ميثان

| |||

|

| |||

| الأسماء | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| اسم أيوپاك المفضل

Methane[1] | |||

| اسم أيوپاك النظامي

Carbane (لا يوصى بها مطلقاً[1]) | |||

أسماء أخرى

| |||

| المُعرِّفات | |||

| رقم CAS | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 3DMet | |||

| مرجع بايلستاين | 1718732 | ||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.739 | ||

| رقم EC |

| ||

| مرجع Gmelin | 59 | ||

| KEGG | |||

| عناوين مواضيع طبية MeSH | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| رقم RTECS |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1971 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| الخصائص | |||

| الصيغة الجزيئية | CH4 | ||

| كتلة مولية | 16.04 g mol-1 | ||

| المظهر | غاز عديم اللون | ||

| الرائحة | عديم الرائحة | ||

| الكثافة | |||

| نقطة الانصهار | |||

| نقطة الغليان | |||

| قابلية الذوبان في الماء | 22.7 mg·L−1[4] | ||

| قابلية الذوبان | يذوب في الإيثانول، ثنائي إيثيل الإيثير، البنزين، التولوين، الميثانول، الأسيتون وغير قابل للذوبان في الماء | ||

| log P | 1.09 | ||

| kH | 14 nmol·Pa−1·كج−1 | ||

| القابلية المغناطيسية | −17.4×10−6 سم3·مول−1[5] | ||

| البنية | |||

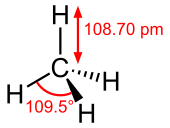

| الشكل الجزيئي | Tetrahedron | ||

| Dipole moment | 0 D | ||

| الكيمياء الحرارية | |||

| الإنتالپية المعيارية للتشكل ΔfH |

−74.6 kJ·mol−1 | ||

| الانتالبية المعيارية للاحتراق ΔcH |

−891 kJ·mol−1 | ||

| Standard molar entropy S |

186.3 J·(K·mol)−1 | ||

| سعة الحرارة النوعية، C | 35.7 J·(K·mol)−1 | ||

| المخاطر[6] | |||

| ن.م.ع. مخطط تصويري |

| ||

| ن.م.ع. كلمة الاشارة | خطر | ||

| H220 | |||

| P210 | |||

| NFPA 704 (معيـَّن النار) | |||

| نقطة الوميض | −188 °C (−306.4 °F; 85.1 K) | ||

| 537 °C (999 °F; 810 K) | |||

| حدود الانفجار | 4.4–17% | ||

| مركبات ذا علاقة | |||

alkanes ذات العلاقة

|

|||

ما لم يُذكر غير ذلك، البيانات المعطاة للمواد في حالاتهم العيارية (عند 25 °س [77 °ف]، 100 kPa). | |||

| مراجع الجدول | |||

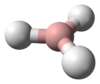

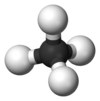

الميثان (إنگليزية: Methane، الأمريكي /ˈmɛθeɪn/، UK /ˈmiːθeɪn/)، هو مركب كيميائي صيغته الكيميائية CH4 (ذرة كربون واحدة مرتبطة بأربع ذرات هيدروجين). الميثان هو مجموعة-14 هيدريد ، أبسط ألكان، والمكون الرئيسي للغاز الطبيعي. الوفرة النسبية للميثان على الأرض تجعله وقود جذاب اقتصاديًا، على الرغم من أن التقاطه وتخزينه يمثل تحديات تقنية نظرًا لحالته الغازية تحت الشروط الطبيعية لدرجة الحرارة والضغط. الميثان النقي ليس له رائحة، ولكن عند إستخدامه تجارياً يتم خلطه بكميات ضئيلة من الكبريت القوي الرائحة. المركبات مثل إثيل مركبتان تمكن من تتبع أثار الميثان في حالة حدوث تسريب. حرق جزيء واحد من الميثان في وجود الأكسجين ينتج جزيء من ثاني أكسيد كربون، و2 جزيء من الماء.

- CH4 + 2O2 → CO2 + 2H2O

Naturally occurring methane is found both below ground and under the seafloor and is formed by both geological and biological processes. The largest reservoir of methane is under the seafloor in the form of methane clathrates. When methane reaches the surface and the atmosphere, it is known as atmospheric methane.[8]

The Earth's atmospheric methane concentration has increased by about 160% since 1750, with the overwhelming percentage caused by human activity.[9] It accounted for 20% of the total radiative forcing from all of the long-lived and globally mixed greenhouse gases, according to the 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report.[10] Strong, rapid and sustained reductions in methane emissions could limit near-term warming and improve air quality by reducing global surface ozone.[11]

Methane has also been detected on other planets, including Mars, which has implications for astrobiology research.[12]

الميثان أيضا أحد غازات الدفيئة وله عزم تدفئة عام يبلغ 21. ويبلغ المتر المكعب من الميثان 717 جرام.

الخصائص والارتباط

Methane is a tetrahedral molecule with four equivalent C–H bonds. Its electronic structure is described by four bonding molecular orbitals (MOs) resulting from the overlap of the valence orbitals on C and H. The lowest-energy MO is the result of the overlap of the 2s orbital on carbon with the in-phase combination of the 1s orbitals on the four hydrogen atoms. Above this energy level is a triply degenerate set of MOs that involve overlap of the 2p orbitals on carbon with various linear combinations of the 1s orbitals on hydrogen. The resulting "three-over-one" bonding scheme is consistent with photoelectron spectroscopic measurements.

Methane is an odorless gas and appears to be colorless.[13] It does absorb visible light, especially at the red end of the spectrum, due to overtone bands, but the effect is only noticeable if the light path is very long. This is what gives Uranus and Neptune their blue or bluish-green colors, as light passes through their atmospheres containing methane and is then scattered back out.[14]

The familiar smell of natural gas as used in homes is achieved by the addition of an odorant, usually blends containing tert-butylthiol, as a safety measure. Methane has a boiling point of −161.5 °C at a pressure of one atmosphere.[3] As a gas, it is flammable over a range of concentrations (5.4%–17%) in air at standard pressure.

Solid methane exists in several modifications. Presently nine are known.[15] Cooling methane at normal pressure results in the formation of methane I. This substance crystallizes in the cubic system (space group Fm3m). The positions of the hydrogen atoms are not fixed in methane I, i.e. methane molecules may rotate freely. Therefore, it is a plastic crystal.[16]

التفاعلات الكيميائية

التفاعلات الكيميائية الأولية للميثان هي الاحتراق، إعادة تشكل البخار إلى الغاز التخليقي، والهالوجين. بشكل عام، من الصعب السيطرة على تفاعلات الميثان.

