روسيا في قطاع الطاقة الأوروپي

تزود روسيا كمية كبيرة من الوقود الأحفوري إلى بلدان أوروپية أخرى. عام 2021 كانت أكبر مصدر للنفط والغاز الطبيعي إلى الاتحاد الأوروپي،[1] حيث صدرت روسيا للاتحاد الأوروپي 155 بليون متر مكعب من الغاز الطبيعي، ما يشكل حوالي 45% من إجمالي صادرات الاتحاد الأوروپي من الغاز و40% من إجمالي إستهلاكه من الغاز.[2]

تقوم شركة گازپروم الروسية المملوكة للدولة بتصدير الغاز الطبيعي إلى أوروپا. كما تتحكم في العديد من الشركات التابعة لگازپروم، بما في ذلك أصول البنية التحتية المتنوعة.[بحاجة لمصدر] وفقًا لدراسة نشرها مركز أبحاث الدراسات الشرق أوروپية، أدى تحرير سوق الغاز في الاتحاد الأوروپي إلى توسع شركة گازپروم في أوروپا من خلال زيادة حصتها في سوق المصب الأوروپية. وأسست شركات فرعية للبيع في العديد من أسواق التصدير الخاصة بها، واستثمرت أيضًا في الوصول إلى القطاعات الصناعية وتوليد الطاقة في غرب ووسط أوروپا. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أسست گازپروم مشروعات مشتركة لبناء خطوط أنابيب الغاز الطبيعي ومستودعات التخزين في عدد من الدول الأوروپية.[3]

يشكل الاعتماد على الوقود الأحفوري الروسي مخاطر على أمن الطاقة بالنسبة لأوروپا..[4] في عدد من النزاعات، استخدمت روسيا عمليات إغلاق خطوط الأنابيب، مما دفع الاتحاد الأوروپي إلى تنويع مصادر الطاقة.[5] سيسمح التوسع السريع في مصادر الطاقة المتجددة في سوق الطاقة الأوروپية باستيراد أقل. كرد فعل، تعمل روسيا على توسيع قدراتها التصديرية تجاه الصين، حيث تمتلك خط أنابيب واحد فقط.[6][4] ردًا على الغزو الروسي لأوكرانيا، قدمت المفوضية الأوروپية والوكالة الدولية للطاقة خططًا مشتركة لتقليل الاعتماد على الطاقة الروسية، وتقليل واردات الغاز الروسي بمقدار اثنين الثلثين في غضون عام، وبشكل كامل بحلول عام 2030.[7][8]

التاريخ

بدأ تشغيل خط أنابيب دروژبا لتزويد الحلفاء في الكتلة الشرقية عام 1964.[9] كان خط أنابيب أورنگوي-پوماري-أوژهورود قد أنشيء في 1982-1984.[10] وهو مكمل لنظام نقل الغاز عبر القارات بين غرب سيبيريا وغرب أوروپا والذي كان قائماً منذ عام 1973. أقيمت مراسم الافتتاح الرسمي في فرنسا.[11] في أوائل الثمانينيات، كانت هناك جهود أمريكية، بقيادة إدارة ريگان، لإقناع الدول الأوروپية، التي كان من المقرر أن يتم من خلالها بناء خط أنابيب غاز سوڤيتي مقترح، لحرمان الشركات المسؤولة عن البناء من القدرة على شراء اللوازم والأجزاء لخط الأنابيب والمرافق المرتبطة به. كان رونالد ريگان يخشى أن تؤدي البنية التحتية لأنابيب الغاز الطبيعي الأوروپية التي يسيطر عليها الكرملين إلى زيادة نفوذ الاتحاد السوڤيتي ليس فقط في أوروپا الشرقية ، ولكن أيضًا في أوروپا الغربية. لهذا السبب ، خلال فترة ولايته الأولى في منصبه ، حاول - دون جدوى - وقف بناء أول خط أنابيب للغاز الطبيعي بين الاتحاد السوڤيتي وألمانيا. تم بناء خط الأنابيب على الرغم من هذه الاحتجاجات وظهور شركات الغاز الروسية الكبيرة مثل گازپروم بالإضافة إلى زيادة إنتاج الوقود الأحفوري الروسي، مما سهل التوسع الكبير في كمية الغاز الموردة إلى السوق الأوروپية منذ التسعينيات.[12]

