قومان

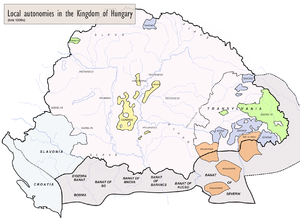

القومان (Cumans ؛ پولوڤتسي Polovtsi) كانوا شعب بدوي رحال توركي[1][2][3][4] يتألف من الفرع الغربي من اتحاد القومان-القپچاق. وبعد الغزو المنغولي (1237)، طلب الكثير منهم اللجوء في المجر،[5] كما أن عددا مماثلاً من القومان كان قد استقر في المجر وبلغاريا والأناضول قبل الغزو.[6][7][8]

ولقرابتهم للپچنگ,[9] فقد استوطنوا منطقة متنقلة شمال البحر الأسود وبحذى نهر ڤولگا تـُعرف بإسم قومانيا، حيث تدخل القومان-القپچاق في سياسة القوقاز والدولة الخوارزمية.[7] وكان القومان مقاتلين أشداء مرهوبي الجانب في سهوب أوراسيا ، وكان لهم أثر باقٍ على البلقان القروسطي.[10][11] وكان تعدادهم كبير وثقافتهم متقدمة وجيوشهم قوية.[12]

وفي آخر الأمر استقر عدد كبير منهم غرب البحر الأسود، فأثروا على سياسات روس الكييڤية، إمارة گاليسيا-ڤولهينيا، خانية القبيل الذهبي، الامبراطورية البلغارية الثانية، مملكة صربيا ومملكة المجر ومولداڤيا، مملكة جورجيا، الامبراطورية البيزنطية، امبراطورية نيقيا، و الامبراطورية اللاتينية ووالاخيا، من خلال المهاجرين القومان الذين اندمجوا في نخبة كل من تلك الدول.[8] كما لعب القومان دوراً بارزاً في الحملة الصليبية الرابعة وفي إنشاء الامبراطورية البلغارية الثانية.[7][13] اتحدت قبائل القومان والقپچاق سياسياً لتشكل اتحاد القومان-قپچاق.[12]

لغة القومان مذكورة في بعض الوثائق القروسطية وهي من أشهر اللغات التوركية المبكرة.[4] Codex Cumanicus كان مرجعاً لغوياً كـُتـِب لمساعدة المنصرين الكاثوليك في التواصل مع شعب القومان.

الأداة الأساسية للنجاح السياسي للقومان كان القوة العسكرية، التي سيطرت على كل من الفصائل المتناحرة في البلقان. استقرت جماعات القومان واختلطت مع السكان المحليين في أرجاء البلقان، وأسس المستوطنون القومان ثلاث أسر حاكمة بلغارية متتالية (Asenids وTerterids و Shishmanids) وأسرة ولاخية (البسارابيين);[7][8][13][14][15] إلا أنه في حالات الأسر الحاكمة من البساراب والآسن، فإن وثائق العصور الوسطى تشير إليهم بأنهم أسر حاكمة من الڤلاخ (الرومانيين).[16][17]

أسماء وأصولها

- Turkish and Azeri: Kuman, plural: Kumanlar;[18]

- مجرية: Kunok;[1]

- باليونانية: [Κο[υ]μάνοι, Ko[u]mánoi] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help);[19]

- Kazakh: Қыпшақтар, Qıpşaqtar, قىپشاقتار;

- اوزبكية: Qipchoqlar, Қипчоқлар;

- بالچواشية: Кăпчаксем, Kăpçaksem;

- بالتتارية: Команнар/Кыпчаклар, Qomannar/Qıpçaqlar;

- بالبشكيرية: Ҡыпсаҡтар/ҡомандар, Qıpsaqtar/qomandar;

- لاتينية: Pallidi, Comani, Cuni;[20]

- رومانية: Cumani;

- پولندية: Połowcy, Plauci (Kumanowie);

- روسية: Половцы, Polovtsy;

- أوكرانية: Половці, Polovtsi;

- بالبيلاروسية: По́лаўцы/кыпчакі/куманы, Poławcy/kypčaki/kumany;

- Bulgarian, Serbian and Macedonian: Кумани, Kumani;

- Croatian: Kumani

- Czech: Plavci;

