ست (إله)

| ست | |

|---|---|

| |

| God of storms, the desert, and chaos | |

| مركز العبادة الرئيسي | Ombos |

| الرمز | The was scepter |

| الوالدان | Geb and Nut |

| الأشقاء | Osiris, Isis, Nephthys |

| Consort | Nephthys, Tawaret (in some accounts), Anat, Astarte |

| ||||||

| Sutekh بالهيروغليفية |

|---|

ست ( Set ؛ /sɛt/; Egyptological: Sutekh - swtẖ ~ stẖ[أ] or: Seth /sɛθ/) is a god of deserts, storms, disorder, violence, and foreigners in ancient Egyptian religion.[3] In Ancient Greek, the god's name is given as Sēth (Σήθ). Set had a positive role where he accompanies Ra on his barque to repel Apep (Apophis), the serpent of Chaos.[3] Set had a vital role as a reconciled combatant.[3] He was lord of the Red Land (desert), where he was the balance to Horus' role as lord of the Black Land (fertile land).[3] هو أحد الآلهة المصرية القديمة ، هو إله العواصف والعنف. ، ويقال له ست نبتي ، أي ست المنتمى لمدينة نوبت وهو اله الشر في مصر القديمة حيث قتل أخاه أوزيريس ودارت بينه وبين حورس عدة معارك انتهت بانتصار الخير (حورس)وهو عضو في تاسوع هليوبوليس وينطق اسمه (ست و سوتى ، ستش ، سوتخ ).

In the Osiris myth, the most important Egyptian myth, Set is portrayed as the usurper who murdered and mutilated his own brother, Osiris. Osiris's sister-wife, Isis, reassembled his corpse and resurrected her dead brother-husband with the help of the goddess Nephthys. The resurrection lasted long enough to conceive his son and heir, Horus. Horus sought revenge upon Set, and many of the ancient Egyptian myths describe their conflicts.[4]

Family

Set is the son of Geb, the Earth, and Nut, the Sky; his siblings are Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys. He married Nephthys and fathered Anubis and Wepwawet.[5] In some accounts, he had relationships with the foreign goddesses Anat and Astarte.[3] From these relationships is said to be born a crocodile deity called Maga.[6]

Name origin

The meaning of the name Set is unknown, but it is thought to have been originally pronounced *sūtiẖ [ˈsuw.tixʲ] based on spellings of his name in Egyptian hieroglyphs as stẖ and swtẖ.[7] The Late Egyptian spelling stš reflects the palatalization of ẖ while the eventual loss of the final consonant is recorded in spellings like swtj.[8] The Coptic form of the name, ⲥⲏⲧ Sēt, is the basis for the English vocalization.[7][9]

Set animal

or

or

| |||||||||||

بالهيروغليفية |

|---|

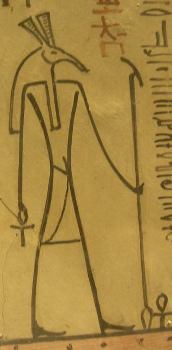

In art, Set is usually depicted as an enigmatic creature referred to by Egyptologists as the Set animal, a beast not identified with any known animal, although it could be seen as resembling an aardvark, an African wild dog, a donkey, a hyena, a jackal, a pig, an antelope, a giraffe, or a fennec fox. The animal has a downward curving snout; long ears with squared-off ends; a thin, forked tail with sprouted fur tufts in an inverted arrow shape; and a slender canine body. Sometimes, Set is depicted as a human with the distinctive head. Some early Egyptologists proposed that it was a stylised representation of the giraffe, owing to the large flat-topped "horns" which correspond to a giraffe's ossicones. The Egyptians themselves, however, used distinct depictions for the giraffe and the Set animal. During the Late Period, Set is usually depicted as a donkey or as a man with the head of a donkey,[10] and in the Book of the Faiyum, Set is depicted with a flamingo head.[11]

The earliest representations of what might be the Set animal comes from a tomb dating to the Amratian culture ("Naqada I") of prehistoric Egypt (3790–3500 BCE), although this identification is uncertain. If these are ruled out, then the earliest Set animal appears on a ceremonial macehead of Scorpion II, a ruler of the Naqada III phase. The head and the forked tail of the Set animal are clearly present on the mace.[12]

