سوريا تحت حكم حزب البعث

الجمهورية العربية السورية | |

|---|---|

| 1963–2024 | |

الشعار الحادي: وَحْدَةٌ، حُرِّيَّةٌ، اِشْتِرَاكِيَّةٌ | |

النشيد: حُمَاةَ الدِّيَارِ" | |

سوريا باللون الأخضر الداكن، المطالبات الإقليمية لسوريا على محافظة هاتاي التركية وهضبة الجولان المحتلة من قبل إسرائيل باللون الأخضر الفاتح | |

| العاصمة و أكبر مدينة | دمشق 33°30′N 36°18′E / 33.500°N 36.300°E |

| اللغات الرسمية | العربية[1] |

| الجماعات العرقية | 90% عرب 9% أكراد 1% أخرى |

| الدين (2024)[2] | |

| صفة المواطن | سوري |

| الحكومة | جمهورية رئاسية مركزية بعثية جديدة[5]

|

| الرئيس | |

• 1963 | لؤي الأتاسي |

• 1963–1966 | أمين الحافظ |

• 1966–1970 | نور الدين الأتاسي |

• 1970–1971 | أحمد الخطيب (بالإنابة) |

• 1971–2000 | حافظ الأسد |

• 2000 | عبد الحليم خدام (بالإنابة) |

• 2000–2024 | بشار الأسد |

| رئيس الوزراء | |

• 1963 (الأول) | خالد العظم |

• 2024 (الأخير) | محمد غازي الجلالي |

| نائب رئيس سوريا | |

• 1963–1964 (الأول) | محمد عمران |

• 2006–2024 (الأخير) | نجاح العطار |

• 2024 (الأخير) | فيصل مقداد |

| التشريع | مجلس الشعب |

| الحقبة التاريخية | |

| 8 مارس 1963 | |

| 21–23 فبراير 1966 | |

| 13 نوفمبر 1970 | |

| 6–25 أكتوبر 1973 | |

| 1976–1982 | |

| 2000–2001 | |

| 2011–2024 | |

| 8 ديسمبر 2024 | |

| المساحة | |

• الإجمالية | 185.180[7] km2 (71.498 sq mi) (رقم 87) |

• الماء (%) | 1.1 |

| التعداد | |

• تقدير 2024 | ▲ 25.000.753[8] (رقم 57) |

• الكثافة | 118.3/km2 (306.4/sq mi) (رقم 70) |

| ن.م.إ. (ق.ش.م.) | تقدير 2015 |

• الإجمالي | 50.28 بليون دولار [9] |

• للفرد | 2.900 دولار [9] |

| ن.م.إ. (الإسمي) | تقدير 2020 |

• الإجمالي | 11.08 بليون دولار [9] |

• للفرد | 533 دولار |

| جيني (2022) | 26.6[10] low |

| م.ت.ب. (2022) | 0.557[11] medium · رقم 157 |

| العملة | الليرة السورية (SYP) |

| التوقيت | التوقيت المحلي |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +963 |

| كود آيزو 3166 | SY |

| النطاق العلوي للإنترنت | .sy سوريا. |

| اليوم جزء من | سوريا |

سوريا تحت حكم حزب البعث، رسمياً الجمهورية العربية السورية، هي دولة كانت قائمة بين عام 1963 و2024 تحت حكم حزب البعث الاشتراكي. إلى جانب العراق من عام 1968 حتى 2003، كانت واحدة من دولتين بعثيتين موجودتين. حكمت عائلة الأسد سوريا من عام 1971 حتى هجمات المعارضة السورية عام 2024، وسقوط النظام.

نشأت الدولة في أعقاب الانقلاب السوري 1963 وقادها ضباط عسكريون علويون، وأطاح حافظ الأسد بالرئيس صلاح جديد في الحركة التصحيحية عام 1970. أدت المقاومة ضد حكم الأسد إلى مذبحة حماة 1982. توفي حافظ الأسد عام 2000 وخلفه نجله بشار الأسد. أدت الاحتجاجات ضد حكم الأسد عام 2011 أثناء ثورات الربيع العربي إلى الحرب الأهلية السورية، مما أضعف الحكم الإقليمي للحكومة البعثية. في ديسمبر 2024، بلغت سلسلة من الهجمات المفاجئة التي شنتها فصائل معارضة مختلفة ذروتها في انهيار النظام. وأفادت روسيا أن الأسد فر إلى موسكو وحصل على اللجوء السياسي.[12]

التاريخ

انقلاب 1963

After the 1961 coup that terminated the political union between Egypt and Syria, the instability which followed eventually culminated in the 8 March 1963 Ba'athist coup. The takeover was engineered by members of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party, led by Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar. The new Syrian cabinet was dominated by Ba'ath members.[13][14] Since the 1963 seizure of power by its Military Committee, the Ba'ath party ruled Syria as a totalitarian state. Ba'athists took control over country's politics, education, culture, religion and surveilled all aspects of civil society through its powerful Mukhabarat (secret police). Syrian Arab Armed forces and secret police were integrated with the Ba'ath party apparatus; after the purging of traditional civilian and military elites by the new regime.[15]

