لداخ

لداخ

Ladakh | |

|---|---|

منطقة تديرها الهند كإقليم اتحادي[1] | |

لداخ (باللون القرمزي) كما تبدو في خريطة الجزء الذي تسيطر عليه الهند من كشمير | |

موقع مقر ادارة المقاطعة، له | |

| الإحداثيات: 34°10′12″N 77°34′48″E / 34.17000°N 77.58000°E | |

| البلد | India |

| الولاية | جمو وكشمير |

| Union territory | 31 October 2019[2] |

| العواصم | له،[3] Kargil[4] |

| الأضلع | 2 |

| الحكومة | |

| • الكيان | إدارة لداخ |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Radha Krishna Mathur |

| • Member of Parliament | Jamyang Tsering Namgyal (BJP) |

| • High Court | High Court of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 59٬146 كم² (22٬836 ميل²) |

| أعلى منسوب | 7٬742 m (25٬400 ft) |

| أوطى منسوب | 2٬550 m (8٬370 ft) |

| التعداد (2011) | |

| • الإجمالي | 274٬289 |

| • الكثافة | 4٫6/km2 (12/sq mi) |

| صفة المواطن | Ladakhi |

| اللغات | |

| • الرسمية | لداخي التبتية كشميري اوردو بلتي |

| • المحكية | لداخي، Purgi و بلتي |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-LA |

| لوحة السيارة | LA[7] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | ladakh |

لداخ (إنگليزية: Ladakh؛ ləˈdɑ:k) (التبتية: ལ་དྭགས, وايلي: La-dwags، لداخي [lad̪ɑks]، أردو: لدّاخ [ləd̪ˈd̪aːx]; "أرض الممرات") هي منطقة تسيطر عليها الهند في ولاية جامو وكشمير التي تقع بين سلسلة جبال كونلون إلى الشمال والهيمالايا العظمى الرئيسية إلى الجنوب، يسكنها شعوب من أصل هندي-آري وتبتي.[8] وهي أحد أقل المناطق سكاناً في جمو وكشمير.

"لداخ هي التهجي الفارسي للكلمة التبتية لا-دڤاگس، يؤكده نطق الكلمة في العديد من المقاطعات التبتية."[9]

تاريخياً، ضمت المنطقة وديان بلتستان (بلتييول)، وادي السند، زانگسكار، لاهاول و سپيتي النائين إلى الجنوب، أكساي تشين و نگاري، بما فيها منطقة رودوك وگوگه، في الشرق، ووديان نوبرا إلى الشمال.

لداخ الحالية تحد التبت إلى الشرق، لاهاول و سپيتي إلى الجنوب، وادي كشمير، جامو ومناطق بلتييول إلى الغرب، وعبر كونلون أرض شينجيانگ إلى أقصى الشمال. وتشتهر لداخ بجمال جبالها البعيدة وثقافتها. وتُسمى أحياناً "التبت الصغيرة" لتأثرها الشديد بالثقافة التبتية.

في الماضي، حظت لداخ بأهمية من موقعها الاستراتيجي على مفترق طرق تجارة هامة،[10] ولكن منذ أن أغلقت السلطات الصينية حدود التبت وآسيا الوسطى في عقد 1960، فقد اضمحلت التجارة الدولية إلا السياحة. ومنذ 1974، شجعت حكومة الهند بنجاح السياحة في لداخ. ولما كانت لداخ جزءاً من جامو وكشمير المهمة استراتيجياً، فإن عسكرية الهند تحافظ على وجود مكثف في المنطقة، بسبب نزاعي الهند على المنطقة مع پاكستان والصين.

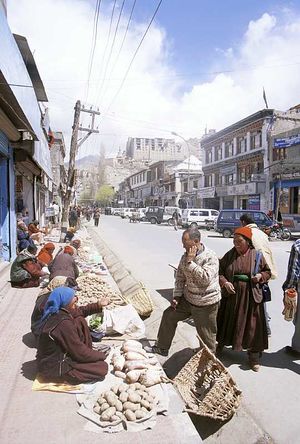

أكبر بلدة في لداخ هي له. وهي أحد معاقل قليلة باقية للبوذية في جنوب آسيا، بما فيها مدقات ربوة چيتاگونگ، بهوتان وسري لانكا؛ معظم اللداخ هم من أتباع البوذية التبتية وبالبقية معظمهم من المسلمين الشيعة.[11]مدينة له تليها كارگيل كثاني أكبر بلدة في لداخ.[12] بعض الناشطين اللداخ طالبوا بأن تصبح لداخ أرض اتحادية بسبب اختلافها دينياً وثقافياً عن كشمير ذات الأغلبية المسلمة.[13][14] The Leh district contains the Indus, Shyok and Nubra river valleys. The Kargil district contains the Suru, Dras and Zanskar river valleys. The main populated regions are the river valleys, but the mountain slopes also support the pastoral Changpa nomads. The main religious groups in the region are Muslims (mainly Shia) (46%), Buddhists (mainly Tibetan Buddhists) (40%), Hindus (12%) and others (2%).[15][11] Ladakh is one of the most sparsely populated regions in India. Its culture and history are closely related to that of Tibet.[16]

Ladakh was established as a union territory of India on 31 October 2019, following the passage of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act. Prior to that, it was part of the Jammu and Kashmir state. Ladakh is the largest and the second least populous union territory of India.[بحاجة لمصدر]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأسماء

The classical name التبتية: ལ་དྭགས, وايلي: La dwags means the "land of high passes". Ladak is its pronunciation in several Tibetan dialects. The English spelling Ladakh is derived from فارسية: ladāx.[17][18]

The region was previously known as Maryul.

Medieval Islamic scholars called Ladakh the Great Tibet (derived from Turko-Arabic Ti-bat, meaning "highland"); Baltistan and other trans-Himalayan states in Kashmir's vicinity were referred to as "Little Tibets".[19][20][ب]

التاريخ

التاريخ القديم

Rock carvings found in many parts of Ladakh indicate that the area has been inhabited from Neolithic times.[14] Ladakh's earliest inhabitants consisted of nomads known as Kampa.[22] Later settlements were established by Mons from Kullu and Brokpas who originated from Gilgit.[23] Around the 1st century, Ladakh was a part of the Kushan Empire. Buddhism spread into western Ladakh from Kashmir in the 2nd century. The 7th-century Buddhist traveller Xuanzang describes the region in his accounts.[24] Xuanzang's term of Ladakh is Mo-lo-so, which has been reconstructed by academics as *Malasa, *Marāsa, or *Mrāsa, which is believed to have been the original name of the region.[25][26]

For much of the first millennium, the western Tibet comprised Zhangzhung kingdom(s), which practised the Bon religion. Sandwiched between Kashmir and Zhangzhung, Ladakh is believed to have been alternatively under the control of one or other of these powers. Academics find strong influences of Zhangzhung language and culture in "upper Ladakh" (from the middle section of the Indus valley to the southeast).[27] The penultimate king of Zhangzhung is said to have been from Ladakh.[28]

From around 660 CE, Central Tibet and China started contesting the "four garrisons" of the Tarim Basin (present day Xinjiang), a struggle that lasted three centuries. Zhangzhung fell victim to Tibet's ambitions in ح. 634 and disappeared for ever. Kashmir's Karkota Empire and the Umayyad Caliphate too joined the contest for Xinjiang soon afterwards. Baltistan and Ladakh were at the centre of these struggles.[29] Academics infer from the slant of Ladakhi chronicles that Ladakh may have owed its primary allegiance to Tibet during this time, but that it was more political than cultural. Ladakh remained Buddhist and its culture was not yet Tibetan.[30]

مطلع العصور الوسطى

In the 9th century, Tibet's ruler Langdarma was assassinated and Tibet fragmented. Kyide Nyimagon, Langdarma's great-grandson, fled to West Tibet ح. 900 CE, and founded a new West Tibetan kingdom at the heart of the old Zhangzhung, now called Ngari in the Tibetan language.

