الامبراطور الأصفر

| الامبراطور الأصفر 黃帝 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| أحد السادة الثلاث والأباطرة الخمس | |||||

| |||||

| العهد | 2698–2598 ق.م.[1] | ||||

| توفي | 2598 ق.م. | ||||

| الزوج | لـِيْزو فنگلـِيْ Tongyu مـُمو | ||||

| الأنجال | شاوهاو تشانگيي، والد ژوانشو | ||||

| |||||

| الأب | شاوديان | ||||

| الأم | فوباو | ||||

| هوانگدي | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الصينية التقليدية | 黃帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الصينية المبسطة | 黄帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المعنى الحرفي | "الامبراطور الأصفر" / "الإله الأصفر" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

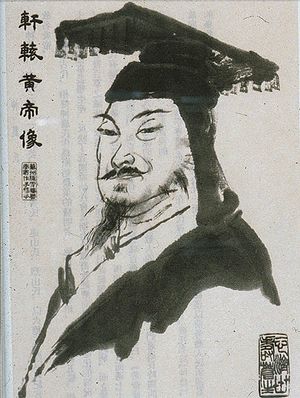

الامبراطور الأصفر أو الإله الأصفر (بالصينية هوانگدي ، وكان في السابق يُكتب بحروف لاتينية كالتالي: Huang Ti و Hwang Ti)[note 1]، ويُعرف أيضاً بإسم هوانگشن (黄神 "الإله الأصفر")[6] هو إله في الديانة الصينية، أحد السادة الصينيين وأبطال الثقافة الأسطوريين[7][8] متضمَناً بين السادة الثلاث والأباطرة الخمس الأسطوريين-التاريخيين[9] ونُظم الصيغ الخمس الكونية للإله الأعلى (五方上帝 ووفانگ شانگدي).[10][note 2] وتروي التقاليد أن هوانگدي حكم من 2697 إلى 2597[11] أو 2698 إلى 2598 ق.م.[1]

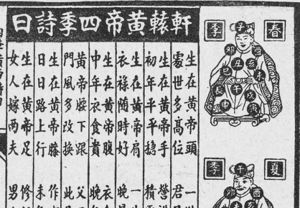

ويُعرف أيضاً بالأسماء والألقاب التالية: شوانيوان هوانگدي (轩辕黄帝 "الإله الأصفر ذو الأصل الغامض") أو شوانيوانشي (轩辕氏 "المقدس ذو الأصل الغامض")، هوانگشن بـِيْدو (黄神北斗 "الإله الأصفر من مجمة بنات نعش")،[12] أو كإله كوني مثل ژونگيوىدادي (中岳大帝 "الإله العظيم للقمة الوسطى")[10] وفي شيزي كـ هوانگدي سيميان (黄帝四面 "الامبراطور الأصفر ذو الأربع أوجه").[13]

وكانت عبادة هوانگدي بارزة في أواخر الدويلات المتناحرة ومطلع فترة هان، حين كان يُصوَّر كأصل الدولة المركزية، والحاكم الكوني وراعي الفنون العجيبة. وتقليدياً يُعزى إليه العديد من الاختراعات والابتكارات،[14] الامبراطور الأصفر يُعتبر الآن كبادئ الحضارة الصينية،[15] ويقال أنه سلف كل صينيي هواشيا.[16]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأسماء والمعاني

إله مركز الكون

أصل وتطور الأسطورة

الأصول

الامبراطور الأصفر في الأزمنة قبل الامبراطورية

عناصر أسطورة هوانگدي

الانجازات

In traditional Chinese accounts, the Yellow Emperor is credited with improving the livelihood of the nomadic hunters of his tribe. He teaches them how to build shelters, tame wild animals, and grow the five Chinese cereals,[18] although other accounts credit Shennong with the last. He invents carts, boats, and clothing.[18]

Other inventions credited to the emperor include the Chinese diadem (冠冕), throne rooms (宮室), the bow sling, early Chinese astronomy, the Chinese calendar, math calculations, code of sound laws (音律),[19] and cuju, an early Chinese version of football.[20] He is also sometimes said to have been partially responsible for the invention of the guqin zither,[21] although others credit the Yan Emperor with inventing instruments for Ling Lun's compositions.[22]

In traditional accounts, he also goads the historian Cangjie into creating the first Chinese character writing system, the Oracle bone script,[18] and his principal wife Leizu invents sericulture and teaches his people how to weave silk and dye clothes.[18]

At one point in his reign the Yellow Emperor allegedly visited the mythical East sea and met a talking beast called the Bai Ze who taught him the knowledge of all supernatural creatures.[23][24] This beast explained to him there were 11,522 (or 1,522) kinds of supernatural creatures.[23][24]

