الديانة الشعبية الصينية

| الديانة الشعبية الصينية | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Qing dynasty painting of the Chinese pantheon | |||

| الصينية التقليدية | 中國民間信仰 | ||

| الصينية المبسطة | 中国民间信仰 | ||

| |||

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الديانة الشعبية الصينية |

|---|

|

| بوابة الديانة الشعبية الصينية |

الديانة الشعبية الصينية Chinese folk religion أو ديانة الهان الشعبية Han folk religion[1]، هي التقليد الديني لشعب الهان، والذي يشمل تبجيل قوى الطبيعة والأسلاف، طرد الأرواح من القوات الضارة، والايمان بالنظام العقلاني للطبيعة الذي يمكن أن يتأثر بالبشر وحكامهم وكذلك الأرواح والآلهة.[2] العبادة مكرسة لتعددية الآلهة والخالدين (神 shén)، التي يمكن أن تكون ظاهرة، سلوك بشري، أو الأسلاف. القصص المتعلقة بهذه الآلة مجموعة في الأساطير الصينية. بحلول القرن الحادي عشر (فترة سونگ) امتزجت هذه الممارسات بأفكار الكارما البوذية (التي يفعلها المرء) والميلاد من جديد، والتعاليم الاطوية المتعلقة بهرمية الآلهة، لتشكيل النظام الديني الشعبي الذي استمر بعدة طرق حتى يومنا هذا.[3]

للديانات الصينية مجموعة مرجعيات، أشكال محلية، خلفيات تأسياسية، وتقاليد طقسية وفلسفية متنوعة. بالرغم من هذا التنوع، إلا أن هناك جوهر مشترك يمكن تلخيصه على أنه أربعة مفاهيم لاهوتية وكونية وأخلاقية:[4] تيان (天)، السماء، المرجع المتعالي للمعنى الأخلاقي؛ qi (氣)، النفس أو الطاقة التي تحفز الكون؛ jingzu (敬祖)، تبجيل الأسلاف؛ وbao ying (報應)، المعاملة بالمثل الأخلاقية؛ جنباً إلى جنب مع اثنين من المفاهيم التقليدية للقدر والمعنى:[5] ming yun (命運)، المصير أو الازدهار الشخصي؛ ويوان فن (緣分)، "التزامن المصيري"،[6] الفرص الجيدة والسيئة والعلاقات المحتملة.[6]

After the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, governments and modernizing elites condemned 'feudal superstition' and opposed traditional religious practices which they believed conflicted with modern values. By the late 20th century, these attitudes began to change in both mainland China and Taiwan, and many scholars now view folk religion in a positive light.[7] In China, the revival of traditional religion has benefited from official interest in preserving traditional culture, such as Mazuism and the Sanyi teaching in Fujian,[8] Yellow Emperor worship,[9] and other forms of local worship, such as that of the Dragon King, Pangu or Caishen.[10]

Feng shui, acupuncture, and traditional Chinese medicine reflect this world view, since features of the landscape as well as organs of the body are in correlation with the five powers and yin and yang.[11]

التنوع

Chinese religions have a variety of sources, local forms, founder backgrounds, and ritual and philosophical traditions. Despite this diversity, there is a common core that can be summarised as four theological, cosmological, and moral concepts:[12] Tian, the transcendent source of moral meaning; qi, the breath or energy that animates the universe; ancestor veneration; and bao ying 'moral reciprocity'. With these, there are two traditional concepts of fate and meaning:[13] ming yun, the personal destiny or burgeoning; and yuanfen 'fateful coincidence',[14] good and bad chances and potential relationships.[14]

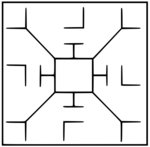

Yin and yang is the polarity that describes the order of the universe,[15] held in balance by the interaction of principles of extension (神; shén; 'spirit') and returning (鬼; guǐ; 'ghost'),[16] with yang ('act') usually preferred over yin ('receptiveness') in common religion.[17] The taijitu and bagua are common diagrams representing the forces of nature, and the power that deities like Zhong Kui wield.[18] Ling is the medium of the two states and the inchoate order of creation.[17]

المصطلحات

The Chinese language historically has not had a concept or overarching term for "religion". In English, the terms 'popular religion' or 'folk religion' have long been used to mean local religious life. In Chinese academic literature and common usage 'folk religion' (民間宗教; mínjiān zōngjiào) refers to specific organised folk religious sects.[19]

Contemporary academic study of traditional cults and the creation of a government agency that gave legal status to this religion [20] have created proposals to formalise names and deal more clearly with folk religious sects and help conceptualise research and administration.[21] Terms that have been proposed include 'Chinese native religion' (民俗宗教; mínsú zōngjiào), 'Chinese ethnic religion' (民族宗教; mínzú zōngjiào),[22] or 'Chinese religion' (中華教; zhōnghuájiào) viewed as comparable to the usage of the term "Hinduism" for Indian religion.[23] In Malaysia, reports the scholar Tan Chee-Beng, Chinese do not have a definite term for their traditional religion, which is not surprising because "the religion is diffused into various aspects of Chinese culture". They refer to their religion as 'Buddha worship' (拜佛; bàifó) or 'spirit worship' (拜神; bàishén), which prompted Alan J. A. Elliott to suggest the term قالب:Zht. Tan however, comments that is not the way the Chinese refer to their religion, which in any case includes worship of ancestors, not shen, and suggests it is logical to use "Chinese Religion".[24] Shenxianism قالب:Zht, literally 'religion of deities and immortals',[25] is a term partly inspired by Elliott's "shenism" neologism.[26]

During the late Qing dynasty, scholars Yao Wendong and Chen Jialin used the term shenjiao not referring to Shinto as a definite religious system, but to local shin beliefs in Japan.[27] Other terms are 'folk cults' (民間崇拜; mínjiān chóngbài), 'spontaneous religion' (自發宗教; zìfā zōngjiào), 'lived religion' (生活宗教; shēnghuó zōngjiào), 'local religion' (地方宗教; dìfāng zōngjiào), and 'diffused religion' (分散性宗教; fēnsàn xìng zōngjiào).[28] 'Folk beliefs' (民間信仰; mínjiān xìnyǎng),[29] is a seldom used term taken by scholars in colonial Taiwan from Japanese during Japan's occupation (1895–1945). It was used between the 1990s and the early 21st century among mainland Chinese scholars.[30]

Shendao (神道; shéndào; 'the Way of the Gods') is a term already used in the I Ching referring to the divine order of nature.[31] Around the time of the spread of Buddhism during the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), it was used to distinguish the indigenous ancient religion from the imported religion. Ge Hong used it in his Baopuzi as a synonym for Taoism.[32] The term was subsequently adopted in Japan in the 6th century as Shindo, later Shinto, with the same purpose of identification of the Japanese indigenous religion.[33][34] In the 14th century, the Hongwu Emperor (Taizu of the Ming dynasty, 1328–1398) used the term "Shendao" clearly identifying the indigenous cults, which he strengthened and systematised.[35]

"Chinese Universism"—not in the sense of "universalism" as in "a system of universal application", as that is Tian in Chinese thought—is a coinage of Jan Jakob Maria de Groot that refers to the metaphysical perspective that lies behind the Chinese religious tradition. De Groot calls Chinese Universism "the ancient metaphysical view that serves as the basis of all classical Chinese thought. ... In Universism, the three components of integrated universe—understood epistemologically, 'heaven, earth and man', and understood ontologically, 'Taiji (the great beginning, the highest ultimate), yin and yang'—are formed".[36]

In 1931, Hu Shih argued that: "Two great religions have played tremendously important roles throughout Chinese history. One is Buddhism which came to China probably before the Christian era but which began to exert nation-wide influence only after the third century A.D. The other great religion has had no generic name, but I propose to call it Siniticism. It is the native ancient religion of the Han Chinese people: it dates back to time immemorial, over 10,000 years old, and includes all such later phases of its development as Moism, Confucianism (as a state religion), and all the various stages of the Taoist religion."[37]

Attributes

Contemporary Chinese scholars have identified what they consider the essential features of the Chinese indigenous religion: according to Chen Xiaoyi (陳曉毅) local indigenous religion is the crucial factor for a harmonious 'religious ecology' (宗教生態), that is the balance of forces in a given community.[38] Han Bingfang (韓秉芳) has called for a rectification of names: distorted names are 'superstitious activities' (迷信活動) or 'feudal superstition' (封建迷信), that were derogatorily applied to the indigenous religion by leftist policies.[مطلوب توضيح] Christian missionaries also used the label 'feudal superstition' as propaganda to undermine what they saw as religious competitition.[39] Han calls for the acknowledgment of the ancient Chinese religion for what it really is, the 'core and soul of popular culture' (俗文化的核心與靈魂).[40]

According to Chen Jinguo (陳進國), the ancient Chinese religion is a core element of Chinese 'cultural and religious self-awareness' (文化自覺,信仰自覺).[39] He has proposed a theoretical definition of Chinese indigenous religion in a 'trinity' (三位一體), apparently inspired to Tang Chun-i's thought:[41]

- Substance (體; tǐ): religiousness (宗教性; zōngjiào xìng);

- Function (用; yòng): folkloricity (民俗性; mínsú xìng);

- Quality (相; xiàng): Chineseness (中華性; zhōnghuá xìng).

