حروب البلقان

| حروب البلقان | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Bulgarian postcard depicting the Battle of Lule Burgas. | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

|

First Balkan War: |

First Balkan War: | ||||||

|

Second Balkan War: |

Second Balkan War: | ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| القوى | |||||||

|

|

1,093,800 men | ||||||

|

Altogether: 2,914,020–3,484,830 troops deployed plus 600,000 killed or injured | |||||||

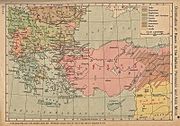

حروب البلقان اسم يطلق على حربين حدثتا في منطقة البلقان في جنوب شرق اوروبا نتيجة صراع الدول البلقانية: بلغاريا، اليونان ، صربيا بين عامي 1912-1913 للسيطرة على مقدونيا و معظم تراقيا Thrace التي كانت ما تزال تحت السيطرة العثمانية والسيطرة على الغنائم . لكن بلغاريا منيت بالهزيمة في النهاية و خسرت معظم ما قد وعدت به في خطة التقسيم الأولية. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defeated it, in the process stripping the Ottomans of its European provinces, leaving only Eastern Thrace under the Ottoman Empire's control. In the Second Balkan War, Bulgaria fought against the other four original combatants of the first war. It also faced an attack from Romania from the north. The Ottoman Empire lost the bulk of its territory in Europe. Although not involved as a combatant, Austria-Hungary became relatively weaker as a much enlarged Serbia pushed for union of the South Slavic peoples.[1] The war set the stage for the Balkan crisis of 1914 and thus served as a "prelude to the First World War".[2]

By the early 20th century, Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia had achieved independence from the Ottoman Empire, but large elements of their ethnic populations remained under Ottoman rule. In 1912, these countries formed the Balkan League. The First Balkan War began on 8 October 1912, when the League member states attacked the Ottoman Empire, and ended eight months later with the signing of the Treaty of London on 30 May 1913. The Second Balkan War began on 16 June 1913, when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its loss of Macedonia, attacked its former Balkan League allies. The combined forces of Serbian and Greek armies, with their superior numbers repelled the Bulgarian offensive and counter-attacked Bulgaria by invading it from the west and the south. Romania, having taken no part in the conflict, had intact armies to strike with and invaded Bulgaria from the north in violation of a peace treaty between the two states. The Ottoman Empire also attacked Bulgaria and advanced in Thrace regaining Adrianople. In the resulting Treaty of Bucharest, Bulgaria managed to regain most of the territories it had gained in the First Balkan War. However, it was forced to cede the ex-Ottoman south part of Dobruja province to Romania.[3]

The Balkan Wars were marked by ethnic cleansing with all parties being responsible for grave atrocities against civilians and helped inspire later atrocities including war crimes during the 1990s Yugoslav Wars.[4][5][6][7]

خلفية

The background to the wars lies in the incomplete emergence of nation-states on the European territory of the Ottoman Empire during the second half of the 19th century. Serbia had gained substantial territory during the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878, while Greece acquired Thessaly in 1881 (although it lost a small area back to the Ottoman Empire in 1897) and Bulgaria (an autonomous principality since 1878) incorporated the formerly distinct province of Eastern Rumelia (1885). All three countries, as well as Montenegro, sought additional territories within the large Ottoman-ruled region known as Rumelia, comprising Eastern Rumelia, Albania, Macedonia, and Thrace.

The First Balkan War had some main causes, which included:[8][2][9]

- The Ottoman Empire was unable to reform itself, govern satisfactorily, or deal with the rising ethnic nationalism of its diverse peoples.

- The Italo-Ottoman war of 1911 and the Albanian Revolts in the Albanian Provinces showed that the Empire was deeply "wounded" and unable to strike back against another war.

- The Great Powers quarreled amongst themselves and failed to ensure that the Ottomans would carry out the needed reforms. This led the Balkan states to impose their own solution.

- The Christian populations of the European part of the Ottoman Empire were oppressed by the Ottoman Reign, thus forcing the Christian Balkan states to take action.

- Most importantly, the Balkan League was formed, and its members were confident that under those circumstances an organised and simultaneous declaration of war to the Ottoman Empire would be the only way to protect their compatriots and expand their territories in the Balkan Peninsula.

سياسات القوى العظمى

Throughout the 19th century, the Great Powers shared different aims over the "Eastern Question" and the integrity of the Ottoman Empire. Russia wanted access to the "warm waters" of the Mediterranean from the Black Sea; it pursued a pan-Slavic foreign policy and therefore supported Bulgaria and Serbia. Britain wished to deny Russia access to the "warm waters" and supported the integrity of the Ottoman Empire, although it also supported a limited expansion of Greece as a backup plan in case integrity of the Ottoman Empire was no longer possible. France wished to strengthen its position in the region, especially in the Levant (today's Lebanon, Syria, and Israel).[10]

Habsburg-ruled Austria-Hungary wished for a continuation of the existence of the Ottoman Empire, since both were troubled multinational entities and thus the collapse of the one might weaken the other. The Habsburgs also saw a strong Ottoman presence in the area as a counterweight to the Serbian nationalistic call to their own Serb subjects in Bosnia, Vojvodina and other parts of the empire. Italy's primary aim at the time seems to have been the denial of access to the Adriatic Sea to another major sea power. The German Empire, in turn, under the "Drang nach Osten" policy, aspired to turn the Ottoman Empire into its own de facto colony, and thus supported its integrity. In the late 19th and early 20th century, Bulgaria and Greece contended for Ottoman Macedonia and Thrace. Ethnic Greeks sought the forced "Hellenization" of ethnic Bulgars, who sought "Bulgarization" of Greeks (Rise of nationalism). Both nations sent armed irregulars into Ottoman territory to protect and assist their ethnic kindred. From 1904, there was low-intensity warfare in Macedonia between the Greek and Bulgarian bands and the Ottoman army (the Struggle for Macedonia). After the Young Turk revolution of July 1908, the situation changed drastically.[11]

