إيران الأفشارية

الدولة الأفشارية ممالک محروسه ایران | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1736–1796 | |||||||||||||||||

The Afsharid Persian Empire at its greatest extent in 1741-1743 under نادر شاه | |||||||||||||||||

| الوضع | امبراطورية | ||||||||||||||||

| العاصمة | مشهد | ||||||||||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | |||||||||||||||||

| الحكومة | ملكية مطلقة | ||||||||||||||||

| شاهنشاه | |||||||||||||||||

• 1736–1747 | نادر شاه | ||||||||||||||||

• 1747–1748 | عادل شاه | ||||||||||||||||

• 1748 | إبراهيم أفشار | ||||||||||||||||

• 1748–1796 | شاهرخ أفشار | ||||||||||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||||||||||

• تأسست | 22 يناير 1736 | ||||||||||||||||

• انحلت | 1796 | ||||||||||||||||

| العملة | تومان[4] | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

جزء من سلسلة عن |

|---|

| تاريخ إيران |

|

|

خط زمني |

الأفشار قبيلة تركمانية كانت تقطن شمال شرقي الأناضول، ثم دخلت كفصيل مهم في الجيش الصفوي (والصفويون من التركمان أيضاً). حكمت في فارس وأفغانستان 1736-1796. وكان مقرهم مشهد.

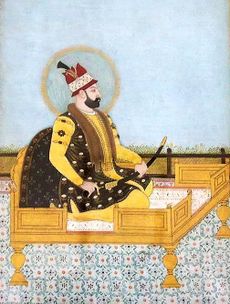

تأسست دولة الأفشاريين أثناء عهد نادر أفشار الذي ينحدر من قبيلة أفشار التركمانية- والتي كانت إحدى فصائل تنظيم قزل باش العسكري الشيعي الصوفي المذهب.

برز نادر أفشار (التركماني) كقائد عسكري لآخر الشاهات الصفويين . و كان له دور كبير في تزعم حركة المقاومة العسكرية لتحرير إيران من الاحتلال الأفغاني الذي قامت به قبيلة الغلزاي الأفغانية (ذات الأصول التركية أيضاً) منطلقاً من مدينة "مشهد"، وبعد نجاحه انتهى به الأمر إلى أن نصب نفسه شاهاً (1736-1747) وأخذ اسم نادر شاه. يعتبر نادر شاه واحداً من أكبر الغزاة الفاتحين في تاريخ إيران الحديث حيث قام عام 1737 بالإستيلاء على أفغانستان و بعض الأجزاء من وسط آسيا -خانية خيوة- ثم قاد حملة (1738-1739) إلى الهند، تمكن فيها من الإستيلاء على دلهي. حاول داخلياً أن يتبنى مذهباً للدولة يوفق بين الشيعة والسنة. قتل سنة 1747 على يد أحد قواده. لم يتمكن خلفاءه من الحفاظ على مملكته و انحصر ملك حفيده -الأعمى- شاه رخ (1748-1796) في خراسان حتى سنة 1796 و قضاء القاجار (وهم من التركمان أيضاً) على المملكة نهائياً، وتأسيس سلالة تركمانية جديدة هي الأسرة القاجارية التي حكمت إيران حتى عام 1924.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تأسيس الأسرة

فتوحات نادر شاه ومشكلة الخلافة

سقوط الأسرة الهوتكية

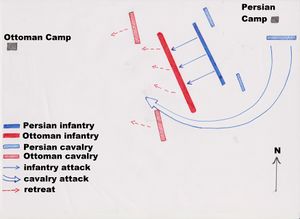

أول حملة عثمانية واسترداد القوقاز

نادر يصبح ملكاً

غزو امبراطورية المغل

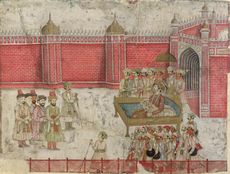

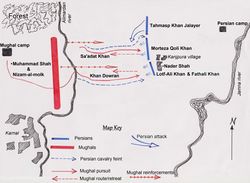

In 1738, Nader Shah conquered Kandahar, the last outpost of the Hotaki dynasty. His thoughts now turned to the Mughal Empire based in Delhi. This once powerful Muslim state to the east was falling apart as the nobles became increasingly disobedient and the Hindu Marathas of the Maratha Empire made inroads on its territory from the south-west. Its ruler Muhammad Shah was powerless to reverse this disintegration. Nader asked for the Afghan rebels to be handed over, but the Mughal emperor refused.