Characteristics

Diversity and unity

Ancient Chinese religious practices are diverse, varying from province to province and even from one village to another, for religious behaviour is bound to local communities, kinship, and environments. In each setting, institution and ritual behaviour assumes highly organised forms. Temples and the gods in them acquire symbolic character and perform specific functions involved in the everyday life of the local community.[42] Local religion preserves aspects of naturalistic beliefs such as totemism,[43] animism, and shamanism.[44]

Ancient Chinese religion pervades all aspects of social life. Many scholars, following the lead of sociologist C. K. Yang, see the ancient Chinese religion deeply embedded in family and civic life, rather than expressed in a separate organizational structure like a "church", as in the West.[45]

Deity or temple associations and lineage associations, pilgrimage associations and formalized prayers, rituals and expressions of virtues, are the common forms of organization of Chinese religion on the local level.[42] Neither initiation rituals nor official membership into a church organization separate from one person's native identity are mandatory in order to be involved in religious activities.[42] Contrary to institutional religions, Chinese religion does not require "conversion" for participation.[45]

The prime criterion for participation in the ancient Chinese religion is not "to believe" in an official doctrine or dogma, but "to belong" to the local unit of an ancient Chinese religion, that is the "association", the "village" or the "kinship", with their gods and rituals.[42] Sociologist Richard Madsen describes the ancient Chinese religion, adopting the definition of Tu Weiming,[46] as characterized by "immanent transcendence" grounded in a devotion to "concrete humanity", focused on building moral community within concrete humanity.[47]

Inextricably linked to the aforementioned question to find an appropriate "name" for the ancient Chinese religion, is the difficulty to define it or clearly outline its boundaries. Old sinology, especially Western, tried to distinguish "popular" and "élite" traditions (the latter being Confucianism and Taoism conceived as independent systems). Chinese sinology later adopted another dichotomy which continues in contemporary studies, distinguishing "folk beliefs" (minjian xinyang) and "folk religion" (minjian zongjiao), the latter referring to the doctrinal sects.[48]

Many studies have pointed out that it is impossible to draw clear distinctions, and, since the 1970s, several sinologists[من؟] swung to the idea of a unified "ancient Chinese religion" that would define the Chinese national identity, similarly to Hindu Dharma for India and Shinto for Japan. Other sinologists who have not espoused the idea of a unified "national religion" have studied Chinese religion as a system of meaning, or have brought further development in C. K. Yang's distinction between "institutional religion" and "diffused religion", the former functioning as a separate body from other social institutions, and the latter intimately part of secular social institutions.[49]

نظرة عامة

التاريخ

Prehistory

In the beginning of Chinese civilization, "[t]he most honored members of the family were...the ancestors", who lived in a spiritual world between heaven and earth and beseeched the gods of heaven and earth to influence the world to benefit their family.[50]

الصين الامبراطورية

By the Han dynasty, the ancient Chinese religion mostly consisted of people organising into shè (Chinese: 社 ["group", "body", local community altars]) who worshipped their godly principle.[بحاجة لمصدر] In many cases the "lord of the she" was the god of the earth, and in others a deified virtuous person (xiān Chinese: 仙, "immortal"). Some cults such as that of Liu Zhang, a king in what is today Shandong, date back to this period.[51]

From the 3rd century on by the Northern Wei, accompanying the spread of Buddhism in China, strong influences from the Indian subcontinent penetrated the ancient Chinese indigenous religion. A cult of Ganesha (Chinese: 象頭神 Xiàngtóushén, "Elephant-Head God") is attested in the year 531.[52] Pollination from Indian religions included processions of carts with images of gods or floats borne on shoulders, with musicians and chanting.[51]

القرن 19 و20

The ancient Chinese religion was subject to persecution in the 19th and 20th centuries. Many ancient temples were destroyed during the Taiping Rebellion and the Boxer Rebellion in the late 1800s.[53] After the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 "most temples were turned to other uses or were destroyed, with a few changed into schools".[54] During the Japanese invasion of China between 1937 and 1945 many temples were used as barracks by soldiers and destroyed in warfare.[53][55]

In the 19th century in the Guangdong region, monotheism, likely of a henotheistic and/or monolatrous character in at least some contexts and locations, was well-known and popular in Chinese folk religion.[56]

In the past, popular cults were regulated by imperial government policies, promoting certain deities while suppressing others.[57] In the 20th century, with the decline of the Qing dynasty, increasing urbanisation and Western influence, the issue for the new intellectuals who looked to the West was no longer controlling unauthorised worship of unregistered gods but the ancient Chinese religion itself, which they perceived as an issue halting modernisation.[58]

By 1899, 400 syncretic temples that combined folk religion elements and gods with Buddhist, Taoist, and/or Confucianist gods existed on the American West Coast alone.[59]

In 1904, a reform policy of the late Qing dynasty provided that schools would be built through the confiscation of temple property.[58] "Anti-superstition" campaigns followed. The Nationalist government of the Republic of China intensified the suppression of the ancient Chinese religion with the 1928 "Standards for retaining or abolishing gods and shrines"; the policy attempted to abolish the cults of all gods with the exception of ancient great human heroes and sages such as the Yellow Emperor, Yu the Great, Guan Yu, Sun Tzu, Nuwa, Mazu, Guanyin, Xuanzang, Kūkai, Buddha, Budai, Bodhidharma, Lao Tzu, and Confucius.[60]

These policies were the background for those implemented by Communist Party after winning the Chinese Civil War and taking power in 1949.[60] The Cultural Revolution, between 1966 and 1976 of the Chairman Mao period in the PRC, was the most serious and last systematic effort to destroy the ancient Chinese religion, while in Taiwan the ancient Chinese religion was very well-preserved but controlled by Republic of China (Taiwan) president Chiang Kai-Shek during his Chinese Cultural Renaissance to counter the Cultural Revolution.[53][60]

After 1978 the ancient Chinese religion started to rapidly revive in China,[61][62] with millions of temples being rebuilt or built from scratch.[62] Since the 1980s the central government moved to a policy of benign neglect or wu wei (Chinese: 無為) in regard to rural community life, and the local government's new regulatory relationship with local society is characterised by practical mutual dependence; these factors have given much space for popular religion to develop.[62] In recent years, in some cases, local governments have taken an even positive and supportive attitude towards indigenous religion in the name of promoting cultural heritage.[62][63]

Instead of signaling the demise of traditional ancient religion, China and Taiwan's economic and technological industrialization and development has brought a spiritual renewal.[64]

النصوص

Ancient Chinese religion draws from a vast heritage of sacred books, which according to the general worldview treat cosmology, history and mythology, mysticism and philosophy, as aspects of the same thing. Historically, the revolutionary shift toward a preference for textual transmission and text-based knowledge over long-standing oral traditions first becomes detectable in the 1st century CE.[65] The spoken word, however, never lost its power. Rather than writing replacing the power of the spoken word, both existed side by side. Scriptures had to be recited and heard in order to be efficacious, and the limitations of written texts were acknowledged particularly in Taoism and folk religion.[66]

There are the classic books (Chinese: 經; pinyin: jīng; lit. 'warp') such as the Confucian canon including the "Four Books and Five Classics" (Chinese: 《四書五經》; pinyin: sìshū wǔjīng) and the "Classic of Filial Piety" (Chinese: 《孝經》; pinyin: xiàojīng), then there are the Mozi (Mohism), the Huainanzi, the Shizi and the Xunzi. The "Interactions Between Heaven and Mankind" (Chinese: 《天人感應》; pinyin: tiānrén gǎnyìng) is a set of Confucianised doctrines compiled in the Han dynasty by Dong Zhongshu, discussing politics in accordance with a personal Tian of whom mankind is viewed as the incarnation.

