الإعدام في الولايات المتحدة

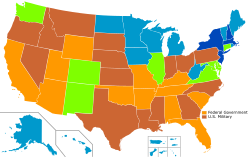

In the United States, capital punishment (killing a person as punishment for allegedly committing a crime) is a legal penalty throughout the country at the federal level, in 27 states, and in American Samoa.[ب][1] It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in 23 states and in the federal capital, Washington, D.C.[2] It is usually applied for only the most serious crimes, such as aggravated murder. Although it is a legal penalty in 27 states, 19 of them have authority to execute death sentences, with the other 8, as well as the federal government and military, subject to moratoriums.

As of 2023, of the 38 OECD member countries, only two (the United States and Japan) allow capital punishment.[3] Taiwan is the only other advanced democracy with capital punishment, but its constitutional court could strike it down when it rules on its constitutionality by the fall of 2024.[4]

The existence of capital punishment in the United States can be traced to early colonial Virginia.[5] There were no executions in the United States between 1967 and 1977. In 1972, the Supreme Court of the United States struck down capital punishment statutes in Furman v. Georgia, reducing all pending death sentences to life imprisonment at the time.[6] Subsequently, a majority of states enacted new death penalty statutes, and the court affirmed the legality of the practice in the 1976 case Gregg v. Georgia. Since then, more than 8,700 defendants have been sentenced to death;[7] of these, more than 1,550 have been executed.[8][9] At least 190 people who were sentenced to death since 1972 have since been exonerated, about 2.2% or one in 46.[10][11] As of April 13, 2022, about 2,400 to 2,500 convicts are still on death row.[12]

The Trump administration's Department of Justice announced its plans to resume executions for federal crimes in 2019. On July 14, 2020, Daniel Lewis Lee became the first inmate executed by the federal government since 2003.[13] Thirteen federal death row inmates have been executed since federal executions resumed in July 2020, all under Trump. The last and most recent federal execution was of Dustin Higgs, who was executed on January 16, 2021.[14] On July 1, 2021, Attorney General Merrick Garland announced that a moratorium on the federal death penalty was being reinstated.[15]

اعتبارا من مارس 2024[تحديث], there were 42 inmates on federal death row.[16]

History

Pre-Furman history

The first recorded death sentence in the British North American colonies was carried out in 1608 on Captain George Kendall,[17] who was executed by firing squad[18] at the Jamestown colony for spying on behalf of the Spanish government.[19] Executions in colonial America were also carried out by hanging. The hangman's noose was one of the various punishments the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony applied to enforce religious and intellectual conformity on the whole community.[20]

The Bill of Rights adopted in 1789 included the Eighth Amendment which prohibited cruel and unusual punishment. The Fifth Amendment was drafted with language implying a possible use of the death penalty, requiring a grand jury indictment for "capital crime" and a due process of law for deprivation of "life" by the government.[21] The Fourteenth Amendment adopted in 1868 also requires a due process of law for deprivation of life by any states.[22]

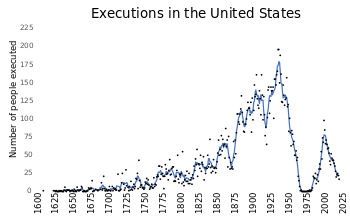

The Espy file,[23] compiled by M. Watt Espy and John Ortiz Smykla, lists 15,269 people executed in the United States and its predecessor colonies between 1608 and 1991. From 1930 to 2002, there were 4,661 executions in the United States; about two-thirds of them in the first 20 years.[24] Additionally, the United States Army executed 135 soldiers between 1916 and 1961 (the most recent).[25][26][27]

Early abolition movement

هذا section يحتاج المزيد من الأسانيد للتحقق. (October 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Three states abolished the death penalty for murder during the 19th century: Michigan (which has never executed a prisoner and is the first government in the English-speaking world to abolish capital punishment)[28] in 1847, Wisconsin in 1853, and Maine in 1887. Rhode Island is also a state with a long abolitionist background, having repealed the death penalty in 1852, though it was available for murder committed by a prisoner between 1872 and 1984.

Other states which abolished the death penalty for murder before Gregg v. Georgia include Minnesota in 1911, Vermont in 1964, Iowa and West Virginia in 1965, and North Dakota in 1973. Hawaii abolished the death penalty in 1948 and Alaska in 1957, both before their statehood. Puerto Rico repealed it in 1929 and the District of Columbia in 1981. Arizona and Oregon abolished the death penalty by popular vote in 1916 and 1964 respectively, but both reinstated it, again by popular vote, some years later; Arizona reinstated the death penalty in 1918 and Oregon in 1978. In Oregon, the measure reinstating the death penalty was overturned by the Oregon Supreme Court in 1981, but Oregon voters again reinstated the death penalty in 1984.[29] Puerto Rico and Michigan are the only two U.S. jurisdictions to have explicitly prohibited capital punishment in their constitutions: in 1952 and 1964, respectively.[30]

Constitutional law developments

Capital punishment was used by 6 of 50 states in 2022. They were Alabama, Arizona, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma and Texas.[31] Government executions, as reported by Amnesty International, took place in 20 of the world's 195 countries. The Federal government of the United States, which had not executed a prisoner since 2003, did so in 2020, in an effort led by President Donald Trump and Attorney General William Barr.

Executions for various crimes, especially murder and rape, occurred from the creation of the United States up to the beginning of the 1960s. Until then, "save for a few mavericks, no one gave any credence to the possibility of ending the death penalty by judicial interpretation of constitutional law", according to abolitionist Hugo Bedau.[32]

The possibility of challenging the constitutionality of the death penalty became progressively more realistic after the Supreme Court of the United States decided on Trop v. Dulles in 1958. The Supreme Court declared explicitly, for the first time, that the Eighth Amendment's cruel and unusual punishment clause must draw its meaning from the "evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society", rather than from its original meaning. Also in the 1932 case Powell v. Alabama, the court made the first step of what would later be called "death is different" jurisprudence, when it held that any indigent defendant was entitled to a court-appointed attorney in capital cases – a right that was only later extended to non-capital defendants in 1963, with Gideon v. Wainwright.

Capital punishment suspended (1972)

In Furman v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court considered a group of consolidated cases. The lead case involved an individual convicted under Georgia's death penalty statute, which featured a "unitary trial" procedure in which the jury was asked to return a verdict of guilt or innocence and, simultaneously, determine whether the defendant would be punished by death or life imprisonment. The last pre-Furman execution was that of Luis Monge on June 2, 1967.

In a 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the impositions of the death penalty in each of the consolidated cases as unconstitutional in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution. The Supreme Court has never ruled the death penalty to be per se unconstitutional. The five justices in the majority did not produce a common opinion or rationale for their decision, however, and agreed only on a short statement announcing the result. The narrowest opinions, those of Byron White and Potter Stewart, expressed generalized concerns about the inconsistent application of the death penalty across a variety of cases, but did not exclude the possibility of a constitutional death penalty law. Stewart and William O. Douglas worried explicitly about racial discrimination in enforcement of the death penalty. Thurgood Marshall and William J. Brennan Jr. expressed the opinion that the death penalty was proscribed absolutely by the Eighth Amendment as cruel and unusual punishment. This decision was reached by the suspicion that many states, particularly in the South, were using capital punishment as a form of legal lynching of African-American males, inasmuch as almost all executions for non-homicidal rape in the Southern states involved a black perpetrator, and this suspicion was fueled by cases such as the Martinsville Seven, when seven African-American men were executed by Virginia in 1951 for the gang rape of a white woman.[33]

The Furman decision caused all death sentences pending at the time to be reduced to life imprisonment, and was described by scholars as a "legal bombshell".[6] The next day, columnist Barry Schweid wrote that it was "unlikely" that the death penalty could exist anymore in the United States.[34]

Capital punishment reinstated (1976)

Instead of abandoning capital punishment, 37 states enacted new death penalty statutes that attempted to address the concerns of White and Stewart in Furman. Some states responded by enacting mandatory death penalty statutes which prescribed a sentence of death for anyone convicted of certain forms of murder. White had hinted that such a scheme would meet his constitutional concerns in his Furman opinion. Other states adopted "bifurcated" trial and sentencing procedures, with various procedural limitations on the jury's ability to pronounce a death sentence designed to limit juror discretion.[35]

On July 2, 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Gregg v. Georgia[36] and upheld 7–2 a Georgia procedure in which the trial of capital crimes was bifurcated into guilt-innocence and sentencing phases. At the first proceeding, the jury decides the defendant's guilt; if the defendant is innocent or otherwise not convicted of first-degree murder, the death penalty will not be imposed. At the second hearing, the jury determines whether certain statutory aggravating factors exist, whether any mitigating factors exist, and, in many jurisdictions, weigh the aggravating and mitigating factors in assessing the ultimate penalty – either death or life in prison, either with or without parole. The same day, in Woodson v. North Carolina[37] and Roberts v. Louisiana,[38] the court struck down 5–4 statutes providing a mandatory death sentence.

