دنيپرو

دنيپرو

Дніпро | |||

|---|---|---|---|

مدينة | |||

| Dnipro | |||

| الترجمة اللفظية بالـ الأوكرانية | |||

| • الرومنة | Dnipro | ||

| |||

موقع دنيپرو في أوبلاست دنيپروپتروڤسك | |||

| الإحداثيات: 48°28′03″N 35°02′24″E / 48.46750°N 35.04000°E | |||

| البلد | |||

| الأوبلاست | دنيپروپتروڤسك | ||

| الرايون | دنيپرو | ||

| هرومادا | هارومادا دنيپرو الحضري | ||

| التأسيس | 1776 (249 سنة) (رسمياً[1]) | ||

| وضع المدينة | 1778 | ||

| المقر الإداري | بلدية مدينة دنيپرو، 75 أكادميك يوڤارنيتسكي پروسپكت | ||

| الأحياء | |||

| الحكومة | |||

| • النوع | مجلس المدينة، إقليمية | ||

| • العمدة | بوريس فيلاتوڤ[2] (المقترح[2]) | ||

| المساحة | |||

| • مدينة | 409٫718 كم² (158٫193 ميل²) | ||

| • العمران | 5٬606 كم² (2٬164 ميل²) | ||

| المنسوب | 155 m (509 ft) | ||

| التعداد (2022)[3] | |||

| • مدينة | 968٫502 | ||

| • الترتيب | الرابعة في أوكرانيا | ||

| • الكثافة | 2٫411/km2 (6٫24/sq mi) | ||

| • العمرانية | |||

| صفة المواطن | دنيپرو، دنيپريانكي، دنيپروياني | ||

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+2 (ت.ش.أ.) | ||

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (ت.ش.أ.ص.) | ||

| الرمز البريدي | 49000—49489 | ||

| مفتاح الهاتف | +380 56(2) | ||

| الموقع الإلكتروني | dniprorada.gov.ua | ||

| |||

دنيپرو (أوكرانية: Дніпро، Dnipro)[أ]، هي رابع أكبر مدن أوكرانيا، ويسكنها قرابة مليون نسمة.[4][5][6][7] تقع دنيپرو شرق أوكرانيا، على بعد 391 كم[8] جنوب شرق العاصمة كييڤ، وتطل على نهر الدنيپر، والذي اشتقت منه المدينة اسمها. دنيپرو هي المركز الإداري لأوبلاست دنيپروپتروڤسك.[9] يبلغ عدد سكان دنيپرو 968.502 بحسب تقديرات 2022.

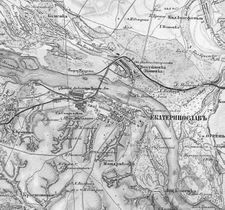

تشير الأدلة الأثرية إلى أن موقع المدينة الحالية كان مأهولًا بالجاليات القوزاقية منذ عام 1524 على الأقل. تأسست يكاترينوسلاڤ ("مجد كاترينا")[10] بمرسوم صادر عن الامبراطورة الروسية يكاترينا العظيمة عام 1787 كمركز إداري لنوڤوروسيا. منذ نهاية القرن التاسع عشر، اجتذبت المدينة رأس المال الأجنبي والقوى العاملة الدولية متعددة الأعراق التي استغلت خام الحديد في كريڤباس وفحم دونباس.

عام 1926 أُعيد تسميتها إلى دنيپروپتروڤسكعلى اسم زعيم الحزب الشيوعي الأوكراني گريگوري پتروڤسكي، حيث أصبحت المدينة مركزاً لالتزام الستالينيين بالتطور السريع للصناعات الثقيلة. في أعقاب الحرب العالمية الثانية، شمل ذلك الصناعات النووية، الأسلحة، والصناعات الفضائية، حيث أدت أهميتها الاستراتيجية إلى تصنيف دنيپروپتروڤسك كمدينة مغلقة.

في أعقاب أحداث يوروميدان عام 2014، تحولت المدينة سياسياً بعيداً عن الأحزاب والشخصيات الموالية لروسيا نحو أولئك الذين يفضلون علاقات أوثق مع الاتحاد الأوروپي. ونتيجة لاجتثاث الشيوعية، أُعيد تسمية المدينة عام 2016 باسم دنيپرو. وفي أعقاب الغزو الروسي لأوكرانيا في فبراير 2022، سرعان ما تطورت دنيپرو كمركز لوجستي للمساعدات الإنسانية ونقطة استقبال للأشخاص الفارين من جبهات القتال المختلفة.[11][12]

التسمية

الاسم الحالي

- أوكرانية: Дніпро [dn⁽ʲ⁾iˈprɔ] [[:Media:uk-Дніпро.ogg|]]

- روسية: Днепр, romanized: Dnepr [dnʲepr]

الأسماء السابقة

- نوڤي كوداك 1645–1784

- يكاترينوسلاڤ (تُنطق أيضاً إكتارينوسلاڤ؛ روسية: Екатеринослав; النطق الروسي: [jɪkətʲɪrʲɪnɐˈsɫaf]) أو كاترينوسلاڤ (أوكرانية: Катеринослав [kɐtɛrɪnoˈslɑu̯]) 1784–1796

- نوڤوروسيك (روسية: Новороссийск; النطق الروسي: [nəvərɐˈsʲijsk]، بالأوكرانية: أوكرانية: Новоросійськ, romanized: Novorosiisk [noʋoroˈs⁽ʲ⁾ijsʲk])، تغير اسمها لفترة وجيزة في عهد نجل كاترينا الثانية المكروه، القيصر بولس الأول؛ ومع ذلك، استعد القيصر ألكسندر الأول الاسم السابق بعد اغتيال والده[13][14]

- يكاترينوسلاڤ 1802–1918، تُسمى كاترينوسلاڤ على بعض خرائط القرن التاسع عشر.[15]

- سيچسلاڤ (أوكرانية: Січеслав [s⁽ʲ⁾it͡ʃeˈslɑu̯]) 1918–1921 (اسم غير رسمي)[16]

- يكاترينوسلاڤ/كاترينوسلاڤ 1918–1926

- دنيپروپتروڤسك (أوكرانية: Дніпропетровськ [ˌdn⁽ʲ⁾ipropeˈtrɔu̯sʲk]، أيضاً دنيپروپتروڤسكى (أوكرانية: Дніпропетровське) بحسب إملاء خاركوڤ 1926–2016.[17] الكلمة مشتقة من الأوكرانية Дніпропетровськ، من Дніпро (دنيپرو "نهر الدنيپر") + Петровський (Petrovsʹkyj)، على اسم الثوري السوڤيتي گريگوري پتروڤسكي / دنيپروپتروڤسك (روسية: Днепропетровск; النطق الروسي: [dʲnʲɪprəpʲɪˈtrofsk]))

التاريخ

التاريخ المبكر

يعود أول ظهور لبشر بالمنطقة إلى أكثر من 150.000 عام. بعد انتهاء العصر الجليدى منذ 10000 عام تقريبا ظهر السكان بالمنطقة من جديد وقاموا ببناء حضارة زراعية في الاغلب ما بين عامى 3500 إلى 2700 قبل الميلاد ويطلق على تلك الحضارة الحضارة التربيلية. قدمت على المنطقة بعد ذلك عدة قبائل كان اكثرها من الشمال والشرق والتي صارعت الحضارة التربيلية طويلا وبعدها لم تستقر المنطقة الا حتى عام 200 قبل الميلاد وعرفت القبائل التي سيطرت على المنطقة بالسرماتيين. بعد ذلك بقرنين تقربيا وبعد ميلاد المسيح بدات القبائل السلاڤية هجرتها للمنطقة ونجحت في السيطرة عليها لفترة ليست بالقصيرة إلى ان استولت الامبراطورية البيزنطية على المنطقة ككل في أوائل القرن الرابع وظل الحكم البيزنطى مستمرا إلى عام 1240 حينما غزا التتار المنطقة وبعد ذلك وفي القرن الخامس عشر ظهرت دولة جديدة عرفت بدولة القوزاق واستطاعت السيطرة على المنطقة.

في القرن السادس عشر قامت بولندا بغزو المنطقة وقامت بإنشاء حصن عسكري في موقع المدينة عام 1635 وعرف بحصن كوداك وتمكنت القوات البولندية والروسية في الحد من النشاط العسكري لدولة القوزاق عن طريق هذا الحصن. وفي أغسطس 1635 استطاع جيوش القوزاق السيطرة على الحصن وهدمه ولكن بولندا اعادت بناءه عام 1638 وأعادت السيطرة على المنطقة وفي عام 1648 نجحت القوزاق من اعادة احتلال الحصن والسيطرة على المنطقة وفي عام 1711 وطبقا لاتفاقية سلام عقدت ما بين روسيا وتركيا تم هدم الحصن بعد طرد القوزاق منه. وفي عام 1768 بدات محاولات لاعادة استيطان المنطقة وانشئت عدد من القرى بجانب موقع المدينة الحالى.

المدينة الإمبراطورية

![]() جمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية 1917–1918

جمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية 1917–1918

∟ جزء ذاتي من الجمهورية الروسية

![]() الدولة الأوكرانية 1918

الدولة الأوكرانية 1918

![]() جمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية 1918–1920

جمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية 1918–1920

![]()

![]() قالب:Country data Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic 1920–1941

قالب:Country data Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic 1920–1941

∟ جزء من الاتحاد السوڤيتي منذ 1922

![]() Reichskommissariat Ukraine 1941–1944

Reichskommissariat Ukraine 1941–1944

∟ جزء من German-occupied Europe

![]() قالب:Country data Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic 1944–1991

قالب:Country data Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic 1944–1991

∟ جزء من الاتحاد السوڤيتي

تأسيس مدينة كاترينا

في عام 1774 قاتل الروس إلى جانب القوزاق ضد تركيا خلال الحروب الروسية التركية 1768 إلى 1747 والتي انتهت بعقد معاهدة انتهت بخضوع المنطقة لروسيا. وفي مايو 1775 قام الروس بتدمير حصن زابوريج سيش والذي تدميره تعد نهاية لدولة القوزاق وبعدها تم إنشاء المدينة إلى الشمال من موقعها الحالى ولكن بسبب سوء هذا الموقع ووعورة أراضيه تم نقل المدينة وسكانها الذين بلغ تعدادهم في هذا الوقت 2194 إلى موقعها الحالى وتم تهجير سكان مدينة زابوريجني سيش إلى المدينة الجديدة التي اطلق عليها اسم ياكاترينوسلاف وانشئت بها عدة قصور وكاتدرائيات وحدائق عامة.

النمو كمركز صناعي

نمت المدينة بسرعة وأصبحت ثالث مدن الامبراطورية الروسية التي يتم امدادها بالكهرباء وافتتحت بها مدرسة للتعدين في 1898 ووصلت بخطوط القطارات عام 1900 واشتهرت بالفحم والحديد والذين انتجا فيها وصنعا على نطاق واسع. وفي عام 1905 ونتيجة لهزيمة الروس ضد اليابان قامت بروسيا عدة ثورات مناهضة للقيصر وكان بعضها بالمدينة وتصدى الجيش لها مما أدى لجرح وقتل المئات.

بعد الثورة البلشفية عام 1917 ظهرت الحكومة الأوكرانية وأصبحت اوكرانيا دولة مستقلة بقيادة تسنترنلا رادا ولكن في يوليو 1918 قامت القوات النمساوية المعادبة لاوكرانيا باحتلال المدينة إلى ان نجح الجيش الاحمر في الوصول إلى المدينة عام 1919 وضمها إلى الاتحاد السوفيتي.

