودعات والمشاغل وبيوت العاملين فيه.

To the south lay an outer city of about 1 km2, with elaborate gateways decorated with reliefs showing warriors, lions, and sphinxes. Four temples were located here, each set around a porticoed courtyard, together with secular buildings and residential structures. Outside the walls are cemeteries, most of which contain cremation burials. Modern estimates put the population of the city between 40,000 and 50,000 at the peak; in the early period, the inner city housed a third of that number. The dwelling houses that were built with timber and mud bricks have vanished from the site, leaving only the stone-built walls of temples and palaces.

The city was destroyed, together with the Hittite state itself, around 1200 BC, as part of the Bronze Age collapse. Excavations suggest that Hattusa was gradually abandoned over a period of several decades as the Hittite empire disintegrated.[6] The site was subsequently abandoned until 800 BC, when a modest Phrygian settlement appeared in the area.

الاندثار

قبل أن تدمّر، على يد شعوب البحر غالباً، وتهجر لنحو ثلاثة قرون، ثم يعاد استيطانها من قبل المهاجرين الفريجيين (وهم أحد شعوب البحر القادمين من شبه جزيرة البلقان) الذين جددوا في القرن الثامن قبل الميلاد بناء أسوار المدينة وقلعتها ومعبدها وقصرها، والتي يُعتقد أن اسمها أضحى پتريا Petria، التي ازدهرت في منتصف القرن السادس ق.م، قبل أن يدمرها الفرس بحسب ما أورده هيرودت.

الاكتشاف

In 1833, the French archaeologist Charles Texier (1802–1871) was sent on an exploratory mission to Turkey, where in 1834 he discovered ruins of the ancient Hittite capital of Hattusa.[7] إرنست شانتر opened some trial trenches at the village then called Boğazköy, in 1893–94.[8] Since 1906, the German Oriental Society has been excavating at Hattusa (with breaks during the two World Wars and the Depression, 1913–31 and 1940–51). Archaeological work is still carried out by the German Archaeological Institute (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut). Hugo Winckler and Theodore Makridi Bey conducted the first excavations in 1906, 1907, and 1911–13, which were resumed in 1931 under Kurt Bittel, followed by Peter Neve (site director 1963, general director 1978–94).[9]

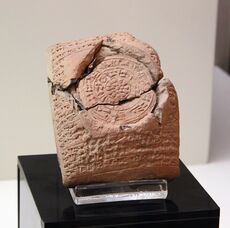

الأرشيف الملكي بالمسمارية

One of the most important discoveries at the site has been the cuneiform royal archives of clay tablets, known as the Bogazköy Archive, consisting of official correspondence and contracts, as well as legal codes, procedures for cult ceremony, oracular prophecies and literature of the ancient Near East. وأهم تلك الألواح، معروض حالياً في متحف اسطنبول الأثري، ويفصل بنود معاهدة السلام التي تم التوصل إليها بعد أعوام من معركة قادش بين الحيثيين والمصريين بقيادة رمسيس الثاني، في 1259 أو 1258 ق.م. وتـُعرض نسخة منها في الأمم المتحدة في مدينة نيويورك كمثال لأقدم معاهدة سلام دولية معروفة للبشر.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Although the 30,000 or so clay tablets recovered from Hattusa form the main corpus of Hittite literature, archives have since appeared at other centers in Anatolia, such as Tabigga (Maşat Höyük) and Sapinuwa (Ortaköy). They are now divided between the archaeological museums of Ankara and Istanbul.[بحاجة لمصدر]

تماثيل أبو الهول

A pair of sphinxes found at the southern gate in Hattusa were taken for restoration to Germany in 1917. The better-preserved was returned to Turkey in 1924 and placed on display in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, but the other remained in Germany where it was on display at the Pergamon Museum from 1934,[10] despite numerous requests for its return.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In 2011, threats by Turkish Ministry of Culture to impose restrictions on German archaeologists working in Turkey finally persuaded Germany to return the sphinx, and it was moved to the Boğazköy Museum outside the Hattusa ruins, along with the Istanbul sphinx[11] – reuniting the pair near their original location.[بحاجة لمصدر]

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ "Hattusas". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ The Excavations at Hattusha: "A Brief History" Archived 2012-05-27 at archive.today

- ^ Hamblin, William J. Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. New York: Routledge, 2006.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: Büyükkale

- ^ Lewis, Leo Rich; Tenney, Charles R. (2010). The Compendium of Weapons, Armor & Castles. Nabu Press. p. 142. ISBN 1146066848.

- ^ Beckman, Gary (2007). "From Hattusa to Carchemish: The latest on Hittite history" (PDF). In Chavalas, Mark W. (ed.). Current Issues in the History of the Ancient Near East. Claremont, California: Regina Books. pp. 97–112. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ See:

- Texier, Charles (1835). "Rapport lu, le 15 mai 1835, à l'Académie royale des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres de l'Institut, sur un envoi fait par M. Texier, et contenant les dessins de bas-reliefs découverts par lui près du village de Bogaz-Keui, dans l'Asie mineure" [Report read on 15 May 1835 to the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Belle-lettres of the Institute, on a dispatch made by Mr. Texier and containing drawings of bas-reliefs discovered by him near the village of Bogaz-Keui [now: Boğazkale] in Asia Minor]. Journal des Savants (in الفرنسية): 368–376.

- Texier, Charles (1839). Description de l'Asie Mineure: faite par ordre du gouvernement français en 1833–1837 … [Description of Asia Minor: done by order of the French government in 1833–1837 …] (in الفرنسية). Vol. 1. Paris, France: Didot Frères. pp. 209ff. Available at: University of Heidelberg, Germany

- Bittel, Kurt (1983). "Quelques remarques archéologiques sur la topographie de Hattuša" [Some archaeological remarks on the topography of Hattusa]. Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in الفرنسية). 127 (3): 485–509.

- ^ "The Excavations at Hattusha - a project of the German Institute of Archaeology": Discovery Archived 2010-04-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jürgen Seeher, "Forty Years in the Capital of the Hittites: Peter Neve Retires from His Position as Director of the Ḫattuša-Boğazköy Excavations" The Biblical Archaeologist 58.2, "Anatolian Archaeology: A Tribute to Peter Neve" (June 1995), pp. 63-67.

- ^ "Germany returns Sphinx of Hattusa to Turkey". 2011-05-13. Archived from the original on 2014-08-25.

- ^ "Hattuşa reunites with sphinx". Hürriyet Daily News. 18 November 2011.

وصلات خارجية

ببليوجرافيا

- Peter Neve: Hattusa - Stadt der Götter und Tempel. Neue Ausgrabungen in der Hauptstadt der Hethiter. Ph. von Zabern, Mainz 1996. (2. erw. Aufl.) ISBN 3-8053-1478-7

- W. Dörfler u.a.: Untersuchungen zur Kulturgeschichte und Agrarökonomie im Einzugsbereich hethitischer Städte. MDOG Berlin 132, 2000, 367-381. ISSN 0342-118X

]]

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Webarchive template archiveis links

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Articles containing Hittite-language text

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox ancient site with unknown parameters

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2021

- Pages with empty portal template

- مواقع التراث العالمي في تركيا

- محافظة چروم

- مواقع ما قبل التاريخ في تركيا

- مدن حاتية

- مواقع حثية في تركيا

- مدن حيثية

- أماكن مأهولة سابقاً في تركيا

- مواقع أثرية في تركيا