المعارك

According to traditional accounts, the Yan Emperor meets the force of the "Nine Li" (九黎) under their bronze-headed leader, Chi You,[25] and his 81 horned and four-eyed brothers[16] and suffers a decisive defeat. He flees to Zhuolu and begs the Yellow Emperor for help. During the ensuing Battle of Zhuolu the Yellow Emperor employs his tamed animals and Chi You darkens the sky by breathing out a thick fog.[26] This leads the emperor to develop the south-pointing chariot, which he uses to lead his army out of the miasma.[16][26] He next calls upon the drought demon Nuba to dispel Chi You's storm.[16][26] He then destroys the Nine Li and defeats Chi You[27] before falling out with the Yan Emperor, defeating him at Banquan[25] and replacing him as the primary ruler.[28]

الوفاة

قيل أن الامبراطور الأصفر عاش لأكثر من مائة عام قبل أن يلاقي عنقاء و چيلين ثم مات.[1] وقد بُنيت مقبرتان في شآنشي داخل ضريح الامبراطور الأصفر، بالاضافة لآخرين في هـِنان، خبي وگانسو.[29]

الشعب الصيني الحالي أحياناً يشير لنفسه بالتعبير "سليلو يان والامبراطور الأصفر",[18] بالرغم من أن الجماعات غير الهان في الصين قد يكون، أو لا يكون، لديهم أساطير خاصة أو لا يعدون أنفسهم سليلي الامبراطور.[30]

الأسرة والنسل

حين توفي الامبراطور الأصفر، خلـَفه ابن تشانگيي، ژوانشو.[2]

وتزعم المصادر اللاحقة أن العديد من الأباطرة وأربع أسر تالية انحدرت من الامبراطور الأصفر:[19][31] وثمة أسر أخرى، بجانب تلك الأربع الأوائل، تزعم انتسابها إلى الامبراطور الأصفر.

سيما چيان، في كتابه سجلات المؤرخ العظيم، (史記 [تقليدي]/史记 [مبسط])، يروي لنا أن والدة الامبراطور ون من هان كانت القرينة بو، (薄姬، لاحقاً الامبراطورة الأرملة بو، [薄太后]، أو الامبراطورة الأرملة شياوْوِن، [孝文太后])؛ وأنها كانت الابنة غير الشرعية للنبيل بو، (薄翁)، من ناحية وو، (吳縣)، في سوژو المعاصرة، جيانگسو؛ و السيدة وِيْ، "أميرة" مملكة وِيْ في "الدويلات المتناحرة"، which line was a branch of the Zhou dynasty. All future Han Emperors were descended from Wendi. Several Han Princesses were sent to be consorts of the Chanyu of the Hsiung-nus; so that, at the fall of the Han, the then Chanyu of the Hsiung-nu claimed the Chinese throne due to these marriages.

According to the Wei Shu and Tung Pa, the Cao family of Cao Wei were descended from Huangdi via Emperor Zhuanxu, from which the Cao family originated. They were of the same lineage as Emperor Shun. Another account says that the Cao family was descended from Emperor Shun. This account was attacked by Chiang Chi who claimed it was people of the Tian 田 surname who were descended from Shun and not the Cao. He also claimed (Gui) Kuei 媯 was Shun's family name.[35][36]

During the reign of Emperor Zhenzong أباطرة سونگ claimed Huangdi as an ancestor.[37]

Gun, Yu, Zhuanxu, Zhong, Li, Shujun, and Yuqiang are various emperors, gods, and heroes whose ancestor was Huangdi. The Huantou, Miaomin, and Quanrong peoples were said to be descended from Huangdi.[38]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ادعاءات الانتساب إليه

أثناء أسرة تانگ، كان الامبراطور الأصفر symbolic as the ancestor of the Han Chinese and founder of Chinese civilization, was also claimed by various other rulers who were not Han Chinese to be their ancestors, in order to connect themselves to the Tang.[39] "Prestige" for the individual and "status" for their country was the goal of those non-Han who made claims of descent from these prominent Han figures.[40]

The Yu (Yee) family of Zhangwan village, Xinhui district, Guangdong claimed descent from Huangdi's son Xuan xiao. Emperor Shun's minister of agriculture, Duke Qi, was of one of the originally 15th generations of the family. The family adopted the last name Yu 30 generations after that. The Kings of Chin and Jin honored their ancestor You Yu. You moved to Shandong, he was originally from the northern China plain. Another ancestor named Yu Rui moved near the Lo river in Shaanxi province. He became a censor for the State of Qin.[41] The family moved into Guangdong during the Ten Kingdoms and five dynasties.[42]

