الجبهة الداخلية للولايات المتحدة خلال الحرب العالمية الثانية

| United States Home Front | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1942–1945 | |||

Service on the Home Front by Louis Hirshman and William Tasker. | |||

| المكان | United States | ||

| ويضم | New Deal Era Second Great Migration | ||

| الرئيس | Franklin Delano Roosevelt Harry Truman | ||

| الأحداث الرئيسية | Attack on Pearl Harbor Double V campaign Rationing Internment policies Conscription G.I. Bill | ||

| |||

The United States home front during World War II supported the war effort in many ways, including a wide range of volunteer efforts and submitting to government-managed rationing and price controls. There was a general feeling of agreement that the sacrifices were for the national good during the war.

The labor market changed radically. Peacetime conflicts concerning race and labor took on a special dimension because of the pressure for national unity. The Hollywood film industry was important for propaganda. Every aspect of life from politics to personal savings changed when put on a wartime footing. This was achieved by tens of millions of workers moving from low to high productivity jobs in industrial centers. Millions of students, retirees, housewives, and unemployed moved into the active labor force. The hours they had to work increased dramatically as the time for leisure activities declined sharply.

Gasoline, meat, clothing, and footwear were tightly rationed. Most families were allocated 3 US gallons (11 L; 2.5 imp gal) of gasoline a week, which sharply curtailed driving for any purpose. Production of most durable goods, like new housing, vacuum cleaners, and kitchen appliances, was banned until the war ended.[1] In industrial areas housing was in short supply as people doubled up and lived in cramped quarters. Prices and wages were controlled. Americans saved a high portion of their incomes, which led to renewed growth after the war.[2][3]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Controls and taxes

Federal tax policy was highly contentious during the war, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt opposing a conservative coalition in Congress. However, both sides agreed on the need for high taxes (along with heavy borrowing) to pay for the war: top marginal tax rates ranged from 81–94% for the duration of the war, and the income level subject to the highest rate was lowered from $5,000,000 to $200,000. Roosevelt tried unsuccessfully, by executive order 9250,[4] to impose a 100% surtax on after-tax incomes over $25,000 (equal to roughly $335٬769 today). However, Roosevelt did manage to impose this cap on executive pay in corporations with government contracts.[5] Congress also enlarged the tax base by lowering the minimum income to pay taxes, and by reducing personal exemptions and deductions. By 1944 nearly every employed person was paying federal income taxes (compared to 10% in 1940).[6]

Many controls were put on the economy. The most important was price controls, imposed on most products and monitored by the Office of Price Administration. Wages were also controlled.[7] Corporations dealt with numerous agencies, especially the War Production Board (WPB), and the War and Navy departments, which had the purchasing power and priorities that largely reshaped and expanded industrial production.[8]

In 1942 a rationing system was begun to guarantee minimum amounts of necessities to everyone (especially poor people) and prevent inflation. Tires were the first item to be rationed in January 1942 because supplies of natural rubber were interrupted. Gasoline rationing proved an even better way to allocate scarce rubber. In June 1942 the Combined Food Board was set up to coordinate the worldwide supply of food to the Allies, with special attention to flows from the U.S. and Canada to Britain. By 1943, government-issued ration coupons were required to purchase coffee, sugar, meat, cheese, butter, lard, margarine, canned foods, dried fruits, jam, gasoline, bicycles, fuel oil, clothing, silk or nylon stockings, shoes, and many other items. Some items, like automobiles and home appliances, were no longer made. The rationing system did not apply to used goods like clothes or cars, but they became more expensive since they were not subject to price controls.

To get a classification and a book of rationing stamps, people had to appear before a local rationing board. Each person in a household received a ration book, including babies and children. When purchasing gasoline, a driver had to present a gas card along with a ration book and cash. Ration stamps were valid only for a set period to forestall hoarding. All forms of automobile racing were banned, including the Indianapolis 500 which was canceled from 1942 to 1945. Sightseeing driving was banned.

Personal savings

Personal income was at an all-time high, and more dollars were chasing fewer goods to purchase. This was a recipe for economic disaster that was largely avoided because Americans—persuaded daily by their government to do so—were also saving money at an all-time high rate, mostly in War Bonds but also in private savings accounts and insurance policies. Consumer saving was strongly encouraged through investment in war bonds that would mature after the war. Most workers had an automatic payroll deduction; children collected savings stamps until they had enough to buy a bond. Bond rallies were held throughout the U.S. with celebrities, usually Hollywood film stars, to enhance the bond advertising effectiveness. Several stars were responsible for personal appearance tours that netted multiple millions of dollars in bond pledges—an astonishing amount in 1943. The public paid ¾ of the face value of a war bond and received the full face value back after a set number of years. This shifted their consumption from the war to postwar and allowed over 40% of GDP to go to military spending, with moderate inflation.[9] Americans were challenged to put "at least 10% of every paycheck into Bonds". Compliance was very high, with entire factories of workers earning a special "Minuteman" flag to fly over their plant if all workers belonged to the "Ten Percent Club". There were seven major War Loan drives, all of which exceeded their goals.[10]

Labor

The unemployment problems of the Great Depression largely ended with the mobilization for war. Out of a labor force of 54 million, unemployment fell by half from 7.7 million in spring 1940 (when the first accurate statistics were compiled) to 3.4 million by fall of 1941 and fell by half again to 1.5 million by fall of 1942, hitting an all-time low of 700,000 in fall 1944.[11] There was a growing labor shortage in war centers, with sound trucks going street by street begging for people to apply for war jobs.

Greater wartime production created millions of new jobs, while the draft reduced the number of young men available for civilian jobs. So great was the demand for labor that millions of retired people, housewives, and students entered the labor force, lured by patriotism and wages.[12] The shortage of grocery clerks caused retailers to convert from service at the counter to self-service. With new shorter women clerks replacing taller men, some stores lowered shelves to 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 m). Before the war, most groceries, dry cleaners, drugstores, and department stores offered home delivery service. The labor shortage and gasoline and tire rationing caused most retailers to stop delivery. They found that requiring customers to buy their products in person increased sales.[13]

Women

Women also joined the workforce to replace men who had joined the forces, though in fewer numbers. Roosevelt stated that the efforts of civilians at home to support the war through personal sacrifice was as critical to winning the war as the efforts of the soldiers themselves. "Rosie the Riveter" became the symbol of women laboring in manufacturing. Women worked in defense plants and volunteered for war-related organizations. Women even learned to fix cars and became "conductorettes" for the train. The war effort brought about significant changes in the role of women in society as a whole. When the male breadwinner returned, wives could stop working.

Alice Throckmorton McLean founded the American Women's Voluntary Services (AWVS) in January 1940, 23 months before the United States entered the war. When Pearl Harbor was bombed, the AWVS had more than 18,000 members who were ready to drive ambulances, fight fires, lead evacuations, operate mobile kitchens, deliver first aid, and perform other emergency services.[14] By war's end the AWVS counted 325,000 women at work and selling an estimated $1 billion in war bonds and stamps.[15]

At the end of the war, most of the munitions-making jobs ended. Many factories were closed; others retooled for civilian production. In some jobs, women were replaced by returning veterans who did not lose seniority because they were in service. However, the number of women at work in 1946 was 87% of the number in 1944, leaving 13% who lost or quit their jobs. Many women working in machinery factories and more were taken out of the workforce. Many of these former factory workers found other work at kitchens, being teachers, etc.

The table shows the development of the United States labor force by sex during the war years.[16]

| Year | Total labor force (*1000) | of which Male (*1000) | of which Female (*1000) | Female share of total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 56,100 | 41,940 | 14,160 | 25.2 |

| 1941 | 57,720 | 43,070 | 14,650 | 25.4 |

| 1942 | 60,330 | 44,200 | 16,120 | 26.7 |

| 1943 | 64,780 | 45,950 | 18,830 | 29.1 |

| 1944 | 66,320 | 46,930 | 19,390 | 29.2 |

| 1945 | 66,210 | 46,910 | 19,304 | 29.2 |

| 1946 | 60,520 | 43,690 | 16,840 | 27.8 |

SS George Washington Carver at the Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, California, April 1943.