The 1963 Ba'athist coup marked a "radical break" in modern Syrian history, after which Ba'ath party monopolised power in the country to establish a one-party state and shaped a new socio-political order by enforcing its state ideology.[16]

انقلاب 1966

On 23 February 1966, the neo-Ba'athist Military Committee carried out an intra-party rebellion against the Ba'athist Old Guard (Aflaq and Bitar), imprisoned President Amin al-Hafiz and designated a regionalist, civilian Ba'ath government on 1 March.[14] Although Nureddin al-Atassi became the formal head of state, Salah Jadid was Syria's effective ruler from 1966 until November 1970,[17] when he was deposed by Hafiz al-Assad, who at the time was Minister of Defense.[18]

The coup led to the schism within the original pan-Arab Ba'ath Party: one Iraqi-led ba'ath movement (ruled Iraq from 1968 to 2003) and one Syrian-led ba'ath movement was established. In the first half of 1967, a low-key state of war existed between Syria and Israel. Conflict over Israeli cultivation of land in the Demilitarized Zone led to 7 April pre-war aerial clashes between Israel and Syria.[19] When the Six-Day War broke out between Egypt and Israel, Syria joined the war and attacked Israel as well. In the final days of the war, Israel turned its attention to Syria, capturing two-thirds of the Golan Heights in under 48 hours.[20] The defeat caused a split between Jadid and Assad over what steps to take next.[21] Disagreement developed between Jadid, who controlled the party apparatus, and Assad, who controlled the military. The 1970 retreat of Syrian forces sent to aid the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) led by Yasser Arafat during the "Black September" (also known as the Jordan Civil War of 1970) hostilities with Jordan reflected this disagreement.[22]

حافظ الأسد (1970–2000)

The power struggle culminated in the November 1970 Syrian Corrective movement, a bloodless military coup that removed Jadid and installed Hafiz al-Assad as the strongman of the government.[18] General Hafiz al-Assad transformed a neo-Ba'athist party state into a totalitarian dictatorship marked by his pervasive grip on the party, armed forces, secret police, media, education sector, religious and cultural spheres and all aspects of civil society. He assigned Alawite loyalists to key posts in the military forces, bureaucracy, intelligence and the ruling elite. A cult of personality revolving around Hafiz and his family became a core tenet of Ba'athist ideology,[23] which espoused that Assad dynasty was destined to rule perennially.[24] On 6 October 1973, Syria and Egypt initiated the Yom Kippur War against Israel. The Israel Defense Forces reversed the initial Syrian gains and pushed deeper into Syrian territory.[25] The village of Quneitra was largely destroyed by the Israeli army. In the late 1970s, an Islamist uprising by the Muslim Brotherhood was aimed against the government. Islamists attacked civilians and off-duty military personnel, leading security forces to also kill civilians in retaliatory strikes. The uprising had reached its climax in the 1982 Hama massacre,[26] when more than 40,000 people were killed by Syrian military troops and Ba'athist paramilitaries.[27][28] It has been described as the "single deadliest act" of violence perpetrated by any state upon its own population in modern Arab history[27][28]

In a major shift in relations with both other Arab states and the Western world, Syria participated in the United States-led Gulf War against Saddam Hussein. The country participated in the multilateral Madrid Conference of 1991, and during the 1990s engaged in negotiations with Israel along with Palestine and Jordan. These negotiations failed, and there have been no further direct Syrian-Israeli talks since President Hafiz al-Assad's meeting with then President Bill Clinton in Geneva in 2000.[29]

بشار الأسد (2000–2024)

Hafez al-Assad died on 10 June 2000. His son, Bashar al-Assad, was elected president in an election in which he ran unopposed.[13] His election saw the birth of the Damascus Spring and hopes of reform, but by autumn 2001, the authorities had suppressed the movement, imprisoning some of its leading intellectuals.[30] Instead, reforms have been limited to some market reforms.[23][31][32] On 5 October 2003, Israel bombed a site near Damascus, claiming it was a terrorist training facility for members of Islamic Jihad.[33] In March 2004, Syrian Kurds and Arabs clashed in the northeastern city of al-Qamishli. Signs of rioting were seen in the cities of Qamishli and Hasakeh.[34] In 2005, Syria ended its military presence in Lebanon.[35] Assassination of Rafic Hariri in 2005 led to international condemnation and triggered a popular Intifada in Lebanon, known as "the Cedar Revolution" which forced the Assad regime to end its 29-year old of military occupation in Lebanon.[36] On 6 September 2007, foreign jet fighters, suspected as Israeli, reportedly carried out Operation Orchard against a suspected nuclear reactor under construction by North Korean technicians.[37]

الحرب الأهلية

The Syrian civil war began in 2011 as a part of the wider Arab Spring, a wave of upheaval throughout the Arab World. Public demonstrations across Syria began on 26 January 2011 and developed into a nationwide uprising. Protesters demanded the resignation of President Bashar al-Assad, the overthrow of his government, and an end to nearly five decades of Ba’ath Party rule. Since spring 2011, the Syrian government deployed the Syrian Army to quell the uprising, and several cities were besieged,[38][39] though the unrest continued. According to some witnesses, soldiers, who refused to open fire on civilians, were summarily executed by the Syrian Army.[40] The Syrian government denied reports of defections, and blamed armed gangs for causing trouble.[41] Since early autumn 2011, civilians and army defectors began forming fighting units, which began an insurgency campaign against the Syrian Army. The insurgents unified under the banner of the Free Syrian Army and fought in an increasingly organized fashion; however, the civilian component of the armed opposition lacked an organized leadership.[42]