- بالجورجية: ყივჩაყი, ყიფჩაღი, Qivçaqi, Qipçaḡi;

- German: Falones, Phalagi, Valvi, Valewen, Valani

The original meaning of the endonym Cuman is unknown. It is also often unclear whether a particular name refers to the Cumans alone, or to both them and the Kipchaks, as the two tribes often lived side by side.[7] However, in Turkic languages qu, qun, qūn, quman or qoman means "pale, sallow, cream coloured", "pale yellow", or "yellowish grey".[21][22] While it is normally assumed that the name referred to the Cumans's hair, Imre Baski – a prominent Turkologist – has suggested that it may have other origins, including:

- the color of the Cumans' horses (i.e. cream tones are found among Central Asian breeds such as the Akhal-Teke);

- a traditional water vessel, known as a quman, or;

- a Turkic word for "force" or "power".[23]

In East Slavic languages and Polish, they are known as the Polovtsy, derived from the Slavic root *polvъ "pale; light yellow; blonde".[24][25] Polovtsy or Polovec is often said to be derived from the Old East Slavic polovŭ (половъ) "yellow; pale" by the Russians – all meaning "blond".[25] The old Ukrainian word polovtsy (Пóловці), derived from polovo "straw" – means "blond, pale yellow". The western Cumans, or Polovtsy, were also called Sorochinetses by the Rus', – apparently derived from the Turkic sary chechle "yellow-haired". A similar etymology may have been at work in the name of the Sary people, who also migrated westward ahead of the Qun.[26][استشهاد ناقص] However, according to O. Suleymenov polovtsy may come from a Slavic word for "blue-eyed", i.e. the Serbo-Croatian plȃv (пла̑в) means "blue",[27] but this word also means "fair, blonde" and is in fact a cognate of the above; cf. Eastern Slavic polovŭ, Russian polóvyj (поло́вый), Ukrainian polovýj (полови́й).[28] An alternative etymology of Polovtsy is also possible: the Slavic root *pȍlje "field" (cf. Russian póle), which would therefore imply that Polovtsy were "men of the field" or "men of the steppe".

In Germanic languages, the Cumans were called Folban, Vallani or Valwe – all derivations of old Germanic words for "pale".[4] In the German account by Adam of Bremen, and in Matthaios of Edessa, the Cumans were referred to as the "Blond Ones".[24]

The Hungarian term for the Cumans is Kun (also Qoun; Kunok), which in Old Hungarian meant "nomad", but was later applied solely to the Cumans.[29]

As stated above, it is unknown whether the name Kipchak referred only to the Kipchaks proper, or to the Cumans as well. The two tribes eventually fused, lived together and probably exchanged weaponry, culture and languages; the Cumans encompassed the western half of the confederation, while the Kipchaks and (presumably) the Kangli/Kankalis (a ruling clan of the Pechenegs) encompassed the eastern half.[7]The word Kipchak is said to be derived from the Iranian words kip "red; blonde" and cak/chak "Scythian".[30] This confederation and their living together may have made it difficult for historians to write exclusively about either nation.

The member clans of the Cumans and/or Kipchaks were: the Terteroba (Ter'trobichi), Etioba/Ietioba, Kay, Itogli, Kochoba (meaning "Ram Clan"), Urosoba, El'Borili, Kangarogli, Andjogli, Durut, Djartan, Karabirkli, Kotan/Hotan, Kulabaogli, Olelric, Altunopa ("Gold Clan"), Toksobychi, Burchevychi, Ulashevichi (Ulash-oghlu), Chitieevichi, Elobichi, Kolabichi, Etebichi, Yeltunovychi, Yetebychi, Berish, Olperliuve (Olperlu), Emiakovie (Yemek), Phalagi, Olberli, Toksobichi or Toqsoba (meaning either "plump leather bottle" or "nine clans"), Borchol or Burdjogli ("Pepper Sons"), Csertan or Curtan ("pike"), Olas or Ulas ("union; federation"), Kor or Kol ("little; few"), Ilunesuk ("little snake") and Koncsog. The latter seven clans eventually settled in Hungary.[8][21]

