فريگيا

Kingdom of Phrygia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1200–675 BC | |||||||||||||||

موقع فريگيا - المنطقة التقليدية (بالأصفر) - المملكة المتوسعة (الخط البرتقالي). | |||||||||||||||

| العاصمة | Gordion | ||||||||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | Phrygian | ||||||||||||||

| الدين | Phrygian religion | ||||||||||||||

| الحكومة | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Kings[أ] | |||||||||||||||

| Gordias | |||||||||||||||

| Midas | |||||||||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | Iron Age | ||||||||||||||

| 1200 BC | |||||||||||||||

| 675 BC | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| المواضيع الهندو-أوروپية |

|---|

|

ظهرت في أواخر القرن التاسع ق.م. حضارة جديدة وهي حضارة الفريگيون في آسية الصغرى ، ورثت بقايا الحضارة الحيثية ، وكانت حلقة إتصال بينها وبين ليديا وبلاد اليونان. وكانت الأساطير التي حاول بها الفريجيون أن يفسروا للمؤرخين المتشوفين قيام دولتهم قصة رمزية لقيام الأمم وسقوطها. فهم يقولون أن گورديوس أول ملوكهم كان فلاحاً بسيطاً لم يرث من أبويه إلا ثورين إثنين، وأن إبنه ميداس ثاني أولئك الملوك كان رجلاً متلافاً أضعف الدولة بشراهته وإسرافه اللذين مثلهما الخلف بالأسطورة المأثورة التي تقول إنه طلب إلى الآلهة أن تهبه القدرة على تحويل كل ما يمسه إلى ذهب. وأجابت الآلهة طلبه فكان كل ما يمس جسمه يستحيل ذهباً حتى الطعام الذي تلمسه شفتاه. وأوشك الرجل أن يموت جوعاً ، لكن الآلهة سمحت له أن يطهر نفسه من هذه النقمة بأن يغتسل في نهر بكتولس - وهو النهر الذي ظل بعدئذ يخرج حبوباً من الذهب.

وإتخذ الفريجيون طريقهم من آسيا إلى أوربا وشادوا لهم عاصمة في أنقورة ، وظلوا وقتاً ما ينازعون أشور ومصر السيادة على الشرق الأدنى، وإتخذوا لهم إلهة- أُمَّا ُتدعى ما ، ثم عادوا فسموها سيبيل ، واشتقوا هذا الإسم من الجبال (سيبيلا) التي كانت تعيش فيها، وعبدوها على أنها روح الأرض غير المنزرعة، ورمز جميع قوى الطبيعة المنتجة. وأخذوا عن أهل البلاد الأصليين طريقة خدمة الإلهة بالدعارة المقدسة، ورضوا بأن يضموا إلى أساطيرهم الشعبية القصة التي تقول إن سيبيل أحبت الإله الشاب أرتيس وأرغمته على أن يخصي نفسه تكريماً لها. ومن ثم كان كهنة الأمم العظيمة يضحون لها برجولتهم حين يدخلون في خدمة هياكلها. وقد سحرت هذه الخرافات الوحشية لب اليونان وتغلغلت في أساطيرهم وأدبهم. وأدخل الرومان الإلهة سيبيل رسمياً في دينهم ، وكانت بعض الطقوس الخليعة التي تحدث في حفلات المساخر الرومانية مأخوذة عن الطقوس الوحشية التي كان الفريگيون يتبعونها في إحتفالهم بموت أرتيس الجميل وبعثه.

وإنتهى سلطان الفريجيين في آسيا الصغرى بقيام مملكة ليديا الجديدة التي أسسها الملك جيجيس وإتخذ سرديس عاصمة لها.