Women also took on new roles in sport and entertainment, which opened to them as more and more men were drafted. The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League was the creation of Chicago Cubs owner Philip Wrigley, who sought alternative ways to expand his baseball franchise as top male players left for military service. In 1943, he created an eight-team league in small industrial cities around the Great Lakes. Night games offered affordable, patriotic entertainment to working Americans who had flocked to wartime jobs in the Midwest hubs of Chicago and Detroit. The league provided a novel entertainment of women playing baseball well while wearing short, feminine uniform skirts. Players as young as fifteen were recruited from white farm families and urban industrial teams. Fans supported the League to the extent that it continued well past the conclusion of the war, lasting through 1953.[17]

Farming

Labor shortages were felt in agriculture, even though most farmers were given an exemption and few were drafted. Large numbers volunteered or moved to cities for factory jobs. At the same time, many agricultural commodities were in greater demand by the military and for the civilian populations of Allies. Production was encouraged and prices and markets were under tight federal control.[18] Between December 1941 and December 1942 it was estimated 1.6 million men & women left agricultural work for military service or to get higher paying jobs in war industries.[19] Civilians were encouraged to create "victory gardens", farms that were often started in backyards and lots. Children were encouraged to help with these farms, too.[20]

The Bracero Program, a bi-national labor agreement between Mexico and the U.S., started in 1942. Some 290,000 braceros ("strong arms," in Spanish) were recruited and contracted to work in the agriculture fields. Half went to Texas, and 20% to the Pacific Northwest.[21][22]

Between 1942 and 1946 some 425,000 Italian and German prisoners of war were used as farm laborers, loggers, and cannery workers. In Michigan, for example, the POWs accounted for more than one-third of the state's agricultural production and food processing in 1944.[23]

Children

To help with the need for a larger source of food, the nation looked to school-aged children to help on farms. Schools often had a victory garden in vacant parking lots and on roofs. Children would help on these farms to help with the war effort.[24] The slogan, "Grow your own, can your own", also influenced children to help at home.[25]

Teenagers

With the war's ever-increasing need for able-bodied men consuming America's labor force in the early 1940s, industry turned to teen-aged boys and girls to fill in as replacements.[26][27] Consequently, many states had to change their child-labor laws to allow these teenagers to work. The lures of patriotism, adulthood, and money led many youths to drop out of school and take a defense job. Between 1940 and 1944, the number of teenage workers tripled from 870,000 in 1940 to 2.8 million in 1944, while the number of students in public high schools dropped from 6.6 million in 1940 to 5.6 million in 1944, about a million students—and many teachers—took jobs.[28] Policymakers did not want high school students to drop out. Government agencies, parents, school administrations and employers would cooperate in local "Go-to-School Drives" to encourage high school students to stay whether this be part or full-time.[29]

The Victory Farm Volunteers under the US Crop Corps accepted teenagers from 14–18 to work in agricultural jobs. However some states did lower their age limit with the youngest being 9. At the program's peak in 1944 there would be 903,794 volunteers which made it larger than the amount in the Women's Land Army, foreign migrant workers and the amount of prisoners of war who were laborers. These volunteers were mainly from the cities and urban areas. Volunteers mostly worked for three months in the summer and for a fourth if high schools decided to push starting dates back. To join, a volunteer needed the consent of their parent(s)/guardian(s). There were three types of work environments for the volunteers. The most common (80% of volunteers) involved them being transported to a worksite daily via buses or farming trucks and returned home at night. Another program involved where volunteers lived with farming families and worked alongside them with about 1 in 5 doing this. There was also camps set up which were not very common as only 4% of all VFV volunteers lived there between 1943 & 1945.[19]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Labor unions

The war mobilization changed the relationship of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) with both employers and the national government.[30] Both the CIO and the larger American Federation of Labor (AFL) grew rapidly in the war years.[31]

Nearly all the unions that belonged to the CIO were fully supportive of both the war effort and of the Roosevelt administration. However, the United Mine Workers, who had taken an isolationist stand in the years leading up to the war and had opposed Roosevelt's reelection in 1940, left the CIO in 1942. The major unions supported a wartime no-strike pledge that aimed to eliminate not only major strikes for new contracts but also the innumerable small strikes called by shop stewards and local union leadership to protest particular grievances. In return for labor's no-strike pledge, the government offered arbitration to determine the wages and other terms of new contracts. Those procedures produced modest wage increases during the first few years of the war but not enough to keep up with inflation, particularly when combined with the slowness of the arbitration machinery.[32]

Even though the complaints from union members about the no-strike pledge became louder and more bitter, the CIO did not abandon it. The Mine Workers, by contrast, who did not belong to either the AFL or the CIO for much of the war, threatened numerous strikes including a successful twelve-day strike in 1943. The strikes and threats made mine leader John L. Lewis a much-hated man and led to legislation hostile to unions.[33]

All the major unions grew stronger during the war. The government put pressure on employers to recognize unions to avoid the sort of turbulent struggles over union recognition of the 1930s, while unions were generally able to obtain maintenance of membership clauses, a form of union security, through arbitration and negotiation. Employers gave workers new untaxed benefits (such as vacation time, pensions, and health insurance), which increased real incomes even when wage rates were frozen.[34] The wage differential between higher-skilled and less-skilled workers narrowed, and with the enormous increase in overtime for blue-collar wage workers (at time and a half pay), incomes in working-class households shot up, while the salaried middle class lost ground.

The experience of bargaining on a national basis, while restraining local unions from striking, also tended to accelerate the trend toward bureaucracy within the larger CIO unions. Some, such as the Steelworkers, had always been centralized organizations in which authority for major decisions resided at the top. The UAW, by contrast, had always been a more grassroots organization, but it also started to try to rein in its maverick local leadership during these years.[35] The CIO also had to confront deep racial divides in its membership, particularly in the UAW plants in Detroit where white workers sometimes struck to protest the promotion of black workers to production jobs, but also in shipyards in Alabama, mass transit in Philadelphia, and steel plants in Baltimore. The CIO leadership, particularly those in further left unions such as the Packinghouse Workers, the UAW, the NMU, and the Transport Workers, undertook serious efforts to suppress hate strikes, to educate their membership, and to support the Roosevelt Administration's tentative efforts to remedy racial discrimination in war industries through the Fair Employment Practices Commission. Those unions contrasted their relatively bold attack on the problem with the AFL.[36]

The CIO unions were progressive in dealing with gender discrimination in the wartime industry, which now employed many more women workers in nontraditional jobs. Unions that had represented large numbers of women workers before the war, such as the UE (electrical workers) and the Food and Tobacco Workers, had fairly good records of fighting discrimination against women. Most union leaders saw women as temporary wartime replacements for the men in the armed forces. The wages of these women needed to be kept high so that the veterans would get high wages.[37]

The South in wartime

The war marked a time of dramatic change in the poor, heavily rural South as new industries and military bases were developed by the Federal government, providing badly needed capital and infrastructure in many regions. People from all parts of the US came to the South for military training and work in the region's many bases and new industries. During and after the war millions of hard-scrabble farmers, both white and black, left agriculture for urban jobs.[38][39][40]

The United States began mobilizing for war in a major way in the spring of 1940. The warm sunny weather of the South proved ideal for building 60 percent of the Army's new training camps and nearly half the new airfields, In all 40 percent of spending on new military installations went to the South. For example, sleepy Starke, Florida, a town of 1,500 people in 1940, became the base of Camp Blanding. By March 1941, 20,000 men were constructing a permanent camp for 60,000 soldiers. Money flowed freely for the war effort, as over $4 billion went into military facilities in the South, and another $5 billion into defense plants. Major shipyards were built in Virginia, Charleston, and along the Gulf Coast. Huge warplane plants were opened in Dallas-Fort Worth and Georgia. The most secret and expensive operation was at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where unlimited amounts of locally generated electricity were used to prepare uranium for the atom bomb.[41] The number of production workers doubled during the war. Most training centers, factories and shipyards were closed in 1945 and the families that left hardscrabble farms often remained to find jobs in the urban South. The region had finally reached the take off stage into industrial and commercial growth, although its income and wage levels lagged well behind the national average. Nevertheless, as George B. Tindall notes, the transformation was, "The demonstration of industrial potential, new habits of mind, and a recognition that industrialization demanded community services."[42][43]

Civilian support for war effort

Early in the war, it became apparent that German U-boats were using the backlighting of coastal cities in the Eastern Seaboard and the South to destroy ships exiting harbors. It became the first duty of civilians recruited for the local civilian defense to ensure that lights were either off or thick curtains drawn over all windows at night.