تحت الحكم السوفيتي ظلت المدينة حتى 12 أكتوبر عام 1942 حيث احتلتها قوات ألمانيا النازية. وقبل الاحتلال كانت مركزا هاما لليهود في الاتحاد السوفيتى وكان بها ما يزيد عن 80000 يهودي. بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية عادت للمدينة اهمتها الاقتصادية والسياسية ونشئت بها مؤسسة يازيهماش لصناعة الصواريخ البلاستية وأصبحت مركزا هاما للصناعات المتعلقة بالفضاء في الاتحاد السوفيتي.

عام 1991 أصبحت المدينة جزءا من اوكرانيا بعد استقلالها عن الاتحاد السوفيتى.

الجالية اليهودية وپوگروم 1905

منذ عام 1792، كانت يكاترينوسلاڤ ضمن تخوم الاستيطان، الأراضي الپولندية-اللتوانية السابقة التي لم تفرض فيها كاترينا وخلفاؤها أي قيود على حركة وإقامة رعاياهم اليهود.[20] في غضون أقل من قرن، شكلت الجالية اليهودية الناطق معظمها باليديشية، والتي يبلغ تعدادها 40.000 نسمة، أكثر من ثلث سكان المدينة، وساهمت بحصة كبيرة من رأس مالها التجاري وقوتها العاملة الصناعية.[21]

لم تكن هذه القوة الظاهرة كافية لحماية الجالية من العنف الطائفي.[22]، الذي كان أعضاؤها يتحملون مهمة غير محببة تتمثل في جمع الضرائب الحكومية وتجنيد الشباب للجيش[23] عام 1883، أدت ثلاثة أيام من أعمال الشغب إلى تدمير الأعمال التجارية اليهودية، وأقنعت العديد منهم بمغادرة المدينة مؤقتاً. وفي عام 1904، عادت التحريضات المعادية للسامية بين عامة المسيحيين، لكن الهجمات على الجالية، في ذلك الوقت، تم قمعها بأمر من حاكم ليبرالي.[23]

في ظل الاضطرابات الاجتماعية الواسعة النطاق التي أعقبت هزيمة عام 1905 في الحرب الروسية اليابانية، كانت الحياة السياسية للمدينة تهيمن عليها المعارضة الثورية (بما في ذلك حزب العمال الاشتراكي اليهودي والبوند)[23] ولقد كانت هذه الحركة العمالية الناشئة قادرة على الصمود في وجه موجة الاحتجاجات السياسية والإضرابات، وذلك جزئياً من خلال اللعب على الانقسام بين العمال اليهود الذين كانوا يهيمنون على العمل كموظفين وحرفيين في المدينة، والعمال الروس الذين كانوا يعملون في المصانع الضخمة في الضواحي.[24] كانت هناك موجة من الهجمات المعادية للسامية. ومع تدخل الجيش ضد مجموعات الدفاع اليهودية، قُتل حوالي 100 يهودي وجُرح مائتان.[23]

وفقًا للمؤرخ المحلي أندري پورتنوڤ، كان 40% من سكان يكاترينوسلاڤ المحليين من اليهود في السنوات التي سبقت الحرب العالمية الأولى.[25]

الفترة السوڤيتية

الحرب والثورة

في أعقاب اندلاع ثورة فبراير الروسية مباشرة، في ليلة 3 مارس ت.ق. (16 مارس ت.م) إلى 4 مارس 1917، تشكلت حكومة مؤقتة في يكاترينوسلاڤ برئاسة رئيس إدارة الأراضي الإقليمية (كونستنتين فون هسبرگ).[26] كما تشكل في 4 مارس مجلس نواب العمال.[26] في 6 مارس، أقال رئيس وزراء الحكومة المؤقتة الروسية گيورگي لڤوڤ حاكم محافظة يكاترينوسلاڤ ونائب حاكمها، وسلم هذه الصلاحيات مؤقتاً إلى هسبرگ.[26] في 9 مارس تشكل مجلس نواب العمال والجنود في يكاترينوسلاڤ.[26]

في 16 مايو اندمج مجلس نواب العمال ومجلس العمال والجنود، ليصبحا مجلساً ثورياً في نوفمبر 1917.[26] كانت جميع هذه الهياكل السلطوية قائمة بازدواجية، وكانت حكومة هسبرگ المؤقتة في كثير من الأحيان في وضع غير مؤاتي.[26] عام 1917 شهدت المدينة العديد من الاجتماعات والتجمعات والمؤتمرات والمظاهرات للأحزاب من كافة الاطياف السياسية.[26] بسبب التحريض السياسي المكثف، دعمت لجان المصانع والنقابات المهنية التي تشكلت مؤخراً بحلول خريف عام 1917 البلاشڤة بشكل أساسي، مما عزز مواقفهم بشكل كبير.[26]

في يونيو 1917، أعلن المجلس المركزي (تسنترالنا رادا) للأحزاب الأوكرانية في كييڤ أن يكاترينوسلاڤ تقع ضمن أراضي جمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية المستقلة.[13] في 13 أغسطس 1917 عُقدت أول انتخابات ديمقراطية لمجلس دوما المدينة الذي يضم 120 مقعداً في يكاترينوسلاڤ.[26] حصل البلاشڤة على 23 مقعداً وحصل المنشڤك على 16 مقعداً، بينما حصلت الأحزاب الموالية لأوكرانية على 6 مقاعد.[26] أُنتخب ڤاسيل أوسيپوڤ عمدة للمدينة.[26] ظلت أوسيپوڤ عمدة حتى حل مجلس دوما المدينة في مايو 1918.[26] وفي 10 نوفمبر 1917 أقيمت مسيرة للقوات الأوكرانية، بتنظيم من قبل المجلس العسكري الأوكراني في يكاترينوسلاڤ دعماً للنظام العالمي الثالث للمجلس المركزي الأوكراني، إعلان تأسيس جمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية.[13]

في انتخابات الجمعية التأسيسية الروسية التي عُقدت في نوفمبر 1917، حصل البلاشڤة على ما يقرب من 18% من الأصوات في المحافظة، مقارنة بنسبة 46% للحزب الاشتراكي الثوري الأوكراني وحلفائه.[27] في 22 نوفمبر 1917، أعلن المجلس الثوري ومجلس دوما المدينة ولاءهما للمجلس المركزي.[26] بعدها ترك البلاشڤة هذه المجالس.[26] خلال ديسمبر، ساء الوضع في المدينة مع استعداد الجانبين للعمل العسكري.[26]

في 26 ديسمبر، تحدى البلاشڤة إنذاراً نهائياً من المجلس المركزي وبعد ثلاثة أيام من القتال عززوا سيطرتهم على المدينة.[26] وفي 12 فبراير أعلنوا يكاترينوسلاڤ جزءاً من جمهورية دونيتسك-كريڤو روگ، لكن في الشهر التالي، بموجب شروط معاهدة برست-لتوڤسك، تنازلوا عن المنطقة لجمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية المتحالفة مع ألمانيا والنمسا.[28][13]

في 5 أبريل 1918، دخل الجيش الألماني الإمبراطوري المدينة. وأُعدم أمام العامة خمسمائة من أفراد الحرس الأحمر البلشڤي المتبقين.[26]

كانت مدة ولاية جمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية رسمياً قصيرة: ففي 29 أبريل 1918، أدى تدخل قوى المحور إلى استبدال جمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية بالدولة الأكورانية أو الهيتمانات الأكثر طواعية. وفي 18 مايو 1918، أمر هيتمان الدولة الأوكرانية، پڤلو سكوروپادسكي، بإعادة المؤسسات المؤممة سابقاً إلى أصحابها السابقين، وبمساعدة القوات النمساوية المجرية، قمعت السلطات الجديدة الاحتجاجات العمالية.[26]

في 23 ديسمبر 1918، بعد هزيمتهم على يد الحلفاء الغربيين وبعد أربعة أيام من التمرد داخل المدينة، انسحبت قوات الاحتلال الألمانية والنمساوية-المجرية. بعد أربعة أيام، اقتحمت يكاترينوسلاڤ قوات [[جيش المتمردين الثوريين الأوكراني|جيش المتمردين الثوريين الأناركي الأوكراني] (ماخنوڤشينا)، مما أدى إلى فرار القوات الموالية للمديرية الجديدة التابعة لجمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية. على مدار العام التالي، تغيرت المدينة عدة مرات أخرى، حيث تنازع عليها بين جمهورية أوكرانيا الشعبية، والبيض (القوات المسلحة لروسيا الجنوبية)، والمتمردين الفلاحين التابعين نيكيفور گريگوريڤ، وماخنوڤشينا (الذي عاد مرتين)،[29] وأخيراً، تمكن البلاشڤة، الذين أعادوا تنظيم أنفسهم في الجيش الأحمر، من تأمين المدينة في 30 ديسمبر 1919.[26][30][31]

تعرضت المدينة لأضرار جسيمة وانخفض عدد سكانها، الذي بلغ حوالي 268.000 نسمة عام 1917، إلى أقل من 190.000 نسمة.[32]

التصنيع في الفترة الستالينية

في أواخر مايو 1920 تدهورت الإمدادات الغذائية إلى يكاترينوسلاڤ، مما أدى إلى موجة من الإضرابات.[32] وفي يونيو 1920، قمعت السلطات السوڤيتية إحدى هذه الاحتجاجات باعتقال 200 عامل في السكك الحديدية، وحُكم على 51 منهم بالإعدام الفوري.[32]

عام 1922 دُمجت المنطقة في جمهورية أوكرانيا الاشتراكية السوڤيتية، كإحدى جمهوريات الاتحاد السوڤيتي. عام 1922، أمرت الحكومة السوڤيتية "بأن يعاد تسمية جميع الشركات المؤممة التي تحمل أسماء مرتبطة بالشركة أو لقب المالكين القدامى تخليداً لذكرى الأحداث الثورية، وتخليداً لذكرى القادة الدوليين أو الروس أو المحليين للثورة الپروليتارية".[34] في عامي 1922 و1923 أثعيد تسمية المصانع، بالإضافة إلى عشرات الشوارع والأزقة والممرات والساحات والمنتزهات.[34] عام 1923، اتخذ مجلس المدينة قرارًا بتنظيم مسابقة لإعادة تسمية المدينة نفسها.[34]

في عام 1924، تبنى مؤتمر السوڤيت الإقليمي قرارًا بإعادة تسمية مدينة يكاترينوسلاڤ إلى كراسنودنيپروڤسك (ومحافظة يكاترينوسلاڤ إلى كراسنودنيپروڤسك). بعد ذلك، بدأت العديد من المنظمات والمؤسسات في تسمية يكاترينوسلاڤ باسم كراسنودنيپروڤسك في الوثائق الرسمية، فقط لتذكير الصحافة بأن إعادة تسمية المستوطنات لا يمكن أن يقررها إلا المجلس الرئاسي للسوڤيت الأعلى.[34] عام 1926، اعتمد مؤتمر نواب العمال والفلاحين والجنود المؤقت للمنطقة قرارًا بإعادة تسمية يكاترينوسلاڤ إلى اسم دنيپروپتروڤسك تكريمًا لرئيس مؤتمر السوڤيت لعموم أوكرانيا، گريگوري پتروڤسكي.[35][36][34]

وكان پتروڤسكي حاضراً في هذا المؤتمر وقد "قبل هذا التكريم بامتنان كبير".[34] تمت الموافقة على قرار المؤتمر بموجب قرار صادر عن المجلس الرئاسي للسوڤيت الأعلى بتاريخ 20 يوليو 1926.[34] في العشرينيات والثلاثينيات، استمر إعادة تسمية العشرات من الشوارع والأزقة والممرات والساحات والمنتزهات في المدينة، واستمر هذا في الأربعينيات وفي السنوات اللاحقة.[34]