الشعب والتاريخ

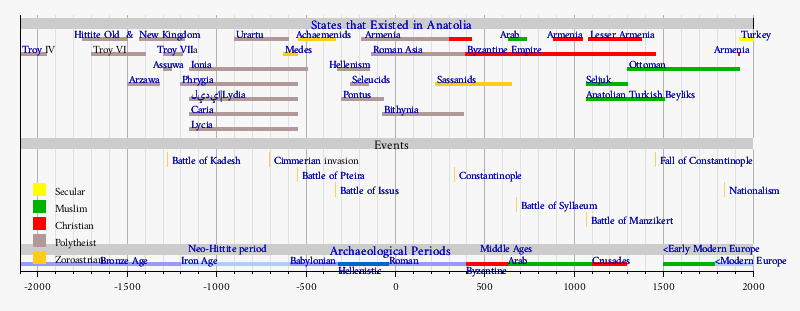

شعب فريجيا من المحتمل أن يكونوا من التراقيين واستوطنوا شمال غرب الأناضول في الألفية الثانية وذهبوا للمرتفعات الوسطى وأنشأوا عاصمتهم في گورديوم وكذلك أنشأوا مركزا دينيا آخر عند مدينة ميداس وهي الآن يازيليكايا. بين القرنين الثاني عشر والتاسع أنشأوا الجزء الغربي من تحالف خامل مع عدد من الشعوب (وعرفهم الآشوريون باسم موشكي وهزمهم الآشوريون في معركة عام 1115 ق.م.) وتبنت هذه الحضارة المثير عن الحيثيين الذين جاؤوا قبلهم وأقاموا سلسلة من الطرق انتفع الفرس منها لاحقا.

في عام 730 ق.م. قام الآشوريون بحل الجزء الشرقي من التحالف وانتقل مركز السلطة إلى فريجيا في حكم ملكهم ميداس التي كانت على حافة الانهيار وفي نهاية القرن مع غزو الكيمريين من القوقاز الذين أحرقوا گورديوم انتقلت السلطة بعد ذلك إلى ليديا. وبعدها بدأت في تراجع حتى وقعت تحت ملوك الأناضول الأقوياء وقيم الفريگيون بعد ذلك كعبيد.

الآثار الثقافية

برع الفريجيون في الأشغال المعدنية والنحت على الخشب ويقال أنهم اخترعوا التطريز وأحجار القبور المنحوتة بروعة والمزارات اكتشفت بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية من قبل المنقبين الأمريكان. ومن ضمن الممارسات الدينية كانت هناك عبادة الإلهة كيبيلى Cybele التي سيطرت وانتشرت حتى اليونان.

اللغة

اللغة القديمة المحكية في شمال غرب أسيا الصغرى وشرق ليديا كانت الفريجية وهناك صنفان للكتابة لزمنين مختلفين، الأول حوالي 730 و 450 ق.م. الذي يستخدم الأبجدية اليونانية القديمة، الثانية أغلبها نقوش قبرية بالأبجدية اليونانية في القرنين الأول والثاني ويقول أغلب الباحثين أنها لغة هندو أوروبية ربما لها قرابة من الأرمنية أو اليونانية.

التاريخ

الأوج ودمار المملكة الفريگية

During the 8th century BC, the Phrygian kingdom with its capital at Gordium in the upper Sakarya River valley expanded into an empire dominating most of central and western Anatolia and encroaching upon the larger Assyrian Empire to its southeast and the kingdom of Urartu to the northeast.[6]

According to the classical historians Strabo,[7] Eusebius and Julius Africanus, the king of Phrygia during this time was another Midas. This historical Midas is believed to be the same person named as Mita in Assyrian texts from the period and identified as king of the Mushki. Scholars figure that Assyrians called Phrygians "Mushki" because the Phrygians and Mushki, an eastern Anatolian people, were at that time campaigning in a joint army.[8] This Midas is thought to have reigned Phrygia at the peak of its power from about 720 BC to about 695 BC (according to Eusebius) or 676 BC (according to Julius Africanus). An Assyrian inscription mentioning "Mita", dated to 709 BC, during the reign of Sargon of Assyria, suggests Phrygia and Assyria had struck a truce by that time. This Midas appears to have had good relations and close trade ties with the Greeks, and reputedly married an Aeolian Greek princess.

