اللاتينية الكلاسيكية

| اللاتينية الكلاسيكية | |

|---|---|

| Latinitas | |

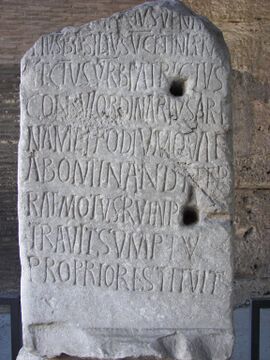

النقش اللاتيني في الكولوسوم | |

| النطق | [laˈtiːnitaːs] |

| موطنها | الجمهورية الرومانية، الامبراطورية الرومانية |

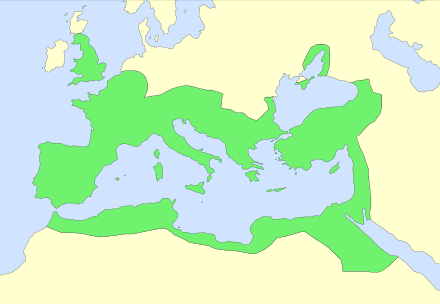

| المنطقة | mare nostrum (البحر المتوسط) |

| الحقبة | 75 ق.م حتى القرن الثالث الميلاد، عندما تطورت إلى اللاتينية المتأخرة |

إندو-اوروپية

| |

الصيغة المبكرة | |

| الأبجدية اللاتينية الكلاسيكية | |

| الوضع الرسمي | |

لغة رسمية في | الجمهورية الرومانية، الامبراطورية الرومانية |

| ينظمها | مدارس النحو والبلاغة |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

lat-cla | |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAB-aaa |

إنتشار اللاتينية، 60 م | |

اللاتينية الكلاسيكية، كإصطلاح معاصر تستخدم لوصف صيغة من اللغة اللاتينية يعترف بها كلغة قياسية كتاب الجمهورية الرومانية المتأخرة والامبراطورية الرومانية. في بعض الفترات المتأخرة كان ينظر إليها كلاتينية "جيدة"، وكان ينظر للإصدارات الأخيرة منها على أنها وضيعة أو فاسدة. كلمة "اللاتينية" تستخدم الآن إفتراضياً لوصف "اللاتينية الكلاسيكية"، ومن ثم، على سبيل المثال، فكتب النصوص اللاتينية المعاصرة توصف اللاتينية الكلاسيكية. ماركوس تيليوس كيكرو ومعاصروه من الجمهورية المتأخرة، كانوا يستخدمون lingua Latina وsermo Latinus والتي تعين اللغة اللاتينية في مقابل اللغات اليونانية والأخرى، وsermo vulgaris أو sermo vulgi للإشارة إلى اللاتينية المستخدمة بين العامة وغير المتعلمين، وكانت الخطب الأكثر تقديراً لديهم تكتب بإستخدام اللاتينيتاس، "اللاتينيتي"، مع التلميح إلى أنها جيدة. يطلق البعض عليها sermo familiaris، "خطاب العائلات الكريمة"، sermo urbanus، "خطاب المدينة" أو نادراً sermo nobilis، "الخطاب النبيل"، وبصفة أسياسية بجانب Latinitas كان يستخدم Latine (ظرف حال)، "في اللاتينية الجيدة"، أو Latinius (درجة نسبية من الصفة)، "اللاتينية الجيدة."

