الحرب الأوكرانية الروسية

| الحرب الروسية الأوكرانية | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من نزاعات ما بعد الاتحاد السوڤيتي | |||||||||

الوضع العسكري في فبراير 2022 تسيطر عليها أوكرانيا تسيطر عليها روسيا والقوات الموالية لروسيا للحصول على خريطة أكثر تفصيلاً، راجع Russo-Ukrainian War detailed map | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||||

|

|

In DNR (Donetskaya Narodnaya Respublika, see DPR) (since 2018) (August–September 2018) (2014–2018) (May–August 2014) In LNR (see LPR) (since 2017) (2014–2017) (May–August 2014) | ||||||||

| الوحدات المشاركة | |||||||||

|

وزارة الشؤون الداخلية (عنصر عسكري)

الوحدات المتطوعة

|

Airborne Troops[41][42][43][38] | ||||||||

| القوى | |||||||||

|

|

من بين هؤلاء، تم تأكيد 28000 في شبه جزيرة القرم، و3000 تم الإبلاغ عنها في دونباس ونفتها روسيا حتى 22 فبراير 2022.[53]

| ||||||||

| For details, see Combatants of the war in Donbas | |||||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||||

|

4,619 killed[54][55] |

5,768 killed[*][56][63] 12,700–13,700 wounded[56] | ||||||||

|

3,393 civilians killed;[64] 7,000–9,000 wounded[56] 13,100–13,300 killed; 29,500–33,500 wounded overall[56] 6 killed in Crimea (3 civilians)[65] | |||||||||

| [[#ref_killed{{{3}}}|^]] Includes 400–500 Russian servicemen (US claim, March 2015)[66] | |||||||||

| الحرب الأوكرانية الروسية |

|---|

|

| الموضوعات الرئيسية |

| موضوعات رئيسية |

| موضوعات متعلقة |

الحرب الأوكرانية الروسية Russo-Ukrainian War[67] (أوكرانية: російсько-українська війна, romanized: rosiysko-ukrainska viyna) وهي صراع مستمر وطويل الأمد بدأ في فبراير 2014، وتشارك فيه بشكل أساسي روسيا والقوات الموالية لروسيا من ناحية، وأوكرانيا من ناحية أخرى. تركزت الحرب على وضع القرم وأجزاء من دونباس، المعترف بها دولياً كجزء من أوكرانيا. واندلعت التوترات بين روسيا وأوكرانيا بشكل خاص من 2021 إلى 2022، عندما أصبح واضحاً أن روسيا كانت تفكر في شن غزو عسكري لأوكرانيا. في فبراير 2022، تعمقت الأزمة مع فشل المحادثات الدبلوماسية مع روسيا وتصاعدت مع تحرك روسيا لقواتها في المناطق التي يسيطر عليها الانفصاليون في 22 فبراير 2022.[68][69][70] في 24 فبراير، بدأت روسيا غزوها الشامل لأوكرانيا.[71][72][73]

في أعقاب احتجاجات يورو ميدان و الإزالة اللاحقة للرئيس الأوكراني ڤيكتور يانوكوڤيتش في 22 فبراير 2014، ووسط الاضطرابات الموالية لروسيا في أوكرانيا، الجنود الروس بدون شارات سيطروا على المواقع الإستراتيجية والبنية التحتية داخل إقليم القرم الأوكراني. في 1 مارس 2014، اعتمد مجلس الاتحاد الروسي بالإجماع قراراً لتقديم التماس الرئيس الروسي ڤلاديمير پوتن لاستخدام القوة العسكرية في أوكرانيا.[74] تم تبني القرار بعد عدة أيام، بعد بدء العملية العسكرية الروسية على "عودة شبه جزيرة القرم". ثم ضم شبه جزيرة القرم بعد انتقاد واسع النطاق لاستفتاء محلي نظمته روسيا بعد الاستيلاء على شبه جزيرة القرم البرلمان الذي كانت نتيجته انضمام جمهورية القرم ذات الحكم الذاتي إلى الاتحاد الروسي.[75][76][77][78] في أبريل، تصاعدت مظاهرات الجماعات الموالية لروسيا في منطقة دونباس بأوكرانيا إلى حرب بين الحكومة الأوكرانية والقوات الانفصالية المدعومة من روسيا في دونيتسك وجمهورية لوهانسك الشعبية. في أغسطس، عبرت المركبات العسكرية الروسية الحدود في عدة مواقع في أوبلاست دونيتسك.[39][79][80][81][82] اعتبر توغل الجيش الروسي مسؤولاً عن هزيمة القوات الأوكرانية في أوائل سبتمبر.[83][84]

في نوفمبر 2014، أبلغ الجيش الأوكراني عن تحرك مكثف للقوات والمعدات من روسيا إلى الأجزاء التي يسيطر عليها الانفصاليون في شرق أوكرانيا.[85] أفادت وكالة أسوشيتد پرس أن 40 مركبة عسكرية لا تحمل أية علامات كانت تتحرك في المناطق التي يسيطر عليها المتمردون.[86] لاحظت منظمة الأمن والتعاون في اوروپا (OSCE) بعثة المراقبة الخاصة قوافل من الأسلحة الثقيلة والدبابات في الأراضي التي تسيطر عليها جمهورية دونيتسك الشعبية دون شارات.[87]كما ذكر مراقبو منظمة الأمن والتعاون في أوروبا أنهم لاحظوا مركبات تنقل الذخيرة و الجثث الجنود تعبر الحدود الروسية الأوكرانية تحت ستار قوافل المساعدات الإنسانية.[88] اعتباراً من أوائل أغسطس 2015، لاحظت منظمة الأمن والتعاون في أوروبا أكثر من 21 مركبة من هذا القبيل تحمل الرمز العسكري الروسي للجنود الذين قتلوا في المعركة.[89]وبحسب موقع موسكو تايمز، حاولت روسيا ترهيب وإسكات العاملين في مجال حقوق الإنسان الذين يناقشون مقتل جنود روس في النزاع.[90]وقد أفادت منظمة الأمن والتعاون في أوروبا أن مراقبيها مُنعوا من الوصول إلى المناطق التي تسيطر عليها "القوات الانفصالية الروسية المشتركة".[91]

أدان غالبية أعضاء المجتمع الدولي[92][93][94]ومنظمات مثل منظمة العفو الدولية[95]أدانوا روسيا لأفعالها في أوكرانيا ما بعد الثورة، متهمين إياها بخرق القانون الدولي وانتهاك السيادة الأوكرانية. كما نفذت دول عديدة عقوبات اقتصادية ضد روسيا أو أفراد أو شركات روسية.[96]

في أكتوبر 2015، أفادت صحيفة واشنطن پوست أن روسيا أعادت نشر بعض وحدات النخبة من أوكرانيا إلى سوريا لدعم الرئيس السوري بشار الأسد.[97] في ديسمبر 2015، اعترف رئيس الاتحاد الروسي ڤلاديمير پوتن بأن ضباط المخابرات العسكرية الروسية كانوا يعملون في أوكرانيا، وأصر على أنهم ليسوا مثل القوات النظامية.[98]في فبراير 2019، صنفت الحكومة الأوكرانية 7٪ من أراضي أوكرانيا على أنها الأراضي المحتلة مؤقتاً.[99]

في 24 فبراير 2022، بدأت روسيا غزوها لأوكرانيا.[100][101]

خلفية

نقل رئيس الوزراء السوڤيتي نيكيتا خروشوڤ شبه جزيرة القرم، التي كانت موطناً لأسطول البحر الأسود الروسي/السوفيتي،[102] من جمهورية روسيا الاشتراكية الاتحادية السوڤيتية إلى جمهورية أوكرانيا الاشتراكية السوڤيتية في عام 1954. واعتبر هذا الحدث "لفتة رمزية" غير ذات أهمية، حيث كانت كلا الجمهوريتين جزءاً من الاتحاد السوڤيتي ومسؤول أمام الحكومة في موسكو.[103][104][105] أُعيد الحكم الذاتي لشبه جزيرة القرم في عام 1991 بعد استفتاء، قبل تفكك الاتحاد السوڤيتي مباشرة.[106]

على الرغم من كونها دولة مستقلة منذ عام 1991، باعتبارها جمهورية سوڤيتية سابقة، فإن أوكرانيا كانت تعتبر جزءاً من مجال نفوذها. يدعي يوليان تشيفو ورفاقه أنه فيما يتعلق بأوكرانيا، إن روسيا تتبع نسخة حديثة من مبدأ بريزنيڤ بشأن "السيادة المحدودة"، والتي تنص على أن سيادة أوكرانيا لا يمكن أن تكون أكبر من سيادة حلف وارسو قبل زوال مجال النفوذ السوفيتي.[107]ويستند هذا الادعاء إلى تصريحات القادة الروس بأن احتمال اندماج أوكرانيا في الناتو من شأنه أن يعرض الأمن القومي لروسيا للخطر.[108][109][107]

