تنگرية

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| التنگرية |

|---|

|

| ديانة في آسيا الوسطى–السهوب الأوراسية وجزئياً سيبيريا–شرق آسيا |

| الإله الأعظم |

| آلهة/أرواح أخرى |

| الحركات |

| حركات ذات صلة |

| أشخاص |

| الكهنة |

| النصوص |

| الأماكن المقدسة |

| على أسماء الأماكن |

| مفاهيم ذات صلة |

تنگرية Tengrism، وتُعرف أيضاً بإسم تنگريئية Tengriism، Tenggerism أو Tengrianism، هي ديانة دولة قديمة وقروسطية، في آسيا الوسطى–السهوب الأوراسية، تتمحور حول عبادة إله السماء تنگري وكذلك عدد من الحركات والتعاليم الدينية المحلية التوركية-المنغولية المعاصرة. وكانت الديانة السائدة بين التورك والمنغول (بما في ذلك البلغار و الهون و شيونگنو)، ويُحتمل، المانچو والمجر، كديانة العديد من دول العصور الوسطى: خاقانية الگوقتورك، الخاقانية التوركية الغربية، الخاقانية التوركية الشرقية، بلغاريا الكبرى القديمة, بلغاريا الدانوب، بلغاريا الڤولگا, وتوركيا الشرقية (خزريا). وفي Irk Bitig، تُذكر التنگرية على أنها عبادة Türük Tängrisi (إله التورك).[1] وحسب العديد من الأكاديميين، على المستوى الامبراطوري، خصوصاً بحلول القرون الثاني عشر والثالث عشر، كانت التنگرية ديانة توحيدية ؛ ومعظم التنگريين المعاصرين يقدمونها كديانة توحيدية أيضاً.

صيَغ الاسم تـِنگري (Old Turkic: Täŋri)[2] بين التورك القدماء والمعاصرين والمنغول هي Tengeri, Tangara, Tangri, Tanri, Tangre, Tegri, Tingir, Tenkri, Teri, Ter، و Ture.[3] الاسم تنگري ("السماء") مشتق من Old Turkic: Tenk ("مطلع النهار") أو تان ("فجر").[4] منغوليا أحياناً تُسمى بشكل شاعري "أرض السماء الزرقاء الأبدية" (Munkh Khukh Tengriin Oron) من قِبل سكانها.

التنگرية يُدافع عنها في الدوائر الثقافية للأمم التوركية بآسيا الوسطى (قيرغيزستان مع قزخستان) وروسيا (تتارستان، وبشكورتوستان) منذ فض الاتحاد السوڤيتي في ع1990. ولأنها مازالت ممارَسة، فإنها تخضع لإحياء منظم في بورياتيا وساخا (ياقوتيا)، وخقاسيا، توڤا وأمم توركية أخرى في سيبيريا. البورخانية الألطائية و ڤتـِّيسن يالي التشوڤاشية هما حركتان مماثلتان للتنگرية.

العلاقة بالشامانية

The word "Tengrism" is a fairly new term. The spelling Tengrism for the religion of the ancient Turks is found in the works of the 19th century Kazakh Russophone ethnographer Shoqan Walikhanov.[5] The term was introduced into a wide scientific circulation in 1956 by Jean-Paul Roux[6] and later in the 1960s as a term of English-language papers.[7]

التنگرية التاريخية

For the first time the name Tengri recorded in Chinese chronicles from the 4th century BC as the sky god of the شيونگنو, it takes the Chinese form 撑犁 (Cheng-li).

The cult of Heaven-Tengri is fixed by the Orkhon, or Old Turkic script used by the الگوقتورك ("celestial Turks") and other early khanates during the 8th to 10th centuries.[10]

Tengrism was the religion of the several medieval states: خاقانية الگوقتورك، الخاقانية التوركية الغربية، وبلغاريا الكبرى القديمة, بلغاريا الدانوب، بلغاريا الڤولگا، وتوركيا الشرقية (خزريا)[11] Turkic beliefs contains the sacral book Irk Bitig من خاقانية الأويغور.[1]

Tengrism also played a large role in the religion of Mongol Empires as the primary statespirituality. Genghis Khan and several generations of his followers were Tengrian believers and "Shaman-Kings" until his fifth-generation descendant, Uzbeg Khan, turned to Islam in the 14th century. Old Tengrist prayers have come to us from the Secret History of the Mongols (13th century). The priests-prophets (temujin) resevied them, according to faiths, from the great deity/spirit Munkh Tenger.[12]

The original Mongol khans, followers of Tengri, were known for their tolerance of other religions.[13] Möngke Khan, the fourth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, said: "We believe that there is only one God, by whom we live and by whom we die, and for whom we have an upright heart. But as God gives us the different fingers of the hand, so he gives to men diverse ways to approach him." ("Account of the Mongols. Diary of William Rubruck", religious debate in court documented by William of Rubruck on May 31, 1254).

