أرثر ولسلي، دوق ولنگتون الأول

الفيلد مارشال آرثر ولسلي 1769 - 1807 حتى سنة 1809 لم يحمل اسم ولنجتون، فحتى سنة 1798 كان اسمه وسلي Wesley رغم أنه كان بعيدا عن الوزلية (أو المثودية أو المنهجية Methodism). ولد في دبلن Dublin في أول مايو سنة 9671 (قبل مولد نابليون بمائة يوم وخمسة أيام) وكان هو الابن الخامس لگارت وزلي Garret Wesley الإيرل الأول لمورننجتون Mornington مالك مزرعة وعقار إلى الشمال من العاصمة الأيرلندية.

أرسِل إلى مدرسة إيتون Eton وهو في الثانية عشرة من عمره لكنه دعي للعودة إلى منزله بعد ثلاثة أعوام غير مجيدة. وليس هناك ما يشير إلى أنه كان متفوقاً في الرياضة إذ كان حاله فيها كحاله في الدراسة، وفي وقت لاحق شكك في صحة المقولة التي لا نعرف قائلها والتي مؤداها أن معركة واترلو ما كانت ليحقق فيها البريطانيون نصرا لولا ما كان يجري في ملاعب إتون Eton. لقد كانت أمه حزينة تردد دائما قولها إنني ألجأ إلى الله لأعرف ما سأفعله مع ابني آرثر غير البارع(51) لكل هذا فقد تم إلحاقه بالجيش فجرى إرساله وهو في السابعة عشرة من عمره إلى الأكاديمية الملكية في أنجرز Academie Royale de L,Equitation, Angers حيث كان أبناء النبلاء يتعلمون الرياضيات وشيئا من العلوم الإنسانية ويتلقون كثيرا من التدريبات على ركوب الخيل والمبارزة وهي أمور لازمة للضباط.

Wellesley was born into a Protestant Ascendancy family in Ireland. He was commissioned as an ensign in the British Army in 1787, serving in Ireland as aide-de-camp to two successive lords lieutenant of Ireland. He was also elected as a member of Parliament in the Irish House of Commons. Rising to the rank of colonel by 1796, Wellesley saw service in the Low Countries and India, where he fought in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War at the Siege of Seringapatam. He was appointed governor of Seringapatam and Mysore in 1799 and, as a newly appointed major-general, won a decisive victory over the Maratha Confederacy at the Battle of Assaye in 1803.

Rising to prominence as a general officer during the Peninsular War, Wellesley was promoted to the rank of field marshal after leading British-led forces to victory against the French at the Battle of Vitoria in 1813. Following Napoleon's first exile in 1814, he served as the British ambassador to France and was made Duke of Wellington. During the Hundred Days campaign in 1815, Wellington commanded another British-led army which, together with the Prussian Army under Field Marshal Gebhard von Blücher, defeated Napoleon at Waterloo. Wellington's battle record is exemplary; he ultimately participated in some 60 battles during the course of his military career.

Wellington is famous for his adaptive defensive style of warfare, resulting in several victories against numerically superior forces while minimising his own losses. He is regarded as one of the greatest commanders in the modern era,[2] and many of his tactics and battle plans are still studied in military academies around the world. After the end of his active military career, Wellington returned to politics. He was twice British prime minister as a member of the Tory party from 1828 to 1830 and for a little less than a month in 1834. Wellington oversaw the passage of the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, while he opposed the Reform Act 1832. He continued to be one of the leading figures in the House of Lords until his retirement and remained Commander-in-Chief of the Forces until his death.

الحياة المبكرة

العائلة

Wellesley was born into an aristocratic Anglo-Irish family, belonging to the Protestant Ascendancy, beginning life as The Hon. Arthur Wesley.[3] Wellesley was born the son of Anne, Countess of Mornington, and گاريت_وسلي. His father was himself the son of Richard Wesley, 1st Baron Mornington, and had a short career in politics representing the constituency of Trim in the Irish House of Commons before succeeding his father as Baron Mornington in 1758. Garret Mornington was also an accomplished composer, and in recognition of his musical and philanthropic achievements was elevated to the rank of Earl of Mornington in 1760.[4] Wellesley's mother was the eldest daughter of Arthur Hill-Trevor, 1st Viscount Dungannon, after whom Wellesley was named.[5] Through Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, Wellesley was a descendant of Edward I.[6]

Wellesley was the sixth of nine children born to the Earl and Countess of Mornington. His siblings included Richard, Viscount Wellesley, later 1st Marquess Wellesley, 2nd Earl of Mornington, and Baron Maryborough.[7]

تاريخ ومكان الميلاد

The exact date and location of Wellesley's birth is not known, but biographers mostly follow the same contemporary newspaper evidence, which states that he was born on 1 May 1769, the day before he was baptised in St. Peter's Church on Aungier Street in Dublin.[8][9] However, Ernest Lloyd states "registry of St. Peter's Church, Dublin, shows that he was christened there on 30 April 1769". His baptismal font was donated to St. Nahi's Church in Dundrum, Dublin, in 1914.[10]

Wellesley may have been born at his parents' townhouse, Mornington House at 6 Merrion Street (the address later became known as 24 Upper Merrion Street),[11] Dublin, which now forms part of the Merrion Hotel.[12] His mother, Anne, Countess of Mornington, recalled in 1815 that he had been born at 6 Merrion Street.[11]

His family's home at Dangan Castle, Dangan near Summerhill, County Meath has also been purported to have been his birthplace.[13][14] In his obituary, published in The Times in 1852, it was reported that Dangan was unanimously believed to have been the place of his birth, though suggested it was unlikely, but not impossible, that the family had travelled to Dublin for his baptism.[15] A pillar was erected in his honour near Dangan in 1817.[16]

The place of his birth has been much disputed following his death, with Sir J.B. Burke writing the following in 1873:

"Isn't it remarkable that until recently all the old memoirs of the Duke of Wellington seemed to infer that County Meath was the place of birth. Nowadays the theory that he was born in Dublin is generally accepted but by no means proved".[17]

Other places that have been put forward as the location of his birth include a coach between Meath and Dublin, the Dublin packet boat and the Wellesley townhouse in Trim, County Meath.[18]

الطفولة

Wellesley spent most of his childhood at his family's two homes, the first a large house in Dublin, Mornington House, and the second Dangan Castle, 3 miles (5 km) north of Summerhill in County Meath.[19] In 1781, Arthur's father died and his eldest brother Richard inherited his father's earldom.[20]

He went to the diocesan school in Trim when at Dangan, Mr Whyte's Academy when in Dublin, and Brown's School in Chelsea when in London. He then enrolled at Eton College, where he studied from 1781 to 1784.[20] His loneliness there caused him to hate it, and makes it highly unlikely that he actually said "The Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton", a quotation which is often attributed to him. Moreover, Eton had no playing fields at the time. In 1785, a lack of success at Eton, combined with a shortage of family funds due to his father's death, forced the young Wellesley and his mother to move to Brussels.[21] Until his early twenties, Arthur showed little sign of distinction and his mother grew increasingly concerned at his idleness, stating, "I don't know what I shall do with my awkward son Arthur."[21]

In 1786, Arthur enrolled in the French Royal Academy of Equitation in Angers, where he progressed significantly, becoming a good horseman and learning French, which later proved very useful.[22] Upon returning to England later the same year, he astonished his mother with his improvement.[23]

السيرة العسكرية المبكرة

عندما فاز بجوائزه - بفضل نفوذ أسرته أو مقابل دفع الأموال - تم تعيينه معاوناً للورد ليفتنانت أيرلندا كما شغل مقعداً في مجلس العموم في أيرلندا ممثلاً لمدينة تريم Trim.

