كمنتس

كمنتس

Chemnitz | |

|---|---|

مدينة | |

|

From top, left to right: Old town hall and High Tower (St James' Church) at night, Castle Pond (Schlossteich) from above, Rabenstein Castle, Karl Marx Monument, Chemnitz Opera House at night, Red Tower (right) and Galerie Roter Turm shopping centre (left) | |

أظهر Location of كمنتس | |

| الإحداثيات: 50°50′N 12°55′E / 50.833°N 12.917°E | |

| البلد | ألمانيا |

| الولاية | ساكسونيا |

| District | Urban district |

| الحكومة | |

| • العمدة | Sven Schulze[1] (SPD) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 220٫85 كم² (85٫27 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 296 m (971 ft) |

| منطقة التوقيت | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 09001–09247 |

| Dialling codes | 0371

037200 (Wittgensdorf) 037209 (Einsiedel) 03722 (Röhrsdorf) 03726 (Euba) |

| لوحة السيارة | C |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

كـِمنـِتس (Chemnitz؛ ألمانية: [ˈkɛmnɪts] (![]() listen))، وكانت تُعرف من 1953 إلى 1990 بإسم كارل-ماركس-شتات Karl-Marx-Stadt، هي ثالث أكبر مدينة في ولاية ساكسونيا الحرة، ألمانيا. كمنتس هي مدينة مستقلة ليست جزءاً من أي مقاطعة ومقر Landesdirektion Sachsen. تقع في السفوح الشمالية لـجبال أوره، وهي جزء من Central German Metropolitan Region. It is the 28th largest city of Germany as well as the fourth largest city in the area of former East Germany after (East) Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden. The city is part of the Central German Metropolitan Region, and lies in the middle of a string of cities sitting in the densely populated northern foreland of the Elster and Ore Mountains, stretching from Plauen in the southwest via Zwickau, Chemnitz and Freiberg to Dresden in the northeast.

listen))، وكانت تُعرف من 1953 إلى 1990 بإسم كارل-ماركس-شتات Karl-Marx-Stadt، هي ثالث أكبر مدينة في ولاية ساكسونيا الحرة، ألمانيا. كمنتس هي مدينة مستقلة ليست جزءاً من أي مقاطعة ومقر Landesdirektion Sachsen. تقع في السفوح الشمالية لـجبال أوره، وهي جزء من Central German Metropolitan Region. It is the 28th largest city of Germany as well as the fourth largest city in the area of former East Germany after (East) Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden. The city is part of the Central German Metropolitan Region, and lies in the middle of a string of cities sitting in the densely populated northern foreland of the Elster and Ore Mountains, stretching from Plauen in the southwest via Zwickau, Chemnitz and Freiberg to Dresden in the northeast.

Located in the Ore Mountain Basin, the city is surrounded by the Ore Mountains to the south and the Central Saxon Hill Country to the north. The city stands on the Chemnitz River (progression: قالب:PZwickauer Mulde), which is formed through the confluence of the rivers Zwönitz and Würschnitz in the borough of Altchemnitz.

The name of the city as well as the names of the rivers are of Slavic origin. Chemnitz is the third largest city in the Thuringian-Upper Saxon dialect area after Leipzig and Dresden. The city's economy is based on the service sector and manufacturing industry. Chemnitz University of Technology has around 10,000 students.

Chemnitz will be the European Capital of Culture of 2025.[2] يقوم اقتصاد المدينة على service sector and manufacturing industry. جامعة كمنتس للتكنولوجيا تضم نحو 10,000 طالب.

Etymology

Chemnitz is named after the river Chemnitz, a small tributary of the Zwickau Mulde. The word "Chemnitz" is from the Sorbian language (صوربية عليا: Kamjenica), and means "stony [brook]". The word is composed of the Slavic word kamen meaning "stone" and the feminine suffix -ica.

It is known in Czech as Saská Kamenice and in Polish as Kamienica Saska. There are many other towns named Kamienica or Kamenice in areas with past or present Slavic settlement.

التاريخ

المدينة الإمبراطورية الحرة

An early Slavic tribe's settlement was located at Kamienica, and the first documented use of this name was in 1143, as the location of a Benedictine monastery around which a settlement grew. Around 1170, Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor granted this the rights of a free imperial city. Kamienica was later Germanised as Chemnitz.

مايسن وساكسونيا

In 1307, the town became subordinate to the Margraviate of Meissen, the predecessor of the Saxon state. In medieval times, Chemnitz became a centre of textile production and trade. More than one third of the population worked in textile production. In 1356 the Margraviate was succeeded by the Electorate of Saxony.

