خرسون

خرسون

Херсон | |

|---|---|

| الإحداثيات: 46°38′0″N 32°35′0″E / 46.63333°N 32.58333°E | |

| بلد | |

| أوبلاست | |

| رايونات مدينة | رايون خرسون رايون دنپروڤسكي رايون سوفوروڤسكي رايون كومسومولسكي |

| Founded | 18 يونيو 1778 |

| الحكومة | |

| • عمدة | إيهور كوليخايڤ[1] (علينا أن نعيش هنا[1]) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 135٫7 كم² (52٫4 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 46٫6 m (152٫9 ft) |

| التعداد (2021) | |

| • الإجمالي | |

| الرمز البريدي | 73000 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +380 552 |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | city |

خرسون (أوكرانية: Херсо́н، uk-Херсон.ogg [xerˈsɔn]، إنگليزية: Kherson)، هي مدينة-ميناء في أوكرانيا والمركز الإداري لأوبلاست خرسون. تطل على البحر الأسود ونهر الدنيپر، وتشتهر بكونها مركزاً هاماً لصناعة بناء السفن في المنطقة.[2] في مطلع 2022 كان عدد سكانها 279.131 نسمة.[2]

من مارس حتى نوفمبر 2022، احتلت القوات الروسية المدينة أثناء غزوها لأوكرانيا. استعادت القوات الأوكرانية المدينة في 11 نوفمبر 2022. وفي يونيو 2023، غمرت المياه المدينة بعد تدمير سد كاخوڤكا القريب.[3]

أصل الاسم

سميت على اسم المدينة-المستعمرة الأكثر شهرة خرسونسوس، الواقعة في شبه جزيرة القرم، كأول مدينة من المشروع اليوناني لگريگوري پوتمكين وكاثرين الثانية. الاسم القديم خرسونسى مشتق من الكلمة اليونانية القديمة خرسونسوس والتي تعني شبه الجزيرة، الشاطئ.[4][5] لكن النسخة البيزنطية، التي ظهرت لأول مرة في أيام الإمبراطور زينون، كانت تستخدم للاسم.

التاريخ

Beginning of 1917–1921 Revolution

![]() الحكومة الروسية المؤقتة/الجمهورية الروسية مارس-نوفمبر 1917

الحكومة الروسية المؤقتة/الجمهورية الروسية مارس-نوفمبر 1917

![]() أوكرانيا الاشتراكية نوفمبر 1917–يناير 1918

أوكرانيا الاشتراكية نوفمبر 1917–يناير 1918

![]() أوكرانيا السوڤيتية Jan–Apr 1918

أوكرانيا السوڤيتية Jan–Apr 1918

![]() أوكرانيا الشعبية/الدولة الأوكرانية أبريل 1918–يناير 1919

أوكرانيا الشعبية/الدولة الأوكرانية أبريل 1918–يناير 1919

![]() تدخل جنوب روسيا يناير-مارس 1919

تدخل جنوب روسيا يناير-مارس 1919

![]() UkSSR مارس-مايو 1919

UkSSR مارس-مايو 1919

![]() بوروتبيتس مايو-يوليو 1919

بوروتبيتس مايو-يوليو 1919

![]() UkSSR يوليو 1919

UkSSR يوليو 1919

![]() ARSR يوليو 1919–أبريل 1920

ARSR يوليو 1919–أبريل 1920

![]() أوكرانيا الاشتراكية السوڤيتية أبريل 1920–ديسمبر 1922

أوكرانيا الاشتراكية السوڤيتية أبريل 1920–ديسمبر 1922

نهاية ثورة 1917–1921

![]() الاتحاد السوڤيتي 1922–1941

الاتحاد السوڤيتي 1922–1941

![]() الرايخ الثالث 1941–1944

الرايخ الثالث 1941–1944

![]() الاتحاد السوڤيتي 1944–1991

الاتحاد السوڤيتي 1944–1991

![]() أوكرانيا 1991–2022

أوكرانيا 1991–2022

![]() روسيا مارس-نوفمبر 2022

روسيا مارس-نوفمبر 2022

الأيام المبكرة وفترة الامبراطورية الروسية (حتى 1917)

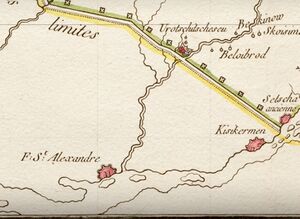

Before 1774, the area where Kherson is situated today belonged to the Crimean Khanate. A German-language map in 1736 (inset) shows a settlement of Bilschowscei at the site of today's Kherson. A French-language map of the site in 1769 (inset) shows a Russian-built fort or sconce named St. Alexandre. This had been built in 1737 during the Russo-Turkish War and served the Zaporizhian Sich as an administrative center, run by local Cossacks.