التصوير

الرمز الحيواني للمعبود (ست Setekh) كما يظهر على أحجار مقابر الأسرة الأولى فهو يمثل حيوانا يشبه الحمار ، له أرجل طويلة وآذان طويلة أيضا مستعرضة وذيل قصير قائم . كما يبدو أن المصريين الأوائل حوروا ذلك الرمز منذ الدولة القديمة على الأقل إلى شكل حيواني غريب أقرب شبها إلى كلب رابض بعنق مستطيل وآذان مربعة ومقدمة وجه طويلة مقوسة وذيل قائم ، ولم يكن من المستغرب أن فشلت جهود علماء المصريات في تمييز الأصل الحيواني لهذا الكائن . ويظهر على شكل انسان برأس هذا الكائن المميز بفمه الممدود الى الامام واذنيه المستويتين من أعلى.[13]

أسطورة حورس وست

هذه الأسطورة من أهم الأساطير المصرية التي تظهر الصراع بين الخير و الشر و كيف أنتصر الخير في النهاية.[14]

فقد كان كل من الإله أوزيريس و الإلهة إيزيس أخوين وزوجين في وقت واحد، بينما كان كل من ست و نفتيس زوجين آخرين. وكان أوزيريس كان ملكاً عادلاً محباً للخير يحكم مصر من مقره بالوجه البحري. وشعر أخوه "ست" بالغيرة والحسد. وتوجد عدة روايات توضح كيفية تآمر واحتيال ست زعيم الشر ضد أخيه أوزير يس. أقام ست وليمة دعا إليها بعض أصدقائه من الآلهة، ومنهم "أوزوريس"، وأعلن "ست" على المدعوين أنه قد أعد تابوتاً مزيناً بالأحجار الكريمة سيفوز به من يكون على حجم جسمه كهدية، وكان "ست" قد صنع التابوت بحيث يلائم جسم أخيه خذ كل واحد ينام في التابوت لكى يرى إذا كان على مقاس جسمه حتى يفوز به، حتى جاء دور "أوزوريس"، وعندما مد أوزوريس جسمه فيه، سارع ست وأعوانه وأغلقوا عليه التابوت، وألقوا به في النيل، فحمله التيار إلى البحر المتوسط، وهناك حملته الأمواج إلى سواحل "فينيقيا" (لبنان الحالية). " ظلت إيزيس وفية لزوجها،. أخذت تبحث عن زوجها حتى وجدته في جبل (بيبلوس) بسوريا ولكن ست أفلح في سرقة الجثة وقطعها إلى 14 جزأً (وفي بعض الروايات 16 جزأً) ثم قام بتفريقها في أماكن مختلفة في مصر ولكن إيزيس ونفتيس تمكنتا من استعادة الأشلاء ما عدا عضو التذكير (وفي بعض الروايات يقال أنها استعادت كل الأجزاء) واستخدمت إيزيس السحر في تركيب جسد أوزوريس لإعادة الروح له والإنجاب ووضعت منه طفلها حورس. وقامت بتربية ابنها سراً في مستنقعات الدلتا وبين الأحراش. وعاونتها عدة كائنات – فأرضعته بقرة، وقامت برعايته معها سبع عقارب. المهم أن ست رمز الشر لم يعجبه بالطبع عودة أخيه إلى الحياة فقتله من جديد، وقطع جسده إلى أربعين قطعة، ودفن كل جزء منها في إحدى المقاطعات التي كان ينقسم إليها إقليم مصر. وكان الرأس من نصيب مقاطعة "أبيدوس"، وكانت تمثل المقاطعة العاشرة من مقاطعات الصعيد. وحزنت إيزيس حزناً بالغاً لقتل زوجها، ولكنها استطاعت بمساعدة بعض الآلهة أن تجمع أجزاء أوزيريس ، و قامت بلفها بلفافات و استطاعت وأن تعيد إليه الحياة مرة أخرى، ولكن إلى وقت بسيط. و من هنا جاءت فكرة التحنيط و المومياء. و كبر حورس قرر الانتقام لأبيه و لينطلق من هنا صراع طويل بين الولد و العم، صراع رمز لصراع بين الخير و الشر . وبعد صراع مرير، تم العرض على الحكماء وأصحاب القضاء. وأدان القضاء ست ولينتصر الخير على الشر. و ليتحول دور أوزير يس ، وفضل أن ينتقل إلى أسفل الأرض حيث عالم الموتى، وأن يمارس سلطانه على ملكوت الموتى. يقال أن أصل أسطورة أوزوريس عن شخصية حقيقة كان ملكاً في عصر سحيق للغاية على أرض مصر كلها وكانت عاصمته شرق الدلتا "بوزيريس" (أبو صير – بنها الحالية) وقد فسر موته غرقاً على يد الإله "ست" أنه مات في ثورة ضده كان مركزها مدينة "أتبوس" التي أصبحت مقر عبادة الإله ست (طوخ الآن), وبذلك انقسمت مصر إلى مملكتين إحداهما في الدلتا والأخرى في الصعيد ووحدتا نتيجة لحملة ناجحة للشماليين .