ثورة تركيا الفتاة

The 1908 Young Turk Revolution saw the reinstatement of constitutional monarchy in the Ottoman Empire and the start of the Second Constitutional Era. When the revolt broke out, it was supported by intellectuals, the army, and almost all the ethnic minorities of the Empire. It forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to re-adopt the defunct Ottoman constitution of 1876 and parliament. Hopes were raised among the Balkan ethnicities of reforms and autonomy. Elections were held to form a representative, multi-ethnic, Ottoman parliament. However, following the Sultan's failed counter-coup of 1909, the liberal element of the Young Turks was sidelined and the nationalist element became dominant.[12]

In October 1908, Austria-Hungary seized the opportunity of the Ottoman political upheaval to annex the de jure Ottoman province of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which it had occupied since 1878 (see Bosnian Crisis). Bulgaria declared independence as it had done in 1878, but this time the independence was internationally recognized. The Greeks of the autonomous Cretan State proclaimed unification with Greece, though the opposition of the Great Powers prevented the latter action from taking practical effect.[13]

رد الفعل في بلدان البلقان

Serbia was frustrated in the north by Austria-Hungary's incorporation of Bosnia. In March 1909, Serbia was forced to accept the annexation and restrain anti-Habsburg agitation by Serbian nationalists. Instead, the Serbian government (PM: Nikola Pašić) looked to formerly Serb territories in the south, notably "Old Serbia" (the Sanjak of Novi Pazar and the province of Kosovo).

On 15 August 1909, the Military League, a group of Greek officers, launched a coup. The Military League sought the creation of a new political system and thus summoned the Cretan politician Eleutherios Venizelos to Athens as its political advisor. Venizelos persuaded King George I to revise the constitution and asked the League to disband in favor of a National Assembly. In March 1910, the Military League dissolved itself.[9][14]

Bulgaria, which had secured Ottoman recognition of her independence in April 1909 and enjoyed the friendship of Russia,[15] also looked to annex districts of Ottoman Thrace and Macedonia. In August 1910, Montenegro followed Bulgaria's precedent by becoming a kingdom.

معاهدات ما قبل الحرب

Following the Italian victory in the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912, the severity of the Ottomanizing policy of the Young Turkish regime and a series of three revolts in Ottoman held Albania, the Young Turks fell from power after a coup. The Christian Balkan countries were forced to take action and saw this as an opportunity to promote their national agenda by expanding in the territories of the falling empire and liberating their enslaved co-patriots. In order to achieve that, a wide net of treaties was constructed and an alliance was formed.

The negotiation among the Balkan states' governments started in the latter part of 1911 and was all conducted in secret. The treaties and military conventions were published in French translations after the Balkan Wars on 24–26 of November in Le Matin, Paris, France [16] In April 1911, Greek PM Eleutherios Venizelos’ attempt to reach an agreement with the Bulgarian PM and form a defensive alliance against the Ottoman Empire was fruitless, because of the doubts the Bulgarians held on the strength of the Greek Army.[16] Later that year, in December 1911, Bulgaria and Serbia agreed to start negotiations in forming an alliance under the tight inspection of Russia. The treaty between Serbia and Bulgaria was signed on 29 of February/13 of March 1912. Serbia sought expansion to "Old Serbia" and as Milan Milovanovich noted in 1909 to the Bulgarian counterpart, "As long as we are not allied with you, our influence over the Croats and Slovens will be insignificant".[17] On the other side, Bulgaria wanted the autonomy of Macedonia region under the influence of the two countries. The then Bulgarian Minister of Foreign Affairs General Stefan Paprikov stated in 1909 that, "It will be clear that if not today then tomorrow, the most important issue will again be the Macedonian Question. And this question, whatever happens, cannot be decided without more or less direct participation of the Balkan States".[17] Last but not least, they noted down the divisions should be made of the Ottoman territories after a victorious outcome of the war. More specifically, Bulgaria would gain all the territories eastern of Rodopi Mountains and River Strimona, while Serbia would annex the territories northern and western of Mount Skardu.[9]

The alliance pact between Greece and Bulgaria was finally signed on 16/29 of May 1912, without stipulating any specific division of Ottoman territories.[16][17] In summer 1912, Greece proceeded on making "gentlemen's agreements" with Serbia and Montenegro.[17] Despite the fact that a draft of the alliance pact with Serbia was submitted on 22 of October, a formal pact was never signed due to the outbreak of the war. As a result, Greece did not have any territorial or other commitments, other than the common cause to fight the Ottoman Empire.

In April 1912 Montenegro and Bulgaria reached an agreement including financial aid to Montenegro in case of war with the Ottoman Empire. A gentlemen's agreement with Greece was reached soon after, as mentioned before. By the end of September a political and military alliance between Montenegro and Serbia was achieved.[16] By the end of September 1912, Bulgaria had formal-written alliances with Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro. A formal alliance was also signed between Serbia and Montenegro, while Greco-Montenegrin and Greco-Serbian agreements were basically oral "gentlemen's agreements".[بحاجة لمصدر] All these completed the formation of the Balkan League.