بعد حل الاتحاد السوڤيتي في عام 1991، استمرت كل من أوكرانيا وروسيا في الحفاظ على علاقات وثيقة لعقود. في الوقت نفسه، كانت هناك عدة نقاط شائكة، أهمها الترسانة النووية المهمة لأوكرانيا، والتي وافقت أوكرانيا على التخلي عنها في مذكرة بودابست للضمانات الأمنية (ديسمبر 1994) بشرط أن روسيا (والأطراف الأخرى الموقعة) ستصدر ضماناً ضد التهديدات أو استخدام القوة ضد وحدة أراضي أوكرانيا أو استقلالها السياسي. في عام 1999، كانت روسيا واحدة من الدول الموقعة على ميثاق الأمن الأوروبي، حيث "أعادت التأكيد على الحق الطبيعي لكل دولة مشاركة في أن تكون حرة في اختيار أو تغيير ترتيباتها الأمنية، بما في ذلك معاهدات التحالف، أثناء تطورها".[110]

النقطة الثانية كانت تقسيم أسطول البحر الأسود. وافقت أوكرانيا على استئجار عدد من المنشآت البحرية بما في ذلك تلك الموجودة في سڤاستوپول بحيث يستمر أسطول البحر الأسود الروسي في التمركز هناك جنباً إلى جنب مع القوات البحرية الأوكرانية. ابتداءً من عام 1993، خلال التسعينيات والعقد الأول من القرن الحادي والعشرين، انخرطت أوكرانيا وروسيا في العديد من نزاعات الغاز.[111]في عام 2001، شكلت أوكرانيا، جنباً إلى جنب مع جورجيا وأذربيجان ومولدوفا، مجموعة تسمى منظمة گوام للتطوير الديمقراطي والاقتصادي، والتي اعتبرتها روسيا تحدياً مباشراً لرابطة الدول المستقلة، وهي مجموعة تجارية تهيمن عليها روسيا تأسست بعد انهيار الاتحاد السوڤيتي.[112]كانت روسيا أكثر انزعاجاً من الثورة البرتقالية لعام 2004، والتي شهدت انتخاب الرئيس الموالي لأوروبا ڤيكتور يوشينكو بدلاً من الموالي لروسيا[113] علاوة على ذلك، واصلت أوكرانيا زيادة تعاونها مع حلف الناتو، ونشرت ثالث أكبر مجموعة من القوات في العراق في عام 2004، فضلاً عن تكريس قوات حفظ السلام لمهام الناتو مثل إيساف في أفغانستان و KFOR في كوسوڤو.

انتخب رئيس موال لروسيا، ڤيكتور يانوكوڤيتش، في عام 2010 وشعرت روسيا أنه يمكن إصلاح العديد من العلاقات مع أوكرانيا. قبل ذلك، لم تجدد أوكرانيا عقد إيجار المنشآت البحرية في شبه جزيرة القرم، مما يعني أن القوات الروسية ستضطر إلى مغادرة شبه جزيرة القرم بحلول عام 2017. ومع ذلك، وقع يانوكوڤيتش عقد إيجار جديد وقام بتوسيع وجود القوات المسموح به وكذلك السماح للقوات بالتدريب في شبه جزيرة كرچ.[114]اعتبر الكثيرون في أوكرانيا التمديد غير دستوري لأن الدستور الأوكراني ينص على عدم وجود قوات أجنبية دائمة في أوكرانيا بعد انتهاء معاهدة سڤاستوپول. سُجنت يوليا تيموشنكو، الشخصية المعارضة الرئيسية ليانوكوڤيتش، بتهم دعت بها للاضطهاد السياسي من قبل المراقبين الدوليين، مما أدى إلى مزيد من عدم الرضا عن الحكومة. في نوفمبر 2013، رفض ڤيكتور يانوكوڤيتش التوقيع على اتفاقية شراكة مع الاتحاد الأوروبي، وهي معاهدة كانت قيد التطوير لعدة سنوات وواحدة وافق عليها ڤيكتور يانوكوڤيتش في وقت سابق.[115]وبدلاً من ذلك فضل يانوكوڤيتش توثيق العلاقات مع روسيا.

في سبتمبر 2013، حذرت روسيا من أنه إذا مضت أوكرانيا قدماً في اتفاقية التجارة الحرة المخطط لها مع الاتحاد الاوروبي، فإنها ستواجه كارثة مالية وربما انهيار الدولة.[116]قال سرگي گلازييڤ، مستشار الرئيس ڤلاديمير پوتين، "السلطات الأوكرانية ترتكب خطأً فادحاً إذا اعتقدت أن رد الفعل الروسي سيصبح محايداً في غضون سنوات قليلة من الآن. وهذا لن يحدث". كانت روسيا قد فرضت بالفعل قيوداً على استيراد بعض المنتجات الأوكرانية ولم يستبعد گلازييڤ فرض مزيد من العقوبات إذا تم توقيع الاتفاقية. سمح گلازييڤ بإمكانية ظهور حركات انفصالية في شرق وجنوب أوكرانيا الناطق بالروسية. وأصر على أنه إذا وقعت أوكرانيا على الاتفاقية، فسوف تنتهك المعاهدة الثنائية بشأن الشراكة الاستراتيجية والصداقة مع روسيا التي ترسيم حدود الدول. لن تضمن روسيا بعد الآن وضع أوكرانيا كدولة ويمكن أن تتدخل إذا ناشدت المناطق الموالية لروسيا روسيا مباشرة.[116]

يورو ميدان ومكافحة الميدان

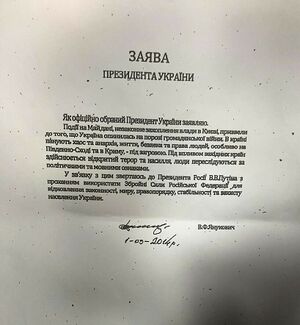

بعد أشهر من الاحتجاجات كجزء من حركة يورو ميدان، وقع يانوكوڤيتش وزعماء المعارضة البرلمانية في 21 فبراير 2014 على اتفاقية التسوية التي دعت إلى إجراء انتخابات مبكرة. في اليوم التالي، فر يانوكوڤيتش من العاصمة قبل التصويت على الإقالة التي جردته من سلطاته كرئيس.[117][118][119][120] في 27 فبراير، تم تشكيل حكومة مؤقتة وكان من المقرر إجراء انتخابات رئاسية مبكرة. في اليوم التالي، عاد يانوكوڤيتش إلى الظهور في روسيا، وأعلن في مؤتمر صحفي أنه لا يزال رئيساً بالنيابة لأوكرانيا، تمامًا كما كانت روسيا تبدأ حملتها العسكرية العلنية في شبه جزيرة القرم.

أعلن زعماء المناطق الشرقية الناطقة بالروسية استمرار ولائهم ليانوكوڤيتش،[118][121]مما تسبب في الاضطرابات الموالية لروسيا لعام 2014 في أوكرانيا.

في 23 فبراير، اعتمد البرلمان مشروع قانون لإلغاء قانون 2012 الذي منح اللغة الروسية وضعاً رسمياً.[122]لم يتم سن مشروع القانون،[123] ومع ذلك، أثار الاقتراح ردود فعل سلبية في المناطق الناطقة بالروسية في أوكرانيا،[124]كما كثفت وسائل الإعلام الروسية قائلة إن السكان من أصل روسي في خطر داهم.[125]

في غضون ذلك، في صباح يوم 27 فبراير، استولت وحدات الشرطة الخاصة في بيركوت من شبه جزيرة القرم ومناطق أخرى في أوكرانيا، والتي تم حلها في 25 فبراير، على نقاط تفتيش على برزخ پركوپ وشبه جزيرة تشونهار.[126][127] وفقًا لعضو البرلمان الأوكراني هينادي موسكال، الرئيس السابق لشرطة القرم، كان لدى بيركوت ناقلة جند مدرعة، قاذفات قنابل، بنادق هجومية، رشاشات وأسلحة أخرى.[127] ومنذ ذلك الحين، سيطروا على كل حركة المرور البرية بين شبه جزيرة القرم وأوكرانيا القارية.[127]

في 7 فبراير 2014، كشف تسجيل صوتي تم تسريبه أن مساعد وزيرة الخارجية الأمريكية للشؤون الأوروبية والأوراسية ڤكتوريا نولاند في كييڤ، كان يدرس تشكيل الحكومة الأوكرانية المقبلة. أخبرت نولاند سفير الولايات المتحدة جفري پيات أنها لا تعتقد أن ڤيتالي كلتشكو يجب أن يكون في حكومة جديدة. تم نشر المقطع الصوتي لأول مرة على تويتر بواسطة دمتري لوسكوتوڤ، مساعد نائب رئيس الوزراء الروسي دميتري روگوزين.[128]

التمويل الروسي للميليشيات وعصابات گلازييڤ

في أغسطس 2016، نشر جهاز الأمن الأوكراني (SBU) الدفعة الأولى من عمليات اعتراض الهاتف من عام 2014 لـ سرگي گلازييڤ (مستشار رئاسي روسي) وكنستانتن زاتولين وأشخاص آخرين ناقشوا التمويل السري للنشطاء الموالين لروسيا في شرق أوكرانيا، واحتلال المباني الإدارية وغيرها من الإجراءات التي أدت في الوقت المناسب إلى النزاع المسلح.[129] رفض گلازييڤ إنكار صحة الاعتراضات، بينما أكد زاتولين أنها حقيقية لكنها "خرجت عن سياقها".[130] تم تقديم دفعات أخرى كدليل خلال الإجراءات الجنائية ضد الرئيس السابق يانوكوڤيتش في محكمة أوبولون في كييڤ بين عامي 2017 و2018.[131]

As early as February 2014, Glazyev was giving direct instructions to various pro-Russian parties in Ukraine to instigate unrest in Donetsk, Kharkiv, Zaporizhia, and Odessa. Glazyev instructs various pro-Russian actors on the necessity of taking over local administration offices, what to do after they were taken over, how to formulate their demands and makes various promises about support from Russia, including "sending our guys".[132][133][134]

Konstantin Zatulin: ... That's the main story. I want to say about other regions – we have financed Kharkiv, financed Odesa.

