آيوا

Iowa

Ayúȟwa (Lakota) | |

|---|---|

| State of Iowa | |

| الكنية: | |

| الشعار: Our liberties we prize and our rights we will maintain[1] | |

| النشيد: "The Song of Iowa" | |

خريطة الولايات المتحدة، موضح فيها Iowa | |

| البلد | الولايات المتحدة |

| انضمت للاتحاد | December 28, 1846 (29th) |

| العاصمة | دي موين |

| أكبر مدينة | العاصمة |

| أكبر منطقة عمرانية |

|

| الحكومة | |

| • الحاكم | Kim Reynolds (R) |

| • نائب الحاكم | Adam Gregg (R) |

| المجلس التشريعي | Iowa General Assembly |

| • المجلس العلوي | Senate |

| • المجلس السفلى | House of Representatives |

| القضاء | Iowa Supreme Court |

| سناتورات الولايات المتحدة | Chuck Grassley (R) Joni Ernst (R) |

| وفد مجلس النواب | 1: Mariannette Miller-Meeks (R) 2: Ashley Hinson (R) 3: Zach Nunn (R) 4: Randy Feenstra (R) (القائمة) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 56٬273 ميل² (145٬746 كم²) |

| • البر | 55٬857 ميل² (144٬669 كم²) |

| • الماء | 416 ميل² (1٬077 كم²) 0.70% |

| ترتيب المساحة | 26th |

| المنسوب | 1٬120 ft (340 m) |

| أعلى منسوب | 1٬670 ft (509 m) |

| التعداد (2022) | |

| • الإجمالي | {{{2٬000Pop}}} |

| • الترتيب | 30th |

| • الكثافة | 57٫1/sq mi (22٫1/km2) |

| • ترتيب الكثافة | 36th |

| • الدخل الأوسط للأسرة | $61٬691[4] |

| • ترتيب الدخل | 30th |

| صفة المواطن | Iowan |

| اللغة | |

| • اللغة الرسمية | English |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC−06:00 (Central) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| اختصار البريد | IA |

| ISO 3166 code | US-IA |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

علم Iowa | |

شعار Iowa | |

| الطائر | Eastern goldfinch |

|---|---|

| الزهرة | Prairie rose |

| الشجرة | Bur Oak |

| الصخر | Geode |

| علامة طريق ولائي | |

| |

| ربع دولار الولاية | |

طـُرِح في 2004 | |

| قوائم رموز الولايات الأمريكية | |

آيوا ( Iowa ؛ /ˈaɪ.əwə/ (![]() استمع) EYE-ə-wə, Lakota: Ayúȟwa)[5][6][7][8] هي ولاية تقع في أعلى منطقة الغرب الأوسط بالولايات المتحدة. ويحدها نهر المسيسپي من الشرق ونهرا مزوري وبيگ سو من الغرب، وولاية وسكنسن من الشمال الشرقي، وإلينوي من الشرق والجنوب الشرقي، ومزوري من الجنوب، ونبراسكا من الغرب، وداكوتا الجنوبية من الشمال الغربي، ومينيسوتا من الشمال.

استمع) EYE-ə-wə, Lakota: Ayúȟwa)[5][6][7][8] هي ولاية تقع في أعلى منطقة الغرب الأوسط بالولايات المتحدة. ويحدها نهر المسيسپي من الشرق ونهرا مزوري وبيگ سو من الغرب، وولاية وسكنسن من الشمال الشرقي، وإلينوي من الشرق والجنوب الشرقي، ومزوري من الجنوب، ونبراسكا من الغرب، وداكوتا الجنوبية من الشمال الغربي، ومينيسوتا من الشمال.

عاصمتها دي موين. مساحتها 145,743 كم2. عدد سكانها 2926324 نسمة (عام 2000). وهي مركز مهم للزراعة حيث تشكل المزارع أكثر من90% من منطقة أيوا. ويتألف المحصول الأساسي من الذرة وفول الصويا. وتُعدّ أيوا الولاية الأولى في الولايات المتحدة من حيث عدد الخنازير التي تربى للتسويق. كما أن دي موين، عاصمة أيوا ومدينتها الكبرى، هي مركز رئيسي للتأمين.

Iowa is the 26th largest in total area and the 31st most populous of the 50 U.S. states, with a population of 3,190,369,[9] according to the 2020 census. The state's capital, most populous city, and largest metropolitan area fully located within the state is Des Moines. A portion of the larger Omaha, Nebraska, metropolitan area extends into three counties of southwest Iowa.[10] Iowa has been listed as one of the safest U.S. states to live in.[11]

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, Iowa was a part of French Louisiana and Spanish Louisiana; its state flag is patterned after the flag of France. After the Louisiana Purchase, people laid the foundation for an agriculture-based economy in the heart of the Corn Belt.[12]

In the latter half of the 20th century, Iowa's agricultural economy began to transition to a diversified economy of advanced manufacturing, processing, financial services, information technology, biotechnology, and green energy production.[13][14] As of 2018, 22.6 million hogs outnumbered Iowans by more than 7 to 1 in 8,000 facilities large enough to require manure management plans.[15]

أصل الاسم

Like many other states, Iowa takes its name from its predecessor, Iowa Territory, whose name in turn is derived from the Iowa River, and ultimately from the ethnonym of the indigenous Ioway people. The Ioway are a Chiwere-speaking Siouan Nation, who were once part of the Ho-Chunk Confederation that inhabited the area now corresponding to several Midwest states. The Ioway were one of the many Native American nations whose territory comprised the future state of Iowa before the time of European colonization.[16]

التاريخ

وكانت منطقة أيوا في الماضي موطن هنود ما قبل التاريخ الذين يسمون بناة الهضاب. وفي عام 1673م كان المكتشف الفرنسي لويس جوليت والأب جاك ماركت أول من رأى المنطقة من البيض. وأعلنت فرنسا أن أيوا جزء من المنطقة الشاسعة المسماة لويزيانا، ثم أصبحت المنطقة جزءًا من الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية عام 1803م.

وقد بدأت المستوطنات الدائمة في منطقة أيوا في عام 1833، على أثر انهزام الهنود أمام جيش الولايات المتحدة في حرب الصقر الأسود. وقد أصبحت أيوا ولاية عام 1846.

وقد تطورت الملاحة البخارية إلى صناعة ضخمة على نهر المسيسيبي بين عامي 1850-1870م. وبحلول عام 1870م، اخترقت الولاية أربعة خطوط للسكك الحديدية. وفي أوائل القرن العشرين، وفرت السكك الحديدية فرصًا لأسواق جديدة للصناعات، كما وفرت السدود الجديدة الطاقة. وبين عام 1945م وأواخر الستينيات من القرن العشرين، انتقلت أيوا من الاعتماد على اقتصاد المزرعة إلى اقتصاد صناعي ـ زراعي. وقد أثر هبوط الأسعار المفاجئ ابتداء من أوائل الثمانينيات تأثيرًا خطيرًا في مستقبل الكثيرين في أيوا من سكان المدن الصغيرة والمناطق الريفية.

قبل التاريخ

When Indigenous peoples of the Americas first arrived in what is now Iowa more than 13,000 years ago, they were hunters and gatherers living in a Pleistocene glacial landscape. By the time European explorers and traders visited Iowa, Native Americans were largely settled farmers with complex economic, social, and political systems. This transformation happened gradually. During the Archaic period (10,500 to 2,800 years ago), Native Americans adapted to local environments and ecosystems, slowly becoming more sedentary as populations increased.[17]

More than 3,000 years ago, during the Late Archaic period, Native Americans in Iowa began utilizing domesticated plants. The subsequent Woodland period saw an increased reliance on agriculture and social complexity, with increased use of mounds, ceramics, and specialized subsistence. During the Late Prehistoric period (beginning about AD 900) increased use of maize and social changes led to social flourishing and nucleated settlements.[17]

The arrival of European trade goods and diseases in the Protohistoric period led to dramatic population shifts and economic and social upheaval, with the arrival of new tribes and early European explorers and traders. There were numerous native American tribes living in Iowa at the time of early European exploration. Tribes which were probably descendants of the prehistoric Oneota include the Dakota, Ho-Chunk, Ioway, and Otoe. Tribes which arrived in Iowa in the late prehistoric or protohistoric periods include the Illiniwek, Meskwaki, Omaha, and Sauk.[17]

الاستعمار المبكر والتجارة، 1673–1808

The first known European explorers to document Iowa were Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet who traveled the Mississippi River in 1673 documenting several Indigenous villages on the Iowa side.[18][19] The area of Iowa was claimed for France and remained a French territory until 1763. The French, before their impending defeat in the French and Indian War, transferred ownership to their ally, Spain.[20] Spain practiced very loose control over the Iowa region, granting trading licenses to French and British traders, who established trading posts along the Mississippi and Des Moines Rivers.[18]