أيرلندا

Despite his new promise, Wellesley had yet to find a job and his family was still short of money, so upon the advice of his mother, his brother Richard asked his friend the Duke of Rutland (then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland) to consider Arthur for a commission in the Army.[23] Soon afterward, on 7 March 1787, he was gazetted ensign in the 73rd Regiment of Foot.[24][25] In October, with the assistance of his brother, he was assigned as aide-de-camp, on ten shillings a day (twice his pay as an ensign), to the new Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Buckingham.[24] He was also transferred to the new 76th Regiment forming in Ireland and on Christmas Day, 1787, was promoted lieutenant.[24][26] During his time in Dublin his duties were mainly social; attending balls, entertaining guests and providing advice to Buckingham. While in Ireland, he overextended himself in borrowing due to his occasional gambling, but in his defence stated that "I have often known what it was to be in want of money, but I have never got helplessly into debt".[27]

On 23 January 1788, he transferred into the 41st Regiment of Foot,[28] then again on 25 June 1789 he transferred to the 12th (Prince of Wales's) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons[29] and, according to military historian Richard Holmes, he also reluctantly entered politics.[27] Shortly before the general election of 1789, he went to the rotten borough of Trim to speak against the granting of the title "Freeman" of Dublin to the parliamentary leader of the Irish Patriot Party, Henry Grattan.[30] Succeeding, he was later nominated and duly elected as a Member of Parliament (MP) for Trim in the Irish House of Commons.[31] Because of the limited suffrage at the time, he sat in a parliament where at least two-thirds of the members owed their election to the landowners of fewer than a hundred boroughs.[31] Wellesley continued to serve at Dublin Castle, voting with the government in the Irish parliament over the next two years. He became a captain on 30 January 1791, and was transferred to the 58th Regiment of Foot.[31][32][33]

On 31 October, he transferred to the 18th Light Dragoons[34] and it was during this period that he grew increasingly attracted to Kitty Pakenham, the daughter of Edward Pakenham, 2nd Baron Longford.[35] She was described as being full of 'gaiety and charm'.[36] In 1793, he proposed, but was turned down by her brother Thomas, 2nd Earl of Longford, who considered Wellesley to be a young man, in debt, with very poor prospects.[37] An aspiring amateur musician, Wellesley, devastated by the rejection, burnt his violins in anger, and resolved to pursue a military career in earnest.[38] He became a major by purchase in the 33rd Regiment in 1793.[35][39] A few months later, in September, his brother lent him more money and with it he purchased a lieutenant-colonelcy in the 33rd.[40][41]

هولندا

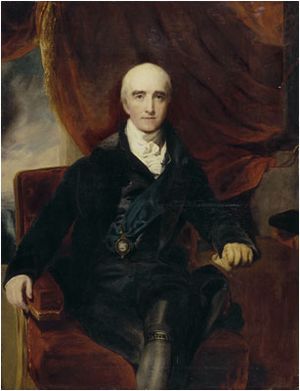

وفي سنة 9971 أصبح ليفتنانت كولونيل وقاد ثلاث كتائب لغزو الفلاندر Flanders وعاد من هذه المغامرة غير الناجحة مشمئزاً من الحرب ممرغاً في الوحل متهما بعدم الكفاءة حتى إنه فكر في ترك الجيش والانخراط في الحياة المدنية. لقد كان يفضل الكمان على الثكنات العسكرية وكان يعاني آلاما متلاحقة، وكان من رأي أخيه مورننجتون أن أحداً لا يجب أن يتوقع منه الكثير لنقص كفاءته. وقد رسمه جون هوبنر Hopner في صورة تظهره وهو في السادسة والعشرين بعينين كعيني شاعر، وبوسامة كوسامة بايرون. وقد رشح - مثل بايرون - للزواج من ليدي نبيلة رفضت الاقتران به.

الهند

وفي سنة 6971 ذهب إلى الهند كولونيلاً تحت قيادة أخيه ريتشارد الذي هو الآن (في هذه الفترة) المركيز ويلزلي Wellesley وأصبح حاكما لمدراس Madras ثم البنغال. وضم بعض الإمارات الهندية للإمبراطورية البريطانية.

سريرانگاپاتنا وميسور

لقد أحرز آرثر ويلزلي Arthur Wellesley (كما أصبح دوق المستقبل يكتب اسمه) بعض الانتصارات الباهرة في هذه المعارك في الهند، ومنح لقب فارس في سنة 4081.

العودة إلى بريطانيا

وعندما عاد إلى إنجلترا ضمن لنفسه مقعدا في البرلمان البريطاني وتقدم مرة أخرى لطلب يد كاثي باكنهام Cathey Pakenham فقبلته (6081) فعاش معها غير سعيد حتى تعلم كل منهما العيش بمعزل عن الآخر، وقد أنجب منها طفلين. وواصل الترقي من منصب إلى آخر، ولم يكن هذا بتقديم الرشا وإنما كان في الأساس لشهرته بالتحليلات الدقيقة والإنجازات المتسمة بالكفاءة. وقد وصفه وليم بت Pitt قرب موته بأنه رجل يضع في اعتباره كل الصعوبات قبل القيام بمهمة فلا يبقى من هذه الصعوبات شيء بعد إتمام المهمة(71) وفي سنة 7081 أصبح وزيرا أول لشؤون أيرلندا في وزارة دوق بورتلاند Duke of Portland.

حرب شبه الجزيرة الأيبيرية

مقالة مفصلة: حرب شبه الجزيرة الأيبيرية

مقالة مفصلة: حرب شبه الجزيرة الأيبيرية

وفي سنة 8081 أصبح ليفتنانت جنرال، وفي شهر يوليو من العام نفسه عهد إليه بقيادة 00531 مقاتل لطرد جونو Junot والفرنسيين من البرتغال. وفي أول أغسطس رسا برجاله في ساحل خليج موندگو Mondego إلى الشمال من لشبونه بمائة ميل. وانضم إليه هناك نحو 0005 برتغالي، ووصله خطاب من وزارة الحرب تعده فيه بإمداده بمحاربين آخرين عددهم 00051 في أقرب وقت، لكن الخطاب أضاف أن السير هيو دالرمپل Hew Dalrymple البالغ من العمر ثمانية وخمسين عاما سيكون على رأس هذا المدد وسيتولى القيادة العليا للحملة كلها، ولكن ويلزلي Wellesley كان قد وضع خططه بالفعل ولم يكن سعيدا بالعمل تحت قيادة قائد آخر، فقرر ألا ينتظر وصول المدد المكون من 15,000 مقاتل، فاتجه شمالا على رأس رجاله البالغ عددهم 005،81 ليخوض المعركة التي ستحدد مصير جونو Junot ومصيره (أي مصير ويلزلي)، وكان جونو Junot قد سمح لرجاله بالانغماس في اللهو بكل أنواعه في العاصمة، وكان على رأس 13,000 مقاتل، فقبل التحدي لكنه عانى هزيمة منكرة في ڤيميرو Vimeiro بالقرب من لشبونة (12 أغسطس 8081).

ووصل دالريمبل Dalrymple بعد المعركة فتولى القيادة، وأوقف مواصلة زحف القوات البريطانية ورتب مع جونو Junot اتفاق سنترا Cintra (3 سبتمبر) يسلم بمقتضاه كل المدن والحصون التي كان الفرنسيون قد استولوا عليها في البرتغال، على أن ينسحب بمن بقي من رجاله بأمان، ووافق البريطانيون على تقديم سفنهم لنقل الراغبين في العودة إلى فرنسا، ووقع ويلزلي Wellesley الوثيقة شاعراً أن تحرير البرتغال بمعركة واحدة أمر يستحق من بريطانيا بعض الرضا. واتفاق سنترا Cintra هذا هو الاتفاق الذي وافق الشاعران وردزورث ولورد بايرون على أنه غباء لا يصدق (وإن كانا لم يرددا هذا الرأي بعد ذلك إلا نادرا) فهؤلاء المقاتلون الفرنسيون الذين تم إطلاق سراحهم سرعان ماسيجندون مرة أخرى لمحاربة بريطانيا وحلفائها. وتم استدعاء ويلزلي Wellesely إلى لندن لا ستجوابه، فذهب غير آسف تماما فهو لم يكن راغبا في الخدمة تحت قيادة دالريمبل Dalrymple وكان يكره الحرب بالفعل. لقد قال بعد أن حقق انتصارات كثيرة اسمع رأيي عن الحرب: إنك إن خضت الحرب ولو ليوم واحد فستدعو الله القدير ألا تشهدها ولو لساعة واحدة مرة أخرى(81). ويبدو أنه أقنع محاكميه أن اتفاق سنترا قد أنقذ حياة الآلاف من البريطانيين وحلفائهم بمنع القوات الفرنسية من إبداء المزيد من المقاومة. وبعد ذلك عاد إلى أيرلندا منتظراً فرصة أفضل لخدمة بلاده واسمه ذي السمعة الطيبة.