Geologist Georgius Agricola (1494-1555), author of several significant works on mining and metallurgy including the landmark treatise De Re Metallica, became city physician of Chemnitz in 1533 and lived here until his death in 1555. In 1546 he was elected a Burgher of Chemnitz and in the same year also was appointed Burgomaster (lord mayor), serving again in 1547, 1551, and 1553. In spite of having been a leading citizen of the city, when Agricola died in 1555 the Protestant Duke denied him burial in the city's cathedral due to Agricola's allegiance to his Roman Catholic faith. Agricola's friends arranged for his remains to be buried in more sympathetic Zeitz, approximately 50 km away.[3] Chemnitz became a famous trading and textile manufacturing town.

In 1806, with the end of the Holy Roman Empire, the Electorate was renamed as the Kingdom of Saxony, and this survived until the revolutions of 1918 which followed the Armistice ending the First World War.

By the early 19th century, Chemnitz had become an industrial centre (sometimes called "the Saxon Manchester", ألمانية: Sächsisches Manchester, تـُنطق [ˈzɛksɪʃəs ˈmɛntʃɛstɐ] (![]() listen)). Important industrial companies were founded by Richard Hartmann, Louis Schönherr and Johann von Zimmermann. Chemnitz became a centre of innovation in the kingdom of Saxony and later in Germany. In 1913, Chemnitz had a population of 320,000 and, like Leipzig and Dresden, was larger at that time than today. After losing inhabitants due to the First World War Chemnitz grew rapidly again and reached its all-time peak of 360,250 inhabitants in 1930. Thereafter, growth was stalled by the world economic crisis.

listen)). Important industrial companies were founded by Richard Hartmann, Louis Schönherr and Johann von Zimmermann. Chemnitz became a centre of innovation in the kingdom of Saxony and later in Germany. In 1913, Chemnitz had a population of 320,000 and, like Leipzig and Dresden, was larger at that time than today. After losing inhabitants due to the First World War Chemnitz grew rapidly again and reached its all-time peak of 360,250 inhabitants in 1930. Thereafter, growth was stalled by the world economic crisis.

جمهورية ڤايمار

As a working-class industrial city, Chemnitz was a powerful center of socialist political organization after the First World War. At the foundation of the German Communist Party the local Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany voted by 1,000 votes to three to break from the party and join the Communist Party behind their local leaders, Fritz Heckert and Heinrich Brandler.[4] In March 1919 the German Communist Party had over 10,000 members in the city of Chemnitz.[5] Chemnitz was one of the big German industrial centers. Due to the export traffic a modern marshalling yard was erected 1929 in Chemnitz-Hilbersdorf. At that time it was a leading city in the European textile market. Auto Union (today Audi) was founded 1932 in Chemnitz.

الحرب العالمية الثانية

Allied bombing destroyed 41 per cent of the built-up area of Chemnitz during the Second World War.[6] Chemnitz contained factories that produced military hardware and a Flossenbürg forced labor subcamp (500 female inmates) for Astra-Werke AG.[7] The oil refinery was a target for bombers during the Oil Campaign of World War II, and Operation Thunderclap attacks included the following raids:

- 14/15 February 1945: The first major raid on Chemnitz used 717 RAF bombers, but due to cloud cover most bombs fell over open countryside.

- 2/3–5 March: USAAF bombers attacked the marshalling yards.[8]

- 5 March: 760 RAF bombers attacked.

The headquarters of the auto manufacturer Auto Union was based in Chemnitz from 1932 and its buildings were badly damaged. At the end of the war, the company's executives fled and relocated the company in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, where it evolved into Audi, now a brand within the Volkswagen group.

The World War II bombings left most of the city in ruins and post-war, the East German reconstruction included large low rise (and later high-rise Plattenbau) housing. Some tourist sites were reconstructed during the East German era and after German reunification. The city was occupied by Soviet troops on 8 May 1945.

جمهورية ألمانيا الديمقراطية

After the dissolution of the Länder (states) in the GDR in 1952, Chemnitz became seat of a district (Bezirk). On 10 May 1953, the city was renamed by decision of the East German government to Karl-Marx-Stadt after Karl Marx, in recognition of its industrial heritage and the Karl Marx Year marking the 135th anniversary of his birth and the 70th anniversary of his death.[9] GDR Prime Minister Otto Grotewohl said:

The people who live here do not look back, but look forward to a new and better future. They look at socialism. They look with love and devotion to the founder of the socialist doctrine, the greatest son of the German people, to Karl Marx. I hereby fulfill the government's decision. I carry out the solemn act of renaming the city and declare: From now on, this city bears the proud and mandatory name Karl-Marx-Stadt.[10]

After the city centre was destroyed in World War II, the East German authorities attempted to rebuild it to symbolise the conceptions of urban development of a socialist city. The layout of the city centre at that time was rejected in favour of a new road network. However, the original plans were not completed. In addition, the rapid development of housing took priority over the preservation of old buildings. So in the 1960s and 1970s, both in the centre as well as the periphery, large areas were built in Plattenbau apartment-block style, for example Yorckstraße. The old buildings of the period, which still existed especially in the Kassberg, Chemnitz-Sonnenberg and Chemnitz-Schloßchemnitz quarters, were neglected and fell increasingly into dereliction.[بحاجة لمصدر]

بعد إعادة التوحيد

On 23 April 1990, a referendum on the future name of the city was held: 76% of the voters voted for the old name "Chemnitz". On 1 June 1990, the city was officially renamed.[11]

After the reunification of Germany on 3 October 1990, the city of Chemnitz faced several difficult tasks. Many inhabitants migrated to the former West Germany and unemployment in the region increased sharply; in addition Chemnitz did not have adequate shopping facilities, but this was increasingly demanded.[12] Large shopping centers were constructed on the city periphery to the early 1990s.