Iowa was part of a territory known as La Louisiane or Louisiana, and European traders were interested in lead and furs obtained by Indigenous people. The Sauk and Meskwaki effectively controlled trade on the Mississippi in the late 18th century and early 19th century. Among the early traders on the Mississippi were Julien Dubuque, Robert de la Salle, and Paul Marin.[18] Along the Missouri River at least five French and English trading houses were built before 1808.[21] In 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte took control of Louisiana from Spain in a treaty.[22]

After the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, Congress divided the Louisiana Purchase into two parts—the Territory of Orleans and the District of Louisiana, with present-day Iowa falling in the latter. The Indiana Territory, created in 1800, exercised jurisdiction over this portion of the District; William Henry Harrison was its first governor. Much of Iowa was mapped by Zebulon Pike in 1805,[23] but it was not until the construction of Fort Madison in 1808 that the U.S. established tenuous military control over the region.[24]

حرب 1812 والسيطرة غير المستقرة للولايات المتحدة

Fort Madison was built to control trade and establish U.S. dominance over the Upper Mississippi, but it was poorly designed and disliked by the Sauk and Meskwaki, many of whom allied with the British, who had not abandoned claims to the territory.[24][25] Fort Madison was defeated by British-supported Indigenous people in 1813 during the War of 1812, and Fort Shelby in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, also fell to the British. Black Hawk took part in the siege of Fort Madison.[26][27] Another small military outpost was established along the Mississippi River in present-day Bellevue. This poorly situated stockade was similarly attacked by hundreds of Indigenous people in 1813, but was successfully defended and later abandoned until settlers returned to the area in the mid-1830s.[28]

After the war, the U.S. re-established control of the region through the construction of Fort Armstrong, Fort Snelling in Minnesota, and Fort Atkinson in Nebraska.[29]

إزالة الهنود، 1814–1832

The United States encouraged settlement of the east side of the Mississippi and removal of Indians to the west.[30] A disputed 1804 treaty between Quashquame and William Henry Harrison (then governor of the Indiana Territory) that surrendered much of Illinois to the U.S. enraged many Sauk and led to the 1832 Black Hawk War.[31]

The Sauk and Meskwaki sold their land in the Mississippi Valley during 1832 in the Black Hawk Purchase[32] and sold their remaining land in Iowa in 1842, most of them moving to a reservation in Kansas.[31] Many Meskwaki later returned to Iowa and settled near Tama, Iowa; the Meskwaki Settlement remains to this day. In 1856 the Iowa Legislature passed an unprecedented act allowing the Meskawki to purchase the land.[33] However, in contrast to the unprecedented act of the Iowa Legislature, the United States Federal Government, through the use of Treaties, forced the Ho-Chunk from Iowa in 1848,[34] and forced the Dakota from Iowa by 1858.[35] Western Iowa around modern Council Bluffs was used as an Indian Reservation for members of the Council of Three Fires.[36]

استيطان الولايات المتحدة وإشهار الولاية، 1832–1860

The first American settlers officially moved to Iowa in June 1833.[37] Primarily, they were families from Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Indiana, Kentucky, and Virginia who settled along the western banks of the Mississippi River, founding the modern day cities of Dubuque and Bellevue.[37][38] On July 4, 1838, the U.S. Congress established the Territory of Iowa. President Martin Van Buren appointed Robert Lucas governor of the territory, which at the time had 22 counties and a population of 23,242.[39]

Almost immediately after achieving territorial status, a clamor arose for statehood. On December 28, 1846, Iowa became the 29th state in the Union when President James K. Polk signed Iowa's admission bill into law. Once admitted to the Union, the state's boundary issues resolved, and most of its land purchased from Natives, Iowa set its direction to development and organized campaigns for settlers and investors, boasting the young frontier state's rich farmlands, fine citizens, free and open society, and good government.[40]

Iowa has a long tradition of state and county fairs. The first and second Iowa State Fairs were held in the more developed eastern part of the state at Fairfield. The first fair was held October 25–27, 1854, at a cost of around $323. Thereafter, the fair moved to locations closer to the center of the state and in 1886 found a permanent home in Des Moines. The State Fair has been held annually since then, except for a few exceptions: 1898 due to the Spanish–American War and the World's Fair being held in nearby Omaha, Nebraska; from 1942 to 1945, due to World War II, as the fairgrounds were being used as an army supply depot; and in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.[41][42]

الحرب الأهلية، 1861–1865

Iowa supported the Union during the Civil War, voting heavily for Abraham Lincoln, though there was an antiwar "Copperhead" movement in the state, caused partially by a drop in crop prices caused by the war.[43] There were no battles in the state, although the Battle of Athens, Missouri, 1861, was fought just across the Des Moines River from Croton, Iowa, and shots from the battle landed in Iowa. Iowa sent large supplies of food to the armies and the eastern cities.[44]

Much of Iowa's support for the Union can be attributed to Samuel J. Kirkwood, its first wartime governor. Of a total population of 675,000, about 116,000 men were subjected to military duty. Iowa contributed proportionately more soldiers to Civil War military service than did any other state, north or south, sending more than 75,000 volunteers to the armed forces, over one-sixth of whom were killed before the Confederates surrendered at Appomattox.[44]

Most fought in the great campaigns in the Mississippi Valley and in the South.[45] Iowa troops fought at Wilson's Creek in Missouri, Pea Ridge in Arkansas, Forts Henry and Donelson, Shiloh, Chattanooga, Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge, and Rossville Gap as well as Vicksburg, Iuka, and Corinth. They served with the Army of the Potomac in Virginia and fought under Union General Philip Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley. Many died and were buried at Andersonville. They marched on General Nathaniel Banks' ill-starred expedition to the Red River. Twenty-seven Iowans have been awarded the Medal of Honor, the highest military decoration awarded by the United States government, which was first awarded in the Civil War.[46]

Iowa had several brigadier generals and four major generals—Grenville Mellen Dodge, Samuel R. Curtis, Francis J. Herron, and Frederick Steele—and saw many of its generals go on to state and national prominence following the war.[44]

التوسع الزراعي، 1865–1930

Following the Civil War, Iowa's population continued to grow dramatically, from 674,913 people in 1860[47] to 1,624,615 in 1880.[48] The American Civil War briefly brought higher profits.[49]

In 1917, the United States entered World War I and farmers as well as all Iowans experienced a wartime economy. For farmers, the change was significant. Since the beginning of the war in 1914, Iowa farmers had experienced economic prosperity, which lasted until the end of the war.[49] In the economic sector, Iowa also has undergone considerable change. Beginning with the first industries developed in the 1830s,[50] which were mainly for processing materials grown in the area,[51] Iowa has experienced a gradual increase in the number of business and manufacturing operations.

الكساد، الحرب العالمية الثانية والتصنيع، 1930–1985

The transition from an agricultural economy to a mixed economy happened slowly. The Great Depression and World War II accelerated the shift away from smallholder farming to larger farms, and began a trend of urbanization. The period after World War II witnessed a particular increase in manufacturing operations.[52]

In 1975, Governor Robert D. Ray petitioned President Ford to allow Iowa to accept and resettle Tai Dam refugees fleeing the Indochina War.[53] An exception was required for this resettlement as State Dept policy at the time forbid resettlement of large groups of refugees in concentrated communities; an exception was ultimately granted and 1200 Tai Dam were resettled in Iowa. Since then Iowa has accepted thousands of refugees from Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Bhutan, and Burma.[54]

The farm crisis of the 1980s caused a major recession in Iowa, causing poverty not seen since the Depression.[55] The crisis spurred a major, decade-long population decline.[56]

Reemergence as a mixed economy, 1985–present

After bottoming out in the 1980s, Iowa's economy began to reduce its dependence on agriculture. By the early 21st century, it was characterized by a mix of manufacturing, biotechnology, finance and insurance services, and government services.[57] The population of Iowa has increased at a slower rate than the U.S. as a whole since at least the 1900 census,[58] though Iowa now has a predominantly urban population.[59] The Iowa Economic Development Authority, created in 2011 has replaced the Iowa Department of Economic Development and its annual reports are a source of economic information.[60]

الجغرافيا

مقالة مفصلة: جغرافيا آيوا

مقالة مفصلة: جغرافيا آيوا

تجاور ولاية آيوا الأمريكية من الشمال ولاية مينيسوتا، ومن الغرب نبراسكا وداكوتا الجنوبية، ومن الجنوب ميزوري، ومن الشرق ويسكنسن وإلينوي.

يمثل نهر مسيسيبي الحدود الشرقية للولاية. بينما تتمثل الحدود الغربية بنهر ميزوري جنوب سو سيتي وكذلك نهر سو الكبير شمال المدينة. هناك عدة بحيرات طبيعية في الولاية، أشهرها سبيريت ليك، وبحيرة أوكوبوجي الغربية والشرقية في شمال غرب آيوا. وهناك بحيرات مصطنعة مثل بحيرة أوديسا، وبحيرة سيلورفل، وليك ريد روك، وبحيرة راذبن.

