كيمريون

نقش نيمرودسكي يصور محاربين كيمريين | |

| التعداد الإجمالي | |

|---|---|

| (غير معروف) | |

| المناطق ذات التواجد المعتبر | |

| شمال البحر الأسود، جنوب اوكرانيا، شمال القوقاز، كوبان | |

| اللغات | |

| اللغة الكيمرية | |

| الديانة | |

| وثنية |

كيمريون أو السّيمِيرِيُّون قبائل بدو رُحَّل كانت تعيش في منطقة تقع الآن في الجزء الجنوبي من أوكرانيا، وذلك في الفترة من 1200 ق.م. حتى 700 ق.م. وكانوا يسكنون منطقة شمال جبال القوقاز من البحر الأسود. استخدموا الخيل والقسي والرماح. وقد عُرفوا بالشدة في الحرب. وهم أوائل قبائل البدو، التي غزت آسيا الصغرى (تركيا الآن) من الجهة الشمالية. لم يجد الباحثون أية مخطوطات مدونة عن الكيمريين، ولا يعرفون عن هذه الجماعة إلا القليل.

ذكر المؤرخ اليوناني هيرودوت، أن قبائل بدو تدعى السكوذيون، طردت الكيميريين من موطنهم إلى آسيا الصغرى نحو 600 ق.م.، حارب الكيميريُّون الآشوريين، وحطموا مملكة فريجيا التي كانت قائمة فيما يعرف الآن بوسط تركيا. بدأوا حملة غزو نحو عام 690 ق.م. على ليديا، وكانت مركزًا تجاريًا كبيرًا، تقع فيما يعرف الآن بغرب تركيا. هزم الآشوريون الكيميريين خلال منتصف القرن السابع قبل الميلاد.

الآثار

The supposed origin of the Cimmerians north of the Caucasus at the end of the Bronze Age loosely corresponds with the early Koban culture (Northern Caucasus, 12th to 4th centuries BC), but there is no compelling reason to associate this culture with the Cimmerians specifically.[1]

There is a tradition in archaeology of applying Cimmerian to the archaeological record associated with the earliest transmission of Iron Age culture along the Danube to Central and Western Europe, associated with the Cernogorovka (9th to 8th centuries) and Novocerkassk (8th to 7th centuries) between the Danube and the Volga. This association is "controversial", or at best conventional, and is not to be taken as a literal claim that specific artifacts are to be associated with the "Cimmerians" of the Greek or Assyrian record.

The use of the name "Cimmerian" in this context is due to Paul Reinecke, who in 1925 postulated a "North-Thracian-Cimmerian cultural sphere" (nordthrakisch-kimmerischer Kulturkreis) overlapping with the younger Hallstatt culture of the Eastern Alps. The term Thraco-Cimmerian (thrako-kimmerisch) was first introduced by I. Nestor in the 1930s. Nestor intended to suggest that there was a historical migration of Cimmerians into Eastern Europe from the area of the former Srubna culture, perhaps triggered by the Scythian expansion, at the beginning of the European Iron Age. In the 1980s and 1990s, more systematic studies by whom? of the artifacts revealed a more gradual development over the period covering the 9th to 7th centuries, so that the term "Thraco-Cimmerian" is now rather used by convention and does not necessarily imply a direct connection with either the Thracians or the Cimmerians.[2]

السجلات الآشورية

Sir Henry Layard's discoveries in the royal archives at Nineveh and Calah included Assyrian primary records of the Cimmerian invasion.[3] These records appear to place the Cimmerian homeland, Gamir, south rather than north of the Black Sea.[4][5][6]

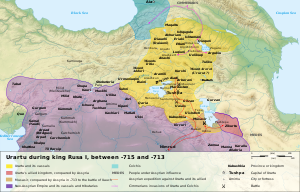

The first record of the Cimmerians appears in Assyrian annals in the year 714 BC. These describe how a people termed the Gimirri helped the forces of Sargon II to defeat the kingdom of Urartu. Their original homeland, called Gamir or Uishdish, seems to have been located within the buffer state of Mannae. The later geographer Ptolemy placed the Cimmerian city of Gomara in this region. The Assyrians recorded the migrations of the Cimmerians, as the former people's king Sargon II was killed in battle against them while driving them from Persia in 705 BC.

