نيو أورلينز

New Orleans

La Nouvelle-Orléans (فرنسية) | |

|---|---|

| الكنية: "The Crescent City", "The Big Easy", "The City That Care Forgot", "NOLA", "The City of Yes", "Hollywood South", "The Creole City" | |

Location within the U.S. state of Louisiana | |

| الإحداثيات: {{WikidataCoord}} – malformed coordinate data | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Orleans |

| Founded | 1718 |

| أسسها | Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville |

| السمِيْ | Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1674–1723) |

| الحكومة | |

| • النوع | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | LaToya Cantrell (D) |

| • Council | New Orleans City Council |

| المساحة | |

| • Consolidated city-parish | 349٫85 ميل² (906٫10 كم²) |

| • البر | 169٫42 ميل² (438٫80 كم²) |

| • الماء | 180٫43 ميل² (467٫30 كم²) |

| • العمران | 3٬755٫2 ميل² (9٬726٫6 كم²) |

| المنسوب | −6٫5 to 20 ft (−2 to 6 m) |

| التعداد | |

| • Consolidated city-parish | 383٬997 |

| • الكثافة | 2٬267/sq mi (875/km2) |

| • Urban | 963٬212 (US: 49th) |

| • الكثافة الحضرية | 3٬563٫8/sq mi (1٬376٫0/km2) |

| • العمرانية | 1٬270٬530 (US: 45th) |

| صفة المواطن | New Orleanian |

| GDP | |

| • Consolidated city-parish | $29.147 billion (2022) |

| • MSA | $94.031 billion (2022) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 504 |

| FIPS code | 22-55000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1629985 |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | nola.gov |

نيو اورلينز (إنگليزية: New Orleans ؛ /ˈɔːrl(i)ənz/ OR-l(ee)ənz, /ɔːrˈliːnz/ or-LEENZ,[6] locally /ˈɔːrlənz/ OR-lənz;[7] فرنسية: La Nouvelle-Orléans [la nuvɛlɔʁleɑ̃] (![]() استمع)) هي مدينة-أبرشية أمريكية، وأكبر مدن ولاية لويزيانا. تقع في جنوب شرق الولاية على ضفاف نهر المسيسيبي. With a population of 383,997 according to the 2020 U.S. census,[8] it is the most populous city in Louisiana and the French Louisiana region;[9] third most populous city in the Deep South; and the twelfth-most populous city in the southeastern United States. Serving as a major port, New Orleans is considered an economic and commercial hub for the broader Gulf Coast region of the United States.

استمع)) هي مدينة-أبرشية أمريكية، وأكبر مدن ولاية لويزيانا. تقع في جنوب شرق الولاية على ضفاف نهر المسيسيبي. With a population of 383,997 according to the 2020 U.S. census,[8] it is the most populous city in Louisiana and the French Louisiana region;[9] third most populous city in the Deep South; and the twelfth-most populous city in the southeastern United States. Serving as a major port, New Orleans is considered an economic and commercial hub for the broader Gulf Coast region of the United States.

New Orleans is world-renowned for its distinctive music, Creole cuisine, unique dialects, and its annual celebrations and festivals, most notably Mardi Gras. The historic heart of the city is the French Quarter, known for its French and Spanish Creole architecture and vibrant nightlife along Bourbon Street. The city has been described as the "most unique" in the United States,[10][11][12][13] owing in large part to its cross-cultural and multilingual heritage.[14] Additionally, New Orleans has increasingly been known as "Hollywood South" due to its prominent role in the film industry and in pop culture.[15][16]

Founded in 1718 by French colonists, New Orleans was once the territorial capital of French Louisiana before becoming part of the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. New Orleans in 1840 was the third most populous city in the United States,[17] and it was the largest city in the American South from the Antebellum era until after World War II. The city has historically been very vulnerable to flooding, due to its high rainfall, low lying elevation, poor natural drainage, and proximity to multiple bodies of water. State and federal authorities have installed a complex system of levees and drainage pumps in an effort to protect the city.[18][19]

New Orleans was severely affected by Hurricane Katrina in August 2005, which flooded more than 80% of the city, killed more than 1,800 people, and displaced thousands of residents, causing a population decline of over 50%.[20] Since Katrina, major redevelopment efforts have led to a rebound in the city's population. Concerns have been expressed about gentrification, new residents buying property in formerly closely knit communities, and displacement of longtime residents.[21][22][23][24] Additionally, high rates of violent crime continue to plague the city with New Orleans experiencing 280 murders in 2022, resulting in the highest per capita homicide rate in the United States.[25][26]

The city and Orleans Parish (فرنسية: paroisse d'Orléans) are coterminous.[27] As of 2017, Orleans Parish is the third most populous parish in Louisiana, behind East Baton Rouge Parish and neighboring Jefferson Parish.[28] The city and parish are bounded by St. Tammany Parish and Lake Pontchartrain to the north, St. Bernard Parish and Lake Borgne to the east, Plaquemines Parish to the south, and Jefferson Parish to the south and west.

The city anchors the larger Greater New Orleans metropolitan area, which had a population of 1,271,845 in 2020.[29] Greater New Orleans is the most populous metropolitan statistical area (MSA) in Louisiana and, since the 2020 census, has been the 46th most populous MSA in the United States.[30]

أصل الاسم والكنى

The name of New Orleans derives from the original French name (La Nouvelle-Orléans), which was given to the city in honor of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, who served as Louis XV's regent from 1715 to 1723.[31] The French city of Orléans itself is named after the Roman emperor Aurelian, originally being known as Aurelianum. Thus, by extension, since New Orleans is also named after Aurelian, its name in Latin would translate to Nova Aurelia.

Following France's defeat in the Seven Years' War and the Treaty of Paris, which was signed in 1763, France transferred possession of Louisiana to Spain. The Spanish renamed the city to Nueva Orleans (النطق الإسپاني: [ˌnweβa oɾleˈans]), which was used until 1800.[32] When the United States acquired possession from France in 1803, the French name was adopted and anglicized to become the modern name, which is still in use today.

New Orleans has several nicknames, including these:

- Crescent City, alluding to the course of the Lower Mississippi River around and through the city.[33]

- The Big Easy, possibly a reference by musicians in the early 20th century to the relative ease of finding work there.[34][35]

- The City that Care Forgot, used since at least 1938,[36] referring to the outwardly easygoing, carefree nature of the residents.[35]

- NOLA, the acronym for New Orleans, Louisiana.

التاريخ

فترة الاستعمار الفرنسي-الإسپاني

La Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans) was founded in the spring of 1718 (May 7 has become the traditional date to mark the anniversary, but the actual day is unknown)[37] by the French Mississippi Company, under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, on land inhabited by the Chitimacha. It was named for Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, who was regent of the Kingdom of France at the time.[31] His title came from the French city of Orléans. The French colony of Louisiana was ceded to the Spanish Empire in the 1763 Treaty of Paris, following France's defeat by Great Britain in the Seven Years' War. During the American Revolutionary War, New Orleans was an important port for smuggling aid to the American revolutionaries, and transporting military equipment and supplies up the Mississippi River. Beginning in the 1760s, Filipinos began to settle in and around New Orleans.[38] Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez successfully directed a southern campaign against the British from the city in 1779.[39] Nueva Orleans (the name of New Orleans in Spanish)[40] remained under Spanish control until 1803, when it reverted briefly to French rule. Nearly all of the surviving 18th-century architecture of the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) dates from the Spanish period, notably excepting the Old Ursuline Convent.[41]

As a French colony, Louisiana faced struggles with numerous Native American tribes, who were navigating the competing interests of France, Spain, and England, as well as traditional rivals. Notably, the Natchez, whose traditional lands were along the Mississippi near the modern city of Natchez, Mississippi, had a series of wars culminating in the Natchez Revolt that began in 1729 with the Natchez overrunning Fort Rosalie. Approximately 230 French colonists were killed and the Natchez settlement destroyed, causing fear and concern in New Orleans and the rest of the territory.[42] In retaliation, then-governor Étienne Perier launched a campaign to completely destroy the Natchez nation and its Native allies.[43] By 1731, the Natchez people had been killed, enslaved, or dispersed among other tribes, but the campaign soured relations between France and the territory's Native Americans leading directly into the Chickasaw Wars of the 1730s.[44]

Relations with Louisiana's Native American population remained a concern into the 1740s for governor Marquis de Vaudreuil. In the early 1740s traders from the Thirteen Colonies crossed into the Appalachian Mountains. The Native American tribes would now operate dependent on which of various European colonists would most benefit them. Several of these tribes and especially the Chickasaw and Choctaw would trade goods and gifts for their loyalty.[45] The economic issue in the colony, which continued under Vaudreuil, resulted in many raids by Native American tribes, taking advantage of the French weakness. In 1747 and 1748, the Chickasaw would raid along the east bank of the Mississippi all the way south to Baton Rouge. These raids would often force residents of French Louisiana to take refuge in New Orleans proper.