State Guards were reformed for internal security duties to replace the National Guardsmen who were federalized and sent overseas. The Civil Air Patrol was established, which enrolled civilian spotters in air reconnaissance, search-and-rescue, and transport. Its Coast Guard counterpart, the Coast Guard Auxiliary, used civilian boats and crews in similar rescue roles. Towers were built in coastal and border towns, and spotters were trained to recognize enemy aircraft. Blackouts were practiced in every city, even those far from the coast. All exterior lighting had to be extinguished, and black-out curtains placed over windows. The main purpose was to remind people that there was a war on and to provide activities that would engage the civil spirit of millions of people not otherwise involved in the war effort. In large part, this effort was successful, sometimes almost to a fault, such as the Plains states where many dedicated aircraft spotters took up their posts night after night watching the skies in an area of the country that no enemy aircraft of that time could hope to reach.[44]

The United Service Organizations (USO) was founded in 1941 in response to a request from President Franklin D. Roosevelt to provide morale and recreation services to uniformed military personnel. The USO brought together six civilian agencies: the Salvation Army, YMCA, Young Women's Christian Association, National Catholic Community Service, National Travelers Aid Association, and the National Jewish Welfare Board.[45]

Women volunteered to work for the Red Cross, the USO, and other agencies. Other women previously employed only in the home, or in traditionally female work, took jobs in factories that directly supported the war effort or filled jobs vacated by men who had entered military service. Enrollment in high schools and colleges plunged as many high school and college students dropped out to take war jobs.[46][47][48]

Various items, previously discarded, were saved after use for what was called "recycling" years later. Families were requested to save fat drippings from cooking for use in soap making. Neighborhood "scrap drives" collected scrap copper and brass for use in artillery shells. Milkweed was harvested by children ostensibly for lifejackets.[49]

Draft

In 1940, Congress passed the first peace-time draft legislation. It was renewed (by one vote) in summer 1941. It involved questions as to who should control the draft, the size of the army, and the need for deferments. The system worked through local draft boards comprising community leaders who were given quotas and then decided how to fill them. There was very little draft resistance.[50]

The nation went from a surplus manpower pool with high unemployment and relief in 1940 to a severe manpower shortage by 1943. The industry realized that the Army urgently desired production of essential war materials and foodstuffs more than soldiers. (Large numbers of soldiers were not used until the invasion of Europe in summer 1944.) In 1940–43 the Army often transferred soldiers to civilian status in the Enlisted Reserve Corps to increase production. Those transferred would return to work in essential industry, although they could be recalled to active duty if the Army needed them. Others were discharged if their civilian work was deemed essential. There were instances of mass releases of men to increase production in various industries. Working men who had been classified 4F or otherwise ineligible for the draft took second jobs.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In the figure below an overview of the development of the United States labor force, the armed forces and unemployment during the war years.[51]

| Year | Total labor force (*1000) | Armed forces (*1000) | Unemployed (*1000) | Unemployment rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | 55,588 | 370 | 9,480 | 17.2 |

| 1940 | 56,180 | 540 | 8,120 | 14.6 |

| 1941 | 57,530 | 1,620 | 5,560 | 9.9 |

| 1942 | 60,380 | 3,970 | 2,660 | 4.7 |

| 1943 | 64,560 | 9,020 | 1,070 | 1.9 |

| 1944 | 66,040 | 11,410 | 670 | 1.2 |

| 1945 | 65,290 | 11,430 | 1,040 | 1.9 |

| 1946 | 60,970 | 3,450 | 2,270 | 3.9 |

One contentious issue involved the drafting of fathers, which was avoided as much as possible. The drafting of 18-year-olds was desired by the military but vetoed by public opinion. Racial minorities were drafted at the same rate as Whites and were paid the same. The experience of World War I regarding men needed by industry was particularly unsatisfactory—too many skilled mechanics and engineers became privates (there is a possibly apocryphal story of a banker assigned as a baker due to a clerical error, noted by historian Lee Kennett in his book "G.I.") Farmers demanded and were generally given occupational deferments (many volunteered anyway, but those who stayed at home lost postwar veteran's benefits.)

Later in the war, in light of the tremendous amount of manpower that would be necessary for the invasion of France in 1944, many earlier deferment categories became draft eligible.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Religion

In the 1930s, pacifism was a very strong force in most of the Protestant churches. Only a minority of religious leaders, typified by Reinhold Niebuhr, paid serious attention to the threats to peace posed by Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, or militaristic Japan. After Pearl Harbor in December 1941, practically all the religious denominations gave some support to the war effort, such as providing chaplains. Typically, church members sent their sons into the military without protest, accepted shortages and rationing as a war necessity, purchased war bonds, working munitions industries, and prayed intensely for safe return and for victory. Church leaders, however, were much more cautious while holding fast to the ideals of peace, justice and humanitarianism, and sometimes criticizing military policies such as the bombing of enemy cities. They sponsored 10,000 military chaplains, and set up special ministries in and around military bases, focused not only on soldiers but their young wives who often followed them. The mainstream Protestant churches supported the "Double V" campaign of the black churches to achieve victory against the enemies abroad, and victory against racism on the home front. However, there was little religious protest against the incarceration of Japanese on the West Coast or against segregation of Blacks in the services. The intense moral outrage regarding the Holocaust largely appeared after the war ended, especially after 1960. Many church leaders supported studies of postwar peace proposals, typified by John Foster Dulles, a leading Protestant layman and a leading adviser to top-level Republicans. The churches promoted strong support for European relief programs, especially through the United Nations.[52][53]

Pacifism

The major churches showed much less pacifism than in 1914. The pacifist churches such as the Quakers and Mennonites were small but maintained their opposition to military service, though many young members, such as Richard Nixon voluntarily joined the military. Unlike in 1917–1918, the positions were generally respected by the government, which set up non-combat civilian roles for conscientious objectors. The Church of God had a strong pacifist element reaching a high point in the late 1930s. This small Fundamentalist Protestant denomination regarded World War II as a just war because America was attacked.[54] Likewise, the Quakers generally regarded World War II as a just war and about 90% served, although there were some conscientious objectors.[55] The Mennonites and Brethren continued their pacifism, but the federal government was much less hostile than in the previous war. These churches helped their young men to both become conscientious objectors and to provide valuable service to the nation. Goshen College set up a training program for unpaid Civilian Public Service jobs. Although young women pacifists were not eligible for the draft, they volunteered for unpaid Civilian Public Service jobs to demonstrate their patriotism; many worked in mental hospitals.[56] The Jehovah's Witness denomination, however, refused to participate in any forms of service, and thousands of its young men refused to register and went to prison.[57]

As part of the 1940 Selective Service and Training Act, the Civilian Public Service would be formed for conscientious objectors to do work considered to be of "national importance". What type of work varied based on the location of the camps and what was needed.[58] Overall, about 43,000 conscientious objectors (COs) refused to take up arms. About 6,000 COs went to prison, especially the Jehovah's Witnesses. About 12,000 served in Civilian Public Service (CPS)—but never received any veterans benefits. About 25,000 or more performed noncombatant jobs in the military, and did receive postwar veterans benefits.[59][60]

