مطرقة الساحرات

| Malleus Maleficarum | |

|---|---|

| Hammer of Witches | |

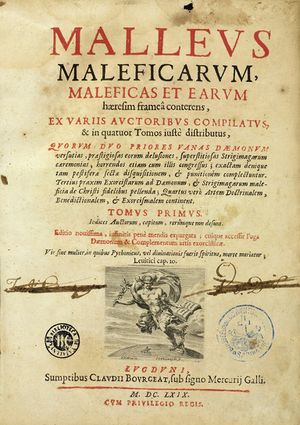

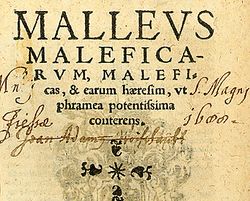

Title page of the seventh Cologne edition of the Malleus Maleficarum, 1520 (from the University of Sydney Library). The Latin title is "MALLEUS MALEFICARUM, Maleficas, & earum hæresim, ut phramea potentissima conterens." (generally translated into English as The Hammer of Witches which destroyeth Witches and their heresy as with a two-edged sword).[1] | |

| العنوان الكامل | Malleus Maleficarum |

| وتـُعرف أيضاً بإسم | مطرقة الساحرات |

| المؤلِف | هاينرش كرامر و ياكوب شپرنگر |

| اللغة | Latin |

| التاريخ | 1486 |

| تاريخ الإصدار | 1487 |

The Malleus Maleficarum,[2] usually translated as the Hammer of Witches,[3][أ] is the best known and the most important treatise on witchcraft.[6][7] It was written by the Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinized name Henricus Institoris) and first published in the German city of Speyer in 1487.[8] It endorses extermination of witches and for this purpose develops a detailed legal and theological theory.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15] It was a bestseller, second only to the Bible in terms of sales for almost 200 years.[16]

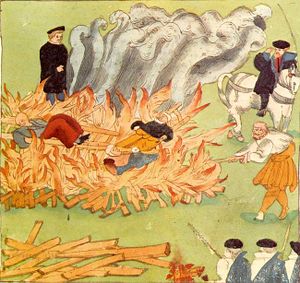

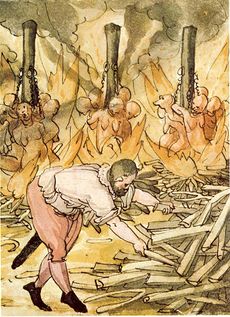

The Malleus elevates sorcery to the criminal status of heresy and prescribes inquisitorial practices for secular courts in order to extirpate witches. The recommended procedures include torture to effectively obtain confessions and the death penalty as the only sure remedy against the evils of witchcraft.[17][18] At that time, it was typical to burn heretics alive at the stake[19] and the Malleus encouraged the same treatment of witches. The book had a strong influence on culture for several centuries.[ب]

Jacob Sprenger's name was added as an author beginning in 1519, 33 years after the book's first publication and 24 years after Sprenger's death;[23] but the veracity of this late addition has been questioned by many historians for various reasons.

Kramer wrote the Malleus following his expulsion from Innsbruck by the local bishop, due to charges of illegal behavior against Kramer himself, and because of Kramer's obsession with the sexual habits of one of the accused, Helena Scheuberin, which led the other tribunal members to suspend the trial.[24]

It was later used by royal courts during the Renaissance, and contributed to the increasingly brutal prosecution of witchcraft during the 16th and 17th centuries.

خلفية

During the Age of Enlightenment, belief in the powers of witches to harm began to die out in the West. For the post-Enlightenment Christians, the disbelief was based on a belief in rationalism and empiricism.[26]

ملخص المحتويات

The Malleus Maleficarum consists of the following parts:[27]

- Justification (introduction, Latin Apologia auctoris)

- المرسوم الپاپوي

- Approbation by professors of theology at University of Cologne

- Table of contents

- Main text in three sections[27]

التبرير (Apologia auctoris)

النص الرئيسي

الأسس اللاهوتية والمواضيع الرئيسية

التعذيب والاعترافات

الضحايا

المفهوم المفصل للسحر

According to Mackay, this concept of sorcery is characterized by the conviction that those guilty engage in six activities:[28]

- الدخول في عقد مع الشيطان (والكفر بالمسيحية المصاحب لذلك),

- العلاقات الجنسية مع الشيطان،

- الطيران في الجو بغرض الاجتماع بأرواح شريرة;

- An assembly presided over by Satan himself (at which initiates entered into the pact, and incest and promiscuous sex were engaged in by the attendees),

- ممارسة السحر الضار،

- ذبح الرضع.[28]

