جوسف تشمبرلين

| The Right Honourable Joseph Chamberlain | |

|---|---|

| |

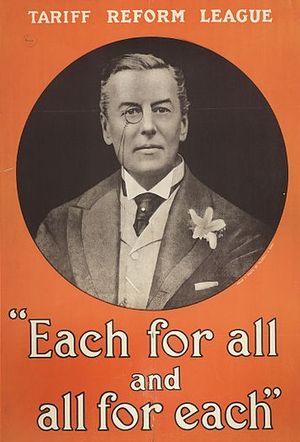

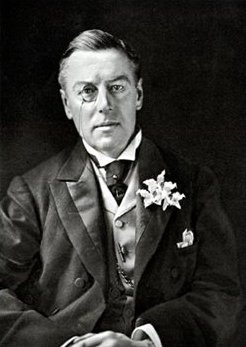

| Joseph Chamberlain in 1909. | |

| Leader of the Opposition in the Commons | |

| في المنصب 8 February 1906 – 27 February 1906 | |

| العاهل | Edward VII |

| رئيس الوزراء | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

| سبقه | Arthur Balfour |

| خلفه | Arthur Balfour |

| Secretary of State for the Colonies | |

| في المنصب 29 June 1895 – 16 September 1903 | |

| رئيس الوزراء | The Marquess of Salisbury Arthur Balfour |

| سبقه | The Marquess of Ripon |

| خلفه | Alfred Lyttelton |

| President of the Local Government Board | |

| في المنصب 1 February 1886 – 3 April 1886 | |

| رئيس الوزراء | William Ewart Gladstone |

| سبقه | Arthur Balfour |

| خلفه | James Stansfeld |

| President of the Board of Trade | |

| في المنصب 3 May 1880 – 9 June 1885 | |

| رئيس الوزراء | William Ewart Gladstone |

| سبقه | Viscount Sandon |

| خلفه | The Duke of Richmond |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | 8 يوليو 1836 Camberwell, لندن, England |

| توفي | 2 يوليو 1914 (aged 77) Birmingham, England |

| المدفن | Key Hill Cemetery, Birmingham |

| الحزب | Liberal (1866–1886) Liberal Unionist (1886–1906) |

| الزوج |

Harriet Kenrick

(m. 1861–1863)Florence Kenrick

(m. 1868–1875)Mary Endicott (m. 1888–1914) |

| الأنجال | Beatrice Austen Neville Ida Hilda Ethel |

| التعليم | University College School |

| المهنة | Businessman |

| الدين | British Unitarian |

| التوقيع | |

| الكنية | "Our Joe" |

جوسف تشـِمبرلين Joseph Chamberlain (8 يوليو 1836 – 2 يوليو 1914) كان سياسياً بريطانياً ورجل دولة، كان في البداية ليبرالي راديكالي، ثم بعد معارضة Home Rule لأيرلندا أصبح اتحادي ليبرالي، واستقر به المقام كأحد رواد الإمبريالية في تحالف مع المحافظين.

Chamberlain made his career in Birmingham, first as a manufacturer of screws and then as a notable Mayor of the city. He was a radical Liberal Party member and an opponent of the Education Act of 1870. As a self-made businessman, he had never attended university and had contempt for the aristocracy. He entered the House of Commons at thirty-nine years of age, relatively late in life compared to politicians from more privileged backgrounds. Rising to power through his influence with the Liberal grassroots organisation, he served as President of the Board of Trade in Gladstone's Second Government (1880–85). At the time, Chamberlain was notable for his attacks on the Conservative leader Lord Salisbury, and in the 1885 general election he proposed the "Unauthorised Programme", which was not enacted, of benefits for newly enfranchised agricultural labourers, including the slogan promising "three acres and a cow." Chamberlain resigned from Gladstone's Third Government in 1886 in opposition to Irish Home Rule. He helped to engineer a Liberal Party split and became a Liberal Unionist, a party which included a bloc of MPs based in and around Birmingham.

From the 1895 general election the Liberal Unionists were in coalition with the Conservative Party, under Chamberlain's former opponent Lord Salisbury. In that government Chamberlain promoted the Workmen's Compensation Act of 1897.[1][2] He served as Secretary of State for the Colonies, promoting a variety of schemes to build up the Empire in Asia, Africa, and the West Indies. He had some responsibility for causing and directing the Second Boer War (1899-1902) and was a dominant figure in the Unionist Government's re-election at the "Khaki Election" in 1900. In 1903, he resigned from the Cabinet to campaign for tariff reform (i.e. taxes included in the prices of imports instead of free trade). He obtained the support of most Unionist MPs for this stance, but the Party's split led to its landslide defeat at the 1906 general election. Some months later, shortly after public celebrations of his seventieth birthday in Birmingham, he was disabled by a stroke, ending his public career.

Despite never becoming Prime Minister, he was one of the most important British politicians of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as well as a renowned orator and divisive politician.[3] Winston Churchill later wrote of him that he was the man "who made the weather". Chamberlain was the father, by different marriages, of Sir Austen Chamberlain and Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain.

النشأة والعمل التجاري والزواج

Chamberlain was born in Camberwell in London to a successful shoe manufacturer also named Joseph (1796–1874), and his wife Caroline Harben, daughter of Henry Harben.[4] His younger brother was Richard Chamberlain, later also a Liberal politician. He was educated at University College School 1850–1852, excelling academically and gaining prizes in French and mathematics.[5]

The elder Chamberlain was not able to provide advanced education for all his children, and at the age of 16 Joseph was apprenticed to the Worshipful Company of Cordwainers and worked for the family business making quality leather shoes. At 18 he joined his uncle's screw-making business, Nettlefolds of Birmingham, in which his father had invested. The company became known as Nettlefold and Chamberlain when Chamberlain became a partner with Joseph Nettlefold. During the business's most prosperous period, it produced two-thirds of all metal screws made in England, and by the time of Chamberlain's retirement from business in 1874 it was exporting worldwide.[6]

Chamberlain married Harriet Kenrick, the daughter of Archibald Kenrick, in July 1861 (they had met the previous year). Their daughter Beatrice Mary Chamberlain (1862–1918) was born in May 1862. Harriet, who had had a premonition that she would die in childbirth, became ill two days after the birth of their son Joseph Austen in October 1863, and died three days later. Chamberlain devoted himself to business, while bringing up Beatrice and Austen with the Kenrick parents-in-law.[7]

In 1868, Chamberlain married for the second time, to Harriet's cousin, Florence Kenrick, daughter of Timothy Kenrick.

Chamberlain and Florence had four children: Arthur Neville in 1869, Ida in 1870, Hilda in 1871 and Ethel in 1873. On 13 February 1875, Florence gave birth to their fifth child, but she and the child died within a day.