Executions resumed on January 17, 1977, when Gary Gilmore went before a firing squad in Utah. Although hundreds of individuals were sentenced to death in the United States during the 1970s and early 1980s, only ten people besides Gilmore (who had waived all of his appeal rights) were executed prior to 1984.

Following the decision, the use of capital punishment in the United States soared.[39] This was in contrast to trends in other parts of advanced industrial democracies where the use of capital punishment declined or was prohibited.[39] Members of the Council of Europe comply with the European Convention of Human Rights which prohibits capital punishment. The last execution in the UK took place in 1964,[40] and in 1977 in France.

Supreme Court narrows capital offenses

In 1977, the Supreme Court's Coker v. Georgia decision barred the death penalty for rape of an adult woman. Previously, the death penalty for rape of an adult had been gradually phased out in the United States, and at the time of the decision, Georgia and the Federal government were the only two jurisdictions to still retain the death penalty for this offense.

In the 1980 case Godfrey v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that murder can be punished by death only if it involves a narrow and precise aggravating factor.[41]

The U.S. Supreme Court has placed two major restrictions on the use of the death penalty. First, the case of Atkins v. Virginia, decided on June 20, 2002,[42] held that the execution of intellectually disabled inmates is unconstitutional. Second, in 2005, the court's decision in Roper v. Simmons[43] struck down executions for offenders under the age of 18 at the time of the crime.

In the 2008 case Kennedy v. Louisiana, the court also held 5–4 that the death penalty is unconstitutional when applied to non-homicidal crimes against the person, including child rape. Only two death row inmates (both in Louisiana) were affected by the decision.[44] Nevertheless, the ruling came less than five months before the 2008 presidential election and was criticized by both major party candidates Barack Obama and John McCain.[45]

Repeal movements and legal challenges

In 2004, New York's and Kansas' capital sentencing schemes were struck down by their respective states' highest courts. Kansas successfully appealed the Kansas Supreme Court decision to the United States Supreme Court, which reinstated the statute in Kansas v. Marsh (2006), holding it did not violate the U.S. Constitution. The decision of the New York Court of Appeals was based on the state constitution, making unavailable any appeal. The state lower house has since blocked all attempts to reinstate the death penalty by adopting a valid sentencing scheme.[46] In 2016, Delaware's death penalty statute was also struck down by its state supreme court.[47]

In 2007, New Jersey became the first state to repeal the death penalty by legislative vote since Gregg v. Georgia,[48] followed by New Mexico in 2009,[49][50] Illinois in 2011,[51] Connecticut in 2012,[52][53] and Maryland in 2013.[54] The repeals were not retroactive, but in New Jersey, Illinois and Maryland, governors commuted all death sentences after enacting the new law.[55] In Connecticut, the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that the repeal must be retroactive. In New Mexico, capital punishment for certain offenses is still possible for National Guard members in Title 32 status under the state's Code of Military Justice (NMSA 20–12), and for capital offenses committed prior to the repeal of the state's death penalty statute.[56][57]

Nebraska's legislature also passed a repeal in 2015, but a referendum campaign gathered enough signatures to suspend it. Capital punishment was reinstated by popular vote on November 8, 2016. The same day, California's electorate defeated a proposal to repeal the death penalty, and adopted another initiative to speed up its appeal process.[58]

On October 11, 2018, Washington state became the 20th state to abolish capital punishment when its state Supreme Court deemed the death penalty unconstitutional on the grounds of racial bias.[59] The state later abolished it through legislation passed in 2023.[60]

New Hampshire became the 21st state to abolish capital punishment on May 30, 2019, when its state senate overrode Governor Sununu's veto by a vote of 16–8.[61]

Colorado became the 22nd state to abolish capital punishment when governor Jared Polis signed a repeal bill on March 23, 2020, and commuted all existing death sentences in the state to life without parole.[62]

Virginia became the 23rd state to abolish capital punishment, and the first Southern state to do so when governor Ralph Northam signed a repeal bill on March 24, 2021, and commuted all existing death sentences in the state to life without parole.[63][64]

Since Furman, 11 states have organized popular votes dealing with the death penalty through the initiative and referendum process. All resulted in a vote for reinstating it, rejecting its abolition, expanding its application field, specifying in the state constitution that it is not unconstitutional, or expediting the appeal process in capital cases.[29]

The advocacy group Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty is creating a national network of Republican and Libertarian legislators at the state level to introduce bills aimed at abolishing or limiting the death penalty. The issue is framed along the values of pro-life, limited government, and fiscal responsibility.[65]

States that have abolished the death penalty

A total of 23 states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have abolished the death penalty for all crimes. Below is a table of the states and the date that the state abolished the death penalty.[66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73] Michigan became the first English-speaking territory in the world to abolish capital punishment in 1847. Although treason remained a crime punishable by the death penalty in Michigan despite the 1847 abolition, no one was ever executed under that law, and Michigan's 1962 Constitutional Convention codified that the death penalty was fully abolished.[74] Vermont has abolished the death penalty for all crimes, but has an invalid death penalty statue for treason.[75] When it abolished the death penalty in 2019, New Hampshire explicitly did not commute the death sentence of the sole person remaining on the state's death row.[76][77]

| State/District/Territory | Year | Last execution |

|---|---|---|

| Alaska | 1957 | 1950 |

| Colorado | 2020 | 1997 |

| Connecticut | 2012 | 2005 |

| Delaware | 2016 | 2012 |

| District of Columbia | 1981 | 1957 |

| Hawaii | 1957 | 1947 |

| Illinois | 2011 | 1999 |

| Iowa | 1965 | 1962 |

| Maine | 1887 | 1885 |

| Maryland | 2013 | 2005 |

| Massachusetts | 1984 | 1947 |

| Michigan | 1847 (1963) | 1837 |

| Minnesota | 1911 | 1906 |

| New Hampshire | 2019 | 1939 |

| New Jersey | 2007 | 1963 |

| New Mexico | 2009 | 2001 |

| New York | 2007 | 1963 |

| North Dakota | 1973 | 1905 |

| Rhode Island | 1984 | 1845 |

| Puerto Rico | 1929 | 1927 |

| Vermont | 1972 | 1954 |

| Virginia | 2021 | 2017 |

| Washington | 2018 | 2010 |

| West Virginia | 1965 | 1959 |

| Wisconsin | 1853 | 1851 |

Modern era

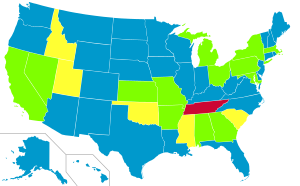

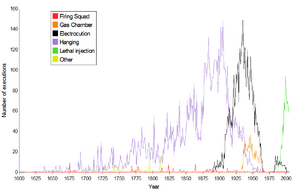

In 1982, Texas carried out the first execution by lethal injection in world history and lethal injection subsequently became the preferred method throughout the country, displacing the electric chair.[78] From 1976 to December 8, 2016, there were 1,533 executions, of which 1,349 were by lethal injection, 163 by electrocution, 11 by gas inhalation, 3 by hanging, and 3 by firing squad.[79] The South had the great majority of these executions, with 1,249; there were 190 in the Midwest, 86 in the West, and only 4 in the Northeast. No state in the Northeast has conducted an execution since Connecticut, now abolitionist, in 2005. The state of Texas alone conducted 571 executions, over 1/3 of the total; the states of Texas, Virginia (now abolitionist), and Oklahoma combined make up over half the total, with 802 executions between them.[80] 17 executions have been conducted by the federal government.[81] Executions increased in frequency until 1999; 98 prisoners were executed that year. Since 1999, the number of executions has greatly decreased, and the 17 executions in 2020 were the fewest since 1991.[8] A 2016 poll conducted by Pew Research, found that support nationwide for the death penalty in the U.S. had fallen below 50% for the first time since the beginning of the post-Gregg era.[82]