علم العفاريت

انظر أيضاً

- General

- Witch-hunts

- Witch trials in the early modern period

- Witchcraft

- Rack (torture)

- European witchcraft

- Witchcraft and divination in the Bible

- Christian views on magic

- Strixology

- Torture of witches

- Discoverie of Witchcraft

- Salem witch trials

- People

المراجع

ملاحظات

- ^ Alternative translations: The Witch Hammer,[4] Hammer for Sorceresses ,[5] Hammer Against Witches, Hammer For Witches

- ^ Amongst the authors on witchcraft it had an ultimate authority[20] and even 17th century "Dominican chroniclers, such as Quétif and Échard, number Kramer and Sprenger among the glories and heroes of their Order".[21] The Malleus was ubiquitous, but at the end of the 16th century its role as a theoretical authority was superseded by Demonolatry by witch-hunter Nicholas Rémy and Magical Investigations by Jesuit Martin del Rio.[22]

الهامش

- ^ The English translation is from this note to Summers' 1928 introduction Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Translator Montague Summers consistently uses "the Malleus Maleficarum" (or simply "the Malleus") in his 1928 and 1948 introductions. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-07-18. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2007-06-01.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ In his translation of the Malleus Maleficarum, Christopher S. Mackay explains the terminology at length – sorcerer is used to preserve the relationship of the Latin terminology. '"Malefium" = act of sorcery (literally an act of 'evil-doing'), while "malefica" = female performers of sorcery (evil deeds) and "maleficus" = male performer of evil deeds; sorcery, sorceress, and sorcerer."

- ^ Guiley (2008), p. 223'.

- ^ Mackay (2009).

- ^ Mackay (2009), p. 1.

- ^ Summers (2012), p. vii, Introduction to 1948 edition: "It is hardly disputed that in the whole vast literature of witchcraft, the most prominent, the most important, the most authoritative volume is the Malleus Maleficarum" (The Witch Hammer) of Heinrich Kramer (Henricus Institioris) and James Sprenger."

- ^ Ruickbie (2004), 71, highlights the problems of dating; Ankarloo (2002), 239

- ^ Broedel (2003), p. 175: "Institoris and Sprenger's innovation was not their insistence that women were naturally prone to practice maleficium – in this they were simply following long-standing clerical traditions. Rather, it was their claim that harmful magic belonged exclusively to women that was new. If this assertion was granted, then the presence of maleficium indicated decisively the presence of a female witch. In the Malleus, the field of masculine magic is dramatically limited and male magicians are pointedly marginalized; magic is no longer seen as a range of practices, some of which might be more characteristic of men, some of women, and some equally prevalent among both sexes. Instead, it was the effects of magic that mattered most, and harmful magic, the magic most characteristic of witches, belonged to women. Men might be learned magicians, anomalous archer wizards, or witch-doctors and superstitiosi, but very seldom did they work the broad range of maleficium typical of witches."

- ^ Pavlac (2009), p. 57: "Many historians also blame Krämer for encouraging witch hunters to target women more than men as witches. Even his spelling of "maleficarum," with an a in a feminine gender instead of the usual masculine-gender "maleficorum" with an o, seems to emphasize his hostility toward women. Krämer's misogynistic arguments list many reasons why women were more likely to be witches than men. They were less clever, vainer, and more sexually insatiable. While these were not new criticisms against women, Krämer helped to entrench them in strixological literature."

- ^ Guiley (2008), p. 223: "Kramer in particular exhibited a virulent hatred toward women witches and advocated their extermination. The Malleus devotes an entire chapter to the sinful weakness of women, their lascivious nature, moral and intellectual inferiority and gullibility to guidance from deceiving spirits. In Kramer's view, women witches were out to harm all of Christendom.

Scholars have debated the reasons for Kramer's misogyny; he may have had a fear of the power of women mystics of his day, such as Catherine of Siena, who enjoyed the attentions of royalty as well as the church." - ^ Burns (2003), p. 160`: "One element distinguishing Malleus Maleficarum from other demonologies is its obsessive hatred of women and sex, which seems to reflect Kramer's own twisted psyche.