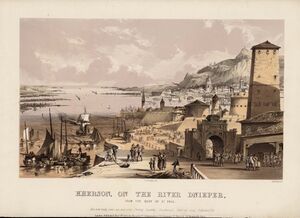

The Russian Empire annexed the territory in 1774, and a decree of Catherine the Great on 18 June 1778 founded Kherson on the high bank of the Dnieper as a central fortress of the Black Sea Fleet.

1783 saw the city granted the rights of a district town and the opening of a local shipyard where the hulls of the Russian Black Sea fleet were laid. Within a year the Kherson Shipping Company began operations. By the end of the 18th century, the port had established trade with France, Italy, Spain and other European countries. Between 1783 and 1793 Poland's maritime trade via the Black Sea was conducted through Kherson by the Kompania Handlowa Polska. In 1791, Potemkin was buried in the newly built St. Catherine's Cathedral. In 1803 the city became the capital of the Kherson Governorate.[2]

Industry, beginning with breweries, tanneries and other food and agricultural processing, developed from the 1850s.[بحاجة لمصدر] In 1897 the population of the city was 59,076 of which, on the basis of their first language, almost half were recorded as Great Russian, 30% as Jewish, and 20% Ukrainian.[6] During the revolution of 1905 there were workers' strikes and an army mutiny (an armed demonstration by soldiers of the 10th Disciplinary Battalion) in the city.[7]

الفترة السوڤيتية (1917–1991)

الفترة البلشڤية المبكرة

In the Russian Constituent Assembly election held in November 1917—the first and last free election in Kherson for 70 years—Bolsheviks who had seized power in Petrograd and Moscow received just 13.2 percent of the vote in the Governorate. The largest electoral bloc in the district, with 43 percent of the vote, was an alliance of Ukrainian Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs), Russian Socialist Revolutionaries and the United Jewish Socialist Workers Party.[8]

The Bolsheviks dissolved SR-dominated Assembly after its first sitting,[9] and proceeded to force from Kiev the Central Council of Ukraine (Tsentralna Rada) whose response to the Leninist coup had been to proclaim the independence of the Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR). But, before the Bolsheviks could secure Kherson, they were obliged to cede the region under the terms of the March 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk to the German and Austrian controlled Ukrainian State. After the withdrawal of German and Austrian forces in November 1918, the efforts of the UPR (the Petluirites) to assert authority were frustrated by a French-led Allied intervention which occupied Kherson in January 1919.[10]

In March 1919, the Green Army of local warlord Otaman Nykyfor Hryhoriv ousted the French and Greek garrison and precipitated the Allied evacuation from Odesa. In July, the Bolsheviks defeated Hryhoriv who had called upon the Ukrainian people to rise against the "Communist impostors" and their "Jewish commissars",[11] and had perpetrated pogroms,[11] including in the Kherson region.[12] Kherson itself was occupied by the counter-revolutionary Whites before finally falling to the Bolshevik Red Army in February 1920.[2] In 1922 the city and region was formally incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR a constituent republic of the Soviet Union.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The population was radically reduced from 75,000 to 41,000 by the famine of 1921–23, but then rose steadily, reaching 97,200 in 1939.[13] In 1940, the city was one of the sites of executions of Polish officers and intelligentsia committed by the Soviets as part of the Katyn massacre.[14]

الحرب العالمية الثانية وفترة بين الحربين

Further devastation and population loss resulted from the German occupation during the Second World War. The German occupation, which lasted from August 1941 to March 1944, contended with both Soviet and Ukrainian nationalist (OUN) underground cells. The Kherson district leadership of the OUN was headed by Bohdan Bandera (brother of OUN leader Stepan Bandera).[15] The Germans operated a Nazi prison and the Stalag 370 prisoner-of-war camp in the city.[16][17]

In the post-war decades, which saw substantial industrial growth, the population more than doubled, reaching 261,000 by 1970.[18] The new factories, including the Comintern Shipbuilding and Repairs Complex, the Kuibyshev Ship Repair Complex, and the Kherson Cotton Textile Manufacturing Complex (one of the largest textile plants in the Soviet Union), and Kherson's growing grain-exporting port, drew in labour from the Ukrainian countryside. This changed the city's ethnic composition, increasing the Ukrainian share from 36% in 1926 to 63% in 1959, while reducing the Russian share from 36 to 29%. The Jewish population never recovered from the Holocaust visited by the Germans: accounting for 26% of residents in 1926, their number had fallen to just 6% in 1959.[18]

