لوتيتيا

حمامات كلوني | |

| الاسم البديل | Lutetia Parisorum (Latin), Lutèce (French) |

|---|---|

| المكان | Paris, France |

| المنطقة | Gallia Lugdunensis, later Lugdunensis Senonia |

| الإحداثيات | 48°51′17″N 2°20′51″E / 48.85472°N 2.34750°E |

| النوع | oppidum, later civitas |

| المساحة | 284 acre (115 ha)[1] |

| التاريخ | |

| تأسس | ح. 3rd century BC as a oppidum, refounded as civitas in 52 BC |

| الفترات | 1st century BC to 5th century |

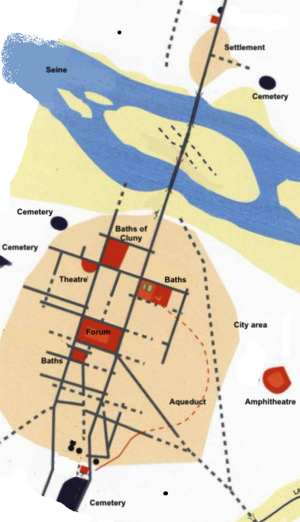

Lutetia, (UK: /luːˈtiːʃə/ loo-TEESH-ə, also US: /luˈtiʃə/;[2] لاتينية: [luːˈteːtia]; فرنسية: Lutèce [lytɛz]) also known as Lutetia Parisiorum (/ ... pəˌrɪzɪˈɔːrəm/ pə-RIZ-i-OR-əm;[2] لاتينية: [... pariːsiˈoːrʊ̃ː]; حرفياً 'Lutetia of the Parisii'), was a Gallo–Roman town and the predecessor of modern-day Paris.[3] Traces of an earlier Neolithic settlement (ح. 4500 BC) have been found nearby, and a larger settlement was established around the middle of the 3rd century BC by the Parisii, a Gallic tribe. The site was an important crossing point of the Seine, the intersection of land and water trade routes.

In the 1st century BC, the settlement was conquered by Romans and a city began to be built. Remains of the Roman forum, amphitheatre, aqueduct and baths can still be seen. In the 5th century it became the capital of the Merovingian dynasty of French kings, and thereafter was known as Paris.

Many artifacts from Lutetia have been recovered and are on display at the Musée Carnavalet.

أصل الاسم

The settlement is attested in Ancient Greek as Loukotokía (Λoυκoτοκία) by Strabo and Leukotekía (Λευκοτεκία) by Ptolemy.[4] Likely origins are Celtic root lut- meaning "a swamp or marsh" + suffix -ecia,[5] It survives today in the Scottish Gaelic lòn ("pool, meadow") and the Breton loudour ("dirty").[6]

A less likely origin is the Celtic root *luco-t-, which means "mouse" and -ek(t)ia, double collectiv suffix, meaning "the mice" and which is contained in the Breton word logod, the Welsh llygod "mice", and the Irish luch, genitiv luchad "mouse".[4][6]

التاريخ

أقدم سكان

Traces of Neolithic habitations, dating as far back as 4500 BC, have been found along the Seine at Bercy, and close to the Louvre. The earliest inhabitants lived on the river plain, raising animals and farming. In the Bronze Age and Iron Age, they settled in villages, in houses made of wood and clay. Their life was closely attached to the river, which served as a trade route to other parts of Europe.[7]

المستوطنة الغالية

The original location of the early capital of the Parisii is still disputed by historians. Traditionally, they had placed the settlement on the Île de la Cité, where the bridges of the major trading routes of the Parisii crossed the Seine. This view was challenged after the discovery between 1994 and 2005 of a large early Gallic settlement in Nanterre, in the suburbs of Paris. This is composed of a large area of several main streets and hundreds of houses over 15 hectares. Critics also point out the lack of archaeological finds from the pre-Roman era on the Ile de la Cité.[8]

Other scholars dispute the idea that the settlement was in Nanterre. They point to the description given by Julius Caesar, who came to Lutetia to negotiate with the leaders of the Gallic tribes. He wrote that the oppidum which he visited was on an island. In his account of the war in Gaul[9] Caesar wrote that, when the Romans later laid siege to Lutetia, "the inhabitants had burned their structures and the wooden bridges which served to cross the two branches of the river around their island fortress," which appears to describe the Île de la Cité.[10]

