إرنست هوفمان

إرنست هوفمان | |

|---|---|

| |

| وُلِد | Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann 24 يناير 1776 Königsberg, East Prussia, Kingdom of Prussia |

| توفي | 25 يونيو 1822 (aged 46) Berlin, Brandenburg, Kingdom of Prussia |

| الاسم الأدبي | E. T. A. Hoffmann |

| الوظيفة | Jurist, author, composer, music critic, artist |

| العرق | Prussian |

| الفترة | 1809–1822 |

| الصنف الأدبي | Fantasy |

| الحركة الأدبية | Romanticism |

| التوقيع |  |

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (commonly abbreviated as E. T. A. Hoffmann; born Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann; 24 January 1776 – 25 June 1822) was a German Romantic author of fantasy and Gothic horror, a jurist, composer, music critic and artist.[1][2][3] His stories form the basis of Jacques Offenbach's opera The Tales of Hoffmann, in which Hoffmann appears (heavily fictionalized) as the hero. He is also the author of the novella The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, on which Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker is based. The ballet Coppélia is based on two other stories that Hoffmann wrote, while Schumann's Kreisleriana is based on Hoffmann's character Johannes Kreisler.

Hoffmann's stories highly influenced 19th-century literature, and he is one of the major authors of the Romantic movement.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

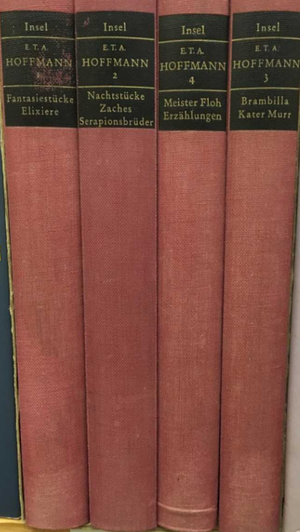

Works

Literary

- Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier (collection of previously published stories, 1814)[4]

- "Ritter Gluck", "Kreisleriana", "Don Juan", "Nachricht von den neuesten Schicksalen des Hundes Berganza"

- "Der Magnetiseur", "Der goldne Topf" (revised in 1819), "Die Abenteuer der Silvesternacht"

- Die Elixiere des Teufels (1815)

- Nachtstücke (1817)

- "Der Sandmann", "Das Gelübde", "Ignaz Denner", "Die Jesuiterkirche in G."

- "Das Majorat", "Das öde Haus", "Das Sanctus", "Das steinerne Herz"

- Seltsame Leiden eines Theater-Direktors (1819)

- Klein Zaches, genannt Zinnober (1819)

- Die Serapionsbrüder (1819)

- "Der Einsiedler Serapion", "Rat Krespel", "Die Fermate", "Der Dichter und der Komponist"

- "Ein Fragment aus dem Leben dreier Freunde", "Der Artushof", "Die Bergwerke zu Falun", "Nußknacker und Mausekönig" (1816)

- "Der Kampf der Sänger", "Eine Spukgeschichte", "Die Automate", "Doge und Dogaresse"

- "Alte und neue Kirchenmusik", "Meister Martin der Küfner und seine Gesellen", "Das fremde Kind"

- "Nachricht aus dem Leben eines bekannten Mannes", "Die Brautwahl", "Der unheimliche Gast"

- "Das Fräulein von Scuderi", "Spielerglück" (1819), "Der Baron von B."