In 1888 Chamberlain married for the third time in Washington, D.C. His bride was Mary Crowninshield Endicott, daughter of the US Secretary of War, William Crowninshield Endicott.[8]

العمل السياسي المبكر

دعوات للاصلاح

عمدة برمنگهام

ويقول كاتب سيرته:

- Early in his political career, Chamberlain constructed arguably his greatest and most enduring accomplishment, a model of ‘gas-and-water’ or municipal socialism widely admired in the industrial world. At his ceaseless urging, Birmingham embarked on an improvement scheme to tear down its central slums and replace them with healthy housing and commercial thoroughfares, both to ventilate the town and to attract business. This scheme, however, strained the financial resources of the town and undermined the consensus in favour of reform.[9]

السياسة الوطنية

عضو البرلمان والاتحاد الليبرالي الوطني

رئيس مجلس التجارة

الانشقاق الليبرالي

الوحدوي الليبرالي

After January 1887, a series of Round Table Conferences took place between Chamberlain, Trevelyan, Harcourt, Morley and Lord Herschell, in which the participants sought an agreement about the Liberal Party's Irish policy. Chamberlain hoped that an accord would enable him to claim the future leadership of the party and that he would gain influence over the Conservatives simply from the negotiations occurring. Although a preliminary agreement was made concerning land purchase, Gladstone was unwilling to compromise further, and negotiations ended by March. In August 1887, Lord Salisbury invited Chamberlain to lead the British delegation in a Joint Commission to resolve a fisheries dispute between the United States and Newfoundland.الزيارة إلى الولايات المتحدة جددت حماسته للسياسة، وحسنت موقفه في نظر گلادستون. وفي نوفمبر، التقى تشمبرلين ماري إنديكوت، ابنة الثلاث وعشرين ربيعاً وابنة وليام إنديكوت وزير حربية الأمريكي في عهد الرئيس گروڤر كليڤلاند، في حفل في السفارة البريطانية في الولايات المتحدة. وقبل أن يغادر الولايات المتحدة في مارس 1888، كان تشمبرلين قد تقدم لخطبة ماري، واصفاً إياها بأنها 'واحدة من أذكى وألمع البنات اللائي قابلتهن'. وفي نوفمبر 1888، تزوج تشمبرلين ماري في واشنطن العاصمة، متزيناً بالبنفسج الأبيض ، بدلاً من الأوركيد الذي كان علامة مميزة له. وقد أصبحت ماري داعمة مؤمنة لطموحاته السياسية.[10]

The Salisbury ministry was implementing a number of Radical reforms that pleased Chamberlain. Between 1888 and 1889, democratic County Councils were established in Great Britain. By 1891, measures for the provision of smallholdings had been made, and the extension of free, compulsory education to the entire country. Chamberlain wrote that "I have in the last five years seen more progress made with the practical application of my political programme than in all my previous life. I owe this result entirely to my former opponents, and all the opposition has come from my former friends."[11]

The Liberal Association in Birmingham could no longer be relied upon to provide loyal support, so Chamberlain created the Liberal Unionist Association in 1888, associated with the National Radical Union, having extracted his supporters from the old Liberal organisation.

انتخابات 1892

رجل الدولة

وزير المستعمرات

Having agreed to a set of policies, the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists formed a government on 24 June 1895. Salisbury offered four Cabinet posts to Liberal Unionists. Devonshire became Lord President of the Council, and Salisbury and Balfour offered Chamberlain any Cabinet position except Foreign Secretary or Leader of the House of Commons. To their surprise he declined the Exchequer, unwilling to be constrained by conservative spending plans, and also refused the office of Home Secretary, instead asking for the Colonial Office. Chamberlain had adjusted his political strategy after losing a dispute over a seat at Leamington Spa, agreeing to enter the cabinet in a subordinate role and abandoning his much cherished program of social reform for the sake of political survival. Unexpectedly, he used the Colonial Office to become one of the dominant figures in politics.[12]

Chamberlain used the Colonial Office to gain international recognition amidst European competition for territory and popular imperialism. He wanted to expand the British Empire In Africa, the Americas and Asia, reorder imperial trade and resources, and foster closer relations between Britain and the settler colonies. He envisioned a remodeled empire as a federation of Anglo-Saxon nations; he had the support from Conservative backbenchers.[13] Chamberlain had always been a keen imperialist and an advocate of a stronger empire; in 1887 in Canada, he had declared that "I should think our patriotism was warped and stunted indeed if it did not embrace the Greater Britain beyond the seas". Much had been proposed with regards to an imperial federation, a more coherent system of imperial defence and preferential tariffs, yet by 1895 when Chamberlain arrived at the Colonial Office, little had been achieved.

Chamberlain took formal charge of the Colonial Office on 1 July 1895, shortly before his fifty-ninth birthday, with victory assured in the 1895 general election. With the empire at its zenith, Chamberlain governed over 10 million square miles of territory and 450 million people. Believing that positive government action could bind the empire's peoples closer to the crown, Chamberlain stated confidently that "I believe that the British race is the greatest of the governing races that the world has ever seen... It is not enough to occupy great spaces of the world's surface unless you can make the best of them. It is the duty of a landlord to develop his estate." Accordingly, Chamberlain advocated investment in the tropics of Africa, the West Indies and other underdeveloped possessions, a policy that earned him the nickname "Joseph Africanus" among the press.[14]

He was instrumental in recognising the need to treat the "new" tropical diseases being brought back by travellers and sailors from the colonies. With Chamberlain's support, Patrick Manson founded the world's first medical facility dedicated to tropical medicine in 1899. The London School of Tropical Medicine was located in Albert Dock Seamen's Hospital, which itself had opened in 1890 and would later become known as the Hospital for Tropical Diseases. It continues to treat patients to this day.[15]

غارة جيمسون

Cecil Rhodes, Prime Minister of the Cape Colony and managing director of the British South Africa Company, was eager to extend British dominion to all of South Africa, and encouraged the disenfranchised Uitlanders of the Boer republics to resist Afrikaner domination. Rhodes hoped that the intervention of the Company's private army, assembled in the Pitsani Strip (part of the Bechuanaland Protectorate and bordering the Transvaal, which had been ceded to the British South Africa Company by the Colonial Office, officially for the protection of a railway through the territory, in November 1895), could initiate an Uitlander rebellion and the overthrow of the Transvaal government. Chamberlain informed Salisbury on Boxing Day that a rebellion was expected, but was not sure when the invasion would be launched. The subsequent Jameson Raid resulted in the surrender of the invaders. Chamberlain, at Highbury, received a secret telegram from the Colonial Office on 31 December informing him of the beginning of the Raid. Chamberlain, sympathetic to the ultimate goals but uncomfortable with the timing, remarked that "if this succeeds it will ruin me. I'm going up to London to crush it".[16]

Chamberlain ordered Sir Hercules Robinson, Governor-General of the Cape Colony, to repudiate the actions of Leander Starr Jameson and warned Rhodes that the Company's Charter would be in danger if it was discovered that the Cape Prime Minister was involved in the Raid. The prisoners were returned to London for trial, and the Transvaal government received considerable compensation from the Company. During the trial of Jameson, Rhodes' solicitor, Bourchier Hawksley, refused to produce cablegrams that had passed between Rhodes and his agents in London in November and December 1895. According to Hawksley, these demonstrated that the Colonial Office 'influenced the actions of those in South Africa' who embarked on the Raid, and even that Chamberlain had transferred control of the Pitsani Strip to facilitate an invasion. Nine days before the Raid, Chamberlain had asked his Assistant Under-Secretary to encourage Rhodes to 'Hurry Up' because of the deteriorating Venezuelan situation.[16]

In June 1896, Chamberlain offered his resignation to Salisbury, having shown the Prime Minister one or more of the cablegrams implicating him in the Raid's planning. Salisbury refused to accept the offer, possibly reluctant to lose the government's most popular figure. Salisbury reacted aggressively in support of Chamberlain, endorsing the Colonial Secretary's threat to withdraw the Company's charter if the cablegrams were revealed. Accordingly, Rhodes refused to reveal the cablegrams, and as no evidence was produced, the Select Committee appointed to investigate the Jameson Raid had no choice but to absolve Chamberlain of responsibility.