Inability to find labor was the most pressing issue in the young colony. The colonists turned to sub-Saharan African slaves to make their investments in Louisiana profitable. In the late 1710s the transatlantic slave trade imported enslaved Africans into the colony. This led to the biggest shipment in 1716 where several trading ships appeared with slaves as cargo to the local residents in a one-year span.

By 1724, the large number of blacks in Louisiana prompted the institutionalizing of laws governing slavery within the colony.[46] These laws required that slaves be baptized in the Roman Catholic faith, slaves be married in the church; the slave law formed in the 1720s is known as the Code Noir, which would bleed into the antebellum period of the American South as well. Louisiana slave culture had its own distinct Afro-Creole society that called on past cultures and the situation for slaves in the New World. Afro-Creole was present in religious beliefs and the Louisiana Creole language. The religion most associated with this period was called Voodoo.[47][48]

In the city of New Orleans an inspiring mixture of foreign influences created a melting pot of culture that is still celebrated today. By the end of French colonization in Louisiana, New Orleans was recognized commercially in the Atlantic world. Its inhabitants traded across the French commercial system. New Orleans was a hub for this trade both physically and culturally because it served as the exit point to the rest of the globe for the interior of the North American continent.

In one instance the French government established a chapter house of sisters in New Orleans. The Ursuline sisters after being sponsored by the Company of the Indies, founded a convent in the city in 1727.[49] At the end of the colonial era, the Ursuline Academy maintained a house of 70 boarding and 100 day students. Today numerous schools in New Orleans can trace their lineage from this academy.

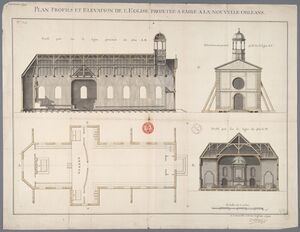

Another notable example is the street plan and architecture still distinguishing New Orleans today. French Louisiana had early architects in the province who were trained as military engineers and were now assigned to design government buildings. Pierre Le Blond de Tour and Adrien de Pauger, for example, planned many early fortifications, along with the street plan for the city of New Orleans.[50] After them in the 1740s, Ignace François Broutin, as engineer-in-chief of Louisiana, reworked the architecture of New Orleans with an extensive public works program.

French policy-makers in Paris attempted to set political and economic norms for New Orleans. It acted autonomously in much of its cultural and physical aspects, but also stayed in communication with the foreign trends as well.

After the French relinquished West Louisiana to the Spanish, New Orleans merchants attempted to ignore Spanish rule and even re-institute French control on the colony. The citizens of New Orleans held a series of public meetings during 1765 to keep the populace in opposition of the establishment of Spanish rule. Anti-Spanish passions in New Orleans reached their highest level after two years of Spanish administration in Louisiana. On October 27, 1768, a mob of local residents, spiked the guns guarding New Orleans and took control of the city from the Spanish.[51] The rebellion organized a group to sail for Paris, where it met with officials of the French government. This group brought with them a long memorial to summarize the abuses the colony had endured from the Spanish. King Louis XV and his ministers reaffirmed Spain's sovereignty over Louisiana.

فترة الإقليم ضمن الولايات المتحدة

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800 restored French control of New Orleans and Louisiana, but Napoleon sold both to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.[52] Thereafter, the city grew rapidly with influxes of Americans, French, Creoles and Africans. Later immigrants were Irish, Germans, Poles and Italians. Major commodity crops of sugar and cotton were cultivated with slave labor on nearby large plantations.

Between 1791 and 1810, thousands of St. Dominican refugees from the Haitian Revolution, both whites and free people of color (affranchis or gens de couleur libres), arrived in New Orleans; a number brought their slaves with them, many of whom were native Africans or of full-blood descent.[53] While Governor Claiborne and other officials wanted to keep out additional free black people, the French Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking population. In addition to bolstering the territory's French-speaking population, these refugees had a significant impact on the culture of Louisiana, including developing its sugar industry and cultural institutions.[54]

As more refugees were allowed into the Territory of Orleans, St. Dominican refugees who had first gone to Cuba also arrived.[55] Many of the white Francophones had been deported by officials in Cuba in 1809 as retaliation for Bonapartist schemes.[56] Nearly 90 percent of these immigrants settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free people of color (of mixed-race European and African descent), and 3,226 slaves of primarily African descent, doubling the city's population. The city became 63 percent black, a greater proportion than Charleston, South Carolina's 53 percent at that time.[55]

البداية في القرن التاسع عشر

أنشئت مدينة نيو أورلينز في عام 1718 بواسطة شركة المسيسيبي الفرنسية ، تحت إدارة جان بابتست لو موين دي بينفيل. وقد سميت على إسم المدينة الفرنسية أورلينز. وكانت في البداية تحت الحكم الفرنسي ثم أصبحت تحت الحكم الأسباني حتى عام 1801 ، ثم رجعت للحكم الفرنسي مرة أخرى. بعد ذلك باع نابليون العديد من الأراضي من ضمنها أراضي نيو أورلينز لولاية لويزيانا ، وبدأت المدينة في النمو السريع ، وكان من أشهر محصولاتها القطن و السكر والتي كان يعتمد في زراعتهم على العبيد القادمين من خارج المدينة.

معركة نيو أورلينز

During the final campaign of the War of 1812, the British sent a force of 11,000 in an attempt to capture New Orleans. Despite great challenges, General Andrew Jackson, with support from the U.S. Navy, successfully cobbled together a force of militia from Louisiana and Mississippi, U.S. Army regulars, a large contingent of Tennessee state militia, Kentucky frontiersmen and local privateers (the latter led by the pirate Jean Lafitte), to decisively defeat the British, led by Sir Edward Pakenham, in the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815.[58]

The armies had not learned of the Treaty of Ghent, which had been signed on December 24, 1814 (however, the treaty did not call for cessation of hostilities until after both governments had ratified it. The U.S. government ratified it on February 16, 1815). The fighting in Louisiana began in December 1814 and did not end until late January, after the Americans held off the Royal Navy during a ten-day siege of Fort St. Philip (the Royal Navy went on to capture Fort Bowyer near Mobile, before the commanders received news of the peace treaty).[58]

الميناء

As a port, New Orleans played a major role during the antebellum period in the Atlantic slave trade. The port handled commodities for export from the interior and imported goods from other countries, which were warehoused and transferred in New Orleans to smaller vessels and distributed along the Mississippi River watershed. The river was filled with steamboats, flatboats and sailing ships. Despite its role in the slave trade, New Orleans at the time also had the largest and most prosperous community of free persons of color in the nation, who were often educated, middle-class property owners.[59][60]

Dwarfing the other cities in the Antebellum South, New Orleans had the U.S.' largest slave market. The market expanded after the United States ended the international trade in 1808. Two-thirds of the more than one million slaves brought to the Deep South arrived via forced migration in the domestic slave trade. The money generated by the sale of slaves in the Upper South has been estimated at 15 percent of the value of the staple crop economy. The slaves were collectively valued at half a billion dollars. The trade spawned an ancillary economy—transportation, housing and clothing, fees, etc., estimated at 13.5 percent of the price per person, amounting to tens of billions of dollars (2005 dollars, adjusted for inflation) during the antebellum period, with New Orleans as a prime beneficiary.[61]

According to historian Paul Lachance,

the addition of white immigrants [from Saint-Domingue] to the white creole population enabled French-speakers to remain a majority of the white population until almost 1830. If a substantial proportion of free persons of color and slaves had not also spoken French, however, the Gallic community would have become a minority of the total population as early as 1820.[62]

After the Louisiana Purchase, numerous Anglo-Americans migrated to the city. The population doubled in the 1830s and by 1840, New Orleans had become the nation's wealthiest and the third-most populous city, after New York and Baltimore.[63] German and Irish immigrants began arriving in the 1840s, working as port laborers. In this period, the state legislature passed more restrictions on manumissions of slaves and virtually ended it in 1852.[64]

In the 1850s, white Francophones remained an intact and vibrant community in New Orleans. They maintained instruction in French in two of the city's four school districts (all served white students).[65] In 1860, the city had 13,000 free people of color (gens de couleur libres), the class of free, mostly mixed-race people that expanded in number during French and Spanish rule. They set up some private schools for their children. The census recorded 81 percent of the free people of color as mulatto, a term used to cover all degrees of mixed race.[64] Mostly part of the Francophone group, they constituted the artisan, educated and professional class of African Americans. The mass of blacks were still enslaved, working at the port, in domestic service, in crafts, and mostly on the many large, surrounding sugarcane plantations.