عصبة البلقان

مقالة مفصلة: رابطة البلقان

مقالة مفصلة: رابطة البلقان

At that time, the Balkan states had been able to maintain armies that were both numerous, in relation to each country's population, and eager to act, being inspired by the idea that they would free enslaved parts of their homeland.[17] The Bulgarian Army was the leading army of the coalition. It was a well-trained and fully equipped army, capable of facing the Imperial Army. It was suggested that the bulk of the Bulgarian Army would be in the Thracian front, as it was expected that the front near the Ottoman Capital would be the most crucial one. The Serbian Army would act on the Macedonian front, while the Greek Army was thought powerless and was not taken under serious consideration. Greece was needed in the Balkan League for its navy and its capability to dominate the Aegean Sea, cutting off the Ottoman Armies from reinforcements.[بحاجة لمصدر]

On 13/26 of September 1912, the Ottoman mobilization in Thrace forced Serbia and Bulgaria to act and order their own mobilization. On 17/30 of September Greece also ordered mobilization. On 25 of September/8 of October, Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire, after negotiations failed regarding the border status. On 30 of September/13 of October, the ambassadors of Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece delivered the common ultimatum to the Ottoman government, which was immediately rejected. The Empire withdrew its ambassadors from Sofia, Belgrade, and Athens, while the Bulgarian, Serbian and Greek diplomats left the Ottoman capital delivering the war declaration on 4/17 of October 1912.[9]

رابطة البلقان كانت تحالفاً شكلته سلسلة من المعاهدات الثنائية أبرمت في 1912 بين دول البلقان المسيحية ووُجـِّهت ضد الدولة العثمانية[18]، التي كانت آنئذ مسيطرة على معظم شبه جزيرة البلقان. وكان البلقان تمور منذ مطلع عقد 1900، بسنوات من حرب العصابات في مقدونيا تبعتها ثورة تركيا الفتاة والأزمة البوسنية الممتدة ردحاً. اندلاع الحرب الإيطالية التركية في 1911 زاد في إضعاف العثمانيين وشجع دول البلقان. وبتأثير روسي، سوت صربيا وبلغاريا خلافاتهما وأبرما تحالفاً، كان في الأصل موجهاً ضد النمسا-المجر في 13 مارس 1912[19]، ولكن باضافة فصل سري إليها تغير اتجاه التحالف بشكل رئيسي ليصبح ضد الدولة العثمانية[20]. وكانت صربيا قد وقعت تحالفاً متبادلاً مع الجبل الأسود، بينما فعلت بلغاريا الشيء نفسه مع اليونان. وقد انتصرت الرابطة في حرب البلقان الأولى التي اندلعت في 1912، حيث نجحت في انتزاع السيطرة على تقريباً جميع الأراضي العثمانية. إلا أنه بعد ذلك النصر، برزت إلى السطح خلافات السابقة بين أولئك الحلفاء على تقاسم الغنائم، وخصوصاً مقدونيا، مما أدى إلى انفراط عقد الرابطة، وتلا ذلك مباشرة في 16 يونيو 1913، هجوم بلغاريا على حلفائها السابقين، لتبدأ حرب البلقان الثانية.

حرب البلقان الأولى

عقدت بلغاريا وصربيا معاهدة سرية فيما بينهما سنة 1912م، ووفقاً للاتفاقية كان القسم الأكبر من ألبانيا من نصيب صربيا، وبدأت الحرب في 8 أكتوبر 1912م بين تركيا من جهة والجبل الأسود وبلغاريا وصربيا واليونان من جهة أخرى. وتكبَّدت تركيا خسائر كبيرة خلال الحرب، ووقَّعت اتفاقية عسكرية في 3 ديسمبر 1912م، بعد أن طلب الأتراك عقد هدنة لوقف القتال. وتبع ذلك عقد مؤتمر سلام في لندن حيث طلبت دول شبه جزيرة البلقان من تركيا التخلي عن الأراضي المحتلة ودفع تعويضات الحرب، غير أن تركيا رفضت تلك المطالب، مما أدَّى إلى استئناف الحرب بدءًا من 3 فبراير حتى 3 مايو 1913م. وسيطرت اليونان وبلغاريا والجبل الأسود على مزيد من الأراضي في شبه الجزيرة. عقد مؤتمر سلام ثان في لندن في 20 مايو 1913م تحت رعاية القُوى العُظمى، وتم توقيع معاهدة سلام في 30 مايو تم بموجبها تخلي تركيا عن معظم أراضيها الأوروبية.

تمهيد لحرب البلقان الثانية

After pressure from the Great Powers towards Greece and Serbia, who had postponed signing in order to fortify their defensive positions, [21] the signing of the Treaty of London took place on 30 May 1913. With this treaty, the war between the Balkan Allies and the Ottoman Empire came to an end. From now on, the Great Powers had the right of decision on the territorial adjustments that had to be made, which even led to the creation of an independent Albania. Every Aegean island belonging to the Ottoman Empire, with the exception of Imbros and Tenedos, was handed over to the Greeks, including the island of Crete.