نزاع حدود ڤنزويلا

In July 1895, American Secretary of State Richard Olney demanded that Britain submit a boundary dispute with Venezuela to impartial arbitration, invoking the Monroe Doctrine. Chamberlain favoured a more belligerent stance, but Salisbury chose to tread tentatively, and even the Prime Minister's cautious reply to the American demand provoked President Grover Cleveland to imply in December 1895 that war might be the result of British non-compliance. The United States' bellicosity was an embarrassment for Chamberlain, considering his marriage to an American and his professed admiration of the USA's system of government. Despite privately calling Cleveland a "coarse-grained man" and a "bully", Chamberlain gradually favoured Salisbury's pragmatic strategy. The Prime Minister calmed fears of war by agreeing to an arbitration treaty in February 1896, in which two American judges, two British judges, and a Russian would decide the issue. Chamberlain visited the USA in the autumn of 1896 to negotiate with Olney. The discussions were cordial, thereby improving Anglo-American relations and resulting in Britain's pro-US neutrality during the Spanish–American War of 1898. In October 1899, the tribunal agreed to an Award-based loosely on the Schomburgk Line.

غرب أفريقيا

Chamberlain believed that West Africa had great economic potential, and shared Salisbury's suspicions of the French, who were Britain's principal rival in the region. Chamberlain sanctioned the conquest of the Ashanti in 1895, with Colonel Sir Francis Scott successfully occupying Kumasi and annexing the territory to the Gold Coast. Using the emergency funds of the colonies of Lagos, Sierra Leone and the Gold Coast, he ordered the construction of a railway for the newly conquered area.[17]

The Colonial Office's bold strategy brought it into conflict with the Royal Niger Company, chaired by Sir George Goldie, which possessed title rights to large stretches of the River Niger. Interested in the area as an economic asset, Goldie had yet to assume governing responsibilities, leaving the territory open to incursion by the French, who sent small garrisons to the area with the intention of controlling it. Though Salisbury wished to subordinate the needs of West Africa to the requirement of establishing British supremacy on the River Nile, Chamberlain believed that every territory was worth competing for. Chamberlain was dismayed to learn in 1897 that the French had expanded from Dahomey to Bussa, a town claimed by Goldie. Further French growth in the region would have isolated Lagos from territory in the hinterland, thereby limiting its economic growth. Chamberlain therefore argued that Britain should "even at the cost of war – to keep an adequate Hinterland for the Gold Coast, Lagos & the Niger Territories."

Influenced by Chamberlain, Salisbury sanctioned Sir Edmund Monson, British Ambassador in Paris, to be more assertive in negotiations. The subsequent concessions made by the French encouraged Chamberlain, who arranged for a military force, commanded by Frederick Lugard, to occupy areas claimed by Britain, thereby undermining French claims in the region. In a risky 'chequerboard' strategy, Lugard's forces occupied territories claimed by the French to counterbalance the establishment of French garrisons in British territory. At times, French and British troops were stationed merely a few yards from each other, increasing the risk of war. Nevertheless, Chamberlain assumed correctly that French officers in the region were ordered to act without fighting the British, and in March 1898, the French proposed to settle the issue – Bussa was returned to Britain, and the French were limited to the town of Bona. Chamberlain had successfully imposed British control over the Niger and the inland territories of Sokoto, later joining them together as Nigeria.[18]

سيراليون

In 1896 Britain extended its rule inland from the coastal colony of Sierra Leone. It imposed a hut tax; the Mende and Temne tribes responded with the Hut Tax War of 1898. Chamberlain appointed Sir David Chalmers as a special commissioner to investigate the violence. Chalmers blamed the tax, but Chamberlain disagreed, saying African slave traders instigated the revolt. Chamberlain used the revolt to promote his aggressive "constructive imperialism" in West Africa.[19]

الصين

The seizure of Kiaochow by Germany in November 1897 and Russia's occupation of Port Arthur signalled a scramble for western control of China that threatened British domination of China's foreign trade and control of her tariffs. Both Salisbury and Chamberlain wanted to maintain China's integrity lest partition reduce the country's value as a market for British goods. Though Salisbury sought a local agreement with Russia to reduce its concern for France in the Mediterranean, Chamberlain sought an agreement with another power, using the dramatic term 'alliance'. His first suggestion was for an understanding with Japan to counterbalance the growing influence of Russia.

Chamberlain saw the seizures by Germany and Russia not as part of military strategy, but as an attempt to encroach on Britain's Chinese market. When the issue was put before the cabinet early in 1898, Salisbury hoped to keep Port Arthur open to trade by co-operating with the Russians in granting a loan to the Chinese government. Arguing that British naval power could not stop Russia, Chamberlain favoured a coordinated policy with the United States and Japan, in which the three powers would demand that any concessions extracted from China by Russia should be shared among the other powers. The Cabinet agreed to the occupation of Weihaiwei as compensation, yet Chamberlain saw this as an empty gesture and regarding the fate of the Chinese Empire to be at stake, sought to strengthen Britain's position when Salisbury was weakened by illness in February 1898. Believing that Britain's difficulties in China were accentuated by its isolation, Chamberlain contemplated an agreement with Germany.

مفاوضات التحالف الأنگلو-ألماني: المحاولة الأولى

On 29 March 1898, Hermann von Eckardstein, who had described Chamberlain as "unquestionably the most energetic and enterprising personality of the Salisbury ministry", arranged a meeting between the Colonial Secretary and the German Ambassador in London, Paul von Hatzfeldt. The conversation was strictly unofficial, being nominally about colonial matters and the subject of China. Chamberlain surprised Hatzfeldt by assuring him that Britain and Germany had common interests, that the rupture over the Jameson Raid and the Kruger Telegram was an abnormality and that a defensive alliance should be formulated between the two countries, with specific regards to China. This was difficult for Hatzfeldt, for the Reichstag was scrutinising Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz's First Navy Bill, which characterised Britain as a threat to Germany. The Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Bernhard von Bülow, did not believe that Britain would be a reliable ally because any future Cabinet could reverse the diplomatic policy of its predecessors, and because Parliament and public opinion often made difficulties about Britain's alliance commitments. Von Bülow preferred the co-operation of Russia in China to that of Britain.

Hatzfeldt was instructed to make an agreement appear likely without ever conceding to Chamberlain. No commitments were made, and on 25 April Hatzfeldt asked for colonial concessions from Chamberlain as a precursor to a better relationship. Chamberlain rejected the proposal, thereby terminating the first talks for an Anglo-German alliance. Though Salisbury was unsurprised by the German attitude, Chamberlain was disappointed, and spoke publicly of Britain's diplomatic predicament at Birmingham on 13 May, saying that "We have had no allies. I am afraid we have had no friends ... We stand alone."

When the South African Republic (Transvaal) formally rejected the notion of British suzerainty as allegedly described by the peace treaty of 1881, Chamberlain and Balfour prompted Salisbury to initiate discussions with Portugal regarding Delagoa Bay. In the event of war Britain wanted Portugal to halt arms shipments to the port bound for the Boer republics. Von Hatzfeldt intervened to insist on German participation in the negotiations, which resulted in 30 August Anglo-German Convention, which agreed to the partition of the Portuguese Empire in event of its bankruptcy, encouraging Chamberlain to hope for a more general Anglo-German agreement.

ساموا ومفاوضات التحالف الأنگلو-ألماني: المحاولة الثانية

An 1888 treaty established an Anglo-US-German tripartite protectorate of Samoa, and when King Malietoa Laupepa died in 1898, a contest over the succession ensued. The German candidate, Mataafa, was strongly opposed by the Americans and the British, and civil war began. Salisbury rejected a German suggestion that they ask the USA to withdraw from Samoa. Meanwhile, Chamberlain, smarting from the dismissal of his alliance proposal with Germany, refused the suggestion that Britain withdraw from Samoa in return for compensation elsewhere, remarking dismissively to Eckardstein "Last year we offered you everything. Now it is too late." Official and public German opinion was incensed by Britain's bullishness, and Chamberlain worked hard to improve Anglo-German relations by facilitating a visit to Britain by Kaiser Wilhelm II. Salisbury's decision to attend to his sick wife allowed Chamberlain to assume control of British policy in July 1899. In November, an agreement was made with the Germans about Samoa in which Britain agreed to withdraw in return for Tonga and the Solomon Islands, and the ending of German claims to British territory in West Africa.