Proponents of the Ile de Cité as the site of the Gallic settlement also address the issue of the lack of archaeological evidence on the island. The original oppidum and bridges were burned by the Parisii to keep them out of the hands of the Romans. The houses of the Parisii were made of wood and clay. Since then every square metre of the island has been dug up and rebuilt, often using the same materials, multiple times, making it unlikely that traces of the Gallic settlement would remain on the island. They argue that a settlement in Nanterre did not necessarily exclude that the Île-de-la-Cité was the site of the oppidum of Lutetia; both settlements could have existed at the same time. Finally, they argue that, while Gallic settlements sometimes relocated to a new site, the new sites were usually given a new name. It would be very unusual to transfer the name of Lutetia from the Nanterre settlement to a new Roman town on the Île-de-la-Cité. They also argue that if Lutetia had not already existed where Paris is today, the new Roman city would have been given a Latin, not a Gallic name. This seems to support the argument that Lutetia was in fact located at the center of modern Paris.[7][11]

The Parisii first agreed to submit to Caesar and Rome, but in 52 BC they joined other tribes, led by Vercingetorix, in a revolt near the end of Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars, the Battle of Lutetia was fought with the local tribe.[12] The Gallic forces were led by Vercingetorix's lieutenant Camulogenus. They burned the oppidum and the bridges to keep the Romans from crossing. The Romans, led by Titus Labienus, one of Caesar's generals, marched south to Melun, crossed the river there, marched back toward the city, and decisively defeated the Parisii. The location of the final battle, like the location of the oppidum, is disputed. It was fought near a river, which some historians interpret as the Seine, and others as the Yonne; and near a large marsh; a feature of the countryside near both the Île-de-la-Cité and Narbonne. Whatever its location was, the battle was decisive; Lutetia became a Roman town.[10][11]

لوتيشيا الرومانية

The first traces of the Roman occupation of Lutetia appeared at the end of the 1st century BC, during the reign of the Emperor Augustus. By the beginning of the 1st century AD, the construction of the Roman city was underway.[13]

The Roman city was laid out along the main Cardo Maximus street, perpendicular to the Seine. It began at the heights of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève on the left bank, went downhill along the modern Rue Saint-Jacques, across a marshy area to the bridge connecting to the Île de la Cité; across the island, and across a bridge to a smaller enclave on the right bank. The low-lying land along the river was suitable for farming;[14] and since it was easily flooded, the road was raised.[15] The Cardo Maximus met the Decumanus, or main east-west street, located at modern rue Soufflot. Here was the civic basilica, containing a tribunal, and a temple. Gradually the city was furnished with a forum, and baths, all on the upper slope of Mount Sainte-Genevieve.[16]

It was not the capital of the Roman province (Sens had that distinction) and it was to the west of the most important Roman north-south road between Provence and the Rhine. The importance of the city was due in large part to its position as an intersection of land and water trade routes. One of the most striking archeological finds from the early period is the Pillar of the Boatmen which was erected by the corporation of local river merchants and sailors and dedicated to Tiberius.[17][14]

Other major public works projects and monuments were built in the 2nd century AD including an aqueduct.[18]

In the 3rd century, according to legend, Christianity was brought to the town by St Denis, and his companions Rusticus and Eleuthere.[بحاجة لمصدر] In about 250 he and two companions were said to have been arrested and decapitated on the hill of Mons Mercurius thereafter known as Mons Martyrum (Martyrs' Hill, or Montmartre). According to tradition, he carried his head to Saint-Denis, where the Basilica of Saint-Denis was later built.

The mid third century brought a series of invasions of Gaul by two Germanic peoples, the Franks and the Alemanni, which threatened Lutetia. The city at the time had no fortifications. Portions of the left bank settlement, including the baths and amphitheatre, were hurriedly abandoned, and the stones used to construct ramparts around the Île de la Cité. The city was reduced in size from one hundred hectares during the high Roman Empire to ten to fifteen hectares on the left bank, and ten hectares on the Île de la Cité.[19] A new civic basilica and baths were built on the island whose vestiges can be seen in the archeological crypt under the Parvis in front of Notre-Dame Cathedral, Place John Paul II.[15] [19]