Chemnitz is the only major German city whose centre was re-planned after 1990, similar to the reconstruction of several other German cities in the immediate post-war years. Plans for the recovery of a compressed city centre around the historic town hall in 1991 led to an urban design competition. This was announced internationally by the city and carried out with the help of the partner city of Düsseldorf. The mooted project on an essentially unused area of the former city would be comparable in circumference with the Potsdamer Platz in Berlin.[12]

Numerous internationally renowned architects such as Hans Kollhoff, Helmut Jahn and Christoph Ingenhoven provided designs for a new city centre. The mid-1990s began the development of the inner city brownfields around the town hall to a new town. In Chemnitz city more than 66,000 square meters of retail space have emerged. With the construction of office and commercial building on the construction site "B3" at the Düsseldorf court, the last gap in 2010 was closed in city centre image. The intensive development included demolition of partially historically valuable buildings from the period and was controversial.[13][14] Between 1990 and 2007 more than 250 buildings were leveled.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In late August 2018 the city was the site of a series of protests that attracted at least 8,000 people. The protests were attended by far-right and Neo-Nazi groups. News outlets reported about mob violence and riots. The protests started after two immigrants from the Middle East were arrested in connection with the murder of Daniel H., a 35 year old German man, the son of a German mother and a Cuban father, which had happened on 26 August. Violent clashes occurred between far-right protesters and far-left counter protesters, leading to injuries. The mobs outnumbered the local police presence. There were reports that rightist protesters chased down dark skinned bystanders and those that appeared to be foreigners on the streets before more police arrived and intervened. The riots were widely condemned by media outlets and politicians throughout Germany, and were "described as reminiscent of civil war and Nazi pogroms."[15][16][17][18]

The reports of mob violence and riots were criticized as incorrect later on. The German language Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung corrected its earlier reports, stating that there had evidently been no mob violence but there have been sporadic encroachments.[19] Minister President of Saxony Michael Kretschmer came to the same conclusion: "there were no mobs and man hunts".[20]

One week after the protests, a free "Concert against the Right" under the motto "We are more" (#wirsindmehr) attracted an audience of some 65,000 people.[21] A one-minute silence commemorated the murdered Daniel H., the son of a German mother and a Cuban father.[22] The concert itself has been criticized for far-left activities and violent song texts of some of the participating bands.[23][24]

الثقافة والمناظر

The city won the bid to be one of the two European Capitals of Culture (in 2025) on 28 October 2020, beating Hanover, Hildesheim, Magdeburg and Nuremberg.[25]

Theater Chemnitz offers a variety of theatre: opera (opera house from 1909), plays, ballet and Figuren (puppets), and runs concerts by the orchestra Robert-Schumann-Philharmonie (founded 1832).

Tourist sights include the Kassberg neighborhood with 18th and 19th century buildings and the Karl Marx Monument by Lev Kerbel, nicknamed Nischel (a Saxon dialect word for head) by the locals. Landmarks include the Old Town Hall with its Renaissance portal (15th century), the castle on the site of the former monastery, and the area around the opera house and the old university. The most conspicuous landmark is the red tower built in the late 12th or early 13th century as part of the city wall.

The Chemnitz petrified forest is located in the courtyard of Kulturkaufhaus Tietz. It is one of the very few in existence, and dates back several million years (details shown in the Museum of Natural Sciences "Museum für Naturkunde Chemnitz", founded 1859). Also within the city limits, in the district of Rabenstein, is the smallest castle in Saxony, Rabenstein Castle.

The city has changed considerably since German reunification. Most of its industry is now gone and the core of the city has been rebuilt with many shops as well as huge shopping centres. Many of these shops are international brands, including Zara, H&M, Esprit, Galeria Kaufhof, Leiser Shoes, and Peek & Cloppenburg. The large Galerie Roter Turm (Red Tower) shopping centre is very popular with young people.

The Chemnitz Industrial Museum is an Anchor Point of ERIH, the European Route of Industrial Heritage. Additional unique industrial monuments are located at the "Schauplatz Eisenbahn" (Saxon Railway Museum and Museum of Technology Cable Running System) in Chemnitz-Hilbersdorf. The State Museum of Archaeology Chemnitz[26] opened in 2014 and is located in the former Schocken Department Stores (architect: Erich Mendelsohn; opening of the department store: 1930).