منذ العقد الأول من القرن الحادي والعشرين، تحولت أسعار الغاز الطبيعي في أوروپا تدريجياً من أسعار العقود طويلة الأجل المستقرة إلى حد ما والتي ترتبط إلى حد كبير بسعر النفط، والتي دعمت الاستثمارات واسعة النطاق في تطوير حقول الغاز وخطوط الأنابيب، إلى التسعير التنافسي القائم على السوق. كان هذا التغيير مدفوعًا بلائحة الاتحاد الأوروپي، والانتقال من حصة سعر السوق بنسبة 30% عام 2010 إلى 80% عام 2020، مما أدى إلى توفير ما يقدر بنحو 70 مليار دولار أمريكي على دول الاتحاد الأوروپي خلال العقد الأول من القرن الحادي والعشرين مدفوعًا إلى حد كبير بتطوير الغاز الصخري. ومع ذلك، وبسبب أزمة الطاقة العالمية 2021، قدرت وكالة الطاقة الدولية أن التكلفة الإجمالية لواردات الاتحاد الأوروپي من الغاز عام 2021 ستكون أعلى بحوالي 30 مليار دولار في ذلك العام مما كانت عليه في ظل نظام التسعير السابق.[13][14]

في سبتمبر 2012، فتحت المفوضية الأوروپية إجراءات رسمية للتحقيق فيما إذا كانت گازپروم تعوق المنافسة في أسواق الغاز في وسط وشرق أوروپا، في انتهاك لقانون المنافسة في الاتحاد الأوروپي. على وجه الخصوص، نظرت اللجنة في استخدام گازپروم لبنود "عدم إعادة البيع" في عقود التوريد، والمنع المزعوم لتنويع إمدادات الغاز، وفرض أسعار غير عادلة من خلال ربط أسعار النفط والغاز في العقود طويلة الأجل.[15] ردت روسيا الاتحادية بإصدار قانون حظر، والذي أدخل قاعدة افتراضية تحظر على الشركات الاستراتيجية الروسية، بما في ذلك گازپروم، الامتثال لأي إجراءات أو طلبات أجنبية.[16]

يخضع الامتثال للإذن المسبق الممنوح من قبل الحكومة الروسية.

عام 2013، كانت حصص الغاز الطبيعي الروسي في استهلاك الغاز المحلي في دول الاتحاد الأوروپي كما يلي:[17]

إستونيا 100%

إستونيا 100% فنلندا 100%

فنلندا 100% لاتڤيا 100%

لاتڤيا 100% لتوانيا 100%

لتوانيا 100% سلوڤاكيا 100%

سلوڤاكيا 100% بلغاريا 97%

بلغاريا 97% المجر 83%

المجر 83% سلوڤنيا 72%

سلوڤنيا 72% اليونان 66%

اليونان 66% التشيك 63%

التشيك 63% النمسا 62%

النمسا 62% پولندا 57%

پولندا 57% ألمانيا 46%

ألمانيا 46% إيطاليا 34%

إيطاليا 34% فرنسا 18%

فرنسا 18% هولندا 5%

هولندا 5% بلجيكا 1.1%

بلجيكا 1.1%

Gas for northern Europe largely came from the Nadym Pur Taz (NPT) region in Western Siberia, but these large fields are now in decline due to depletion. Since the early 2010s Gazprom has been developing replacement gas fields in the Yamal Peninsula area of the Russian Arctic. As of 2020, Yamal produces over 20% of Russia's gas, which is expected to increase to 40% by 2030. The shortest pipeline routes from Yamal to the northern EU countries are the Yamal–Europe pipeline through Poland and Nord Stream to Germany. During the winter peak Gazprom does not have the capacity to redirect flows to the central pipeline corridor through Ukraine, built for the NPT gas flow. Gazprom intends to decommission some pipelines, over forty years old with high maintenance costs, in the central corridor as NPT production declines.[18]

In 2017, energy products accounted for around 60% of the EU's total imports from Russia.[19] 30% of the EU's petroleum oil imports and 39% of total gas imports came from Russia in 2017. For Estonia, Poland, Slovakia and Finland, more than 75% of their imports of petroleum oils originated in Russia.[19]

In response to the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the European Commission and International Energy Agency presented a plan to reduce gas imports from Russia by two thirds within a year, and completely by 2030.[7][8]

Prices of many minerals and metals that are essential for clean energy technologies have recently soared due to a combination of rising demand, disrupted supply chains and concerns around tightening supply. The global prices of lithium and cobalt more than doubled in 2021, and those for copper, nickel and aluminium all rose by around 25% to 40%.[20]

The price trends have continued into 2022. The price of lithium has increased an astonishing two-and-a-half times from January to May 2022. The prices of nickel and aluminium – for which Russia is a key supplier – have also kept rising, driven in part by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For most minerals and metals that are vital to the clean energy transition, the price increases since 2021 exceed by a wide margin the largest annual increases seen in the 2010s.[20]

Russia also provides 43% of global supplies of palladium, a precious material used for catalytic converters in cars. Europe accounts for over half of Russia’s palladium exports. As with aluminium, stock levels were already low before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Automakers can switch to platinum, but Russia is also a major producer of that, with a 14% share, the second largest in the world.[20]