In the 4th century, Lutetia remained an important bulwark defending the Empire against the Germanic invaders. In 357–358 Julian II, as Caesar of the Western empire and general of the Gallic legions, moved the Roman capital of Gaul from Trier to Paris. After defeating the Franks in a major battle at Strasbourg in 357, he defended against Germanic invaders coming from the north. He was proclaimed emperor by his troops in 360 in Lutetia. Later Valentinian I resided in Lutetia for a brief period (365–366).[20] The first documented bishop of Paris was Victorinus, in 346.[بحاجة لمصدر] The first council of Bishops in Gaul convened in the city in 360. When Saint Martin visited the city in 360, there was a cathedral, near the site of Notre-Dame de Paris.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The end of the Roman Empire in the west, and the creation of the Merovingian dynasty in the 5th century, with its capital placed in Paris by Clovis I, confirmed the new role and name for the city. The adjective Parisiacus had already been used for centuries. Lutetia had gradually become Paris, the city of the Parisii.[21]

Sculpture of a Triton and a Nymph (2nd century AD) found on the Île de la Cité (Musée Carnavalet)

Interior of the Roman baths, (Hotel de Cluny)

المدينة

فورم لوتيشيا

The Forum of Lutetia was in the centre of the city, between the modern streets of Boulevard Saint-Michel on the west, Rue Saint-Jacques on the east, rue Cujas to the north and Rue G. Lussac and rue Malbranch to the south. It was two Roman blocks wide and one block long, 177.6 x 88.8 m.[22] Only a small part of a wall of the old forum remains above ground today, but the foundations have been extensively excavated since the 19th century.

The forum was surrounded by a wall, with entrances on the north and south. Along the outer walls on the north, south sides and west sides, were arcades sheltering rows of small shops. At the west end was an underground gallery, or cryptoporticus.[23]

The civic basilica, essentially the town hall, occupied the east of the forum, It contained the courts where political, social and financial issues were discussed and decided. It had a central nave, higher than other parts of the building, and two lower collateral aisles, separated from the nave by rows of columns.[22]

At the west end was the temple devoted to the official gods. Its facade with a portico of pillars with triangular pediment faced to the east, the tradition for Roman temples.[22][23]

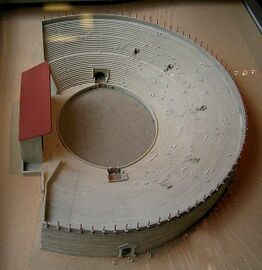

المسرح المفتوح أو ملعب لوتيز

The amphitheatre is located near the intersection of Rue Monge and Rue de Navarre. It was about 100 x 130 m in plan, making it one of the largest in Gaul. It could accommodate as many as 17000 spectators.[بحاجة لمصدر]

It had a stage and backdrop used for the presentation of plays, along with a larger space suitable for the combat of gladiators and of animals, and other large-scale festivities. It was probably built near the end of the 1st century AD. In the early 4th century its stone was used in the construction of the fortress on the Île de a Cité, at a time when the province was threatened by barbarian invasion.

Many of the remaining stones were reused in another major project, the city wall of Paris constructed by Philippe-Auguste in the 12th century.[24]

The site was discovered in 1867-68 during the construction of Rue Monge by Louis-Napoleon, and excavations were begun in 1870.[24][25] A bus depot was planned to be built on the same site, but a coalition of notable Parisans, including Victor Hugo, insisted that the vestiges be saved. They were declared a monument, and partially rebuilt beginning in 1915-16.

المسرح

The Roman theatre of Lutetia was located where the Lycée Saint-Louis is today, along Boulevard Saint-Michel. It occupied one of the central blocks of the Roman city, three hundred Roman feet on each side. It was probably built in the second part of the 1st century AD, based on coins found; it was renovated in the 2nd century. Like many other buildings on the left bank in the 4th century its stone was used in the building of the wall and new buildings on the Île-de-la-Cité. It was excavated and recreated by Theodore Vacquer between 1861 and 1884.[26]

The slope of Mt. Genevieve was used to provide elevation for the semi-circular seating.[26] The back of the stage faced onto to the Roman road and was decorated with arches and columns. The "pulpitum", or front stage, and "parascenum", or back stage, rested on a base of cement. When excavated in the 19th century, the chalk builders' marks were still visible on the floor.[26]

The theatre had two groups of seating; the maenianum, or general audience seating, higher up and farther back, and the "maenianum" of the podium, for the notables, in front of the orchestra stage. It had a separate entrance, and was accessed by a covered corridor. There were also several vomitoria, or underground passageways, to the seats of the spectators. The arena probably had some form of covering over the seats to protect spectators from rain.[26]

