سويسرا

Swiss Confederation | |

|---|---|

النشيد: "Swiss Psalm" | |

موقع سويسرا (green) on the European continent (green and dark grey) | |

| العاصمة | 46°57′N 7°27′E / 46.950°N 7.450°E |

| أكبر مدينة | زيورخ |

| اللغات الرسمية | |

| الجماعات العرقية (2020)[5] |

|

| الدين |

|

| صفة المواطن | |

| الحكومة | Federal assembly-independent[7][8] directorial republic with elements of a direct democracy |

| Walter Thurnherr | |

| التشريع | Federal Assembly |

| Council of States | |

| National Council | |

| التاريخ | |

• تأسست | 1 August 1291[ث] |

• Sovereignty recognised (سلام وستفاليا) | 24 October 1648 |

| 7 أغسطس 1815 | |

| 12 September 1848[ج][9] | |

| المساحة | |

• الإجمالية | 41,285 km2 (15,940 sq mi) (132nd) |

• الماء (%) | 4.34 (2015)[10] |

| التعداد | |

• تقدير 2020 | |

• إحصاء 2015 | 8,327,126[12] |

• الكثافة | 207/km2 (536.1/sq mi) (48th) |

| ن.م.إ. (ق.ش.م.) | تقدير 2022 |

• الإجمالي | ▲ $739.49 billion[13] (35th) |

• للفرد | ▲ $84,658 [13] (5th) |

| ن.م.إ. (الإسمي) | تقدير 2022 |

• الإجمالي | ▲ $841.69 billion[13] (20th) |

• للفرد | ▲ $92,434[13] (7th) |

| جيني (2018) | ▼ 29.7[14] low |

| م.ت.ب. (2021) | ▲ 0.962[15] very high · 1st |

| العملة | Swiss franc (CHF) |

| التوقيت | UTC+1 (CET) |

• الصيفي (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| صيغة التاريخ | dd.mm.yyyy (AD) |

| جانب السواقة | right |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +41 |

| الإله الراعي | St Nicholas of Flüe |

| كود آيزو 3166 | CH |

| النطاق العلوي للإنترنت | .ch, .swiss |

سويسرا بالإنجليزية Switzerland ، رسمياً الاتحاد السويسري, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located at the confluence of Western, Central and Southern Europe.[ح][16] It is a federal republic composed of 26 cantons, with federal authorities based in Bern.[أ][3][2]

Switzerland is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. It is geographically divided among the Swiss Plateau, the Alps and the Jura, spanning 41,285 km2 (15,940 sq mi) with land area comprising 39,997 km2 (15,443 sq mi). The Alps occupy the greater part of the territory.

The Swiss population of approximately 8.7 million is concentrated mostly on the plateau, where the largest cities and economic centres are located, including Zürich, Geneva and Basel. These three cities are home to the headquarters or offices of international organisations such as the WTO, the WHO, the ILO, FIFA, and the United Nations's second-largest office.

Switzerland originates from the Old Swiss Confederacy that was established in the Late Middle Ages following a series of military successes against Austria and Burgundy. The Federal Charter of 1291 is considered the country's founding document, which is celebrated on Swiss National Day. Since the Reformation of the 16th century, Switzerland has maintained a policy of armed neutrality. Swiss independence from the Holy Roman Empire was formally recognised in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. Switzerland has not fought an international war since 1815. It joined the United Nations only in 2002, though it pursues an active foreign policy, including participation in frequent peace-building processes worldwide.[17] Switzerland is the birthplace of the Red Cross, one of the world's oldest and best-known humanitarian organisations. It is a founding member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), but not part of the European Union (EU), the European Economic Area or the Eurozone. However, it participates in the European single market and the Schengen Area through bilateral treaties.

Switzerland has four main linguistic and cultural regions: German, French, Italian and Romansh. Although the majority population are German-speaking, Swiss national identity is rooted in its common historical background, shared values such as federalism and direct democracy,[18] and Alpine symbolism.[19][20] This identity, which transcends language, ethnicity, and religion, has led to Switzerland being described as a Willensnation ("nation of volition") rather than a nation state.[21]

Due to its linguistic diversity, Switzerland is known by multiple native names: Schweiz [ˈʃvaɪts] (German);[خ][د] Suisse [sɥis(ə)] audio (French); Svizzera النطق بالإيطالية: [ˈzvittsera] (Italian); and Svizra قالب:IPA-rm (Romansh).[ذ] On coins and stamps, the Latin name, Confoederatio Helvetica – frequently shortened to "Helvetia" – is used instead of the spoken languages.

Switzerland is one of the world's most developed countries. It has the highest nominal wealth per adult of any country[22] and the eighth-highest gross domestic product per capita.[23][24] Switzerland ranks first in the Human Development Index since 2021, and it ranks highly also on several international metrics, including economic competitiveness and democratic governance. Its cities such as Zürich, Geneva and Basel rank among the highest in terms of quality of life,[25][26] albeit with some of the highest costs of living.[27]

Etymology

The English name Switzerland is a portmanteau of Switzer, an obsolete term for a Swiss person which was in use during the 16th to 19th centuries, and land.[28] The English adjective Swiss is a loanword from French Suisse, also in use since the 16th century. The name Switzer is from the Alemannic Schwiizer, in origin an inhabitant of Schwyz and its associated territory, one of the Waldstätte cantons which formed the nucleus of the Old Swiss Confederacy. The Swiss began to adopt the name for themselves after the Swabian War of 1499, used alongside the term for "Confederates", Eidgenossen (literally: comrades by oath), used since the 14th century. The data code for Switzerland, CH, is derived from Latin Confoederatio Helvetica (إنگليزية: Helvetic Confederation).

The toponym Schwyz itself was first attested in 972, as Old High German Suittes, perhaps related to swedan ‘to burn’ (cf. Old Norse svíða ‘to singe, burn’), referring to the area of forest that was burned and cleared to build.[29] The name was extended to the area dominated by the canton, and after the Swabian War of 1499 gradually came to be used for the entire Confederation.[30][31] The Swiss German name of the country, Schwiiz, is homophonous to that of the canton and the settlement, but distinguished by the use of the definite article (d'Schwiiz for the Confederation,[32] but simply Schwyz for the canton and the town).[33] The long [iː] of Swiss German is historically and still often today spelled ⟨y⟩ rather than ⟨ii⟩, preserving the original identity of the two names even in writing.

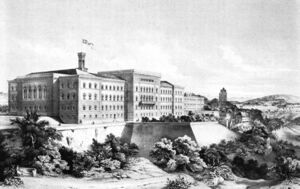

The Latin name Confoederatio Helvetica was neologised and introduced gradually after the formation of the federal state in 1848, harking back to the Napoleonic Helvetic Republic. It appeared on coins from 1879, inscribed on the Federal Palace in 1902 and after 1948 used in the official seal[34] (e.g., the ISO banking code "CHF" for the Swiss franc, and the country top-level domain ".ch", are both taken from the state's Latin name). Helvetica is derived from the Helvetii, a Gaulish tribe living on the Swiss Plateau before the Roman era.