The death penalty became an issue during the 1988 presidential election. It came up in the October 13, 1988, debate between the two presidential nominees George H. W. Bush and Michael Dukakis, when Bernard Shaw, the moderator of the debate, asked Dukakis, "Governor, if Kitty Dukakis [his wife] were raped and murdered, would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?" Dukakis replied, "No, I don't, and I think you know that I've opposed the death penalty during all of my life. I don't see any evidence that it's a deterrent, and I think there are better and more effective ways to deal with violent crime." Bush was elected, and many, including Dukakis himself, cite the statement as the beginning of the end of his campaign.[83]

In 1996, Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act to streamline the appeal process in capital cases. The bill was signed into law by President Bill Clinton, who had endorsed capital punishment during his 1992 presidential campaign.[84]

A study found that at least 34 of the 749 executions carried out in the U.S. between 1977 and 2001, or 4.5%, involved "unanticipated problems or delays that caused, at least arguably, unnecessary agony for the prisoner or that reflect gross incompetence of the executioner". The rate of these "botched executions" remained steady over the period.[85] A study published in The Lancet in 2005 found that in 43% of cases of lethal injection, the blood level of hypnotics in the prisoner was insufficient to ensure unconsciousness.[86] Nonetheless, the Supreme Court ruled in 2008 (Baze v. Rees), again in 2015 (Glossip v. Gross), and a third time in 2019 (Bucklew v. Precythe), that lethal injection does not constitute cruel and unusual punishment.[87][88]

On July 25, 2019, Attorney General William Barr ordered the resumption of federal executions after a 16-year hiatus, and set five execution dates for December 2019 and January 2020.[89][90][91][92] After the Supreme Court upheld a stay on these executions,[93] the stay was lifted in June 2020 and four executions were rescheduled for July and August 2020.[94] The federal government executed Daniel Lewis Lee on July 14, 2020. He became the first convict executed by the federal government since 2003.[13] Before Trump's term ended in January 2021, the federal government carried out a total of 13 executions.[95]

Women's history and capital punishment

In 1632, 24 years after the first recorded male execution in the colonies, Jane Champion became the first woman known to have been lawfully executed. She was sentenced to death by hanging after she was convicted of infanticide; around two-thirds of women executed in the 17th and early 18th centuries were convicted of child murder. A married woman, it is not known whether Champion's illicit lover, William Gallopin, also convicted of their child's murder, was also executed, although it appears he was so sentenced.[96][97] For the Puritans, infanticide was the worst form of murder.[98]

Women accounted for just one fifth of all executions between 1632 and 1759, in the colonial United States. Women were more likely to be acquitted, and the relatively low number of executions of women may have been impacted by the scarcity of female laborers. Slavery was not yet widespread in the 17th century mainland and planters relied mostly on Irish indentured servants. To maintain subsistence levels in those days everyone had to do farm work, including women.[96]

The second half of the 17th century saw the executions of 14 women and 6 men who were accused of witchcraft during the witch hunt hysteria and the Salem Witch Trials. While both men and women were executed, 80% of the accusations were towards women, so the list of executions disproportionately affected men by a margin of 6 (actual) to 4 (expected), i.e. 50% more men were executed than expected from the percentage of accused who were men.[99]

Other notable female executions include Mary Surratt, Margie Velma Barfield and Wanda Jean Allen. Mary Surratt was executed by hanging in 1865 after being convicted of co-conspiring to assassinate Abraham Lincoln.[100] Margie Velma Barfield was convicted of murder and when she was executed by lethal injection in 1984, she became the first woman to be executed since the ban on capital punishment was lifted in 1976.[101] Wanda Jean Allen was convicted of murder in 1989 and had a high-profile execution by lethal injection in January 2001. She was the first black woman to be executed in the US since 1954.[102] Allen's appellate lawyers did not deny her guilt, but claimed that prosecutors capitalized on her low IQ, race and homosexuality in their representations of her as a murderer at trial. This approach did not work.[103]

The federal government executes women infrequently. Ethel Rosenberg, convicted of espionage, was executed in the electric chair on June 19, 1953, and Bonnie Brown Heady, convicted of kidnapping and murder, was executed in the gas chamber later that same year on December 18. Since Heady, only one more woman has been executed by the federal government: Lisa Montgomery, convicted of killing a pregnant woman and cutting out and kidnapping her baby, by lethal injection on January 13, 2021. Her execution had been stayed while her lawyers argued that she had mental health issues, but the Supreme Court lifted the stay.[104][105]

Juvenile capital punishment

In 1642, the first ever juvenile, Thomas Graunger, was sentenced to death in Plymouth Colony, Massachusetts, for bestiality. Since then, at least 361 other juveniles have been sentenced to the death penalty.[بحاجة لمصدر] In 1959, Leonard Shockley was executed in Maryland, becoming the last person in the United States who was executed while still a juvenile at the time of their execution. Kent v. United States (1966), turned the tides for juvenile capital punishment sentencing when it limited the waiver discretion juvenile courts had. Before this case, juvenile courts had the freedom to waiver juvenile cases to criminal courts without a hearing, which did not make the waiving process consistent across states. Discussions about abolishing the death penalty started occurring between 1983 and 1986. In 1987, Thompson v. Oklahoma, the Supreme Court threw away William Wayne Thompson's death sentence due to it being cruel and unusual punishment, as he was 15 years old at the time of the crime he committed; the judgment established that "evolving standards of decency" made it inappropriate to apply the death penalty for people under 16 years old at the time of their capital crime,[106] although Thompson held that it was still constitutional to sentence juveniles 16 years or older to the death penalty.

It was not until Roper v. Simmons that the juvenile death penalty was abolished due to the United States Supreme Court finding that the execution of juveniles is in conflict with the Eighth Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment, which deal with cruel and unusual punishment. Prior to completely abolishing the juvenile death penalty in 2005, any juvenile aged 16 years or older could be sentenced to death in some states, the last of whom was Scott Hain, executed at the age of 32 in Oklahoma for the 2003 burning of two people to death during a robbery at age 17.[107] Prior to Roper, there were 71 people on death row in the United States for crimes committed as juveniles.[108] Since 2005, there have been no executions nor discussion of executing juveniles in the United States.

Capital crimes

Aggravated murder

Aggravating factors for seeking capital punishment of murder vary greatly among death penalty states. California has twenty-two.[109] Some aggravating circumstances are nearly universal, such as robbery-murder, murder involving rape of the victim, and murder of an on-duty police officer.[110]

Several states have included child murder to their list of aggravating factors, but the victim's age under which the murder is punishable by death varies. In 2011, Texas raised this age from six to ten.[111]

In some states, the high number of aggravating factors has been criticized on account of giving prosecutors too much discretion in choosing cases where they believe capital punishment is warranted. In California especially, an official commission proposed, in 2008, to reduce these factors to five (multiple murders, torture murder, murder of a police officer, murder committed in jail, and murder related to another felony).[112] Columnist Charles Lane went further, and proposed that murder related to a felony other than rape should no longer be a capital crime when there is only one victim killed.[113]

Aggravating factors in federal court

In order for a person to be eligible for a death sentence when convicted of aggravated first-degree murder, the jury or court (when there is not a jury) must determine at least one of sixteen aggravating factors that existed during the crime's commission. The following is a list of the 16 aggravating factors under federal law.[114]

- Murder while committing another felony.[115]

- Offender was convicted of a separate felony involving a firearm prior to the aggravated murder.