الأكسدة الانتقائية

Partial oxidation of methane to methanol (CH3OH), a more convenient, liquid fuel, is challenging because the reaction typically progresses all the way to carbon dioxide and water even with an insufficient supply of oxygen. The enzyme methane monooxygenase produces methanol from methane, but cannot be used for industrial-scale reactions.[17] Some homogeneously catalyzed systems and heterogeneous systems have been developed, but all have significant drawbacks. These generally operate by generating protected products which are shielded from overoxidation. Examples include the Catalytica system, copper zeolites, and iron zeolites stabilizing the alpha-oxygen active site.[18]

One group of bacteria catalyze methane oxidation with nitrite as the oxidant in the absence of oxygen, giving rise to the so-called anaerobic oxidation of methane.[19]

التفاعلات الحمضية-القاعدية

Like other hydrocarbons, methane is an extremely weak acid. Its pKa in DMSO is estimated to be 56.[20] It cannot be deprotonated in solution, but the conjugate base is known in forms such as methyllithium.

A variety of positive ions derived from methane have been observed, mostly as unstable species in low-pressure gas mixtures. These include methenium or methyl cation CH+

3, methane cation CH+

4, and methanium or protonated methane CH+

5. Some of these have been detected in outer space. Methanium can also be produced as diluted solutions from methane with superacids. Cations with higher charge, such as CH2+

6 and CH3+

7, have been studied theoretically and conjectured to be stable.[21]

Despite the strength of its C–H bonds, there is intense interest in catalysts that facilitate C–H bond activation in methane (and other lower numbered alkanes).[22]

الاحتراق

Methane's heat of combustion is 55.5 MJ/kg.[23] Combustion of methane is a multiple step reaction summarized as follows:

Peters four-step chemistry is a systematically reduced four-step chemistry that explains the burning of methane.

تفاعلات الميثان الجذرية

Given appropriate conditions, methane reacts with halogen radicals as follows:

- •X + CH

4 → HX + •CH

3 - •CH

3 + X

2 → CH

3X + •X

where X is a halogen: fluorine (F), chlorine (Cl), bromine (Br), or iodine (I). This mechanism for this process is called free radical halogenation. It is initiated when UV light or some other radical initiator (like peroxides) produces a halogen atom. A two-step chain reaction ensues in which the halogen atom abstracts a hydrogen atom from a methane molecule, resulting in the formation of a hydrogen halide molecule and a methyl radical (•CH

3). The methyl radical then reacts with a molecule of the halogen to form a molecule of the halomethane, with a new halogen atom as byproduct.[24] Similar reactions can occur on the halogenated product, leading to replacement of additional hydrogen atoms by halogen atoms with dihalomethane, trihalomethane, and ultimately, tetrahalomethane structures, depending upon reaction conditions and the halogen-to-methane ratio.

This reaction is commonly used with chlorine to produce dichloromethane and chloroform via chloromethane. Carbon tetrachloride can be made with excess chlorine.

استخدامات الميثان

يستخدم الميثان في العمليات الكيميائية الصناعية ويمكن نقله كسائل مبرد (غاز طبيعي مسال). في حين تكون التسريبات من حاوية السوائل المبردة أثقل في البداية من الهواء بسبب زيادة كثافة الغاز البارد، فإن الغاز في درجة الحرارة المحيطة يكون أخف من الهواء. خطوط أنابيب الغاز توزع كميات كبيرة من الغاز الطبيعي، والذي يعتبر الميثان المكون الرئيسي له.

وقود

يستخدم الميثان كوقود لأفران، المنازل، سخانات المياه، ،[25][26] التوربينات، وغيرها. يُستخدم الكربون المنشـَط لتخزين الميثان. يستخدم الميثان كوقود للصواريخ، [27] عند استخدامه مع الأكسجين السائل، كما في محركات BE-4 وراپتور.[28]

كمكون رئيسي للغاز الطبيعي، فإن الميثان مهم لتوليد الكهرباء عن طريق حرقه كوقود في التوربينات الغازية أو مولدات البخار. بالمقارنة مع الوقود الهيدروكربوني، ينتج الميثان أقل ثاني أكسيد الكربون لكل وحدة حرارة مولدة. عند حوالي 891 كيلوجول/مول، تكون حرارة اختراق الميثان أقل من أي هيدروكربون آخر. ومع ذلك، فإنه ينتج حرارة لكل كتلة (55.7 كيلو جول/جم) أكثر من أي جزيء عضوي آخر بسبب محتواه الكبير نسبيًا من الهيدروجين ، والذي يمثل 55٪ من حرارة الاحتراق.[29] ولكنه يسهم بنسبة 25٪ فقط من الكتلة الجزيئية للميثان. في العديد من المدن، يضخ الميثان في أنابيب للمنازل من أجل التدفئة والطهي. في هذا السياق، يُعرف عادةً باسم الغاز الطبيعي، والذي يُعتبر أنه يحتوي على محتوى طاقة يبلغ 39 ميگا جول لكل متر مكعب، أو 1000 وحدة حرارية بريطانية لكل قدم مكعب قياسي. الغاز الطبيعي المسال (LNG) عبارة عن ميثان في الغالب يتم تحويله إلى شكل سائل لسهولة التخزين أو النقل.

كوقود صاروخي سائل ، يتمتع الميثان يميزة على الكيروسين لإنتاج جزيئات عادم صغيرة. هذه الرواسب تشكل كية سناج (هباب) أقل على الأجزاء الداخلية لمحركات الصواريخ، مما يقلل من صعوبة إعادة استخدام المعزز. يؤدي انخفاض الوزن الجزيئي للعادم أيضًا إلى زيادة جزء الطاقة الحرارية التي تكون على شكل طاقة حركية متاحة للدفع، مما يزيد من النبضة النوعية للصاروخ. للميثان السائل أيضًا نطاق درجة حرارة (91–112 ك) متوافق تقريبًا مع الأكسجين السائل (54-90 ك).

اللقيم الكيميائي

الغاز الطبيعي، الذي يتكون معظمه من الميثان، يستخدم لإنتاج غاز الهيدروجين على نطاق صناعي. إعادة تشكيل غاز الميثان بالبخار (SMR)، أو المعروف ببساطة باسم إعادة التشكيل بالبخار، هو الطريقة الصناعية القياسية لإنتاج غاز الهيدروجين التجاري. يُنتج أكثر من 50 مليون طن متري سنويًا في جميع أنحاء العالم (2013)، بشكل أساسي من اعادة تشكيل الغاز الطبيعي بالبخار.[30] يستخدم الكثير من هذا الهيدروجين في مصافي النفط، في إنتاج المواد الكيميائية وفي معالجة الأغذية. تستخدم كميات كبيرة جدًا من الهيدروجين في التخليق الصناعي للأمونيا.

في درجات حرارة عالية (700-1100 درجة مئوية) وفي وجود فلز محفز (نيكل)، يتفاعل البخار مع الميثان لينتج خليطًا من أول أكسيد الكربون وثنائي الهيدروجين، المعروفين باسم "الغاز الاصطناعي" أو "syngas":

هذا التفاعل ماص قوي للحرارة (الحرارة المستهلكة، ΔHr = 206 kJ/mol). يتم الحصول على هيدروجين إضافي عن طريق تفاعل أول أكسيد الكربون مع الماء عبر تفاعل تفاعل إنزياح الماء-الغاز:

- CO + H2O ⇌ CO2 + H2

رد الفعل هذا طارد معتدل للحرارة (الحرارة المنتجة، ΔHr = −41 kJ/mol).