...

Sergey Glazyev: Look, the situation in the process. Kharkiv Regional State Administration has already been stormed, in Donetsk the Regional State Administration has been stormed. It is necessary to storm Regional State Administration and gather regional deputies there!

...

Sergey Glazyev: It is very important that people appeal to Putin. Mass appeals directly to him with a request to protect, an appeal to Russia, etc. This appeal has been already in your meeting.

...

Denis Yatsyuk: So we after storming building of Regional State Administration we gather a session of the Regional State Administration, right? We invite MPs and force them to vote? ...

— Sergey Glazyev et al.، "English translation of audio evidence of the involvement of Putin's adviser Glazyev and other Russian politicians in the war in Ukraine", UAPosition.com

In further calls recorded in February and March 2014, Glazyev points out that the "peninsula 't have its own electricity, water, or gas" and a "quick and effective" solution would be expansion to the north. According to Ukrainian journalists, this indicates that the plans for military intervention in Donbas to form a Russia-controlled puppet state of Novorossiya to ensure supplies to annexed Crimea was discussed long before the conflict actually started in April. Some also pointed out the similarity of the planned Novorossiya territory to the previous ephemeric project of South-East Ukrainian Autonomous Republic proposed briefly in 2004 by pro-Russian politicians in Ukraine.[131]

On 4 March 2014, Russian permanent representative to the United Nations Vitaly Churkin presented a photocopy of a letter signed by Viktor Yanukovych on 1 March 2014, asking that Russian president Vladimir Putin use Russian armed forces to "restore the rule of law, peace, order, stability and protection of the population of Ukraine".[135] Both houses of the Russian parliament voted on 1 March to give President Putin the right to use Russian troops in Crimea.[136][137] On 24 June Vladimir Putin asked the Russian parliament to cancel the resolution on use of Russian forces in Ukraine.[138] The next day the Federation Council voted to repeal its previous decision, making it illegal to use Russian organized military forces in Ukraine.[139]

Russian bases in Crimea

At the onset of its conflict, Russia had roughly 12,000 military personnel in the Black Sea Fleet,[125] located in several localities throughout Crimean peninsula like Sevastopol, Kacha, Hvardiiske, Simferopol Raion, Sarych and several others. The disposition of the Russian armed forces in Crimea was not disclosed clearly to the public which led to several incidents like the 2005 conflict near Sarych cape lighthouse.[المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك][140] Russian presence was allowed by the basing and transit agreement with Ukraine. According to the agreements Russian military component in Crimea was constrained, including a maximum of 25,000 troops, the requirement to respect the sovereignty of Ukraine, honor its legislation and not interfere in the internal affairs of the country, and show their "military identification cards" when crossing the international border and their operations beyond designated deployment sites were permitted only after coordination with the competent agencies of Ukraine.[141] Early in the conflict, the agreement's sizeable troop limit allowed Russia to significantly reinforce its military presence under the plausible guise of security concern, deploy special forces and other required capabilities to conduct the operation in Crimea.[125]

According to the original treaty on division of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet signed in 1997, the Russian Federation was allowed to have its military bases in Crimea until 2017, after which it had to evacuate all its military units including its portion of the Black Sea Fleet out of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol. A Russian construction project to re-home to fleet in Novorossiysk launched in 2005 and was expected to be fully completed by 2020, but as of 2010, the project faced major budget cuts and construction delays.[142] On 21 April 2010, the former President of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych signed a new deal known as the Kharkiv Pact extending the stay until 2042 with an option to renew and in return receiving some discount on gas delivered from the Russian Federation[143] (see 2009 Russia–Ukraine gas dispute). The Kharkiv Pact was rather an update to complex of several fundamental treaties that were signed in 1990s between prime ministers of both countries Viktor Chernomyrdin (Russia) and Pavlo Lazarenko (Ukraine) and presidents Boris Yeltsin (Russia) and Leonid Kuchma (Ukraine).[144][145][146][147]قالب:Non-primary source needed The Constitution of Ukraine, whilst having a general prohibition of a deployment of foreign bases on the country's soil, originally also had a transitional provision, which allowed the use of existing military bases on the territory of Ukraine for the temporary stationing of foreign military formations. This permitted Russian military to keep its basing in Crimea as an "existing military base". The constitutional provision on "[pre]-existing bases" was revoked in 2019,[148] but by that time Russia had already annexed Crimea and withdrew from the basing treaties unilaterally.

خط زمني

ضم القرم

Russia's decision to annex Crimea was made on 20 February 2014.[149][150][151][152] On 22 and 23 February, Russian troops and special forces began moving into Crimea through Novorossiysk.[151] On 27 February, Russian forces without insignias began taking control of the Crimean Peninsula.[153] They took hold of strategic positions and captured the Crimean Parliament, raising a Russian flag. Security checkpoints were used to cut the Crimean Peninsula off from the rest of Ukraine and to restrict movement within the territory .[154][155][156][157] In the following days, Russian soldiers secured key airports and a communications center.[158] Additionally, the use of cyberwarfare led to websites associated with the official Ukrainian Government websites, the news media, as well as social media shutting down. Cyber attacks also disabled or gained access to the mobile phones of Ukrainian officials and parliament members over the next few days, further severing lines of communication.[159]

On 1 March, the Russian legislature approved the use of armed forces, leading to an influx of Russian troops and military hardware into the peninsula.[158] In the following days, all remaining Ukrainian military bases and installations were surrounded and besieged, including the Southern Naval Base. After Russia formally annexed the peninsula on 18 March, Ukrainian military bases and ships were stormed by Russian forces. On 24 March, Ukraine ordered troops to withdraw; by 30 March, all Ukrainian forces had left the peninsula.

On 15 April, the Ukrainian parliament declared Crimea a territory temporarily occupied by Russia.[160] After the annexation, the Russian government increased its military presence in the region and leveraged nuclear threats to solidify the new status quo on the ground.[161] Russian president Vladimir Putin said that a Russian military task force would be established in Crimea.[162] In November, NATO stated that it believed Russia was deploying nuclear-capable weapons to Crimea.[163]

In December 2014, the Ukrainian Border Guard Service announced that Russian troops had begun to withdraw from the territory of Kherson Oblast. Russian troops occupied parts of the Arabat Spit and the islands surrounding the Syvash, which are geographically parts of Crimea but are administratively part of Kherson Oblast. The village of Strilkove, which is part of Henichesk Raion, was occupied by Russian troops; the village housed an important gas distribution center. Russian forces stated they took over the gas distribution center to prevent terrorist attacks. Later, Russian forces withdrew from southern Kherson but continued to occupy the gas distribution center outside Strilkove. The withdrawal from Kherson ended nearly 10 months of Russian occupation of the region. Ukraine's border guards stated that the areas under Russian occupation will have to be checked for mines before they can return to their positions.[164][165]

Andrey Illarionov, a former economic advisor to Vladimir Putin, said in a speech to NATO on 31 May 2014, that some technologies used during the Russo-Georgian War had been updated and were again being used in Ukraine. According to Illarionov, since the Russian military operation in Crimea began on 20 February 2014, Russian propaganda could not argue that the Russian attack was the result of the Euromaidan protests. Illarionov said that the war in Ukraine did not happen "all of a sudden", but was pre-planned and that the preparations began as early as 2003.[166] He later stated that one of the Russian plans envisaged war with Ukraine in 2015 after a presidential election, but the Euromaidan protests accelerated the confrontation.[167]

War in Donbas (2014–2015)

Pro-Russian unrest

The initial protests across southern and eastern Ukraine were largely native expressions of discontent with the new Ukrainian government.[168] Russian involvement at this stage was limited to its voicing of support for the demonstrations, and the emergence of the separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk began as a small fringe group of the protesters, independent of Russian control.[168][169] Russia would go on to take advantage of this, however, to launch a co-ordinated political and military campaign against Ukraine, as part of the broader Russo-Ukrainian War.[168][170] Russian president Vladimir Putin gave legitimacy to the nascent separatist movement when he described the Donbas as part of the historic "New Russia" (Novorossiya) region, and issued a statement of bewilderment as how the region had ever become part of Ukraine in 1922 with the foundation of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.[171] When the Ukrainian authorities cracked down on the pro-Russian protests and arrested local separatist leaders in early March, these were replaced by people with ties to the Russian security services and interests in Russian businesses, probably by order of Russian intelligence.[172] By April 2014, Russians citizens had taken control of the separatist movement, and were supported by volunteers and materiel from Russia, including Chechen and Cossack militants.[173][174][175][176] According to DPR insurgent commander Igor Girkin, without this support in April, the movement would have fizzled out, as in it did in Kharkiv and Odessa.[177] The disputed referendum on the status of Donetsk Oblast was held on 11 May.[178][179][180]

