ستانلي بالدوِن

الإيرل ستانلي بالدوِن | |||

|---|---|---|---|

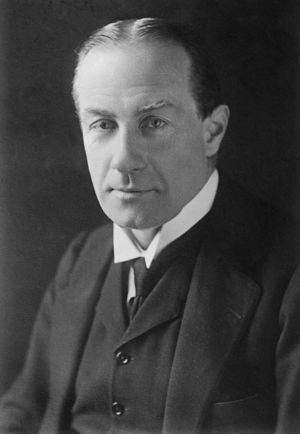

بالدوِن في العشرينيات | |||

| رئيس وزراء المملكة المتحدة | |||

| في المنصب 7 يونيو 1935 – 28 مايو 1937 | |||

| العاهل | جورج الخامس إدوارد الثامن جورج السادس | ||

| سبقه | رامزي مكدونالد | ||

| خلـَفه | نڤيل تشمبرلين | ||

| في المنصب 4 نوفمبر 1924 – 5 يونيو 1929 | |||

| العاهل | جورج الخامس | ||

| سبقه | رامزي مكدونالد | ||

| خلـَفه | رامزي مكدونالد | ||

| في المنصب 23 مايو 1923 – 16 يناير 1924 | |||

| العاهل | جورج الخامس | ||

| سبقه | أندرو بونار لو | ||

| خلـَفه | رامزي مكدونالد | ||

| Lord President of the Council | |||

| في المنصب 24 August 1931 – 7 June 1935 | |||

| رئيس الوزراء | Ramsay MacDonald | ||

| سبقه | The Lord Parmoor | ||

| خلـَفه | Ramsay MacDonald | ||

| |||

| وزير الخزانة | |||

| في المنصب 27 أكتوبر 1922 – 27 أغسطس 1923 | |||

| رئيس الوزراء | بونار لو | ||

| سبقه | السير روبرت هورن | ||

| خلـَفه | نڤيل تشمبرلين | ||

| رئيس مجلس التجارة | |||

| في المنصب 1 أبريل 1921 – 19 أكتوبر 1922 | |||

| رئيس الوزراء | ديڤيد لويد جورج | ||

| سبقه | سير روبرت هورن | ||

| خلـَفه | سير فليپ لويد-گريم | ||

| عضو البرلمان عن {{{constituency_عضو البرلمان}}} | |||

| في المنصب 29 فبراير 1908 – 30 يونيو 1937 | |||

| سبقه | ألفرد بالدوِن | ||

| خلـَفه | روجر كونات | ||

| |||

| |||

| تفاصيل شخصية | |||

| وُلِد | Stanley Baldwin 3 أغسطس 1867 بيودلي، ووسترشاير، إنگلترة | ||

| توفي | 14 ديسمبر 1947 (aged 80) ستاورپورت-على-سڤرن، ووسترشاير، إنگلترة | ||

| المثوى | كاتدرائية ووستر | ||

| القومية | بريطاني | ||

| الحزب | المحافظون | ||

| الزوج | |||

| الأنجال | 6، منهم أوليڤر ريدسديل و آرثر وندام | ||

| الوالدان | ألفرد بالدوِن لويزا مكدونالد | ||

| التعليم | |||

| المهنة | رجل صناعة | ||

| التوقيع | |||

ستانلي بالدوِن، إيرل أول بالدوِن من بودلي Stanley Baldwin KG, PC, JP, FRS[1] (3 أغسطس 1867 – 14 ديسمبر 1947)، هو سياسي من محافظ بريطاني الذي سيطر على الحكومة في بلاده ما بين الحربين العالميتين. تقلد منصب رئيس الوزراء ثلاث مرات، وهو رئيس الوزراء الوحيد الذي خدم في عهد ثلاثة ملوك (جورج الخامس، إدوارد الثامن وجورج السادس).[2]

دخل بالدوِن مجلس العموم لأول مرة عام 1908 كعضو في البرلمان عن بودلي، خلـَفاً لوالده ألفرد بالدوِن. تقلد منصباً حكومياً في وزارة ديڤيد لويد جورج الائتلافية. عام 1922، كان بالدوِن واحداً من المحركين الرئيسيين في انسحاب دعم المحافظين عن لويد جورج؛ بعد ذلك أصبح مستشار الخزانة في وزارة بونار لو. عند استقالة بونار لو لأسباب صحية في مايو 1923، أصبح بالدوِن رئيساً للوزراء وحزب المحافظين. نادى بعقد انتخابات حول موضوع التعريفة الجمركية وفقدان الأغلبية لحزب المحافظين، بعد إصلاح رامزي مكدونالد حكومة حزب العمال ذات الأقلية.

بعد فوزه في الانتخابات العام 1924 قام بالدوِن بتشكل ثاني حكوماته، والتي شهدت وزراء بارزون مثل سير أوستن شامبرلين (وزير الخارجية)، ونستون تشرشل (وزير الخزانة)، ونڤيل تشمبرلين (وزير الصحة). عززا الوزيران الأخيران موقف المحافظين بعمل إصلاحات في الجوانب السابقة التي ارتبطت بحزب العمال. وتضمنت المصالحة الصناعية، التأمين ضد البطالة، ونظام معاشات أكثر شمولاً لكبار السن، إزالة الأحياء الفقيرة، المزيد من الإسكان الخاص، والتوسع في رعاية الأم والطفل. ومع ذلك، فقد أدى استمرار بطء النمو الاقتصادي والتراجع في التعدين والصناعات الثقيلة إلى إضعاف قاعدة دعمه، وبالرغم من تشكيل سياسيي حزب العمال الداعمين لحكومات أقليات صغيرة في وستمنستر، إلا أن حكومته شهدت أيضاً إضراباً عاماً عام 1926 وقانون النزاعات التجارية لعام 1927 للحد من صلاحيات النقابات العمالية.[3]

في الانتخابات العامة 1929 خسر بالدوِن بفارق صغير وكانت زعامته المستمرة للحزب محل نقد كبير من قبل باروني الإعلام لورد روثرمير ولورد بيڤربروك. عام 1931، قام رئيس وزراء حزب العمال رامزي مكدونالد بتشكيل حكومة وطنية، معظم وزرائها من المحافظين والذين فازوا بالأغلبية في الانتخابات العامة 1931. كلورد رئيس للمجلس، وكواحداً من المحافظين الأربعة ضمن مجلس الوزراء المكون من تسعة أعضاء، سيطر بالدوِن على الكثير من مهام رئاسة الوزراء بسبب المتاعب الصحية التي أصابت مكدونالد. شهدت حكومته إقرار قانون لزيادة صلاحيات الحكم الذاتي في الهند، التدبير الذي لقى معارضة من تشرشل والكثير من كبار المحافظين. أعطى دستور وستمنستر 1931 وضع السيادة على كندا، أستراليا، نيوزيلندا وجنوب أفريقيا، بينما بدأت أول خطوة تجاه تأسيس عصبة الأمم. كزعيم حزب، قام بالدوٍن بالكثير من الإبتكارات المذهلة، مثل الاستخدام الذكي للإذاعة والسينما، مما جعله الأكثر ظهوراً للعامة، وقد دعم ذلك صورة المحافظين.