يخضع الميثان أيضًا إلى الكلورة حرة الجذور في إنتاج الكلوروميثان، على الرغم من أن الميثانول هو أكثر شيوعًا.[31]

التوليد

Methane can be generated through geological, biological or industrial routes.

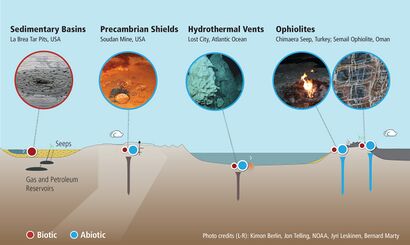

الطرق الجيولوجية

المساران الرئيسيان لتوليد الميثان الجيولوجي هما (1) المسار العضوي (المخلق حرارياً) و(2) المسار غير العضوي (غير حيوي).[32]

يتواجد الميثان المخلق حرارياً نتيجة لتفكك المادة العضوية عند درجات حرارة مرتفعة وضغوط في أعماق الرواسب طبقات الأرض. معظم الميثان في الأحواض الرسوبية هو ميثان مخلق حرارياً. لذلك، فإن الميثان الملخق حرارياً هو أهم مصدر للغاز الطبيعي. تعتبر مكونات الميثان المخلقة حرارياً عادةً من بقايا طبقات الأرض. بشكل عام، يمكن أن يتواجد الميثان المخلق حرارياً (في العمق) من خلال تكسير المواد العضوية أو التخليق العضوي. كلتا الطريقتين يمكن أن تشمل الكائنات الحية الدقيقة (تخليق الميثان) ، ولكن قد تحدث أيضًا بشكل غير عضوي. يمكن أن تستهلك العمليات المعنية أيضًا الميثان، مع الكائنات الحية الدقيقة وبدونها.

المصدر الأكثر أهمية للميثان في الأعماق (الأساس البلوري) هو غير حيوي. يعني اللاأحيائي أن الميثان يتكون من مركبات غير عضوية، بدون نشاط حيوي، إما من خلال العمليات الصهارية أو من خلال تفاعلات الصخور المائية التي تحدث عند درجات حرارة وضغوط منخفضة، مثل السرپنتينة.[33][34]

الطرق الحيوية

معظم الميثان الموجود على الأرض هو ميثان حيوي وينتج عن طريق تخليق الميثان،[35][36] أحد أشكال التنفس اللاهوائي ومعروف فقط أنه يحدث بواسطة بعض أنواع شعبة العتائق.[37] تتواجد الميثانوجينات في مكبات النفايات وغيرها من أنواع التربة،[38] المجترات (مثل البقر),[39] أحشاء النمل الأبيض والرواسب قليلة الأكسجين تحت قاع البحر وقاع البحيرات. تنتج حقول الأرز أيضًا كميات كبيرة من الميثان أثناء نمو النبات.[40] This multistep process is used by these microorganisms for energy. The net reaction of methanogenesis is:

- CO2 + 4 H2→ CH4 + 2 H2O

يتم تحفيز الخطوة الأخيرة في العملية بواسطة اختزال إنزيم الميثيل المساعد (MCR).[41]

المجترات

المجترات، مثل الماشية، تتجشأ الميثان، وهي مسؤولة عن حوالي 22٪ من انبعاثات الميثان السنوية إلى الغلاف الجوي في الولايات المتحدة.[42] ذكرت إحدى الدراسات أن قطاع الثروة الحيوانية بشكل عام (الماشية والدجاج والخنازير بشكل أساسي) ينتج 37٪ من إجمالي غاز الميثان الناجم عن النشاط البشري.[43] قدرت دراسة أجريت عام 2013 أن الثروة الحيوانية تمثل 44٪ من غاز الميثان الذي ينتج بسبب النشاط البشري وحوالي 15٪ من انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة الناجمة عن النشاط البشري.[44] تُبذل الكثير من الجهود لتقليل إنتاج الميثان من الماشية، مثل العلاجات الطبية والتعديلات الغذائية،[45][46] وحبس الغاز لاستخدام طاقة الاحتراق.[47]

رواسب قاع البحر

تحتوي معظم قيعان البحار على مياه قليلة الأكسجين حيث يزال الأكسجين بواسطة الكائنات الحية الدقيقة الهوائية داخل السنتيمترات القليلة الأولى من الرواسب. تحت قاع البحر المليء بالأكسجين، تنتج الميثانوجينات الميثان الذي تستخدمه كائنات أخرى أو يصبح محاصرًا في هيدرات الغاز.[37] تُعرف هذه الكائنات الحية الأخرى التي تستخدم الميثان للحصول على الطاقة باسم الميثانوتروفات ("مستهكلات الميثان")، وهي السبب الرئيسي وراء وصول القليل من الميثان المتولد في الأعماق إلى سطح البحر.[37] عُثر على مجموعات متحدة من العتائق والجراثيم تعمل على أكسدة الميثان عبر الأكسدة اللاهوائية للميثان (AOM)؛ العضيات المسؤولة عن ذلك هي الميثانوتروفات اللاهوئية (ANME) والجراثيم المختزلة الكبريتات (SRB).[48]

الطرق الصناعية

بالنظر إلى وفرة الغاز الطبيعي الرخيصة، لا يوجد حافز كبير لإنتاج الميثان صناعياً. يمكن إنتاج الميثان عن طريق هدرجة ثاني أكسيد الكربون من خلال عملية ساباتييه. الميثان هو أيضًا منتج جانبي لهدرجة أول أكسيد الكربون في عملية فيشر-تروپش ، والتي تُجرى على نطاق واسع لإنتاج جزيئات أطول سلسلة من الميثان.

ومن أمثلة تغويز الفحم إلى غاز الميثان على نطاق واسع هو مصنع گريت پلينز للوقود الاصطناعي، الذي بدأ في عام 1984 في بيلوا، داكوتا الشمالية كطريقة لتطوير موارد محلية وفيرة من الفحم البني منخفض الدرجة، مورد يصعب نقله بخلاف ذلك بسبب وزنه، ومحتوى الرماد وقيمته الحرارية المنخفضة والميل إلى الاحتراق التلقائي أثناء التخزين والنقل. يوجد عدد من المصانع المماثلة في جميع أنحاء العالم، على الرغم من أن معظم هذه المصانع تستهدف إنتاج الألكانات طويلة السلسلة لاستخدامها مثل البنزين، الديزل، أو كمادة وسيطة لعمليات أخرى.