التأثير المجتمعي

تشينگ المتأخرة

بدءاً من 1903، بدأت المنشورات الراديكالية في استخدام التاريخ المحسوب لميلاده كأول سنة في التقويم الصيني.[43] ووجد المفكرون، أمثال ليو شيپـِيْ (1884–1919) هذه الممارسة ضرورية من أجل "الحفاظ على العرق [الهان]" (باوژونگ 保種) من كلٍ من هيمنة المانشو والتوغل الأجنبي.[43] وقد حاول الثوريون المناهضون للمانشو مثل تشن تيانهوا (1875–1905) وزو رونگ (1885–1905)، وژانگ بينگلين (1868–1936) أن يقووا الوعي العرقي الذي كانوا يرون أنه غائب عن مواطنيهم، ولذلك صوّروا المانشو على أنهم برابرة أدنى عرقياً وغير صالحين لحكم صينيي الهان.[44] مَلازِم تشن التي شاعت على نطاق واسع زعمت أن "عرق الهان" شكـّل عائلة واحدة كبيرة تنحدر من الامبراطور الأصفر.[45] أول عدد (نوفمبر 1905) من مينباو 民報 ("جريدة الشعب"[46])، التي أسسها في طوكيو الثوريون من تونگمنگهوي، تصدرتها صورة الامبراطور الأصفر على غلافها ووصفت هوانگدي بأنه "أول وطني عظيم في العالم."[أ] وكانت واحدة من عدة مجلات وطنية تصدرتها صورة الامبراطور الأصفر على أغلفتها في مطلع القرن العشرين.[48] حقيقة أن هوانگدي يعني الامبراطور "الأصفر" عملت أيضاً على دعم نظرية أنه بادئ "العرق الأصفر".[49]

ويفسر العديد من المؤرخين هذه الشعبية المفاجئة للامبراطور الأصفر بأنها رد فعل لنظريات الدارس الفرنسي ألبير تريان دى لاكوپري (1845–1894)، الذي زعم في كتابه المعنوَن الأصل الغربي للحضارة الصينية المبكرة، من 2300 ق.م. حتى 200م (1892)، أن الحضارة الصينية تأسست قبل 4200 سنة من تاريخها المتداول، وكان ذلك التأسيس على أيدي مهاجرين من بلاد الرافدين.[50] نظرية لاكوپري "الصينو-بابلية" زعمت أن هوانگدي كان زعيماً قبلياً من بلاد الرافدين قاد هجرة هائلة لشعبه إلى الصين حوالي 2300 ق.م. وأسس ما سيصبح لاحقاً الحضارة الصينية.[51] وسرعان ما رفض علماء الصينيات الأوروبيون تلك النظريات، ولكن في 1900 محى مؤرخان يابانيان، شيراكاوا جيرو و كـُكوبو تانىنوري، انتقاداتهما ونشرا ملخص طويل لآراء لاكوپري كأكثر الدراسات الأوروبية تقدماً حول الصين.[52] وسرعان ما انجذب الدارسون الصينيون إلى "تاريخانية الأساطير الصينية" وهو ما كان ينادي به المؤرخان اليابانيان.[53]

المفكرون والناشطون المناهضون للمانشو الذين بحثوا عن "الروح الوطنية" للصين (گووتسوي 國粹) اعتمدوا الصينو-بابلية لتلبية احتياجاتهم.[54] وشرح ژانگ بينگلين معركة هوانگدي مع تشي يو كنزاع ضد البابليين المتمدنين القادمين حديثاً من قِبل القبائل المحلية المتخلفة، وهي المعركة التي غيرت الصين إلى واحدة من أكثر الأماكن تمدناً في العالم.[55] اعادة التفسير التي قام بها ژانگ لرواية سيما چيان يركز على الحاجة لاستعادة مجد الصين المبكرة."[56] كما يقدم ليو شيپـِيْ تلك الأزمنة المبكرة على أنها العصر الذهبي للحضارة الصينية.[57] وبالاضافة لربط الصينيين بمركز قديم للحضارة البشرية في بلاد الرافدين، تقترح نظريات لاكوپري أن الصين يجب أن يحكمها سليلو هوانگدي. وفي مقال مثير للجدل بعنوان تاريخ العرق الأصفر (هوانگشي 黃史)، الذي نُشِر مسلسلاً من 1905 وحتى 1908، يزعم هوانگ جيى (黃節؛ 1873–1935) أن عرق الهان كان السيد الحقيقي للصين لأنه ينحدر من الامبراطور الأصفر.[58] مدعوماً بقيَم تبجيل الوالدين و العشيرة الأبوية الصينية،[59] فقد حوّلت الرؤية العرقية، التي دافع عنها هوانگ وآخرون، الانتقام من المانشو إلى واجب كل شخص تجاه أجداده.[60][61]