Nyimagon's eldest son, Lhachen Palgyigon, is believed to have conquered the regions to the north, including Ladakh and Rutog. After the death of Nyimagon, his kingdom was divided among his three sons, Palgyigon receiving Ladakh, Rutog, Thok Jalung and an area referred to as Demchok Karpo (a holy mountain near the present day Demchok village). The second son received Guge–Purang (called "Ngari Korsum") and the third son received Zanskar and Spiti (to the southwest of Ladakh). This three-way division of Nyimagon's empire was recognised as historic and remembered in the chronicles of all the three regions as a founding narrative.

He gave to each of his sons a separate kingdom, viz., to the eldest Dpal-gyi-gon, Maryul of Mngah-ris, the inhabitants using black bows; ru-thogs [Rutog] of the east and the Gold-mine of Hgog [possibly Thok Jalung]; nearer this way Lde-mchog-dkar-po [Demchok Karpo]; ...

The first West Tibetan dynasty of Maryul founded by Palgyigon lasted five centuries, being weakened towards its end by the conquests of the Mongol/Mughal noble Mirza Haidar Dughlat. Throughout this period the region was called "Maryul", possibly from the original proper name *Mrasa (Xuangzhang's, Mo-lo-so), but in the Tibetan language it was interpreted to mean "lowland" (the lowland of Ngari). Maryul remained staunchly Buddhist during this period, having participated in the second diffusion of Buddhism from India to Tibet via Kashmir and Zanskar.

Ladakh horsemen, depicted in Alchi Monastery, circa 13th century CE

The nine stupas at Thiksey Monastery

Statue of Maitreya at Likir Monastery, Leh district

تاريخ العصور الوسطى

Between the 1380s and early 1510s, many Islamic missionaries propagated Islam and proselytised the Ladakhi people. Sayyid Ali Hamadani, Sayyid Muhammad Nur Baksh and Mir Shamsuddin Iraqi were three important Sufi missionaries who propagated Islam to the locals. Mir Sayyid Ali was the first one to make Muslim converts in Ladakh and is often described as the founder of Islam in Ladakh. Several mosques were built in Ladakh during this period, including in Mulbhe, Padum and Shey, the capital of Ladakh.[32][33] His principal disciple, Sayyid Muhammad Nur Baksh also propagated Islam to Ladakhis and the Balti people rapidly converted to Islam. Noorbakshia Islam is named after him and his followers are only found in Baltistan and Ladakh. During his youth, Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin expelled the mystic Sheikh Zain Shahwalli for showing disrespect to him. The sheikh then went to Ladakh and proselytised many people to Islam. In 1505, Shamsuddin Iraqi, a noted Shia scholar, visited Kashmir and Baltistan. He helped in spreading Shia Islam in Kashmir and converted the overwhelming majority of Muslims in Baltistan to his school of thought.[33]

It is unclear what happened to Islam after this period and it seems to have received a setback. Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat who invaded and briefly conquered Ladakh in 1532, 1545 and 1548, does not record any presence of Islam in Leh during his invasion although Shia Islam and Noorbakshia Islam continued to flourish in other regions of Ladakh.[32][33]

King Bhagan reunited and strengthened Ladakh and founded the Namgyal dynasty (Namgyal means "victorious" in several Tibetan languages). The Namgyals repelled most Central Asian raiders and temporarily extended the kingdom as far as Nepal.[14] During the Balti invasion led by Raja Ali Sher Khan Anchan, many Buddhist temples and artefacts were damaged. Ali Sher Khan took the king and his soldiers as captives. Jamyang Namgyal was later restored to the throne by Ali Sher Khan and given the hand of a Muslim princess in marriage. Her name was Gyal Khatun or Argyal Khatoom. She was to be the first queen and her son was to become the next ruler. Historical accounts differ upon who her father was. Some identify Ali's ally and Raja of Khaplu Yabgo Shey Gilazi as her father, while others identify Ali himself as the father.[34][35][36][37][38][39] In the early 17th century efforts were made to restore the destroyed artefacts and gonpas by Sengge Namgyal, the son of Jamyang and Gyal. He expanded the kingdom into Zangskar and Spiti. Despite a defeat of Ladakh by the Mughals, who had already annexed Kashmir and Baltistan, Ladakh retained its independence.

Islam begins to take root in the Leh area in the beginning of the 17th century after the Balti invasion and the marriage of Gyal to Jamyang. A large group of Muslim servants and musicians were sent along with Gyal to Ladakh and private mosques were built where they could pray. The Muslim musicians later settled in Leh. Several hundred Baltis migrated to the kingdom and according to oral tradition many Muslim traders were granted land to settle. Many other Muslims were invited over the following years for various purposes.[40]

In the late 17th century, Ladakh sided with Bhutan in its dispute with Tibet which, among other reasons, resulted in its invasion by the Tibetan Central Government. This event is known as the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal war of 1679–1684.[41] Kashmiri historians assert that the king converted to Islam in return for the assistance by Mughal Empire after this, however, Ladakhi chronicles do not mention such a thing. The king agreed to pay tribute to the Mughals in return for defending the kingdom.[42][43] The Mughals, however, withdrew after being paid off by the 5th Dalai Lama.[44] With the help of reinforcements from Galdan Boshugtu Khan, Khan of the Zungar Empire, the Tibetans attacked again in 1684. The Tibetans were victorious and concluded a treaty with Ladakh then they retreated back to Lhasa in December 1684. The Treaty of Tingmosgang in 1684 settled the dispute between Tibet and Ladakh but severely restricted Ladakh's independence.

Likir Monastery, Ladakh

Phyang Gompa, Ladakh

Hemis Monastery in the 1870s

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

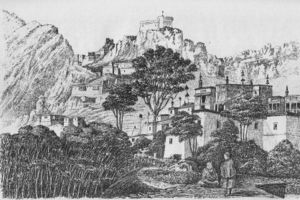

ولاية جمو وكشمير الأميرية

In 1834, the Sikh Zorawar Singh, a general of Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu, invaded and annexed Ladakh to Jammu under the suzerainty of the Sikh Empire. After the defeat of the Sikhs in the First Anglo-Sikh War, the state of Jammu and Kashmir was established as a separate princely state under British suzerainty. The Namgyal family was given the jagir of Stok, which it nominally retains to this day. European influence began in Ladakh in the 1850s and increased. Geologists, sportsmen, and tourists began exploring Ladakh. In 1885, Leh became the headquarters of a mission of the Moravian Church.

Ladakh was administered as a wazarat during the Dogra rule, with a governor termed wazir-e-wazarat. It had three tehsils, based at Leh, Skardu and Kargil. The headquarters of the wazarat was at Leh for six months of the year and at Skardu for six months. When the legislative assembly called Praja Sabha was established in 1934, Ladakh was given two nominated seats in the assembly.

Ladakh was claimed as part of Tibet by Phuntsok Wangyal, a Tibetan Communist leader.[45]

ولاية جمو وكشمير الهندية

At the time of the partition of India in 1947, the Dogra ruler Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession to India. Pakistani raiders from Gilgit had reached Ladakh and military operations were initiated to evict them. The wartime conversion of the pony trail from Sonamarg to Zoji La by army engineers permitted tanks to move up and successfully capture the pass. The advance continued. Dras, Kargil and Leh were liberated and Ladakh cleared of the infiltrators.[46]

In 1949, China closed the border between Nubra and Xinjiang, blocking old trade routes. In 1955 China began to build roads connecting Xinjiang and Tibet through the Aksai Chin area. The Indian effort to retain control of Aksai Chin led to the Sino-Indian War of 1962, which India lost. China also built the Karakoram highway jointly with Pakistan. India built the Srinagar-Leh Highway during this period, cutting the journey time between Srinagar and Leh from 16 days to two. The route, however, remains closed during the winter months due to heavy snowfall. Construction of a 6.5 km (4.0 mi) tunnel across Zoji La pass is under consideration to make the route functional throughout the year.[14][47]

The Kargil War of 1999, codenamed "Operation Vijay" by the Indian Army, saw infiltration by Pakistani troops into parts of Western Ladakh, namely Kargil, Dras, Mushkoh, Batalik and Chorbatla, overlooking key locations on the Srinagar-Leh highway. Extensive operations were launched in high altitudes by the Indian Army with considerable artillery and air force support. Pakistani troops were evicted from the Indian side of the Line of Control which the Indian government ordered was to be respected and which was not crossed by Indian troops. The Indian government was criticised by the Indian public because India respected geographical co-ordinates more than India's opponents: Pakistan and China.[48][صفحة مطلوبة]

The Ladakh region was divided into the Kargil and Leh districts in 1979. In 1989, there were violent riots between Buddhists and Muslims. Following demands for autonomy from the Kashmiri-dominated state government, the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council was created in the 1990s. Leh and Kargil districts now each have their own locally elected Hill Councils with some control over local policy and development funds. In 1991, a Peace Pagoda was erected in Leh by Nipponzan Myohoji.