تستخدم تقنية الطاقة إلى ميثان الطاقة الكهربائية لإنتاج الهيدروجين من الماء عن طريق التحليل الكهربائي وتستخدم تفاعل ساباتييه للجمع الهيدروجين مع ثاني أكسيد الكربون لإنتاج الميثان. اعتبارًا من عام2021 ، كانت هذه التقنية قيد التطوير ولا تستخدم على نطاق واسع. من الناحية النظري ، يمكن استخدام العملية كمخزن مؤقت للطاقة الزائدة وخارج الذروة الناتجة عن توربينات الرياح الألواح الشمسية شديدة التقلب. ومع ذلك، نظرًا لاستخدام كميات كبيرة جدًا من الغاز الطبيعي حاليًا في محطات توليد الطاقة (على سبيل المثال الدورات المجموعة) لإنتاج الطاقة الكهربائية، فإن الخسائر في الكفاءة غير مقبولة.

التخليق المعملي

يمكن إنتاج الميثان بواسطة إضافة پروتون ميثيل الليثيوم أو ميثيل كاشف گرينيار مثل ميثيل كلوريد المغنيسيوم. ويمكن أيضًا تصنيعه من أسيتات الصوديوم اللامائية وهيدروكسيد الصوديوم الجاف، وخلطه وتسخينه فوق 300 درجة مئوية (مع كربونات الصوديوم كمنتج ثانوي).[بحاجة لمصدر] من الناحية العملية، يمكن بسهولة تلبية متطلبات الميثان النقي بواسطة زجاجة غاز فولاذية من موردي الغاز القياسيين.

التواجد

Methane was discovered and isolated by Alessandro Volta between 1776 and 1778 when studying marsh gas from Lake Maggiore. It is the major component of natural gas, about 87% by volume. The major source of methane is extraction from geological deposits known as natural gas fields, with coal seam gas extraction becoming a major source (see coal bed methane extraction, a method for extracting methane from a coal deposit, while enhanced coal bed methane recovery is a method of recovering methane from non-mineable coal seams). It is associated with other hydrocarbon fuels, and sometimes accompanied by helium and nitrogen. Methane is produced at shallow levels (low pressure) by anaerobic decay of organic matter and reworked methane from deep under the Earth's surface. In general, the sediments that generate natural gas are buried deeper and at higher temperatures than those that contain oil.

Methane is generally transported in bulk by pipeline in its natural gas form, or by LNG carriers in its liquefied form; few countries transport it by truck.

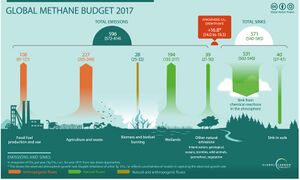

ميثان الغلاف الجوي والتغير المناخي

Global monitoring of atmospheric methane concentrations began in the 1980s.[9] The Earth's atmospheric methane concentration has increased 160% since preindustrial levels in the mid-18th century, according to the 2022 United Nations Environment Programme's (UNEP) "Global Methane Assessment".[9] The largest annual increase occurred in 2021 with the overwhelming percentage caused by human activity.[9] Atmospheric methane accounted for 20% of the total radiative forcing from all of the long-lived and globally mixed greenhouse gases. The AR6 of the IPCC states: "Observed increases in well-mixed greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations since around 1750 are unequivocally caused by human activities. Since 2011 (measurements reported in AR5), concentrations have continued to increase in the atmosphere, reaching annual averages of 410 ppm for carbon dioxide (CO

2), 1866 ppb for methane (CH

4), and 332 ppb for nitrous oxide (N

2O) in 2019. (…) In 2019, atmospheric CO

2 concentrations were higher than at any time in at least 2 million years (high confidence), and concentrations of CH

4 and N

2O were higher than at any time in at least 800,000 years (very high confidence). Since 1750, increases in CO

2 (47%) and CH

4 (156%) concentrations far exceed, and increases in N

2O (23%) are similar to, the natural multi-millennial changes between glacial and interglacial periods over at least the past 800,000 years (very high confidence)".[10][أ][49] The largest annual increase occurred in 2021 with current concentrations reaching a record 260% of pre-industrial—with the overwhelming percentage caused by human activity.[9][ب]

Historic methane concentrations in the world's atmosphere have ranged between 300 and 400 nmol/mol during glacial periods commonly known as ice ages, and between 600 and 700 nmol/mol during the warm interglacial periods. A 2012 NASA website said the oceans were a potential important source of Arctic methane,[50] but more recent studies associate increasing methane levels as caused by human activity.[9]

Methane is an important greenhouse gas with a global warming potential (GWP) of 29.8 ± 11 compared to CO

2 (potential of 1) over a 100-year period, and 82.5 ± 25.8 over a 20-year period.[51] As methane is gradually converted into carbon dioxide (and water) in the atmosphere, these values include the climate forcing from the carbon dioxide produced from methane over these timescales.

From 2015 to 2019 sharp rises in levels of atmospheric methane have been recorded.[52][53] In February 2020, it was reported that fugitive emissions and gas venting from the fossil fuel industry may have been significantly underestimated.[54] [55]

Climate change can increase atmospheric methane levels by increasing methane production in natural ecosystems, forming a climate change feedback.[56][57] Another explanation for the rise in methane emissions could be a slowdown of the chemical reaction that removes methane from the atmosphere.[58]

Over 100 countries have signed the Global Methane Peldge, launched in 2021, promising to cut their methane emissions by 30% by 2030.[59] This could avoid 0.2˚C of warming globally by 2050, although there have been calls for higher commitments in order to reach this target.[60] The International Energy Agency's 2022 report states "the most cost-effective opportunities for methane abatement are in the energy sector, especially in oil and gas operations".[61]

كلاثرات

Methane clathrates (also known as methane hydrates) are solid cages of water molecules that trap single molecules of methane. Significant reservoirs of methane clathrates have been found in arctic permafrost and along continental margins beneath the ocean floor within the gas clathrate stability zone, located at high pressures (1 to 100 MPa; lower end requires lower temperature) and low temperatures (< 15 °C; upper end requires higher pressure).[62] Methane clathrates can form from biogenic methane, thermogenic methane, or a mix of the two. These deposits are both a potential source of methane fuel as well as a potential contributor to global warming.[63][64] The global mass of carbon stored in gas clathrates is still uncertain and has been estimated as high as 12,500 Gt carbon and as low as 500 Gt carbon.[65] The estimate has declined over time with a most recent estimate of ~1800 Gt carbon.[66] A large part of this uncertainty is due to our knowledge gap in sources and sinks of methane and the distribution of methane clathrates at the global scale. For example, a source of methane was discovered relatively recently in an ultraslow spreading ridge in the Arctic.[67] Some climate models suggest that today's methane emission regime from the ocean floor is potentially similar to that during the period of the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) around 55.5 million years ago, although there are no data indicating that methane from clathrate dissociation currently reaches the atmosphere.[66] Arctic methane release from permafrost and seafloor methane clathrates is a potential consequence and further cause of global warming; this is known as the clathrate gun hypothesis.[68][69][70][71] Data from 2016 indicate that Arctic permafrost thaws faster than predicted.[72]