- "Signor Formica", "Zacharias Werner", "Erscheinungen"

- "Der Zusammenhang der Dinge", "Vampirismus", "Die ästhetische Teegesellschaft", "Die Königsbraut"

- Prinzessin Brambilla (1820)

- Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (1820)

- "Die Irrungen" (1820)

- "Die Geheimnisse" (1821)

- "Die Doppeltgänger" (1821)

- Meister Floh (1822)

- "Des Vetters Eckfenster" (1822)

- Letzte Erzählungen (1825)

Musical

Vocal music

- Messa d-moll (1805)

- Trois Canzonettes à 2 et à 3 voix (1807)

- 6 Canzoni per 4 voci alla capella (1808)

- Miserere b-moll (1809)

- In des Irtisch weiße Fluten (Kotzebue), Lied (1811)

- Recitativo ed Aria „Prendi l’acciar ti rendo" (1812)

- Tre Canzonette italiane (1812); 6 Duettini italiani (1812)

- Nachtgesang, Türkische Musik, Jägerlied, Katzburschenlied für Männerchor (1819–21)

Works for stage

- Die Maske (libretto by Hoffmann), Singspiel (1799)

- Die lustigen Musikanten (libretto: Clemens Brentano), Singspiel (1804)

- Incidental music to Zacharias Werner's tragedy Das Kreuz an der Ostsee (1805)

- Liebe und Eifersucht (libretto by Hoffmann after Calderón, translated by August Wilhelm Schlegel) (1807)

- Arlequin, ballet (1808)

- Der Trank der Unsterblichkeit (libretto: Julius von Soden), romantic opera (1808)

- Wiedersehn! (libretto by Hoffmann), prologue (1809)

- Dirna (libretto: Julius von Soden), melodrama (1809)

- Incidental music to Julius von Soden's drama Julius Sabinus (1810)

- Saul, König von Israel (libretto: Joseph von Seyfried), melodrama (1811)

- Aurora (libretto: Franz von Holbein), heroic opera (1812)

- Undine (libretto: Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué), Zauberoper (1816)

- Der Liebhaber nach dem Tode (unfinished)

Instrumental

- Rondo für Klavier (1794/95)

- Ouvertura. Musica per la chiesa d-moll (1801)

- Klaviersonaten: A-Dur, f-moll, F-Dur, f-moll, cis-moll (1805–1808)

- Große Fantasie für Klavier (1806)

- Sinfonie Es-Dur (1806)

- Harfenquintett c-moll (1807)

- Grand Trio E-Dur (1809)

- Walzer zum Karolinentag (1812)

- Teutschlands Triumph in der Schlacht bei Leipzig, (by "Arnulph Vollweiler", 1814; lost)

- Serapions-Walzer (1818–1821)

Assessment

Hoffmann is one of the best-known representatives of German Romanticism, and a pioneer of the fantasy genre, with a taste for the macabre combined with realism that influenced such authors as Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), Nikolai Gogol[5][6](1809–1852), Charles Dickens (1812–1870), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), George MacDonald (1824–1905),[7] Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881), Vernon Lee (1856-1935),[8] Franz Kafka (1883–1924) and Alfred Hitchcock (1899–1980). Hoffmann's story Das Fräulein von Scuderi is sometimes cited as the first detective story and a direct influence on Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue".[9]

The twentieth-century Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin characterised Hoffmann's works as Menippea, essentially satirical and self-parodying in form, thus including him in a tradition that includes Cervantes, Diderot and Voltaire.

Robert Schumann's piano suite Kreisleriana (1838) takes its title from one of Hoffmann's books (and according to Charles Rosen's The Romantic Generation, is possibly also inspired by "The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr", in which Kreisler appears). Jacques Offenbach's masterwork, the opera Les contes d'Hoffmann ("The Tales of Hoffmann", 1881), is based on the stories, principally "Der Sandmann" ("The Sandman", 1816), "Rat Krespel" ("Councillor Krespel", 1818), and "Das verlorene Spiegelbild" ("The Lost Reflection") from Die Abenteuer der Silvester-Nacht (The Adventures of New Year's Eve, 1814). Klein Zaches genannt Zinnober (Little Zaches called Cinnabar, 1819) inspired an aria as well as the operetta Le Roi Carotte, 1872). Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker (1892) is based on "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King", and the ballet Coppélia, with music by Delibes, is based on two eerie Hoffmann stories.