Helvetia appeared as a national personification of the Swiss confederacy in the 17th century in a 1672 play by Johann Caspar Weissenbach.[35]

التاريخ

The state of Switzerland took its present form with the adoption of the Swiss Federal Constitution in 1848. Switzerland's precursors established a defensive alliance in 1291, forming a loose confederation that persisted for centuries.

البدايات

The oldest traces of hominid existence in Switzerland date to about 150,000 years ago.[36] The oldest known farming settlements in Switzerland, which were found at Gächlingen, date to around 5300 BC.[36]

The earliest known tribes formed the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures, named after the archaeological site of La Tène on the north side of Lake Neuchâtel. La Tène culture developed and flourished during the late Iron Age from around 450 BC,[36] possibly influenced by Greek and Etruscan civilisations. One of the most important tribal groups was the Helvetii. Steadily harassed by Germanic tribes, in 58 BC, the Helvetii decided to abandon the Swiss Plateau and migrate to western Gallia. Julius Caesar's armies pursued and defeated them at the Battle of Bibracte, in today's eastern France, forcing the tribe to move back to its homeland.[36] In 15 BC, Tiberius (later the second Roman emperor) and his brother Drusus conquered the Alps, integrating them into the Roman Empire. The area occupied by the Helvetii first became part of Rome's Gallia Belgica province and then of its Germania Superior province. The eastern portion of modern Switzerland was integrated into the Roman province of Raetia. Sometime around the start of the Common Era, the Romans maintained a large camp called Vindonissa, now a ruin at the confluence of the Aare and Reuss rivers, near the town of Windisch.[38]

The first and second century AD was an age of prosperity on the Swiss Plateau. Towns such as Aventicum, Iulia Equestris and Augusta Raurica, reached a remarkable size, while hundreds of agricultural estates (Villae rusticae) were established in the countryside.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Around 260 AD, the fall of the Agri Decumates territory north of the Rhine transformed today's Switzerland into a frontier land of the Empire. Repeated raids by the Alamanni tribes provoked the ruin of the Roman towns and economy, forcing the population to shelter near Roman fortresses, like the Castrum Rauracense near Augusta Raurica. The Empire built another line of defence at the north border (the so-called Donau-Iller-Rhine-Limes). At the end of the fourth century, the increased Germanic pressure forced the Romans to abandon the linear defence concept. The Swiss Plateau was finally open to Germanic tribes.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In the Early Middle Ages, from the end of the fourth century, the western extent of modern-day Switzerland was part of the territory of the Kings of the Burgundians. The Alemanni settled the Swiss Plateau in the fifth century and the valleys of the Alps in the eighth century, forming Alemannia. Modern-day Switzerland was then divided between the kingdoms of Alemannia and Burgundy.[36] The entire region became part of the expanding Frankish Empire in the sixth century, following Clovis I's victory over the Alemanni at Tolbiac in 504 AD, and later Frankish domination of the Burgundians.[39][40]

Throughout the rest of the sixth, seventh and eighth centuries, Swiss regions continued under Frankish hegemony (Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties) but after its extension under Charlemagne, the Frankish Empire was divided by the Treaty of Verdun in 843.[36] The territories of present-day Switzerland became divided into Middle Francia and East Francia until they were reunified under the Holy Roman Empire around 1000 AD.[36]

By 1200, the Swiss Plateau comprised the dominions of the houses of Savoy, Zähringer, Habsburg, and Kyburg.[36] Some regions (Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, later known as Waldstätten) were accorded the Imperial immediacy to grant the empire direct control over the mountain passes. With the extinction of its male line in 1263, the Kyburg dynasty fell in AD 1264. The Habsburgs under King Rudolph I (Holy Roman Emperor in 1273) laid claim to the Kyburg lands and annexed them, extending their territory to the eastern Swiss Plateau.[39]

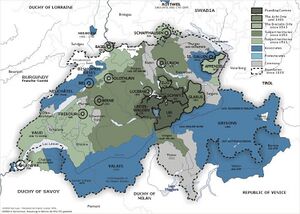

الاتحاد السويسري القديم

كان الاتحاد السويسري القديم تحالفاً بين مجتمعات وديان الألپ الأوسط. The Confederacy was governed by nobles and patricians of various cantons who facilitated management of common interests and ensured peace on mountain trade routes. The Federal Charter of 1291 is considered the confederacy's founding document, even though similar alliances likely existed decades earlier. The document was agreed among the rural communes of أوري، Schwyz, and Unterwalden.[41][42]

بحلول 1353، كانت الكانتونات الثلاث الأصلية قد انضمت إلى كانتونات گلاروس و تسوگ and the Lucerne, Zürich and Bern city-states to form the "Old Confederacy" of eight states that obtained through the end of the 15th century.[42] The expansion led to increased power and wealth for the confederation. By 1460, the confederates controlled most of the territory south and west of the Rhine to the Alps and the Jura mountains, and the University of Basel was founded (with a faculty of medicine) establishing a tradition of chemical and medical research. This increased after victories against the Habsburgs (Battle of Sempach, Battle of Näfels), over Charles the Bold of Burgundy during the 1470s, and the success of the Swiss mercenaries. النصر السويسري في الحرب السوابية ضد العصبة السوابية للإمبراطور ماكسميليان الأول في 1499 عـُدَّت استقلال أمر واقع ضمن الامبراطورية الرومانية المقدسة.[42] وفي 1501، Basel[43] and Schaffhausen joined the Old Swiss Confederacy.[44]

The Confederacy acquired a reputation of invincibility during these earlier wars, but توسع الاتحاد suffered a setback in 1515 with the Swiss defeat in the معركة مارينيانو. This ended the so-called "heroic" epoch of Swiss history.[42] The success of Zwingli's Reformation in some cantons led to inter-cantonal religious conflicts in 1529 and 1531 (Wars of Kappel). It was not until more than one hundred years after these internal wars that, in 1648, under the Peace of Westphalia, European countries recognised Switzerland's independence from the Holy Roman Empire and its neutrality.[39][40]

During the Early Modern period of Swiss history, the growing authoritarianism of the patriciate families combined with a financial crisis in the wake of the حرب الثلاثين عام أدت إلى حرب الفلاحين السويسرية 1653. في خلفية هذا الصراع، تواصَل الصراع بين الكانتونات الكاثوليكية والپروتستانتية، وانفجر في مزيد من العنف في First War of Villmergen، في 1656، وToggenburg War (or Second War of Villmergen), in 1712.[42]

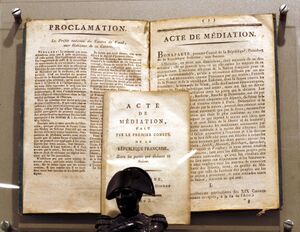

Napoleonic era

In 1798, the revolutionary French government invaded Switzerland and imposed a new unified constitution.[42] This centralised the government of the country, effectively abolishing the cantons: moreover, Mülhausen left Switzerland and the Valtellina valley became part of the Cisalpine Republic. The new regime, known as the Helvetic Republic, was highly unpopular. An invading foreign army had imposed and destroyed centuries of tradition, making Switzerland nothing more than a French satellite state. The fierce French suppression of the Nidwalden Revolt in September 1798 was an example of the oppressive presence of the French Army and the local population's resistance to the occupation.[بحاجة لمصدر]