السلامة العامة والبيئة

Methane "degrades air quality and adversely impacts human health, agricultural yields, and ecosystem productivity".[73]

Methane is extremely flammable and may form explosive mixtures with air. Methane gas explosions are responsible for many deadly mining disasters.[74] A methane gas explosion was the cause of the Upper Big Branch coal mine disaster in West Virginia on April 5, 2010, killing 29.[75] Natural gas accidental release has also been a major focus in the field of safety engineering, due to past accidental releases that concluded in the formation of jet fire disasters.[76][77]

The 2015–2016 methane gas leak in Aliso Canyon, California was considered to be the worst in terms of its environmental effect in American history.[78][79][80] It was also described as more damaging to the environment than Deepwater Horizon's leak in the Gulf of Mexico.[81]

In May 2023 The Guardian published a report, blaming Turkmenistan to be the worst in the world for methane super emitting. The data collected by Kayrros researchers indicate, that two large Turkmen fossil fuel fields leaked 2.6m and 1.8m tonnes of methane in 2022 alone, pumping the CO2 equivalent of 366m tonnes into the atmosphere, surpassing the annual CO2 emissions of the United Kingdom.[82]

Methane is also an asphyxiant if the oxygen concentration is reduced to below about 16% by displacement, as most people can tolerate a reduction from 21% to 16% without ill effects. The concentration of methane at which asphyxiation risk becomes significant is much higher than the 5–15% concentration in a flammable or explosive mixture. Methane off-gas can penetrate the interiors of buildings near landfills and expose occupants to significant levels of methane. Some buildings have specially engineered recovery systems below their basements to actively capture this gas and vent it away from the building.

الميثان خارج الأرض

الوسط بين النجوم

Methane is abundant in many parts of the Solar System and potentially could be harvested on the surface of another Solar System body (in particular, using methane production from local materials found on Mars[83] or Titan), providing fuel for a return journey.[27][84]

المريخ

Methane has been detected on all planets of the Solar System and most of the larger moons.[بحاجة لمصدر] With the possible exception of Mars, it is believed to have come from abiotic processes.[85][86]

The Curiosity rover has documented seasonal fluctuations of atmospheric methane levels on Mars. These fluctuations peaked at the end of the Martian summer at 0.6 parts per billion.[87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94]

Methane has been proposed as a possible rocket propellant on future Mars missions due in part to the possibility of synthesizing it on the planet by in situ resource utilization.[95] An adaptation of the Sabatier methanation reaction may be used with a mixed catalyst bed and a reverse water-gas shift in a single reactor to produce methane from the raw materials available on Mars, utilizing water from the Martian subsoil and carbon dioxide in the Martian atmosphere.[83]

Methane could be produced by a non-biological process called serpentinization[ت] involving water, carbon dioxide, and the mineral olivine, which is known to be common on Mars.[96]

يعتقد ان الميثان تم تحديد وجوده في أماكن عديدة في النظام الشمسي. ويعتقد أنه تكون خلال العمليات الغير عضوية التى كانت تصاحب تطور النظام الشمسي، كما أن هناك إعتقاد أنه تكون في وجود حياة على المريخ.

- كوكب المشترى

- كوكب المريخ

- كوكب زحل

- كوكب نيبتون

- كوكب أورانوس

- المذنب هالي

- المذنب هياكوتاكي

كما توجد أثار لغاز الميثان في طبقة رقيقة على القمر التابع للأرض. كما أن هناك بعض الإكتشافات حول وجود الميثان في السحابات الموجودة بين النجوم.

التاريخ

في نوفمبر 1776، تم التعرف على الميثان علميًا لأول مرة من قبل الفيزيائي الإيطالي ألساندرو ڤولتا في مستنقعات بحيرة ماجوري بين إيطاليا وسويسرا. ألهم ڤولتا البحث عن المادة قراءته لمقال كتبه بنجامين فرانكلين حول "الهواء القابل للاشتعال".[97] جمع ڤولتا الغاز المتصاعد من المستنقعات، وبحلول عام 1778 كان قد عزل غاز الميثان النقي.[98] كما أوضح أن الغاز يمكن أن يشتعل بواسطة شرارة كهربائية.[98] في أعقاب كارثة منجم فلينگ عام 1812 والتي لقي فيها 92 رجلاً حتفهم، أثبت السير همفري ديڤي أن غاز المناجم ما هو في الواقع إلى غاز الميثان .[99]

صيغ اسم "الميثان" عام 1866 بواسطة الكيميائي الألماني أوگست ڤلهلم فون هوفمان.[100][101] الاسم مشتق من الميثانول.

السلامة

الميثان غير سام، ومع ذلك فهو سريع الاشتعال ويمكن أن يشكل مخاليط متفجرة مع الهواء. الميثان هو أيضًا غاز خانق إذا انخفض تركيز الأكسجين إلى أقل من حوالي 16٪ عن طريق الإزاحة، كما يمكن لمعظم الناس تحمل الضغط من 21٪ إلى 16٪ بدون تأثيرات سلبية. تركيز الميثان الذي تصبح عنده مخاطر الاختناق كبيرة أعلى بكثير من تركيز 5-15٪ في خليط قابل للاشتعال أو متفجر. يمكن لغاز الميثان المنبعث أن يخترق الأجزاء الداخلية للمباني القريبة من مكبات النفايات ويعرض السكان لمستويات كبيرة من الميثان. بعض المباني لديها أنظمة استرجاع مصممة خصيصًا أسفل الطوابق السفلية من أجل التقاط هذا الغاز بشكل فعال وتنفيسه بعيدًا عن المبنى.

انفجارات غاز الميثان مسؤولة عن العديد من كوارث التعدين المميتة.[102]

كان انفجار غاز الميثان سببًا في كارثة منجم أپر بگ برانش للفحم في ڤرجينيا الغربية في 5 أبريل 2010، مما أسفر عن مقتل 29 شخص.[103]

انظر أيضاً

- الألكانات. أحد أنواع الهيدروكربونات والتى يكون الميثان أبسط أعضائها.

- كلاثرات ميثان، نوع من انواع الثلج يحتوى على الميثان.

- ميثانوجين، نوع من العتائق ينطلق منهما الميثان كمنتج ثانوي أثناء عمليات الأيض.

- تصنيع ميثان تكون الميثان بواسطة الميكروبات.

- ميثانوتروف، نوع من أنواع البكتريا التى تستخدم الميثان كمصدر وحيد للكربون والطاقة.

- مجموعة ميثيل، مجموعة فعالة تشبه الميثان.