Taoism has a separate body of philosophical, theological and ritual literature, including the fundamental Daodejing (Chinese: 《道德經》; lit. 'Book of the Way and its Virtue'), the Daozang (Taoist Canon), the Liezi and the Zhuangzi, and a great number of other texts either included or not within the Taoist Canon. Vernacular literature and the folk religious sects have produced a great body of popular mythological and theological literature, the baojuan (Chinese: 寶卷; lit. 'precious scrolls').

Recent discovery of ancient books, such as the "Guodian texts" in the 1990s and the Huangdi sijing (Chinese: 《黃帝四經》; lit. 'Four Books of the Yellow Emperor') in the 1970s, has given rise to new interpretations of the ancient Chinese religion and new directions in its post-Maoist renewal. Many of these books overcome the dichotomy between Confucian and Taoist traditions.[67] The Guodian texts include, among others, the Taiyi Shengshui (Chinese: 《太一生水》; lit. 'The Great One Gives Birth to Water'). Another book attributed to the Yellow Emperor is the Huangdi yinfujing (Chinese: 《黃帝陰符經》; lit. 'Yellow Emperor's Book of the Hidden Symbol').

Classical books of mythology include the "Classic of Mountains and Seas" (Chinese: 《山海經》; pinyin: shānhǎijīng), the "Record of Heretofore Lost Works" (Chinese: 《拾遺記; pinyin: shíyíjì), "The Peach Blossom Spring" (Chinese: 《桃花源記》; pinyin: táohuāyuánjì), the "Investiture of the Gods" (Chinese: 《封神演義》; pinyin: fēngshén yǎnyì), and the "Journey to the West" (Chinese: 《西遊記》; pinyin: xīyóujì) among others.

المفاهيم الأساسية لللاهوت وعلم الكون

Fan and Chen summarise four spiritual, cosmological, and moral concepts:[12] Tian (Chinese: 天), Heaven, the source of moral meaning; qi (Chinese: 氣), the breath or substance of which all things are made; the practice of jingzu (Chinese: 敬祖), the veneration of ancestors; bao ying (Chinese: 報應), moral reciprocity.

تيان، ولي وتشي

"Tian is dian 顛 ("top"), the highest and unexceeded. It derives from the characters yi 一, "one", and da 大, "big"."[note 1]

Confucians, Taoists, and other schools of thought share basic concepts of Tian. Tian is both the physical heavens, the home of the sun, moon, and stars, and also the home of the gods and ancestors. Tian by extension is source of moral meaning, as seen in the political principle, the Mandate of Heaven, which holds that Tian, responding to human virtue, grants the imperial family the right to rule and withdraws it when the dynasty declines in virtue.[76] This creativity or virtue (de) in humans is the potentiality to transcend the given conditions and act wisely and morally.[77] Tian is therefore both transcendent and immanent.[77]

Tian is defined in many ways, with many names, the most widely known being Tàidì Chinese: 太帝 (the "Great Deity") and Shàngdì Chinese: 上帝 (the "Primordial Deity").[note 2] The concept of Shangdi is especially rooted in the tradition of the Shang dynasty, which gave prominence to the worship of ancestral gods and cultural heroes. The "Primordial Deity" or "Primordial Emperor" was considered to be embodied in the human realm as the lineage of imperial power.[84] Di (Chinese: 帝) is a term meaning "deity" or "emperor" (Latin: imperator, verb im-perare; "making from within"), used either as a name of the primordial god or as a title of natural gods,[85] describing a principle that exerts a fatherly dominance over what it produces.[86] With the Zhou dynasty, which preferred a religion focused on gods of nature, Tian became a more abstract and impersonal idea of God.[84] A popular representation is the Jade Deity (Chinese: 玉帝 Yùdì) or Jade Emperor (Chinese: 玉皇 Yùhuáng)[note 3] originally formulated by Taoists.[90] According to classical theology he manifests in five primary forms (Chinese: 五方上帝 Wǔfāng Shàngdì, "Five Forms of the Highest Deity").

The qi Chinese: 气 is the breath or substance of which all things are made, including inanimate matter, the living beings, thought and gods.[91][92] It is the continuum energy—matter.[93] Stephen F. Teiser (1996) translates it as "stuff" of "psychophysical stuff".[92] Neo-Confucian thinkers such as Zhu Xi developed the idea of li Chinese: 理, the "reason", "order" of Heaven, that is to say the pattern through which the qi develops, that is the polarity of yin and yang.[94][95] In Taoism the Tao Chinese: 道 ("Way") denotes in one concept both the impersonal absolute Tian and its order of manifestation (li).

Yin, yang, gui, and shen

Yin (陰; yīn) and yang (陽; yáng), whose root meanings respectively are 'shady' and 'sunny', or 'dark' and 'light', are modes of manifestation of the qi, not material things in themselves. Yin is the qi in its dense, dark, sinking, wet, condensing mode; yang denotes the light, and the bright, rising, dry, expanding modality. Described as Taiji (the 'Great Pole'), they represent the polarity and complementarity that enlivens the cosmos.[95] They can also be conceived as 'disorder' and 'order', 'activity' or 'passivity', with action (yang) usually preferred over receptiveness (yin).[17]

The concept of shen (神; shén; cognate of 申; shēn 'extending', 'expanding'[96]) is translated as 'gods' or 'spirits'. There are shen of nature; gods who were once people, such as the warrior Guan Yu; household gods, such as the Stove God; as well as ancestral gods (zu or zuxian).[97] In the domain of humanity the shen is the psyche, or the power or agency within humans.[98] They are intimately involved in the life of this world.[98] As spirits of stars, mountains and streams, shen exert a direct influence on things, making phenomena appear and things grow or extend themselves.[98] An early Chinese dictionary, the Shuowen Jiezi by Xu Shen, explains that they "are the spirits of Heaven" and they "draw out the ten thousand things".[98] As forces of growth the gods are regarded as yang, opposed to a yin class of entities called gui (鬼; guǐ; cognate of 歸; guī 'return', 'contraction'),[96] chaotic beings.[99] A disciple of Zhu Xi noted that "between Heaven and Earth there is no thing that does not consist of yin and yang, and there is no place where yin and yang are not found. Therefore, there is no place where gods and spirits do not exist".[99] The dragon is a symbol of yang, the principle of generation.[84]

In Taoist and Confucian thought, the supreme God and its order and the multiplicity of shen are identified as one and the same.[100] In the Ten Wings, a commentary to the I Ching, it is written that "one yin and one yang are called the Tao ... the unfathomable change of yin and yang is called shen".[100] In other texts, with a tradition going back to the Han dynasty, the gods and spirits are explained to be names of yin and yang, forces of contraction and forces of growth.[100]

While in popular thought they have conscience and personality,[101] Neo-Confucian scholars tended to rationalise them.[102] Zhu Xi wrote that they act according to the li.[96] Zhang Zai wrote that they are "the inherent potential (liang neng) of the two ways of qi".[103] Cheng Yi said that they are "traces of the creative process".[96] Chen Chun wrote that shen and gui are expansions and contractions, going and coming, of yin and yang—qi.[96]

Hun and po, and zu and xian

Like all things in matter, the human soul is characterised by a dialectic of yang and yin. These correspond to the hun and po (Chinese: 魂魄) respectively. The hun is the traditionally "masculine", yang, rational soul or mind, and the po is the traditionally "feminine", yin, animal soul that is associated with the body.[104] Hun (mind) is the soul (shen) that gives a form to the vital breath (qi) of humans, and it develops through the po, stretching and moving intelligently in order to grasp things.[105] The po is the soul (shen) which controls the physiological and psychological activities of humans,[106] while the hun, the shen attached to the vital breath (qi), is the soul (shen) that is totally independent of corporeal substance.[106] The hun is independent and perpetual, and as such it never allows itself to be limited in matter.[106][note 5] Otherwise said, the po is the "earthly" (di) soul that goes downward, while the hun is the "heavenly" (tian) soul that moves upward.[98]