The uprising has sectarian undertones, though neither faction in the conflict has described sectarianism as playing a major role. The opposition is dominated by Sunni Muslims, whereas the leading government figures are Alawites,[42] affiliated with Shia Islam. As a result, the opposition is winning support from the Sunni Muslim states, whereas the government is publicly supported by the Shia dominated Iran and the Lebanese Hezbollah. According to various sources, including the United Nations, up to 13,470–19,220 people have been killed, of which about half were civilians, but also including 6,035–6,570 armed combatants from both sides[43][44][45][46] and up to 1,400 opposition protesters.[47] Many more have been injured, and tens of thousands of protesters have been imprisoned. According to the Syrian government, 9,815–10,146 people, including 3,430 members of the security forces, 2,805–3,140 insurgents and up to 3,600 civilians, have been killed in fighting with what they characterize as "armed terrorist groups."[48] To escape the violence, tens of thousands of Syrian refugees have fled the country to neighboring Jordan, Iraq and [49] Lebanon, as well to Turkey.[50] The total official UN numbers of Syrian refugees reached 42,000 at the time,[51] while unofficial number stood at as many as 130,000.

UNICEF reported that over 500 children have been killed in the 11 months until February 2012,[52][53] Another 400 children have been reportedly arrested and tortured in Syrian prisons.[54][55] Both claims have been contested by the Syrian government.[56] Additionally, over 600 detainees and political prisoners have died under torture.[57] Human Rights Watch accused the government and Shabiha of using civilians as human shields when they advanced on opposition held-areas.[58] Anti-government rebels have been accused of human rights abuses as well, including torture, kidnapping, unlawful detention and execution of civilians, Shabiha and soldiers.[42] HRW also expressed concern at the kidnapping of Iranian nationals.[59] The UN Commission of Inquiry has also documented abuses of this nature in its February 2012 report, which also includes documentation that indicates rebel forces have been responsible for displacement of civilians.[60]

Being ranked 8th last on the 2024 Global Peace Index and 4th worst in the 2024 Fragile States Index,[61] Syria is one of the most dangerous places for journalists. Freedom of press is extremely limited, and the country is ranked 2nd worst in the 2024 World Press Freedom Index.[62][63] Syria is the most corrupt country in the Middle East[64][65] and was ranked the 2nd lowest globally on the 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index.[66] The country has also become the epicentre of a state-sponsored multi-billion dollar illicit drug cartel, the largest in the world.[67][68][69][70] The civil war has resulted in more than 600,000 deaths,[71] with pro-Assad forces causing more than 90% of the total civilian casualties.[أ] The war led to a massive refugee crisis, with an estimated 7.6 million internally displaced people (July 2015 UNHCR figure) and over 5 million refugees (July 2017 registered by UNHCR).[80] The war has also worsened economic conditions, with more than 90% of the population living in poverty and 80% facing food insecurity.[ب]

The Arab League, the United States, the European Union states, the Gulf Cooperation Council states, and other countries have condemned the use of violence against the protesters.[42] China and Russia have avoided condemning the government or applying sanctions, saying that such methods could escalate into foreign intervention. However, military intervention has been ruled out by most countries.[85][86][87] The Arab League suspended Syria's membership over the government's response to the crisis,[88] but sent an observer mission in December 2011, as part of its proposal for peaceful resolution of the crisis.[87] The latest attempts to resolve the crisis had been made through the appointment of Kofi Annan, as a special envoy to resolve the Syrian crisis in the Middle East.[42] Some analysts however have posited the partitioning the region into a Sunnite east, Kurdish north and Shiite/Alawite west.[89]

جمود الصراع (2020–2024)

اعتبارًا من عام 2020، أصبح الصراع في حالة جمود.[90] على الرغم من سيطرة قوات المعارضة على ما يقرب من 30% من البلاد، إلا أن القتال العنيف توقف إلى حد كبير وكان هناك اتجاه إقليمي متزايد نحو تطبيع العلاقات مع نظام بشار الأسد.[90]

سقوط نظام الأسد (2024)

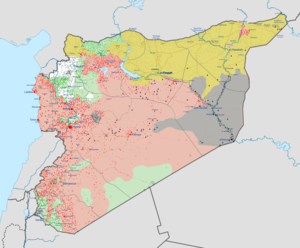

الأراضي تحت سيطرة قوات سوريا الديمقراطية (بالأصفر)، داعش (بالرمادي)، الجيش السوري (بالأحمر)، الجيش الوطني السوري وتركيا (الأخضر الفاتح)، غرفة العمليات الجنوبية (بالوردي)، هيئة تحرير الشام (بالأبيض)، جيش مغاوير الثورة والولايات المتحدة (بالأخضر المزرق).