The Museum Gunzenhauser, formerly a bank, opened on 1 December 2007. Alfred Gunzenhauser, who lived in Munich, had a collection of some 2,500 pieces of modern art, including many paintings and drawings by Otto Dix, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and others. The other great art museum in Chemnitz is located near central railway station, it is called "Museum am Theaterplatz" (erected 1909 as "König-Albert-Museum"). The Botanischer Garten Chemnitz is a municipal botanical garden, and the Arktisch-Alpiner Garten der Walter-Meusel-Stiftung is a non-profit garden specializing in arctic and alpine plants. Near the city center is the "Villa Esche" located (Henry-van-de-Velde-museum). This historical house was built in 1902 in art-nouveau-style by van de Velde.

معرض صور

Chemnitz Opera at Opernplatz

Bust of Karl Marx, the city's former namesake

Chemnitz petrified forest inside the Kulturkaufhaus Tietz

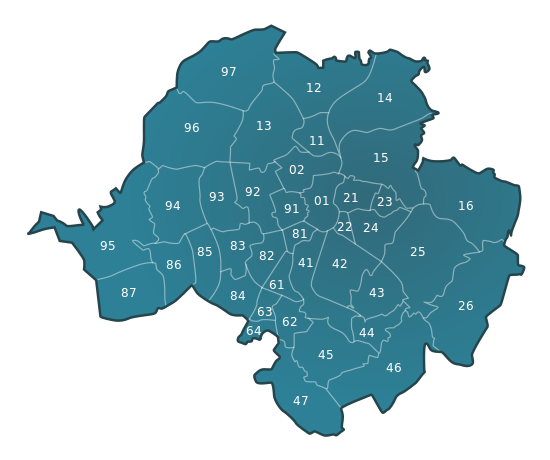

التقسيمات الإدارية

The city of Chemnitz consists of 39 neighborhoods. The neighborhoods of Einsiedel, Euba, Grüna, Klaffenbach, Kleinolbersdorf-Altenhain, Mittelbach, Röhrsdorf and Wittgensdorf are at the same time localities within the meaning of Sections 65 to 68 of the Saxon Municipal Code. These neighborhoods came in the wake of the last incorporation wave after 1990 as formerly independent municipalities to the city of Chemnitz and therefore enjoy this special position compared to the other parts of the city. These localities each have a local council, which, depending on the number of inhabitants of the locality concerned, comprises between ten and sixteen members as well as a chairman of the same. The local councils are to hear important matters concerning the locality. A final decision is, however, incumbent on the city council of the city of Chemnitz.[27] The official identification of the districts by numbers is based on the following principle: Starting from the city center (neighborhoods Zentrum and Schloßchemnitz), all other parts of the city are assigned clockwise in ascending order the tenth place of their index, the one-digit is awarded in the direction of city periphery in ascending order.

¹ also a locality |

The city area does not include a unified, closed settlement area after numerous incorporations. The rural settlements of mainly eastern districts are separated from the settlement area of the Chemnitz city center, whereas this partly continues over the western city limits to Limbach-Oberfrohna and Hohenstein-Ernstthal.

السياسة

العمدة

The first freely elected mayor after German reunification was Dieter Noll of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), who served from 1990 to 1991, followed by Joachim Pilz (CDU) until 1993. The mayor was originally chosen by the city council, but since 1994 has been directly elected. Peter Seifert of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) served from 1993 until 2006. Between 2006 and 2020 Barbara Ludwig (SPD) has served as mayor. Sven Schulze (SPD) was elected mayor in 2020.[1]

The most recent mayoral election was held on 20 September 2020, with a runoff held on 11 October, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Sven Schulze | Social Democratic Party | 22,241 | 23.1 | 31,749 | 34.9 | |

| Almut Patt | Christian Democratic Union | 20,630 | 21.4 | 20,047 | 22.0 | |

| Susanne Schaper | The Left | 14,584 | 15.1 | 14,668 | 16.1 | |

| Ulrich Oehme | Alternative for Germany | 11,731 | 12.2 | 12,034 | 13.2 | |

| Lars Faßmann | Independent | 11,470 | 11.9 | 12,515 | 13.8 | |

| Volkmar Zschocke | Alliance 90/The Greens | 6,811 | 7.1 | Withdrew | ||

| Matthias Eberlein | Free Voters | 3,394 | 3.5 | Withdrew | ||

| Paul Vogel | Die PARTEI | 1,527 | 1.6 | Withdrew | ||

| Valid votes | 96,428 | 99.5 | 91,017 | 99.7 | ||

| Invalid votes | 489 | 0.5 | 285 | 0.3 | ||

| Total | 96,917 | 100.0 | 91,302 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 194,952 | 49.7 | 194,850 | 46.9 | ||

| Source: Wahlen in Sachsen | ||||||

مجلس المدينة

The most recent city council election was held on 26 May 2019, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 69,195 | 20.0 | 13 | |||