To extend life to its full potential the human shen must be cultivated, resulting in ever clearer, more luminous states of being.[16] It can transform in the pure intelligent breath of deities.[106] In the human psyche there's no distinction between rationality and intuition, thinking and feeling: the human being is xin (Chinese: 心), mind-heart.[93] With death, while the po returns to the earth and disappears, the hun is thought to be pure awareness or qi, and is the shen to whom ancestral sacrifices are dedicated.[107]

The shen of men who are properly cultivated and honoured after their death are upheld ancestors and progenitors (zuxian Chinese: 祖先 or zu Chinese: 祖).[97] When ancestries aren't properly cultivated the world falls into disruption, and they become gui.[97] Ancestral worship is intertwined with totemism, as the earliest ancestors of an ethnic lineage are often represented as animals or associated to them.[43][108]

Ancestors are means of connection with the Tian, the primordial god which does not have form.[43] As ancestors have form, they shape the destiny of humans.[43] Ancestors who have had a significant impact in shaping the destiny of large groups of people, creators of genetic lineages or spiritual traditions, and historical leaders who have invented crafts and institutions for the wealth of the Chinese nation (culture heroes), are exalted among the highest divine manifestations or immortal beings (xian Chinese: 仙).[109]

In fact, in the Chinese tradition there is no distinction between gods (shen) and immortal beings (xian), transcendental principles and their bodily manifestations.[110] Gods can incarnate with a human form and human beings can reach higher spiritual states by the right way of action, that is to say by emulating the order of Heaven.[111] Humans are considered one of the three aspects of a trinity (Chinese: 三才 Sāncái, "Three Powers"),[112] the three foundations of all being; specifically, men are the medium between Heaven that engenders order and forms and Earth which receives and nourishes them.[112] Men are endowed with the role of completing creation.[112][note 6]

Bao ying and ming yun

The Chinese traditional concept of bao ying ("reciprocity", "retribution" or "judgement"), is inscribed in the cosmological view of an ordered world, in which all manifestations of being have an allotted span (shu) and destiny,[114] and are rewarded according to the moral-cosmic quality of their actions.[115] It determines fate, as written in Zhou texts: "on the doer of good, heaven sends down all blessings, and on the doer of evil, he sends down all calamities" (Chinese: 書經•湯誥).[116]

The cosmic significance of bao ying is better understood by exploring other two traditional concepts of fate and meaning:[13]

- Ming yun (Chinese: 命運), the personal destiny or given condition of a being in his world, in which ming is "life" or "right", the given status of life, and yun defines both "circumstance" and "individual choice"; ming is given and influenced by the transcendent force Tian (Chinese: 天), that is the same as the "divine right" (tianming) of ancient rulers as identified by Mencius.[13] Personal destiny (ming yun) is thus perceived as both fixed (as life itself) and flexible, open-ended (since the individual can choose how to behave in bao ying).[13]

- Yuan fen (Chinese: 緣分), "fateful coincidence",[14] describing good and bad chances and potential relationships.[14] Scholars K. S. Yang and D. Ho have analysed the psychological advantages of this belief: assigning causality of both negative and positive events to yuan fen reduces the conflictual potential of guilt and pride, and preserves social harmony.[117]

Ming yun and yuan fen are linked, because what appears on the surface to be chance (either positive or negative), is part of the deeper rhythm that shapes personal life based on how destiny is directed.[115] Recognising this connection has the result of making a person responsible for his or her actions:[116] doing good for others spiritually improves oneself and contributes to the harmony between men and environmental gods and thus to the wealth of a human community.[118]

These three themes of the Chinese tradition—moral reciprocity, personal destiny, fateful coincidence—are completed by a fourth notion:[119]

- Wu (Chinese: 悟), "awareness" of bao ying. The awareness of one's own given condition inscribed in the ordered world produces responsibility towards oneself and others; awareness of yuan fen stirs to respond to events rather than resigning.[119] Awareness may arrive as a gift, often unbidden, and then it evolves into a practice that the person intentionally follows.[119]

As part of the trinity of being (the Three Powers), humans are not totally submissive to spiritual force.[113] While under the sway of spiritual forces, humans can actively engage with them, striving to change their own fate to prove the worth of their earthly life.[113] In the Chinese traditional view of human destiny, the dichotomy between "fatalism" and "optimism" is overcome; human beings can shape their personal destiny to grasp their real worth in the transformation of the universe, seeing their place in the alliance with the gods and with Heaven to surpass the constraints of the physical body and mind.[113]

Ling and xianling—holy and numen

In Chinese religion the concept of ling (Chinese: 靈) is the equivalent of holy and numen.[120] Shen in the meaning of "spiritual" is a synonym.[99] The Yijing states that "spiritual means not measured by yin and yang".[99] Ling is the state of the "medium" of the bivalency (yin-yang), and thus it is identical with the inchoate order of creation.[17] Things inspiring awe or wonder because they cannot be understood as either yin or yang, because they cross or disrupt the polarity and therefore cannot be conceptualised, are regarded as numinous.[99] Entities possessing unusual spiritual characteristics, such as albino members of a species, beings that are part animal part human, or people who die in unusual ways such as suicide or on battlefields, are considered numinous.[99]

The notion of xian ling (Chinese: 顯靈), variously translated as "divine efficacy, virtue" or the "numen", is important for the relationship between people and gods.[121] It describes the manifestation, activity, of the power of a god (Chinese: 靈氣 ling qi, "divine energy" or "effervescence"), the evidence of the holy.[122]

The term xian ling may be interpreted as the god revealing their presence in a particular area and temple,[123] through events that are perceived as extraordinary, miraculous.[123] Divine power usually manifests in the presence of a wide public.[123] The "value" of human deities (xian) is judged according to their efficacy.[124] The perceived effectiveness of a deity to protect or bless also determines how much they should be worshipped, how big a temple should be built in their honour, and what position in the broader pantheon they would attain.[124]

Zavidovskaya (2012) has studied how the incentive of temple restorations since the 1980s in northern China was triggered by numerous alleged instances of gods becoming "active" and "returning", reclaiming their temples and place in society.[123] She mentions the example of a Chenghuang Temple in Yulin, Shaanxi, that was turned into a granary during the Cultural Revolution; it was restored to its original function in the 1980s after seeds stored within were always found to have rotted. This phenomenon, which locals attributed to the god Chenghuang, was taken a sign to empty his residence of grain and allow him back in.[123] The ling qi, divine energy, is believed to accumulate in certain places, temples, making them holy.[123] Temples with a longer history are considered holier than newly built ones, which still need to be filled by divine energy.[123]

Another example Zavidovskaya cites is the cult of the god Zhenwu in Congluo Yu, Shanxi;[125] the god's temples were in ruins and the cult inactive until the mid-1990s, when a man with terminal cancer, in his last hope prayed (bai Chinese: 拜) to Zhenwu. The man began to miraculously recover each passing day, and after a year he was completely healed.[125] As thanksgiving, he organised an opera performance in the god's honour.[125] A temporary altar with a statue of Zhenwu and a stage for the performance were set up in an open space at the foot of a mountain.[125] During the course of the opera, large white snakes appeared, passive and unafraid of the people, seemingly watching the opera; the snakes were considered by locals to be incarnations of Zhenwu, come to watch the opera held in his honour.[125]

Within temples, it is common to see banners bearing the phrase "if the heart is sincere, the god will reveal their power" (Chinese: 心誠神靈 xin cheng shen ling).[126] The relationship between people and gods is an exchange of favour.[126] This implies the belief that gods respond to the entreaties of the believer if their religious fervour is sincere (cheng xin Chinese: 誠心).[126] If a person believes in the god's power with all their heart and expresses piety, the gods are confident in their faith and reveal their efficacious power.[126] At the same time, for faith to strengthen in the devotee's heart, the deity has to prove their efficacy.[126] In exchange for divine favours, a faithful honours the deity with vows (huan yuan Chinese: 還願 or xu yuan Chinese: 許願), through individual worship, reverence and respect (jing shen Chinese: 敬神).[126]

The most common display of divine power is the cure of diseases after a believer piously requests aid.[123] Another manifestation is granting a request of children.[123] The deity may also manifest through mediumship, entering the body of a shaman-medium and speaking through them.[123] There have been cases of people curing illnesses "on behalf of a god" (ti shen zhi bing Chinese: 替神治病).[125] Gods may also speak to people when they are asleep (tuomeng Chinese: 託夢).[123]