في 27 نوفمبر 2024، اندلعت أعمال العنف مرة أخرى. سيطرت فصائل المعارضة بقيادة هيئة تحرير الشام الإسلامية والجيش الوطني السوري المدعوم من تركيا على حلب، مما دفع الرئيس السوري بشار الأسد، بدعم من روسيا، إلى شن حملة غارات جوية انتقامية. أسفرت الضربات التي استهدفت المراكز السكانية والعديد من المستشفيات في مدينة إدلب التي تسيطر عليها المقاومة، عن مقتل 25 شخصًا على الأقل، وفقًا لمجموعة الخوذ البيضاء التطوعية. أصدرت دول حلف الناتو بيانًا مشتركًا يدعو إلى حماية المدنيين والبنية التحتية الحيوية لمنع المزيد من النزوح وضمان وصول المساعدات الإنسانية. وشددوا على الحاجة الملحة إلى حل سياسي بقيادة سورية، وفقًا لقرار مجلس الأمن التابع للأمم المتحدة رقم 2254، الذي يدعو إلى الحوار بين الحكومة السورية وقوات المعارضة. واستمرت هجمات المعارضة في 27 نوفمبر 2024، وواصلت تقدمها في محافظة حماة بعد سيطرتها على حلب.[91][92][93]

في 29 نوفمبر، تخلت قوات المقاومة التابعة الجبهة الجنوبية عن جهود المصالحة مع الحكومة السورية وشنت هجوماً في الجنوب، أملاً في تنفيذ حركة كماشة على دمشق.[94][95]

في 4 ديسمبر 2024، اندلعت اشتباكات عنيفة في محافظة حماة، حيث اشتبك الجيش السوري مع المقاومة بقيادة إسلاميين في محاولة لوقف تقدمها نحو مدينة حماة الرئيسية. وزعمت القوات الحكومية أنها شنت هجومًا مضادًا بدعم جوي، مما دفع فصائل المقاومة، بما في ذلك هيئة تحرير الشام، إلى التراجع على بعد ستة أميال من المدينة. ومع ذلك، وعلى الرغم من التعزيزات، استولت المقاومة على المدينة في 5 ديسمبر.[96] وأدى القتال إلى نزوح واسع النطاق، حيث فر ما يقرب من 50.000 شخص من المنطقة، وأفادت التقارير عن سقوط أكثر من 600 شخص، بما في ذلك 104 مدنياً.[97]

في مساء 6 ديسمبر 2024، سيطرت قوات الجبهة الجنوبية على مدينة السويداء، في جنوب سوريا، بعد انسحاب القوات الموالية للحكومة من المدينة.[98][99] في الوقت نفسه، تمكنت قوات سوريا الديمقراطية بقيادة كردية من الاستيلاء على مدينة دير الزور من القوات الموالية للحكومة، والتي غادرت أيضًا مدينة تدمر في وسط محافظة حمص.[100][101] بحلول منتصف الليل، سيطرت قوات المعارضة في محافظة درعا الجنوبية على عاصمتها درعا، بالإضافة إلى 90% من المحافظة، بينما انسحبت القوات الموالية للحكومة باتجاه العاصمة دمشق.[102] في هذه الأثناء، سيطر جيش مغاوير الثورة، وهي جماعة معارضة مختلفة تدعمها الولايات المتحدة، على تدمر في هجوم أطلق من منطقة خفض التصعيد في التنف.[103]

في 7 ديسمبر 2024، انسحبت القوات الموالية للحكومة من محافظة القنيطرة، التي تحد هضبة الجولان المحتلة من قبل إسرائيل.[104] في ذلك اليوم، ساعد الجيش الإسرائيلي قوة الأمم المتحدة لمراقبة فض الاشتباك في صد هجوم.[105]

في 7 ديسمبر 2024، دخلت الجبهة الجنوبية ضواحي دمشق، التي تعرضت في الوقت نفسه لهجوم من الشمال من قبل الجيش السوري الحر. ومع تقدم المقاومة، فر الأسد من دمشق إلى موسكو، حيث منحه الرئيس الروسي ڤلاديمير پوتن اللجوء السياسي.[106][بحاجة لمصادر إضافية] في اليوم التالي، 8 ديسمبر، استولت قوات المعارضة السورية على مدينتي حمص ودمشق. وبعد سقوط دمشق، انهارت الجمهورية العربية السورية، وشكل رئيس الوزراء محمد غازي الجلالي حكومة انتقالية سورية بإذن من المعارضة.[107]

السياسة والحكومة

Since the 1963 seizure of power by its neo-Ba'athist Military Committee until the fall of the Assad regime in 2024, the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party governed Syria as a totalitarian police state.[ت] After a period of intra-party strife, Hafez al-Assad gained control of the party following the 1970 coup d'état and his family dominated the country's politics.[2][108][109]

After Ba'athist Syria's adoption of a new constitution in 2012, its political system operated in the framework of a presidential state[110] that nominally permitted the candidacy of individuals who were not part of the Ba'athist-controlled National Progressive Front founded in 1972.[111][112] In practice, Ba'athist Syria remained a one-party state, which banned any independent or opposition political activity.[113][114]

السلطة القضائية

There was no independent judiciary in the Syrian Arab Republic, since all judges and prosecutors were required to be Ba'athist appointees.[115] Syria's judicial branches included the Supreme Constitutional Court, the High Judicial Council, the Court of Cassation, and the State Security Courts. The Supreme State Security Court (SSSC) was abolished by President Bashar al-Assad by legislative decree No. 53 on 21 April 2011.[116] Syria had three levels of courts: courts of first instance, courts of appeals, and the constitutional court, the highest tribunal. Religious courts handled questions of personal and family law.[117]