أوكرانيا المستقلة

With a turnout of 83.4% of eligible voters, 90.1% of the votes cast in Kherson Oblast affirmed Ukrainian independence in the national referendum of 1 December 1991.[19] With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kherson and its industries experienced severe dislocation. Over the following three decades, the population of both the city and the region declined, reflecting both a significant excess of deaths over live births and persistent net-emigration from the area.[20][21]

The 2014 pro-Russian unrest in eastern and southern Ukraine was marked in Kherson by a small demonstration of some 400 persons.[22] Following Russian occupation of Crimea in 2014, Kherson housed the office of the Ukrainian President's representative in Crimea.[23]

In July 2020, as part of the general administrative reform of Ukraine, the Kherson Municipality was merged as Kherson urban hromada into newly established Kherson Raion, one of five raions in the Kherson Oblast of which the city remained the administrative centre.[24][25]

A "City Profile", part of the SCORE (Social Cohesion and Reconciliation)[26] Ukraine 2021 project funded by USAID, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the European Union, concluded that "more than 80% of citizens in Kherson city feel their locality is a good place to live, work, and raise a family". This was despite a low level of trust in the local authorities in whom corruption was perceived to be high. It also found that, while more inclined to express support for co-operation with Russia than for membership of the EU, "citizens in Kherson feel attached to their Ukrainian identity".[27]

الانتخابات المحلية 2020

In the last free elections before the 2022 Russian invasion, the Ukrainian local elections held on 25 October 2020, the results of Kherson City Council elections were as follows:[28]

| Party | Percentage of vote | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| We have to live here! | 23.1% | 17 seats |

| Opposition Platform – For Life | 14.5% | 11 seats |

| Servant of the People | 13.0% | 10 seats |

| Volodymyr Saldo Bloc | 11.8% | 9 seats |

| European Solidarity | 8.6% |

The parties widely perceived as pro-Russian, and Euro-skeptic,[29] Opposition Platform, Volodymyr Saldo Bloc, and Party of Shariy (3.9%) had a combined vote of just over 30% of the total, and secured 20 out of the 54 seats on the city council. In the wake of the invasion, the Opposition Platform and the Party of Shariy were banned by the National Security Council for alleged ties to the Kremlin.[30][31][32]

The Volodymyr Saldo Bloc dissolved; its deputies in Kyiv joined the newly formed faction "Support to the programs of the President of Ukraine".[33] From 26 April 2022, Volodymyr Saldo himself, who had been mayor of Kherson from 2002 to 2012, went on to serve the Russian occupiers, as head of the Kherson military–civilian administration.[34][35]

الغزو الروسي منذ فبراير 2022

في الأيام الأولى للغزو الروسي لأوكرانيا 2022 شهدت خرسون قتالاً عنيفاً في ما سُمي "هجوم خرسون".[36] واعتباراً من 2 مارس، وقعت المدينة تحت السيطرة الروسية.[37][38] وفي 8 مارس، ورد أنباء بأنه جرى تكليف جهاز الأمن الفيدرالي الروسي بالقضاء على ما تبقى من مقاومة أوكرانية فيها.[39] وخلال السيطرة الروسية شهدت المدينة بعد التحركات التي نظمها السكان المحليون ضد التواجد الروسي ودعماً لوحدة أوكرانيا.[40][41] وبحسب الحكومة الأوكرانية، سعت روسيا لتأسيس جمهورية خيرسون الشعبية، على غرار الأنظمة السياسية التي ظهرت في دونباس وضغط على الشخصيات المحلية العامة من أجل الحصول على دعمهم لهذا التوجه.[42]

وفي 26 أبريل 2022، اتممت القوات الروسية السيطرة على مقر المدينة وعينت ألكسندر كوبيتس عمدةً جديد لها،[43] كما عينت رئيس البلدية السابق فولوديمير سالدو كمسؤول إقليمي مدني عسكري.[44] وفي اليوم التالي، قال المدعي العام لأوكراني إن القوات الروسية استخدمت الغاز المسيل للدموع لتفريق مسيرة مؤيدة لأوكرانيا في المدينة.[43]وفي 28 أبريل أعلنت الإدارة الجديدة أن المدفوعات بمقاطعة خيرسون ستصبح الروبل الروسي اعتباراً من شهر مايو. وقال نائب رئيس إدارة مقاطعة خيرسون، كيريل ستريموسوف بأن "إعادة دمج منطقة خيرسون مرة أخرى في أوكرانيا النازية أمر غير وارد".[45]