بحلول عام 1927، أعيد بناء الصناعة في دنيپروپتروڤسك بالكامل، ووفقًا لبعض المؤشرات، فقد تجاوزت مستويات ما قبل الحرب.[32] بسبب الاكتظاظ الزراعي، وتدفق العاطلين عن العمل من مستوطنات أخرى، وارتفاع معدلات المواليد من بين أسباب أخرى، ارتفعت معدلات التوظيف والبطالة في دنيپروپتروڤسك.[32] وفي أواخر العشرينيات، اضطرت السلطات إلى مواجهة اضطرابات عمالية متزايدة. وجاء في إحدى الاحتجاجات: "لا تخنقونا، فأطفالنا يموتون جوعاً، لقد وضعنا في ظروف أسوأ من تلك التي كنا نعيشها في ظل النظام القديم".[37]

احتلت المدينة مكانة بارزة في الخطط الخمسية التي وضعها ستالين للتصنيع. عام 1932، أنتجت مصانع المعادن الإقليمية في دنيپروپتروڤسك 20% من إجمالي الحديد الزهر و25% من الفولاذ المصنع في أوكرانيا السوڤيتية. وبحلول نهاية الثلاثينيات، أصبحت منطقة دنيپروپتروڤسك الأكثر تحضرًا في أوكرانيا السوڤيتية حيث يعيش أكثر من 2.273.000 شخص في المنطقة وأكثر من نصف مليون في المدينة نفسها. أصبحت دنيپروپتروڤسك مركزًا ثقافيًا وتعليميًا مهمًا مع وجود عشر كليات وجامعة حكومية.[38]

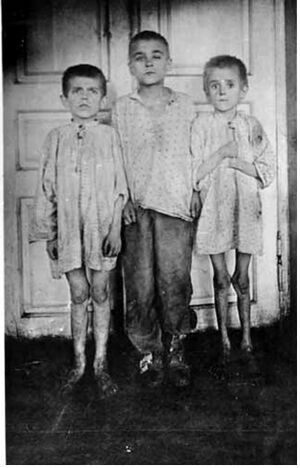

لقد دمرت سياسة الزراعة الجماعية القسرية ومصادرة الحبوب المناطق الريفية المحيطة. ومات الفلاحون بأعداد كبيرة أثناء المجاعة الكبرى عامي 1932 و1933.[39] في الفترة 1932-1933 خسر أوبلاست دنيپروپتروڤسك 3.5-9.8 مليون شخص،[40] مما يجعله واحداً من أكثر المناطق تاثراً بالمجاعة.[40]

وبفضل العمل في الصناعات الثقيلة المتوسعة، تمكن الناجون من تغيير التركيبة العرقية للمدينة. فقد ارتفعت نسبة السكان المسجلين كأوكرانيين من 36% من السكان عام 1926 إلى 54.6% في 1939. وانخفضت نسبة السكان الروس من 31.6% إلى 23.4%، وانخفضت نسبة السكان اليهود من 26.8% إلى 17.9%.[41][42] زاد عدد سكان المدينة خلال فترة ما بين الحربين العالميتين بسرعة. ففي عام 1932، بلغ عدد سكان دنيپروپتروڤسك 368.000 نسمة. وفي التعداد السوڤيتي 1939 ارتفع هذا العدد إلى أكثر من نصف مليون نسمة (500.662 نسمة).[32]

تم تنفيذ سياساة الأكرنة والكورنيزاتسيا السوڤيتية في دنيپروپتروڤسك.[32] نظم الحزب الشيوعي الأوكراني دورات خاصة في الدراسات الأوكرانية.[32] عملت السلطات السوڤيتية على زيادة عدد المدارس بشكل كبير، وبحلول منتصف الثلاثينيات تمكنت من القضاء على الأمية في المدينة.[32] وأُفتتحت جامعات جديدة.[43] في نهاية ثلاثينيات، كان في دنيپروپتروڤسك 10 مؤسسات تعليمية عليا و19 مؤسسة تعليمية خاصة.[43] في الثلاثينيات، بُني عدد كبير من المدارس الثانوية والمستشفيات الجديدة في المدينة، وتم تطوير منتزهات المدينة.[43]

وصل التطهير الكبير، بعد اغتيال سرگي كيروڤ، إلى دنيپروپتروڤسك أيضاً.[32] عام 1935، اعتقلت NKVD في دنيپروپتروڤسك 182 "تروتسكياً".[32] عام 1935، أُعدم 235 شخصاً متهمين بأنهم "أعداء داخليين"، بما في ذلك عدد قليل من عمداء الجامعات.[32] وفي 1936، أُعدم 526 شخصاً.[32] وفي 1937 قتلت إدارة NKVD المحلية 16.421 شخصاً.[32]

الاحتلال النازي

كانت مدينة دنيپروپتروڤسك تحت احتلال ألمانيا النازية منذ 26 أغسطس 1941[45] حتى 25 أكتوبر 1943.[46] كانت المدينة تُدار كجزء من مفوضية الرايخ في أوكرانيا. وقد أدى الهولوكوست في دنيپروپتروڤسك إلى تقليص عدد السكان اليهود المتبقين في المدينة، والذين تتراوح تقديراتهم من 55.000-30.000، إلى 702 فقط.[47][48] في يومين فقط، 13-14 أكتوبر 1941، قتل الألمان 15.000.[49]

أدارت ألمانيا ثلاثة معسكرات أسرى حرب في المدينة، وأهمها معسكر شتالاگ 348 مع العديد من المعسكرات الفرعية في المنطقة من أكتوبر 1941 حتى فبراير 1943، بعد نقله من جشوف في پولندا تحت الاحتلال الألماني،[50] حيث يقدر أن المحتلين قتلوا ما يزيد على 30.000 أسير حرب سوڤيتي،[51] وبإيجاز أيضاً معسكرات شتالاگ 310 وشتالاگ 387.[52]

في نوفمبر 1941، بلغ عدد سكان دنيپروپتروڤسك 233.000 نسمة. وفي مارس 1942، انخفض هذا العدد إلى 178.000 نسمة.[43] في 25 أكتوبر 1943 لم يتجاوز عدد سكان الضفة اليمنى للمدينة 5.000 نسمة.[43] وبحسب الإحصائيات الرسمية، ارتفع عدد سكان دنيپروپتروڤسك عام 1945 إلى 259.000 نسمة.[43]

المدينة المغلقة ما بعد الحرب

في وقت مبكر من يوليو 1944، قررت لجنة الدفاع الحكومية في موسكو بناء مصنع كبير لبناء الآلات العسكرية في دنيپروپتروڤسك في موقع مصنع الطائرات قبل الحرب. في ديسمبر 1945، بدأ آلاف أسرى الحرب الألمان في البناء وبناء الأقسام والمتاجر الأولى في المصنع الجديد. كان هذا هو الأساس لمصنع السيارات في دنيپروپتروڤسك. عام 1954، افتتحت إدارة مصنع السيارات هذا مكتب تصميم سرياً، أطلق عليه اسم OKB-586، لبناء القذائف العسكرية ومحركات الصواريخ.[53]

انضم إلى المشروع عالي الأمان مئات من الفيزيائيين والمهندسين ومصممي الآلات من موسكو وغيرها من المدن السوفيتية الكبرى. في عام 1965، تم نقل المصنع السري رقم 586 إلى وزارة بناء الآلات العامة والتي أعادت تسميته "مصنع بناء الآلات الجنوبي" (Yuzhnyi mashino-stroitel'nyi zavod) أو باختصار باللغة الروسية، اختصاراً يوژمش. أصبحت يوژمش عاملاً مهمًا في سباق التسلح في الحرب الباردة (تفاخر نيكيتا خروشوڤ عام 1960 بأنه ينتج صواريخ "مثل النقانق").[53]

عام 1959 كانت دنيپروپتروڤسك مغلقة أمام الزوار الأجانب.[54] لم يُسمح لأي مواطن أجنبي، حتى من دولة اشتراكية، بزيارة المدينة أو المنطقة. كانت السلطات الشيوعية تفرض على مواطنيها معايير أعلى من النقاء الأيديولوجي مقارنة ببقية السكان، وكانت حرية تنقلهم مقيدة بشدة. ولم تُفتح دنيپروپتروڤسك للزوار الدوليين ورفع القيود المدنية إلا عام 1987، أثناء الپيريسترويكا.[55]

ارتفع عدد سكان دنيپروپتروڤسك من 259.000 نسمة عام 1945 إلى 845.200 نسمة عام 1965.[43]

وعلى الرغم من نظام الحراسة المشددة، أضرب العمال في سبتمبر وأكتوبر 1972 في عدة مصانع في دنيپروپتروڤسك مطالبين بزيادة الأجور وتحسين الغذاء وظروف المعيشة والحق في اختيار الوظيفة.[56] عادت النزعة النضالية العمالية في أواخر الثمانينيات، وهي الفترة التي أدت فيها وعود الپيريسترويكا والگلاسنوست إلى رفع التوقعات الشعبية.[57] عام 1990، اندلعت أعمال شغب في سجن النساء الاحتياطي، في إشارة أخرى إلى الاضطرابات المتزايدة.[58]

Dissent and youth rebellion

In 1959 17.4% of Dnipropetrovsk students were taught in Ukrainian language schools and 82.6% in Russian language schools. 58% of the city's inhabitants self-identified as Ukrainians.[59] Compared with the other 3 biggest cities of Ukraine Dnipropetrovsk had a rather large share of education conducted in Ukrainian. In Kyiv 26.8% of pupils studied in Ukrainian and 73.1% in Russian while 66% of Kyiv residents considered themselves Ukrainian, in Kharkiv these numbers were 4.9%, 95.1% and 49%. In Odesa these numbers were 8.1%, 91.9% and 40%.[59][nb 1]

As in the overall Ukrainian SSR, Dnipropetrovsk saw an influx of young immigrants from rural Ukraine.[61] Dnipropetrovsk Oblast saw the highest inflow of rural youth of all Ukraine.[61]

According to KGB reports, in the 1960s "Samizdat" and Ukrainian diaspora publications began to circulate via Western Ukraine in Dnipropetrovsk. These fed into underground student circles where they promoted interest in the "Ukrainian Sixtiers", in Ukrainian history, especially of Ukrainian Cossacks, and in the revival of the Ukrainian language. Occasionally the blue and yellow flag of independent Ukraine was unfurled in protest.[62] The authorities responded with repression: arresting and jailing members of underground discussion groups for "nationalistic propaganda".[63]

The growing evidence of dissent in the city coincided from the late 1960s with what the KGB referred to as "radio hooliganism". Thousands of high-school and college students had become ham radio enthusiasts, recording and rebroadcasting western popular music. Annual KGB reports regularly drew a connection between enthusiasm for western pop culture and anti-Soviet behaviour.[64] In the 1980s, by which time the KGB had conceded that their raids against "hippies" had failed suppress the youth rebellion,[65][nb 2] such behaviour was reportedly found in an admixture of Anglo-American" heavy metal, punk rock and Banderism—the veneration of Stepan Bandera, and of other Ukrainian nationalists, who in the Soviet narrative were denounced and discredited as Nazi collaborators.[67]

In an attempt to provide Dnipropetrovsk youth with an ideologically safe alternative, beginning in 1976 the local Komsomol set up approved discotheques. Some of the activists involved in this "disco movement" went on in the 1980s to engage in their own illicit tourist and music enterprises, and several later became influential figures in Ukrainian national politics, among them Yulia Tymoshenko, Victor Pinchuk, Serhiy Tihipko, Ihor Kolomoyskyi and Oleksandr Turchynov.[66]

"مافيا دنيپروپتروڤسك"