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 62,053 | 17.9 | ▲ 12.3 | 11 | ▲ 8 | |

| The Left (Die Linke) | 58,009 | 16.7 | 10 | |||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 40,357 | 11.6 | 7 | |||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 39,908 | 11.5 | ▲ 3.6 | 7 | ▲ 2 | |

| Pro Chemnitz/German Social Union (PRO.DSU) | 26,606 | 7.7 | ▲ 2.0 | 5 | ▲ 2 | |

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 25,623 | 7.4 | ▲ 1.9 | 4 | ▲ 1 | |

| Die PARTEI (PARTEI) | 10,260 | 3.0 | ▲ 2.4 | 1 | ▲ 1 | |

| People's Solidarity (Vosi) | 7,862 | 2.3 | 1 | |||

| Pirate Party Germany (Piraten) | 6,817 | 2.0 | ▲ 0.1 | 1 | ±0 | |

| Valid votes | 118,548 | 98.5 | ||||

| Invalid votes | 1,837 | 1.5 | ||||

| Total | 120,385 | 100.0 | 60 | ±0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 196,515 | 61.3 | ▲ 17.2 | |||

| Source: Wahlen in Sachsen | ||||||

التجديد الحضري

Heavy destruction in World War II as well as post-war demolition to erect a truly socialist city centre left the city with a vast open space around its town hall where once a vibrant city heart had been. Because of massive investment in out-of-town shopping right after reunification, it was not until 1999 that major building activity was started in the centre. Comparable to Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, a whole new quarter of the city was constructed in recent years. New buildings include the Kaufhof department store by Helmut Jahn, Galerie Roter Turm with a façade by Hans Kollhoff and Peek & Cloppenburg clothing store by Ingenhofen and Partner.

الاقتصاد

Chemnitz is the largest city of the Chemnitz-Zwickau urban area and is one of the most important economic areas of Germany's new federal states. Chemnitz had a GDP of €8.456 billion in 2016, with GDP per capita at €34,166.[28] Since about 2000, the city's economy has recorded high annual GDP growth rates; Chemnitz is among the top ten German cities in terms of growth rate. The local and regional economic structure is characterized by medium-sized companies, with the heavy industrial sectors of mechanical engineering, metal processing, and vehicle manufacturing as the most significant industries.

About 100,000 people are employed, of whom about 46,000 commute from other municipalities.[29] 16.3% of employees in Chemnitz have a university or college degree, twice the average rate in Germany.

معرض صور

Volkswagen is the largest employer in the Chemnitz-Zwickau Agglomeration.

Chemnitz is the centerpiece of tourism in the Ore Mountains.

السكان

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1466 | 3٬455 | — |

| 1501 | 4٬400 | +27.4% |

| 1530 | 4٬318 | −1.9% |

| 1551 | 5٬616 | +30.1% |

| 1610 | 5٬500 | −2.1% |

| 1657 | 3٬000 | −45.5% |

| 1700 | 4٬873 | +62.4% |

| 1790 | 9٬162 | +88.0% |

| 1801 | 10٬835 | +18.3% |

| 1820 | 14٬455 | +33.4% |

| 1831 | 15٬735 | +8.9% |

| 1840 | 23٬476 | +49.2% |

| 1852 | 35٬163 | +49.8% |

| 1861 | 45٬432 | +29.2% |

| 1871 | 68٬229 | +50.2% |

| 1885 | 110٬817 | +62.4% |

| 1900 | 206٬913 | +86.7% |

| 1905 | 244٬927 | +18.4% |

| 1910 | 287٬807 | +17.5% |

| 1913 | 326٬075 | +13.3% |

| 1916 | 285٬285 | −12.5% |

| 1920 | 313٬444 | +9.9% |

| 1925 | 335٬040 | +6.9% |

| 1930 | 361٬200 | +7.8% |

| 1933 | 348٬720 | −3.5% |

| 1935 | 341٬050 | −2.2% |

| 1940 | 332٬200 | −2.6% |

| 1945 | 243٬613 | −26.7% |

| 1950 | 293٬373 | +20.4% |

| 1955 | 290٬153 | −1.1% |

| 1960 | 286٬329 | −1.3% |

| 1965 | 295٬160 | +3.1% |

| 1970 | 299٬411 | +1.4% |

| 1975 | 305٬113 | +1.9% |

| 1980 | 317٬644 | +4.1% |

| 1985 | 315٬452 | −0.7% |

| 1990 | 294٬244 | −6.7% |

| 1995 | 266٬737 | −9.3% |

| 2000 | 259٬246 | −2.8% |

| 2005 | 246٬587 | −4.9% |

| 2010 | 243٬248 | −1.4% |

| 2015 | 248٬645 | +2.2% |

| 2018 | 247٬237 | −0.6% |

| 2020 | 244٬401 | −1.1% |

After German reunification Saxony faced a significant population decrease. Since 1988 Chemnitz has lost about 20 percent of its inhabitants. The city had a fertility rate of 1.64 in 2015.[30]