الفترة الجمهورية

استمر تقديس الامبراطور الأصفر بعد ثورة شينهاي في 1911، التي أطاحب بأسرة تشينگ. وفي 1912، على سبيل المثال، صدرت أوراق نقدية تحمل صورة هوانگدي من الحكومة الجمهورية الجديدة.[62] إلا أنه بعد 1911، فإن الامبراطور الأصفر كرمز وطني تغير من أصل عرق الهان إلى سلف كل سكان الصين بمختلف أعراقهم.[63] فضمن أيديولوجية خمسة أعراق تحت أمة واحدة، أصبح هوانگدي السلف المشترك لكل من الهان والمانشو والمنغول والتبتيون والمسلمون الهوي، الذين قيل أنهم يشكلون ژونگهوا مينزو، الأمة الصينية بمفهومها الواسع.[63] وقد أقيم ستة عشر احتفالاً بين 1911 و 1949 لـهوانگدي بصفته "السلف المؤسس للأمة الصينية" (中華民族始祖) بل وحتى "السلف المؤسس للحضارة البشرية" (人文始祖).[62]

الأهمية المعاصرة

التواريخ التقليدية

الفيلم

- فيلم درامي صيني صدر في عام 2016 عن قصة الامبراطور الأصفر، بعنوان "Xuan Yuan: The Great Emperor" (轩辕大帝).[64]

انظر أيضاً

- الديانة الشعبية الصينية

- الإلهيات الصينية

- قائمة حكام الصين

- هوانگ-لاو

- Simianshen

- الطاوية

- Tianxia

- Wufang Shangdi

- Xuanyuanism

- في الثقافات الأخرى

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الملاحظات

- ^ 帝 دي يمكن ترجمتها "امبراطور" أو "إله" أو "ثيارخ"، وهو مصطلح يميز إله-ملك أو إله متجسد، من اليونانية ثيوس ("إله") + آرخ ("مبدأ"، "أصل")، بذلك تعني "المبدأ المقدس"، "الأصل المقدس".[3][4][5]

- ^ في التاريخ الأسطوري للفكر الصيني وعلم الكونيات توجد وجهتا نظر تصِفان نفس الواقع. وبكلمات أخرى، فإن الأساطير والتاريخ والإلهيات والكونيات كلهم مرتبطون.

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت Herbert Allen Giles (1845–1935), A Chinese Biographical Dictionary (London: B. Quaritch, 1898), p. 338; cited in Veith 2002, p. 5.

- ^ أ ب ت سيما چيان، سجلات المؤرخ العظيم (شيجي 史記، ح. 100 ق.م.)، الفصل 1، "Wudi benji" 五帝本紀 ("Basic Annals of the Five Emperors"); iFeng.com (retrieved on 2010-08-22). (صينية)

- ^ Pregadio (2013), p. 504, vol. 2 A-L: Each sector of heaven (النقاط الأربع في البوصلة والمركز) جسـَّده دي 帝 (مصطلح يشير ليس فقط لإمبراطور بل أيضاً لـ"ثيارخ" سلفي و "إله").

- ^ Chang (2000).

- ^ Zhou (2005).

- ^ Olberding, Amy (2012). Mortality in Traditional Chinese Thought. SUNY Press. ISBN 1438435649.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). p. 20 - ^ "Huangdi". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Helmer Aslaksen, "The Mathematics of the Chinese Calendar," section "Which Year is it in the Chinese Calendar?" (retrieved on 2011-11-18)

- ^ Zhao & Qin 2002, p. 142.

- ^ أ ب Fowler (2005), pp. 200–201.

- ^ "Yellow Emperor," في The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition (2008). Encyclopedia.com, retrieved on November 8, 2011.

- ^ Lagerwey & Kalinowski (2008), p. 1080.

- ^ Sun & Kistemaker (1997), p. 120.

- ^ Ebrey 1996, p. 10.

- ^ Chang 1983, p. 2

- ^ أ ب ت ث Wang 2005.

- ^ Birrell 1993, p. 48.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةtonsi2 - ^ أ ب Wang 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Liu Xiang (77–6 BC), Bielu 别录:"It is said that cuju was invented by Huangdi; others claim that it arose during the Warring States period" (蹴鞠者,传言黄帝所作,或曰起戰國之時); cited in Book of the Later Han (5th century), chapter 34, p. 1178 of the standard Zhonghua shuju edition. (صينية)

- ^ Yin 2001.

- ^ Huang 1989, vol. 2[صفحة مطلوبة].

- ^ أ ب iFeng.com, "The traitor Bai Ze" 背叛者白澤 (صينية); from Xu 2008. Retrieved on 2010-09-04.