On 21 November 1899, at a banquet in St. George's Hall, Windsor Castle, Chamberlain reiterated his desire for an agreement between Britain and Germany to Wilhelm II. The Kaiser spoke positively about relations with Britain but added that he did not want to exacerbate relations with Russia, and indicated that Salisbury's traditional strategy of reneging on peacetime commitments made any Anglo-German agreement problematic. Chamberlain, rather than Salisbury whose wife had just died, visited von Bülow at Windsor Castle. Chamberlain argued that Britain, Germany and the USA should combine to check France and Russia, yet von Bülow thought British assistance would be of little use in a war with Russia. Von Bülow suggested that Chamberlain should speak positively of Germany in public. Chamberlain inferred from von Bülow's statement that he would do the same in the Reichstag.

The day after the departure of the Kaiser and von Bülow, on 30 November, Chamberlain grandiloquently spoke at Leicester of "a new Triple Alliance between the Teutonic race and the two great trans-Atlantic branches of the Anglo-Saxon race which would become a potent influence on the future of the world." Though the Kaiser was complimentary, Friedrich von Holstein described Chamberlain's speech as a "blunder" and the Times attacked Chamberlain for using the term "alliance" without inhibition. On 11 December, von Bülow spoke in the Reichstag in support of the Second Navy Bill, and made no reference to an agreement with Britain, which he described as a declining nation jealous of Germany. Chamberlain was startled but von Hatzfeldt assured him that von Bülow's motivation was to fend off opponents in the Reichstag. Although Chamberlain was irritated by von Bülow's behaviour, he still hoped for an agreement.

جنوب أفريقيا

Chamberlain and the British government had long wished for the federation of South Africa under the British crown, but it appeared that the growing wealth of the Transvaal would ensure that any future union of Southern African states would be as a Boer dominated republic outside the British Empire. Chamberlain sought British domination of the Transvaal and Orange Free State by endorsing the civil rights of the disenfranchised Uitlanders. Britain also exerted steady military pressure. In April 1897, Chamberlain asked the Cabinet to increase the British garrison in South Africa by three to four thousand men – consequently, the quantity of British forces in the area grew during the next two years.

The government appointed Sir Alfred Milner to the posts of High Commissioner and Governor-General of the Cape in August 1897 to pursue the issue more decisively. Within a year, Milner concluded that war with the Transvaal was inevitable, and he worked with Chamberlain to publicise the cause of the Uitlanders to the British people. A meeting between President Kruger and Milner at Bloemfontein in May 1899 failed to resolve the Uitlander problem – Kruger's concessions were considered inadequate by Milner, and the Boers left the conference convinced that the British were determined to settle the future of South Africa by force. By now, British public opinion was supportive of a war in support of the Uitlanders, allowing Chamberlain to ask successfully for further troop reinforcements. By the beginning of October 1899, nearly 20,000 British troops were based in the Cape and Natal, with thousands more en route. On 12 October, following a Transvaal ultimatum (9 October) demanding that British troops be withdrawn from her frontiers, and that any forces destined for South Africa be turned back, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State declared war.

حرب البوير: الهزيمة المبكرة والفجر الكاذب

The early months of the Second Boer War were disastrous for Britain.[20] Boer commandos besieged the towns of Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley, and ten thousand Cape Afrikaner rebels joined the Boers in fighting the British. In mid-December 1899, during 'Black Week', the British Army suffered reverses at Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso. Chamberlain was critical privately of the British Army's military performance and was often vexed by the attitude of the War Office. When the Boers bombarded Ladysmith with Creusot ninety-four pounder siege guns, Chamberlain asked for the dispatch of comparable artillery to the war, but was exasperated by the Secretary of State for War, Lord Lansdowne's argument that such weapons required platforms that needed a year of preparation, even though the Boers operated their "Long Tom" without elaborate mountings. Chamberlain also made a number of speeches to reassure the public, and worked to strengthen bonds between Britain and the self-governing colonies, gratefully receiving imperial contingents from Canada, Australia and New Zealand. In particular, the contributions of mounted men from the settler colonies helped fill the British Army's shortfall of mounted infantry, vital in fighting the mobile Boers (who were an entirely mounted force of skilled marksmen).<

Chamberlain managed the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act through the House of Commons, hoping that the newly established federation would adopt a positive attitude towards imperial trade and fighting the war. Wishing to reconcile the British and Afrikaner populations of the Cape, Chamberlain was resistant to Milner's desire to suspend the constitution of the colony, an act that would have given Milner autocratic powers. Chamberlain, as the government's foremost defender of the war, was denounced by many prominent anti-war personalities, including David Lloyd George, a former admirer of the Colonial Secretary.

When in January 1900 the government faced a vote of censure in the House of Commons concerning the management of the war, Chamberlain conducted the defence. On 5 February, Chamberlain spoke effectively in the Commons for over an hour while referring to very few notes. He defended the war, espoused the virtues of a South African federation and promoted the empire; speaking with a confidence which earned him a sympathetic hearing. The vote of censure was subsequently defeated by 213 votes. British fortunes changed after January 1900 with the appointment of Lord Roberts to command British forces in South Africa. Bloemfontein was occupied on 13 March, Johannesburg on 31 May and Pretoria on 5 June. When Roberts formally annexed the Transvaal on 3 September, the Salisbury ministry, emboldened by the apparent victory in South Africa, asked for the dissolution of Parliament, with an election set for October.[21]

الأوج

انتخابات الكاكي

With Salisbury ill, Chamberlain dominated the Unionist election campaign in 1900. Salisbury did not speak at all, and Balfour made few public appearances, causing some to refer to the event as 'Joe's Election'. Fostering a cult of personality, Chamberlain began to refer to himself in the third person as 'the Colonial Secretary', and he ensured that the Boer War featured as the campaign's single issue, arguing that a Liberal victory would result in defeat in South Africa.

Controversy ensued over the use of the phrase "Every seat lost to the government is a seat sold to the Boers" as the Unionists waged a personalised campaign against Liberal critics of the war – some posters even portrayed Liberal MPs praising President Kruger and helping him to haul down the Union Jack. Chamberlain was in the forefront of such tactics, declaring in a speech that "we have come practically to the end of the war... there is nothing going on now but a guerrilla business, which is encouraged by these men; I was going to say those traitors, but I will say instead these misguided individuals." Some Liberals also resorted to sharp campaigning practices, with Lloyd George in particular accusing the Chamberlain family of profiteering. References were made to Kynochs, a cordite manufacturing firm run by Chamberlain's brother, Arthur, as well as Hoskins & Co., of which the Civil Lord of the Admiralty, Austen, held some shares. Many Liberals rejected Lloyd George's claims, and Chamberlain dismissed them as unworthy of reply, although the charges troubled him more than he was prepared to make evident in public.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Twenty-six-year-old Winston Churchill, famous for his escape from a Boer prisoner of war camp and his journalism for the Morning Post, successfully stood as a Conservative candidate in Oldham, where Chamberlain spoke on his behalf. Churchill recalled that

I watched my honoured guest with close attention. He loved the roar of the multitude, and with my father could always say "I have never feared the English democracy." The blood mantled in his cheek, and his eye as it caught mine twinkled with pure enjoyment.