التصنيف السوسيولوجي

أنواع الديانات العرقية-الأصلية

عبادة الآلهة المحلية والقومية

ديانة الأسلاف

الطرائق الفلسفية والطقوس

التقاليد الشامانية

الكونفشيوسية، الطاوية ورتب القادة الدينيين

الطوائف الدينية المنظمة

التعاليم التياندية

الويشينية

التنوعات الجغرافيةوالعرقية

الانقسام الشمالي والجنوبي

الديانات الأصلية "الطاوية" للأقليات العرقية

الخصائص

| "Chief Star pointing the Dipper" 魁星點斗 Kuíxīng diǎn Dòu | |

|---|---|

| |

| Kuixing ("Chief Star"), the god of exams, composed of the characters describing the four Confucian virtues (Sìde 四德), standing on the head of the ao (鰲) turtle (an expression for coming first in the examinations), and pointing at the Big Dipper (斗)".[note 9] |

نظرية التسلسل الهرمي والألوهية

الآلهة والمخلدون

عبادة الإلهة الأم

العبادة وطرق الممارسات الدينية

القرابين

الشكر والاستبدال

شعائر العبور

دور العبادة

شبكات المعابد والتجمعات

الديموغرافيا

البر الصيني وتايوان

اقتصاد المعابد والطقوس

الصينيون وراء البحار

انظر أيضاً

- الآلهة والمخلدون الصينيون

- Chinese ritual mastery traditions

- شامانية صينية

- لاهوت صيني

- كونفشيوسية—كنيسة كونفشيوسية

- الديانة الشعبية الصينية الشمالية

- Nuo folk religion

- الطاوية

حسب المكان

- [[المعابد الصينية في كلكتا]

- الشامانية في جنوب شرق آسيا

تقاليد وطنية مشابهة أخرى

ديانات عرقية صينية-تبتية أخرى

ديانات عرقية أخرى ليست صينية تبتية موجودة في الصين

مقالات أخرى

الهوامش

- ^ The graphical etymology of Tian 天 as "Great One" (Dà yī 大一), and the phonetical etymology as diān 顛, were first recorded by Xu Shen.[69] John C. Didier in In and Outside the Square (2009) for the Sino-Platonic Papers discusses different etymologies which trace the character Tian 天 to the astral square or its ellipted forms, dīng 口, representing the north celestial pole (pole star and Big Dipper revolving around it; historically a symbol of the absolute source of the universal reality in many cultures), which is the archaic (Shang) form of dīng 丁 ("square").[70] Gao Hongjin and other scholars trace the modern word Tian to the Shang pronunciation of 口 dīng (that is *teeŋ).[70] This was also the origin of Shang's Dì 帝 ("Deity"), and later words meaning something "on high" or "top", including 頂 dǐng.[70] The modern graph for Tian 天 would derive from a Zhou version of the Shang archaic form of Dì 帝 (from Shang oracle bone script[71] →

, which represents a fish entering the astral square); this Zhou version represents a being with a human-like body and a head-mind informed by the astral pole (→

, which represents a fish entering the astral square); this Zhou version represents a being with a human-like body and a head-mind informed by the astral pole (→  ).[70] Didier furtherly links the Chinese astral square and Tian or Di characters to other well-known symbols of God or divinity as the northern pole in key ancient cultural centres: the Harappan and Vedic-Aryan spoked wheels,[72] crosses and hooked crosses (Chinese wàn 卍/卐),[73] and the Mesopotamian Dingir

).[70] Didier furtherly links the Chinese astral square and Tian or Di characters to other well-known symbols of God or divinity as the northern pole in key ancient cultural centres: the Harappan and Vedic-Aryan spoked wheels,[72] crosses and hooked crosses (Chinese wàn 卍/卐),[73] and the Mesopotamian Dingir  .[74] Jixu Zhou (2005), also in the Sino-Platonic Papers, connects the etymology of Dì 帝, Old Chinese *Tees, to the Indo-European Deus, God.[75]

.[74] Jixu Zhou (2005), also in the Sino-Platonic Papers, connects the etymology of Dì 帝, Old Chinese *Tees, to the Indo-European Deus, God.[75]

- ^ Tian, besides Taidi ("Great Deity") and Shangdi ("Highest Deity"), Yudi ("Jade Deity"), Shen Chinese: 神 ("God"), and Taiyi ("Great Oneness") as identified as the ladle of the Tiānmén Chinese: 天門 ("Gate of Heaven", the Big Dipper),[78] is defined by many other names attested in the Chinese literary, philosophical and religious tradition:[79]

- Tiānshén Chinese: 天神, the "God of Heaven", interpreted in the Shuowen jiezi (Chinese: 說文解字) as "the being that gives birth to all things";

- Shénhuáng Chinese: 神皇, "God the King", attested in Taihong ("The Origin of Vital Breath");

- Tiāndì Chinese: 天帝, the "Deity of Heaven" or "Emperor of Heaven".

- A popular Chinese term is Lǎotiānyé (Chinese: 老天爺), "Old Heavenly Father".

- Tiānzhǔ 天主—the "Lord of Heaven": In "The Document of Offering Sacrifices to Heaven and Earth on the Mountain Tai" (Fengshan shu) of the Records of the Grand Historian it is used as the title of the first God from whom all the other gods derive.[80]

- Tiānhuáng 天皇—the "August Personage of Heaven": In the "Poem of Fathoming Profundity" (Si'xuan fu), transcribed in "The History of the Later Han Dynasty" (Hou Han shu), Zhang Heng ornately writes: «I ask the superintendent of the Heavenly Gate to open the door and let me visit the King of Heaven at the Jade Palace»;[81]

- Tiānwáng 天王—the "King of Heaven" or "Monarch of Heaven".

- Tiāngōng 天公—the "Duke of Heaven" or "General of Heaven";[82]

- Tiānjūn 天君—the "Prince of Heaven" or "Lord of Heaven";[82]

- Tiānzūn 天尊—the "Heavenly Venerable", also a title for high gods in Taoist theologies;[81]

- Huáng Tiān Chinese: 皇天 —"Yellow Heaven" or "Shining Heaven", when it is venerated as the lord of creation;

- Hào Tiān Chinese: 昊天—"Vast Heaven", with regard to the vastness of its vital breath (qi);

- Mín Tiān Chinese: 昊天—"Compassionate Heaven" for it hears and corresponds with justice to the all-under-heaven;

- Shàng Tiān Chinese: 上天—"Highest Heaven" or "First Heaven", for it is the primordial being supervising all-under-heaven;

- Cāng Tiān Chinese: 蒼天—"Deep-Green Heaven", for it being unfathomably deep.

- ^ The characters yu 玉 (jade), huang 皇 (emperor, sovereign, august), wang 王 (king), as well as others pertaining to the same semantic field, have a common denominator in the concept of gong 工 (work, art, craft, artisan, bladed weapon, square and compass; gnomon, "interpreter") and wu Chinese: 巫 (shaman, medium)[87] in its archaic form

, with the same meaning of wan 卍 (swastika, ten thousand things, all being, universe).[88] The character dì Chinese: 帝 is rendered as "deity" or "emperor" and describes a divine principle that exerts a fatherly dominance over what it produces.[86] A king is a man or an entity who is able to merge himself with the axis mundi, the centre of the universe, bringing its order into reality. The ancient kings or emperors of the Chinese civilisation were shamans or priests, that is to say mediators of the divine rule.[89] The same Western terms "king" and "emperor" traditionally meant an entity capable to embody the divine rule: king etymologically means "gnomon", "generator", while emperor means "interpreter", "one who makes from within".

, with the same meaning of wan 卍 (swastika, ten thousand things, all being, universe).[88] The character dì Chinese: 帝 is rendered as "deity" or "emperor" and describes a divine principle that exerts a fatherly dominance over what it produces.[86] A king is a man or an entity who is able to merge himself with the axis mundi, the centre of the universe, bringing its order into reality. The ancient kings or emperors of the Chinese civilisation were shamans or priests, that is to say mediators of the divine rule.[89] The same Western terms "king" and "emperor" traditionally meant an entity capable to embody the divine rule: king etymologically means "gnomon", "generator", while emperor means "interpreter", "one who makes from within".