Foreign population in Chemnitz by nationality as of 31 December 2019:[بحاجة لمصدر]

| الترتيب | الجنسية | Population (31.12.2019) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2,915 | |

| 2 | 1,460 | |

| 3 | 1,240 | |

| 4 | 1,225 | |

| 5 | 1,145 |

A large contributor to the city's foreign population is Chemnitz University of Technology. In 2017, out of its 10,482 students, 2712 were foreign students, which equals to about 25%, making Chemnitz the most internationalised of the three major universities of Saxony.[31]

اللغات

- Standard German

- Chemnitz dialect, which is a variety of Upper Saxon German[32]

النقل

الطرق

Chemnitz is linked to two motorways (Autobahns), A4 Erfurt – Dresden and A72 Hof – Leipzig. The motorway junction Kreuz Chemnitz is situated in the northwestern area of the city. The motorway A72 between Borna and Leipzig is still under construction. Within the administrative area of Chemnitz there are eight motorway exits (Ausfahrt). The A4 motorway is part of the European route E40, one of the longest European E roads, connecting Chemnitz with the Asian Highway system to the east and France to the west.

Public transport

Public transport within Chemnitz is provided with tram and bus, as well as by the Stadtbahn. Nowadays, the city and its surroundings are served by one Stadtbahn line, five lines of the Chemnitz tramway network, 27 city bus lines, as well as several regional bus lines. At night, the city is served by two bus lines, two tram lines, and the Stadtbahn line.

Chemnitz Hauptbahnhof is the main station for the city. In June 2022, an intercity connection from Chemnitz via Dresden and Berlin to Rostock-Warnemünde was established again for the first time since 2006. Prior to this, Chemnitz was for a long time the largest German city without a connection of long-distance intercity services. 2 RegionalExpress routes connected Chemnitz to the larger cities of Saxony (RE3 from Dresden Hbf via Chemnitz to Hof & RE6 to Leipzig Hbf). In addition, 4 RegionalBahn and 4 CityBahn routes also operate from the Hauptbahnhof.

The length of the tram, Stadtbahn and bus networks is 28.73 km (17.85 mi), 16.3 km (10.13 mi) and 326.08 km (202.62 mi) respectively. In August 2012, electro-diesel trams were ordered from Vossloh, to support an expansion of the light rail network to 226 km (140 mi), with new routes serving Burgstädt, Mittweida and Hainichen.[33]

المطارات

Three airports are near Chemnitz, including the two international airports of Saxony in Dresden and Leipzig. Both Leipzig/Halle Airport and Dresden Airport are about 70 km (43 mi) from Chemnitz and offer numerous continental as well as intercontinental flights.

Chemnitz also has a small commercial airport (Flugplatz Chemnitz-Jahnsdorf about 13.5 km (8.4 mi) south of the city. When its current upgrade is completed it will have an asphalt runway 1,400 m (4,600 ft) long and 20 m (66 ft) wide.

Chemnitz Hauptbahnhof, the main train station of Chemnitz

الرياضة

- BV Chemnitz 99 (basketball, men)

- Chemnitzer FC (football)

- Chemnitzer PSV (football, handball, volleyball)

- Chemcats Chemnitz (basketball, women)

- VfB Fortuna Chemnitz (football)

- Post SV Chemnitz (swimming)

- Schwimmclub Chemnitz v. 1892 e.V. (swimming)

- TSV Einheit Süd Chemnitz (swimming, gymnastics, volleyball, skittles)

- ERC Chemnitz e.V. (ice hockey, skater hockey)

- CTC-Küchwald (tennis)

- Floor Fighters Chemnitz (floorball)

- ESV LOK Chemnitz (luge)

- Chemnitzer EC (figure skating, ice dancing, curling)

- Chemnitz Crusaders (American football)

- Tower Rugby Chemnitz (rugby)

- SV Eiche Reichenbrand (football)

- USG Chemnitz e.V. abt Cricket Club (cricket)[34]

أشخاص بارزون

- Paul Oswald Ahnert (1897–1989), astronomer

- Brigitte Ahrens (born 1945), pop singer

- Olaf Altmann (born 1960), scenic designer

- Mark Arndt (born 1941), Russian Orthodox Archbishop

- Michael Ballack (born 1976), German footballer, former captain of Bayern Munich and Germany

- Veronika Bellmann (born 1960), politician

- Fritz Bennewitz (1926–1995), theater director

- Gerd Böckmann (born 1944), television actor and director

- Werner Bräunig (1934–1976), writer

- Marianne Brandt (1893–1983), artist, designer

- Valery Bykovsky (1934–2019), Soviet cosmonaut

- C418 (real name Daniel Rosenfeld, born 1989), music producer and sound engineer for Minecraft and Stranger Things