Throughout New Orleans' history, until the early 20th century when medical and scientific advances ameliorated the situation, the city suffered repeated epidemics of yellow fever and other tropical and infectious diseases.[66] In the first half of the 19th century, yellow fever epidemics killed over 150,000 people in New Orleans.[67]

After growing by 45 percent in the 1850s, by 1860, the city had nearly 170,000 people.[68] It had grown in wealth, with a "per capita income [that] was second in the nation and the highest in the South."[68] The city had a role as the "primary commercial gateway for the nation's booming midsection."[68] The port was the nation's third largest in terms of tonnage of imported goods, after Boston and New York, handling 659,000 tons in 1859.[68]

الحرب الأهلية–فترة إعادة البناء

As the Creole elite feared, the American Civil War changed their world. In April 1862, following the city's occupation by the Union Navy after the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, Gen. Benjamin F. Butler – a respected Massachusetts lawyer serving in that state's militia – was appointed military governor. New Orleans residents supportive of the Confederacy nicknamed him "Beast" Butler, because of an order he issued. After his troops had been assaulted and harassed in the streets by women still loyal to the Confederate cause, his order warned that such future occurrences would result in his men treating such women as those "plying their avocation in the streets", implying that they would treat the women like prostitutes. Accounts of this spread widely. He also came to be called "Spoons" Butler because of the alleged looting that his troops did while occupying the city, during which time he himself supposedly pilfered silver flatware.[69]

Significantly, Butler abolished French-language instruction in city schools. Statewide measures in 1864 and, after the war, 1868 further strengthened the English-only policy imposed by federal representatives. With the predominance of English speakers, that language had already become dominant in business and government.[65] By the end of the 19th century, French usage had faded. It was also under pressure from Irish, Italian and German immigrants.[70] However, as late as 1902 "one-fourth of the population of the city spoke French in ordinary daily intercourse, while another two-fourths was able to understand the language perfectly,"[71] and as late as 1945, many elderly Creole women spoke no English.[72] The last major French language newspaper, L'Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans Bee), ceased publication on December 27, 1923, after 96 years.[73] According to some sources, Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans continued until 1955.[74]

As the city was captured and occupied early in the war, it was spared the destruction through warfare suffered by many other cities of the American South. The Union Army eventually extended its control north along the Mississippi River and along the coastal areas. As a result, most of the southern portion of Louisiana was originally exempted from the liberating provisions of the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln. Large numbers of rural ex-slaves and some free people of color from the city volunteered for the first regiments of Black troops in the War. Led by Brigadier General Daniel Ullman (1810–1892), of the 78th Regiment of New York State Volunteers Militia, they were known as the "Corps d'Afrique". While that name had been used by a militia before the war, that group was composed of free people of color. The new group was made up mostly of former slaves. They were supplemented in the last two years of the War by newly organized United States Colored Troops, who played an increasingly important part in the war.[75]

Violence throughout the South, especially the Memphis Riots of 1866 followed by the New Orleans Riot in the same year, led Congress to pass the Reconstruction Act and the Fourteenth Amendment, extending the protections of full citizenship to freedmen and free people of color. Louisiana and Texas were put under the authority of the "Fifth Military District" of the United States during Reconstruction. Louisiana was readmitted to the Union in 1868. Its Constitution of 1868 granted universal male suffrage and established universal public education. Both blacks and whites were elected to local and state offices. In 1872, lieutenant governor P.B.S. Pinchback, who was of mixed race, succeeded Henry Clay Warmouth for a brief period as Republican governor of Louisiana, becoming the first governor of African descent of a U.S. state (the next African American to serve as governor of a U.S. state was Douglas Wilder, elected in Virginia in 1989). New Orleans operated a racially integrated public school system during this period.

Wartime damage to levees and cities along the Mississippi River adversely affected southern crops and trade. The federal government contributed to restoring infrastructure. The nationwide financial recession and Panic of 1873 adversely affected businesses and slowed economic recovery.

From 1868, elections in Louisiana were marked by violence, as white insurgents tried to suppress black voting and disrupt Republican Party gatherings. The disputed 1872 gubernatorial election resulted in conflicts that ran for years. The "White League", an insurgent paramilitary group that supported the Democratic Party, was organized in 1874 and operated in the open, violently suppressing the black vote and running off Republican officeholders. In 1874, in the Battle of Liberty Place, 5,000 members of the White League fought with city police to take over the state offices for the Democratic candidate for governor, holding them for three days. By 1876, such tactics resulted in the white Democrats, the so-called Redeemers, regaining political control of the state legislature. The federal government gave up and withdrew its troops in 1877, ending Reconstruction.

In 1892 the racially integrated unions of New Orleans led a general strike in the city from November 8 to 12, shutting down the city & winning the vast majority of their demands.[76][77]

فترة جيم كرو

Dixiecrats passed Jim Crow laws, establishing racial segregation in public facilities. In 1889, the legislature passed a constitutional amendment incorporating a "grandfather clause" that effectively disfranchised freedmen as well as the propertied people of color manumitted before the war. Unable to vote, African Americans could not serve on juries or in local office, and were closed out of formal politics for generations. The Southern U.S. was ruled by a white Democratic Party. Public schools were racially segregated and remained so until 1960.

New Orleans' large community of well-educated, often French-speaking free persons of color (gens de couleur libres), who had been free prior to the Civil War, fought against Jim Crow. They organized the Comité des Citoyens (Citizens Committee) to work for civil rights. As part of their legal campaign, they recruited one of their own, Homer Plessy, to test whether Louisiana's newly enacted Separate Car Act was constitutional. Plessy boarded a commuter train departing New Orleans for Covington, Louisiana, sat in the car reserved for whites only, and was arrested. The case resulting from this incident, Plessy v. Ferguson, was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896. The court ruled that "separate but equal" accommodations were constitutional, effectively upholding Jim Crow measures.

In practice, African American public schools and facilities were underfunded across the South. The Supreme Court ruling contributed to this period as the nadir of race relations in the United States. The rate of lynchings of black men was high across the South, as other states also disfranchised blacks and sought to impose Jim Crow. Nativist prejudices also surfaced. Anti-Italian sentiment in 1891 contributed to the lynchings of 11 Italians, some of whom had been acquitted of the murder of the police chief. Some were shot and killed in the jail where they were detained. It was the largest mass lynching in U.S. history.[78][79] In July 1900 the city was swept by white mobs rioting after Robert Charles, a young African American, killed a policeman and temporarily escaped. The mob killed him and an estimated 20 other blacks; seven whites died in the days-long conflict, until a state militia suppressed it.

القرن العشرين

New Orleans' economic and population zenith in relation to other American cities occurred in the antebellum period. It was the nation's fifth-largest city in 1860 (after New York, Philadelphia, Boston and Baltimore) and was significantly larger than all other southern cities.[80] From the mid-19th century onward rapid economic growth shifted to other areas, while New Orleans' relative importance steadily declined. The growth of railways and highways decreased river traffic, diverting goods to other transportation corridors and markets.[80] Thousands of the most ambitious people of color left the state in the Great Migration around World War II and after, many for West Coast destinations. From the late 1800s, most censuses recorded New Orleans slipping down the ranks in the list of largest American cities (New Orleans' population still continued to increase throughout the period, but at a slower rate than before the Civil War).