حرب شبه الجزيرة الأيبيرية: الحرب الثالثة 1808 - 1812

لقد كان ملك أسبانيا جوزيف بونابرت في اضطراب لا مزيد عليه. لقد عمل على اكتساب قبول واسع أكثر من القبول الذي حباه به بعض الليبراليين. وكان الليبراليون يؤيدون إجراءات المصادرة ضد الكنيسة الثرية ولكن جوزيف الذي كان يعاني من شهرته كلا أدري (اللاأدري هو الموقن بأن الأمور غير المادية يصعب الوصول إليها باليقين الإيماني) كان يدرك أن أي تصرف منه ضد رجال الدين سيسارع يإشعال نيران المقاومة ضد الحكم الأجنبي (الفرنسي) وكانت الجيوش الإسبانية التي هزمها نابليون قد جرى تشكيلها من جديد في مناطق أسبانية متفرقة، حقيقة أنها لم تكن منظمة منضبطة، لكنها كانت متحمسة. واستمرت حرب العصابات التي يشنها الفلاحون ضد مغتصبي العرش كل عام في الفترة ما بين موسم البذر وموسم الحصاد، وكان يتحتم على الجيش الفرنسي في أسبانيا أن يقسم نفسه إلى قوات متفرقة يقودها جنرالات متحاسدون يخوضون معارك في جو من الفوضى وعدم الانضباط أعجز جهود نابليون للتنسيق بينهم من مقره في باريس. قال كارل ماركس لقد تعلم نابليون درساً مفاده أنه إذا كانت الدولة الإسبانية قد ماتت، فإن المجتمع الإسباني لا يزال مفعما بالحياة وأن كل جانب منه يفيض رغبة في المقاومة.. لقد كان محور المقاومة الإسبانية في كل مكان وليس في مكان واحد(91). وبعد انهيار الجيش الفرنسي الرئيسي في بيلن Bailen انضم الجانب الرئيس من الأرستقراطية الإسبانية إلى الثورة وبذلك حولوا الكراهية الشعبية التي كانت موجهة إليهم إلى الغزاة.

وكان للتأييد الفعال الذي قدمه رجال الدين الإسبان للثورة أثره المهم في تحويل الحركة عن الأفكار الليبرالية، بل لقد حدث العكس فقد أدى نجاح حرب التحرير الإسبانية إلى تقوية الكنيسة ومحاكم التفتيش(02). ومع هذا فقد ظلت بعض العناصر الليبرالية موجودة في المجالس السياسية Juntas في المديريات (الولايات) الإسبانية المختلفة، وكانت هذه المجالس ترسل ممثلين عنها للمجلس الرئيسي (على مستوى الوطن كله) في قادش Cadiz، وكان هؤلاء يكتبون دستورا جديدا. لقد كانت شبه الجزيرة الأيبيرية مفعمة بالعصيان المسلح والآمال والإيمان الكاثوليكي، بينما كان جوزيف بونابرت يتطلع إلى نابلي، في حين كان نابليون يحارب النمسا وكان ويلزلي Wellesely (ولنجتون) يستعد لينقض مرة ثانية من إنجلترا ليساعد في عودة أسبانيا إلى ما كانت عليه في العصور الوسطى، مع أنه هو نفسه (ويلزلي) كان رجلا عصريا بكل معنى الكلمة. وكان السير جون مور John Moore - قبل موته في كورونا Corunna (61 يناير 9081) قد نصح الحكومة البريطانية ألا تقوم بمحاولات أخرى للسيطرة على البرتغال، فقد كان يعتقد أن الفرنسيين سينفذون أوامر نابليون بضم البرتغال إلى فرنسا عاجلاً أم آجلا، كما كان يعتقد أن إنجلترا لن تجد وسيلة لنقل العدد العدد الكافي من الجنود لمواجهة 000،001 جندي فرنسي موسمى في أسبانيا كما أنها لن تتمكن من تدبير المؤن اللازمة لجنودها. لكن السير آرثر ويلزلي كان قلقا في أيرلندا وأخبر وزير الحرب أنه إذا أتاح له قيادة عشرين ألف أو ثلاثين ألف جندي بريطاني ودعم وطني، فإنه يستطيع أن يحفظ البرتغال بعيدة عن قبضة أي جيش فرنسي لايزيد عن 000،001 مقاتل(12)، ووافقت الحكومة البريطانية وألزمته بكلماته، وفي 22 أبريل سنة 9081 وصل إلى لشبونة على رأس 000،52 بريطاني وصفهم في وقت لاحق بأنهم حثالة الأرض... ومجموعة من الأوغاد.. لايمكن السيطرة عليهم إلا بالسياط، إذ إنهم لم يخلقوا إلا للسكر(22). لكنهم يستطيعون القتال بشراسة إذا لم يكن أمامهم سوى خيار واحد: إما أن يقتلوا (بفتح الياء) أو يقتلوا (بضم الياء). وتحسبا لوصول ويلزلي وقواته، حرك المارشال سولت Soult 000،32 جندي فرنسي إلى أوبورتو Oporto وفي هذه الأثناء كان جيش فرنسي آخر بقيادة المارشال كلود فكتور Claude Victor يتقدم من الغرب على طول التاجوس Tagus. وقرر ويلزلي Wellesley - الذي كان قد درس معارك نابليون بدقة - أن يهاجم سولت Soult قبل أن يتمكن المارشلان من ضمّ قواتهما معاً لشنّ هجوم على لشبونة التي تمكن البريطانيون منها. وبعد أن انضم إلى قوات ويلزلي البالغة 000،52 مقاتل، 000،51 مقاتل برتغالي بقيادة وليام كار برسفورد W. Carr Beresford (ڤايكونت برسفورد) قادهم جميعا إلى نقطة على نهر دورو Douro في مواجهة أو اوپورتو Oporto.

وفي 21 مايو سنة 9081 عبر مجرى النهر وهاجم مؤخرة جيش سولت Soult بشكل مفاجئ فتراجع الجيش الفرنسي وعمته الفوضى، وخسر الجيش الفرنسي 0006 قتيل وكل مدفعيته، ولم يتعقب ويلزلي الجيش الفرنسي المنهزم فقد كان عليه أن يسرع جنوبا للتصدي لجيش فرنسي آخر بقيادة فيكتور، لكن فيكتور بعد أن علم بهزيمة سولت Soult استدار عائداً إلى تالافيرا Talavera وهناك تلقى من جوزيف مددا زاد من عدد جيشه ليصبح 000،64 مقاتل، ولم تكن قوات ويلزلي تزيد على 000،32 بريطاني و 000،63 أسباني، والتقى الجيشان في تالافيرا في 82 يوليو سنة 9081، وهرب الجنود الإسبان ومع هذا فقد تمكن ويلزلي من تكبيد جيش فكتور 0007 قتيل وجريح واستولى منه على 71 مدفعا. وسيطر ويلزلي على ميدان المعركة رغم أن جيشه فقد 0005 ما بين قتيل وجريح، وقدرت الحكومة البريطانية كفاءة ويلزلي وشجاعته فأصبح يحمل لقب فيكونت ولنجتون ومع هذا فقد أدى انتصار نابليون في معركة واجرام Wagram (9081) وزواجه من ابنة الإمبراطور النمساوي (مارس 1810) إلى وضع حد لولاء النمسا لإنجلترا. وكانت روسيا لا تزال حليفة لفرنسا، وكان هناك 138,000 جندي فرنسي إضافي مستعدين للخدمة العسكرية في أسبانيا، وكان المارشال أندريه ماسينا Andre Massena بجنوده البالغ عددهم 000و56 يخطط للخروج بهم من أسبانيا لغزو البرتغال. وأخبرت الحكومة البريطانية ولنجتون أنه إذا غزا الفرنسيون أسبانيا مرة أخرى فلا جناح عليه إن انسحب بجيشه إلى إنجلترا(32). وكانت هذه لحظة حرجة في مهمة ولنجتون، فالانسحاب - رغم أن الحكومة البريطانية قد سمحت به - قد يلوث سجله إذا لم يحقق نصراً كبيرا على نحو ما يخفف من وطأة الانسحاب، فقرر أن يخاطر برجاله وبمهمته وبحياته بضربة أخرى تعتمد على الحظ (برمية نَرْد أخرى)، وفي هذه الأثناء كان قد جعل رجاله يقيمون خطا من التحصينات إلى الشمال من قاعدته في لشبونة بخمسة وعشرين ميلا من التاجوس Tagus وعبر تورز فيدراس Torres Vedras حتى البحر. وبدأ ماسينا Massena معركته بالاستيلاء على حصن سيوداد رودريجو Ciudad Rodrigo الإسباني ثم عبر إلى البرتغال بستين ألف مقاتل. وكان ولنجتون على رأس 000،25 من المتحالفين (بريطانيين وأسبان وبرتغاليين) فالتقى به في بوساكو Bussaco (شمال كويمبرا Coimbra) في 72 سبتمبر سنة 0181 فتكبّد 0521 ما بين قتيل وجريح أما ماسينا فتكبّد 006،4، ومع هذا فقد أدرك ولنجتون أنه لن يستطيع - كماسينا - التعويل على مدد يأتيه، لذا فقد تراجع إلى تحصينات تورس فيدراس Torres Vedras وأمر رجاله باتباع سياسة الأرض المحروقة أي تدمير كل ما يلقونه في طريق تراجعهم حتى يعاني جيش ما سينا من الجوع، وفي 5 مارس سنة 1181 قاد ماسينا جنوده الجياع عائداً إلى أسبانيا وأسلم القيادة لأوجست مارمون Auguste Marmont. وبعد أن قضى ولنجتون فترة الشتاء في الراحة وتدريب رجاله أخذ المبادرة فاتجه إلى أسبانيا على رأس جنوده البالغ عددهم 000،05 وهاجم قوات مارمون البالغ عددها 000،84 بالقرب من سالامانكا Salamanca في 22 يوليو 2181، ففقدت القوات الفرنسية 000،41 ما بين قتيل وجريح بينما فقد البريطانيون وحلفاؤهم 007،4، وانسحب مارمون.