العبادة

ولقد كان مهد الإله (ست) هو مدينة (إنبويت Enboyet) (أمبوس Ombos باليونانية) وهي في المقاطعة الخامسة من مصر العليا ، تقع بين الموقعين الحديثين لقريتي (نقادة) و(بلاص) ، ولقد ازدهرت (أمبوس) منذ عصور قبل الأسرات ، يدل على ذلك مقابر هذه العصور المبكرة والممتدة إلى جوار هذه المدينة . ومع قيام الأسرة الأولى انتشرت عقيدة المعبود (ست) خارج حدود المقاطعة الخامسة ، وأصبح (ست) (إله الوجه القبلي) والممثل لهذا الجزء بأسره من البلاد ، وغدا بصلاحيته هذه منافسا خطيرا لعقيدة (حورس Horus) ، وهي منافسة شكلت ملامح هذا الإله فيما بعد ، وكذلك مصيره وهو موضوع سنناقشه لاحقا في الفصل الخاص به .

مدينة "نوبت"هي مركز عبادة الإله "ست" (طوخ، مركز نقادة، محافظة قنا حالياً)

Protector of Ra

Set was depicted standing on the prow of Ra's barge defeating the dark serpent Apep. In some Late Period representations, such as in the Persian Period Temple of Hibis at Khargah, Set was represented in this role with a falcon's head, taking on the guise of Horus. In the Amduat, Set is described as having a key role in overcoming Apep.

Set in the Second Intermediate, Ramesside and later periods

During the Second Intermediate Period (1650–1550 BCE), a group of Near Eastern peoples, known as the Hyksos (literally, "rulers of foreign lands") gained control of Lower Egypt, and ruled the Nile Delta, from Avaris. They chose Set, originally Upper Egypt's chief god, the god of foreigners and the god they found most similar to their own chief god, Hadad, as their patron[بحاجة لمصدر]. Set then became worshiped as the chief god once again. The Hyksos King Apophis is recorded as worshiping Set exclusively, as described in the following passage:[15]

King Apophis chose for his Lord the god Seth. He did not worship any other deity in the whole land except Seth.[ب]

— "The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenre", Papyrus Sallier I, 1.2–3 (British Museum No. 10185)[18]

Jan Assmann argues that because the ancient Egyptians could never conceive of a "lonely" god lacking personality, Seth the desert god, who was worshiped on his own, represented a manifestation of evil.[19]

When Ahmose I overthrew the Hyksos and expelled them, in ح. 1522 BCE, Egyptians' attitudes towards Asiatic foreigners became xenophobic, and royal propaganda discredited the period of Hyksos rule. The Set cult at Avaris flourished, nevertheless, and the Egyptian garrison of Ahmose stationed there became part of the priesthood of Set.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The founder of the Nineteenth Dynasty, Ramesses I came from a military family from Avaris with strong ties to the priesthood of Set. Several of the Ramesside kings were named after the god, most notably Seti I (literally, "man of Set") and Setnakht (literally, "Set is strong"). In addition, one of the garrisons of Ramesses II held Set as its patron deity, and Ramesses II erected the so-called "Year 400 Stela" at Pi-Ramesses, commemorating the 400th anniversary of the Set cult in the Nile delta.[20]

In ancient Egyptian astronomy, Set was commonly associated with the planet Mercury.[21]

Set also became associated with foreign gods during the New Kingdom, particularly in the delta. Set was identified by the Egyptians with the Hittite deity Teshub, who, like Set, was a storm god, and the Canaanite deity Baal, being worshipped together as "Seth-Baal".[22]

Additionally, Set is depicted in part of the Greek Magical Papyri, a body of texts forming a grimoire used in Greco-Roman magic during the fourth century CE.[23]

The demonization of Set

According to Herman te Velde, the demonization of Set took place after Egypt's conquest by several foreign nations in the Third Intermediate and Late Periods. Set, who had traditionally been the god of foreigners, thus also became associated with foreign oppressors, including the Kushite and Persian empires.[24] It was during this time that Set was particularly vilified, and his defeat by Horus widely celebrated.