- ^ Temples are usually built in accordance with feng shui methods, which hold that any thing needs to be arranged in equilibrium with the surrounding world in order to thrive. Names of holy spaces often poetically describe their collocation within the world.

- ^ The po can be compared with the psyche or thymos of the Greek philosophy and tradition, while the hun with the pneuma or "immortal soul".[106]

- ^ By the words of the Han dynasty scholar Dong Zhongshu: "Heaven, Earth and humankind are the foundations of all living things. Heaven engenders all living things, Earth nourishes them, and humankind completes them." In the Daodejing: "Tao is great. Heaven is great. Earth is great. And the king [humankind] is also great." The concept of the Three Powers / Agents / Ultimates is furtherly discussed in Confucian commentaries of the Yijing.[113]

- ^ The White Sulde (White Spirit) is one of the two spirits of Genghis Khan (the other being the Black Sulde), represented either as his white or yellow horse or as a fierce warrior riding this horse. In its interior, the temple enshrines a statue of Genghis Khan (at the center) and four of his men on each side (the total making nine, a symbolic number in Mongolian culture), there is an altar where offerings to the godly men are made, and three white suldes made with white horse hair. From the central sulde there are strings which hold tied light blue pieces of cloth with a few white ones. The wall is covered with all the names of the Mongol kins. The Chinese worship Genghis as the ancestral god of the أسرة يوان.

- ^ The main axis of the Taoist Temple of Fortune and Longevity (福壽觀 Fúshòuguān) has a Temple of the Three Patrons (三皇殿 Sānhuángdiàn) and a Temple of the Three Purities (三清殿 Sānqīngdiàn, the orthodox gods of Taoist theology). Side chapels include a Temple of the God of Wealth (財神殿 Cáishéndiàn), a Temple of the Lady (娘娘殿 Niángniángdiàn), a Temple of the Eight Immortals (八仙殿 Bāxiāndiàn), and a Temple of the (God of) Thriving Culture (文昌殿 Wénchāngdiàn). The Fushou Temple belongs to the Taoist Church and was built in 2005 on the site of a former Buddhist temple, the Iron Tiles Temple, which stood there until it was destituted and destroyed in 1950. Part of the roof tiles of the new temples are from the ruins of the former temple excavated in 2002.

- ^ The image is a good synthesis of the basic virtues of Chinese religion and Confucian ethics, that is to say "to move and act according to the harmony of Heaven". The Big Dipper or Great Chariot in Chinese culture (as in other traditional cultures) is a symbol of the axis mundi, the source of the universe (God, Tian) in its way of manifestation, order of creation (li or Tao).

The symbol, also called the Gate of Heaven (天門 Tiānmén), is widely used in esoteric and mystical literature. For example, an excerpt from Shangqing Taoism's texts:

- "Life and death, separation and convergence, all derive from the seven stars. Thus when the Big Dipper impinges on someone, he dies, and when it moves, he lives. That is why the seven stars are Heaven's chancellor, the yamen where the gate is opened to give life."[128]

- ^ Temples of the Jade Deity, a representation of the universal God in popular religion, are usually built on raised artificial platforms.

المصادر

الحواشي

- ^ Brown, Melissa J.; Feldman, Marcus W. (2009). "Sociocultural epistasis and cultural exaptation in footbinding, marriage form, and religious practices in early 20th-century Taiwan". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (52): 22139–22144. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907520106.

- ^ Teiser (1995), p. 378.

- ^ Overmyer (1986), p. 51.

- ^ Fan, Chen 2013. p. 5-6

- ^ Fan, Chen 2013. p. 21

- ^ أ ب Fan, Chen 2013. p. 23

- ^ Gaenssbauer (2015), p. 28-37.

- ^ Zhuo, Xinping (2014). "Civil Society and the Multiple Existence of Religions". Relationship between Religion and State in the People's Republic of China (PDF). Vol. 4. pp. 22–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-05-02.

- ^ Sautman, 1997. pp. 80–81

- ^ Chau, Adam Yuet (2005). "The Politics of Legitimation and the Revival of Popular Religion in Shaanbei, North-Central China". Modern China. Sage. 31 (2): 236–278. doi:10.1177/0097700404274038. ISSN 0097-7004. JSTOR 20062608.

- ^ Overmyer (1986), p. 86.

- ^ أ ب Fan & Chen (2013), pp. 5–6.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Fan & Chen (2013), p. 21.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Fan & Chen (2013), p. 23.

- ^ Adler (2011), p. 13.

- ^ أ ب Teiser, 1996.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Thien Do, 2003, pp. 10–11

- ^ Bowker, John (2021). World Religions: The Great Faiths Explored & Explained. New York: DK. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-7440-3475-2.

- ^ Clart (2014), p. 393, "The problem started when the Taiwanese translator of my paper chose to render 'popular religion' literally as قالب:Zhp. The immediate association this term caused in the minds of many Taiwanese and practically all mainland Chinese participants in the conference was of popular sects قالب:Zhp, rather than the local and communal religious life that was the main focus of my paper..

- ^ Clart (2014), pp. 399–401.

- ^ Clart (2014), p. 402.

- ^ Clart (2014), pp. 402–406.

- ^ Clart (2014), p. 409.

- ^ Tan (1983), p. 219.

- ^ Shi (2008).

- ^ Clart (2014), p. 409, note 35.

- ^ Douglas Howland. Borders of Chinese Civilization: Geography and History at Empire's End. Duke University Press, 1996. ISBN 0822382032. p. 179

- ^ Shi (2008), pp. 158–159.

- ^ Clart (2014), p. 397.

- ^ Wang (2011), p. 3.

- ^ Commentary on Judgment about Yijing 20, Guan ('Viewing'): "Viewing the Way of the Gods (Shendao), one finds that the four seasons never deviate, and so the sage establishes his teachings on the basis of this Way, and all under Heaven submit to him".

- ^ Herman Ooms. Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan: The Tenmu Dynasty, 650–800. University of Hawaii Press, 2009. ISBN 0824832353. p. 166

- ^ Brian Bocking. A Popular Dictionary of Shinto. Routledge, 2005. ASIN: B00ID5TQZY p. 129

- ^ Stuart D. B. Picken. Essentials of Shinto: An Analytical Guide to Principal Teachings. Resources in Asian Philosophy and Religion. Greenwood, 1994. ISBN 0313264317 p. xxi

- ^ John W. Dardess. Ming China, 1368–1644: A Concise History of a Resilient Empire. Rowman & Littlefield, 2012. ISBN 1442204915. p. 26

- ^ J. J. M. de Groot. Religion in China: Universism a Key to the Study of Taoism and Confucianism. 1912.

- ^ Hu, Shih (2013) [1931]. English Writings of Hu Shih: Chinese Philosophy and Intellectual History. China Academic Library. Vol. 2. Springer. ISBN 978-3642311819.

- ^ Clart (2014), p. 405.

- ^ أ ب Clart (2014), p. 408.

- ^ Clart (2014), p. 407.

- ^ Clart (2014), pp. 408–409.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Fan & Chen (2013), p. 5.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Wang, 2004. pp. 60–61

- ^ Fenggang Yang, Social Scientific Studies of Religion in China: Methodologies, Theories, and Findings . BRILL, 2011. ISBN 9004182462. p. 112

- ^ أ ب Fan & Chen (2013), p. 4.

- ^ Tu Weiming. The Global Significance of Concrete Humanity: Essays on the Confucian Discourse in Cultural China. India Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2010. ISBN 8121512204 / 9788121512206

- ^ Madsen, Secular belief, religious belonging. 2013.

- ^ Yang & Hu (2012), p. 507.

- ^ Yang & Hu (2012), pp. 507–508.

- ^ Pearson, Patricia O'Connell; Holdren, John (May 2021). World History: Our Human Story. Versailles, Kentucky: Sheridan Kentucky. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-60153-123-0.

- ^ أ ب Overmyer (2009), p. 36-37.

- ^ Martin-Dubost, Paul (1997), Gaņeśa: The Enchanter of the Three Worlds, Mumbai: Project for Indian Cultural Studies, ISBN 978-8190018432. p. 311

- ^ أ ب ت Fan & Chen (2013), p. 9.

- ^ Overmyer (2009), p. 43.

- ^ Overmyer (2009), p. 45.