When war broke out between France and its rivals, Russian and Austrian forces invaded Switzerland. The Swiss refused to fight alongside the French in the name of the Helvetic Republic. In 1803 Napoleon organised a meeting of the leading Swiss politicians from both sides in Paris. The Act of Mediation was the result, which largely restored Swiss autonomy and introduced a Confederation of 19 cantons.[42] Henceforth, much of Swiss politics would concern balancing the cantons' tradition of self-rule with the need for a central government.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In 1815 the Congress of Vienna fully re-established Swiss independence, and the European powers recognised permanent Swiss neutrality.[39][40][42] Swiss troops served foreign governments until 1860 when they fought in the siege of Gaeta. The treaty allowed Switzerland to increase its territory, with the admission of the cantons of Valais, Neuchâtel and Geneva. Switzerland's borders saw only minor adjustments thereafter.[45]

Federal state

The restoration of power to the patriciate was only temporary. After a period of unrest with repeated violent clashes, such as the Züriputsch of 1839, civil war (the Sonderbundskrieg) broke out in 1847 when some Catholic cantons tried to set up a separate alliance (the Sonderbund).[42] The war lasted less than a month, causing fewer than 100 casualties, most of which were through friendly fire. The Sonderbundskrieg had a significant impact on the psychology and society of Switzerland.[بحاجة لمصدر][من؟]

The war convinced most Swiss of the need for unity and strength. Swiss from all strata of society, whether Catholic or Protestant, from the liberal or conservative current, realised that the cantons would profit more from merging their economic and religious interests.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Thus, while the rest of Europe saw revolutionary uprisings, the Swiss drew up a constitution that provided for a federal layout, much of it inspired by the American example. This constitution provided central authority while leaving the cantons the right to self-government on local issues. Giving credit to those who favoured the power of the cantons (the Sonderbund Kantone), the national assembly was divided between an upper house (the Council of States, two representatives per canton) and a lower house (the National Council, with representatives elected from across the country). Referendums were made mandatory for any amendments.[40] This new constitution ended the legal power of nobility in Switzerland.[46]

A single system of weights and measures was introduced, and in 1850 the Swiss franc became the Swiss single currency, complemented by the WIR franc in 1934.[47] Article 11 of the constitution forbade sending troops to serve abroad, marking the end of foreign service. It came with the expectation of serving the Holy See, and the Swiss were still obliged to serve Francis II of the Two Sicilies with Swiss Guards present at the siege of Gaeta in 1860.[بحاجة لمصدر]

An important clause of the constitution was that it could be entirely rewritten if necessary, thus enabling it to evolve as a whole rather than being modified one amendment at a time.[48]

This need soon proved itself when the rise in population and the Industrial Revolution that followed led to calls to modify the constitution accordingly. The population rejected an early draft in 1872, but modifications led to its acceptance in 1874.[42] It introduced the facultative referendum for laws at the federal level. It also established federal responsibility for defence, trade, and legal matters.

In 1891, the constitution was revised with unusually strong elements of direct democracy, which remain unique today.[42]

Modern history

Switzerland was not invaded during either of the world wars. During World War I, Switzerland was home to the revolutionary and founder of the Soviet Union Vladimir Illych Ulyanov (Vladimir Lenin) who remained there until 1917.[49] Swiss neutrality was seriously questioned by the short-lived Grimm–Hoffmann affair in 1917. In 1920, Switzerland joined the League of Nations, which was based in Geneva, after it was exempted from military requirements.[بحاجة لمصدر]

During World War II, detailed invasion plans were drawn up by the Germans,[50] but Switzerland was never attacked.[51] Switzerland was able to remain independent through a combination of military deterrence, concessions to Germany, and good fortune, as larger events during the war intervened.[52][53] General Henri Guisan, appointed the commander-in-chief for the duration of the war ordered a general mobilisation of the armed forces. The Swiss military strategy changed from static defence at the borders to organised long-term attrition and withdrawal to strong, well-stockpiled positions high in the Alps, known as the Reduit. Switzerland was an important base for espionage by both sides and often mediated communications between the Axis and Allied powers.[53]

Switzerland's trade was blockaded by both the Allies and the Axis. Economic cooperation and extension of credit to Nazi Germany varied according to the perceived likelihood of invasion and the availability of other trading partners. Concessions reached a peak after a crucial rail link through Vichy France was severed in 1942, leaving Switzerland (together with Liechtenstein) entirely isolated from the wider world by Axis-controlled territory. Over the course of the war, Switzerland interned over 300,000 refugees[54] aided by the International Red Cross, based in Geneva. Strict immigration and asylum policies and the financial relationships with Nazi Germany raised controversy, only at the end of the 20th century.[55]

During the war, the Swiss Air Force engaged aircraft of both sides, shooting down 11 intruding Luftwaffe planes in May and June 1940, then forcing down other intruders after a change of policy following threats from Germany. Over 100 Allied bombers and their crews were interned. Between 1940 and 1945, Switzerland was bombed by the Allies, causing fatalities and property damage.[53] Among the cities and towns bombed were Basel, Brusio, Chiasso, Cornol, Geneva, Koblenz, Niederweningen, Rafz, Renens, Samedan, Schaffhausen, Stein am Rhein, Tägerwilen, Thayngen, Vals, and Zürich. Allied forces maintained that the bombings, which violated the 96th Article of War, resulted from navigation errors, equipment failure, weather conditions, and pilot errors. The Swiss expressed fear and concern that the bombings were intended to put pressure on Switzerland to end economic cooperation and neutrality with Nazi Germany.[56] Court-martial proceedings took place in England. The U.S. paid SFR 62,176,433.06 for reparations.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Switzerland's attitude towards refugees was complicated and controversial; over the course of the war, it admitted as many as 300,000 refugees[54] while refusing tens of thousands more,[57] including Jews persecuted by the Nazis.[58]

After the war, the Swiss government exported credits through the charitable fund known as the Schweizerspende and donated to the Marshall Plan to help Europe's recovery, efforts that ultimately benefited the Swiss economy.[59]

During the Cold War, Swiss authorities considered the construction of a Swiss nuclear bomb.[60] Leading nuclear physicists at the Federal Institute of Technology Zürich such as Paul Scherrer made this a realistic possibility.[61] In 1988, the Paul Scherrer Institute was founded in his name to explore the therapeutic uses of neutron scattering technologies.[62] Financial problems with the defence budget and ethical considerations prevented the substantial funds from being allocated, and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1968 was seen as a valid alternative. Plans for building nuclear weapons were dropped by 1988.[63] Switzerland joined the Council of Europe in 1963.[52]

Switzerland was the last Western republic (the Principality of Liechtenstein followed in 1984) to grant women the right to vote. Some Swiss cantons approved this in 1959, while at the federal level, it was achieved in 1971[51][64] and, after resistance, in the last canton Appenzell Innerrhoden (one of only two remaining Landsgemeinde, along with Glarus) in 1990. After obtaining suffrage at the federal level, women quickly rose in political significance. The first woman on the seven-member Federal Council executive was Elisabeth Kopp, who served from 1984 to 1989,[51] and the first female president was Ruth Dreifuss in 1999.[65]