الاتينيتاس كانت لغة محادثة وكتابة. علاوة على ذلك، كانت اللغة التي يدرس بها في المدارس. كانت تطبق عليه القواعد التوجيهية، وعند تناول موضوع خاص، مثل الشعر أو البلاغة، كانت تضاف قواعد إضافية. حالياً اللاتينيتاس المقروءة أصبحت بائدة (لصالح السجلات الأخرى المختلفة التي دونت بعدها) قواعد، معظم أجزاء، النصوص المصقولة (پوليتوس) قد تعطي مظهر للغة مصطنعة، لكن اللاتينيتاس كانت صيغة من السرمو، أو اللغة المنطوقة وتحتفظ بالعفوية على هذا النحو. No authors are noted for the type of rigidity evidenced by stylized art, except possibly the repetitious abbreviations and stock phrases of inscriptions.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

البنى اللغوية

عصور اللاتينية

عام 1870 ڤيلهلم سيگموند توفل في Geschichte der Römischen Literatur (تاريخ الأدب الروماني) ابتكر تصنيف لغوي نهائي لللاتينية الكلاسيكية معتمدا على الاستخدامات المجازية للأسطورة القديمة عصور الرجال، a practice then universally current: a Golden Age and a Silver Age of classical Latin were to be presumed. The practice and Teuffel's classification, with modifications, are still in use. His work was translated into English as soon as published in German by Wilhelm Wagner, who corresponded with Teuffel. Wagner published the English translation in 1873. Teuffel divides the chronology of classical Latin authors into several periods according to political events, rather than by style. Regarding the style of the literary Latin of those periods he had but few comments.

مؤلفو العصر الذهبي

الجمهوري

A list of some canonical authors of the period, whose works have survived in whole or in part (typically in part, some only short fragments) is as follows:

- Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC), highly influential grammarian

- Titus Pomponius Atticus (112/109 – 35/32), publisher and correspondent of Cicero

- Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BC), orator, philosopher, correspondent, whose works define golden Latin prose and are used in Latin curricula beyond the elementary level

- Servius Sulpicius Rufus (106–43 BC), jurist, poet

- Decimus Laberius (105–43 BC), writer of mimes

- Marcus Furius Bibaculus (1st century BC), writer of ludicra

- Gaius Julius Caesar (103–44 BC), general, historian

- Gaius Oppius (1st century BC), secretary to Julius Caesar, probable author under Caesar's name

- Gaius Matius (1st century BC), public figure, correspondent with Cicero

- Cornelius Nepos (100–24 BC), biographer

- Publilius Syrus (1st century BC), writer of mimes and maxims

- Quintus Cornificius (1st century BC), public figure and writer on rhetoric

- Titus Lucretius Carus (Lucretius; 94–50 BC), poet, philosopher

- Publius Nigidius Figulus (98–45 BC), public officer, grammarian

- Aulus Hirtius (90–43 BC), public officer, military historian

- Gaius Helvius Cinna (1st century BC), poet

- Marcus Caelius Rufus (87–48 BC), orator, correspondent with Cicero

- Gaius Sallustius Crispus (86–34 BC), historian

- Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (Cato the Younger; 95–46 BC), orator

- Publius Valerius Cato (1st century BC), poet, grammarian

- Gaius Valerius Catullus (Catullus; 84–54 BC), poet

- Gaius Licinius Macer Calvus (82–47 BC), orator, poet

الأغسطي

الكتاب الأغسطيون يضمون:

- پوپليوس ڤرجيليوس (ڤرجيل، وتُنطق أيضاً ڤـِرجيل، 70–19 ق.م)

- Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace; 65–8 BC), known for lyric poetry and satires

- Sextus Aurelius Propertius (50–15 BC), poet

- Albius Tibullus (54–19 BC), elegiac poet

- تيتوس ليڤيوس (ليڤي؛ 64 ق.م. – 12 م)، مؤرخ

- Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid) (43 BC – 18 AD), poet

- Grattius Faliscus, a contemporary of Ovid), poet

- Marcus Manilius (1st century BC & AD), astrologer, poet

- Gaius Julius Hyginus (64 ق.م – 17 ADمlibrarian, poet, mythographer

- Marcus Verrius Flaccus (55 ق.م – 20 م)، نحوي، فيه لغوي، واضع تقويم

- Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80-70 ق.م — بعد 15 ق.م)، مهندس، معماري