شمال القوقاز وآسيا الوسطى وجزيرة العرب والحرب العثمانية الثانية

Nader now decided to punish Daghestan for the death of his brother Ebrahim Qoli on a campaign a few years earlier. In 1741, while Nader was passing through the forest of Mazandaran on his way to fight the Daghestanis, an assassin took a shot at him but Nader was only lightly wounded. He began to suspect his son was behind the attempt and confined him to Tehran. Nader's increasing ill health made his temper ever worse. Perhaps it was his illness that made Nader lose the initiative in his war against the Lezgin tribes of Daghestan. Frustratingly for him, they resorted to guerrilla warfare and the Persians could make little headway against them.[5] Though Nader managed to take most of Dagestan during his campaign, the effective guerrilla warfare as deployed by the Lezgins, but also the Avars and Laks made the Iranian re-conquest of this particular North Caucasian region this time a short lived one; several years later, Nader was forced to withdraw. During the same period, Nader accused his son of being behind the assassination attempt in Mazandaran. Reza angrily protested his innocence, but Nader had him blinded as punishment, although he immediately regretted it. Soon afterwards, Nader started executing the nobles who had witnessed his son's blinding. In his last years, Nader became increasingly paranoid, ordering the assassination of large numbers of suspected enemies.

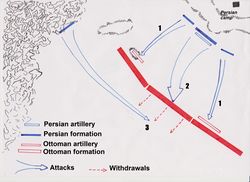

With the wealth he gained, Nader started to build a Persian navy. With lumber from Mazandaran, he built ships in Bushehr. He also purchased thirty ships in India.[6] He recaptured the island of Bahrain from the Arabs. In 1743, he conquered Oman and its main capital Muscat. In 1743, Nader started another war against the Ottoman Empire. Despite having a huge army at his disposal, in this campaign Nader showed little of his former military brilliance. It ended in 1746 with the signing of a peace treaty, in which the Ottomans agreed to let Nader occupy Najaf.[7]

العسكرية

The military forces of the Afsharid dynasty of Persia had their origins in the relatively obscure yet bloody inter-factional violence in Khorasan during the collapse of the Safavid state. شرذمة صغيرة من المقاتلين بقيادة أمير الحرب المحلي نادر قلي من قبيلة أفشار التركمانية في شمال شرق إيران were no more than a few hundred men. Yet at the height of Nader's power as the king of kings, Shahanshah, he commanded an army of 375,000 fighting men which constituted the single most powerful military force of its time,[8][9] led by one of the most talented and successful military leaders of history.[10]

After the assassination of Nader Shah at the hands of a faction of his officers in 1747, Nader's powerful army fractured as the Afsharid state collapsed and the country plunged into decades of civil war. Although there were numerous Afsharid pretenders to the throne, (amongst many other), who attempted to regain control of the entire country, Persia remained a fractured political entity in turmoil until the campaigns of أغا محمد خان قاجار toward the very end of the eighteenth century reunified the nation.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الحرب الأهلية وسقوط الأفشاريين

بعد وفاة نادر في 1747، his nephew Ali Qoli (who may have been involved in the assassination plot) seized the throne and proclaimed himself Adil Shah ("The Just King"). He ordered the execution of all Nader's sons and grandsons, with the exception of the 13-year-old Shahrokh, the son of Reza Qoli.[12] Meanwhile, Nadir's former treasurer, Ahmad Shah Abdali, had declared his independence by founding the Durrani Empire. In the process, the eastern territories were lost and in the following decades became part of Afghanistan, the successor-state to the Durrani Empire. The northern territories, Iran's most integral regions, had a different fate. Erekle II and Teimuraz II, who, in 1744, had been made the kings of Kakheti and Kartli respectively by Nader himself for their loyal service,[13] capitalized on the eruption of instability and declared de facto independence. Erekle II assumed control over Kartli after Teimuraz II's death, thus unifying the two as the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, becoming the first Georgian ruler in three centuries to preside over a politically unified eastern Georgia,[14] and due to the frantic turn of events in mainland Iran he would be able to remain de facto autonomous through the Zand period.[15] Under the successive Qajar dynasty, Iran managed to restore Iranian suzerainty over the Georgian regions, until they would be irrevocably lost in the course of the 19th century, to neighbouring Imperial Russia.[16] Many of the rest of the territories in the Caucasus, comprising modern-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Dagestan broke away into various khanates. Until the advent of the Zands and Qajars, its rulers had various forms of autonomy, but stayed vassals and subjects to the Iranian king.[17] Under the early Qajars, these territories in Transcaucasia and Dagestan would all be fully reincorporated into Iran, but eventually permanently lost as well (alongside Georgia), in the course of the 19th century to Imperial Russia through the two Russo-Persian Wars of the 19th century.[16]