In 1979 areas from the canton of Bern attained independence from the Bernese, forming the new canton of Jura. On 18 April 1999, the Swiss population and the cantons voted in favour of a completely revised federal constitution.[51]

In 2002 Switzerland became a full member of the United Nations, leaving Vatican City as the last widely recognised state without full UN membership. Switzerland is a founding member of the EFTA but not the European Economic Area (EEA). An application for membership in the European Union was sent in May 1992, but did not advance since rejecting the EEA in December 1992[51] when Switzerland conducted a referendum on the EEA. Several referendums on the EU issue ensued; due to opposition from the citizens, the membership application was withdrawn. Nonetheless, Swiss law is gradually changing to conform with that of the EU, and the government signed bilateral agreements with the European Union. Switzerland, together with Liechtenstein, has been surrounded by the EU since Austria's entry in 1995. On 5 June 2005, Swiss voters agreed by a 55% majority to join the Schengen treaty, a result that EU commentators regarded as a sign of support.[52] In September 2020, a referendum calling for a vote to end the pact that allowed a free movement of people from the European Union was introduced by the Swiss People's Party (SPP).[66] However, voters rejected the attempt to retake control of immigration, defeating the motion by a roughly 63%–37% margin.[67]

On 9 February 2014, 50.3% of Swiss voters approved a ballot initiative launched by the Swiss People's Party (SVP/UDC) to restrict immigration. This initiative was mostly backed by rural (57.6% approval) and suburban groups (51.2% approval), and isolated towns (51.3% approval) as well as by a strong majority (69.2% approval) in Ticino, while metropolitan centres (58.5% rejection) and the French-speaking part (58.5% rejection) rejected it.[68] In December 2016, a political compromise with the EU was attained that eliminated quotas on EU citizens, but still allowed favourable treatment of Swiss-based job applicants.[69] On 27 September 2020, 62% of Swiss voters rejected the anti-free movement referendum by SVP.[70]

Etymology

The English name Switzerland is a portmanteau of Switzer, an obsolete term for a Swiss person which was in use during the 16th to 19th centuries, and land.[71] The English adjective Swiss is a loanword from French Suisse, also in use since the 16th century. The name Switzer is from the Alemannic Schwiizer, in origin an inhabitant of Schwyz and its associated territory, one of the Waldstätte cantons which formed the nucleus of the Old Swiss Confederacy. The Swiss began to adopt the name for themselves after the Swabian War of 1499, used alongside the term for "Confederates", Eidgenossen (literally: comrades by oath), used since the 14th century. The data code for Switzerland, CH, is derived from Latin Confoederatio Helvetica (إنگليزية: Helvetic Confederation).

The toponym Schwyz itself was first attested in 972, as Old High German Suittes, perhaps related to swedan ‘to burn’ (cf. Old Norse svíða ‘to singe, burn’), referring to the area of forest that was burned and cleared to build.[72] The name was extended to the area dominated by the canton, and after the Swabian War of 1499 gradually came to be used for the entire Confederation.[73][74] The Swiss German name of the country, Schwiiz, is homophonous to that of the canton and the settlement, but distinguished by the use of the definite article (d'Schwiiz for the Confederation,[75] but simply Schwyz for the canton and the town).[76] The long [iː] of Swiss German is historically and still often today spelled ⟨y⟩ rather than ⟨ii⟩, preserving the original identity of the two names even in writing.

The Latin name Confoederatio Helvetica was neologised and introduced gradually after the formation of the federal state in 1848, harking back to the Napoleonic Helvetic Republic. It appeared on coins from 1879, inscribed on the Federal Palace in 1902 and after 1948 used in the official seal[77] (e.g., the ISO banking code "CHF" for the Swiss franc, and the country top-level domain ".ch", are both taken from the state's Latin name). Helvetica is derived from the Helvetii, a Gaulish tribe living on the Swiss Plateau before the Roman era.

Helvetia appeared as a national personification of the Swiss confederacy in the 17th century in a 1672 play by Johann Caspar Weissenbach.[78]

الموقع

تقع سويسرا في جنوبي أوروبا الوسطي ، تحدها ألمانيا من الشمال ، وايطاليا من الجنوب ، والنمسا من الشرق ، وتشغل أرضها قسماً من جبال الألب ، وجبال جورا ، ولموقعها إهميتة في وسط قارة أوروبا ، حيث ممرات جبال الألب التي تربط بين العديد من الدول الأوروبية .

مظاهر السطح

أرض سويسرا جبلية في جملتها ، فحوالي 60% من مساحتها من المرتفعات الألبية ، وهذا القطاع يضم 20% من السكان وتنحدر بمقدمات نحو الهضبة السويسرية ، وتضم هذه المقدمات عدة بحيرات ، وتنقسم جبال الألب إلى عدة سلاسل ، وأعلى قمة في الألب السويسرية (مونتي روزا ) وتشغل سويسرا قسماً من جبال جورا حيث يتبعها القسم الجنوبي الشرقي من هذه الجبال ، وتحتوي العديد من الأودية والحافات ، وتخترقها بعض الممرات ، وتمتد الهضبة السويسرية على شكل دهليز بين جبال الألب وجبال جورا ، ويختلف ارتفاع الهضبة من مكان إاى آخر ، وقد اعطتها طبيعتها الجبلية الغنية بالغابات قيمة سياحية عظيمة .وتنحصر الجبال بين العديد من الثلاجات مثل (الينش ) و(جورنرفيزتش) ، وهذه الثلاجات مصدر سياحي هام ، وتنتشر بسويسرا البحيرات العذبة .

المناخ

ينتمي مناخ سويسرا إلى طراز وسط اوروبا (المناخ الألبي ) والناخ بارد بصفة عامة حيث تغطي الثلوج معظم أرضها في الشتاء وتتحول إلى ثلاجات استغلها السويسريون في السياحة لمزاولة الانزلاق على الجليد ، وتهب من الجبال (الفهن ) إلى الأودية ، فتؤثر قي مناخ المناطق المنخفضة ، والتساقط غزير ، ويسودها صيف دافيء فب المناطق الهضبية وعلى الأودية المنخفضة .

السكان

يعيش معظم سكان سويسرا في مناطق الهضاب وفي المدن الرئيسية ، مثل زيورخ ،وبازل ، وجنيف ، ولوزان ، ويقل الكثافة السكانية على المرتفعات ، وينتمي السكان إلى الجماعات الألمانية ، ويشكلون أغلب سكان سويسرا ، ويتحدث 75% من السكان الألمانية ،ومن بين السكان عناصر قرنسية فحوالي 20% من جملة السكان يتحدثون الفرنسية ، كما س توجد عناصر إيطالية وحوالي 4% من السكان يتحدثون الإيطالية ، ويوجد بين السويسريين عدد كبير من الأجانب يقارب مليون نسمة .