There was a heavy presence of Indian Army and Indo-Tibetan Border Police forces in Ladakh. These forces and People's Liberation Army forces from China have, since the 1962 Sino-Indian War, had frequent stand-offs along the Lakakh portion of the Line of Actual Control. Out of the 857-kilometre-long (533 mi) border in Ladakh, only 368 km (229 mi) is the International Border, and the remaining 489 km (304 mi) is the Line of Actual Control.[49][50] The stand-off involving the most troops was in September 2014 in the disputed Chumar region when 800 to 1,000 Indian troops and 1,500 Chinese troops came into close proximity to each other.[51]

قسم لداخ

On 8 February 2019, Ladakh became a separate Revenue and Administrative Division within Jammu and Kashmir, having previously been part of the Kashmir Division. As a division, Ladakh was granted its own Divisional Commissioner and Inspector General of Police.[52]

Leh was initially chosen to be the headquarters of the new division however, following protests, it was announced that Leh and Kargil will jointly serve as the divisional headquarters, each hosting an Additional Divisional Commissioner to assist the Divisional Commissioner and Inspector General of Police who will spend half their time in each town.[53]

إقليم لداخ الاتحادي

The people of Ladakh had been demanding Ladakh to be constituted as a separate territory since 1930s, because of perceived unfair treatment by Kashmir and Ladakh's cultural differences with predominantly Muslim Kashmir valley, while some people in Kargil opposed union territory status for Ladakh.[14][13] The first organized agitation was launched against Kashmir's "dominance" in the year 1964. In late 1980s, a much larger mass agitation was launched to press their demand for union territory status.[54]

In August 2019, a reorganisation act was passed by the Parliament of India which contained provisions to reconstitute Ladakh as a union territory, separate from the rest of Jammu and Kashmir on 31 October 2019.[2][55][56][57] Under the terms of the act, the union territory is administered by a Lieutenant Governor acting on behalf of the Central Government of India and does not have an elected legislative assembly or chief minister. Each district within the union territory continues to elect an autonomous district council as done previously.[58]

The demand for Ladakh as separate union territory was first raised by the parliamentarian Kushok Bakula Rinpoche around 1955, which was later carried forward by another parliamentarian Thupstan Chhewang.[59] The former Jammu and Kashmir state use to obtain large allocation of annual funds from the union government based on the fact that the large geographical area of the Ladakh (comprising 65% of total area), but Ladakh was allocated only 2% of the state budget based on its relative population.[59] Within the first year of the formation of Ladakh as separate union territory, its annual budget allocation has increased 4 times from ₹57 crore to ₹232 crore.[59]

الجغرافيا

لداخ هي أعلى هضبة في ولاية كشمير، إذ يقع معظمها فوق ارتفاع 3,000 م.[11] وهي تغطي سلسلتي جبال الهيمالايا وقرةقورم وأعالي وادي نهر السند.[60] Ranges and includes the upper Indus River valley.

Historically, the region included the Baltistan (Baltiyul) valleys (now mostly in Pakistani administered part of Kashmir), the entire upper Indus Valley, the remote Zanskar, Lahaul and Spiti to the south, much of Ngari including the Rudok region and Guge in the east, Aksai Chin in the northeast, and the Nubra Valley to the north over Khardong La in the Ladakh Range. Contemporary Ladakh borders Tibet to the east, the Lahaul and Spiti regions to the south, the Vale of Kashmir, Jammu and Baltiyul regions to the west, and the southwest corner of Xinjiang across the Karakoram Pass in the far north. The historic but imprecise divide between Ladakh and the Tibetan Plateau commences in the north in the intricate maze of ridges east of Rudok including Aling Kangri and Mavang Kangri, and continues southeastward toward northwestern Nepal. Before partition, Baltistan, now under Pakistani control, was a district in Ladakh. Skardu was the winter capital of Ladakh while Leh was the summer capital.

The mountain ranges in this region were formed over 45 million years by the folding of the Indian Plate into the more stationary Eurasian Plate. The drift continues, causing frequent earthquakes in the Himalayan region.[ت][61] The peaks in the Ladakh Range are at a medium altitude close to the Zoji-la (5,000–5,500 m or 16,400–18,000 ft) and increase toward southeast, culminating in the twin summits of Nun-Kun (7,000 m or 23,000 ft).

The Suru and Zanskar valleys form a great trough enclosed by the Himalayas and the Zanskar Range. Rangdum is the highest inhabited region in the Suru valley, after which the valley rises to 4,400 m (14,400 ft) at Pensi-la, the gateway to Zanskar. Kargil, the only town in the Suru valley, is the second most important town in Ladakh. It was an important staging post on the routes of the trade caravans before 1947, being more or less equidistant, at about 230 kilometres from Srinagar, Leh, Skardu and Padum. The Zangskar valley lies in the troughs of the Stod and the Lungnak rivers. The region experiences heavy snowfall; the Pensi-la is open only between June and mid-October. Dras and the Mushkoh Valley form the western extremity of Ladakh.

The Indus River is the backbone of Ladakh. Most major historical and current towns – Shey, Leh, Basgo and Tingmosgang (but not Kargil), are close to the Indus River. After the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, the stretch of the Indus flowing through Ladakh became the only part of this river, which is greatly venerated in the Hindu religion and culture, that still flows through India.

The Siachen Glacier is in the eastern Karakoram Range in the Himalaya Mountains along the disputed India-Pakistan border. The Karakoram Range forms a great watershed that separates China from the Indian subcontinent and is sometimes called the "Third Pole." The glacier lies between the Saltoro Ridge immediately to the west and the main Karakoram Range to the east. At 76 km (47 mi) long, it is the longest glacier in the Karakoram and second-longest in the world's non-polar areas. It falls from an altitude of 5,753 m (18,875 ft) above sea level at its source at Indira Col on the China border down to 3,620 m (11,880 ft) at its snout. Saser Kangri is the highest peak in the Saser Muztagh, the easternmost subrange of the Karakoram Range in India, Saser Kangri I having an altitude of 7,672 m (25,171 ft).

The Ladakh Range has no major peaks; its average height is a little less than 6,000 m (20,000 ft), and few of its passes are less than 5,000 m (16,000 ft). The Pangong range runs parallel to the Ladakh Range for about 100 km (62 mi) northwest from Chushul along the southern shore of the Pangong Lake. Its highest point is about 6,700 m (22,000 ft) and the northern slopes are heavily glaciated. The region comprising the valley of the Shayok and Nubra rivers is known as Nubra. The Karakoram Range in Ladakh is not as mighty as in Baltistan. The massifs to the north and east of the Nubra–Siachen line include the Apsarasas Group (highest point at 7,245 m or 23,770 ft) the Rimo Muztagh (highest point at 7,385 m or 24,229 ft) and the Teram Kangri Group (highest point at 7,464 m or 24,488 ft) together with Mamostong Kangri (7,526 m or 24,692 ft) and Singhi Kangri (7,202 m or 23,629 ft). North of the Karakoram lies the Kunlun. Thus, between Leh and eastern Central Asia there is a triple barrier – the Ladakh Range, Karakoram Range, and Kunlun. Nevertheless, a major trade route was established between Leh and Yarkand.