عام 1935، خلف بالدوٍن مكدونالد كرئيس لوزراء الحكومة الوطنية، وفاز في الانتخابات العامة 1935 بأغلبية كبيرة أخرى، والتي تعتبر آخر مرة يحصل فيها حزب سياسي على أكثر من 50% من الأصوات في انتخابات عامة بالمملكة المتحدة. في ذلك الوقت، أشرف بالدوٍن على بدء إعادة تسليح الجيش البريطاني، وكذلك عملية تنازل الملك إدوارد الثامن عن العرش بالغة الصعوبة. شهدت حكومة بالدوٍن الثالثة عدداً من الأزمات في العلاقات الخارجية، ومنها الضجة العامة التي أثيرت حول حلف هور-لاڤال، إعادة عسكرة الراينلاند واندلاع الحرب الأهلية الإسپانية.

تقاعد بالدوٍن عام 1937 وخلفه نڤيل تشمبرلين. في ذلك الوقت، كان ينظر لبالدوِن على أنه رئيس الوزراء الأكثر شعبية والأكثر نجاحاً،[4] لكن العقد الأخير من حياته، ولعدد من السنوات بعدها، كان مخيباً إذ ارتفعت نسبة البطالة في الثلاثينيات وكأحد "الرجال المذنبين" الذين حاولوا استرضاء أدولف هتلر والذين- من المفترض- أنهم تأخروا بما فيه الكفاية للإعداد للحرب العالمية الثانية.

حياته المبكرة: العائلة، التعليم والزواج

الحياة السياسية المبكرة

دخوله مجلس الوزراء

وزير الخزانة

In late 1922 dissatisfaction was steadily growing within the Conservative Party over its coalition with the Liberal David Lloyd George. At a meeting of Conservative MPs at the Carlton Club in October, Baldwin announced that he would no longer support the coalition, and famously condemned Lloyd George for being a "dynamic force" that was bringing destruction across politics. The meeting chose to leave the coalition, against the wishes of most of the party leadership. As a direct result Bonar Law was forced to search for new ministers for a Cabinet which he would lead, and so promoted Baldwin to the position of Chancellor of the Exchequer. In the November 1922 general election the Conservatives were returned with a majority in their own right.[بحاجة لمصدر]

رئاسة الوزراء: الفترة الأولى (1923–1924)

Appointment

In May 1923 Bonar Law was diagnosed with terminal cancer and retired immediately; he died five months later. With many of the party's senior leading figures standing aloof and outside of the government, there were only two candidates to succeed him: Lord Curzon, the foreign secretary, and Baldwin. The choice formally fell to King George V acting on the advice of senior ministers and officials.[بحاجة لمصدر]

It is not entirely clear what factors proved most crucial, but some Conservative politicians felt that Curzon was unsuitable for the role of prime minister because he was a member of the House of Lords. Curzon was strong and experienced in international affairs, but his lack of experience in domestic affairs, his personal character quirks and his huge inherited wealth and many directorships at a time when the Conservative Party was seeking to shed its patrician image were all deemed impediments. Much weight at the time was given to the intervention of Arthur Balfour.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The King turned to Baldwin to become prime minister. Initially Baldwin was also Chancellor of the Exchequer whilst he sought to recruit the former Liberal Chancellor Reginald McKenna to join the government. When this failed he appointed Neville Chamberlain to that position.[بحاجة لمصدر]

1923 general election

The Conservatives now had a clear majority in the House of Commons and could govern for five years before holding a general election, but Baldwin felt bound by Bonar Law's pledge at the previous election that there would be no introduction of tariffs without a further election. Thus Baldwin turned towards a degree of protectionism which would remain a key party message during his lifetime.[5] With the country facing growing unemployment in the wake of free trade imports driving down prices and profits, Baldwin decided to call an early general election in December 1923 to seek a mandate to introduce protectionist tariffs which, he hoped, would drive down unemployment and spur an economic recovery.[6] He expected to unite his party but he divided it, for protectionism proved a divisive issue.[7] The election was inconclusive: the Conservatives had 258 MPs, Labour 191 and the reunited Liberals 159. Whilst the Conservatives retained a plurality in the House of Commons, they had been clearly defeated on the central issue: tariffs.[8] Baldwin remained prime minister until the opening of the new Parliament in January 1924, when his administration was defeated in a vote on its legislative programme set out in the King's Speech. He offered his resignation to George V immediately.[بحاجة لمصدر]

زعيم المعارضة (1924)

Baldwin successfully held on to the party leadership amid some colleagues' calls for his resignation.[9] For the next ten months, an unstable minority Labour government under Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald held office. On 13 March 1924, the Labour government was defeated for the first time in the Commons, although the Conservatives decided to vote with Labour later that day against the Liberals.[10]

During a debate on the naval estimates the Conservatives opposed Labour but supported them on 18 March in a vote on cutting expenditure on the Singapore military base.[10] Baldwin also cooperated with MacDonald over Irish policy to stop it becoming a party-political issue.[11][12]

The Labour government was negotiating with the Soviet government over intended commercial treaties – 'the Russian Treaties' – to provide most favoured nation privileges and diplomatic status for the UK trade delegation; and a treaty that would settle the claims of pre-revolutionary British bondholders and holders of confiscated property, after which the British government would guarantee a loan to the Soviet Union.[13] Baldwin decided to vote against the government over the Russian Treaties, which brought the government down on 8 October.[14]

1924 re-election

The general election held in October 1924 brought a landslide majority of 223 for the Conservative party, primarily at the expense of an unpopular Liberal Party. Baldwin campaigned on the "impracticability" of socialism, the Campbell Case, the Zinoviev letter (which Baldwin thought was genuine, and the Conservatives leaked to the Daily Mail at a most damaging time to the Labour campaign; the letter is now widely believed to have been a forgery[15]) and the Russian Treaties.[16] In a speech during the campaign Baldwin said:

It makes my blood boil to read of the way which Mr. Zinoviev is speaking of the Prime Minister today. Though one time there went up a cry, "Hands off Russia", I think it's time somebody said to Russia, "Hands off England".[17]

رئاسة الوزراء: الفترة الثانية (1924–1929)

Cabinet

This section requires expansion. (March 2022) |

Baldwin's new Cabinet now included many former political associates of Lloyd George: former Coalition Conservatives: Austen Chamberlain (as foreign secretary), Lord Birkenhead (secretary for India) and Arthur Balfour (lord president after 1925), and the former Liberal Winston Churchill as chancellor of the exchequer. Baldwin created the Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies, a volunteer body of those opposed to the strike which was intended to complete essential work.[18]

Domestic affairs

Trade unions strike

A defining feature of Baldwin's Second term was the 1926 General Strike, Baldwin handled the strike by using powers awarded to him in the Emergency Powers Act 1920. He deployed the military and volunteers to keep essential services running. The strike ended when it was found to not be protected by the Trade Disputes Act 1906, leading to the strike being called off on 12 May lasting just 9 days. Baldwin's government was widely credited for such an effective response to the strike.[19]

At Baldwin's instigation Lord Weir headed a committee to "review the national problem of electrical energy". It published its report on 14 May 1925 and in it Weir recommended the setting up of a Central Electricity Board, a state monopoly half-financed by the Government and half by local undertakings. Baldwin accepted Weir's recommendations and they became law by the end of 1926.[20]

The Board was a success. By 1939 electrical output was up fourfold and generating costs had fallen. Consumers of electricity rose from three-quarters of a million in 1920 to nine million in 1938, with annual growth of 700,000 to 800,000 a year (the fastest rate of growth in the world).[20]

Social reforms

One of his legislative reforms was a paradigm shift in his party. This was the Widows', Orphans' and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act 1925 (15 & 16 Geo. 5. c. 70), which provided a pension of 10 shillings a week for widows with extra for children, and 10 shillings a week for insured workers and their wives at 65. This transformed Toryism, away from its historic reliance on community (particularly religious) charities, and towards acceptance of a humanitarian welfare state which would guarantee a minimum living standard for those unable to work or who took out national insurance.[21] In 1927, he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society.[22]

زعيم المعارضة (1929–1931)===

In 1929 Labour returned to office as the largest party in the House of Commons (although without an overall majority) despite obtaining fewer votes than the Conservatives.[23] In opposition, Baldwin was almost ousted as party leader by the press barons Lords Rothermere and Beaverbrook, whom he accused of enjoying "power without responsibility, the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages".[24]

Ramsden argues that Baldwin made dramatic permanent improvements to the organisation and effectiveness of the Conservative Party. He enlarged the headquarters with professionals, professionalised the party agents, raised ample funds, and was an innovative user of the new mass media of radio and film.[25]

اللورد الرئيس للمجلس (1931–1935)

By 1931, as the economy headed towards crisis, both in Britain and around the world, with the onset of the Great Depression, Baldwin and the Conservatives entered into a coalition with Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald.[26] This decision led to MacDonald's expulsion from his own party, and Baldwin, as Lord President of the Council, became de facto prime minister, deputising for the increasingly senile MacDonald, until he once again officially became prime minister in 1935.[بحاجة لمصدر]

One central and vitally important agreement was the Statute of Westminster 1931, which conferred full self-government upon the Dominions Canada, South Africa, Australia, the Irish Free State and New Zealand, while preparing the first steps towards the eventual Commonwealth of Nations, and away from the designation 'British Empire'.[27] In 1930, the first British Empire Games sports competition was held successfully among Empire nations in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.[بحاجة لمصدر]

His government then secured with great difficulty the passage of the landmark Government of India Act 1935, in the teeth of opposition from Winston Churchill, spokesman for the die-hard imperialists who filled the Conservative ranks.[28]

نزع السلاح

Baldwin did not advocate total disarmament, but believed that, as Lord Grey of Falloden had stated in 1925, "great armaments lead inevitably to war".[29] However, he came to believe that, as he put it on 10 November 1932: "the time has now come to an end when Great Britain can proceed with unilateral disarmament".[30] On 10 November 1932 he said:

I think it is well also for the man in the street to realise that there is no power on earth that can protect him from being bombed. Whatever people may tell him, the bomber will always get through, The only defence is in offence, which means that you have to kill more women and children more quickly than the enemy if you want to save yourselves...If the conscience of the young men should ever come to feel, with regard to this one instrument [bombing] that it is evil and should go, the thing will be done; but if they do not feel like that – well, as I say, the future is in their hands. But when the next war comes, and European civilisation is wiped out, as it will be, and by no force more than that force, then do not let them lay blame on the old men. Let them remember that they, principally, or they alone, are responsible for the terrors that have fallen upon the earth.[30]

This speech was often used against Baldwin as allegedly demonstrating the futility of rearmament or disarmament, depending on the critic.[31]

With the second part of the Disarmament Conference starting in January 1933, Baldwin attempted to see through his hope of air disarmament.[32] However, he became alarmed at Britain's lack of defence against air raids and German rearmament, saying it "would be a terrible thing, in fact, the beginning of the end".[33] In April 1933 the Cabinet agreed to follow through with the construction of the Singapore military base.[34]

On 15 September 1933, the German delegate at the Disarmament Conference refused to return to the Conference, and Germany left altogether in October. Baldwin, in a speech on 6 October to the Conservative Party Conference in Birmingham, pleaded for a Disarmament Convention, and then said:

when I speak of a Disarmament Convention I do not mean disarmament on the part of this country and not on the part of any other. I mean the limitation of armaments as a real limitation...and if we find ourselves on some lower rating and that some other country has higher figures, that country has to come down and we have to go up until we meet.[35]

Germany left the League of Nations on 14 October. The Cabinet decided on 23 October that Britain should still attempt to cooperate with other states, including Germany, in international disarmament.[36] However between mid-September 1933 and the beginning of 1934 Baldwin's mind changed from hoping for disarmament to favouring rearmament, including parity in aircraft.[37] In late 1933 and early 1934 he rejected an invitation from Hitler to meet him, believing that visits to foreign capitals were the job of Foreign Secretaries.[38] On 8 March 1934, Baldwin defended the creation of four new squadrons for the Royal Air Force against Labour criticisms, and said of international disarmament:

If all our efforts for an agreement fail, and if it is not possible to obtain this equality in such matters as I have indicated, then any Government of this country—a National Government more than any, and this Government—will see to it that in air strength and air power this country shall no longer be in a position inferior to any country within striking distance of our shores.[39]

On 29 March 1934 Germany published its defence estimates, which showed a total increase of one-third and an increase of 250% in its air force.[40]

A series of by-elections in late 1933 and early 1934 with massive swings against government candidates—most famous was Fulham East with a 26.5% swing— convinced Baldwin that the British public was profoundly pacifist.[41] Baldwin also rejected the "belligerent" views of those like Churchill and Robert Vansittart because he believed that the Nazis were rational men who would appreciate the logic of mutual and equal deterrence.[42] He also believed war to be "the most fearful terror and prostitution of man's knowledge that ever was known".[43]

رئاسة الوراء: الفترة الثالثة: (1935–1937)

National Government and appointment

With MacDonald's health in decline, he and Baldwin changed places in June 1935: Baldwin was now prime minister, MacDonald Lord President of the council.[44] In October that year, Baldwin called a general election. Neville Chamberlain advised Baldwin to make rearmament the leading issue in the election campaign against Labour and said that if a rearmament programme was not announced until after the election, his government would be seen as having deceived the people.[45] However, Baldwin did not make rearmament the central issue in the election. He said that he would support the League of Nations, modernise Britain's defences and remedy deficiencies, but he also said: "I give you my word that there will be no great armaments".[46] The main issues in the election were housing, unemployment and the special areas of economic depression.[46] The election gave 430 seats to National Government supporters (386 of these Conservative) and 154 seats to Labour.

Rearmament

Baldwin's younger son A. Windham Baldwin, writing in 1955, argued that his father, Stanley, had planned a rearmament programme as early as 1934 but had to do so quietly to avoid antagonising the public, whose pacifism was revealed by the Peace Ballot of 1934–35 and endorsed by both the Labour and the Liberal oppositions. His thorough presentation of the case for rearmament in 1935, his son argued, defeated pacifism and secured a victory that allowed rearmament to move ahead.[47]

On 31 July 1934, the Cabinet approved a report that called for expansion of the Royal Air Force to the 1923 standard by creating 40 new squadrons over the next five years.[48] On 26 November 1934, six days after receiving the news that the German air force would be as large as the RAF within one year, the Cabinet decided to speed up air rearmament from four years to two.[49] On 28 November 1934, Churchill moved an amendment to the vote of thanks for the King's Speech: "the strength of our national defences, and especially our air defences, is no longer adequate".[50] His motion was known eight days before it was moved, and a special Cabinet meeting decided how to deal with the motion, which dominated two other Cabinet meetings.[51] Churchill said Germany was rearming and requested that the money spent on air armaments be doubled or tripled to deter an attack and that the Luftwaffe was nearing equality with the RAF.[52] Baldwin responded by denying that the Luftwaffe was approaching equality and said it was "not 50 per cent" of the RAF. He added that by the end of 1935 the RAF would still have "a margin of nearly 50 per cent" in Europe.[53] After Baldwin said that the government would ensure the RAF had parity with the future German air force, Churchill withdrew his amendment. In April 1935, the Air Secretary reported that although Britain's strength in the air would be ahead of Germany's for at least three years, air rearmament needed to be increased; so the Cabinet agreed to the creation of an extra 39 squadrons for home defence by 1937.[49] However, on 8 May 1935, the Cabinet heard that it was estimated that the RAF was inferior to the Luftwaffe by 370 aircraft and that to reach parity, the RAF must have 3,800 aircraft by April 1937, an extra 1,400 above the existing air programme. It was learnt that Germany was easily able to outbuild that revised programme as well.[54] On 21 May 1935, the Cabinet agreed to expanding the home defence force of the RAF to 1,512 aircraft (840 bombers and 420 fighters).[49] On 22 May 1935 Baldwin confessed in the Commons, "I was wrong in my estimate of the future. There I was completely wrong."[55]

On 25 February 1936, the Cabinet approved a report calling for expansion of the Royal Navy and the re-equipment of the British Army (though not its expansion), along with the creation of "shadow factories" built by public money and managed by industrial companies. The factories came into operation in 1937. In February 1937, the Chiefs of Staff reported that by May 1937, the Luftwaffe would have 800 bombers, compared to the RAF's 48.[56]

In the debate in the Commons on 12 November 1936, Churchill attacked the government on rearmament as being "decided only to be undecided, resolved to be irresolute, adamant for drift, solid for fluidity, all-powerful to be impotent. So we go on, preparing more months and years – precious, perhaps vital, to the greatness of Britain – for the locusts to eat". Baldwin replied:

I put before the whole House my own views with an appalling frankness. From 1933, I and my friends were all very worried about what was happening in Europe. You will remember at that time the Disarmament Conference was sitting in Geneva. You will remember at that time there was probably a stronger pacifist feeling running through the country than at any time since the War. I am speaking of 1933 and 1934. You will remember the election at Fulham in the autumn of 1933.... That was the feeling of the country in 1933. My position as a leader of a great party was not altogether a comfortable one. I asked myself what chance was there... within the next year or two of that feeling being so changed that the country would give a mandate for rearmament? Supposing I had gone to the country and said that Germany was rearming and we must rearm, does anybody think that this pacific democracy would have rallied to that cry at that moment! I cannot think of anything that would have made the loss of the election from my point of view more certain.... We got from the country – with a large majority – a mandate for doing a thing that no one, twelve months before, would have believed possible.[57]

Churchill wrote to a friend: "I have never heard such a squalid confession from a public man as Baldwin offered us yesterday".[58] In 1935 Baldwin wrote to J. C. C. Davidson in a letter now lost that said of Churchill: "If there is going to be a war – and no one can say that there is not – we must keep him fresh to be our war Prime Minister".[59] Thomas Dugdale also claimed Baldwin said to him: "If we do have a war, Winston must be Prime Minister. If he is in [the Cabinet] now we shan't be able to engage in that war as a united nation".[59] The General Secretary of the Trades Union Congress, Walter Citrine, recalled a conversation he had had with Baldwin on 5 April 1943: "Baldwin thought his [Churchill's] political recovery was marvellous. He, personally, had always thought that if war came Winston would be the right man for the job".[60]

