الأبجدية الرونية

| Runic | |

|---|---|

| |

| النوع | Alphabet |

| اللغات | اللغات الجرمانية |

| الفترة الزمنية | Elder: ~1st–9th c. Anglo-Frisian: ~5th–9th c. Anglo-Saxon: ~9th–12th c. Younger: ~8th–11th c. Stung: ~11th–13th c. Medieval: ~13th–18th c. Dalecarlian: ~16th–19th c. |

النظم الوالدة | |

النظم الابنة | Elder Futhark Younger Futhark Anglo-Saxon futhorc |

| الاتجاه | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Runr, 211 |

مرادف اليونيكود | Runic |

| U+16A0–U+16FF[2] | |

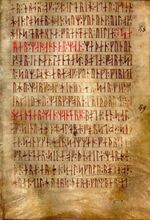

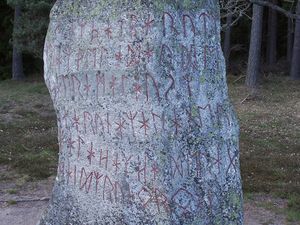

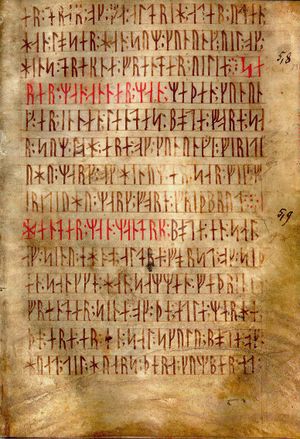

الـرون اسم يطلق على أقدم حروف الأبجدية المكتوبة التي استخدمتها الشعوب الجرمانية في أوروبا. وترجع أقدم الكتابات الرونية إلى القرن الثالث الميلادي، وقد كُتبت معظم النقوش الرونية المعروفة الآن قبل القرن الحادي عشر الميلادي. وغالبًا ما كانت تحفَر على الخشب، وإن كانت معظم النقوش الباقية مكتوبة على الحجر.

وكلمة رون مأخوذة من كلمة قوطية تعني السِّر، إذ ربط أفراد القبائل الجرمانية القديمة تلك الحروف بالأسرار المجهولة أو الدينية لأنها لم تكن مفهومة إلا للقلة، وربما استخدمها الكهنة الوثنيون في بداية الأمر لصنع التعاويذ والرقى السحرية، كما كانت الحروف تُنقش أيضًا على العملات والمجوهرات والصروح والمجاديل الحجرية أو الألواح الخشبية. وكانت الحروف الأولى تكاد تقتصر في كتابتها على الخطوط المستقيمة سواء أكانت مفردة أم مركبة من خطين أو أكثر. أما الحروف الرونية الأحدث فكانت لها أشكال أكثر تعقيدًا.

Runology is the academic study of the runic alphabets, runic inscriptions, runestones, and their history. Runology forms a specialised branch of Germanic philology.

The earliest secure runic inscriptions date from around AD 150, with a potentially earlier inscription dating to AD 50 and Tacitus's potential description of rune use from around AD 98. The Svingerud Runestone dates from between AD 1 and 250. Runes were generally replaced by the Latin alphabet as the cultures that had used runes underwent Christianisation, by approximately AD 700 in central Europe and 1100 in northern Europe. However, the use of runes persisted for specialized purposes beyond this period. Up until the early 20th century, runes were still used in rural Sweden for decorative purposes in Dalarna and on runic calendars.

The three best-known runic alphabets are the Elder Futhark (ح. AD 150–800), the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc (400–1100), and the Younger Futhark (800–1100). The Younger Futhark is divided further into the long-branch runes (also called Danish, although they were also used in Norway, Sweden, and Frisia); short-branch, or Rök, runes (also called Swedish–Norwegian, although they were also used in Denmark); and the stavlösa, or Hälsinge, runes (staveless runes). The Younger Futhark developed further into the medieval runes (1100–1500), and the Dalecarlian runes (ح. 1500–1800).

The exact development of the early runic alphabet remains unclear but the script ultimately stems from the Phoenician alphabet. Early runes may have developed from the Raetic, Venetic, Etruscan, or Old Latin as candidates. At the time, all of these scripts had the same angular letter shapes suited for epigraphy, which would become characteristic of the runes and related scripts in the region.