نقوش أُرخـُن

According to the Orkhon inscriptions, Tengri played a big role in choices of the kaghan, and in guiding his actions. Many of these were performed because "Heaven so ordained" (Old Turkic: Teŋіri yarïlqaduq üčün).[14]

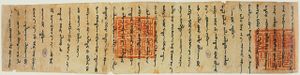

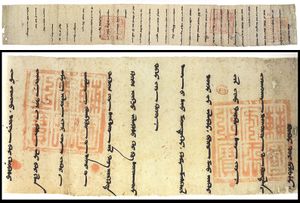

رسائل أرغون

Arghun expressed the association of Tengri with imperial legitimacy and military success. The majesty (suu) of the khan is a divine stamp granted by Tengri to a chosen individual through which Tengri controls the world order (the presence of Tengri in the khan). In this letter, "Tengri" or "Mongke Tengri" ("Eternal Heaven") is at the top of the sentence. In the middle of the magnified section, the phrase Tengri-yin Kuchin ("Power of Tengri") forms a pause before it is followed by the phrase Khagan-u Suu ("Majesty of the Khan"):

Under the Power of the Eternal Tengri. Under the Majesty of the Khan (Kublai Khan). Arghun Our word. To the Ired Farans (King of France). Last year you sent your ambassadors led by Mar Bar Sawma telling Us: "if the soldiers of the Il-Khan ride in the direction of Misir (Egypt) we ourselves will ride from here and join you", which words We have approved and said (in reply) "praying to Tengri (Heaven) We will ride on the last month of winter on the year of the tiger and descend on Dimisq (Damascus) on the 15th of the first month of spring." Now, if, being true to your words, you send your soldiers at the appointed time and, worshipping Tengri, we conquer those citizens (of Damascus together), We will give you Orislim (Jerusalem). How can it be appropriate if you were to start amassing your soldiers later than the appointed time and appointment? What would be the use of regretting afterwards? Also, if, adding any additional messages, you let your ambassadors fly (to Us) on wings, sending Us luxuries, falcons, whatever precious articles and beasts there are from the land of the Franks, the Power of Tengri (Tengri-yin Kuchin) and the Majesty of the Khan (Khagan-u Suu) only knows how We will treat you favorably. With these words We have sent Muskeril (Buscarello) the Khorchi. Our writing was written while We were at Khondlon on the sixth khuuchid (6th day of the old moon) of the first month of summer on the year of the cow.[15]

Arghun expressed Tengrism's non-dogmatic side. The name Mongke Tengri ("Eternal Tengri") is at the top of the sentence in this letter to Pope Nicholas IV, in accordance with Mongolian Tengriist writing rules). The words "Tngri" (Tengri) and "zrlg" (zarlig, decree/order) are still written with vowel-less archaism:

... Your saying "May [the Ilkhan] receive silam (baptism)" is legitimate. We say: "We the descendants of Genghis Khan, keeping our own proper Mongol identity, whether some receive silam or some don't, that is only for Eternal Tengri (Heaven) to know (decide)." People who have received silam and who, like you, have a truly honest heart and are pure, do not act against the religion and orders of the Eternal Tengri and of Misiqa (Messiah or Christ). Regarding the other peoples, those who, forgetting the Eternal Tengri and disobeying him, are lying and stealing, are there not many of them? Now, you say that we have not received silam, you are offended and harbor thoughts of discontent. [But] if one prays to Eternal Tengri and carries righteous thoughts, it is as much as if he had received silam. We have written our letter in the year of the tiger, the fifth of the new moon of the first summer month (May 14th, 1290), when we were in Urumi.[16]

التنگرية في التاريخ السري للمنغول

Tengri is mentioned many times in the Secret History of the Mongols, written in 1240.[17] The book starts by listing the ancestors of Genghis Khan starting from Borte Chino (Blue Wolf) born with "destiny from Tengri". Bodonchar Munkhag the 9th generation ancestor of Genghis Khan is called a "son of Tengri". When Temujin was brought to the Qongirat tribe at 9 years old to choose a wife, Dei Setsen of the Qongirat tells Yesugei the father of Temujin (Genghis Khan) that he dreamt of a white falcon, grasping the sun and the moon, come and sit on his hands. He identifies the sun and the moon with Yesugei and Temujin. Temujin then encounters Tengri in the mountains at the age of 12. The Taichiud had come for him when he was living with his siblings and mother in the wilderness, subsisting on roots, wild fruits, sparrows and fish. He was hiding in the thick forest of Terguun Heights. After three days hiding he decided to leave and was leading his horse on foot when he looked back and noticed his saddle had fallen. Temujin says "I can understand the belly strap can come loose, but how can the breast strap also come loose? Is Tengri persuading me?" He waited three more nights and decided to go out again but a tent-sized rock had blocked the way out. Again he said "Is Tengri persuading me?", returned and waited three more nights. Finally he lost patience after 9 days of hunger and went around the rock, cutting down the wood on the other side with his arrow-whittling knife, but as he came out the Taichiud were waiting for him there and promptly captured him. Toghrul later credits the defeat of the Merkits with Jamukha and Temujin to the "mercy of mighty Tengri" (paragraph 113).