A rare but notable example of pacifism from within the government came from Jeannette Rankin's opposition to the war. Rankin voted against the war particularly because she saw women and peace to be 'inseparable',[61] and even actively encouraged women to do more to prevent the war in America.[62]

Suspected disloyalty

Civilian support for the war was widespread, with isolated cases of draft resistance. The F.B.I. was already tracking elements that were suspected of loyalty to Germany, Japan, or Italy, and many were arrested in the weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. 7,000 German and Italian aliens (who were not U.S. citizens) were moved back from the West Coast, along with some 100,000 of Japanese descent. Some enemy aliens were held without trial during the entire war. The U.S. citizens accused of supporting Germany were given public trials, and often were freed.[63][64][65]

Population movements

There was large-scale migration to industrial centers, especially the West Coast. Millions of wives followed their husbands to military camps; for many families, especially from farms, the moves were permanent. One 1944 survey of migrants in Portland, Oregon and San Diego found that three quarters wanted to stay after the war.[66] Many new military training bases were established or enlarged, especially in the South. Large numbers of African Americans left the cotton fields and headed for the cities. Housing was increasingly difficult to find in industrial centers, as there was no new non-military construction.

Transportation

During the war, the Office of Defense Transportation (ODT) would be created to help regulate transportation. During the war people would reduce travelling for personal reasons. Those that drove cars would do less and carpool. People would end up walking and bicycling more often while bus and rail usages would increase to levels that were never seen until that point.[67]

When the United States entered World War II, it was a vastly motorized country as about 85% of all passenger travel came from private cars while all other forms of mass transit made up about 14% of passenger travel. Commuting by car would be limited by the ODT through car, tire and gasoline rationing, banning pleasure driving, regulating the movement of commercial vehicles, establishing a national 35 miles per hour (56 km/h) speed limit along with public campaigns and carpooling programs. What was defined as pleasure driving was ambiguous and the policy banning it was unpopular. The newly established speed limit was enforced by state and local level officials. Exemptions were made to the national speed limit for military and emergencies vehicles that were on duties that required speedier travel times.[67] During the war, taxis were also regulated by the ODT.[68]

Railroads previously saw a decline in travel during the 1920s and 30s with World War 2 reversing this decline as the amount of passenger travel dramatically increased. This gain in railroad travel largely came from soldiers who were travelling. During the war 43 million soldiers were transported at an average of 1 million per month.[68]

In 1941 prior to the United States entering the war, 3.4 million passengers were transported both across the Atlantic Ocean and throughout the United States. Many airlines ended up cancelling their regular flights and turned over the 200 out of 360 airlines to the military,[68] which would be placed under the Air Transport Command.[69] During the war "casual" air travel would practically disappear in the United States.[70]

Racial tensions

The large-scale movement of black Americans from the rural South to urban and defense centers in the North and the West (and some in the South) during the Second Great Migration led to local confrontations over jobs and housing shortages. The cities were relatively peaceful; much-feared large-scale race riots did not happen, but there was nevertheless violence on both sides, as in the 1943 race riot in Detroit and the anti-Mexican Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles in 1943.[71] The "zoot suit" was a highly conspicuous costume worn by Mexican American teenagers in Los Angeles. As historian Roger Bruns notes, "the Zoot suit also represented a stark visual expression of culture for Mexican Americans, about making a statement—a mark of defiance against the place in society in which they found themselves." They gained admiration from within their in-group, and "disgust and ridicule from others, especially the Anglos."[72]

Role of women

Standlee (2010) argues that during the war the traditional gender division of labor changed somewhat, as the "home" or domestic female sphere expanded to include the "home front". Meanwhile, the public sphere—the male domain—was redefined as the international stage of military action.[73]

Employment

Wartime mobilization drastically changed the sexual divisions of labor for women, as young able-bodied men were sent overseas and wartime manufacturing production increased. Throughout the war, according to Susan Hartmann (1982), an estimated 6.5 million women entered the labor force. Women, many of whom were married, took a variety of paid jobs in a multitude of vocational jobs, many of which were previously exclusive to men. The greatest wartime gain in female employment was in the manufacturing industry, where more than 2.5 million additional women represented an increase of 140 percent by 1944.[74] This was catalyzed by the "Rosie the Riveter" phenomenon.

The composition of the marital status of women who went to work changed considerably throughout the war. One in every ten married women entered the labor force during the war, and they represented more than three million of the new female workers, while 2.89 million were single and the rest widowed or divorced. For the first time in the nation's history, there were more married women than single women in the female labor force. In 1944, thirty-seven percent of all adult women were reported in the labor force, but nearly fifty percent of all women were employed at some time during that year at the height of wartime production.[74] In the same year the unemployment rate hit an all-time historical low of 1.2%.[75]

According to Hartmann (1982), the women who sought employment, based on various surveys and public opinion reports at the time suggests that financial reasoning was the justification for entering the labor force; however, patriotic motives made up another large portion of women's desires to enter. Women whose husbands were at war were more than twice as likely to seek jobs.[74]

Fundamentally, women were thought to be taking work defined as "men's work;" however, the work women did was typically catered to specific skill sets management thought women could handle. Management would also advertise women's work as an extension of domesticity.[76] For example, in a Sperry Corporation recruitment pamphlet the company stated, "Note the similarity between squeezing orange juice and the operation of a small drill press." A Ford Motor Company at Willow Run bomber plant publication proclaimed, "The ladies have shown they can operate drill presses as well as egg beaters." One manager was even stated saying, "Why should men, who from childhood on never so much as sewed on buttons be expected to handle delicate instruments better than women who have plied embroidery needles, knitting needles, and darning needles all their lives?"[76] In these instances, women were thought of and hired to do jobs management thought they could perform based on sex-typing.

Following the war, many women left their jobs voluntarily. One Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant (formally Twin Cities Ordnance Plant) worker in New Brighton, Minnesota confessed, "I will gladly get back into the apron. I did not go into war work with the idea of working all my life. It was just to help out during the war."[77] Other women were laid off by employers to make way for returning veterans who did not lose their seniority due to the war.

There are a few examples of reluctance of women to take on wartime jobs. For example, due to labour shortages the American government had to actively promote the war to civilians and the War Manpower Commission used propaganda to sell the war to American women. There was a change in attitudes regarding women in employment in wartime America, and the government started to promote women in work as part of nature, and those that resisted or were reluctant to find work were slackers.[78]

By the end of the war, many men who entered into the service did not return. This left women to take up the sole responsibility of the household and provide economically for the family.

Nursing

Nursing became a highly prestigious occupation for young women. A majority of female civilian nurses volunteered for the Army Nurse Corps or the Navy Nurse Corps. These women automatically became officers.[79] Teenaged girls enlisted in the Cadet Nurse Corps. To cope with the growing shortage on the homefront, thousands of retired nurses volunteered to help out in local hospitals.[80][81]

Volunteer activities

Women staffed millions of jobs in community service roles, such as nursing, the USO,[45] and the Red Cross.[82] Unorganized women were encouraged to collect and turn in materials that were needed by the war effort. Women collected fats rendered during cooking, children formed balls of aluminum foil they peeled from chewing gum wrappers and also created rubber band balls, which they contributed to the war effort. Hundreds of thousands of men joined civil defense units to prepare for disasters, such as enemy bombing.

The Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) mobilized 1,000 civilian women to fly new warplanes from the factories to airfields located on the east coast of the U.S. This was historically significant because flying a warplane had always been a male role. No American women flew warplanes in combat.[83]

Baby boom

Marriage and motherhood came back as prosperity empowered couples who had postponed marriage. The birth rate started shooting up in 1941, paused in 1944–45 as 12 million men were in uniform, then continued to soar until reaching a peak in the late 1950s. This was the "Baby Boom".