In 1929 the New Orleans streetcar strike during which serious unrest occurred.[81] It is also credited for the creation of the distinctly Louisianan Po' boy sandwich.[82][83]

By the mid-20th century, New Orleanians recognized that their city was no longer the leading urban area in the South. By 1950, Houston, Dallas, and Atlanta exceeded New Orleans in size, and in 1960 Miami eclipsed New Orleans, even as the latter's population reached its historic peak.[80] As with other older American cities, highway construction and suburban development drew residents from the center city to newer housing outside. The 1970 census recorded the first absolute decline in population since the city became part of the United States in 1803. The Greater New Orleans metropolitan area continued expanding in population, albeit more slowly than other major Sun Belt cities. While the port remained one of the nation's largest, automation and containerization cost many jobs. The city's former role as banker to the South was supplanted by larger peer cities. New Orleans' economy had always been based more on trade and financial services than on manufacturing, but the city's relatively small manufacturing sector also shrank after World War II. Despite some economic development successes under the administrations of DeLesseps "Chep" Morrison (1946–1961) and Victor "Vic" Schiro (1961–1970), metropolitan New Orleans' growth rate consistently lagged behind more vigorous cities.

حركة الحقوق المدنية

During the later years of Morrison's administration, and for the entirety of Schiro's, the city was a center of the Civil Rights movement. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference was founded in New Orleans, and lunch counter sit-ins were held in Canal Street department stores. A prominent and violent series of confrontations occurred in 1960 when the city attempted school desegregation, following the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). When six-year-old Ruby Bridges integrated William Frantz Elementary School in the Ninth Ward, she was the first child of color to attend a previously all-white school in the South. Much controversy preceded the 1956 Sugar Bowl at Tulane Stadium, when the Pitt Panthers, with African-American fullback Bobby Grier on the roster, met the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets.[84] There had been controversy over whether Grier should be allowed to play due to his race, and whether Georgia Tech should even play at all due to Georgia's Governor Marvin Griffin's opposition to racial integration.[85][86][87] After Griffin publicly sent a telegram to the state's Board Of Regents requesting Georgia Tech not to engage in racially integrated events, Georgia Tech's president Blake R. Van Leer rejected the request and threatened to resign. The game went on as planned.[88]

The Civil Rights movement's success in gaining federal passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 renewed constitutional rights, including voting for blacks. Together, these resulted in the most far-reaching changes in New Orleans' 20th century history.[89] Though legal and civil equality were re-established by the end of the 1960s, a large gap in income levels and educational attainment persisted between the city's White and African American communities.[90] As the middle class and wealthier members of both races left the center city, its population's income level dropped, and it became proportionately more African American. From 1980, the African American majority elected primarily officials from its own community. They struggled to narrow the gap by creating conditions conducive to the economic uplift of the African American community.

New Orleans became increasingly dependent on tourism as an economic mainstay during the administrations of Sidney Barthelemy (1986–1994) and Marc Morial (1994–2002). Relatively low levels of educational attainment, high rates of household poverty, and rising crime threatened the city's prosperity in the later decades of the century.[90] The negative effects of these socioeconomic conditions aligned poorly with the changes in the late-20th century to the economy of the United States, which reflected a post-industrial, knowledge-based paradigm in which mental skills and education were more important to advancement than manual skills.

الصرف والسيطرة على الفيضان

In the 20th century, New Orleans' government and business leaders believed they needed to drain and develop outlying areas to provide for the city's expansion. The most ambitious development during this period was a drainage plan devised by engineer and inventor A. Baldwin Wood, designed to break the surrounding swamp's stranglehold on the city's geographic expansion. Until then, urban development in New Orleans was largely limited to higher ground along the natural river levees and bayous.

Wood's pump system allowed the city to drain huge tracts of swamp and marshland and expand into low-lying areas. Over the 20th century, rapid subsidence, both natural and human-induced, resulted in these newly populated areas subsiding to several feet below sea level.[91][92]

New Orleans was vulnerable to flooding even before the city's footprint departed from the natural high ground near the Mississippi River. In the late 20th century, however, scientists and New Orleans residents gradually became aware of the city's increased vulnerability. In 1965, flooding from Hurricane Betsy killed dozens of residents, although the majority of the city remained dry. The rain-induced flood of May 8, 1995, demonstrated the weakness of the pumping system. After that event, measures were undertaken to dramatically upgrade pumping capacity. By the 1980s and 1990s, scientists observed that extensive, rapid, and ongoing erosion of the marshlands and swamp surrounding New Orleans, especially that related to the Mississippi River–Gulf Outlet Canal, had the unintended result of leaving the city more vulnerable than before to hurricane-induced catastrophic storm surges.

القرن 21

إعصار كاترينا

في نهاية أغسطس 2005 وصل إعصار كاترينا المدمر إلى مدينة نيو أورلينز وكذلك عبر الإعصار منطقة الخليج الأمريكي ، وقد تم إجلاء معظم سكان المدينة ، وتعتبر تلك الكارثة من أسوأ الكوارث في التاريخ الأمريكي.[93] تم إعادة بناء الجسور والسدود بواسطة قوات الجيش الأمريكي ، والتي كانت قد إنهارت بعد إجتياج الإعصار للمدينة. تم إنقاذ 80 % من سكان المدينة وأجلي منهم 10.000 مواطن للمدن المجاورة في ولاية لويزيانا.[94]

إعصار ريتا

بعدما شرع في التخطيط لإصلاح وإعادة بناء مدينة نيو أورلينز بعدما إجتاحها إعصار كاترينا وسبب في تدمير الكثير من المنشئات ، جاء إعصار ريتا وذلك في سبتمبر 2005 مما سبب تأجيل مهام إعادة الإعمار.[95]

الإنتعاش بعد الكوارث

الجغرافيا

New Orleans is located in the Mississippi River Delta, south of Lake Pontchartrain, on the banks of the Mississippi River, approximately 105 ميل (169 km) upriver from the Gulf of Mexico. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city's area is 350 ميل مربع (910 km2), of which 169 ميل مربع (440 km2) is land and 181 ميل مربع (470 km2) (52%) is water.[96] The area along the river is characterized by ridges and hollows.

المنسوب

New Orleans was originally settled on the river's natural levees or high ground. After the Flood Control Act of 1965, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built floodwalls and man-made levees around a much larger geographic footprint that included previous marshland and swamp. Over time, pumping of water from marshland allowed for development into lower elevation areas. Today, half of the city is at or below local mean sea level, while the other half is slightly above sea level. Evidence suggests that portions of the city may be dropping in elevation due to subsidence.[97]

A 2007 study by Tulane and Xavier University suggested that "51%... of the contiguous urbanized portions of Orleans, Jefferson, and St. Bernard parishes lie at or above sea level," with the more densely populated areas generally on higher ground. The average elevation of the city is currently between 1 و 2 أقدام (0.30 و 0.61 m) below sea level, with some portions of the city as high as 20 أقدام (6 m) at the base of the river levee in Uptown and others as low as 7 أقدام (2 m) below sea level in the farthest reaches of Eastern New Orleans.[98][99] A study published by the ASCE Journal of Hydrologic Engineering in 2016, however, stated:

...most of New Orleans proper—about 65%—is at or below mean sea level, as defined by the average elevation of Lake Pontchartrain[100]

The magnitude of subsidence potentially caused by the draining of natural marsh in the New Orleans area and southeast Louisiana is a topic of debate. A study published in Geology in 2006 by an associate professor at Tulane University claims:

While erosion and wetland loss are huge problems along Louisiana's coast, the basement 30 أقدام (9.1 m) to 50 أقدام (15 m) beneath much of the Mississippi Delta has been highly stable for the past 8,000 years with negligible subsidence rates.[101]

The study noted, however, that the results did not necessarily apply to the Mississippi River Delta, nor the New Orleans metropolitan area proper. On the other hand, a report by the American Society of Civil Engineers claims that "New Orleans is subsiding (sinking)":[102]

Large portions of Orleans, St. Bernard, and Jefferson parishes are currently below sea level—and continue to sink. New Orleans is built on thousands of feet of soft sand, silt, and clay. Subsidence, or settling of the ground surface, occurs naturally due to the consolidation and oxidation of organic soils (called "marsh" in New Orleans) and local groundwater pumping. In the past, flooding and deposition of sediments from the Mississippi River counterbalanced the natural subsidence, leaving southeast Louisiana at or above sea level. However, due to major flood control structures being built upstream on the Mississippi River and levees being built around New Orleans, fresh layers of sediment are not replenishing the ground lost by subsidence.[102]

In May 2016, NASA published a study which suggested that most areas were, in fact, experiencing subsidence at a "highly variable rate" which was "generally consistent with, but somewhat higher than, previous studies."[103]

أفق المدينة

The Central Business District is located immediately north and west of the Mississippi and was historically called the "American Quarter" or "American Sector". It was developed after the heart of French and Spanish settlement. It includes Lafayette Square. Most streets in this area fan out from a central point. Major streets include Canal Street, Poydras Street, Tulane Avenue and Loyola Avenue. Canal Street divides the traditional "downtown" area from the "uptown" area.