التنگرية المعاصرة

A revival of Tengrism has played a role in search for native spiritual roots and Pan-Turkism ideology since the 1990s, especially, in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, some autonomous republics of the Russian Federation (Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, Buryatia, Yakutia, and others), among the Crimean Karaites and Crimean Tatars. [18][19]

After 1908 Young Turk Revolution, and especially the proclamation of the Republic in 1923, a nationalist idleology of Turanism and Kemalism contributed to the revival of Tengism. Islamic censorship was abolished, which allowed an objective study of the pre-Islamic religion of the Turks. The Turkish language was purified of Arabic, Persian and other borrowings. A number of figures, if they did not officially abandon Islam, but adopted Turkic names, such as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (Atatürk — "father of Turks") and the historian of religion and ideologist of the Kemalist regime Ziya Gökalp (Gökalp — "sky hero").[20]

الكاتب والمؤرخ التركي البارز نيهال أتسيز كان تـِنگرياً ومنظـِّراً للطورانية. أتباع التنگرية في المنظمة الميليشياوية الذئاب الرمادية، كانت أعمال أتسيز هي مصدر إلهامهم الرئيسي، فاستبدلوا الاسم العربي للإله، "الله"، بالاسم التركي "تنري" في قـَسـَمهم، فيقولون: "Tanrı Türkü Korusun" (تـِنگري، فلتبارِك التورك!).[21]

الرموز والأماكن المقدسة

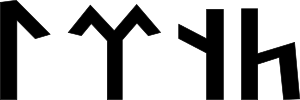

رمز يستخدمه العديد من التنگريين، يمثل التهجي الروني للإله تنگري و "شنگرك" (صليب مكافئ في دائرة)، يصور فتحة سقف يورت، وطبلة شامان.

Many world-pictures and symbols are attributed to folk religions of Central Asia and Russian Siberia. Shamanistic religious symbols in these areas are often intermixed. For example, drawings of world-pictures on Altaic shamanic drums.[22]

انظر أيضاً:

- علم تشوڤاشيا

- علم قزخستان

- علم قيرغيزستان

- علم جمهورية ساخا

- عملات الگوقتورك

- گون آنا — الشمس (المصوّرة في معظم الأعلام)

- شجرة الحياة

The tallest mountain peaks usually became sacred places. Since the time of the Turkic Khaganate, this is Otgontenger in Mongolia—perhaps, the Otuken of the old inscriptions, state ceremonies are held were. Among others: Belukha (or Üch-Sümer) in Russia's Altai,[23] Khan Tengri alias Jengish Chokusu in Kyrgyzstan (not to be confused with the modern Khan Tengri),[24] and Burkhan Khaldun in Mongolia, associated with the name of Genghis Khan. Symbolic mountains are man-made shrines-ovoos.

المعتقدات

إله

Kök Tengri (Blue Sky) is the Supreme Being, the One, the creator of everything. Usually it is understood pantheistically/panentheistically as a non-anthropomorphic Absolute, a concept identical to Taoist Tao, Indian Para Brahman, ancient Greek Apeiron, or Unified Field of modern science.[25]

All other deities are revered as Tengri's manifestations or spirits of the elements. Such, for instance, the pantheon of the ancient Turks: Yer-Sub, Umay, Erlik, Earth, Water, Fire, Sun, Moon, Star, Air, Clouds, Wind, Storm, Thunder and Lightning, Rain and Rainbow.[26]

علم الكون ذو الثلاث عوالم

قالب:Disputed section As in most ancient beliefs, there is a "celestial world", the ground and an "underworld" in Tengrism.[27] The only connection between these realms is the "Tree of Worlds" that is in the center of the worlds.

The celestial and the subterranean world are divided into seven layers (the underworld sometimes nine layers and the celestial world 17 layers). Shamans can recognize entries to travel into these realms. In the multiples of these realms, there are beings, living just like humans on the earth. They also have their own respected souls and shamans and nature spirits. Sometimes these beings visit the earth, but are invisible to people. They manifest themselves only in a strange sizzling fire or a bark to the shaman.[28][29]

According to the adherence of Tengrism, the world is not only a three-dimensional environment, but also a rotating circle. Everything is bound by this circle and the tire is always renewed without stopping. The three dimensions of the Earth consists of the movement of the sun, the season which are constantly moving, and the souls of all creatures that are born again after death.[28]

العالم السماوي

The celestial world has many similarities with the earth, but as undefiled by humans. There is a healthy, untouched nature here, and the natives of this place have never deviated from the traditions of their ancestors. This world is much brighter than the earth and is under the auspices of Ulgen another son of Tengri. Shamans can also visit this world.[28]

On some days, the doors of this heavenly world are opened and the light shines through the clouds. During this moment, the prayers of the shamans are most influential. A shaman performs his imaginary journey, which takes him to the heavens, by riding a black bird, a deer or a horse or by going into the shape into these animals. Otherwise he may scale the World-Tree or pass the rainbow to reach the heavenly world.[28]

العالم السفلي

There are many similarities between the earth and the underworld and its inhabitants resemble humans, but have only two souls instead of three. They lack the "Ami soul", that produces body temperature and allows breathing. Therefore, they are pale and their blood is dark. The sun and the moon of the underworld give far less light than the sun and the moon of the earth. There are also forests, rivers and settlements underground.[28]