A system of writing in the Phrygian language developed and flourished in Gordium during this period, using a Phoenician-derived alphabet similar to the Greek one. A distinctive Phrygian pottery called Polished Ware appears during this period.

However, the Phrygian Kingdom was then overwhelmed by Cimmerian invaders, and Gordium was sacked and destroyed. According to Strabo and others, Midas committed suicide by drinking bulls' blood.

A series of digs have opened Gordium as one of Turkey's most revealing archeological sites. Excavations confirm a violent destruction of Gordium around 675 BC. A tomb from the period, popularly identified as the "Tomb of Midas", revealed a wooden structure deeply buried under a vast tumulus, containing grave goods, a coffin, furniture, and food offerings (Archaeological Museum, Ankara).

As a Lydian province

After their destruction of Gordium, the Cimmerians remained in western Anatolia and warred with Lydia, which eventually expelled them by around 620 BC, and then expanded to incorporate Phrygia, which became the Lydian empire's eastern frontier. The Gordium site reveals a considerable building program during the 6th century BC, under the domination of Lydian kings including the proverbially rich King Croesus. Meanwhile, Phrygia's former eastern subjects fell to Assyria and later to the Medes.

There may be an echo of strife with Lydia and perhaps a veiled reference to royal hostages, in the legend of the twice-unlucky Phrygian prince Adrastus, who accidentally killed his brother and exiled himself to Lydia, where King Croesus welcomed him. Once again, Adrastus accidentally killed Croesus' son and then committed suicide.

As Persian province(s)

Some time in the 540s BC, Phrygia passed to the Achaemenid (Great Persian) Empire when Cyrus the Great conquered Lydia.

After Darius the Great became Persian Emperor in 521 BC, he remade the ancient trade route into the Persian "Royal Road" and instituted administrative reforms that included setting up satrapies. The Phrygian satrapy (province) lay west of the Halys River (now Kızıl River) and east of Mysia and Lydia. Its capital was established at Dascylium, modern Ergili.

In the course of the 5th century, the region was divided in two administrative satrapies: Hellespontine Phrygia and Greater Phrygia.[9]

Under Alexander and his successors

The Macedonian Greek conqueror Alexander the Great passed through Gordium in 333 BC and severed the Gordian Knot in the temple of Sabazios ("Zeus"). According to a legend, possibly promulgated by Alexander's publicists, whoever untied the knot would be master of Asia. With Gordium sited on the Persian Royal Road that led through the heart of Anatolia, the prophecy had some geographical plausibility. With Alexander, Phrygia became part of the wider Hellenistic world. Upon Alexander's death in 323 BC, the Battle of Ipsus took place in 301 BC.[10]

Celts and Attalids

In the chaotic period after Alexander's death, northern Phrygia was overrun by Celts, eventually to become the province of Galatia. The former capital of Gordium was captured and destroyed by the Gauls soon afterwards and disappeared from history.

In 188 BC, the southern remnant of Phrygia came under the control of the Attalids of Pergamon. However, the Phrygian language survived, although now written in the Greek alphabet.

Under Rome and Byzantium

In 133 BC, the remnants of Phrygia passed to Rome. For purposes of provincial administration, the Romans maintained a divided Phrygia, attaching the northeastern part to the province of Galatia and the western portion to the province of Asia. There is some evidence that western Phrygia and Caria were separated from Asia in 254–259 to become the new province of Phrygia and Caria.[11] During the reforms of Diocletian, Phrygia was divided anew into two provinces: "Phrygia I", or Phrygia Salutaris (meaning "healthy" in Latin), and Phrygia II, or Pacatiana (Greek Πακατιανή, Pakatiane, unknown etymology, but translated as "peaceful"), both under the Diocese of Asia. Salutaris with Synnada as its capital comprised the eastern portion of the region and Pacatiana with Laodicea on the Lycus as capital of the western portion. The provinces survived up to the end of the 7th century, when they were replaced by the Theme system. In the Late Roman, early "Byzantine" period, most of Phrygia belonged to the Anatolic theme. It was overrun by the Turks in the aftermath of the Battle of Manzikert (1071).[12] The Turks had taken complete control in the 13th century, but the ancient name of Phrygia remained in use until the last remnant of the Byzantine Empire was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1453.