وبما يعكس الأهمية الاستراتيجية الخاصة لدنيپروپتروڤسك بالنسبة للاتحاد السوڤيتي بأكمله، فقد لعب كوادر الحزب من "مدينة الصواريخ" دورًا كبيرًا ليس فقط في القيادة الجمهورية في كييڤ، بل وأيضًا في قيادة الاتحاد في موسكو.[68] أثناء التطهير الكبير الذي بدأه ستالين، سرعان ما ارتقى ليونيد بريجنيڤ داخل صفوف النومنكلاتورا المحلية،[69] من مدير معهد دنيپروپتروڤسك لتشغيل المعادن عام 1936 إلى سكرتير الحزب الإقليمي (أوبكوم) المسؤول عن صناعات الدفاع في المدينة عام 1939.[70]

في تلك المرحلة، اتخذ الخطوات الأولى نحو بناء شبكة من المؤيدين والتي عُرفت "بمافيا دنيپروپتروڤسك". قادوا الانقلاب الداخلي للحزب الذي شهد عام 1964 الذي استبدل بريجنيڤ بنيكيتا خروشوڤ كأمين عام للحزب الشيوعي السوڤيتي ودعى إلى وقف المزيد من الإصلاحات.[69]

أوكرانيا المستقلة

في استفتاء وطني أُجري في 1 ديسمبر 1991، وافق 90.36% من الناخبين في دنيپرو على إعلان الاستقلال الذي أصدره البرلمان الأوكراني في 24 أغسطس.[71] وفي خضم الاضطراب الاقتصادي والتضخم المتزايد الذي رافق انهيار الاتحاد السوڤيتي، انخفض الناتج.[72] وعلى الرغم من أن معدل انكماشها الاقتصادي كان أقل من المتوسط الوطني،[73] شهدت مدينة دنيپرو وأوبلاست دنيپروپتروڤسك واحدة من أكبر حالات الانخفاض السكاني بين جميع مناطق أوكرانيا.[74] بحلول عام 2021، انخفض عدد سكان المدينة، الذي تجاوز 1.2 مليون نسمة عام 1991، إلى 981.000 نسمة.[75] كان الشباب من دنيپروپتروڤسك من بين ملايين الأوكرانيين الذين غادروا البلاد بحثًا عن فرصة عمل في الخارج.[76]

لقد كان استمرار التداعيات الفوضوية التي خلفها انهيار الاتحاد السوڤيتي في القرن الجديد رمزاً للعديد من سكان دنيپروپتروڤسك في حادثتين عنيفتين. ففي يونيو ويوليو 2007، شهدت دنيپروپتروڤسك موجة من عمليات القتل المتسلسل المسجلة بالڤيديو والتي وصفتها وسائل الإعلام بأنها من عمل "مجانين دنيپروپتروڤسك".[77] في فبراير 2009، صدرت أحكام على ثلاثة شبان لتورطهم في 21 جريمة قتل، والعديد من الهجمات والسرقات الأخرى.[78] في 27 أبريل 2012، انفجرت أربع قنابل بالقرب من أربع محطات ترام في دنيپروپتروڤسك، مما أدى إلى إصابة 27 شخصًا.[79] ولم يدن أحد. وزعم سياسيو المعارضة أنهم رأوا يد الرئيس ڤيكتور يانوكوڤيتش عازمة على تعطيل الانتخابات البرلمانية الأوكرانية 2012 وتنصيب نظام رئاسي.[80][81]

يوروميدان

في 26 يناير 2014، حاول 3000 شخص مناهضين للرئيس الأوكراني ڤيكتور يانوكوڤيتش ومؤيدين ليوروميدان الاستيلاء على مبنى الإدارة الحكومية الإقليمية، لكنهم فشلوا.[82][83][84][85][86] كانت هناك اضطرابات في الشوارع[87] وتعرض محتجي يوروميدان للضرب على أيدي أنصار يانوكوڤيتش المأجورين (ما يسموا "بتيتوشكي").[88][89] ووصفهم كولسنيكوڤ حاكم دنيپروپتروڤسك بأنهم "بلطجية متطرفين من مناطق أخرى".[90]

وبعد يومين، دعا نحو 2000 موظف في القطاع العام إلى مظاهرة لدعم حكومة يانوكوڤيتش.[91] في هذه الأثناء، تم تدعيم المبنى الحكومي بالأسلاك الشائكة.[91][92][93] في 19 فبراير 2014، نُظم اعتصام مناهض ليانوكوڤيتش بالقرب من الإدارة الإقليمية للدولة.[94] في 22 فبراير 2014، وبعد مظاهرة أخرى مناهضة ليانوكوڤيتش، غادر عمدة المدينة إيڤان كوليتشنكو حزب المناطق الذي يتزعمه يانوكوڤيتش من أجل "السلام في المدينة".[95]

وفي الوقت نفسه، تعهد مجلس المدينة بدعم "الحفاظ على أوكرانيا كدولة واحدة لا تتجزأ"، على الرغم من أن بعض الأعضاء دعوا إلى انفصالية وفدرالية أوكرانيا.[95] في اليوم نفسه، بعد قتال شوارع في كييڤ، 22 فبراير 2014، غادر يانوكوڤيتش أوكرانيا وذهب إلى المنفى في روسيا.[96]

2014 حتى 2022

Dnipropetrovsk remained relatively quiet during the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine, with pro-Russian Federation protestors outnumbered by those opposing outside intervention.[97][98] In March 2014 the city's Lenin Square was renamed "Heroes of Independence Square" in honor of the people killed during Euromaidan.[98][99] The statue of Lenin on the square was removed.[98][100] In June 2014 another Lenin monument was removed and replaced by a monument to the Ukrainian military fighting the Russo-Ukrainian War.[101][102]

To comply with the 2015 decommunization law the city was renamed Dnipro in May 2016, after the river that flows through the city.[103][104] By summer 2016 not only was the city renamed, but so were more than 350 streets, alleys, driveways, squares and parks.[105] For example, Karl Marx Avenue, the main street, was renamed Yavornytskyi Avenue in honour of the once neglected city and cossack historian.[106] This was 12 per cent of all of the city's toponymies.[105] Five of the eight urban districts of the city received new names.[105]

الغزو الروسي لأوكرانيا 2022

في أعقاب الغزو الروسي لأوكرانيا 2022 في 24 فبراير 2022، ومع تطور الجبهات العسكرية بالقرب من كييڤ وإلى شمالًا وشرقًا وجنوبًا، أصبحت دنيپرو مركزًا لوجستيًا للمساعدات الإنسانية ونقطة استقبال للأشخاص الفارين من الحرب. وعلى مسافة متساوية تقريبًا من مسارح الحرب الرئيسية في شرقًا وجنوبًا، يثبت موقع المدينة أنه حاسم لتزويد جهود الدفاع الأوكرانية.[بحاجة لمصدر] وفي الوقت نفسه، فإن سيطرتها على معبر نهر الدنيپر والفرصة التي قد توفرها لقطع الطريق على القوات الأوكرانية في دونباس تجعل المدينة هدفًا ذا قيمة عالية بالنسبة للروس.[11][107]

يُقال إن دنيپرو هي المدينة الوحيدة في أوكرانيا التي تم فيها إنشاء تشكيل تطوعي تحت سيطرة مباشرة لمجلس المدينة. يُطلق عليه اسم "حرس دنيپرو" (Варти Дніпра, Varty Dnipra). رفض عمدة دنيپرو، بوريس فيلاتوڤ، الاقتراحات التي تفيد بأن المجموعة لا تزال "جيشًا خاصًا" لإيگور كولومويسكي. ساعد كولومويسكي في شراء بعض المعدات، لكن القوة تؤدي وظائف الدفاع والقانون والنظام تحت قيادة الشرطة الوطنية.[108]

في 11 مارس، شنت القوات الروسية أولى غاراتها على مدينة دنيپرو. وأسفرت ثلاث غارات جوية بالقرب من روضة أطفال ومبنى سكني عن مقتل شخص واحد على الأقل.[109] في 15 مارس، أصابت الصواريخ الروسية مطار دنيپرو الدولي، مما أدى إلى تدمير المدرج وإلحاق أضرار بالمبنى.[110] وفي الساعات الأولى من صباح 6 أبريل، دمرت غارة جوية مستودعًا للنفط.[111] في 10 أبريل، صرح متحدث باسم الحكومة الأوكرانية إن مطار دنيپرو "دُمر بالكامل" نتيجة لهجوم روسي.[112] وفي 15 يوليو، أسفر هجوم صاروخي روسي عن مقتل أربعة أشخاص وإصابة ستة عشر آخرين في دنيپرو.[113]

كجزء من حملة نزع الطابع الروسي التي اجتاحت أوكرانيا في أعقاب غزو فبراير 2022، تم "نزع الطابع الروسي" عن 110 اسم جغرافي في المدينة من فبراير حتى سبتمبر 2022.[114] بدأت عملية إعادة التسمية في 21 أبريل عندما أعيد تسمية 31 شارعًا مرتبطًا بروسيا. وفي مايو، أعيد تسمية 20 شارعًا آخر، ثم 21 شارعًا وزقاقًا آخر في يونيو 2022.[115] وفقًا لعمدة دنيپرو بوريس فيلاتوڤ (متحدثًا في 21 سبتمبر 2022) "هذه ليست النهاية".[114] من بين عمليات إعادة التسمية الأخرى، شارع شميدت (كان الشارع في الأصل شارع صالة الألعاب الرياضية لكن أعيد تسميته إلى شارع أوتو شميدت من قبل السلطات السوڤيتية عام 1934[34]) في وسط دنيبرو وتغير اسمه إلى شارع ستيپان بانديرا.[114][nb 3] In May 2022 (also) several outdoor objects related to the USSR were dismantled in Dnipro.[117][118] في ديسمبر 2022، أزالت مدينة دنيپرو جميع المعالم الأثرية للشخصيات الثقافية والتاريخية الروسية.[119][nb 4] في 22 فبراير 2023 أعيد تسمية 26 شارع آخر.[120]

قُصفت دنيپرو أثناء الضربات الصاروخية الروسية على البنتية التحتية الأساسية في خريف 2022.[121] وفي 10 أكتوبر لقى ثلاثة مدنيين مصرعهم.[122] في 18 أكتوبر 2022 استهدفت الضربات الصاروخية الروسية البنية التحتية للطاقة في دنيپرو.[123] في 17 نوفمبر 2022 أصيب 23 شخصاً.[124] واستمرت الهجمات في 2023.[125] كان أعنف هذه الهجمات هو الهجوم الصاروخي على مبنى سكني في 14 يناير 2023 أسفر عن مقتل 40 شخصًا وإصابة 75 آخرين وفقدان 46 شخصًا.[126]

في 21 نوفمبر 2024، أعلنت أوكرانيا أن روسيا أطلقت صاروخاً باليستياً عابراً للقارات استهدف مدينة دنيپرو بوسط شرق البلاد، وهي المرة الأولى التي تستخدم فيها موسكو مثل هذا الصاروخ في الحرب.[127] وإن تأكد إطلاق روسيا لصاروخ باليستي عابر للقارات، فإنه يُعد أول استخدام قتالي لمثل هذا السلاح في التاريخ العسكري. وأكدت القوات الجوية الأوكرانية الضربة، مشيرة إلى أن الصاروخ تسبب في أضرار بمؤسسة صناعية ومركز لإعادة التأهيل، مما أدى إلى اشتعال الحرائق. وجرى إطلاق الصاروخ، الذي تم تحديده على أنه غير نووي، من منطقة أستراخان الروسية. وأشار المسؤولون الأوكرانيون إلى أن هذا التطور يصعد بشكل كبير من الحرب المستمرة منذ أكثر من ألف يوم.

