اللاتينية القديمة

| Old Latin | |

|---|---|

| Archaic Latin | |

| Prisca Latinitas | |

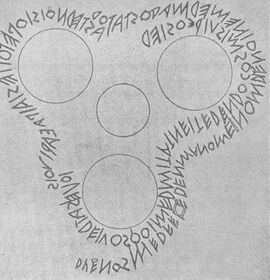

Duenos inscription، أحد أقدم نصوص اللاتينية القديمة | |

| موطنها | الجمهورية الرومانية |

| المنطقة | إيطاليا |

| الحقبة | Developed into Classical Latin during the 1st century BC |

| Latin alphabet | |

| الوضع الرسمي | |

لغة رسمية في | روما |

| ينظمها | Schools of grammar and rhetoric |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

qbb | |

| Glottolog | oldl1238 |

Expansion of the Roman Republic during the 2nd century BC. Very little Latin is likely to have been spoken beyond the green area, and other languages were spoken even within it. | |

اللاتينية القديمة بالإنجليزية Old Latin ، هي اللغة اللاتينية في الفترة التي سبقت اللاتينية الكلاسيكية، وهي اللاتينية التي كانت قبل 75 ق.م..[1] (In New and Contemporary Latin, this language is called prisca Latinitas ("ancient Latin") rather than vetus Latina ("old Latin"), as vetus Latina is used to refer to a set of Biblical texts written in Late Latin.) It is ultimately descended from the Proto-Italic language.

The use of "old", "early" and "archaic" has been standard in publications of Old Latin writings since at least the 18th century. The definition is not arbitrary, but the terms refer to writings with spelling conventions and word forms not generally found in works written under the Roman Empire. This article presents some of the major differences.

The earliest known specimen of the Latin language appears on the Praeneste fibula. A new analysis performed in 2011 declared it to be genuine "beyond any reasonable doubt"[2] and dating from the Orientalizing period, in the first half of the seventh century BC.[3]

البنى حسب فقه اللغة

لغة العصور القديمة

The concept of Old Latin (Prisca Latinitas) is as old as the concept of Classical Latin, both dating to at least as early as the late Roman Republic. In that period Cicero, along with others, noted that the language he used every day, presumably the upper-class city Latin, included lexical items and phrases that were heirlooms from a previous time, which he called verborum vetustas prisca,[4] translated as "the old age/time of language".

During the classical period, Prisca Latinitas, Prisca Latina and other idioms using the adjective always meant these remnants of a previous language, which, in the Roman philology, was taken to be much older in fact than it really was. Viri prisci, "old-time men", were the population of Latium قبل تأسيس روما.

اللغات اللاتينية الأربع لإيزيدور

In the Late Latin period, when Classical Latin was behind them, the Latin- and Greek-speaking grammarians were faced with multiple phases, or styles, within the language. Isidore of Seville reports a classification scheme that had come into existence in or before his time: "the four Latins" ("Latinas autem linguas quattuor esse quidam dixerunt").[5] They were Prisca, spoken before the founding of Rome, when Janus and Saturn ruled Latium, to which he dated the Carmen Saliare; Latina, dated from the time of king Latinus, in which period he placed the laws of the Twelve Tables; Romana, essentially equal to Classical Latin; and Mixta, "mixed" Classical Latin and Vulgar Latin, which is known today as Late Latin. The scheme persisted with little change for some thousand years after Isidore.

جسد اللغة

Old Latin authored works began in the 3rd century BC. These are complete or nearly complete works under their own name surviving as manuscripts copied from other manuscripts in whatever script was current at the time. In addition are fragments of works quoted in other authors.

الأصوات

أمثلة

Notable Old Latin fragments still in existence include:

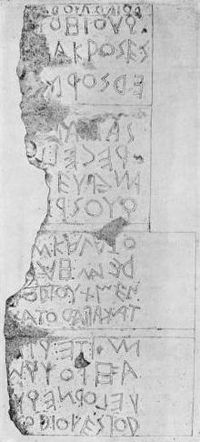

- The Forum inscription (illustration, right) (حوالي 550 BC)

- The Duenos inscription (حوالي 500 BC)

- The Castor-Pollux dedication (حوالي 500 BC)

- The Garigliano Bowl (حوالي 500 BC)

- The preserved fragments of the laws of the Twelve Tables (traditionally, 449 BC, attested much later)

- The Tibur pedestal (حوالي 400 BC)

- The Senatusconsultum de Bacchanalibus (186 BC)

- The Lapis Satricanus

- The Vase Inscription from Ardea

- The Corcolle Altar fragments

- The Carmen Arvale

- The Carmen Saliare

- The Scipionum Elogia

النحو والصوتيات (الإختلافات عن اللاتينية الكلاسيكية)

الأسماء

أول إنحراف (a)

The 'A-Stem Declension'. Nouns of this declension usually end in -a and are typically feminine.

| puella, –aī girl, maiden f. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | الجمع | |

| Nominative | puella | puellai |

| Genitive | puellās/-es/-aī | puellōm/ -āsom |

| Dative | puellai | puellaīs/-eīs/ -abos |

| Accusative | puellam | puellā |

| Ablative | puellād | puellaīs/-eīs/ -abos |

| Vocative | puella | puellai |

| Locative | puellā | puellaīs/-eīs |

حرف الإنحراف الثاني (b)

The 'O-Stem Declension'. Nouns of this declension are either masculine or neuter.