Article 3(2) of the 1973 constitution declared Islamic jurisprudence a main source of legislation. The judicial system had elements of Ottoman, French, and Islamic laws. The Personal Status Law 59 of 1953 (amended by Law 34 of 1975) was essentially a codified sharia;[118] the Code of Personal Status was applied to Muslims by sharia courts.[119]

الانتخابات

Elections were conducted through a sham process; characterised by wide-scale rigging, repetitive voting and absence of voter registration and verification systems.[120][121][122] Parliamentary elections were held on 13 April 2016 in the government-controlled areas of Syria, for all 250 seats of Syria's unicameral legislature, the Majlis al-Sha'ab, or the People's Council of Syria.[123] Even before results had been announced, several nations, including Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom, declared their refusal to accept the results, largely citing it "not representing the will of the Syrian people."[124] However, representatives of the Russian Federation have voiced their support of this election's results. Various independent observers and international organizations denounced the Assad regime's electoral conduct as a scam; with the United Nations condemning it as illegitimate elections with "no mandate".[125][126][127][128] Electoral Integrity Project's 2022 Global report designated Syrian elections as a "facade" with the worst electoral integrity in the world alongside Comoros and Central African Republic.[129][130]قالب:Claer

انظر أيضاً

الهوامش

- ^ Sources:[72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79]

- ^ [81][82][83][84]

- ^ Sources describing Syria as a totalitarian state:

- Khamis, B. Gold, Vaughn, Sahar, Paul, Katherine (2013). "22. Propaganda in Egypt and Syria's "Cyberwars": Contexts, Actors, Tools, and Tactics". In Auerbach, Castronovo, Jonathan, Russ (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-976441-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wieland, Carsten (2018). "6: De-neutralizing Aid: All Roads Lead to Damascus". Syria and the Neutrality Trap: The Dilemmas of Delivering Humanitarian Aid Through Violent Regimes. London: I. B. Tauris. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7556-4138-3.

- Meininghaus, Esther (2016). "Introduction". Creating Consent in Ba'thist Syria: Women and Welfare in a Totalitarian State. I. B. Tauris. pp. 1–33. ISBN 978-1-78453-115-7.

- Sadiki, Larbi; Fares, Obaida (2014). "12: The Arab Spring Comes to Syria: Internal Mobilization for Democratic Change, Militarization and Internationalization". Routledge Handbook of the Arab Spring: Rethinking Democratization. Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-415-52391-2.

- Khamis, B. Gold, Vaughn, Sahar, Paul, Katherine (2013). "22. Propaganda in Egypt and Syria's "Cyberwars": Contexts, Actors, Tools, and Tactics". In Auerbach, Castronovo, Jonathan, Russ (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-976441-9.

المصادر

- ^ "Constitution of the Syrian Arab Republic – 2012" (PDF). International Labour Organization. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت "Syria: People and society". The World Factbook. CIA. 10 May 2022. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "CIA - The World Factbook" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ "Syria (10/03)".

- ^ "Syria's Religious, Ethnic Groups". 20 December 2012.

- ^

- "Syrian Arab Republic". Federal Foreign Office. 13 January 2023. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023.

System of government: Officially a socialist,... democratic state; presidential system (ruled by the al-Assad family, with the security services occupying a powerful position)

- "Syria: Government". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021.

- "Syria Government". Archived from the original on 27 January 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- "Syrian Arab Republic". Federal Foreign Office. 13 January 2023. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023.

- ^

- Khamis, B. Gold, Vaughn, Sahar, Paul, Katherine (2013). "22. Propaganda in Egypt and Syria's "Cyberwars": Contexts, Actors, Tools, and Tactics". In Auerbach, Castronovo, Jonathan, Russ (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-976441-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wieland, Carsten (2018). "6: De-neutralizing Aid: All Roads Lead to Damascus". Syria and the Neutrality Trap: The Dilemmas of Delivering Humanitarian Aid Through Violent Regimes. London: I. B. Tauris. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7556-4138-3.

- Ahmed, Saladdin (2019). Totalitarian Space and the Destruction of Aura. Albany, New York: Suny Press. pp. 144, 149. ISBN 9781438472911.

- Hensman, Rohini (2018). "7: The Syrian Uprising". Indefensible: Democracy, Counterrevolution, and the Rhetoric of Anti-Imperialism. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-60846-912-3.

- Khamis, B. Gold, Vaughn, Sahar, Paul, Katherine (2013). "22. Propaganda in Egypt and Syria's "Cyberwars": Contexts, Actors, Tools, and Tactics". In Auerbach, Castronovo, Jonathan, Russ (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-976441-9.

- ^ "Syrian ministry of foreign affairs". Archived from the original on 2012-05-11.

- ^ "Syria Population". World of Meters.info. Retrieved 6 November 2024.