وفي 12 يوليو غادر الملك جوزيف بونابرت مدريد على رأس 000،51 مقاتل لتقديم النجدة لمارمون، لكنه علم في أثناء الطريق بما حل بمارمون من هزيمة، فلم يجرؤ (أي الملك جوزيف بونابرت) على العودة للعاصمة (مدريد) فقاد قواته إلى فالنسيا Valencia ليلحق هناك بجيش فرنسي أكبر عددا بقيادة المارشال سوشيه Sochet ولحق به - بعجلة وفوضى - 10,000 من المتفرنسين (المؤيدين للحكم الفرنسي من الإسبان والبرتغاليين) وحاشيته وموظفوه. وفي 21 أغسطس دخل ولنجتون مدريد فرحبت به الجماهير بحماس بالغ، تلك الجماهير التي ظلت غير مفتونة بدستور نابليون. وكتب ولنجتون لأحد أصدقائه إنني بين أُناس يكاد الفرح يذهب بعقولهم. لقد منحني الرب حظاً سعيداً أرجو أن يستمر لأكون أداة لتحقيق استقلاله(42). لكن الرب تردّد فلم يُعطه استمراراً لهذا الحظ فقد أعاد مارمون تنظيم جيشه خلف تحصينات بورجو Burgos، فحاصره ولنجتون هناك؛، وتقدم جوزيف من فالنسيا Valencia على رأس 0009 مقاتل لمواجهة القوات البريطانية والمتحالفين معها، فتراجع ولنجتون (81 أكتوبر 2181) متجاوزاً سالامانكا إلى سيوداد رودريجو Ciudad Rodrigo وفقد في أثناء تراجعه 0006 من قواته (بين قتيل وجريح)، ودخل جوزيف مدريد مرة أخرى وسط استياء عارم من الجماهير، وإن ابتهجت الطبقة الوسطى لعودته، وفي هذه الأثناء كان نابليون يرتجف في موسكو، وظلت أسبانيا - مثلها في ذلك مثل سائر أوروبا - في انتظار نتيجة مغامرته التي ستؤثر في أحوال القارة الأوروبية.

معركة واترلو

مقالة مفصلة: معركة واترلو

مقالة مفصلة: معركة واترلو

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). It commenced with a diversionary attack on Hougoumont by a division of French soldiers. After a barrage of 80 cannons, the first French infantry attack was launched by Comte D'Erlon's I Corps. D'Erlon's troops advanced through the Allied centre, resulting in Allied troops in front of the ridge retreating in disorder through the main position. D'Erlon's corps stormed the most fortified Allied position, La Haye Sainte, but failed to take it. An Allied division under Thomas Picton met the remainder of D'Erlon's corps head to head, engaging them in an infantry duel in which Picton was killed. During this struggle Lord Uxbridge launched two of his cavalry brigades at the enemy, catching the French infantry off guard, driving them to the bottom of the slope, and capturing two French Imperial Eagles. The charge, however, over-reached itself, and the British cavalry, crushed by fresh French horsemen sent at them by Napoleon, were driven back, suffering tremendous losses.[42]

Shortly before 16:00, Marshal Ney noted an apparent withdrawal from Wellington's centre. He mistook the movement of casualties to the rear for the beginnings of a retreat, and sought to exploit it. Ney at this time had few infantry reserves left, as most of the infantry had been committed either to the futile Hougoumont attack or to the defence of the French right. Ney, therefore, tried to break Wellington's centre with a cavalry charge alone.[43]

At about 16:30, the first Prussian corps arrived. Commanded by Freiherr von Bülow, IV Corps arrived as the French cavalry attack was in full spate. Bülow sent the 15th Brigade to link up with Wellington's left flank in the Frichermont–La Haie area while the brigade's horse artillery battery and additional brigade artillery deployed to its left in support.[45] Napoleon sent Lobau's corps to intercept the rest of Bülow's IV Corps proceeding to Plancenoit. The 15th Brigade sent Lobau's corps into retreat to the Plancenoit area. Von Hiller's 16th Brigade also pushed forward with six battalions against Plancenoit. Napoleon had dispatched all eight battalions of the Young Guard to reinforce Lobau, who was now seriously pressed by the enemy. Napoleon's Young Guard counter-attacked and, after very hard fighting, secured Plancenoit, but were themselves counter-attacked and driven out.[46] Napoleon then resorted to sending two battalions of the Middle and Old Guard into Plancenoit and after ferocious fighting they recaptured the village.[46] The French cavalry attacked the British infantry squares many times, each at a heavy cost to the French but with few British casualties. Ney himself was displaced from his horse four times.[47] Eventually, it became obvious, even to Ney, that cavalry alone were achieving little. Belatedly, he organised a combined-arms attack, using Bachelu's division and Tissot's regiment of Foy's division from Reille's II Corps plus those French cavalry that remained in a fit state to fight. This assault was directed along much the same route as the previous heavy cavalry attacks.[48]

Meanwhile, at approximately the same time as Ney's combined-arms assault on the centre-right of Wellington's line, Napoleon ordered Ney to capture La Haye Sainte at whatever the cost. Ney accomplished this with what was left of D'Erlon's corps soon after 18:00. Ney then moved horse artillery up towards Wellington's centre and began to attack the infantry squares at short-range with canister.[43] This all but destroyed the 27th (Inniskilling) Regiment, and the 30th and 73rd Regiments suffered such heavy losses that they had to combine to form a viable square. Wellington's centre was now on the verge of collapse and wide open to an attack from the French. Luckily for Wellington, Pirch I's and Zieten's corps of the Prussian Army were now at hand. Zieten's corps permitted the two fresh cavalry brigades of Vivian and Vandeleur on Wellington's extreme left to be moved and posted behind the depleted centre. Pirch I Corps then proceeded to support Bülow and together they regained possession of Plancenoit, and once more the Charleroi road was swept by Prussian round shot. The value of this reinforcement is held in high regard.[49]

The French army now fiercely attacked the Coalition all along the line with the culminating point being reached when Napoleon sent forward the Imperial Guard at 19:30. The attack of the Imperial Guards was mounted by five battalions of the Middle Guard, and not by the Grenadiers or Chasseurs of the Old Guard. Marching through a hail of canister and skirmisher fire and severely outnumbered, the 3,000 or so Middle Guardsmen advanced to the west of La Haye Sainte and proceeded to separate into three distinct attack forces. One, consisting of two battalions of Grenadiers, defeated the Coalition's first line and marched on. Chassé's relatively fresh Dutch division was sent against them, and Allied artillery fired into the victorious Grenadiers' flank. This still could not stop the Guard's advance, so Chassé ordered his first brigade to charge the outnumbered French, who faltered and broke.[50]