The Labour Party strongly opposed the rearmament programme. Clement Attlee said on 21 December 1933: "For our part, we are unalterably opposed to anything in the nature of rearmament".[61] On 8 March 1934, Attlee said, after Baldwin defended the Air Estimates, "we on our side are out for total disarmament".[39] On 30 July 1934, Labour moved a motion of censure against the government because of its planned expansion of the RAF. Attlee spoke for it: "We deny the need for increased air arms...and we reject altogether the claim of parity".[61] Stafford Cripps also said on that occasion that it was fallacy that Britain could achieve security through increasing air armaments.[61] On 22 May 1935, the day after Hitler had made a speech claiming that German rearmament offered no threat to peace, Attlee asserted that Hitler's speech gave "a chance to call a halt in the armaments race".[62] Attlee also denounced the Defence White Paper of 1937: "I do not believe the Government are going to get any safety through these armaments".[63]

تنازل إدوارد الثامن عن العرش

The accession of King Edward VIII, and the ensuing abdication crisis, brought Baldwin's last major test in office. The new monarch was "an ardent exponent of the cause of Anglo-German understanding" and had "strong views on his right to intervene in affairs of state," but the "Government's main fears... were of indiscretion."[64] The King proposed to marry Wallis Simpson, an American woman who was twice divorced. The high-minded Baldwin felt that he could tolerate her as "a respectable whore" as long as she stayed behind the throne but not as "Queen Wally".[65]

Mrs. Simpson was also distrusted by the government for her known pro-German sympathies and was believed to be in "close contact with German monarchist circles".[64]

During October and November 1936, Baldwin joined the royal family in trying to dissuade the King from that marriage, arguing that the idea of having a twice-divorced woman as the Queen would be rejected by the government, by the country and by the Empire and that "the voice of the people must be heard."[66][67] As the public standing of the King would be gravely compromised, the Prime Minister gave him time to reconsider the notion of this marriage.[68] According to the historian Philip Williamson, "The offence lay in the implications of [the King's] attachment to Mrs. Simpson for the broader public morality and the constitutional integrity which were now perceived—especially by Baldwin—as underpinning the nation's unity and strength."[69]

News of the affair was broken in the newspapers on 2 December.[70] There was some support for the wishes of the King, especially in and around London. The romantic royalists Churchill, Mosley, and the press barons, Lord Beaverbrook of the Daily Express and Lord Rothermere of the Daily Mail, all declared that the king had a right to marry whichever woman he wished.[70] The crisis assumed a political dimension when Beaverbrook and Churchill tried to rally support for the marriage in Parliament.[71] However, the King's party could muster only 40 Members of Parliament in support,[72] and the majority opinion sided with Baldwin and his Conservative government.[70] The Labour leader, Clement Attlee, told Baldwin "that while Labour people had no objection to an American becoming Queen, [he] was certain they would not approve of Mrs. Simpson for that position", especially in the provinces and in the Commonwealth countries.[73] The Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Lang, held that the King, as the head of the Church of England, should not marry a divorcée.[74] The Times argued that the monarchy's prestige would be destroyed if "private inclination were to come into open conflict with public duty and be allowed to prevail".[70]

While some recent critics have complained that "Baldwin refused the reasonable request for time to reflect, preferring to keep the pressure on the King – once again suggesting that his own agenda was to force the crisis to a head" and that he "never mentioned that the alternative [to the marriage] was abdication",[75] the House of Commons immediately and overwhelmingly came out against the marriage.[71] The Labour and Liberal parties, the Trades Union Congress,[76] and the dominions of Australia and Canada, all joined the British cabinet in rejecting the King's compromise, initially supported and perhaps conceived by[77] Churchill,[78] for a morganatic marriage that had originally been made on 16 November.[71] The crisis threatened the unity of the British Empire, since the King's personal relationship with the Dominions was their "only remaining constitutional link".[79]

Baldwin still hoped that the King would choose the throne over Mrs. Simpson.[71] For the King to act against the wishes of the cabinet would have precipitated a constitutional crisis.[71] Baldwin would have had to resign,[80] and no other party leader would have served as the prime minister under the King,[68][70] with the Labour Party having already indicated that it would not form a ministry to uphold impropriety.[71] Baldwin told the Cabinet, one Labour MP had asked, "Are we going to have a fascist monarchy?"[76] When the Cabinet refused the morganatic marriage, Edward decided to abdicate.[70]

The King's final plea, on 4 December, to broadcast an appeal to the nation was rejected by the Prime Minister as too divisive.[71][81] Nevertheless, at his final audience with King Edward on 7 December, Baldwin offered to strive all night with the King's conscience, but he found Edward to be determined to go.[71] Baldwin announced the King's abdication in the Commons on 10 December. Harold Nicolson, an MP who witnessed Baldwin's speech, wrote in his diary:

There is no moment when he overstates emotion or indulges in oratory. There is intense silence broken only by the reporters in the gallery scuttling away to telephone the speech.... When it was over... [we] file out broken in body and soul, conscious that we have heard the best speech that we shall ever hear in our lives. There was no question of applause. It was the silence of Gettysburg...No man has ever dominated the House as he dominated it tonight, and he knows it.[82]

After the speech, the House adjourned and Nicolson bumped into Baldwin as he was leaving, who asked him what he thought of the speech. Nicolson said it was superb to which Baldwin replied: "Yes ... it was a success. I know it. It was almost wholly unprepared. I had a success, my dear Nicolson, at the moment I most needed it. Now is the time to go".[83]

The King abdicated on 11 December and was succeeded by his brother, George VI. Edward VIII was assigned the title of the Duke of Windsor by his brother and then married Mrs. Simpson in France in June 1937 after her divorce from Ernest Simpson had become final.

Baldwin had defused a political crisis by turning it into a constitutional question.[71] His discreet resolution met with general approval and restored his popularity.[70] He was praised on all sides for his tact and patience[71] and was not in the least put out by the protestors' cries of "God save the King—from Baldwin!" "Flog Baldwin! Flog him!! We—want—Edward."[84]

John Charmley argued in his history of the Conservative Party that Baldwin was pushing for more democracy and less of an old aristocratic upper-class tone. Monarchy was to be a national foundation by which the head of the Church, the State, and the Empire would draw upon 1000 years of tradition and could unify the nation. George V was an ideal fit: "an ordinary little man with the philistine tastes of most of his subjects, he could be presented as the archetypical English paterfamilias getting on with his duties without fuss." Charmley finds that George V and Baldwin, "made a formidable conservative team, with their ordinary, honest, English decency proving the first (and most effective) bulwark against revolution". Edward VIII, flaunting his upper-class playboy style, suffered from an unstable neurotic character and needed a strong stabilising partner, a role that Mrs. Simpson was unable to provide. Baldwin's final achievement was to smooth the way for Edward to abdicate in favour of his younger brother, who became George VI. Both father and son demonstrated the value of a democratic king during the severe physical and psychological hardships of the world wars, and the tradition was carried on by Elizabeth II.[85]