وأفادت التقارير أن الضربة ألحقت أضرارًا بالبنية التحتية الحيوية. فيما تكهنت وسائل الإعلام الروسية بأن الصاروخ المستخدم ربما كان من طراز RS-26 Rubezh، وهو سلاح قادر على حمل رؤوس حربية نووية وتقليدية. ويوصف صاروخ RS-26 بأنه صاروخ فرط صوتي يتجاوز مداه 5500 كيلومتر، مما يجعل اعتراضه أمراً صعباً للغاية. وأفادت القوات الجوية الأوكرانية أيضًا أنه إلى جانب الصاروخ الباليستي العابر للقارات، أطلقت روسيا صاروخًا فرط صوتي من طراز كينجال وسبعة صواريخ كروز من طراز Kh-101، حيث اعترضت الدفاعات الأوكرانية معظمها.

تأتي هذه الضربة الغير مسبوقة، في سياق التصعيد الذي بدأ مع استخدام أوكرانيا لأسلحة بعيدة المدى قبل أيام، بما في ذلك صواريخ إم142 هايمارز الأميركية، وصواريخ ستورم شادو البريطانية الفرنسية، وشنت هجمات في عمق الأراضي الروسية. وكان الكرملين قد حذر في وقت سابق من أن مثل هذه الإجراءات من شأنها أن تكون لها إجراءات انتقامية.

كماء جاءت بعد يومين من تعديل الرئيس الروسي فلاديمير بوتن للعقيدة النووية لبلاده، حين أعلن في 19 نوفمبر أن العدوان من الدول غير النووية المدعومة بالقوى النووية سيُنظر إليه على أنه تهديد مباشر لسيادة روسيا.

من ناحيتها لم تؤكد أو تنفي موسكو استخدام الصاروخ الباليستي العابر للقارات، واعتبر المتحدث باسم الكرملين دميتري پسكوڤ الأسئلة المتعلقة باستخدام الصاروخ يجب أن تعود للسلطات العسكرية. فيما قالت وزارة الدفاع الروسية، أن أنظمة الدفاع الجوي اعترضت صاروخين من طراز ستورم شادو وستة صواريخ من طراز إم142 هايمارز و67 طائرة بدون طيار أطلقتها أوكرانيا.

أما أندريه باكليتسكي من معهد الأمم المتحدة لبحوث نزع السلاح، فقد وصف الحادث بأنه "غير مسبوق"، مشيراً إلى أن مثل هذه الأسلحة مخصصة عادة للردع الاستراتيجي بسبب تكلفتها ودقتها. وقال باكليتسكي في منشور على موقع إكس: "إذا كان هذا صحيحا، فسيكون هذا غير مسبوق تماما وأول استخدام عسكري فعلي للصواريخ الباليستية العابرة للقارات. وليس من المنطقي أن يحدث هذا نظرا لسعرها ودقتها".[128]

Government and politics

Government

The City of Dnipro is governed by the Dnipro City Council. It is a city municipality that is designated as a separate district within its oblast.

Administratively, the city is divided into urban districts. Presently, there are 8 of them. Aviatorske, a rural settlement located near the Dnipro International Airport, is also a part of Dnipro urban hromada.

The City Council Assembly makes up the administration's legislative branch, thus effectively making it a city 'parliament' or rada. The municipal council is made up of 12 elected members, who are each elected to represent a certain district of the city for a four-year term. The council has 29 standing commissions which play an important role in the oversight of the city and its merchants.

Until 18 July 2020, Dnipro was incorporated as a city of oblast significance, the centre of Dnipro Municipality and extraterritorial administrative centre of Dnipro Raion. The municipality was abolished in July 2020 as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast to seven. The area of Dnipro Municipality was merged into Dnipro Raion.[129][130]

Dnipro is also the seat of the oblast's local administration controlled by the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast Rada. The Governor of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast is appointed by the President of Ukraine.

Subdivisions

| Code | Name of urban district | Year of creation | Area (hectares) | Population in 2006 | Prominent streets and areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nyzhniodniprovskyi | 1918/1926 | 7,162.6 | 154,400 | Streets: Vulytsia Peredova, Prospekt Manuilyvskyi, Prospekt Slobozhanskyi, Vulytsia Kalynova, Vulytsia Vidchyznyana, Vulytsia Yantarna, Donetske Shose Areas: Amur, Nyzhniodniprovsk, Kyrylivka, Borzhom, Sultanivka, Sakhalin, Berezanivka, Soniachnyi mikroraion, Lomivka, Livoberezhnyi mikroraion 1 and 2. |

| 2 | Shevchenkivskyi | 1973 | 3,145.2 | 152,000 | Streets: Prospekt Bohdana Khmelnytskoho, Vulytsia Mykhaila Hrushevskoho/Vulytsia Sichovykh Striltsiv, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, Vulytsia Sviatoslava Khorobroho, Zaporizke Shosse, Vulytsia Krotova Areas: Tsentr, Slobodka, Razvlika-Pidstantsiya, 12th Kvartal, Topol mikroraion 1, 2 and 3, Myrnyi, Danyla Nechaia. |

| 3 | Sobornyi | 1935 | 4,409.3 | 169,500 | Streets: Prospekt Gagarina, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, Sicheslavska naberezhna/Peremogy, Vulytsia Volodymyra Vernadskoho, Vulytsia Hoholya, Vulytsia Chesnyshevskoho, Vulytsia Kosmichna, Vulytsia Yasnopolianska Areas: Tsentr, Nahirny (Tabirny), Pidstantsiia, Sokil mikroraion 1 and 2, Peremoha mikroraion 1–6, Mandrykivka, Lotskamianka, Tunelna Balka, Monastyrskyi Ostriv, Kosa. |

| 4 | Industrialnyi | 1969 | 3,267.9 | 132,700 | Streets: Prospekt Slobozhanskyi, Prospekt Petra Kalnyshevskoho, Vulytsia Osinnia, Vulytsia Baykalska, Vulytsia Vinokurova Areas: Klochko, Samarivka (Yozhefstal), Oleksandrivka, Livoberezhnyi mikroraion 1–3; (Nyzhniodniprovskyi Pipe Production Plant). |

| 5 | Tsentralnyi | 1932 | 1,040.3 | 67,200 | Streets: Vulytsia Staryi Shliakh, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, Prospekt Pushkina, Vulytsia Yaroslava Mudroho, Vulytsia Voitsekhovycha, Vulytsia Korolenko, Prospekt Bohdana Khmelnytskoho, Staromostova Square Areas: Dniprovsky Avtovokzal, Dniprovsky Richkovy Vokzal and Dnipro River Port. |

| 6 | Chechelivskyi | 1933 | 3,589.7 | 120,600 | Vulytsia Robitnycha, Prospekt Nigoyana, Prospekt Pushkina, Vulytsia Kirovozhska, Vulytsia Makarova, Vulytsia Titova, Vulytsia Budivelnykiv, Prospekt Bohdana Khmelnytskoho Areas: Chechelivka, Aptekarska Balka/Shliakhivka, 12th Kvartal, Krasnopillia, (Pivdenmash). |

| 7 | Novokodatskyi | 1920 | 10,928 | 157,400 | Streets: Vulytsia Naberezhna Zavodska, Prospekt Nihoiana, Prospekt Mazepy, Prospekt Metallurhiv, Vulytsia Kyivska, Vulytsia Kommunarovska, Prospekt Svobody, Vulytsia Brativ Trofimovykh, Vulytsia Mostova, Vulytsia Maiakovskoho, Vulytsia Budennoho Areas: Toromske, Diyevka, Sukhachivka, Yasny, Novi Kaidaky, Sukhyi Ostriv, Chervonyi Kamin mikroraion, Kommunar mikroraion, Parus mikroraion 1 and 2, Zakhidnyi mikroraion, Petrovskyi Factory and other metallurgical plants. |

| 8 | Samarskyi | 1977 | 6,683.4 | 77,900 | Streets: Vulytsia Marshala Malinovskoho, Vulytsia Molodohvardiiska, Vulytsia Semaforna, Vulytsia Tomska, Vulytsia Kosmonavta Volkova, Vulytsia 20 rokiv Peremohy, Vulytsia Havanska Areas: Chapli, Prydniprovsk, Ihren, Rybalske (Fischersdorf), Odinkivka, Shevchenko, Pivnichnyi mikroraion, Nyzhniodniprovsk-Vuzol. |

Five of the eight urban districts were renamed late November 2015 to comply with decommunization laws.[131]

السياسة

In the first decades of Ukrainian independence the city's voters generally favoured the proponents of continued close ties to Russia: in the 1990s the Communist Party of Ukraine, and in the new century, the Party of Regions.[132][133] After the 2014 events of Euromaidan, which included demonstrations and clashes in the central city, the Party of Regions ceded influence to those parties and independents calling for closer ties to the European Union.

As in Soviet Ukraine, Dnipropetrovsk was disproportionately represented among political leaders in Kyiv.[54] The principal representatives of the so-called "Dnipropetrovsk Faction" in the capital were Ukraine's second president Leonid Kuchma and Ukraine's 10th and 13th prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko.[134] Kuchma was a former senior manager of Yuzhmash[134] while Tymoshenko was president of United Energy Systems of Ukraine, a Dnipropetrovsk-based private company that from 1995 to 1997 was the main importer of Russian natural gas to Ukraine.[135]

Kuchma's 1994 presidential campaign had been financed by Dnipropetrovsk businessmen Ihor Kolomoyskyi and Gennadiy Bogolyubov. Kolomoyskyi and Bogolyubov were partners in Privat Group, a scandal-ridden financial-industrial conglomerate.[136] As prime Minister, Kuchma had granted their PrivatBank the unique privilege of opening overseas branches. These were later implicated in the wholesale defrauding of Ukrainian depositors, leading to the bank's nationalization in 2016.[137][138] Kuchma was also closely tied to another budding Dnipropetrovsk billionaire, his son-in-law Viktor Pinchuk whose assets included several giant steel and pipe plants in the region and the bank Kredit-Dnepr.[134]

With Viktor Yushchenko, Tymoshenko co-led the Orange Revolution which annulled the declared victory of Viktor Yanukovych in the 2004 presidential election,[139] and under President Yuschenko served as prime minister from 24 January to 8 September 2005, and again from 18 December 2007 to 4 March 2010. Yanukovych narrowly defeated Tymoshenko in the 2010 presidential election, taking 41.7 per cent of the vote in the Dnipropetrovsk region.[140] The candidates accused one another of vote rigging.[141][142]

In the October 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election Yanukovych's Party of Regions, which promoted itself as the champion of the language rights and industrial interests of largely Russian-speaking eastern Ukraine, won 35.8 per cent of the vote in the Dnipropetrovsk region, compared to 18.4 per cent for Tymoshenko's Fatherland Party and 19.4 per cent for the Communists.[143] Tymoshenko mounted a hunger strike to once again protest election irregularities.[144]

On 2 March 2014, following the removal of Yanukovich as President, acting President Oleksandr Turchynov appointed Ihor Kolomoyskyi Governor of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast.[145] Kolomoyskyi initially dismissed suggestions of Russian-backed separatism in Dnipropetrovsk,[146][147] but then took vigorous measures. He posted bounties for the capture of Russian-backed militants and the surrender of weapons;[148][149] drafted thousands of Privat Group employees as auxiliary police officers;[150] and is said to have provided substantial funds to create the Dnipro Battalion,[151][152] and to support the Aidar, Azov, and Donbas volunteer battalions.[153][154]

In the Dnipropetrovsk region, Petro Poroshenko won the May 2014 presidential election with 45 per cent, but in the 2014 parliamentary election in October his political party Petro Poroshenko Bloc secured 19.4 per cent of the vote, 5 points behind the Opposition Bloc,[155] the successor to the disbanded Party of Regions.[156][157]

On 25 March 2015, following a struggle with Kolomoyskyi for control the state-owned oil pipeline operator,[158] President Poroshenko replaced Kolomoyskyi as governor with Valentyn Reznichenko.[159][160][161]

In the 2015 Ukrainian local elections Borys Filatov of the patriotic UKROP[162] was elected Mayor of Dnipro.[163]

In the March–April 2019 Ukrainian presidential election Dnipro voted overwhelmingly voted for the successful candidate, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who advocated membership of European Union.[164][165] In the parliamentary election in October, his Servant of the People party swept the board, winning each of Dnipro's five single-mandate parliamentary constituencies.[166][167]

By the time of the October 2020 Ukrainian local elections, support for Zelenskyy's party had collapsed: it won just 8.7 per cent of the vote for the city council.[168] The Euromaidan trajectory was represented instead by Filatov's Proposition (the "Party of Mayors"),[169] with 60 per cent of the popular vote against 30 per cent for the pro-Russian the Opposition Platform – For Life.[170][nb 5]

الجغرافيا

The city is built mainly upon both banks of the Dnieper, at its confluence with the Samara River. In the loop of a major meander, the Dnieper changes its course from the north west to continue southerly and later south-westerly through Ukraine, ultimately passing Kherson, where it finally flows into the Black Sea.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Nowadays both the north and south banks play home to a range of industrial enterprises and manufacturing plants. The airport is located about 15 km (9.3 mi) south-east of the city.