- Being convicted of a separate felony where death or life imprisonment was authorized prior to the aggravated murder.

- Being convicted of any separate violent felony prior to the aggravated murder.

- The offender put the lives of at least 1 or more other persons in danger of death during the commission of the crime.

- Offender committed the crime in an especially cruel, heinous, or depraved manner.

- Offender committed the crime for financial gain.

- Offender committed the crime for monetary gain.

- The murder was premeditated, involved planning in order to be carried out, or the offender showed early signs of committing the crime, such as keeping a journal of the crime's details[116] and posting things on the Internet.[117]

- Offender was previously convicted of at least two drug offenses.

- The victim would not have been able to defend themselves while being attacked.

- Offender was previously convicted of a federal drug offense.

- Offender was involved in a long-term business of selling drugs to minors.

- A high-ranking official was murdered, such as the President of the United States, the leader of another country, or a police officer.

- Offender was previously convicted of sexual assault or child rape.

- During the crime's commission, the offender killed or tried to kill multiple people.[118]

Crimes against the state

The opinion of the court in Kennedy v. Louisiana says that the ruling does not apply to "treason, espionage, terrorism, and drug kingpin activity, which are offenses against the State".[119]

Treason, espionage and large-scale drug trafficking are all capital crimes under federal law. Treason is also punishable by death in six states (Arkansas, California, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina). Large-scale drug trafficking is punishable by death in two states (Florida and Missouri),[120] and aircraft hijacking in two others (Georgia and Mississippi). Vermont has an invalidated pre-Furman statute allowing capital punishment for treason despite abolishing capital punishment in 1965.[121]

Legal process

The legal administration of the death penalty in the United States typically involves five steps: (1) prosecutorial decision to seek the death penalty (2) sentencing, (3) direct review, (4) state collateral review, and (5) federal habeas corpus.

Clemency, through which the Governor or President of the jurisdiction can unilaterally reduce or abrogate a death sentence, is an executive rather than judicial process.[122]

Decision to seek the death penalty

While judges in criminal cases can usually impose a harsher prison sentence than the one demanded by prosecution, the death penalty can be handed down only if the accuser has specifically decided to seek it.

In the decades since Furman, new questions have emerged about whether or not prosecutorial arbitrariness has replaced sentencing arbitrariness. A study by Pepperdine University School of Law published in Temple Law Review, surveyed the decision-making process among prosecutors in various states. The authors found that prosecutors' capital punishment filing decisions are marked by local "idiosyncrasies", and that wide prosecutorial discretion remains because of overly broad criteria. California law, for example, has 22 "special circumstances", making nearly all first-degree murders potential capital cases.[123]

A proposed remedy against prosecutorial arbitrariness is to transfer the prosecution of capital cases to the state attorney general.[124]

In 2017, Florida governor Rick Scott removed all capital cases from local prosecutor Aramis Ayala because she decided to never seek the death penalty no matter the gravity of the crime.[125]

Sentencing

Of the 27 states with the death penalty, 25 require the sentence to be decided by the jury, and 23 require a unanimous decision by the jury.

Two states do not use juries in death penalty cases. In Nebraska the sentence is decided by a three-judge panel, which must unanimously agree on death, and the defendant is sentenced to life imprisonment if one of the judges is opposed.[126] Montana is the only state where the trial judge decides the sentence alone.[127] Two states do not require a unanimous jury decision, including Alabama and Florida. In Alabama, at least 10 jurors must concur, and a retrial happens if the jury deadlocks.[128] In Florida, at least 8 jurors must concur, and the prosecution can pursue a retrial of a mistrial results from a jury deadlock.[129]

In all states in which the jury is involved, only death-qualified prospective jurors can be selected in such a jury, to exclude both people who will always vote for the death sentence and those who are categorically opposed to it. However, the states differ on what happens if the penalty phase results in a hung jury:[130][131]

- In four states (Arizona, California, Kentucky and Nevada), a retrial of the penalty phase will be conducted before a different jury (the common-law rule for mistrial).[132]

- In two states (Indiana and Missouri), the judge will decide the sentence.

- In the remaining states, a hung jury results in a life sentence, even if only one juror opposed death. Federal law also provides that outcome.

The first outcome is referred as the "true unanimity" rule, while the third has been criticized as the "single-juror veto" rule.[133]

Direct review

If a defendant is sentenced to death at the trial level, the case then goes into a direct review.[134] The direct review process is a typical legal appeal. An appellate court examines the record of evidence presented in the trial court and the law that the lower court applied and decides whether the decision was legally sound or not.[135] Direct review of a capital sentencing hearing will result in one of three outcomes. If the appellate court finds that no significant legal errors occurred in the capital sentencing hearing, the appellate court will affirm the judgment, or let the sentence stand.[134] If the appellate court finds that significant legal errors did occur, then it will reverse the judgment, or nullify the sentence and order a new capital sentencing hearing.[136] If the appellate court finds that no reasonable juror could find the defendant eligible for the death penalty, then it will order the defendant acquitted, or not guilty, of the crime for which he/she was given the death penalty, and order him sentenced to the next most severe punishment for which the offense is eligible.[136] About 60 percent of capital punishment decisions were upheld during direct review.[137]

State collateral review

At times when a death sentence is affirmed on direct review, supplemental methods to oppose the judgment, though less familiar than a typical appeal, do remain. These supplemental remedies are considered collateral review, that is, an avenue for upsetting judgments that have become otherwise final.[138] Where the prisoner received his death sentence in a state-level trial, as is usually the case, the first step in collateral review is state collateral review, which is often called state habeas corpus. (If the case is a federal death penalty case, it proceeds immediately from direct review to federal habeas corpus.) Although all states have some type of collateral review, the process varies widely from state to state.[139] Generally, the purpose of these collateral proceedings is to permit the prisoner to challenge his sentence on grounds that could not have been raised reasonably at trial or on direct review.[140] Most often, these are claims, such as ineffective assistance of counsel, which requires the court to consider new evidence outside the original trial record, something courts may not do in an ordinary appeal. State collateral review, though an important step in that it helps define the scope of subsequent review through federal habeas corpus, is rarely successful in and of itself. Only around 6 percent of death sentences are overturned on state collateral review.[141]

In Virginia, state habeas corpus for condemned men are heard by the state supreme court under exclusive original jurisdiction since 1995, immediately after direct review by the same court.[142] This avoids any proceeding before the lower courts, and is in part why Virginia has the shortest time on average between death sentence and execution (less than eight years) and has executed 113 offenders since 1976 with only five remaining on death row اعتبارا من يونيو 2017[تحديث].[143][144]

To reduce litigation delays, other states require convicts to file their state collateral appeal before the completion of their direct appeal,[145] or provide adjudication of direct and collateral attacks together in a "unitary review".[146]

Federal habeas corpus

After a death sentence is affirmed in state collateral review, the prisoner may file for federal habeas corpus, which is a unique type of lawsuit that can be brought in federal courts. Federal habeas corpus is a type of collateral review, and it is the only way that state prisoners may attack a death sentence in federal court (other than petitions for certiorari to the United States Supreme Court after both direct review and state collateral review). The scope of federal habeas corpus is governed by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), which restricted significantly its previous scope. The purpose of federal habeas corpus is to ensure that state courts, through the process of direct review and state collateral review, have done a reasonable job in protecting the prisoner's federal constitutional rights. Prisoners may also use federal habeas corpus suits to bring forth new evidence that they are innocent of the crime, though to be a valid defense at this late stage in the process, evidence of innocence must be truly compelling.[147] According to Eric M. Freedman, 21 percent of death penalty cases are reversed through federal habeas corpus.[141]

James Liebman, a professor of law at Columbia Law School, stated in 1996 that his study found that when habeas corpus petitions in death penalty cases were traced from conviction to completion of the case, there was "a 40 percent success rate in all capital cases from 1978 to 1995".[148] Similarly, a study by Ronald Tabak in a law review article puts the success rate in habeas corpus cases involving death row inmates even higher, finding that between "1976 and 1991, approximately 47 percent of the habeas petitions filed by death row inmates were granted".[149] The different numbers are largely definitional, rather than substantive: Freedam's statistics looks at the percentage of all death penalty cases reversed, while the others look only at cases not reversed prior to habeas corpus review.