وفي 30 سبتمبر 2022، اعلنت روسيا ضم أوبلاست خيرسون للاتحاد الروسي.[46] فيما أدانت الجمعية العامة للأمم المتحدة عمليات الضم بأغلبية 143 صوتاً مقابل 5.[47]

وفي 9 نوفمبر 2022 صدرت أوامر للقوات الروسية بالانسحاب من المدينة من قبل وزير الدفاع سيرغي شويغو وإعادة تنظيم القوات على الجانب الشرقي من نهر الدنيپر. فيما قال المسؤولون الأوكرانيون أن القوات الروسية دمرت الجسور التي تربط المدينة بالضفة الأخرى من النهر.[48][49]وفي 11 نوفمبر، أعلنت أوكرانيا أن قواتها دخلت المدينة بعد الانسحاب الروسي.[50][51]

وقبل انسحابه دمر الجيش الروسي مرافق البنية التحتية للمدينة بما في ذلك الاتصالات، ومياه، والتدفئة، والكهرباء، وبرج التلفزيون،[52][53]وقاموا بنقل مقتنيات المتحفين الرئيسيين فيها، متحف التاريخ المحلي، ومتحف خيرسون للفنون، إلى متاحف القرم،[54][55]بما فيها العديد من الآثار لشخصيات تاريخية.[56][57] في 23 أكتوبر 2023، انتهى التصويت عبر الإنترنت على إعادة تسمية العديد من الشوارع والمحليات في خيرسون لأغراض "إزالة الترويس" من المدينة. وذلك بعد أصدار أوكرانيا لقانون إدانة وحظر الدعاية للسياسة الإمبراطورية الروسية، وإنهاء الاسماء الاستعمارية للمواقع الجغرافية"، والذي يمنح المجالس المحلية ستة أشهر لإزالة أسماء المواقع الجغرافية التي تصنف بأنها إشكالية.[58]

ومع تمركز القوات الروسية على الجانب الآخر من نهر دنيبرو، بقيت المدينة عرضة لقصف متكرر.[59] وفي مطلع 2024، لم يكن بقي سوى 71 ألف نسمة فقط من سكان المدينة، التي كان تعدادهم قبل الحرب حوالي 300 ألف نسمة.[60]

الجغرافيا

المناخ

| أخفClimate data for خرسون (1991–2020، درجات الحرارة القصوى 1955–الحاضر) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

37.7 (99.9) |

39.5 (103.1) |

40.5 (104.9) |

40.7 (105.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

32.0 (89.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.2 (63.0) |

40.7 (105.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

16.1 (61.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.3 (37.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

0.4 (32.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.4 (24.1) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.5 (63.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

6.3 (43.3) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.3 (−15.3) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−16.2 (2.8) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−26.3 (−15.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33 (1.3) |

28 (1.1) |

30 (1.2) |

32 (1.3) |

43 (1.7) |

59 (2.3) |

44 (1.7) |

29 (1.1) |

38 (1.5) |

36 (1.4) |

34 (1.3) |

38 (1.5) |

444 (17.5) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 2 (0.8) |

3 (1.2) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

3 (1.2) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 114 |

| Average snowy days | 11 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 4 | 8 | 39 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.5 | 82.1 | 77.1 | 68.5 | 64.8 | 65.3 | 62.1 | 60.7 | 68.4 | 76.4 | 84.9 | 86.8 | 73.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 66 | 89 | 142 | 215 | 275 | 301 | 333 | 307 | 233 | 152 | 76 | 49 | 2٬238 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[61] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (humidity 1981–2010, sun 1991-2020)[62] [63] | |||||||||||||

الديموغرافيا

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

الانتماء العرقي

وفقا للتعداد الوطني الأوكراني (2001)، كانت المجموعات العرقية التي تعيش داخل خرسون كالتلي:

المجموعات العرقية التي تعيش في خرسون حسب تعداد عام 1926:

اللغات

| Languages | 1897[64] | 2001[65] |

|---|---|---|

| اللغة الأوكرانية | 19.6% | 53.4% |

| اللغة الروسية | 47.2% | 45.3% |

| اللغة اليديشية | 29.1% | |

| اللغة البولندية | 1.7% | |

| اللغة الألمانية | 0.7% |

التقسيمات الإدارية

يوجد ثلاثة رايونات في المدينة:

- رايون سوڤوروڤ، وسط وأقدم منطقة في المدينة، سميت على اسم الروس االجنرال سوڤوروڤ. يشمل القسم: كيج تاڤريجس وپيڤنيتشنيج و ميليني.

- رايون دنيپرو، على اسم نهر دنيپر. تشمل الأقسام: إتش بي كيه، سكلوتارا، سلوبيكدا، ڤوينكا، تكسيلني، سخيدني.