- ^ أ ب ت "Syria". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "World Bank GINI index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2023-24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme (in الإنجليزية). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. pp. 274–277. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "Syrian government appears to have fallen in stunning end to 50-year rule of Assad family". AP News (in الإنجليزية). 2024-12-07. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

- ^ أ ب "Background Note: Syria". United States Department of State, Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, May 2007. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

هذا المقال يضم نصاً من هذا المصدر، الذي هو مشاع.

هذا المقال يضم نصاً من هذا المصدر، الذي هو مشاع.

- ^ أ ب "Syria: World War II and independence". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. 23 May 2023. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- ^ Wieland, Carsten (2021). Syria and the Neutrality Trap. New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-7556-4138-3.

- ^ Atassi, Karim (2018). "6: The Fourth Republic". Syria, the Strength of an Idea: The Constitutional Architectures of Its Political Regimes. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 252. doi:10.1017/9781316872017. ISBN 978-1-107-18360-5.

- ^ "Salah Jadid, 63, Leader of Syria Deposed and Imprisoned by Assad". The New York Times. 24 August 1993. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ أ ب Seale, Patrick (1988). Asad: The Struggle for the Middle East. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06976-3.

- ^ Mark A. Tessler (1994). A History of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 382. ISBN 978-0-253-20873-6.

- ^ "A Campaign for the Books". Time. 1 September 1967. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008.

- ^ Line Khatib (23 May 2012). Islamic Revivalism in Syria: The Rise and Fall of Ba'thist Secularism. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-415-78203-6.

- ^ "Jordan asked Nixon to attack Syria, declassified papers show". CNN. 28 November 2007. Archived from the original on 25 February 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ أ ب Michael Bröning (7 March 2011). "The Sturdy House That Assad Built". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ P. Miller, H. Rand, Andrew, Dafna (2020). "2: The Syrian Crucible and Future U.S. Options". Re-Engaging the Middle East. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780815737629.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rabinovich, Abraham (2005). The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East. New York City: Schocken Books. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-8052-4176-1.

- ^ Itzchak Weismann. "Sufism and Sufi Brotherhoods in Syria and Palestine". University of Oklahoma. Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ أ ب Wright 2008: 243-244

- ^ أ ب Amos, Deborah (2 February 2012). "30 Years Later, Photos Emerge From Killings In Syria". NPR. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012.

- ^ Marc Perelman (11 July 2003). "Syria Makes Overture Over Negotiations". Forward.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ George, Alan (2003). Syria: neither bread nor freedom. London: Zed Books. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-1-84277-213-3.

- ^ Ghadry, Farid N. (Winter 2005). "Syrian Reform: What Lies Beneath". The Middle East Quarterly. Archived from the original on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Profile: Syria's Bashar al-Assad". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Huggler, Justin (6 October 2003). "Israel launches strikes on Syria in retaliation for bomb attack". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- ^ "Naharnet Newsdesk – Syria Curbs Kurdish Riots for a Merger with Iraq's Kurdistan". Naharnet.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Guerin, Orla (6 March 2005). "Syria sidesteps Lebanon demands". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Last Syrian troops out of Lebanon". Los Angeles Times. 27 April 2005. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Sanger, David (14 October 2007). "Israel Struck Syrian Nuclear Project, Analysts Say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ "Syrian army tanks 'moving towards Hama'". BBC News. 5 May 2011. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ "'Dozens killed' in Syrian border town". Al Jazeera. 17 May 2011. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "'Defected Syria security agent' speaks out". Al Jazeera. 8 June 2011. Archived from the original on 13 June 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ "Syrian army starts crackdown in northern town". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Sengupta, Kim (20 February 2012). "Syria's sectarian war goes international as foreign fighters and arms pour into country". The Independent. Antakya. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Syrian Observatory for Human Rights". Syriahr.com. Archived from the original on 2014-04-21. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ^ "Arab League delegates head to Syria over 'bloodbath'". USA Today. 22 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Number as a civil / military". Translate.googleusercontent.com. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ^ Enders, David (2012-04-19). "Syria's Farouq rebels battle to hold onto Qusayr, last outpost near Lebanese border". Myrtle Beach Sun News. Archived from the original on 2014-10-25. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ^ "Syria: Opposition, almost 11,500 civilians killed". Ansamed.ansa.it. 2010-01-03. Archived from the original on 2014-03-28. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ^ 6,143 civilians and security forces (15 March 2011-20 March 2012),[1] Archived 2012-04-23 at the Wayback Machine 865 security forces (21 March-1 June),"Syrian Arab news agency - SANA - Syria : Syria news ::". Archived from the original on 2012-10-29. Retrieved 2012-07-17. 3,138 insurgents (15 March 2011-30 May 2012),[2] Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback MachineEnders, David (2012-04-19). "Syria's Farouq rebels battle to hold onto Qusayr, last outpost near Lebanese border". Myrtle Beach Sun News. Archived from the original on 2014-10-25. Retrieved 2014-12-13. total of 10,146 reported killed