These demonstrations, which followed the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, and which were part of a wider group of concurrent pro-Russian protests across southern and eastern Ukraine, escalated into an armed conflict between the Russia-backed separatist forces of the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics (DPR and LPR respectively), and the Ukrainian government.[181][182] The SBU claimed key commanders of the rebel movement during the beginning of the conflict, including Igor Strelkov and Igor Bezler were Russian agents.[183][184] The prime minister of Donetsk People's Republic from May to August 2014 was a Russian citizen Alexander Borodai.[175] From August 2014 all top positions in Donetsk and Luhansk have been held by Ukrainian citizens.[185][174] Russian volunteers are reported to make up from 15% to 80% of the combatants,[175][186][187][188][189] with many claimed to be former military personnel.[190][191] Recruitment for the Donbas insurgents was performed openly in Russian cities using private or voyenkomat facilities, as was confirmed by a number of Russian media.[190][192]

Economic and material circumstances in Donbas had generated neither necessary nor sufficient conditions for a locally rooted, internally driven armed conflict. The role of the Kremlin's military intervention was paramount for the commencement of hostilities.[193]

March–July 2014

In late March, Russia continued the buildup of military forces near the Ukrainian eastern border, reaching 30–40,000 troops by April.[194][125] The deployment was likely used to threaten escalation and stymie Ukraine's response to unfolding events.[125] Concerns were expressed that Russia may again be readying an incursion into Ukraine following its annexation of Crimea.[194] This threat forced Ukraine to divert force deployment to its borders instead of the conflict zone.[125]

In April, armed conflict begins in eastern Ukraine between Russian-backed separatist forces and Ukrainian government. The separatists declared the People's Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk. From 6 April, Militant occupied government buildings in many cities, as well as, taking control of border crossings to Russia, transport hubs, broadcasting center, and other strategic infrastructure. Faced with continued expansion of separatist territorial control, on 15 April the Ukrainian interim government launched an "Anti-Terrorist Operation" (ATO), however, Ukrainian military and security services were poorly prepared and ill-positioned and the operation quickly stalled.[195] By the end of April, the Ukrainian Government announced it had no full control of the provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk, being on "full combat alert" against a possible Russian invasion and reinstatement of conscription to the armed forces.[196] Through May, Ukrainian campaign focused on containing the separatists by securing key positions around the ETO zone to position the military for a decisive offensive against the rebel enclave once Ukraine's national mobilization complete.

As conflict between the separatists and the Ukrainian government escalated in May, Russia began to employ a "hybrid approach", deploying a combination of disinformation tactics, irregular fighters, regular Russian troops, and conventional military support to support the separatists and destabilise the Donbas region.[197][198][199] The First Battle of Donetsk Airport that followed the Ukrainian presidential elections marked a turning point in conflict; it was the first battle between the separatists and the Ukrainian government that involved large amounts of Russian volunteers.[200][201] According to the Ukrainian government, at the height of the conflict in the summer of 2014, Russian paramilitaries were reported to make up between 15% to 80% of the combatants.[175] From June Russia trickled in arms, armor, and munitions to the separatist forces.

In June–July, the ATO operation began to regain ground, utilizing its numbers and air power to steadily encircle and push out the separatists re-taking several towns and key positions in Donbas, including the separatist stronghold of Sloviansk and the key port city of Mariupol.

On 17 July a Russian Buk anti-aircraft missile shot down Malaysia Airlines Flight 17. All 283 passengers and 15 crew were killed.[202]

By the end of July, they were pushing into Donetsk and Luhansk cities, to cut off supply routes between the two, isolating Donetsk and thought to restore control of the Russo-Ukrainian border. By 28 July, the strategic heights of Savur-Mohyla were under Ukrainian control, along with the town of Debaltseve an important railroad hub.[203] These operational successes of Ukrainian forces threatened the very existence of Russian-supported DPR and LPR statelets, prompting Russian cross-border artillery shelling targeted against advancing Ukrainian troops on their own soil, from mid-July onwards.

American and Ukrainian officials said they had evidence of Russian interference in Ukraine, including intercepted communications between Russian officials and Donbas insurgents.[204][205]

Ukrainian media have described the well-organised and well-armed pro-Russian militants as similar to those which occupied regions of Crimea during the Crimean crisis.[206][207] The former deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, Admiral Ihor Kabanenko, said that the militants are Russian military reconnaissance and sabotage units.[208] Arsen Avakov stated that the militants in Krasnyi Lyman used Russian-made AK-100 series assault rifles fitted with grenade launchers, and that such weapons are only issued in the Russian Federation. "The Government of Ukraine is considering the facts of today as a manifestation of external aggression by Russia," said Avakov.[209] Militants in Sloviansk arrived in military lorries without license plates.[210] A reporter from Russia's Novaya Gazeta, having visited separatist artillery positions in Avdeyevka, wrote that in his opinion "it's impossible that the cannons are handled by volunteers" as they require a trained and experienced team, including observers and adjustment experts.[211]

David Patrikarakos, a correspondent for the New Statesman said the following: "While at the other protests/occupations there were armed men and lots of ordinary people, here it almost universally armed and masked men in full military dress. Automatic weapons are everywhere. Clearly a professional military is here. There's the usual smattering of local militia with bats and sticks but also a military presence. Of that there is no doubt."[212] Zbigniew Brzezinski, a former American National Security Advisor, said that the events in the Donbas were similar to events in Crimea, which led to its annexation by Russia, and noted that Russia acted similarly.[213]

In April 2014, a US State Department spokeswoman, Jen Psaki, said, "There has been broad unity in the international community about the connection between Russia and some of the armed militants in eastern Ukraine".[214] The Ukrainian government released photos of soldiers in eastern Ukraine, which the US State Department said showed that some of the fighters were Russian special forces.[215][216] US Secretary of State John Kerry said the militants "were equipped with specialized Russian weapons and the same uniforms as those worn by the Russian forces that invaded Crimea."[217] The US ambassador to the United Nations said the attacks in Sloviansk were "professional," "coordinated," and that there was 'nothing grass-roots seeming about it'.[218] The British foreign secretary, William Hague, stated, "I don't think denials of Russian involvement have a shred of credibility, ... The forces involved are well armed, well trained, well equipped, well coordinated, behaving in exactly the same way as what turned out to be Russian forces behaved in Crimea."[219] The commander of NATO operations in Europe, Philip M. Breedlove, assessed that soldiers appeared to be highly trained and not a spontaneously formed local militia, and that "what is happening in eastern Ukraine is a military operation that is well planned and organized and we assess that it is being carried out at the direction of Russia."[220]

The New York Times journalists interviewed Sloviansk militants and found no clear link of Russian support: "There was no clear Russian link in the 12th Company's arsenal, but it was not possible to confirm the rebels' descriptions of the sources of their money and equipment."[221] Commenting on the presence of the Vostok Battalion within insurgent ranks, Denis Pushilin, self-declared Chairman of the People's Soviet of the Donetsk People's Republic, said on 30 May, "It's simply that there were no volunteers [from Russia] before, and now they have begun to arrive – and not only from Russia."[222]

A significant number of Russian citizens, many veterans or ultranationalists, are currently involved in the ongoing armed conflict, a fact acknowledged by separatist leaders. Carol Saivetz, Russian specialist for the Security Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, described the role of Russian soldiers as 'almost certainly' proceeding with the blessing and backing of the Russian state, "even if the Russians are indeed volunteers rather than serving military men".[223]

August–September 2014

After a series of military defeats and setbacks for the Donetsk and Luhansk separatists, who united under the banner of "Novorossiya", a term Russian President Vladimir Putin used to describe southeastern Ukraine,[224][225] Russia dispatched what it called a "humanitarian convoy" of trucks across the Russo-Ukrainian border in mid-August 2014. Ukraine reacted to the move by calling it a "direct invasion".[226] Ukraine's National Security and Defence Council published a report on the number and contents of these convoys, claiming they were arriving almost daily in November (up to 9 convoys on 30 November) and their contents were mainly arms and ammunition. In total, in November there were 1,903 trucks crossing the border from Russia to Donbas, 20 buses with soldiers or volunteers, 402 armoured personnel carriers, 256 tanks, 138 "Grad" launchers, 42 cannons and howitzers, 35 self-propelled artillery vehicles, 5 "Buk" launchers, 4 "Uragan" launchers, 4 "Buratino" flamethrowers, 6 pontoon bridge trucks, 5 "Taran" radio interception systems, 5 armoured recovery vehicles, 3 radiolocation systems, 2 truck cranes, 1 track layer vehicle, 1 radiolocation station, unknown number of "Rtut-BM" electronic warfare systems, 242 fuel tankers and 205 light off-road vehicles and vans.[227]

In early August, according to Igor Strelkov, Russian servicemen, supposedly on "vacation" from the army, began to arrive in Donbas.[228]

By August 2014, the Ukrainian "Anti-Terrorist Operation" was able to vastly shrink the territory under the control of the pro-Russian forces, and came close to regaining control of the Russo-Ukrainian border.[229] Igor Girkin urged Russian military intervention, and said that the combat inexperience of his irregular forces, along with recruitment difficulties amongst the local population in Donetsk Oblast had caused the setbacks. He addressed Russian president Vladimir Putin, saying that: "Losing this war on the territory that President Vladimir Putin personally named New Russia would threaten the Kremlin's power and, personally, the power of the president".[230] In response to the deteriorating situation in the Donbas, Russia abandoned its hybrid approach, and began a conventional invasion of the region.[229][231] The first sign of this invasion was 25 August 2014 capture of a group of Russian paratroopers on active service in Ukrainian territory by the Ukrainian security service (SBU).[232] The SBU released photographs of them, and their names.[233] On the following day, the Russian defence Ministry said these soldiers had crossed the border "by accident".[234][235][236] According to Nikolai Mitrokhin's estimates, by mid-August 2014 during the Battle of Ilovaisk, there were between 20,000 and 25,000 troops fighting in the Donbas on the separatist side, and only between 40% and 45% were "locals".[237]