- Hans Carl von Carlowitz (1645–1714), forest scientist

- Max Eckert-Greifendorff (1868–1938), cartographer and professor

- Gerson Goldhaber (1924–2010), American nuclear and astrophysicist

- Friedrich Goldmann (1941–2009), composer and conductor

- Carl Hahn (1926–2023), businessman, head of the Volkswagen Group

- Johannes Hähle (1906–1944), military photographer

- Peter Härtling (born 1933), writer

- Frank Heinrich (born 1964), politician, member of the Bundestag

- Stephan Hermlin (1915–1997), writer

- Stefan Heym (1913–2001), writer and member of the Bundestag of the PDS

- Christian Gottlob Heyne (1729–1812), classical scholar and archaeologist

- Sigmund Jähn (1937–2019), first German astronaut (Interkosmos flight of August 26, 1978)

- John Kluge (1921–2010), German-American billionaire and media mogul

- Helga Lindner (born 1951), swimmer; Olympic silver medalist

- Max Littmann (1862–1931), architect

- Anja Mittag (born 1985), footballer, World Champion 2007

- Frederick and William Nevoigt[de], founders of the Diamant bicycle brand

- Carsten Nicolai (born 1965), contemporary artist

- Frei Otto (1925–2015), architect, architectural theorist and professor of architecture, builder of the Munich Olympic Park

- Sylke Otto (born 1969), luge

- Siegfried Rapp (1917–1977), one-armed German pianist

- Frederick Emil Resche (1966–1946), U.S. Army brigadier general[35]

- Frank Rost (born 1973), retired football goalkeeper

- Bruno Salzer (1859–1919), one of Chemnitz's leading entrepreneurs

- Aliona Savchenko, ice figure skater

- Helmut Schelsky (1912–1984), sociologist and university lecturer

- Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884–1976), painter and graphic artist of expressionism

- Maria Schüppel (1923-2011), composer and pioneering music therapist

- Matthias Schweighöfer (born 1981), actor and film director

- Jörg Schüttauf (born 1961), actor

- Nadja Stefanoff (born 1983), soprano

- Matthias Steiner (born 1982), German-Austrian weightlifter, Olympic gold medalist 2008

- Ingo Steuer (born 1966), figure skater

- Robin Szolkowy, ice figure skater

- Hans-Günther Thalheim (1924-2018), germanist and linguist

- Siegfried Vogel (born 1937), operatic bass

- Kurt Wagner (1904–1989), German general

- Katarina Witt (born 1965), figure skater

- Mandy Wötzel (born 1973), figure skater

- Klaus Wunderlich (1931–1997), organist

البلدات التوأم – المدن الشقيقة

كمنتس متوأمة مع:

|

|

المراجع

- ^ أ ب Wahlergebnisse 2020, Freistaat Sachsen, accessed 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Chemnitz: Kulturhauptstadt mit Hindernissen". tagesschau.de (in الألمانية). Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 2021-12-21.

- ^ Agricola, Georgius. De re metallica. translation by Hoover, Herbert Clark and Hoover, Lou Henry, 1912, reprinted by Dover Publications, New York, 1950, pp. vi-xii.

- ^ Broué, Pierre (2006). The German Revolution: 1917 - 1923. Haymarket Books. p. 305. ISBN 1-931859-32-9.

- ^ W. Berthold, 'Die Kämpfeti der Chemnitzer Arbeiter gegen die militaristiche Reaktion im August 1919', Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung, no. 1, 1962, p. 127.

- ^ "Western Europe 1939–1945: Hamburg - Why did the RAF bomb cities?". The National Archives.

- ^ Victor, Edward. "Chemnitz, Germany". Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ "Graduate Computing Resources - Department of Computer Science". paul.rutgers.edu.

- ^ Travel Guide, German Democratic Republic. Dresden: Zeit im Bild Publishing House. 1983. p. 89.

The town...was renamed Karl-Marx-Stadt in 1953 to commemorate the 135th anniversary of the birth and 70th anniversary of the death of...Karl Marx

- ^ Chemnitzer Tourismus-Broschüre, Herausgeber: City-Management und Tourismus Chemnitz GmbH, 4. Jahrgang • Ausgabe 12 • Sommer 2010 Archived 26 أغسطس 2010 at the Wayback Machine; O-Ton-Nachweis im Chemnitzer Stadtarchiv[dead link]

- ^ "East Germany invited to join EC Dublin summit", The Times page 9, 2 June 1990

- ^ أ ب "Kurzfassung zur Promotion des Dipl.-Pol. Alexander Bergmann zur Thematik 'Deutschlands jüngste Innenstadt – Rekonstruktion in Chemnitz verstehen'"

- ^ Dankwart Guratzsch: "Einer Stadt die Zähne herausgebrochen", Die Welt, 12 May 2006.