Erlik Khan (Mongolian: Erleg Khan), one of the sons of Tengri, is the ruler of the underworld. He controls the souls here, some of them waiting to be reborn again. Extremely evil souls were believed to be extinguished forever in Ela Guren.[28] If a sick human is not dead yet, a shaman can move to the underworld to negotiate with Erlik to bring the person back to life. If he fails, the person dies.[28]

الأرواح

It is believed that people and animals have many souls. Generally, each person is considered to have three souls, but the names, characteristics and numbers of the souls may be different among some of the tribes: For example, for Samoyets, a Mongol tribe living in the north of Siberia, believe that women consist of four and men of five souls. Since animals also have souls, humans must respect animals.[بحاجة لمصدر]

According Paulsen and Jultkratz, who conducted research in North America, North Asia and Central Asia by Paulsen and Jultkratz, explained two souls of this belief are the same to all people:

- Nefes (Breath or Nafs, life or bodily spirit)

- Shadow soul / Free soul

There are many different names for human souls among the Turks and the Mongols, but their features and meanings have not been adequately researched yet.

- Among Turks: Özüt, Süne, Kut, Sür, Salkin, Tin, Körmös, Yula

- Among Mongols: Sünesün, Amin, Kut, Sülde[30]

In addition to these spirits, Jean Paul Roux draws attention to the "Özkonuk" spirit mentioned in the writings from the Buddhist periods of the Uighurs.

Julie Stewart, who devoted her life to research in Mongolia described the belief in the soul in one of her articles:

- Amin ruhu: Provides breathing and body temperature. It is the soul which invigorates. (The Turkish counterpart is probably Özüt)

- Sünesün ruhu: Outside of the body, this soul moves through water. It is also the part of soul, which reincarnates. After a human died, this part of the soul moves to the world-tree. When it is reborn, it comes out of a source and enters the new-born. (Also called Süne ruhu among Turks)

- Sülde ruhu: It is the soul of the self that gives a person a personality. If the other souls leave the body, they only loss consciousness, but if this soul leaves the body, the human dies. This soul resides in nature after death and is not reborn.[28]

التنگرية والبوذية

The 17th century Mongolian chronicle Altan Tobchi (الملخص الذهبي) contains references to Tengri. Tengrism was assimilated into Mongolian Buddhism while surviving in purer forms only in far-northern Mongolia. Tengrist formulas and ceremonies were subsumed into the state religion. This is similar to the fusion of Buddhism and Shinto in Japan. The Altan Tobchi contains the following prayer at its very end:

Aya gaihamshig huvilgaan bogdos haadiin yazguuriig odii todii tuuhnees |

Aya! The origin of the marvelous divine Khans from miscellaneous histories |

التنگرية والإسلام

Tengrism is based on personal relationship with God and spirits and personal experiences, which cannot be fixiated in writings; thus there can be no a prophet, holy scripture, place of worship, clergy, dogma, rite and prayers.[31] In contrast, Islam is based on a written corpus. Doctrines and religious law derive from the Quran and are explained by hadith. In this regard, both belief systems are fundamentally distinct.[32] Turks usually encountered and assimilated their beliefs to Islam via Sufism. Turks probably identified Dervishes as something akin to shamans.[33] First contact between shamanistic Turks and Islam took place during the Battle of Talas against the Chinese Tang dynasty. Turkic Tengrism further influenced parts of Sufism and Folk Islam, especially Alevism with Bektashi Order.[34][32] Many shamanistic beliefs were considered as genuine Islamic by many average Muslims and even prevail today.[35]

Muslim Turkic scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari, around the year 1075, whom he considered Tengrists as "infidel", offered this view: "The infidels — may God destroy them! — call the sky Tengri, also anything that is imposing in their eyes call Tengri, such as a great mountain or tree, and they bow down to such things."[36]

Tengrists oppose Islam, Christianity and Judaism as Semitic religions imposing a foreign religion to the Turks. And, according to some ones, by praying to the god of Islam the Turkic peoples would give their energy to the Jews and not to themselves (Aron Atabek).[37] It excludes the experiences of other nations, but offers Semitic history as if it were the history of all humanity. The principle of submission (both in Islam as well as in Christianity) is disregarded as one of the major failings. It allows rich people to abuse the ordinary people and makes human development stagnant. They advocate Turanism and abandonment of Islam as an Arab religion (Nihal Atsiz and others).[21] Prayer from the heart can only be in native language, not Arabic.[38] On the contrary, others assert that Tengri is indeed synonymous with Allah and that Turkic ancestors did not leave their former belief behind, but simply accepted Allah as new expression for Tengri.[39]

Aron Atabek draws attention to how the Islamization of the Kazakhs and other Turkic peoples was carried out: runic letters were destroyed, physically persecuted shamans, national musical instruments were burned and playing on them was condemned, etc. [40]

انظر أيضاً

- Heaven worship

- Manzan Gurme Toodei

- Hungarian neopaganism

- الدين في الصين

- قائمة الحركات التنگرية

- List of Tengrist states and dynasties

الهامش

- ^ أ ب Tekin 1993.