Churchill later wrote that 'Mr. Chamberlain was incomparably the most live, sparkling, insurgent, compulsive figure in British affairs ... 'Joe' was the one who made the weather. He was the man the masses knew.' Chamberlain used his popularity and the cause of imperialism in the election to devastating effect, and with the Liberals split over the issue of the war, the Unionists won a huge majority in the House of Commons of 219. The mandate was not as comprehensive as Chamberlain had hoped, but satisfactory enough to allow him to pursue his vision for the empire and to strengthen his position in the Unionist alliance.

مفاوضات التحالف الأنگلو-ألماني: المحاولة الثالثة

Under pressure from Balfour and Queen Victoria, the ailing Salisbury surrendered the seals of the Foreign Office on 23 October though remaining as Prime Minister. Lansdowne was appointed Foreign Secretary, and Chamberlain's importance in the government grew further still. Chamberlain took advantage of Lansdowne's inexperience to take the initiative in British foreign affairs and attempt, yet again, to formulate an agreement with Germany.[22]

On 16 January 1901, Chamberlain and Devonshire made it known to Eckardstein that they still planned to make Britain part of the Triple Alliance. In Berlin, this news was received with some satisfaction, although von Bülow continued to exercise caution, believing that Germany could afford to wait. The Kaiser, who had come to the UK to visit his dying grandmother Queen Victoria (Chamberlain had been the last minister to visit her, a few days before her death), sent a telegram from London to Berlin urging a positive response, yet von Bülow wished to delay negotiations until Britain was more vulnerable, especially from the ongoing war in South Africa. On 18 March, Eckardstein asked Chamberlain to resume alliance negotiations, and although the Colonial Secretary reaffirmed his support, he was unwilling to commit himself, remembering von Bülow's rebuke in 1899. Chamberlain had a lesser role this time, and it was to Lansdowne that Eckardstein gave a proposal by von Bülow. A five-year Anglo-German defensive alliance was presented, to be ratified by Parliament and the Reichstag. When Lansdowne prevaricated, von Hatzfeldt took firmer control of the negotiations, and presented a demanding invitation for Britain to join the Triple Alliance, in which Britain would be committed to the defence of Austria-Hungary. Salisbury decided decisively against entering an alliance as a junior partner.[23]

On 25 October 1901, Chamberlain defended the British Army's tactics in South Africa against European press criticism, arguing that the conduct of British soldiers was much more respectable than that of troops in the Franco-Prussian War, a statement directed at Germany. The German press was outraged, and when von Bülow demanded an apology, Chamberlain was unrepentant. With this public dispute, Chamberlain's hopes of an Anglo-German alliance were finally ended. Denounced by von Bülow and German newspapers, Chamberlain's popularity in Britain soared, with the Times commenting that 'Mr. Chamberlain...is at this moment the most popular and trusted man in England.'

With Chamberlain still seeking to end Britain's isolation and the negotiations with Germany having been terminated, a settlement with France was attractive. Chamberlain had begun negotiations to settle colonial differences with the French Ambassador, Paul Cambon, in March 1901, although neither Lansdowne nor Cambon had moved as quickly as Chamberlain would have liked. In February 1902, at a banquet at Marlborough House held by King Edward VII, Chamberlain and Cambon resumed their negotiations, with Eckardstein reputedly listening to their conversation and only successfully managing to comprehend the words "Morocco" and "Egypt". Chamberlain had contributed to making possible the Anglo-French Entente Cordiale that would occur in 1904.

حرب البوير: النصر

The occupation of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State in 1900 did not subdue the Boers, who waged a guerrilla campaign throughout 1901 until the end of the war in May 1902. Chamberlain was caught between Unionists demanding a more effective military policy and many Liberals denouncing the war. Publicly, Chamberlain insisted upon the separation of civil and military authority, insisting that the conduct of the war be left to the generals.

The revelation of concentration camps increased pressure on Chamberlain and the government to intervene more effectively – and humanely – in the management of the war. Chamberlain originally questioned the wisdom of establishing the camps, but tolerated them in deference to the military. During the autumn of 1901, Chamberlain took more interest in proceedings when the scandal intensified, strengthening civilian governance. Although he refused to criticise the military publicly, he outlined to Milner the importance of making the camps as habitable as possible, asking the Governor-General of the Cape whether he considered medical provisions to be adequate. Chamberlain also stipulated that unhealthy camps should be evacuated, over-ruling the army where necessary.

By 1902, the death rate in the camps had halved, and was soon to decrease below the usual mortality rate in rural South Africa. Despite the concerns of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Michael Hicks Beach, at the increasing costs of the war, Chamberlain maintained his insistence that the Boers be made to surrender unconditionally, and was supported by Salisbury. Though Lord Kitchener, commanding British forces in South Africa, was eager to make peace with the Boers, Milner was content to wait until the Boers sought peace terms themselves. In April 1902, Boer negotiators accepted Chamberlain's insistence upon the loss of independence of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. However, the Boers insisted that Cape Afrikaner rebels be given amnesty and that Britain pay the Boer republics' war debts.

Chamberlain overrode Milner's objections to accept the proposal, arguing that the financial costs of continuing the war justified the expenditure to relieve the debts of the Boer republics. The Treaty of Vereeniging (31 May 1902) ended the Boer War. The conflict had not been as decisive at Chamberlain had hoped, for the British had put nearly 450,000 troops into the field and had spent nearly £200 million. Nevertheless, the end of war and the inclusion of Boer territory as part of the British Empire presented what Chamberlain viewed as an opportunity to remodel Britain's imperial system.

استقالة سالزبري

The end of the Boer War allowed Salisbury, in declining health, to finally retire. The Prime Minister was keen that Balfour, his nephew should succeed him, but realised that Chamberlain's followers felt that the Colonial Secretary had a legitimate claim to the premiership. Chamberlain was the most popular figure in the government, and Leo Maxse, editing the National Review, argued forcefully that Chamberlain should be appointed Prime Minister when Salisbury retired. Chamberlain himself was less concerned, assuring Balfour's Private Secretary in February 1902 that 'I have my own work to do and...I shall be quite willing to serve under Balfour.' On 7 July 1902, Chamberlain suffered a head injury in a traffic accident. Chamberlain had three stitches and was told by doctors to cease work immediately and remain in bed for two weeks.

On 11 July, Salisbury went to Buckingham Palace, without notifying his Cabinet colleagues, and resigned, with the King inviting Balfour to form a new government later that day. Before accepting, Balfour visited Chamberlain, who said he was content to remain Colonial Secretary. Despite Chamberlain's organisational skills and immense popularity, many Conservatives still mistrusted his Radicalism, and Chamberlain was aware of the difficulties that would be presented by being part of a Liberal Unionist minority leading a Conservative majority. Balfour and Chamberlain were both aware that the Unionist government's survival depended on their co-operation.[24]

قانون التعليم البريطاني 1902

Balfour Education Bill was intended to promote National Efficiency, a cause which Chamberlain thought worthy. However, the Education Bill abolished the 2,568 school boards established under W.E. Forster's 1870 Act, bodies that were popular with Nonconformists and Radicals, replacing them with local education authorities that would administer a state centred system of primary, secondary and technical schools. The Bill would also give ratepayer's money to voluntary, Church of England schools. Chamberlain was aware that the Bill's proposals would estrange Nonconformists, Radicals and many Liberal Unionists from the government, but could not oppose it as he owed his position as Colonial Secretary to Conservative support. Chamberlain warned Robert Morant about Nonconformist dissent, asking why voluntary schools could not receive funds from the state rather than the rates. Morant replied that the Boer War had drained the Exchequer of finances.

