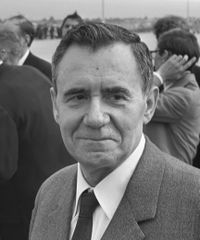

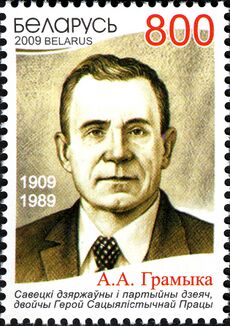

أندريه گروميكو

أندريه أندرييفيتش جروميكو (روسية: Андре́й Андре́евич Громы́ко؛ بالبيلاروسية: Андрэ́й Андрэ́евіч Грамы́ка؛ 18 يوليو [ن.ق. 5 يوليو] 1909 – 2 يوليو 1989) كان مسؤولاً رفيعاً في الاتحاد السوفيتي السابق لفترة طويلة. فقد عمل وزيرًا للخارجية بين عامي 1957 و1985. وفي عام 1985 أعفي من منصبه كوزير للخارجية وتم تعيينه رئيسًا للجنة التنفيذية الدائمة لمجلس السوفييت الأعلى، وكان منصبًا شرفيًا إلى حد كبير. أصبح في عام 1973 عضوًا في المكتب السياسي، وهو الهيئة الصانعة لسياسة الحزب الشيوعي. واعتزل جروميكو منصبه عام 1988.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

النشأة

وُلد جُروميكو لأبوين فلاحين بالقرب من مينسك، والتحق بالخدمة الدبلوماسية السوڤيتية عام 1939، حيث عمل سفيرًا سوڤيتياً لدى الولايات المتحدة بين عامي 1943 و1946.

السفير والحرب العالمية الثانية

في مطلع 1939, Gromyko started working for the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs in Moscow. Gromyko became the Head of the Department of Americas and because of his position Gromyko met with United States ambassador to the Soviet Union Lawrence Steinhardt. Gromyko believed Steinhardt to be "totally uninterested in creating good relations between the US and the USSR"[2] and that Steinhardt's predecessor Joseph Davies was more "colourful" and seemed "genuinely interested" in improving the relations between the two countries.[3] Davies received the Order of Lenin for his work in trying to improve diplomatic relations between the US and the USSR. After heading the Americas department for 6 months, Gromyko was called upon by Joseph Stalin. Stalin started the conversation by telling Gromyko that he would be sent to the Soviet embassy in the United States to become second-in-command. "The Soviet Union," Stalin said, "should maintain reasonable relations with such a powerful country like the United States, especially in light of the growing fascist threat". Vyacheslav Molotov contributed with some minor modifications but mostly agreed with what Stalin had said.[4] "How are your English skills improving?," Stalin asked, "Comrade Gromyko you should pay a visit or two to an American church and listen to their sermons. Priests usually speak correct English with good accents. Do you know that the Russian revolutionaries when they were abroad, always followed this practice to improve their skills in foreign languages?" Gromyko was quite amazed about what Stalin had just told him but he never visited an American church.[5]

Gromyko had never been abroad before and, to get to the United States, he had to travel via airplane through Romania, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia to Genoa, Italy, where they boarded a ship to the United States.[6] He later wrote in his Memoirs that New York City was a good example on how humans, by the "means of wealth and technology are able to create something that is totally alien to our nature". He further noticed the New York working districts which, in his own opinion, were proof of the inhumanity of capitalism and of the system's greed.[7] Gromyko met and consulted with most of the senior officers of the United States government during his first days[8] and succeeded Maxim Litvinov as ambassador to the United States in 1943. In his Memoirs Gromyko wrote fondly of President Franklin D. Roosevelt[9] even though he believed him to be a representative of the bourgeoisie class.[10] During his time as ambassador, Gromyko met prominent personalities such as British actor Charlie Chaplin,[11] and British economist John Maynard Keynes.[12]

كان گروميكو المبعوث السوڤيتي إلى مؤتمرات طهران و دمبارتون أوكس, يالطا و پوتسدام.[13] In 1943, the same year as the Tehran Conference, the USSR established diplomatic relations with Cuba and Gromyko was appointed the Soviet ambassador to Havana.[14] Gromyko claimed that the accusations brought against Roosevelt by American right-wingers, that he was a socialist sympathizer, were absurd.[15] While he started out as a member delegate Gromyko later became the head of the Soviet delegation to the مؤتمر سان فرانسسكو after Molotov's departure. When he later returned to Moscow to celebrate the Soviet victory in the Great Patriotic War, Stalin commended him saying a good diplomat was "worth two or three armies at the front".[16]

وفي عام 1944 كان جُروميكو رئيسًا للوفد السوفيتي إلى مؤتمر دومبارتون أوكس في واشنطن العاصمة، والذي ساهم في تأسيس أنظمة الأمم المتحدة. وابتداء من عام 1946 كان جُروميكو رئيساً للوفد السوڤيتي إلى الأمم المتحدة، وكثير من المؤتمرات الدولية. وأصبح جُروميكو يشتهر بمعارضته المتشددة للقوى الغربية. ومن يونيو 1952 إلى مايو 1953، عمل جروميكو سفيراً لدى بريطانيا، وكان نائباً لوزير الخارجية بين عامي 1947 و1952، ثم من عام 1953 إلى عام 1957.