Every street crossing Canal Street between the Mississippi River and Rampart Street, which is the northern edge of the French Quarter, has a different name for the "uptown" and "downtown" portions. For example, St. Charles Avenue, known for its street car line, is called Royal Street below Canal Street, though where it traverses the Central Business District between Canal and Lee Circle, it is properly called St. Charles Street.[104] Elsewhere in the city, Canal Street serves as the dividing point between the "South" and "North" portions of various streets. In the local parlance downtown means "downriver from Canal Street", while uptown means "upriver from Canal Street". Downtown neighborhoods include the French Quarter, Tremé, the 7th Ward, Faubourg Marigny, Bywater (the Upper Ninth Ward), and the Lower Ninth Ward. Uptown neighborhoods include the Warehouse District, the Lower Garden District, the Garden District, the Irish Channel, the University District, Carrollton, Gert Town, Fontainebleau and Broadmoor. However, the Warehouse and the Central Business District are frequently called "Downtown" as a specific region, as in the Downtown Development District.

Other major districts within the city include Bayou St. John, Mid-City, Gentilly, Lakeview, Lakefront, New Orleans East and Algiers.

أعلى المباني

For much of its history, New Orleans' skyline displayed only low- and mid-rise structures. The soft soils are susceptible to subsidence, and there was doubt about the feasibility of constructing high rises. Developments in engineering throughout the 20th century eventually made it possible to build sturdy foundations in the foundations that underlie the structures. In the 1960s, the World Trade Center New Orleans and Plaza Tower demonstrated skyscrapers' viability. One Shell Square became the city's tallest building in 1972. The oil boom of the 1970s and early 1980s redefined New Orleans' skyline with the development of the Poydras Street corridor. Most are clustered along Canal Street and Poydras Street in the Central Business District.

| الاسم | الطوابق | الارتفاع |

|---|---|---|

| One Shell Square | 51 | 697 ft (212 m) |

| Place St. Charles | 53 | 645 ft (197 m) |

| Plaza Tower | 45 | 531 ft (162 m) |

| Energy Centre | 39 | 530 ft (160 m) |

| First Bank and Trust Tower | 36 | 481 ft (147 m) |

المناخ

| بيانات المناخ لـ Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport (1991–2020 normals,[أ] extremes 1946–present)[ب] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °ف (°س) | 83 (28) |

85 (29) |

89 (32) |

92 (33) |

97 (36) |

101 (38) |

101 (38) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

97 (36) |

90 (32) |

85 (29) |

102 (39) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °ف (°س) | 62.5 (16.9) |

66.4 (19.1) |

72.3 (22.4) |

78.5 (25.8) |

85.3 (29.6) |

90.0 (32.2) |

91.4 (33.0) |

91.3 (32.9) |

88.1 (31.2) |

80.6 (27.0) |

71.2 (21.8) |

64.8 (18.2) |

78.5 (25.8) |

| المتوسط اليومي °ف (°س) | 54.3 (12.4) |

58.0 (14.4) |

63.8 (17.7) |

70.1 (21.2) |

77.1 (25.1) |

82.4 (28.0) |

83.9 (28.8) |

84.0 (28.9) |

80.8 (27.1) |

72.5 (22.5) |

62.4 (16.9) |

56.6 (13.7) |

70.5 (21.4) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °ف (°س) | 46.1 (7.8) |

49.7 (9.8) |

55.3 (12.9) |

61.7 (16.5) |

69.0 (20.6) |

74.7 (23.7) |

76.5 (24.7) |

76.6 (24.8) |

73.5 (23.1) |

64.3 (17.9) |

53.7 (12.1) |

48.4 (9.1) |

62.5 (16.9) |

| متوسط الدنيا °ف (°س) | 29.5 (−1.4) |

33.4 (0.8) |

38.0 (3.3) |

47.1 (8.4) |

57.3 (14.1) |

67.4 (19.7) |

71.4 (21.9) |

71.1 (21.7) |

63.3 (17.4) |

47.7 (8.7) |

37.7 (3.2) |

32.6 (0.3) |

27.6 (−2.4) |

| الصغرى القياسية °ف (°س) | 14 (−10) |

16 (−9) |

25 (−4) |

32 (0) |

41 (5) |

50 (10) |

60 (16) |

60 (16) |

42 (6) |

35 (2) |

24 (−4) |

11 (−12) |

11 (−12) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار inches (mm) | 5.18 (132) |

4.13 (105) |

4.36 (111) |

5.22 (133) |

5.64 (143) |

7.62 (194) |

6.79 (172) |

6.91 (176) |

5.11 (130) |

3.70 (94) |

3.87 (98) |

4.82 (122) |

63.35 (1٬609) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.5 | 9.0 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 12.7 | 13.9 | 13.6 | 9.8 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 9.2 | 115.1 |

| متوسط الرطوبة النسبية (%) | 75.6 | 73.0 | 72.9 | 73.4 | 74.4 | 76.4 | 79.2 | 79.4 | 77.8 | 74.9 | 77.2 | 76.9 | 75.9 |

| Mean monthly ساعات سطوع الشمس | 153.0 | 161.5 | 219.4 | 251.9 | 278.9 | 274.3 | 257.1 | 251.9 | 228.7 | 242.6 | 171.8 | 157.8 | 2٬648٫9 |

| نسبة السطوع المحتمل للشمس | 47 | 52 | 59 | 65 | 66 | 65 | 60 | 62 | 62 | 68 | 54 | 50 | 60 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[ت][106][107][108] | |||||||||||||

| بيانات المناخ لـ Audubon Park, New Orleans (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °ف (°س) | 84 (29) |

86 (30) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

97 (36) |

92 (33) |

85 (29) |

104 (40) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °ف (°س) | 64.3 (17.9) |

68.4 (20.2) |

74.5 (23.6) |

80.9 (27.2) |

87.9 (31.1) |

92.5 (33.6) |

93.9 (34.4) |

94.0 (34.4) |

90.1 (32.3) |

82.6 (28.1) |

72.9 (22.7) |

66.4 (19.1) |

80.7 (27.1) |

| المتوسط اليومي °ف (°س) | 55.4 (13.0) |

59.4 (15.2) |

65.2 (18.4) |

71.4 (21.9) |

78.6 (25.9) |

83.7 (28.7) |

85.2 (29.6) |

85.5 (29.7) |

81.8 (27.7) |

73.6 (23.1) |

63.7 (17.6) |

57.7 (14.3) |

71.8 (22.1) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °ف (°س) | 46.5 (8.1) |

50.5 (10.3) |

55.8 (13.2) |

62.0 (16.7) |

69.3 (20.7) |

74.9 (23.8) |

76.6 (24.8) |

76.9 (24.9) |

73.6 (23.1) |

64.7 (18.2) |

54.6 (12.6) |

49.0 (9.4) |

62.9 (17.2) |

| الصغرى القياسية °ف (°س) | 13 (−11) |

6 (−14) |

26 (−3) |

32 (0) |

46 (8) |

54 (12) |

61 (16) |

60 (16) |

49 (9) |

35 (2) |

26 (−3) |

12 (−11) |

6 (−14) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار inches (mm) | 4.95 (126) |

4.14 (105) |

4.60 (117) |

4.99 (127) |

5.39 (137) |

7.37 (187) |

8.77 (223) |

6.80 (173) |

5.72 (145) |

3.58 (91) |

3.78 (96) |

4.51 (115) |

64.60 (1٬641) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.8 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 12.6 | 15.1 | 13.3 | 10.0 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 8.8 | 114.5 |

| Source: NOAA[106][109] | |||||||||||||

التهديد من الأعاصير المدارية

الجغرافيا

تقع مدينة نيو أورلينز على ضفاف نهر المسيسيبي في أتجاه مصب خليج المكسيك. وتبعا لتقديرات مكتب التعداد الأمريكي ، فإن المساحة الكلية لمدينة نيو أورلينز تبلغ 350.2 ميل مربع.[110] تقع المدينة على دلتا نهر المسيسيبي في الضفة الغربية من النهر وجنوب بحيرة بونشارترين. وتتميز المساحة على إمتداد النهر بالمنحدرات والتعاريج.