- Marcus Antistius Labeo (ت. 10 أو 11 م)، مشرع، فقيه لغوي

- Lucius Cestius Pius (القرن 1 ق.م، و1 م)، معلم لاتينية

- Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus (القرن 1 ق.م)، مؤرخ، عالم طبيعة

- Marcus Porcius Latro (القرن 1 ق.م)، عالم بلاغة

- Gaius Valgius Rufus (قنصل 12 ق.م)، شاعر،

العصر الفضي

أطلقت الرواية المتواترة على الآداب اللاتينية فيما بين 14، 117م اسم العصر الفضي للدلالة على أن هذه الآداب قد نزلت عن المستوى الثقافي الرفيع الذي بلغته في عصر أغسطس؛ والرواية هي صوت الزمان، والزمان هو الوسط الذي يختار فيه بين الطيب والخبيث، والعقل الحذر يجل حكمها لأن الشباب وحده هو الذي يعرف ما لا تعرفه عشرون قرناً من الزمان. على أننا نرجو أن يؤذن لنا بأن نرجئ حكمنا على هذا العصر، وأن نستمع بلا تحيز إلى ما يقوله عنه لو كان، وبترونيوس، وسنكا، وبلني الأكبر، وسلسس Celsus، واستاتيوس Statius ومارتيال، وكونتليان، وأن نستمع في أبواب أخرى من هذا الكتاب إلى أقوال تاستس، وجوفنال، وبلني الأصغر، وإبكتنس Epictetus، وأن نستمتع بأقوالهم استمتاع من لم يسمعوا قط بأنهم عاشوا في عصر من العصور الاضمحلال. ذلك أنا نجد في كل عصر شيئاً يضمحل وشيئاً ينمو؛ فالمقطوعات الشعرية الفكهة، والهجاء، والروايات القصصية، والتاريخ، والفلسفة، بلغت كلها في العصر الفضي ذروة مجدها، كما أن فن النحت الواقعي، والعمارة الضخمة قد بلغا فيه ما لم يبلغاه في عصر آخر من عصور الفن الروماني.

وفي هذا العصر دخل حديث الشارع مرة أخرى في الأدب، وأهملت بعض قواعد النحو والصرف، وحذت الحروف الساكنة من أواخر الكلمات، ولم يعبأ بها الرومان أكثر مما كان يعبأ بها الغاليون. وحدث في منتصف القرن الأول أو حواليه أن رقق الحرفان الاتينيان V (وكان ينطق كما ينطبق حرف W (و) في اللغة الإنكليزية)، B (إذا كان بين حرفين متحركين) حتى أصبحا مماثلين في النطق لحرف V الإنكليزي. وهكذا أصبحت كلمة Babere ومعناها التملك ينطق بها Bavere، وكان هذا تمهيداً للكلمة الإيطالية avere، والفرنسية Avoir؛ وأخذت كلمة Vinum ومعناها النبيذ أو الخمر تقترب في النطق من كلمة Vino الإيطالية، وكلمة Vin الفرنسية وذلك بإهمال الحرف الساكن الأخير المتغير. وقصارى القول أن اللغة الاتينية شرعت تمهد السبيل للغات القومية الإيطالية والأسبانية والفرنسية.