[...] Kramer's interpretation of why women were more likely to be witches also differed somewhat from the standard. Kramer did accept the standard argument of misogynist demonologists that the female propensity for witchcraft was in part due to female weakness. He even derived the Latin word for woman, femina, from fe minus — 'less in faith.' He placed more emphasis on supposedly insatiable female sexuality than on female weakness, however. Kramer saw sex as the root of all sin, as that for which Adam and Eve originally fell. [...] He also suspected that the reluctance of many great ones in the land to prosecute witches was caused by their reception of demonic sexual favors. Kramer also discussed witch-caused impotence at length, going so far as to claim that witches had the ability to steal men's penises through illusion." - ^ Brauner (2001), pp. 35–36: "Kramer and Sprenger present an array of observations from the Bible, the church fathers, and the poets and philosophers of antiquity to support their contention that women are by nature greedy, unintelligent, and governed by passions. They argue that the evil of women stems from their physical and mental imperfections, a notion derived from Aristotle's theory that matter, perfection, and spirituality are purely expressed in the male body alone, and that women are misbegotten males produced by defective sperm. Women speak the language of idiots, Aristotle contends; like slaves, they are incapable of governing themselves or developing into the 'zoon politicon'. Thomas Aquinas adapted these views to Christianity, arguing that because woman is less perfect than man, she is but an indirect image of God and an appendix to man. Citing such views, Kramer and Sprenger find that women are 'intellectually like children,' credulous and impressionable, and therefore easily fall prey to the devil. 'Since [women] are feebler both in mind and body,' the Malleus concludes, 'it is not surprising that they should come more [than men] under the spell of witchcraft.

Lack of intelligence prevents women not only from distinguishing good from evil, but from remembering the rules of behavior. Amoral and undisciplined, women are governed primarily by passion. 'And indeed,' Kramer and Sprenger declare, 'just as thorough the first defect in their intelligence women are more prone to abjure the faith; so through their second defect of inordinate affections and passions they search for, brood over, and inflict various vengeances, either by witchcraft, or by some other means.' [...] 'Wherefore it is no wonder that so great a number of witches exist in this sex,' concludes the Malleus." - ^ Britannica: "By 1435–50, the number of prosecutions had begun to rise sharply, and toward the end of the 15th century, two events stimulated the hunts: Pope Innocent VIII's publication in 1484 of the bull Summis desiderantes affectibus ("Desiring with the Greatest Ardour") condemning witchcraft as Satanism, the worst of all possible heresies, and the publication in 1486 of Heinrich Krämer and Jacob Sprenger's Malleus maleficarum ("The Hammer of Witches"), a learned but cruelly misogynist book blaming witchcraft chiefly on women. Widely influential, it was reprinted numerous times."

- ^ Levack (2006), p. 145: "Explanations for the predominance of women as witches often focus on the treatises written by demonologists, many of which comment on the fact that most witches were women. This literature is in most cases intensely misogynistic, in the sense that it is demeaning, if not blatantly hostile, to women. The common theme in these demonological treatises is that women were more susceptible to demonic temptation because they were morally weaker than men and more likely, therefore, to succumb to diabolical temptation. This idea, which dates from the earliest days of Christianity, is expressed most forcefully in the Malleus Maleficarum, but it can be found in many places, even in the sceptical demonological treatise of Johann Weyer."

- ^ Guiley (2008), p. 223``: "Published first in Germany in 1486, the Malleus Maleficarum proliferated into dozens of editions throughout Europe and England and had a profound impact on European witch trials for about 200 years. [...] It was second only to the Bible in sales until John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress was published in 1678"

- ^ Brauner (2001), pp. 33–34.

- ^ Broedel (2003), p. 33: "Ultimately, however, the bewitched cannot hope for an infallible remedy, for the power of witches is too strong. There is only one completely reliable way to combat witchcraft, and this is to eliminate the witches, the course of action Institoris and Sprenger endorse in one of the most impassioned passages of the Malleus [...]"

- ^ Mackay (2009), p. 28: "but it was understood by everyone that the heretic was to be executed (normally by being burned alive) in accordance with secular laws against heresy"

- ^ Summers (2012), p. xxxviii, Introduction to 1928 edition: "There can be no doubt that this work had in its day and for a full couple of centuries an enormous influence. There are few demonologists and writers upon witchcraft who do not refer to its pages as an ultimate authority."

- ^ Summers (2012), p. ix, Introduction to 1948 edition: "The Dominican chroniclers, such as Quétif and Échard, number Kramer and Sprenger among the glories and heroes of their Order"

- ^ Burns (2003), p. 160: "In the Catholic world, the works of Nicholas Remy and Martin del Rio replaced the Malleus as a theoretical authority in the late sixteenth century. Its ubiquity, however, must have made it an important contributor to the ideas that many educated people held of witches and the proper way to deal with them.

- ^ Behringer, Wolfgang. Malleus Maleficarum, p. 2.

- ^ Burns, William. Witch Hunts in Europe and America: An Encyclopedia, pp. 143-144.