النشاط البشري

سويسرا دولة متقدمة ، ترتفع دخول الفرد إلى مستوي عال ، ويعود هذا لكثرة الأنشطة الاقتصادية متمارس الزراعة في الوديان المنخفضة وفوق الهضبة الوسطي ، وتبلغ نسبة العاملين بالزراعة حوالي 4% من القوة العاملة ، وتنتج سويسرا 50% من حاجتها من المواد الزراعية ، وأهم الغلات الحبوب ، مثل القمح والشيلم والجودار والبطاطس والفاكهه مثل التفاح والعنب والزراعة مختلطة أي تربي الحيوانات في مناطق الزراعة ، مما يزيد س دخل المزارعين وهناك حركة الرعي على سفوح الجبال في فصل الصيف ، وتشتهر سويسرا بمنتجات الألبان ، وتصدر للخارج كميات كبيرة ، ولاتفي الزراعة بحاجة السكان ، وتغطي الغابات مساحات كبيرة في الأراضي السويسرية ، غير أن البلاد فقيرة الثروة المعدنية ، وكذلك وضعها في مواد الطاقة ، غير أنها غنية بالقوة الكهربائية المولدة من المساقط المائية ، وتشتهر بالصناعات الدقيقة كالساعات ، والآلات الدقيقة ،والأدوات الطبية ، والكيميائيات ، والأدوات الكهربائية ، وتعتبر الصناعة دعامة الدخل القومي السويسري ، وتشكل السياحة موردا هاما في الدخل السويسري .

اللغة

يوجد في سويسرا أربع لغات رسمية: الألمانية، الفرنسية، الإيطالية، الرومانشية. يتحدث غالبية سكان شمال ووسط سويسرا بالألمانية، الفرنسية في الغرب، الإيطالية في الجنوب و الرومانشية في المناطق الجبلية الوسطى.

الديانات في سويسرا

سويسرا هي بلد علماني بطبيعته ولكن الديانة الشائعة في هذا البلد هي المسيحية, بكلا المذهبين البروتستانتي والكاثوليكي, ولكن الأغلبية في سويسرا هم من البرتستانت, وتأتي بعد الديانة المسيحية, الاسلام حيث إن المهاجرين من تركيا ودول البلقان أتوا بدينهم الى هذا البلد وهناك الكثير من السويسريين الذين تحولوا الى الديانة الإسلامية, وتبلغ نسبة المسلمين في هذا البلد ما يقارب الـ10%, ومن ثم تأتي الديانة اليهودية والبوذية.

الأعياد و العطل

تختلف أيام العطل الرسمية في سويسرا من كانتون إلى آخر. واليك أدناه لائحة تتضمن أهم الأعياد في الكونفدرالية. الفاتح من يناير / كانون الثاني. يوم الجمعة الحزين. أحد الفصح. اثنين الفصح. الفاتح من مايو/أيار. يحتفل به فقط في بعض الكانتونات مثل مدينة بازل وجنيف وزيوريخ. عيد الصعود أو خميس الصعود. أحد العنصرة. اثنين العنصرة. (عيد الجسد أو عيد القربان) تحتفل به الكانتونات الكاثوليكية فقط. (الفاتح من أغسطس آب. ) العيد الوطني للكونفدرالية. (الـ15 من أغسطس/آب ) عيد الصعود في الكانتونات الكاثوليكية. (الأحد الثاني من شهر سبتمبر/ أيلول ) اليوم الفدرالي للصلاة. (الفاتح من نوفمبر/ تشرين الثاني ) عيد جميع القديسين، فقط في الكانتونات الكاثوليكية. الـ25 من ديسمبر/ كانون الأول. الـ26 من ديسمبر/ كانون الأول.

التقسيمات الإدارية

مقالة مفصلة: كانتونات سويسرا

مقالة مفصلة: كانتونات سويسرا

تتكون سويسرا من 26 كانتون:

السياسة

النظام السياسي

في سويسرا، كما في معظم دول سيادة القانون، تفصل السلطات بين ثلاث مجالات: التشريعي، والتنفيذي والقضائي.

السلطة التشريعية (البرلمان) هي المُشرع. غرفتا البرلمان (مجلس النواب ومجلس الشيوخ) تناقشان تعديلات الدستور، وتصدران القوانين الفدرالية، والمراسيم الفدرالية، وتقبلان معاهدات القانون العام. كما تنتخبان أعضاء الحكومة الفدرالية وتراقبان الإدارة الفدرالية.

تتكون السلطة التنفيذية من الحكومة الفدرالية وإدارتها. تمثل أعلى سلطة قيادية في البلاد وهي مسؤولة عن النشاط الحكومي. تشارك أيضا في العملية التشريعية بتوجيه المرحة التحضيرية خلال بلورة القوانين، وبتقديم القوانين والمراسيم الفدرالية إلى البرلمان.

أما السلطة القضائية، التي تسمى أيضا السلطة الثالثة، فهي تتألف من المحاكم. وعلى المستوى الفدرالي، يتعلق الأمر بالمحكمة الفدرالية والمحكمة الجنائية الفدرالية والمحكمة الإدارية الفدراليية

السياسة الخارجية

حمت السياسة الخارجية المحايدة الصارمة سويسرا من ويلات الحروب اللتي عصفت بأوروبا على مدى القرون الماضية. أصبحت سويسرا عضواً عام 1960 في لمنظمة التجارة الحرة الاوروبية (EFTA) و عام 1963 في المجلس الاوروبي. رفض السويسريون الانضمام الى الاتحاد الاوروبي في إستفتاء أُقيم عام [[1992]

الاقتصاد

لا تحظى سويسرا عموما بثقل سياسي كبير. لكن على المستوى التجاري، تُصنف الكنفدرالية ضمن الدول ذات الاقتصاديات المتوسطة في العالم.

في غياب الموارد الطبيعية - باستثناء مياه الكتل الجليدية والبحيرات والأنهار، يعتمد الاقتصاد السويسري كليا على الصادرات، التي تتميز بقيمة مضافة عالية.

وباستثناء بعض المُدن الدولية القليلة، ربما لا توجد دول أخرى يعتمد ازدهارها بهذا القدر الكبير على الصناعات التصديرية. وتحتل سويسرا المرتبة 15 في قائمة أكبر الدول المُصدرة على المستوى العالمي.

وفي العادة، لا تتطلع كبريات الشركات السويسرية، مثل تلك النشيطة في قطاع الصناعة الصيدلية، إلى بيع أكثر من 2% من إنتاجها في السوق السويسرية.

في بداية الحقبة الصناعية، استفاد السويسريون من وفرة المياه لتشغيل مطاحن مصانع النسيج. وكانت المياه الوفيرة أيضا ركيزة أساسية لصناعة الصبغ والطلاء التي قام عليها لاحقا قطاع الصناعة الصيدلية في مدينة بازل.

الـصناعة

أدى التقدم التكنولوجي في مجال توليد الطاقة الهيدرولوجية إلى ظهور شركاتِ هـندسة سويسرية ثقيلة شيـّدت محطاتٍ لـتوليد الطاقة، وصنعت مراكب تعمل بمحرك الديزل وقاطرات كهربائية كانت تـُصدَّر إلى مختلف أرجاء العالم.

وحفزت الثلوج الكثيفة خلال أشهر الشتاء الباردة المزارعين على محاولة تصنيع الساعات بدل الاستسلام لجو الخمول الشتوي.