Further to the west, 1,500 British Foot Guards under Maitland were lying down to protect themselves from the French artillery. As two battalions of Chasseurs approached, the second prong of the Imperial Guard's attack, Maitland's guardsmen rose and devastated them with point-blank volleys. The Chasseurs deployed to counter-attack but began to waver. A bayonet charge by the Foot Guards then broke them. The third prong, a fresh Chasseur battalion, now came up in support. The British guardsmen retreated with these Chasseurs in pursuit, but the latter were halted as the 52nd Light Infantry wheeled in line onto their flank and poured a devastating fire into them and then charged.[50][51] Under this onslaught, they too broke.[51]

The last of the Guard retreated headlong. Mass panic ensued through the French lines as the news spread: "La Garde recule. Sauve qui peut!" ("The Guard is retreating. Every man for himself!"). Wellington then stood up in Copenhagen's stirrups, and waved his hat in the air to signal an advance of the Allied line just as the Prussians were overrunning the French positions to the east. What remained of the French army then abandoned the field in disorder. Wellington and Blücher met at the inn of La Belle Alliance, on the north–south road which bisected the battlefield, and it was agreed that the Prussians should pursue the retreating French army back to France.[50] The Treaty of Paris was signed on 20 November 1815.[52]

After the victory, the Duke supported proposals that a medal be awarded to all British soldiers who participated in the Waterloo campaign, and on 28 June 1815, he wrote to the Duke of York suggesting:

... the expediency of giving to the non-commissioned officers and soldiers engaged in the Battle of Waterloo a medal. I am convinced it would have the best effect in the army, and if the battle should settle our concerns, they will well deserve it.

The Waterloo Medal was duly authorised and distributed to all ranks in 1816.[53]

Controversy

Much historical discussion has been made about Napoleon's decision to send 33,000 troops under Marshal Grouchy to intercept the Prussians, but—having defeated Blücher at Ligny on 16 June and forced the Allies to retreat in divergent directions—Napoleon may have been strategically astute in a judgement that he would have been unable to beat the combined Allied forces on one battlefield. Wellington's comparable strategic gamble was to leave 17,000 troops and artillery, mostly Dutch, 8.1 mi (13.0 km) away at Hal, north-west of Mont-Saint-Jean, in case of a French advance up the Mons-Hal-Brussels road.[54]

The campaign led to numerous other controversies. Issues concerning Wellington's troop dispositions prior to Napoleon's invasion of the Netherlands, whether Wellington misled or betrayed Blücher by promising, then failing, to come directly to Blücher's aid at Ligny, and credit for the victory between Wellington and the Prussians. These and other such issues concerning Blücher's, Wellington's, and Napoleon's decisions during the campaign were the subject of a strategic-level study by the Prussian political-military theorist Carl von Clausewitz, Feldzug von 1815: Strategische Uebersicht des Feldzugs von 1815, (English title: The Campaign of 1815: Strategic Overview of the Campaign.)[أ] This study was Clausewitz's last such work and is widely considered to be the best example of Clausewitz's mature theories concerning such analyses.[55] It attracted the attention of Wellington's staff, who prompted the Duke to write a published essay on the campaign (other than his immediate, official after-action report, "The Waterloo Dispatch".) This was published as the 1842 "Memorandum on the Battle of Waterloo". While Wellington disputed Clausewitz on several points, Clausewitz largely absolved Wellington of accusations levelled against him. This exchange with Clausewitz was quite famous in Britain in the 19th century, particularly in Charles Cornwallis Chesney's work the Waterloo Lectures, but was largely ignored in the 20th century due to hostilities between Britain and Germany.[56]

Army of occupation in Paris

Under the terms of the Treaty of Paris, Wellington was appointed commander of the multi-national army of occupation based in Paris. The army consisted of troops from the United Kingdom, Austria, Russia and Prussia, along with contributions from five smaller European states. Although the various contingents were administered by their own commanders, they were all subordinated to Wellington, who was also responsible for liaison with the French administration. The role of the army was to prevent a resurgence of French aggression and to allow the restored King Louis XVIII to consolidate his control over the country. The army of occupation was never required to intervene militarily and was dissolved in 1818, after which Wellington returned to Britain. It was his last active military command.[57]

رجل دولة

Wellington entered politics again in 1819, when he was appointed Master-General of the Ordnance in the Tory government of Lord Liverpool. In 1827, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Army.

رئيس الوزراء

First term

| جزء من سلسلة سياسية عن |

| فكر التوري |

|---|

|

Wellington entered politics again when he was appointed Master-General of the Ordnance in the Tory government of Lord Liverpool on 26 December 1818.[58] He also became Governor of Plymouth on 9 October 1819.[59] He was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Army on 22 January 1827[60][61] and Constable of the Tower of London on 5 February 1827.[62]

Along with Robert Peel, Wellington became an increasingly influential member of the Tory party, and in 1828 he resigned as Commander-in-Chief and became prime minister.[63]

During his first seven months as prime minister, he chose not to live in the official residence at 10 Downing Street, finding it too small. He moved in only because his own home, Apsley House, required extensive renovations. During this time he was largely instrumental in the foundation of King's College London. On 20 January 1829 Wellington was appointed Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports.[64]

Reform

Catholic emancipation

His term was marked by Roman Catholic Emancipation: the restoration of most civil rights to Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The change was prompted by the landslide by-election win of Daniel O'Connell, a Roman Catholic Irish proponent of emancipation, who was elected despite not being legally allowed to sit in Parliament. In the House of Lords, facing stiff opposition, Wellington spoke for Catholic Emancipation, and according to some sources, gave one of the best speeches of his career.[65] Wellington was born in Ireland and so had some understanding of the grievances of the Roman Catholic majority there; as Chief Secretary, he had given an undertaking that the remaining Penal Laws would only be enforced as "mildly" as possible.[66] In 1811 Catholic soldiers were given freedom of worship[67] and 18 years later the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 was passed with a majority of 105. Many Tories voted against the Act, and it passed only with the help of the Whigs.[68] Wellington had threatened to resign as prime minister if King George IV did not give Royal Assent.[69]

Duel with Winchilsea

The Earl of Winchilsea accused the Duke of "an insidious design for the infringement of our liberties and the introduction of Popery into every department of the State".[70] Wellington responded by immediately challenging Winchilsea to a duel. On 21 March 1829, Wellington and Winchilsea met on Battersea fields. When the time came to fire, the Duke took aim and Winchilsea kept his arm down. The Duke fired wide to the right. Accounts differ as to whether he missed on purpose, an act known in duelling as a delope. Wellington claimed he did. However, he was noted for his poor aim and reports more sympathetic to Winchilsea claimed he had aimed to kill. Winchilsea discharged his pistol into the air, a plan he and his second had almost certainly decided upon before the duel.[71] Honour was saved and Winchilsea wrote Wellington an apology.[70][72]

The nickname "Iron Duke" originated from this period, when he experienced a high degree of personal and political unpopularity. Its repeated use in Freeman's Journal throughout June 1830 appears to bear reference to his resolute political will, with taints of disapproval from its Irish editors.[73][74][75] During this time, Wellington was greeted by a hostile reaction from the crowds at the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.[76]

Resignation and aftermath

Wellington's government fell in 1830. In the summer and autumn of that year, a wave of riots swept the country.[77] The Whigs had been out of power for most years since the 1770s, and saw political reform in response to the unrest as the key to their return. Wellington stuck to the Tory policy of no reform and no expansion of suffrage, and as a result, lost a vote of no confidence on 15 November 1830.[78]

The Whigs introduced the first Reform Bill while Wellington and the Tories worked to prevent its passage. The Whigs could not get the bill past its second reading in the British House of Commons, and the attempt failed. An election followed in direct response and the Whigs were returned with a landslide majority. A second Reform Act was introduced and passed in the House of Commons but was defeated in the Tory-controlled House of Lords. Another wave of near-insurrection swept the country. Wellington's residence at Apsley House was targeted by a mob of demonstrators on 27 April 1831 and again on 12 October, leaving his windows smashed.[79] Iron shutters were installed in June 1832 to prevent further damage by crowds angry over rejection of the Reform Bill, which he strongly opposed.[80] The Whig Government fell in 1832 and Wellington was unable to form a Tory Government partly because of a run on the Bank of England. This left King William IV no choice but to restore Earl Grey to the premiership. Eventually, the bill passed the House of Lords after the King threatened to fill that House with newly created Whig peers if it were not. Wellington was never reconciled to the change; when Parliament first met after the first election under the widened franchise, Wellington is reported to have said "I never saw so many shocking bad hats in my life".[81]