- رايون كورابلني . تشمل الأقسام: شومينسكي، كورابل، زابالكا، سوخارني، جيتلوسليششي، سليششي - 4، سيلششي - 5.

المناخ

تحت تصنيف كوپن للمناخ، خرسون لديها مناخ قاري رطب ("DFA").[66]

| أخفClimate data for خيرسون (1991-2020، أقصى 1955 إلى الوقت الحاضر) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

32.0 (89.6) |

37.7 (99.9) |

39.5 (103.1) |

40.5 (104.9) |

40.7 (105.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

32.0 (89.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.2 (63.0) |

40.7 (105.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

16.1 (61.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.3 (37.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

0.4 (32.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.4 (24.1) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.5 (63.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

6.3 (43.3) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.3 (−15.3) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−16.2 (2.8) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−26.3 (−15.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33 (1.3) |

28 (1.1) |

30 (1.2) |

32 (1.3) |

43 (1.7) |

59 (2.3) |

44 (1.7) |

29 (1.1) |

38 (1.5) |

36 (1.4) |

34 (1.3) |

38 (1.5) |

444 (17.5) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 2 (0.8) |

3 (1.2) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

3 (1.2) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 114 |

| Average snowy days | 11 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 4 | 8 | 39 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.5 | 82.1 | 77.1 | 68.5 | 64.8 | 65.3 | 62.1 | 60.7 | 68.4 | 76.4 | 84.9 | 86.8 | 73.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 63.7 | 82.7 | 134.2 | 193.3 | 275.8 | 294.7 | 318.5 | 301.5 | 228.4 | 153.8 | 77.6 | 50.1 | 2٬174٫3 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[61] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (humidity and sun 1981–2010)[62] | |||||||||||||

النقل

السكك الحديدية

ترتبط خرسون بشبكة السكك الحديدية الوطنية في أوكرانيا. توجد خدمات مسافات طويلة يومية إلى كييڤ، لڤيڤ ومدن أخرى.

الطيران

يخدم خرسون مطار خرسون الدولي. وهي تشغل مدرج خرساني يبلغ ارتفاعه 2500 × 42 متر، ويستوعب طائرات بوينگ 737 وطائرة إيرباص 319/320 وطائرات هليكوبتر من جميع السلاسل.

الموقع الرسمي للمطار هو https://khe.aero. ويمكن العثور على معلومات إضافية على http://www.aisukraine.net.

التعليم

هناك 77 مدرسة ثانوية بالإضافة إلى 5 كليات. هناك 15 مؤسسة للتعليم العالي.

- جامعة ولاية خرسون للزراعة

- جامعة ولاية خرسون

- جامعة خرسون التقنية الوطنية

- الجامعة الدولية للأعمال والقانون

تم تصوير الفيلم الوثائقي ديكسي لاند في مدرسة الموسيقى في خرسون.[67]

المناظر الرئيسية

- كنيسة سانت كاترين - بُنيت في ثمانينيات القرن الثامن عشر، من المفترض أن تلائم تصميمات إيڤان ستاروڤ وتحتوي على قبر الأمير پوتيمكين.

- المقبرة اليهودية - يوجد في خرسون جالية يهودية كبيرة تأسست في منتصف القرن التاسع عشر.[68] من عام 1959 حتى عام 1990 لم يكن هناك كنيس يهودي في خرسون. منذ ذلك الحين، نمت الحياة اليهودية وخرسون وتطورتا حقاً في جو من السلام.[69] ومع ذلك، عانت المقبرة اليهودية بانتظام من أعمال التخريب. وغطت القبور مرارا وتكرارا بالقمامة ودمرت شواهد القبور ودنست. في 6 أبريل 2012، حدث تخريب في المقبرة اليهودية في أحد أهم الأعياد في التقويم اليهودي، عيد الفصح. الحريق الذي تم إشعاله عمداً انتشر على الفور على مساحة حوالي 700 متر مربع وألحق أضراراً جسيمة بالقبور وشواهد القبور.[70]

- برج تلفزيون خرسون - مبنى مشهور يقع في المدينة.

- منارة Adziogol - هيكل مفرط الشكل صممه في جي شوخوڤ، 1911.

شخصيات بارزة

- جيورجي أرباتوڤ (1923-2010)، عالم سياسي.[71]

- ماكسيميليان برن، كاتب ومحرر

- سرجي بوندارتشوك، مخرج أفلام وكاتب سيناريو وممثل سوڤيتي أوكراني المولد

- لڤ داڤيدوڤيتش برونستين، والمعرف باسم ليون تروتسكي، وُلد الثوري البلشفي والمنظر الماركسي في قرية برسلاڤكا، محافظة خرسون عام 1879.