Furthermore, all European territory of the Ottoman Empire west of the Enos-Midia (Enez-Midye) line, was ceded to the Balkan League, but the division of the territory among the League was not to be decided by the Treaty itself.[22] This event led to the formation of two ‘de facto’ military occupation zones on the Macedonian territory, as Greece and Serbia tried to create a common border. The Bulgarians were not satisfied with their share of spoils and as a result, the Second Balkan War broke out on the night of 29 June 1913, as Bulgaria confronted the Serbian and Greek lines in Macedonia.[23]

حرب البلقان الثانية

شهدت دول البلقان خلافات جوهرية فيما بينها خلال الأيام الأولى بعد حرب البلقان الأولى، حيث أصرَّ البلغاريون على إرسال جنود إلى سالونيكا في اليونان، أما الجبل الأسود فلم تكن راضية عن معاهدة لندن، حيث إن القُوى العُظمى منحت شكودر لألبانيا، وذلك عكس ما تم الاتفاق عليه سراً قبل حرب البلقان الأولى.

وقد أدركت كل من بلغاريا وصربيا أن معاهدة التقسيم غدت قديمة وتحتاج تعديلاً، وقد رغبت صربيا في مساعدة قيصر روسيا على تقسيم مقدونيا بين صربيا وبلغاريا، غير أنه لم يكن لبلغاريا ثقة قوية بقيصر روسيا، وقد أمِلت بلغاريا بأن النمسا والمجر اللتين تخشيان تزايد قوة صربيا، سوف تقدِّمان المساعدة لها. أما صربيا فقد عقدت معاهدة تحالف مع اليونان في 1 يونيو 1913م.

بدأت حرب البلقان الثانية في 29 - 30 يونيو 1913، حين هاجمت جيوش بلغاريا كلاً من اليونان وصربيا. لقد كانت حرباً قصيرة غير أنها كانت أكثر دموية من الحرب الأولى، وقد انضم الأتراك في تلك الحرب إلى جانب اليونانيين والصربيين، ولم تستطع بلغاريا الصمود أمام ذلك التحالف، ومن ثمَّ طلبت ترتيب هدنة لوقف القتال، وبالفعل تم توقيع معاهدة بوخارست في 10 أغسطس سنة 1913م. وكان من نتائج تلك الحرب أن خسرت بلغاريا معظم الأراضي التي أخذتها من تركيا.

When the Greek army had entered Thessaloniki in the First Balkan War ahead of the Bulgarian 7th division by only a day, they were asked to allow a Bulgarian battalion to enter the city. Greece accepted in exchange for allowing a Greek unit to enter the city of Serres. The Bulgarian unit that entered Thessaloniki turned out to be an 18,000-strong division instead of the battalion, which caused concern among the Greeks, who viewed it as a Bulgarian attempt to establish a condominium over the city. In the event, due to the urgently needed reinforcements in the Thracian front, Bulgarian Headquarters was soon forced to remove its troops from the city (while the Greeks agreed by mutual treaty to remove their units based in Serres) and transport them to Dedeağaç (modern Alexandroupolis), but it left behind a battalion that started fortifying its positions.

Greece had also allowed the Bulgarians to control the stretch of the Thessaloniki-Constantinople railroad that lay in Greek-occupied territory since Bulgaria controlled the largest part of this railroad towards Thrace. After the end of the operations in Thrace, and confirming Greek concerns, Bulgaria was not satisfied with the territory it controlled in Macedonia and immediately asked Greece to relinquish its control over Thessaloniki and the land north of Pieria, effectively handing over all of Greek Macedonia. These demands, with the Bulgarian refusal to demobilize its army after the Treaty of London had ended the common war against the Ottomans, alarmed Greece, which decided to also keep its army mobilized. A month after the Second Balkan War started, the Bulgarian community of Thessaloniki no longer existed, as hundreds of long-time Bulgarian locals were arrested. Thirteen hundred Bulgarian soldiers and about five hundred komitadjis were also arrested and transferred to Greek prisons. In November 1913, the Bulgarians were forced to admit their defeat, as the Greeks received international recognition on their claim of Thessaloniki.[24]

Similarly, in modern North Macedonia, the tension between Serbia and Bulgaria due to the latter's aspirations over Vardar Macedonia generated many incidents between their respective armies, prompting Serbia to keep its army mobilized. Serbia and Greece proposed that each of the three countries reduce its army by a quarter, as the first step towards a peaceful solution, but Bulgaria rejected it. Seeing the omens, Greece and Serbia started a series of negotiations and signed a treaty on 1 June(19 May) 1913. With this treaty, a mutual border was agreed between the two countries, together with an agreement for mutual military and diplomatic support in case of a Bulgarian or/and Austro-Hungarian attack. Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, being well informed, tried to stop the upcoming conflict on 8 June, by sending an identical personal message to the Kings of Bulgaria and Serbia, offering to act as arbitrator according to the provisions of the 1912 Serbo-Bulgarian treaty. But Bulgaria, by making the acceptance of Russian arbitration conditional, in effect denied any discussion, causing Russia to repudiate its alliance with Bulgaria (see Russo-Bulgarian military convention signed 31 May 1902).

The Serbs and the Greeks had a military advantage on the eve of the war because their armies confronted comparatively weak Ottoman forces in the First Balkan War and suffered relatively light casualties,[25] while the Bulgarians were involved in heavy fighting in Thrace. The Serbs and Greeks had time to fortify their positions in Macedonia. The Bulgarians also held some advantages, controlling internal communication and supply lines.[25]

On 29(16) June 1913, General Savov, under direct orders of Tsar Ferdinand I, issued attack orders against both Greece and Serbia without consulting the Bulgarian government and without an official declaration of war.[26] During the night of 30(17) June 1913, they attacked the Serbian army at Bregalnica river and then the Greek army in Nigrita. The Serbian army resisted the sudden night attack, while most of the soldiers did not even know who they were fighting with, as Bulgarian camps were located next to Serbs and were considered allies. Montenegro's forces were just a few kilometers away and also rushed to the battle. The Bulgarian attack was halted.