A similar process is available for prisoners sentenced to death by the judgment of a federal court.[150]

The AEDPA also provides an expeditious habeas procedure in capital cases for states meeting several requirements set forth in it concerning counsel appointment for death row inmates.[151] Under this program, federal habeas corpus for condemned prisoners would be decided in about three years from affirmance of the sentence on state collateral review. In 2006, Congress conferred the determination of whether a state fulfilled the requirements to the U.S. attorney general, with a possible appeal of the state to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. اعتبارا من مارس 2016[تحديث], the Department of Justice has still not granted any certifications.[152]

Section 1983

If the federal court refuses to issue a writ of habeas corpus, the death sentence ordinarily becomes final for all purposes. In recent times, however, prisoners have postponed execution through another avenue of federal litigation; the Civil Rights Act of 1871 – codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1983 – allows complainants to bring lawsuits against state actors to protect their federal constitutional and statutory rights.

While direct appeals are normally limited to just one and automatically stay the execution of the death sentence, Section 1983 lawsuits are unlimited, but the petitioner will be granted a stay of execution only if the court believes he has a likelihood of success on the merits.[153]

Traditionally, Section 1983 was of limited use for a state prisoner under sentence of death because the Supreme Court has held that habeas corpus, not Section 1983, is the only vehicle by which a state prisoner can challenge his judgment of death.[154] In the 2006 Hill v. McDonough case, however, the United States Supreme Court approved the use of Section 1983 as a vehicle for challenging a state's method of execution as cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment. The theory is that a prisoner bringing such a challenge is not attacking directly his judgment of death, but rather the means by which that the judgment will be carried out. Therefore, the Supreme Court held in the Hill case that a prisoner can use Section 1983 rather than habeas corpus to bring the lawsuit. Yet, as Clarence Hill's own case shows, lower federal courts have often refused to hear suits challenging methods of execution on the ground that the prisoner brought the claim too late and only for the purposes of delay. Further, the Court's decision in Baze v. Rees, upholding a lethal injection method used by many states, has narrowed the opportunity for relief through Section 1983.

Execution warrant

While the execution warrant is issued by the governor in several states, in the vast majority it is a judicial order, issued by a judge or by the state supreme court at the request of the prosecution.

The warrant usually sets an execution day. Some states instead provide a longer period, such as a week-long or 10-day window to carry out the execution. This is designated to avoid issuing a new warrant in case of a last-minute stay of execution that would be vacated only few days or few hours later.[155]

Distribution of sentences

In recent years there has been an average of one death sentence for every 200 murder convictions in the United States.

Alabama has the highest per capita rate of death sentences. This is because Alabama was one of the few states that allowed judges to override a jury recommendation in favor of life imprisonment, a possibility it removed in March 2017.[156][157]

According to the Death Penalty Information Center, the top three factors determining whether a convict gets a death sentence in a murder case are not aggravating factors, but instead the location the crime occurred (and thus whether it is in the jurisdiction of a prosecutor aggressively using the death penalty), the quality of legal defense, and the race of the victim (murder of white victims being punished more harshly).[158]

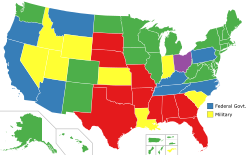

Among states

The distribution of death sentences among states is loosely proportional to their populations and murder rates. California, which is the most populous state, also has the largest death row, with over 700 inmates. Wyoming, which is the least populous state, has only one condemned man.

But executions are more frequent (and happen more quickly after sentencing) in conservative states. Texas, which is the second most populous state in the Union, carried out over 500 executions during the post-Furman era, more than a third of the national total. California has carried out only 13 executions during the same period, and has carried out none since 2006.[159][160][161]

Among races

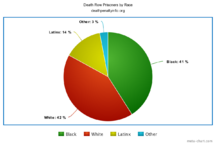

Certain races within the United States are disproportionately incarcerated at higher rates than others. African Americans, who make up only 13.6% of the total population are disproportionately incarcerated in the prison system compared to white Americans.[162]

Statistics

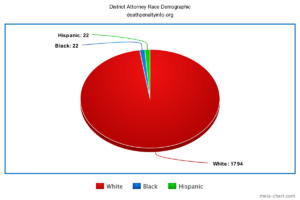

African Americans make up 41% of death row inmates.[162][163] African Americans have made up 34% of those actually executed since 1976.[162][165] Twenty-one white offenders have been executed for the murder of a black person since 1976, compared to the 302 black offenders that have been executed for the murder of a white person during that same period.[163] Most individuals involved in determining the verdict in death penalty cases are white. As of 1998, Chief District Attorneys in counties using the death penalty are 98% white and only 1% are African-American.[164] A supporting fact discovered through examinations of racial disparities over the past twenty years concerning race and the death penalty found that in 96% of these reviews, there was "a pattern of either race-of-victim or race-of-defendant discrimination or both."[164] 80% of all capital cases involve white victims, despite white people only making up approximately 50% of murder victims.[166]

With regard to innocent convicts, 54 percent of people wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death in the United States are black; 64 percent are non-white in general.[167]

63.8% of white death row inmates, 72.8% of black death row inmates, 65.4% of Latino death row inmates, and 63.8% of Native American death row inmates – or approximately 67% of death row inmates overall – have a prior felony conviction.[168] Approximately 13.5% of death row inmates are of Hispanic or Latino descent. In 2019, individuals identified as Hispanic and Latino Americans accounted for 5.5% of homicides.[169] The death penalty exhortation rate for Hispanic and Latino Americans is 8.6%.[167] Approximately 1.81% of death row inmates are of Asian descent.[170]

Organizations against the death penalty for racial equity

ACLU’s Capital Punishment Project

The ACLU's Capital Punishment Project (CPP) is an anti-death penalty project that works toward the repeal of the death penalty in the U.S. through advocacy and education.[171] The project highlights the racial discriminatory aspects regarding capital punishment and promotes both abolition and systemic reform of the death penalty through direct representation, strategic litigation, and systemic reform.[172]

Equal Justice USA

Equal Justice USA is a national organization dedicated to healing, racial equity, and community safety in relation to criminal justice and violence.[173] Their efforts spread wide and involve fundraising and hosting conventions to support communities of color. The organization is aimed towards people of color who have been disproportionately impacted by the death penalty.[174] Some of their efforts include advocacy to end the death penalty, which they have helped to abolish in nine states.[174]

Black Americans and capital punishment

The geographic distribution of capital punishment in the United States has a strong correlation with the history of slavery and lynchings.[5] States where slavery was legal before the Civil War also saw high numbers of lynchings after the Civil War and into the 20th century. These states include Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee.[175] These states also introduced a criminal justice system with Black Codes, designed to control Black people after slavery was abolished in 1865 following the Emancipation Proclamation, and then officially with the ratification of the 13th Amendment.[176] These states also have the highest rates of capital punishment sentences and executions today.[5]

Racial relationship between lynchings and capital punishment

Once slaveowners lost full ownership of formerly enslaved African-Americans in 1865, lynchings were increasingly used, both legally under the security of Black Codes and illegally, to maintain white dominance and prevent African-Americans from challenging their subordinate place in society.[175] Because of Black Codes, many African-Americans were sent to jail to participate in slave-like work in a system known as Convict leasing. Others faced capital punishment for alleged crimes, often in the form of lynching.[176] Lynchings were able to be carried out because many positions within southern law enforcement, including state officials, and judges were held by former Confederate soldiers.[177] Despite the passing of the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which weakened the strength of Black Codes and supported the 14th Amendment, the rate of lynching of African-Americans saw an increase,[178] due the formation of the white-supremacist terrorist group, the Ku Klux Klan (K.K.K.), in 1865 by former Confederates during Reconstruction. They carried out many lynchings and terrorist attacks against Black people.[177] After the end of the Reconstruction in 1877, when federal troops were removed from southern states in which they assisted in upholding the 14th Amendment's promises of equal protection, Jim Crow laws began to gain traction which enforced segregation and the oppression of African-Americans. Segregation was legal under the 1896 Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it unconstitutional.[178]