- إڤان إبراموڤيتش گانيبال (1735-1801)، مؤسس المدينة

- يفيم گولشڤ (1897-1970)، رسام ومؤلف موسيقي ارتبط بحركة دادا في برلين

- نيكولا گرينكو، ممثل أوكراني سوڤيتي

- كاترينا هاندزيوك، ناشط مدافع عن الحقوق المدنية ومناهض للفساد أوكراني (1985-2018)

- جون هاورد (توفى في خرسون 1790)

- ميرسيا إونسكو-كوينتوس، سياسي وكاتب وفقيه روماني

- پاڤلو إشتشونكو (و.1992) لاعب بوكس إسرائيلي أوكراني

- أولكساندر كاراڤايڤ، لاعب كرة قدم أوكراني

- إڤجني كوتشرڤسكي، مدرب كرة القدم الأوكراني لنادي دنيپرو دنيپروبتروڤسك

- لاريسا لاتينينا، لاعبة الجمباز السوفيتية التي كانت أول رياضية تفوز بتسع ميداليات ذهبية أولمبية

- تاتيانا ليسنكو، لاعبة گمباز سوڤيتية وأوكرانية فازت بميدالية ذهبية في عارضة التوازن في أولمبياد صيف 1992 في برشلونة.

- صموئيل مويسيڤيتش مايكاپار (1867-1938)، عازف بيانو

- سرجي پولونين، راقص باليه أوكراني[72]

- الأمير گريگوري پوتيمكين (1739-1791)، مؤسس المدينة

- سالومون روزنبلوم، الذي عُرف فيما بعد بالملازم سيدني رايلي، عميل سري ومغامر دولي وفتى مستهتر كان يعمل في وقت ما لدى البريطانيين المخابرات السرية. اشتهر بأنه مصدر إلهام لشخصية إيان فلمينگ الجاسوسية في فيلم جيمس بوند.

- موشيه شارت، رئيس وزراء إسرائيل الثاني (3195-1955)

- ٍسرجي ستانيشڤ، رئيس وزراء بلغاريا التاسع والاربعبن (سي)

- داڤيد تيشلر (1927-2014)، المبارز الحاصل على الميدالية البرونزية في الألعاب الأولمبية الأوكرانية / السوڤيتية

- ميخائيل يمتسڤ، كاتب خيال علمي

- نيكولاس پري (1992-)، شخصية معروفة على مواقع الواصل الاجتماعي وشهرته نيكوكادو أڤوكادو

المدن التوأم

مرئيات

| الجيش الروسي يدمر رتل دبابات أوكرانية بالقرب من خرسون، 24 فبراير 2022. |

المصادر

- ^ أ ب (in أوكرانية) The mayor of Kherson became the people's deputy majoritarian, Ukrayinska Pravda (16 November 2020)

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Херсон", Большая Советская Энциклопедия, том 46 (The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Vol. 46), Б. А. Введенский 2-е изд.(B. A. Vvedensky ed.. 2nd Edition). . М., Государственное научное издательство «Большая Советская энциклопедия» (State Scientific Publishing House), 1957, pp. 121–122

- ^ Sabbagh, Dan (2023-06-06). "As flood waters rise around them, Kherson residents cast blame for destroyed dam on 'inhumane' Moscow". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- ^ Янко М.Т. (1998). Топонімічний словник України: словник-довідник.

- ^ Лучик В.В. (2014). Етимологічний словник топонімів України.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly – Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Херсон // Советская историческая энциклопедия / редколл., гл. ред. Е. М. Жуков. том 15. М., государственное научное издательство «Советская энциклопедия», 1974. ("Kherson", Soviet Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 15, E. M. Zhukov. ed., State Scientific Publishing House), 1974. pp. 504–506, 571–573

- ^ Oliver Henry Radkey (1989). Russia goes to the polls: the election to the all-Russian Constituent Assembly, 1917. Cornell University Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 978-0-8014-2360-4.

- ^ Orlando Figes, A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924, London: Pimlico (1997), p. 516.

- ^ Akulov, Mikhail (18 October 2013). "War Without Fronts: Atamans and Commissars in Ukraine, 1917–1919" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2022 – via Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard.

- ^ أ ب Werth, Nicolas (2019). "Chap. 5: 1918–1921. Les pogroms des guerres civiles russes". Le cimetière de l'espérance. Essais sur l'histoire de l'Union soviétique (1914–1991) [Cemetery of Hope. Essays on the History of the Soviet Union (1914–1991)]. Collection Tempus (in الفرنسية). Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-07879-9.