- ^ أ ب Ge 2005, p. 474.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةtonsi1 - ^ أ ب ت Big5.china.com.cn, "Huangdi's great battle against Chi You, and the south-pointing chariot" 黃帝大戰蚩尤與指南車 (صينية). Retrieved on 2010-08-22.

- ^ Heiner Roetz (1993). Confucian ethics of the axial age: a reconstruction under the aspect of the breakthrough toward postconventional thinking. SUNY Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-7914-1649-6. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHaw - ^ China.org.cn, "Mausoleums of the Yellow Emperor." Retrieved on 2010-08-29.

- ^ Sautman 1997, p. 83.

- ^ Wu, p. 64

- ^ Asiapac Editorial (2006). Great Chinese emperors: tales of wise and benevolent rule (revised ed.). Asiapac Books Pte Ltd. p. 9. ISBN 981-229-451-1. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Heiner Roetz (1993). Confucian ethics of the axial age: a reconstruction under the aspect of the breakthrough toward postconventional thinking. SUNY Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-7914-1649-6. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Asiapac Editorial (2006). Great Chinese emperors: tales of wise and benevolent rule (revised ed.). Asiapac Books Pte Ltd. p. 10. ISBN 981-229-451-1. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Howard L. Goodman (1998). Ts'ao P'i transcendent: the political culture of dynasty-founding in China at the end of the Han (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 70. ISBN 0-9666300-0-9. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ "History (2)". houseofchinn.com. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- ^ Patricia Buckley Ebrey (2003). Women and the family in Chinese history. Vol. Volume 2 of Critical Asian scholarship (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-415-28823-1. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Lihui Yang; Deming An; Jessica Anderson Turner (2008). Jessica Anderson Turner (ed.). Handbook of Chinese Mythology (illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 143. ISBN 0-19-533263-6. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Mark Edward Lewis (2009). China's cosmopolitan empire: the Tang dynasty, Volume 4 (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 202. ISBN 0-674-03306-X. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

occasional practice among non-Han leaders of tracing descent from the legendary Yellow Emperor himself—the founding ancestor of the Han Chinese people—or from the ancient Zhou ruling house. Such claims flattered both those who made them and their Tang recipients, who could thus assert a larger realm for their putative ancestor. The Chinese had linked themselves to more distant peoples through a common origin in the ancient sage-kings at least since the late Warring States and early Han mythic geography, the Canon of Mountains and Seas (Shan hai jing).48

- ^ Marc Samuel Abramson (2008). Ethnic identity in Tang China. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-8122-4052-9. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

Non-Han who had greater cultural and social pretensions imitated Han counterparts in claiming descent from Chinese culture heroes of antiquity, particularly the Yellow Emperor and King Wen of the Zhou, even while acknowledging their non-Han roots.22 Such assertions did not intend to assert or broaden the notion of Han ethnicity. Instead, they aimed to garner prestige for the claimant and to give the claimant's original homeland greater status by including it within the mythical geography of the spread of the descendants of the Yellow Emperor and the Zhou royal house. These claims highlight the extent to which public ethnic identities were predicated on both descent and geography, treated with equal importance in Chinese genealogies.

- ^ Lani Ah Tye Farkas (1998). Bury my bones in America: the saga of a Chinese family in California, 1852–1996 : from San Francisco to the Sierra gold mines (illustrated ed.). Carl Mautz Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 1-887694-11-0. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Lani Ah Tye Farkas (1998). Bury my bones in America: the saga of a Chinese family in California, 1852–1996 : from San Francisco to the Sierra gold mines (illustrated ed.). Carl Mautz Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 1-887694-11-0. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ أ ب Dikötter 1992, p. 116.

- ^ Dikötter 1992.

- ^ Dikötter 1992, p. 117.

- ^ Chow 1997, p. 49.

- ^ Sun 2000.

- ^ أ ب Dikötter 1992, p. 116, note 73.

- ^ Chow, Kai-wing; Doak, Kevin Michael; Fu, Poshek, eds. (2001). Constructing nationhood in modern East Asia (ill. ed.). University of Michigan Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-472-06735-4. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Hon 2010, p. 140.

- ^ Hon 2010, p. 145.

- ^ Hon 2010.

- ^ Hon 2010, pp. 147, 149.

- ^ Hon 2010, p. 150.

- ^ Hon 2010, pp. 151–52.

- ^ Hon 2010, p. 153.

- ^ Hon 2010, p. 154.

- ^ Hon 2003.

- ^ Duara 1995, p. 75.

- ^ Dikötter 1992, pp. 71, 117.

- ^ Hon 2010, p. 150 "وفي هذا الضوء، تصبح الصينو-بابلية نفير إلى السلاح لكل سليلي هوانگ دي لشن حرباً عرقياً ضد المانشو".

- ^ أ ب Liu 1999, pp. 608–9.

- ^ أ ب Liu 1999, p. 609.