توصيل الغاز الطبيعي

In 2021, 45% of the European Union's natural gas total imports originated in Russia.[21] As of 2009, Russian natural gas was delivered to Europe through 12 pipelines, of which three were direct pipelines (to Finland, Estonia and Latvia), four through Belarus (to Lithuania and Poland) and five through Ukraine (to Slovakia, Romania, Hungary and Poland).[22] In 2011, an additional pipeline, Nord Stream (directly to Germany through the Baltic Sea), opened.[23]

The largest importers of Russian gas in the European Union are Germany and Italy, accounting together for almost half of the EU's gas imports from Russia. Other larger Russian gas importers in the European Union are France, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland, Austria and Slovakia.[24][25] The largest non-EU importers of Russian natural gas are Turkey and Belarus.[24]

In 2017 Russia became one of the main liquefied natural gas (LNG) suppliers to Europe, mostly from Yamal LNG which started operations in 2017, in addition to pipeline supplies. In 2018 about 6% of Russian gas supply to Europe was as LNG.[18]

In response to Russian military buildup and recognition of Ukrainian separatists, Germany cancelled opening of the Nord Stream 2 in February 2022. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine prompted Western sanctions, leading to a currency crisis in Russia. The 2022 Russia–European Union gas dispute broke out in April, with Russia demanding to be paid in Russian rubles and cutting off natural gas deliveries to Poland and Bulgaria when those countries refused to allow alteration of gas contracts.

عدم استقرار الإمدادات 2021-22

The reliance of the European Union and, indirectly, the United Kingdom on Russian gas supplies has increased over the last decade. Natural gas consumption in the EU and UK overall remained broadly flat in over this period, but production fell by a third and the gap has been filled by increased imports. Consequently, the share of Russian gas supplies increased from 25% of the region’s total gas demand in 2009 to 32% in 2021.[26]

Russia also has a wide-reaching gas export pipeline network, both via transit routes through Belarus and Ukraine, and via pipelines sending gas directly into Europe (including Nord Stream, Blue Stream, and TurkStream pipelines) all. Russia completed work on the Nord Stream II pipeline in 2021, but the German government decided not to approve certification in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[27] Meanwhile, the importance of Ukraine as a transit country has lessened due to the build-up of additional transit corridors bringing Russian piped gas to the EU and UK (e.g. Nord Stream). Transit flows via Ukraine accounted for over 25% of Russia’s pipeline deliveries to the EU and UK in 2021, significantly down from more than 60% in 2009. Nevertheless, Ukraine remains an important conduit for Russian gas to Europe. About 8% of the EU and UK combined gas demand transits through Ukraine, and the country also relies heavily on imported gas for its own domestic use.[26]

Over the course of 2021 and the beginning of 2022, Russia created an ‘artificial tightness’ in European gas markets. The Russian state-owned Gazprom reduced its piped gas supplies to the EU market by 25% in the fourth quarter of 2021 compared to the same period in 2020.[28][26] This decrease in Russian pipeline supply to the EU became more pronounced in the first seven weeks of 2022, falling by 37% compared to the previous year. The last pipeline deliveries to Germany via the Yamal pipeline which goes through Belarus, occurred on 20 December 2021. Gas flows via Ukraine to Slovakia fell from an average of over 80 mcm/d in December 2021 to just 36 mcm/d in the first seven weeks of 2022. Altogether, Russian gas flows via Ukraine averaged only half of the contractually available capacity.[26]

Other pipeline suppliers, including Algeria, Azerbaijan and Norway, increased their deliveries during the heating season to the European market compared with last year, using commercially available supply routes. Lower Russian pipeline flows were compensated in part by higher liquefied natural gas (LNG) inflows to the EU and the UK, which reached an all-time high of 13 bcm in January – almost three times their last year’s levels and about 70% higher compared to Russian pipeline flows that month. Strong supply and milder-than-expected temperatures in Northeast Asia helped to facilitate the redirection of cargoes towards Europe and limit the implications of strong European demand for LNG markets. The United States supplied over half of the additional LNG imported by the EU and UK since the beginning of the heating season. This highlights the importance of the US LNG export industry to European energy security.[26] In 2021, the Russian government released a long-term LNG development plan, with the goal of expanding its LNG capacity in order to compete with growing LNG exports from the United States, Australia, and Qatar.[27]

Russia has also been reducing its piped gas supplies to the EU market, while choosing not fill its storage sites in the EU to adequate levels, even in the middle of the heating season in the fourth quarter of 2021 and in early 2022.[29][26] As a consequence of low inventory levels at the beginning of the heating season, and the sharp decline of Russian piped flows to the EU, European gas storage levels fell to 30% below their working storage capacity (and standing 28% below their 5-year average levels for this period of the year). Storage sites owned or controlled by Gazprom, the Russian state-owned energy corporation, had particularly low storage levels at the start of the heating season, filled to just 25% of their working storage capacity. While Gazprom storages account for just 10% of the EU total working storage capacity, they accounted for half of the EU’s 5-year storage deficit. Without the strong increase in LNG imports since October 2021, European storage levels would have been less than 15% full by February 2022 (vs 31% in reality), leaving Europe in a much more vulnerable position vis-à-vis late cold spells or supply disruptions.[26] For context, expert analysis suggests that fill levels of at least 90% of working storage capacity by 1 October are necessary to provide an adequate buffer for the European gas market through the winter heating season.[8]