Journalist Tim Judah wrote in the NYR blog about the scale of the devastation suffered by Ukrainian forces in southeastern Ukraine over the last week of August 2014 that it amounted "to a catastrophic defeat and will long be remembered by embittered Ukrainians as among the darkest days of their history." The scale of the destruction achieved in several ambushes revealed "that those attacking the pro-government forces were highly professional and using very powerful weapons." The fighting in Ilovaysk had begun on 7 August when units from three Ukrainian volunteer militias and the police attempted to take it back from rebel control. Then, on 28 August, the rebels were able to launch a major offensive, with help from elsewhere, including Donetsk—though "not Russia," according to Commander Givi, the head of rebel forces there. By 1 September it was all over and the Ukrainians had been decisively defeated. Commander Givi said the ambushed forces were militias, not regular soldiers, whose numbers had been boosted, 'by foreigners, including Czechs, Hungarians, and "niggers." '[238]

On 13 August, members of the Russian Human Rights Commission stated that over 100 Russian soldiers had been killed in the fighting in Ukraine and inquired why they were there.[239]

A convoy of military vehicles, including armoured personnel carriers, with official Russian military plates crossed into Ukraine near the militant-controlled Izvaryne border crossing on 14 August.[240][241] The Ukrainian government later announced that they had destroyed most of the armoured column with artillery. Secretary General of NATO Anders Fogh Rasmussen said this incident was a "clear demonstration of continued Russian involvement in the destabilisation of eastern Ukraine".[242] The same day, Russian President Vladimir Putin, speaking to Russian ministers and Crimean parliamentarians on a visit to Crimea, undertook to do everything he could to end the conflict in Ukraine, saying Russia needed to build calmly and with dignity, not by confrontation and war which isolated it from the rest of the world. The comments came as international sanctions against Russia were being stepped up.[243]

Multiple reports indicated separatist militias were receiving reinforcements that allowed them to turn the tables on government forces.[244] Armoured columns coming from Russia also pushed into southern Donetsk Oblast and reportedly captured the town of Novoazovsk, clashing with Ukrainian forces and opening a new front in the Donbas conflict.[245][246]

On 22 August 2014, according to NATO officials, Russia moved self-propelled artillery onto the territory of Ukraine.[247]

On 24 August 2014, President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko referred to the anti-terrorist operation (ATO) as Ukraine's "Patriotic War of 2014" and a war against "external aggression".[248][249] The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine labeled the conflict an invasion on 27 August 2014.[250] The same day, Amvrosiivka was occupied by Russian paratroopers,[251] supported by 250 armoured vehicles and artillery pieces.[252] Ten Russian paratroopers of the 331st Guards Airborne Regiment, military unit 71211 from Kostroma, were captured in Dzerkalne that day, a village near Amvrosiivka, 20 kilometres (12 mi) from the border,[253] after their armoured vehicles were hit by Ukrainian artillery. On 25 August, the Security Service of Ukraine reported about the captured paratroopers, claiming they've crossed Ukrainian border in the night of 23 August.[254] The SBU also released their photos and names.[255] The next day, the Russian Ministry of Defence said that they had crossed the border "by accident".[253][256]

On 25 August, a column of Russian tanks and military vehicles was reported to have crossed into Ukraine in the southeast, near the town of Novoazovsk located on the Azov sea coast, and headed towards Ukrainian-held Mariupol,[257][245][258][259][260] in an area that had not seen pro-Russian presence for weeks.[261] The Bellingcat's investigation reveals some details of this operation.[262] Russian forces captured the city of Novoazovsk.[263] and Russian soldiers began arresting and deporting to unknown locations all Ukrainians who did not have an address registered within the town.[264] Pro-Ukrainian anti-war protests took place in Mariupol which was threatened by Russian troops.[264][265] The UN Security Council called an emergency meeting to discuss the situation.[266]

On 26 August 2014, a mixed column composed of at least 3 T-72B1s and a lone T-72BM was identified on a video from Sverdlovsk, Ukraine by the International Institute for Strategic Studies. The sighting undermined Russia's attempts to maintain plausible deniability over the issue of supplying tanks and other arms to the separatists. Russia continuously claimed that any tanks operated by the separatists must have been captured from Ukraine's own army. The T-72BM is in service with the Russian Army in large numbers. This modernized T-72 is not known to have been exported to nor operated by any other country.[267] Reuters found other tanks of this type near Horbatenko in October.[268] In November, the United Kingdom's embassy in Ukraine also published an infographic demonstrating specific features of the T-72 tanks used by separatists not present in tanks held by Ukrainian army, addressing it to "help Russia recognize its own tanks".[269] The equipment included for example Thales Optronics thermal vision instruments exported to Russia between 2007 and 2012 only.[270]

On 27 August, two columns of Russian tanks entered Ukrainian territory in support of the pro-Russian separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk and engaged Ukrainian border forces, but US officials were reluctant to declare that Russia had begun invading Ukraine.[271] NATO officials stated that over 1,000 Russian troops were operating inside Ukraine, but termed the incident an incursion rather than an invasion.[272] The Russian government denied these claims. NATO published satellite photos which it said showed the presence of Russian troops within Ukrainian territory.[239] The pro-Russian separatists admitted that Russian troops were fighting alongside them, stating that this was "no secret", but that the Russian troops were just soldiers who preferred to take their vacations fighting in Ukraine rather than "on the beach". The Prime Minister of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic stated that 3,000 to 4,000 Russian troops had fought in separatist ranks and that most of them had not returned to Russia, having continued to fight in Ukraine.[273]

On 28 August, members of the commission called the presence of Russian troops on Ukrainian soil "an outright invasion".[274] The same day, Ukraine ordered national mandatory conscription.[275] Dutch Brigadier-General Nico Tak, head of NATO's crisis management centre, said that "over 1,000 Russian troops are now operating inside Ukraine".[276]

In late August, NATO released satellite images which it considered to be evidence of Russian operations inside Ukraine with sophisticated weaponry,[277] and after the setbacks[83] of Ukrainian forces by early September, it was evident Russia had sent soldiers and armour across the border and locals acknowledged the role of Putin and Russian soldiers in effecting a reversal of fortunes.[39][80][81][278][279]

On 29 August, after Ukrainian forces agreed to surrender Ilovaisk, they were bombarded by Russian forces while they evacuated through a "green corridor." The assault on the troops who were marked with white flags was variously described as a "massacre."[39][280][281][282][283][284] At least 100 were killed.[280] Around 29–30 August, Russian tanks destroyed "virtually every house" in Novosvitlivka, a suburb village of Luhansk, according to Ukrainian military spokesman Andriy Lysenko.[285] On 31 August, the Russian media reported that ten Russian paratroopers captured inside Ukraine had returned home following a troop exchange. The 64 Ukrainian troops provided in exchange were captured after entering Russia to escape the upsurge in fighting.[286] Russia claimed that the Russian troops had mistakenly crossed an unmarked area of the border while on patrol.[287] Ukraine released videos of captured Russian soldiers which challenged Russia's claim that it had nothing to do with the conflict.[288]

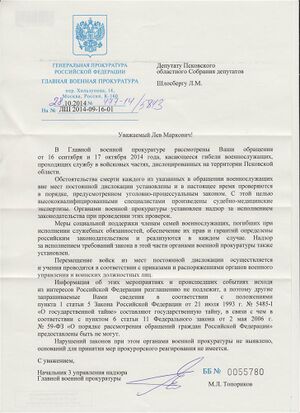

The 76th Guards Air Assault Division based in Pskov allegedly entered Ukrainian territory in August and engaged in a skirmish near Luhansk, suffering 80 dead. The Ukrainian Defence Ministry said that they had seized two of the unit's armoured vehicles near Luhansk city, and reported about another three tanks and two armoured vehicles of pro-Russian forces destroyed in other regions.[290][291] The Russian government denied the skirmish took place[291] but on 18 August, the 76th Guards Air Assault Division was awarded with Order of Suvorov, one of Russia's highest awards, by Russian minister of defence Sergey Shoigu for the "successful completion of military missions" and "courage and heroism".[291] Russian media highlighted that the medal is awarded exclusively for combat operations and reported that a large number of soldiers from this division had died in Ukraine just days before, but their burials were conducted in secret.[292][293][294] Some Russian media, such as Pskovskaya Guberniya,[295] reported that Russian paratroopers may have been killed in Ukraine. Journalists traveled to Pskov, the reported burial location of the troops, to investigate. Multiple reporters said they had been attacked or threatened there, and that the attackers erased several camera memory cards.[296] Pskovskaya Guberniya revealed transcripts of phone conversations between Russian soldiers being treated in a Pskov hospital for wounds received while fighting in Ukraine. The soldiers reveal that they were sent to the war, but told by their officers that they were going on "an exercise".[297][298]