- ^ K.M. Sheard (2011), "Hypatia", Llewellyn's Complete Book of Names for Pagans, Wiccans, Witches, Druids, Heathens, Mages, Shamans & Independent Thinkers of All Sorts who are Curious about Names from Every Place and Every Time, pp. 285–86, ISBN 9780738723686

- ^ Hayes (1995), pp. 339–354.

- ^ أ ب Mackay (2009), p. 12.

- ^ أ ب Mackay (2009), p. 19.

ببليوگرافيا

- المصادر الثانوية

- Mackay, Christopher S. (2009). The Hammer of Witches: A Complete Translation of the Malleus Maleficarum (1 volume). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-53982-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (إنگليزية) - Mackay, Christopher S. (2006). Malleus Maleficarum (2 volumes). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85977-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (Latin) (إنگليزية) - Broedel, Hans Peter (2003). The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft: Theology and Popular Belief. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719064418.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Summers, Montague (2012). The Malleus Maleficarum of Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger. Courier Corporation.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Halsall, Paul, ed. (1996). "Witchcraft Documents [15th Century]". Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Fordham University Center for Medieval Studies.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

- مصادر الدرجة الثالثة

- Hayes, Stephen (1995). "Christian responses to witchcraft and sorcery". Missionalia. 23 (3).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Guiley, Rosemary (2008). The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca. Checkmark Books.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Levack, Brian P. (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Levack, Brian P. (2006). The Witch-hunt in Early Modern Europe. Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 0-5824-1901-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Malleus maleficarum". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Witchcraft". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Burns, William (2003). Witch Hunts in Europe and America: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood. ISBN 0-3133-2142-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jolly, Karen; Peters, Edward; Raudvere, Catharina (2001). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, Volume 3: The Middle Ages (History of Witchcraft and Magic in Europe). Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 0-4858-9103-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brauner, Sigrid (2001). Fearless Wives and Frightened Shrews: The Construction of the Witch in Early Modern Germany. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-5584-9297-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ankarloo, Bengt; Clark, Stuart, eds. (2002). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, Volume 3: The Middle Ages. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1786-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ankarloo, Bengt; Clark, Stuart, eds. (2002). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe Volume 4. The Period of the Witch Trials. The Athlone Press London. ISBN 0-485-89104-2.

- Bailey, Michael D. (2003). Battling Demons: Witchcraft, Heresy, and Reform in the Late Middle Ages. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-02226-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Henningsen, Gustav (1980). The Witches' Advocate: Basque Witchcraft and the Spanish Inquisition. University of Nevada Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kieckhefer, Richard (2000). Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Maxwell-Stewart, P. G. (2001). Witchcraft in Europe and the New World. Palgrave.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pavlac, Brian (2009). Witch Hunts in the Western World: Persecution and Punishment from the Inquisition through the Salem Trials: Persecution and Punishment from the Inquisition through the Salem Trials. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313348747.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Trevor-Roper, H. R. (1969). The European Witch-Craze: of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries and Other Essays. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-131416-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas, Keith (1971). Religion and the Decline of Magic – Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century England. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013744-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Robbins, Rossell Hope (1959). The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology. Peter Nevill.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

للاستزادة

- Flint, Valerie. The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ. 1991

- Hamilton, Alastair (May 2007). "Review of Malleus Maleficarum edited and translated by Christopher S. Mackay and two other books". Heythrop Journal. 48 (3): 477–479. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2265.2007.00325_12.x.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|quotes=(help)

(payment required) - Institoris, Heinrich; Jakob Sprenger (1520). Malleus maleficarum, maleficas, & earum haeresim, ut phramea potentissima conterens. Excudebat Ioannes Gymnicus.

- This is the edition held by the University of Sydney Library. [1]

- Ruickbie, Leo (2004). Witchcraft Out of the Shadows. Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-7567-7.

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1972). Witchcraft in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9289-0.

- Summers, Montague (1948). The Malleus Maleficarum of Kramer and Sprenger. ed. and trans. by Summers. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-22802-9.

- Thurston, Robert W. (November 2006). "The world, the flesh and the devil". History Today. 56 (11): 51–57.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|quotes=(help) (payment required for full text)

وصلات خارجية

- U.S. National Library of Medicine, Digital Collections: Malleus Maleficarum – online scan of a Latin version presumably published in 1494.

- Malleus Maleficarum – Online version of Latin text and scanned pages of Malleus Maleficarum published in 1580.

- Malleus Maleficarum – Online and downloadable scan of original Latin edition of 1490.

- English translation

- Malleus Maleficarum Online (Latin) (بالألمانية)

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).