Wellington opposed the Jewish Civil Disabilities Repeal Bill, and he stated in Parliament on 1 August 1833 that England "is a Christian country and a Christian legislature, and that the effect of this measure would be to remove that peculiar character." The Bill was defeated by 104 votes to 54.[82]

Government

Wellington was gradually superseded as leader of the Tories by Robert Peel, while the party evolved into the Conservatives. When the Tories were returned to power in 1834, Wellington declined to become prime minister because he thought membership in the House of Commons had become essential. The king reluctantly approved Peel, who was in Italy. Hence, Wellington acted as interim leader for three weeks in November and December 1834, taking the responsibilities of prime minister and most of the other ministries.[83] In Peel's first cabinet (1834–1835), Wellington became foreign secretary, while in the second (1841–1846) he was a minister without portfolio and Leader of the House of Lords.[84] Wellington was also re-appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Army on 15 August 1842 following the resignation of Lord Hill.[85]

Wellington served as the leader of the Conservative party in the House of Lords from 1828 to 1846. Some historians have belittled him as a befuddled reactionary, but a consensus in the late 20th century depicts him as a shrewd operator who hid his cleverness behind the façade of a poorly informed old soldier. Wellington worked to transform the Lords from unstinting support of the Crown to an active player in political manoeuvering, with a commitment to the landed aristocracy. He used his London residence as a venue for intimate dinners and private consultations, together with extensive correspondence that kept him in close touch with party leaders in the Commons, and the main persona in the Lords. He gave public rhetorical support to Ultra-Tory anti-reform positions, but then deftly changed positions toward the party's centre, especially when Peel needed support from the upper house. Wellington's success was based on the 44 elected peers from Scotland and Ireland, whose elections he controlled.[86]

التقاعد والوفاة

Family

Wellesley was married by his brother Gerald, a clergyman, to Kitty Pakenham in St George's Church, Dublin, on 10 April 1806.[87] They had two children: Arthur was born in 1807 and Charles was born in 1808. The marriage proved unsatisfactory and the two spent years apart, while Wellesley was campaigning and afterwards. Kitty grew depressed, and Wellesley pursued other sexual and romantic partners.[88][89] The couple largely lived apart, with Kitty spending most of her time at their country home, Stratfield Saye House, and Wellesley at their London home, Apsley House. Kitty's brother Edward Pakenham served under Wellesley throughout the Peninsular War, and Wellesley's regard for him helped to smooth his relations with Kitty, until Pakenham's death at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815.[90]

Retirement

Wellington retired from political life in 1846, although he remained Commander-in-Chief, and returned briefly to the public eye in 1848 when he helped organise a military force to protect London during the year of European revolution.[91] The Conservative Party had split over the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, with Wellington and most of the former Cabinet still supporting Peel, but most of the MPs led by Lord Derby supporting a protectionist stance. Early in 1852 Wellington, by then very deaf, gave Derby's first government its nickname by shouting "Who? Who?" as the list of inexperienced Cabinet ministers was read out in the House of Lords.[92] He became Chief Ranger and Keeper of Hyde Park and St James's Park on 31 August 1850.[93] He remained colonel of the 33rd Regiment of Foot from 1 February 1806[94] and colonel of the Grenadier Guards from 22 January 1827.[95] Kitty died of cancer in 1831; despite their generally unhappy relations, which had led to an effective separation, Wellington was said to have been greatly saddened by her death, his one comfort being that after "half a lifetime together, they had come to understand each other at the end".[96] He had found consolation for his unhappy marriage in his warm friendship with the diarist Harriet Arbuthnot, wife of his colleague Charles Arbuthnot.[97] Harriet's death in the cholera epidemic of 1834 was almost as great a blow to Wellington as it was to her husband.[98] The two widowers spent their last years together at Apsley House.[99]

Death and funeral

Wellington died at Walmer Castle in Kent, his residence as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and reputedly his favourite home, on 14 September 1852. He was found to be unwell on that morning and was helped from his campaign bed, which he had used throughout his military career, and seated in his chair where he died. His death was recorded as being due to the after-effects of a stroke culminating in a series of seizures. He was aged 83.[100][79]

Although in life he hated travelling by rail, having witnessed the death of William Huskisson, one of the first railway accident casualties, his body was taken by train to London, where he was given a state funeral – one of a small number of British subjects to be so honoured (other examples include Lord Nelson and Sir Winston Churchill). The funeral took place on 18 November 1852.[101][102] Before the funeral, the Duke's body lay in state at the Royal Hospital Chelsea. Members of the royal family, including Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, the Prince of Wales, and the Princess Royal, visited to pay their respects. When viewing opened to the public, crowds thronged to visit and several people were killed in the crush.[103] Queen Victoria wrote: "He was the pride and the bon génie, as it were, of this country! He was the GREATEST man this country ever produced, and the most devoted and loyal subject, and the staunchest supporter the Crown ever had."[104]

He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral, and during his funeral, there was little space to stand due to the number of attendees.[105] A bronze memorial was sculpted by Alfred Stevens, and features two intricate supports: "Truth tearing the tongue out of the mouth of False-hood", and "Valour trampling Cowardice underfoot". Stevens did not live to see it placed in its home under one of the arches of the cathedral.[106]

Wellington's casket was decorated with banners which were made for his funeral procession. Originally, there was one from Prussia, which was removed during World War I and never reinstated.[107] In the procession, the "Great Banner" was carried by General Sir James Charles Chatterton of the 4th Dragoon Guards on the orders of Queen Victoria.[108]

Most of the book A Biographical Sketch of the Military and Political Career of the Late Duke of Wellington by Weymouth newspaper proprietor Joseph Drew is a detailed contemporary account of his death, lying in state and funeral.[109]

After his death, Irish and English newspapers disputed whether Wellington had been born an Irishman or an Englishman.[110] In 2002, he was number 15 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[111]

Owing to its links with Wellington, as the former commanding officer and colonel of the regiment, the title "33rd (The Duke of Wellington's) Regiment" was granted to the 33rd Regiment of Foot, on 18 June 1853 (the 38th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo) by Queen Victoria.[112] Wellington's battle record is exemplary; he participated in some 60 battles during the course of his military career.[113]

الألقاب والتكريم

الكنى

The "Iron Duke" related to Wellington's political, rather than to his military, career. Its use is often disparaging.[73][74][75] It is possible the term became more commonly used after 1832 when Wellington had metal shutters installed at Apsley House to prevent rioters breaking the windows.[80][114] The term may have been made increasingly popular by Punch cartoons published in 1844–45.[115][116]

In popular ballads of the day Wellington was called "Nosey" or "Old Nosey".[117] More complimentary sobriquets, including "The Beau" and "Beau Douro", referenced his noted dress sense.[118] Spanish troops called him "The Eagle", while Portuguese troops called him "Douro Douro" after his river crossing at Oporto in 1809.[119]

Napoleon dismissed his opponent as a "Sepoy General", a reference to Wellington's service in India. The name was used in the French newspaper Le Moniteur Universel, as a means of propaganda.[120] His allies were more enthusiastic; Tsar Alexander I of Russia calling him "Le vainqueur du vainqueur du monde", the conqueror of the world's conqueror, the phrase "the world's conqueror" referring to Napoleon.[121] Lord Tennyson uses a similar reference in his "Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington", referring to him as "the great World-victor's victor".[122] Similar tags included "Europe's Liberator"[123] and "Saviour of the Nations".[123]

الهامش

- ^ Gifford (1817), p. 375.

- ^ Bodart 1908, p. 789.

- ^ Wellesley (2008), p. 16.

- ^ Longford (1971), p. 53.

- ^ Severn (2007), p. 13.

- ^ Charles Robert S. Elvin (1890). Records of Walmer together with 'The Three Castles that keep the Downs'. Yale University Library. p. 241.

- ^ History of Parliament (2013).

- ^ Artware Fine Art (2020).

- ^ Guedalla (1997), p. 480.

- ^ Lloyd (1899), p. 170.

- ^ أ ب خطأ: الوظيفة "harvard_core" غير موجودة. "Dublin weekly and bi-weekly newspapers, however, which were published at the beginning of May, announced the birth of a son to the Countess of Mornington 'a few days ago' in Merrion Street, where, at No. 6, stood Mornington House. Despite Wellington's own inveterate distrust of newspapers, in this case they must be assumed to know best. At 6 Merrion Street (now 24 Upper Merrion Street) on 1 May 1769 the future Duke of Wellington was born."