Adil made the mistake of sending his brother Ebrahim to secure the capital Isfahan. Ebrahim decided to set himself up as a rival, defeated Adil in battle, blinded him and took the throne. Adil had reigned for less than a year. Meanwhile, a group of army officers freed Shahrokh from prison in Mashhad and proclaimed him shah in October 1748. Ebrahim was defeated and died in captivity in 1750 and Adil was also put to death at the request of Nader Shah's widow. Shahrokh was briefly deposed in favour of another puppet ruler Soleyman II but, although blinded, Shahrokh was restored to the throne by his supporters. He reigned in Mashhad and from the 1750s his territory was mostly confined to the city and its environs.[11] In 1796 Mohammad Khan Qajar, the founder of the Qajar dynasty, seized Mashhad and tortured Shahrokh to force him to reveal the whereabouts of Nader Shah's treasures. Shahrokh died of his injuries soon after and with him the Afsharid dynasty came to an end.[19][20] One of Shahrokh's sons, Nader Mirza, revolted in 1797 upon the death of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar but the revolt was crushed and he was executed in April 1803. Shahrokh's descendants continue into the 21st century under the Afshar Naderi surname.

السياسة الدينية

The Safavids had introduced Shi'a Islam as the state religion of Iran. Nader was probably brought up as a Shi'a [21] but later espoused the Sunni[22] faith as he gained power and began to push into the Ottoman Empire. He believed that Safavid Shi'ism had intensified the conflict with the Sunni Ottoman Empire. His army was a mix of Shi'a and Sunni (with a notable minority of Christians) and included his own Qizilbash as well as Uzbeks, Afghans, Christian Georgians and Armenians,[23][24] and others. He wanted Persia to adopt a form of religion that would be more acceptable to Sunnis and suggested that Persia adopt a form of Shi'ism he called "Ja'fari", in honour of the sixth Shi'a imam Ja'far al-Sadiq. He banned certain Shi'a practices which were particularly offensive to Sunnis, such as the cursing of the first three caliphs. Personally, Nader is said to have been indifferent towards religion and the French Jesuit who served as his personal physician reported that it was difficult to know which religion he followed and that many who knew him best said that he had none.[19] Nader hoped that "Ja'farism" would be accepted as a fifth school (mazhab) of Sunni Islam and that the Ottomans would allow its adherents to go on the hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca, which was within their territory. In the subsequent peace negotiations, the Ottomans refused to acknowledge Ja'farism as a fifth mazhab but they did allow Persian pilgrims to go on the hajj. Nader was interested in gaining rights for Persians to go on the hajj in part because of revenues from the pilgrimage trade.[6] Nader's other primary aim in his religious reforms was to weaken the Safavids further since Shi'a Islam had always been a major element in support for the dynasty. He had the chief mullah of Persia strangled after he was heard expressing support for the Safavids. Among his reforms was the introduction of what came to be known as the kolah-e Naderi. This was a hat with four peaks which symbolised the first four caliphs.

قائمة الملوك الأفشاريين

- نادر شاه (1736–1747)

- عادل شاه (1747–1748)

- إبراهيم أفشار (1748)

- شاهرخ أفشار (1748–1796)

شجرة العائلة

| إمام قلي (ت. 1704) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| إبراهيم خان (d. 1738) | نادر شاه (r. 1736–1747)1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| عادل شاه (r. 1747–1748)2 | إبراهيم أفشار (r. 1748)3 | رضا قلي ميرزا (b. 1719 – d.1747) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| شاهرخ أفشار (r. 1748–1796)4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نادر ميرزا (d. 1803) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ Katouzian, Homa (2003). Iranian History and Politics. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 0-415-29754-0.