The process of transmission of the script is unknown. The oldest clear inscriptions are found in Denmark and northern Germany. A "West Germanic hypothesis" suggests transmission via Elbe Germanic groups, while a "Gothic hypothesis" presumes transmission via East Germanic expansion. Runes continue to be used in a wide variety of ways in modern popular culture.

الاسم

أصل الاسم

The name stems from a Proto-Germanic form reconstructed as *rūnō, which may be translated as 'secret, mystery; secret conversation; rune'. It is the source of Gothic rūna (𐍂𐌿𐌽𐌰, 'secret, mystery, counsel'), Old English rún ('whisper, mystery, secret, rune'), Old Saxon rūna ('secret counsel, confidential talk'), Middle Dutch rūne ('id'), Old High German rūna ('secret, mystery'), and Old Norse rún ('secret, mystery, rune').[5][6] The earliest Germanic epigraphic attestation is the Primitive Norse rūnō (accusative singular), found on the Einang stone (AD 350–400) and the Noleby stone (AD 450).[4]

The term is related to Proto-Celtic *rūna ('secret, magic'), which is attested in Old Irish rún ('mystery, secret'), Middle Welsh rin ('mystery, charm'), Middle Breton rin ('secret wisdom'), and possibly in the ancient Gaulish Cobrunus (< *com-rūnos 'confident'; cf. Middle Welsh cyfrin, Middle Breton queffrin, Middle Irish comrún 'shared secret, confidence') and Sacruna (< *sacro-runa 'sacred secret'), as well as in Lepontic Runatis (< *runo-ātis 'belonging to the secret'). However, it is difficult to tell whether they are cognates (linguistic siblings from a common origin), or if the Proto-Germanic form reflects an early borrowing from Celtic.[7][8] Various connections have been proposed with other Indo-European terms (for example: Sanskrit ráuti रौति 'roar', Latin rūmor 'noise, rumor'; Ancient Greek eréō ἐρέω 'ask' and ereunáō ἐρευνάω 'investigate'),[9] although linguist Ranko Matasović finds them difficult to justify for semantic or linguistic reasons.[7] Because of this, some scholars have speculated that the Germanic and Celtic words may have been a shared religious term borrowed from an unknown non-Indo-European language.[4][7]

مصطلحات ذات صلة

In early Germanic, a rune could also be referred to as *rūna-stabaz, a compound of *rūnō and *stabaz ('staff; letter'). It is attested in Old Norse rúna-stafr, Old English rún-stæf, and Old High German rūn-stab.[10] Other Germanic terms derived from *rūnō include *runōn ('counsellor'), *rūnjan and *ga-rūnjan ('secret, mystery'), *raunō ('trial, inquiry, experiment'), *hugi-rūnō ('secret of the mind, magical rune'), and *halja-rūnō ('witch, sorceress'; literally '[possessor of the] Hel-secret').[11] It is also often part of personal names, including Gothic Runilo (𐍂𐌿𐌽𐌹𐌻𐍉), Frankish Rúnfrid, Old Norse Alfrún, Dagrún, Guðrún, Sigrún, Ǫlrún, Old English Ælfrún, and Lombardic Goderūna.[9]

The Finnish word runo, meaning 'poem', is an early borrowing from Proto-Germanic,[12] and the source of the term for rune, riimukirjain, meaning 'scratched letter'.[13] The root may also be found in the Baltic languages, where Lithuanian runoti means both 'to cut (with a knife)' and 'to speak'.[14]

The Old English form rún survived into the early modern period as roun, which is now obsolete. The modern English rune is a later formation that is partly derived from Late Latin runa, Old Norse rún, and Danish rune.[6]

التاريخ والاستخدام

اكتشف علماء الآثار أكثر من أربعة آلاف نقش روني، منها عدد يربو على ثلاثة آلاف في السويد، ويعود الكثير منها إلى الفترة الممتدة من القرن التاسع إلى الحادي عشر الميلاديين، أي عصر الفايكنج. واكتشفت كتابات رونية أخرى في الدنمارك وإنجلترا وألمانيا والنرويج. وبحلول القرن الحادي عشر الميلادي كان المُنصِّرون قد نجحوا في تحويل الشعوب الجرمانية إلى النصرانية؛ مما أدى إلى دخول الأبجدية اللاتينية التي حلت، في نهاية الأمر، محل الحروف الرونية.

الأصول

The formation of the Elder Futhark was complete by the early 5th century, with the Kylver Stone being the first evidence of the futhark ordering as well as of the p rune.