The centre of the city is constructed on the right bank which is part of the Dnieper Upland, while the left bank is part of the Dnieper Lowland. The old town is situated atop a hill that is formed as a result of the river's change of course to the south. The change of river's direction is caused by its proximity to the Azov Upland located southeast of the city.[بحاجة لمصدر]

One of the city's streets, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, links the two major architectural ensembles of the city and constitutes an important thoroughfare through the centre, which along with various suburban radial road systems, provides some of the area's most vital transport links for both suburban and inter-urban travel.

المناخ

Under the Köppen–Geiger climate classification system, Dnipro has a humid continental climate (Dfa/Dfb).[173] Snowfall is more common in the hills than at the city's lower elevations. The city has four distinct seasons: a cold, snowy winter; a hot summer; and two relatively wet transition periods. However, according to other schemes (such as the Salvador Rivas-Martínez bioclimatic one), Dnipro has a Supratemperate bioclimate, and belongs to the Temperate xeric steppic thermoclimatic belt, due to high evapotranspiration.[174]

During the summer, Dnipro is very warm (average day temperature in July is 24 إلى 28 °C (75 إلى 82 °F), even hot sometimes 32 إلى 36 °C (90 إلى 97 °F)). Temperatures as high as 36 °C (97 °F) have been recorded in May. Winter is not so cold (average day temperature in January is −4 إلى 0 °C (25 إلى 32 °F), but when there is no snow and the wind blows hard, it feels extremely cold. A mix of snow and rain happens usually in December.

The best time for visiting the city is in late spring (late April and May), and early in autumn: September, October, when the city's trees turn yellow. Other times are mainly dry with a few showers.[175]

"However, the city is characterized with significant pollution of air with industrial emissions."[176] The "severely polluted air and water" and allegedly "vast areas of decimated landscape" of Dnipro and Donetsk are considered by some to be an environmental crisis.[177] Though exactly where in Dnipropetrovsk these areas might be found is not stated.[177]

| بيانات المناخ لـ Dnipro (1991–2020, extremes 1948–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °س (°ف) | 12.3 (54.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

36.1 (97.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

39.8 (103.6) |

40.9 (105.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

32.6 (90.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

40.9 (105.6) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | −0.9 (30.4) |

0.6 (33.1) |

7.1 (44.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.7 (83.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

5.8 (42.4) |

0.6 (33.1) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | −3.6 (25.5) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | −6.1 (21.0) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

11.0 (51.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

5.3 (41.5) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | −30.0 (−22.0) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−19.2 (−2.6) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−17.9 (−0.2) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−30.0 (−22.0) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 50 (2.0) |

43 (1.7) |

51 (2.0) |

39 (1.5) |

51 (2.0) |

64 (2.5) |

55 (2.2) |

45 (1.8) |

42 (1.7) |

39 (1.5) |

44 (1.7) |

46 (1.8) |

569 (22.4) |

| متوسط عمق الثلج الكثيف cm (inches) | 7 (2.8) |

10 (3.9) |

5 (2.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

4 (1.6) |

10 (3.9) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 132 |

| متوسط الرطوبة النسبية (%) | 87.7 | 84.6 | 79.2 | 66.8 | 62.2 | 66.2 | 64.7 | 62.4 | 69.5 | 77.2 | 86.5 | 88.3 | 74.6 |

| Mean monthly ساعات سطوع الشمس | 50 | 74 | 132 | 196 | 266 | 281 | 310 | 285 | 211 | 142 | 62 | 37 | 2٬046 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[178] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (humidity 1981–2010, sun 1991–2020)[179][180] | |||||||||||||

أفق المدينة

Dnipro is a primarily industrial city of around one million people. It has developed into a large urban centre over the past few centuries to become, today, Ukraine's fourth-largest city after Kyiv, Kharkiv and Odesa. Stalinist architecture (monumental soviet classicism) dominates in the city centre.[181]

Immediately after its foundation Yekaterinoslav, began to develop exclusively on the right bank of the Dnieper River. At first the city developed radially from the central point provided by the Transfiguration Cathedral, completed in 1835.[14] Neoclassical structures of brick and stone construction were preferred and the city began to take on the appearance of a typical European city of the era. Many of these buildings have been retained in the city's older Sobornyi District.[182] Among the most important buildings of this era are the Transfiguration Cathedral, and a number of buildings in the area surrounding Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, including the Khrennikov House.

Over the next few decades, until the final end of the Russian Empire with the October Revolution in 1917, the city did not change much in appearance. The predominant architectural style remained neo-classicism. Notable buildings built in the era before 1917 include the main building of the Dnipro Polytechnic, which was built in 1899–1901,[183] the art-nouveau inspired building of the city's former Duma (parliament),[184] the Dnipropetrovsk National Historical Museum, and the Mechnikov Regional Hospital. Other buildings of the era that did not fit the typical architectural style of the time in Dnipropetrovsk include,[185] the Ukrainian-influenced Grand Hotel Ukraine, the Russian revivalist style railway station (since reconstructed),[186] and the art-nouveau Astoriya building on Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt.

Once Yekaterinoslav became part of the Soviet Union (officially in 1922), and became Dnipropetrovsk in 1926,[35] the city was gradually purged of tsarist-era monuments. Monumental architecture was stripped of Imperial coats of arms and other non-socialist symbolism. Following the 1917 October Revolution, a monument to Catherine the Great that stood in front of the Mining Institute was replaced with one of Russian academic Mikhail Lomonosov.[19]

Later, due to damage from World War II, badly damaged buildings were, more often than not, demolished completely and replaced with new structures.[187] In the early 1950s, during the ongoing industrialisation of the city, much of Dnipropetrovsk's centre was rebuilt in the Stalinist style of Socialist Realism.[188] This is one of the main reasons why much of Dnipro's central avenue, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt (formerly Karl Marx Prospect), is designed in the style of Stalinist Social Realism.[189] A number of large buildings were reconstructed. The main railway station, for example, was stripped of its Russian-revival ornamentation and redesigned in the style of Stalinist social-realism.[190]

The Grand Hotel Ukraine survived the war but was later simplified much in design, with its roof being reconstructed in a typical French mansard style as opposed to the ornamental Ukrainian Baroque of the pre-war era. Many pre-revolution buildings were reconstructed to suit new purposes. For example, the Emperor Nicholas II Commercial Institute in the city was reconstructed to serve as the administrative centre for the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, a function it fulfils to this day. Other buildings, such as the Potemkin Palace were given over to "the proletariat" (the working man), in this case as the students' union of the Oles Honchar Dnipro National University.

After the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and the appointment of Nikita Khrushchev as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the industrialisation of Dnipropetrovsk became even more profound, with the Southern (Yuzhne) Missile and Rocket factory being set up in the city. However, this was not the only development and many other factories, especially metallurgical and heavy-manufacturing plants, were set up in the city.[191]

As a result of all this industrialisation the city's inner suburbs became increasingly polluted and were gradually given over to large, industrial enterprises. At the same time the extensive development of the city's left bank and western suburbs as new residential areas began.[191] The low-rise tenant houses of the Khrushchev era (Khrushchyovkas) gave way to the construction of high-rise prefabricated apartment blocks (similar to German Plattenbaus). In 1976, in line with the city's 1926 renaming, a large monumental statue of Grigoriy Petrovsky was placed on the square in front of the city's railway station.[193][194]

Since the independence of Ukraine in 1991 and the economic development that followed, a number of large commercial and business centres have been built in the city's outskirts. To this day the city is characterised by its mix of architectural styles, with much of the city's centre consisting of pre-revolutionary buildings in a variety of styles, stalinist buildings and constructivist architecture, while residential districts are, more often than not, made up of aesthetically simple, technically outdated mid-rise and high-rise housing stock from the Soviet era. Despite this, the city has a large number of 'private sectors' where the tradition of building and maintaining individual detached housing has continued to this day.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The local statue of Lenin was toppled by protesters in February 2014 the day after Ukraine's president Viktor Yanukovych fled to Russia following months of protests against him.[195][196] The square were the statue had stood for some 50 years was soon renamed from "Lenin Square" to "Heroes of Maidan Square".[195]

In late November 2015 about 300 streets, 5 of the 8 city districts and one metro station were renamed to comply with decommunization laws.[131]

The 1976 Petrovsky statue was destroyed by an angry mob on 29 January 2016.[193]

As part of the derussification campaign that swept through Ukraine following the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, 110 toponyms in the city were renamed from February to September 2022.[114] On 3 May 2022 alone more than a dozen memorials erected during Soviet times were dismantled.[118][117] In December 2022 the Dnipro communal services (in accordance a decision of the City Council) removed from the city all monuments to figures of Russian culture and history.[119] This this meant that monuments to Alexander Pushkin, Alexander Matrosov, Volodia Dubinin, Maxim Gorky, Valery Chkalov, Yefim Pushkin and Mikhail Lomonosov were removed from the public space of the city.[119] On 16 November 2022 Pushkin Avenue in Dnipro had been renamed Lesya Ukrainka Avenue.[116] In January 2023 a T-34 tank on Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt that served as a monument to Hero of the Soviet Union Yefim Pushkin was removed after the Dnipro City Council had decided the monument "has no historical or artistic value."[197][198][nb 6] 26 more streets were renamed in Dnipro on 22 February 2023.[120] In December 2023 the renaming of streets continued with on 20 December 2023 again 53 city toponyms their names being changed by the Dnipro City Council.[200] Also on this day the Dnipro City Council renamed a part of Dnipro's central avenue, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, in honor of commander of the 1st Mechanized Battalion of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and Hero of Ukraine Dmytro Kotsiubailo (who had perished on 7 March 2023 in battle near Bakhmut).[201] On 31 January 2024 92 other toponyms were renamed by the Dnipro City Council, including the avenue named after (Soviet cosmonaut and first human in space) Yuri Gagarin.[192][202]

- Architecture and historically significant sites and monuments in Dnipro

Stalinist architecture blends with the post-modernism of Dnipro's 'Passage' shopping and entertainment centre[203]

التوزيع السكانى

| السنة | العرق | المواطنون الأجانب |

Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian | Ukrainian | Jewish | Polish | German | |||

| 1897 | 47,200 | 17,787 | 39,979 | 3,418 | 1,438 | 1,075 | [204] |

| 1897 | 42.6% | 16.0% | 36.1% | 3.1% | 1.3% | 1.0% | [204] |

| 1904(?) | 52% | 40% | 4.5% | Not Stated | Not Stated | [205] | |

الاقتصاد

| Year | Factories & Plants |

Employees | Production Volume[206] | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| roubles | 2007 £ million |