Ladakh is a high altitude desert as the Himalayas create a rain shadow, generally denying entry to monsoon clouds. The main source of water is the winter snowfall on the mountains. Recent flooding in the region (e.g., the 2010 floods) has been attributed to abnormal rain patterns and retreating glaciers, both of which have been found to be linked to global climate change.[62] The Leh Nutrition Project, headed by Chewang Norphel, also known as the "Glacier Man", creates artificial glaciers as one solution for retreating glaciers.[63][64]

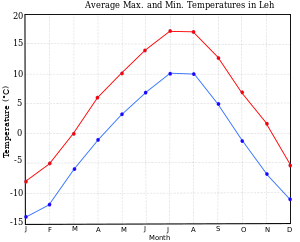

The regions on the north flank of the Himalayas – Dras, the Suru valley and Zangskar – experience heavy snowfall and remain cut off from the rest of the region for several months in the year, as the whole region remains cut off by road from the rest of the country. Summers are short, though they are long enough to grow crops. The summer weather is dry and pleasant. Temperature ranges are from 3 to 35 °C (37 to 95 °F) in summer and minimums range from −20 to −35 °C (−4 to −31 °F) in winter.[65]

Zanskar is the main river of the region along with its tributaries. The Zanskar gets frozen during winter and the famous Chadar trek takes place on this magnificent frozen river.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

پانوراما

النبيت والوحيش

Vegetation is extremely sparse in Ladakh except along streambeds and wetlands, on high slopes, and irrigated places. About 1250 plant species, including crops, were reported from Ladakh.[66] The plant Ladakiella klimesii, growing up to 6,150 metres (20,180 ft) above sea level, was first described here and named after this region.[67] The first European to study the wildlife of this region was William Moorcroft in 1820, followed by Ferdinand Stoliczka, an Austrian-Czech palaeontologist, who carried out a massive expedition there in the 1870s. There are many lakes in Ladakh such as Kyago Tso.

The bharal or blue sheep is the most abundant mountain ungulate in the Ladakh region, although it is not found in some parts of Zangskar and Sham areas.[68] The Asiatic ibex is a very elegant mountain goat that is distributed in the western part of Ladakh. It is the second most abundant mountain ungulate in the region with a population of about 6000 individuals. It is adapted to rugged areas where it easily climbs when threatened.[69] The Ladakhi Urial is another unique mountain sheep that inhabits the mountains of Ladakh. The population is declining, however, and there are not more than 3000 individuals left in Ladakh.[70] The urial is endemic to Ladakh, where it is distributed only along two major river valleys: the Indus and Shayok. The animal is often persecuted by farmers whose crops are allegedly damaged by it. Its population declined precipitously in the last century due to indiscriminate shooting by hunters along the Leh-Srinagar highway. The Tibetan argali or Nyan is the largest wild sheep in the world, standing 1.1 to 1.2 metres (3.5 to 4 ft) at the shoulder with the horn measuring 900–1,000 mm (35–39 in). It is distributed on the Tibetan plateau and its marginal mountains encompassing a total area of 2.5 million km2 (0.97 million sq mi). There is only a small population of about 400 animals in Ladakh. The animal prefers open and rolling terrain as it runs, unlike wild goats that climb into steep cliffs, to escape from predators.[71] The endangered Tibetan antelope, known as chiru in Indian English, or Ladakhi tsos, has traditionally been hunted for its wool (shahtoosh) which is a natural fibre of the finest quality and thus valued for its light weight and warmth and as a status symbol. The wool of chiru must be pulled out by hand, a process done after the animal is killed. The fibre is smuggled into Kashmir and woven into exquisite shawls by Kashmiri workers. Ladakh is also home to the Tibetan gazelle, which inhabits the vast rangelands in eastern Ladakh bordering Tibet.[72]

The kiang, or Tibetan wild ass, is common in the grasslands of Changthang, numbering about 2,500 individuals. These animals are in conflict with the nomadic people of Changthang who hold the Kiang responsible for pasture degradation.[73] There are about 200 snow leopards in Ladakh of an estimated 7,000 worldwide. The Hemis High Altitude National Park in central Ladakh is an especially good habitat for this predator as it has abundant prey populations. The Eurasian lynx, is another rare cat that preys on smaller herbivores in Ladakh. It is mostly found in Nubra, Changthang and Zangskar.[74] The Pallas's cat, which looks somewhat like a house cat, is very rare in Ladakh and not much is known about the species. The Tibetan wolf, which sometimes preys on the livestock of the Ladakhis, is the most persecuted amongst the predators.[75] There are also a few brown bears in the Suru Valley and the area around Dras. The Tibetan sand fox has been discovered in this region.[76] Among smaller animals, marmots, hares, and several types of pika and vole are common.[77]

النبيت

Scant precipitation makes Ladakh a high-altitude desert with extremely scarce vegetation over most of its area. Natural vegetation mainly occurs along water courses and on high altitude areas that receive more snow and cooler summer temperatures. Human settlements, however, are richly vegetated due to irrigation.[78] Natural vegetation commonly seen along watercourses includes seabuckthorn (Hippophae spp.), wild roses of pink or yellow varieties, tamarisk (Myricaria spp.), caraway, stinging nettles, mint, Physochlaina praealta, and various grasses.[79]

الاقتصاد

The land is irrigated by a system of channels which funnel water from the ice and snow of the mountains. The principal crops are barley and wheat. Rice was previously a luxury in the Ladakhi diet, but, subsidised by the government, has now become a cheap staple.[11]

Naked barley (Ladakhi: nas, Urdu: grim) was traditionally a staple crop all over Ladakh. Growing times vary considerably with altitude. The extreme limit of cultivation is at Korzok, on the Tso-moriri lake, at 4,600 m (15,100 ft), which has what are widely considered to be the highest fields in the world.[11]

A minority of Ladakhi people were also employed as merchants and caravan traders, facilitating trade in textiles, carpets, dyestuffs and narcotics between Punjab and Xinjiang. However, since the Chinese Government closed the borders between Tibet Autonomous Region and Ladakh, this international trade has completely dried up.[14][80]

Indus river flowing in the Ladakh region is endowed with vast hydropower potential. Solar and wind power potentials are also substantial. Though the region is a remote hilly area without all-weather roads, the area is also rich in limestone deposits to manufacture cement from the locally available cheap electricity for various construction needs.[81]

Since 1974, the Indian Government has encouraged a shift in trekking and other tourist activities from the troubled Kashmir region to the relatively unaffected areas of Ladakh. Although tourism employs only 4% of Ladakh's working population, it now accounts for 50% of the region's GNP.[14]

This era is recorded in Arthur Neves The Tourist's Guide to Kashmir, Ladakh, and Skardo, first published in 1911.[80]

النقل

There are about 1,800 km (1,100 mi) of roads in Ladakh of which 800 km (500 mi) are surfaced.[82] The majority of roads in Ladakh are looked after by the Border Roads Organisation. There are two main roads that connect Ladakh with the rest of the country, NH1 connecting Srinagar to Kargil and Leh, and NH3 connecting Manali to Leh. A third road to Ladakh is the Nimmu–Padam–Darcha road, which is under construction.[83]

There is an airport in Leh, Kushok Bakula Rimpochee Airport, from which there are daily flights to Delhi and weekly flights to Srinagar and Jammu. There are two airstrips at Daulat Beg Oldie and Fukche for military transport.[84] The airport at Kargil, Kargil Airport, was intended for civilian flights but is currently used by the Indian Army. The airport is a political issue for the locals who argue that the airport should serve its original purpose, i.e., should open up for civilian flights. Since past few years the Indian Air Force has been operating AN-32 air courier service to transport the locals during the winter seasons to Jammu, Srinagar and Chandigarh.[85][86] A private aeroplane company Air Mantra landed a 17-seater aircraft at the airport, in presence of dignitaries like the Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, marking the first ever landing by a civilian airline company at Kargil Airport.[87][88]