Hoffmann also influenced 19th-century musical opinion directly through his music criticism. His reviews of Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1808) and other important works set new literary standards for writing about music, and encouraged later writers to consider music as "the most Romantic of all the arts."[10] Hoffmann's reviews were first collected for modern readers by Friedrich Schnapp, ed., in E.T.A. Hoffmann: Schriften zur Musik; Nachlese (1963) and have been made available in an English translation in E.T.A. Hoffmann's Writings on Music, Collected in a Single Volume (2004).

Hoffmann strove for artistic polymathy. He created far more in his works than mere political commentary achieved through satire. His masterpiece novel Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr, 1819–1821) deals with such issues as the aesthetic status of true artistry and the modes of self-transcendence that accompany any genuine endeavour to create. Hoffmann's portrayal of the character Kreisler (a genius musician) is wittily counterpointed with the character of the tomcat Murr – a virtuoso illustration of artistic pretentiousness that many of Hoffmann's contemporaries found offensive and subversive of Romantic ideals.

Hoffmann's literature indicates the failings of many so-called artists to differentiate between the superficial and the authentic aspects of such Romantic ideals. The self-conscious effort to impress must, according to Hoffmann, be divorced from the self-aware effort to create. This essential duality in Kater Murr is conveyed structurally through a discursive 'splicing together' of two biographical narratives.

Science fiction

While disagreeing with E. F. Bleiler's claim that Hoffman was "one of the two or three greatest writers of fantasy", Algis Budrys of Galaxy Science Fiction said that he "did lay down the groundwork for some of our most enduring themes".[11]

Historian Martin Willis argues that Hoffmann's impact on science fiction has been overlooked, saying "his work reveals a writer dynamically involved in the important scientific debates of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries." Willis points out that Hoffmann's work is contemporary with Frankenstein (1818) and with "the heated debates and the relationship between the new empirical science and the older forms of natural philosophy that held sway throughout the eighteenth century." His "interest in the machine culture of his time is well represented in his short stories, of which the critically renowned The Sandman (1816) and Automata (1814) are the best examples. ...Hoffmann's work makes a considerable contribution to our understanding of the emergence of scientific knowledge in the early years of the nineteenth century and to the conflict between science and magic, centred mainly on the 'truths' available to the advocates of either practice. ...Hoffmann's balancing of mesmerism, mechanics, and magic reflects the difficulty in categorizing scientific knowledge in the early nineteenth century."[12]

In popular culture

- Robertson Davies invokes Hoffmann as a character (with the pet name of 'ETAH') trapped in Limbo, within his novel The Lyre of Orpheus (1988).

- Angela Carter – The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman (1972)

- Alexandre Dumas, père translated The Nutcracker into French, which aided in making the tale popular and widespread.

- The exotic and supernatural elements in the storyline of Ingmar Bergman's 1982 film Fanny and Alexander derive largely from the stories of Hoffmann.[بحاجة لمصدر]

- Andrei Tarkovsky wrote a script titled Hoffmaniana in which the writer himself is the main protagonist. Due to Tarkovsky's premature death, the film was never made.[بحاجة لمصدر]

- Freud gives an extensive psychoanalytic analysis of Hoffmann's "The Sandman" in his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche.

- Coppelius is a German classical metal band whose name is taken from a character in Hoffmann's "The Sandman". The band's 2010 album Zinnober includes a track titled "Klein Zaches".[13][بحاجة لمصدر]

- The Russian show Kukly was cancelled by government officials after an episode in which Vladimir Putin was portrayed as Hoffmann's Klein Zaches.[14][بحاجة لمصدر]

- Malifaux, a tabletop skirmish game, uses the names Hoffman and Coppelius from "The Sandman" for characters which reference each other as having an "unexplained connection".

- Dario Argento was planning to film an adaptation of "The Sandman" based on Hoffmann's short story and starring Iggy Pop but filming never commenced.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

See also

- The Tales of Hoffmann

- The Tales of Hoffmann (film)

- Gofmaniada, a Russian puppet-animated feature film about Hoffmann and several of his stories.