التاريخ

الأصول

The ethnic origins of the Cumanians are uncertain.[20][8][31][need quotation to verify] The Cumans were reported to have had blond hair, fair skin and blue eyes (which set them apart from other groups and later puzzled historians),[13][25][32] although their anthropological characteristics suggest that their geographical origin might be in Inner-Asia, South-Siberia, or (as Istvan Vassary postulates) east of the large bend of the Yellow River in China.[6][7][33][34] Robert Wolff states that it is conjectured[ممن؟] that ethnically the Cumans may not originally have been Turkic.[35] The Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder (who lived in the 1st century AD), in describing the "Gates of Caucasus" (Derbent, or Darial Gorge), mentions "a fortress, the name of which is Cumania, erected for the purpose of preventing the passage of the innumerable tribes that lay beyond".[36] The Greek philosopher Strabo (died ح. 24 AD) refers to the Darial Gorge (also known as the Iberian Gates or the Caucasian Gates) as Porta Caucasica and Porta Cumana.[37] The writings of al Marwazi (c. 1120) state that the "Qun" people (as the Cumans were called in Hungary) came from the northern Chinese borders – "the land of Qitay" (possibly during a part of a migration from further east). After leaving the lands of the Khitans (possibly due to Kitai expansion[35]), they entered the territory of the Shari/Sari people. Marwazi wrote that the Qun were Nestorian Christians.[38]

It cannot be established whether the Cumans conquered the Kipchaks or whether they simply represent the western mass of largely Kipchak-Turkic speaking tribes. A "victim" of the Cuman migration to the west was the Kimek Khanate (743-1220), which dissolved but then regrouped under Kipchak-Cuman leadership.[بحاجة لمصدر] Due to this, Kimek tribal elements were represented amongst the Cuman-Kipchaks. The Syrian historian Yaqut (1179–1229) also mentions the Qun in The Dictionary of Countries, where he notes that "(the sixth iqlim) begins where the meridian shadow of the equinox is seven, six-tenths, and one-sixth of one-tenth of a foot. Its end exceeds its beginning by only one foot. It begins in the homeland of the Qani, Qun, Khirkhiz, Kimak, at-Tagazgaz, the lands of the Turkomans, Fārāb, and the country of the Khazars."[8][39] The Armenian historian, Matthew of Edessa (died 1144), also mentioned the Cumans, using the name χartešk (khartes, meaning "blond", "pale", "fair").[40][41]

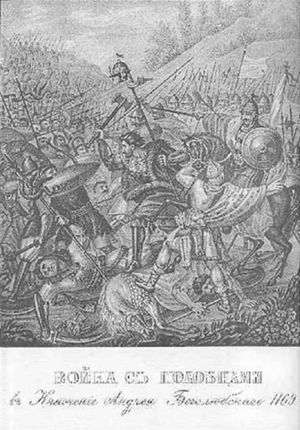

The Cumans entered the grasslands of the present-day southern Russian steppe in the 11th century AD and went on to assault the Byzantine Empire, the Kingdom of Hungary, the Principality of Pereyaslavl and Kievan Rus'. The Cumans' entry into the area pressed the Oghuz Turks to shift west, which in turn caused the Pechenegs to move to the west of the Dnieper River.[4] Cuman and Rus' attacks contributed to the departure of the Oghuz from the steppes north of the Black Sea.[4] The Cumans first entered the Bugeac (Bessarabia) at some point around 1068–1078. They launched a joint expedition with the Pechenegs against Adrianople in 1078. During that same year the Cumans were also fighting the Rus'.[4] The Russian Primary Chronicle mentions Yemek Cumans who were active in the region of Volga Bulgaria.[8]

The vast territory of the Cuman-Kipchak realm consisted of loosely connected tribal units that represented a dominant military force but were never politically united by a strong central power; the khans acted on their own initiative. The Cuman-Kipchaks never established a state, instead forming a Cuman-Kipchak confederation (Cumania/Desht-i Qipchaq/Zemlja Poloveckaja(Polovcian Land)/Pole Poloveckoe(Polovcian Plain),[7] التي امتدت من الدانوب في الغرب إلى Taraz, قزخستان في الشرق.[8] This was possibly due to their facing no prolonged threat before the Mongol invasion, and it may have either prolonged their existence or quickened their destruction.[42] Robert Wolff states that it was discipline and cohesion that permitted the Cuman-Kipchaks to conquer such a vast territory.[35] al-Idrīsī states that Cumania got its name from the city of Cumania; he wrote, "From the city of Khazaria to the city of Kirait is 25 miles. From there to Cumanie, which has given its name to the Cumans, it is 25 miles; this city is called Black Cumania. From the city of Black Cumania to the city of Tmutorakan (MaTlUqa), which is called White Cumania, it is 50 miles. White Cumania is a large inhabited city...Indeed, in this fifth part of the seventh section there is the northern part of the land of Russia and the northern part of the land of Cumania...In this sixth part there is a description of the land of Inner Cumania and parts of the land of Bulgaria."[43]