النقطة الأكثر انخفاضاً في آيوا هي كيوكك في جنوب شرق الولاية (146 متر)، وأعلى ارتفاع في الولاية هو 509 متر وهو نقطة هوكاي شمال مدينة سيبلي، شمال غرب الولاية.

وخلال العصر الجليدي، غطت المثالج السهول الغنية التي تشكل القسم الأعظم من أيوا. وتمتد سهول الطين القاسي المجزأة على مدى القطاع الجنوبي من الولاية بأكمله، وتصل إلى الزاوية الشمالية الغربية. وقد تركت المثالج التي شكلت المنطقة كميات هائلة من الطين القاسي (طبقات من التراب والحجر). وقد جزأت الجداول السهول، وشكلت تلالاً متعاقبة وسلاسل حادة.

وتغطي سهول الركام الحديثة معظم شمالي أيوا ووسطها. وقد مهدت المثالج سطح هذه المنطقة بدقة وتركت ركامًا عميقًا من التراب والصخور إما على شكل طبقات وإما دون تصنيف. وقد أصبح هذا الركام تربة خصبة من الدرجة الأولى. وتوجد تلال وصخور حادة مغطاة بالصنوبر على امتداد المنطقة الخالية من الركام في الشمال الشرقي من أيوا. وتشكل مياه مجرى نهر المسيسيبي ـ ميسوري ـ الجبار حدود أيوا الشرقية والغربية.

الحدود

Iowa is bordered by the Mississippi River on the east along with the Missouri River and the Big Sioux River on the west. The northern boundary is a line along 43 degrees, 30 minutes north latitude.[61][ب] The southern border is the Des Moines River and a not-quite-straight line along approximately 40 degrees 35 minutes north, as decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in Missouri v. Iowa (1849) after a standoff between Missouri and Iowa known as the Honey War.[62][63]

Iowa is the only state whose east and west borders are formed almost entirely by rivers.[64] Carter Lake, Iowa, is the only city in the state located west of the Missouri River.[65]

Iowa has 99 counties, but 100 county seats because Lee County has two. The state capital, Des Moines, is in Polk County.[66]

الجيولوجيا والتضاريس

Iowa's bedrock geology generally decreases in age from east to west. In northwest Iowa, Cretaceous bedrock can be 74 million years old; in eastern Iowa Cambrian bedrock dates to c. 500 million years ago.[67] The oldest radiometrically dated bedrock in the state is the 2.9 billion year old Otter Creek Layered Mafic Complex. Precambrian rock is exposed only in the northwest of the state.[68]

Iowa can be divided into eight landforms based on glaciation, soils, topography, and river drainage.[69] Loess hills lie along the western border of the state, some of which are several hundred feet thick.[70] Northeast Iowa along the Upper Mississippi River is part of the Driftless Area, consisting of steep hills and valleys which appear as mountainous.[71]

Several natural lakes exist, most notably Spirit Lake, West Okoboji Lake, and East Okoboji Lake in northwest Iowa (see Iowa Great Lakes). To the east lies Clear Lake. Man-made lakes include Lake Odessa,[72] Saylorville Lake, Lake Red Rock, Coralville Lake, Lake MacBride, and Rathbun Lake. Before European settlement, 4 to 6 million acres of the state was covered with wetlands, about 95% of these wetlands have been drained.[73]

البيئة

Iowa's natural vegetation is tallgrass prairie and savanna in upland areas, with dense forest and wetlands in flood plains and protected river valleys, and pothole wetlands in northern prairie areas.[69] Most of Iowa is used for agriculture; crops cover 60% of the state, grasslands (mostly pasture and hay with some prairie and wetland) cover 30%, and forests cover 7%; urban areas and water cover another 1% each.[74]

The southern part of Iowa is categorized as the Central forest-grasslands transition ecoregion.[75] The Northern, drier part of Iowa is categorized as part of the Central tall grasslands.[76]

There is a dearth of natural areas in Iowa; less than 1% of the tallgrass prairie that once covered most of Iowa remains intact; only about 5% of the state's prairie pothole wetlands remain, and most of the original forest has been lost.[77] اعتبارا من 2005[تحديث] Iowa ranked 49th of U.S. states in public land holdings.[78] Threatened or endangered animals in Iowa include the interior least tern, piping plover, Indiana bat, pallid sturgeon, the Iowa Pleistocene land snail, Higgins' eye pearly mussel, and the Topeka shiner.[79] Endangered or threatened plants include western prairie fringed orchid, eastern prairie fringed orchid, Mead's milkweed, prairie bush clover, and northern wild monkshood.[80]

The explosion in the number of high-density livestock facilities in Iowa has led to increased rural water contamination and a decline in air quality.[81]

Other factors negatively affecting Iowa's environment include the extensive use of older coal-fired power plants,[82] fertilizer and pesticide runoff from crop production,[83] and diminishment of the Jordan Aquifer.[84]

The 2020–2023 North American drought has affected Iowa particularly: As of January 2024, Iowa was in its 187th consecutive week of at least moderate drought, the longest stretch since the 1950s. 96% of areas are affected by drought.[85]

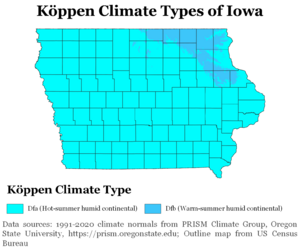

المناخ

Iowa has a humid continental climate throughout the state (Köppen climate classification Dfa) with extremes of both heat and cold. The average annual temperature at Des Moines is 50 °F (10 °C); for some locations in the north, such as Mason City, the figure is about 45 °F (7 °C), while Keokuk, on the Mississippi River, averages 52 °F (11 °C).[86] Snowfall is common, with Des Moines getting about 26 days of snowfall a year, and other places, such as Shenandoah getting about 11 days of snowfall in a year.[87]

Spring ushers in the beginning of the severe weather season. As of 2008, Iowa averaged about 50 days of thunderstorm activity per year.[88] As of 2015, the 30-year annual average of tornadoes in Iowa was 47.[89] In 2008, twelve people were killed by tornadoes in Iowa, making it the deadliest year since 1968 and also the second most tornadoes in a year with 105, matching the total from 2001.[90]

Iowa summers are known for heat and humidity, with daytime temperatures sometimes near 90 °F (32 °C) and occasionally exceeding 100 °F (38 °C). Average winters in the state have been known to drop well below freezing, even dropping below −18 °F (−28 °C). As of 2018, Iowa's all-time hottest temperature of 118 °F (48 °C) was recorded at Keokuk on July 20, 1934, during a nationwide heat wave;[91] as of 2014, the all-time lowest temperature of −47 °F (−44 °C) was recorded in Washta on January 12, 1912.[92]

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davenport[94] | 30/13 | 36/19 | 48/29 | 61/41 | 72/52 | 81/63 | 85/68 | 83/66 | 76/57 | 65/45 | 48/32 | 35/20 |

| Des Moines[95] | 31/14 | 36/19 | 49/30 | 62/41 | 72/52 | 82/62 | 86/67 | 84/65 | 76/55 | 63/43 | 48/31 | 34/18 |

| Keokuk[96] | 34/17 | 39/21 | 50/30 | 63/42 | 73/52 | 83/62 | 87/67 | 85/65 | 78/56 | 66/44 | 51/33 | 33/21 |

| Mason City[97] | 24/6 | 29/12 | 41/23 | 57/35 | 69/46 | 79/57 | 82/61 | 80/58 | 73/49 | 60/37 | 43/25 | 28/11 |

| Sioux City[98] | 31/10 | 35/15 | 47/26 | 62/37 | 73/49 | 82/59 | 86/63 | 83/63 | 76/51 | 63/38 | 46/25 | 32/13 |

الهطل

Iowa has had a relatively smooth gradient of varying precipitation across the state; from 1961 to 1990, areas in the southeast of the state received an average of over 38 بوصات (97 cm) of rain annually, and the northwest of the state receiving less than 28 بوصات (71 cm).[99] The pattern of precipitation across Iowa is seasonal with more rain falling in the summer months. Virtually statewide, the driest month is January or February, and the wettest month is June owing to frequent showers and thunderstorms some of which produce hail, damaging winds or tornadoes. In Des Moines, roughly in the center of the state, over two-thirds of the 34.72 بوصات (88.2 cm) of rain falls from April through September, and about half the average annual precipitation falls from May through August peaking in June.[100]

التجمعات

Iowa's population is more urban than rural, with 61 percent living in urban areas in 2000, a trend that began in the early 20th century.[59] Urban counties in Iowa grew 8.5% from 2000 to 2008, while rural counties declined by 4.2%.[102] The shift from rural to urban has caused population increases in more urbanized counties such as Dallas, Johnson, Linn, Polk, and Scott, at the expense of more rural counties.[103]