2007 USD million | ||||

| 1880 | 49 | 572 | 1,500,000 | £10.5 m | $21 m | [204] |

| 1903 | 194 | 10,649 | 21,500,000 | £177.5 m | $355 m | [204] |

| Year | Enterprises | Earnings[206][207] | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| roubles | 2007 £ million |

2007 USD million | |||

| 1900 | 1,800 | 40,000,000 | £328.7 m | $658 m | [205] |

| 1940 | 622 | 1,096,929,000 | £2,120.3 m | $4,242 m | [204] |

الثقافة

قائمة من رؤساء البلديات ورؤساء السياسية للإدارة المدينة

| Date | Name in English | Name | Post |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jun 1786–1787 | Ivan Shevelev | Шевелев Иван | mayor |

| 1791–1794 | Dmitri Yemelianovich Goriainov | Горяинов Дмитрий Емельянович | mayor |

| 1794–1796 | Peter Ivanovich Bashmakov | Башмаков Петр Иванович | mayor |

| 1796–1797 | Gregory Kustov | Кустов Григорий | mayor |

| 1797–1800 | Dmitri Yemelianovich Goriainov | Горяинов Дмитрий Емельянович | mayor |

| 1800–1803 | Kuzma Molchanov | Молчанов Кузьма | mayor |

| 1803–1806 | Peter Chetverikov | Четвериков Петр | mayor |

| 1806–1809 | Athanasius Kokhanov | Коханов Афанасий | mayor |

| 1809–1811 | Stephan Chetverikov | Четвериков Степан | mayor |

| 1811–1812 | Dmitri Yemelianovich Goriainov | Горяинов Дмитрий Емельянович | mayor |

| 1812–1817 | Ivan Vasilievich Kolesnikov | Колесников Иван Васильевич | mayor |

| 1818–1821 | Demian Kiselev | Киселев Демьян | mayor |

| 1821–1825 | Ivan Vasilievich Kolesnikov | Колесников Иван Васильевич | mayor |

| 1825–1828 | Jacob Andreivich Rokhlin | Рохлин Яков Андреевич | mayor |

| Jan 1828 – Apr 1828 | Ivan Stepanovich Pcholkin | Пчелкин Иван Степанович | mayor |

| Apr 1828 – Sep 1828 | Ivan Vasilievich Kolesnikov | Колесников Иван Васильевич | mayor |

| 1830–1833 | Fedor Safronovich Duplenko | Дупленко Федор Сафронович | mayor |

| 1833–1834 | Jacob Andreivich Rokhlin | Рохлин Яков Андреевич | mayor |

| 1834–1836 | Andrei Ivanovich Kirpishnikov | Кирпишников Андрей Иванович | mayor |

| 1836–1839 | Jacob Andreivich Rokhlin | Рохлин Яков Андреевич | mayor |

| 1839–1842 | Ivan Timothyvich Artamonov | Артамонов Иван Тимофеевич | mayor |

| 1842–1843 | Ilya Ivanovich Tarkhov | Тархов Илья Иванович | mayor |

| 1843–1846 | Thomas Fedorovich Bogdanov | Богданов Фома Федорович | mayor |

| 1846–1847 | Procopius Andreivich Belyavskii | Белявский Прокопий Андреевич | acting mayor |

| 1847–1851 | Ivan Izotovich Lovyagin | Ловягин Иван Изотович | mayor |

| Apr 1851–1854 | Procopius Andreivich Belyavskii | Белявский Прокопий Андреевич | mayor |

| 1854–1860 | Ivan Izotovich Lovyagin | Ловягин Иван Изотович | mayor |

| 1860–1861 | Yegor Ptitsyn | Птицын Егор | acting mayor |

| Nov 1861–1864 | Ivan Izotovich Lovyagin | Ловягин Иван Изотович | mayor |

| 1864–1864 | Dei Mikhailovich Minakov | Минаков Дей Михайлович | acting mayor |

| 1864–1865 | Konstantin Demyanovich Kiselev | Киселев Константин Демьянович | mayor |

| 1865–1868 | Dei Mikhailovich Minakov | Минаков Дей Михайлович | mayor |

| 1868–1871 | DV Pcholkin | Пчелкин Д. В. | mayor |

| 1871–1877 | Dei Mikhailovich Minakov | Минаков Дей Михайлович | mayor |

| 1877–1885 | Peter Vasilievich Kalabuhov | Калабухов Петр Васильевич | mayor |

| 1885–1888 | Ivan Mikhailovich Yakovlev | Яковлев Иван Михайлович | mayor |

| 7 Feb 1889–1893 | Alexander Yakovlevich Tolstikov | Толстиков Александр Яковлевич | mayor |

| 1893–1901 | Ivan Gavrilovic Grekov | Греков Иван Гаврилович | mayor |

| 1901–1901 | Alexander Yakovlevich Tolstikov | Толстиков Александр Яковлевич | mayor |

| 1901–1902 | Peter Filippovich Volkov | Волков Петр Филиппович | acting mayor |

| 1902 – Nov 1905 | Alexander Yakovlevich Tolstikov | Толстиков Александр Яковлевич | mayor |

| Nov 1905 – 26 Nov 1909 | Ivan Yakovlevich Esau | Эзау Иван Яковлевич | mayor |

| 1909 – 17 Mar 1917 | Ivan Vasilievich Sposobny | Способный Иван Васильевич | mayor |

| 1917–1917 | Konstantin Igorevich Makarenko | Макаренко Константин Игорьевич | acting mayor |

| Aug 1917–1917 | Vasily Ivanovich Osipov | Осипов Василий Иванович | mayor |

| 1918 – 1 Feb 1919 | Ivan Yakovlevich Esau | Эзау Иван Яковлевич | mayor |

| 1927–1928 | F Ryazanov | Рязанов Ф. | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1929–1929 | Bogdanova | Богданова | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1929–1933 | Sorokin | Сорокин | head of the municipal council (soviet) |

| 1930–1932 | Fedor Ivanovich Zaitsev | Зайцев Федор Иванович | first secretary of the city party committee |

| 1933–1933 | Kisilev | Кисилев | head of the municipal council (soviet) and urban executive committee |

| 1933–1933 | Nikolai Vasilievich Golubenko | Голубенко Николай Васильевич | head of the municipal council (soviet) and urban executive committee |

| 1933–1936 | Ivan Andreevich Gavrilov | Гаврилов Иван Андреевич | head of the municipal council (soviet) and urban executive committee |

| 1934–1934 | Miroshnichenko | Мирошниченко | head of the municipal council (soviet) and urban executive committee |

| 1935–1935 | Belyaev | Беляев | head of the municipal council (soviet) and urban executive committee |

| 1935–1936 | Rudenko | Руденко | head of the municipal council (soviet) and urban executive committee |

| Dec 1936 – Jul 1937 | Peter Constantinovich Vetrov | Ветров Петр Константинович | municipal party committee secretary |

| 1937–1937 | Petrichenko | Петриченко | head of the municipal council (soviet) and urban executive committee |

| Nov 1937 – 24 Feb 1938 | Demian Sergeivich Korotchenko | Коротченко Демьян Сергеевич | acting first secretary of the municipal committee CP |

| 24 Feb 1938 – Jun 1938 | Semen Borisovich Zadionchenko | Задионченко Семен Борисович | acting first secretary of the municipal committee CP |

| Jun 1938 – Jul 1941 | Semen Borisovich Zadionchenko | Задионченко Семен Борисович | first secretary of the urban committee CP |

| 1938–1938 | Khrenov | Хренов | head of the municipal council (soviet) and urban executive committee |

| 1939–1939 | Martynov | Мартынов | head of the municipal council (soviet) and urban executive committee |

| Dec 1939 – Jul 1941 | Nikolai Anisimovich Shchelokov | Щелоков Николай Анисимович | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1941–1942 | Klostermann | Клостерман | commissioner of the city on behalf of the Third Reich |

| 1941–1943 | PT Sokolovsky | Соколовский П. Т. | head of city council |

| 1943–1945 | Didenko Gavrilovich Manzyuk | Манзюк Николай Гаврилович | first secretary of the city party committee |

| 1943–1944 | GP Vinnik | Винник Г. П. | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1944–1945 | Gerasimov | Герасимов | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1945–1947 | Pavel Andreevich Naydenov | Найденов Павел Андреевич | first secretary of the urban committee CP |

| 1945–1952 | Nikolai Evstafevich Gavrilenko | Гавриленко Николай Евстафьевич | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1947–1950 | Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev | Брежнев Леонид Ильич | first secretary of the urban committee CP |

| 1952–1957 | Nikolai Andreevich Raspopov | Распопов Николай Андреевич | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1957–1963 | Nikolai Evstafevich Gavrilenko | Гавриленко Николай Евстафьевич | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1961–1964 | Viktor Mikhailovich Chebrikov | Чебриков Виктор Михайлович | first secretary of the city party committee |

| 1963–1964 | Grigory Mikhailovich Sokurenko | Сокуренко Григорий Михайлович | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1964–1967 | Boris Ivanovich Karmazin | Кармазин Борис Иванович | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1964–1970 | Ivan Vasilievich Yatsuba | Яцуба Иван Васильевич | first secretary of the city party committee |

| 1967–1970 | Eugene Viktorovich Kachalovskaya | Качаловский Евгений Викторович | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1970–1974 | Eugene Viktorovich Kachalovskaya | Качаловский Евгений Викторович | first secretary of the city party committee |

| 1970–1974 | Victor Grigorievich Boyko | Бойко Виктор Григорьевич | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1974–1976 | Victor Grigorievich Boyko | Бойко Виктор Григорьевич | first secretary of the city party committee |

| 1974–1981 | Ivan Afanasievich Lyakh | Лях Иван Афанасьевич | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1976–1983 | Vladimir Petrovich Oshko | Ошко Владимир Петрович | first secretary of the city party committee |

| 1981–1989 | Alexander Vasilivich Migdeev | Мигдеев Александр Васильевич | chief of municipal executive committee |

| 1983–1988 | Nikolai Grigorievich Omelchenko | Омельченко Николай Григорьевич | first secretary of the city party committee |

| Dec 1988–1991 | Vladimir Grigorievich Yatsuba | Яцуба Владимир Григорьевич | first secretary of the city party committee |

| Oct 1989 – Mar 1991 | Pustovoitenko, Valery Pavlovich | Пустовойтенко Валерий Павлович | chief of municipal executive committee |

| Oct 1990–1991 | Vladimir Grigorievich Yatsuba | Яцуба Владимир Григорьевич | head of city council |

| Mar 1991 – Apr 1993 | Valery Pavlovich Pustovoitenko | Пустовойтенко Валерий Павлович | head of city council |

| 1991–1993 | Valery Pavlovich Pustovoitenko | Пустовойтенко Валерий Павлович | chief of municipal executive committee |

| Apr 1993 – Jun 1994 | Victor Timothyvich Merkushov | Меркушов Виктор Тимофеевич | head of the committee and city council |

| Jun 1994 – Oct 1999 | Nikolai Antonovich Shvets | Швец Николай Антонович | head of the committee and city council |

| Apr 1999 – Jan 2000 | Ivan Ivanovich Kulichenko | Куличенко Иван Иванович | acting mayor |

| Jan 2000–present | Ivan Ivanovich Kulichenko | Куличенко Иван Иванович | mayor |

الرياضة

النقل والمواصلات

يعتمد النقل في المدينة أساسا على المترو ويوجد بالمدينة مطار دولي والنقل النهرى لا يستخدم الا لأغراض سياحية.