مرئيات

| نحو 14.5% من انبعاثات الميثان المسببة للاحترار العالمي تتجشأه الأبقار، كجزء من عملية الهضم وتكوين اللحوم. لذلك قامت شركة كارجل، كبرى منتجي الحبوب والأعلاف بالعالم، بانتاج فلتر يوضع على أنوف الأبقار، فيحول الميثان إلى ثاني أكسيد كربون، الذي هو أخف وطأة على البيئة. |

المصادر

- ^ أ ب "Front Matter". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. pp. 3–4. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

Methane is a retained name (see P-12.3) that is preferred to the systematic name 'carbane', a name never recommended to replace methane, but used to derive the names 'carbene' and 'carbyne' for the radicals H2C2• and HC3•, respectively.

- ^ "Gas Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ أ ب Haynes, p. 3.344

- ^ Haynes, p. 5.156

- ^ Haynes, p. 3.578

- ^ "Safety Datasheet, Material Name: Methane" (PDF). USA: Metheson Tri-Gas Incorporated. December 4, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2011.

- ^ NOAA Office of Response and Restoration, US GOV. "METHANE". noaa.gov. Archived from the original on January 9, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Khalil, M. A. K. (1999). "Non-Co2 Greenhouse Gases in the Atmosphere". Annual Review of Energy and the Environment. 24: 645–661. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.24.1.645.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "Global Methane Assessment". United Nations Environment Programme and Climate and Clean Air Coalition (Nairobi): 12. 2022. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/41108/methane_2030_SPM.pdf. Retrieved on March 15, 2023. - ^ أ ب "Climate Change 2021. The Physical Science Basis. Summary for Policymakers. Working Group I contribution to the WGI Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". IPCC. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ IPCC, 2023: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. A Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, page 26, section C.2.3

- ^ Etiope, Giuseppe; Lollar, Barbara Sherwood (2013). "Abiotic Methane on Earth". Reviews of Geophysics. 51 (2): 276–299. Bibcode:2013RvGeo..51..276E. doi:10.1002/rog.20011. S2CID 56457317.

- ^ Hensher, David A.; Button, Kenneth J. (2003). Handbook of transport and the environment. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-08-044103-0. Archived from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ P.G.J Irwin; et al. (Jan 12, 2022). "Hazy Blue Worlds: A Holistic Aerosol Model for Uranus and Neptune, Including Dark Spots". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 127 (6): e2022JE007189. arXiv:2201.04516. Bibcode:2022JGRE..12707189I. doi:10.1029/2022JE007189. PMC 9286428. PMID 35865671. S2CID 245877540.

- ^ Bini, R.; Pratesi, G. (1997). "High-pressure infrared study of solid methane: Phase diagram up to 30 GPa". Physical Review B. 55 (22): 14800–14809. Bibcode:1997PhRvB..5514800B. doi:10.1103/physrevb.55.14800.

- ^ Wendelin Himmelheber. "Crystal structures". Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ Baik, Mu-Hyun; Newcomb, Martin; Friesner, Richard A.; Lippard, Stephen J. (2003). "Mechanistic Studies on the Hydroxylation of Methane by Methane Monooxygenase". Chemical Reviews. 103 (6): 2385–419. doi:10.1021/cr950244f. PMID 12797835.

- ^ Snyder, Benjamin E. R.; Bols, Max L.; Schoonheydt, Robert A.; Sels, Bert F.; Solomon, Edward I. (December 19, 2017). "Iron and Copper Active Sites in Zeolites and Their Correlation to Metalloenzymes". Chemical Reviews. 118 (5): 2718–2768. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00344. PMID 29256242.

- ^ Reimann, Joachim; Jetten, Mike S.M.; Keltjens, Jan T. (2015). "Chapter 7 Metal Enzymes in "Impossible" Microorganisms Catalyzing the Anaerobic Oxidation of Ammonium and Methane". In Peter M.H. Kroneck and Martha E. Sosa Torres (ed.). Sustaining Life on Planet Earth: Metalloenzymes Mastering Dioxygen and Other Chewy Gases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 15. Springer. pp. 257–313. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12415-5_7. ISBN 978-3-319-12414-8. PMID 25707470.

- ^ Bordwell, Frederick G. (1988). "Equilibrium acidities in dimethyl sulfoxide solution". Accounts of Chemical Research. 21 (12): 456–463. doi:10.1021/ar00156a004.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRasul - ^ Bernskoetter, W. H.; Schauer, C. K.; Goldberg, K. I.; Brookhart, M. (2009). "Characterization of a Rhodium(I) σ-Methane Complex in Solution". Science. 326 (5952): 553–556. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..553B. doi:10.1126/science.1177485. PMID 19900892. S2CID 5597392.

- ^ Energy Content of some Combustibles (in MJ/kg) Archived يناير 9, 2014 at the Wayback Machine. People.hofstra.edu. Retrieved on March 30, 2014.

- ^ March, Jerry (1968). Advance Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms and Structure. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 533–534.

- ^ "Lumber Company Locates Kilns at Landfill to Use Methane – Energy Manager Today". Energy Manager Today. September 23, 2015. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ Cornell, Clayton B. (April 29, 2008). "Natural Gas Cars: CNG Fuel Almost Free in Some Parts of the Country". Archived from the original on January 20, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

Compressed natural gas is touted as the 'cleanest burning' alternative fuel available, since the simplicity of the methane molecule reduces tailpipe emissions of different pollutants by 35 to 97%. Not quite as dramatic is the reduction in net greenhouse-gas emissions, which is about the same as corn-grain ethanol at about a 20% reduction over gasoline

- ^ أ ب Thunnissen, Daniel P.; Guernsey, C. S.; Baker, R. S.; Miyake, R. N. (2004). "Advanced Space Storable Propellants for Outer Planet Exploration". American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (4–0799): 28.

- ^ "Blue Origin BE-4 Engine". Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

We chose LNG because it is highly efficient, low cost and widely available. Unlike kerosene, LNG can be used to self-pressurize its tank. Known as autogenous repressurization, this eliminates the need for costly and complex systems that draw on Earth's scarce helium reserves. LNG also possesses clean combustion characteristics even at low throttle, simplifying engine reuse compared to kerosene fuels.

- ^ Schmidt-Rohr, Klaus (2015). "Why Combustions Are Always Exothermic, Yielding About 418 kJ per Mole of O2". Journal of Chemical Education. 92 (12): 2094–2099. Bibcode:2015JChEd..92.2094S. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00333.

- ^ Report of the Hydrogen Production Expert Panel: A Subcommittee of the Hydrogen & Fuel Cell Technical Advisory Committee Archived فبراير 14, 2020 at the Wayback Machine. United States Department of Energy (May 2013).

- ^ Rossberg, M. et al. (2006) "Chlorinated Hydrocarbons" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. DOI:10.1002/14356007.a06_233.pub2.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:15 - ^ Kietäväinen and Purkamo (2015). "The origin, source, and cycling of methane in deep crystalline rock biosphere". Front. Microbiol. 6: 725. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00725. PMC 4505394. PMID 26236303.