The Cimmerians were subsequently recorded as having conquered Phrygia in 696–695 BC, prompting the Phrygian king Midas to take poison rather than face capture. In 679 BC, during the reign of Esarhaddon of Assyria (r. 681–669 BC), they attacked the Assyrian colonies Cilicia and Tabal under their new ruler Teushpa. Esarhaddon defeated them near Hubushna (Hupisna), and they also met defeat at the hands of his successor Ashurbanipal.

ذكراهم

اللغة

| الكيمرية Cimmerian | |

|---|---|

| الحقبة | القرن الثامن ق.م. |

الهندو-اوروپية

| |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

08i | |

| Glottolog | None |

Only a few personal names in the Cimmerian language have survived in Assyrian inscriptions:

- Te-ush-pa-a; according to the Hungarian linguist János Harmatta, it goes back to Old Iranian Tavis-paya "swelling with strength".[7] Mentioned in the annals of Esarhaddon, has been compared to the Hurrian war deity Teshub;[بحاجة لمصدر] others interpret it as Iranian, comparing the Achaemenid name Teispes (Herodotus 7.11.2).

- Dug-dam-mei (Dugdammê) king of the Ummân-Manda (nomads) appears in a prayer of Ashurbanipal to Marduk, on a fragment at the British Museum. According to professor Harmatta, it goes back to Old Iranian Duγda-maya "giving happiness".[7] Other spellings include Dugdammi, and Tugdammê. Edwin M. Yamauchi also interprets the name as Iranian, citing Ossetic Tux-domæg "Ruling with Strength."[8] The name appears corrupted to Lygdamis in Strabo 1.3.21.

- Sandaksatru, son of Dugdamme. This is an Iranian reading of the name, and Manfred Mayrhofer (1981) points out that the name may also be read as Sandakurru. Mayrhofer likewise rejects the interpretation of "with pure regency" as a mixing of Iranian and Indo-Aryan. Ivancik suggests an association with the Anatolian deity Sanda. According to Professor J. Harmatta, it goes back to Old Iranian Sanda-Kuru "Splendid Son".[7] Kur/Kuru is still used as "son" in the Kurdish languages, and in modified form in Persian as korr, for the male offspring of horses.

Some researchers have attempted to trace various place names to Cimmerian origins. It has been suggested that Cimmerium gave rise to the Turkic toponym Qırım (which in turn gave rise to the name "Crimea").[9]

Based on ancient Greek historical sources, a Thracian[10][11] or a Celtic[12] association is sometimes assumed. According to Carl Ferdinand Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt, the language of the Cimmerians could have been a "missing link" between Thracian and Iranian.

الخط الزمني

- 721-715 ق.م. – سرگون الثاني يذكر أرض گامير Gamirr بالقرب من اورارتو.

- 714 – انتحار رصاص الأول من اورارتو، بعد هزيمته من كل من الآشوريين والكيمريين.

- 705 – سرگون الثاني الآشوري يلقى حتفه أثناء حملته على كولومـّو Kulummu.

- 679/678 – گيميرّي Gimirri بزعامة حاكم يدعى تئوشپا Teushpa تغزو آشور من هبوشنا Hubuschna (قپادوقيا؟). آشرحدون الآشوري يهزمهم في المعركة.

- 676-674 – الكيمريون يغزون ويدمرون فريجيا، ويصلون إلى پفلاگونيا Paphlagonia.

- 654 أو 652 – گيگس من ليديا يلقى مصرعه في المعركة ضد الكيمريين. اجتياح سارديس؛ الكيمريون والتررس Treres ينهبون المستعمرات الأيونية.

- 644 – الكيمريون يحتلون سرديس، إلا أنهم ينسحبون بعد ذلك مباشرة

- 637-626 – الكيمريون يلقون هزيمة أمام الياتس الثاني Alyattes II.