Set's negative aspects were emphasized during this period. Set was the killer of Osiris, having hacked Osiris' body into pieces and dispersed it so that he could not be resurrected. The Greeks would later associate Set with Typhon and Yahweh, a monstrous and evil force of raging nature (being the three of them depicted as donkey-like creatures, classifying their worshippers as onolatrists).[25]

Set and Typhon also had in common that both were sons of deities representing the Earth (Gaia and Geb) who attacked the principal deities (Osiris for Set, Zeus for Typhon).[بحاجة لمصدر] Nevertheless, throughout this period, in some outlying regions of Egypt, Set was still regarded as the heroic chief deity.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Ancient Egyptologist Dr. Kara Cooney shot an episode called "The Birth of the Devil" in the "Out of Egypt" documentary series.[26] In this documentary, the scientist describes the process of demonization of Set and the positioning of the it as absolute evil on the opposite side, in parallel with the transition to monotheism in different regions from Rome to India, where God began to be perceived as the representative of absolute goodness.

Set temples

Set was worshipped at the temples of Ombos (Nubt near Naqada) and Ombos (Nubt near Kom Ombo), at Oxyrhynchus in Upper Egypt, and also in part of the Fayyum area.

More specifically, Set was worshipped in the relatively large metropolitan (yet provincial) locale of Sepermeru, especially during the Ramesside Period.[27] There, Seth was honored with an important temple called the "House of Seth, Lord of Sepermeru". One of the epithets of this town was "gateway to the desert", which fits well with Set's role as a deity of the frontier regions of ancient Egypt. At Sepermeru, Set's temple enclosure included a small secondary shrine called "The House of Seth, Powerful-Is-His-Mighty-Arm", and Ramesses II himself built (or modified) a second land-owning temple for Nephthys, called "The House of Nephthys of Ramesses-Meriamun".[28]

The two temples of Seth and Nephthys in Sepermeru were under separate administration, each with its own holdings and prophets.[29] Moreover, another moderately sized temple of Seth is noted for the nearby town of Pi-Wayna.[28] The close association of Seth temples with temples of Nephthys in key outskirt-towns of this milieu is also reflected in the likelihood that there existed another "House of Seth" and another "House of Nephthys" in the town of Su, at the entrance to the Fayyum.[30]

Papyrus Bologna preserves a most irritable complaint lodged by one Pra'em-hab, Prophet of the "House of Seth" in the now-lost town of Punodjem ("The Sweet Place"). In the text of Papyrus Bologna, the harried Pra'em-hab laments undue taxation for his own temple (The House of Seth) and goes on to lament that he is also saddled with responsibility for: "The ship, and I am likewise also responsible for the House of Nephthys, along with the remaining heap of district temples".[31]

Nothing is known about the particular theologies of the closely connected Set and Nephthys temples in these districts — for example, the religious tone of temples of Nephthys located in such proximity to those of Seth, especially given the seemingly contrary Osirian loyalties of Seth's consort-goddess. When, by the Twentieth Dynasty, the "demonization" of Seth was ostensibly inaugurated, Seth was either eradicated or increasingly pushed to the outskirts, Nephthys flourished as part of the usual Osirian pantheon throughout Egypt, even obtaining a Late Period status as tutelary goddess of her own Nome (UU Nome VII, "Hwt-Sekhem"/Diospolis Parva) and as the chief goddess of the Mansion of the Sistrum in that district.[32][33][34][35]

Seth's cult persisted even into the latter days of ancient Egyptian religion, in outlying but important places like Kharga, Dakhlah, Deir el-Hagar, Mut, and Kellis. In these places, Seth was considered "Lord of the Oasis / Town" and Nephthys was likewise venerated as "Mistress of the Oasis" at Seth's side, in his temples[36] (esp. the dedication of a Nephthys-cult statue). Meanwhile, Nephthys was also venerated as "Mistress" in the Osirian temples of these districts as part of the specifically Osirian college.[36] It would appear that the ancient Egyptians in these locales had little problem with the paradoxical dualities inherent in venerating Seth and Nephthys, as juxtaposed against Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys.