According to Bellingcat, Russian military vehicles crossing the border of Ukraine and artillery positions close to the Ukrainian borders are clearly visible on satellite photos from 23 August 2014.[299] A Bellingcat contributor published a series of investigations revealing the involvement of the Russian Northern Fleet Coastal troops units, 200th Motor Rifle Brigade and 61st Naval Infantry Brigade, which had participated in combats in Luhansk region: Troops of the 200th Motor Rifle Brigade fought in a battle of Luhansk Airport,[300][301] and later in October in clashes for 32nd checkpoint.[302] Marines of the 61st Naval Infantry Brigade were spotted in Luhansk and took part in fights in villages nearby.[303]

The speaker of Russia's upper house of parliament and Russian state television channels acknowledged that Russian soldiers entered Ukraine, but referred to them as "volunteers".[304] A reporter for Novaya Gazeta, an opposition newspaper in Russia, stated that the Russian military leadership paid soldiers to resign their commissions and fight in Ukraine in the early summer of 2014, and then began ordering soldiers into Ukraine. This reporter mentioned knowledge of at least one case when soldiers who refused were threatened with prosecution.[305] Russian opposition MP Lev Shlosberg made similar statements, although he said combatants from his country are "regular Russian troops", disguised as units of the DPR and LPR.[306] In early September 2014, Russian state-owned television channels reported on the funerals of Russian soldiers who died in Ukraine during the war in Donbas, but described them as "volunteers" fighting for the "Russian world". Valentina Matviyenko, a top politician in the ruling United Russia party, also praised "volunteers" fighting in "our fraternal nation", referring to Ukraine.[304] Russian state television for the first time showed the funeral of a soldier killed fighting in east Ukraine. State-controlled TV station Channel One showed the burial of paratrooper Anatoly Travkin in the central Russian city of Kostroma. The broadcaster said Travkin had not told his wife or commanders about his decision to fight alongside pro-Russia rebels battling government forces. "Officially he just went on leave," the news reader said.[307]

Lindsey Hilsum wrote in the Channel 4 news blog that in early September Ukrainian troops at Dmytrivka came under attack from BM-30 Smerch rockets from Russia.[308] On 4 September, she wrote of rumours that Ukrainian troops who had been shelling Luhansk for weeks were retreating west and that Russian soldiers with heavy armour were reported to have come over the border to back up the rebels.[309] Hilsum also wrote about the total destruction of Luhansk International Airport which was being used as a base by the Ukrainian forces to shell Luhansk, probably because the Russians decided to 'turn the tide' – the terminal building and everything around was utterly destroyed. Forces from Azerbaijan, Belarus and Tajikistan who were fighting on the side of the rebels allowed themselves to be filmed.[310]

Mariupol offensive

On 3 September 2014, a Sky News team filmed groups of troops near Novoazovsk wearing modern combat gear typical for Russian units and traveling in new military vehicles with number plates and other markings removed. Specialists consulted by the journalists identified parts of the equipment (uniform, rifles) as currently used by Russian ground forces and paratroopers.[311]

Also on, 3 September, Ukrainian President Poroshenko said he had reached a "permanent ceasefire" agreement with Russian President Putin.[312] Russia denied the ceasefire agreement took place, denying being party to the conflict at all, adding that "they only discussed how to settle the conflict".[313][314] Poroshenko then backtracked from his previous statement about the agreement.[315][316]

The OSCE for the first time reported "light and heavy calibre shootings from the east and south-east areas which are also bordering Ukraine". The report also stated that the OSCE Observer Teams had seen an increase of military-style dressed men crossing the border in both directions, including ones with LPR and Novorossiya symbols and flags, and wounded being transported back to Russia.[317]

Mick Krever wrote on the CNN blog that on 5 September Russia's Permanent Representative to the OSCE, Andrey Kelin had said it was natural pro-Russian separatists "are going to liberate" Mariupol. Ukrainian forces stated that Russian intelligence groups had been spotted in the area. Kelin said 'there might be volunteers over there.'[318] On 4 September 2014, a NATO officer said there were several thousand regular Russian forces operating in Ukraine.[319]

On 5 September 2014, the ceasefire agreement called the Minsk Protocol, drew a line of demarcation between Ukraine and separatist-controlled portions of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts in the southeast of the country.

On 12 September 2014, The Guardian saw a Russian armoured personnel carrier in Lutuhyne.[320] The next day, it was reported that Moscow had sent a convoy of trucks delivering "aid" into Ukraine without Kyiv's consent. This convoy was not inspected by Ukraine or accompanied by the ICRC. Top Ukrainian leaders largely remained silent about the convoys after the ceasefire deal was reached. The "aid" was part of the 12-point Minsk agreement.[321][322]

In December 2014, Ukrainian hackers published a large cache of documents coming allegedly from a hacked server of Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs (MID). The documents originated from various departments coordinated by MID, such as local police, road police, emergency services etc. The cache included documents describing Russian military casualties arriving on 25 August to hospitals in the Rostov area after a battle "10 km northwest of the small village of Prognoi", which matched a battle in Krasnaya Talovka reported on the same date by Ukrainian side.[323]

November 2014 escalation

On 7 November, NATO officials confirmed the continued invasion of Ukraine, with 32 Russian tanks, 16 howitzer cannons and 30 trucks of troops entering the country.[324] On 12 November, NATO reiterated the prevalence of Russian troops; US general Philip Breedlove said "Russian tanks, Russian artillery, Russian air defence systems and Russian combat troops" were sighted.[163] The Lithuanian Mission to the United Nations denounced Russia's 'undeclared war' on Ukraine.[325] Journalist Menahem Kahana took a picture showing a 1RL232 "Leopard" battlefield surveillance radar system in Torez, east of Donetsk; and Dutch freelance journalist Stefan Huijboom took pictures which showed the 1RL232 traveling with the 1RL239 "Lynx" radar system.[326]

Burnt-out remains of tanks and vehicles left after battles appeared to provide further evidence of Russian involvement.[327]

The Associated Press reported 80 unmarked military vehicles on the move in rebel-controlled areas. Three separate columns were observed, one near the main separatist stronghold of Donetsk and two outside the town of Snizhne. Several of the trucks were seen to be carrying troops.[86]

OSCE monitors further observed vehicles apparently used to transport soldiers' dead bodies crossing the Russian-Ukrainian border – in one case a vehicle marked with Russia's military code for soldiers killed in action crossed from Russia into Ukraine on 11 November 2014, and later returned.[88] On 23 January 2015 the Committee of Soldiers' Mothers warned about conscripts being sent to east Ukraine.[328] NATO said it had seen an increase in Russian tanks, artillery pieces and other heavy military equipment in eastern Ukraine and renewed its call for Moscow to withdraw its forces.[329]

The centre for Eurasian Strategic Intelligence estimated, based on "official statements and interrogation records of captured military men from these units, satellite surveillance data" as well as verified announcements from relatives and profiles in social networks, that over 30 Russian military units were taking part in the conflict in Ukraine. In total, over 8,000 soldiers had fought there at different moments.[330] The Chicago Council on Global Affairs stated that the Russian separatists enjoyed technical advantages over the Ukrainian army since the large inflow of advanced military systems in mid-2014: effective anti-aircraft weapons ("Buk", MANPADS) suppressed Ukrainian air strikes, Russian drones provided intelligence, and Russian secure communications system thwarted the Ukrainian side from communications intelligence. The Russian side also frequently employed electronic warfare systems that Ukraine lacked. Similar conclusions about the technical advantage of the Russian separatists were voiced by the Conflict Studies Research Centre.[331]

In November 2014, Igor Girkin gave a long interview to the extreme right-wing[332] nationalist newspaper Zavtra ("Tomorrow") where for the first time he released details about the beginning of the conflict in Donbas. According to Girkin, he was the one who "pulled the trigger of war" and it was necessary because acquisition of Crimea alone by Russia "did not make sense" and Crimea as part of the Novorossiya "would make the jewel in the crown of the Russian Empire". Girkin had been directed to Donbas by Sergey Aksyonov and he entered Ukraine with a group of 52 officers in April, initially taking Slavyansk, Kramatorsk and then other cities. Girkin also talked about the situation in August, when separatist forces were close to defeat and only a prompt intervention of Russian "leavers" (ironic term for "soldiers on leave") saved them. Their forces took command in the siege of Mariupol as well.[333][334] In response to internal criticism of the Russian government's policy of not officially recognizing Russian soldiers in Ukraine as fulfilling military service and leaving their families without any source of income if they are killed, president Vladimir Putin signed a new law in October entitling their families to a monthly compensation. Two new entitlement categories were added: "missing in action" and "declared dead" (as of 1 January 2016).[335][336]

Alexandr Negrebetskih, a deputy from the Russian city of Zlatoust who fought as a volunteer on the side of separatists, complained in an interview that "the locals run to Russia, and we have to come here as they are reluctant to defend their land" which resulted in his detachment being composed of 90% Russians and only 10% locals from Donetsk.[337]

In November, Lev Shlosberg published a response from a military attorney's office to questions he asked about the status of Pskov paratroopers killed in Ukraine in August. The office answered that the soldiers died while "fulfilling military service outside of their permanent dislocation units" (Pskov), but any further information on their orders or location of death was withheld as "classified". A political expert Alexey Makarkin compared these answers to those provided by Soviet ministry of defence during the Soviet–Afghan War when the USSR attempted to hide the scale of their casualties at any cost.[338]