Culture

Religion

The Phrygian religion in antiquity was polytheistic and was distinct from the earlier religions of the Anatolian peoples and whose pantheon was composed of deities who were reflexes of earlier Aegean-Balkan ones.[13]

Matar Kubeleya

Unlike the Hittite and Luwian religions, the Phrygian pantheon was headed by a feminine deity,[14] a goddess Matar who was associated with mountains and wild animals and was given the epithet of Kubeleya or Kubileya[15] with the full name Matar Kubeleya thus meaning حرفياً 'Mother of the Mountain Peaks'.[16] As the "Mountain Mother" (باليونانية قديمة: Μητηρ ορεια), Matar was the mistress of wild mountainous landscapes and the protectress and nurturer of the wild animals living there.[14]

Matar Kubeleya was the Phrygian reflex of an earlier Aegean-Balkan goddess whose Lydian variant was the goddess Kufaws.[17]

The cult of Matar Kubeleya was performed by priests named Corybantes (meaning حرفياً 'head-shakers'), likely in mountainous locations,[18] and through orgiastic rites featuring pipe and cymbal music and ecstatic dancing,[19] with her name also characterising her as the goddess of head-shaking and the ecstatic state caused by it.[20] Therefore, the goddess was also given a Phrygian epithet meaning "frantic" in reference to the divine frenzy she inspired in her worshipers and recorded in Greek as kubēbos (κυβηβος).[21]

Due to the prominence of the cult of Matar Kubeleya in Central Anatolia during the Iron Age, her cult spread to Pisidia and later to the Greco-Roman world under the name of Kybele (باليونانية قديمة: Κυβέλη; لاتينية: Cybele).[15]

Other deities

The storm god Tiws held an important place in the Phrygian pantheon and his cult was widespread in Phrygia.[15] Tiws was not connected to the earlier Anatolian storm god Tarḫuntas and was instead the Phrygian variant of an earlier Aegean-Balkan god whose Lydian and Greek reflexes were Lefs and Zeus,[22] also cognate with the Italic Jovis.[14]

The Phrygian moon god was Mas who was known in Greek as Men. Mas was the Phrygian reflex of an earlier Aegean-Balkan god whose Lydian variant was Qaλiyañs.[19]

The identity and gender of the Phrygian deity Bas are still unclear.[14]

Artimis was a Potnia Theron-type Phrygian goddess who was the reflex of an older Aegean-Balkan goddess whose Lydian and Greek variants were respectively the goddesses Artimus and Artemis.[14][22]

الموسيقى

The earliest traditions of Greek music derived from Phrygia, transmitted through the Greek colonies in Anatolia and included the Phrygian mode, which was considered to be the warlike mode in ancient Greek music. Phrygian Midas, the king of the "golden touch", was tutored in music by Orpheus himself according to the myth. Another musical invention that came from Phrygia was the aulos, a reed instrument with two pipes.

الطاقية الفريگية

وهي طاقية من اللباد اللين أو الصوف مخروطية تسع الرأس مع تاج صغير في الرأس وكانت غطاء الرأس المعروف في فريجيا، وفي روما القديمة كان يلبسها العبيد الذين تم تحريرهم وفي القرن الثامن عشر أعيد استخدامها في الثورة الفرنسية كرمز للحرية.

الماضي الأسطوري

عرف الكثير من أهل فريجيا بالذات الملوك في الحكايات اليونانية منهم:

- ميداس الملك الذي كان كل ما يلمسه يتحول ذهبا.