- ^ Roux 1956.

- ^ Pettazzoni 1956, p. 261; Tanyu 1980, p. 9f; Güngör; Günay 1997, p. 36.

- ^ Tanyu 2007, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Laruelle 2007, p. 204.

- ^ Roux 1956; Roux 1984, p. 65.

- ^ E.g., Bergounioux (ed.), Primitive and prehistoric religions, Vol. 140, Hawthorn Books, 1966, p. 80.

- ^ Hoppál, Mihály (2005). Sámánok Eurázsiában (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-05-8295-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) pp. 77, 287; Znamensky, Andrei A. (2005). "Az ősiség szépsége: altáji török sámánok a szibériai regionális gondolkodásban (1860–1920)". In Molnár, Ádám (ed.). Csodaszarvas. Őstörténet, vallás és néphagyomány. Vol. I (in Hungarian). Budapest: Molnár Kiadó. pp. 117–134. ISBN 978-963-218-200-1.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link), p. 128 - ^ Tekin 1993, p. 8.

- ^ Pettazzoni 1956, p. 261; Gumilyov 1967, ch. 7.

- ^ Golden 1992; Poemer 2000.

- ^ Brent 1976; Roux 2003; Bira 2011; Turner 2016, ch. 3.3.

- ^ Osman Turan, The Ideal of World Domination among the Medieval Turks, in Studia Islamica, No. 4 (1955), pp. 77-90

- ^ Barbara Kellner-Heinkele, (1993), Altaica Berolinensia: The Concept of Sovereignty in the Altaic World, p. 249

- ^ For another translation here Archived 2016-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Translation on page 18 here Archived 2017-08-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Secret History of the Mongols 2004.

- ^ Laruelle 2006, pp. 3–4; Laruelle 2007, p. 205; Turner 2016, ch. 9.3 Tengerism; Popov 2016.

- ^ Saunders, Robert A.; Strukov, Vlad (2010). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Federation. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. pp. 412–13. ISBN 978-0-81085475-8.

- ^ Bacqué-Grammont, Jean-Louis; Roux, Jean-Paul (1983). Mustafa Kemal et la Turquie nouvelle (in الفرنسية). Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose. ISBN 2-7068-0829-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ أ ب Saraçoǧlu 2004.

- ^ "Parts of a story of a world picture". Archived from the original on 2017-07-01. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ Adji 2005, preface.

- ^ Laruelle 2007, p. 210.

- ^ Omuraliyev 2012, pp. 39, 296–97.

- ^ Bezertinov 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Edelbay, Saniya (2012). Traditional Kazakh Culture and Islam. International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 11 p. 129.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Stewart 1997.

- ^ Türk Mitolojisi, Murat Uraz, 1992 ISBN 9759792359 Parameter error in {{isbn}}: Invalid ISBN.

- ^ Götter und Mythen in Zentralasien und Nordeurasien Käthe Uray-Kőhalmi, Jean-Paul Roux, Pertev N. Boratav, Edith Vertes: ISBN 3-12-909870-4 İçinden: Jean-Paul Roux: Die alttürkische Mythologie (Eski Türk mitolojisi)

- ^ Laruelle 2007, pp. 208–9.

- ^ أ ب Aigle, Denise (2014). The Mongol Empire between Myth and Reality: Studies in Anthropological History, BRILL ISBN 978-9-0042-8064-9 p. 107

- ^ Findle, Carter V. (2005). The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press ISBN 9780195177268

- ^ Eröz 1992.

- ^ Çakmak, Cenap (2017). Islam: A Worldwide Encyclopedia [4 vols], ABC-CLIO ISBN 9781610692175 pp. 1425–29

- ^ Weatherford, Jack (2016). Genghis Khan and the Quest for God: How the World's Greatest Conqueror Gave Us Religious Freedom, p. 59

- ^ Laruelle 2007, p. 213.

- ^ Devbash 2011.

- ^ Dudolgnon (2013). Islam In Politics In Russia, Routledge ISBN 9781136888786 pp. 301-4

- ^ Atabek, Aron. "Islam and Tengrism. Reflections of the seeker of truth." (in روسية) In "Collection of reports at the First international scientific conference on Tengrism "Tengrism—the worldview of the Altaic peoples". Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek, November 2003, p. 194.