The Greek army was also successful.[25][مطلوب مصدر أفضل] It retreated according to plan for two days while Thessaloniki was cleared of the remaining Bulgarian regiment. Then, the Greek army counterattacked and defeated the Bulgarians at Kilkis (Kukush), after which the mostly Bulgarian town was plundered and burnt and part of its mostly Bulgarian population massacred by the Greek army.[27][مطلوب مصدر أفضل] Following the capture of Kilkis, the Greek army's pace was not quick enough to prevent the retaliatory destruction of Nigrita, Serres, and Doxato and massacres of non-combatant Greek inhabitants at Sidirokastro and Doxato by the Bulgarian army.[28] The Greek army then divided its forces and advanced in two directions. Part proceeded east and occupied Western Thrace. The rest of the Greek army advanced up to the Struma River valley, defeating the Bulgarian army in the battles of Doiran and Mt. Beles, and continued its advance to the north towards Sofia. In the Kresna straits, the Greeks were ambushed by the Bulgarian 2nd and 1st Armies, newly arrived from the Serbian front, that had already taken defensive positions there following the Bulgarian victory at Kalimanci.

By 30 July, the Greek army was outnumbered by the counter-attacking Bulgarian army, which attempted to encircle the Greeks in a Cannae-type battle, by applying pressure on their flanks.[29] The Greek army was exhausted and faced logistical difficulties. The battle was continued for 11 days, between 29 July and 9 August over 20 km of a maze of forests and mountains with no conclusion. The Greek king, seeing that the units he fought were from the Serbian front, tried to convince the Serbs to renew their attack, as the front ahead of them was now thinner, but the Serbs declined. By then, news came of the Romanian advance toward Sofia and its imminent fall. Facing the danger of encirclement, Constantine realized that his army could no longer continue hostilities. Thus, he agreed to Eleftherios Venizelos' proposal and accepted the Bulgarian request for an armistice as had been communicated through Romania.

Romania had raised an army and declared war on Bulgaria on 10 July (27 June) as it had from 28 (15) June officially warned Bulgaria that it would not remain neutral in a new Balkan war, due to Bulgaria's refusal to cede the fortress of Silistra as promised before the First Balkan War in exchange for Romanian neutrality. Its forces encountered little resistance and, by the time the Greeks accepted the Bulgarian request for an armistice, they had reached Vrazhdebna, 11 km (7 mi) from the center of Sofia.

Seeing the military position of the Bulgarian army, the Ottomans decided to intervene. They attacked, and, finding no opposition, managed to win back all of their lands which had been officially ceded to Bulgaria as a part of the Sofia Conference in 1914, i.e. Thrace with its fortified city of Adrianople, regaining an area in Europe which was only slightly larger than the present-day European territory of the Republic of Turkey.

ردود الأفعال بين القوى العظمى أثناء الحروب

The developments that led to the First Balkan War did not go unnoticed by the Great Powers. Although there was an official consensus between the European Powers over the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire, which led to a stern warning to the Balkan states, unofficially each of them took a different diplomatic approach due to their conflicting interests in the area. As a result, any possible preventive effect of the common official warning was cancelled by the mixed unofficial signals, and failed to prevent or to stop the war:

- Russia was a prime mover in the establishment of the Balkan League and saw it as an essential tool in case of a future war against its rival, the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[30] However, it was unaware of the Bulgarian plans over Thrace and Constantinople, territories on which it had long-held ambitions, and on which it had just secured a secret agreement of expansion from its allies France and Britain, as a reward for participating in the upcoming Great War against the Central Powers.

- France, not feeling ready for a war against Germany in 1912, took a totally negative position against the war, firmly informing its ally Russia that it would not take part in a potential conflict between Russia and Austria-Hungary if it resulted from the actions of the Balkan League. The French, however, failed to achieve British participation in a common intervention to stop the Balkan conflict.

- Great Britain, although officially a staunch supporter of the Ottoman Empire's integrity, took secret diplomatic steps encouraging Greek entry into the League in order to counteract Russian influence. At the same time, it encouraged Bulgarian aspirations over Thrace, preferring a Bulgarian Thrace to a Russian one, despite the assurances the British government had given to the Russians in regard to Russia's expansion there.

- Austria-Hungary, struggling for a port on the Adriatic and seeking ways for expansion in the south at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, was totally opposed to any other nation's expansion in the area. At the same time, the Habsburg empire had its own internal problems with significant Slav populations that campaigned against German-Hungarian control of the multinational state. Serbia, whose aspirations in the direction of Austrian-held Bosnia were no secret, was considered an enemy and the main tool of Russian machinations that were behind the agitation of Austria's Slav subjects. But Austria-Hungary failed to secure German backup for a firm reaction. Initially, Emperor Wilhelm II told the Archduke Franz Ferdinand that Germany was ready to support Austria in all circumstances — even at the risk of a world war, but the Austro-Hungarians hesitated. Finally, in the German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912 the consensus was that Germany would not be ready for war until at least mid-1914 and passed notes to that effect to the Habsburgs. Consequently, no actions could be taken when the Serbs acceded to the Austrian ultimatum of 18 October and withdrew from Albania.