وجدير بنا أن نعترف في هذا المقام بـأن الخطابة ازدهرت وقتئذ على حساب البلاغة، وأن النحو ارتقى على حساب الشعر؛ وأن لمقتدرين الكفاة وجهوا كل جهودهم إلى دراسة شكل اللغة وتطورها ودقائقها، وإلى نشر اللصوص التي أصبحت في ذلك العهد نصوصاً "فصحى"، وإلى صياغة قواعد الكتابة الأدبية الراقية والخطب القضائية، وأوزان الشعر، وتقاسيم الجمل في النثر. وحأول كلوديوس أن يدخل بعض الإصلاح على الحروف الهجائية، وجعل نيرون الشعر طراز العصر المحبب، وألف سنكا الأكبر كتباً في البلاغة، وحجته في هذا أن الفصاحة تزيد كل قوة إلى ضعفيها؛ ولم يكن أحد يرقى في رومة بغير الفصاحة إلا قواد الجند وحدهم، وحتى هؤلاء القواد كان يجب أن يكونوا خطباء. واستحوذ جنون البلاغة على جميع أشكال الأدب: فأصبح الشعر خطابياً، والنثر شعرياً، وحتى بلني نفسه كتب صفحة بليغة في المجلدات الستة من كتابه في التاريخ الطبيعي. وأخذ الناس يغلون أنفسهم باتزان عباراتهم، وتناغم جملهم، وأضحت التواريخ خطباً حماسية، وأخذ الفلاسفة يجهدون أنفسهم في البحث عن النكات، وشرع كل إنسان يكتب أمثالاً مركزة موجزة، وصار الأدباء كلهم يكتبون الشعر ويقرؤونه لأصدقائهم حول مناضد في ردهات أو دور تمثيل يستأجرونها لهذا الغرض، بل إنهم كانوا يقرؤونه في الحمامات نفسها، حتى شكا من ذلك مارتيال مر الشكوى. وعقدت مباريات عامة للشعراء، ينال الفائزون فيها جوائز وتحتفل بهم المجالس البلدية، ويضع الأباطرة عل رؤوسهم أكاليل النصر. وكان الأشراف والزعماء يرحبون بأن تُهدى إليهم المؤلفات أو يُثنى عليهم فيها، وكانوا يجيزون صحبها بالولائم أو الأموال. وكانت شهوة الشعر مما أكسب هذه الفترة وتلك المدنية اللتين دنستهما الإباحية الجنسية وعهود الإرهاب المتكررة نقول كانت هذه الشهوة مما أكسب هذه الفترة ذلك الجمال الذيؤ يخلعه المؤلفون الهواة على العصر الذي يعيشون فيه. [1]

واجتمع الشعر والإرهاب في حياة لوكان، وكان سنكا الكبير جده، وسنكا الفيلسوف عمه. وقد ولد في قرطبة عام 39 وسمي ماركس أنيوس لوكانس Marcus Annaeus Lucanus، وجيء به في طفولته إلى رومة ونشأ في بيئة أرستقراطية يصطرعفيها الشعر والفلسفة مع دسائس الحب ومع السياسة في سبيل الغلبة والمكانة السامية في الحياة. ولما بلغ الحادية والعشرين من عمره اشترك في المباريات التي عقدت أثناء الألعاب النيرونية، وتقدم إليها بقصيدة "في مدح نيرون" نال عليها جائزة. وأدخله سنكا في بلاط الإمبراطور، وسرعان ما أخذ الشاعر والإمبراطور يتطارحان الملاحم. وأرتكب لوكان غلطة شنيعة إذ كسب الجائزة الأولى في مباراة شعرية مع الزعيم، فما كان من نيرون إلا أن أمره بألا ينشر بعدها شعراً، وانسحب لوكان ليثأر لنفسه سراً بتأليف ملحمة قوية ولكنها خطابية سماها فرساليا رأى فيها الحرب الأهلية بعين الأرستقراطية البمبية. ولم يبخس لوكان في هذه الملحمة قيصر حقه، وقد وصفه فيها بتلك العبارة البليغة "Nil actum credens cum quid superssent agendum يظن أنه لم يفعل شيئاً إذا ما بقي ما لم يفعله"، ولكن البطل الحقيقي في هذه الملحمة هو كاتو الأصغر الذي يضعه لو كان في مصاف الآلهة في سطر مشهور من سطور كتابهِ "Victrix causa deis placiut sed victa catoni إن القضية الرابحة سرت الآلهة، ولكن القضية الخاسرة كاتو". وقد أحب لوكان أيضاً القضية الخاسرة، ومات في سبيلها. فقد اشترك في مؤامرة ليحل بيزو محل نيرون، وقبض عليه، فخارت قواه (ولم يكن قد جأوز السادسة والعشرين من عمره)، وباح بأسماء شركائه في المؤامرة، حتى اسم أمه نفسها-على حد قول المؤرخين. ولما أيد نيرون حكم الإعدام الذي صدر عليهِ، استعاد شجاعته، ودعا أصدقاءه إلى وليمة، وأكل معهم حتى شبع، ثم فتح بعض أورته، وأنشد ما قاله من الشعر في هجو الظلم والطغيان بينما كان دم الحياة ينزف من جسمه.