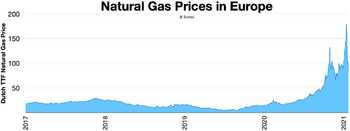

In late 2021, European natural gas prices rose to all-time highs and remained extremely volatile into 2022. These reduced Russian pipeline flows, together with low storage levels and adverse weather conditions, contributed to strong upward pressure on prices in Europe, which averaged more than $30 USD per million BTUs (MMBtu) in the fourth quarter of 2021. Natural gas prices moderated down to an average of $27/MMBtu in the first seven weeks of 2022. Unseasonably mild weather conditions led to a slight decrease in demand (declining by 14% year-on-year according to preliminary estimates), and a 20% increase in wind energy output in the first quarter of 2022 reduced gas burn in the power sector.

Nonetheless, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, European natural gas prices surged by 50% day-on-day, reaching to $44/MMBtu, following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. On 26 April, Russia announced it would cut off natural gas exports to Poland and Bulgaria, as a part of a series of disputes over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. On 21 May, Russia halted all of its gas exports to Finland.[30] Natural gas prices are expected to remain extremely volatile in the current context of market uncertainty.[26][31] As a result of the invasion, Brent oil prices rose above $130 a barrel for the first time since 2008.[32]

النزاعات وجهود التنويع

On the eve of the 2006 Riga summit, Senator Richard Lugar, head of the U.S. Senate's Foreign Relations Committee, declared that "the most likely source of armed conflict in the European theatre and the surrounding regions will be energy scarcity and manipulation."[34] After that, the variety of national policies and stances of larger exporters versus larger dependents of Russian natural gas, together with the segmentation of the European natural gas market, became a prominent issue in European politics toward Russia, with significant geopolitical implications for economic and political ties between the EU and Russia.[35]

These ties led to calls for greater European energy diversity, although such efforts are complicated by the fact that many European customers have long term legal contracts for gas deliveries despite the disputes, most of which stretch beyond 2025–2030.[35]

A number of disputes over the natural gas prices in which Russia was using pipeline shutdowns in what was described as "tool for intimidation and blackmail"[36] caused the European Union to significantly increase efforts to diversify its energy sources.[5] Some even argued that Russia has developed "the capacity to use unilateral economic sanctions in the form of natural gas pricing and gas disruptions against many European North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member states".[12] During an anti-trust investigation initiated in 2011 against Gazprom, a number of internal company documents were seized that documented a number of "abusive practices" in an attempt to "segment the internal [EU] market along national borders" and impose "unfair pricing".[37]

Part of the aim of the Energy Union is to diversify the EU’s gas supplies away from Russia, which has already proved to be an unreliable partner, first in 2006 and then in 2009, and which threatened to become one again at the outbreak of the conflict in Ukraine in 2013–2014.

The Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany was opposed by former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, former U.S. President Donald Trump and then British Foreign Secretary and later prime minister Boris Johnson.[38][39] The United States has been encouraging European countries to diversify Russian-dominated energy supplies, with Qatar as possible alternative supplier.[40]

To compare with alternative sources, Germany produced 10.5% of its electricity from natural gas in 2019 and 8.6% (44 TWh) from renewable biomass, largely biogas.[41] As only 13% of Germany's gas use was for power production,[42] this replaced just above 1 percent of its overall gas consumption.

In January 2020 Russia temporarily halted oil deliveries to Belarus over another price dispute.[43]

Due to a combination of unfavourable conditions, which involved soaring demand of gas, less power generation by alternative sources, and cold winter that left European and Russian reserves depleted, Europe faced steep increases in gas prices in 2021.[44] In August 2021 Russia reduced volumes of gas sent to European Union,[45][46] which was seen by some analysts and politicians as an attempt to "support its case in starting flows via Nord Stream 2".[47] The record-high prices in Europe were driven by a global surge in demand as the world quit the economic recession caused by COVID-19, particularly due to strong energy demand in Asia,[48][49] as well as lowered supplies of natural gas from Russia to the European Union.[50]

Russia has fully supplied on all long-term contracts, but has not supplied additional gas on the spot market.[51] In October 2021, the Economist Intelligence Unit reported that Russia had limited extra gas export capacity because of high domestic requirements with production near its peak.[51][52] In January–June Gazprom supplied about 22% more gas to Europe (including Turkey) in 2021 than the same months in 2020, and almost the same amount as in 2019. Algeria also increased supplies in 2021H1, but other countries supplied less than in 2020H1.[18]