Iowa, in common with other Midwestern states (especially Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota), is feeling the brunt of rural flight, although Iowa has been gaining population since approximately 1990. Some smaller communities, such as Denison and Storm Lake, have mitigated this population loss through gains in immigrant laborers.[104]

Another demographic problem for Iowa is the brain drain, in which educated young adults leave the state in search of better prospects in higher education or employment. During the 1990s, Iowa had the second highest exodus rate for single, educated young adults, second only to North Dakota.[105]

| الترتيب | المدينة | 2020 city population[106] | 2010 city population[107] | Change | Metropolitan Statistical Area | 2020 metro population[108] | 2010 metro population | 2020 metro change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | دي موين | 214٬133 | 203٬433 | +5٫26% | Des Moines–West Des Moines | 707٬915 | 606٬475 | +16٫73% |

| 2 | سيدر راپيدز | 137٬710 | 126٬326 | +9٫01% | Cedar Rapids | 273٬885 | 257٬940 | +6٫18% |

| 3 | Davenport | 101٬724 | 99٬685 | +2٫05% | Quad Cities | 382٬268 | 379٬690 | +0٫68% |

| 4 | Sioux City | 85٬797 | 82٬684 | +3٫76% | Sioux City | 144٬996 | 143٬577 | +0٫99% |

| 5 | Iowa City | 74٬828 | 67٬862 | +10٫26% | Iowa City | 175٬732 | 152٬586 | +15٫17% |

| 6 | West Des Moines | 68٬723 | 56٬609 | +21٫40% | Des Moines–West Des Moines | |||

| 7 | Ankeny | 67٬887 | 45٬582 | +48٫93% | Des Moines–West Des Moines | |||

| 8 | Waterloo | 67٬314 | 68٬406 | −1٫60% | Waterloo–Cedar Falls | 168٬314 | 167٬819 | +0٫29% |

| 9 | Ames | 66٬427 | 58٬965 | +12٫65% | Ames | 124٬514 | 115٬848 | +7٫48% |

| 10 | Council Bluffs | 62٬799 | 62٬230 | +0٫91% | Omaha–Council Bluffs | 954٬270 | 865٬350 | +10٫28% |

| 11 | دبيوك | 59٬667 | 57٬637 | +3٫52% | دبيوك | 97٬590 | 93٬653 | +4٫20% |

| 12 | Urbandale | 45٬580 | 39٬463 | +15٫50% | Des Moines–West Des Moines | |||

| 13 | ماريون | 41٬535 | 34٬768 | +19٫46% | Cedar Rapids | |||

| 14 | Cedar Falls | 40٬713 | 39٬260 | +3٫70% | Waterloo–Cedar Falls | |||

| 15 | Bettendorf | 39٬102 | 33٬217 | +17٫72% | Quad Cities |

السكان

التعداد

| التعداد | Pop. | ملاحظة | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 43٬112 | — | |

| 1850 | 192٬214 | 345٫8% | |

| 1860 | 674٬913 | 251٫1% | |

| 1870 | 1٬194٬020 | 76٫9% | |

| 1880 | 1٬624٬615 | 36٫1% | |

| 1890 | 1٬912٬297 | 17٫7% | |

| 1900 | 2٬231٬853 | 16٫7% | |

| 1910 | 2٬224٬771 | −0٫3% | |

| 1920 | 2٬404٬021 | 8٫1% | |

| 1930 | 2٬470٬939 | 2٫8% | |

| 1940 | 2٬538٬268 | 2٫7% | |

| 1950 | 2٬621٬073 | 3٫3% | |

| 1960 | 2٬757٬537 | 5٫2% | |

| 1970 | 2٬824٬376 | 2٫4% | |

| 1980 | 2٬913٬808 | 3٫2% | |

| 1990 | 2٬776٬755 | −4٫7% | |

| 2000 | 2٬926٬324 | 5٫4% | |

| 2010 | 3٬046٬355 | 4٫1% | |

| 2020 | 3٬190٬369 | 4٫7% | |

| 2022 (تق.) | 3٬200٬517 | 0٫3% | |

| Source: 1910–2020[58] | |||

The United States Census Bureau determined the population of Iowa was 3,190,369 on April 1, 2020, a 4.73% increase since the 2010 United States census.[109][110]

Of the residents of Iowa, 70.8% were born in Iowa, 23.6% were born in a different U.S. state, 0.6% were born in Puerto Rico, U.S. Island areas, or born abroad to American parent(s), and 5% were foreign born.[111]

Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 29,386 people, while migration within the country produced a net loss of 41,140 people. 6.5% of Iowa's population were reported as under the age of five, 22.6% under 18, and 14.7% were 65 or older. Males made up approximately 49.6% of the population.[112] The population density of the state is 52.7 people per square mile.[113] As of the 2010 census, the center of population of Iowa is in Marshall County, near Melbourne.[114] The top countries of origin for Iowa's immigrants in 2018 were Mexico, India, Vietnam, China and Thailand.[115]

Germans are the largest ethnic group in Iowa. Other major ethnic groups in Iowa include Irish people and the British. There are also Dutch communities in state. The Dutch can be found in Pella, in the centre of the state, and in Orange City, in the northwest. There is a Norwegian community in Decorah in northeast Iowa; and there is Czech and Slovak communities in both Cedar Rapids and Iowa City. Smaller numbers of Greeks and Italians are scattered in Iowa's metropolitan areas. The majority of Hispanics in Iowa are Mexican. African Americans, who constitute around 2% of Iowa's population, didn't live in the state in any appreciable numbers until the early 20th century. Many blacks worked in the coal-mining industry of southern Iowa. Others blacks migrated to Waterloo, Davenport, and Des Moines, where the black population remained substantial in the early 21st century.[116] The African-American population in Des Moines experienced a significant increase with the establishment of the Colored Officers Training Camp at Fort Des Moines in 1917. Following the conclusion of World War I in 1918, numerous African-American families made the decision to remain in Des Moines. This marked the inception of a thriving community that eventually became a residence for numerous African-American leaders.[117]

As of the 2010 census, the population of Iowa was 3,046,355. The gender makeup of the state was 49.5% male and 50.5% female. 23.9% of the population were under the age of 18; 61.2% were between the ages of 18 and 64; and 14.9% were 65 years of age or older.[118]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 2,419 homeless people in Iowa.[119][120]

| Race and Ethnicity[121] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 82.7% | 85.9% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[ت] | — | 6.8% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 4.1% | 5.2% | ||

| Asian | 2.4% | 3.0% | ||

| Native American | 0.3% | 1.4% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.2% | 0.3% | ||

| Other | 0.3% | 1.0% | ||

| التركيب العرقي | 1990[122] | 2000[123] | 2010[124] |

|---|---|---|---|

| بيض | 96.6% | 93.9% | 91.3% |

| Black or African American | 1.7% | 2.1% | 2.9% |

| Native American | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.4% |

| Asian | 0.9% | 1.3% | 1.7% |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | — | — | 0.1% |

| Other race | 0.5% | 1.3% | 1.8% |

| Two or more races | — | 1.1% | 1.8% |

According to the 2016 American Community Survey, 5.6% of Iowa's population were of Hispanic or Latino origin (of any race): Mexican (4.3%), Puerto Rican (0.2%), Cuban (0.1%), and other Hispanic or Latino origin (1.0%).[125] The five largest ancestry groups were: German (35.1%), Irish (13.5%), English (8.2%), American (5.8%), and Norwegian (5.0%).[126]

بيانات المواليد

Note: Births in table don't add up, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| العرق | 2013[127] | 2014[128] | 2015[129] | 2016[130] | 2017[131] | 2018[132] | 2019[133] | 2020[134] | 2021[135] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | 32,302 (82.6%) | 32,423 (81.7%) | 32,028 (81.1%) | 31,376 (79.6%) | 30,010 (78.1%) | 29,327 (77.6%) | 29,050 (77.2%) | 27,542 (76.3%) | 28,167 (76.5%) |

| Black | 2,232 (5.7%) | 2,467 (6.2%) | 2,597 (6.6%) | 2,467 (6.3%) | 2,657 (6.9%) | 2,615 (6.9%) | 2,827 (7.5%) | 2,685 (7.4%) | 2,567 (7.0%) |

| Asian | 1,353 (3.5%) | 1,408 (3.5%) | 1,364 (3.4%) | 1,270 (3.2%) | 1,321 (3.4%) | 1,176 (3.1%) | 1,106 (2.9%) | 1,067 (2.9%) | 1,055 (2.9%) |

| Native American | 269 (0.7%) | 284 (0.7%) | 242 (0.6%) | 147 (0.4%) | 311 (0.8%) | 152 (0.4%) | 308 (0.8%) | 143 (0.4%) | 129 (0.3%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 3,175 (8.1%) | 3,315 (8.3%) | 3,418 (8.6%) | 3,473 (8.8%) | 3,527 (9.2%) | 3,694 (9.8%) | 3,695 (9.8%) | 3,725 (10.3%) | 3,903 (10.6%) |

| Total Iowa | 39,094 (100%) | 39,687 (100%) | 39,482 (100%) | 39,403 (100%) | 38,430 (100%) | 37,785 (100%) | 37,649 (100%) | 36,114 (100%) | 36,835 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