وزير خارجية الاتحاد السوڤيتي

سافر جروميكو بوصفه وزيرًا للخارجية مع رئيس الوزراء نيكيتا خروشوف إلى الولايات المتحدة عام 1959. وفي عام 1961 شارك في الاجتماع بين خروشوف والرئيس جون ف. كنيدي في فيينا بالنمسا. وقاد فريق المفاوضات السوڤيتي الذي رتَّب لمعاهدة الحظر الجزئي للتجارب النووية مع بريطانيا والولايات المتحدة في موسكو عام 1963.

رأس الدولة والتقاعد والوفاة

الذكرى

الأوسمة

الاتحاد السوڤيتي:

الاتحاد السوڤيتي:

Hero of Socialist Labor, twice (1969, 1979)

Hero of Socialist Labor, twice (1969, 1979) Order of Lenin, seven times (1944, 1945, 1959, 1966, 1969, 1979, 1984)

Order of Lenin, seven times (1944, 1945, 1959, 1966, 1969, 1979, 1984) Order of the Patriotic War, 1st class (1985)

Order of the Patriotic War, 1st class (1985) Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1948)

Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1948) Order of the Badge of Honour (1954)

Order of the Badge of Honour (1954) Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (1969)

Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (1969) Jubilee Medal "Thirty Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1975)

Jubilee Medal "Thirty Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1975) Jubilee Medal "Forty Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1985)

Jubilee Medal "Forty Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1985) Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1945)

Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1945) Medal "Veteran of Labour" (1974)

Medal "Veteran of Labour" (1974) Jubilee Medal "70 Years of the Armed Forces of the USSR" (1988)

Jubilee Medal "70 Years of the Armed Forces of the USSR" (1988) Medal "In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow" (1947)

Medal "In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow" (1947) Lenin Prize (1982)

Lenin Prize (1982) USSR State Prize (1984)

USSR State Prize (1984)

- بلدان أخرى:

Order of the Sun of Freedom (Afghanistan)

Order of the Sun of Freedom (Afghanistan) Order of Georgi Dimitrov (Bulgaria)

Order of Georgi Dimitrov (Bulgaria) Order of José Martí (Cuba)

Order of José Martí (Cuba) Order of Klement Gottwald (Czechoslovakia)

Order of Klement Gottwald (Czechoslovakia) Order of the Flag of the Republic of Hungary (Hungary)

Order of the Flag of the Republic of Hungary (Hungary) Order of Peace and Friendship (Hungary)

Order of Peace and Friendship (Hungary) Grand Cross of Order of the Sun of Peru (Peru)

Grand Cross of Order of the Sun of Peru (Peru) Order of Merit of the Polish People's Republic, 1st class (Poland)

Order of Merit of the Polish People's Republic, 1st class (Poland)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الهامش

- ^ Соседи по парте (in Russian). RPP. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 35.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, pp. 36–7.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 39.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 40.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 41.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 42.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 43.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, pp. 48–9.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 50.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 73.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 82.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 88.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 89.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 95.

- ^ Gromyko 1989, p. 103.

للاستزادة

- Elliott, Gregory; Lewin, Moshe (2005). The Soviet Century. Verso Books. ISBN 1-84467-016-3.

- Hoffmann Jr., Erik P., and Frederic J. Fleron. The Conduct of Soviet Foreign Policy (1980)

- MacKenzie, David. From Messianism to Collapse: Soviet Foreign Policy 1917–1991 (1994)

- Stone, Norman. "Andrei Gromyko as Foreign Minister: The Problems of a Decaying Empire," in Gordon Craig and Francis Loewenheim, eds. The Diplomats 1939– 1979 (Princeton University Press, 1994)

- Ulam, Adam B. Expansion and Coexistence: Soviet Foreign Policy 1917–73 (1976)

المصادر الرئيسية

- Gromyko, Andrei (1989). Memoirs. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-41288-6.

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 uses الروسية-language script (ru)

- Pages using infobox officeholder with unknown parameters

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing بلاروسية-language text

- Articles with dead external links from October 2016

- مواليد 1909

- وفيات 1989

- People from Vietka District

- People from Mogilev Governorate

- Members of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union

- Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union members

- Soviet Ministers of Foreign Affairs

- Permanent Representatives of the Soviet Union to the United Nations

- سفراء الاتحاد السوڤيتي إلى المملكة المتحدة

- سفراء الاتحاد السوڤيتي إلى الولايات المتحدة

- سفراء الاتحاد السوڤيتي إلى كوبا

- دبلوماسيو الحرب الباردة

- Heads of state of the Soviet Union

- أبطال العمل الإشتراكي

- حائزو وسام لنين

- حائزو مرتبة الراية الحمراء

- Recipients of the Order of the Badge of Honour

- حائزو جائزة لنين

- حائزو جائزة الدولة للاتحاد السوڤيتي

- Recipients of the Order of José Marti

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Sun of Peru

- ملحدون بلاروس

- مدفونون في مقبرة نوڤوديڤيتشي

- رؤساء مجلس السوفييت الأعلى