وتُجسِّد الساعة جيدا تصوُّر "القيمة المضافة" الذي يعتمد عليه الاقتصاد السويسري. فالشركات السويسرية لا تميل إلى خيار الإنتاج الكثيف للمواد الاستهلاكية الرخيصة، لأن ذلك قد يضطرها إلى استيراد كميات هائلة من المواد الخام المُكلفة لتصنيعها. وقد لا ترتفع القيمة الصافية لتلك المنتجات بشكل ملموس لدى تصديرها لمنافسة الأسواق العالمية.

أما تكاليف المواد الخام لتصنيع ساعة تُباع بـ100 أو 3000 فرنك، فلا تختلف كثيرا. غير أن العمل الذي يـُستثمر في تصميم وإنتاج وتسويق الساعة يفرض فرقا هائلا.

نفسُ الشيء ينطبق على الشركات السويسرية الصغيرة التي تـُنتج الزيت المُشغل لمحركات الساعات، إذ تقوم بتكرير تلك المادة الخام إلى أقصى حد حتى أن سعر المنتوج النهائي يضاهي ثمن الذهب أو الكافيار.

رغم توفـُّر سويسرا على شركات عملاقة مثل مجموعة "نستلي" للصناعات الغذائية، والشركات الصيدلية مثل "نوفارتيس" و"روش"، ومصارف مثل "اتحاد المصارف السويسرية" (UBS) و"كريدي سويس"، وشركات التأمين مثل "زيورخ"، فلا تُمثل هذه الشركات في الواقع سويسرا كدولة صناعية، إذ أن ثلثي الإنتاج الاقتصادي للبلاد يعتمد بنسبة 98% على الشركات التي تـُوظف أقل من 50 شخصا.

تـُشغل الشركات المتوسطة والصُّغرى 1,45 مليون شخص، أي أكثر من نصف إجمالي من لا يعملون لحساب القطاع العمومي. زهاء 750 شركة فقط تتوفر على يد عاملة تتجاوز 250 شخصا، لكنها لا تمثل سوى 30% من مجموع القوى العاملة في البلد.

سويسرا والاتحاد الاوروبى

سويسرا ليست عضوا في الاتحاد الأوروبي. وقد تتعزز الحظوظ لانضمام الكنفدرالية إليه إذا ما اقتنعت يوما ما غالبية السويسريين بان الاتحاد الأوروبي مستقر وراسخ.

في ديسمبر 1992، صوت الناخبون السويسريون ضد الانضمام للمجال الاقتصادي الأوروبي. أما البلدان الثلاثة الأخرى الأعضاء في الرابطة الأوروبية للتبادل التجاري الحر إلى جانب سويسرا، وهي ايسلندا وإمارة ليختنشتاين والنرويج، فقد اختارت الانضمام إلى المجال الاقتصادي الأوروبي، رغم أن الرابطة لا زالت قائمة.

ويبقى الانضمام إلى الاتحاد الأوروبي من أهداف الحكومة السويسرية. وكانت الكنفدرالية قد تقدمت بطلب الانضمام إلى بروكسل، لكن هذه الأخيرة جمدت طلب برن بعدما رفض الناخبون السويسريون الانضمام إلى المجال الاقتصادي الأوروبي.

في ظل نظام الديمقراطية المباشرة في سويسرا، يستدعي طلب العضوية إلى الاتحاد الأوروبي موافقة غالبية الناخبين وغالبية الكانتونات السويسرية الستة والعشرين.

في الوقت الحاضر، تدرك الحكومة أن نسبة المؤيدين والمعارضين للانضمام إلى أوروبا قد تكون متساوية في حال إجراء استفتاء شعبي حول الموضوع.

ويستند الموقف السويسري الفاتر من الاتحاد الأوروبي إلى عدة عوامل، لعل أبرزها النظر إليه كمنظومة تفتقر للمؤسسات الديمقراطية. فنظام الديمقراطية المباشرة السويسري الذي يقتضي اللجوء باستمرار إلى المبادرات والاستفتاءات الشعبية قد يتطلب إصلاحات وتعديلات جذرية ليتماشى مع القواعد المعمول بها في الاتحاد الأوروبي.

وهنالك القلق أيضا من تكاليف الانضمام: فقد تتحول سويسرا إلى دولة مساهمة بشكل صاف (ربما الدولة الأخيرة) في صناديق الاتحاد. وتحوم شكوك أيضا حول ما إذا كان الحياد السويسري سيتوافق مع العضوية في الاتحاد الأوروبي.

التوزيع السكاني

الطاقة

استخدام الطاقة الهيدروليكية في أنتاج الكهرباء يوفر 13% من احتياجات سويسرا من الطاقة. تستفيد الكانتونات الجبلية من استخراج الكهرباء بواسطة الطاقة المائية بما قيمته 11 مليار فرنك سنويا. توجد أكثر من نصف محطات توليد الكهرباء من الطاقة الهيدروليكية توجد في كانتونات غراوبوندن أقصى الشرق، وتيتشينو وفاليس في الجنوب وأوري في وسط سويسرا. تقوم سويسرا منذ منتصف السبعينيات بتصدير جزء من الكهرباء المنتجة من الطاقة المائية إلى بعض دول أوروبا، وتمثل بذلك مركزا هاما لتصدير الطاقة.

الثقافة

المسرح

تتميز سويسرا بتقليد عريق وثري في المجال المسرحي. بازل، برن، زيورخ وجنيف أنتجت أعمالا ذاع صيتها خارج حدودها.

وتحظى المسارح الكبرى بحصة الأسد من الميزانيات المخصصة للفنون في مدنها. لكن هنالك أيضا عدة مسارح صغيرة متخصصة في الأعمال الكلاسيكية، أو الكوميدية، إضافة إلى بعض الأعمال الثانوية.

تعرض المسارح السويسرية أيضا أعمالا كثيرة في الهواء الطلق رغم الأحوال الجوية المضطربة في غالب الأحيان.

توجد العديد من المنصات في الهواء الطلق لعرض إنتاجات كبرى مثل "ويليام تيل" في انترلاكن، والـ"المسرح العالمي" لكالدرون كل عشرة أعوام في أيْنسيلدن، فضلا عن "حفل مزارعي الكروم" (Fête des Vignerons) التي تُخلد كل خمسة وعشرين عاما تقريبا الحياة الريفية لمنتجي النبيذ في مدينة فوفي وضواحيها على ضفاف بحيرة ليمان، التي تُسمى أيضا بحيرة جنيف.

معظم المسرحيات والإنتاجات الدرامية السويسرية لها جذور محلية أو لغوية. لكن فريدريش دورنمات تجاوز تلك التضييقات ليكتسب شهرة عالمية ككاتب مسرحي.

ديمتري - المهرج من كانتون تينشينو الجنوبي المتحدث بالإيطالية - صنع اسمه كفنان على خشبة المسرح. وأسس مدرسة للمهرجين في بلدة فيرشو حصلت حديثا على وضع يعادل مستوى الجامعات

الموسيقى

صنع العديدُ من السويسريين لأنفسهم أسماء في مجال الموسيقى الكلاسيكية العالمية: أرتور هونيغير وأوتمار شويك كانا مؤلفين موسيقيين مقتدرين. قضى هونيغير معظم حياته في فرنسا حيث كان من بين المؤلفين الطلائعيين آنذاك (في بدايات القرن العشرين).