معرض الصور

المدن الشقيقة

انظر أيضا

المصادر

- ^ Oleh Repan. The origins of Dnipro, the city and its name Archived 15 مارس 2022 at the Wayback Machine. The Ukrainian Week. July 2017 (page 46)

- ^ أ ب Результати 2 туру виборів у Дніпрі: розгромна перемога Філатова [Results of the 2nd round of elections in Dnipro: a devastating victory for Filatov]. 24 Kanal (in الأوكرانية). 24 November 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ The number of the available population of Ukraine as of January 1, 2022, https://ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/kat_u/2022/zb/05/zb_%D0%A1huselnist.pdf

- ^ Чисельність населення на 1 липня 2011 року, та середня за січень–червень 2011 року [Population as of 1 July 2011, and the average for January – June 2011]. Department of Statistics in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (in الأوكرانية). Archived from the original on 20 October 2013.

- ^ Общие сведения и статистика [General information and statistics]. gorod.dp.ua (in الروسية). Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Ukrcensus.gov.ua — City Archived 9 يناير 2006 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed on 8 March 2007

- ^ "Official statistics, 01.08.2012 (Ukrainian)". Dneprstat.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ "Coordinates + Total Distance". MapCrow. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ "Днепровская городская громада" (in Russian). Портал об'єднаних громад України.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةCybriwsky History of the Dnipro - ^ أ ب Sullivan, Becky (29 March 2022). "With front lines on 3 sides, Ukraine's Dnipro sharpens its focus on the war". NPR.org (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ "Dispatch from Dnipro How 'Ukraine's outpost' and its people are faring after one year of all-out war". Meduza. February 23, 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةdnipropetrovshina-istorichna-dovidka - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةukrssr2 - ^ "English map of 1820" (JPG). Arhivtime.ru. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Проект Закону про внесення змін до статті 133 Конституції України (щодо перейменування Дніпропетровської області), Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, 27 April 2018, Number 8329 of the 8th session of the VIII convocation, http://w1.c1.rada.gov.ua/pls/zweb2/webproc4_1?pf3511=63949, retrieved on 28 April 2018 Пояснювальна записка 27.04.2018, http://w1.c1.rada.gov.ua/pls/zweb2/webproc34?id=&pf3511=63949&pf35401=453959

- ^ "Heohrafichni nazvy" [Geographical names]. Ukrainskyi pravopys [Ukrainian Orthography] (PDF) (in الأوكرانية) (1st ed.). Kharkiv: Ukrainian State Publisher, USRR National Commissariat of Education. 1929. p. 76.

Назви міст кінчаються на -ське, -цьке (а не -ськ, -цьк) [Names of cities end in -ske, -tske (and not -sk, -tsk)]

- ^ There is some confusion concerning the date of this map. حسب الصورة الخريطة رسمها شوبرت وتعود إلى حوالي عام 1860. إلا أن ويكيبيديا الاوكرانية تدعي أنه يعود إلى 1885. As the map does not show the railway bridge that was completed in 1884, 1860 seems a more likely date.

- ^ أ ب Вт, 12 марта 201307:51 (14 September 2011). "Ломоносову М.В., памятник – Днепропетровск". Gorod.dp.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Taylor, Philip S., Anton Rubinstein: A Life in Music, Indianapolis, 2007

- ^ Riga, Liliana (2012). The Bolsheviks and the Russian Empire (in الإنجليزية). Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-1107014220.

- ^ Klier, John Doyle; Lambroza, Shlomo (1992). Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History (in الإنجليزية). Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-521-52851-1.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Goldbrot, I. (1972). "The Jews in Ekaterinoslav–Dniepropetrovsk (Pages 21–40)". www.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ Surh, Gerald (2003). "Ekaterinoslav City in 1905: Workers, Jews, and Violence". International Labor and Working-Class History (64): 139–166. ISSN 0147-5479. JSTOR 27672887.

- ^ (in أوكرانية) Dnipropetrovsk region. Pragmatic area, The Ukrainian Week (8 May 2014)

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ I. S. Storazhenko (2001). "The city of Katerinoslav in 1917–1920". gorod.dp.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 26 October 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Oliver Henry Radkey (1989). Russia goes to the polls: the election to the all-Russian Constituent Assembly, 1917. Cornell University Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 978-0-8014-2360-4.

- ^ Mawdsley, Evan (2007). The Russian Civil War. Pegasus Books. p. 35. ISBN 9781933648156.

- ^ Skirda, Alexandre (2004). Nestor Makhno–Anarchy's Cossack: The Struggle for Free Soviets in the Ukraine 1917–1921 (in الإنجليزية). Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Oakland, CA: AK Press. ISBN 1-902593-68-5. OCLC 60602979. (page 77)

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 213; Skirda 2004, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 77.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص I. S. Storazhenko (2001). "Dnipropetrovsk in the 1920s and 1930s". gorod.dp.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2 November 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Roman Serb. "Photos about Ukrainian Hunger 1921–1923". Ukrainian life in Sevastopol (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2 November 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ L.M. Markova. "About the renaming of streets in the city of Katerynoslava – Dnipropetrovsk in the 1920s and 1930s". gorod.dp.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 16 October 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب Ukraine tears down controversial statue, by Rostyslav Khotin, BBC News (27 November 2009)

Same article on UNIAN. - ^ The Kravchenko Case: One Man's War Against Stalin by Gary Kern, Enigma Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1-929631-73-5, page 191

- ^ A, Erdogan (2021). Transcripts from the Soviet Archives Volume VII 1927 (in الإنجليزية). Erdogan A. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-329-49087-1.

- ^ Sergei, Zhuk (21 January 2022). "Communist Party Politics, Rockets and Komsomol Business in Soviet Dnipropetrovsk". E-International Relations (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ Boriak, Hennadii. 2009. Sources for the Study of the 'Great Famine' in Ukraine. Cambridge, MA.

- ^ أ ب Ihor Kocherhin. "Famine 1932–1933 in Dnipropetrovshchyna". gorod.dp.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2 November 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةcensus1926 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:1 - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "Historical and urban development reference Dnipropetrovsk". gorod.dp.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2 November 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Monument of 20000 Jews shot by Germans in 1943 in Dnipropetrovsk [Energetichna street], Ukraine". Wikimedia Commons. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "1941". MusicAndHistory. Archived from the original on 28 August 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "Onwar.com, Red Army crosses Dniepr River". Onwar.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, p. 372.

- ^ Harkavi, Zvi (1973). "Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine (Pages 89–104,107–110)". www.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ "Holocaust". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ "Memorial to the deceased prisoners of war of the Stammlager 348 and patients of the Psychiatric Hospital "Igren"". terraoblita.com (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ "Memorial Executed Prisoners of War - Dnipropetrovsk - TracesOfWar.com". www.tracesofwar.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 298, 349, 384. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ^ أ ب Miller, Christopher (28 October 2017). "Inside 'Satan's' Lair: The Lock-Tight Ukrainian Rocket Plant At Center Of Tech-Leak Scandal". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ أ ب Neringa Klumbyte; Gulnaz Sharafutdinova (2012). Soviet Society in the Era of Late Socialism, 1964–1985. Lexington Books. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7391-7584-2.

- ^ "Life and Death in Five Former Secret Soviet Cities". Balkanist (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 20 June 2014. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ Krawchenko, Bohdan (1993). "Strike". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 2022-08-10.

- ^ Teague, Elizabeth (1990). "Perestroika and the Soviet Worker". Government and Opposition. 25 (2): 191–211. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.1990.tb00755.x. ISSN 0017-257X. JSTOR 44482502. S2CID 140457991.

- ^ New York Times, 20 June 1990 Evolution in Europe; Soviet Troops Kill an Inmate During Riot in Ukrainian Jail This stated that TASS had issued a statement saying that there had been a riot by 2,000 inmates in a prison in Dnipropetrovsk. The riot broke out on Thursday 14 June 1990, and was quelled by Soviet troops on Friday 15 June 1990, killing one prisoner and wounding another.

- ^ أ ب (in أوكرانية) History of Ukraine. Standard level. Grade 11. Strukevich § 9. The state of culture during the period of de-Stalinization, History | Your library (2009–2022)

- ^ أ ب (in أوكرانية) There are almost 200 Russian-speaking secondary schools in Ukraine. By 2023, they should be translated into the Ukrainian language of instruction, Babel.ua (22 October 2019)

- ^ أ ب Krawchenko, Bohdan (1985). Social Change and National Consciousness in Twentieth-Century Ukraine (in الإنجليزية). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 186. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-09548-3. ISBN 978-0-333-44284-5.

- ^ Kuzio, Taras (23 June 2015). Ukraine: Democratization, Corruption, and the New Russian Imperialism: Democratization, Corruption, and the New Russian Imperialism. Abc-Clio. p. 34. ISBN 9781440835032.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz (2009). Nationalisms Across the Globe (volume 1). Peter Lang. p. 237. ISBN 978-3-03911-883-0.

- ^ Klumbytė, Neringa; Sharafutdinova, Gulnaz (2013). Soviet Society in the Era of Late Socialism, 1964–1985 (in الإنجليزية). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-7391-7583-5.

- ^ Neringa Klumbyte; Gulnaz Sharafutdinova (2012). Soviet Society in the Era of Late Socialism, 1964–1985. Lexington Books. p. 70/71. ISBN 978-0-7391-7584-2.

- ^ أ ب ت The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music and Social Class, ed. Ian Peddie, New York / London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, ISBN 9781501345364, page 318 + 319

- ^ Zhuk, Sergei (2022). KGB Operations against the USA and Canada in Soviet Ukraine, 1953–1991 (in الإنجليزية). Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 9781032080123.

- ^ Klumbytė, Neringa; Sharafutdinova, Gulnaz (2013). Soviet Society in the Era of Late Socialism, 1964–1985 (in الإنجليزية). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7391-7583-5.

- ^ أ ب Bacon, Edwin; Sandle, Mark (2002). Brezhnev reconsidered (in البريتونية). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire. ISBN 0-333-79463-X. OCLC 49894618.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ McCauley, Martin (1997). Who's who in Russia since 1900. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-13782-5. OCLC 51666665.

- ^ Klinke, Andreas; Renn, Ortwin; Lehners, Jean-Paul, eds. (2020). Ethnic Conflicts and Civil Society: Proposals for a New Era in Eastern Europe. Routledge. ISBN 9781138935525.

- ^ Why is Ukraine's economy in such a mess?, The Economist (5 Mar 2014)

- ^ Adam Swain (2012). Re-Constructing the Post-Soviet Industrial Region: The Donbas in Transition. Routledge. ISBN 9780415511193.

- ^ Lang, Thilo; Henn, Sebastian; Ehrlich, Kornelia; Sgibnev, Wladimir, eds. (2015). Understanding Geographies of Polarization and Peripheralization. Springer. ISBN 978-1137415073.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:5 - ^ "Losing Brains and Brawn: Outmigration from Ukraine | Wilson Center". www.wilsoncenter.org (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ "Case 92: Dnepropetrovsk Maniacs – Casefile: True Crime Podcast". Casefile: True Crime Podcast (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 11 August 2018. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ^ "Dnepropetrovsk Maniacs: Court delivers its verdicts" (in الروسية). Archived from the original on 12 February 2012.

- ^ "Bombs wound 27 in Ukrainian city". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). 27 April 2012. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ East Journal, 29 April 2012 (in إيطالية)

- ^ Dnipropetrovsk bombers wanted to frustrate Euro 2012 in Ukraine, says SBU, Kyiv Post (20 October 2012)

- ^ "В Днепропетровске больше трех тысяч человек собрались возле ОГА – Днепропетровск". Dp.vgorode.ua. 26 January 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Ukraine protests 'spread' into Russia-influenced east, BBC News (26 January 2014)

- ^ "EuroMaidan rallies in Ukraine (Jan. 24–27 live updates)". Kyiv Post. 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Восток и Юг Украины вышел пикетировать ОГА: в Запорожье стреляют в митингующих, а в Сумах просят подмоги (обновлено 2.34)". Delo UA. 27 January 2014. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2014.