Specifically, the Rhaetic alphabet of Bolzano is often advanced as a candidate for the origin of the runes, with only five Elder Futhark runes (ᛖ e, ᛇ ï, ᛃ j, ᛜ ŋ, ᛈ p) having no counterpart in the Bolzano alphabet.[15] Scandinavian scholars tend to favor derivation from the Latin alphabet itself over Rhaetic candidates.[16][17][18] A "North Etruscan" thesis is supported by the inscription on the Negau helmet dating to the 2nd century BC.[19] This is in a northern Etruscan alphabet but features a Germanic name, Harigast. Giuliano and Larissa Bonfante suggest that runes derived from some North Italic alphabet, specifically Venetic: But since Romans conquered Veneto after 200 BC, and then the Latin alphabet became prominent and Venetic culture diminished in importance, Germanic people could have adopted the Venetic alphabet within the 3rd century BC or even earlier.[20]

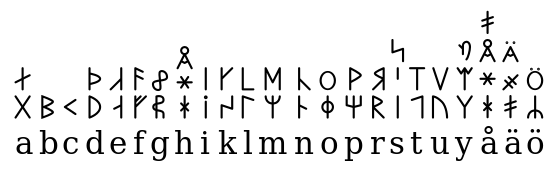

The angular shapes of the runes are shared with most contemporary alphabets of the period that were used for carving in wood or stone. There are no horizontal strokes: when carving a message on a flat staff or stick, it would be along the grain, thus both less legible and more likely to split the wood.[21] This characteristic is also shared by other alphabets, such as the early form of the Latin alphabet used for the Duenos inscription, but it is not universal, especially among early runic inscriptions, which frequently have variant rune shapes, including horizontal strokes. Runic manuscripts (that is written rather than carved runes, such as Codex Runicus) also show horizontal strokes.

The "West Germanic hypothesis" speculates on an introduction by West Germanic tribes. This hypothesis is based on claiming that the earliest inscriptions of the 2nd and 3rd centuries, found in bogs and graves around Jutland (the Vimose inscriptions), exhibit word endings that, being interpreted by Scandinavian scholars to be Proto-Norse, are considered unresolved and long having been the subject of discussion.[أ] In the early Runic period, differences between Germanic languages are generally presumed to be small. Another theory presumes a Northwest Germanic unity preceding the emergence of Proto-Norse proper from roughly the 5th century.[ب][ت] An alternative suggestion explaining the impossibility of classifying the earliest inscriptions as either North or West Germanic is forwarded by È. A. Makaev, who presumes a "special runic koine", an early "literary Germanic" employed by the entire Late Common Germanic linguistic community after the separation of Gothic (2nd to 5th centuries), while the spoken dialects may already have been more diverse.[27]

The Meldorf fibula وكتاب جرمانيا لتاكيتوس

With the potential exception of the Meldorf fibula, a possible runic inscription found in Schleswig-Holstein dating to around 50 AD, the earliest reference to runes (and runic divination) may occur in Roman Senator Tacitus's ethnographic Germania.[28] Dating from around 98 CE, Tacitus describes the Germanic peoples as utilizing a divination practice involving rune-like inscriptions:

For divination and casting lots they have the highest possible regard. Their procedure for casting lots is uniform: They break off the branch of a fruit tree and slice into strips; they mark these by certain signs and throw them, as random chance will have it, on to a white cloth. Then a state priest, if the consultation is a public one, or the father of the family, if it is private, prays to the gods and, gazing to the heavens, picks up three separate strips and reads their meaning from the marks scored on them. If the lots forbid an enterprise, there can be no further consultation about it that day; if they allow it, further confirmation by divination is required.[29]

As Victoria Symons summarizes, "If the inscriptions made on the lots that Tacitus refers to are understood to be letters, rather than other kinds of notations or symbols, then they would necessarily have been runes, since no other writing system was available to Germanic tribes at this time."[28]

النقوش المبكرة

Runic inscriptions from the 400-year period 150–550 AD are described as "Period I". These inscriptions are generally in Elder Futhark, but the set of letter shapes and bindrunes employed is far from standardized. Notably the j, s, and ŋ runes undergo considerable modifications, while others, such as p and ï, remain unattested altogether prior to the first full futhark row on the Kylver Stone (ح. 400 AD).