- ^ Gudrun Müller: "Der Abrissrausch ist tödlich für Chemnitz", Freie Presse, 7 December 2006.

- ^ Bennhold, Katrin (31 August 2018). "Chemnitz Protests Show New Strength of Germany's Far Right". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2018-08-31.

- ^ Eddy, Melissa (28 August 2018). "German Far Right and Counterprotesters Clash in Chemnitz". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2018-08-31.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (2018-08-28). "German police criticised as country reels from far-right violence". the Guardian (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ^ Times, Oliver Moody, Berlin | The (2018-09-02). "Germany: Weekend of riots as thousands clash at far-right march in Chemnitz". The Sunday Times (in الإنجليزية). ISSN 0956-1382. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Original wording: "Es gab, nach allem, was man weiss, lediglich vereinzelte Übergriffe, aber keine grossangelegte Menschenjagd (auch die NZZ hat hierüber zunächst in unzutreffender Weise berichtet)."". NZZ (in الألمانية). 2018-09-03. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- ^ "Sachsens Ministerpräsident Kretschmer: "Es gab keinen Mob, keine Hetzjagd" - Freie Presse - Sachsen".

- ^ "Original wording: "65.000 bei Konzert gegen Rechts"".

- ^ "Original wording: "Totschlag in Chemnitz: Was wir über Tatverdächtige und Opfer Daniel H. wissen"".

- ^ "Original wording: "Die ostdeutsche Punkband Feine Sahne Fischfilet wurde jahrelang vom zuständigen Verfassungsschutz in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern beobachtet und tauchte unter dem Stichwort Linksextremismus (Rubrik: Autonome Antifa-Strukturen) in den Berichten der Staatsschützer auf."". NZZ (in الألمانية). 2018-09-03. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- ^ "Original wording: "27 Minuten Hass auf Veranstaltung gegen Hass"". Bild (in الألمانية). 2018-09-27.

- ^ A3, EAC (2020-10-28). "Chemnitz to be the European Capital of Culture 2025 in Germany". Creative Europe - European Commission (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-10-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Chemnitz, Staatliches Museum für Archäologie. "Staatliches Museum für Archäologie Chemnitz". www.smac.sachsen.de.

- ^ "Hauptsatzung der Stadt Chemnitz" (PDF). Hauptsatzung der Stadt Chemnitz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-29. Retrieved 2019-08-30. (PDF; 75 KB)

- ^ Baden-Württemberg, Statistisches Landesamt. "Aktuelle Ergebnisse – VGR dL". www.statistik-bw.de (in الألمانية). Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 2018-09-08.

- ^ "Detlef Müller". 28 September 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ "Statistisches Jahrbuch 2015/2016" (PDF) (in الألمانية). chemnitz.de. 29 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Statistical Office of Saxony, Statistical data of June 2018 for academic winter term 2017" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-28.

- ^ Khan, Sameer ud Dowla; Weise, Constanze (2013), "Upper Saxon (Chemnitz dialect)", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 43 (2): 231, doi:, http://academic.reed.edu/linguistics/khan/assets/Khan%20Weise%202013%20Upper%20Saxon%20Chemnitz%20dialect.pdf

- ^ "Chemnitz orders electro-diesel tram-trains". Railway Gazette International. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ "Chemnitz Cricket Club". USG Chemnitz e.V. abt Cricket Club. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Davis, Henry Blaine Jr. (1998). Generals in Khaki. Raleigh, NC: Pentland Press. pp. 306–307. ISBN 978-1-5719-7088-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Medmestno in mednarodno sodelovanje". Mestna občina Ljubljana (Ljubljana City) (in Slovenian). Archived from the original on 26 يونيو 2013. Retrieved 27 يوليو 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Miasta partnerskie – Urząd Miasta Łodzi [via WaybackMachine.com]". City of Łódź (in Polish). Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Twin Towns". www.amazingdusseldorf.com. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

ببليوجرافيا

- See also: Bibliography of the history of Chemnitz

انظر أيضاً

وصلات خارجية

Media related to Chemnitz at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chemnitz at Wikimedia Commons The Wiktionary definition of كمنتس

The Wiktionary definition of كمنتس كمنتس travel guide from Wikivoyage

كمنتس travel guide from Wikivoyage- (بالألمانية) Official website

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Articles with dead external links from August 2017

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Germany articles requiring maintenance

- Pages using infobox German location with unknown parameters

- البلديات in Saxony

- Articles containing صوربية عليا-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with text in Slavic languages

- Articles containing تشيكية-language text

- Articles containing پولندية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2018

- Articles containing Upper Saxon-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2020

- Pages with empty portal template

- كمنتس

- مدن ساكسونيا

- حملة النفط في الحرب العالمية الثانية

- بلدات جامعية في ألمانيا

- مملكة ساكسونيا

- Bezirk Karl-Marx-Stadt

- صفحات مع الخرائط