التقاعد

| جزء من سلسلة سياسية عن |

| فكر التوري |

|---|

|

ترك المنصب والنبالة

After the coronation of George VI, Baldwin announced on 27 May 1937 that he would resign the premiership the next day. His last act as prime minister was to raise the salaries of MPs from £400 a year to £600 and to give the leader of the Opposition a salary. That was the first rise in MPs' wages since their introduction in 1911, and it particularly benefited Labour MPs. Harold Nicolson wrote in his diary that it "was done with Baldwin's usual consummate taste. No man has ever left in such a blaze of affection".[86] Baldwin was appointed a Knight Companion of the Garter (KG) on 28 May[87] and ennobled as Earl Baldwin of Bewdley and Viscount Corvedale, of Corvedale in the County of Salop on 8 June.[71][88] In a BBC radio broadcast transmitted on 8 December 1938, Baldwin made a nationwide appeal for funds to help Jewish and other refugees fleeing persecution in Nazi Germany.[89] For this, Baldwin was dubbed a "guttersnipe" by a Berlin newspaper.[90] The "Lord Baldwin Fund for Refugees", helping the kindertransport and other relief schemes, raised over £500,000 [£36,000,000 in 2022] [91]

موقفه تجاه استرضاء هتلر

أيـّد بالدوِن اتفاقية ميونخ وقال لتشيمبرلين في 26 September 1938: "If you can secure peace, you may be cursed by a lot of hotheads but my word you will be blessed in Europe and by future generations".[92] Baldwin made a rare speech in the House of Lords on 4 October where he said he could not have gone to Munich but praised Chamberlain's courage and said the responsibility of a Prime Minister was not to commit the country to war until he was sure that it was ready to fight. If there was a 95% chance of war in the future, he would still choose peace. He also said he would put industry on a war footing tomorrow as the opposition to such a move had disappeared.[93] Churchill said in a speech: "He says he would mobilise tomorrow. I think it would have been much better if Earl Baldwin had said that two and a half years ago when everyone demanded a Ministry of Supply".[94]

Two weeks after Munich, Baldwin said (prophetically) in a conversation with Lord Hinchingbrooke: "Can't we turn Hitler East? Napoleon broke himself against the Russians. Hitler might do the same".[95]

Baldwin's years in retirement were quiet. After Chamberlain's death in 1940, Baldwin's perceived part in pre-war appeasement made him an unpopular figure during and after World War II.[96] With a succession of British military failures in 1940, Baldwin started to receive critical letters: "insidious to begin with, then increasingly violent and abusive; then the newspapers; finally the polemicists who, with time and wit at their disposal, could debate at leisure how to wound the deepest."[96] He did not have a secretary and so was not shielded from the often unpleasant letters sent to him.[97] After a bitterly critical letter was sent to him by a member of the public, Baldwin wrote: "I can understand his bitterness. He wants a scapegoat and the men provided him with one". His biographers Middlemas and Barnes claim that "the men" almost certainly meant the authors of Guilty Men.[98]

رسالة إلى اللورد هاليفاكس

أزمة البوابات الحديدية

تعليقات على السياسات

سنواته الأخيرة ووفاته

أسلوب الخطاب

- 1867–1897: Mr Stanley Baldwin

- 1897–1908: Mr Stanley Baldwin JP

- 1908–1920: Mr Stanley Baldwin MP JP

- 1920–1927: The Rt Hon Stanley Baldwin MP JP

- 1927–1937: The Rt Hon Stanley Baldwin MP JP FRS

- 1937: The Rt Hon Sir Stanley Baldwin KG MP JP FRS

- 1937–1947: The Rt Hon The Earl Baldwin of Bewdley KG PC JP FRS

ذكراه

حكومات بالدوِن كرئيساً للوزراء

الحكومة الأولى، مايو 1923 – يناير 1924

- بالدوِن– رئيس للوزراء، مستشار الخزانة وزعيم مجلس العموم

- Lord Cave – Lord Chancellor

- Lord Salisbury – Lord President of the Council

- Lord Robert Cecil – Lord Privy Seal (Viscount Cecil of Chelwood from 28 December 1923[99])

- William Clive Bridgeman – Home Secretary

- Lord Curzon of Kedleston – Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and Leader of the House of Lords

- The Duke of Devonshire – Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Lord Derby – Secretary of State for War

- Lord Peel – Secretary of State for India

- Sir Samuel Hoare – Secretary of State for Air

- Lord Novar – Secretary for Scotland

- Leo Amery – First Lord of the Admiralty

- Sir Philip Lloyd-Greame – President of the Board of Trade

- Sir Robert Sanders – Minister of Agriculture

- Edward Frederick Lindley Wood – President of the Board of Education

- Sir Anderson Montague-Barlow – Minister of Labour

- نڤيل تشمبرلين – Minister of Health

- Sir William Joynson-Hicks – Financial Secretary to the Treasury

- Sir Laming Worthington-Evans – Postmaster-General

الوزارة الثانية، نوفمبر 1924 - يونيو 1929

- بالدوِن – رئيس الوزراء وزعيم مجلس العموم

- Lord Cave – Lord Chancellor

- Lord Curzon of Kedleston – Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords

- Lord Salisbury – Lord Privy Seal

- Winston Churchill – Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Sir William Joynson-Hicks – Home Secretary

- Sir Austen Chamberlain – Foreign Secretary and Deputy Leader of the House of Commons

- Leo Amery – Colonial Secretary

- Sir Laming Worthington-Evans – Secretary of State for War

- Lord Birkenhead – Secretary of State for India

- Sir Samuel Hoare – Secretary for Air

- Sir John Gilmour – Secretary for Scotland

- William Clive Bridgeman – First Lord of the Admiralty

- Lord Cecil of Chelwood – Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Sir Philip Cunliffe-Lister – President of the Board of Trade

- Edward Frederick Lindley Wood – Minister of Agriculture

- Lord Eustace Percy – President of the Board of Education

- Lord Peel – First Commissioner of Works

- Sir Arthur Steel-Maitland – Minister of Labour

- نڤيل تشمبرلين – Minister of Health

- Sir Douglas Hogg – Attorney-General

الوزارة الثالثة، يونيو 1935- مايو 1937

- ستانلي بالدوِن – رئيس الوزراء وزعيم مجلس العموم

- Lord Hailsham – Lord Chancellor

- Ramsay MacDonald – Lord President of the Council

- Lord Londonderry – Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Lords

- نڤيل تشمبرلين – Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Sir John Simon – Home Secretary and Deputy Leader of the House of Commons