الديمغرافيا

| السنة[ιζ] | مقاطعة له | مقاطعة كارگيل | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| التعداد | نسبة التغير | الإناث لكل 1000 ذكر | التعداد | نسبة التغير | الإناث لكل 1000 ذكر | |

| 1951 | 40,484 | — | 1011 | 41,856 | — | 970 |

| 1961 | 43,587 | 0.74 | 1010 | 45,064 | 0.74 | 935 |

| 1971 | 51,891 | 1.76 | 1002 | 53,400 | 1.71 | 949 |

| 1981 | 68,380 | 2.80 | 886 | 65,992 | 2.14 | 853 |

| 2001 | 117,637 | 2.75 | 805 | 115,287 | 2.83 | 901 |

| 2011 | 133,487 | 690 | 140,802 | 810 | ||

The sex ratio for Leh district declined from 1011 females per 1000 males in 1951 to 805 in 2001, while for Kargil district it declined from 970 to 901.[89] The urban sex ratio in both the districts is about 640. The adult sex ratio reflects large numbers of mostly male seasonal and migrant labourers and merchants. About 84% of Ladakh's population lives in villages.[90] The average annual population growth rate from 1981 to 2001 was 2.75% in Leh District and 2.83% in Kargil district.[89]

الأديان

The Dras and Dha-Hanu regions are habitated by Brokpas, who are predominately followers of Islam while small minorities follow Tibetan Buddhism and Hinduism.[92] The region's population is split roughly in half between the districts of Leh and Kargil. 76.87% population of Kargil is Muslim (mostly Shia),[93][91] with a total population of 140,802, while that of Leh is 66.40% Buddhist, with a total population of 133,487, as per the 2011 census.[91][94][95]

An increasing number of Muslim men and Ladakhi Buddhist women are marrying each other following a decline in the population of Buddhist men in Ladakh, leaving more Buddhist women without a spouse.[96][97]

اللغات

The predominant mother-tongue in Leh district is Ladakhi (also called Bauti), a Tibetic language.[98] Purkhi, sometimes considered a dialect of Balti, is the predominant mother-tongue of Kargil district.[98][99] Educated Ladakhis usually know Hindi, Urdu and often English. Within Ladakh, there is a range of dialects, so that the language of the Chang-pa people may differ markedly from that of the Purig-pa in Kargil, or the Zangskaris, but they are all mutually comprehensible. Most Ladakhi people (especially the younger generations) speak fluently in English and in Hindi too, due to the languages education at school.[100] Administrative work and education are carried out in English.[101]

الثقافة

Ladakhi culture is similar to Tibetan culture.[102]

Cuisine

Ladakhi food has much in common with Tibetan food, the most prominent foods being thukpa (noodle soup) and tsampa, known in Ladakhi as ngampe (roasted barley flour). Edible without cooking, tsampa makes useful trekking food. Strictly Ladakhi dishes include skyu and chutagi, both heavy and rich soup pasta dishes, skyu being made with root vegetables and meat, and chutagi with leafy greens and vegetables.[103] As Ladakh moves toward a cash-based economy, foods from the plains of India are becoming more common.[104] As in other parts of Central Asia, tea in Ladakh is traditionally made with strong green tea, butter, and salt. It is mixed in a large churn and known as gurgur cha, after the sound it makes when mixed. Sweet tea (cha ngarmo) is common now, made in the Indian style with milk and sugar. Most of the surplus barley that is produced is fermented into chang, an alcoholic beverage drunk especially on festive occasions.[105]

Music and dance

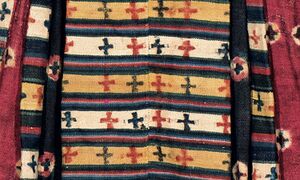

The music of Ladakhi Buddhist monastic festivals, like Tibetan music, often involves religious chanting in Tibetan as an integral part of the religion. These chants are complex, often recitations of sacred texts or in celebration of various festivals. Yang chanting, performed without metrical timing, is accompanied by resonant drums and low, sustained syllables. Religious mask dances are an important part of Ladakh's cultural life. Hemis monastery, a leading centre of the Drukpa tradition of Buddhism, holds an annual masked dance festival, as do all major Ladakhi monasteries. The dances typically narrate a story of the fight between good and evil, ending with the eventual victory of the former.[106] Weaving is an important part of traditional life in eastern Ladakh. Both women and men weave, on different looms.[107]

Sport

The most popular sport in Ladakh is ice hockey, which is played only on natural ice generally mid-December through mid-February.[108] Cricket is also very popular.[citation needed]

Archery is a traditional sport in Ladakh, and many villages hold archery festivals, which are as much about traditional dancing, drinking and gambling, as they are about the sport. The sport is conducted with strict etiquette, to the accompaniment of the music of surna and daman (shehnai and drum). Polo, the other traditional sport of Ladakh, is indigenous to Baltistan and Gilgit, and was probably introduced into Ladakh in the mid-17th century by King Singge Namgyal, whose mother was a Balti princess.[109]

Polo, popular among the Baltis, is an annual affair in Drass region of Kargil district.[110][111][112][113]

The Ladakh Marathon is a high-altitude marathon held in Leh every year since 2012. Held at a height of 11,500 to 17,618 feet (3,505 to 5,370 m), it is one of the world's highest marathons.[114]

الثقافة اللداخية مماثلة للثقافة التبتية.[115]

المكانة الاجتماعية للمرأة

A feature of Ladakhi society that distinguishes it from the rest of the state is the high status and relative emancipation enjoyed by women compared to other rural parts of India. Fraternal polyandry and inheritance by primogeniture were common in Ladakh until the early 1940s when these were made illegal by the government of Jammu and Kashmir. However, the practice remained in existence into the 1990s especially among the elderly and the more isolated rural populations.[116] Another custom is known as khang-bu, or 'little house', in which the elders of a family, as soon as the eldest son has sufficiently matured, retire from participation in affairs, yielding the headship of the family to him and taking only enough of the property for their own sustenance.[11]

الطب التقليدي

Tibetan medicine has been the traditional health system of Ladakh for over a thousand years. This school of traditional healing contains elements of Ayurveda and Chinese medicine, combined with the philosophy and cosmology of Tibetan Buddhism. For centuries, the only medical system accessible to the people have been the amchi, traditional doctors following the Tibetan medical tradition. Amchi medicine remains a component of public health, especially in remote areas.[117]

Programmes by the government, local and international organisations are working to develop and rejuvenate this traditional system of healing.[117][118] Efforts are underway to preserve the intellectual property rights of amchi medicine for the people of Ladakh. The government has also been trying to promote the sea buckthorn in the form of juice and jam, as some claim it possess medicinal properties.

The National Research Institute for Sowa-Rigpa in Leh is an institute for research into traditional medicine and a hospital providing traditional treatments.[119]

معرض صور

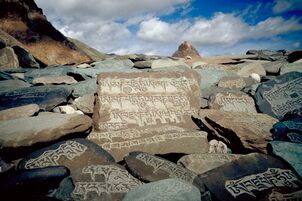

Carved stone tablets, each with the inscription "Om Mani Padme Hum" along the paths of Zanskar

انظر أيضاً

| هذه المقالة تحتوي نص هندي. بدون دعم الإظهار لتلك الأبجديات، فقد ترى علامات استفهام أو مربعات أو رموز أخرى بدلاً من الحروف الهندية؛ أو وضع غير منتظم للحروف المتحركة وفقدان لعلامات الوصل. |

- Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh (book)

- بلتي (لغة)

- بلتستان

- Baily Bridge

- جغرافيا لداخ

- لداخي (لغة)

- شمال شرق الهند

- Polyandry in Tibet

- السياحة في الهند

- Wildlife of Ladakh

ملاحظات

β^ This excludes Aksai Chin (37,555 km²), under Chinese administration.

γ^ He mentions twice a people called Dadikai, first along with the Gandarioi, and again in the catalogue of king Xerxes's army invading Greece. Herodotus also mentions the gold-digging ants of Central Asia.

δ^ In the 1st century, Pliny repeats that the Dards were great producers of gold.

ε^ Ptolemy situates the Daradrai on the upper reaches of the Indus

στ^ See Petech, Luciano. The Kingdom of Ladakh c. 950–1842 A.D., Istituto Italiano per il media ed Estremo Oriente, 1977. Hsuan-tsang describes a journey from Ch'u-lu-to (Kuluta, Kullu) to Lo-hu-lo (Lahul), then goes on saying that "from there to the north, for over 2000 li, the road is very difficult, with cold wind and flying snow"; thus one arrives in the kingdom of Mo-lo-so, or Mar-sa, synonymous with Mar-yul, a common name for Ladakh. Elsewhere, the text remarks that Mo-lo-so, also called San-po-ho borders with Suvarnagotra or Suvarnabhumi (Land of Gold), identical with the Kingdom of Women (Strirajya). According to Tucci, the Zan-zun kingdom, or at least its southern districts were known by this name by the 7th century Indians.