- گورديوس باني مدينة گورديوم وواضع العقدة الگوردية.

- تانتالوس الملك الذي حُبس في تارتاروس وابنه بيلوبس ملك البيلوبونيس.

- طروادة وتم تدميرها عندما كانت في العصر الفريجي (رغم أبحاث تقول أن هذا كان في العصر الحيثي).

The name of the earliest known mythical king was Nannacus (aka Annacus).[23] This king resided at Iconium, the most eastern city of the kingdom of Phrygia at that time; and after his death, at the age of 300 years, a great flood overwhelmed the country, as had been foretold by an ancient oracle. The next king mentioned in extant classical sources was called Manis or Masdes. According to Plutarch, because of his splendid exploits, great things were called "manic" in Phrygia.[24] Thereafter, the kingdom of Phrygia seems to have become fragmented among various kings. One of the kings was Tantalus, who ruled over the north western region of Phrygia around Mount Sipylus. Tantalus was endlessly punished in Tartarus, because he allegedly killed his son Pelops and sacrificially offered him to the Olympians, a reference to the suppression of human sacrifice. Tantalus was also falsely accused of stealing from the lotteries he had invented. In the mythic age before the Trojan war, during a time of an interregnum, Gordius (or Gordias), a Phrygian farmer, became king, fulfilling an oracular prophecy. The kingless Phrygians had turned for guidance to the oracle of Sabazios ("Zeus" to the Greeks) at Telmissus, in the part of Phrygia that later became part of Galatia. They had been instructed by the oracle to acclaim as their king the first man who rode up to the god's temple in a cart. That man was Gordias (Gordios, Gordius), a farmer, who dedicated the ox-cart in question, tied to its shaft with the "Gordian Knot". Gordias refounded a capital at Gordium in west central Anatolia, situated on the old trackway through the heart of Anatolia that became Darius's Persian "Royal Road" from Pessinus to Ancyra, and not far from the River Sangarius.

The Phrygians are associated in Greek mythology with the Dactyls, minor gods credited with the invention of iron smelting, who in most versions of the legend lived at Mount Ida in Phrygia.

Gordias's son (adopted in some versions) was Midas. A large body of myths and legends surround this first king Midas.[25] connecting him with a mythological tale concerning Attis.[26] This shadowy figure resided at Pessinus and attempted to marry his daughter to the young Attis in spite of the opposition of his lover Agdestis and his mother, the goddess Cybele. When Agdestis and/or Cybele appear and cast madness upon the members of the wedding feast. Midas is said to have died in the ensuing chaos.

King Midas is said to have associated himself with Silenus and other satyrs and with Dionysus, who granted him a "golden touch".

In one version of his story, Midas travels from Thrace accompanied by a band of his people to Asia Minor to wash away the taint of his unwelcome "golden touch" in the river Pactolus. Leaving the gold in the river's sands, Midas found himself in Phrygia, where he was adopted by the childless king Gordias and taken under the protection of Cybele. Acting as the visible representative of Cybele, and under her authority, it would seem, a Phrygian king could designate his successor.

The Phrygian Sibyl was the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Phrygia.

According to Herodotus,[27] the Egyptian pharaoh Psammetichus II had two children raised in isolation in order to find the original language. The children were reported to have uttered bekos, which is Phrygian for "bread", so Psammetichus admitted that the Phrygians were a nation older than the Egyptians.

In the Iliad, the homeland of the Phrygians was on the Sangarius River, which would remain the centre of Phrygia throughout its history. Phrygia was famous for its wine and had "brave and expert" horsemen.