Numerous reports of Russian troops and warfare on Ukrainian territory were raised in United Nations Security Council meetings. In 12 November meeting, the representative of the United Kingdom also accused Russia of intentionally constraining OSCE observatory missions' capabilities, pointing out that the observers were allowed to monitor only two kilometers of border between Ukraine and Russia, and drones deployed to extend their capabilities were being jammed or shot down.[339]

In November, Armament Research Services published a detailed report on arms used by both sides of the conflict, documenting a number of "flag items". Among vehicles, they documented the presence of T-72B Model 1989 and T-72B3 tanks, armoured vehicles of models BTR-82AM, MT-LB 6MA, MT-LBVM, and MT-LBVMK, and an Orlan-10 drone and 1RL239 radar vehicle. Among the ammunition, they documented 9K38 Igla (date of manufacture 2014), ASVK rifle (2012), RPG-18 rocket launchers (2011), 95Ya6 rocket boosters (2009) MRO-A (2008), 9M133 Kornet anti-tank weapons (2007), PPZR Grom (2007), MON-50 (2002), RPO-A (2002), PKP (2001), OG-7 (2001), and VSS rifles (1987). These weapons, mostly manufactured in Russia, were used by pro-Russian separatists in the conflict zone, but never "were in the Ukrainian government inventory prior to the outbreak of hostilities". The report also noted the use of PPZR Grom MANPADs, produced in Poland and never exported to Ukraine. They were however exported to Georgia in 2007 and subsequently captured by the Russian army during the Russian-Georgian War 2008.[340] Also in November, Pantsir-S1 units were observed in separatist-controlled areas near Novoazovsk, which were never part of the UAF's inventory.[341] Bellingcat maintains a dedicated database of geolocated images of military vehicles specific to each side of the conflict, mostly focused on Russian military equipment found on Ukrainian territory.[342]

2015 and ceasefire

In January, Donetsk, Luhansk, and Mariupol were the three cities that represented the three fronts on which Ukraine was pressed by forces allegedly armed, trained and backed by Russia.[344]

In early January 2015, an image of a BPM-97 apparently inside Ukraine, in Luhansk, provided further evidence of Russian military vehicles inside Ukraine.[345][346]

Poroshenko spoke of a dangerous escalation on 21 January amid reports of more than 2,000 additional Russian troops crossing the border, together with 200 tanks and armed personnel carriers. He abbreviated his visit to the World Economic Forum in Davos because of his concerns at the worsening situation.[347] On 29 January, the chief of Ukraine's General Military Staff Viktor Muzhenko said 'the Ukrainian army is not engaged in combat operations against Russian regular units,' but that he had information about Russian civilian and military individuals fighting alongside 'illegal armed groups in combat activities.'[348] Reporting from DPR-controlled areas on 28 January, the OSCE observed on the outskirts of Khartsyzk, east of Donetsk, "a column of five T-72 tanks facing east, and immediately after, another column of four T-72 tanks moving east on the same road which was accompanied by four unmarked military trucks, type URAL. All vehicles and tanks were unmarked." It reported on an intensified movement of unmarked military trucks, covered with canvas.[349] After the shelling of residential areas in Mariupol, NATO's Jens Stoltenberg said: "Russian troops in eastern Ukraine are supporting these offensive operations with command and control systems, air defence systems with advanced surface-to-air missiles, unmanned aerial systems, advanced multiple rocket launcher systems, and electronic warfare systems."'[329][350]

Svetlana Davydova, a mother of seven, was accused of treason for calling the Ukrainian embassy about Russian troop movements and arrested on 27 January 2015. She was held at the high-security Lefortovo jail in Moscow until her release on 3 February with charges against her still pending. The Russian General Staff said details of the case constituted a "state secret."[351][352] On 9 February 2015, a group of 20 contract soldiers from Murmansk raised an official complaint to the Russian ministry of defence when they were told they would "go to the Rostov area and possibly cross the Ukrainian border to fulfill their patriotic duty". The soldiers notified human rights activists and requested the orders in written form, which they were not given.[353][354] On 13 February, a young soldier, Ilya Kudryavtsev, was found dead after calling home and informing his relatives that he was to be sent on a mission to Rostov-on-Don, which is the usual starting point to Ukraine. Although he was severely beaten, his death was officially classified as a suicide.[355]

2015–2021

According to a top U.S. general in January, Russian supplied drones and electronic jamming have ensured Ukrainian troops struggle to counter artillery fire by pro-Russian militants. "The rebels have Russian-provided UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) that are giving the rebels the detection capability and the ability to target Ukrainian forces".[356] Advanced electronic jamming was also reported by OSCE observers on numerous occasions.[357]

In February, both Ukrainian and DNR sides reported unknown sabotage groups firing at both sides of the conflict and also on residential areas, calling them a "third force".[358] SBU published an intercepted call in which DNR commanders reported such a group had been arrested with Russian passports and military documents.[359] DNR confirmed that such groups were indeed stopped and "destroyed" but called them "Ukrainian sabotage groups working to discredit the armed forces of the Russian Federation".[360]

US Army commander in Europe Ben Hodges stated in February 2015 that "it's very obvious from the amount of ammunition, type of equipment, there's direct Russian military intervention in the Debaltseve area".[361] According to estimates by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs in February, Russian separatists forces number around 36,000 troops (as compared to 34,000 Ukrainian), of which 8,500–10,000 are purely Russian soldiers. Additionally, around 1,000 GRU troops are operating in the area.[362] According to a military expert, Ilya Kramnik, total Ukrainian forces outnumber the Russian forces by a factor of two (20,000 Russian separatists vs. 40,000 fighting for Ukraine).[363]

In February 2015, the independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta had obtained documents,[364] allegedly written by oligarch Konstantin Malofayev and others, which provided the Russian government with a strategy in the event of Viktor Yanukovych's removal from power and the break-up of Ukraine, which were considered likely. The documents outlined plans for the annexation of Crimea and the eastern portions of the country, closely describing the events that actually followed after Yanukovych's fall. The documents also described plans for a public relations campaign which would seek to justify Russian actions.[365][366][367]

In March 2015, Novaya Gazeta published an interview with a Russian soldier, Dorzhi Batomunkuev, who operated a tank in the Battle of Debaltseve and was wounded. He confirmed that the tanks came from his military unit in Ulan-Ude in Russia and that his unit "painted over the serial numbers and unit signs straight away on the rail platforms". In November 2014, Batomunkuev was sent as a conscript to Rostov-on-Don, where he became a contract soldier. Traveling by train with his unit from Ulan-Ude, Batomunkuev said he saw "plenty of such trains" traveling along with them "day after day". After three months at Kosminskiy training facility, their unit of 31 tanks and 300 soldiers in total (mostly Buryats) was given an order to move on 8 February 2015 and crossed the Ukrainian border in the night, arriving in Donetsk in the morning. They took part in the battle on 12–14 February.[368][369][370] Joseph Kobzon met Batomunkuev in the same hospital a few days before the NG interview.[371] In 2016 Alexander Minakov, another Russian soldier wounded in the battle of Debaltseve, was awarded a medal "For services to the Fatherland".[372] In March 2015, president Putin awarded the honorary name of "Guards" to two divisions: 11. paratroopers brigade from Ulan-Ude, 83. paratroopers brigade from Ussuriysk and 38. communications regiment from Moscow area. The status was awarded for undisclosed combat operations.[373]

A report by Igor Sutyagin published by the Royal United Services Institute in March 2015 stated that a total of 42,000 regular Russian combat troops have been involved in the fighting, with a peak strength of 10,000 in December 2014. The direct involvement of the Russian troops on Ukrainian territory began in August 2014, at a time when Ukrainian military successes created the possibility that the pro-Russian rebels would collapse. According to the report, the Russian troops are the most capable units on the anti-Ukrainian side, with the regular Donetsk and Luhansk rebel formations being used essentially as "cannon fodder".[374][375] The Chicago Council on Global Affairs stated that the Russian separatists enjoyed technical advantages over the Ukrainian army since the large inflow of advanced military systems in mid-2014: effective anti-aircraft weapons ("Buk", MANPADS) suppressed Ukrainian air strikes, Russian drones provided intelligence, and Russian secure communications system thwarted the Ukrainian side from communications intelligence. The Russian side also frequently employed electronic warfare systems that Ukraine lacked. Similar conclusions about the technical advantage of the Russian separatists were voiced by the Conflict Studies Research Centre.[375]

In March 2015, a commander of the DPR special forces unit, Dmitry Sapozhnikov, gave an interview to the BBC[376] in which he spoke openly about the involvement of Russian soldiers in the conflict. He described the arrival of Russian military vehicles and personnel from across the border as critical to the success of large-scale operations such as the battle of Debaltseve. Russian high-rank officers planned the operations and regular Russian army units with DPR forces carried them out jointly. In Sapozhnikov's opinion, "everyone knows that" and it's "no secret", but he was surprised to find out that it is not so widely acknowledged in Russia when he returned to Saint Petersburg.[377]