الدين

Religious self-identification, per Public Religion Research Institute's 2022 American Values Survey[136]

A 2014 survey by Pew Research Center found 60% of Iowans are Protestant, while 18% are Catholic, and 1% are of non-Christian religions. 21% responded with non-religious, and 1% did not answer.[137][138] A survey from the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) in 2010 found that the largest Protestant denominations were the United Methodist Church with 235,190 adherents and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America with 229,557. The largest non-Protestant religion was Catholicism with 503,080 adherents. The state has a great number of Calvinist denominations. The Presbyterian Church (USA) had almost 290 congregations and 51,380 members followed by the Reformed Church in America with 80 churches and 40,000 members, and the United Church of Christ had 180 churches and 39,000 members.[139] According to the 2020 Public Religion Research Institute's study, 26% of the population were irreligious.[140]

The study Religious Congregations & Membership: 2000[141] found in the southernmost two tiers of Iowa counties and in other counties in the center of the state, the largest religious group was the United Methodist Church; in the northeast part of the state, including Dubuque and Linn counties (where Cedar Rapids is located), the Catholic Church was the largest; and in ten counties, including three in the northern tier, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America was the largest. The study also found rapid growth in Evangelical Christian denominations. Dubuque is home to the Archdiocese of Dubuque, which serves as the ecclesiastical province for all three other dioceses in the state and for all the Catholics in the entire state of Iowa.

Historically, religious sects and orders who desired to live apart from the rest of society established themselves in Iowa, such as the Amish and Mennonite near Kalona and in other parts of eastern Iowa such as Davis County and Buchanan County.[142] Other religious sects and orders living apart include Quakers around West Branch and Le Grand, German Pietists who founded the Amana Colonies, followers of Transcendental Meditation who founded Maharishi Vedic City, and Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance monks and nuns at the New Melleray and Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbeys near Dubuque.

By 1878, approximately 1000 Jewish people lived in Iowa, many of whom were immigrants from Poland and Germany.[143][144] اعتبارا من 2016[تحديث] about 6,000 Jews live in Iowa, with about 3,000 of them in Des Moines.[145]

اللغة

English is the most common language in Iowa, being the sole language spoken by 91.1% of the population. Less common languages include sign language and indigenous languages. About 2.5% of the general population use sign language as of 2017, while indigenous languages are spoken by about 0.5% of the population.[146] William Labov and colleagues, in the monumental Atlas of North American English[147] found the English spoken in Iowa divides into multiple linguistic regions. Natives of northern Iowa—including Sioux City, Fort Dodge, and the Waterloo region—tend to speak the dialect linguists call North Central American English, which is also found in North and South Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. Natives of central and southern Iowa—including such cities as Council Bluffs, Davenport, Des Moines, and Iowa City—tend to speak the North Midland dialect also found in eastern Nebraska, central Illinois, and central Indiana.[148] Natives of East-Central Iowa—including cities such as Cedar Rapids, Dubuque, and Clinton tend to speak with the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, a dialect that extends from this area and east across the Great Lakes Region.[149]

After English, Spanish is the second-most-common language spoken in Iowa, with 120,000 people in Iowa of Hispanic or Latino origin and 47,000 people born in Latin America.[150] The third-most-common language is German, spoken by 17,000 people in Iowa; two notable German dialects used in Iowa include Amana German spoken around the Amana Colonies, and Pennsylvania German, spoken among the Amish in Iowa. The Babel Proclamation of 1918 banned the speaking of German in public. Around Pella, residents of Dutch descent once spoke the Pella Dutch dialect.

الإقتصاد

تقدم الصناعة جزءًا كبيرًا من إنتاج أيوا الاقتصادي. وتنتج صناعات الولاية الكثير من البضائع ذات الصلة بالزراعة. وتُعدّ دافنبورت، ودي موين، ودوبيوك، وكذلك ووترلو مراكز إنتاج رئيسية للآلات الزراعية. وفي العديد من مدن أيوا توجد معامل ضخمة لتعبئة اللحوم. ويحتل تجهيز منتجات الخنزير ونقانق الإفطار أهمية خاصة. وفي مدينة سيدر رابيدز طاحونة ضخمة للحبوب. وتقوم المعامل في جميع أنحاء أيوا بتجهيز منتجات الألبان.

وتوظف تجارة الجملة والتجزئة من أهل أيوا أكثر مما توظف أية صناعة أخرى. وتُعدّ داي موين المركز الأول لتجارة المفرق. وترتكز تجارة الجملة على توزيع المركبات الآلية والمنتجات الزراعية. وداي موين مركز مالي أساسي لغربي الولايات المتحدة ووسطها، ولا سيما فيما يتصل بالتأمين.

وأيوا هي الولاية الأولى المنتجة للخنازير في الولايات المتحدة، وتحتل الخنازير المرتبة الأولى في إنتاجها الزراعي. وهي أيضًا منتج أساسي للذرة الشامية، وفول الصويا، وقطعان البقر. وكثير مما ينتج في أيوا من الذرة الصفراء وفول الصويا يستخدم لتغذية الحيوان.

- In 2016,[152] the total employment of the state's population was 1,354,487, and the total number of employer establishments was 81,563.

CNBC's list of "Top States for Business in 2010" has recognized Iowa as the sixth best state in the nation. Scored in 10 individual categories, Iowa was ranked first when it came to the "Cost of Doing Business"; this includes all taxes, utility costs, and other costs associated with doing business. Iowa was also ranked 10th in "Economy", 12th in "Business Friendliness", 16th in "Education", 17th in both "Cost of Living" and "Quality of Life", 20th in "Workforce", 29th in "Technology and Innovation", 32nd in "Transportation" and the lowest ranking was 36th in "Access to Capital".[153]

While Iowa is often viewed as a farming state, agriculture is a relatively small portion of the state's diversified economy, with manufacturing, biotechnology, finance and insurance services, and government services contributing substantially to Iowa's economy.[57] This economic diversity has helped Iowa weather the late 2000s recession better than most states, with unemployment substantially lower than the rest of the nation.[154][155]

If the economy is measured by gross domestic product, in 2005 Iowa's GDP was about $124 billion.[156] If measured by gross state product, for 2005 it was $113.5 billion.[157] Its per capita income for 2006 was $23,340.[157]

On July 2, 2009, Standard & Poor's rated the state of Iowa's credit as AAA (the highest of its credit ratings, held by only 11 U.S. state governments).[158]

As of September 2021, the state's unemployment rate is 4.0%.[159]

التصنيع

Manufacturing is the largest sector of Iowa's economy, with $20.8 billion (21%) of Iowa's 2003 gross state product. Major manufacturing sectors include food processing, heavy machinery, and agricultural chemicals. Sixteen percent of Iowa's workforce is dedicated to manufacturing.[57] Food processing is the largest component of manufacturing. Besides processed food, industrial outputs include machinery, electric equipment, chemical products, publishing, and primary metals. Companies with direct or indirect processing facilities in Iowa include ConAgra Foods, Wells Blue Bunny, Barilla, Heinz, Tone's Spices, General Mills, and Quaker Oats. Meatpacker Tyson Foods has 11 locations, second only to its headquarter state Arkansas.[160]

Major non-food manufacturing firms with production facilities in Iowa include 3M,[161] Arconic,[162] Amana Corporation,[163] Emerson Electric,[164] The HON Company,[165] SSAB,[166] John Deere,[167] Lennox Manufacturing,[168] Pella Corporation,[169] Procter & Gamble,[170] Vermeer Company,[171] and Winnebago Industries.[172]

الزراعة

Industrial-scale, commodity agriculture predominates in much of the state. Iowa's main conventional agricultural commodities are hogs, with about 22.6 million hogs in 8,000 facilities large enough to require manure management plans in March 2018, outnumbering Iowans by more than 7 to 1,[15] corn, soybeans, oats, cattle, eggs, and dairy products. Iowa is the nation's largest producer of ethanol and corn and some years is the largest grower of soybeans. In 2008, the 92,600 farms in Iowa produced 19% of the nation's corn, 17% of the soybeans, 30% of the hogs, and 14% of the eggs.[173] اعتبارا من 2009[تحديث] major Iowa agricultural product processors included Archer Daniels Midland, Cargill, Inc., Diamond V Mills, and Quaker Oats.[174]