In September 2021 Russia announced that "rapid" start up of the newly completed Nord Stream 2 pipeline that had long been contested by various EU countries would resolve the problems.[53] These statements were interpreted by some analysts as a "blackmail" attempt.[54] 40 members of the European Parliament requested a legal inquiry into the Gazprom practices.[55][56] In October 2021, Russian President Putin said that one of the factors influencing the prices was the termination of long-term supply contracts in favour of the spot market,[57] while Gazprom announced it was accumulating "record" reserves of 72.6 billions m3 and continued record production at 847.9 millions m3 per day.[58] On 27 October 2021, Putin ordered Gazprom to start pumping natural gas into European gas storage sites once Russia finished filling its own gas storage sites, by about 8 November.[59][60]

The former Lithuanian Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius, who is European Parliament's rapporteur on relations with Russia, said it is "impossible" to have good relations with Russia and called for the EU to phase out its imports of oil and natural gas from Russia.[61] A group of five EU member countries have called for joint action, such as group purchases.[62]

On 7 March 2022, German chancellor Olaf Scholz and other European leaders pushed back against the call by the US and Ukraine to ban imports of Russian gas and oil because "Europe's supply of energy for heat generation, mobility, power supply and industry cannot be secured in any other way".[63][64] However, the EU indicated that it would cut its gas dependency on Russia by two-thirds in 2022,[65] and Germany stated that it would reduce its dependence on Russian energy imports by accelerating renewables and reaching 100% renewable energy generation by 2035.[66][67]

Scholz announced plans to build two new LNG terminals.[68] Economy Minister Robert Habeck said Germany reached a long-term energy partnership with Qatar,[69] one of the world's largest exporters of liquefied natural gas,[70]

In April 2022, Russia supplied 45% of EU's gas imports, earning $900 million a day.[71] In the first two months after Russia invaded Ukraine, Russia earned $66.5 billion from fossil fuel exports, and the EU accounted for 71% of that trade.[72] In May 2022, the European Commission proposed a ban on oil imports from Russia, part of the economic response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[73][74] In May 2022, Russia imposed sanctions on European subsidiaries of Gazprom.[75]

In June 2022, the United States government agreed to allow Italian company Eni and Spanish company Repsol to import oil from Venezuela to Europe to replace oil imports from Russia.[76] French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said that France negotiated with the United Arab Emirates to replace some Russian oil imports.[76]

پولندا

As part of Poland's plans to become fully energy independent from Russia within the next years, Piotr Wozniak, president of state-controlled oil and gas company PGNiG, stated in February 2019: "The strategy of the company is just to forget about Eastern suppliers and especially about Gazprom."[77] In 2020, the Stockholm Arbitral Tribunal ruled that PGNiG's long-term contract gas price with Gazprom linked to oil prices should be changed to approximate the Western European gas market price, backdated to 1 November 2014 when PGNiG requested a price review under the contract.[78][79]

Gazprom had to refund about $1.5 billion to PGNiG. The 1996 Yamal pipeline related contract is for up to 10.2 billion cubic metres of gas per year until it expires in 2022, with a minimum annual amount of 8.7 billion cubic metres.[80][81] Following the 2021 global energy crisis, PGNiG made a further price review request on 28 October 2021. PGNiG stated the recent extraordinary increases in natural gas prices "provides a basis for renegotiating the price terms on which we purchase gas under the Yamal Contract."[82][83]

On 17 November 2021 Belarus has stopped oil supplies over the Druzhba pipeline to Western Europe for "unscheduled maintenance"[84][85] which happened amidst the Belarus border crisis[86] and one day after Germany suspended certification of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline.[87]

The Baltic Pipe between Norway and Poland will have the capacity to replace the roughly 60% of Polish gas imports coming from Russia via the Yamal pipeline, and is expected to be operational by the end of 2022.[88][معلومات قديمة]

On 26 April, Russia announced it would cut off natural gas exports to Poland and Bulgaria, as a part of a series of disputes over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[31]

أسواق الكهرباء قبل غزو أوكرانيا

The turmoil in natural gas markets in 2021 and 2022 spilled over into European electricity markets, which typically rely on gas as a marginal fuel and are therefore affected when it experiences high prices and volatility. This has been exacerbated by lower than average hydropower output and lower nuclear output highlighting the need for adequate investment in sources of baseload supply and flexibility. While higher carbon prices have also played a role in pushing up electricity prices, it has not been the most significant factor. The International Energy Agency estimates that the effect on European electricity prices of the sharp spike in natural gas prices is nearly eight times bigger than the effect of the increase in carbon prices. Although wind power was unusually below average during the European summer, wind and solar PV provided valuable contributions to meeting European electricity demand in the fourth quarter of 2021. Wind power generation increased by 3% and solar by 20% compared with the same period a year earlier.[28]