In April 2015, a group of Russian volunteers returning to Ekaterinburg complained in an interview to local media about a lack of support from the local population, who sometimes called them "occupiers", and their highly ambiguous status while in Donbas: Ukraine and "the court in Madrid" considered them to be terrorists; the DPR considered them "illegal armed groups" and offered them contracts, but if they signed they would become mercenaries under Russian law.[378] Another volunteer, a citizen of Latvia nicknamed "Latgalian", told on his return from Donbas that he was disappointed with how the situation there differed from what he had seen in the Russian media: he saw no support and sometimes open hostility to the insurgents from the local civilians, presence of Russian troops and military equipment.[379] Also in early April, a number of Russian spetsnaz soldiers took pictures of themselves changing their military uniforms into "miner's battledress" used by the insurgents, and posted them on their VK pages, where they were picked up by Ukrainian media.[380] Another volunteer, Bondo Dorovskih, who left to Donbas to "fight fascism" gave a long interview to Russian media on his return, describing how he found himself "not in an army, but in a gang", involved in large-scale looting. He also described the methods used by Russian army to covertly deliver military equipment, people and ammunition to Donbas, as well as hostile attitude of the local civilian population.[381]

On 22 April 2015, the US Department of State accused the "combined Russian-separatist forces" of accumulating air defence systems, UAV along with command and control equipment in eastern Ukraine, and of conducting "complex" military training that "leaves no doubt that Russia is involved in the training". Russia is also reinforcing its military presence on the eastern border with Ukraine as well as near Belgorod which is close to Kharkiv.[382]

In May 2015, Reuters interviewed a number of Russian soldiers, some named and some speaking under condition of anonymity, who were serving in Donbas as truck drivers, crew of a T-72B3 tank and of a "Grad" launcher. Some of their colleagues resigned when asked to go to Donbas by their commanders, which was "not an easy decision" because the salary offered was between 20 and 60,000 rubles per month. The members of the "Grad" launcher crew confirmed they were shelling targets in Ukraine from Russian territory, around 2 km from the border.[383]

Allies of Boris Nemtsov released Putin. War in May 2015, a report on Russian involvement that he had been working on before his death.[384] Other Russian opposition activists announced that they had found fresh graves of members of a GRU special forces brigade that had operated in Ukraine.[385]

In May, two GRU soldiers, Alexander Alexandrov and Yevgeny Yerofeyev, were captured in a battle near Schastie and were later interviewed by press, admitting to being on active duty at the time of capture. Russian military command declared they left active service in December 2014, a claim that was repeated on Russian television by the wife of Alexandrov.[385][386] Consequently, Ukraine declared it would try them as terrorists, not prisoners of war, and a controversy developed in the Russian press regarding the status of the soldiers.[387] At the same time, Russian journalists found out that their families were strictly isolated from contacts with press and the captured soldiers.[388] While Alexandrov declared he would seek legal methods to confirm his status in Russia, military analyst Alexander Golts considers this impossible as special forces soldiers routinely sign contract termination declaration to be backdated in such a situation.[389]

Shortly afterward, a Russian military drone, "Forpost", was shot down near Avdeevka and recovered in good condition, with all the serial numbers and nameplates intact.[390][391] On 28 May 2015, the Atlantic Council released Hiding in Plain Sight: Putin's War in Ukraine, a report which they said provided "irrefutable evidence of direct Russian military involvement in eastern Ukraine".[392]

On 17 May 2015 two Russian soldiers of the 3rd Guards Spetsnaz Brigade were captured by Secret Service of Ukraine during a battle near town Shchastya (Lughansk oblast, Ukraine).[393] On 18 May they were transferred to Kyiv.[394] On 19 May a spokesman for the Russian Defence Ministry stated that the two named prisoners were not active servicemen when they were captured,[395] thus depriving the two Russians of their status as combatants and their protection under the Geneva Convention. The head of Ukraine's Security Service stated that the two men will be prosecuted for "terrorist acts".[395] On 20 May 2015 members of the OSCE mission to Ukraine spoke with the Russian soldiers in the hospital.[396] The OSCE 20 May 2015 report includes the following:

One of them said he had received orders from his military unit to go to Ukraine; he was to "rotate" after three months. Both of them said they had been to Ukraine "on missions" before.

In June 2015, Vice News reporter Simon Ostrovsky investigated the movements of Bato Dambaev, a Russian contract soldier from Buryatia, through a military camp in Rostov Oblast to Vuhlehirsk in Ukraine during the battle of Debaltseve and back to Buryatia, finding exact locations where Dambaev photographed himself, and came to a conclusion that Dambaev had fought in Ukraine while in active service in the Russian army.[397] With Russia refusing to allow the OSCE to expand its mission, OSCE observer Paul Picard stated that "We often see how Russian media outlets manipulate our statements. They say that we have not seen Russian troops crossing the borders. But that only applies to two border crossings. We have no idea what is going on at the others."[398]

In July 2015, Ukraine arrested a Russian officer, Vladimir Starkov, when his truck loaded with ammunition took a wrong turn and ended up at a Ukrainian checkpoint. On arrest, Starkov declared that he was a Russian military officer in active service and later explained that he was officially assigned to a Russian military unit in Novocherkassk, but immediately on arrival reassigned to join DPR forces.[399][400]

In September 2015 the United Nations Human Rights Office estimated that 8000 casualties had resulted from the conflict, noting that the violence had been "fuelled by the presence and continuing influx of foreign fighters and sophisticated weapons and ammunition from the Russian Federation."[401]

In November 2015, a Russian judge accepted a Russian citizen's claim that serving in the DNR militia was a mitigating circumstance.[402] On 17 December 2015, Putin admitted that Russian military intelligence officers were operating in Ukraine, stating "We never said there were not people there who carried out certain tasks including in the military sphere."[98]

In 2020 analysis of publicly available Russian railway traffic data (gdevagon.ru) indicated that in January 2015, period of especially heavy fighting, thousands of tons of cargo declared "high explosives" was sent by railway from various places in Russia into Uspenskaya, a small train station on a line crossing from Rostovskaya oblast' (Russia) into separatist-controlled part of Ukraine.[403]

2016 escalation

On 8 August 2016, Ukraine reported that Russia had increased its military presence along the Crimea demarcation line. Border crossings were then closed.[404] On 10 August, the Russian security agency FSB claimed it had prevented "Ukrainian terrorist attacks" and that two servicemen were killed in clashes in Armiansk (Crimea), adding that "several" Ukrainian and Russian citizens were detained.[405][406][407] Russian media reported that one of the killed soldiers was a commander of the Russian GRU, and later was buried in Simferopol.[408] The Ukrainian government denied that the incident took place,[409][410] and parallel to the incident on 9 August, a Ukrainian official claimed that a number of Russian soldiers had deserted but had not entered into Ukraine,[411] and that skirmishes broke out between Russian intelligence officers and border guards.[412] Russian President Putin accused Ukraine of turning to the "practice of terror".[413] Ukrainian President Poroshenko called the Russian version of events "equally cynical and insane".[414] The U.S. denied Russia's claims, with its ambassador to Ukraine (Geoffrey R. Pyatt) stating "The U.S. Government has seen nothing so far that corroborates Russian allegations of a "Crimea incursion".[415]قالب:Check quotation

Russia had used the allegation to engage in a rapid military build-up in Crimea,[416] followed by drills and military movement near the Ukrainian border.[416][417] Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko warned that Russia was preparing for a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.[418][419]

In September 2016, OSCE monitoring mission noticed military trucks with partially covered Russian number plates 26 km east from Donetsk.[420] Also in September a Russian soldier Denis Sidorov surrendered to the Ukrainian forces in Shirokaya Balka, revealing details of Russian leadership of the local DNR forces in the area.[421]

On 17 October 2016, the OSCE mission noted a minivan with "black licence plates with white lettering" which are used on military vehicles in Russia. A number of people in civilian and military camouflage were traveling on the vehicle.[422]

2018 Kerch Strait incident

The Kerch Strait offers a critical link for Ukraine's eastern ports in the Azov Sea to the Black Sea, which Russia has gained de facto control over in the aftermath of 2014. In 2017, Ukraine appealed to court of arbitration over the use of the strait, however, by 2018 Russia finished building a bridge over it, limiting the size of ships that can transit the strait, imposed new regulation and subsequently detained Ukrainian vessels on several occasions.

Tensions over the issue have been rising for months.[423] On 25 November 2018, three Ukrainian boats traveling from Odessa to Mariupol attempted to cross the Kerch Strait caused an incident, in which Russian warships fired on and seized the Ukrainian boats; 24 Ukrainian sailors were detained.[424][425] A day later on 26 November 2018, lawmakers in the Ukrainian parliament overwhelmingly backed the imposition of martial law along Ukraine's coastal regions and those bordering Russia in response to the firing upon and seizure of Ukrainian naval ships by Russia near the Crimean peninsula a day earlier. A total of 276 lawmakers in Kyiv passed the measure to take effect on 28 November 2018 and automatically expired after 30 days.[426]

2019–2020

More than 110 Ukrainian soldiers were killed in the conflict between Ukrainian government forces and Russian-backed separatists in 2019.[427]

In May 2019, the newly elected Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky took office promising to end the War in Donbas.[427]

In December 2019, Ukraine and pro-Russian separatists began swapping prisoners of war. Around 200 prisoners were exchanged on 29 December 2019.[428][429][430][431]

According to Ukrainian authorities, 50 Ukrainian soldiers were killed in the conflict between Ukrainian government forces and Russian-backed separatists in 2020.[432]

2021–2022 Russian military buildup