المناخ

| نيو اورلينز | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جدول الطقس (التفسير) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

يتميز مناخ نيو أورليانز بأنه مناخ شبه مداري رطب مع شتاء معتدل قصير و صيف حار رطب. في شهر يناير تصل درجات الحرارة أقل معدلاتها 43 F وفي وسط النهار تصل 62 ف. في شهر يوليو تصل درجات الحرارة إلى 74 ف, وأعلى درجاتها 91 ف. أقل درجة حرارة سجلت في المدينة كانت في 13 فبراير 1899 حيث وصلت 7 ف ، أما أعلى درجة حرارة سجلت فكانت في 22 أغسطس 1980 حيث وصلت 102 F. متوسط كمية هطول الأمطار تصل إلى 6.4 مم سنويا. ويعتبر شهر أكتوبر أكثر شهور السنة جفافا في المدينة.[112]

المنظر العام للمدينة

الطراز المعماري

مقالة مفصلة: المباني والطرز المعمارية في نيو أورلينز

مقالة مفصلة: المباني والطرز المعمارية في نيو أورلينز

السياحة والثقافة

تبعا لدليل السياحة الحالي ، تعتبر نيو أورلينز في قائمة العشر مدن الأكثر زيارة في الولايات المتحدة ، وتعتبر السياحة هي النشاط الرئيسي في إقتصاد المدينة.[113]

الترفيه والفنون المسرحية

الفيلم

الطعام

الرياضة

الإقتصاد

New Orleans operates one of the world's largest and busiest ports and metropolitan New Orleans is a center of maritime industry.[114] The region accounts for a significant portion of the nation's oil refining and petrochemical production, and serves as a white-collar corporate base for onshore and offshore petroleum and natural gas production. Since the beginning of the 21st century, New Orleans has also grown into a technology hub.[115][116]

New Orleans is also a center for higher learning, with over 50,000 students enrolled in the region's eleven two- and four-year degree-granting institutions. Tulane University, a top-50 research university, is located in Uptown. Metropolitan New Orleans is a major regional hub for the health care industry and boasts a small, globally competitive manufacturing sector. The center city possesses a rapidly growing, entrepreneurial creative industries sector and is renowned for its cultural tourism. Greater New Orleans, Inc. (GNO, Inc.)[117] acts as the first point-of-contact for regional economic development, coordinating between Louisiana's Department of Economic Development and the various business development agencies.

Port

New Orleans began as a strategically located trading entrepôt and it remains, above all, a crucial transportation hub and distribution center for waterborne commerce. The Port of New Orleans is the fifth-largest in the United States based on cargo volume, and second-largest in the state after the Port of South Louisiana. It is the twelfth-largest in the U.S. based on cargo value. The Port of South Louisiana, also located in the New Orleans area, is the world's busiest in terms of bulk tonnage. When combined with Port of New Orleans, it forms the 4th-largest port system in volume. Many shipbuilding, shipping, logistics, freight forwarding and commodity brokerage firms either are based in metropolitan New Orleans or maintain a local presence. Examples include Intermarine,[118] Bisso Towboat,[119] Northrop Grumman Ship Systems,[120] Trinity Yachts, Expeditors International,[121] Bollinger Shipyards, IMTT, International Coffee Corp, Boasso America, Transoceanic Shipping, Transportation Consultants Inc., Dupuy Storage & Forwarding and Silocaf.[122] The largest coffee-roasting plant in the world, operated by Folgers, is located in New Orleans East.[123][124]

New Orleans is located near to the Gulf of Mexico and its many oil rigs. Louisiana ranks fifth among states in oil production and eighth in reserves. It has two of the four Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) storage facilities: West Hackberry in Cameron Parish and Bayou Choctaw in Iberville Parish. The area hosts 17 petroleum refineries, with a combined crude oil distillation capacity of nearly 2.8 million barrels per day (450،000 m3/d), the second highest after Texas. Louisiana's numerous ports include the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP), which is capable of receiving the largest oil tankers. Given the quantity of oil imports, Louisiana is home to many major pipelines: Crude Oil (Exxon, Chevron, BP, Texaco, Shell, Scurloch-Permian, Mid-Valley, Calumet, Conoco, Koch Industries, Unocal, U.S. Dept. of Energy, Locap); Product (TEPPCO Partners, Colonial, Plantation, Explorer, Texaco, Collins); and Liquefied Petroleum Gas (Dixie, TEPPCO, Black Lake, Koch, Chevron, Dynegy, Kinder Morgan Energy Partners, Dow Chemical Company, Bridgeline, FMP, Tejas, Texaco, UTP).[125] Several energy companies have regional headquarters in the area, including Royal Dutch Shell, Eni and Chevron. Other energy producers and oilfield services companies are headquartered in the city or region, and the sector supports a large professional services base of specialized engineering and design firms, as well as a term office for the federal government's Minerals Management Service.

Business

The city is the home to a single Fortune 500 company: Entergy, a power generation utility and nuclear power plant operations specialist.[126] After Katrina, the city lost its other Fortune 500 company, Freeport-McMoRan, when it merged its copper and gold exploration unit with an Arizona company and relocated that division to Phoenix. Its McMoRan Exploration affiliate remains headquartered in New Orleans.[127]

Companies with significant operations or headquarters in New Orleans include: Pan American Life Insurance, Pool Corp, Rolls-Royce, Newpark Resources, AT&T, TurboSquid, iSeatz, IBM, Navtech, Superior Energy Services, Textron Marine & Land Systems, McDermott International, Pellerin Milnor, Lockheed Martin, Imperial Trading, Laitram, Harrah's Entertainment, Stewart Enterprises, Edison Chouest Offshore, Zatarain's, Waldemar S. Nelson & Co., Whitney National Bank, Capital One, Tidewater Marine, Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits, Parsons Brinckerhoff, MWH Global, CH2M Hill, Energy Partners Ltd, The Receivables Exchange, GE Capital, and Smoothie King.

Tourist and convention business

Tourism is a staple of the city's economy. Perhaps more visible than any other sector, New Orleans' tourist and convention industry is a $5.5 billion industry that accounts for 40 percent of city tax revenues. In 2004, the hospitality industry employed 85,000 people, making it the city's top economic sector as measured by employment.[128] New Orleans also hosts the World Cultural Economic Forum (WCEF). The forum, held annually at the New Orleans Morial Convention Center, is directed toward promoting cultural and economic development opportunities through the strategic convening of cultural ambassadors and leaders from around the world. The first WCEF took place in October 2008.[129]

Federal and military agencies

Federal agencies and the Armed forces operate significant facilities there. The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals operates at the US. Courthouse downtown. NASA's Michoud Assembly Facility is located in New Orleans East and has multiple tenants including Lockheed Martin and Boeing. It is a huge manufacturing complex that produced the external fuel tanks for the Space Shuttles, the Saturn V first stage, the Integrated Truss Structure of the International Space Station, and is now used for the construction of NASA's Space Launch System. The rocket factory lies within the enormous New Orleans Regional Business Park, also home to the National Finance Center, operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Crescent Crown distribution center. Other large governmental installations include the U.S. Navy's Space and Naval Warfare (SPAWAR) Systems Command, located within the University of New Orleans Research and Technology Park in Gentilly, Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base New Orleans; and the headquarters for the Marine Force Reserves in Federal City in Algiers.