During and following the Civil Rights era, laws were introduced to prevent illegal lynchings by the general public. According to David Rigby and Charles Seguin, the popularity of capital punishment increased as a way for White people to control Black people and instill fear.[5] They argue that the disproportionate number of Black Americans sentenced to death during the 20th century, often wrongfully convicted, shows that capital punishment was used as a way for White people to control Black people in a similar manner to lynching. In 1972, the Supreme Court ruled in Furman v. Georgia that capital punishment was unconstitutional. Rigby and Seguin argue that this led to an increase in the illegal lynchings of African-Americans.[5] In 1976 the Supreme Court decision in Gregg v. Georgia [179] upheld the death penalty and overturned Furman v. Georgia. Rigby and Seguin argue that this decision was based on a fear that lynchings by the general public would increase if the death penalty did not remain in place.[5]

Although more than 6,500 lynchings occurred between 1865 and 1950 according to the Equal Justice Initiative, lynching did not become a federal crime until 2022 under the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, which was signed into law by President Joe Biden, over a hundred years after Antilynching legislation was first proposed.[180]

21st century legal scholars, Civil Rights lawyers, and advocates, like Michelle Alexander, often refer to both past and modern police officers and officials of the United States' criminal justice system's as legalized, modern lynch mobs because they have the ability to sentence one to life in prison or with the death penalty under the law but with the jurisdiction of potentially incorporating their personal, racial biases.[181] The ability for a Black person to be convicted to death, with the potential that racial bias was used in their sentencing, was upheld during the McCleskey v. Kemp court case in Georgia.[182][181] Groups like the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund (LDF) have continuously worked and continue to work on abolishing capital punishment based on its historically racist associations with enslavement and lynching, and also its disproportionate impact on racial minority communities.[183]

Racial breakdown of sentences by state

Capital punishment is still active in 27 states, which including the following: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Wyoming.[184] Of these, Oklahoma, Texas, Delaware, Missouri, and Alabama make up the top five states with the highest rate of executions per capita.[185] However, Texas, Oklahoma, Virginia, Florida, and Missouri are the top five states with the highest number of executions–Texas alone has imposed 570 executions since 1976.[185]

The racial makeup of the people sentenced to death reveals a disproportionate representation of Black people. Consider the following states with the highest execution rates per capita (defined as executions per 100,000 residents):

Top five states with the highest rates of execution per capita

| State | Rate of execution per capita (per 100,000 residents)[185] | Number of executions since 1976[185] | Total population[186] | Percent of state population that is Black[186] | Percent of those currently on death row who are Black[162] | Percent of innocent people sentenced to death that are Black[167] |

| Oklahoma | 2.83 | 112 | 3,986,639 | 7.8 | 40.5 | 54.6 |

| Texas | 1.97 | 570 | 29,527,941 | 13.2 | 45.2 | 18.8 |

| Delaware (now abolished) | 1.64 | 16 | 1,003,384 | 23.6 | N/A | 100[ت] |

| Missouri | 1.47 | 90 | 6,168,187 | 11.8 | 30 | 75 |

| Alabama | 1.37 | 67 | 5,039,877 | 26.8 | 48.2 | 42.6 |

Texas

Capital punishment in Texas: Texas is the state with the highest number of cumulative executions since 1976. Black people make up about 45% of the current death row population in Texas,[187] though only make up about 13% of the state's general population.[188]

Oklahoma

Capital punishment in Oklahoma: Oklahoma is the state with the second highest number of cumulative executions since 1976. Black people make up 46% of death sentences in Oklahoma County, though only make up 16% of the county's total population.[189]

It is also the only state that has four methods of execution, while most others only have one or two methods. These methods of execution include: lethal injection, nitrogen hypoxia, electrocution, and firing squad.

Alabama

Capital punishment in Alabama: Alabama's death penalty sentences persist as it declines among many other states in the U.S. The state continues to have one of the nation's highest rates of death sentences per capita.[190] As of April 1, 2022, there are currently 80 Black people and 84 white people on death row.[162] Though the Black and white populations are both about half of the total death row population in Alabama, Black people are represented at a disproportionately high number considering they make up only 27% of Alabama's general population.[191]

Virginia

Capital punishment in Virginia: The death penalty in Virginia came to an end on March 24, 2021, when the state became the first Southern state to abolish the death penalty. Prior to abolition, Virginia had some of the most executions out of any state since 1976, as well as the most executions overall in the pre-Furman v. Georgia era.[192]

Exonerations

Exonerations, in relation to the death penalty, are defined as the absolving of someone from their previous verdict of guilty and sentencing of death. Since January 1, 1973, 103 out of the 190 total exonerations in the U.S. have been African Americans.[167] African Americans account for about 54% of all exonerations.

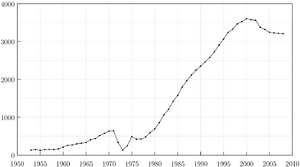

During the middle of the 20th century, a period of mass incarceration occurred in the United States.[193] The United States became the country with the highest incarceration rate which caused the prison population to become heavily Black by the 1990s whereas it was mainly only white in previous years.[193] White people accounted for 51% of the prison population while Black people accounted for 47% of the entire prison population during the 1990s.[194] Even though Black people made up of around half the jail inhabitants, they only were 12.1% of the United States population and white citizens made up 80.3% of the total population during that time.[195] The prison population had increased from 196,441 people in 1970 to 1.6 million by 2008.[193] This discrepancy of races in the prison population related to the overall demographics of the United States has to do with the inconsistency of police arrests on citizens. Moving into 2015, Black people still made up only 12.1% of the total population but made up 18% of people who were stopped by police on the road.[196] This led to the increase of disproportionate demographics in local jails and prison systems. By 2018, 592 Black people were in local jails per every 100,000 people and 2,271 Black men were incarcerated in federal prisons per 100,000 people.[196] On the other hand, white people were incarcerated at a rate of 187 per 100,000 people in local jails and white men, at the federal level, were incarcerated at a rate of 392 per 100,000 people.[196] This dramatic increase in Black arrests caused America's prison population to boom, which was all due to this long lasting period of mass incarceration.

Mass incarceration had been increasing and there are many factors sustaining its rise. From over-policing to disproportionately long prison sentences, Black people have been targeted in mass incarceration and as a result, more susceptible to capital punishment.[197]

Cases

With the United States' operation based on the U.S. Constitution, federalism allows the state government to share powers with the federal government.[198] Under the various capacities, different court cases are heard in the national and state court systems. A defendant can be inflicted with the death penalty if they are found condemned of capital offenses,[199] like first-degree murder, murder with special circumstances, treason, or genocide.[199][200] Because capital offenses are criminal cases, the state court systems are responsible to hear the majority of them. The Supreme Court and state courts' discretion in keeping the death penalty option are separate for the most part, if not appealed to the Supreme Court. According to the Legal Information Institute, “ it is not necessary that the actual punishment imposed was the death penalty, but rather a capital office is classified as such if the permissible punishment prescribed by the legislature for the offense is the death penalty.” [200] After Roper v. Simmons in 2005, the federal court deemed if the defendant was under 18 years old at the time of the crime, they can not be sentenced to death because it violates the 8th Amendment.[201]

George Stinney Jr.