In a New Deal-like move, the federal government set up the "EMIC" program that provided free prenatal and natal care for the wives of servicemen below the rank of sergeant.

Housing shortages, especially in the munitions centers, forced millions of couples to live with parents or in makeshift facilities. Little housing had been built in the Depression years, so the shortages grew steadily worse until about 1949 when a massive housing boom finally caught up with demand. (After 1944 much of the new housing was supported by the G.I. Bill.)

Federal law made it difficult to divorce absent servicemen, so the number of divorces peaked when they returned in 1946. In long-range terms, divorce rates changed little.[44]

Housewives

Juggling their roles as mothers due to the Baby Boom and the jobs they filled while the men were at war, women strained to complete all tasks set before them. The war caused cutbacks in automobile and bus service and migration from farms and towns to munitions centers. Those housewives who worked found the dual role difficult to handle.

Stress came when sons, husbands, fathers, brothers, and fiancés were drafted and sent to faraway training camps, preparing for a war in which nobody knew how many would be killed. Millions of wives tried to relocate near their husbands' training camps.[44]

Racial politics of the war

Immigration policies during and after World War II

During World War II the trend in immigration policies was both more and less restrictive. The United States immigration policies focused more on national security and were driven by foreign policy imperatives.[84] Legislation such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was finally repealed. This Act was the first law in the United States that excluded a specific group—the Chinese—from migrating to the United States.[84] But during World War II, with the Chinese as allies, the United States passed the Magnuson Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943. There was also the Nationality Act of 1940, which clarified how to become and remain a citizen.[84] Specifically, it allowed immigrants who were not citizens, like the Filipinos or those in the outside territories to gain citizenship by enlisting in the army. In contrast, the Japanese and Japanese-Americans were subject to internment in the U.S. There was also legislation like the Smith Act, also known as the Alien Registration Act of 1940, which required indicted communists, anarchists, and fascists. Another program was the Bracero Program, which allowed over two decades, nearly 5 million Mexican workers to come and work in the United States.[84]

When World War II broke out in 1939, a common belief spread that Germany was planting spies and saboteurs in the US under the guise of immigrants. American consuls under the encouragement of US Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long who was the head of visa related affairs in the US State Department to screen visa applicants so much to the point that few could ever pass "the endless criteria to prove they were not 'likely to become a public charge.'" Long was described as being anti-Semitic [85] and is credited with making it harder for Jewish refugees to come to the United States.[86][87]

After World War II, there was also the Truman Directive of 1945, which did not allow more people to migrate but did use the immigration quotas to let in more displaced people after the war.[88] There was also the War Brides Act of 1945, which allowed spouses of US soldiers to get an expedited path towards citizenship. In contrast, the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act, also known as the McCarran-Walter Act, turned away migrants based not on their country of origin but rather whether they are moral or diseased.[89]

Repatriation of Americans abroad

When World War II began in Europe during 1939, the United States would attempt to repatriate approximately 100,000 Americans who were in Europe. The Special Division was created within the US State Department to handle matters involving the war and giving assistance to Americans who were abroad and being repatriated with Breckinridge Long being given responsibility of the Special Division. The US government would end up chartering 6 ships from United States Lines to repatriate Americans. On November 4, 1939 the Neutrality Act was signed into law which banned American ships from traveling to "'states engaged in armed conflict.'" and by early November 75,000 Americans had been repatriated from Europe.[90]

Internment

In 1942 the War Department demanded that all enemy nationals be removed from war zones on the West Coast. The question became how to evacuate the estimated 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry living on the Pacific Coast of the continental United States. Roosevelt looked at the secret evidence available to him:[91] the Japanese in the Philippines had collaborated with the Japanese invasion troops; most of the adult Japanese in California had been strong supporters of Japan in the war against China. There was evidence of espionage compiled by code-breakers that decrypted messages to Japan from agents in North America and Hawaii before and after the attack on Pearl Harbor. These MAGIC cables were kept a secret from all but those with the highest clearance, such as Roosevelt. On February 19, 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which set up designated military areas "from which any or all persons may be excluded." The most controversial part of the order included American born children and youth who had dual U.S. and Japanese citizenship.

In February 1943, when activating the 442nd Regimental Combat Team—a unit composed mostly of American-born American citizens of Japanese descent living in Hawaii—Roosevelt said, "No loyal citizen of the United States should be denied the democratic right to exercise the responsibilities of his citizenship, regardless of his ancestry. The principle on which this country was founded and by which it has always been governed is that Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart; Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry." In 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the legality of the executive order in the Korematsu v. United States case. The executive order remained in force until December when Roosevelt released the Japanese internees, except for those who announced their intention to return to Japan.

Fascist Italy was an official enemy, and citizens of Italy were also forced away from "strategic" coastal areas in California. Altogether, 58,000 Italians were forced to relocate. They relocated on their own and were not put in camps. Known spokesmen for Benito Mussolini were arrested and held in prison. The restrictions were dropped in October 1942, and Italy became a co-belligerent of the Allies in 1943. In the east, however, the large Italian populations of the northeast, especially in munitions-producing centers such as Bridgeport and New Haven, faced no restrictions and contributed just as much to the war effort as other Americans.

FEPC

The Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) was a federal executive order requiring companies with government contracts not to discriminate based on race or religion. It assisted African Americans in obtaining defense industry jobs during the second wave of the Great Migration of southern blacks to Northern and Western war production and urban centers. Under pressure from A. Philip Randolph's growing March on Washington Movement, on June 25, 1941, President Roosevelt created the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) by signing Executive Order 8802. It said, "there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin". In 1943 Roosevelt greatly strengthened FEPC with a new executive order, #9346. It required that all government contracts have a non-discrimination clause.[92] FEPC was the most significant breakthrough ever for Blacks and women on the job front. During the war, the federal government operated airfields, shipyards, supply centers, ammunition plants, and other facilities that employed millions. FEPC rules applied and guaranteed equality of employment rights. These facilities shut down when the war ended. In the private sector, the FEPC was generally successful in enforcing non-discrimination in the North and West but did not attempt to challenge segregation in the South, and in the border region, its intervention led to hate strikes by angry white workers.[93]

African Americans and the Double V campaign

The African American community in the United States resolved on a Double V campaign: victory over fascism abroad, and victory over discrimination at home. During the second phase of the Great Migration, five million African-Americans relocated from rural and poor Southern farms to urban and munitions centers in Northern and Western states in search of racial, economic, social, and political opportunities. Racial tensions remained high in these cities, particularly in overcrowding in housing as well as competition for jobs. As a result, cities such as Detroit, New York, and Los Angeles experienced race riots in 1943, leading to dozens of deaths.[94] Black newspapers created the Double V campaign to build black morale and head off radical action.[95]

Most black women had been farm laborers or domestics before the war.[96] Working with the federal Fair Employment Practices Committee, the NAACP, and CIO unions, these Black women fought a "Double V campaign"—fighting against the Axis abroad and restrictive hiring practices at home. Their efforts redefined citizenship, equating their patriotism with war work, and seeking equal employment opportunities, government entitlements, and better working conditions as conditions appropriate for full citizens.[97] In the South, black women worked in segregated jobs; in the West and most of the North, they were integrated. However, wildcat strikes erupted in Detroit, Baltimore, and Evansville, Indiana where white migrants from the South refused to work alongside black women.[98][99]

Racism in propaganda

Pro-American media during the war tended to portray the Axis powers in a negative light.