Artifacts such as spear heads or shield mounts have been found that bear runic marking that may be dated to 200 AD, as evidenced by artifacts found across northern Europe in Schleswig (North Germany), Funen, Zealand, Jutland (Denmark), and Scania (Sweden). Earlier—but less reliable—artifacts have been found in Meldorf, Süderdithmarschen, in northern Germany; these include brooches and combs found in graves, most notably the Meldorf fibula, and are supposed to have the earliest markings resembling runic inscriptions.

الاستخدامات السحرية والمقدسة

In stanza 157 of Hávamál, the runes are attributed with the power to bring that which is dead to life. In this stanza, Odin recounts a spell:

|

|

استخدامات العصور الوسطى

As Proto-Germanic evolved into its later language groups, the words assigned to the runes and the sounds represented by the runes themselves began to diverge somewhat and each culture would create new runes, rename or rearrange its rune names slightly, or stop using obsolete runes completely, to accommodate these changes. Thus, the Anglo-Saxon futhorc has several runes peculiar to itself to represent diphthongs unique to (or at least prevalent in) Old English.

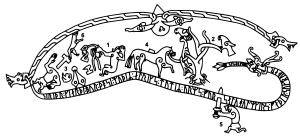

Some later runic finds are on monuments (runestones), which often contain solemn inscriptions about people who died or performed great deeds. For a long time it was presumed that this kind of grand inscription was the primary use of runes, and that their use was associated with a certain societal class of rune carvers.

In the mid-1950s, however, approximately 670 inscriptions, known as the Bryggen inscriptions, were found in Bergen.[32] These inscriptions were made on wood and bone, often in the shape of sticks of various sizes, and contained information of an everyday nature—ranging from name tags, prayers (often in Latin), personal messages, business letters, and expressions of affection, to bawdy phrases of a profane and sometimes even of a vulgar nature. Following this find, it is nowadays commonly presumed that, at least in late use, Runic was a widespread and common writing system.

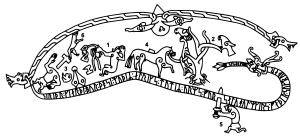

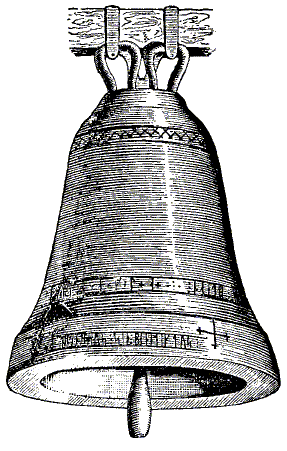

In the later Middle Ages, runes also were used in the clog almanacs (sometimes called Runic staff, Prim, or Scandinavian calendar) of Sweden and Estonia. The authenticity of some monuments bearing Runic inscriptions found in Northern America is disputed; most of them have been dated to modern times.

الأبجديات

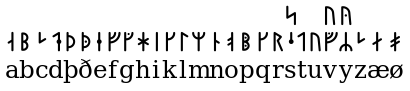

فوثارك القديم (القرون الثاني للثامن)

The Elder Futhark, used for writing Proto-Norse, consists of 24 runes that often are arranged in three groups of eight; each group is referred to as an ætt (Old Norse, meaning 'clan, group'). The earliest known sequential listing of the full set of 24 runes dates to approximately AD 400 and is found on the Kylver Stone in Gotland, Sweden.

Each rune most likely had a name which was chosen to represent the sound of the rune itself. The names are, however, not directly attested for the Elder Futhark themselves. Germanic philologists reconstruct names in Proto-Germanic based on the names given for the runes in the later alphabets attested in the rune poems and the linked names of the letters of the Gothic alphabet. For example, the letter /a/ was named from the runic letter ![]() called Ansuz. An asterisk before the rune names means that they are unattested reconstructions. The 24 Elder Futhark runes are the following:[33]

called Ansuz. An asterisk before the rune names means that they are unattested reconstructions. The 24 Elder Futhark runes are the following:[33]

| الرون | UCS | Trans. | IPA | Proto-Germanic name | المعنى |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᚠ | f | /ɸ/, /f/ | *fehu | "chattel, ثروة" | |

| ᚢ | u | /u(ː)/ | ?*ūruz | "aurochs", Wild ox (or *ûram "water/slag"?) | |

| ᚦ | þ | /θ/, /ð/ | ?*þurisaz | "Thurs" (see Jötunn) or *þunraz ("the god Thunraz") | |