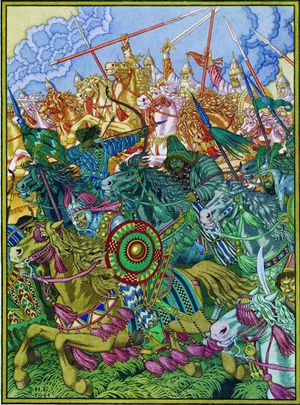

معارك في روس الكييڤية والبلقان

الغزوات المنغولية

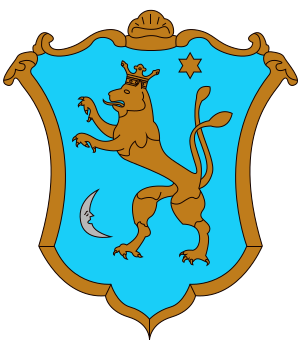

الاستقرار في السهل المجري

انخراط القومان في صربيا

القبيل الذهبي ومرتزقة للبيزنطيين

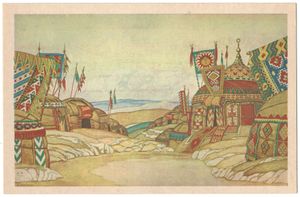

الثقافة

التكتيكات العسكرية

الدين

The Cumans practiced Shamanism and Tengrism. Their belief system had animistic and shamanistic elements; they celebrated the cult of ancestors and provided the dead with objects whose lavishness paralleled the recipient's social rank.

Codex Cumanicus

The Codex Cumanicus, which was written by Italian merchants and German missionaries between 1294 and 1356,[40] was a linguistic manual for the Turkic Cuman language of the Middle Ages, designed to help Catholic missionaries communicate with the Cumans.[44] It consisted of a Latin-Persian-Cuman glossary, grammar observations, lists of consumer goods and Cuman riddles.[40][44]

خانات الپولوڤتسي (التآريخ الروذينية)

- Iskal or Eskel (possibly a self-name of a Bulgaric tribe (Nushibi)) who were mentioned by أحمد بن فضلان after visiting Volga region in 921–922. They also were mentioned by Abu Saʿīd Gardēzī in his Zayn al-Akhbār. According to Bernhard Karlgren, Eskels became the شعب المجر Székelys. Yury Zuev thought that Iskal who is mentioned in the Laurentian Codex about the first military encounter of Cumans against the Ruthenians on February 2, 1061, is personification of a tribal name.

علم الوراثة

Gallery

Kunkereszt ("Cuman cross") in Belez, periphery of Magyarcsanád, Hungary

Cuman prairie art, as exhibited in Dnipropetrovsk

Cuman stone statues in Donetsk damaged in fighting (22 September 2014)

See also

- Notable people of Cuman descent

- Cumania

- The Cuman Tsaritsa of Bulgaria

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Cumania

- Kuns

- Kumandins – a branch of the Cumans that still exists up to this day, in Siberia

- Terter clan

- Delhi Sultanate – Qutb ad-Din Aibeg, founder of the Delhi sultanate, was a Cuman; redeemed from slavery by Afghan shakh Mahmud Ghuri, he became his governor in Delhi and proclaimed independence after the death of his patron.