Germans were portrayed as weak, barbaric, or stupid, and were heavily associated with Nazism and Nazi imagery. For example, the comic book Captain America No. 1 features the titular superhero punching Hitler. Similar anti-German sentiments existed in cartoons as well. The Popeye cartoon, Seein' Red, White, 'N' Blue (aired on February 19, 1943), ends with Uncle Sam punching a sickly-looking Hitler. In the Donald Duck cartoon Der Fuehrer's Face, Donald Duck is portrayed as a Nazi living in Germany, where the Nazi war effort is heavily satirized and caricatured.[100]

American media portrayed the Japanese negatively as well. While attacks on Germans were generally focused on high-level Nazi officials such as Hitler, Himmler, Goebbels, and Göring, the Japanese were targeted more broadly. Portrayals of the Japanese ranged from showing them being vicious and feral, as on the cover of Marvel Comics' Mystery Comics no. 32, to mocking their physical appearance and speech patterns. In the Looney Tunes cartoon Tokio Jokio (aired May 13, 1943), the Japanese people are all shown to be dim-witted, obsessed with being polite, cowardly, and physically short with buckteeth, big lips, squinty eyes, and glasses. The entire cartoon is also narrated in broken English, with the letter "R" often replacing "L" in pronunciation of words, a common stereotype.[101] Japanese slurs were commonly used, such as "Jap", "monkey face", and "slanty eyes".[102][103] These stereotypes are also seen in Theodor Geisel's comics created during the Second World War.[104]

Wartime politics

Prewar background

When World War 2 began, the United States was initially neutral until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Polling done immediately after the war found over 90% opposed entering the war.[105] However, as time went on public opinion began to shift toward joining the war.[106] The most notable non-interventionist group was the America First Committee[105] which was formed in September 1940. Another smaller non-interventionist group was Keep America Out of War Congress (originally known as the Keep America Out of War Committee) or KAOWC which was a socialist-pacifist organization formed in March 1938 lasting until the Attack on Pearl Harbor.[107] With regards for pro-interventionist forces, one organization was the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies (CDAAA) which was formed in May 1940.[105] After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States joined the war and this practically ended any debate about entering the war.[106]

Roosevelt easily won the bitterly contested 1940 election, but the Conservative coalition maintained a tight grip on Congress regarding taxes and domestic issues. Wendell Willkie, the defeated GOP candidate in 1940, became a roving ambassador for Roosevelt. After Vice President Henry A. Wallace became enmeshed in a series of squabbles with other high officials, Roosevelt stripped him of his administrative responsibilities and dropped him from the 1944 ticket. Roosevelt in cooperation with big-city party leaders replaced Wallace with Missouri Senator Harry S. Truman. Truman was best known for investigating waste, fraud, and inefficiency in wartime programs.[108]

Wartime events

Despite conspiracy theories saying FDR would cancel the 1942 elections, they went ahead as they previously had prior to the war.[109] Among the 80 million men and women eligible to vote, only 28 million did so. The election would not go well for FDR and his party as they lost 7 seats in the Senate and 47 in the House of Representatives; with a Conservative coalition of Republicans and Southern Democrats taking control of both houses on domestic issues. Reducing the draft age to 18, regulations & restrictions from the war along with rationing and a drift away from the New Deal are credited with hurting the Democrats that year.[108]

In the 1944 presidential election, Roosevelt would end up defeating Thomas Dewey who came from the conservative wing of the Republican Party in a close election. Several Republicans would run for the presidential nomination which were: Wendell Willkie, New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey and Ohio Governor John W. Bricker. Dewey would win the nomination selecting Bricker as his running mate. Willkie would mobilize liberal Republicans while Dewey and Bricker attracted Republicans from the conservative bloc of the party. Campaigning would carry out during the 1944 presidential election just like in previous ones.[108][110]

Voting

During World War II, traditional means of voting were unavailable to soldiers drafted into the military along with women serving in auxiliary corps or volunteer organizations like the Red Cross; so instead those working/serving away from home had to cast absentee ballots if they chose to vote. Many states during the war did not have absentee voting laws and those that did, did not take into account the circumstance generated by the war. To solve this issue with absentee voting, US Congress would pass the 1942 and later 1944 Soldier Voting Acts.[111]

The Soldier Voting Act of 1942 would be enacted on September 16, 1942 allowing for men and women serving the country to cast an absentee ballot if they still lived in the United States. It would disregard any state voting registration requirement and prohibited the use of poll taxes for those covered by the act. However, turnout was low in the 1942 elections and of the 4 million men serving in the military along with "tens of thousands of women" 28,000 absentee ballots were cast making this a less than 1% turnout rate for those in the armed forces. Also because of the timing of the act, states did not have much time to prepare ballots. The Soldier Voting Act of 1944 would pass in April 1944. As part of the act a federal ballot was created that allowed for states that did not have adequate voting mechanisms and the act encouraged states to amend absentee voting laws. The 1944 elections did see a significantly increase in the amount of absentee ballots cast by soldiers with an estimated 3.4 million absentee votes being cast or about 25% of those in the armed forces casting an absentee ballot.[111]

Propaganda and culture

Patriotism became the central theme of advertising throughout the war, as large scale campaigns were launched to sell war bonds, promote efficiency in factories, reduce ugly rumors, and maintain civilian morale. The war consolidated the advertising industry's role in American society, deflecting earlier criticism.[112] The media cooperated with the federal government in presenting the official view of the war. All movie scripts had to be pre-approved.[113] For example, there were widespread rumors in the Army to the effect that people on the homefront were slacking off. A Private SNAFU film cartoon (released to soldiers only) belied that rumor.[114] Tin Pan Alley produced patriotic songs to rally the people.[115]

Posters

Posters helped to mobilize the nation. Inexpensive, accessible, and ever-present, the poster was an ideal agent for making war aims the personal mission of every citizen. Government agencies, businesses, and private organizations issued an array of poster images linking the military front with the home front—calling upon every American to boost production at work and home. Some resorted to extreme racial and ethnic caricatures of the enemy, sometimes as hopelessly bumbling cartoon characters, sometimes as evil, half-human creatures.[116]

Bond drives

A strong aspect of American culture then as now was a fascination with celebrities, and the government used them in its eight war bond campaigns that called on people to save now (and redeem the bonds after the war, when houses, cars, and appliances would again be available).[117] The War Bond drives helped finance the war. Americans were challenged to put at least 10% of every paycheck into bonds.[118] Compliance was high, with entire workplaces earning a special "Minuteman" flag to fly over their plant if all workers belonged to the "Ten Percent Club".[119]

Hollywood

Hollywood studios also went all-out for the war effort, as studios encouraged their stars (such as Clark Gable and James Stewart) to enlist. Hollywood had military units that made training films—Ronald Reagan narrated many of them. Nearly all of Hollywood made hundreds of war movies that, in coordination with the Office of War Information (OWI), taught Americans what was happening and who the heroes and the villains were. Ninety million people went to the movies every week.[120] Some of the most highly regarded films during this period included Casablanca, Mrs. Miniver, Going My Way, and Yankee Doodle Dandy. Even before active American involvement in the war, the popular Three Stooges comic trio were lampooning the Nazi German leadership, and Nazis in general, with a number of short subject films, starting with You Nazty Spy! released in January 1940 - the very first Hollywood film of any length to satirize Hitler and the Nazis[121] - nearly two years before the United States was drawn into World War II.

Cartoons and short subjects were a major sign of the times, as Warner Brothers Studios and Disney Studios gave unprecedented aid to the war effort by creating cartoons that were both patriotic and humorous, and also contributed to remind movie-goers of wartime activities such as rationing and scrap drives, war bond purchases, and the creation of victory gardens. Warner shorts such as Daffy - The Commando, Draftee Daffy, Herr Meets Hare, and Russian Rhapsody are particularly remembered for their biting wit and unflinching mockery of the enemy (particularly Adolf Hitler, Hideki Tōjō, and Hermann Göring). Their cartoons of Private Snafu, produced for the military as "training films", served to remind many military men of the importance of following proper procedure during wartime, for their safety. MGM also contributed to the war effort with slyly pro-US short cartoon The Yankee Doodle Mouse with "Lt." Jerry Mouse as the hero and Tom Cat as the "enemy".