- ^ Gash (2011).

- ^ "The Wesley and Wellsey Families". Essex, Herts and Kent Mercury. 13 Apr 1824. p. 4.

- ^ "Death of the Duke of Wellington". Sunday Dispatch. 1 Feb 1846. p. 10.

- ^ "Death of the Duke of Wellington". The Times. 15 September 1852. p. 5.

- ^ "Wellington Pillar, Wellington Place, Summerhill Road".

- ^ "Wellington Where Was He Born, Meath History Hub" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 Mar 2024.

- ^ خطأ: الوظيفة "harvard_core" غير موجودة. says "there is no valid argument" for this choice

- ^ Holmes (2002), pp. 6–7.

- ^ أ ب Holmes (2002), p. 8.

- ^ أ ب Holmes (2002), p. 9.

- ^ Holmes (2002), pp. 19–20.

- ^ أ ب Holmes (2002), p. 20.

- ^ أ ب ت Holmes (2002), p. 21.

- ^ "No. 12836". The London Gazette. 6 March 1787. p. 118.

- ^ "No. 12959". The London Gazette. 26 January 1788. p. 47.

- ^ أ ب Holmes (2002), p. 22.

- ^ "No. 12958". The London Gazette. 22 January 1788. p. 40.

- ^ "No. 13121". The London Gazette. 8 August 1789. p. 539.

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 23.

- ^ أ ب ت Holmes (2002), p. 24.

- ^ Duke of Wellington's Regiment (2006).

- ^ "No. 13347". The London Gazette. 27 September 1791. p. 542.

- ^ "No. 13488". The London Gazette. 25 December 1792. p. 976.

- ^ أ ب Holmes (2002), p. 25.

- ^ Number10 (2011).

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 26.

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 27.

- ^ "No. 13542". The London Gazette. 29 June 1793. p. 555.

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 28.

- ^ "No. 13596". The London Gazette. 23 November 1793. p. 1052.

- ^ Becke (1911), p. 380.

- ^ أ ب Siborne (1990), p. 439.

- ^ Summerville (2007), p. 315.

- ^ Hofschröer (1999), p. 117.

- ^ أ ب Hofschröer (1999), p. 122.

- ^ Chandler (1987), p. 373.

- ^ Adkin (2001), p. 361.

- ^ Becke (1911), p. 381.

- ^ أ ب ت Chesney (1907), pp. 178–179.

- ^ أ ب Parry (1900), p. 70.

- ^ Great Britain Foreign Office (1838), p. 280.

- ^ Cawthorne (2015), p. 90.

- ^ Adkin (2001), p. 49.

- ^ Moran (2010).

- ^ Bassford (2010).

- ^ Veve, Thomas Dwight (January 1990). "The Duke of Wellington and the army of occupation in France, 1815–1818". epublications.marquette.edu. Marquette University: 1–293. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "No. 17434". The London Gazette. 26 December 1818. p. 2325.

- ^ "No. 17525". The London Gazette. 16 October 1819. p. 1831.

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 268.

- ^ "No. 18327". The London Gazette. 23 January 1827. p. 153.

- ^ "No. 18335". The London Gazette. 13 February 1827. p. 340.

- ^ Holmes (2002), pp. 270–271.

- ^ "No. 18543". The London Gazette. 23 January 1829. p. 129.

- ^ Bloy (2011a).

- ^ Longford (1971), p. 174.

- ^ Hansard (1811).

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 277.

- ^ Thompson (1986), p. 95.

- ^ أ ب Holmes (2002), p. 275.

- ^ King's College London (2008).

- ^ Literary Gazette (1829).

- ^ أ ب Freeman's Journal (1830a): "Notes: If the Irish Question be lost, Ireland has her Representatives to accuse for it still more than the iron Duke and his worthy Chancellor"

- ^ أ ب Freeman's Journal (1830b): "Notes: "One fortnight will force the Iron Duke to abandon his project"

- ^ أ ب Freeman's Journal (1830c): "Notes: "Let the 'Iron Duke' abandon the destructive scheme of Goulburn."

- ^ Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine (1830).

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 281.

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 283.

- ^ أ ب Bloy (2011b).

- ^ أ ب Freeman's Journal (1832): "Notes: iron shutters are being fixed, of a strength and substance sufficient to resist a musket ball"

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 288.

- ^ Wellesley (1854), pp. 671–674.

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 289.

- ^ Holmes (2002), pp. 291–292.

- ^ "No. 20130". The London Gazette. 16 August 1842. p. 2217.

- ^ Davis (2003), pp. 43–55.

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 96.

- ^ Neillands (2003), p. 39.

- ^ BBC (2015).

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 206.

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 292.

- ^ Bloy (2011c).

- ^ "No. 21132". The London Gazette. 3 September 1850. p. 2396.

- ^ "No. 15885". The London Gazette. 28 January 1806. p. 128.

- ^ "No. 18327". The London Gazette. 23 January 1827. p. 154.

- ^ Longford (1971), p. 281.

- ^ Longford (1971), p. 95.

- ^ Longford (1971), p. 296.

- ^ Longford (1971), p. 297.

- ^ Corrigan (2006), p. 353.

- ^ The Times (1852a); also see خطأ: الوظيفة "harvard_core" غير موجودة.

- ^ "No. 21381". The London Gazette. 16 November 1852. p. 3079.

- ^ Walford (1878).

- ^ The Letters of Queen Victoria, a Selection from Her Majesty's Correspondence Between the Years 1837 and 1861. The University of Michigan. 1972. p. 478.

- ^ Holmes (2002), pp. 297–298.

- ^ Victoria and Albert Museum (2014).

- ^ Saint Paul's Cathedral (2011).

- ^ Dalton (1904), p. 77.

- ^ Drew (1852).

- ^ Sinnema (2006), p. 93–111.

- ^ Cooper & Boycott (2002), p. 13.

- ^ Duke of Wellington's Regiment (2014).

- ^ Roberts (2003b).

- ^ "BBC History". Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ R.E.Foster. "Mr Punch and the Iron Duke". Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Holmes (2002), pp. 285–288, 302–303.

- ^ Rory Muir (2013). Wellington: Waterloo and the fortunes of peace, 1814–1852. Yale University Press. p. 472. ISBN 978-0300187861.

- ^ Holmes (2002), p. 178.

- ^ Morgan (2004), p. 135.

- ^ Roberts (2003a), pp. 74, 78–79.

- ^ Cornwell, Bernard (2014). Waterloo – The History of Four Days, Three Armies and Three Battles. p. 10.

- ^ Alfred Lord Tennyson (1900). Tennyson: Including Lotos Eaters, Ulysses, Ode on the Death, Maud, The Coming and the Passing of Arthur. p. 10.

- ^ أ ب "Prime Ministers in History: Duke of Wellington". Prime Minister's Office. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

المصادر

- Beatson, Alexander. A collection of the Duke’s letters. A View of the Origin and Conduct of the War with Tippoo Sultaun. Bulmer and Co., 1800.

- Brett-James, ed. Wellington at War 1794-1815, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1961.

- Coates, Berwick, Wellington's Charge: A Portrait of the Duke's England, Robson Books Ltd, London, 2003

- Gates, David (1986), The Spanish Ulcer: A History of the Peninsular War, Pimlico (published 2002), ISBN 0-7126-9730-6

- Glover, Michael, The Peninsular War 1807 - 1814. London: Penguin Books, 2001 ISBN 0-141-39041-7 (first published 1974).

- Guedalla, Phillip, The Duke. London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1931.

- Hilbert, Charles. Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, time and conflicts in India on behalf of the British East India Company and the British crown. Military Heritage, August 2005, Volume 7, No. 1, pp. 34 to 41, ISSN 1524-8666.

- Holmes, Richard. Wellington: The Iron Duke. London: Harper Collins Publishers, 2002 ISBN 0-00-713750-8.

- Hutchinson, Lester. European Freebooters in Mogul India. New York: Asia Publishing House, 1964.

- Longford, Elizabeth. Wellington: The Years of The Sword. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1969.

- Montgomerie, Viva Seton (1955). My Scrapbook of Memories. Privately published. pp. 104.

- Neillands, Robert. Wellington and Napoleon - Clash of Armies. Pen and Sword Publishing, 2004.

- Mill, James. The History of British India. 6 vols. 5th ed. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1968.