المراجع

- ^ Penrith Goff, "E.T.A. Hoffmann" in E. F. Bleiler, Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror. New York: Scribner's, 1985. pp. 111–120. ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ^ Mike Ashley, "Hoffmann, E(rnst) T(heodor) A(madeus) ", in St. James Guide to Horror, Ghost, and Gothic Writers, ed. David Pringle. Detroit: St. James Press/Gale, 1998. ISBN 9781558622067 (pp. 668-69).

- ^ "Ludwig Tieck, Heinrich von Kleist, and E. T. A. Hoffmann also profoundly influenced the development of European Gothic horror in the nineteenth century...." Heide Crawford, The Origins of the Literary Vampire. Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, 2016. ISBN 9781442266742 (p. xiii).

- ^ "Fantasy pieces in the manner of Jacques Callot"

- ^ Krys Svitlana, “Intertextual Parallels Between Gogol' and Hoffmann: A Case Study of Vij and The Devil’s Elixirs.” Canadian-American Slavic Studies (CASS) 47.1 (2013): 1-20. (20 pages)

- ^ Krys Svitlana, “Allusions to Hoffmann in Gogol’s Ukrainian Horror Stories from the Dikan'ka Collection.” Canadian Slavonic Papers: Special Issue, devoted to the 200th anniversary of Nikolai Gogol'’s birth (1809–1852) 51.2-3 (June–September 2009): 243-266. (23 pages)

- ^ Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife London: Allen and Unwin, 1924 (p. 297-8).

- ^ "Another major influence for Lee is unmistakably E.T.A. Hoffmann's Der Sandmann..." Christa Zorn, Vernon Lee : aesthetics, history, and the Victorian female intellectual. Athens : Ohio University Press, 2003. ISBN 0821414976 (p. 142).

- ^ The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker, Continuum, 2004, page 507

- ^ See also Fausto Cercignani, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Italien und die romantische Auffassung der Musik, in S. M. Moraldo (ed.), Das Land der Sehnsucht. E. T. A. Hoffmann und Italien, Heidelberg, Winter, 2002, S. 191–201.

- ^ Budrys, Algis (يوليو 1968). "Galaxy Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 161–167.

- ^ Martin Willis (2006). Mesmerists, Monsters, and Machines: Science Fiction and the Cultures of Science in the Nineteenth Century. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. pp. 29–30.

- ^ Review of Zinnober, http://www.ice-vajal.com/c/CD/coppelius.htm

- ^ "New Cartoon Show Puts Putin Among Men" http://www.ekaterinburg.com/news/print/news_id-316222.html

وصلات خارجية

- Hoffmann's Life and Opinions of the Tom Cat Murr

- أعمال من إرنست هوفمان في مشروع گوتنبرگ

- Works by or about إرنست هوفمان at Internet Archive

- Works by إرنست هوفمان at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- أعمال موسيقية مجانية من إرنست هوفمان في مكتبة الأعمال الكورالية المشاع (ChoralWiki)

- Compositions of E. T. A. Hoffmann in the digitale collection of the Bamberg State Library

- E. T. A. Hoffmann entry in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy

قالب:E. T. A. Hoffmann قالب:The Nutcracker قالب:Mademoiselle de Scuderi

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2011

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2013

- Use dmy dates from July 2012

- E. T. A. Hoffmann

- 1776 births

- 1822 deaths

- 18th-century classical composers

- 18th-century German musicians

- 18th-century German people

- مؤلفون موسيقيون كلاسيكيون في القرن 19

- 19th-century German musicians

- Composers for harp

- وفيات بالزهري

- German classical composers

- German fantasy writers

- German horror writers

- German male classical composers

- German male novelists

- German male short story writers

- German short story writers

- German music critics

- German Romantic composers

- كتاب صانعو أساطير

- أشخاص من كونيگسبرگ

- Romanticism

- خريجو جامعة كونيگزبرگ

- Writers of Gothic fiction

- 19th-century male musicians