الحمامات

The Thermes de Cluny, the grand public baths, now part of the Musée de Cluny, are the largest and best-preserved vestige of Roman Lutetia and date from the late 1st or early 2nd century AD. They were at the junction of the two major Roman roads, between Boulevard Saint-Michel, Boulevard Saint-Germaine, and the Rue des Ecoles.[27] The baths originally occupied a much larger area of about 300 x 400 Roman feet, a standard Roman city block, covering about one hectare.[28][29]

Clients entered the baths near the modern Rue des Ecoles into a large courtyard lined with shops. They would cross the courtyard to the entrance of the baths, change their clothes, and go first into the caldarium, a hot and steamy room with benches and a pool of heated water. The room was heated by a hypocaust, an under-floor system of tunnels filled with hot air, heated by furnaces tended by slaves. After a period of time there, bathers would move to the frigidarium, which had a cold-water pool and baths, or to the tepidarium, which had the same features at room-temperature. They played an important social and political role in Lutetia as in other Roman cities. They were free of charge, or accessible for a small fee, and contained not only baths but also bars, places to rest, meeting rooms and libraries.[29]

The original baths were probably destroyed during the first invasion by the Franks and Alamans in 275, then rebuilt. The frigidarium, with its vault intact, and the caldarium are the main remaining rooms. They were originally covered on the inside with mosaics, marble or frescoes. The northern side was occupied by two gymnasia and at the centre of the facade was a monumental fountain. Beneath there are several lower rooms with vaulted roofs. The drain for emptying the frigidarium pool is still visible that encircled the baths and ran into a main drain located under Boulevard Saint-Michel.[27]

Remains of other baths have been discovered. The best-preserved were found in the 19th century within the present College de France on the "Cardo" or rue Saint-Jacques. They were of about two hectares, even larger than Cluny, and included a Palaestra, or large outdoor exercise area. Vestiges of the circular hot water pool and the cold water pool have survived, along with the hypocaust heating system. Traces were also found of marble wall coverings, frescoes and bronze fixtures.[30]

Others were found in rue Gay-Lussac and on the Ile de la Cite.

Model of Thermes de Cluny: In the centre is the frigidarium, left the tepidarium, right the caldarium.

The Caldarium, or hot baths, of Cluny

Bath in the Frigidarium, or Cold bath

الشوارع

The streets and squares were laid out in blocks ("insular") of 300 Roman feet (88.8 m) square. As a result the modern Rue Saint Martin and Rue Saint-Denis, which were both laid out in Roman times, are 600 Roman feet apart.[31] Excavations of the streets have uncovered the ruts in the roads from the wheels of chariots and wagons. The roads were regularly repaired with fresh stones, gradually raising their height by as much as a metre.[32]

المساكن

The residential streets of Lutetia, unlike the boulevards, were irregular and not as-well maintained as they were the responsibility of the home-owners, not the city. Traces of several of these early residential neighbourhoods, dating to the beginning of the 1st century AD, particularly on the Rue de l'Abbé de l'Épée, rue Pierre-et-Marie-Curie, and the garden of the Êcole des Mines have been discovered.[33]

The houses generally had wood frames covered with clay. The floors were covered with yellow clay or packed earth. Excavations showed that the city had an important plaster industry; plaster was used to simulate stone, as a covering, or in the form of bricks and tiles.[34]

The houses of the wealthy often had an underfloor heating system and their own bath suite. Their interior walls were covered with plaster, and often painted with frescoes, some traces of which have been recovered (see gallery). They frequently had a reception room on the ground floor and bedrooms upstairs, accessed by a stairway, as well as a cellar which sometimes had its own well. Several houses were grouped together with a common courtyard. [33]

In May 2006, a Roman road was found during expansion of the University of Pierre and Marie Curie campus. Additionally, remains of private houses dating from the reign of Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD) containing heated floors were found. The owners were wealthy enough to own baths which was a status symbol among Roman citizens.

A bronze key from Lutetia (Musée Carnavalet)

Objects from daily life in Lutetia found in the Musée Carnavalet

Remains of a decorative mural from 12, rue de l'Abbé-de-l'Épée, (2nd century AD} (Musée Carnavalet)

Detail of a fresco of a bird, 14, rue Monsieur-le-Prince, Musée Carnavalet)

Aqueduct

The source of the aqueduct was in the hills outside the city at Rungis and Wissou in the present department of the Essonne where a collection tank was excavated. The aqueduct was built in the second half of the 1st century AD mainly to supply the monumental public baths of Cluny. The aqueduct could deliver an estimated 2000 m3 of water a day.[بحاجة لمصدر] The masonry and cement conduit, about 1/2 metre wide and 3/4 metre deep, was mainly below ground level over the distance of 26 kilometres to the city. The major obstacle it faced was crossing the valley of the river Biévre where the conduit was raised on arches, some of which still exist in the Valley of Arcueil-Cachan.