- Germany, already heavily involved in internal Ottoman politics, officially opposed a war against the Empire. But, in her effort to win Bulgaria for the Central Powers, and seeing the inevitability of Ottoman disintegration, was toying with the idea of replacing the Balkan area of the Ottomans with a friendly Greater Bulgaria in her San Stefano borders—an idea that was based on the German origin of the Bulgarian King and his anti-Russian sentiments.

The Second Balkan war was a catastrophic blow to Russian policies in the Balkans, which for centuries had focused on access to the "warm seas". First, it marked the end of the Balkan League, a vital arm of the Russian system of defense against Austria-Hungary. Second, the clearly pro-Serbian position Russia had been forced to take in the conflict, mainly due to the disagreements over land partitioning between Serbia and Bulgaria, caused a permanent break-up between the two countries. Accordingly, Bulgaria reverted its policy to one closer to the Central Powers' understanding over an anti-Serbian front, due to its new national aspirations, now expressed mainly against Serbia. As a result, Serbia was isolated militarily against its rival Austria-Hungary, a development that eventually doomed Serbia in the coming war a year later. Most damaging, the new situation effectively trapped Russian foreign policy: After 1913, Russia could not afford to lose its last ally in this crucial area and thus had no alternatives but to unconditionally support Serbia when the crisis between Serbia and Austria escalated in 1914. This was a position that inevitably drew Russia into an unwelcome World War with devastating results since it was less prepared (both militarily and socially) for that event than any other Great Power.

Austria-Hungary took alarm at the great increase in Serbia's territory at the expense of its national aspirations in the region, as well as Serbia's rising status, especially to Austria-Hungary's Slavic populations. This concern was shared by Germany, which saw Serbia as a satellite of Russia. These concerns contributed significantly to the two Central Powers' willingness to go to war against Serbia. This meant that when a Serbian backed organization assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, the reform-minded heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, causing the 1914 July Crisis, the conflict quickly escalated and resulted in the First World War.

كل نزاعات حروب البلقان

نزاعات حرب البلقان الأولى

المعارك البلغارية-العثمانية

| المعركة | السنة | النتيجة | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Kardzhali | 1912 | Vasil Delov | Mehmed Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Kirk Kilisse | 1912 | Radko Dimitriev | Mahmut Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Lule Burgas | 1912 | Radko Dimitriev | Abdullah Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Merhamli | 1912 | Nikola Genev | Mehmed Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Naval Battle of Kaliakra | 1912 | Dimitar Dobrev | Hüseyin Bey | Bulgarian Victory |

| First Battle of Çatalca | 1912 | Radko Dimitriev | Nazim Pasha | Indecisive[31] |

| Battle of Bulair | 1913 | Georgi Todorov | Mustafa Kemal | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Şarköy | 1913 | Stiliyan Kovachev | Enver Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Siege of Adrianople | 1913 | Georgi Vazov | Gazi Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Second Battle of Çatalca | 1913 | Vasil Kutinchev | Ahmet Pasha | Indecisive |

المعارك العثمانية-اليونانية

| المعركة | السنة | النتيجة | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Sarantaporo | 1912 | Constantine I | Hasan Pasha | نصر يوناني |

| Battle of Yenidje | 1912 | Constantine I | Hasan Pasha | نصر يوناني |

| Battle of Pente Pigadia | 1912 | Sapountzakis | عزت پاشا | نصر يوناني |

| Battle of Sorovich | 1912 | Matthaiopoulos | Hasan Pasha | نصر عثماني |

| Revolt of Himara | 1912 | Sapountzakis | عزت پاشا | نصر يوناني |

| Battle of Driskos | 1912 | Matthaiopoulos | عزت پاشا | نصر عثماني |

| Battle of Elli | 1912 | Kountouriotis | Remzi Bey | نصر يوناني |

| Capture of Korytsa | 1912 | Damianos | Davit Pasha | نصر يوناني |

| Battle of Lemnos | 1913 | Kountouriotis | رمزي بك | نصر يوناني |

| معركة بيزاني | 1913 | Constantine I | عزت پاشا | نصر يوناني |

المعارك الصربية-العثمانية

| المعركة | السنة | النتيجة | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Kumanovo | 1912 | Radomir Putnik | زكي پاشا | نصر صربي |

| Battle of Prilep | 1912 | Petar Bojović | زكي پاشا | Serbian Victory |

| Battle of Monastir | 1912 | Petar Bojović | زكي پاشا | نصر صربي |

| Siege of Scutari | 1913 | Nikola I | Hasan Pasha | Status quo ante bellum[32] |

| Siege of Adrianople | 1913 | Stepa Stepanovic | غازي پاشا | نصر صربي |

نزاعات حرب البلقان الثانية

المعارك البلغارية-اليونانية

| المعركة | التاريخ | النتيجة | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Kilkis-Lahanas | 19–21 June 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Constantine I | نصر يوناني |

| Battle of Doiran | 23 June 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Constantine I | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Demir Hisar | 26–27 June 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Constantine I | نصر بلغاري |

| Battle of Kresna Gorge | 27–31 July 1913 | Mihail Savov | Constantine I | تعادل |