| campos, –oī field, plain m. |

saxom, –oī rock, stone n. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| المفرد | الجمع | المفرد | الجمع | |

| Nominative | campos | campoī | saxom | saxa |

| Genitive | campoī | campōm/ -ōsom | saxoī | saxōm/ -ōsom |

| Dative | campoī | campoīs | saxoī | saxoīs |

| Accusative | campom | campōs | saxom | saxa |

| Ablative | campōd | campoīs | saxōd | saxoīs/ -oes |

| Vocative | campe | campoī | saxe | saxoī |

| Locative | campō | campoīs | saxō | saxoīs/ -oes |

Note the genitive plural ending has two endings: the earlier -ōm, almost exactly like the Ancient Greek -ōn, and the later Archaic Latin form -ōsom. Due to the fact that in Archaic Latin /r/'s and /s/'s were often interchangeable, a phenomenon known as rhotacism, the later -ōsom evolved into the Classical Latin -ōrum.

حرف الإنحراف الثالث (c)

The 'E-Stem ' and 'I-Stem ' Declension. This declension contains nouns that are masculine, feminine, and neuter.

| Regs –es ملك مذكـّر | ||

|---|---|---|

| المفرد | الجمع | |

| Nominative | regs | reges |

| Genitive | regis | regōm |

| Dative | regei | regebos |

| Accusative | regem | reges |

| Ablative | regeid | regebos |

| Vocative | regs | reges |

| Locative | regei | regebos |

The nominative as regs instead of rex shows a common feature in Old Latin; the letter x was seldom used alone to designate the /ks/ or /gs/ sound, but instead, written as either 'ks', 'cs', or even 'xs'.

الضمائر الشخصية

Personal pronouns are among the most common thing found in Old Latin inscriptions. Note how in all three persons, the ablative singular ending is identical to the accusative singular.

| Ego, I | Tu, You | Suī, Himself, Herself, Etc. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | ego | tu | - |

| Genitive | mis | tis | sei |

| Dative | mihei, mehei | tibei | sibei |

| Accusative | mēd | tēd | sēd |

| Ablative | mēd | tēd | sēd |

| الجمع | |||

| Nominative | nōs | vōs | - |

| Genitive | nostrōm, -ōrum, -i | vostrōm, -ōrum, -i | sei |

| Dative | nōbeis, nis | vōbeis | sibei |

| Accusative | nōs | vōs | sēd |

| Ablative | nōbeis, nis | vōbeis | sēd |

الضمير النسبي

In Old Latin, the relative pronoun is also another common concept, especially in inscriptions. Unfortunately, the forms are quite inconsistent and leave much to be reconstructed by scholars.

| queī, quaī, quod who, what | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| المذكر | المؤنث | المحايد | |

| Nominative | queī | quaī | quod |

| Genitive | quoius, quoios | quoia | quoium, quoiom |

| Dative | quoī, queī, quoieī, queī | ||

| Accusative | quem | quam | quod |

| Ablative | quī, quōd | quād | quōd |

| الجمع | |||

| Nominative | ques, queis | quaī | qua |

| Genitive | quōm, quōrom | quōm, quārom | quōm, quōrom |

| Dative | queis, quīs | ||

| Accusative | quōs | quās | quōs |

| Ablative | queis, quīs | ||

الأفعال

المضارع القديم والتام

There is not much actual proof of the inflection of Old Latin verb forms and the few carvings we have hold many inconsistencies between forms. Therefore, the forms below are ones that are both proven by scholars through Old Latin carvings, and recreated by scholars based on other early Indo-European languages such as Greek, Oscan, Umbrian, and other Italic dialects.

| Indicative Present: Sum | Indicative Present: Facio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Classical | Old | Classical | |||||

| المفرد | الجمع | المفرد | الجمع | المفرد | الجمع | المفرد | الجمع | |

| First Person | som, esom | somos, sumos | sum | sumus | fac(e/ī)o | fac(e)imos | faciō | facimus |

| Second Person | es | esteīs | es | estis | fac(e/ī)s | fac(e/ī)teis | facis | facitis |

| Third Person | est | sont | est | sunt | fac(e/ī)d/-(e/i)t | fac(e/ī)ont | facit | faciunt |

| Indicative Perfect: Sum | Indicative Perfect: Facio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Classical | Old | Classical | |||||

| المفرد | الجمع | المفرد | الجمع | المفرد | الجمع | المفرد | الجمع | |

| First Person | fuei | fuemos | fuī | fuimus | (fe)fecei | (fe)fecemos | fēcī | fēcimus |

| Second Person | fuistei | fuisteīs | fuistī | fuistis | (fe)fecistei | (fe)fecisteis | fēcistī | fēcistis |

| Third Person | fued/fuit | fueront/-erom | fuit | fuērunt | (fe)feced/-et | (fe)feceront/-erom | fēcit | fēcērunt |

انظر أيضا

وصلات خارجية

المصادر

- ^ "Archaic Latin". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition.

- ^ Maras, Daniele F. (Winter 2012). "Scientists declare the Fibula Praenestina and its inscription to be genuine "beyond any reasonable doubt" (PDF). Etruscan News. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 فبراير 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Maras, Daniele Federico. "Scientists declare the Fibula Prenestina and its inscription to be genuine 'beyond any reasonable doubt'". academia.edu. Archived from the original on 19 أكتوبر 2017. Retrieved 4 مايو 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ De Oratoribus, I.193.

- ^ Book IX.1.6.