- ^ "Syria: Refugees brace for more bloodshed". News24. 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Syrian Refugees May Be Wearing Out Turks' Welcome". NPR. 11 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Syria crisis: Turkey refugee surge amid escalation fear". BBC News. 6 April 2012. Archived from the original on 8 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "UNICEF says 400 children killed in Syria unrest". Google News. Geneva. Agence France-Presse. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "UNICEF: 500 children died in Syrian war". Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- ^ "UNICEF says 400 children killed in Syria". The Courier-Mail. 8 February 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ Peralta, Eyder (3 February 2012). "Rights Group Says Syrian Security Forces Detained, Tortured Children: The Two-Way". NPR. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ "Syrian Arab news agency - SANA - Syria : Syria news". Sana.sy. 2012-02-14. Archived from the original on 2018-11-06. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem (5 January 2012). "Hundreds Tortured in Syria, Human Rights Group Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "Syria: Local Residents Used as Human Shields". Huffingtonpost.com. 2012-03-26. Archived from the original on 2012-06-27. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- ^ "Syria: Armed Opposition Groups Committing Abuses". Human Rights Watch. 20 March 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Open Letter to the Leaders of the Syrian Opposition Regarding Human Rights Abuses by Armed Opposition Members". Human Rights Watch. 20 March 2012. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Global Data". FragileStatesIndex.org. 2024.

- ^ "Syria". Reporters Without Borders. 2024. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024.

- ^ "Syria ranks second to last in RSF's press freedom index". Enab Baladi. 3 May 2024. Archived from the original on 3 May 2024.

- ^ "Middle East corruption rankings: Syria most corrupt, UAE least, Turkey slipped". Al-Monitor. 31 January 2023. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023.

- ^ "Syria, Yemen and Libya among 'lowest in the world' for corruption perceptions". The New Arab. 31 January 2023. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index". transparency.org. January 2024.

- ^ Hubbard, Ben; Saad, Hwaida (2021-12-05). "On Syria's Ruins, a Drug Empire Flourishes". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2021-12-28. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- ^ "Is the Syrian Regime the World's Biggest Drug Dealer?". Vice World News. 14 December 2022. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022.

- ^ "Syria has become a narco-state". The Economist. 2021-07-19. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2023-12-27.

- ^ Rose, Söderholm, Caroline, Alexander (April 2022). "The Captagon Threat: A Profile of Illicit Trade, Consumption, and Regional Realities" (PDF). New Lines Institute. pp. 2–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Syrian Revolution 13 years on | Nearly 618,000 persons killed since the onset of the revolution in March 2011". SOHR. 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Assad, Iran, Russia committed 91% of civilian killings in Syria". Middle East Monitor. 20 June 2022. Archived from the original on 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Civilian Death Toll". SNHR. September 2022. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022.

- ^ "91 percent of civilian deaths caused by Syrian regime and Russian forces: rights group". The New Arab. 19 June 2022. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023.

- ^ "2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Syria". U.S Department of State. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022.

- ^ "In Syria's Civilian Death Toll, The Islamic State Group, Or ISIS, Is A Far Smaller Threat Than Bashar Assad". SOHR. 11 January 2015. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Assad's War on the Syrian People Continues". SOHR. 11 March 2021. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021.

- ^ Roth, Kenneth (9 January 2017). "Barack Obama's Shaky Legacy on Human Rights". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021.

- ^ "The Regional War in Syria: Summary of Caabu event with Christopher Phillips". Council for Arab-British Understanding. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ "UNHCR Syria Regional Refugee Response". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ "Syria: Unprecedented rise in poverty rate, significant shortfall in humanitarian aid funding". Reliefweb. 18 October 2022. Archived from the original on 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Every Day Counts: Children of Syria cannot wait any longer". unicef. 2022. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022.

- ^ "Hunger, poverty and rising prices: How one family in Syria bears the burden of 11 years of conflict". reliefweb. 15 March 2022. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022.

- ^ "UN Chief says 90% of Syrians live below poverty line". 14 January 2022. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022.

- ^ "Syria crisis: Qatar calls for Arabs to send in troops". BBC News. 14 January 2012. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "NATO rules out Syria intervention". Al Jazeera. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ أ ب Iddon, Paul (2020-06-09). "Russia's expanding military footprint in the Middle East" (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 2023-01-19.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil (12 November 2011). "Arab League Votes to Suspend Syria". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ Teller, Neville (2014). The Search for Détente. p. 183.

- ^ أ ب "Syria's Stalemate Has Only Benefitted Assad and His Backers". United States Institute of Peace (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-06-15.

- ^ "Syria: US, Germany, France, UK call for de-escalation". DW News. 2 December 2024. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- ^ "Fighting Worsens Already Dire Conditions in Northwestern Syria". The New York Times. 4 December 2024.

- ^ "Syrian hospital hit in air attack on opposition-held Idlib". Al Jazeera (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ السويداء, ليث أبي نادر ــ (30 November 2024). "تحشيدات في درعا جنوبيّ سورية.. وتأييد واسع لعملية "ردع العدوان"". العربي الجديد. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "تحشيدات في درعا جنوبيّ سورية.. وتأييد واسع لعملية ردع العدوان ...الكويت". Al-Araby. 30 November 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ "Syria rebels capture major city of Hama after military withdraws". BBC News (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ "Syrian army launches counterattack as rebels push towards Hama". France24. 4 December 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "Sweida is out of the regime's control.. Local gunmen control many security centers in the city and its surroundings, and the governor flees after tensions escalate" (in Arabic). SOHR. 6 December 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "المعارضة المسلحة تصل السويداء وتسيطر على مقرات أمنية (فيديو)". Erem news. 6 December 2024.