- Igor Svyatoslavich

- Kipchak

- Nomad

- Kumyks

- Crimean Tatars

- Pechenegs

- Komnenos dynasty

- Komnina (Kozani), Greece

- Turkic peoples

- Turkic languages

- Battle of the Kalka River

- Mongol invasion of Rus

- David IV of Georgia

- Tatar invasions

- Battle of the Stugna River

- Battle of Levounion

- Köten

- List of Tatar and Mongol raids against Rus'

- Mongol invasion of Europe

- History of Romania

- Crimean Karaites, an ethnic group with possible Cuman origins

- Kunság

- Bács-Kiskun County

- Kaloyan

- Cuman language

- Crimean Tatar language – possibly similar to the Cuman language

- Baibars

- Béla IV of Hungary

- Romania in the Early Middle Ages

- Stephen V of Hungary

- Foundation of Wallachia

- Battle of Adrianople (1205)

- Kunság

- Constantine Euphorbenos Katakalon

- Terter dynasty

- Basarab I of Wallachia

- Origin of the Romanians

- Anna of Hungary (1260–1281)

- Yaropolk II of Kiev

- Darman and Kudelin – Bulgarians of Cuman origin

- Elizabeth of Sicily, Queen of Hungary (Trouble with Cumans)

- Elizabeth of Hungary, Queen of Serbia -one of the older children of King Stephen V of Hungary and his wife Elizabeth the Cuman

- Kumani Supporters Ultras group from Macedonia

- Shishman of Vidin (Shishman dynasty of the Second Bulgarian Empire is most probably of Cuman origin)

- Roman the Great – he waged two successful campaigns against the Cumans

- Ladislaus IV of Hungary – he was also known as King Ladislas the Cuman, son of Elizabeth the Cuman

- History of Transylvania

- Asen dynasty – dynasty of the Second Bulgarian Empire. Historians claim a Bulgarian, Romanian or Cuman origin

- Madjars

Notes

- ^ أ ب Encyclopædia Britannica Online - Cuman

- ^ Robert Lee Wolff: "'الامبراطورية البلغارية الثانية.' Its Origin and History to 1204" Speculum, Volume 24, Issue 2 (April 1949), 179; "Thereafter, the influx of الپچنگ and Cumans turned Bulgaria into a battleground between Byzantium and these Turkish tribes..."

- ^ Bartusis, Mark C. (1997). The Late Byzantine Army: Arms and Society, 1204–1453. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-8122-1620-2.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ "Cuman (people)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ أ ب "Mitochondrial-DNA-of-ancient-Cumanians". Goliath.ecnext.com. Archived from the original on 2010-01-24. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Vásáry, István (2005). Cumans and Tatars Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5218-3756-9.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Sinor, Sinor, ed. (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5212-4304-9.

- ^ "Cumans". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ^ Bartlett, W. B. (2012). The Mongols: From Genghis Khan to Tamerlane. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-0791-7.

- ^ Prawdin, Michael (1940). The Mongol Empire: Its Rise and Legacy. Transaction Publishers. pp. 212–15. ISBN 978-1-4128-2897-0. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ أ ب Nicolle, David; Shpakovsky, Victor (2001). Kalka River 1223: Genghiz Khan's Mongols Invade Russia. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-233-3.

- ^ أ ب ت Grumeza, Ion (4 August 2010). The Roots of Balkanization: Eastern Europe C.E. 500–1500. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-5135-6.

- ^ Rădvan, Laurențiu (1 January 2010). At Europe's Borders: Medieval Towns in the Romanian Principalities. BRILL. p. 129. ISBN 90-04-18010-9. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Krüger, Peter (1993). Ethnicity and nationalism: case studies in their intrinsic tension and political dynamics. Hitzeroth. p. 32. ISBN 978-3-89398-128-1. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ For example: "Bazarab infidelis Olacus noster", "Basarab Olacus et filii eiusdem", "Bazarab filium Thocomerius scismaticum olachis nostris." http://www.arcanum.hu/mol/lpext.dll/fejer/152e/153a/1654?fn=document-frame.htm&f=templates&2.0

- ^ Stephenson, Paul (2000). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5217-7017-0.

- ^ Loewenthal, Rudolf (1957). The Turkic Languages and Literature of Central Asia: A Bibliography. Mouton. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, p. 563

- ^ أ ب Paksoy, H. B., ed. (1992). Central Asian Monuments. ISIS Press. ISBN 978-975-428-033-3.

- ^ أ ب Boĭkova, Elena Vladimirovna; Rybakov, R. B. (2006). Kinship in the Altaic World. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-4470-5416-4.

- ^ Khazanov, Anatoly M.; Wink, André, eds. (2001). Nomads in the Sedentary World. Psychology Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7007-1370-7.