| ᚨ | a | /a(ː)/ | *ansuz | "god" | |

| ᚱ | r | /r/ | *raidō | "ride, رحلة" | |

| ᚲ | k (c) | /k/ | ?*kaunan | "ulcer"? (or *kenaz "torch"?) | |

| ᚷ | g | /ɡ/ | *gebō | "هدية" | |

| ᚹ | w | /w/ | *wunjō | "joy" | |

| ᚺ ᚻ | h | /h/ | *hagalaz | "hail" (the precipitation) | |

| ᚾ | n | /n/ | *naudiz | "need" | |

| ᛁ | i | /i(ː)/ | *īsaz | "ice" | |

| ᛃ | j | /j/ | *jēra- | "year, good year, harvest" | |

| ᛇ | ï (æ) | /æː/[34] | *ī(h)waz | "yew-tree" | |

| ᛈ | p | /p/ | ?*perþ- | meaning unknown; possibly "pear-tree". | |

| ᛉ | z | /z/ | ?*algiz | "elk" (or "protection, defence"[35]) | |

| ᛊ ᛋ | s | /s/ | *sōwilō | "sun" | |

| ᛏ | t | /t/ | *tīwaz | "the god Tiwaz" | |

| ᛒ | b | /b/ | *berkanan | "birch" | |

| ᛖ | e | /e(ː)/ | *ehwaz | "horse" | |

| ᛗ | m | /m/ | *mannaz | "man" | |

| ᛚ | l | /l/ | *laguz | "water, lake" (or possibly *laukaz "leek") | |

| ᛜ | ŋ | /ŋ/ | *ingwaz | "the god Ingwaz" | |

| ᛞ | d | /d/ | *dagaz | "day" | |

| ᛟ | o | /o(ː)/ | *ōþila-/*ōþala- | "heritage, estate, possession" |

الرون الأنگلو-ساكسون (قرون 5 إلى 11)

Younger Fuþark (9th to 11th c.)

The Anglo-Saxon runes, also known as the futhorc (sometimes written fuþorc), are an extended alphabet, consisting of 29, and later 33, characters. It was probably used from the 5th century onwards. There are competing theories as to the origins of the Anglo-Saxon (also called Anglo-Frisian) Futhorc. One theory proposes that it was developed in Frisia and later spread to England,[بحاجة لمصدر] while another holds that Scandinavians introduced runes to England, where the futhorc was modified and exported to Frisia.[بحاجة لمصدر] Some examples of futhorc inscriptions are found on the Thames scramasax, in the Vienna Codex, in Cotton Otho B.x (Anglo-Saxon rune poem) and on the Ruthwell Cross.

The Anglo-Saxon rune poem gives the following characters and names: ᚠ feoh, ᚢ ur, ᚦ þorn, ᚩ os, ᚱ rad, ᚳ cen, ᚷ gyfu, ᚹ ƿynn, ᚻ hægl, ᚾ nyd, ᛁ is, ᛄ ger, ᛇ eoh, ᛈ peorð, ᛉ eolh, ᛋ sigel, ᛏ tir, ᛒ beorc, ᛖ eh, ᛗ mann, ᛚ lagu, ᛝ ing, ᛟ œthel, ᛞ dæg, ᚪ ac, ᚫ æsc, ᚣ yr, ᛡ ior, ᛠ ear.

Extra runes attested to outside of the rune poem include ᛢ cweorð, ᛣ calc, ᚸ gar, and ᛥ stan. Some of these additional letters have only been found in manuscripts. Feoh, þorn, and sigel stood for [f], [θ], and [s] in most environments, but voiced to [v], [ð], and [z] between vowels or voiced consonants. Gyfu and wynn stood for the letters yogh and wynn, which became [g] and [w] in Middle English.

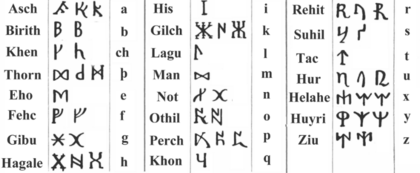

"Marcomannic runes" (8th to 9th centuries)

A runic alphabet consisting of a mixture of Elder Futhark with Anglo-Saxon futhorc is recorded in a treatise called De Inventione Litterarum, ascribed to Hrabanus Maurus and preserved in 8th- and 9th-century manuscripts mainly from the southern part of the Carolingian Empire (Alemannia, Bavaria). The manuscript text attributes the runes to the Marcomanni, quos nos Nordmannos vocamus, and hence traditionally, the alphabet is called "Marcomannic runes", but it has no connection with the Marcomanni, and rather is an attempt of Carolingian scholars to represent all letters of the Latin alphabets with runic equivalents.