During the 21 st century Iowa has seen growth in the organic farming sector. Iowa ranks fifth in the nation in total number of organic farms. In 2016, there were about 732 organic farms in the state, an increase of about 5% from the previous year, and 103,136 organic acres, an increase of 9,429 from the previous year.[175][176] Iowa has also seen an increase in demand for local, sustainably-grown food. Northeast Iowa, part of the Driftless Area, has led the state in development of its regional food system and grows and consumes more local food than any other region in Iowa.[177][178]

Iowa's Driftless Region is also home to the nationally recognized Seed Savers Exchange, a non-profit seed bank housed at an 890-acre heritage farm near Decorah, in the northeast corner of the state.[179][180] The largest nongovernmental seed bank of its kind in the United States, Seed Savers Exchange safeguards more than 20,000 varieties of rare, heirloom seeds.[181]

As of 2007, the direct production and sale of conventional agricultural commodities contributed only about 3.5% of Iowa's gross state product.[183] In 2002 the impact of the indirect role of agriculture in Iowa's economy, including agriculture-affiliated business, was calculated at 16.4% in terms of value added and 24.3% in terms of total output. This was lower than the economic impact of non-farm manufacturing, which accounted for 22.4% of total value added and 26.5% of total output.[184]

التأمين الصحي

As of 2014, there were 16 organizations offering health insurance products in Iowa, per the State of Iowa Insurance Division.[185] Iowa was fourth out of ten states with the biggest drop in competition levels of health insurance between 2010 and 2011, per the 2013 annual report on the level of competition in the health insurance industry by the American Medical Association[186] using 2011 data from HealthLeaders-Interstudy, the most comprehensive source of data on enrollment in health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), point-of-service (POS) and consumer-driven health care plans.[187] According to the AMA annual report from 2007 Wellmark Blue Cross Blue Shield had provided 71% of the state's health insurance.[188]

The Iowa Insurance Division "Annual report to the Iowa Governor and the Iowa Legislature" from November 2014 looked at the 95% of health insurers by premium, which are 10 companies. It found Wellmark Inc. to dominate the three health insurance markets it examined (individual, small group and large group) at 52–67%.[189] Wellmark HealthPlan of Iowa and Wellmark Inc had the highest risk-based capital percentages of all 10 providers at 1158% and 1132%, respectively.[189] Rising RBC is an indication of profits.[189]

القطاعات الأخرى

Iowa has a strong financial and insurance sector, with approximately 6,100 firms,[57] including AEGON, Nationwide Group, Aviva USA, Farm Bureau Financial Services, GreatAmerica Financial Services, Voya Financial, Marsh Affinity Group, MetLife, Principal Financial Group, Principal Capital Management, Wells Fargo, and Greenstate Credit Union (formerly University of Iowa Community Credit Union).

Iowa is host to at least two business incubators, Iowa State University Research Park and the BioVentures Center at the University of Iowa.[190] The Research Park hosts about 50 companies, among them NewLink Genetics, which develops cancer immunotherapeutics, and the U.S. animal health division of Boehringer Ingelheim, Vetmedica.[190]

Ethanol production consumes about a third of Iowa's corn production, and renewable fuels account for eight percent of the state's gross domestic product. A total of 39 ethanol plants produced 3.1 billion غالون أمريكي (12،000،000 m3) of fuel in 2009.[191]

Renewable energy has become a major economic force in northern and western Iowa, with wind turbine electrical generation increasing exponentially since 1990.[14] In 2019, wind power in Iowa accounted for 42% of electrical energy produced, and 10,201 megawatts of generating capacity had been installed at the end of the year.[192] Iowa ranked first of U.S. states in percentage of total power generated by wind and second in wind generating capacity behind Texas.[192] Major producers of turbines and components in Iowa include Acciona Energy of West Branch, TPI Composites of Newton, and Siemens Energy of Fort Madison.

In 2016, Iowa was the headquarters for three of the top 2,000 companies for revenue.[193] They include Principal Financial, Rockwell Collins, and American Equity Investment.[194][195][196] Iowa is also headquarters to other companies including Hy-Vee, Pella Corporation, Workiva, Vermeer Company, Kum & Go gas stations, Von Maur, Pioneer Hi-Bred, and Fareway.[197][198][199][200][201][202][203]

Gambling in the state is a major section of the Iowa tourism industry.[204]

الضرائب

Tax is collected by the Iowa Department of Revenue.[205]

Iowa imposes taxes on net state income of individuals, estates, and trusts. There are nine income tax brackets, ranging from 0.36% to 8.98%, as well as four corporate income tax brackets ranging from 6% to 12%, giving Iowa the country's highest marginal corporate tax rate.[206] The state sales tax rate is 6%, with non-prepared food having no tax.[207] Iowa has one local option sales tax that may be imposed by counties after an election.[208] Property tax is levied on the taxable value of real property. Iowa has more than 2,000 taxing authorities. Most property is taxed by more than one taxing authority. The tax rate differs in each locality and is a composite of county, city or rural township, school district and special levies. Iowa allows its residents to deduct their federal income taxes from their state income taxes.[209]

المواصلات

الطرق السريعة بين الولايات

المطارات والرحلات الجوية المنتظمة

السكك الحديدية

الحكومة والقانون

الأحزاب السياسية

اتجاهات الناخبين

| Year | الجمهوري | الديمقراطي |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 44.74% 677,508 | 54.04% 818,240 |

| 2004 | 49.92% 751,957 | 49.28% 741,898 |

| 2000 | 48.22% 634,373 | 48.60% 638,517 |

| 1996 | 39.92% 492,644 | 50.31% 620,258 |

| 1992 | 37.33% 504,890 | 43.35% 586,353 |

| 1988 | 44.8% 545,355 | 55.1% 670,557 |

| 1984 | 53.32% 703,088 | 45.97% 605,620 |

المجمعات الرئاسية

حقوق المجتمع

الثقافة

الفنون

The Clint Eastwood movie The Bridges of Madison County, based on the popular novel of the same name, took place and was filmed in Madison County.[211] What's Eating Gilbert Grape, based on the Peter Hedges novel of the same name, is set in the fictional Iowa town of Endora. Hedges was born in West Des Moines.[212]

Des Moines is home to members of the heavy metal band Slipknot. The state is mentioned in the band's songs, and the album Iowa is named after the state.[213]

الرياضة

The state has four major college teams playing in NCAA Division I for all sports. In football, Iowa State University and the University of Iowa compete in the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS), whereas the University of Northern Iowa and Drake University compete in the Football Championship Subdivision (FCS). Although Iowa has no professional major league sports teams, Iowa has minor league sports teams in baseball, basketball, hockey, and other sports.

The following table shows the Iowa sports teams with average attendance over 8,000. All the following teams are NCAA Division I football, basketball, or wrestling teams:[214][215][216][217]

| Team | Location | Avg. attendance |

|---|---|---|

| Iowa Hawkeyes football | Iowa City | 68,043 |

| Iowa State Cyclones football | Ames | 56,010 |

| Iowa State Cyclones men's basketball | Ames | 13,375[218] |

| Iowa Hawkeyes men's basketball | Iowa City | 12,371[218] |

| Iowa Hawkeyes wrestling | Iowa City | 12,568 |

| Iowa Hawkeyes women's basketball | Iowa City | 11,143[219] |

| Iowa State Cyclones women's basketball | Ames | 10,323[219] |

| Northern Iowa Panthers football | Cedar Falls | 9,337 |

الرياضة الجامعية

The state has four NCAA Division I college teams. Two have football teams that play in the top level of college football, the Football Bowl Subdivision: the University of Iowa Hawkeyes play in the Big Ten Conference[220] and the Iowa State University Cyclones compete in the Big 12 Conference.[221] The two intrastate rivals compete annually for the Cy-Hawk Trophy as part of the Iowa Corn Cy-Hawk Series.[222]

In wrestling, the Iowa Hawkeyes and Iowa State Cyclones have won a combined total of over 30 team NCAA Division I titles.[223][224] The Northern Iowa and Cornell College wrestling teams have also each won one NCAA Division I wrestling team title.[225][226]

Two other Division I schools play football in the second level of college football, the Football Championship Subdivision. The University of Northern Iowa Panthers play at the Missouri Valley Conference[227] and Missouri Valley Football Conference[228] (despite the similar names, the conferences are administratively separate), whereas the Drake University Bulldogs play in the Missouri Valley Conference[229] in most sports and Pioneer League for football.[230]

كرة السلة

Des Moines is home to the Iowa Cubs, a Triple-A Minor League Baseball team of the International League and affiliate of the Chicago Cubs.[231][232] Iowa has two High-A minor league teams in the Midwest League: the Cedar Rapids Kernels (Minnesota Twins) and the Quad Cities River Bandits (Kansas City Royals).[233] The Sioux City Explorers are part of the American Association of Professional Baseball.[234]

هوكي الجليد

Des Moines is home to the Iowa Wild, who are affiliated with the Minnesota Wild and are members of the American Hockey League.[235] Coralville has an ECHL team called the Iowa Heartlanders that started playing in the 2021–22 season. The Heartlanders are also an affiliate of the Minnesota Wild.[236]

The United States Hockey League has five teams in Iowa: the Cedar Rapids RoughRiders, Sioux City Musketeers, Waterloo Black Hawks, Des Moines Buccaneers, and the Dubuque Fighting Saints.[237] The North Iowa Bulls of the North American Hockey League (NAHL) and the Mason City Toros of the North American 3 Hockey League (NA3HL) both play in Mason City.[238][239]

Soccer

- The Des Moines Menace of the USL League Two play their home games at Valley Stadium in West Des Moines, Iowa.