- ^ Imre Baski, "On the ethnic names of the Cumans of Hungary", Kinship in the Altaic World: Proceedings of the 48th Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Moscow 10–15 July 2005 (eds Elena V. Boikova, Rosislav B. Rybakov) Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 48, 52.

- ^ أ ب Justin Dragosani-Brantingham (19 October 2011) [1999]. "An Illustrated Introduction to the Kipchak Turks" (PDF). kipchak.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-30. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب ت Nicolle, David; McBride, Angus (1988). Hungary and the Fall of Eastern Europe 1000–1568. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8504-5833-6. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Dobrodomov I.G., 1978, 123

- ^ Ignjatić, Zdravko (2005). ESSE English-Serbian Serbian-English Dictionary and Grammar. Belgrade, Serbia: Institute for Foreign Languages. p. 1033. ISBN 867147122-5.

- ^ Rick Derksen, Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon (Brill: Leiden-Boston, 2008), 412.

- ^ István Vásáry, Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p. 5.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz (2012). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-2302-9473-8.

- ^ H. B. Paksoy, ed. (1992). Codex Cumanicus - Central Asian Monuments. CARRIE E Books. ISBN 975-428-033-9. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ MacDermott, Mercia (1998). Bulgarian Folk Customs. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-8530-2485-6.

- ^ Paloczi Horvath 1998, 2001.

- ^ Erika Bogácsi-Szabó (2006). "Population genetic and diagnostic mitochondrial DNA and autosomal marker analysis of ancient bones excavated in Hungary and modern examples" (PDF). University of Szeged. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ أ ب ت Wolff, Robert Lee (1976). Studies in the Latin Empire of Constantinople. London: Variorum. ISBN 978-0-9020-8999-0.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, The Natural History of Pliny Volume 2, p. 21.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Darial". دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 7 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 832.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Minorsky, V. (1942), Sharaf al-Zaman Tahir Marvazī on China, the Turks and India. Arabic text (circa A.D. 1120) with an English translation and commentary. London. 1, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Yaqut, Kitab mu'jam al-budan, p. 31.

- ^ أ ب ت Kincses-Nagy,, Éva (2013). A Disappeared People and a Disappeared Language: The Cumans and the Cuman language of Hungary. Szeged University.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Spinei, Victor. The Great Migrations in the East and South East of Europe from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century: Cumans and Mongols. p. 323. ISBN 978-9-0256-1214-6.

- ^ Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. p. 277. ISBN 978-3-4470-3274-2.

- ^ Drobny, Jaroslav. Cumans and Kipchaks: Between Ethnonym and Toponym. p. 208.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBaldick2012

للاستزادة

- (بالروسية) Golubovsky Peter V. (1884) Pechenegs, Torks and Cumans before the invasion of the Tatars. History of the South Russian steppes in the 9th-13th Centuries (Печенеги, Торки и Половцы до нашествия татар. История южно-русских степей IX–XIII вв.) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format.

- (بالروسية) Golubovsky Peter V. (1889) Cumans in Hungary. Historical essay (Половцы в Венгрии. Исторический очерк) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format.

- István Vásáry (2005) "Cumans and Tatars", Cambridge University Press.

- Gyárfás István: A Jászkunok Története

- Györffy György: A Codex Cumanicus mai kérdései

- Györffy György: A magyarság keleti elemei

- Hunfalvy: Etnographia

- Perfecky (translator): Galician-Volhynian Chronicle

- Stephenson, Paul. Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204, Cambridge University Press, 2000

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Articles containing مجرية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Lang and lang-xx template errors

- Articles containing أوزبكية-language text

- Articles containing چواش-language text

- Articles containing تتارية-language text

- Articles containing بشكير-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles containing رومانية-language text

- Articles containing پولندية-language text

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles containing أوكرانية-language text

- Articles containing بلاروسية-language text

- Articles containing جورجية-language text

- Articles with incomplete citations from December 2014

- All articles with incomplete citations

- Wikipedia articles needing factual verification from February 2017

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from February 2017

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using div col with unknown parameters

- قومان

- جماعات عرقية منقرضة

- تاريخ الشعوب التوركية

- Invasions of Europe

- تاريخ روس الكييڤية

- المجر القروسطية

- أوكرانيا القروسطية

- مولدوڤا في العصور الوسطى

- جماعات بدوية في أوراسيا

- رومانيا في العصور الوسطى

- قبائل توركية