- Sir Samuel Hoare – Foreign Secretary

- Malcolm MacDonald – Colonial Secretary

- J.H. Thomas – Dominions Secretary

- Lord Halifax – Secretary for War

- Lord Zetland – Secretary of State for India

- Lord Swinton – Secretary of State for Air

- Sir Godfrey Collins – Secretary of State for Scotland

- Bolton Eyres-Monsell – First Lord of the Admiralty

- Walter Runciman – President of the Board of Trade

- Walter Elliot – Minister of Agriculture

- Oliver Stanley – President of the Board of Education

- Ernest Brown – Minister of Labour

- Sir Kingsley Wood – Minister of Health

- William Ormsby-Gore – First Commissioner of Works

- Anthony Eden – Minister without Portfolio with responsibility for League of Nations Affairs

- Lord Eustace Percy – Minister without Portfolio with responsibility for government policy

التصوير الثقافي

انظر أيضاً

الهوامش

- ^ Irvine, J. C. (1948). "Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, K. G. 1867–1947". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 6 (17): 2–5. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1948.0015. JSTOR 768907.

- ^ George V died on 20 January 1936 and Edward VIII abdicated on 11 December of the same year, leading to the accession of George VI.

- ^ Philip Williamson, "The Conservative Party 1900 – 1939," in Chris Wrigley, ed., A Companion to Early 20th-Century Britain, (2003) pp 17-18

- ^ "Unthinkable? Historically accurate films". The Guardian. UK. 29 January 2011.

- ^ Maurice Cowling, The Impact of Labour. 1920–1924. The Beginnings of Modern British Politics (Cambridge University Press, 1971), p. 329.

- ^ A. J. P. Taylor, English History, 1914–1945 (Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 206.

- ^ Nick Smart, "Baldwin's Blunder? The General Election of 1923." Twentieth Century British History 7#1 (1996): 110–139.

- ^ Self, Robert (1992). "Conservative reunion and the general election of 1923: a reassessment". Twentieth Century British History. 3 (3): 249–273. doi:10.1093/tcbh/3.3.249.

- ^ Cowling, The Impact of Labour, p. 383.

- ^ أ ب Cowling, The Impact of Labour, p. 410.

- ^ Cowling, The Impact of Labour, p. 411.

- ^ Keith Middlemas and John Barnes, Baldwin: A Biography (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1969), pp. 269–70.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, pp. 271–2.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, pp. 273–4.

- ^ The Hidden Hand, BBC Parliament, 4 December 2007

- ^ Cowling, The Impact of Labour, pp. 408–9.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 275.

- ^ "Bookwatch: The General Strike". Pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ [1]

- ^ أ ب Middlemas and Barnes, pp. 393–4.

- ^ Mastering Modern World History Norman Lowe, 2nd edition (and later eds.), 1966, Macmillan ISBN 978-0-3334-6576-9

- ^ "Search past Fellows". The Royal Society. 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Williamson, Philip (1982). "'Safety First': Baldwin, the Conservative Party and the 1929 General Election" (PDF). Historical Journal. 25 (2): 385–409. doi:10.1017/s0018246x00011614. S2CID 159673425.

- ^ Rubinstein, William D. (2003). Twentieth-Century Britain: A Political History. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-3337-7224-9.

- ^ John Ramsden, The Age of Balfour and Baldwin, 1902–1940 (1978)

- ^ Philip Williamson, "1931 Revisited: The Political Realities." Twentieth Century British History 2#3 (1991): 328–338.

- ^ Baldwin: The Unexpected Prime Minister, by Montgomery Hyde, 1973

- ^ N. C. Fleming, "Diehard Conservatism, Mass Democracy, and Indian Constitutional Reform, c. 1918–35", Parliamentary History 32#2 (2013): 337–360.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 722.

- ^ أ ب Middlemas and Barnes, p. 735.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 736.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, pp. 736–737.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 738.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 739.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 741.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 742.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 743.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, pp. 748–51.

- ^ أ ب Middlemas and Barnes, p. 754.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 756.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, pp. 745–6.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 757.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 759.

- ^ Taylor, p. 378.

- ^ Maurice Cowling, The Impact of Hitler. British Politics and British Policy, 1933–1940 (Chicago University Press, 1977), p. 92.

- ^ أ ب Taylor, p. 383.

- ^ A. Windham Baldwin, My Father: The True Story (1955)

- ^ Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London: Methuen, 1972), p. 412.

- ^ أ ب ت Barnett, p. 413.

- ^ R. A. C. Parker, Churchill and Appeasement (Macmillan, 2000), p. 45.

- ^ Parker, p. 45.

- ^ Martin Gilbert, Churchill. A Life (Pimlico, 2000), pp. 536–7.

- ^ Gilbert, pp. 537–8.

- ^ Barnett, p. 414.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 818.

- ^ Barnett, pp. 414–15.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 970, p. 972.

- ^ Gilbert, p. 567.

- ^ أ ب Middlemas and Barnes, p. 872.

- ^ Lord Citrine, Men and Work. An Autobiography (London: Hutchinson, 1964), p. 355.

- ^ أ ب ت Barnett, p. 422.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 819.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 1030.

- ^ أ ب Middlemas and Barnes, p. 979.

- ^ Philip Williamson, Stanley Baldwin: Conservative Leadership and National Values (Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 326.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 990.

- ^ Norman Lowe, Mastering Modern British History, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan, 1989), p. 488.

- ^ أ ب Middlemas and Barnes, p. 992.

- ^ Williamson, p. 327.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Lowe, p. 488.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةStuart_Ball - ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 1008.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 1003.

- ^ G. I. T. Machin, "Marriage and the Churches in the 1930s: Royal abdication and divorce reform, 1936–7." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 42.1 (1991): 68–81.

- ^ Lynn Prince Picknett and Stephen Clive Prior, War of the Windsors (2002) p. 122.

- ^ أ ب Williamson, p. 328.

- ^ Pearce and Goodland (23 May 1991). British Prime Ministers From Balfour to Brown. Transworld Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-4156-6983-2. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Pearce and Goodland (2 September 2013). British Prime Ministers From Balfour to Brown. Routledge. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-4156-6983-2. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Williamson, p. 327

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 998.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, pp. 1006–7.

- ^ Harold Nicolson, Diaries and Letters. 1930–1939 (London: Collins, 1966), pp. 285–286.

- ^ Nicolson, p. 286.