Vestiges of the aqueduct have been discovered in several places including under the Institute Curie.[35]

إيل دلا سيتيه

Beginning in 307 AD, the increasing number of invasions of Gaul by Germanic tribes forced the Lutetians to abandon a large part of the city on the left bank, and to move to the Île de la Cité.

Vestiges of Roman buildings on the island, including baths, were found under the parvis of Notre-Dame in 1965 and can be seen today. The rampart was about two metres tall with a wooden walkway and, like most of the buildings on the island, was built from stone brought from the demolished buildings on the left bank.[36]

A modest headquarters or "Palace" was constructed at the west end of the island, where the Palais de Justice is today. One was the residence and headquarters of the Roman military commander, and the temporary residence of two Emperors during the military campaigns. It was probably here that Julian was proclaimed emperor by his troops in 361.

Another important building on the island was the civic basilica, fulfilling the judicial functions transferred from the Left Bank. It stood between the modern Rue de la Cité and the Tribunal de Commerce, near where the flower market is today. It was discovered in 1906 during the construction of the Paris Metro station. It was 70 x 35 m with a central nave. The entrance was probably on the Rue de la Cité, the Cardo Maximus which crossed the island and connected the bridges.

Ruins of the Roman baths under the Parvis Notre-Dame – Place Jean-Paul-II

A coin depicting Julian (360–363), made Emperor by his soldiers in Lutetia

Steps to the wharf of the Roman port, now 50 m from the river.(Parvis Notre-Dame – Place Jean-Paul-II)

المقابر

During the early, or High Roman Empire, the major Roman necropolis, or cemetery, was located near the Cardo Maximus (Main Street), close to the exit of the city and some distance from the nearest residences. The Necropolis of Saint-Jacques was close to the modern intersection of Avenue Saint-Michel and Avenue Denfert-Rochereau. It occupied a space of about four hectares, and was in use from the beginning of the first until about the fourth century AD. About four hundred tombs, a fraction of the tombs that were once there, have been excavated. Tombs were often placed one above the other. Some remains were buried in stone sepulchres, others in wooden coffins, others simply in the ground. It was a common practice to bury the dead with some items of their belongings, usually some of their clothing and particularly their shoes, placed in vases. Sometimes items of food and silverware were placed in the burial vessel. [37]

In the later years of the Empire, when the pressure of invading Germanic tribes led to the abandonment of the old monuments, a new necropolis, named for Saint-Marcel, was established near the modern Avenue des Gobelins and Boulevard du Port Royal, along the Roman main road leading to Italy. In this necropolis the tombs were mostly composed of stone taken from the monuments in the earlier necropolis of Saint-Jacques. One of the tombs there, dating from the Third Century AD, is notable for the first recorded use of the name "Paris" for the city. The tombs at Saint Marcel contain a variety of ceramic and glass objects from the workshops of the city, placed at the foot of the deceased. The first symbols of Christian burials, in the 5th century, were also found here.[38]

الفن والديكور

Lutetia was both a trading centre for art works, through its access to water and land routes, and, later, the home of workshops ceramics and other decorative works.[بحاجة لمصدر] Sculpture was widely used in monuments, particularly in the several necropoli, or Roman cemeteries, in the outskirts of the city.

The Pillar of the Boatmen was donated to the city in about 14-17 AD (dedicated to the Emperor Tiberius) by the guild of boatmen, the most influential guild in the city, and was found in the Île-de-la-Cité. It depicted both Roman and Gallic deities in a series of blocks stacked into a column.[35]

Jupiter holding a lightning bolt, on the Pillar of the Boatmen (1st century AD)

A stele of the god Mercury, found under the Hotel Dieu on the Île-de-la-Cité (Carnavalet Museum)

الذكرى

Several scientific discoveries have been named after Lutetia. The element lutetium was named in honor of its discovery in a Paris laboratory, and the characteristic building material of the city of Paris,Lutetian Limestone, derives from the ancient name. The "Lutetian" is, in the geologic timescale, a stage or age in the Eocene Epoch. The asteroid 21 Lutetia, discovered in 1852 by Hermann Goldschmidt, is named after the city.