θ^ The Leh district is placed in Zone V,[مطلوب توضيح] while the Kargil district is placed in Zone IV[مطلوب توضيح] on the earthquake hazard scale

ια^ Early in the 20th century the chiru was seen in herds numbering in the thousands, surviving on remarkably sparse vegetation, they are very rare now.

ιζ^ Census was not carried out in Jammu and Kashmir in 1991 due to militancy

الهامش

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةladakh-britannica-current - ^ أ ب "The Gazette of India" (PDF). egazette.nic.in. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "Ladakh Gets Civil Secretariat". 17 October 2019.

- ^ "LG, UT Hqrs, Head of Police to have Sectts at both Leh, Kargil: Mathur". Daily Excelsior. 12 November 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "MHA.nic.in". MHA.nic.in. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Saltoro Kangri, India/Pakistan". peakbagger.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Part II—Section 3—Sub-section (ii), Controller of Publications, Delhi-110054, 25 November 2019, p. 2, http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2019/214357.pdf

- ^ Jina, Prem Singh (1996). Ladakh: The Land and the People. Indus Publishing. ISBN 81-7387-057-8.

- ^ Francke(1926) Vol. I, p. 93, notes.

- ^ Rizvi, Janet (2001). Trans-Himalayan Caravans – Merchant Princes and Peasant Traders in Ladakh. Oxford India Paperbacks.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Rizvi, Janet (1996). Ladakh — Crossroads of High Asia. Oxford University Press. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Crossroads" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Osada et al (2000), p. 298.

- ^ أ ب "Kargil Council For Greater Ladakh". The Statesman, 9 August 2003. 2003. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) خطأ استشهاد: وسم<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Statesman" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Loram, Charlie (2004) [2000]. Trekking in Ladakh (2nd Edition ed.). Trailblazer Publications.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) خطأ استشهاد: وسم<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "LoramCharlie" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Sandhu, Kamaljit Kaur (4 June 2019). "Government planning to redraw Jammu and Kashmir assembly constituency borders: Sources". India Today.

- ^ Pile, Tim (1 August 2019). "Ladakh: the good, bad and ugly sides to India's 'Little Tibet', high in the Himalayas". South Chinan Morning Post. ProQuest 2267352786.

- ^ Francke, August Hermann (1926), Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Volume II, Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing Press, pp. 93–, ISBN 978-81-206-0769-9, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.96793/page/n353/mode/2up Quote: Ladakh, the Persian transliteration of the Tibetan La-dvags, is warranted by the pronunciation of the word in several Tibetan districts. The terminal gs has the sound of the guttural gh or even kh in various Tibetan dialects. (Volume II, page 93)

- ^ Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakoram, BRILL, 2014, pp. 3–, ISBN 978-90-04-27180-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=CJCfAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA3 Quote: The single most important source [of Ladakhi history] is the La dvags rgyal rabs, the royal chronicle of Ladakh, which dates back to the 17th century.

- ^ Petech, Luciano (1977), The Kingdom of Ladakh, c. 950–1842 A.D., Instituto Italiano Per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, p. 22, https://www.academia.edu/download/48901732/1977_Kingdom_of_Ladakh_c_950-1842_AD_by_Petech_s.pdf[dead link]

- ^ Pirumshoev, H. S.; Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2003), "The Pamirs, Badakhshan and the Trans-Pamir States", History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. V — Development in contrast: From the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, UNESCO, pp. 238–239, ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1: "Under Aurangzeb (1659–1707), Mughal suzerainty was also acknowledged by Ladakh ('Great Tibet') in 1665, though it was contested in 1681–3 by the Oirat or Kalmuk (Qalmaq) rulers of Tibet."

- ^ Bogle, George; Manning, Thomas (2010), Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle to Tibet: And of the Journey of Thomas Manning to Lhasa, Cambridge University Press, p. 26, ISBN 978-1-108-02255-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=9Y7slbgVL4AC&pg=PR26

- ^ Zutshi, Rattan (13 January 2016). My Journey of Discovery (in الإنجليزية). Partridge Publishing. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-4828-4140-4.

- ^ Zutshi, Rattan (13 January 2016). My Journey of Discovery (in الإنجليزية). Partridge Publishing. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-4828-4140-4.

- ^ خطأ: الوظيفة "harvard_core" غير موجودة.: Xuanzang describes a journey from Ch'u-lu-to (Kuluta, Kullu) to Lo-hu-lo (Lahul), then goes on saying that "from there to the north, for over 2000 li, the road is very difficult, with cold wind and flying snow; thus one arrives in the kingdom of Mo-lo-so". Petech states, "geographically speaking, the region thus indicated is unmistakably Ladakh."

- ^ Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), pp. 7–8.

- ^ Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), p. 86.

- ^ Zeisler, Bettina (2011), "Kenhat, The Dialects of Upper Ladakh and Zanskari", Himalayan Languages and Linguistics: Studies in Phonology, Semantics, Morphology and Syntax, BRILL, pp. 293, ISBN 978-90-04-21653-2: "While the whole of Ladakh and adjacent regions were originally populated by speakers of Eastern Iranian (Scythian), Lower Ladakh (as well as Baltistan) was also subject to several immigration waves of Indoaryan (Dardic) speakers and other groups from Central Asia. Upper Ladakh and the neighbouring regions to the east, by contrast, seem to have been populated additionally by speakers of a non-Tibetan Tibeto-Burman language, namely West Himalayan (Old Zhangzhung;...)."

- ^ Bellezza, John Vincent (2014), The Dawn of Tibet: The Ancient Civilization on the Roof of the World, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, p. 101, ISBN 978-1-4422-3462-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=bZFuBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA101

- ^ خطأ: الوظيفة "harvard_core" غير موجودة.: "Ladakh's geographical position leaves no room for doubt that its ancient caravan routes must have often served as a path first for conquest and then for retreat of the opposing armies as they alternated between victory and defeat."

- ^ Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), pp. 15–16.

- ^ Flood, Finbarr Barry (2017). "A Turk in the Dukhang? Comparative Perspectives on Elite Dress in Medieval Ladakh and the Caucasus". Interaction in the Himalayas and Central Asia. Austrian Academy of Science Press: 231–243.

- ^ أ ب Howard, Neil (1997), "History of Ladakh", Recent Research on Ladakh 6, Motilal Banarsidass, p. 122, ISBN 9788120814325

- ^ أ ب ت Sheikh, Abdul Ghani (1995), "A Brief History of Muslims in Ladakh", Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5, Motilal Banarsidass, p. 189, ISBN 9788120814042

- ^ Buddhist Western Himalaya: A politico-religious history. Indus Publishing. 1 January 2001. ISBN 9788173871245. Retrieved 19 December 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kaul, Shridhar; Kaul, H. N. (1992). Ladakh Through the Ages, Towards a New Identity. ISBN 9788185182759.

- ^ Jina, Prem Singh (1996). Ladakh. ISBN 9788173870576.

- ^ Osmaston, Henry; Denwood, Philip (1995). Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5. ISBN 9788120814042.

- ^ Bora, Nirmala (2004). Ladakh. ISBN 9788179750124.

- ^ Kaul, H. N. (1998). Rediscovery of Ladakh. ISBN 9788173870866.

- ^ Osmaston, Henry; Denwood, Philip (1995). Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5. ISBN 9788120814042.

- ^ See the following studies (1) Halkias, T. Georgios(2009) "Until the Feathers of the Winged Black Raven Turn White: Sources for the Tibet-Bashahr Treaty of 1679–1684," in Mountains, Monasteries and Mosques, ed. John Bray. Supplement to Rivista Orientali, pp. 59–79; (2) Emmer, Gerhard(2007) "Dga' ldan tshe dbang dpal bzang po and the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679–84," in The Mongolia-Tibet Interface. Opening new Research Terrains in Inner Asia, eds. Uradyn Bulag, Hildegard Diemberger, Leiden, Brill, pp. 81–107; (3) Ahmad, Zahiruddin (1968) "New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679–84." East and West, XVIII, 3, pp. 340–361; (4) Petech, Luciano(1947) "The Tibet-Ladakhi Moghul War of 1681–83." The Indian Historical Quarterly, XXIII, 3, pp. 169–199.