أما قائد الأوركسترا إرنست أنسيرميت، فقد ارتبط اسمه بأوركسترا سويسرا الروماندية التي أسسها.

شارل دوتوا وماتياس بامير اشتهرا أيضا على المستوى الدولي كقائدي أوركسترا.

أصبحت موسيقى الجاز شعبية في سويسرا بعد الثلاثينات. واحتفاء بها، نظمت لها مدن مونترو وويلساو ولوغانو مهرجانات شعبية، من أشهرها مهرجان الجاز الدولي في مونترو. أما العاصمة برن، فتتوفر على مدرسة معروفة لموسيقى الجاز.

وتشتهر سويسرا خلال موسم الصيف بتنظيم عدد كبير من التظاهرات الموسيقية في الهواء الطلق، بدء بالموسيقى الشعبية والفلكلورية ووصولا إلى المهرجانات الموسيقية الكلاسيكية.

الرياضة

انظر أيضا

- الألب السويسرية

- 2004 في سويسرا, 2005 في سويسرا

- سويسرا والإتحاد الأوروبي

- توسيع الإتحاد الأوروبي- سويسرا

- العلاقات الخارجية في سويسرا

- قائمة مدن سويسرا

- المواطنة السويسرية

- يوم سويسرا القومي

- الإتصالات في سويسرا

- Data codes for Switzerland

- التعليم في سويسرا

- Gun politics in Switzerland

- الجيش في سويسرا

- العطلات العامة في سويسرا

- النقل في سويسرا

- قائمة الشركات السويسرية

- قائمة مواضيع متعلقة بسويسرا

- الفن الشعبي السويسري

- أماكن الجذب في سويسرا

المصادر

- ^ Confoederatio helvetica in the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland

- ^ أ ب ت Georg Kreis: Federal city in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland. Version of 20 March 2015.

- ^ أ ب Holenstein, André (2012). "Die Hauptstadt existiert nicht". UniPress – Forschung und Wissenschaft an der Universität Bern (scientific article) (in الألمانية). Berne: Department Communication, University of Berne. 152 (Sonderfall Hauptstatdtregion): 16–19. doi:10.7892/boris.41280. S2CID 178237847.

Als 1848 ein politisch-administratives Zentrum für den neuen Bundesstaat zu bestimmen war, verzichteten die Verfassungsväter darauf, eine Hauptstadt der Schweiz zu bezeichnen und formulierten stattdessen in Artikel 108: "Alles, was sich auf den Sitz der Bundesbehörden bezieht, ist Gegenstand der Bundesgesetzgebung." Die Bundesstadt ist also nicht mehr und nicht weniger als der Sitz der Bundesbehörden.

[In 1848, when a political and administrative centre was being determined for the new federation, the founders of the constitution abstained from designating a capital city for Switzerland and instead formulated in Article 108: "Everything, which relates to seat of the authorities, is the subject of the federal legislation." The federal city is therefore no more and no less than the seat of the federal authorities.] - ^ "Languages".

- ^ "DSTAT-TAB – interactive tables (FSO): Demographic balance by citizenship" (official statistics) (in الإنجليزية, الألمانية, الفرنسية, and الإيطالية). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Federal Statistical Office, FSO. 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Religion" (official statistics: population age 15+, observation period 2018–2020). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 21 March 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (December 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns". French Politics. 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. S2CID 73642272.

- ^ Elgie, Robert (2016). "Government Systems, Party Politics, and Institutional Engineering in the Round". Insight Turkey. 18 (4): 79–92. ISSN 1302-177X. JSTOR 26300453.

- ^ Kley, Andreas: Federal constitution in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland. Version of 3 May 2011.

- ^ "Surface water and surface water change". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Popolazione della Confederazione Svizzera". DataCommons.org. 25 August 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ Jacqueline Kucera, ed (22 November 2016) (PDF). Switzerland's population 2015. Swiss Statistics. Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO), Swiss Confederation. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population.assetdetail.1401565.html. Retrieved on 7 December 2016. - ^ أ ب ت ث "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2022". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 11 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF) (in الإنجليزية). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Berner, Elizabeth Kay; Berner, Robert A. (22 April 2012). Global Environment: Water, Air, and Geochemical Cycles – Second Edition (in الإنجليزية). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4276-6. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Thomas Fleiner; Alexander Misic; Nicole Töpperwien (5 August 2005). Swiss Constitutional Law. Kluwer Law International. p. 28. ISBN 978-90-411-2404-3.

- ^ Prof. Dr. Adrian Vatter (2014). Das politische System der Schweiz [The Political System of Switzerland]. Studienkurs Politikwissenschaft (in الألمانية). Baden-Baden: UTB Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8252-4011-0. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ Zimmer, Oliver (12 January 2004) [originally published: October 1998]. "In Search of Natural Identity: Alpine Landscape and the Reconstruction of the Swiss Nation". Comparative Studies in Society and History. London. 40 (4): 637–665. doi:10.1017/S0010417598001686. S2CID 146259022.

- ^ Josef Lang (14 December 2015). "Die Alpen als Ideologie". Tages-Anzeiger (in الألمانية). Zürich, Switzerland. Archived from the original on 15 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Schmock, Nico (30 January 2019). Die Schweiz als "Willensnation"? Die Kernelemente des Schweizer Selbstverständnisses (in الألمانية). ISBN 978-3-668-87199-1.

- ^ "Global wealth databook 2019" (PDF). Credit Suisse. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2020.Archived . The country data comes from Table 3.1 on page 117. The region data comes from the end of that table on page 120.

- ^ Subir Ghosh (9 October 2010). "US is still by far the richest country, China fastest growing". Digital Journal. Canada. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Simon Bowers (19 October 2011). "Franc's rise puts Swiss top of rich list". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Bachmann, Helena (23 March 2018). "Looking for a better quality of life? Try these three Swiss cities". USA Today. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Chloe (20 May 2019). "These cities offer the best quality of life in the world, according to Deutsche Bank". CNBC. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Paris and Zurich become world's most expensive cities to live in because of COVID-19". Euronews. 18 November 2020. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ "swiss | Etymology, origin and meaning of swiss by etymonline". www.etymonline.com (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Room, Adrian (2003). Placenames of the world : origins and meanings of the names for over 5000 natural features, countries, capitals, territories, cities, and historic sites. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1814-1. OCLC 54385937.

- ^ "Switzerland". Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "On Schwyzers, Swiss and Helvetians". admin.ch. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010.

- ^ "Züritütsch, Schweizerdeutsch" (PDF). schweizerdeutsch.ch. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ^ "Kanton Schwyz: Kurzer historischer Überblick". sz.ch. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ^ "Confoederatio helvetica (CH)". hls-dhs-dss.ch (in الألمانية). Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2022., Historical Lexicon of Switzerland.

- ^ Helvetia in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د "History". swissworld.org. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 19 أبريل 2010 suggested (help) - ^ "Switzerland's Roman heritage comes to life". swissinfo.ch.