- ^ Cramer and Franke (2005). "Indications for an active petroleum system in the Laptev Sea, NE Siberia". Journal of Petroleum Geology. 28 (4): 369–384. Bibcode:2005JPetG..28..369C. doi:10.1111/j.1747-5457.2005.tb00088.x. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ Lessner, Daniel J. (Dec 2009) Methanogenesis Biochemistry. In: eLS. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester. http://www.els.net Archived مايو 13, 2011 at the Wayback Machine [doi: 10.1002/9780470015902.a0000573.pub2]

- ^ Thiel, Volker (2018), "Methane Carbon Cycling in the Past: Insights from Hydrocarbon and Lipid Biomarkers", in Wilkes, Heinz, Hydrocarbons, Oils and Lipids: Diversity, Origin, Chemistry and Fate, Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–30, doi:, ISBN 9783319545295

- ^ أ ب ت Dean, Joshua F.; Middelburg, Jack J.; Röckmann, Thomas; Aerts, Rien; Blauw, Luke G.; Egger, Matthias; Jetten, Mike S. M.; de Jong, Anniek E. E.; Meisel, Ove H. (2018). "Methane Feedbacks to the Global Climate System in a Warmer World". Reviews of Geophysics. 56 (1): 207–250. Bibcode:2018RvGeo..56..207D. doi:10.1002/2017RG000559. hdl:1874/366386.

- ^ Serrano-Silva, N.; Sarria-Guzman, Y.; Dendooven, L.; Luna-Guido, M. (2014). "Methanogenesis and methanotrophy in soil: a review". Pedosphere. 24 (3): 291–307. doi:10.1016/s1002-0160(14)60016-3.

- ^ Sirohi, S. K.; Pandey, Neha; Singh, B.; Puniya, A. K. (September 1, 2010). "Rumen methanogens: a review". Indian Journal of Microbiology. 50 (3): 253–262. doi:10.1007/s12088-010-0061-6. PMC 3450062. PMID 23100838.

- ^ IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The physical Science Basis Archived أكتوبر 3, 2018 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations Environment Programme, 2013: Ch. 6, p. 507 IPCC.ch

- ^ Lyu, Zhe; Shao, Nana; Akinyemi, Taiwo; Whitman, William B. (2018). "Methanogenesis". Current Biology. 28 (13): R727–R732. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.021. PMID 29990451.

- ^ "Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2014". 2016. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[صفحة مطلوبة] - ^ FAO (2006). Livestock's Long Shadow–Environmental Issues and Options. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ^ Gerber, P.J.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A. & Tempio, G. (2013). "Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock". Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Archived from the original on July 19, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ Roach, John (May 13, 2002). "New Zealand Tries to Cap Gaseous Sheep Burps". National Geographic. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ Roque, Breanna M.; Venegas, Marielena; Kinley, Robert D.; Nys, Rocky de; Duarte, Toni L.; Yang, Xiang; Kebreab, Ermias (March 17, 2021). "Red seaweed (Asparagopsis taxiformis) supplementation reduces enteric methane by over 80 percent in beef steers". PLOS ONE (in الإنجليزية). 16 (3): e0247820. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1647820R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247820. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7968649. PMID 33730064.

- ^ Silverman, Jacob (July 16, 2007). "Do cows pollute as much as cars?". HowStuffWorks.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ Knittel, K.; Wegener, G.; Boetius, A. (2019), McGenity, Terry J., ed., Anaerobic Methane Oxidizers, Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–21, doi:, ISBN 9783319600635

- ^ IPCC (2013). Stocker, T. F.; Qin, D.; Plattner, G.-K. et al.. eds. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/WG1AR5_SummaryVolume_FINAL.pdf. - ^ "Study Finds Surprising Arctic Methane Emission Source". NASA. April 22, 2012. Archived from the original on August 4, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Forster, P.; Storelvmo, T.; Armour, K.; Collins, W.; Dufresne, J.-L.; Frame, D.; Lunt, D.J.; Mauritsen, T.; Palmer, M.D.; Watanabe, M.; Wild, M.; Zhang, H. (2021). "The Earth's Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity". Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. pp. 923–1054.

- ^ Nisbet, E.G. (February 5, 2019). "Very Strong Atmospheric Methane Growth in the 4 Years 2014–2017: Implications for the Paris Agreement". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 33 (3): 318–342. Bibcode:2019GBioC..33..318N. doi:10.1029/2018GB006009.

- ^ McKie, Robin (February 2, 2017). "Sharp rise in methane levels threatens world climate targets". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on July 30, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Hmiel, Benjamin; Petrenko, V. V.; Dyonisius, M. N.; Buizert, C.; Smith, A. M.; Place, P. F.; Harth, C.; Beaudette, R.; Hua, Q.; Yang, B.; Vimont, I.; Michel, S. E.; Severinghaus, J. P.; Etheridge, D.; Bromley, T.; Schmitt, J.; Faïn, X.; Weiss, R. F.; Dlugokencky, E. (February 2020). "Preindustrial 14CH4 indicates greater anthropogenic fossil CH4 emissions". Nature. 578 (7795): 409–412. Bibcode:2020Natur.578..409H. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-1991-8. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 32076219. S2CID 211194542. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ Harvey, Chelsea (February 21, 2020). "Methane Emissions from Oil and Gas May Be Significantly Underestimated; Estimates of methane coming from natural sources have been too high, shifting the burden to human activities". E&E News via Scientific American. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDean-2018-2 - ^ Carrington, Damian (July 21, 2020) First active leak of sea-bed methane discovered in Antarctica Archived يوليو 22, 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian

- ^ Ravilious, Kate (2022-07-05). "Methane much more sensitive to global heating than previously thought – study". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ Global Methane Pledge. "Homepage | Global Methane Pledge". www.globalmethanepledge.org. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- ^ Forster, Piers; Smith, Chris; Rogelj, Joeri (2021-11-02). "Guest post: The Global Methane Pledge needs to go further to help limit warming to 1.5C". Carbon Brief (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- ^ IEA (2022). "Global Methane Tracker 2022". IEA (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- ^ Bohrmann, Gerhard; Torres, Marta E. (2006), Schulz, Horst D.; Zabel, Matthias, eds., Gas Hydrates in Marine Sediments, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 481–512, doi:, ISBN 9783540321446

- ^ Miller, G. Tyler (2007). Sustaining the Earth: An Integrated Approach. U.S.: Thomson Advantage Books, p. 160. ISBN 0534496725

- ^ Dean, J. F. (2018). "Methane feedbacks to the global climate system in a warmer world". Reviews of Geophysics. 56 (1): 207–250. Bibcode:2018RvGeo..56..207D. doi:10.1002/2017RG000559. hdl:1874/366386.

- ^ Boswell, Ray; Collett, Timothy S. (2011). "Current perspectives on gas hydrate resources". Energy Environ. Sci. 4 (4): 1206–1215. doi:10.1039/c0ee00203h.