- ^ Chang, Iris (2003). The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. New York: Viking Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-670-03123-8.

- ^ Overmyer (2009), p. 46.

- ^ أ ب Overmyer (2009), p. 50.

- ^ Queen II, Edward L.; Prothero, Stephen R.; Shattuck Jr., Gardiner H. (1996). The Encyclopedia of American Religious History. Vol. 1. New York: Proseworks. p. 85. ISBN 0-8160-3545-8.

- ^ أ ب ت Overmyer (2009), p. 51.

- ^ Fan & Chen (2013), p. 1.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Fan & Chen (2013), p. 8.

- ^ Overmyer (2009), p. 52.

- ^ Fan & Chen (2013), p. 28.

- ^ Jansen (2012), p. 288.

- ^ Jansen (2012), p. 289.

- ^ Holloway, Kenneth. Guodian: The Newly Discovered Seeds of Chinese Religious and Political Philosophy Archived 15 فبراير 2024 at the Wayback Machine. Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 0199707685

- ^ Didier, 2009. Represented in vol. III, discussed throughout vols. I, II, and III.

- ^ Didier, 2009. Vol. III, p. 1

- ^ أ ب ت ث Didier, 2009. Vol. III, pp. 3-6

- ^ Didier, 2009. Vol. II, p. 100

- ^ Didier, 2009. Vol. III, p. 7

- ^ Didier, 2009. Vol. III, p. 256

- ^ Didier, 2009. Vol. III, p. 261

- ^ Zhou, 2005. passim

- ^ Adler, 2011. p. 4

- ^ أ ب Adler, 2011. p. 5

- ^ John Lagerwey, Marc Kalinowski. Early Chinese Religion I: Shang Through Han (1250 BC – 220 AD). Two volumes. Brill, 2008. ISBN 9004168354. p. 240

- ^ Lu, Gong. 2014. pp. 63–66

- ^ Lü & Gong (2014), p. 65.

- ^ أ ب Lü & Gong (2014), p. 66.

- ^ أ ب Lagerwey & Kalinowski (2008), p. 981.

- ^ Lu, Gong. 2014. p. 65

- ^ أ ب ت Libbrecht, 2007. p. 43

- ^ Chang, 2000.

- ^ أ ب Lu, Gong. 2014. p. 64

- ^ Mark Lewis. Writing and Authority in Early China. SUNY Press, 1999. ISBN 0791441148. pp. 205–206 Archived 26 مارس 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Didier, 2009. Vol. III, p. 268

- ^ Joseph Needham. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. III. p. 23

- ^ Lu, Gong. 2014. p. 71

- ^ Adler, 2011. pp. 12–13

- ^ أ ب Teiser (1996), p. 29.

- ^ أ ب Adler, 2011. p. 21

- ^ Teiser (1996), p. 30.

- ^ أ ب Adler, 2011. p. 13 Archived 9 أكتوبر 2022 at Ghost Archive

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Adler, 2011. p. 16

- ^ أ ب ت Adler, 2011. p. 14

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Teiser (1996), p. 31.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Teiser (1996), p. 32.

- ^ أ ب ت Zongqi Cai, 2004. p. 314

- ^ Adler, 2011. p. 17

- ^ Adler, 2011. p. 15

- ^ Adler, 2011. pp. 15–16

- ^ Adler, 2011. p. 19

- ^ Lu, Gong. 2014. p. 68

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Lu, Gong. 2014. p. 69

- ^ Adler, 2011. pp. 19–20

- ^ Sautman, 1997. p. 78

- ^ Yao (2010), pp. 162, 165.

- ^ Yao (2010), pp. 158–161.

- ^ Yao (2010), p. 159.

- ^ أ ب ت Yao (2010), pp. 162–164.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Yao (2010), p. 164.

- ^ Yao (2010), p. 166.

- ^ أ ب Fan & Chen (2013), p. 25.

- ^ أ ب Fan & Chen (2013), p. 26.

- ^ Fan & Chen (2013), p. 24.

- ^ Fan & Chen (2013), pp. 26–27.

- ^ أ ب ت Fan & Chen (2013), p. 27.

- ^ Thien Do, 2003, p. 9

- ^ Zavidovskaya, 2012. pp. 179–183

- ^ Zavidovskaya, 2012. pp. 183–184

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز Zavidovskaya, 2012. p. 184

- ^ أ ب Yao (2010), p. 168.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Zavidovskaya, 2012. p. 185

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Zavidovskaya, 2012. p. 183

- ^ Clart (1997), pp. 12-13 & passim.

- ^ Bai Bin, "Daoism in Graves". In Pierre Marsone, John Lagerwey, eds., Modern Chinese Religion I: Song-Liao-Jin-Yuan (960-1368 AD), Brill, 2014. ISBN 9004271643. p. 579

المراجع

- Adler, Joseph (2005), "Chinese Religion: An Overview", in Jones, Lindsay, Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd Ed., Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. Available at the author's website.

- Adler, Joseph A. (2011). "The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China" in (Conference paper) Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought..

- Cai, Zongqi (2004). Chinese Aesthetics: Ordering of Literature, the Arts, and the Universe in the Six Dynasties. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824827910.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chamberlain, Jonathan (2009). Chinese Gods : An Introduction to Chinese Folk Religion. Hong Kong: Blacksmith Books. ISBN 9789881774217.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chan, Kim-Kwong (2005). "Religion in China in the Twenty-first Century: Some Scenarios". Religion, State & Society. Routledge. 33 (2).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chang, Ruth H. (2000). "Understanding Di and Tian: Deity and Heaven from Shang to Tang Dynasties". Sino-Platonic Papers. Victor H. Mair (108). ISSN 2157-9679.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chau, Adam Yuet (2005). Miraculous Response: Doing Popular Religion in Contemporary China. ISBN 9780804751605.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chau, Adam Yuet (2005). "The Politics of Legitimation and the Revival of Popular Religion in Shaanbei, North-Central China" (PDF). Modern China. Sage Publications. 31 (2): 236–278. doi:10.1177/0097700404274038. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 ديسمبر 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Chau, Adam Yuet (2011). "Modalities of Doing Religion and Ritual Polytropy: Evaluating the Religious Market Model from the Perspective of Chinese Religious History". Religion. 41 (4): 457–568. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2011.624691.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Chau, Adam Yuet (2013), "A Different Kind of Religious Diversity: Ritual Service Providers and Consumers in China", Religious Diversity in Chinese Thought, New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, pp. 141–156, ISBN 9781137333193, https://books.google.com/books?id=VePQAQAAQBAJ

- Cheng, Manchao (1995). The Origin of Chinese Deities. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7119000306.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clart, Philip (2014). "Conceptualizations of "Popular Religion" in Recent Research in the People's Republic of China" in (Conference paper) International Symposium on Mazu and Chinese folk religion「媽祖與華人民間信仰」國際研討會論文集.: 391–412.

- Clart, Philip (2003). "Confucius and the Mediums: Is There a "Popular Confucianism"?" (PDF). T'oung Pao. Leiden: Brill (LXXXIX).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clart, Philip (1997). "The Phoenix and the Mother: The Interaction of Spirit Writing Cults and Popular Sects in Taiwan" (PDF). Journal of Chinese Religions. 25: 1–32.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davis, Edward L. (2005). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Chinese Culture. Routledge. ISBN 0415241294.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - De Groot, J.J.M. (1892). The Religious System of China: Its Ancient Forms, Evolution, History and Present Aspect, Manners, Customs and Social Institutions Connected Therewith. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) 6 volumes. Online at: Les classiques des sciences sociales, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi; Scribd: Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4, Vol. 5, Vol. 6. - Didier, John C. (2009). "In and Outside the Square: The Sky and the Power of Belief in Ancient China and the World, c. 4500 BC – AD 200". Sino-Platonic Papers. Victor H. Mair (192).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Volume I: The Ancient Eurasian World and the Celestial Pivot, Volume II: Representations and Identities of High Powers in Neolithic and Bronze China, Volume III: Terrestrial and Celestial Transformations in Zhou and Early-Imperial China. - Do, Thien (2003). Vietnamese Supernaturalism: Views from the Southern Region. Anthropology of Asia. Routledge. ISBN 0415307996.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fan, Lizhu; Chen, Na (2015). "The Religiousness of "Confucianism" and the Revival of Confucian Religion in China Today". Cultural Diversity in China. De Gruyter Open (1): 27–43. doi:10.1515/cdc-2015-0005. ISSN 2353-7795.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fan, Lizhu; Chen, Na (2013). "The Revival of Indigenous Religion in China" (PDF). China Watch.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Preprint from The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion, 2014. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195338522.013.024 - Fowler, Jeanine D. (2005). An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1845190866.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goossaert, Vincent; Palmer, David (2011). The Religious Question in Modern China. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226304167.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gaenssbauer, Monika (2015). Popular Belief in Contemporary China: A Discourse Analysis. Projekt Verlag. ISBN 0226304167.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jin, Ze (2005). "Challenges and Choices Facing Folk Faith in China" in Religion and Cultural Change in China..