المعارك البلغارية-الصربية

| المعركة | التاريخ | النتيجة | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Bregalnica | 30 June–9 July 1913 | Mihail Savov | Radomir Putnik | نصر صربي |

| Battle of Knjaževac | 4–7 July 1913 | Vasil Kutinchev | Vukoman Aračić | Bulgarian victory |

| Battle of Pirot | 6–8 July 1913 | Mihail Savov | Božidar Janković | نصر صربي |

| Battle of Belogradchik | 8 July 1913 | Mihail Savov | Božidar Janković | Serbian victory |

| Siege of Vidin | 12–18 July 1913 | Krastyu Marinov | Vukoman Aračić | معاهدة سلام |

| Battle of Kalimanci | 18–19 July 1913 | Mihail Savov | Božidar Janković | Bulgarian victory |

المعارك البلغارية-العثمانية

| المعركة | السنة | النتيجة | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Battle of Adrianople | 1913 | Mihail Savov | Enver Pasha | الهدنة الأولى |

| Ottoman Advance of Thrace | 1913 | Vulko Velchev | Ahmed Pasha | الهدنة النهائية |

المعارك البلغارية-الرومانية

| المعركة | السنة | النتيجة | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romanian Occupation of Dobruja | 1913 | Ferdinand I | Carol I of Romania | الهدنة الأولى |

| Romanian South Western Advance | 1913 | Ferdinand I | Carol I of Romania | الهدنة النهائية |

الحرب العالمية الأولى

بدأت الحرب في شبه جزيرة البلقان وتحالفت بلغاريا وتركيا مع ألمانيا والنمسا والمجر في الحرب العالمية الأولى. وبعد الحرب العالمية الأولى ضُمَّت أراضي صربيا والجبل الأسود والمناطق الواقعة إلى الشمال منهما إلى جمهورية يوغوسلافيا (السابقة).

الحرب العالمية الثانية

تحالفت كل من بلغاريا والمجر ورومانيا مع ألمانيا وإيطاليا، واحتلت بلغاريا الأراضي الصربية من يوغوسلافيا السابقة، والجزء الشمالي من اليونان. أمّا الجيوش الألمانية والإيطالية فاحتلت بقية أراضي اليونان ويوغوسلافيا، أمّا تركيا فقد بقيت محايدة معظم فترة الحرب.

ما بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية

وقعت جميع دول شبه جزيرة البلقان تحت السيطرة الشيوعية باستثناء تركيا واليونان، اللتين أصبحتا عضوين في حلف شمال الأطلسي (الناتو) وفي نهاية الثمانينيات وبداية التسعينيات من القرن العشرين الميلادي فقد الشيوعيون سيطرتهم على ألبانيا وبلغاريا، ودب الخلاف بين تركيا واليونان منذ منتصف سبعينيات القرن العشرين حول مخزون النفط الموجود في بحر إيجة. وفي عام 1991 أعلنت أربع جمهوريات ضمن يوغوسلافيا السابقة استقلالها وهي البوسنة والهرسك وكرواتيا، ومقدونيا وسلوفينيا. ودارت حرب بين الصرب من جهة وكل من كرواتيا والبوسنة والهرسك من جهة أخرى لم تضع أوزارها إلا في نهاية عام 1995، بعد أن أعيد تقسيم المنطقة وفق اتفاقيات محددة. وفي عام 999، وجه حلف شمال الأطلسي (الناتو) ضربات قوية لصربيا في محاولة لوضع حد للهجمات التي تشنها صربيا ضد مواطني إقليم كوسوفو ذوي الأصول الألبانية.

الذكرى

Citizens of Turkey regard the Balkan Wars as a major disaster (Balkan harbi faciası) in the nation's history. The Ottoman Empire lost all its European territories west of the River Maritsa as a result of the two Balkan Wars, which thus delineated present-day Turkey's western border. By 1923, only 38% of the Muslim population of 1912 still lived in the Balkans and majority of Balkan Turks had been killed or expelled.[33] The unexpected fall and sudden relinquishing of Turkish-dominated European territories created a traumatic event amongst many Turks that triggered the ultimate collapse of the empire itself within five years. Paul Mojzes has called the Balkan Wars an ''unrecognized genocide''.[34]

Nazım Pasha, Chief of Staff of the Ottoman Army, was held responsible for the failure and was assassinated on 23 January 1913 during the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état.[35]

Most Greeks regard the Balkan Wars as a period of epic achievements. They managed to liberate and gain territories that had been inhabited by Greeks since ancient times and doubled the size of the Greek Kingdom. The Greek Army, small and ill-equipped compared to the superior Ottoman but also Bulgarian and Serbian armies, won very important battles. That made Greece a viable pawn in the Great Powers' chess play. Two great personalities rose in the Greek political arena, Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, the leading mind behind the Greek foreign policy, and Crown Prince, and later King, Konstantinos I, the Major General of the Greek Army.[9][36]

انظر أيضاً

- International relations (1814–1919)

- Ottoman wars in Europe

- Serbo-Bulgarian War (1885)

- Albanian Revolt of 1910

- Albanian Revolt of 1911

- Albanian Revolt of 1912

- Destruction of the Thracian Bulgarians in 1913

- Balkans Campaign (World War I)

- Balkans Campaign (World War II)

- List of places burned during the Balkan Wars

ملاحظات

- ^ Clark 2013, pp. 45, 559.

- ^ أ ب Hall 2000.

- ^ Winston Churchill (1931). The World Crisis, 1911–1918. Thornton Butterworth. p. 278.