- ^ Sali, M. L. (1998). India-China Border Dispute. ISBN 9788170249641.

- ^ Kaul, H. N. (1998). Rediscovery of Ladakh. ISBN 9788173870866.

- ^ Johan Elverskog (6 June 2011). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-0-8122-0531-2.

- ^ Gray Tuttle; Kurtis R. Schaeffer (12 March 2013). The Tibetan History Reader. Columbia University Press. pp. 603–. ISBN 978-0-231-14468-1.

- ^ Menon, P.M & Proudfoot, C.L., The Madras Sappers, 1947–1980, 1989, Thomson Press, Faridabad, India.

- ^ Dash, Dipak K. (16 July 2012). "Government may clear all weather tunnel to Leh today". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Bammi, Y.M., Kargil 1999 – the impregnable conquered. (2002) Natraj Publishers, Dehradun.

- ^ Stobdan, Phunchok (26 May 2020). "As China intrudes across LAC, India must be alert to a larger strategic shift". The Indian Express. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Stobdan, Phunchok (28 May 2020). "Ladakh concern overrides LAC dispute". The Tribune (Chandigarh). Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Kulkarni, Pranav (26 September 2014). "Ground report: Half of Chinese troops leave, rest to follow". The Indian Express. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Notification, Jammu, 8 February 2019, Government of Jammu and Kashmir

- ^ "Ladakh division headquarters to shuttle between Leh and Kargil: Governor Malik". 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Ladakh had been demanding UT status for a long time". Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Article 370 revoked Updates: Jammu & Kashmir is now a Union Territory, Lok Sabha passes bifurcation bill". Business Today (India). 6 August 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Already, Rajya Sabha Clears J&K As Union Territory Instead Of State, NDTV, 5 August 2019.

- ^ The Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Bill, 2019, 2019, http://www.prsindia.org/sites/default/files/bill_files/Jammu%20and%20Kashmir%20Reorganisation%20Bill%2C%202019.pdf

- ^ "LAHDC Act would continue and the Amendments of 2018 to be protected: Governor". Daily Excelsior. 30 August 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت One year of union territory status: Ladakh brims with hope, Times of India, 3 August 2020.

- ^ The Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladák published in 1890 Compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch in fact unequivocally states inter alia in pages 520 and 364 that Khotán is "a province in the Chinese Empire lying to the north of the Eastern Kuenlun (Kun Lun) range, which here forms the boundary of Ladák" and "The eastern range forms the southern boundary of Khotán, and is crossed by two passes, the Yangi or Elchi Díwan, crossed in 1865 by Johnson and the Hindútak Díwan, crossed by Robert Schlagentweit in 1857".

- ^ "Multi-hazard Map of India" (PDF). United Nations Development Program. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Strzepek, Kenneth M.; Joel B. Smith (1995). As Climate Changes: International Impacts and Implications. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46796-4.

- ^ "OneWorld South Asia – Glacier man Chewang Norphel brings water to Ladakh". 2 July 2007. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007.

- ^ "Edugreen.teri.res.in". Edugreen.teri.res.in. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Climate in Ladakh". LehLadakhIndia.com. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ^ Dvorský, Miroslav (2018). A field guide to the flora of Ladakh. Prague: Academia. ISBN 978-80-200-2826-6.

- ^ German, Dmitry A.; Al-Shehbaz, Ihsan A. (1 December 2010). "Nomenclatural novelties in miscellaneous Asian Brassicaceae (Cruciferae)". Nordic Journal of Botany. 28 (6): 646–651. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.2010.00983.x. ISSN 1756-1051.

- ^ Namgail, T.; Fox, J.L.; Bhatnagar, Y.V. (2004). "262" (PDF). Habitat segregation between sympatric Tibetan argali Ovis ammon hodgsoni and blue sheep Pseudois nayaur in the Indian Trans-Himalaya. London: reg.wur.nl. pp. 57–63.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Namgail, T (2006). "Winter Habitat Partitioning between Asiatic Ibex and Blue Sheep in Ladakh, Northern India" (PDF). Journal of Mountain Ecology. 8: 7–13.

- ^ Namgail, T. (2006). Trans-Himalayan large herbivores: status, conservation, and niche relationships. Report submitted to the Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx Zoo, New York.

- ^ Namgail, T.; Fox, J.L.; Bhatnagar, Y.V. (2007). "Habitat shift and time budget of the Tibetan argali: the influence of livestock grazing" (PDF). Ecological Research. 22: 25–31. doi:10.1007/s11284-006-0015-y. S2CID 12451184.

- ^ Namgail, T.; Bagchi, S.; Mishra, C.; Bhatnagar, Y.V. (2008). "Distributional correlates of the Tibetan gazelle in northern India: Towards a recovery programme" (PDF). Oryx. 42: 107–112. doi:10.1017/s0030605308000768.

- ^ Bhatnagar, Y. V.; Wangchuk, R.; Prins, H. H.; van Wieren, S. E.; Mishra, C. (2006). "Perceived conflicts between pastoralism and conservation of the Kiang Equus kiang in the Ladakh Trans- Himalaya". Environmental Management. 38 (6): 934–941. doi:10.1007/s00267-005-0356-2. PMC 1705511. PMID 16955231.

- ^ Namgail, T (2004). "Eurasian lynx in Ladakh". Cat News. 40: 21–22.

- ^ Namgail, T.; Fox, J.L.; Bhatnagar, Y.V. (2007). "Carnivore-caused livestock mortality in Trans-Himalaya" (PDF). Environmental Management. 39 (4): 490–496. doi:10.1007/s00267-005-0178-2. PMID 17318699. S2CID 30967502.

- ^ Namgail, T.; Bagchi, S.; Bhatnagar, Y.V.; Wangchuk, R. (2005). "Occurrence of the Tibetan sand fox Vulpes ferrilata Hodgson in Ladakh: A new record for the Indian sub-Continent". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 102: 217–219.

- ^ Bagchi, S.; Namgail, T.; Ritchie, M.E. (2006). "Small mammalian herbivores as mediators of plant community dynamics in the high-altitude arid rangelands of Trans-Himalayas". Biological Conservation. 127 (4): 438–442. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.003.

- ^ Vishwas S. Kale (23 May 2014). Landscapes and Landforms of India. Springer. ISBN 9789401780292.

- ^ Satish K. Sharma (2006). Temperate Horticulture: Current Scenario. New India Publisher. ISBN 9788189422363.

- ^ أ ب Weare, Garry (2002). Trekking in the Indian Himalaya (4th ed.). Lonely Planet.

- ^ "Distribution of Rocks and Minerals in J&K state". Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "State Development Report—Jammu and Kashmir, Chapter 3A" (PDF). Planning Commission of India. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "LAC stand-off: BRO's new highway untraceable by enemy, saves hours and gives 365-day connectivity". The Times of India (in الإنجليزية). ANI. 5 September 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ IAF craft makes successful landing near China border (4 November 2008). "NDTV.com". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Air Courier Service From Kargil Begins Operation". news.outlookindia.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "IAF to start air services to Kargil during winter from December 6". NDTV.com. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Fayyaz, Ahmed Ali (7 January 2013). "Kargil gets first civil air connectivity". The Hindu. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ GK News Network (2 January 2013). "Air Mantra to operate flights to Kargil". Greater Kashmir. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ أ ب "State Development Report—Jammu and Kashmir, Chapter 2 – Demographics" (PDF). Planning Commission of India. 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "Rural population". Education for all in India. 1999. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ أ ب ت C-1 Population By Religious Community – Jammu & Kashmir. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-01/DDW01C-01%20MDDS.XLS. Retrieved on 28 July 2020. - ^ "Religion Data of Census 2011: XXXIII JK-HP-ST" (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Vijay, Tarun (30 January 2008). "Endangered Ladakh". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Kargil District Population Census 2011-2020, Jammu and Kashmir literacy sex ratio and density". www.census2011.co.in.