- The Cedar Rapids Inferno Soccer Club of the Midwest Premier League play their home games at Robert W. Plaster Athletic Complex at Mount Mercy University

- The Iowa Raptors FC of the United Premier Soccer League play their home games at Prairie High School in Cedar Rapids, Iowa

- Union Dubuque F.C. of the Midwest Premier League

Other sports

Iowa has two professional basketball teams. The Iowa Wolves, an NBA G League team that plays in Des Moines, is owned and affiliated with the Minnesota Timberwolves of the NBA. The Sioux City Hornets play in the American Basketball Association.

Iowa has three professional football teams. The Sioux City Bandits play in the Champions Indoor Football league. The Iowa Barnstormers play in the Indoor Football League at Wells Fargo Arena in Des Moines. The Cedar Rapids Titans play in the Indoor Football League at the U.S. Cellular Center.

The Iowa Speedway oval track in Newton has hosted auto racing championships such as the IndyCar Series, NASCAR Xfinity Series and NASCAR Truck Series since 2006. Also, the Knoxville Raceway dirt track hosts the Knoxville Nationals, one of the classic sprint car racing events.

The John Deere Classic is a PGA Tour golf event held in the Quad Cities since 1971. The Principal Charity Classic is a Champions Tour event since 2001. The Des Moines Golf and Country Club hosted the 1999 U.S. Senior Open and the 2017 Solheim Cup.

Sister jurisdictions

Iowa has ten official partner jurisdictions:[240]

Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan (1960)

Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan (1960) Yucatán, Mexico (1964)

Yucatán, Mexico (1964) Hebei Province, People's Republic of China (1983)

Hebei Province, People's Republic of China (1983) Terengganu, Malaysia (1987)

Terengganu, Malaysia (1987) Taiwan Province, Republic of China (1989)

Taiwan Province, Republic of China (1989) Stavropol Krai, USSR/Russia (1989)

Stavropol Krai, USSR/Russia (1989) Cherkasy Oblast, Ukraine (1996)

Cherkasy Oblast, Ukraine (1996) Veneto Region, Italy (1997)

Veneto Region, Italy (1997) Republic of Kosovo (2013) A consulate was opened in Des Moines in 2015.[241]

Republic of Kosovo (2013) A consulate was opened in Des Moines in 2015.[241]

رموز الولاية

أنظر أيضا

ملاحظات

- ^ أ ب Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ^ The Missouri and Mississippi river boundaries are as they were mapped in the 19th century, which can vary from their modern courses.

- ^ Persons of Hispanic or Latino origin are not distinguished between total and partial ancestry.

- ^ Based on 2000 U.S. Census Data.

المصادر

- ^ Secretary of State, Iowa (2000). "Iowa Official Register". Iowa Publications Online. State Library of Iowa.

- ^ Bureau, US Census. "State Area Measurements and Internal Point Coordinates". Census.gov.

- ^ أ ب "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on November 2, 2011. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "Iowa Profile". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ قالب:MerriamWebsterDictionary

- ^ "Iowa". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ^ "Iowa". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ^ Goodson, Christina (2019). Iro Tųwahi Wisahma Nąha: the Seventh Generation, Understanding Jiwere Language Status and Reclamation Through Community Input. The University of Oklahoma. p. 1.

- ^ "Resident Population for the 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: 2020 Census" (PDF). Census.gov. April 27, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2010–2018". Archived from the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ^ "N.H. Receives Lowest Crime Ranking; Nevada Ranks as Worst State". Insurance Journal. Wells Publishing. March 25, 2009. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- ^ Merry, Carl A. (1996). "The Historic Period". Office of the State Archeologist at the University of Iowa. Archived from the original on June 4, 2009. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- ^ "Major Industries in Iowa" (PDF). Iowa Department of Economic Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 20, 2005. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- ^ أ ب "Wind Energy in Iowa". Iowa Energy Center. Archived from the original on June 21, 2009. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- ^ أ ب Erin Jordan (May 6, 2018). "Large-scale pork production may push farther into Eastern Iowa". The Gazette (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ Alex, Lynn M. (2000). Iowa's Archaeological Past. University of Iowa Press, Iowa City.

- ^ أ ب ت Alex, Lynn M. (2000) Iowa's Archaeological Past. University of Iowa Press, Iowa City.

- ^ أ ب ت Peterson, Cynthia L. (2009). "Historical Tribes and Early Forts". In William E. Whittaker (ed.). Frontier Forts of Iowa: Indians, Traders, and Soldiers, 1682–1862. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. pp. 12–29. ISBN 978-1-58729-831-8. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ History of Iowa, Iowa Official Register, Publications.iowa.gov Archived سبتمبر 3, 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Herbermann, Charles. The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church. Encyclopedia Press, 1913, p. 380 (Original from Harvard University).

- ^ Carlson, Gayle F. (2009). "Fort Atkinson, Nebraska, 1820–1827, and Other Missouri River Sites". In William E. Whittaker (ed.). Frontier Forts of Iowa: Indians, Traders, and Soldiers, 1682–1862. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. pp. 104–120. ISBN 978-1-58729-831-8. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ "Treaty of San Ildefonso 1800". Napoleon-series.org. Archived from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ Pike (1965): The expeditions of Zebulon Montgomery Pike to headwaters of the Mississippi River, through Louisiana Territory, and in New Spain, during the years June 7, 1805, Ross & Haines

- ^ أ ب McKusick, Marshall B. (2009). "Fort Madison, 1808–1813". In William E. Whittaker (ed.). Frontier Forts of Iowa: Indians, Traders, and Soldiers, 1682–1862. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. pp. 55–74. ISBN 978-1-58729-831-8. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ Prucha, Francis P. (1969) The Sword of the Republic: The United States Army on the Frontier 1783–1846. Macmillan, New York.

- ^ Jackson, Donald (1960), A Critic's View of Old Fort Madison, Iowa Journal of History and Politics 58(1) pp.31–36

- ^ Black Hawk (1882) Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak or Black Hawk. Continental Printing, St. Louis. (Originally published 1833)

- ^ The History of Jackson County, Iowa, Containing a History of the County, Its Cities, Towns, &c., Biographical Sketches of Citizens. Chicago: Western Historical Co. 1879. p. 531.

- ^ Whittaker, William E., ed. (2009). Frontier Forts of Iowa: Indians, Traders, and Soldiers, 1682–1862. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. ISBN 978-1-58729-831-8. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ Drexler, Ken. "Research Guides: Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents in American History: Introduction". guides.loc.gov. Archived from the original on April 5, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ أ ب Jung, Patrick J. (2007). The Black Hawk War of 1832. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3811-4. OCLC 70718369.

- ^ "INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES Vol. II, Treaties". Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ "History | Meskwaki Nation". Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ Reicher, Matt (March 15, 2019). "Ho-Chunk and Long Prairie, 1846–1855". Mnopedia. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ "Minnesota Treaties | The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862". Usdakotawar.org. August 14, 2012. Archived from the original on August 25, 2019. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ Clifton, James A.; Cornell, George L.; McClurken, James M. (1986), People of the Three Fires, p. 37, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED321956.pdf, retrieved on April 14, 2020

- ^ أ ب Schwieder, Dorothy. "History of Iowa". Iowa State University. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ "Jackson County, Iowa History Information". Jackson County, Iowa. Archived from the original on November 4, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Iowa Official Register, Volume Number 60, page 314

- ^ "Official Encouragement of Immigration to Iowa", Marcus L. Hansen, IJHP, 19 (April 1921):159–95

- ^ "Iowa State Fair". Trivia. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ "Safety". Iowa State Fair. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ Lendt, David L. (1970). "Iowa and the Copperhead Movement". The Annals of Iowa. 40 (6): 412–427. doi:10.17077/0003-4827.7965. Archived from the original on May 10, 2022 – via Iowa Research Online.