- ^ Biondich, Mark (20 October 2016). "The Balkan Wars: violence and nation-building in the Balkans, 1912–13". Journal of Genocide Research. 18 (4): 389–404. doi:10.1080/14623528.2016.1226019. S2CID 79322539. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ Levene, Mark (2018). ""The Bulgarians Were the Worst!" Reconsidering the Holocaust in Salonika within a Regional History of Mass Violence". The Holocaust in Greece (in الإنجليزية). Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-108-47467-2.

- ^ Farrar, L L Jr. (2003). "Aggression versus apathy: The limits of nationalism during the Balkan Wars, 1912-1913". East European Quarterly. 37 (3): 257–280. ProQuest 195176627.

- ^ Michail, Eugene (2017). "The Balkan Wars in Western Historiography, 1912–2012". The Balkan Wars from Contemporary Perception to Historic Memory (in الإنجليزية). Springer International Publishing. pp. 319–340. ISBN 978-3-319-44642-4.

- ^ Helmreich 1938.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους [History of the Hellenic Nation] (in اليونانية) (Vol. 14 ed.). Athens, Greece: Ekdotiki Athinon. 1974. ISBN 9789602131107.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ M.S. Anderson, The Eastern Question, 1774–1923: A Study in International Relations (1966) online

- ^ J. A. R. Marriott, The Eastern Question An Historical Study In European Diplomacy (1940), pp 408–63. Online

- ^ Hasan Unal, "Ottoman policy during the Bulgarian independence crisis, 1908–9: Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria at the outset of the Young Turk revolution." Middle Eastern Studies 34.4 (1998): 135–176.

- ^ Marriott, The Eastern Question An Historical Study In European Diplomacy (1940), pp 433–63.

- ^ "Military League", Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ "THE BALKAN WARS". US Library of Congress. 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Anderson, Frank Maloy; Hershey, Amos Shartle (1918). Handbook for the Diplomatic History of Europe, Asia, and Africa 1870–1914. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Hall 2000[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ "Wars of the World; First Balkan War 1912-1913". OnWar.com. December 16, 2000. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- ^ Crampton (1987) Crampton, Richard (1987). A short history of modern Bulgaria. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0521273237.

- ^ "Balkan Crises". cnparm.home.texas.net/Wars/BalkanCrises. August 14, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- ^ Hall 2000, p. 101.

- ^ Stavrianos 2000.

- ^ Stavrianos 2000, p. 539.

- ^ Mazower 2005, p. 280.

- ^ أ ب ت Hall 2000, p. 117.

- ^ George Phillipov (Winter 1995). "THE MACEDONIAN ENIGMA". Magazine: Australia &World Affairs. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars (1914). Report of the International Commission to Inquire Into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 279.

- ^ Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars, published by the Endowment Washington, D.C. 1914, p. 97–99 pp.79–95

- ^ Hall 2000, p. 121.

- ^ Stowell, Ellery Cory (2009). The Diplomacy Of The War Of 1914: The Beginnings Of The War (1915). Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-104-48758-4.

- ^ Vŭchkov, pp. 99–103

- ^ Somel, Selçuk Akşin. Historical dictionary of the Ottoman Empire. Scarecrow Press Inc. 2003. lxvi.

- ^ "Expulsion and Emigration of the Muslims from the Balkans". EGO(http://www.ieg-ego.eu) (in الألمانية). Retrieved 2021-12-22.

- ^ Mojzes, Paul (November 2013). "Ethnic cleansing in the Balkans, why did it happen and could it happen again" (PDF). Cicero Foundation: 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Gul Tokay. "Ottoman diplomacy, the Balkan Wars and the Great Powers". In Dominik Geppert, William Mulligan, Andreas Rose, eds. The Wars before the Great War ISBN 978-1-107-06347-1, 2015, p. 70

- ^ Mavrogordatos, Georgios (2015). 1915, Ο Εθνικός Διχασμός [1915, The National Division] (in اليونانية) (VIII ed.). Athens: Ekdoseis Patakis. pp. 33–35. ISBN 9789601664989.

انظر أيضا

| حروب البلقان

]].- الحروب العثمانية في اوروبا

- الحرب الصربية-البلقانية (1885)

- حملات البلقان في الحرب العالمية الأولى (1914-1918)

- حملات البلقان في الحرب العالمية الثانية (1940-1945)

- الحرب اليوغسلافية (1991-1999)

وصلات خارجية

- Project Gutenberg's The Balkan Wars: 1912-1913, by Jacob Gould Schurman

- مكتبة الكونگرس الأمريكي في حروب البلقان

- أزمات البلقان، 1903–1914

- الأزياء والشارات العسكرية في حروب البلقان

- حروب البلقان: استعراض

- The New Student's Reference Work/The Balkans and the Peace of Europe

- حقائق وملاحظات تاريخية عن مقدونيا وبلغاريا، من مؤرخين معاصرين للحروب، وقضايا الموضوعية، إلخ.

- حروب البلقان من وجهة نظر تركية

- CS1 اليونانية-language sources (el)

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from June 2020

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2020

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة from April 2020

- ثورات القرن 20

- حروب البلقان

- حروب خاضتها البلقان

- حروب خاضتها بلغاريا

- حروب خاضتها اليونان

- حرب إستقلال

- حروب خاضتها الإمبراطورية العثمانية

- حروب اوروبا

- أسباب الحرب العالمية الأولى

- نزاعات 1912

- نزاعات 1913

- 1912 في بلغاريا

- 1913 في بلغاريا

- البلقان

- حروب