- ^ Danilenko, Vladimir (2006). Jewish Pogroms in Ukraine, 1918–1921. Fond FR-3050 Kiev District Commission of the Jewish Public Committee for the Provision of Aid to Victims of Pogroms; Opis' 1–3 (PDF). Kyiv: The State Archive of the Kyiv Oblast. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ أ ب "Kherson". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ Zbrodnia katyńska (in البولندية). Warszawa: IPN. 2020. p. 17. ISBN 978-83-8098-825-5.

- ^ Владимир Ковальчук. Богдан – загадочный брат Степана Бандеры Газета «День», No. 30, 20 февраля 2009 года. // day.kyiv.ua ("Vladimir Kovalchuk. Bogdan is Stepan Bandera's mysterious brother", The Day, No. 30, 20 February 2009. // day.kyiv.ua)

- ^ "Gefängnis Cherson". Bundesarchiv.de (in الألمانية). Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ "German Camps". Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ أ ب "Kherson". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian Independence Referendum". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 28 September 2015. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "На Херсонщині демографічна ситуація загострюється: на 100 померлих – 38 новонароджених". Херсонщина за день – новости Херсона и Херсонской области, Kherson News (in الروسية). Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ "На Херсонщині зменшується чисельність населення". khersonci.com.ua. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ "В Херсоне прошел пророссийский митинг". Liga.net. 1 March 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Official website Archived 3 مارس 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Presidential representative of Ukraine in Crimea.

- ^ "Про утворення та ліквідацію районів. Постанова Верховної Ради України № 807-ІХ". Голос України (in الأوكرانية). 18 July 2020. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "Нові райони: карти + склад" (in Ukrainian). Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України. 17 July 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Newton, Andrew. "SCORE Index". www.scoreforpeace.org. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ SCORE Eastern Ukraine 2021 (23 June 2022). "Kherson 2021, City Profile – Ukraine". ReliefWeb.int (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Kherson. City Council elections 25 October 2020. Results, Ukraine Elections". ukraine-elections.com.ua. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "Kennan Cable No. 45: Six Reasons the 'Opposition Platform' Won in Eastern Ukraine". www.wilsoncenter.org (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2021."The changing face of pro-Russian political forces in Ukraine". Uacrisis.org (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 9 July 2021. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ "Parliament dissolves pro-Russian Opposition Platform faction following Security Council ban". 14 April 2022. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "NSDC bans pro-Russian parties in Ukraine". Ukrinform. 20 March 2022. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ (in أوكرانية) Court bans Sharia Party Archived 26 يونيو 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrainska Pravda (16 June 2022)

- ^ "Депутати 'Блоку Сальдо' не згодні з діями Сальдо: написали лист керівництву Херсонської облради". Suspilne.media. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "Kherson mayor refuses to cooperate with collaborators and invaders". Ukrinform. 26 April 2022. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Российские оккупационные силы назначили своих 'руководителей' в Херсоне и области" [Russian occupation forces appoint their 'leaders' in Kherson and oblasts]. Crimea.Realities (in الروسية). 26 April 2022. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Fighting under way near Kherson, Mykolaiv, Odessa – Ukrainian official". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). 26 February 2022. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland (2 March 2022). "Vladimir Putin set to 'cut Ukraine in two' as key city of Kherson falls to Russians". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Kherson falls – Kyiv under fire – Mariupol tragedy". Politico.eu. 3 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine's military: As Russian invasion slows down, FSB goes after resistance in Kherson and Mykolaiv regions". The Kyiv Independent. 8 March 2022. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ "Crowds take to the streets of Kherson". BBC News (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 13 March 2022. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ Peterson, Scott; Naselenko, Oleksandr (6 April 2022). "Tear gas, arrogance, and resistance: Life in Russia-occupied Kherson". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Missing reporter among several journalists, activists and officials said to be detained by Russian forces" (in الإنجليزية). CNN. 19 March 2022. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ أ ب Prentice, Alessandra; Zinets, Natalia (27 April 2022). "Russian forces disperse pro-Ukraine rally, tighten control in occupied Kherson". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 8 May 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Russian-Occupied Kherson Names New Leadership Amid Pro-Ukraine Protests, Rocket Attacks". The Moscow Times (in الإنجليزية). 28 April 2022. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Vasilyeva, Nataliya (28 April 2022). "Occupied Kherson will switch to Russian currency, puppet government says". The Telegraph (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia-Ukraine war live: Putin annexes Ukrainian regions; Kyiv applies for Nato membership". TheGuardian.com. 30 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "UN General Assembly Condemns Russia's 'Illegal Annexation' Of Ukrainian Regions". rferl.org. 12 October 2022. Archived from the original on 9 November 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ Trevelyan, Mark (9 November 2022). "Russia abandons Ukrainian city of Kherson in major retreat". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 November 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-09 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "Russia orders retreat from Kherson, key city in southern Ukraine". NBC News. 9 November 2022. Archived from the original on 9 November 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ "Ukraine says its forces entering Kherson after Russian retreat". RTÉ News (in الإنجليزية). 11 November 2022. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Ukrainian forces enter Kherson after Russian retreat Archived 24 نوفمبر 2022 at the Wayback Machine, timesofisrael.com. Accessed 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Освобождение Херсона и другие события 261-го дня войны" (in الروسية). Deutsche Welle. 2022-11-11. Archived from the original on 2022-11-28.