Chamberlain sought to stem the feared exodus of Nonconformist voters by securing a major concession – local authorities would be given the discretion over the issue of rate aid to voluntary schools, yet even this was renounced before the guillotining of the Bill and its passage through Parliament in December 1902. Thus, Chamberlain had to make the best of a hopeless situation, writing fatalistically that 'I consider the Unionist cause is hopeless at the next election, and we shall certainly lose the majority of the Liberal Unionists once and for all.' Chamberlain already regarded tariff reform as an issue that could revitalise support for Unionism.

جولته في جنوب أفريقيا

Chamberlain visited South Africa between 26 December 1902 and 25 February 1903, seeking to promote Anglo-Afrikaner conciliation and the colonial contribution to the British Empire, and trying to meet people in the newly unified South Africa, including those who had recently been enemies during the Boer War. In Natal, Chamberlain was given a rapturous welcome. In the Transvaal, he met Boer leaders who were attempting unsuccessfully to alter the peace terms reached at Vereeniging. The reception given to Chamberlain in the Orange River Colony was surprisingly friendly, although he was engaged in a two-hour argument with General Hertzog, who accused the British government of violating three terms of the Treaty of Vereeniging.

During his visit, Chamberlain became convinced that the Boer territories required a period of government by the British crown before being granted self-governance within the empire. In the Cape, Chamberlain found that the Afrikaner Bond was more affable regarding his visit than many members of the English speaking Progressive Party, now under the leadership of Jameson, who called Chamberlain 'the callous devil from Birmingham.' Chamberlain successfully persuaded the Prime Minister, John Gordon Sprigg, to hold elections as soon as possible, a positive act considering the hostile nature of the Cape Parliament since 1899. During the tour, Chamberlain and his wife visited 29 towns, and he delivered 64 speeches and received 84 deputations.

الصهيونية و "مقترح أوغندا"

When he first met Theodor Herzl on 23 October 1902, Chamberlain expressed his sympathy to the Zionist cause. He was willing to consider their plan for settlement near el Arish and in the Sinai Peninsula but his support was conditional on the approval of the Cairo authorities. When it became evident that these efforts were coming to naught, Chamberlain, on 24 April 1903, offered Herzl a territory in East Africa. The proposal came to be known as the Uganda Plan (even though the territory in question was in Kenya). The Zionist Organization, after some deliberations, rejected the proposal, as did the British settlers in East Africa. However, the proposal that Chamberlain made was a major break-through for the Zionists—Great Britain had engaged them diplomatically and recognised a need to find a territory appropriate for Jewish autonomy under British suzerainty.[25]

- من ويكيبيديا العبرية

Theodor Herzl wanted to meet with Chamberlain in July 1902 when he was in London to testify before the Royal Commission on Alien Immigration. On 9 July, he promised the Lord Rothschild Herzl that spoke with Chamberlain on the Zionist cause and July 11 made Herzl for a political program. On 22 September , Herzl sent Chamberlain Settlement proposal Jewish autonomous areas under British control.

Herzl first met Chamberlain on 22 October 1902. Herzl described in his diary [1] the face of Chamberlain C"msich frozen ", but after telling a joke ," laughed mask ". Herzl spoke to him about the possibility of Jewish settlement in the El-Arish and the peninsula of Sinai , but Chamberlain said he could talk to him only on Cyprus , because Al Arish and the Sinai are the responsibility of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs . But Chamberlain also pointed Cyprus on local residents not to consent to Jewish settlement on the island.

Chamberlain asked Herzl to point him in the area under British control where no white people yet, which may be talking.

Herzl showed him the location of El-Arish in Atlas maps and city "of Egypt will not go. We were there." Chamberlain coordinated Herzl about Arish meeting with Foreign Minister Lord Lansdowne Road the next day, which led to sending a delegation of the Zionist movement in the region, to examine the feasibility of a Jewish settlement there. Negotiations with the Egyptian authorities, headed by Lord Cromer and Boutros-Ghali held at the beginning of 1903 failed shortly before Chamberlain returned from Africa.

During Chamberlain's trip to Africa, he visited Uganda (area Kenya today), where he saw "land for Dr. Herzl." The third time they met, in London on 23 April 1903, a few days after the pogroms of Kishinev was still trying to convince Herzl Chamberlain to give the Zionist movement and the al Arish in Sinai, that will be a colony under the influence of the British crown but Chamberlain left his refusal. after the meeting, Chamberlain met with Leopold Greenberg , British and Zionist Herzl's envoy, discussed with him again "in the near Uganda" which will be given to "local self-government" a million Jews. after several weeks even offered to make a bid Chamberlain Herzl preliminary self-government in Uganda, for the consideration of the government.

Chamberlain's resignation from the Cabinet in September 1903 affected the prospects for Uganda. Chamberlain kept in contact with the Zionist movement even after the resignation of the government, and met with representatives of the movement, but was unable to help promote the program.

اصلاح التعريفة: انشقاق الوحدويين

اصلاح التعريفة: آخر معارك تشيمبرلين

Chamberlain asserted his authority over the Liberal Unionists soon after Devonshire's departure. The National Union of Conservative and Unionist Associations also declared majority support for tariff reform, which meant an end to free trade.[26] With firm support from provincial Unionism and most of the press, Chamberlain addressed vast crowds and extolled the virtues of Empire and Imperial Preference, campaigning with the slogan "Tariff Reform Means Work for All." On 6 October 1903, Chamberlain began the campaign with a speech at Glasgow. The newly formed Tariff Reform League received vast funding, allowing it to print and distribute large numbers of leaflets and even to play Chamberlain's recorded messages to public meetings by gramophone. Chamberlain himself spoke at Greenock, Newcastle, Liverpool and Leeds within a month of the outset. Chamberlain explained at Greenock how Free Trade threatened British industry, declaring that "sugar is gone; silk has gone; iron is threatened; wool is threatened; cotton will go! How long are you going to stand it? At the present moment these industries...are like sheep in a field."[27]

الانتخابات العامة 1906

With the Unionists divided and out of favour with many of their former supporters, the Liberal Party won the 1906 general election by a landslide, with the Unionists reduced to just 157 seats in the House of Commons. Although Balfour lost his seat in East Manchester, Chamberlain and his followers increased their majorities in the West Midlands. Chamberlain even became acting Leader of the Opposition in the absence of Balfour. With approximately 102 of the remaining Unionist MPs supportive of Chamberlain, it seemed that he might become leader of the Unionists, or at least win a major concession in favour of tariff reform. Chamberlain asked for a Party meeting, and Balfour, now returned to the Commons, agreed on 14 February 1906 in the 'Valentine letters' to concede that

Fiscal Reform is, and must remain, the constructive work of the Unionist Party. That the objects of such reforms are to secure more equal terms of competition for British trade, and closer commercial union within the Colonies.

Although in opposition, it appeared that Chamberlain had successfully associated the Unionists with the cause of tariff reform, and that Balfour would be compelled to accede to Chamberlain's future demands.

الانحدار

On 8 July 1906, Chamberlain celebrated his seventieth birthday and Birmingham was enlivened for a number of days by official luncheons, public addresses, parades, bands and an influx of thousands of congratulatory telegrams. Tens of thousands of people crowded into the city when Chamberlain made a passionate speech on 10 July, promoting the virtues of Radicalism and imperialism. Chamberlain collapsed on 13 July whilst dressing for dinner in the bathroom of his house at Prince's Gardens. Mary found the door locked and called out, receiving the weakened reply "I can't get out." Returning with help, she found him exhausted on the floor, having turned the handle from the inside, and having suffered a stroke that paralysed his right side.