- ^ Foreign News: Baldwin the Magnificent – TIME, Time Magazine (21 December 1936).

- ^ Charmley, John (2008). A History of Conservative Politics Since 1830. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 129–30. ISBN 978-1-1370-1963-9.[dead link]

- ^ Nicolson, p. 301.

- ^ "No. 34403". The London Gazette. 1 June 1937. p. 3508.

- ^ "No. 34405". The London Gazette. 8 June 1937. p. 3663.

- ^ The Times 9 December 1938

- ^ TIME 26 December 1938

- ^ The Times 29 July 1939

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 1045.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 1046.

- ^ Cato, Guilty Men (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1940), p. 84.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 1047.

- ^ أ ب Middlemas and Barnes, p. 1055.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 1054, p. 1057.

- ^ Middlemas and Barnes, p. 1058 and note 1.

- ^ "No. 32892". The London Gazette. 28 December 1923. p. 9107.

قراءات إضافية

- Ball, Stuart. "Baldwin, Stanley, first Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (1867–1947)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 DOI:10.1093/ref:odnb/30550 a short scholarly biography

- Ball, Stuart. Baldwin & the Conservative Party: The Crisis of 1929-1931 (1988) 266pp

- Bassett, Reginald (1948). "Telling the truth to the people: the myth of the Baldwin 'confession'". Cambridge Journal. II: 84–95.

- Cowling, Maurice. The Impact of Labour. 1920–1924. The Beginnings of Modern British Politics (Cambridge University Press, 1971).

- Cowling, Maurice. The Impact of Hitler. British Politics and British Policy, 1933–1940 (U of Chicago Press, 1977).

- Dunbabin, J. P. D. "British Rearmament in the 1930s: a Chronology and Review." Historical Journal 18#3 (1975): 587-609. Argues Baldwin rearmed enough to save Britain while it stood alone in 1940-41. Delays in rearmament were caused by slow decision-making. not by any political scheme to insure Baldwin's return to office in 1935.

- Hyde, H. Montgomery. Baldwin: The Unexpected Prime Minister (1973); 616pp; Jenkins calls it the best biography

- Jenkins, Roy. Baldwin (1987), Scholarly biography.

- McKercher, B. J. C. Second Baldwin Government & the United States, 1924-1929: Attitudes & Diplomacy (1984), 271pp.

- Malament, Barbara C. 'Baldwin Re-restored?', The Journal of Modern History, (Mar. 1972), 44#1 pp. 87–96. in JSTOR, historiography

- Mowat, C. L. 'Baldwin Restored?', The Journal of Modern History, (June. 1955) 27#2 pp. 169–174. in JSTOR

- Middlemas, Keith, and John Barnes, Baldwin: A Biography (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1969); 1100 pp of details

- Ramsden, John. The age of Balfour and Baldwin, 1902-1940. Vol. 3 Of the history of the Conservative Party (1978).

- Robertson, James C (1974). "The British General Election of 1935". Journal of Contemporary History. 9 (1): 149–164. doi:10.1177/002200947400900109. JSTOR 260273.

- Rowse, A. L. 'Reflections on Lord Baldwin', Political Quarterly, XII (1941), pp. 305–17. Reprinted in Rowse, End of an Epoch (1947).

- Stannage, Tom. Baldwin Thwarts the Opposition: The British General Election of 1935 (1980) 320pp.

- Somervell, D.C. The Reign of King George V, (1936) pp 342 – 409.online free

- Taylor, A. J. P. English History, 1914–1945 (Oxford University Press, 1990).

- Taylor, Andrew J. "Stanley Baldwin, Heresthetics and the Realignment of British Politics," British Journal of Political Science, (July 2005), 35#3 pp 429–463, Baldwin polarized politics with Labour, squeezing out the Liberals

- Williamson, Philip. Stanley Baldwin. Conservative Leadership and National Values (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- Williamson, Philip. "Baldwin's Reputation: Politics and History, 1937–1967," Historical Journal (Mar 2004) 47#1 pp 127–168 in JSTOR

- Williamson, Philip. "'Safety First': Baldwin, the Conservative Party, and the 1929 General Election," Historical Journal, (June 1982) 25#2 pp 385–409 in JSTOR

- Williamson, Philip. Stanley Baldwin: conservative leadership and national values ( Cambridge UP, 1999). Introduction

مراجع أساسية

- Baldwin, Stanley. Service of Our Lives: Last Speeches as Prime Minister (London: National Book Association, Hutchinson & Co., 1937). viii, 167 pp. speeches from between 12 Dec. 1935 to 18 May 1937.

وصلات خارجية

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Stanley Baldwin

- Stanley Baldwin on the Downing Street website.

- Recording of Baldwin's speech at the Empire Rally of Youth (1937) – a British Library sound recording

- قالب:UK National Archives ID

- Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and Anne of Green Gables

- قالب:NPG name

- Works by or about ستانلي بالدوين at Internet Archive

- Works by ستانلي بالدوين at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Articles with dead external links from September 2023

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with empty listen template

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2020

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles to be expanded from March 2022

- All articles to be expanded

- Pages with empty portal template

- ستانلي بالدوِن

- مواليد 1867

- وفيات 1947

- خريجو جامعة كمبردج

- خريجو جامعة بيرمنگهام

- رؤساء وزراء المملكة المتحدة

- زعماءحزب المحافظين (المملكة المتحدة)

- مستشارو خزانة المملكة المتحدة

- اللوردات الرؤساء للمجلس

- اللوردات حملة ختم الخاصة الملكية

- Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1906–10

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1910

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1910–18

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1918–22

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1922–23

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1923–24

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1924–29

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1929–31

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1931–35

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1935–45

- ضباط المدفعية الملكية

- أعضاء مجلس الخاصة الملكية بالمملكة المتحدة

- أعضاء مجلس الخاصة الملكية لكندا

- قيمو جامعة إدنبرة

- قيمو جامعة گلاسگو

- مستشارو جامعة كمبردج

- Chancellors of the University of St Andrews

- أنگليكان إنگليز

- زملاء الجمعية الملكية

- أشخاص تعلموا في مدرسة هارو

- People educated at Hawtreys

- Earls in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

- فرسان الوشاح

- Burials at Worcester Cathedral

- People from Bewdley

- People from Worcestershire

- People from Stourport-on-Severn

- زعماء مجلس العموم

- إنگليز من أصل اسكتلندي

- Edward VIII abdication crisis

- Presidents of the Marylebone Cricket Club

- Conservative Party Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

- British Odd Fellows