- Gurwood, John. The dispatches of Field Marshall the Duke of Wellington : during his various campaigns in India, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, the Low Countries, and France, from 1799 to 1818. Volume X. London: J. Murray, 1838. Retrieved on 14 November 2007.

- Roberts, Andrew (2001). Napoleon and Wellington. Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

- Ward, S. G. P. (1957). Wellington's Headquarters - A Study of the Administrative Problems in the Peninsula 1809-1814. Oxford University Press.

وصلات خارجية

- ThePeerage.com

- Duke of Wellington Chronology World History Database

- Wellington's Military and Political Career

- Duke of Wellington's Regiment - West Riding

- أعمال من Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington في مشروع گوتنبرگ

- Images of political cartoons featuring the Duke of Wellington

- Duke of Wellington At Find A Grave

- More about Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington on the Downing Street website

- A Paper about the Duke of Wellington

- A comparison of Wellington and Eisenhower by Berwick Coates on geoset.info

| مناصب سياسية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه وليام إليوت |

Chief Secretary for Ireland 1807 - 1809 |

تبعه Robert Dundas |

| سبقه The Earl of Mulgrave |

Master-General of the Ordnance 1819 - 1827 |

تبعه The Marquess of Anglesey |

| سبقه The Viscount Goderich |

رئيس وزراء المملكة المتحدة 22 يناير 1828 – 16 نوفمبر 1830 |

تبعه The Earl Grey |

| زعيم مجلس اللوردات 1828 - 1830 | ||

| سبقه ڤايكونت ملبورن |

رئيس الوزراء (مؤقتاً) 17 نوفمبر 1834 – 10 ديسمبر 1834 |

تبعه السير روبرت پيل |

| سبقه Viscount Duncannon |

Home Secretary (pro tempore) 1834 |

تبعه Henry Goulburn |

| سبقه Thomas Spring Rice |

وزير الدولة للحربية والمستعمرات (pro tempore) 1834 |

تبعه The Earl of Aberdeen |

| سبقه ڤايكونت پالمرستون |

وزير الخارجية 1834 - 1835 |

تبعه ڤايكونت پالمرستون |

| سبقه ڤايكونت ملبورن |

زعيم مجلس اللوردات 1834 - 1835 |

تبعه ڤايكونت ملبورن |

| زعيم مجلس اللوردات 1841 - 1846 |

تبعه The Marquess of Lansdowne | |

| برلمان أيرلندا | ||

| سبقه Hon. William Wellesley-Pole John Pomeroy |

{{{title}}} 1790 - 1797 مع: John Pomeroy 1790–1791 Hon. Clotworthy Taylor 1791–1795 Hon. Henry Wellesley 1795 William Arthur Crosbie 1795–1797 |

تبعه Sir Chichester Fortescue William Arthur Crosbie |

| پرلمان المملكة المتحدة | ||

| سبقه Thomas Davis Lamb Sir Charles Talbot |

{{{title}}} 1806 مع: Sir Charles Talbot |

تبعه Patrick Crauford Bruce Michael Angelo Taylor |

| سبقه Samuel Boddington |

{{{title}}} May 1807 - July 1807 |

تبعه Evan Foulkes |

| سبقه Sir Christopher Hawkins Frederick William Trench |

{{{title}}} 1807 مع: Henry Conyngham Montgomery |

تبعه Edward Leveson-Gower George Galway Mills |

| سبقه Isaac Corry Sir John Doyle |

{{{title}}} 1807 - 1809 مع: The Viscount Palmerston |

تبعه The Viscount Palmerston Sir Leonard Thomas Worsley-Holmes |

| مناصب حزبية | ||

| First None recognised سبقه

|

Leader of the British Conservative Party 1828 - 1834 |

تبعه Sir Robert Peel, Bt |

| Conservative Leader in the Lords 1828 - 1846 |

تبعه The Lord Stanley | |

| مناصب دبلوماسية | ||

| شاغر اللقب آخر من حمله The Lord Whitworth of Newport Pratt

|

British Ambassador to France 1814 - 1815 |

تبعه Sir Charles Stuart |

| مناصب أكاديمية | ||

| سبقه Baron Grenville |

Chancellor of the University of Oxford 1834–1852 |

تبعه Earl of Derby |

| مناصب عسكرية | ||

| سبقه The Duke of Richmond |

Governor of Plymouth 1819 - 1827 |

تبعه The Earl Harcourt |

| سبقه HRH The Duke of York |

Commander-in-Chief of the Forces 1827 - 1828 |

تبعه The Lord Hill |

| سبقه The Viscount Hill |

Commander-in-Chief of the Forces 1842 - 1852 |

تبعه The Viscount Hardinge |

| ألقاب فخرية. | ||

| سبقه The Earl of Malmesbury |

Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire 1820 - 1852 |

تبعه The Marquess of Winchester |

| سبقه The Marquess of Hastings |

Constable of the Tower Lord Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets 1827 - 1852 |

تبعه The Viscount Combermere |

| سبقه The Earl of Liverpool |

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports 1829 - 1852 |

تبعه The Marquess of Dalhousie |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| منصب مستحدث | Baron Douro 1809 - 1852 |

تبعه آرثر ريتشارد ولسلي |

| ڤايكونت ولنگتن 1809 - 1852 | ||

| منصب مستحدث | إيرل ولنگتن 1812 - 1852 | |

| منصب مستحدث | ماركيز ولنگتن 1812 - 1852 | |

| منصب مستحدث | Marquess Douro 1814 - 1852 | |

| دوق ولنگتن 1814 - 1852 | ||

| ألقاب ملكية | ||

| منصب مستحدث | Conde de Vimeiro 1811 - 1852 |

تبعه آرثر ريتشارد ولسلي |

| منصب مستحدث | Marquês de Torres Vedras 1812 - 1852 | |

| منصب مستحدث | Duque da Vitória 1812 - 1852 | |

| نبيل إسپاني | ||

| سبقه لقب مستحدث |

Duque de Ciudad Rodrigo 1812 - 1852 |

تبعه آرثر ريتشارد ولسلي |

| نبالة هولندية | ||

| سبقه لقب مستحدث |

Prins van Waterloo 1815 - 1852 |

تبعه آرثر ريتشارد ولسلي |

قالب:Commander-in-Chief of the Forces

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- صفحات بها مخططات

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Pages using infobox officeholder with unknown parameters

- Articles containing OSM location maps

- مواليد 1769

- وفيات 1852

- Wellesley family

- مشيرون بريطانيون

- British military personnel of the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

- British Army personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars

- British Army commanders of the Napoleonic Wars

- رؤساء وزراء المملكة المتحدة

- وزراء دولة بريطانيون

- وزراء الدولة البريطانيون للشئون الخارجية

- Leaders of the British Conservative Party

- Members of the pre-1801 Parliament of Ireland

- Irish MPs 1790-1797

- Members of the United Kingdom Parliament for Irish constituencies (1801-1922)

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة عن دوائر إنگليزية

- أعضاء مجلس الخاصة لأيرلندا

- أعضاء مجلس الخاصة الملكية بالمملكة المتحدة

- UK MPs 1806-1807

- UK MPs 1807-1812

- Chancellors of the University of Oxford

- Old Etonians

- 73rd Regiment of Foot officers

- 33rd Regiment of Foot officers

- People associated with King's College London

- زملاء الجمعية الملكية

- Dukes in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

- Dukes of Wellington

- Princes of Waterloo

- فرسان الوبر الذهبي

- حائزو مرتبة الروح القدس

- فرسان الصليب الأعظم لنشان الحمام

- Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order

- Knights of St Patrick

- فرسان الوشاح

- Recipients of the Order of Saint George I Class

- Lord High Constables

- Lord-Lieutenants of Hampshire

- Lord-Lieutenants of the Tower Hamlets

- Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports

- مشيرون of Russia

- Knights of the Order of Saint Januarius

- أبناء غير أوائل لإرلات

- مبارزون بالمسدسات

- إنگليز-أيرلنديون

- Irish Anglicans

- Burials at St Paul's Cathedral

- Diplomatic peers

- أشخاص من مقاطعة دبلن

- Dutch nobility

- Regency era

- أشخاص صُوروا على الأوراق النقدية للاسترليني

- Grenadier Guards officers

- 18th-century Irish people

- 19th-century Irish people

- Dukes da Vitória

- صفحات مع الخرائط