Lutetia is featured in the French comic series The Adventures of Asterix, most notably in Asterix and the Golden Sickle, Asterix and the Banquet and Asterix and the Laurel Wreath.

Renault uses the name Lutecia for the Japanese market Clio subcompact car, and is named after Lutetia.

انظر أيضاً

- تاريخ پاريس

- The Aqueduct[39] (French)

المراجع

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (2019). The Seine: The River that Made Paris. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-60936-3.

- ^ أ ب "Lutetia". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 2023-02-14.

- ^ Guillaume, Valerie, "Musee Carnavalet-Histoire de Paris - Guide de Visite" (2021), p. 22-27

- ^ أ ب La langue gauloise, Pierre-Yves Lambert, éditions errance 1994.

- ^ Albert Dauzat et Charles Rostaing, Dictionnaire étymologique des noms de lieux en France, éditions Larousse 1968.

- ^ أ ب Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise, Xavier Delamarre, éditions errance 2003, p. 209

- ^ أ ب "The first inhabitants | Paris antique". archeologie.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved Nov 26, 2022.

- ^ Nanterre et les Parisii : Une capitale au temps des Gaulois ?, Antide Viand, ISBN 978-2-7572-0162-6

- ^ De Bello Gallico

- ^ أ ب Sarmant, "History of Paris" (2012), p. 10

- ^ أ ب Busson 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Julius Caesar: De Bello Gallico, book six, VI p. 62

- ^ Busson 2001, p. 32-33.

- ^ أ ب "Paris, a Roman city". www.paris.culture.fr.

- ^ أ ب "The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, LUTETIA PARISIORUM later PARISIUS (Paris) France". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved Nov 26, 2022.

- ^ Sarmant 2012, p. 12.

- ^ Busson (2001), p. 154.

- ^ 2 Roman and Medieval Paris, Clifton Ellis, PhD Architectural History, Texas Tech College of Architecture - TTU College of Architecture

- ^ أ ب Sarmant 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Goudineau, Christian, "Lutetia" in Dictionary of Antiquity under the direction of Jean Leclant. PUF. 2005

- ^ The City of Antiquity Archived 2008-12-12 at the Wayback Machine, official history of Paris by The Paris Convention and Visitors Bureau

- ^ أ ب ت Busson 2001, p. 64-66.

- ^ أ ب "The forum | Paris antique". archeologie.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved Nov 26, 2022.

- ^ أ ب Busson 1989, pp. 80-89.

- ^ "The theatre | Paris antique". archeologie.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved Nov 26, 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Busson 2001, p. 94-97.

- ^ أ ب Alain Bouet and Florence Saragoza, "Les Thermes de Cluny", the Archeologia files, no. 323, p. 25

- ^ Busson, p. 106.

- ^ أ ب "Paris, "a Roman city" (in English) French Ministry of Culture site". archeologie.culture.fr. Retrieved Nov 26, 2022.

- ^ Busson 1989, pp. 102-105.

- ^ Busson 2001, p. 40.

- ^ Busson 2001, p. 45.

- ^ أ ب Busson 1980, p. 47-49.

- ^ "Plaster production | Paris antique". archeologie.culture.fr. Retrieved Nov 26, 2022.

- ^ أ ب Busson 1989, p. 98-100.

- ^ Busson 1989, p. 132-133.

- ^ Busson 1989, p. 120-131.

- ^ Busson 1989, p. 18-129.

- ^ "Roman aqueducts: Paris (country)". www.romanaqueducts.info.

ببليوگرافيا (بالفرنسية)

- Busson, Didier (2001). Paris ville antique (in الفرنسية). Monum- Éditions du Patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-85822-368-8.

- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-07862-4.

- Sarmant, Thierry (2012). Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilisation. Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-7558-0330-3.

- Guillaume, Valérie, Musée Carnavalet - Histoire de Paris - Guide de visite, July 2021, Éditions Paris Musées, Paris, (in French) (ISBN 978-2-7596-0474-6)

- Schmidt, Joel (2009). Lutece- Paris, des origines a Clovis. Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-03015-5.

- Philippe de Carbonnières, Lutèce: Paris ville romaine, collection Découvertes Gallimard (no. 330), série Archéologie. Éditions Gallimard, 1997, ISBN 2-07-053389-1.

وصلات خارجية

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages with plain IPA

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Archaeological sites in France

- Celtic towns

- Populated places in pre-Roman Gaul

- Roman Paris

- Roman towns and cities in France