إمدادات الوقود النووي

Ukraine has been traditionally sourcing fuel for its nuclear power plants from Russia, although with the outbreak of Russian military intervention in Donbass it saw an urgent need to at least diversify supplies of fuel and started talks with a number of Western suppliers, most notably Westinghouse branch in Sweden. In response, Russia started an intimidation campaign which included supplying deliberately incorrect technical specifications of the existing fuel supplies, alluding to "second Chernobyl" and staging protests in Kyiv. In spite of these efforts, Ukraine secured a number of framework contracts with numerous suppliers, eventually supplying 50% of the fuel from Russia and 50% from Sweden.[89]

انظر أيضاً

- سياسة الطاقة في روسيا

- سياسة الطاقة في الاتحاد الأوروپي

- العلاقات الخارجية لروسيا

- عمليات النفوذ الروسي

- البلدان الأوروپية حسب استخدام الوقود الأحفوري (% من إجمالي الطاقة)

- البلدان الأوروپية استهلاك الكهرباء للفرد

- قائمة البلدان حسب صادرات الغاز الطبيعي

- قائمة البلدان حسب واردات الغاز الطبيعي

- قائمة البلدان حسب الاحتياطيات المحققة من الغاز الطبيعي

المصادر

- ^ "EU imports of energy products - recent developments". ec.europa.eu (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-03-05.

- ^ "How Europe can cut natural gas imports from Russia significantly within a year". الوكالة الدولية للطاقة. 2022-03-03. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- ^ Koszalin, Andreas Heinrich (5 February 2008). "Gazprom's Expansion Strategy in Europe and the Liberalization of EU Energy Markets" (PDF). Russian Analytical Digest. Research Centre for East European Studies (34 Russian Business Expansion). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- ^ أ ب Chandrasekhar, Aruna (2022-02-25). "Q&A: What does Russia's invasion of Ukraine mean for energy and climate change?". Carbon Brief (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- ^ أ ب "Europe's alternatives to Russian gas". European Council of Foreign Relations. 9 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ Birnbaum, Michael; Mufson, Steven (24 February 2022). "E.U. will unveil a strategy to break free from Russian gas, after decades of dependence". Washington Post (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- ^ أ ب Weise, Zia (8 March 2022). "Commission plans to get EU off Russian gas before 2030". POLITICO.

- ^ أ ب ت International Energy Agency (March 2022). "A 10-Point Plan to Reduce the European Union's Reliance on Russian Natural Gas". IEA. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "The Soviet pipeline that keeps Europe hooked on Moscow's oil". Financial Times. 15 March 2022.

- ^ "Analysis: The Recurring Fear Of Russian Gas Dependency". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 11 May 2006.

- ^ "History of the gas branch". Gazprom. Archived from the original on 2007-06-13.

- ^ أ ب Iftimie, Ion (22 January 2015). Natural Gas as an Instrument of Russian State Power (Second edition, fully revised and updated ed.). Washington, D.C.: Westphalia Press. p. 74. ISBN 9781633911390. OCLC 908407323.

- ^ Marson, James; Wallace, Joe (27 October 2021). "Europe's Push to Loosen Russian Influence on Gas Prices Bites Back". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Zeniewski, Peter (22 October 2021). "Despite short-term pain, the EU's liberalised gas markets have brought long-term financial gains". International Energy Agency. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ European Commission, Antitrust: Commission Opens Proceedings Against Gazprom, IP/12/937

- ^ Marek Martyniszyn, Legislation Blocking Antitrust Investigations and the September 2012 Russian Executive Order, 37(1) World Competition 103 (2014)

- ^ Jones, Dave; Dufour, Manon; Gaventa, Jonathan (June 2015). "Europe's Declining Gas Demand: Trends and Facts about European Gas Consumption" (PDF). E3G. p. 9. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت Yermakov, Vitaly (September 2021). Big Bounce: Russian gas amid market tightness. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Russian-gas-amid-market-tightness.pdf. Retrieved on 1 November 2021. - ^ أ ب "EU imports of energy products - recent developments" (PDF). Eurostat. 4 July 2018. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت Kim, Tae-Yoon (18 May 2022). "Critical minerals threaten a decades-long trend of cost declines for clean energy technologies". Paris: International Energy Agency. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:3 - ^

"Commission staff working document–Accompanying document to the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning measures to safeguard security of gas supply and repealing Directive 2004/67/EC. Assessment report of directive 2004/67/EC on security of gas supply {COM(2009) 363}". European Commission. 16 July 2009: 33, 56, 63–76. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Juergen Baetz (8 November 2011). "Merkel, Medvedev inaugurate new gas pipeline". Associated Press. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ أ ب

"Country analysis briefs: Russia" (PDF). Energy Information Administration. May 2008: 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^

Noël, Pierre (May 2009). "A Market Between Us: Reducing the Political Cost of Europe's Dependence on Russian Gas" (PDF). EPRG Working Paper Series. University of Cambridge Electricity Policy Research Group: 2; 38. EPRG0916. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د International Energy Agency (26 February 2022). "Gas Market and Russian Supply". IEA.