After a month, Chamberlain was able to walk a small number of steps and resolved to overcome his disabilities. Although unaffected mentally, his sight had deteriorated, compelling him to wear spectacles instead of his monocle. His ability to read had diminished, forcing Mary to read him newspapers and letters. He lost the ability to write with his right hand, and his speech altered noticeably, with Chamberlain's colleague, William Hewins, noting that 'His voice has lost all its old ring. ... He speaks very slowly and articulates with evident difficulty.' Chamberlain barely regained his ability to walk.[28]

Though he had lost all hope of recovering his health and returning to active politics, Chamberlain followed his son Austen's career with interest and encouraged the tariff reform movement. He opposed Liberal proposals to remove the House of Lords' veto, and gave his blessing to the Unionists to fight to oppose Home Rule for Ireland. In the two general elections of 1910 he was allowed to return unopposed in his West Birmingham constituency. In January 1914, Chamberlain decided to not seek re-election. On 2 July, he suffered a heart attack and, surrounded by his family, he died in his wife's arms.

Telegrams of condolence arrived from across the world, with the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, Chamberlain's adversary a decade before, leading the tributes in the House of Commons, declaring that:

in that striking personality, vivid, masterful, resolute, tenacious, there were no blurred or nebulous outlines, there were no relaxed fibres, there were no moods of doubt and hesitation, there were no pauses of lethargy or fear.[29]

The family refused an offer of an official burial at Westminster Abbey and a Unitarian ceremony was held in Birmingham. He was laid to rest at Key Hill Cemetery. On 31 March 1916, the Chamberlain Memorial, a bust created by sculptor Mark Tweed, was unveiled at Westminster Abbey. Amongst the dignitaries present were former Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, Mr Bonar Law, Chamberlain's sons, Austen and Neville – then Lord Mayor of Birmingham – and other members of the Chamberlain, Hutton and Martineau families.[30]

ذكراه

Winston Churchill called Chamberlain "a splendid piebald: first black, then white, or, in political terms, first fiery red, then true blue." This is the conventional view of Chamberlain's politics, that he became gradually more conservative, beginning to the left of the Liberal party and ending to the right of the Conservatives. An alternative view is that he was always a radical in home affairs and an imperialist in foreign affairs, and that these stances were not in great conflict with each other – with both he rejected "laissez-faire capitalism". For instance, after leaving the Liberals he remained a proponent of workmen's compensation and old-age pensions.

He is also commemorated by a memorial in Chamberlain Square in central Birmingham, the large cast-iron Chamberlain Clock, erected in his honour in 1903, during his lifetime, which stands in Birmingham's Jewellery Quarter. His Birmingham home, Highbury Hall, is now a civic conference venue and a venue for civil marriages, and is open occasionally to the public. Highbury Hall is situated not far from Winterbourne House and Garden which was commissioned as a family home for Chamberlain's niece Margaret by her husband John Nettlefold. Winterbourne is now owned by the University of Birmingham. The Midland Metro has a tram named after him.

Joseph Chamberlain Sixth Form College in Birmingham is named after him. There is also a pre-kindergarten to grade 12 public school named in his honour in Grassy Lake, Alberta, Canada. The name "Chamberlain School" was chosen by Mr. William Salvage, a British immigrant and prosperous farmer, who donated the land for the construction of the school in 1910.

جامعة برمنگهام

Birmingham University may be considered Chamberlain's most enduring legacy. Chamberlain was the main founder of the University of Birmingham and was its first Chancellor. He was largely responsible for the university gaining its Royal Charter in 1900 and for the development of the Edgbaston campus. Chamberlain proposed the establishment of Birmingham University to complete his vision for the city. Chamberlain sought to provide ‘a great school of universal instruction’, so that ‘the most important work of original research should be continuously carried on under most favourable circumstances.’[31] The 325-foot Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower, more commonly known as 'Old Joe', is named in honour of the university's founder. It is the tallest free-standing clock tower in the world.[32] The papers of Joseph Chamberlain, Austen Chamberlain, Neville Chamberlain and Mary Chamberlain are housed in the University of Birmingham Special Collections.

الثقافة الشعبية

- Chamberlain was the subject of two parody novels based on Alice in Wonderland, Caroline Lewis's Clara in Blunderland (1902) and Lost in Blunderland (1903).[33][34]

- Chamberlain was portrayed by Basil Dignam in the 1972 Richard Attenborough film Young Winston.

- G. K. Chesterton's anarchist society in The Man Who Was Thursday uses "Joseph Chamberlain" as their password.

كتبه

- Joseph Chamberlain (1903). Imperial Union and Tariff Reform. G. Richards.

- Joseph Chamberlain (1885). The Radical Programme. Chapman and Hall.

- Joseph Chamberlain (1902). Mr. Chamberlain's Defence of the British Troops in South Africa against the foreign slanders. John Murray.

الهامش

- ^ John Macnicol (2002). The Politics of Retirement in Britain, 1878-1948. p. 66.

- ^ Lester Markham "The Employers' Liability/Workmen's Compensation Debate of the 1890S Revisited," Historical Journal 44#2 (2001) pp: 471-495.

- ^ Keith Layborn, Fifty Key Figures in Twentieth Century British Politics (2002) p. 75

- ^ "Debretts House of Commons and the Judicial Bench 1886". Archive.org. Retrieved 19 نوفمبر 2010.

- ^ Peter T. Marsh, Joseph Chamberlain: Entrepreneur in Politics (1994) pp 1-10

- ^ Marsh, Joseph Chamberlain (1994) pp 10-28

- ^ Marsh, Joseph Chamberlain (1994) pp 17-19, 90-91

- ^ Marsh, Joseph Chamberlain (1994) pp 289-312

- ^ Peter T. Marsh, "Chamberlain, Joseph (1836–1914)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed 9 Jan 2016

- ^ Marsh, Chamberlain (1994) pp 289-311

- ^ Jules Philip Gehrke (2006). Municipal Anti-socialism and the Growth of the Anti-socialist Critique in Britain, 1873--1914. ProQuest. p. 65.

- ^ Ian Cawood, "Joseph Chamberlain, the Conservative party and the Leamington Spa candidature dispute of 1895," Historical Research (2006) 79# 206, pp 554-577.

- ^ Larry L. Witherell, "Sir Henry Page Croft and Conservative Backbench Campaigns for Empire, 1903-1932," Parliamentary History (2006) 25#3 pp 357-381 online

- ^ Thomas Heyck (2013). A History of the Peoples of the British Isles: From 1688 to 1914. Routledge. p. 372.

- ^ Cook GC, Webb AJ (2001). "The Albert Dock Hospital, London: The Original Site (in 1899) of Tropical Medicine as a New Discipline". Acta Trop. 79 (3): 249–55. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(01)00127-9. PMID 11412810.

- ^ أ ب Andrew Roberts, Salisbury, 1999, p. 636

- ^ Marsh, Chamberlain (1994) pp 413-435

- ^ Crosby (2011). Joseph Chamberlain: A Most Radical Imperialist. pp. 120–22.

- ^ Daniel R. Magaziner, "Removing the Blinders and Adjusting the View: A Case Study from Early Colonial Sierra Leone," History in Africa (2007), Vol. 34, pp 169-188.