ببليوگرافيا

مصادر ثانوية

- Alici, Mustafa (2011). "The Idea of God in Ancient Turkish Religion According to Raffaele Pettazzoni. A Comparison with the Turkish Historian of Religions Hikmet Tanyu". SMSR. 77 (1): 137–54.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Baldick, Julian (2000). Animals and shaman: ancient religions of Central Asia. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 9780814798720.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Balzer, Marjorie Mandelstam, ed. (2015) [1990]. Shamanism: Soviet Studies of Traditional Religion in Siberia and Central Asia. London/New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781138179295.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beydili, Celal (2005). Türk Mitolojisi Ansiklopedik Sözlük [Turkic Mythology Encyclopedic Dictionary] (in التركية). İstanbul: Yurt Kitap-Yayın. ISBN 9759025051.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bourdeaux, Michael; Filatov, Sergey, eds. (2006). Современная религиозная жизнь России. Опыт систематического описания [Contemporary Religious Life of Russia. Systematic description experience] (in الروسية). Vol. 4. Москва: Keston Institute; Логос. ISBN 5-98704-057-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brent, Peter (1976). The Mongol Empire: Genghis Khan: His Triumph and his Legacy. London: Book Club Associates.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dilek, İbrahim (2013). Türk Mitoloji Sözlüğü (Altay-Yakut) [Turkic Mythology Dictionary (Altai-Yakut)] (in التركية). İstanbul: Gazi Kitabevi.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eröz, Mehmet (1992). Eski Türk dini (gök tanrı inancı) ve Alevîlik-Bektaşilik [Old Turkish Religion (Belief in Sky God) and Alevism-Bektashism] (in التركية) (3rd ed.). İstanbul: Türk Dünyası Araştırmaları Vakfı. ISBN 9789754980516.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Filatov, Sergey; Shchipkov, Aleksandr (1995). "Religious Developments among the Volga Nations as a Model for the Russian Federation" (PDF). Religion, State & Society. 23 (3): 233–48.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Golden, Peter Benjamin (1992). An introduction to the History of the Turkic peoples: ethnogenesis and state formation in medieval and early modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447032742.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gumilyov, Lev N. (1967). "Гл. 7. Религия тюркютов" [Chapter 7. Religion of the Turkuts]. Древние тюрки [The Ancient Turks] (in الروسية). Москва: Наука.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Güngör, Harun (2013). Erdoğan Altinkaynak (ed.). "Tengrism as a religious and political phenomenon in Turkish World: Tengriyanstvo" (PDF). KARADENİZ – BLACK SEA – ЧЕРНОЕ МОРЕ. 19: 189–95. ISSN 1308-6200.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Güngör, Harun; Günay, Ünver (1997). Başlangıçtan Günümüze Türklerin Dinî Tarihi [The Religious History of Turks from the Past to the Present] (in التركية). İstanbul.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Halemba, Agnieszka (2003). "Contemporary religious life in the Republic of Altai: the interaction of Buddhism and Shamanism" (PDF). Sibirica. 3 (2): 165–82. doi:10.1080/1361736042000245295.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heissig, Walther (1980) [1970]. The religions of Mongolia. Translated by G. Samuel. London/Henley: Routledge; Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7103-0685-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kafesoğlu, İbrahim (1980). Eski Türk Dini [Old Turkish Religion] (in التركية). Ankara: Boğaziçi Yayınları.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Khvastunova, Julia V. (2018). "Современное тенгрианство (на примере версии тенгрианства В. А. Сата в Республике Алтай)" [Modern Tengriism (as in V. A. Sat's Version of Tengriism in the Altai Republic]. Colloquium heptaploremes (in الروسية) (5).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Klyashtornyj, Sergei G. (2008). Spinei, V. and C. (ed.). Old Turkic Runic Texts and History of the Eurasian Steppe. Bucureşti/Brăila: Editura Academiei Române; Editura Istros a Muzeului Brăilei.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2005). 'Political Background of the Old Turkic Religion' in: Oelschlägel, Nentwig, Taube (eds), "Roter Altai, gib dein Echo!" (FS Taube), Leipzig, pp. 260–65. ISBN 978-3-86583-062-3

- Kodar, Auezkhan (2009). "Тенгрианство в контексте монотеизма" [Tengriism in context of monotheism]. Новые исследования Тувы (in الروسية) (1–2).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Laruelle, Marlène (2007). "Religious revival, nationalism and the 'invention of tradition': political Tengrism in Central Asia and Tatarstan". Central Asian Survey. 26 (2): 203–16. doi:10.1080/02634930701517433.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Laruelle, Marlène (2006-03-22). "Tengrism: In Search for Central Asia's Spiritual Roots" (PDF). Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst. 8 (6): 3–4. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2006-12-07.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Ögel, Bahaeddin (2003) [1971]. Türk Mitolojisi (Kaynakları ve Açıklamaları ile Destanlar) (in التركية) (4 ed.). Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pettazzoni, Raffaele (1956) [1955]. "Turco-Mongols and Related Peoples". The All-Knowing God. Researches into Early Religion and Culture. Translated by H. J. Rose. London.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Poemer, H. R., ed. (2000). History of the Turkic Peoples in Pre-Islamic Period. Berlin: Klaus-Schwarz-Verlag. ISBN 9783879972838.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Popov, Igor (2016). "Тюрко-монгольские религии (тенгрианство)" [Turko-Mongolic Religions (Tengrism)]. Справочник всех религиозных течений и объединений в России [The Reference Book on All Religious Branches and Communities in Russia] (in الروسية). Retrieved 2019-11-23.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Richtsfeld, Bruno J. (2004). "Rezente ostmongolische Schöpfungs-, Ursprungs- und Weltkatastrophenerzählungen und ihre innerasiatischen Motiv- und Sujetparallelen". Münchner Beiträge zur Völkerkunde. Jahrbuch des Staatlichen Museums für Völkerkunde München (in الألمانية). Vol. 9. pp. 225–74.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Róna-Tas, A. (1987). W. Heissig; H.-J. Klimkeit (eds.). "Materialien zur alten Religion den Turken: Synkretismus in den Religionen zentralasiens" [Materials on the ancient religion of the Turks: syncretism in the religions of Central Asia]. Studies in Oriental Religions (in الألمانية). Wiesbaden. 13: 33–45.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorlink1=ignored (|editor-link1=suggested) (help) - Roux, Jean-Paul, ed. (2003) [2002]. Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire. Abrams Discoveries. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - Roux, Jean-Paul, ed. (1984). La religion des Turcs et des Mongols [The Religion of the Turks and Mongols] (in الفرنسية). Paris: Payot.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editormask=ignored (|editor-mask=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Roux, Jean-Paul (1956). "Tängri. Essai sur le ciel-dieu des peuples altaïques" [Tängri. An Essay on the Deities of the Altaic Peoples]. Revue de l'histoire des religions (in الفرنسية).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) Vol. 149 (149-1), pp. 49–82; Vol. 149 (149-2), pp. 197–230; Vol. 150 (150-1), pp. 27–54; Vol. 150 (150-2), pp. 173–212. - ——— . Tengri. In: Encyclopedia of Religion, Vol. 13, pp. 9080–82.