According to the Iliad, before the Trojan War, a young king Priam of Troy had taken an army to Phrygia to support it in a war against the Amazons. Homer calls the Phrygians "the people of Otreus and godlike Mygdon".[28] According to Euripides, Quintus Smyrnaeus and others, this Mygdon's son, Coroebus, fought and died in the Trojan War; he had sued for the hand of the Trojan princess Cassandra in marriage. The name Otreus could be an eponym for Otroea, a place on Lake Ascania in the vicinity of the later Nicaea, and the name Mygdon is clearly an eponym for the Mygdones, a people said by Strabo to live in northwest Asia Minor, and who appear to have sometimes been considered distinct from the Phrygians.[29] However, Pausanias believed that Mygdon's tomb was located at Stectorium in the southern Phrygian highlands, near modern Sandikli.[30]

According to the Bibliotheca, the Greek hero Heracles slew a king Mygdon of the Bebryces in a battle in northwest Anatolia that if historical would have taken place about a generation before the Trojan War. According to the story, while traveling from Minoa to the Amazons, Heracles stopped in Mysia and supported the Mysians in a battle with the Bebryces.[31] According to some interpretations, Bebryces is an alternate name for Phrygians and this Mygdon is the same person mentioned in the Iliad.

King Priam married the Phrygian princess Hecabe (or Hecuba[32]) and maintained a close alliance with the Phrygians, who repaid him by fighting "ardently" in the Trojan War against the Greeks. Hecabe was a daughter of the Phrygian king Dymas, son of Eioneus, son of Proteus. According to the Iliad, Hecabe's younger brother Asius also fought at Troy (see above); and Quintus Smyrnaeus mentions two grandsons of Dymas that fell at the hands of Neoptolemus at the end of the Trojan War: "Two sons he slew of Meges rich in gold, Scion of Dymas – sons of high renown, cunning to hurl the dart, to drive the steed in war, and deftly cast the lance afar, born at one birth beside Sangarius' banks of Periboea to him, Celtus one, and Eubius the other." Teleutas, father of the maiden Tecmessa, is mentioned as another mythical Phrygian king.

There are indications in the Iliad that the heart of the Phrygian country was further north and downriver than it would be in later history. The Phrygian contingent arrives to aid Troy coming from Lake Ascania in northwest Anatolia, and is led by Phorcys and Ascanius, both sons of Aretaon.

In one of the so-called Homeric Hymns, Phrygia is said to be "rich in fortresses" and ruled by "famous Otreus".[33]

Jews of Phrygia

During the Roman imperial period, Jews in Phrygia, like elsewhere in Asia Minor, formed a prosperous and established minority. Centuries earlier, Seleucid king Antiochus III (ح. 228–187 BC) resettled 2,000 Jewish families from Mesopotamia and Babylon in Lydia and Phrygia, aiming to strengthen Seleucid control in the region. This likely meant relocating more than 10,000 individuals to Antiochus' territories in western Asia Minor. The Jews received land, tax exemptions, and grain until they could sustain themselves from their own harvests. Antiochus specifically allocated land for vineyards, indicating a focus on viticulture, consistent with later references in the Talmud about Jewish Phrygia's wine production.[34]

Evidence suggests the existence of synagogues in various cities, including Iconium, which had an ethnically mixed population but was sometimes considered Phrygian. At Synnada (Şuhut), a ruler of the synagogue is mentioned, indicating the presence of a synagogue. In Hierapolis (Pamukkale), a third-century sarcophagus inscription highlights the importance of the holy synagogue in burial practices. The most well-documented Phrygian synagogue was in Acmonia (Ahat), where in Nero's reign, Ioulia Severa, a descendant of Galatian royalty, funded its construction. While her patronage may not indicate personal sympathy towards Judaism, it suggests support from influential circles. Though conditions for Jews in Acmonia seemed favorable in Severa's time, their continuity is unclear. By the third century, evidence of Jewish presence in Acmonia increased, including gravestones invoking biblical curses against grave violators, indicating the integration of Jewish practices and influential positions within the community.[34]