To heighten the suspense, Hollywood needed to feature attacks on American soil and obtained inspirations for dramatic stories from the Philippines. Indeed, the Philippines became a "homefront" that showed the American way of life threatened by the Japanese enemy. Especially popular were the films Texas to Bataan (1942), Corregidor (1943), Bataan (1943), They Were Expendable (1945), and Back to Bataan (1945).[122]

The OWI had to approve every film before they could be exported. To facilitate the process the OWI's Bureau of Motion Pictures (BMP) worked with producers, directors, and writers before the shooting started to make sure that the themes reflected patriotic values. While Hollywood had been generally nonpolitical before the war, the liberals who controlled OWI encouraged the expression of New Deal liberalism, bearing in mind the huge domestic audience, as well as an international audience that was equally large.[123]

Censorship

Prior to entering the war, the US government had already done two years of planning in terms of how to conduct censorship. Censorship would officially begun one hour after the Attack on Pearl Harbor which took place on December 7, 1941 censoring all cable, radiotelephone and telegraphic messages between the rest of the United States and Hawaii. Control of censorship was temporarily placed under FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover from December 8th to the 19th when the Office of Censorship was created via a presidential executive order with Byron Price leading the office for the duration of the war. Censorship was both practiced mandatorily and voluntarily depending on the circumstance. International communication was subjected to mandatory censorship while the domestic press participated on a voluntary basis as the federal government decided mandatory censorship would not be needed as long as patriotic broadcasters and publishers withheld any information that was deemed to harm the Allied war effort.[124]

The war would be covered by over 2,000 correspondents supplying their reports to newsreels, radios, magazines, newspapers and television which was an emerging technology. In the 1930s and 40s most Americans relied on print journalist to get their news.[125] The news was prohibited from covering the travels of the president, the location of the newly moved National Archives or any diplomatic or military missions.[124]

Local activism

One way to enlist everyone in the war effort was scrap collection (called "recycling" decades later). Many everyday commodities were vital to the war effort, and drives were organized to recycle such products as rubber, tin, waste kitchen fats (raw material for explosives), newspaper, lumber, steel, and many others. Popular phrases promoted by the government at the time were "Get into the scrap!" and "Get some cash for your trash" (a nominal sum was paid to the donor for many kinds of scrap items) and Thomas "Fats" Waller even wrote and recorded a song with the latter title. Such commodities as rubber and tin remained highly important as recycled materials until the end of the war, while others, such as steel, were critically needed at first. War propaganda played a prominent role in many of these drives. Nebraska had perhaps the most extensive and well-organized drives; it was mobilized by the Omaha World Herald newspaper.[126]

Sports

Auto racing

In July 1942, the Office of Defense Transportation ordered an indefinite ban on auto racing in an effort to conserve rubber and gasoline.[127][128]

Baseball

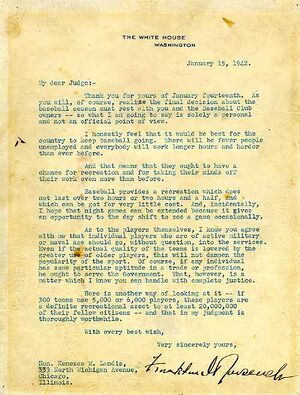

Baseball was at a peak in its popularity as the national pastime at the outset of the war. In January 1942, however, Commissioner of Baseball and former federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis handwrote a letter to President Roosevelt asking whether the President felt "professional baseball should continue to operate" given that "these are not ordinary times." Roosevelt wrote back the following day in what became known as the "Green Light Letter" that it would be "thoroughly worthwhile" and "best for the country to keep baseball going." He reasoned that the public would be working longer and harder hours than ever before and therefore had a greater need for recreation than ever before.[129]

In 1943 and 1944, Commissioner Landis, with input from Joseph Bartlett Eastman of the Office of Defense Transportation, ordered that all spring training take place north of the Potomac River and east of the Mississippi River in order to cut down on travel.[130] Major League Baseball (MLB) teams regularly played exhibition games to raise money and morale for the war effort, often against military teams; Ford Frick testified in 1951 before the House Judiciary Committee that MLB teams played 61 games on military bases between 1942 and 1944. The league raised more than $2.1 million (equivalent to $27.7 million in 2022).[130]

Because many of the able-bodied young men of the United States enlisted or were drafted into service, many MLB roster spots went to players deemed physically unfit for service.[131] They ranged from players such as Tommy Holmes, who had a chronic sinus condition,[131] to Pete Gray, who had only one arm.[131] Older stars such as Jimmie Foxx, Lloyd Waner, Ben Chapman, Babe Herman and Hal Trosky also found new playing opportunities and came out of retirement.[132][133][134]

Basketball

After the United States entered the war, the country's two professional basketball leagues, the American Basketball League and National Basketball League, both shrunk to four teams. Much of the country's best basketball was played on military bases.[135]

Football

More than 1,000 players left or postponed their professional football careers due to the war.[136] Due to the depletion of rosters, the Pittsburgh Steelers merged with the Philadelphia Eagles in 1943 to become the Steagles and with the Chicago Cardinals in 1944 to become Card-Pitt. In 1943, the Cleveland Rams suspended operations altogether.[137] During this time, due to the lack of well-rounded athletes available, the National Football League also began allowing free substitutions, which revolutionized the game.[138]

Golf

The U.S. Open was not held between 1942 and 1945 because of the scarcity of the rubber essential to the manufacture of golf balls.[139] Many of the nation's golf courses were also converted to more practical use. For example, Augusta National Golf Club was used to raise cows for beef for Camp Gordon and Congressional Country Club was used as a special ops training ground while several others were converted to farmland.[140]

Attacks on U.S. soil

Although the Axis powers never launched a full-scale invasion of the United States, there were attacks and acts of sabotage on U.S. soil.

- December 7, 1941 – Attack on Pearl Harbor, a surprise attack that killed almost 2,500 people in the then incorporated territory of Hawaii which caused the U.S. to enter the war the next day.

- January–August 1942 – Second Happy Time, German U-Boats engaged American ships off the U.S. East Coast.

- February 23, 1942 – Bombardment of Ellwood, a Japanese submarine attack on California.

- Attacks on California ships by Japanese submarines

- March 4, 1942 – Operation K, a Japanese reconnaissance over Pearl Harbor following the attack on December 7, 1941.

- June 3, 1942 – August 15, 1943 – Aleutian Islands Campaign, the battle for the then incorporated territory of Alaska.

- June 21–22, 1942 – Bombardment of Fort Stevens, the second attack on a U.S. military base in the continental U.S. in World War II.

- September 9, 1942, and September 29, 1942 – Lookout Air Raids, the only attack by enemy aircraft on the contiguous U.S. and the second enemy aircraft attack on the U.S. continent in World War II.

- November 1944–April 1945 – Fu-Go balloon bombs, over 9,300 of them were launched by Japan across the Pacific Ocean towards the U.S. to start forest fires. On May 5, 1945, six U.S. civilians were killed in Oregon when they stumbled upon a bomb and it exploded, the only deaths to occur in the U.S. as a result of an enemy balloon attack during World War II.

See also

- Ethnic minorities in the US armed forces during World War II

- American music during World War II

- G.I. Generation

- Home front during World War II, for rest of world

- Japanese occupation of the Philippines

- Military history of the United States during World War II

- United States home front during World War I

- Woman's Land Army of America

- California during World War II

- History of Texas § World War II

- US Government films:

Notes

- ^ Schneider, Carl G and Schneider, Dorothy; World War II; p. 57 ISBN 1438108907

- ^ Harold G. Vatter, The U.S. Economy in World War II (1988) pp. 27-31

- ^ David Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (2001) pp. 615-68

- ^ Franklin Roosevelt, Executive Order 9250 Establishing the Office of Economic Stabilization. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=16171#axzz1qK2AszpJ Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Carola Frydman and Raven Molloy, "Pay Cuts for the Boss: Executive Compensation in the 1940s," Journal of Economic History 72 (March 2012), 225–51.