In 1944, 14-year-old African-American George Stinney Jr. was convicted of murdering two white girls. He was the youngest person in the United States to be sentenced to death.[202] Stinney was executed by electrocution within 80 days of the murders. In 2014, Stinney's convictions were vacated and he was exonerated on the grounds that his 6th amendment rights had been violated. It was found Stinney's interrogation had included coercion, and an absence of counsel and of parental guidance.[202] Police said that Stinney had confessed, but no signed confession was ever produced.[203] The Judge who overturned the conviction wrote that: “Stinney’s appointed counsel made no independent investigation, did not request a change of venue or additional time to prepare the case, he asked little or no questions on cross-examination of the State’s witnesses and presented few or no witnesses on behalf of his client based on the length of trial. He failed to file an appeal or a stay of execution.” Stinney's sister said in a 2009 affidavit that she was with Stinney on the day of the murders, but she was never called to testify during the trial.[203]

Exonerated Five

The systemic issue of biased investigation conduct is also seen in the Exonerated Five case. The Exonerated Five is made up of one Latino boy, Raymond Santana, and four black youths, Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, and Korey Wise.[204] They are formerly known as the Central Park Five and the Jogger Case. The boys received mixed convictions for assault, robbery, riot, rape, sexual abuse, and attempted murder of a white woman in 1990.[204]

The boys faced intense, un-recorded interrogations for at least seven hours in the absence of legal counsel, with video confessions following, beside Salaam.[204] Wise additionally had no parent present during questioning and confessing.[204] The five youths later pleaded not guilty and recanted their statements because they were produced under intimidation.[204] Despite no DNA evidence linking any of the boys to the crime scene, they were sentenced to 5 to 15 years.[204] After 12 years, the sole perpetrator, Matias Reyes, confessed to the crime while providing a DNA match to the only DNA selection found at the scene.[205] Their false confessions were recognized for inconsistencies and their convictions were vacated in December 2002.[206] They later sued the state and the city for reparations and received approximately $44 million in a settlement.[207]

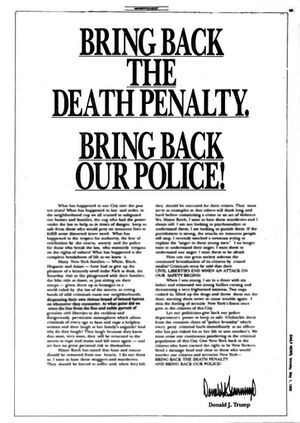

During the 1990 trial, former president Donald Trump (a real-estate character at the time) bought full-page ads voicing his reaction to the Central Park case.[204] In the ad, Donald Trump says the following:

“I want to hate these muggers and murderers. They should be forced to suffer and, when they kill, they should be executed for their crimes. They must serve as examples so that others will think long and hard before committing a crime or an act of violence.”[209][208]

The youths ranged from the ages of 14–16 years when the ad was released. In an archival interview with Larry King, Trump feels his belief is a common feeling because he received 15,000 letters of praise following the ad.[210] In retrospect, Salaam reflects in an 2021 interview with PBS MetroFocus, saying:

“I look at what Donald Trump as being the nails that sealed us in the coffin. And then what happened after that, they published our names, our addresses, and phone numbers in the New York City newspapers. When you think about Donald Trump’s ad, it was a whisper into society to have someone come to our homes to drag us from our beds, and to do to us what they had done to Emmett Till.” [211]

Because the youths were minors, their identities were supposed to remain confidential. Salaam shares that his family received an insurgence of death threats following Trump's advertisement, culminating in a climate of aggressive hate. A Central Park Five representative comments that Trump's ad influenced public opinion, possibly further tainting the impartiality of potential jurors "who [already], had a natural affinity for the victim."[208]

As of 2019, Donald Trump has refused to apologize and retract his statements despite the exoneration of the men.[212]

Lena Baker

Lena Baker was a Black woman who was wrongfully convicted of the murder of her abuser in 1945.[213] In Georgia, Baker served as a maid for a handicapped white man; she faced regular sexual and physical abuse from him.[213] Despite the town terrorizing Baker to leave the relationship, her abuser would equally threaten her with violence if she ever left.[213][214] Weeks before his death, he started holding Baker prisoner in his gristmill for numerous days.[213] Baker was able to escape the mill, but when she came back, her abuser threatened her with an iron bar.[213] After a struggle, Baker took ahold of his pistol and shot the man in self-defense.[214]

The all-white, all-male jury did not empathize with Baker's case of self-defense as a survivor of her slave-like conditions, including sexual and physical abuse.[215] In less than a day, the jury found Baker guilty of capital murder, which happened to result in a mandatory death sentence in Georgia at the time.[215] After failed appeals, reviews, and the abandonment of her legal representation, Lena Baker was executed by electrocution in 1945.[215] About 60 years following Baker's death, her family, with the help of the Prison and Jail Project, requested a posthumous pardon.[216] Their efforts succeeded in 2005 when Baker was granted a full and unconditional pardon from the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles because there was a lack of evidence to demonstrate Baker's intent to kill.[216] If the justice system had been careful with the evidence, they would have noted Baker's conviction did not qualify as capital murder and should have resulted in a sentence other than the death penalty.

Between sexes

As of May 20, 2021, the Death Penalty Information Center reports that there are 51 women on death row. 17 women have been executed since 1976,[217] compared to 1,516 men during the same time period.[218]

Since 1608, 15,391 lawful executions are confirmed to have been carried out in jurisdictions of, or now of, the United States, of these, 575, or 3.6%, were women. Women account for 1⁄50 death sentences, 1⁄67 people on death row, and 1⁄100 people whose executions are actually carried out. While always comparatively rare, women are significantly less likely to be executed in the modern era than in the past. Of the 16 women executed on the state level, most took place in either Texas (6), Oklahoma (3) or Florida (2) and were demographically, 25% (4) African-American and 75% (12) being White of any ethnicity. Historically, the states that have executed the most women are California, Texas and Florida, though unlike Texas and Florida, California has not executed a woman in the post-Furman era. The racial breakdown of women sentenced to death is 61% white, 21% black, 13% Latina, 3% Asian, and 2% American Indian.[217]

Methods

All 26 states with the death penalty for murder provide lethal injection as the primary method of execution. As of 2021, South Carolina is the only autonomous region in the United States of America to authorize its 1912 Electric Chair as the primary method of execution, citing inability to procure the drugs necessary for lethal injection. Vermont's remaining death penalty statute for treason provides electrocution as the method of execution.[75][المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك]

Some states allow secondary methods to be used at the request of the prisoner, if the medication used in lethal injection is unavailable, or due to court challenges to lethal injection's constitutionality.[219][220]

Several states continue to use the three-drug protocol: firstly an anesthetic, secondly pancuronium bromide, a paralytic, and finally potassium chloride to stop the heart.[221] Eight states have used a single-drug protocol, instead using a single anesthetic.[221]

While some state statutes specify the drugs required in executions, a majority do not.[221]

Pressures from anti-death penalty activists have led to supply-chain disruptions of the chemicals used in lethal injections. Hospira, the only U.S. manufacturer of sodium thiopental, stopped making the drug in 2011,[222] citing “[Hospira] would have to prove that it wouldn’t be used in capital punishment.” [223] In 2016, it was reported that more than 20 U.S. and European drug manufacturers including Pfizer (the owner of Hospira) had taken steps to prevent their drugs from being used for lethal injections.[222][224]

Since then, some states have used other anesthetics, such as pentobarbital, etomidate,[225] or fast-acting benzodiazepines or sedatives like midazolam.[226] Many states have since bought lethal injection drugs from foreign suppliers, and most states have made it a criminal offense to reveal the identities of drug suppliers or execution team members.[222][227] In November 2015, California adopted regulations allowing the state to use its own public compounding pharmacies to make the chemicals.[228]

In 2009, following the botched execution of Romell Broom, Ohio began using a one drug protocol of thiopental sodium intravenously for lethal injections, or an intramuscular injection of midazolam and hydromorphone if an IV site could not be established.[229][230] In 2014, this combination was used in the botched execution of Dennis McGuire, which was widely criticized as a “failed experiment”[231] and led to an unofficial moratorium of executions in the state of Ohio.[232]

Lethal injection was held to be a constitutional method of execution by the U.S. Supreme Court in three cases: Baze v. Rees (2008), Glossip v. Gross (2015), and Bucklew v. Precythe (2019).[233][234]

Offender-selected methods

In the following states, death row inmates with an execution warrant may always choose to be executed by:[220]

- Lethal injection in all states as primary method, in South Carolina as secondary method or unless the drugs to use it are unavailable

- Nitrogen hypoxia in Alabama

- Electrocution in Alabama, Florida, and South Carolina (primary method)

- Gas chamber in California and Missouri

In four states an alternate method (firing squad in Utah, gas chamber in Arizona, and electrocution in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Tennessee) is offered only to inmates sentenced to death for crimes committed prior to a specified date (usually when the state switched from the earlier method to lethal injection). The alternate method will be used for all inmates if lethal injection is declared unconstitutional.