- حوالي 515 – آخر سجل تاريخي للكيمريين، في نقش بهيستون للملك داريوش.

الآثار

- حضارة كوبان (شمال القوقاز، القرون 12 - 4 ق.م.)

- حضارة كرنوگوروڤكا (القرون 9 - 8 )

- حضارة نوڤوشركسك (القرون 8 إلى 7، بين الدانوب والڤولگا)

انظر أيضاً

- Gog and Magog

- هندو-سكوذية قديمة كمبوجا,ساكا, ساخا

- كلت

- أمازونيات

- Cimbri

- تراقو-كيمري

- Other Cimmerians: The Cimmerians MILSIM Airsoft Association

- Other Cimmerians: Cimmerian, founder of RantMedia

الهامش

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEB_arch - ^ Ioannis K. Xydopoulos, "The Cimmerians: their origins, movements and their difficulties" in: Gocha R. Tsetskhladze, Alexandru Avram, James Hargrave (eds.), The Danubian Lands between the Black, Aegean and Adriatic Seas (7th Century BC – 10th Century AD), Proceedings of the Fifth International Congress on Black Sea Antiquities (Belgrade – 17–21 September 2013, Archaeopress Archaeology (2015), 119–123. Dorin Sârbu, "Un Fenomen Arheologic Controversat de la Începutul Epocii Fierului dintre Gurile Dunării și Volga: 'Cultura Cimmerianã'" ("A controversial archaeological phenomenon of the early Iron Age between the mouths of the Danube and the Volga: the Cimmerian Culture"), Romanian Journal of Archaeology (2000) (قالب:Ro-icon online version (with bibliography); English abstract)

- ^ K. Deller, "Ausgewählte neuassyrische Briefe betreffend Urarṭu zur Zeit Sargons II.," in P.E. Pecorella and M. Salvini (eds), Tra lo Zagros e l'Urmia. Ricerche storiche ed archeologiche nell'Azerbaigian Iraniano, Incunabula Graeca 78 (Rome 1984) 97–122.

- ^ Cozzoli, Umberto (1968). I Cimmeri. Rome Italy: Arti Grafiche Citta di Castello (Roma).

- ^ Salvini, Mirjo (1984). Tra lo Zagros e l'Urmia: richerche storiche ed archeologiche nell'Azerbaigian iraniano. Rome Italy: Ed. Dell'Ateneo (Roma).

- ^ Kristensen, Anne Katrine Gade (1988). Who were the Cimmerians, and where did they come from?: Sargon II, and the Cimmerians, and Rusa I. Copenhagen Denmark: The Royal Danish Academy of Science and Letters.

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUNESCO - ^ Yamauchi, Edwin M (1982). Foes from the Northern Frontier: Invading Hordes from the Russian Steppes. Grand Rapids MI USA: Baker Book House.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1991). Asimov's Chronology of the World. New York: HarperCollins. p. 50.

- ^ Meljukova, A. I. (1979). Skifija i Frakijskij Mir. Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Strabo ascribes the Treres to the Thracians at one place (13.1.8) and to the Cimmerians at another (14.1.40)

- ^ Posidonius in Strabo 7.2.2.

ببليوجرافيا

- Ivanchik A.I. "Cimmerians and Scythians", 2001

- Terenozhkin A.I., Cimmerians, Kiev, 1983

- Cimmerian. (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 30, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9082650

- Collection of Slavonic and Foreign Language Manuscripts - St.St Cyril and Methodius - Bulgarian National Library: http://www.nationallibrary.bg/slavezryk_en.html

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Articles using Template:Infobox ethnic group with deprecated parameters

- Articles using infobox ethnic group with image parameters

- Languages without Glottolog code

- Languages without ISO 639-3 code but with Linguist List code

- Language articles with unreferenced extinction date

- Languages with neither ISO nor Glottolog code

- Language articles with unsupported infobox fields

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2007

- شعوب إيرانية قديمة

- بدو اوراسيون

- أناضول العصر الحديدي

- آشور

- تاريخ القرم

- شعوب قديمة في روسيا

- قبائل وصفها الرئيسي من هيرودوت