مؤلفو العصر الفضي

…the continual apprehension in which men lived caused a restless versatility… Simple or natural composition was considered insipid; the aim of language was to be brilliant… Hence it was dressed up with abundant tinsel of epigrams, rhetorical figures and poetical terms… Mannerism supplanted style, and bombastic pathos took the place of quiet power.

The content of new literary works was continually proscribed by the emperor (by executing or exiling the author), who also played the role of literary man (typically badly). The talent therefore went into a repertory of new and dazzling mannerisms, which Teuffel calls "utter unreality." Crutwell picks up this theme:[2]

The foremost of these [characteristics] is unreality, arising from the extinction of freedom… Hence arose a declamatory tone, which strove by frigid and almost hysterical exaggeration to make up for the healthy stimulus afforded by daily contact with affairs. The vein of artificial rhetoric, antithesis and epigram… owes its origin to this forced contentment with an uncongenial sphere. With the decay of freedom, taste sank…

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

حتى وفاة ترايان، 114 م

- Aulus Cremutius Cordus (ت. 25 AD), historian

- Marcus Velleius Paterculus (19 BC – 31 AD), military officer, historian

- Valerius Maximus (1st century AD), rhetorician

- Masurius Sabinus (1st century AD), jurist

- Phaedrus (c. 15 BC – 50 AD), fabulist

- Germanicus Julius Caesar (15 BC – 19 AD), royal family, imperial officer, translator

- Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 BC – 50 AD), physician, encyclopedist

- Quintus Curtius Rufus (1st century AD), historian

- Cornelius Bocchus (1st century AD), natural historian

- Pomponius Mela (1st century AD), geographer

- Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 BC – 65 AD), educator, imperial advisor, philosopher, man of letters

- Titus Calpurnius Siculus (1st century AD), poet

- Marcus Valerius Probus (1st century AD), literary critic

- Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (10 BC – 54 AD), Emperor, man of letters, public officer

- Gaius Suetonius Paulinus (1st century AD), general, natural historian

- Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (4–70 AD), military officer, agriculturalist

- Quintus Asconius Pedianus (9 BC – 76 AD), historian, Latinist

- Gaius Musonius Rufus (1st century AD), stoic philosopher

- Quintus Marcius Barea Soranus (1st century AD), imperial officer and public man

- Gaius Plinius Secundus (23–79 AD), imperial officer, encyclopedist

- Gaius Valerius Flaccus (1st century AD), poet

- Tiberius Catius Silius Italicus (25–101 AD), epic poet

- Gaius Licinius Mucianus (1st century AD), general, man of letters

- Gaius Petronius Arbiter (27–66 AD), courtier, satirist

- Lucilius Junior (1st century AD), poet

- Aulus Persius Flaccus (34–62 AD), poet and satirist

- Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (35–100 AD), rhetorician

- Sextus Julius Frontinus (40–103 AD), engineer, writer

- Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (39–65 AD), poet, historian

- Publius Iuventius Celsus Titus Aufidius Hoenius Severianus (1st and early 2nd centuries AD), imperial officer, jurist

- Aemilius Asper (1st & 2nd centuries AD), grammarian, literary critic

- Marcus Valerius Martialis (38/41–102/104 AD), poet

- Publius Papinius Statius (45–96 AD), poet

- Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (61–112 AD), attorney, magistrate, correspondent

- Decimus Junius Juvenalis (1st & 2nd centuries AD), poet, satirist

- Publius Annaeus Florus (1st & 2nd centuries AD), poet, rhetorician and probable author of the epitome of Livy

- Velius Longus (1st & 2nd centuries AD), grammarian, literary critic

- Flavius Caper (1st & 2nd centuries AD), grammarian

- Publius or Gaius Cornelius Tacitus (56–117 AD), imperial officer, historian and in Teuffel's view "the last classic of Roman literature."