- ^ Andrew N. Porter, Origins of the South African War: Joseph Chamberlain & the Diplomacy of Imperialism, 1895-99 (1980)

- ^ Marsh, Joseph Chamberlain (1994) ch 16

- ^ Avner Cohen, "Joseph Chamberlain, Lord Lansdowne and British Foreign Policy 1901-1903: From Collaboration to Confrontation," Australian Journal of Politics & History (1997) 43#2 pp 122-134

- ^ Adam Lajeunesse, "The Anglo-German Alliance Talks and the Failure of Amateur Diplomacy," Past Imperfect (2007) , Vol. 13, pp 84-107

- ^ Marsh, Joseph Chamberlain (1994) pp 529-31

- ^ Marsh, Joseph Chamberlain: Entrepreneur in Politics (1994) pp 543-45

- ^ Sydney Zebel, "Joseph Chamberlain and the Genesis of Tariff Reform," Journal of British Studies (1967) 7#1 pp 131-157.

- ^ Ian McDonald, Politics in Britain 1898–1914: Lords, Ladies, Lib, Free Trade and Ireland – The Postcard Album, 1998, no 27

- ^ Denis Judd, Radical Joe: a life of Joseph Chamberlain (1977) p 267–8

- ^ Joseph Chamberlain, An Honest Biography -. "An Honest Biography - Joseph Chamberlain". By Alexander Macintosh, 1914 - page 358. Hodder and Stoughton, London, New York etc. Retrieved 3 يوليو 2013.

- ^ "Chamberlain Memorial – Fitting Scene in Westminster Abbey – Unveiling of a Bust". The Straits Times. 11 مايو 1916. p. 9. Retrieved 1 مارس 2013.

- ^ http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/university/about/history/vision.aspx

- ^ http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/university/about/history/academic-history/establishment.aspx

- ^ Sigler, Carolyn, ed. 1997: Alternative Alices: Visions and Revisions of Lewis Carroll's "Alice" Books Lexington. Kentucky, University Press of Kentucky, Pp. 340–347

- ^ Dickinson, Evelyn: "Literary Note and Books of the Month", in United Australia, Vol. II, No. 12, 20 June 1902

ببليوگرافيا

- Amdery, Julian and J.L. Garvin, The life of Joseph Chamberlain, (6 vol. Macmillan, 1932–1969); highly detailed with many letters

- Browne, Harry. Joseph Chamberlain: Radical and Imperialist (Longman Higher Education, 1974), 100 pp

- Carwood, Ian, The Liberal Unionist Party: A History (2012) online

- Cohen, Avner. "Joseph Chamberlain, Lord Lansdowne and British Foreign Policy 1901–1903: From Collaboration to Confrontation", Australian Journal of Politics and History 43#2 1997. pp 122+. online

- Crosby, Travis L. Joseph Chamberlain: A Most Radical Imperialist (London: IB Tauris, 2011). Pp. xii+ 271.

- * Fraser, Derek. "Joseph Chamberlain and the Municipal Ideal," History Today (April 1987) 37#4 pp 33–40

- Fraser, Peter. Joseph Chamberlain: Radicalism and empire, 1868–1914 (1966)

- Howell, P.A.. 'Joseph Chamberlain, 1836–1914'. In The Centenary Companion to Australian Federation, edited by Helen Irving, (Cambridge University Press, 1989)

- Halevy, Elie. Imperialism and the rise of labour, 1895-1905 (Vol. 5. 1934)

- Hunt, Tristram. Building Jerusalem: The Rise and Fall of the Victorian City, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson pp 232–265, 2004

- Jay, Richard. Joseph Chamberlain, A Political Study (Oxford University Press, 1981)

- Judd, Denis. Radical Joe: Life of Joseph Chamberlain, H Hamilton, 1977

- Kubicek, Robert V. The administration of imperialism: Joseph Chamberlain at the Colonial Office (Duke University Press, 1969)

- Loades, David, ed. Reader's Guide to British History (2003) 1: 243–44; historiography

- Marsh, Peter T. Joseph Chamberlain: Entrepreneur in Politics, Yale University Press, 1994; full-scale biography

- Marsh, Peter T. "Chamberlain, Joseph (1836–1914), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online ed., Sept 2013 accessed 3 July 2014

- Porter, Andrew N. Origins of the South African War: Joseph Chamberlain & the Diplomacy of Imperialism, 1895-99 (1980)

- Powell, J. Enoch. Joseph Chamberlain, Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1977

- Strauss, William L. Joseph Chamberlain and the Theory of Imperialism (1942) online edition

- Sykes, Alan. Tariff Reform in British Politics: 1903-1913 (Oxford University Press, 1979).

- Zebel, Sydney. "Joseph Chamberlain and the Genesis of Tariff Reform," Journal of British Studies (1967) 7#1 pp 131–157.

المصادر الرئيسية

- Amdery, Julian and J.L. Garvin, The life of Joseph Chamberlain, (6 vol. Macmillan, 1932–1969); highly detailed with many letters

- Mr Chamberlain's Speeches, ed. C. W. Boyd, (2 vol. 1914) online

وصلات خارجية

- Archival material relating to جوسف تشمبرلين listed at the UK National Register of Archives

- Highbury Hall

- پورتريهات Joe Chamberlain في معرض الپورتريه الوطني، لندن

- Political posters including Joseph Chamberlain on the LSE Digital Library

- Brindley, J. M. (1884). The homes of the working classes and the promises of the Right Hon. Joseph Chamberlain (1884) by J. M. Brindley. Westminster: National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations.

| پرلمان المملكة المتحدة | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه John Bright and Philip Henry Muntz and George Dixon |

Member of Parliament for Birmingham 1876–1885 مع: John Bright and Philip Henry Muntz |

Constituency divided |

| دائرة انتخابية جديدة | Member of Parliament for Birmingham West 1885–1914 |

تبعه أوستن تشمبرلين |

| مناصب سياسية | ||

| سبقه Viscount Sandon |

President of the Board of Trade 1880–1885 |

تبعه The Duke of Richmond |

| سبقه Arthur James Balfour |

President of the Local Government Board 1886 |

تبعه James Stansfeld |

| سبقه The Marquess of Ripon |

Secretary of State for the Colonies 1895–1903 |

تبعه Alfred Lyttelton |

| سبقه Arthur Balfour |

Leader of the Opposition in the Commons 1906 |

تبعه Arthur Balfour |

| مناصب حزبية | ||

| سبقه New position |

President of the National Liberal Federation 1877–1880? |

تبعه Henry Fell Pease? |

| مناصب أكاديمية | ||

| سبقه John Eldon Gorst |

قيم جامعة گلاسگو 1896–1899 |

تبعه Earl of Rosebery |

| سبقه New institution |

Chancellor of the University of Birmingham 1900–1914 |

تبعه Lord Robert Cecil |

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Use dmy dates from March 2014

- EngvarB from March 2014

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2011

- مواليد 1836

- وفيات 1914

- الامبراطورية البريطانية

- وزراء دولة بريطانيون

- مستشارو جامعة برمنگهام

- English Unitarians

- تاريخ برمنگهام، غرب ميدلاندز

- أشخاص اقترنوا بجامعة برمنگهام

- Liberal Unionist Party MPs

- عمد برمنگهام، غرب ميدلاندز

- أعضاء مجلس الخاصة الملكية بالمملكة المتحدة

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة عن الدوائر الإنگليزية

- People educated at University College School

- People associated with the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

- أشخاص من كامبروِل

- رؤساء الحزب الليبرالي (المملكة المتحدة)

- قيمو جامعة گلاسگو

- زملاء الجمعية الملكية

- UK MPs 1874–80

- UK MPs 1880–85

- UK MPs 1885–86

- UK MPs 1886–92

- UK MPs 1892–95

- UK MPs 1895–1900

- UK MPs 1900–06

- UK MPs 1906–10

- UK MPs 1910

- UK MPs 1910–18