- ^ "Возвращение. Как живет освобожденный Херсон" (in الروسية). Deutsche Welle. 2022-11-22. Archived from the original on 2022-12-03.

- ^ "Ukraine reports looting of Kherson museums by Russian troops". El Pais. 2022-11-17. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ "Russia to take over Ukrainian museum collections as formal annexation plans announced". The Art Newspaper. 2022-09-30. Archived from the original on 2022-11-14.

- ^ "'У нас будет бойня, мы готовы'. Кто остается в Херсоне и кто его покидает" (in الروسية). BBC. 2022-10-27. Archived from the original on 2022-11-19.

- ^ "В РФ заявили об атаке беспилотников на Черноморский флот и выходе из 'зерновой сделки'. 248-й день войны России против Украины. Онлайн RFI" (in الروسية). Radio France internationale. 2022-10-29. Archived from the original on 2022-10-30.

- ^ Гусаков, Вʼячеслав (2023-10-23). "Нові назви херсонських вулиць: що обрали учасники онлайн-голосування" (in الأوكرانية). Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ^ Nielson, Nikolaj (2024-02-01). "Kherson — a city under siege on Ukraine's 1,000km frontline". EUobserver (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ Bowman, Verity (2024-02-19). "Ukraine's greatest victory becomes another countless victim of Russia's war". The Telegraph (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ أ ب "Pogoda.ru.net" (in الروسية). May 2011. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2021. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "pogoda" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010" (XLS). National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived from the original (XLS) on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "WMOCLINO" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ "Kherson Climate Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 1 November 2023.[dead link]

- ^ Национальный состав населения городов (по языку) Archived 13 أغسطس 2015 at the Wayback Machine Всероссийская перепись населения 1897

- ^ Ukrainian census in Kherson Oblast. State Statistics Service.

- ^ Peel, M. C. and Finlayson, B. L. and McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 فبراير 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bondarchuk, Roman. "Dixie Land". Cineuropa. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ "KHERSON". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 22 سبتمبر 2012. Retrieved 19 أغسطس 2012.

- ^ Zalman, Nelson (24 فبراير 2009). "Anti-Semitic Incitement, Poor Economy Have Kherson's Jews Worried". Merkos L'Inyonei Chinuch. Archived from the original on 15 أكتوبر 2012. Retrieved 19 أغسطس 2012.

- ^ "Вандалы подпортили светлый еврейский праздник Песах". Bagnet.org. Archived from the original on 10 أبريل 2012. Retrieved 19 أغسطس 2012.

- ^ Levy, Clifford J. "Georgi A. Arbatov, a Bridge Between Cold War Superpowers, Is Dead at 87" Archived 6 فبراير 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 2 October 2010. Accessed 4 October 2010.

- ^ "Self-destructive dance superstar Sergei Polunin: 'Ukraine put me on a list of terrorists'". TheGuardian.com. 7 March 2019.

وصلات خارجية

- Pictures of Kherson

- Kherson city administration website (in أوكرانية)

- Kherson patriots (in أوكرانية)

- Kherson info&shopping (in روسية)

- Kherson Photos (in روسية)

- The murder of the Jews of Kherson during World War II, at Yad Vashem website.

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with أوكرانية-language sources (uk)

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- CS1 البولندية-language sources (pl)

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- CS1 الأوكرانية-language sources (uk)

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- Articles with dead external links from March 2024

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing أوكرانية-language text

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with روسية-language sources (ru)

- خرسون

- مدن أوبلاست خرسون

- Port cities and towns in Ukraine

- موانئ البحر الأسود

- مدن ذات حيثية إقليمية في أوكرانيا

- Populated places on the Dnieper in Ukraine

- Oblast centers in Ukraine

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في 1778

- تأسيسات 1778 في الامبراطورية الروسية

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في الامبراطورية الروسية

- خرسونسكي أويزد

- مواقع المحرقة في أوكرانيا