- ^ أ ب International Energy Agency (21 March 2022). "Energy Fact Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?". IEA. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ أ ب Birol, Fatih (13 January 2022). "Europe and the world need to draw the right lessons from today's natural gas crisis". International Energy Agency. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ International Energy Agency (21 September 2021). "Statement on recent developments in natural gas and electricity markets". IEA. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia halts gas supplies to Finland". BBC News (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 2022-05-21. Retrieved 2022-06-16.

- ^ أ ب "Ukraine war: Russia halts gas exports to Poland and Bulgaria". BBC News (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 2022-04-27. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Disavino, Scott (7 March 2022). "Oil price surges to highest since 2008 on delays in Iranian talks". Reuters.

- ^ "Germany's Angela Merkel slams planned US sanctions on Russia". Deutsche Welle. 16 June 2017.

- ^ Energy security challenges for the 21st century : a reference handbook. Luft, Gal., Korin, Anne. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger Security International. 2009. ISBN 9780275999988. OCLC 522747390.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ أ ب Simon Pirani; Jonathan Stern; Katja Yafimava (February 2009). The Russo-Ukrainian gas dispute of January 2009: a comprehensive assessment (PDF). Vol. NG 27. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-901795-85-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (27 October 2006). "Lithuania suspects Russian oil grab". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ "EU documents lay bare Russian energy abuse" (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ "Germany and Russia gas links: Trump is not only one to ask questions". The Guardian. 11 July 2018.

- ^ "Trump barrels into Europe's pipeline politics". Politico. 11 July 2018.

- ^ "U.S. wants Qatar to challenge Russian natural gas in Europe -U.S. official". Reuters. 14 January 2019.

- ^ Der deutsche Strommix: Stromerzeugung in Deutschland https://strom-report.de/strom/ Retrieved 7 September 2020

- ^ Anteil der Verbrauchergruppen am Erdgasabsatz in Deutschland in den Jahren 2009 und 2019 https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/37985/umfrage/verbrauch-von-erdgas-in-deutschland-nach-abnehmergruppen-2009/ Retrieved 7 September 2020

- ^ "Russia turns off oil taps supplying Belarus". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- ^ "Russia says it could boost supplies to ease Europe gas costs". Associated Press. 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Europe's gas shortage could make the whole world pay more to get warm this winter". CNBC. 13 September 2021.

- ^ "Is Europe's gas and electricity price surge a one-off?". Bruegel. 13 September 2021.

- ^ "Russia is pumping a lot less natural gas to Europe all of a sudden — and it is not clear why – Gas Watch" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2021-08-24. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- ^ Ambrose, Jillian (19 September 2021). "UK energy market crisis: what caused it and how does it affect my bills?". The Guardian.

- ^ Valle, Sabrina (10 September 2021). "Asian spot prices hit all-time seasonal high". Reuters.

- ^ "Europe's soaring gas prices: does Russia hold solution to crisis?". the Guardian (in الإنجليزية). 2021-10-07.

- ^ أ ب Horton, Jake (14 October 2021). "Europe gas prices: How far is Russia responsible?". BBC News.

- ^ Mazneva, Elena (3 September 2021). "Russia Has a Gas Problem Nearly the Size of Exports to Europe". Bloomberg.

- ^ "Russia's Gazprom says Europe gas prices could set new records". Reuters. 17 September 2021.

- ^ "Europe is under attack from Putin's energy weapon". Atlantic Council (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2021-10-01. Retrieved 2021-10-05.

- ^ "[Exclusive] MEPs suspect Gazprom manipulating gas price". EUobserver (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-09-29.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Gazprom: EU lawmakers urge probe over soaring prices | DW | 17.09.2021". DW.COM (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Retrieved 2021-09-29.

- ^ "Putin promises gas to a Europe struggling with soaring prices". Politico. 13 October 2021.

- ^ ""Газпром" создаст рекордный резерв газа в подземных хранилищах". РБК (in الروسية). Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ^ "Russia seen starting to fill Europe's gas storage after Nov. 8". Euronews. 27 October 2021.

- ^ "Putin Orders More Gas for Europe Next Month, Sending Down Price". Bloomberg. 27 October 2021.

- ^ "EU Parliament touts Russia oil, gas import phase-out". Argus Media. 16 September 2021.

- ^ www.ETEnergyworld.com. "EU member states call for joint action as energy prices surge - ET EnergyWorld". ETEnergyworld.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-10-05.

- ^ Von Der Burchard, Hans; Sugue, Merlin (7 March 2022). "Germany's Scholz rejects calls to ban Russian oil and gas". Politico.

- ^ Kemp, John (27 March 2022). "Column: EU steps back from impractical Russia oil embargo". Reuters.