السكان

| التعداد تاريخياً | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| الإحصاء | التعداد | %± | |

| 1810 | 17٬242 | ||

| 1820 | 27٬176 | 57.6% | |

| 1830 | 46٬082 | 69.6% | |

| 1840 | 102٬193 | 121.8% | |

| 1850 | 116٬375 | 13.9% | |

| 1860 | 168٬675 | 44.9% | |

| 1870 | 191٬418 | 13.5% | |

| 1880 | 216٬090 | 12.9% | |

| 1890 | 242٬039 | 12.0% | |

| 1900 | 287٬104 | 18.6% | |

| 1910 | 339٬075 | 18.1% | |

| 1920 | 387٬219 | 14.2% | |

| 1930 | 458٬762 | 18.5% | |

| 1940 | 494٬537 | 7.8% | |

| 1950 | 570٬445 | 15.3% | |

| 1960 | 627٬525 | 10.0% | |

| 1970 | 593٬471 | -5.4% | |

| 1980 | 557٬515 | -6.1% | |

| 1990 | 496٬938 | -10.9% | |

| 2000 | 484٬674 | -2.5% | |

| تقديري 2007 | 239٬124 | [130] | -50.7% |

| Historical Population Figures[131] | |||

الديانة

اللهجة

الحكومة

الجريمة

يوجد معدل عالي لجرائم العنف في مدينة نيو أورلينز. ووصل معدل جرائم القتل إلى ذروته في عام 1994 ، حيث وصل لنسبة 86 من بين 100.000 مواطن.[132]

التعليم

المدارس

الجامعات والكليات

المكتبات

الإعلام

البنية التحتية

النقل

العربات

الحافلات

الطرق

المطارات

خطوط السكك الحديدية

مدن شقيقة

نيو أورلينز لديها علاقات متبادلة مع:[133]

Cap-Haïtien, Haiti[134]

Cap-Haïtien, Haiti[134] Caracas, Venezuela

Caracas, Venezuela Durban, South Africa

Durban, South Africa Innsbruck, Austria

Innsbruck, Austria Isola del Liri, Italy

Isola del Liri, Italy Juan-les-Pins (Antibes), France

Juan-les-Pins (Antibes), France Maracaibo, Venezuela

Maracaibo, Venezuela Matsue, Japan

Matsue, Japan Mérida, Mexico

Mérida, Mexico Orléans, France

Orléans, France Pointe-Noire, Republic of the Congo

Pointe-Noire, Republic of the Congo San Miguel de Tucumán، الأرجنتين

San Miguel de Tucumán، الأرجنتين Tainan، تايوان

Tainan، تايوان Tegucigalpa، هندوراس

Tegucigalpa، هندوراس

انظر أيضا

- Buildings and architecture of New Orleans

- Cancer Alley

- The Cabildo

- French Quarter Festival

- Île d'Orléans, Louisiana

- List of people from New Orleans

- Mississippi (River) Suite, with an orchestral portrayal of Mardi Gras

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Orleans Parish, Louisiana

- Neighborhoods in New Orleans

- New Orleans in fiction

- New Orleans Suite, Duke Ellington recording

- New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal

- New Orleans Public Schools

- Pontalba Buildings

- The Presbytere

- Southern Food and Beverage Museum

- يوإسإس New Orleans, 5 ships

- يوإسإس Orleans Parish

Notes

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Official records for New Orleans have been kept at MSY since May 1, 1946.[105] Additional records from Audubon Park dating back to 1893 have also been included.

- ^ Sunshine normals are based on only 20 to 22 years of data.

المراجع

- ^ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ "U.S. Population Totals 2010–2020". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "List of 2020 Census Urban Areas". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for New Orleans-Metairie, LA (MSA)". fred.stlouisfed.org. Archived from the original on January 4, 2024. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product by County and Metropolitan Area, 2022" (PDF). www.bea.gov. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 13, 2023. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ^ New Orleans Archived مارس 6, 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Romer, Megan. "How to Say 'New Orleans' Correctly". About Travel. about.com. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ "QuickFacts: New Orleans city, Louisiana". United States Census Bureau. August 10, 2021. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ Henry Louis Mencken (1924). The American Language: An Inquiry Into the Development of English in the United States. A. A. Knopf. p. 412.

- ^ Institute of New Orleans History and Culture Archived ديسمبر 7, 2006 at the Wayback Machine at Gwynedd-Mercy College

- ^ "Hurricane on the Bayou – A MacGillivray Freeman Film". Hurricane on the Bayou. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016.

- ^ David Billings, "New Orleans: A Choice Between Destruction and Reparations", The Fellowship of Reconciliation, November/December 2005

- ^ Damian Dovarganes, Associated Press, "Spike Lee offers his take on Hurricane Katrina" Archived سبتمبر 17, 2022 at the Wayback Machine, MSNBC, July 14, 2006

- ^ "The Founding French Fathers". Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- ^ "Hollywood South: Why New Orleans Is the New Movie-Making Capital". ABC News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ "Hollywood South: Film Production and Movie Going in New Orleans". New Orleans Historical (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ "Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1840". United States Census Bureau. 1998. Archived from the original on February 14, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ "About the Orleans Levee District". Orleans Levee. Archived from the original on June 25, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ Jervis, Rick. "Fifteen years and $15 billion since Katrina, New Orleans is more prepared for a major hurricane – for now". USA TODAY (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ^ "Report: New Orleans Three Years After the Storm: The Second Kaiser Post-Katrina Survey, 2008". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). August 1, 2008. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ "Is Post-Katrina Gentrification Saving New Orleans Or Ruining It?". BuzzFeed (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ Elie, Lolis (2019-08-27). "Opinion | Gentrification Might Kill New Orleans Before Climate Change Does". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ "Gentrification a Growing Threat for Many New Orleans Residents". Louisiana Fair Housing Action Center. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ Kinniburgh, Colin (2017-08-09). "How to Stop Gentrification". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ Schirm, Cassie (2023-01-04). "'It has been a horrific year': New Orleans' 2022 was a violent year, what analysts say we can learn from it for 2023". WDSU (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-20.

- ^ Robin, Natasha (2022-09-19). "New Orleans tops the nation for homicides per capita". www.fox8live.com (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on August 20, 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-20.

- ^ "Orleans Parish History and Information". Archived from the original on May 15, 2005. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ "Quick Facts – Louisiana Population Estimates". US Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ "2020 Population and Housing State Data". The United States Census Bureau (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-18.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ أ ب "French History in New Orleans". www.neworleans.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ "History of New Orleans". www.neworleans.com. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- ^ "New Orleans Nicknames". New Orleans Convention & Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on January 7, 2009. Retrieved December 2, 2008.

- ^ "Why Is New Orleans Called "The Big Easy?"". Southern Living (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ أ ب "What do you call New Orleans? 11 of the good, bad and silly nicknames for an iconic city". NOLA.com (in الإنجليزية). October 3, 2017. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ Ingersoll, Steve (March 2004). "New Orleans—"The City That Care Forgot" and Other Nicknames A Preliminary Investigation". New Orleans Public Library. Archived from the original on September 20, 2004. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ "VERIFY: Does New Orleans have an actual birthday?". WWL. December 15, 2017. Archived from the original on June 30, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ Ding, Loni (2001). "Part 1. Coolies, Sailors and Settlers". NAATA. PBS. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

Some of the Filipinos who left their ships in Mexico ultimately found their way to the bayous of Louisiana, where they settled in the 1760s. The film shows the remains of Filipino shrimping villages in Louisiana, where, eight to ten generations later, their descendants still reside, making them the oldest continuous settlement of Asians in America.

Ding, Loni (2001). "1763 Filipinos in Louisiana". NAATA. PBS. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2011.These are the "Louisiana Manila men" with presence recorded as early as 1763.

Westbrook, Laura (2008). "Mabuhay Pilipino! (Long Life!): Filipino Culture in Southeast Louisiana". Louisiana Folklife Program. Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation & Tourism. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

Fabros, Alex S. Jr. (February 1995). "When Hilario Met Sally: The Fight Against Anti-Miscegenation Laws". Filipinas Magazine. Burlingame, California: Positively Filipino LLC. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2018 – via Positively Filipino.

Mercene, Floro L. (2007). Manila Men in the New World: Filipino Migration to Mexico and the Americas from the Sixteenth Century. UP Press. pp. 106–08. ISBN 978-971-542-529-2. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved September 19, 2018. - ^ Mitchell, Barbara (Autumn 2010). "America's Spanish Savior: Bernardo de Gálvez marches to rescue the colonies". MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History: 98–104. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ José Presas y Marull (1828). Juicio imparcial sobre las principales causas de la revolución de la América Española y acerca de las poderosas razones que tiene la metrópoli para reconocer su absoluta independencia. (original document) [Fair judgment about the main causes of the revolution of Spanish America and about the powerful reasons that the metropolis has for recognizing its absolute independence]. Burdeaux: Imprenta de D. Pedro Beaume. pp. 22, 23. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ "National Park Service. Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. Ursuline Convent". Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ "Slave Resistance in Natchez, Mississippi (1719–1861) | Mississippi History Now". mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ Gayarré, Charles (1854). History of Louisiana: The French Domination. Vol. 1. New York, New York: Redfield. pp. 447–450. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ^ Gayarré 1854.