Wilhelm Grimm discussed these runes in 1821.[36]

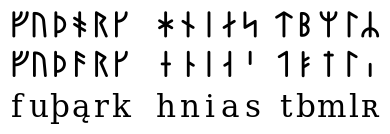

Younger Futhark (9th to 11th centuries)

The Younger Futhark, also called Scandinavian Futhark, is a reduced form of the Elder Futhark, consisting of only 16 characters. The reduction correlates with phonetic changes when Proto-Norse evolved into Old Norse. They are found in Scandinavia and Viking Age settlements abroad, probably in use from the 9th century onward. They are divided into long-branch (Danish) and short-twig (Swedish and Norwegian) runes. The difference between the two versions is a matter of controversy. A general opinion is that the difference between them was functional (viz., the long-branch runes were used for documentation on stone, whereas the short-twig runes were in everyday use for private or official messages on wood).

رون العصور الوسطى (القرون 12 إلى 15)

In the Middle Ages, the Younger Futhark in Scandinavia was expanded, so that it once more contained one sign for each phoneme of the Old Norse language. Dotted variants of voiceless signs were introduced to denote the corresponding voiced consonants, or vice versa, voiceless variants of voiced consonants, and several new runes also appeared for vowel sounds. Inscriptions in medieval Scandinavian runes show a large number of variant rune forms, and some letters, such as s, c, and z often were used interchangeably.[37][38]

Medieval runes were in use until the 15th century. Of the total number of Norwegian runic inscriptions preserved today, most are medieval runes. Notably, more than 600 inscriptions using these runes have been discovered in Bergen since the 1950s, mostly on wooden sticks (the so-called Bryggen inscriptions). This indicates that runes were in common use side by side with the Latin alphabet for several centuries. Indeed, some of the medieval runic inscriptions are written in Latin.

Dalecarlian runes (16th to 19th centuries)

According to Carl-Gustav Werner, "In the isolated province of Dalarna in Sweden a mix of runes and Latin letters developed."[39] The Dalecarlian runes came into use in the early 16th century and remained in some use up to the 20th century.[40] Some discussion remains on whether their use was an unbroken tradition throughout this period or whether people in the 19th and 20th centuries learned runes from books written on the subject. The character inventory was used mainly for transcribing Swedish in areas where Elfdalian was predominant.

قائمة النقوش الرونية

The largest group of surviving Runic inscription are Viking Age Younger Futhark runestones, most commonly found in Sweden. Another large group are medieval runes, most commonly found on small objects, often wooden sticks. The largest concentration of runic inscriptions are the Bryggen inscriptions found in Bergen, more than 650 in total. Elder Futhark inscriptions number around 350, about 260 of which are from Scandinavia, of which about half are on bracteates. Anglo-Saxon futhorc inscriptions number around 100 items.

The following table lists the number of known inscriptions (in any alphabet variant) by geographical region:[بحاجة لمصدر]

| المنطقة | عدد النقوش الرونية |

|---|---|

| السويد | 3,432 |

| النرويج | 1,552 |

| الدنمارك | 844 |

| إجمالي الاسكندناڤي | 5,826 |

| Continental Europe except Scandinavia and Frisia | 80 |

| فريزيا | 20 |

| The British Isles except Ireland | > 200 |

| Greenland | > 100 |

| Iceland | < 100 |

| Ireland | 16 |

| Faroes | 9 |

| Non-Scandinavian total | > 500 |

| Total | > 6,400 |

يونيكود

Runic alphabets were added to the Unicode Standard in September, 1999 with the release of version 3.0.

The Unicode block for Runic alphabets is U+16A0–U+16FF. It is intended to encode the letters of the Elder Futhark, the Anglo-Frisian runes, and the Younger Futhark long-branch and short-twig (but not the staveless) variants, in cases where cognate letters have the same shape resorting to "unification".

The block as of Unicode 3.0 contained 81 symbols: 75 runic letters (U+16A0–U+16EA), 3 punctuation marks (Runic Single Punctuation U+16EB ᛫, Runic Multiple Punctuation U+16EC ᛬ and Runic Cross Punctuation U+16ED ᛭), and three runic symbols that are used in early modern runic calendar staves ("Golden number Runes", Runic Arlaug Symbol U+16EE ᛮ, Runic Tvimadur Symbol U+16EF ᛯ, Runic Belgthor Symbol U+16F0 ᛰ). As of Unicode 7.0 (2014), eight characters were added, three attributed to J. R. R. Tolkien's mode of writing Modern English in Anglo-Saxon runes, and five for the "cryptogrammic" vowel symbols used in an inscription on the Franks Casket.