In modern religion

In popular culture

قالب:In popular culture In the television series Doctor Who, Set (using the name Sutekh) is portrayed as an alien entity bent on destroying all life. He first appears in the 1975 serial Pyramids of Mars, where he schemes to escape an Egyptian pyramid he has been imprisoned in millennia ago by Horus. Sutekh returned after nearly 50 years in the 2024 Series 14 two-part finale "The Legend of Ruby Sunday" / "Empire of Death" as the God of Death in the Pantheon.[37]

In the role-playing game Vampire: The Masquerade, the ancient Egyptian deity Set is depicted as an antediluvian vampire, believed to be one of the oldest undead beings. Revered as the founder of the enigmatic Followers of Set (now known as The Ministry in the game's fifth edition). Imprisoned in torpor, Set remains a focal point for his followers who strive to rouse him from his slumber. He commands powers entwined with manipulation, darkness, and serpentine subtlety, epitomized by his unique Discipline, Serpentis, dedicated to the mastery of serpents.

In the 1992 Nintendo Entertainment System video game Nightshade, the villain's public persona is that of "Sutekh", a criminal underboss who unifies the gangs of the fictitious Metro City. In line with the idea of Sutekh, of Egyptian mythology, the Sutekh in the video game reigns supreme over all of the violence in the city. Of particular note, in Egyptian mythology, Sutekh is also the god of foreigners. In the Nightshade video game, its villain is not of Egyptian descent, but instead a man by the name of Waldo P. Schmeer who is a historian obsessed with Egyptian lore.

Sutekh is an antagonist in some films and other material in the Puppet Master universe. Sutekh is portrayed as the other worldly owner of the secret of life, which animates the eponymous puppets, and stalks anyone who steals it.

Ahead of the release of their 25th studio album, The Silver Cord, Australian band King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard released the album's first three songs.[38] The third of these, titled "Set", describes Set killing Osiris and his subsequent conflict with Horus.

انظر أيضا

| ست بالهيروغليفية | ||||||

|

Notes

- ^ Also transliterated Sheth, Setesh, Sutekh, Seteh, Setekh, or Suty. Sutekh appears, in fact, as a god of Hittites in the treaty declarations between the Hittite kings and Ramses II after the battle of Qadesh. Probably Seteh is the lection (reading) of a god honoured by the Hittites, the "Kheta", afterward assimilated to the local Afro-Asiatic Seth.[1][2]

- ^ Translation from Assmann 2008, p. 48. Goedicke's translation: "And then King Apophis, l.p.h., was appointing for himself Sutekh as Lord. He never worked for any other god which is in this entire country except Sutekh.[16] Goldwasser's translation: "Then, king Apophis l.p.h. adopted for himself Seth as lord, and he refused to serve any god that was in the entire land except Seth."[17]

References

- ^ Sayce, Archibald H. The Hittites: The story of a forgotten empire.

- ^ Budge, E.A. Wallis. A History of Egypt from the End of the Neolithic Period to the Death of Cleopatra VII B.C. 30.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Herman Te Velde (2001). "Seth". Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 3.

- ^ Strudwick, Helen (2006). The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-1-4351-4654-9.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةmythopedia - ^ Rogers, John (2019). "The demon-deity Maga: geographical variation and chronological transformation in ancient Egyptian demonology". Current Research in Egyptology 2019: 183–203.

- ^ أ ب te Velde 1967, pp. 1–7.

- ^ "Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae". aaew2.bbaw.de. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ^ "Coptic Dictionary Online". corpling.uis.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Beinlich, Horst (2013). "Figure 7". The Book of the Faiyum (PDF). University of Heidelberg. pp. 27–77, esp.38–39.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 7–12.

- ^ ياروسلاف تشرني (1996). الديانة المصرية القديمة. دار الشروق للنشر.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ حورس/ست

- ^ Assmann 2008, pp. 48, 151 n. 25, citing: Goedicke 1986, pp. 10–11 and Goldwasser 2006.

- ^ Goedicke 1986, p. 31.

- ^ Goldwasser 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Gardiner 1932, p. 84.

- ^ Assmann 2008, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Nielsen, Nicky. "The Rise of the Ramessides: How a Military Family from the Nile Delta Founded One of Egypt's Most Celebrated Dynasties". American Research Center in Egypt. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Parker, R.A. (1974). "Ancient Egyptian astronomy". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 276 (1257): 51–65. Bibcode:1974RSPTA.276...51P. doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0009. JSTOR 74274. S2CID 120565237.

- ^ Keel, Othmar; Uehlinger, Christoph (1998-01-01). Gods, Goddesses, And Images of God (in الإنجليزية). Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-567-08591-7.

- ^ Set in Roman Magical Papyrus

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 138–140.

- ^ Litwa, M. David (2021). "The Donkey Deity". The Evil Creator: Origins of an Early Christian Idea. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-756643-5. OCLC 1243261365.