- ^ Geoffrey Perrett, Days of sadness, months of triumph: the American people, 1939-1945: Volume 1 (1985) p. 300

- ^ Harvey C Mansfield, A short history of OPA (Historical reports on War Administration) (1951)

- ^ Paul A. C. Koistinen, Arsenal of World War II: The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1940-1945 (2004) pp. 498-517

- ^ Inflation existed because not all prices were controlled, and even when they were prices rose as "sales" disappeared, low-end items were less available, and quality deteriorated.

- ^ James J. Kimble, Mobilizing the Home Front: War Bonds And Domestic Propaganda (2006)

- ^ WPA workers were counted as unemployed. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract: 1946 (1946) p. 173

- ^ Miller and Cornford

- ^ Lee Kennett (1985). For the duration... : the United States goes to war, Pearl Harbor-1942. New York: Scribner. pp. 130–32. ISBN 978-0-684-18239-1.

- ^ "Smithtown's History - Alice Throckmorton McLean - Article Archive (Chronological) - Smithtown Matters - Online Local News about Smithtown, Kings Park, St James, Nesconset, Commack, Hauppauge, Ft. Salonga". www.smithtownmatters.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ "Alice Throckmorton McLean | American social service organizer". Encyclopedia Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) Chapter D, Labor, Series D 29-41

- ^ Susan Cahn, Coming On Strong. University of Illinois, 2015. Merrie A. Fidler, The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. McFarland, 2006. Sue Macy, A Whole New Ball game. Henry Holt, 1993.

- ^ Walter W. Wilcox, Farmer in the Second World War (1947)

- ^ أ ب Holt, Marilyn (2022). "On the Farm Front with the Victory Farm Volunteers". Agricultural History. Duke University Press. 96 (1–2): 164–186. doi:10.1215/00021482-9619828. S2CID 249657291. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ Kallen, Stuart A. (2000). The war at home. San Diego: Lucent Books. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-1-56006-531-9.

- ^ Otey M. Scruggs, 'Texas and the Bracero Program, 1942-1947,' Pacific Historical Review (1963) 32#3 pp. 251-264 in JSTOR Archived 2017-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Erasmo Gamboa, Mexican Labor & World War II: Braceros in the Pacific Northwest, 1942-1947 (2000)

- ^ Duane Ernest Miller, 'Barbed-Wire Farm Laborers: Michigan'S Prisoners of War Experience during World War II,' Michigan History, Sept 1989, Vol. 73 Issue 5, pp. 12-17

- ^ Kallen, Stuart A. (2000). The war at home. San Diego: Lucent Books. ISBN 978-1560065319.

- ^ "World War II: Civic responsibility" (PDF). Smithsonian Institution. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Hinshaw (1943)

- ^ Natsuki Aruga, " 'An 'finish school': Child labor during World War II." Labor History 29.4 (1988): 498-530 online.

- ^ Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) table H-424

- ^ Jaworski, Taylor (February 24, 2014). ""You're in the Army Now:" The Impact of World War II on Women's Education, Work, and Family". The Journal of Economic History. 74 (1): 169–195. doi:10.1017/S0022050714000060. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022 – via CambridgeCore.

- ^ Lichtenstein (2003)

- ^ Philip Taft, The A.F. of L. from the Death of Gompers to the Merger (1959) pp. 204-33

- ^ Paul A. C. Koistinen, Arsenal of World War II: The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1940-1945 (2004) p. 410

- ^ Melvyn Dubofsky and Warren Van Tine, John L. Lewis: A Biography (1977) pp. 415-44

- ^ William H. Holley et al. The Labor Relations Process (2008) p. 63

- ^ Martin Glaberman, Wartime Strikes: The Struggle Against the No Strike Pledge in the UAW During World War II (1980)

- ^ Andrew Kersten, Race, Jobs, and the War: The FEPC in the Midwest, 1941-46 (2000)

- ^ Campbell, Women at War with America ch 5

- ^ Morton Sosna, and James C. Cobb, Remaking Dixie: The Impact of World War II on the American South (UP of Mississippi, 1997).

- ^ Ralph C. Hon, "The South in a War Economy" Southern Economic Journal8#3 (1942), pp. 291-308 online Archived 2020-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ For comprehensive coverage see Dwight C. Hoover and B.U. Ratchford, Economic Resources and Policies of the South (1951).

- ^ Russell B. Olwell, At Work in the Atomic City: A Labor and Social History of Oak Ridge, Tennessee (2004.

- ^ Dewey W. Grantham, The South in modern America 1994) pp 172-183.

- ^ Tindall, The Emergence of the New South pp.694-701, quoting p. 701.

- ^ أ ب ت Campbell

- ^ أ ب Meghan K. Winchell, Good Girls, Good Food, Good Fun: The Story of USO Hostesses during World War II (2008)

- ^ Campbell, pp. 78-9, 226-7

- ^ Grace Palladino, Teenagers: An American History (1996) p. 66

- ^ Steven Mintz, Huck's Raft: A History of American Childhood (2006) pp. 258-9

- ^ Wheeler, Scott (May 2010). "Going to War with Milkweeds from Vermont". Vermont's Northland Journal. 9 (2): 19.

- ^ Flynn (1993)

- ^ the US Bureau of the Census; Bicentennial edition, Part 2, Chapter D, Labor, Series D 1-10

- ^ John P. Resch, ed., Americans at war: society, culture, and the homefront (2005) 3: 164-166.

- ^ Gerald I. Sittser, A cautious patriotism: The American Churches and the Second World War (U of North Carolina Press, 1985). online Archived 2020-01-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Mitchell K. Hall, 'A Withdrawal from Peace: The Historical Response to War of the Church of God (Anderson, Indiana),' Journal of Church and State (1985) 27#2 pp. 301–314

- ^ Thomas D. Hamm, et al., 'The Decline of Quaker Pacifism in the Twentieth Century: Indiana Yearly Meeting of Friends as a Case Study,' Indiana Magazine of History (2000) 96#1 pp. 45–71 online

- ^ Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941–1947 (1997) pp. 98–111

- ^ M. James Penton (1997). Apocalypse Delayed: The Story of Jehovah's Witnesses. U. of Toronto Press. p. 142. Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- ^ Martin, Kali (October 16, 2020). "Alternative Service: Conscientious Objectors and Civilian Public Service in World War II". The National WWII Museum. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ Scott H. Bennett, " American Pacifism, the 'Greatest Generation,' and World War II" in G. Kurt Piehler and Sidney Pash, The United States and the Second World War: New Perspectives on Diplomacy, War, and the Home Front (2010) pp 259–92 Online Archived 2020-01-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940–1947 (Cornell UP, 1952).

- ^ Wilson, J. H. (1980). "'"Peace is a woman's job" Jeannette Rankin and the Origins of American Foreign Policy'". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 30: 34.

- ^ Anderson, K. (1997). "Steps to Political Equality: Woman Suffrage and Electoral Politics in the Lives of Emily Newell Blair, Anne Henrietta Martin, and Jeannette Rankin". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 18 (1): 112. doi:10.2307/3347204. JSTOR 3347204.

- ^ Geoffrey Perrett, Days of sadness, years of triumph: the American people, 1939-1945: Volume 1 (1985) p. 218, 366

- ^ Michal R. Belknap, American political trials (1994) p. 182

- ^ Richard W. Steele, Free Speech in the Good War (1999) ch 13-14

- ^ Tuttle, William M. Jr. (1995). Daddy's Gone to War: The Second World War in the Lives of America's Children. Oxford University Press. pp. 59. ISBN 978-0-19-504905-3.

- ^ أ ب Flamm, Bradley (March 2006). "Putting the Brakes on 'Non-Essential' Travel: 1940s Wartime Mobility, Prosperity, and the US Office of Defense". Journal of Transport History. 27 (1). doi:10.7227/TJTH.27.1.6. S2CID 154113012 – via ResearchGate.