انظر أيضاً

- Bautil

- Gothic runic inscriptions

- Etruscan alphabet

- List of runestones

- Pentadic numerals

- Ogham

- Runiform (disambiguation), various scripts having a "rune-like" appearance

- Runic magic

- Sveriges runinskrifter

- Letter symbolism

المصادر

ملاحظات

- ^ Inscriptions such as wagnija, niþijo, and harija are supposed to represent tribe names, tentatively proposed to be Vangiones, the Nidensis, and the Harii tribes located in the Rhineland.[22] Since names ending in -io reflect Germanic morphology representing the Latin ending -ius, and the suffix -inius was reflected by Germanic -inio-,[23][24] the question of the problematic ending -ijo in masculine Proto-Norse would be resolved by assuming Roman (Rhineland) influences, while "the awkward ending -a of laguþewa[25] may be solved by accepting the fact that the name may indeed be West Germanic".[22]

- ^ Penzl & Hall 1994a assume a period of "Proto-Nordic-Westgermanic" unity down to the 5th century and the Gallehus horns inscription.[26]

- ^ The division between Northwest Germanic and Proto-Norse is somewhat arbitrary.[27]

الهامش

- ^ Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. "First Alphabet Found in Egypt", Archaeology 53, Issue 1 (January/February 2000): 21.

- ^ Runic, Unicode, https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U16A0.pdf, retrieved on 2018-03-24.

- ^ Spurkland, Terje (2005). Norwegian runes and runic inscriptions. Woodbridge: The Boydell press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 1-84383-186-4.

- ^ أ ب ت Koch 2020, p. 137.

- ^ de Vries 1962, pp. 453–454; Orel 2003, p. 310; Koch 2020, p. 137

- ^ أ ب Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. † roun, n. and rune, n.2.

- ^ أ ب ت Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill. p. 316. ISBN 9789004173361.

- ^ Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental. Errance. p. 122. ISBN 9782877723695.

- ^ أ ب de Vries 1962, pp. 453–454.

- ^ Orel 2003, p. 310.

- ^ Orel 2003, pp. 155, 190, 310.

- ^ Häkkinen, Kaisa. Nykysuomen etymologinen sanakirja

- ^ Nykysuomen sanakirja: "riimu"

- ^ "Dictionary of the Lithuanian Language". LKZ. Archived from the original on 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ Mees 2000.

- ^ Odenstedt 1990.

- ^ Williams 1996.

- ^ Dictionary of the Middle Ages (under preparation). Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2007-06-23.

- ^ Markey 2001.

- ^ Bonfante, Giuliano; Bonfante, Larissa (2002). The Etruscan Language. Manchester University Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780719055409. Archived from the original on 2015-06-22. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ Rix, Robert W. (2011). "Runes and Roman: Germanic literacy and the significance of runic writing". Textual Cultures. 6: 114–144. doi:10.2979/textcult.6.1.114.

- ^ أ ب Looijenga 1997.

- ^ Weisgerber 1968, pp. 135, 392ff.

- ^ Weisgerber 1966–1967, p. 207.

- ^ Syrett 1994, pp. 44ff.

- ^ Penzl & Hall 1994b, p. 186.

- ^ أ ب Antonsen 1965, p. 36.

- ^ أ ب Symons 2020: 5.

- ^ Mattingly 2009: 39.

- ^ Hávamál

- ^ Larrington, Carolyne. (Trans.) (1999) The Poetic Edda, page 37. Oxford World's Classics ISBN 0192839462

- ^ William, Gareth (2007). West over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. Brill Publishers. p. 473. ISBN 9789047421214. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ^ Page 2005, pp. 8, 15–16.

- ^ also rendered /ɛː/, see Proto-Germanic phonology.

- ^ Ralph Warren, Victor Elliott, Runes: an introduction, Manchester University Press ND, 1980, 51-53.

- ^ Grimm, William (1821), "18" (in de), Ueber deutsche Runen, pp. 149–59.

- ^ Jacobsen & Moltke 1942, p. vii.