- ^ Trumm, Judith. "Vindonissa". Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (in الألمانية). Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Switzerland history Archived 1 مارس 2014 at the Wayback Machine Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved on 27 November 2009

- ^ أ ب ت ث History of Switzerland Archived 8 مايو 2014 at the Wayback Machine Nationsonline.org. Retrieved on 27 November 2009

- ^ Greanias, Thomas. Geschichte der Schweiz und der Schweizer, Schwabe & Co 1986/2004. ISBN 978-3-7965-2067-9

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز "A Brief Survey of Swiss History". admin.ch. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ^ "Der Basler Bundesbrief vom 9. Juni 1501" (PDF).

- ^ E.Hofer, Roland. "Schaffhausen (Kanton)". Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (in الألمانية). Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Swiss border ("Les principales rectifications postérieures à 1815 concernent la vallée des Dappes en 1862 (frontière Vaud-France, env. 7,5 km2), la valle di Lei en 1952 (Grisons-Italie, 0,45 km2), l'Ellhorn en 1955 (colline revendiquée par la Suisse pour des raisons militaires, Grisons-Liechtenstein) et l'enclave allemande du Verenahof dans le canton de Schaffhouse en 1967.") in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.. It should be noticed that in valle di Lei, Italy got in exchange a territory of the same area. See here Archived 21 مايو 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Noblesse en Suisse". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ "The WIR, the supplementary Swiss currency since 1934". The Economy Journal (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Histoire de la Suisse, Éditions Fragnière, Fribourg, Switzerland

- ^ Lenin and the Swiss non-revolution Archived 11 مايو 2011 at the Wayback Machine swissinfo.ch. Retrieved on 25 January 2010

- ^ Urner, Klaus (2001) Let's Swallow Switzerland, Lexington Books, pp. 4, 7, ISBN 978-0-7391-0255-8

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "A Brief Survey of Swiss History". admin.ch. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ^ أ ب ت History of Switzerland Archived 8 مايو 2014 at the Wayback Machine Nationsonline.org. Retrieved on 27 November 2009

- ^ أ ب ت Book review: Target Switzerland: Swiss Armed Neutrality in World War II, Halbrook, Stephen P. Archived 1 ديسمبر 2009 at the Wayback Machine stonebooks.com. Retrieved on 2 December 2009

- ^ أ ب Asylum in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Switzerland, National Socialism and the Second World War Archived 30 مايو 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Final Report of the Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland, Pendo Verlag GmbH, Zürich 2002, ISBN 978-3-85842-603-1, p. 521.

- ^ Helmreich JE. "Diplomacy of Apology". Archived from the original on 5 May 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ (2002) "Final Report of the Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland – Second World War".: 107, Zürich: Pendo Verlag GmbH.

- ^ Bergier, Jean-Francois (2002). "Final Report of the Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland – Second World War".: 114, Zürich: Pendo Verlag GmbH.

- ^ Switzerland, National Socialism and the Second World War Archived 30 مايو 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Final Report of the Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland, Pendo Verlag GmbH, Zürich 2002, ISBN 978-3-85842-603-1

- ^ "States Formerly Possessing or Pursuing Nuclear Weapons". Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Fischer, Patrick (8 April 2019). "Als die Schweiz eine Atombombe wollte". Swiss National Museum (in الألمانية). Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Vuilleumier, Marie (15 October 2018). "Paul Scherrer Institut seit 30 Jahren im Dienst der Wissenschaft". Swissinfo (in الألمانية). Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Westberg, Gunnar (9 October 2010). "Swiss Nuclear Bomb". International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Country profile: Switzerland. UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office (29 October 2012).

- ^ "Parlamentsgeschichte". www.parlament.ch. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Henley, Jon (25 September 2020). "Swiss to vote on whether to end free movement deal with EU". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Chazan, David (27 September 2020). "Large majority of Swiss reject bid to rein in immigration from EU, says exit poll". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Abstimmungen – Indikatoren, Abstimmung vom 9. Februar 2014: Initiative "Gegen Masseneinwanderung"" (in الألمانية and الفرنسية). Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Neuchâtel 2014. 9 February 2014. Archived from the original (web page) on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ EU and Switzerland agree on free movement Archived 28 ديسمبر 2016 at the Wayback Machine EUobserver, 22 December 2016.

- ^ Switzerland referendum: Voters reject end to free movement with EU Archived 28 سبتمبر 2020 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News (Europe). Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "swiss | Etymology, origin and meaning of swiss by etymonline". www.etymonline.com (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Room, Adrian (2003). Placenames of the world : origins and meanings of the names for over 5000 natural features, countries, capitals, territories, cities, and historic sites. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1814-1. OCLC 54385937.

- ^ "Switzerland". Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "On Schwyzers, Swiss and Helvetians". admin.ch. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010.

- ^ "Züritütsch, Schweizerdeutsch" (PDF). schweizerdeutsch.ch. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ^ "Kanton Schwyz: Kurzer historischer Überblick". sz.ch. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ^ "Confoederatio helvetica (CH)". hls-dhs-dss.ch (in الألمانية). Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2022., Historical Lexicon of Switzerland.

- ^ Helvetia in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Swiss Federal Statistical Office. "Languages and religions - Data, indicators". Retrieved 9 October 2007. The first number refers to the share of languages within total population. The second refers to the Swiss citizens only.

- الأقليات المسلمة في أوروبا – سيد عبد المجيد بكر

- [1]

- [2]

- Clive H. Church (2004) The Politics and Government of Switzerland. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-69277-2.

- Dieter Fahrni (2003) An Outline History of Switzerland. From the Origins to the Present Day. 8th enlarged edition. Pro Helvetia, Zürich. ISBN 3-908102-61-8

- Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (2002-). Published electronically and in print simultaneously in three national languages of Switzerland.

- Dalton, O.M. (1927) The History of the Franks, by Gregory of Tours. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

وصلات خارجية

- مواقع رسمية

- The Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation

- Presence Switzerland

- Swiss Statistics, official website of the Swiss Federal Statistical Office.

- مصادر

- جغرافيا

- تاريخ

- Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (بالألمانية) (بالفرنسية) (Italian)

- history-switzerland.geschichte-schweiz.ch

- إعلام

- Neue Zürcher Zeitung (بالألمانية), a Swiss daily newspaper

- Le Temps (بالفرنسية), a Swiss daily newspaper

- Corriere Del Ticino (Italian), a Swiss daily newspaper

- swissinfo - News + Infos in 9 languages

- تعليم

- علوم, بحث وتكنولوجيا

- The Swiss Portal for Research and Innovation

- State Scretariat for Education and Research, SER

- The Swiss National Science Foundation

- CTI, Commission for Technology and Innovation

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- CS1 الإيطالية-language sources (it)

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- Articles containing إيطالية-language text

- Articles containing رومانش-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Lang and lang-xx code promoted to ISO 639-1

- Articles containing إنگليزية القديمة (ح. 450-1100)-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing Alemannic German-language text

- Articles containing Old High German (ca. 750-1050)-language text

- Articles containing نورسية القديمة-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2022

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة from September 2022

- Pages with empty portal template

- سويسرا

- بلدان أوروپا

- أعضاء الاتحاد الأوروبي

- بلدان اتحادية

- ديمقراطيات ليبرالية

- بلدان الألپ

- بلدان حبيسة

- دول تتحدث الفرنسية

- دول تتحدث الألمانية

- دول تتحدث الإيطالية

- أقاليم التصنيف الأول في الاتحاد الأوروپي