- ^ أ ب ت Iowa Official Register, Volume No. 60, page 315

- ^ "Civil War". Iowanationalguard.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ Iowa Official Register, Volume No. 60, pages 315–316

- ^ "1860 Census: Population of the United States" Archived يناير 21, 2021 at the Wayback Machine. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Bureau, US Census. "1880 Census: Volume 1. Statistics of the Population". The United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ أ ب "The Economics of Agriculture". Iowa PBS. July 25, 2016. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ "Types of Business and Industry". Iowa PBS. July 25, 2016. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ "Early Industry". Iowa PBS. July 25, 2016. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Schwieder, Dorothy. "History of Iowa". publications.iowa.gov. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ Walsh, Matthew. The Good Governor: Robert Ray and the Indochinese Refugees of Iowa (McFarland & Co, 2017)

- ^ Office of Asian and Pacific Islander Affairs, Iowa Department of Human Rights. State of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Iowa, 2015

- ^ The Midwest Farm Crisis of the 1980s, Tripod.com Archived يوليو 6, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Population Trends: The Changing Face of Iowa, State.ia.us Archived أكتوبر 6, 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب ت ث Iowa Industries, Iowa Workforce Development. Iowalifechanging.com Archived مايو 20, 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب "Historical Population Change Data (1910–2020)". Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ أ ب Iowa Data Center, 2000 Census: Iowadatacenter.org Archived ديسمبر 3, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Iowa Economic Development Authority". iowaeconomicdevelopment.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Preamble to the 1857 Constitution of the State of Iowa. Archived from the original on August 2, 2009. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ^ 48 U.S. (7 How.) 660 (1849).

- ^ Morrison, Jeff (January 13, 2005). "Forty-Thirty-five or fight? Sullivan's Line, the Honey War, and latitudinal estimations". Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ^ "Iowa Fast Facts and Trivia". 50states.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "About Carter Lake". Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ "National Association of Counties". County Seats. Archived from the original on December 22, 2010. Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- ^ Prior, Jean Cutler. Geology of Iowa: Iowa's Earth History Shaped by Ice, Wind, Rivers, and Ancient Seas. Adapted from Iowa Geology 2007, Iowa Department of Natural Resources. Iowa Department of Natural Resources Geological Survey. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ^ Anderson, Wayne I. (1998). Iowa's Geological Past: Three Billion Years of Change. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. p. 21.

- ^ أ ب Prior, Jean C. (1991). Landforms of Iowa. University of Iowa Press, Iowa City. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009.

- ^ "Geology of the Loess Hills, Iowa". United States Geological Survey. July 1999. Archived from the original on March 28, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "Landforms of Iowa" (PDF). Uni.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Odessa". Iowa Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ "Wetlands". Iowadnr.gov. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Iowa DNR: Iowa's Statewide Land Cover Inventory, Uiowa.edu Archived مايو 2, 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ricketts, Taylor H. (1999). Terrestrial ecoregions of North America : a conservation assessment. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-722-6. OCLC 40856986.

- ^ "Central tall grasslands | Ecoregions | WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Iowa's Threatened and Endangered Species Program, Iowadnr.gov Archived سبتمبر 24, 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Des Moines Register", June 1, 2019, Iowa Must Step Up Investment in Public Lands Archived يوليو 22, 2011 at the Wayback Machine Nicholasjohnson.org

- ^ Federally Listed Animals in Iowa, Agriculture.state.ia.us Archived سبتمبر 30, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Federally Listed Plants in Iowa, Agriculture.state.ia.us Archived سبتمبر 30, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Living with Hogs in Rural Iowa". Iowa Ag Review. Iowa State University. 2003. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ Heldt, Diane (November 24, 2009). "Report: Many Iowa coal plants among nation's oldest". Cedar Rapids Gazette. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ "Iowa Works to Reduce Run-off Polluting the Gulf of Mexico". The Iowa Journal. Iowa Public Television. September 17, 2009. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ Love, Orlan (December 6, 2009). "Heavy use draining aquifer". Cedar Rapids Gazette. Archived from the original on December 9, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ Charmayne Hefley (2024-01-29). "Iowa faces longest stretch of drought since the 1950s" (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ "Climate Iowa: Temperature, climate graph, Climate table for Iowa - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ "Average Annual Snowfall Totals in Iowa – Current Results". Currentresults.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ US Thunderstorm distribution. src.noaa.gov. Retrieved February 13, 2008. Archived أكتوبر 15, 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Des Moines, IA". noaa.gov. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ "2008 Iowa tornadoes deadliest since 1968". USA Today. January 2, 2009. Archived from the original on October 11, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ Keokuk Comprehensive Plan 2018. June 2018. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://www.cityofkeokuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Keokuk-Comprehensive-Plan-2018.pdf. Retrieved on April 6, 2020. - ^ Munson, Kyle. "Site of Iowa's coldest temp shivers with rest of state". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ "Iowa Weather-Iowa Weather Forecast-Iowa Climate". ustravelweather.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Davenport, Iowa". Weather.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2008. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ^ "Average Weather for Des Moines, IA—Temperature and Precipitation". Weather.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ "Daily Averages for Keokuk, IA". weather.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ "Average Weather for Mason City, IA—Temperature and Precipitation". Weather.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ "Average Weather for Sioux City, IA—Temperature and Precipitation". Weather.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ Average Annual Precipitation Iowa, 1961–1990 (GIF File) Archived فبراير 13, 2010 at the Wayback Machine—Christopher Daly, Jenny Weisburg

- ^ "Average Weather for Des Moines, IA—Temperature and Precipitation, Weather.com, Retrieved Jan. 7, 2009". Weather.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ Data from U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Modeled after Iowa Data Center Map, Iowadatacenter.org Archived يناير 17, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Iowans still flocking to cities, census stats show. Cedar Rapids Gazette, June 30, 2009, Gazetteonline.com Archived مارس 30, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau State and County Quick Facts, Census.gov Archived مايو 27, 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Grimes, William (September 14, 2005). "In This Small Town in Iowa the Future Speaks Spanish". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Iowa Brain Drain, Iowa Civic Analysis Network, University of Iowa, Uiowa.edu Archived أبريل 12, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2020". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "Population 2010—Iowa Cities". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ^ "Estimates of Resident Population Change and Rankings: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2020—United States—Metropolitan Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "Numeric and Percent Change in Resident Population" (PDF). 2020 Census Apportionment Results. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. April 26, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ "Quickfacts: Iowa". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Census quickfacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ John W. Wright, ed. (2007). The New York Times 2008 Almanac. Penguin Group (USA) Incorporated. p. 178. ISBN 9780143112334.

- ^ Bureau, US Census. "Centers of Population for the 2010 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "Immigrants in Iowa" (PDF). American Immigration Council.

- ^ "Settlers, Immigrants, Agriculture". Encyclopedia Britannica. 26 July 1999.

- ^ "African-American Communities".

- ^ "2010 Demographic Profile Data". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "2007-2022 PIT Counts by State".

- ^ "The 2022 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress" (PDF).

- ^ "Race and Ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. August 12, 2021. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- ^ "Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The United States, Regions, Divisions, and States". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ "Population of Iowa: Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts". Censusviewer.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ 2010 Census Data. "2010 Census Data". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "2016 American Community Survey—Demographic and Housing Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ "2016 American Community Survey—Selected Social Characteristics". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ National Vital Statistics Reports—Births: Final Data for 2013. 64. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. January 15, 2015. pp. 35–6. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_01.pdf. Retrieved on February 3, 2019. - ^ National Vital Statistics Reports—Births: Final Data for 2014. 64. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. December 23, 2015. pp. 35–6. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_12.pdf. Retrieved on February 3, 2019. - ^ National Vital Statistics Reports—Births: Final Data for 2015. 66. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. January 5, 2017. pp. 38, 40. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr66/nvsr66_01.pdf. Retrieved on February 3, 2019. - ^ National Vital Statistics Reports—Births: Final Data 2016. 67. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. January 31, 2018. p. 26. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr67/nvsr67_01.pdf. Retrieved on February 3, 2019. - ^ National Vital Statistics Reports—Births, by race and origin of mother: United States, each state and territory, 2017. 67. November 7, 2018. p. 20. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr67/nvsr67_08-508.pdf. Retrieved on February 18, 2019. - ^ Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Driscoll, Anne K. (November 27, 2019). Births: Final Data for 2018. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_13-508.pdf. Retrieved on February 26, 2020. - ^ "Data" (PDF). Cdc.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 23, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ^ Staff (February 24, 2023). "American Values Atlas: Religious Tradition in Iowa". Public Religion Research Institute. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ "Religious composition of adults in Iowa". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "American Religious Identification Survey 2001" (PDF). The Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ "The Association of Religion Data Archives | State Membership Report". thearda.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ^ "PRRI – American Values Atlas". ava.prri.org. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ "Religious Congregations & Membership: 2000". Glenmary Research Center. Archived from the original (jpg) on December 14, 2006. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- ^ Elmer Schwieder and Dorothy Schwieder (2009) A Peculiar People: Iowa's Old Order Amish University of Iowa Press

- ^ "Iowa Jewish History". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ "Jewish Settlers in Iowa | Iowa PBS". www.iowapbs.org (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-11-13.