- ^ Werner 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Werner 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Brix, Lise (May 21, 2015). "Isolated people in Sweden only stopped using runes 100 years ago". ScienceNordic. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

ببليوجرافيا

- Bammesberger, A and G. Waxenberger (eds), Das fuþark und seine einzelsprachlichen Weiterentwicklungen, Walter de Gruyter (2006), ISBN 3-11-019008-7.

- Blum, Ralph. (1932. The Book of Runes - A Handbook for the use of Ancient Oracle : The Viking Runes,Oracle Books, St. Martin's Press, New York, ISBN 0-312-00729-9.

- Brate, Erik (1922). Sveriges runinskrifter, (online text in Swedish)

- Düwel, Klaus (2001). Runenkunde, Verlag J.B. Metzler (In German).

- Foote, P.G., and Wilson, D.M. (1970), page 401. The Viking Achievement, Sidgwick & Jackson: London, UK, ISBN 0-283-97926-7

- Jacobsen, Lis (1941–42). Danmarks runeindskrifter. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaards Forlag.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Looijenga, J. H. (1997). Runes around the North Sea and on the Continent AD 150-700, dissertation, Groningen University.

- MacLeod, Mindy, and Bernard Mees (2006). Runic Amulets and Magic Objects. Boydell Press: Woodbridge, UK; Rochester, NY, ISBN 1843832054.

- Markey, T.L. (2001). A tale of the two helmets: Negau A and B. Journal of Indo-European Studies 29: 69–172.

- McKinnell, John and Rudolf Simek, with Klaus Düwel (2004). Runes, Magic, and Religion: A Sourcebook. Wien: Fassbaender, ISBN 3900538816.

- Mees, Bernard (200). The North Etruscan thesis of the origin of the runes. Arkiv for nordisk fililogi 115: 33–82.

- Odenstedt, Bengt (1990). On the Origin and Early History of the Runic Script, Uppsala, ISBN 9185352209.

- Page, R.I. (1999). An Introduction to English Runes, The Boydell Press, Woodbridge. ISBN 0-85115-946-X.

- Prosdocimi, A.L. (2003–4). Sulla formazione dell'alfabeto runico. Promessa di novità documentali forse decisive. Archivio per l'Alto Adige. XCVII–XCVIII:427–440

- Robinson, Orrin W. (1992). Old English and its Closest Relatives: A Survey of the Earliest Germanic Languages Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1454-1

- Spurkland, Terje (2005). Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions, Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-186-4

- Stoklund, M. (2003). The first runes - the literary language of the Germani in The Spoils of Victory - the North in the Shadow of the Roman Empire Nationalmuseet (?)

- Thorsson, Edred (1987), Runelore: a handbook of esoteric runology, United States: Samuel Weiser, Inc., ISBN 0-87728-667-1

- Werner, Carl-Gustav (2004). The allrunes Font and Package[1]PDF.

- Williams, Henrik. (1996). The origin of the runes. Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 45: 211–18.

- Williams, Henrik (2004). "Reasons for runes," in The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process, Cambridge University Press, pp. 262–273. ISBN 0-521-83861-4

وصلات خارجية

- Ancientscripts.com Futhark entry.

- Omniglot.com runic alphabet entry.

- Nytt om Runer runology journal.

- Bibliography of Runic Scholarship

- Unicode Code ChartPDF (68.3 KB)

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- Articles with text in Germanic languages

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Scripts with ISO 15924 four-letter codes

- Articles containing سويدية-language text

- Articles containing uncoded-language text

- Articles containing Proto-Germanic-language text

- Articles containing Gothic-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية القديمة (ح. 450-1100)-language text

- Articles containing ساكسونية قديمة-language text

- Articles containing Middle Dutch (ca. 1050-1350)-language text

- Articles containing Old High German (ca. 750-1050)-language text

- Articles containing نورسية القديمة-language text

- Articles containing Proto-Celtic-language text

- Articles containing Old Irish (to 900)-language text

- Articles containing Middle Welsh-language text

- Articles containing Middle Breton-language text

- Articles containing Transalpine Gaulish-language text

- Articles containing Middle Irish (900-1200)-language text

- Articles containing Lepontic-language text

- Articles containing سنسكريتية-language text

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing Old Frankish-language text

- Articles containing Lombardic-language text

- Articles containing فنلندية-language text

- Articles containing لتوانية-language text

- Articles containing دنماركية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2016

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1: abbreviated year range

- Runes

- Runology

- Alphabets

- Germanic culture

- Language and mysticism

- Magic symbols

- Obsolete writing systems

- تاريخ الشعوب الجرمانية