- Jansen, Thomas (2012), "Sacred Texts", in Nadeau, Randall L., The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Chinese Religions, Wiley Blackwell Companions to Religion, 82, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 144436197X, https://books.google.com/books?id=FmnKSfAS4PcC

- Jones, Stephen (2013). In Search of the Folk Daoists of North China. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 1409481301.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lagerwey, John; Kalinowski, Marc (2008). Early Chinese Religion: Part One: Shang Through Han (1250 BC-220 AD). Early Chinese Religion. Brill. ISBN 9004168354.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Law, Pui-Lam (2005). "The Revival of Folk Religion and Gender Relationships in Rural China: A Preliminary Observation". Asian Folklore Studies. 64: 89–109.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Li, Ganlang (2009). 台灣古建築圖解事典 (四版五刷 ed.). Taipei: 遠流出版社. pp. 47–49. ISBN 957324957X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Li, Lan (2016). Popular Religion in Modern China: The New Role of Nuo. Routledge. ISBN 1317077954.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Libbrecht, Ulrich (2007). Within the Four Seas...: Introduction to Comparative Philosophy. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9042918128.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Little, Stephen; Eichman, Shawn (2000). Taoism and the Arts of China. University of California Press. ISBN 0520227859.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Littlejohn, Ronnie (2010). Confucianism: An Introduction. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 184885174X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lü, Daji; Gong, Xuezeng (2014). Marxism and Religion. Religious Studies in Contemporary China. Brill. ISBN 9047428021.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Medhurst, Walter H. (1847). A Dissertation on the Theology of the Chinese, with a View to the Elucidation of the Most Appropriate Term for Expressing the Deity, in the Chinese Language. Mission Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Original preserved at The British Library. Digitalised in 2014. - Mou, Zhongjian (2012). Taoism. Brill. ISBN 9004174532.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Overmyer, Daniel L. (1986). Religions of China: The World as a Living System. New York: Harper & Row.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Overmyer, Daniel L. (2009). Local Religion in North China in the Twentieth Century: The Structure and Organization of Community Rituals and Beliefs (PDF). Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789047429364.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ownby, David (2008). "Sect and Secularism in Reading the Modern Chinese Religious Experience". Archives de sciences sociales des religions. 144. doi:10.4000/assr.17633.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Palmer, David A. (2011). "Chinese Redemptive Societies and Salvationist Religion: Historical Phenomenon or Sociological Category?" (PDF). Journal of Chinese Ritual, Theatre and Folklore. 172: 21–72.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paper, Jordan (1995). The Spirits are Drunk: Comparative Approaches to Chinese Religion. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791423158.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pregadio, Fabrizio (2013). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Routledge. ISBN 1135796343.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Two volumes: 1) A-L; 2) L-Z. - Pas, Julian F. (2014). Historical Dictionary of Taoism. Historical Dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies, and Movements. Albany, NY: Scarecrow Press. ASIN B00IZ9E7EI.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Payette, Alex (February 2016). "Local Confucian Revival in China: Ritual Teachings, 'Confucian' Learning and Cultural Resistance in Shandong". China Report. 52 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1177/0009445515613867.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sautman, Barry (1997). Myths of Descent, Racial Nationalism and Ethnic Minorities in the People's Republic of China.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Chapter of: Frank Dikötter. The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Honolulu, University of Hawai'i Press, pp. 75–95. ISBN 9622094430. - Shahar, Meir; Weller, Robert Paul (1996), Unruly Gods: Divinity and Society in China, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0190258144, https://books.google.com/books?id=gegRl__dR8EC

- Shi, Yilong 石奕龍 (2008). "中国汉人自发的宗教实践 — 神仙教 Zhongguo Hanren zifadi zongjiao shijian: Shenxianjiao (The Spontaneous Religious Practices of Han Chinese Peoples — Shenxianism)". 中南民族大学学报 — 人文社会科学版 (Journal of South-Central University for Nationalities (Humanities and Social Sciences)). 28 (3): 146–150.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shen, Qingsong; Shun, Kwong-loi (2007). Confucian Ethics in Retrospect and Prospect. Council for Research in Values & Philosophy. ISBN 1565182456.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tay, Wei Leong (2010). Kang Youwei: The Martin Luther of Confucianism and His Vision of Confucian Modernity and Nation (PDF).

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Chapter of: Haneda Masashi, Secularization, Religion and the State, University of Tokyo Center for Philosophy. - Sun, Xiaochun; Kistemaker, Jacob (1997). The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society. Brill. ISBN 9004107371.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Teiser, Stephen F. (1996), "The Spirits of Chinese Religion", in Donald S. Lopez Jr., Religions of China in Practice, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/cosmos/main/spirits_of_chinese_religion.pdf, extracts at The Chinese Cosmos: Basic Concepts.

- Teiser, Stephen F. (1995). "Popular Religion". Journal of Asian Studies. 54 (2): 378–395. doi:10.2307/2058743.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wang, Mingming (2011). "A Drama of the Concepts of Religion: Reflecting on Some of the Issues of "Faith" in Contemporary China" (PDF). Asia Research Institute Working Paper Series (155): 27.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wang, Robin R. (2004). Chinese Philosophy in an Era of Globalization. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791460061.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wu, Hsin-Chao (2014). "Local Traditions, Community Building, and Cultural Adaptation in Reform Era Rural China" (PDF). Harvard University.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yang, Fenggang; Hu, Anning (2012). "Mapping Chinese Folk Religion in Mainland China and Taiwan". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 51 (3): 505–521. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2012.01660.x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yang, Mayfair Mei-hui (2007), "Ritual Economy and Rural Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics", Cultural Politics in a Global Age: Uncertainty, Solidarity and Innovation, Oxford: Oneworld Publications, ISBN 1851685502. Available online.

- Yang, C. K. (1961). Religion in Chinese Society; a Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors. Berkeley: University of California Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yao, Xinzhong (2010). Chinese Religion: A Contextual Approach. London: A&C Black. ISBN 9781847064752.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zavidovskaya, Ekaterina A. (2012). "Deserving Divine Protection: Religious Life in Contemporary Rural Shanxi and Shaanxi Provinces". St. Petersburg Annual of Asian and African Studies. Ergon-Verlag GmbH, 97074 Würzburg. I: 179–197.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location (link) - Zhao, Dunhua (2012), "The Chinese Path to Polytheism", in Wang, Robin R., Chinese Philosophy in an Era of Globalization, ISBN 0791485501, https://books.google.com/books?id=7BMp7VT7G4oC

- Zhou, Jixu (2005). "Old Chinese "*tees" and Proto-Indo-European "*deus": Similarity in Religious Ideas and a Common Source in Linguistics" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. Victor H. Mair (167).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- مقالات

- Fenggang Yang. Stand still and watch. In The state of religion in China. The Immanent Frame, 2013.

- Prasenjit Duara. Chinese religions in comparative historical perspective. In The state of religion in China. The Immanent Frame, 2013.

- Richard Madsen. Secular belief, religious belonging. In The state of religion in China. The Immanent Frame, 2013.

- Nathan Schneider. The future of China’s past: An interview with Mayfair Yang. The Immanent Frame, 2010.

وصلات خارجية

- China Ancestral Temples Network

- Bored in Heaven, a documentary on the reinvention of Chinese religion and Taoism. By Kenneth Dean, 2010, 80 minutes.

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- Webarchive template other archives

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from September 2024

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة from April 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2023

- Articles using infobox templates with no data rows

- Pages using div col with unknown parameters

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 maint: location

- الدين في الصين

- الديانة الشعبية الصينية

- ديانات شرق آسيوية

- ديانات شعبية