Indeed, since the formation of the Ghaznavids state in the tenth century until the fall of Qajars at the beginning of the twentieth century, most parts of the Iranian cultural regions were ruled by Turkic-speaking dynasties most of the time. At the same time, the official language was Persian, the court literature was in Persian, and most of the chancellors, ministers, and mandarins were Persian speakers of the highest learning and ability.

- ^ "HISTORIOGRAPHY vii. AFSHARID AND ZAND PERIODS – Encyclopaedia Iranica".

Afsharid and Zand court histories largely followed Safavid models in their structure and language, but departed from long-established historiographical conventions in small but meaningful ways.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia. I.B. Tauris. pp. 157, 279. ISBN 1-84511-982-7.

- ^ Aliasghar Shamim, Iran during the Qajar Reign, Tehran: Scientific Publications, 1992, p. 287

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker. "A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East" p 739

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEncyclopedia Iranica - ^ This section: Axworthy pp. 175–274

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2007). "The Army of Nader Shah". Iranian Studies. Informa UK. 40 (5): 635–646. doi:10.1080/00210860701667720. S2CID 159949082.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant, . I. B. Tauris

- ^ Axworthy, Michael, "Iran: Empire of the Mind", Penguin Books, 2007. p158

- ^ أ ب Malcolm, Sir John (1829). The History of Persia: From the Most Early Period to the Present Time (in الإنجليزية). Murray.

- ^ Cambridge History p.59

- ^ Ronald Grigor Suny. "The Making of the Georgian Nation" Indiana University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0253209153 p 55

- ^ Yar-Shater, Ehsan. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. 8, parts 4-6 Routledge & Kegan Paul (original from the University of Michigan) p 541

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, p. 328.

- ^ أ ب Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond p 728-729 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- ^ Encyclopedia of Soviet law By Ferdinand Joseph Maria Feldbrugge, Gerard Pieter van den Berg, William B. Simons, Page 457

- ^ Perry, Jonothan R. Karim Khan Zand. N.p.: Oneworld, 2006. Ebook, retrieved July 6, 2016. ISBN 1851684352

- ^ أ ب Axworthy p.168

- ^ Cambridge History pp.60–62

- ^ Axworthy p.34

- ^ Mattair, Thomas R. (2008). Global security watch--Iran: a reference handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 3. ISBN 9780275994839. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ "The Army of Nader Shah" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Steven R. Ward. Immortal, Updated Edition: A Military History of Iran and Its Armed Forces Georgetown University Press, 8 jan. 2014 p 52

المصادر

- Michael Axworthy, The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. Hardcover 348 pages (26 July 2006) Publisher: I.B. Tauris Language: English ISBN 1-85043-706-8

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521200954.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

وصلات خارجية

- "Afsharids", Encyclopedia Iranica (mostly about Asharids after Nader Shah)

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing فارسية-language text

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the symbol caption or type parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- الأسرة الأفشارية

- Iranian dynasties

- Early Modern history of Iran

- Afshar tribe

- ملكيات سابقة في آسيا

- أسر حاكمة مسلمة إيرانية

- Iranian royalty

- أسر حاكمة في الشرق الأوسط

- عائلات ملكية شرق أوسطية

- Shia dynasties

- أسر توركية

- عقد 1730 في إيران

- عقد 1740 في إيران

- عقد 1750 في إيران

- عقد 1760 في إيران

- عقد 1770 في إيران

- عقد 1780 في إيران

- عقد 1790 في إيران

- عقد 1800 في إيران

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1736

- دول وأقاليم انحلت في 1802

- تأسيسات 1736 في آسيا

- انحلالات 1802 في آسيا

- القرن 18 في أفغانستان

- القرن 18 في إيران

- القرن 18 في أرمينيا

- القرن 18 في أذربيجان

- Early Modern history of Georgia (country)

- تاريخ داغستان

- تاريخ دربند

- تاريخ پاكستان

- Early Modern history of Iraq

- ولايات سابقة في العالم الإسلامي

- تاريخ إيران

- تاريخ البحرين

- تاريخ أفغانستان

- تاريخ أوزبكستان

- تاريخ تركمانستان

- States and territories established by the Afshar tribe

- Historical transcontinental empires

- بلدان سابقة