Christian period

Visitors from Phrygia were reported to have been among the crowds present in Jerusalem on the occasion of Pentecost as recorded in Acts 2:10. In Acts 16:6 the Apostle Paul and his companion Silas travelled through Phrygia and the region of Galatia proclaiming the Christian gospel. Their plans appear to have been to go to Asia but circumstances or guidance, "in ways which we are not told, by inner promptings, or by visions of the night, or by the inspired utterances of those among their converts who had received the gift of prophecy" [35] prevented them from doing so and instead they travelled westwards towards the coast.[36]

The Christian heresy known as Montanism, and still known in Orthodoxy as "the Phrygian heresy", arose in the unidentified village of Ardabau in the 2nd century AD, and was distinguished by ecstatic spirituality and women priests. Originally described as a rural movement, it is now thought to have been of urban origin like other Christian developments. The new Jerusalem its adherents founded in the village of Pepouza has now been identified in a remote valley that later held a monastery.[37]

انظر أيضا

ملاحظات

- ^ balén

المصادر

ديورانت, ول; ديورانت, أرييل. قصة الحضارة. ترجمة بقيادة زكي نجيب محمود.

- Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Rose, C. Brian; Darbyshire, Gareth, eds. (2011). The New Chronology of Iron Age Gordion. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum.

- ^ Liebhart, Richard; Darbyshire, Gareth; Erder, Evin; Marsh, Ben (2016). "A Fresh Look at the Tumuli of Gordion". In Henry, Olivier; Kelp, Ute (eds.). Tumulus as Sema: Space, Politics, Culture and Religion in the First Millennium BC. De Gruyter. pp. 627–636.

- ^ Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 559.

- ^ Ivantchik 1993, p. 57-94.

- ^ Olbrycht 2000a.

- ^ Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0521253697.

- ^ Strabo, I.3.21.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Scott 1995.

- ^ "Kingdoms of the Successors of Alexander: After the Battle of Ipsus, B.C. 301". World Digital Library. 1800–1884. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- ^ van Kuijck, Joey (2016). Shaping the Dioceses of Asiana and Africa in Late Antiquity (PDF). p. 27. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ Swain, Simon; Adams, J. Maxwell; Janse, Mark (2002). Bilingualism in ancient society: language contact and the written word. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. 246–266. ISBN 0-19-924506-1.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 137.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Oreshko 2021, p. 136.

- ^ أ ب ت Oreshko 2021, p. 135.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 146.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 158.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 147.

- ^ أ ب Oreshko 2021, p. 135-136.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 148.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 152-153.

- ^ أ ب Oreshko 2021, p. 138.

- ^ Suidas s. v. Νάννακος; Stephanus of Byzantium s.v. Ἰκόνιον; Both passages are translated in: A new system: or, An analysis of ancient mythology by Jacob Bryant (1807) pp. 12–14

- ^ Plutarch, On Isis and Osiris, Chapter 24

- ^ There were seven all together

- ^ Pausanias Description of Greece 7:17; Arnobius Against the Pagans 5.5

- ^ Histories 2.9

- ^ Homer, Iliad III.216–225.

- ^ Homer, Iliad II.1055–1057; Smith, William (1878). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: J. Murray. p. 230.

- ^ Pausanias 10.27

- ^ Bibliotheca 2.5.10.

- ^ Homer, Iliad XVI.873–875.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHymns5 - ^ أ ب McKechnie, Paul R. (2019). Christianizing Asia Minor: conversion, communities, and social change in the pre-Constantinian era. New York (N.Y.): Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–41. ISBN 978-1-108-48146-5.

- ^ Ellicott's Commentary for English Readers, accessed 18 September 2015

- ^ Acts 16:7–8

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBarbara Levick's

وصلات خارجية

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- صفحات تستخدم خطا زمنيا

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Phrygia

- States and territories established in the 12th century BC

- States and territories disestablished in the 7th century BC

- Historical regions of Anatolia

- Pauline churches

- History of Ankara Province

- History of Afyonkarahisar Province

- History of Eskişehir Province

- ممالك سابقة

- الأناضول

- شعوب قديمة

- شعوب هندو-اوروبية

- فريگيا

- الكنائس الپولسية