- Saraçoǧlu, Cenk (2004). Nihal Atsiz's World-view and Its Influences on the Shared Symbols, Rituals, Myths and Practices of the Ülkücü Movement. Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shimamura, Ippei (2014). The Roots Seekers: Shamamisn and Ethnicity Among the Mongol Buryats. Yokohama: Shumpusha. ISBN 978-4-86110-397-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shnirelman, Viktor A. (1996). Who Gets the Past?: Competition for Ancestors Among Non-Russian Intellectuals in Russia. Washington D.C., Baltimore & London: Woodrow Wilson Center Press; Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801852213.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stebleva, Irina V. (1971). "К реконструкции древнетюркской мифологической системы" [To the reconstruction of the ancient Turkic mythological system]. Тюркологический сборник (in الروسية). Москва: АН СССР.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tanyu, Hikmet (1980). İslâmlıktan Önce Türkler'de Tek Tanrı İnancı [The Belief of Monotheism among Pre-Islamic Turks] (in التركية). İstanbul.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tekin, Talât (1993). Irk Bitig = The Book of Omens. Turcologica, 18. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-03426-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - The Secret History of the Mongols: a Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century. Inner Asian library. Vol. 1–2. Translated by Igor de Rachewiltz with a historical and philological commentary. Leiden: Brill. 2004 [1971–85]. ISBN 978-90-04-15363-9.

- Turner, Kevin (2016). Sky Shamans of Mongolia: Meetings with Remarkable Healers. Berkeley, Ca: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 9781583946343.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vovina, Olessia (2000). In Search of the National Idea: Cultural Revival and Traditional Religiosity in the Chuvash Republic (PDF). Seton Hall University.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

مؤلفون تنگريون معاصرون

- Adji, Murad (2005) [1998]. Asia’s Europa. Vol. 1: Europe, Turkic, the Great Steppe. Translated by A. Kisilev. Moscow: ACT.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Adyg-Tulush, Kara-ool Dopchun-ool oglu (2019) [2014]. Мистические тувинцы — скифы, хунны, тюрки Уранхая. Мистические шаманские видения Верховного шамана Тувы и России [The Mystical Tuvans—Scythians, Huns, Turks of Urankhai. Mystical Shamanic Visions of the Supreme Shaman of Tuva and Russia] (in التوفية) (2nd rev. ed.). Кызыл: "Адыг-Ээрен – Дух Медведя".

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Afanasyev, Lazar A. (Téris) (1993). Айыы уорэҔэ [Teachings of Aiyy] (in الساخيّة). Якутск: Министерство культуры Республики Саха (Якутия).