- ^ Cummins, Light Townsend; Kheher Schafer, Judith; Haas, Edward F.; Kurtz, Micahel L. (2014). Wall, Bennett H.; Rodrigue, John C. (eds.). Louisiana: A History (6th ed.). Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley Blackwell. p. 59. ISBN 9781118619292. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ BlackPast (2007-07-28). "(1724) Louisiana's Code Noir" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ "From Benin to Bourbon Street: A Brief History of Louisiana Voodoo". www.vice.com (in الإنجليزية). October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ "The True History and Faith Behind Voodoo". FrenchQuarter.com (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ Cruzat, Heloise Hulse (1919). "The Ursulines of Louisiana". The Louisiana Historical Quarterly. 2 (1). Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ "Pauger's Savvy Move" (PDF). richcampanella.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Cummins et al. 2014.

- ^ "The Louisiana Purchase". Monticello (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ Lachance, Paul F. (1988). "The 1809 Immigration of Saint-Domingue Refugees to New Orleans: Reception, Integration and Impact". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 29 (2): 110. JSTOR 4232650.

- ^ Brasseaux, Carl A.; Conrad, Glenn R., eds. (2016). The Road to Louisiana: The Saint-Domingue Refugees 1792–1809. Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press. ISBN 9781935754602. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ^ أ ب "Haitian Immigration: 18th & 19th Centuries" Archived يونيو 12, 2018 at the Wayback Machine, In Motion: African American Migration Experience, New York Public Library, accessed May 7, 2008

- ^ Gitlin 2009, p. 54.

- ^ Tom (March 18, 2015). "Rare 1815 Plan of the City and Suburbs of New Orleans". Cool Old Photos (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ أ ب Groom, Winston (2007). Patriotic Fire: Andrew Jackson and Jean Laffite at the Battle of New Orleans. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-9566-7. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ "New Orleans: The Birthplace of Jazz" (primarily excerpted from Jazz: A History of America's Music). PBS – JAZZ A Film By Ken Burns. Archived from the original on August 12, 2006. Retrieved May 17, 2006.

- ^ "History of Les Gens De Couleur Libres". Archived from the original on May 22, 2006. Retrieved May 17, 2006.

- ^ Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999, pp. 2, 6

- ^ Gitlin 2009, p. 159.

- ^ Lewis, Peirce F., New Orleans: The Making of an Urban Landscape, Santa Fe, 2003, p. 175

- ^ أ ب Lawrence J. Kotlikoff and Anton J. Rupert, "The Manumission of Slaves in New Orleans, 1827–1846" Archived أبريل 8, 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Southern Studies, Summer 1980

- ^ أ ب Gitlin 2009, p. 166.

- ^ "How Yellow Fever Turned New Orleans Into The 'City Of The Dead'". NPR. October 31, 2018. Archived from the original on June 28, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ "A lesson from history: How the yellow fever epidemic changed society". Palo Alto Weekly. May 10, 2020. Archived from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Nystrom, Justin A. (2010). New Orleans after the Civil War: Race, Politics, and a New Birth of Freedom. JHU Press. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-8018-9997-3.

- ^ "Benjamin Butler". 64 Parishes (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ Gitlin 2009, p. 180.

- ^ Leslie's Weekly, December 11, 1902

- ^ Robert Tallant & Lyle Saxon, Gumbo Ya-Ya: Folk Tales of Louisiana, Louisiana Library Commission: 1945, p. 178

- ^ Brasseaux, Carl A. (2005). French, Cajun, Creole, Houma: A Primer on Francophone Louisiana. LSU Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8071-3036-0. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ New Orleans City Guide. The Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration: 1938, p. 90

- ^ "Usticesi in the United States Civil War". The Ustica Connection. March 22, 2003. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 2: From the Founding of the American Federation of Labor to the Emergence of American Imperialism, 1955, p. 203.

- ^ Cook, "The Typographical Union and the New Orleans General Strike of 1892," Louisiana History, 1983; "Labor Trouble In New-Orleans," New York Times, November 5, 1892.

- ^ "Immigration / Italian". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ Gambino, Richard (2000). Vendetta: The True Story of the Largest Lynching in U.S. History. Guernica Editions. ISBN 978-1-55071-103-5. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ أ ب ت Lewis, Peirce F., New Orleans: The Making of an Urban Landscape, Santa Fe, 2003, p. 175.

- ^ "July 1, 1929: Streetcar Workers Strike in New Orleans". Zinn Education Project. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ Mizell-Nelson, Michael. "1929 Streetcar Strike - Stop 4 of 9 in the Streetcars and their Historian Michael Mizell-Nelson tour". New Orleans Historical (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ Mizell-Nelson, Michael. "Po-Boy Sandwich - Stop 6 of 7 in the French Quarter Street Food tour". New Orleans Historical (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ^ Sell, Jack (December 30, 1955). "Panthers defeat flu; face Ga. Tech next". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Mulé, Marty – A Time For Change: Bobby Grier And The 1956 Sugar Bowl Archived 2007-06-10 at the Wayback Machine. Black Athlete Sports Network, December 28, 2005

- ^ Zeise, Paul – Bobby Grier broke bowl's color line. The Panthers' Bobby Grier was the first African-American to play in Sugar Bowl Archived مارس 9, 2012 at the Wayback Machine Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 07, 2005

- ^ Thamel, Pete – Grier Integrated a Game and Earned the World's Respect Archived يناير 2, 2015 at the Wayback Machine. New York Times, January 1, 2006.

- ^ Jake Grantl (2019-11-14). "Rearview Revisited: Segregation and the Sugar Bowl". Georgia Tech. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- ^ Germany, Kent B., New Orleans After the Promises: Poverty, Citizenship and the Search for the Great Society, Athens, 2007, pp. 3–5

- ^ أ ب Glassman, James K., "New Orleans: I have Seen the Future, and It's Houston", The Atlantic Monthly, July 1978

- ^ Kusky, Timothy M. (December 29, 2005). "Why is New Orleans Sinking?" (PDF). Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Saint Louis University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 23, 2006. Retrieved June 17, 2006.

- ^ O'Hanlon, Larry (March 31, 2006). "New Orleans Sits Atop Giant Landslide". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved June 17, 2006.

- ^ Marshall, Bob (2005-11-30). "17th Street Canal levee was doomed". Times-Picayune. Retrieved 2006-03-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Deaths of evacuees push toll to 1,577". nola.com. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ^ "Mayor: Parts of New Orleans to reopen". CNN.com. September 15 2005. Retrieved 2006-05-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ^ "New Study Maps Rate of New Orleans Sinking". NASA. May 16, 2016. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Campanella, R. Above-Sea-Level New Orleans Archived مارس 4, 2016 at the Wayback Machine April 2007.

- ^ Williams, L. Higher Ground Archived أغسطس 19, 2017 at the Wayback Machine A study finds that New Orleans has plenty of real estate above sea level that is being underutilized. The Times Picayune, April 21, 2007.

- ^ Schlotzhauer, David; Lincoln, W. Scott (2016). "Using New Orleans Pumping Data to Reconcile Gauge Observations of Isolated Extreme Rainfall due to Hurricane Isaac". Journal of Hydrologic Engineering. 21 (9): 05016020. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0001338.

- ^ Strecker, M. (July 24, 2006). "A New Look at Subsidence Issues".[dead link]

- ^ أ ب The New Orleans Hurricane Protection System: What Went Wrong and Why. Archived يوليو 2, 2007 at the Wayback Machine Report by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

- ^ "New Study Maps Rate of New Orleans Sinking". May 16, 2016. Archived from the original on June 8, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ Brock, Eric J. New Orleans, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, South Carolina (1999), pp. 108–09.

- ^ "Threaded Extremes". threadex.rcc-acis.org. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ أ ب "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ "Station: New Orleans INTL AP, LA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on December 4, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for NEW ORLEANS, LA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ^ "Station: New Orleans Audubon, LA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ "United States Summary: 2000" (pdf). United States Census Bureau. 2004-04-01. p. 165. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ Monthly Averages for New Orleans. Weather.com

- ^ "Monthly Averages for New Orleans, LA". Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- ^ Overseas visitors to select U.S. cities/Hawaiian Islands 2001 - 2000. U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Travel and Tourism Industries. Retrieved November 12, 2007.