- ^ 轩辕大帝 (2016)

ببليوگرافيا

- Allan, Sarah (1991), The Shape of the Turtle, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-0460-9, http://books.google.com/books?id=QlEZd4x9LUAC.

- Birrell, Anne (1993), Chinese Mythology: An Introduction, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-4595-5, 0-8018-6183-7.

- Chang, Chun-shu (2007), The Rise of the Chinese Empire, 1. Nation, State, and Imperialism in Early China, ca. 1600 BC – AD 157, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-11533-4.

- Chang, KC [張光直] (1983), Art, Myth, and Ritual: The Path to Political Authority in Ancient China, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-04807-5, 0-674-04808-3.

- Chang, Ruth H. (2000). "Understanding Di and Tian: Deity and Heaven from Shang to Tang Dynasties". Sino-Platonic Papers. Victor H. Mair (108). ISSN 2157-9679.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chow, Kai-wing (1997), "Imagining Boundaries of Blood: Zhang Binglin and the Invention of the Han 'Race' in Modern China", in Dikötter, Frank, The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, pp. 34–52, ISBN 962-209-443-0.

- Cohen, Alvin (2012). "Brief Note: The Origin of the Yellow Emperor Era Chronology" (PDF). Asia Major. 25 (pt 2): 1–13.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crompton, Louis (2003), Homosexuality and Civilization, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-02233-1.

- Dai, Yi 戴逸; Gong, Shuduo 龔書鐸, eds. (2003) (in zh), Zhongguo tongshi: xuesheng caitu ban 中國通史––學生彩圖版, 1. Shiqian, Xia, Shang, Xizhou 史前 夏 商 西周 [Prehistory, Xia, Shang, and Western Zhou] (illustrated for students ed.), Hong Kong: Zhineng jiaoyu chubanshe 智能敎育出版社 [Intelligence Press]

- Dikötter, Frank (1992), The Discourse of Race in Modern China, London: Hurst & Co, ISBN 1-85065-135-3, http://books.google.com/books?id=upZAGbGmneMC

- Duara, Prasenjit (1995), Rescuing History from the Nation: Questioning Narratives of Modern China, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-16722-0, http://books.google.com/books?id=ANsmE1gBRKsC

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1996), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43519-6.

- Fowler, Jeanine D. (2005). An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1845190866.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ge, Hong 洪葛 (2005), Gu, Jiu 顧久, ed., 抱朴子內篇, Taipei: Taiwan shufang chuban youxian gongsi 台灣書房出版有限公司, ISBN 978-986-7332-46-2.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2007), Beijing: A Concise History, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-39906-7.

- Hon, Tze-ki (2003), "National Essence, National Learning, and Culture: Historical Writings in Guocui xuebao, Xueheng, and Guoxue jikan", Historiography East & West 1 (2): 242–86, doi:.

- Hon, Tze-ki (2010), "From a Hierarchy in Time to a Hierarchy in Space: The Meanings of Sino-Babylonianism in Early Twentieth-Century China", Modern China 36 (2): 136–69.

- Huang, Dashou 黃大受 (1989) (in zh), Zhongguo tongshi 中國通史, Wunan tushu chuban gufen youxian gongsi 五南圖書出版股份有限公司, ISBN 978-957-11-0031-9.

- Jan, Yün-hua (1981), "The Change of Images: The Yellow Emperor in Ancient Chinese Literature", Journal of Oriental Studies 19 (2): 117–37.

- Kaske, Elizabeth (2008), The Politics of Language in Chinese Education, 1895–1919, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-16367-6.

- Lach, Donald F; van Kley, Edwin J (1994), Asia in the Making of Europe, III. A Century of Advance, Book Four, East Asia, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-46734-4.

- Lagerwey, John; Kalinowski, Marc (2008). Early Chinese Religion: Part One: Shang Through Han (1250 BC-220 AD). Early Chinese Religion. Brill. ISBN 9004168354.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - LeBlanc, Charles (1985–86), "A Re-examination of the Myth of Huang-ti", Journal of Chinese Religions 13–14: 45–63.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (1990), Sanctioned Violence in Early China, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-0076-X; 0-7914-0077-8.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2009), "The mythology of early China", in Lagerwey, John; Kalinowski, Mark, Early Chinese Religion: Part One: Shang through Han, Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 543–594, ISBN 978-90-04-16835-0.

- Liu, Li (1999), "Who were the ancestors? The origins of Chinese ancestral culture and racial myths", Antiquity 73 (281): 602–13.

- Mitarai, Masaru 御手洗 勝 (1967), "Kōtei densetsu ni tsuite 黃帝伝説について ["About the legend of the Yellow Emperor"]", Hiroshima daigaku bungaku kiyō 広島大学文学部紀要 ["Bulletin of the Literature Department of Hiroshima University"]' 27: 33–59.