حتى وفاة ماركوس أورليوس، 180 م

- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (70/75 – after 130 AD), biographer

- Marcus Junianus Justinus (2nd century AD), historian

- Lucius Octavius Cornelius Publius Salvius Julianus Aemilianus (100–70 AD), imperial officer, jurist

- Sextus Pomponius (2nd century AD), jurist

- Quintus Terentius Scaurus (2nd century AD), grammarian, literary critic

- Aulus Gellius (125 – after 180 AD), grammarian, polymath

- Lucius Apuleius Platonicus (123/125–80 AD), novelist

- Marcus Cornelius Fronto (100–70 AD), advocate, grammarian

- Gaius Sulpicius Apollinaris (2nd century AD), educator, literary commentator

- Granius Licinianus (2nd century AD), writer

- Lucius Ampelius (2nd century AD), educator

- Gaius (110–80 AD), jurist

- Lucius Volusius Maecianus (2nd century AD), educator, jurist

- Marcus Minucius Felix (2nd century AD), apologist of Christianity, "the first Christian work in Latin" (Teuffel)

- Sextus Julius Africanus (2nd century AD), Christian historian

- Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus (121–180 AD, stoic philosopher, Emperor in Latin, essayist in ancient Greek, role model of the last generation of classicists (Cruttwell)

الهوامش

- ^ ديورانت, ول; ديورانت, أرييل. قصة الحضارة. ترجمة بقيادة زكي نجيب محمود.

- ^ Cruttwell 1877, p. 6.

المراجع

- Bielfeld, Baron (1770), The Elements of Universal Erudition, Containing an Analytical Abridgement of the Science, Polite Arts and Belles Lettres, III, Hooper, W (Trans.), London: G Scott

- Citroni, Mario (2006), "The Concept of the Classical and the Canons of Model Authors in Roman Literature", in Porter, James I, The Classical Tradition of Greece and Rome, Packham, RA (Trans.), Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 204–34

- Cruttwell, Charles Thomas (1877), A History of Roman Literature from the Earliest Period to the Death of Marcus Aurelius, London: Charles Griffin & Co

- Littlefield, George Emery (1904), Early Schools and School-books of New England, Boston: Club of Odd Volumes

- Settis, Salvatore (2006), The Future of the ‘Classical’, Cameron, Allan (Trans.), Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity Press

- Teuffel, Wilhelm Sigismund (1873), A History of Roman Literature, Wagner, Wilhelm (Trans.), London: George Bell & Sons

- Teuffel, Wilhelm Sigismund; Schwabe, Ludwig (1892), Teuffel's History of Roman Literature Revised and Enlarged, II, The Imperial Period, Warr, George CW (Trans.) (from the 5th German ed.), London: George Bell & Sons

انظر أيضاً

وصلات خارجية

- Cruttwell, Charles Thomas (1877, 2005). "A History of Roman Literature from the Earliest Period to the Death of Marcus Aurelius". London: Charles Griffin and Company, Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Teuffel, W.S. (1870, 2001). "Geschichte der Römischen Literatur" (in German). Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, Internet Archive. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Languages without family color codes

- Historical forms of languages with ISO codes

- Languages without ISO 639-3 code but with Linguist List code

- Languages without ISO 639-3 code but with Linguasphere code

- Language articles with unreferenced extinction date

- Language articles missing Glottolog code

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- روما القديمة

- لغة لاتينية

- لغات كلاسيكية