- ^ "EU unveils plan to reduce Russia energy dependency". Deutsche Welle. 8 March 2022.

- ^ Storrow, Benjamin (4 March 2022). "Will the Russian Invasion Accelerate Peak Oil?". Scientific American.

- ^ "Will the Ukraine war derail the green energy transition?". Financial Times. 8 March 2022.

- ^ "German minister heads to Qatar to seek gas alternatives". Deutsche Welle. 19 March 2022.

- ^ "Germany Signs Energy Deal With Qatar As It Seeks To reduce Reliance On Russian Supplies". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 20 March 2022.

- ^ "Germany goes on a mission to secure supplies of Qatari gas". Euractiv. 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Missiles fly, but Ukraine's pipeline network keeps Russian gas flowing to Europe". CBC News. 12 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia has made $66 billion from fuel exports since it invaded Ukraine - and the EU is still its biggest buyer, study finds". Business Insider. 28 April 2022.

- ^ Bill Chappell (4 May 2022). "The EU just proposed a ban on oil from Russia, its main energy supplier". NPR.

- ^ "EU oil ban adds pressure on Russia but obstacles remain: Analysts". Al Jazeera. 12 May 2022.

- ^ "Europe faces gas supply disruption after Russia imposes sanctions". Al Jazeera. 12 May 2022.

- ^ أ ب "Oil from sanctioned Venezuela to help Europe replace Russian crude as soon as next month: report". Business Insider. 5 June 2022.

- ^ Reed, Stanley (2019-02-26). "Burned by Russia, Poland Turns to U.S. for Natural Gas and Energy Security". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Barteczko, Agnieszka (31 March 2020). "Poland's PGNiG to take immediate steps to receive $1.5 billion from Gazprom". Reuters.

- ^ "Victory for PGNiG: the Arbitral Tribunal in Stockholm rules to lower the price of the gas sold by Gazprom to PGNiG". PGNiG (Press release). 20 March 2020.

- ^ Barteczko, Agnieszka (31 March 2020). "Poland's PGNiG to take immediate steps to receive $1.5 billion from Gazprom". Reuters.

- ^ "Victory for PGNiG: the Arbitral Tribunal in Stockholm rules to lower the price of the gas sold by Gazprom to PGNiG". PGNiG (Press release). 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Polish PGNiG asks Gazprom to reduce gas prices under Yamal contract". TASS. Moscow. 28 October 2021.

- ^ "PGNiG files request for price reduction under Yamal Contract". PGNiG (Press release). 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Belarus restricts oil supplies to Poland due to unscheduled maintenance". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). 2021-11-17. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ^ "Belarus Stopped Supplying Oil Via "Druzhba" To Poland". charter97.org (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ^ Anonym. "Belarus blocks oil transit to Poland | txtreport.com". www.txtreport.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ^ "Nord Stream 2: Gas prices soar after setback for Russian pipeline". BBC News (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 2021-11-16. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ^ Easton, Adam (26 April 2022). "Russia halts gas supplies to Poland, reports say". BBC News. Warsaw. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "Kärnfrågan". Fokus (in السويدية). 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

المراجع

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 Licence statement: Gas Market and Russian Supply, International Energy Agency, the International Energy Agency.

To learn how to add open-license text to Wikipedia articles, please see Wikipedia:Adding open license text to Wikipedia.

For information on reusing text from Wikipedia, please see the terms of use.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 Licence statement: Europe and the world needs to draw the right lessons from today's natural gas crisis, Fatih Birol, the International Energy Agency.

To learn how to add open-license text to Wikipedia articles, please see Wikipedia:Adding open license text to Wikipedia.

For information on reusing text from Wikipedia, please see the terms of use.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 Licence statement: A 10-Point Plan to Reduce the European Union's Reliance on Russian Natural Gas, International Energy Agency, the International Energy Agency.

To learn how to add open-license text to Wikipedia articles, please see Wikipedia:Adding open license text to Wikipedia.

For information on reusing text from Wikipedia, please see the terms of use.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 Licence statement: Critical minerals threaten a decades-long trend of cost declines for clean energy technologies, Kim Tae-Yoon, the International Energy Agency.

To learn how to add open-license text to Wikipedia articles, please see Wikipedia:Adding open license text to Wikipedia.

For information on reusing text from Wikipedia, please see the terms of use.

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 maint: others

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- CS1 السويدية-language sources (sv)

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2022

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Wikipedia articles in need of updating from أكتوبر 2022

- Free-content attribution

- Free content from the International Energy Agency

- سياسة جغرافية

- سياسة الاتحاد الأوروپي

- الطاقة في الاتحاد الأوروپي

- سياسات ومبادرات الطاقة في الاتحاد الأوروپي

- الطاقة في أوروپا

- الطاقة في روسيا

- العلاقات الأوروپية الروسية

- گازپروم