We see this tradition recounted by several writers. Around 200 BCE, a man called Mnaseas (an Alexandrian originally from what is now southern Turkey), told a story of an Idumean (southern Palestinian) who entered the Judean temple and tore off the golden head of a pack ass from the inner sanctuary. This head was evidently attached to a body, whether human or donkey. The reader would have understood that the Jews (secretly) worshiped Yahweh as a donkey in the Jerusalem temple, since gold was characteristically used for cult statues of gods. Egyptians knew only one other deity in ass-like form: Seth.

- ^ "Out of Egypt - DocuWiki".

- ^ Sauneron. Priests of Ancient Egypt. p. 181.[استشهاد ناقص]

- ^ أ ب Katary 1989, p. 216.

- ^ Katary 1989, p. 220.

- ^ Gardiner (ed.). Papyrus Wilbour Commentary. Vol. S28. pp. 127–128.[استشهاد ناقص]

- ^ Papyrus Bologna 1094, 5,8–7, 1[استشهاد ناقص]

- ^ Sauneron, Beitrage Bf. 6, 46[استشهاد ناقص]

- ^ Pantalacci, L.; Traunecker, C. (1990). 'Le temple d'El-Qal'a. Relevés des scènes et des textes. I' Sanctuaire central. Sanctuaire nord. Salle des offrandes 1 à 112'. Cairo, Egypt: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale.

- ^

Wilson, P. (1997). A Ptolemaic Lexicon: A lexicographical study of the texts in the Temple of Edfu. OLA 78. Leuven. ISBN 978-90-6831-933-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Collombert, P. (1997). "Hout-sekhem et le septième nome de Haute Égypte II: Les stèles tardives (Pl. I–VII)". Revue d'Égyptologie. 48: 15–70. doi:10.2143/RE.48.0.2003683.

- ^ أ ب Kaper 1997b, pp. 234–237.

- ^ Jeffrey, Morgan (15 June 2024). "Who is Sutekh? The identity of Doctor Who's One Who Waits Explained". Radio Times. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Rettig, James (2023-10-03). "King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard – "Theia / The Silver Cord / Set"". Stereogum.

وصلات خارجية

- Le temple d'Hibis, oasis de Khargha: Hibis Temple representations of Sutekh as Horus

المصادر

- Allen, James P. 2004. "Theology, Theodicy, Philosophy: Egypt." In Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7.

- Bickel, Susanne. 2004. "Myths and Sacred Narratives: Egypt." In Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7.

- Cohn, Norman. 1995. Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come: The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09088-9 (1999 paperback reprint).

- Ions, Veronica. 1982. "Egyptian Mythology." New York: Peter Bedrick Books. ISBN 0-87226-249-9.

- Kaper, Olaf Ernst. 1997. Temples and Gods in Roman Dakhlah: Studies in the Indigenous Cults of an Egyptian Oasis. Doctoral dissertation; Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Faculteit der Letteren.

- Kaper, Olaf Ernst. 1997. "The Statue of Penbast: On the Cult of Seth in the Dakhlah Oasis". In Egyptological Memoirs, Essays on ancient Egypt in Honour of Herman Te Velde, edited by Jacobus van Dijk. Egyptological Memoirs 1. Groningen: Styx Publications. 231-241, ISBN 90-5693-014-1.

- Lesko, Leonard H. 1987. "Seth." In The Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Mircea Eliade, 2nd edition (2005) edited by Lindsay Jones. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0-02-865733-0.

- Osing, Jürgen. 1985. "Seth in Dachla und Charga." Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 41:229-233.

- Quirke, Stephen G. J. 1992. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Dover Publications, inc., ISBN 0-486-27427-6 (1993 reprint).

- Stoyanov, Yuri. 2000. The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08253-3 (paperback).

- te Velde, Herman. 1977. Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion. 2nd ed. Probleme der Ägyptologie 6. Leiden: E. J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-05402-2.

- HACHETTE, GODS OF ANCIENT EGYPT 9, SETH, ISSN 1741-2293 (includes a scientific SETH figurina)

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- Articles with incomplete citations from September 2021

- All articles with incomplete citations

- Articles with incomplete citations from January 2021

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from September 2021

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Set (deity)

- Earth gods

- Egyptian demons

- Egyptian gods

- Liminal gods

- Mercurian deities

- Planetary gods

- Sky and weather gods

- War gods

- Chaos gods

- Evil gods

- Amratian culture

- Donkey deities

- Mythological fratricides

- New religious movement deities

- آلهة مصرية