- Mungello, David E. (1989) [1985], Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, ISBN 0-8248-1219-0.

- Nienhauser, William H Jr, ed. (1994), The Grand Scribe's Records, 1. The Basic Annals of Pre-Han China, Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University press, ISBN 0-253-34021-7.

- Puett, Michael (2001), The Ambivalence of Creation: Debates Concerning Innovation and Artifice in Early China, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-3623-5.

- Pulleybank, Edwin G (2000), "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity" (PDF), Early China 25: 1–27, http://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/earlychina/files/2008/07/ec25_pulleyblank.pdf.

- Sautman, Barry (1997), "Myths of Descent, Racial Nationalism and Ethnic Minorities in the People's Republic of China", in Dikötter, Frank, The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, pp. 75–95, ISBN 962-209-443-0.

- Schoenhals, Michael (2008), "Abandoned or Merely Lost in Translation?", Inner Asia 10 (1): 113–30, doi:.

- Seidel, Anna K (1969) (in fr), La divinisation de Lao Tseu dans le taoisme des Han, Paris: École française d'Extrême-Orient, ISBN 2-85539-553-4.

- Sterckx, Roel (2002), The Animal and the Daemon in Early China, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-5269-7, 0-7914-5270-0.

- Sun, Longji 孙隆基 (2000), "Qingji minzu zhuyi yu Huangdi chongbai zhi faming 清季民族主义与黄帝崇拜之发明", Lishi yanjiu 历史研究' 2000 (3): 68–79, http://www.lunw.com/thesis/123/16568_1.html.

- Tan, Zhong 譚中 (May 1, 2009), "Cong Ma Yingjiu 'yaoji Huangdi ling' kan Zhongguo shengcun shizhi 從馬英九「遙祭黃帝陵」看中國生存實質", Haixia pinglun 海峽評論' 221: 40–44.

- Veith, Ilza, ed. (2002), The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine, Foreword by Ken Rose, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-22936-3.

- Walters, Derek (2006), The Complete Guide to Chinese Astrology: The Most Comprehensive Study of the Subject Ever Published in the English Language, Watkins, ISBN 978-1-84293-111-0.

- Wang, Hengwei 王恒伟 (2005) (in zh), Zhongguo lishi jiangtang 中国历史讲堂, Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中华书局, ISBN 962-8885-24-3

- Wang, Zhongfu 王仲孚 (1997) (in zh), Zhongguo wenhua shi 中國文化史 ["Chinese cultural history"]', Wunan tushu chuban gufen youxian gongsi 五南圖書出版股份有限公司, ISBN 978-957-11-1427-9

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2013), Chinese History: A New Manual, Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-06715-8.

- Windridge, Charles; Fong, Cheng Kam (2003) [1999], Tong Sing: The Chinese Book of Wisdom Based on the Ancient Chinese Almanac, Kyle Cathie, ISBN 0-7607-4535-8.

- Wu, Kuo-cheng (1982), The Chinese Heritage, New York: Crown, ISBN 0-517-54475-X.

- Xu, Lai 徐来 (2008) (in zh), Xiangxiang zhong de dongwu: shanggu shidai de qiyi niaoshou 想象中的动物:上古时代的奇异鸟兽, Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi chubanshe 上海文艺出版社, ISBN 978-7-80685-826-4

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2013). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Routledge. ISBN 1135796343.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Two volumes: 1) A-L; 2) L-Z. - Ye, Shuxian 叶舒宪 (2007) (in zh), Xiong tuteng: Zhonghua zuxian shenhua tanyuan 熊图腾:中华祖先神话探源, Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi chubanshe 上海文艺出版社, ISBN 978-7-80685-826-4

- Sun, Xiaochun; Kistemaker, Jacob (1997). The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society. Brill. ISBN 9004107371.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yin, Wei 殷伟 (2001) (in zh), Zhongguo qinshi yanyi 中国琴史演义, Yunnan renmin chubanshe 云南人民出版社 [Yunnan People's Press]

- Zhao, Chunqing 赵春青; Qin, Wensheng 秦文生 (2002), "Yuanshi shehui: Dongfang de shuguang 原始社会:东方的曙光 [Primitive society: first light on the east]" (in zh), Zhonghua wenming chuanzhen 中華文明傳真, 1 of Liu Wei 刘炜, Shanghai: Shanghai cishu chubanshe 上海辞书出版社, ISBN 962-07-5314-3.

