الثامون المصري

في الأساطير المصرية, the Ogdoad (باليونانية قديمة: ὀγδοάς "the Eightfold"; Ancient Egyptian: ḫmnyw, a plural nisba of ḫmnw "eight") were eight primordial deities worshiped in Hermopolis.

The earliest certain reference to the Ogdoad is from the Eighteenth Dynasty, in a dedicatory inscription by Hatshepsut at the Speos Artemidos.[2]

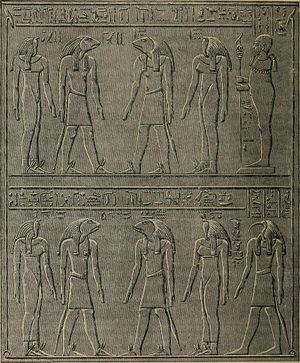

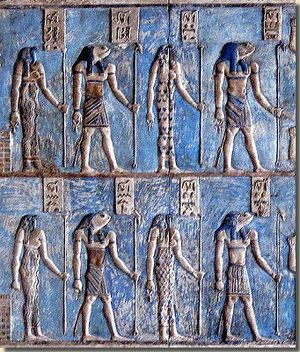

Texts of the Late Period describe them as having the heads of frogs (male) and serpents (female), and they are often depicted in this way in reliefs of the last dynasty, the Ptolemaic Kingdom.[3]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأسماء

The eight deities were arranged in four male–female pairs. The names have the same meanings and differ only by their endings.[4]

Nu

|

Naunet

| |||||||||||||

Ḥeḥu

|

Ḥeḥut

| |||||||||||||

Kekui

|

Kekuit

| |||||||||||||

Qerḥ

|

Qerḥet

|

الصفات

The names of Nu and Naunet are written with the determiners for sky and water, and it seems clear that they represent the primordial waters.

Ḥeḥu and Ḥeḥut have no readily identifiable determiners; according to a suggestion due to Brugsch (1885), the names are associated with a term for an undefined or unlimited number, ḥeḥ, suggesting a concept similar to the Greek aion. From the context of a number of passages in which Ḥeḥu is mentioned, however, Brugsch also suggested that the names may be a personification of the atmosphere between heaven and earth (c.f. Shu).

The names of Kekui and Kekuit are written with a determiner combining the sky hieroglyph with a staff or scepter used for words related to darkness and obscurity, and kkw as a regular word means "darkness", suggesting that these gods represent primordial darkness, comparable to the Greek Erebus, but in some aspects they appear to represent day as well as night, or the change from night to day and from day to night.

The fourth pair has no consistent attributes as it appears with varying names; sometimes the name Qerḥ is replaced by Ni, Nenu, Nu, or Amun, and the name Qerḥet by Ennit, Nenuit, Nunu, Nit, or Amunet. The common meaning of qerḥ is "night", but the determinative (D41 for "to halt, stop, deny") also suggests the principle of inactivity or repose.[5]

There is no obvious way to allot or attribute four functions to the four pairs of deities; Budge postulates that "the ancient Egyptians themselves had no very clear idea" regarding such functions.[6] Nevertheless, there have been attempts to assign "four ontological concepts"[7] to the four pairs: For example, in the context of the New Kingdom, Karenga (2004) uses "fluidity" (for "flood, waters"), "darkness", "unboundedness", and "invisibility" (or "repose, inactivity").[8]

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

|

جزء من سلسلة مقالات عن |

|

|

المعتقدات الرئيسية

وثنية • وحدة الوجود • تعدد الآلهة |

| الشعائر |

| صيغة التقديم • الجنائز • المعابد |

| الآلهة |

| أمون • أمونت • أنوبيس • أنوكت أپپ • أپيس • آتن • أتوم باستت • بات • بس أبناء حورس الأربعة گب • هاپي • حتحور • حقت حورس • إيزيس • خپري • خنوم خونسو • كوك • معحص • ماعت معفدت • منحيت • مرت سگر مسخنت • مونتو • مين • مر-ور موت • نون • نيت • نخبت نفتيس • نوت • اوزيريس • پاخت پتاح • رع • رع-حوراختي • رشپ ساتيس • سخمت • سكر • سركت سوبك • سوپدو • ست • سشات • شو تاورت • تفنوت • تحوت واجت • واج-ور • وپواوت • وسرت |

| النـصـوص |

| عمدوعت • كتاب التنفس كتاب المغارات • كتاب الموتى كتاب الأرض • كتاب الأبواب كتاب العالم السفلي |

| غيرهم |

| الآتونية • لعنة الفراعنة |

- ^ "Drawn by Faucher-Gudin from a photograph by Béato. C.f. Lepsius, Denkm, iv.pl.66 c.", published in Maspero (1897). The scene is collapsed from "the two extremities of a great scene at Philae, in which the Eight, divided into two groups of four, take part in the adoration of the king."

- ^ Zivie-Koch, Christiane (2016). "L'Ogdoad d'Hermopolis à Thebes et ailleurs ou l'invention d'un mythe". Egitto e Vicino Oriente. 39: 57–90.

- ^ Smith, Mark (2002), On the Primaeval Ocean, p. 38

- ^ Budge 1904, p. 283.

- ^ Budge 1904, pp. 283–286.

- ^ Budge 1904, pp. 287–288.

- ^ Harco Willems (1996) - The Coffin of Heqata: (Cairo JdE 36418) : a Case Study of Egyptian Funerary Culture of the Early Middle Kingdom - p.470f Peeters Publishers, 1996.

- ^ Maulana Karenga (2004) - Maat, the Moral Ideal in Ancient Egypt: A Study in Classical African Ethics - p.177 Psychology Press, 2004 ISBN 0415947537 - Volume 70 of Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta.

ببليوجرافيا

- Baines, John D.; Shafer, Byron Esely; Silverman, David P.; Lesko, Leonard H. (1991), Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths, and Personal Practice, Cornell University Press

- Budge, E.A. (1904), The Gods of the Egyptians: Or, Studies in Egyptian Mythology, 1, https://archive.org/stream/godsofegyptianso00budg

- Dunand, Françoise; Zivie-Coche, Christiane (2004), Gods and Men in Egypt: 3.000 BCE to 395 CE, Cornell University Press

- Hart, George (2005), The Routledge Dictionary Of Egyptian Gods And Goddesses, Routledge, p. 113

- Zivie-Koch, Christiane (2016), "L’Ogdoad d’Hermopolis à Thebes et ailleurs ou l’invention d’un mythe", Egitto e Vicino Oriente 39: 57-90

- Salmon, George (1887), "Ogdoad", in Smith, William; Wace, Henry, A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines, IV, London: John Murray, https://books.google.com/books?id=e3DYAAAAMAAJ

وصلات خارجية

- Butler, Edward P. (19 March 2009). "Hermopolitan Ogdoad". Retrieved 2010-08-21.