- ^ "Leh District Population Census 2011-2020, Jammu and Kashmir literacy sex ratio and density". www.census2011.co.in.

- ^ Manish, Sai; Anzar, Khalid (16 September 2017). "Why Buddhist women are marrying Muslim men in Ladakh". Business Standard. New Delhi , Leh.

- ^ Raj, Suhasini; Gettleman, Jeffrey (12 October 2017). "On the Run for Love: Couple Bridges a Buddhist-Muslim Divide". The New York Times. LADAKH REGION, India.

- ^ أ ب ت C-16 Population By Mother Tongue – Jammu & Kashmir. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-16/DDW-C16-STMT-MDDS-0100.XLSX. Retrieved on 18 July 2020. - ^ Rather, Ali Mohammad (September 1999), "Kargil: The Post-War Scenario", Journal of Peace Studies (International Center for Peace Studies) 6 (5–6), http://www.icpsnet.org/description.php?ID=138

- ^ "Ladakhi Language & Phrasebook". Leh-Ladakh Taxi Booking.

- ^ "About Ladakh". BIRDING IN LADAKH.

- ^ "Ladakh Festival – a Cultural Spectacle". EF News International. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2006.

- ^ Motup, Sonam. "Food & Cuisine: 10 Best Dishes to Eat in Leh-Ladakh 🥄🥣".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Namgail, T.; Jensen, A.; Padmanabhan, S.; Desor, S.; Dolma, R. (2019). Dhontang: Food in Ladakh. Central Institute of Buddhist Studies, Local Futures. pp. 1–44. ISBN 978-93-83802-15-9.

- ^ Norberg-Hodge, Helena (2000). Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh. Oxford India Paperbacks.

- ^ "Masks: Reflections of Culture and Religion". Dolls of India. 12 January 2003. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "Living Fabric: Weaving Among the Nomads of Ladakh Himalaya". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ Sherlip, Adam. "Hockey Foundation".

- ^ "Ladakh culture". Jammu and Kashmir Tourism. Archived from the original on 12 July 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "Lalit Group Organises Polo Tourney in Drass, Celebrating 100 Years, Sports Events Imperative To Showcase Talent: Omar". Greater Kashmir. 10 July 2011. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Khagta, Himanshu (18 July 2011). "Traditonal [sic] Polo in Drass, Ladakh | Himanshu Khagta – Travel Photographer in India". PhotoShelter: Himanshu Khagta. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Manipur lifts Lalit Suri Polo Cup". State Times. 12 June 2012. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Business Hotels in India – Event Planning in India – The Lalit Hotels". Archived from the original on 14 March 2013.

- ^ "LAHDC organises 3rd Ladakh Marathon at Leh | Business Standard News". Business Standard India. Business-standard.com. Press Trust of India. 15 September 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ "Ladakh Festival - a Cultural Spectacle". EF News International. Retrieved 2006-08-28.

- ^ Gielen, Uwe (1998). "Gender roles in traditional Tibetan cultures". In L.L Adler (Ed.), International Handbook on Gender Roles. Westport, CT: Greenwood.: 413–437.

- ^ أ ب "Plantlife.org project on medicinal plants of importance to amchi medicine". Plantlife.org.uk. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "A government of India project in support of Sowa Rigpa-'amchi' medicine". Cbhi-hsprod.nic.in. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Modi govt to promote Tibetan healing system with AIIMS-like Sowa-Rigpa hospital in Leh". ThePrint. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

للاستزادة

- Allan, Nigel J. R. 1995 Karakorum Himalaya: Sourcebook for a Protected Area. IUCN. ISBN 969-8141-13-8

- Cunningham, Alexander. 1854. Ladak: Physical, Statistical, and Historical; with notices of the surrounding countries. Reprint: Sagar Publications, New Delhi. 1977.

- Desideri (1932). An Account of Tibet: The Travels of Ippolito Desideri 1712-1727. Ippolito Desideri. Edited by Filippo De Filippi. Introduction by C. Wessels. Reproduced by Rupa & Co, New Delhi. 2005

- Drew, Federic. 1877. The Northern Barrier of India: a popular account of the Jammoo and Kashmir Territories with Illustrations. 1st edition: Edward Stanford, London. Reprint: Light & Life Publishers, Jammu. 1971.

- Francke, A. H. (1914), 1920, 1926. Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Vol. 1: Personal Narrative; Vol. 2: The Chronicles of Ladak and Minor Chronicles, texts and translations, with Notes and Maps. Reprint: 1972. S. Chand & Co., New Delhi. (Google Books)

- Gillespie, A. (2007). Time, Self and the Other: The striving tourist in Ladakh, north India. In Livia Simao and Jaan Valsiner (eds) Otherness in question: Development of the self. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

- Gillespie, A. (2007). In the other we trust: Buying souvenirs in Ladakh, north India. In Ivana Marková and Alex Gillespie (Eds.), Trust and distrust: Sociocultural perspectives. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

- Gordon, T. E. 1876. The Roof of the World: Being the Narrative of a Journey over the high plateau of Tibet to the Russian Frontier and the Oxus sources on Pamir. Edinburgh. Edmonston and Douglas. Reprint: Ch’eng Wen Publishing Company. Tapei. 1971.

- Harvey, Andrew. 1983. A Journey in Ladakh. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York.

- Knight, E. F. 1893. Where Three Empires Meet: A Narrative of Recent Travel in: Kashmir, Western Tibet, Gilgit, and the adjoining countries. Longmans, Green, and Co., London. Reprint: Ch'eng Wen Publishing Company, Taipei. 1971.

- Knight, William, Henry. 1863. Diary of a Pedestrian in Cashmere and Thibet. Richard Bentley, London. Reprint 1998: Asian Educational Services, New Delhi.

- Moorcroft, William and Trebeck, George. 1841. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Panjab; in Ladakh and Kashmir, in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara... from 1819 to 1825, Vol. II. Reprint: New Delhi, Sagar Publications, 1971.

- Norberg-Hodge, Helena. 2000. Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh. Rider Books, London.

- Peissel, Michel. 1984. The Ants' Gold: The Discovery of the Greek El Dorado in the Himalayas. Harvill Press, London.

- Rizvi, Janet. 1998. Ladakh, Crossroads of High Asia. Oxford University Press. 1st edition 1963. 2nd revised edition 1996. 3rd impression 2001. ISBN 0-19-564546-4.

- Trekking in Zanskar & Ladakh: Nubra Valley, Tso Moriri & Pangong Lake, Step By step Details of Every Trek: a Most Authentic & Colourful Trekkers' guide with maps 2001–2002 Abebooks.co.uk

- Zeisler, Bettina. (2010). "East of the Moon and West of the Sun? Approaches to a Land with Many Names, North of Ancient India and South of Khotan." In: The Tibet Journal, Special issue. Autumn 2009 vol XXXIV n. 3-Summer 2010 vol XXXV n. 2. "The Earth Ox Papers", edited by Roberto Vitali, pp. 371–463.

- The Road to Lamaland - by Martin Louis Alan Gompertz

- Magic Ladakh - by Martin Louis Alan Gompertz

المراجع

- Francke, A. H. (1914, 1926). Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Two Volumes. Calcutta. 1972 reprint: S. Chand, New Delhi.

وصلات خارجية

- "Ladakh District". Leh-Ladakh.

- "Official website of Government of Jammu and Kashmir". Jammu and Kashmir Tourism.

- "Photo Galleries of Ladakh". Sights and people of Ladakh. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- "Many useful resources including a number of full text historical works". Silk Road Seattle - University of Washington. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- "Sustainable development and appropriate technology issues". The Ladakh Project. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- "Official site of the Autonomous Hill Development Council, Leh". Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- "Improvement of rural people livelihood in cold desert areas of the Western Himalayas". International NGO Network & 20 years experience of GERES in Ladakh. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

قالب:Proposed states and union territories of India

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 errors: extra text: edition

- Articles with dead external links from March 2022

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- مقالات تحتوي نصوصاً باللغة التبتية

- Articles containing أردو-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2020

- Articles containing فارسية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from March 2018

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2022

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from March 2010

- جغرافيا جامو وكشمير

- لداخ

- Proposed states and union territories in India