- Zhou, Jixu (2005). "Old Chinese "*tees" and Proto-Indo-European "*deus": Similarity in Religious Ideas and a Common Source in Linguistics" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. Victor H. Mair (167).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

للاستزادة

- Chow, Kai-wing (2001), "Narrating Nation, Race, and National Culture: Imagining the Hanzu Identity in Modern China", in Chow, Kai-wing; Doak, Kevin Michael; Fu, Poshek, Constructing Nationhood in Modern East Asia, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 47–84, ISBN 0-472-09735-0, 0-472-06735-4.

- von Falkenhausen, Lothar (2006), Chinese Society in the Age of Confucius (1000–250 BC): The Archaeological Evidence, Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, ISBN 1-931745-31-5.

- Von Glahn, Richard (2004), The Sinister Way: The Divine and the Demonic in Chinese Religious Culture, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-23408-1.

- Harper, Donald (1998), Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts, London and New York: Kegan Paul International, ISBN 0-7103-0582-6.

- Jochim, Christian (1990), "Flowers, Fruit, and Incense Only: Elite versus Popular in Taiwan's Religion of the Yellow Emperor", Modern China 16 (1): 3–38, doi:.

- Leibold, James (2006), "Competing Narratives of Racial Unity in Republican China: From the Yellow Emperor to Peking Man", Modern China 32 (2): 181–220, doi:.

- Luo, Zhitian 罗志田 (2002), "Baorong Ruxue, zhuzi yu Huangdi de Guoxue: Qingji shiren xunqiu minzu rentong xiangzheng de nuli 包容儒學、諸子與黃帝的國學:清季士人尋求民族認同象徵的努力 [The Rise of "National Learning": Confucianism, the Ancient Philosophers, and the Yellow Emperor in Chinese Intellectuals' Search for a Symbol of National Identity in the Late Qing]", Taida lishi xuebao 臺大歷史學報' 29: 87–105.

- Puett, Michael (2002), To Become a God: Cosmology, Sacrifice, and Self-Divinization in Early China, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 0-674-01643-2.

- Sautman, Barry (1997), "Racial nationalism and China's external behavior", World Affairs 160: 78–95, http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-20000642.html.

- Schneider, Lawrence (1971), Ku Chieh-gang and China's New History: Nationalism and the Quest for Alternative Traditions, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, http://books.google.com.hk/books?id=jIFVaJyJWaIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=ku+chieh-kang+and+china's+new+history&hl=zh-CN&ei=lP65Tt69EISGiQLAqd3hBA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=yellow%20emperor&f=false.

- Seidel, Anna K. (1987), "Traces of Han Religion in Funeral Texts Found in Tombs", in Akizuki, Kan'ei 秋月观暎, Dōkyo to shukyō bunka 道教と宗教文化 [Taoism and religious culture]', Tokyo: Hirakawa shuppansha 平和出版社, pp. 23–57.

- Shen, Sung-chiao 沈松橋 (1997), "Wo yi wo xue jian Xuan Yuan: Huangdi shenhua yu wan-Qing de guozu jiangou 我以我血薦軒轅: 黃帝神話與晚清的國族建構 [The myth of the Yellow Emperor and the construction of Chinese nationhood in the late Qing period]", Taiwan shehui yanjiu jikan 台灣社會研究季刊' 28: 1–77.

- Unschuld, Paul U (1985), Medicine in China: A History of Ideas, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-05023-1.

- Wang, Ming-ke 王明珂 (2002), "Lun Panfu: Jindai Yan-Huang zisun guozu jiangou de gudai jichu 論攀附:近代炎黃子孫國族建構的古代基礎 [On progression: the ancient basis for the nation-building claim that the Chinese are descendants of Yandi and Huangdi", Zhongyang yanjiu yuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo jikan 中央研究院歷史語言研究所集刊' 73 (3): 583–624, http://ultra.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/~origins/pages/book7.htm.

- Yates, Robin D.S. (1997), Five Lost Classics: Tao, Huang-Lao, and Yin-Yang in Han China, New York: Ballantine, ISBN 978-0-345-36538-5.

- Yi, Hua 易华 (2010), "Yao-Shun yu Yan-Huang: Shiji "Wudi benji" yu minzu rentong 尧舜与炎黄──《史记•五帝本记》与民族认同 [Yao-Shun and Yan-Huang: the Shiji's "Basic Annals of the Five Emperors" and ethnic identity", China Folkore Network, http://www.chinafolklore.org/web/index.php?Page=1&NewsID=8114.

الامبراطور الأصفر

| ||

| ألقاب ملكية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه ياندي |

إمبراطور أسطوري للصين ح. 2698 ق.م. – ح. 2598 ق.م. |

تبعه شاوهاو |

- CS1 errors: markup

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from November 2011

- CS1 errors: extra text: volume

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- حكام القرن 27 ق.م.

- حكام القرن 26 ق.م.

- أساطير صينية

- عازفو گوچين

- أشخاص من چوفو