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Akatai, Sabetkazy N. (2011) [1990]. Күн мен көлеңке: ғылыми-танымдық аңсар; Тарихи материалдар [The Sun and Shadow: Science and Education; Historical materials] (in الكازاخستانية). Алматы: Print-Express. ISBN 978-601-7046-23-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Atabek, Aron (2000). Йоллыг-Тегин. Памятник Куль-Тегина [Yollig Tegin. Kul Tegin Monument] (in الروسية). Алматы: Кенже-пресс.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Atsiz, Hüseyin Nihâl (1966). Türk Tarihinde Meseleler [Problems in Turkish History] (in التركية). Ankara: Afşın Yayınları.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ayupov, Nurmagambet G. (2012). Тенгрианство как открытое мировоззрение [Tengrism as an Open Worldview] (PDF) (in الروسية). Алматы: КазНПУ им. Абая; КИЕ.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bezertinov, Rafael (2000). "Chapter 3. Deities / Trans. by N. Kisamov". Тенгрианство — религия тюрков и монголов [Tengrianizm: The Religion of the Turks and Mongols] (in الروسية). Набережные Челны: Аяз.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bira, Shagdaryn (2011). Монголын тэнгэрийн үзэл: түүвэр зохиол, баримт бичгүүд [Mongolian Tenggerism: selected papers and documents] (in المنغولية). Улаанбаатар: Содпресс. ISBN 9789992955932.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Butanayev, Victor Y. (2003). Бурханизм тюрков Саяно-Алтая [Burkhanism of the Turks of Sayano-Altai] (in الروسية). Абакан: Изд-во Хакасского государственного университета им. Н. Ф. Катанова. ISBN 5-7810-0226-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Devbash, Firdus (2011) [2009]. Татарские молитвы [Tatar Prayers] (in الروسية) (2nd rev. ed.). Казань: ПФ "Гарт". ISBN 978-5-905372-03-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fyodorova, Lena V. (2012). Духовные основы евразийства. Культурно-цивилизационные аспекты [The Spiritual Foundations of Eurasianism. Cultural and Civilizational Aspects] (in الروسية). Lambert Academic Publishing. ISBN 978-3-659-13666-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kenin-Lopsan, Mongush B. (1993). Магия тувинских шаманов = Magic of Tuvan Shamans (in Tuvan, الروسية, and الإنجليزية). Кызыл: Новости Тувы.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Kenin-Lopsan, Mongush B. (2010) [2002]. Calling the Bear Spirit: Ancient Shamanic Invocations and Working Songs from Tuva. Kristianstad: Kjellin. ISBN 9789197831901.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kodar, Auezkhan (2005) [2002]. The Steppe Knowledge. Essays on Cultural Science. Translated by I. Poluyahtov. Almaty: Ассоциация "Золотой век".

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Omuraliyev, Choiun (1994). Теңирчилик: Улуттук философиянын уңусуна чалгын [Tengrism: National Philosophy] (in القيرغيزية). Бишкек: Крон.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Omuraliyev, Choiun (2012). Теңирчилик: Коом-Мамлекет [Tengrism: Society–State] (in القيرغيزية). Бишкек: Кыргыз Жер. ISBN 978-9967-26-597-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sarygulov, Dastan (2002). Тенгрианство и глобальные проблемы современности [Tengrism and Global Problems of Modernity] (in الروسية). Бишкек: Фонд Тенгир-Ордо. ISBN 9967-21-186-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Suleimenov, Olzhas O. (1975). АЗ и Я. Книга благонамеренного читателя [AZ-and-IA. Book of a well-meaning reader] (in الروسية). Алма-Ата: Жазушы.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Suleimenov, Olzhas O. (2002). Тюрки в доистории (о происхождении древнетюркских языков и письменностей) [The Turks in Prehistory (on the origin of the ancient Turkic languages and scripts)] (in الروسية). Алматы: Атамұра. ISBN 9965-05-662-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stewart, Julie (1997-10-03). "A Course in Mongolian Shamanism—Introduction 101". Ulaanbaatar: Golomt Center for Shamanist Studies. Retrieved 2019-12-15.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Trer, Yosif (2019). Хӗрӗх чалӑш хӗрлӗ ту [Forty Fathoms Red Mountain] (in التشوفاشي). Шупашкар: ÇИП.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tschinag, Galsan (2006) [1994]. The Blue Sky: A Novel. Translated by K. Rout. Minneapolis, Minn: Milkweed Editions. ISBN 978-1-571310-55-2.

.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tsyrendorzhiev, Bair Zh.; Dogbaeva-Rinchino, M. R. (2019). Тэнгэридэ шүтэлгэ. Элинсэг хулинсагаймнай уряа. "Угай хүндэ" гэжэ үргэл, заншал = Тэнгэрианство. Зов предков. Почитание рода [Tengrism. The Call of the Ancestors. Veneration of the Kind] (in البرياتية and الروسية). Улан-Удэ: Республиканская типография. ISBN 978-5-91407-189-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Urbanaeva, Irina S. (2000). Шаманская философия бурят-монголов: центральноазиатское тэнгрианство в свете духовных учений: в 2 ч. [Shamanistic Philosophy of the Buryat-Mongols: Central Asian Tengrism in the Light of Spiritual Teachings: In 2 parts] (in الروسية). Улан-Удэ: БНЦ СО РАН. ISBN 5-7925-0024-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

وصلات خارجية

- International Fund of Tengri Research — official website (in روسية)

- TÜRIK BITIG — Turkic Inscriptions and Manuscripts, and Learn Old Turkic Writings — website of Language Committee of Ministry of Culture and Information of the جمهورية قزخستان (in قزخ, روسية, and إنگليزية)

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Pages with ISBN errors

- Articles with روسية-language sources (ru)

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles containing Old Turkic-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing منغولية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2019

- CS1 التركية-language sources (tr)

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 foreign language sources (ISO 639-2)

- CS1 الكازاخستانية-language sources (kk)

- CS1 المنغولية-language sources (mn)

- CS1 القيرغيزية-language sources (ky)

- CS1 التشوفاشي-language sources (cv)

- Articles with قزخ-language sources (kk)

- Articles with إنگليزية-language sources (en)

- تنگرية

- أساطير توركية

- شامانية آسيوية

- ديانات عرقية

- ديانات توحيدية