In five states, an alternate method is used only if lethal injection would be declared unconstitutional (electrocution in Arkansas; nitrogen hypoxia, electrocution, or firing squad in Mississippi and Oklahoma; firing squad in Utah; gas chamber in Wyoming).

In Alabama, Oklahoma, and Tennessee, "any constitutional method" is possible if all the other methods are declared unconstitutional. In 2024 Alabama used nitrogen gas to execute a prisoner for the first time in the country.[235]

In the state that abolished death penalty or where its statute was declared unconstitutional, people sentenced to death for a crime before the date of the abolition may retroactively be subjected to death penalty. Those states' methods are:

- lethal injection in Colorado

- lethal injection in Delaware unless the offense was committed before 1986, in which case the inmate could choose between lethal injection and hanging

- lethal injection in New Hampshire, unless this method is "impractical", in which case hanging would be the method

- lethal injection or electrocution in Virginia

- lethal injection or hanging in Washington

When an offender chooses to be executed by a means different from the state's default method, which is always lethal injection, he/she loses the right to challenge its constitutionality in court. See Stewart v. LaGrand, 526 U.S. 115 (1999).

The most recent executions by methods other than injection are as follows (all chosen by the inmate):

| Method | Date | State | Inmate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen hypoxia | January 25, 2024 | Alabama | Kenneth Eugene Smith |

| Electrocution | February 20, 2020 | Tennessee | Nicholas Todd Sutton |

| Firing squad | June 18, 2010 | Utah | Ronnie Lee Gardner |

| Gas chamber | March 3, 1999 | Arizona | Walter Bernhard LaGrand |

| Hanging | January 25, 1996 | Delaware | Billy Bailey |

Backup methods

Depending on the state, the following alternative methods are statutorily provided in case lethal injection is either found unconstitutional by a court or unavailable for practical reasons:[219][220][236]

- Nitrogen hypoxia in Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and Oklahoma

- Electrocution in Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky,[237] Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Tennessee.

- Gas chamber in California, Missouri and Wyoming.

- Firing squad in Idaho, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Utah.

- Hanging in New Hampshire (where repeal of the death penalty in 2019 is not retroactive).

Several states including Oklahoma, Tennessee and Utah, have added back-up methods recently (or have expanded their application fields) in reaction to the shortage of lethal injection drugs.[220][238]

Oklahoma and Mississippi are the only states allowing more than two methods of execution in their statutes, providing lethal injection, nitrogen hypoxia, electrocution and firing squad to be used in that order if all earlier methods are unavailable. The nitrogen option was added by the Oklahoma Legislature in 2015 and has never been used in a judicial execution.[239] After struggling for years to design a nitrogen execution protocol and to obtain a proper device for it, Oklahoma announced in February 2020 it abandoned the project after finding a new reliable source of lethal injection drugs.[240]

Some states such as Florida have a larger provision dealing with execution methods unavailability, requiring their state departments of corrections to use "any constitutional method" if both lethal injection and electrocution are found unconstitutional. This was designed to make unnecessary any further legislative intervention in that event, but the provision applies only to legal (not practical) infeasibility.[241][242]

In March 2018, Alabama became the third state (after Oklahoma and Mississippi), to authorize the use of nitrogen asphyxiation as a method of execution.[243] On March 5, 2024, Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry signed a law allowing executions to be carried out via nitrogen gas and electrocution.[244]

In January 2024, the first execution by nitrogen asphyxiation was completed in William C. Holman Correctional Facility in Alabama.[245]

Federal executions

The method of execution of federal prisoners for offenses under the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 is that of the state in which the conviction took place. If the state has no death penalty, the judge must choose a state with the death penalty for carrying out the execution.

The federal government has a facility (at U.S. Penitentiary Terre Haute) and regulations only for executions by lethal injection, but the United States Code allows U.S. Marshals to use state facilities and employees for federal executions.[246][247]

Execution attendance

The last public execution in the U.S. was that of Rainey Bethea in Owensboro, Kentucky, on August 14, 1936.[248]

It was the last execution in the nation at which the general public was permitted to attend without any legally imposed restrictions. "Public execution" is a legal phrase, defined by the laws of various states, and carried out pursuant to a court order. Similar to "public record" or "public meeting", it means that anyone who wants to attend the execution may do so.

Around 1890, a political movement developed in the United States to mandate private executions. Several states enacted laws which required executions to be conducted within a "wall" or "enclosure", or to "exclude public view". Most state laws currently use such explicit wording to prohibit public executions, while others do so only implicitly by enumerating the only authorized witnesses.[249]

All states allow news reporters to be execution witnesses for information of the general public, except Wyoming which allows only witnesses authorized by the condemned.[250][251][252] Several states also allow victims' families and relatives selected by the prisoner to watch executions. An hour or two before the execution, the condemned is offered religious services and to choose their last meal (except in Texas which abolished it in 2011).

The execution of Timothy McVeigh on June 11, 2001, was witnessed by over 200 people, most by closed-circuit television. Most were survivors, or relatives of victims of, the 1995 Oklahoma City Bombing, for which McVeigh had been sentenced to death.

Public opinion

هذه section مكتوبة مثل انطباعات شخصية أو مقالة بجريدة وقد تحتاج تنظيف. من فضلك، ساعدنا على تحسينها بإعادة كتابتها بأسلوب موسوعي. (July 2019) |

Gallup, Inc. has monitored support for the death penalty in the United States since 1937. Gallup surveys documented a sharp increase in support for capital punishment between 1966 and 1994.[253]In the late 1990s, support began to wane,[254] falling from 80% in 1994 to 56% in 2019. Approval varies substantially depending on the characteristics of the perpetrator, with much lower support for putting juveniles and the mentally ill to death (26% and 19%, respectively, in 2002).[253] Analysis of death penalty attitudes must account for the responsiveness of societal attitudes, as well as their historical resistance to change.[255]

Pew Research polls have demonstrated declining American support for the death penalty: 80% in 1974, 78% in 1996, 55% in 2014, and 49% in 2016.[256][257] The 2014 poll showed significant differences by race: 63% of whites, 40% of Hispanics and 36% of blacks, respectively, supported the death penalty in that year. However, in 2018, Pew's polls showed public support for the death penalty had increased to 54% from 49%, and in 2021 it again increased to 60% support for the death penalty.[258]

A 2010 poll by Lake Research Partners found that 61% of voters would choose a penalty other than the death sentence for murder.[259] When persons surveyed are given a choice between the death penalty and life without parole for persons convicted of capital crimes, support for execution has traditionally been significantly lower than in polling that asks only if a person does or does not support the death penalty. In Gallup's 2019 survey, support for the sentence of life without parole surpassed that for the death penalty by a margin of 60% to 36%.[253] In November 2009, another Gallup poll found that 77% of Americans believed that the mastermind of the September 11 attacks, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, should receive the death penalty if convicted, 12 points higher than the rate of general support for the death penalty upon Gallup's most recent poll at the time.[260] A similar result was found in 2001 when respondents were polled about the execution of Timothy McVeigh for the Oklahoma City bombing that killed 168 people.[261]

An April 2021 Pew Research poll of 5,109 U.S. adults suggested that Americans continue to favor the death penalty, with 60% in favor for murder (27% strongly in favor), while 39% opposed (15% strongly opposed). 78% of respondents said there is a risk of innocent people being killed in the use of the death penalty.[262]

Debate

Amnesty International and other groups oppose capital punishment on moral grounds.[263]

Some law enforcement organizations, and some victims' rights groups support capital punishment.

The United States is one of the four developed countries that still practice capital punishment, along with Japan, Singapore, and Taiwan.