- ^ "With the withdrawal of Russian forces to the Hmeimim base.. Regime forces and Iranian militias leave the city of Palmyra, east of Homs" (in Arabic). SOHR. 6 December 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "After the entry of the "SDF" .. the pro-Iranian militias evacuate their positions in Al-Bukamal in the eastern countryside of Deir Ezzor". SOHR. 6 December 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "After the advance of local factions to Daraa al-Balad.. Regime forces lose almost complete control over the province" (in Arabic). SOHR. 6 December 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "US-backed Syrian Free Army advances in Homs, with reports of clashes with regime forces in Palmyra". Middle East Monitor. 6 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "For the first time since Israel occupied the Syrian Golan Heights, regime forces withdraw from their positions on the border with the Golan Heights and most of the southern regions, and Russia withdraws from its points" (in Arabic). SOHR. 7 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Israel Army Says Assisting UN Forces In 'Repelling Attack' In Syria". Barron's. 7 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Ousted Syrian leader Assad flees to Moscow after fall of Damascus, Russian state media say". AP News (in الإنجليزية). 2024-12-08. Retrieved 2024-12-09.

- ^ "Ex-Syrian PM to supervise state bodies until transition". Al Jazeera (in الإنجليزية). 8 December 2024.

- ^ "Syria 101: 4 attributes of Assad's authoritarian regime". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

- ^ Karam, Zeina (12 November 2020). "In ruins, Syria marks 50 years of Assad family rule". AP News. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020.

- ^ *"Syrian Arab Republic". Federal Foreign Office. 13 January 2023. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023.

- "Syria: Government". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021.

- "Syria Government". Archived from the original on 27 January 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- ^ "Syria: Government". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- ^ "Freedom in the World 2023: Syria". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023.

- ^ Lucas, Scott (25 February 2021). "How Assad Regime Tightened Syria's One-Party Rule". EA Worldview. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Freedom in the World 2023: Syria". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023.

- ^ "Decrees on Ending State of Emergency, Abolishing SSSC, Regulating Right to Peaceful Demonstration". Syrian Arab News Agency. 22 April 2011. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ "Syria (05/07)". State.gov. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

هذا المقال يضم نصاً من هذا المصدر، الذي هو مشاع.

هذا المقال يضم نصاً من هذا المصدر، الذي هو مشاع.

- ^ "Syria". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 13. Archived from the original on 18 January 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "Syria (Syrian Arab Republic)". Law.emory.edu. Archived from the original on 21 August 2001. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ Shaar, Akil, Karam, Samy (28 January 2021). "Inside Syria's Clapping Chamber: Dynamics of the 2020 Parliamentary Elections". Middle East Institute. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Awad, Ziad; Favier, Agnès (30 April 2020). "Elections in Wartime: The Syrian People's Council (2016–2020)" (PDF). Middle East Directions Programme at Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2021 – via European University Institute.

- ^ Abdel Nour, Aymen (24 July 2020). "Syria's 2020 parliamentary elections: The worst joke yet". Middle East Institute. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021.

- ^ Αϊβαλιώτης, Γιώργος (13 April 2016). "Συρία: Βουλευτικές εκλογές για την διαπραγματευτική ενίσχυση Άσαντ". euronews.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ "Εκλογές στη Συρία, ενώ η εμπόλεμη κατάσταση παραμένει". efsyn.gr. 13 April 2016. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ Kossaify, Ephrem (22 April 2021). "UN reiterates it is not involved in Syrian presidential election". Arab News. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021.

- ^ Cheeseman, Nicholas (2019). How to Rig an Election. Yale University Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-300-24665-0. OCLC 1089560229.

- ^ Norris, Pippa; Martinez i Coma, Ferran; Grömping, Max (2015). "The Year in Elections, 2014". Election Integrity Project (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

The Syrian election ranked as worst among all the contests held during 2014.

- ^ Abdel Nour, Aymen (24 July 2020). "Syria's 2020 parliamentary elections: The worst joke yet". Middle East Institute. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021.

- ^ "Electoral Integrity Global Report 2019-2021". Electoral Integrity Project. May 2022. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022.

- ^ Garnett, S. James, MacGregor, Holly Ann, Toby, Madison . (May 2022). "2022. Year in Elections Global Report: 2019-2021. The Electoral Integrity Project" (PDF). Electoral Integrity Project. University of East Anglia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with redirect hatnotes needing review

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the flag caption or type parameters

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the symbol caption or type parameters

- جميع المقالات بحاجة لمصادر إضافية

- مقالات بحاجة لمصادر إضافية from December 2024

- صفحات بها قالب:Ill-WD2 دون وصلات لغات

- تأسيسات 1963 في سوريا

- انحلالات 2024 في سوريا

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1963

- دول وأقاليم انحلت في 2024

- القرن 20 في سوريا

- القرن 21 في سوريا

- بلدان سابقة في غرب آسيا

- جمهوريات عربية

- دول بعثية

- دول عربية سابقة

- جمهوريات اشتراكية سابقة

- تاريخ سوريا

- تاريخ حزب البعث السوري

- التاريخ السياسي لسوريا

- الاشتراكية في سوريا

- دول شمولية

- حافظ الأسد

- بشار الأسد