- ^ أ ب Ruppel; Kessler (2017). "The interaction of climate change and methane hydrates". Reviews of Geophysics. 55 (1): 126–168. Bibcode:2017RvGeo..55..126R. doi:10.1002/2016RG000534. hdl:1912/8978. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ "New source of methane discovered in the Arctic Ocean". phys.org. May 1, 2015. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Methane Releases From Arctic Shelf May Be Much Larger and Faster Than Anticipated" (Press release). National Science Foundation (NSF). March 10, 2010. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ Connor, Steve (December 13, 2011). "Vast methane 'plumes' seen in Arctic ocean as sea ice retreats". The Independent. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ "Arctic sea ice reaches lowest extent for the year and the satellite record" (Press release). The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). September 19, 2012. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ "Frontiers 2018/19: Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern". UN Environment. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ "Scientists shocked by Arctic permafrost thawing 70 years sooner than predicted". The Guardian. Reuters. June 18, 2019. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Shindell, Drew; Kuylenstierna, Johan C. I.; Vignati, Elisabetta; van Dingenen, Rita; Amann, Markus; Klimont, Zbigniew; Anenberg, Susan C.; Muller, Nicholas; Janssens-Maenhout, Greet; Raes, Frank; Schwartz, Joel; Faluvegi, Greg; Pozzoli, Luca; Kupiainen, Kaarle; Höglund-Isaksson, Lena; Emberson, Lisa; Streets, David; Ramanathan, V.; Hicks, Kevin; Oanh, N. T. Kim; Milly, George; Williams, Martin; Demkine, Volodymyr; Fowler, David (2012-01-13). "Simultaneously mitigating near-term climate change and improving human health and food security". Science. 335 (6065): 183–189. Bibcode:2012Sci...335..183S. doi:10.1126/science.1210026. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 22246768. S2CID 14113328.

- ^ Dozolme, Philippe. "Common Mining Accidents". About.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ Messina, Lawrence & Bluestein, Greg (April 8, 2010). "Fed official: Still too soon for W.Va. mine rescue". News.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ^ OSMAN, Karim; GENIAUT, Baptiste; HERCHIN, Nicolas; BLANCHETIERE, Vincent (2015). "A review of damages observed after catastrophic events experienced in the mid-stream gas industry compared to consequences modelling tools" (PDF). Symposium Series. 160 (25). Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Casal, Joaquim; Gómez-Mares, Mercedes; Muñoz, Miguel; Palacios, Adriana (2012). "Jet Fires: a "Minor" Fire Hazard?" (PDF). Chemical Engineering Transactions. 26: 13–20. doi:10.3303/CET1226003. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Porter Ranch gas leak permanently capped, officials say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ Matt McGrath (February 26, 2016). "California methane leak 'largest in US history'". BBC. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ "The Massive Methane Blowout In Aliso Canyon Was The Largest in U.S. History". ThinkProgress. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ Tim Walker (January 2, 2016). "California methane gas leak 'more damaging than Deepwater Horizon disaster'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2016-01-04. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (May 9, 2023). "'Mind-boggling' methane emissions from Turkmenistan revealed". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ أ ب Zubrin, R. M.; Muscatello, A. C.; Berggren, M. (2013). "Integrated Mars in Situ Propellant Production System". Journal of Aerospace Engineering. 26: 43–56. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)AS.1943-5525.0000201.

- ^ "Methane Blast". NASA. May 4, 2007. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (November 2, 2012). "Hope of Methane on Mars Fades". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ^ Atreya, Sushil K.; Mahaffy, Paul R.; Wong, Ah-San (2007). "Methane and related trace species on Mars: origin, loss, implications for life, and habitability". Planetary and Space Science. 55 (3): 358–369. Bibcode:2007P&SS...55..358A. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2006.02.005. hdl:2027.42/151840.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne; Wendel, JoAnna; Steigerwald, Bill; Jones, Nancy; Good, Andrew (June 7, 2018). "Release 18-050 – NASA Finds Ancient Organic Material, Mysterious Methane on Mars". NASA. Archived from the original on June 7, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ NASA (June 7, 2018). "Ancient Organics Discovered on Mars – video (03:17)". NASA. Archived from the original on June 7, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Wall, Mike (June 7, 2018). "Curiosity Rover Finds Ancient 'Building Blocks for Life' on Mars". Space.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (June 7, 2018). "Life on Mars? Rover's Latest Discovery Puts It 'On the Table' – The identification of organic molecules in rocks on the red planet does not necessarily point to life there, past or present, but does indicate that some of the building blocks were present". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Voosen, Paul (June 7, 2018). "NASA rover hits organic pay dirt on Mars". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aau3992. S2CID 115442477.

- ^ ten Kate, Inge Loes (June 8, 2018). "Organic molecules on Mars". Science. 360 (6393): 1068–1069. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1068T. doi:10.1126/science.aat2662. PMID 29880670. S2CID 46952468.

- ^ Webster, Christopher R.; et al. (June 8, 2018). "Background levels of methane in Mars' atmosphere show strong seasonal variations". Science. 360 (6393): 1093–1096. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1093W. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0131. PMID 29880682.

- ^ Eigenbrode, Jennifer L.; et al. (June 8, 2018). "Organic matter preserved in 3-billion-year-old mudstones at Gale crater, Mars". Science. 360 (6393): 1096–1101. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1096E. doi:10.1126/science.aas9185. PMID 29880683.

- ^ Richardson, Derek (September 27, 2016). "Elon Musk Shows Off Interplanetary Transport System". Spaceflight Insider. Archived from the original on October 1, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ Oze, C.; Sharma, M. (2005). "Have olivine, will gas: Serpentinization and the abiogenic production of methane on Mars". Geophysical Research Letters. 32 (10): L10203. Bibcode:2005GeoRL..3210203O. doi:10.1029/2005GL022691. S2CID 28981740.

- ^ Volta, Alessandro (1777) Lettere del Signor Don Alessandro Volta ... Sull' Aria Inflammable Nativa Delle Paludi Archived نوفمبر 6, 2018 at the Wayback Machine [Letters of Signor Don Alessandro Volta ... on the flammable native air of the marshes], Milan, Italy: Giuseppe Marelli.

- ^ أ ب Methane. BookRags. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ Holland, John (1841). The history and description of fossil fuel, the collieries, and coal trade of Great Britain. London, Whittaker and Co. pp. 271–272. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ Hofmann, A. W. (1866). "On the action of trichloride of phosphorus on the salts of the aromatic monoamines". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 15: 55–62. JSTOR 112588. Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2016.; see footnote on pp. 57–58

- ^ McBride, James Michael (1999) "Development of systematic names for the simple alkanes". Chemistry Department, Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut). Archived مارس 16, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dozolme, Philippe. "Common Mining Accidents". About.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ Messina, Lawrence & Bluestein, Greg (April 8, 2010). "Fed official: Still too soon for W.Va. mine rescue". News.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

وصلات خارجية

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from August 2021

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Articles with changed KEGG identifier

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- Chembox image size set

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2021

- ميثان

- هضم لاهوائي

- غاز الوقود

- وقود

- غازات الدفيئة

- غازات صناعية

- جزيئات إشارة غازية